95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Dev. Psychol. , 28 October 2024

Sec. Adolescent Psychological Development

Volume 2 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fdpys.2024.1446938

This article is part of the Research Topic Promoting a Kinder and More Just World: The Development of Prosocial, Moral, and Social Justice Behaviors in Adolescence View all 7 articles

Introduction: The present two-wave longitudinal study examined the relation between White U.S. parents' color-conscious racial socialization for African Americans and adolescents' racial attitudes, and explored how parental psychological control might moderate this relation.

Method: Participants included 412 White U.S. adolescents (42% girls; Mage = 15.63 years, SD = 1.24) and their primary caregivers (52% mothers). They completed online questionnaires, with parents reporting on their color-conscious racial socialization at Time 1, and adolescents providing measures of their perception of parents' psychological control at Time 1, color-blind attitudes, and racial prejudice at both time points, ~16 months apart.

Results: Our findings revealed that parents' color-conscious racial socialization for African Americans was negatively associated with adolescents' negative racial attitudes. Additionally, parental psychological control moderated this relation: the negative association was evident only when parents exhibited low or average levels of psychological control.

Discussion: This study highlights the crucial role parents play in shaping their adolescents' racial attitudes and underscores the necessity of an autonomy-supportive environment to enhance the success of parents' color-conscious socialization practices. Understanding these dynamics is essential for developing effective interventions to reduce racial biases and foster inclusive attitudes among adolescents.

Racial prejudice is linked to serious social problems such as discriminatory education practices, workplace inequity, healthcare disparities, social alienation and bias-motivated crimes (Craig, 2002; Dovidio et al., 2008; Feagin et al., 2000; Quintana and Mahgoub, 2016). These problems are associated with mental health problems in minoritized children and adults, including psychological distress (Ong et al., 2009), depression (Hudson et al., 2016), anxiety (Gaylord-Harden and Cunningham, 2009) and physical health problems such as hypertension (Dolezsar et al., 2014). A recent study showed that, on average, African American adolescents encounter more than five instances of racial discrimination daily (English et al., 2020). This highlights the pervasive nature of the issue, which has consequences for these youths' mental and physical well-being. Thus, it is crucial to diminish racial prejudice and discrimination of African Americans and other minoritized youth to protect their wellbeing as well as to foster social cohesion and to ensure equal opportunities for all individuals.

White U.S. adolescents' racial attitudes are influenced by various factors, including the influence of parents, peers, and the school environment. The role of parents in shaping their children's racial attitudes has been widely discussed, particularly in relation to the possibility of passing these biases from one generation to the next (Zagrean et al., 2022; Aboud and Doyle, 1996; Castelli et al., 2009; Sinclair et al., 2005). Some research suggests that parents' racial attitudes have been found to be directly related to adolescents' racial biases (Smalls Glover et al., 2022) and anti-racist ideology (White and Gleitzman, 2006). White and Gleitzman also observed that this relationship appears more pronounced when parents are less authoritative. Similarly, another study showed that early adolescents' ethnic-racial attitudes were more strongly related to their parents' attitudes when they identified more closely with their parents (Sinclair et al., 2005). These findings suggest that the transmission of such biases may depend on the quality of the parent-child relationship.

Even though schools and peers play a significant role in adolescents' lives, parents are crucial in determining the environments their children engage with, which in turn shapes the diversity they encounter and the social norms they observe and ultimately influences the development of their racial attitudes (Hagerman, 2014). Schools can foster environments that influence how adolescents from different backgrounds interact (Schofield, 2001). Racial diversity in schools provides White U.S. adolescents opportunities for interracial contact and to develop more positive racial attitudes especially when these interactions are positive (Graham, 2018; Stearns, 2004). Discussions about race and racism in schools have been shown to positively impact adolescents' racial attitudes (Hughes et al., 2007). Furthermore, peer interactions and norms also affect adolescents' racial attitudes. When peers encourage cross-ethnic interactions, White adolescents experience greater comfort, higher-quality interactions, and stronger friendships across different ethnic and racial groups (Tropp et al., 2016). Research consistently demonstrates that high quality cross-race friendships and interracial interactions effectively reduce racial biases (Dovidio et al., 2017; White et al., 2009). Even though peers have a strong influence, a recent study (Rivas-Drake et al., 2019) showed that adolescents are more likely to choose friends whose intergroup attitudes align with their own. In line with this, Edmonds and Killen (2009) found that adolescents' perceptions of their parents' racial attitudes significantly influence their cross-race relationships. Thus, these findings underscore the significant role parents play in shaping adolescents' cross-race friendships and interactions. By influencing their children's racial attitudes and openness to diverse relationships, parents affect the diversity of adolescents' social circles, which in turn further molds their racial attitudes.

