- Psychology Department, Roanoke College, Salem, VA, United States

Research on relational aggression in adolescents suggests it is in part driven by the desire to attain and maintain enhanced status among peers, and recent work also suggests certain forms of prosocial behaviors are similarly status-motivated. However, these associations are not well understood in young adults. In this short-term longitudinal study across 8 months (N = 215), we examined whether relational aggression and two forms of prosocial behaviors (altruistic and public) are related to social goals for popularity and preference, social status insecurity, and self-perceptions of status (in terms of dominance and prestige) concurrently and over time in emerging adults (age 18–25). Social goals for popularity predicted increases in relational aggression and public prosociality and were negatively related to and predicted decreases in altruistic prosociality. Preference goals were concurrently negatively related to relational aggression and to public prosociality and were positively related to and predicted increases in altruistic prosociality over time. Social status insecurity moderated links between self-perceptions of status and aggressive/prosocial behaviors, which were largely non-significant without considering status insecurity. Finally, tests of indirect effects suggest that aggression and prosociality mediate associations between popularity goals and self-perceptions of dominance. Findings suggest that strategic use of aggression and prosociality may not be developmentally limited to adolescence.

Introduction

Aggression and prosocial behaviors are each related to several important indices of social adjustment across ages, including one's social standing among peers. In particular, while aggression may promote rejection among peers, and prosociality acceptance among peers (e.g., Chávez et al., 2022), both of these are also linked to reputational status (popularity; e.g., Casper et al., 2020; Malamut et al., 2021). Further, research separating between forms of prosociality indicate divergence across forms in terms of relevance to social status and respective motivations (Findley-Van Nostrand and Ojanen, 2018). Social goals are important to understand in the context of status-oriented social behaviors because they help to explain the “why” of particular behaviors. However, most of the research linking relational aggression and specific forms of prosocial behaviors to social goals and related constructs has been conducted in child and adolescent samples, with few studies focusing on emerging adults. In this study, we examined social goals for popularity and social preference, social status insecurity, and self-perceptions of status in relation to relational aggression and self- and other-oriented forms of prosociality in emerging adults across two time points (8 months apart).

Social status goals and relational aggression

The peer status literature differentiates between popularity as a reputational form of status and social preference, which entails interpersonal likeability and acceptance (Cillessen and Rose, 2005; see van den Berg et al., 2020 for a meta-analysis). The literature on social goals, in turn, also generally separates across goals capturing multiple dimensions. For instance, based on the interpersonal circumplex model of personality, social motivations and forms of status can be understood in terms of where they fall on the orthogonal dimensions of agency (status, self-focus) and communion (closeness, focus on others; Locke, 2015; Ojanen et al., 2005). Collectively, this research suggests that both peer status and striving for respective aspects of status among peers show different associations with social behaviors like aggression and prosociality. Presently, we focus on emerging adults' relational aggression and forms of prosociality.

Relational aggression entails harming others via social means, such as gossiping, rumor spreading, exclusion, or social manipulation (Crick and Grotpeter, 1995). In adolescent research, relational aggression is related to social status, and specifically popularity, concurrently and over time (Cillessen et al., 2014; Cillessen and Mayeux, 2004; Ojanen and Findley-Van Nostrand, 2014). Accordingly, these and related findings suggest that relational aggression can serve a function of status attainment and maintenance despite also eliciting negative peer reactions (e.g., Hawley, 2003, 2014; Reijntjes et al., 2018). Indeed, across studies with varying conceptualizations of social goals, adolescents who report striving for agentic, status-oriented goals, popularity goals, and goals for social dominance score higher in relational aggression and increase in their relational aggression over time (e.g., Dawes and Xie, 2014; Ojanen and Findley-Van Nostrand, 2014; Wright et al., 2012; see Hensums et al., 2023 and Samson et al., 2012 for meta-analyses). Youth who strive for social preference or closeness with others in turn score lower in different forms of aggression and higher in prosocial behaviors (e.g., Li and Wright, 2013; Salmivalli et al., 2005; Samson et al., 2012).

Relational aggression emerges early in the lifespan (Crick et al., 2006; Tremblay, 2000) and seems to peak in late childhood and early adolescence (though few studies have examined long-term developmental trends; Voulgaridou and Kokkinos, 2023), where most of the research in this area has focused. However, relational aggression is also important to understand in emerging adults. Emerging adulthood is a time of increased autonomy and maturity following adolescence. Yet, like adolescence, it is also characterized as a unique time of transition, identity development, and enhanced focus on social relationships (Arnett, 2014; Arnett et al., 2014). Voulgaridou and Kokkinos (2023) describe more sophisticated social understanding, enhanced negative consequences of more physical forms of aggression, and increased importance of social standing to one's self and identity as reasons to focus on adolescents' relational aggression (see also Card et al., 2008; Yoon et al., 2004). Conceivably, these factors are also present in emerging adults.

