- 1Department of Psychological Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, United States

- 2Department of Graduate Psychology, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States

Introduction: Links between interpersonal relationships and physical and psychological functioning have been well-established in the literature. During adolescence, success or distress in peer relationships may have distinct effects on different aspects of wellbeing. The present study aims to examine the ways in which different adolescent peer relationship contexts (i.e., close friendship quality, social acceptance, and likability from peers) can predict outcomes relevant to adult wellbeing (i.e., social anxiety, depression, aggression, social integration, romantic insecurity, job satisfaction, and physical health). Further, the study considers how different developmental stages of adolescence may impact links between peer relationships and wellbeing outcomes.

Method: Peer relationship contexts were assessed in early (ages 13–14) and late (ages 17–18) adolescence. Markers of wellbeing were measured in young adulthood (ages 28–30). A path analysis was used to examine whether the developmental timing of adolescent peer relationship contexts could predict wellbeing in young adulthood.

Results: Results suggest that, across adolescence, broader perceived social acceptance may be a more robust predictor of adult wellbeing compared to close friendship quality and peer likability. When examined at early and late adolescence separately, early adolescent social acceptance and late adolescent close friendship quality best predicted outcomes of adult wellbeing.

Discussion: Implications and considerations for future research are discussed.

Introduction

Most individuals inherently desire successful interpersonal relationships throughout their lifetime. Indeed, the development of successful interpersonal relationships plays an instrumental role in a person's long-term positive social and emotional functioning (Wills, 1985; Siedlecki et al., 2014). Conversely, individuals who lack these types of relationships—or individuals who have not had the opportunity to develop successful relationships—may experience disruptions to functioning later in life (Landstedt et al., 2015; Marion et al., 2013). Social connection and support can provide individuals with the resources that they need to manage stress, suggesting that individuals who feel more connected to and supported by their peers may be able to handle stress better, further influencing their wellbeing (Cohen et al., 2001). However, research to date has yet to determine whether certain types of social relationships are more or less influential at specific periods of adolescence, and has not examined long-term changes in the multiple aspects of wellbeing relevant to individuals' lives as they enter young adulthood.

During adolescence specifically, feelings of success in interpersonal relationships may result from having an intimate, high-quality friendship with a peer, or from a broader feeling of social acceptance within a peer group. Further, these feelings of interpersonal success may be differentially perceived by the individual and their peers, potentially creating a situation in which an individual may be well liked by their peers but perceive their own interpersonal relationships as unsuccessful, or vice versa. Indeed, much of the research that has examined these types of relationships has been focused on early life experiences in childhood and early adolescence, despite the fact that peer relationships become increasingly important throughout adolescence with regards to an individual's social-emotional functioning (Scholte and Van Aken, 2020). Substantially less research has been conducted to understand outcomes related to high-quality friendships and social acceptance during late adolescence compared to early adolescence. This could, in part, be due to a heightened interest in understanding interpersonal relationships in the context of romantic relationships during late adolescence (Paul and White, 1990; Neemann et al., 1995). Indeed, a more recent review indicated that findings in the literature, “suggest that romantic relationships become more psychologically meaningful than friendships in late adolescence” (Furman and Rose, 2015). Further, little research aims to investigate long-term outcomes related to success in these adolescent peer contexts. The current study thus aims to investigate the effects of mutually (self and close friend) reported close friendship quality, self-reported feelings of general social acceptance, and likability reported by the broader peer group in both early and late adolescence on several markers of functioning associated with wellbeing in young adulthood, including social anxiety, depression, aggression, social integration, romantic insecurity, job satisfaction, and physical health.

Distinctions between peer relationship types

Although friendship and social acceptance both fall under the umbrella of peer relationships and can be used to gain a better sense of an individual's adjustment in the peer context, both constructs are conceptually different in the ways that they are defined and studied (Asher et al., 1996). According to Asher et al. (1996), the biggest difference between friendship and social acceptance is the nature of the peer relationships. The construct of friendship is considered to be dyadic and more intimate in nature, because of the inherent reciprocity of the relationship between two friends. Higher quality friendships tend to contain positive features such as intimacy and companionship, which are achieved through the initiative of both individuals within the friendship (Berndt, 1998).

In contrast, social acceptance can be defined as the tendency for an individual to perceive their peers as regarding them with warmth and positivity. Further, the concept of social acceptance does not consider the individual's feelings and opinions about their peers, which is why social acceptance is often described as unilateral and less intimate compared to close friendship (Asher et al., 1996; Bukowski and Hoza, 1989). Moreover, these two constructs have been found to fulfill distinct interpersonal needs throughout development with regard to an individual's overall sense of belonging and their desire to form a close, high-quality bond with a likeminded peer (Asher et al., 1996).

It is possible that an individual's own perception of their broad social acceptance and close friendship quality is congruent with whether or not they are actually liked by their peers. However, it is also possible for an individual and their peers to differ in their perceptions of likability and friendship. These perceptual incongruencies often begin in childhood and are particularly salient in individuals who are prone to cognitive biases or distortions, such as those who struggle with symptoms of social anxiety and depression (Baartmans et al., 2020). Therefore, an additional dimension of adolescent peer relationships that may be examined in relation to long-term functioning in order to account for these possible differences in perception is peer group-reported likability. Thus, friendship, self-perceived social acceptance, and objective likability from peers are all major interpersonal relationship contexts throughout development, and their relative importance to wellbeing may differ based on the particular developmental period of adolescence in which they are being studied.

Developmental timing of peer relationships

There may be certain periods of adolescence in which specific types of peer relationships are considered to be more crucial to the individual's adjustment and overall wellbeing. Specifically, broader peer acceptance may be more important during the early adolescent time period, whereas developing high-quality close friendships might be more important for late adolescents. The transition from middle childhood to early adolescence is marked by an emerging emphasis on the importance of peer influence in relation to an individual's understanding of their sense of self and their identity (Brinthaupt and Lipka, 2002). Learned associations between social status/popularity and social success in early adolescence may lead individuals who perceive themselves as being more positively regarded by their peers to become better adjusted and to feel a stronger sense of self. Thus, overall acceptance from a larger peer group may be more important in early adolescence relative to dyadic friendship quality. For example, research has found peer acceptance to be the most important predictor of early adolescent adjustment; however, friendship quality was also found to be important, but only when peer acceptance was low (Waldrip et al., 2008). Other research has shown that popularity in early adolescence has long-term effects on both prosocial (i.e., decreased hostility toward pears) and antisocial (i.e., increased risk-taking and externalizing behaviors) behaviors (Allen et al., 2005; Narr et al., 2017). This suggests the overall importance of peer relationships to early adolescent development, with specific consideration for the distinct effects that measures of broader peer acceptance may have on individuals entering this developmental time period.

Conversely, the late adolescent time period is often characterized by the development of intimacy. Specifically, Erikson's psychosocial theory of development posits that the transition from late adolescence to early adulthood is marked by the conflict of intimacy vs. isolation, which is subsequent to the late adolescent crisis of identity vs. confusion (Erikson, 1968). Consequentially, late adolescents might be more likely to seek out more intimate relationships throughout their identity and intimacy exploration than early adolescents. As such, these types of relationships (i.e., close friendships) in late adolescence are likely more reflective of the types of relationships experienced throughout adulthood. This may suggest that success in more intimate peer relationships during late adolescence may be more predictive of success in adult relationships. For example, research has shown that late adolescent close friendships are predictive of success in adult romantic relationships (Allen et al., 2020). Furthermore, a review of the literature on intimacy in adolescent relationships provides evidence for intimacy as a developmental process that becomes a focal point of late adolescence once the individual has a better understanding of their identity (Paul and White, 1990). Researchers have found that identity formation and intimacy development are related constructs, and that the exploration and achievement of each construct are dependent on each other (Hodgson and Fischer, 1979). For example, late adolescents who had high quality intimate friendships (specifically late adolescents who had close friends who were strong listeners) had a stronger sense of identity and were able to interpret everyday experiences more meaningfully (Pasupathi and Hoyt, 2009). Further, research has consistently and cross-culturally demonstrated that this sense of identity can be viewed as a protective factor in relation to aspects of adult wellbeing (Suh, 2002; Greenaway et al., 2016).

Links between peer relationships and wellbeing

Interpersonal relationships during adolescence have been widely studied in relation to outcomes related to social and emotional development. Opportunities to develop high-quality close friendships and broader forms of social acceptance provide distinct social contexts for adolescents to practice skills (e.g., emotional and behavioral regulation, kindness and respect, and social awareness and competence) that are inherent in emotional wellbeing, identity development, and socialization (Parker et al., 2006; Oberle et al., 2010) These peer relationship contexts are especially relevant during adolescence when the influence of friendships and social belongingness becomes more salient and complex (Brown and Larson, 2009). Moreover, success in peer relationships becomes a marker of psychosocial adjustment during the early adolescent time period, and individuals who report feeling socially accepted and having close friends are better adjusted across all areas of functioning during adolescence (Hussong, 2000). Thus, individuals who perceive themselves to be adept in one of these domains may still be lacking in others (e.g., individuals who perceive high close friendship quality and are well-liked by their peers may lack feelings of broader social acceptance), and these perceptions may change across adolescence. Therefore, it is important to understand how these peer relationship contexts may differentially relate to outcomes of wellbeing.