Another way parents shape their children's racial biases toward African Americans is through color-conscious racial socialization (Perry et al., 2024; Pahlke et al., 2021). This involves parents actively engaging their children in discussions and practices that promote understanding and appreciation of racial diversity. Researchers have suggested that the vast majority of White (non-Hispanic) parents are more inclined to take a color-blind perspective and minimize discussions about race with their children (Hughes et al., 2006; Pahlke et al., 2012; Vittrup and Holden, 2011). Parents can also influence children's diversity exposure by selecting schools and neighborhoods where the majority of residents are White (Hagerman, 2014). These color-evasive approaches have done little to eradicate prejudice toward African Americans among White U.S. youth. Nevertheless, White U.S. parents may possess the potential to instill positive racial attitudes and awareness of racism in adolescents through color-conscious approaches. Through open discussions on race, privilege, and systemic inequalities, as well as actively exposing their children to diversity, White U.S. parents may contribute to adolescents' comprehensive understanding of race and racism. This proactive approach may equip adolescents with the knowledge to critically assess and address social injustices (Freeman et al., 2022; Hagerman, 2018) through allyship and anti-racism.

Research on White U.S. parents' racial socialization for African Americans primarily focuses on the presence, frequency, content of conversations about race as well as parents' characteristics associated with color-conscious socialization strategies. However, studies linking this socialization to their children's racial attitudes are scarce (Perry et al., 2024; Scott et al., 2020). Limited research suggests that parents' color-conscious socialization decreases children's racial bias (Perry et al., 2020) and pro-White bias (Perry et al., 2024), while fostering positive outgroup attitudes (Vittrup and Holden, 2011) and greater feelings of warmth toward racial outgroups (Pahlke et al., 2021). These studies often focus on preschool and elementary school children.

Adolescence is a critical period for developing independence and forming identity, during which individuals begin to establish their own views on race (Hagerman, 2014; Steinberg and Morris, 2001). This developmental stage is marked by increased capacity for abstract thinking and moral reasoning, which makes it an ideal time to address complex racial issues by parents (Hazelbaker et al., 2022; Quintana, 2008). In line with this, parents see adolescents as more capable of handling these issues than younger children (Freeman et al., 2022). Adolescents who embrace positive racial attitudes are likely to become empathetic, socially conscious adults who promote inclusivity (Thomann and Suyemoto, 2018). Thus, more research is needed to understand the relationship between parents' color-conscious socialization and adolescents' racial attitudes. The present longitudinal study aims to address this need by examining this association.

The quality of the parent-child relationship can moderate the relation between parents' color-conscious racial socialization and adolescents' racial attitudes (Sinclair et al., 2005). The emotional climate established by parenting impacts effectively parental values are transmitted as it influences children's receptiveness to parents' socialization attempts (Darling and Steinberg, 1993). Although there is a lack of studies examining the moderating role of parenting in White Americans, research focusing on racial and ethnic minorities has yielded significant results. Racial socialization, paired with supportive, warm, democratic parenting, and minimal negative practices like uninvolved parenting, leads to positive outcomes in minority youth (Elmore and Gaylord-Harden, 2013; Lambert et al., 2015; Reynolds et al., 2017; Smalls, 2009). These findings suggest that parenting practices significantly influence the effectiveness of racial socialization efforts. Parents' frequent use of psychological control which includes tactics like love withdrawal, constraining verbal expressions, invalidating feelings, and personal attacks can create a negative climate by escalating conflicts between parents and adolescents. This weakens the adolescents' sense of connection to their parents (Barber, 2002), which can reduce adolescents' openness to their parents' racial socialization efforts.

Moreover, Grusec and Goodnow (1994) highlight that for parental socialization to be effective, children must accurately perceive and willingly accept their parents' messages. This process of internalization is facilitated when children view their parents' actions as appropriate, feel motivated to adopt their viewpoints, and recognize the values as self-generated (Grusec, 2002). Grusec and Goodnow's (1994) model emphasizes the importance of child autonomy. They claim that threats to autonomy should be minimized for parental messages to be motivating and to facilitate feelings of self-generation. They argue that threats to autonomy can lead to the active rejection of a parent's viewpoint and a desire to oppose parental values, especially as children grow older. Based on this model, psychological control can lessen the effectiveness of racial socialization because it undermines an adolescent's sense of autonomy, which may lead to rejection of their parents' messages, including those related to racial socialization. Consequently, parents' psychological control can hinder adolescents' internalization of racial equality and social justice (Barber, 2002; Grusec and Goodnow, 1994).