Most research examining relational aggression in young adults find links with several indices reflecting interpersonal problems and adjustment difficulties. For instance, relational aggression in young adults is related to heightened anxiety and anger (e.g., Dahlen et al., 2013; Goldstein et al., 2008), personality traits characterized by interpersonal difficulties (e.g., Ostrov and Houston, 2008), impulsivity, and hostile attribution bias (Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Chen et al., 2012). Importantly, being relationally victimized affects adjustment, anxiety, depression, and even psychophysiological factors like inhibited neural responses to rewards that might underlie anhedonia (Ethridge et al., 2018; Gros et al., 2010; Holterman et al., 2016; Werner and Crick, 1999). Further, while physical aggression is relatively low in prevalence in emerging adulthood, emerging adults report relational aggression as a common occurrence (Werner and Crick, 1999), perhaps given perceptions of relational aggression as socially normative (Nelson et al., 2008).

Recent research finds that emerging adults conceptualize popularity less in terms of aggression and more in terms of prosocial attributes than adolescents might (Lansu et al., 2023 O'Mealey and Mayeux, 2022). Yet, popularity is still positively correlated with relational aggression in young adults (Lansu and Cillessen, 2012; Ruschoff et al., 2015), who also report prioritizing status above other salient characteristics of social life (LaFontana and Cillessen, 2010). While the above reviewed research demonstrates relational aggression continues to be a problem in emerging adults and is linked to social cognitive deficits and other problems, this research has not thoroughly considered the social status perspective that has proved fruitful in adolescence. Thus, it is worthwhile to understand whether explicit motivations for popularity and social preference, as distinctive forms of status, may explain variation in relational aggression in emerging adults. Specifically, research finds that relational aggression affects adjustment also in emerging adults (Werner and Crick, 1999), and that social-cognitive factors like attributional biases and acceptability of aggression are risk factors for relational aggression (Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Goldstein et al., 2008). Thus, understanding social goals as potential risk factors for relational aggression provides an opportunity to inform efforts to promote more cohesive social relationships and thus buffer against impacted adjustment.

Forms of prosocial behaviors

Prosocial behaviors are usually examined globally and are positively associated with positive social adjustment and wellbeing (Eisenberg and Fabes, 1998), and negatively associated with aggression (Crick, 1996). Further, general prosocial behaviors have been found to be related to higher popularity (e.g., Lu et al., 2018) and communal goals among peers that can be considered prosocial in nature (Salmivalli et al., 2005). However, like aggression, prosociality should also be examined as multiple forms (see Carlo and Padilla-Walker, 2020) that may reflect differences in underlying social cognition. Along these lines, in a study distinctly considering proactive (self-oriented) prosocial behaviors as separate from those intended to benefit others, Boxer et al. (2004) found that proactive prosocial behaviors were positively correlated with and showed a similar pattern of correlates as aggression. Specifically, whereas altruistic forms of behaviors were related to normative beliefs about aggression, proactive prosociality was related to higher perceptions of aggression as normative (Boxer et al., 2004). These forms are also distinguishable from the perspective of peers; using both self- and peer-reported assessments of these forms in adolescents, youth who engage in altruistic prosociality report lower goals for peer status and higher goals for communion/closeness among peers and are well-liked by peers, whereas youth who engage in proactive prosociality report higher goals for peer status and are rated as more popular by peers (Findley-Van Nostrand and Ojanen, 2018).

Prosocial behaviors also take multiple forms beyond adolescence, based in part on the degree of self-interest underlying the behavior. Carlo and Randall (2002) developed an inventory capturing several subscales of prosociality, with multiple forms demonstrating unique associations with constructs like moral reasoning and empathy (Carlo et al., 2003; Mestre et al., 2019). This measure is widely used and considered reliable across sources (Reig-Aleixandre et al., 2023). In this study, we utilized the altruistic and public subscales of the Prosocial Tendencies Measures (Carlo and Randall, 2002) to examine whether these show differing associations with social goals, status insecurity, and self-perceptions of status. Presumably, prosociality primarily carried out in the presence of others is proactive in nature and thus more likely to be driven by strivings for heightened social status. Prosociality that is less directly observable by others (captured by the altruistic subscale items), in turn, is likely less related to popularity strivings as such behaviors would not afford reputational status. However, altruistic prosociality may be related to higher goals for social preference in part simply because of the general prosocial characteristics that align with this form of prosocial behaviors, which also lend themselves to being well-liked. Further, public and altruistic forms of prosociality should also demonstrate divergence in their relations with self-perceptions of social status: whereas public prosociality is likely related to higher status characterized by reputation or control over others, altruistic behaviors are likely related to higher indices of status that reflect interpersonal regard, likeability, and respect (Cheng et al., 2013; Maner and Case, 2016).