Social anxiety

One such outcome that has been linked to adolescent peer relationships is social anxiety, which is anxiety resulting from the possibility or presence of negative personal evaluation in social situations (Schlenker and Leary, 1982). The development and maintenance of social anxiety can be explained through a psychosocial perspective, which aims to conceptualize the ways that individual and environmental social experiences can influence behavior (Chiu et al., 2021). Through a psychosocial lens, adolescent peer relationships may predict the development of social anxiety. Indeed, links between adolescent peer relationships (particularly early adolescent peer relationships) and social anxiety are well established in the literature. For example, researchers have identified links between early adolescent social acceptance, close friendship, and social anxiety, such that lower levels of social acceptance were related to higher levels of social anxiety for all participants, and lower levels of close friendship quality were related to higher levels of social anxiety but only for females (La Greca and Lopez, 1998; Pickerling et al., 2020). One study identified friendship quality as a buffer against the development of social anxiety when adolescents reported loneliness, peer victimization, and low social self-efficacy (Erath et al., 2010). In addition, cross-sectional several studies have also identified adolescent social acceptance and perceived likability from peers as predictors for the development of social anxiety (Oberle et al., 2010; Henricks et al., 2021). Taken together, these findings suggest that adolescent peer relationships may play an important role in the development of social anxiety; however, more research is needed to understand the long-term effects of these adolescent peer relationships on social anxiety.

Depression

Aspects of adolescent peer relationships have been extensively studied in accordance with the development of depressive symptoms. For example, one study demonstrated that adolescents between the ages of 14 and 17 who reported feeling accepted from their peers had less depressive symptom severity (Adedeji et al., 2022). Another study found that having negative qualities in best friendships and feeling victimized by peers predicted depression in adolescents between the ages of 14 and 19 (La Greca and Harrison, 2010) Indeed, many of these studies are limited by their cross-sectional design, making it difficult to discern whether links between adolescent peer relationships and depression persist overtime. However, when taken together, the findings that poor quality adolescent peer relationships can predict adolescent depression, and the findings that adolescent depressive symptoms can predict adult depression (Pine et al., 1999), suggest that it is worthwhile to consider whether adolescent peer relationships have any direct and longitudinal effects of depression in adulthood.

Aggression

The influence of peer relationships in adolescence on externalizing behaviors, or acting out behaviors (e.g., aggression, risk taking, defiance, and substance misuse), has been extensively studied in the literature. Findings from prior studies suggest that positive peer relationships serve as protective factors for externalizing behavior, while negative peer relationships or interactions (e.g., peer pressure and peer victimization) can act as risk factors for the development of externalizing behavior problems (Van Hoorn et al., 2017; Peake et al., 2013; Poulin et al., 1999). Indeed, several studies have resulted in findings that suggest that low quality peer relationships can lead to long-term challenges with externalizing problems that persist across development (Jager et al., 2015; Kupersmidt et al., 1995). Prior research has identified certain characteristics of adolescent relationships (e.g., poor parent-child relationship quality, exposure to peers with antisocial personality traits, limited social problem-solving abilities, peer rejection, and peer pressure) that predict aggressive behavior later in life (Goodnight et al., 2017; D'zurilla et al., 2003; Conger et al., 2015); however, these studies do not specifically consider adolescent peer relationships as a direct predictor of aggression in adulthood. These findings suggest that adolescence is a key time period in which peer relationships may precede the development of aggressive behavior in adulthood; however, more research is needed to understand the role of psychosocial influences on the development of aggression later on.

Social integration

Very little research has been conducted to identify predictors of adult social integration (i.e., sense of belonging), despite the transition to adulthood being one marked by many role transitions (e.g., career, marriage, parenthood) that can be stressful and aversive without social support or adaptive coping mechanisms (Arnett, 1997). Social integration is thought to be acquired through friendships, and it is posited to protect against loneliness while promoting comfort, security, pleasure, and a sense of identity (Weiss, 1974; Cutrona and Russell, 1987). Prior research has demonstrated that social support can act as a buffer for stress occurring in the context of these adult role transitions (Spencer and Patrick, 2009), and it should be considered that adults who do not perceive themselves to be socially integrated may not have the resources or capacities to develop a network for social support. Further, one study found that friendships were the most important relationship context (compared to family and romantic relationships) in buffering against the effects of stress on loneliness in adulthood (Lee and Goldstein, 2016) Another study found that the development of empathy in adolescence was predictive of a number of social competencies, including social integration, in adulthood (Allemand et al., 2015). Notably, one adolescent relationship context in which empathy is developed is through a close friendship with a peer (Miklikowska et al., 2022; Portt et al., 2020). As such, more research is needed to understand factors that predict social integration in adulthood and to understand whether the influences of high-quality peer relationships in adolescence persist into adulthood.

Romantic insecurity

The importance of both romantic and non-romantic social relationships is emphasized in the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Indeed, the transition to adulthood is marked by an increased interest in finding a romantic partner to settle down and spend life with together (Furman and Rose, 2015; Arnett, 1997). Findings from existing research suggest that satisfaction in romantic relationships predicts long-term overall wellbeing, while romantic relationship conflict and insecurity predicts increased depression and overall life dissatisfaction (Roberson et al., 2018). Further, adaptive attachment patterns in romantic relationship, compared to friend attachment, has been found to mediate the relationship between parental attachment and life-satisfaction in emerging adults, suggesting that feelings of success in romantic relationships are of heightened importance during the transition to adulthood (Guarnieri et al., 2015). Therefore, it is important to understand factors that contribute to romantic relationship satisfaction vs. insecurity in adulthood. Prior research has provided evidence to suggest that aspects of adolescent peer relationships (e.g., social competence, the ability to form and maintain strong close friendships) can predict success in adult romantic relationships (Allen et al., 2020). Another study revealed similar findings, providing evidence that early adolescents who perceived themselves as being well-liked by their peers and having close friends were more likely to explore romantic relationships in emerging adulthood, while early adolescents who were less integrated with their peers showed later involvement in adult romantic relationships (Boisvert and Poulin, 2016). An Italian study yielded similar findings, with additional evidence to suggest that both early and late adolescent peer relationships influence romantic relationship exploration and satisfaction in adulthood (Dhariwal et al., 2009). Collectively, these findings suggest that the competencies that are built and practiced through adolescent peer relationships may translate to other relationship contexts, such as adult romantic relationships. As such, it is important to also examine whether having limited opportunities to practice skills necessary to be successful in adolescent peer relationships can have an inverse effect, leading to greater romantic insecurity in adulthood.

Job satisfaction

Links between job satisfaction and wellbeing are well established in the literature, as studies have shown that individuals who are more satisfied with their jobs show higher levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and positive affect (Bowling et al., 2010). In fact, efforts to promote achievement and satisfaction in the workforce (otherwise known as “career readiness”) often begin during adolescence, where teens have the opportunity to practice skills relevant to career readiness, including problem-solving, decision-making, collaboration, cooperation, and responsibility (Marciniak et al., 2022). One area in which adolescents may have the opportunity to develop and practice these skills is in the context of their peer relationships. As such, the links between adolescent peer relationships and job satisfaction have been explored in the literature. One study found that positive adolescent behavior (including belonging to peer groups) predicted educational attainment, job complexity and income, and job satisfaction, suggesting that teens who have more opportunities to engage in positive behaviors in adolescence, which could include having high quality peer relationships, are better positioned to have job satisfaction later in life (Converse et al., 2014). Similar findings were yielded from studies examining the role of adolescent peer relatedness in career development and job satisfaction, suggesting that adolescents who were more attached to their peers were protected against the effects of anxiety on job satisfaction and were more willing to commit to a preferred career path (Miles et al., 2018; Felsman and Blustein, 1999). A Taiwanese study revealed a relationship between loneliness and workplace satisfaction in adulthood, in addition to finding that positive perceived peer relationships in early adolescence predicted decreased risk of social loneliness (Chiao et al., 2022). These findings suggest that adolescent peer relationship contexts may provide opportunities for adolescents to develop skills that can promote career readiness and job satisfaction; however, more research is needed to understand the specific developmental stages and peer relationship contexts that are most influential in the development of these skills.

Physical health

The aforementioned markers of adult wellbeing are highly relevant to social-emotional and psychological functioning. Indeed, an overwhelming amount of research suggests that psychological and physical functioning are linked, such that individuals with impairments and distress in one aspect of functioning likely have impairments and distress relevant to the other as well (Gianaros and Wager, 2015; Hernandez et al., 2018; Ohrnberger et al., 2017). Further, both physical and psychological health are considered to be important aspects of adult wellbeing (Halleröd and Seldén, 2013). Therefore, it important to also seek to understand the influence of adolescent peer relationship contexts on future physical health outcomes. One Italian study found that adolescents who perceived higher levels of peer support were more likely to engage in physical activity, which could have positive effects for later physical health (Pierannunzio et al., 2022). These long-term benefits of positive adolescent peer relationships are demonstrated across the literature, with one study showing that early adolescents who reported higher levels of close friendship quality and adherence to social norms predicted higher levels of physical health quality in adulthood, even after controlling for potential confounds (Allen et al., 2015). One study found that adult-reported somatic symptoms were higher in individuals who reported greater dissatisfaction with peers at age 16 (Landstedt et al., 2015). Indeed, another study found that 16-year-old adolescents with greater levels of peer conflict had higher rates of metabolic syndrome in adulthood (Gustafsson et al., 2012). Links between adolescent peer relationships and adult physical health outcomes are well-established, although more research is needed to understand the role of developmental timing and peer relationship contexts on these associations.