The present study aimed to examine the relations between parents' color-conscious racial socialization for African Americans and adolescents' racial attitudes, specifically focusing on color-blind attitudes and racial prejudice. Additionally, it explored how parental psychological control moderates this relation. Specifically, we hypothesized that high levels of parents' color-conscious racial socialization would be associated with low levels of negative racial attitudes in adolescents. Furthermore, we expected that high, but not, low levels of parental psychological control would weaken the relations between parents' color-conscious socialization efforts and adolescents' racial attitudes.

The study sample consisted of 412 White U.S. (non-Hispanic) adolescents (42% girls; M age = 15.63 years, SD = 1.24) and their primary caregivers, 52% of whom were mothers. In terms of education, 45% of the parents held a four-year university degree or higher, 35% had some university education, and 17.5% had a high school diploma. The average household income was $78,171, with 25% of the households earning < $40,000 annually. Fifty-five percent of the participants were from conservative states. Adolescents were tracked across two waves of data collection, each spaced 16 months apart. The retention rate was 38.1% (N = 157) at Time 2. Attrition analyses revealed no significant differences between those who continued in the study and those who withdrew in terms of adolescents' perceptions of parental psychological control, racial prejudice, color-blind attitudes, adolescents' gender, and parents' gender and education. Participants from liberal states had higher attrition rates. However, at the second wave, 37% of participants were still from liberal states suggesting there was sufficient representation across states. Moreover, there were no significant differences in responses to the measures based on the geographic regions where participants reside.

Participants were recruited through an online survey company. Wave 1 of data collection began in January 2021, when many schools were still utilizing hybrid or online learning due to COVID-19, and just eight months after the death of George Floyd and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. The study targeted White U.S. (non-Hispanic) parents who were fluent in English, living in the U.S., and had a child between 12 and 15 years old. Interested parents received a consent form and, after agreeing to participate, completed online surveys with their adolescents using Qualtrics. To ensure that adolescents, rather than parents, completed the surveys for adolescents, we included questions specifically targeted at adolescents' knowledge, such as identifying their favorite social media influencer and top song. We also monitored the time taken to answer these questions. In the first wave (Time 1) of data collection, parents' color-conscious racial socialization and adolescents' perceptions of parental psychological control, color-blind attitudes, and racial prejudice were measured. In the second wave (Time 2), which occurred 16 months later, only adolescents completed the same scales. Participants were compensated $15 for each completed survey.

Parents completed the shortened and adapted version of the Race Conscious Approach subscale of White Racial Socialization Scale (Hagan et al., 2024). This scale assesses parental practices of color-conscious racial socialization, specifically how parents actively engage their children in discussions and environments that promote understanding of racial and ethnic diversity. It has nine items which were rated on a 5-point scale. Example items include “I talk with my child about racial inequality in America.” and “I talk to my child about police violence toward people of color.” Higher values indicate higher levels of parents' color-conscious racial socialization (α = 0.84).

Adolescents completed the eight-item Psychological Control Scale–Youth Self-Report (PCS-YSR; Barber, 2002). This scale assesses various aspects of psychological control, including love withdrawal, constraining verbal expressions, invalidating feelings, and personal attacks. Example items include “My mother or father is always trying to change how I feel or think about things” and “My mother or father is less friendly with me if I do not see things her/his way.” Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores on this scale indicated a greater degree of parental psychological control (α = 0.90).

The Modern Racism Scale (MRS; McConahay et al., 1981) was used to assess adolescents' racial prejudice. It measures these attitudes subtly to reduce biased responses. The MRS consists of seven items, each rated on a 5-point scale. Example items include “Over the past few years, Blacks have gotten more economically than they deserve” and “Blacks are getting too demanding in their push for equal rights.” Adolescents indicated their level of agreement with these statements, from 1 (“disagree strongly”) to 5 (“agree strongly”). Higher scores on the scale reflected a higher degree of racial prejudice (α = 0.90).