Social status insecurity

We also considered the role of social status insecurity, or the degree to which one feels a degree of concern or threat over one's social standing. Research on adolescents shows high social status insecurity is related to higher aggression (both overt and relational; Li et al., 2010; Li and Wright, 2013; Long and Li, 2020). Perhaps status is most likely to be defended (via aggression or strategic use of prosocial behaviors) by those who are preoccupied with the potential of losing it. While the role of social status insecurity in relational aggression and prosocial behaviors has, to our knowledge, not been examined in emerging adults, social psychological theory and findings support this expectation. For instance, research on threatened egotism demonstrates that self-esteem that is unstable, and narcissism (inflated self-perceptions that are themselves related to higher status goals; Findley and Ojanen, 2013) each drive aggression more than self-esteem level (see Baumeister et al., 2000). Further, relational insecurity or insecure attachment is also related to heightened aggression (e.g., Brodie et al., 2019). Presently, we examine the role of social status insecurity in relational aggression and forms of prosocial behaviors, and the role of social status insecurity in explaining links between these behaviors and self-perceptions of status. We expected status insecurity to drive relational aggression and public prosociality and be negatively related to altruistic prosociality (which is presumably based in concern for others and is conceptually independent of reputational status). Further, we expected that status insecurity would strengthen associations between aggression/prosociality and self-perceptions of status.

Present study

The research reviewed above suggests that both aggression and prosocial behaviors are in part explained by social status strivings and related constructs in adolescents. However, research focusing on the developmental uniqueness of emerging adults' relational aggression and prosocial behaviors has largely not considered the degree to which status is actively pursued in terms of social motives, or what the role of insecurity of one's status is in social behaviors. As relational victimization remains relevant to emerging adults' adjustment (Werner and Crick, 1999), understanding these mechanisms at this stage, especially longitudinally to capture even short-term development, is important.

In this study, we had three overarching aims. First, we sought to examine concurrent and longitudinal links between emerging adults' popularity and preference goals, social status insecurity, relational aggression, and forms of prosocial behaviors. Secondly, we aimed to examine whether self-perceptions of status were related to aggressive and prosocial behaviors concurrently and over time, and whether felt security of status may moderate these associations. While self-perceptions of status are qualitatively distinct from status perceived by a peer group or familiar others, they are reflective of one's sense of social standing and thus relevant to emerging adults' social behaviors. To test this aim, we assessed self-perceptions of dominance (status earned via coercion and fear) and prestige (status earned via respect or valuable skills; Cheng et al., 2010) to capture dimensions of status. We utilize the perspective of dominance and prestige as meaningful and distinctive forms of status among peers both because of their theoretical relevance to the social-cognitive and behavioral factors considered presently (see Cheng et al., 2010, 2013), and because of established and validated self-report scales capturing perceptions of status. In the peer status literature, status is most often peer-nominated and thus reflective of a general consensus in an established peer group. However, in emerging adults, capturing an established peer group is far more difficult as the school setting where peer nominations typically take place is far more fluid and variable than in earlier ages. Thus, we recognize that the self-perceptions of status captured presently are not an immediate parallel to existing work, yet they remain unexamined in association with the variables of interest and thus were expected to elucidate these mechanisms.

Regarding the first two aims, we generally expected that in line with agency and communion as reflective of overarching dimensions of cognition, motives, and behaviors (Abele and Wojciszke, 2014; Locke, 2015), constructs in each dimension would correlate and be predictive over time. That is, we expected popularity goals to predict higher relational aggression, public prosociality, and dominance, and preference goals to predict higher altruistic prosociality and prestige. Further, as discussed above, we expected that social status insecurity may moderate links between aggression/forms of prosociality and self-perceptions of status, as individuals insecure in their social standing may be most compelled to seek to affirm or sustain their sense of especially dominance. Third, we aimed to examine whether social goals are related to (self-perceptions of) status via social behaviors (relational aggression and prosocial forms). That is, do these behaviors mediate links between striving for and feeling like one has obtained status? Existing research has demonstrated that status goals predict popularity via behaviors like bullying and aggression (e.g., Ojanen et al., 2024). However, these mediated paths have not been tested in emerging adults, or with regards to multiple forms of prosocial behaviors.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

Participants (T1 N = 216; age 18–25, M = 21.7; SD = 2.24) were recruited via Academic Prolific, where they were compensated for their complete participation. On Prolific, the study was made available only to emerging adults between the ages of 18–25 who spoke English fluently, resided with the United States, and had an approval rating of 90% or higher. Participants provided informed consent for their participation, which included agreeing to be contacted for recruitment in follow-up time points. All data were anonymized and only linked to participants' Prolific ID in order to contact them securely via the platform's messaging system.