The present study

There is an undeniable need for research aimed at examining peer relationships at different points of adolescence as predictors of adult wellbeing in a longitudinal model. Prior literature examining associations between adolescent peer relationships and wellbeing is limited, as the majority of studies examine the effects of adolescent peer relationships at only one point of time and are limited to only one distinct peer relationship context. Thus, the present study seeks to build upon prior research and theory by seeking to understand the contexts under which peer relationships during both early and late adolescence predict various markers of wellbeing in adulthood. In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the links between peer relationship contexts and markers of wellbeing, friendship quality, social acceptance, and perceived likability from peers will be examined at both early and late adolescence to determine whether or not developmental timing can provide an explanation for the relative importance of these peer relationship contexts when predicting adult wellbeing. It is hypothesized that when considered together, self-perceived social acceptance during early adolescence and close friendship quality during late adolescence will emerge as the most robust predictors of markers of wellbeing in young adulthood. It is suspected that success in these types of relationships at these ages may lay a foundation for success in future endeavors that necessitate getting along well with others in both group and individual contexts, which are likely central components of the outcomes examined.

Methods

Participants and procedure

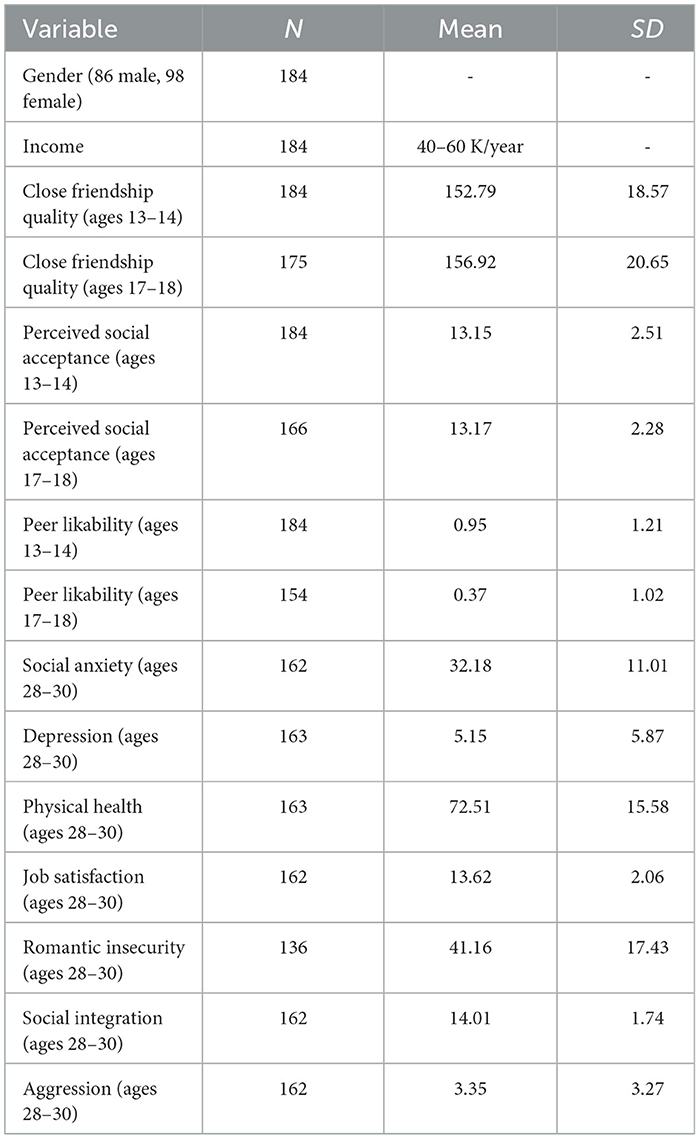

The sample for this study includes 184 participants (86 male, 98 female) who were part of a larger longitudinal study of adolescent/young adult social and emotional development. This sample included participants from a variety racial and ethnic backgrounds (107 Caucasian, 53 African American, 2 Hispanic/Latino, 2 Asian American, 1 American Indian, 15 mixed ethnicities, and 4 “other”). The median socioeconomic annual income for the families of the participants was between $40,000 and $59,000 when the study began in 1999. Participants were recruited though an initial mailing to all parents of students in the 7th and 8th grades who attended a public middle school in the Southeastern United States near the researchers' home institution. Through this mailing, parents were given the opportunity to opt out of any further participation in the study (N = 298). Only 2% of parents opted out of participation. Of the remaining families that were then contacted by phone, 63% were both eligible and willing to participate in the study. The sample used in the study appeared to reflect the overall population of the school in terms of racial and ethnic makeup (42% non-white in sample and 40% non-white in school) and socio-economic status (mean household income of $43,618 in sample compared to $48,000 in the school community in 1999). The participants and their peers completed assessments on an annual basis throughout the adolescent developmental time period. Participants completed assessments again during young adulthood in order to assess outcomes longitudinally. The current study uses several waves of measurement in order to more robustly capture the developmental periods of interest; scores on measures of dyadic close friendship quality, self-perceived social acceptance, and peer-reported likability were averaged at 13 and 14 (early adolescence) and at ages 17 and 18 (late adolescence), and scores on measures representing various markers of wellbeing were averaged at ages 28, 29, and 30 (young adulthood). Moreover, the current study controls for all study outcome variables at age 18, in addition to gender and income.

All procedures were approved by the university's ethics review board. Adolescents and their peers provided informed assent, and their parents provided informed consent before each interview session. Once participants reached age 18, they provided informed consent. In the initial introduction and throughout each session, confidentiality was explained to all family members, and adolescents were told that their parents would not be informed of any of the answers they provided. A Confidentiality Certificate, issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, protected all data from subpoena by federal, state, and local courts. Participants were compensated and, when necessary, transportation and childcare were provided to participating families.

Measures

Gender

Participants were asked to report on their gender (male or female) at the beginning of the study. Gender was coded as a binary variable (1 = Males, 2 = Females), as guidelines for gender-inclusive language were not indicated at the beginning of data collection.

Annual household income

Participants were asked to report their annual household income at the beginning of the study.

Adolescent peer relationship contexts

The Friendship Quality Questionnaire (FQQ) is a 40-item self-report questionnaire that was used to measure dyadic close friendship quality during early and late adolescence. The FQQ quantifies the teen's perception of their friendship quality with a close peer (Parker and Asher, 1993). The FQQ measures friendship quality in six different domains: validation and caring (e.g., “We make each other feel important and special”), conflict resolution (e.g., “We talk about how to get over being mad at each other”), conflict and betrayal (e.g., “She sometimes says mean things about me to other kids”), help and guidance (e.g., “We share things with each other”), companionship and recreation (e.g., “We always play together or hang out together”), and intimate exchange (e.g., “We talk about how to make ourselves feel better if we are mad at each other”). The FQQ was given to teens and their closest friend during early and late adolescence. Reports from the teen and their close peer were averaged together to create a new variable to represent dyadic close friendship quality. Items were scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true; 5 = really true), where higher scores indicated stronger friendship quality. The FQQ was found to be a reliable and valid measure of friendship quality (Parker and Asher, 1993). Alphas were 0.95 for age 13–14 assessments and ranged from 0.95 to 0.97 at age 17–18 assessements.

Self-perceived social acceptance was also measured during early and late adolescence with the social acceptance subscale of the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1998). Teens were asked during early and late adolescence to choose between two contrasting stem items related to social acceptance and then rate that item as either “sort of true” or “really true” about themselves or their friend (e.g., “some teens do have a lot of friends, but some teens don't have a lot of friends”; “some teens are popular with other kids their age, but some teens are not popular with kids their age”; “some teens feel that they are accepted by other kids their age, but some teens feel that they are not accepted by other kids their age”). This rating process resulted in a four-point scale for each item (1 = really true for me; 2 = sort of true for me; 3 = sort of true of me; 4 = really true for me), where higher scores on any item is indicative of higher perceived social acceptance. Alphas ranged from 0.78 to 0.79 for age 13–14 assessments and ranged from 0.77 to 0.81 at age 17–18 assessements.