Color-blind attitudes were measured using two subscales from the Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale (Neville et al., 2000). The seven-item Unawareness of Institutional Discrimination subscale (α = 0.81). assesses ignorance of systemic racial discrimination and exclusion. An example item is “Social policies, such as affirmative action, discriminate unfairly against White people.” The six-item Unawareness of Blatant Racial Issues (α = 0.80) subscale evaluates blindness to pervasive racial discrimination. An example item is “Social problems in the U.S. are rare, isolated situations.” The items are scored on u a 6-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating stronger color-blind racial attitudes. This scale has been used in previous studies involving adolescents (e.g., Atkin and Ahn, 2022; Aldana et al., 2012).

Adolescents were asked to report their age and gender. The age and gender of the adolescents, along with the gender of the parents, were used as statistical controls.

A moderation model was analyzed using Mplus Version 8. The model estimated the prediction of adolescents' negative racial attitudes at Time 2 from parental color-conscious racial socialization at Time 1, parental psychological control at Time 1, and their interaction. In analyses, a latent negative racial attitudes variable was constructed, with racial prejudice, unawareness of institutional discrimination and of blatant racism included as indicators. All indicators loaded significantly onto the latent factor with standardized estimates ranging from 0.82 to 0.88. Parents' gender as well as adolescents' age and gender were included as statistical controls in the model. Full information maximum likelihood was used to account for missing data. Models were considered to fit the data well if they achieved the following thresholds: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for the variables are presented in Table 1. Parents' color-conscious racial socialization was negatively correlated with adolescents' racial prejudice, unawareness of institutional discrimination and of blatant racial issues. Racial prejudice was positively correlated with both types of color-blind attitudes.

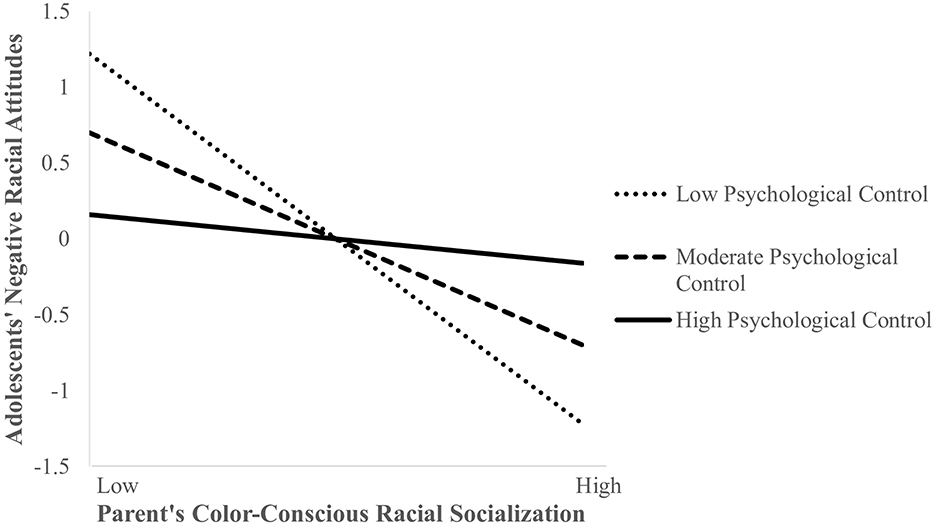

The model fit the data well : = 10.46, p = 0.58; CFI = 1.0; RMSEA = 0.00; SRMR = 0.024. Results indicated that parents' color-conscious racial socialization at Time 1 was negatively related to adolescents' negative racial attitudes (β = −0.23, p = 0.001) at Time 2 (see Figure 1). Parents who engaged in more color-conscious racial socialization had children with lower levels of negative racial attitudes. Parental psychological control was not related to adolescents' racial attitudes (β = 0.03, p = 0.65) at Time 2. Additionally, the interaction effect between parents' color-conscious racial socialization and psychological control on adolescents' racial attitudes was significant (β = 0.18, p = 0.002). To probe this interaction, we calculated the relations between parental color conscious racial socialization at Time 1 and adolescents' negative racial attitudes at Time 2 under conditions of low parental control (one standard deviation below the mean), average parental control (at the mean), and high parental control (one standard deviation above the mean). Simple slopes analysis revealed that only when parental psychological control was low or average, parents' color-conscious socialization at Time 1 was negatively related to adolescents' negative attitudes (β = −0.40, p < 0.001; β = −0.23, p = 0.001, respectively) at Time 2 (see Figure 2). This relation was not observed when parental psychological control was high (β = −0.05, p = 0.54). When excluding age and gender as control variables, the results were comparable, with racial socialization still significantly related to adolescents' racial attitudes (β = −0.24, p < 0.001) and the interaction effect remaining significant (β = 0.17, p = 0.002). We also tested the same model using Time 1 variables, and the results were comparable (see Supplementary material). When controlling for prior levels of racial attitudes, both the main effect (β = 0.01; p = 0.83) and the interaction effect (β = 0.02; p = 0.75) became non-significant. This is likely due to the high stability coefficient for racial attitudes between Time 1 and Time 2 (β = 0.76, p < 0.01).

Figure 2. Linear relation between parents' color-conscious racial socialization and adolescents' negative attitudes as a function of three levels of parental psychological control: mean level, 1 SD above, and 1 SD below the mean.

We examined the relations between parents' color-conscious racial socialization and adolescents' negative racial attitudes over time. Moreover, we focused on the moderating role of parental psychological control in this relation. As predicted, our findings revealed that parents' color-conscious racial socialization was negatively associated with adolescents' negative racial attitudes. Moreover, parents' psychological control moderated this relation, such that the negative association only held when parents exhibited average or low levels of psychological control. In other words, parents who engaged in more color-conscious racial socialization had children with lower levels of negative racial attitudes, but this was only observed when their psychological control was low or moderate. The findings extend prior work on White U.S. parents' socialization of racial attitudes by demonstrating the importance of psychological control and yielding evidence of these relations in a sample of adolescents.

These findings indicate that when parents actively engage in practices that promote an understanding and appreciation of racial and ethnic diversity, their adolescents are less likely to develop negative racial attitudes. This finding aligns with previous research on color-conscious parenting practices (Perry et al., 2020; Vittrup and Holden, 2011; Pahlke et al., 2021) and extends the demonstrated effectiveness of these practices to adolescents. Despite adolescence being a time of growing independence and significant peer influence (Steinberg and Morris, 2001), our findings reveal that parents continue to play a crucial role in shaping their adolescents' racial attitudes. Effective racial socialization involves parents actively using color-conscious parenting practices, such as engaging their children in conversations about racial issues. By creating opportunities for children to talk about racial issues, parents would be helping their children to challenge and reduce racial biases, which can in turn empower youth to engender inclusive environments for diverse others. It is important to note that our data collection took place during a period of heightened racial awareness following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police. This period was marked by ongoing protests surrounding Black Lives Matter, which continued to shape national conversations, with demands for racial justice and police reform at the forefront. The civil unrest during this time may have provided more opportunities for White parents to engage in socializing anti-racist ideologies. Thus, the present findings advance our understanding of these important issues in the context of a rapidly, changing society.

Moreover, our findings revealed that the level of parental psychological control is related to the effectiveness of color-conscious racial socialization efforts. When parents demonstrated average or low levels of psychological control, their color-conscious socialization was associated with lower negative racial attitudes in their adolescents. Conversely, highly psychologically controlling parents' color-conscious socialization did not show a significant relationship with their adolescents' racial attitudes. This aligns with general parent-child socialization research regarding the importance of parenting and indicates that similar patterns apply to racial socialization in White U.S. families as well. When parents exert psychological control, it can undermine adolescents' sense of autonomy and create a tense emotional climate (Darling and Steinberg, 1993; Grusec, 2002; Grusec and Goodnow, 1994). This strained relationship may reduce adolescents' motivation to listen to and internalize the values of racial equality and justice, even when parents engage in color-conscious socialization efforts. Parental psychological control might be particularly problematic during adolescence, a period in which autonomy and independence are often highly valued in European American families (Steinberg and Morris, 2001). When parents exert high levels of psychological control, it can lead to resistance, as adolescents may perceive these efforts as intrusive and undermining their growing sense of self. This resistance can be especially pronounced in the context of sensitive topics such as race, where adolescents are likely to encounter diverse perspectives from peers and media. Consequently, the adolescents may disregard their parents' messages about racial equality by seeing them as part of the controlling behaviors they wish to rebel against or ignore. Creating an environment of open dialogue and mutual respect, where guidance is balanced with autonomy, may make it more likely that White U.S. adolescents will internalize and embrace the value of racial justice.