A measure of Peer Sociometrics was used to measure peer-reported likability during early and late adolescence. Each adolescent, their closest friend, and two other target peers named by the adolescent were asked to nominate up to 10 peers in their grade with whom they would “most like to spend time on a Saturday night” and an additional 10 peers in their grade with whom they would “least like to spend time on a Saturday night.” The assessment of popularity by asking youth to name peers with whom they would actually like to spend time has been validated with both children and adolescents (Bukowski et al., 1993). This study used grade-based nominations (e.g., students could nominate anyone in their grade at school), rather than classroom-based nominations due to the age and classroom structure of the school that all participants attended. As a result, instead of friendship nominations being done by 15 to 30 children in a given classroom, each teen's nominations were culled from among 72 to 146 teens (depending on the teen's grade level). These nominators comprised approximately 38% of the entire student population in these grades. All participating students in a given grade were thus potential nominators of all other students in that grade, and an open nomination procedure was used (i.e., students were not presented with a roster of other students in their school, but instead wrote in names of liked and disliked students). Students used this procedure easily, producing an average of 9.1 liking nominations (out of 10). The raw number of ‘like' nominations each teen received was converted to a z-score within grade level (so that differences in number of nominators in different grades would not bias results) as a measure of desirability as a social companion in the broader peer group following the procedure described in Coie et al. (1982). This approach to assessing social acceptance has been previously found to yield ratings that are stable over time and related to adolescent attachment security, qualities of positive parental and peer interactions, and short-term changes in levels of deviant behavior (Allen et al., 2005, 2007; McElhaney et al., 2008).

Markers of wellbeing

The Social Anxiety Scale (SAS) is a 22-item scale that was used to measure participants' perceptions of social anxiety during young adulthood (La Greca, 1998). Participants were asked to rate each item on a 5-point scale according to how much the item “is true for you” (1 = not at all true, 2 = hardly ever true, 3 = sometimes true, 4 = true most of the time, 5 = always true). Studies have found the SAS to be a reliable and valid measure of adolescent social anxiety, specifically with regard to its internal consistency of its subscales, test-retest reliability, and overall construct validity (La Greca and Lopez, 1998; Inderbitzen-Nolan and Walters, 2000; Storch et al., 2004). Moreover, the SAS has been found to be positively correlated with other measure items related to trait anxiety, depression, and social phobia lending discriminant and concurrent validity for the use of the SAS with a non-clinical, adolescent population (Inderbitzen-Nolan and Walters, 2000; Storch et al., 2004).

Young adult depression was measured using the Beck Depression (Beck et al., 1961). The BDI consists of 21-items where the participant is asked to rate characteristics of depression on a scale of 0–3, where higher scores indicate a larger intensity of depressive characteristics (e.g., 0 = “I do not feel sad,” 1 = “I feel sad,” 2 = “I am sad all of the time and I can't snap out of it,” 3 = “I am so sad and unhappy that I can't stand it”; 0 = “I get as much satisfaction out of things as I used to,” 1 = “I don't enjoy things the way I used to,” 2 = “I don't get real satisfaction out of anything anymore,” 3 = “I am dissatisfied or bored with everything”). The BDI is considered to be both a reliable and valid measure of depressive symptoms (Beck et al., 1961). Alphas ranged from 0.89 to 0.92.

The aggression subscale of the Adult Self Report (ASR; Achenbach and Rescorla, 2003) was used to measure aggression in young adults. The ASR is a 126-item self-report measure that is used to measure how adults perceive their behavior. The aggression subscale contains 16 questions to assess whether participants perceive themselves to use behavior that is physically and verbally aggressive. Items are rated on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = “Not True,” 1 = “Somewhat or Sometimes True,” 2 = “Very True or Often True”). Higher scores indicate higher levels of aggression. Alphas ranged from 0.82 to 0.85.

The social integration subscale of the Social Provisions Scale (SPS; Cutrona and Russell, 1987) was used to measure young adult social integration. The SPS is a 24-item measure that is used to assess various aspects of Weiss' (1974) social provisions. Each provision is assessed with four items: two that describe the presence and two that describe the absence of the provision. The social integration subscale measures the extent to which an adult feels a sense of belonging to a group that shares similar interests, concerns, and recreational activities. The subscale is scored on a 4-point scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree,” 4 = “Strongly Agree”) that reflects the extent to which each statement describes the participant's current social network. Higher scores on the subscale are indicative of higher levels of perceived social integration. Alphas ranged from.70 to. 85.

The general health problems subscale of the RAND 36-item Health Survey version 1.0 (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992) was used to measure young adult physical health. The general health problems subscale includes 5 items that broadly assess perceptions of physical health status in young adults. Participants are asked to rate their health on a scale where higher ratings indicate a more favorable health state (e.g., “In general, would you say your health is: poor, fair, good, very good, excellent,” “I seem to get sick a little easier than other people: definitely true, mostly true, don't know, mostly false, definitely false”). Alphas ranged from 0.77 to 0.79.

The Multi-Item Measure of Adult Romantic Attachment (MAR; Brennan and Shaver, 1998) was used to measure young adult romantic insecurity. The measure provides scores on scales of avoidance and anxiety in romantic relationships, which were then summed together to create a measurement of romantic insecurity. Participants were asked to rate items related to adult romantic attachment on a 7 point scale (1 = “disagree strongly,” 4 = “neutral/mixed,” 7 = “agree strongly). Higher scores are indicative of higher levels of romantic insecurity. Alphas ranged from 0.93 to 0.94.

Young adult job satisfaction was measured using the job competence subscale of the Adult Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1998). Young adults were asked to choose between two contrasting items related to job competence and then rate that item as either “sort of true” or “really true” about themselves. This rating process resulted in a four-point scale for each item (1 = really true for me; 2 = sort of true for me; 3 = sort of true of me; 4 = really true for me), where higher scores on any item is indicative of higher perceived job satisfaction and competence. Example items include “Some adults are satisfied with the way they do their work; Some adults are proud of their work.” Alphas ranged from 0.76 to 0.80.