The study has a few limitations. First, strong causal conclusions cannot be drawn from our data. Controlling for prior levels of racial attitudes rendered both the main and interaction effects not statistically significant, likely due to collinearity concerns arising from the strong correlations between adolescents' racial attitudes at Time 1 and Time 2. This limitation affects our ability to make confident inferences about predicting changes. However, the observed relationships remained robust over time and when controlling for gender and age. Most previous studies that have examined parental socialization of racial attitudes have been cross-sectional (Vittrup and Holden, 2011; Pahlke et al., 2021; Perry et al., 2020, 2024). Future intervention programs that encourage White U.S. parents to discuss race related issues with children would provide stronger evidence on the causal links between racial socialization and improved racial attitudes in adolescence. Secondly, this study relies on self-report measures for all primary variables, which can be confounded by self-presentational demands and shared method variance. Nonetheless, unlike most prior research, the present study utilized multiple informant self-report measures and collected data from both parents and adolescents. To mitigate potential biases associated with self-reporting, future research should employ multiple methods (e.g., observational, behavioral tasks). And third, the present study was conducted on a select sample of participants that might not represent the broader population of White U.S. parents and children. Studies that recruit a broader and more representative sample of White U.S. families is desirable. Additionally, while our results suggest that parental psychological control undermines the effectiveness of color-conscious racial socialization among middle-class White U.S. families, this may not hold true for other ethnic groups or social classes. The significance of autonomy and independence during adolescence can also vary across different social and cultural contexts (Chao and Aque, 2009; Halgunseth et al., 2006). Future research should examine how these factors influence the relationship between parental control and racial socialization in more diverse populations.

The present findings contribute to the limited evidence on the longitudinal links between parents' color-conscious socialization, parenting and adolescents' racial attitudes. This study underscores the critical role of parental involvement in fostering inclusive attitudes. The moderating effect of parental psychological control highlights the importance of creating an autonomy-supportive environment to enhance the effectiveness of racial socialization efforts. These results inform the development of interventions aimed at reducing adolescents' racial biases by suggesting that educating parents on color-conscious practices and addressing psychological control can be highly effective.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to AA, YWZhMzE5QGxlaGlnaC5lZHU=.

The studies involving humans were approved by The Lehigh University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

AA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GC: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JL: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was funded by the Lehigh University Faculty Innovation Grant.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdpys.2024.1446938/full#supplementary-material

Aboud, F. E., and Doyle, A. B. (1996). Parental and peer influences on children's racial attitudes. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 20, 371–383. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(96)00024-7

Aldana, A., Rowley, S. J., Checkoway, B., and Richards-Schuster, K. (2012). Raising ethnic-racial consciousness: the relationship between intergroup dialogues and adolescents' ethnic-racial identity and racism awareness. Equity Excellence Educ. 45, 120–137. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2012.641863

Atkin, A. L., and Ahn, L. H. (2022). Profiles of racial socialization messages from mothers and fathers and the colorblind and anti-Black attitudes of Asian American adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 51, 1048–1061. doi: 10.1007/s10964-022-01597-2

Barber, B. K, . (ed.). (2002). Intrusive Parenting: How Psychological Control Affects Children and Adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01915.x

Castelli, L., Zogmaister, C., and Tomelleri, S. (2009). The transmission of racial attitudes within the family. Dev. Psychol. 45, 586–591. doi: 10.1037/a0014619

Chao, R. K., and Aque, C. (2009). Interpretations of parental control by Asian immigrant and European American youth. J. Fam. Psychol. 23, 342–354. doi: 10.1037/a0015828

Craig, K. M. (2002). Examining hate-motivated aggression: a review of the social psychological literature on hate crimes as a distinct form of aggression. Aggress. Violent Behav. 7, 85–101. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00039-2

Darling, N., and Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 113, 487–496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

Dolezsar, C. M., McGrath, J. J., Herzig, A. J., and Miller, S. B. (2014). Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: a comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychol. 33, 20–34. doi: 10.1037/a0033718

Dovidio, J. F., Love, A., Schellhaas, F. M. H., and Hewstone, M. (2017). Reducing intergroup bias through intergroup contact: twenty years of progress and future directions. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 20, 606–620. doi: 10.1177/1368430217712052

Dovidio, J. F., Penner, L. A., Albrecht, T. L., Norton, W. E., Gaertner, S. L., and Shelton, J. N. (2008). Disparities and distrust: the implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Soc. Sci. Med. 67, 478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.019

Edmonds, C., and Killen, M. (2009). Do adolescents' perceptions of parental racial attitudes relate to their intergroup contact and cross-race relationships? Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 12, 5–21. doi: 10.1177/1368430208098773

Elmore, C. A., and Gaylord-Harden, N. K. (2013). The influence of supportive parenting and racial socialization messages on African American youth behavioral outcomes. J. Child Fam. Stud. 22, 63–75. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9653-6

English, D., Lambert, S. F., Tynes, B. M., Bowleg, L., Zea, M. C., and Howard, L. C. (2020). Daily multidimensional racial discrimination among Black US American adolescents. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 66:101068. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101068

Feagin, J. R., Early, K. E., and McKinney, K. D. (2000). The many costs of discrimination: the case of middle-class African Americans. Ind. L. Rev. 34:1313.