Data analysis and interpretation

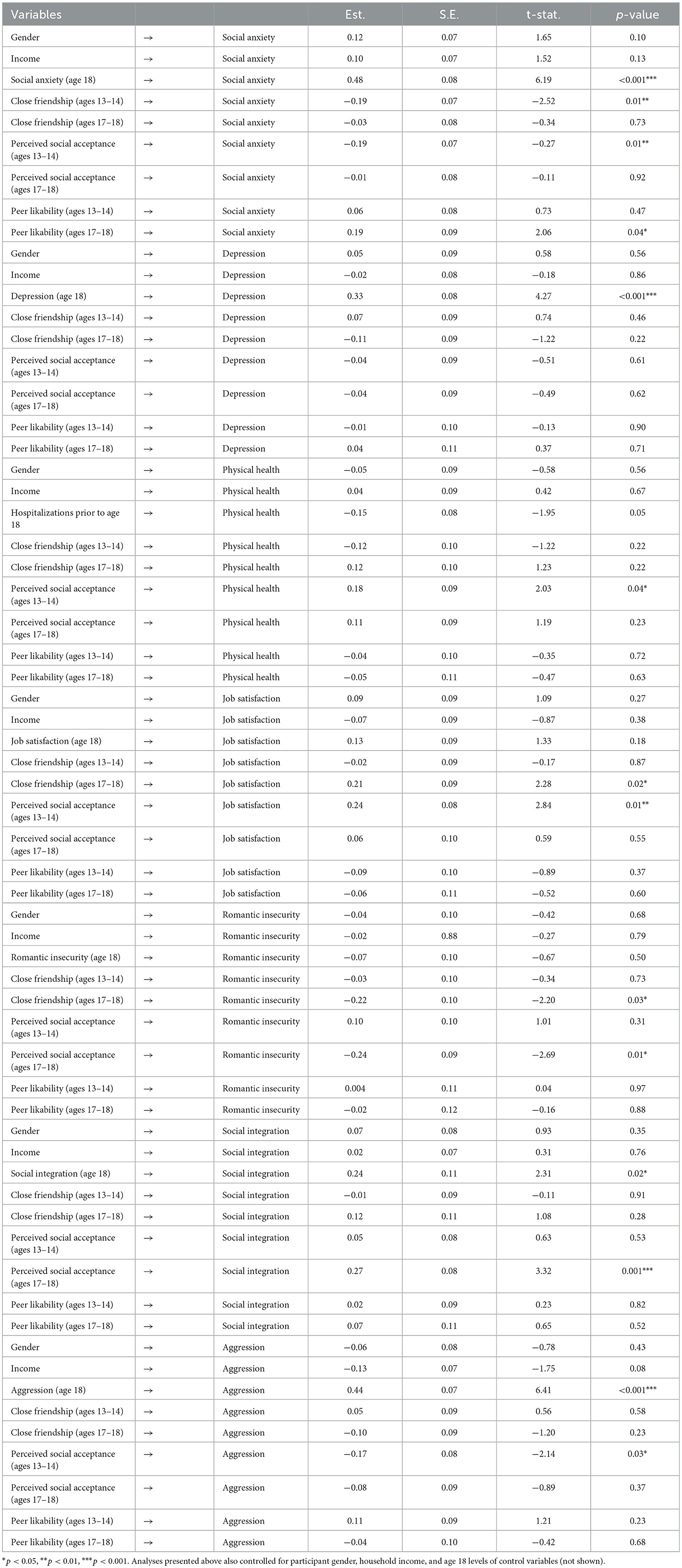

Data analysis was assisted through computer software (SAS 9.4). All analyses controlled for participant gender, household family income, and the wellbeing outcome variable of interest at age 18 (the measure for physical health was not available at age 18 and a proxy measure of “number of hospitalizations prior to age 18” was used instead). For descriptive purposes, simple univariate correlations were initially conducted to examine relationships between all variables of interest. A path analysis was then used to test the hypotheses of the study by simultaneously regressing outcome variables on the aforementioned measures of close dyadic friendship, self-perceived social acceptance, peer-reported likeability, gender, income, and age 18 control variables to account for the correlations between these variables. Alternative analyses testing hypotheses by examining individual hierarchical regression equations yielded nearly identical results. Because it was not the intention of this study to identify a causal model of wellbeing in young adulthood, results are presented in terms of individual predictors of outcomes from early and late adolescence. Post-hoc power estimates indicate that 80% power would be obtained for standardized estimates equal or >0.23. Age 18 control variables were often significantly predictive of their respective outcome variables in the analyses: Social Anxiety at 18 to Social Anxiety at 28–30 (β = 0.48, p < 0.001); Depression at 18 to Depression at 28–30 (β = 0.32, p < 0.001); Childhood Hospitalizations by 18 to Physical Health at 28–30 (β = −0.15, p = 0.05); Job Satisfaction at 18 to Job Satisfaction at 28–30 (β = 0.11, ns); Physical Attractiveness at 18 to Romantic Insecurity at 28–30 (β = −0.09, ns); Attachment to Peers at 18 to Social Integration at 28–30 (β = 0.21, p < 0.05); Aggression at 18 to Aggression at 28–30 (β = 0.43, p < 0.001). Thus, significant results often indicate a relative increase or decrease in levels of the outcome constructs over time after accounting for the auto-regressive paths.

Attrition analyses

Attrition analyses indicated that there were no differences on age 13–14 predictor variables with regard to later close friendship quality, self-perceived acceptance, and peer likability, with one exception: missing data for peer likability at age 17–18 were associated with lower close friendship scores at age 13/14 (M = 146.3 vs. 154.0; t = −2.11, p = 0.04). For outcome data at age 28–30, participants with missing data had lower close friendship scores at ages 17–18 (M = 144.1 vs. 158.4; t = −2.84 p < 0.001) and, interestingly, higher self-perceived acceptance scores at ages 13–14 (M = 14.2 vs. 13.01); t = 2.97; p < 0.01). Finally, participants without a romantic partner at ages 28–30 had lower close friendship scores at ages 17–18 (M = 150 vs. 159.3; t = −2.66 p < 0.01). To address missing data in longitudinal analyses, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used with analyses, including all variables that were linked to future missing data (i.e., where data were not missing completely at random). These procedures have been found to yield least biased estimates when all available data are used for longitudinal analyses (vs. listwise deletion of missing data; Arbuckle, 1996; Mueller and Hancock, 2010). Thus, the full sample of 184 participants was included in analyses.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Univariate and correlational analyses

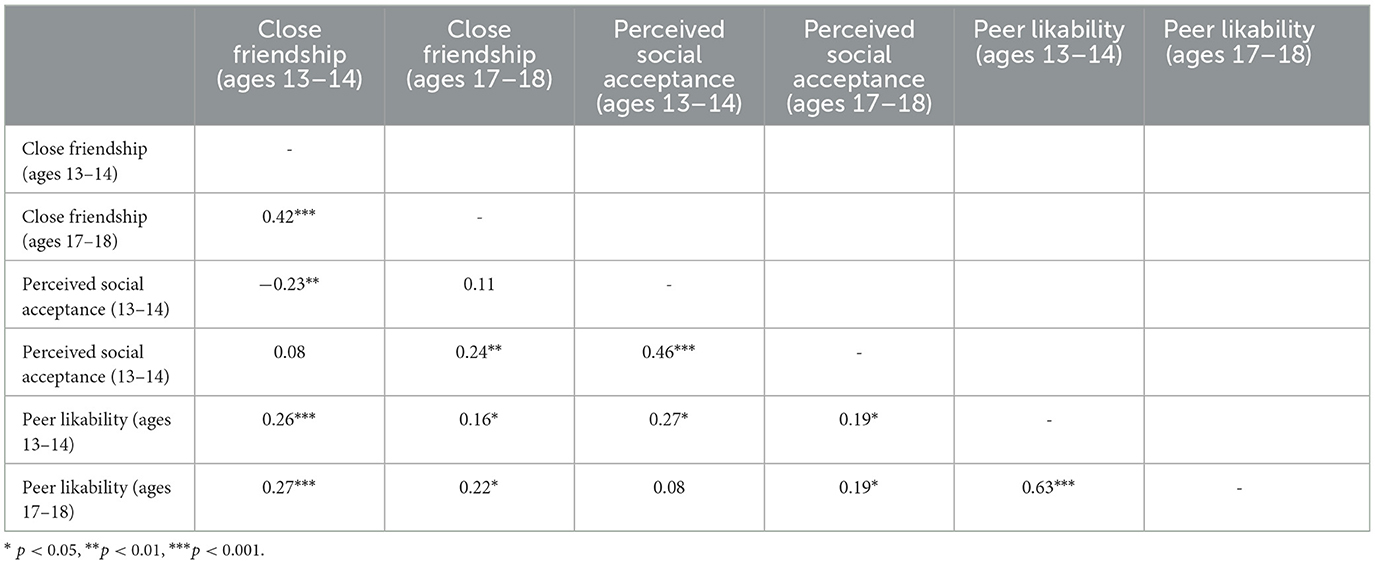

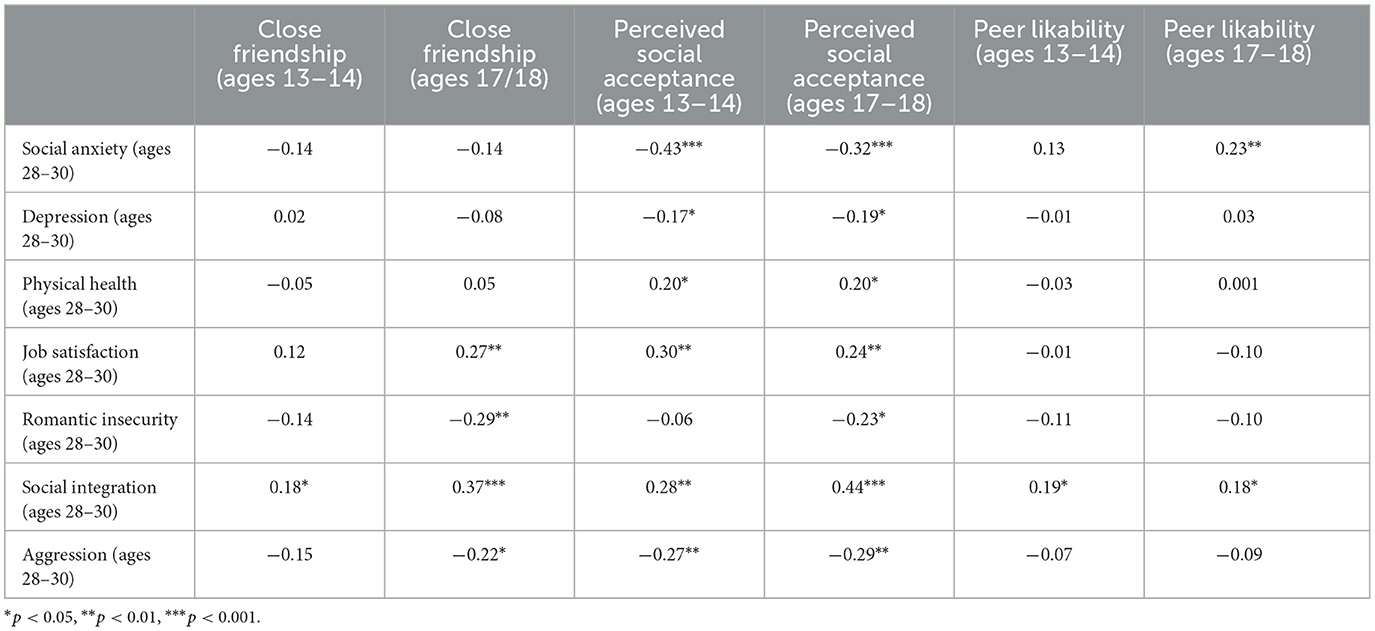

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all primary variables are presented in Tables 1–3. Correlation analyses revealed significant associations between several of the predictor and outcome variables. Early adolescent dyadic friendship quality was positively correlated with young adult social integration (r = 0.18, p = 0.02), such that higher quality early adolescent friendships were related to higher levels of young adult social integration. Late adolescent dyadic friendship quality was positively correlated with young adult job satisfaction (r = 0.27, p < 0.001) and young adult social integration (r = 0.37, p < 0.0001). Late adolescent dyadic friendship quality was negatively correlated with romantic insecurity (r = −0.29, p < 0.001) and aggression (r = −0.22, p = 0.01), such that higher quality late adolescent friendships were related to lower levels of romantic insecurity and aggression in young adulthood.

Perceived social acceptance in early adolescence was positively correlated with better physical health (r = 0.20, p = 0.01), job satisfaction (r = 0.30, p < 0.001), and social integration (r = 0.27, p < 0.001), and it was negatively correlated with social anxiety (r = −0.43, p < 0.001), depression (r = −0.17, p = 0.03), and aggression (r = −0.27, p < 0.001). Perceived social acceptance in late adolescence was also positively correlated with physical health (r = 0.20, p = 0.01), job satisfaction (r = 0.24, p < 0.01), and social integration (r = 0.43, p < 0.001), and it was negatively correlated with social anxiety (r = −0.32, p < 0.001), depression (r = −0.19, p = 0.02), and romantic insecurity (r = −0.23 p = 0.01), and aggression (r = −0.29, p < 0.001).

Early adolescent peer likability was positively correlated with social integration (r = 0.19, p = 0.02). Late adolescent peer likability was positively correlated with social integration (r = 0.18, p = 0.03) and social anxiety (r = 0.23, p = 0.01), such that higher levels of peer likability in late adolescence was related to higher levels of social anxiety in young adulthood.

Primary analyses

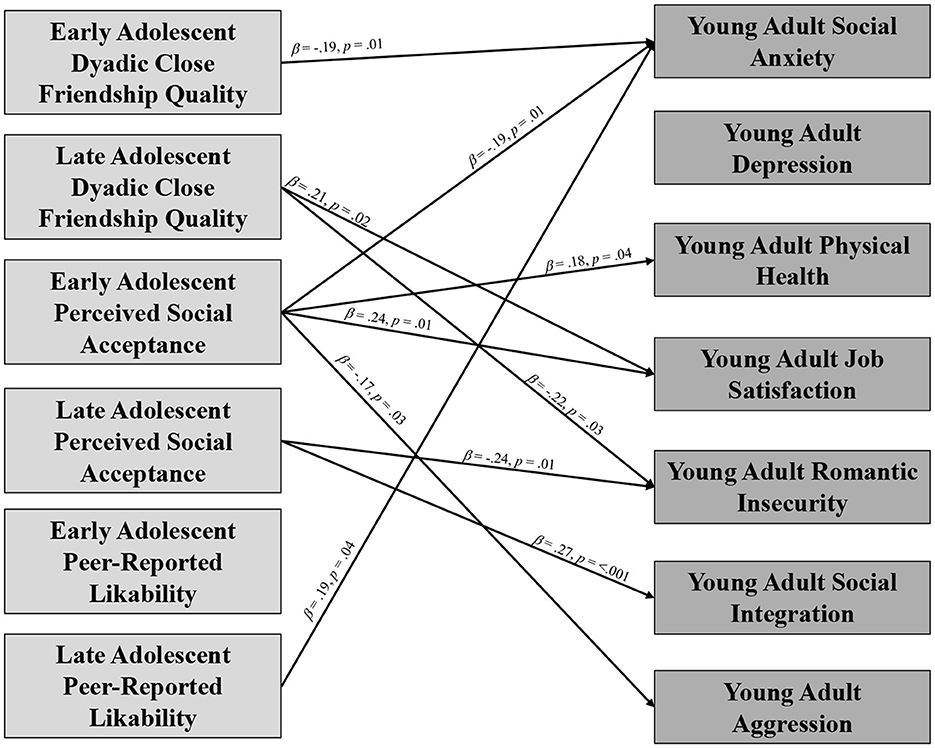

Results from the path analysis revealed several significant direct effects, which can be found in Table 4 and are illustrated in Figure 1. High quality early adolescent dyadic close friendship quality was predictive of lower levels of young adult social anxiety (β = −0.19, p = 0.01), while high quality late adolescent dyadic close friendship quality was predictive of greater young adult job satisfaction (β =0.21, p = 0.02) and less romantic insecurity (β = −0.22, p = 0.03).

Table 4. Path analysis predicting young adult wellbeing (ages 28–30) from adolescent peer relationship contexts.

Figure 1. Heuristic representation of predictions to young adult wellbeing (ages 28–30) from adolescent peer relationship contexts. Analyses presented above also controlled for participant gender, household income, and age 18 levels of control variables (not shown).

Higher levels of early adolescent perceived social acceptance was predictive of lower levels of social anxiety (β = −0.19, p = 0.01), higher levels of physical health quality (β = 0.18, p = 0.04), higher levels of job satisfaction (β = 0.24, p = 0.01), and lower levels of aggression (β = −0.17, p = 0.03). Higher levels of late adolescent perceived social acceptance was predictive of lower levels of romantic insecurity (β = −0.24, p = 0.01) and higher levels of social integration (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) in young adulthood.

Higher levels of late adolescent peer likability predicted higher levels of social anxiety in young adulthood (β = 0.19, p = 0.04). Of note, none of the adolescent peer relationship contexts examined predicted young adult depression, and early adolescent peer likability did not predict any outcomes related to young adult wellbeing.

Discussion

The present study hypothesized long-term associations between adolescent peer relationships and young adult wellbeing. Specifically, we hypothesized that, when considered together, self-perceived social acceptance during early adolescence and close friendship quality during late adolescence would emerge as the most robust predictors of markers of wellbeing in young adulthood. Hypotheses were based on previous research and theory suggesting that the developmental characteristics of early and late adolescence may be implicated in the links between adolescent peer relationships and later wellbeing (Brinthaupt and Lipka, 2002; Erikson, 1968). In contrast to our hypotheses, results suggest that certain adolescent peer relationship contexts may be differentially linked to outcomes of wellbeing depending on the relevance of the peer relationship context to the wellbeing outcome. However, overall, the results generally support the hypotheses and suggest that broader social acceptance may have distinct predictive effects in early adolescence, while close friendship quality may have distinct predictive effects in late adolescence. Results related to the context of peer relationships across adolescence and the developmental timing of those relationships are described in turn below.

Of the three adolescent peer relationship contexts examined, perceived social acceptance appeared to be the best predictor of outcomes related to adult wellbeing across adolescence, which is an unexpected finding given the conclusions drawn from prior research. With the exception of depression, perceived social acceptance emerged as a predictor of all wellbeing outcomes, suggesting that adolescents who perceive themselves to be well-liked by their peers may have less social anxiety, report better physical health, be more satisfied with their job and romantic relationships, feel more connected socially, and use less aggression as they progress through young adulthood. These results are conflicting, given that much of the existing literature emphasizes the importance of having a high-quality close friendship (relative to the importance of perceived acceptance from a broader range of peers). For example, findings from one study suggest that intimate close friendships are more predictive of psychological adjustment in adolescence than popularity (Townsend et al., 1988). Another study revealed findings that dyadic friendship experiences in adolescence, relative to feelings of popularity, were more influential in predicting adolescent loneliness and depression (Nangle et al., 2003). High quality friendships have also been shown to buffer against the effects of low social acceptance and low quantity of friends on maladjustment in adolescence (Waldrip et al., 2008). Taken together, findings from these studies emphasize the importance of close friendship during the adolescent time period relative to other peer relationship contexts. Notably, however, most of the aforementioned studies are limited by cross-sectional designs, suggesting that though close friendship might be a more relevant predictor of adjustment and wellbeing during adolescence, perceived social acceptance may be more important in the long-term. Results from the present study therefore demonstrate the importance of examining long-term outcomes of adolescent peer relationships to draw more comprehensive conclusions about the influence of those peer relationship contexts throughout development.

Dyadic close friendship quality predicted outcomes of social anxiety, romantic insecurity, and job satisfaction. This could suggest that there is something unique about the more intimate nature of close friendships that allows adolescents to practice skills that are relevant to forming successful one-on-one relationships later on, such as with a job supervisor or romantic partner. Further, certain aspects of these high-quality close friendships may be uniquely reinforcing, protecting against the impact of negative cognitive biases and self-perceptions on the development of social anxiety later in life (Kenny, 1994; Christensen et al., 2003). Thus, it is possible that perceived social acceptance and close friendship quality fulfill distinct needs during the adolescent time frame. For example, the feeling of being liked by many peers may reinforce certain behaviors such as kindness or humor, while high-quality close friendships may provide opportunities for validation and thoughtful feedback.

Notably, peer likability across adolescence was a poor predictor of adult wellbeing. Importantly, peer likability was the only relationship context assessed using only the report of other peers. Dyadic close friendship quality was measured using reports from both the adolescent and their closest friend and social acceptance was measured purely using self-report. This could suggest that an individual's own perception of their success in close friendships and amongst peers more broadly may have distinct importance in predicting outcomes relevant to wellbeing. Said differently, the perceptions of others may not distinctly influence later wellbeing if the individual has positive perceptions of themselves and their social relationship contexts.

Though findings from this study suggest that the context of adolescent peer relationships may predict adult wellbeing, results also indicate that the developmental timing of the relationships should be considered as well. Early adolescent dyadic close friendship quality and perceived social acceptance were both predictive of young adult social anxiety. This suggests that perceptions of success during the early adolescent time period may prevent the development of social anxiety later on. Perceptions of success in early adolescent peer relationship contexts may be more influential in predicting later social anxiety because the early adolescent period is characterized by a transition of teens relying more heavily on their peers than parents for social support. Therefore, experiences in peer relationships during the early adolescent time period that are more intensely adverse or successful may leave a larger imprint on the teen during this transition than if the experiences were to happen later on in adolescence. Indeed, higher levels of peer likability in late adolescence were predictive of higher levels of social anxiety in adulthood. It is possible that teens who are well-liked by their peers are more susceptible to increased social demands and/or pressure. When considered together with the developmental timing of late adolescence (where teens are preparing to transition to adulthood), excess social demands and pressure may lead feelings of imposter syndrome, which can contribute to social anxiety (Kolligian and Sternberg, 1991; Fraenza, 2016; Holden et al., 2024).