Freeman, M., Martinez, A., and Raval, V. V (2022). What do white parents teach youth about race? Qualitative examination of white racial socialization. J. Res. Adolesc., 32, 847–862. doi: 10.1111/jora.12782

Gaylord-Harden, N. K., and Cunningham, J. A. (2009). The impact of racial discrimination and coping strategies on internalizing symptoms in African American youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 38, 532–543. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9377-5

Graham, S. (2018). Race/ethnicity and social adjustment of adolescents: how (not if) school diversity matters. Educ. Psychol. 53, 64–77. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2018.1428805

Grusec, J. E. (2002). “Parenting socialization and children's acquisition of values,” in Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 5. Practical Issues in Parenting, ed. M. H. Bornstein (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 143–167.

Grusec, J. E., and Goodnow, J. J. (1994). Impact of parental discipline methods on the child's internalization of values: a reconceptualization of current points of view. Dev. Psychol. 30, 4–19. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4

Hagan, C., Halberstadt, A., Cooke, A., and Garner, P. (2024). White parents' racial socialization: questionnaire validation and associations with children's friendships. J. Fam. Issues 45, 350–373. doi: 10.1177/0192513X2211509

Hagerman, M. A. (2014). White families and race: colour-blind and colour-conscious approaches to white racial socialization. Ethn. Racial Stud. 37, 2598–2614. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2013.848289

Hagerman, M. A., (ed.). (2018). “White kids: growing up with privilege in a racially divided America,” in White Kids (New York, NY: New York University Press). doi: 10.18574/nyu/9781479880522.001.0001

Halgunseth, L. C., Ispa, J. M., and Rudy, D. (2006). Parental control in Latino families: an integrated review of the literature. Child Dev. 77, 1282–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x

Hazelbaker, T., Brown, C. S., Nenadal, L., and Mistry, R. S. (2022). Fostering anti-racism in white children and youth: development within contexts. Am. Psychol. 77, 497–509. doi: 10.1037/amp0000948

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 6, 1–55.

Hudson, D. L., Neighbors, H. W., Geronimus, A. T., and Jackson, J. S. (2016). Racial discrimination, john henryism, and depression among African Americans. J. Black Psychol. 42, 221–243. doi: 10.1177/00957984145677

Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E. P., Johnson, D. J., Stevenson, H. C., and Spicer, P. (2006). Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: a review of research and directions for future study. Dev. Psychol. 42, 747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747

Hughes, J. M., Bigler, R. S., and Levy, S. R. (2007). Consequences of learning about historical racism among European American and African American children. Child Dev. 78, 1689–1705. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01096.x

Lambert, S. F., Roche, K. M., Saleem, F. T., and Henry, J. S. (2015). Mother–adolescent relationship quality as a moderator of associations between racial socialization and adolescent psychological adjustment. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 85, 409–420. doi: 10.1037/ort0000085

McConahay, J. B., Hardee, B. B., and Batts, V. (1981). Has racism declined in America? It depends on who is asking and what is asked. J. Confl. Resolut. 25, 563–579. doi: 10.1177/00220027810250040

Neville, H. A., Lilly, R. L., Duran, G., Lee, R. M., and Browne, L. (2000). Construction and initial validation of the Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS). J. Couns. Psychol., 47, 59–70. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.59

Ong, A. D., Fuller-Rowell, T., and Burrow, A. L. (2009). Racial discrimination and the stress process. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 1259 −1271. doi: 10.1037/a0015335

Pahlke, E., Bigler, R. S., and Suizzo, M.-A. (2012). Relations between colorblind socialization and children's racial bias: evidence from European American mothers and their preschool children. Child Dev. 83, 1164–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01770.x

Pahlke, E., Patterson, M. M., and Hughes, J. M. (2021). White parents' racial socialization and young adults' racial attitudes: moral reasoning and motivation to respond without prejudice as mediators. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 24, 1409–1426. doi: 10.1177/1368430220941065