Early, but not late, adolescent social acceptance was predictive of adult outcomes of better physical health, increased job satisfaction, and decreased aggression. Links between early stress and adult physical health suggest that perceptions of social acceptance early in adolescence may protect individuals from the negative effects of stress on physical health. Indeed, puberty is one particular stressful life event that occurs during the early adolescent time period. As such, youth who perceive themselves as being accepted by their peers while they are going through puberty (or other stressful events associated with early adolescence) may be protected against physical health-related concerns later on (Dorn et al., 2019). Further, early adolescents who are praised or reinforced for characteristics that make them feel socially accepted (e.g., kindness, warmth, consideration for others, humor, and problem-solving) may have more time to practice and generalize these skills before they enter the workforce (where the aforementioned skills are still relevant), leading them to feel more satisfied with their job. Considering the time elapsed between early adolescence and young adulthood as an opportunity to practice and generalize skills important in adulthood may also help explain why early adolescent social acceptance predicts reduced aggression in adulthood. It could be that teens who feel more socially accepted in early adolescence feel reinforced for their positive traits (traits that can be seen as the antithesis of aggression), which prevent them from developing aggressive behaviors as potential coping skills or solutions for interpersonal conflict later on.

Late adolescent close friendship quality and perceived social acceptance did emerge as predictors for a few markers of adult wellbeing. Late adolescent close friendship quality predicted greater job satisfaction and less romantic insecurity. Given that late adolescence marks the transition from adolescence to adulthood, and that adulthood is often marked by heightened interest and exploration into romantic relationships and career opportunities, it seems intuitive that the benefits gained from intimate close friendships would translate to similar contexts in adulthood. Indeed, late adolescent social acceptance was also predictive of less romantic insecurity in adulthood, which could be explained by the relevance of identity exploration and formation during the late adolescent time period. Therefore, teens who perceive themselves as being more socially accepted in late adolescence as their identities are starting to form may feel more secure in romantic relationships as feelings of acceptance are embedded into their identity. Similar conclusions could be drawn when considering findings that late adolescent perceived social acceptance also predicted social integration in young adulthood, such that teens who integrate aspects of belongingness and acceptance into their identity may carry that with them through adulthood, lending to an increased sense of feeling integrated with the community.

Of note, depression was the only outcome that was not linked to any of the adolescent peer relationship contexts. Indeed, links between adolescent peer relationships and depression during adolescence are well established in the literature, suggesting that peer relationships may have a direct influence on depression when studied explicitly during adolescence. Findings from this longitudinal study suggest that the aforementioned links may be distinctly relevant when peer relationships and depression are studied at the same time. As such, a direct link between success in adolescent peer relationships and depressive symptoms in adulthood may not exist. This could be explained by theories about the etiology of depression onset, which suggest that certain biological (e.g., genetics, temperament), cognitive (e.g., negative thoughts about the self, the world, and the future), behavioral (e.g., behavioral deactivation), and/or situational (e.g., stress and stressors) factors may better predict the development of depression in adulthood (Roy and Campbell, 2013; Lisznyai et al., 2014). Thus, adolescent peer relationships may be better understood as potential risk and/or protective factors related to the onset of depression in adulthood. Therefore, future research may consider these adolescent peer relationships (and other related factors such as peer victimization or bullying) as potential mediators or moderators when trying to better understand causal factors relevant to depression.

Strengths and limitations

This study included several strengths, but perhaps most notable is its multi-method and longitudinal design, which provided the opportunity to examine the effects of adolescent peer relationships at different stages of adolescence to investigate developmental precursors of adult wellbeing. Importantly, the present study also used data from a non-clinical population, which allows for the conclusions drawn from results to be generalized to all individuals, regardless of whether or not they meet diagnostic criteria for any type of psychopathology. Lastly, to account for the dyadic nature of close friendship and the unilateral nature of social acceptance and peer likability, variables in the present study were chosen on the basis of this characterization (Asher et al., 1996). As such, scores from peer-report and self-report of close friendship quality were combined to create a new variable to represent dyadic close friendship quality, and social acceptance and peer likability were measured using scores from separate self-report and peer-report assessments. Notably, findings from this study mainly support the importance of self-reported social acceptance, which provides interesting evidence for the implication of an individual's own perception in predicting adult wellbeing.

In addition to its strengths, this study also had several limitations that are important to consider. Though longitudinal in nature, the present study is nonetheless correlational, preventing researchers from drawing causal conclusions from the data. In addition, conclusions drawn from this study are limited to self- and peer- report of all study variables. Future research may consider utilizing observational measures to strengthen the validity of the findings. Although this study controlled for earlier measurements of outcome constructs at ages 17–18, findings would be strengthened by including measurements of these constructs at ages 13–14 to help clarify the direction of the observed effects and create a more robust longitudinal design. Additionally, we did not always have the same outcome measure available at age 17–18 and had to use a proxy variable to represent physical health. Also, the measure of desirability as a peer companion is in some ways less robust than traditional peer preference measures, in that it only captured results from a minority of students (albeit a sizeable number) at each grade level. As expected, there was also some overlap in variance between our predictor variables which may make it slightly more difficult to discern the utility of each construct as unique predictor variables, though this overlap was often modest. Lastly, although findings from this study have important implications for understanding long-term effects of interpersonal experiences, data from the present study were collected prior to the heightened stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, caution is warranted when interpreting results, given that the long-term effects of these globally experienced and situational interpersonal stressors are still unknown and findings from the current study may or may not generalize to individuals who have been impacted by the pandemic.

Implications and future directions

The results from the present study have important implications for understanding factors that may contribute to adult wellbeing. Taken together, these findings provide support for conceptualizing adult wellbeing through an integrative model that considers psychosocial and developmental factors. Continued consideration of the importance of developmental timing will allow researchers to understand why certain psychosocial relationships are more relevant at certain times in an individual's life. As such, future research can expand on this study by considering additional types of psychosocial relationships (e.g., relationships with parents, caregivers, teaches, romantic partners, etc.) at different points of development (e.g., early, middle, and late childhood) that likely also contribute to young adult wellbeing. Future research should also consider other factors that might act as mediators or moderators that could play a role in adult wellbeing (e.g., other mental health symptoms, identity factors, adverse childhood experiences, coping mechanisms, interpersonal competency, and perception of the self).

Results from the current study also extend to practical application in the areas of parenting, schooling, and psychological practice. Individuals who work with adolescents to promote adjustment and wellbeing may gravitate toward an approach that emphasizes the importance of a few close friendships over feeling well-liked by many peers. However, the findings from this study suggest that it might be more worthwhile to consider the importance of the acquisition and maintenance of a broader sense of belonging among peers when working with adolescents. For example, caregivers of adolescents may consider providing their children with ample opportunity to engage with same-aged peers through extracurricular activities, teachers may consider designing lessons that allow students to work together in small groups or pairs or teaching students how to engage respectfully and confidently in class discussions, and psychological professionals may consider integrating social skills lessons into therapeutic practice. Moreover, skills related to competency in social relationships should be taught and characteristics that may promote social acceptance (e.g., kindness, humor, and consideration for others) should be reinforced at an early age to increase the likelihood that teens are set up for interpersonal success as they approach adolescence.

Conclusions

The present study aimed to examine the relative importance of distinct types of peer relationship contexts (i.e., dyadic close friendship, self-perceived social acceptance, and peer-reported likability) at different stages of adolescence to predict aspects adult wellbeing. Findings from this study suggest that, relative to dyadic close friendship quality and peer likability, perceived broader social acceptance may be a more robust indicator of future wellbeing outcomes. Results also suggest that broader social acceptance may be a better predictor of future wellbeing when examined during early adolescence, while close friendship quality may be a better predictor of future wellbeing when examined during late adolescence. Findings from the current study are representative of the complexity of understanding adult wellbeing as it relates to interpersonal and developmental factors, and they also provide important implications for understanding the potential risk and protective factors for that can be used to promote healthy psychological functioning throughout the lifespan.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Intitutional Review Board for the Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

ES: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. DS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JA: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health (5R37HD058305-23, R01HD058305, and F32HD102119). This work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund administered through the University of Arkansas Libraries.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Achenbach, T. M., and Rescorla, L. A. (2003). Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Adedeji, A., Otto, C., Kaman, A., Reiss, F., Devine, J., and Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2022). Peer relationships and depressive symptoms among adolescents: Results from the German BELLA study. Front. Psychol. 12:767922. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.767922

Allemand, M., Steiger, A. E., and Fend, H. A. (2015). Empathy development in adolescence predicts social competencies in adulthood. J. Pers. 83, 229–241. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12098

Allen, J. P., Narr, R. K., Kansky, J., and Szwedo, D. E. (2020). Adolescent peer relationship qualities as predictors of long-term romantic life satisfaction. Child Dev. 91, 327–340. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13193

Allen, J. P., Porter, M., McFarland, C., McElhaney, K. B., and Marsh, P. (2007). The relation of attachment security to adolescents' paternal and peer relationships, depression, and externalizing behavior. Child Dev. 78, 1222–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01062.x

Allen, J. P., Porter, M. R., McFarland, F. C., Marsh, P., and McElhaney, K. B. (2005). The two faces of adolescents' success with peers: Adolescent popularity, social adaptation, and deviant behavior. Child Dev. 76, 747–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00875.x

Allen, J. P., Uchino, B. N., and Hafen, C. A. (2015). Running with the pack: teen peer-relationship qualities as predictors of adult physical health. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1574–1583. doi: 10.1177/0956797615594118

Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). “Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data,” in Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques, eds. G. A. Marcoulides and R. E. Schumaker (Mahwah: Erlbaum), 243–278.

Arnett, J. J. (1997). Young people's conceptions of the transition to adulthood. Youth Soc. 29, 3–23. doi: 10.1177/0044118X97029001001

Asher, S. R., Parker, J. G., and Walker, D. L. (1996). “Distinguishing friendship from acceptance: implications for intervention and assessment,” in The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence, eds. W. M. Bukowski, A. F. Newcomb, and W. W. Hartup (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 366–405.

Baartmans, J. M., van Steensel, F. J., Mobach, L., Lansu, T. A., Bijsterbosch, G., Verpaalen, I., et al. (2020). Social anxiety and perceptions of likeability by peers in children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 38, 319–336. doi: 10.1111/bjdp.12324

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., and Erbauch, J. (1961). Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. doi: 10.1037/t00741-000

Berndt, T. J. (1998). “Exploring the effects of friendship quality on social development,” in The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence, eds. W. M. Bukowski, A. F. Newcomb, and W. W. Hartup (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 346–365.

Boisvert, S., and Poulin, F. (2016). Romantic relationship patterns from adolescence to emerging adulthood: associations with family and peer experiences in early adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 45, 945–958. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0435-0

Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., and Wang, Q. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 83, 915–934. doi: 10.1348/096317909X478557

Brennan, K. A., and Shaver, P. R. (1998). Attachment styles and personality disorders: their connections to each other and to parental divorce, parental death, and perceptions of parental caregiving. J. Pers. 66, 835–878. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00034

Brinthaupt, T. M., and Lipka, R. P. (2002). “Understanding early adolescent self and identity: an introduction,” in Understanding Early Adolescent Self and Identity: Applications and Interventions, 1–21. doi: 10.1353/book4525

Brown, B. B., and Larson, J. (2009). “Peer relationshipships in adolescence,” in Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development, eds. R. M. Lerner and L. Steinberg (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 74–103. doi: 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002004

Bukowski, W. M., Gauze, C., Hoza, B., and Newcomb, A. F. (1993). Differences and consistency between same-sex and other-sex peer relationships during early adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 29:255. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.29.2.255

Bukowski, W. M., and Hoza, B. (1989). “Popularity and friendship: Issues in theory, measurement, and outcome,” in Peer relationshipships in child development, T. J. Berndt and G. W. Ladd (New York: John Wiley and Sons), 15–45.

Chiao, C., Lin, K. C., and Chyu, L. (2022). Perceived peer relationships in adolescence and loneliness in emerging adulthood and workplace contexts. Front. Psychol. 13:794826. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.794826

Chiu, K., Clark, D. M., and Leigh, E. (2021). Prospective associations between peer functioning and social anxiety in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 279, 650–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.055

Christensen, P. N., Stein, M. B., and Means-Christensen, A. (2003). Social anxiety and interpersonal perception: a social relations model analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 41, 1355–1371. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00064-0

Cohen, S., Gottlieb, B. H., and Underwood, L. G. (2001). Social relationship and health: challenges for measurement and intervention. Adv. Mind Body Med. 17, 129–141.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., and Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: a cross-age perspective. Dev. Psychol. 18:557. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.18.4.557

Conger, R. D., Martin, M. J., Masarik, A. S., Widaman, K. F., and Donnellan, M. B. (2015). Social and economic antecedents and consequences of adolescent aggressive personality: predictions from the interactionist model. Devopment Psychopathol. 27, 1111–1127. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000711

Converse, P. D., Piccone, K. A., and Tocci, M. C. (2014). Childhood self-control, adolescent behavior, and career success. Pers. Individ. Dif. 59, 65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.007

Cutrona, C. E., and Russell, D. W. (1987). The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Adv. Personal Relation. 1, 37–67.

Dhariwal, A., Connolly, J., Paciello, M., and Caprara, G. V. (2009). Adolescent peer relationships and emerging adult romantic styles: a longitudinal study of youth in an Italian community. J. Adolesc. Res. 24, 579–600. doi: 10.1177/0743558409341080

Dorn, L. D., Hostinar, C. E., Susman, E. J., and Pervanidou, P. (2019). Conceptualizing puberty as a window of opportunity for impacting health and well-being across the life span. J. Res. Adolesc. 29, 155–176. doi: 10.1111/jora.12431

D'zurilla, T. J., Chang, E. C., and Sanna, L. J. (2003). Self-esteem and social problem solving as predictors of aggression in college students. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 22, 424–440. doi: 10.1521/jscp.22.4.424.22897

Erath, S. A., Flanagan, K. S., Bierman, K. L., and Tu, K. M. (2010). Friendships moderate psychosocial maladjustment in socially anxious early adolescents. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 31, 15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.05.005

Felsman, D. E., and Blustein, D. L. (1999). The role of peer relatedness in late adolescent career development. J. Vocat. Behav. 54, 279–295. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1998.1664

Fraenza, C. B. (2016). The role of social influence in anxiety and the imposter phenomenon. Online Learn. 20, 230–243. doi: 10.24059/olj.v20i2.618

Furman, W., and Rose, A. J. (2015). “Friendships, romantic relationships, and peer relationships,” in Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Socioemotional processes, eds. M. E. Lamb and R. M. Lerner (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 932–974. doi: 10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy322

Gianaros, P. J., and Wager, T. D. (2015). Brain-body pathways linking psychological stress and physical health. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 24, 313–321. doi: 10.1177/0963721415581476

Goodnight, J. A., Bates, J. E., Holtzworth-Munroe, A., Pettit, G. S., Ballard, R. H., Iskander, J. M., et al. (2017). Dispositional, demographic, and social predictors of trajectories of intimate partner aggression in early adulthood. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 85:950. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000226

Greenaway, K. H., Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., and Jetten, J. (2016). Social identities promote well-being because they satisfy global psychological needs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 46, 294–307. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2169

Guarnieri, S., Smorti, M., and Tani, F. (2015). Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Soc. Indic. Res. 121, 833–847. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0655-1

Gustafsson, P. E., Janlert, U., Theorell, T., Westerlund, H., and Hammarström, A. (2012). Do peer relations in adolescence influence health in adulthood? Peer problems in the school setting and the metabolic syndrome in middle-age. PLoS ONE 7:e39385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039385

Halleröd, B., and Seldén, D. (2013). The multi-dimensional characteristics of wellbeing: How different aspects of wellbeing interact and do not interact with each other. Soc. Indic. Res. 113, 807–825. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0115-8

Henricks, L. A., Pouwels, J. L., Lansu, T. A., Lange, W. G., Becker, E. S., and Klein, A. M. (2021). Prospective associations between social status and social anxiety in early adolescence. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 39, 462–480. doi: 10.1111/bjdp.12374

Hernandez, R., Bassett, S. M., Boughton, S. W., Schuette, S. A., Shiu, E. W., and Moskowitz, J. T. (2018). Psychological wellbeing and physical health: associations, mechanisms, and future directions. Emot. Rev. 10, 18–29. doi: 10.1177/1754073917697824

Hodgson, J. W., and Fischer, J. L. (1979). Sex differences in identity and intimacy development in college youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 8, 37–50. doi: 10.1007/BF02139138

Holden, C. L., Wright, L. E., Herring, A. M., and Sims, P. L. (2024). Imposter syndrome among first-and continuing-generation college students: the roles of perfectionism and stress. J. College Student Retent. 25, 726–740. doi: 10.1177/15210251211019379

Hussong, A. M. (2000). Perceived peer context and adolescent adjustment. J. Res. Adolesc. 10, 391–415. doi: 10.1207/SJRA1004_02

Inderbitzen-Nolan, H. M., and Walters, K. S. (2000). Social anxiety scale for adolescents: normative data and further evidence of construct validity. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 29, 360–371. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_7

Jager, J., Yuen, C. X., Putnick, D. L., Hendricks, C., and Bornstein, M. H. (2015). Adolescent-peer relationships, separation and detachment from parents, and internalizing and externalizing behaviors: linkages and interactions. J. Early Adolesc. 35, 511–537. doi: 10.1177/0272431614537116

Kenny, D. A. (1994). Interpersonal Perception: A Social Relations Analysis. New York: Guilford Press.