Perry, S., Skinner-Dorkenoo, A. L., Abaied, J., Osnaya, A., and Waters, S. (2020). Initial evidence that parent-child conversations about race reduce racial biases among White US children. PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/3xdg8

Perry, S., Wu, D. J., Abaied, J. L., Skinner-Dorkenoo, A. L., Sanchez, S., Waters, S. F., et al. (2024). White parents' racial socialization during a guided discussion predicts declines in white children's pro-white biases. Dev. Psychol. 60, 624–636. doi: 10.1037/dev0001703

Quintana, S. M. (2008). “Racial perspective taking ability: developmental, theoretical, and empirical trends,” in Handbook of Race, Racism, and the Developing Child, eds. S. M. Quintana, and C. McKown (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 16–35.

Quintana, S. M., and Mahgoub, L. (2016). Ethnic and racial disparities in education: psychology's role in understanding and reducing disparities. Theory Pract. 55, 94–103. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2016.1148985

Reynolds, J. E., Gonzales-Backen, M. A., Allen, K. A., Hurley, E. A., Donovan, R. A., Schwartz, S. J., et al. (2017). Ethnic–racial identity of black emerging adults: the role of parenting and ethnic–racial socialization. J. Fam. Issues 38, 2200–2224. doi: 10.1177/0192513X16629181

Rivas-Drake, D., Saleem, M., Schaefer, D. R., Medina, M., and Jagers, R. (2019). Intergroup contact attitudes across peer networks in school: selection, influence, and implications for cross-group friendships. Child Dev. 90, 1898–1916. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13061

Schofield, J. W. (2001). “Review of research on school desegregation's impact on elementary and secondary school students,” in Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, eds. J. A. Banks, and C. A. Banks (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 597–616.

Scott, K. E., Shutts, K., and Devine, P. G. (2020). Parents' role in addressing children's racial bias: the case of speculation without evidence. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 1178–1186. doi: 10.1177/17456916209277

Sinclair, S., Dunn, E., and Lowery, B. (2005). The relationship between parental racial attitudes and children's implicit prejudice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 41, 283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.06.003

Smalls Glover, C., Varner, F., and Holloway, K. (2022). Parent socialization and anti-racist ideology development in White youth: do peer and parenting contexts matter? Child Dev. 93, 653–667. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13788

Smalls, C. (2009). African American adolescent engagement in the classroom and beyond: the roles of mother's racial socialization and democratic-involved parenting. J. Youth Adolesc. 38, 204–213. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9316-5

Stearns, E. (2004). Interracial friendliness and the social organization of schools. Youth Soc. 35, 395–419. doi: 10.1177/0044118X032616

Steinberg, L., and Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 83110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

Thomann, C. R. B., and Suyemoto, K. L. (2018). Developing an antiracist stance: how white youth understand structural racism. J. Early Adolesc. 38, 745–771. doi: 10.1177/0272431617692443

Tropp, L. R., O'Brien, T. C., González Gutiérrez, R., Valdenegro, D., Migacheva, K., de Tezanos-Pinto, P., et al. (2016). How school norms, peer norms, and discrimination predict interethnic experiences among ethnic minority and majority youth. Child Dev. 87, 1436–1451. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12608

Vittrup, B., and Holden, G. W. (2011). Exploring the impact of educational television and parent–child discussions on children's racial attitudes. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 11, 82–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2010.01223.x

White, F. A., and Gleitzman, M. (2006). An examination of family socialisation processes as moderators of racial prejudice transmission between adolescents and their parents. J. Fam. Stud. 12, 247–260. doi: 10.5172/jfs.327.12.2.247

White, F. A., Wootton, B., Man, J., Diaz, H., Rasiah, J., Swift, E., et al. (2009). Adolescent racial prejudice development: the role of friendship quality and interracial contact. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 33, 524–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.06.008

Keywords: racial socialization, psychological control, racial attitudes, color-blind beliefs, racial prejudice, white families, parent-child interactions

Citation: Agalar A, Laible DJ, Carlo G and Liew J (2024) Parents' color-conscious racial socialization and adolescents' racial attitudes: the moderating role of parental psychological control. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2:1446938. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2024.1446938

Received: 10 June 2024; Accepted: 08 October 2024;

Published: 28 October 2024.

Edited by:

Margarita Azmitia, University of California, Santa Cruz, United StatesReviewed by:

Antonya Gonzalez, Western Washington University, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Agalar, Laible, Carlo and Liew. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Afra Agalar, YWZhMzE5QGxlaGlnaC5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.