Participants included 117 women (53.9%), 91 men (41.9%), seven who identified as non-binary (3.2%), and one who identified outside of these gender options (0.5%), and 143 white (65.9%), 32 Asian (14.7%), 31 black or African American (14.3%), 30 Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish origin (13.8%), five Middle Eastern or Northern African (2.3%), and four American Indian or Native Alaskan (1.8%). 115 participants (53.0%) reported being currently enrolled in college. Participants were contacted via Prolific for a follow-up survey 8 months after they completed the initial study. For the second time point, there was an attrition rate of 44% (T2 N = 120). 74 women (61.7%), 40 men (33.3%), and five non-binary (4.2%) participants completed the second time point, for which they were also compensated. At T2, there were 78 white (65.0%), 18 Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish origin (15.0%), 18 Asian (15.0%), 16 black or African American (13.3%), four American Indian or Native Alaskan (3.3%), and three Middle Eastern, or Northern African (2.5%). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the first author's institution.

Measures

Popularity and preference goals

Popularity and preference goals were measured at T1 using an 11 item scale (Li and Wright, 2013; 1 = “Never” to 5 “Always”), with six items capturing popularity goals (e.g., “I want to be popular among my peers”; α = 0.86), and five capturing social preference goals (e.g., “I want to be well liked among my peers”; α = 0.82).

Social status insecurity

Social status insecurity was measured at T1 using the six-item Social Status Insecurity Scale (Li and Wright, 2013; 1 = “Never” to 5 “Always”; α = 0.88; e.g., “I worry about my popularity among my peers”).

Relational aggression

We used the Self Report of Aggression and Social Behavior scale (Murray-Close et al., 2010) to examine relational aggression. This measure includes subscales reflecting across proactive, reactive, and romantic forms. While conceptually distinct, we opted to collapse across the forms to form a single composite variable for three reasons. First, reactive and proactive forms can be difficult to distinguish (see, e.g., Bushman and Anderson, 2001; despite these showing discriminant validity when examined as general and not specifically relational aggression; e.g., Card and Little, 2006; Raine et al., 2006). Second, inspection of bivariate correlations between the three forms of aggression and the other study variables indicated few differences in associations (that is, both the magnitude and direction of correlations between aggression and goals, social status insecurity, and self-perceptions of status were the same across the forms). Finally, given the number of other aims of this study, reporting analyses across the forms was beyond the scope of this paper. The composite aggression variable was reliable at both timepoints (T1 α = 0.91 and T2 α = 0.90).

Prosocial behaviors

The Prosocial Tendencies Measure-Revised (Carlo et al., 2003) was used to measure prosocial tendencies in participants. This scale includes 23 items to assess six types of prosocial tendencies. For this study, we included public and altruistic subscales: four items for public (e.g., “I can help others best when people are watching me”; T1 α = 0.85, T2 α = 0.87), and five for altruistic [e.g., “I think that one of the best things about helping others is that it makes me look good.” (reverse-scored); T1 α = 0.79, T2 α = 0.81]. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Does not describe me at all”) to 5 (“Describes me greatly”).

Self-perceived social status

We used the self-report dominance and prestige scale (Cheng et al., 2010) to capture self-perceptions of status at T1 and T2. The scale consisted of 17 items assessing perceived dominance (e.g., “I enjoy having control over others”; T1 α = 0.85, T2 α = 0.86) and prestige (e.g., “Members of my peer group accept and admire me”; T1 α = 0.86, T2 α = 0.84). Items were on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 7 (“very much”).

Analysis plan

Our analysis plan can be separated into four sections: mean-level differences within and between participants; bivariate and unique associations between the study variables; moderation analysis to test the role of social status insecurity; and mediation analysis. First, to examine whether there were mean-level differences in the T1 and T2 study variables, we used paired sample t-tests. To explore whether there were any mean-level differences by gender or college student status, or whether those who participated at T1 but not T2 differed in their level of study variables, we used independent samples t-tests.

Secondly, we first examined associations among all study variables using bivariate correlations. We then used regression to examine unique associations focusing first on social goals, status insecurity, and relational aggression and forms of prosociality, and then focusing on self-perceptions of status and these behavioral variables. Tests of regression assumptions indicated no issues with multicollinearity based on correlations and low Variance Inflation Factors. There were also no issues with homoscedasticity (based on inspection of residual scatterplots) or linearity of associations (based on inspection of scatterplots). However, tests of normality indicated that, as is common in research on aggression, both T1 and T2 relational aggression scores were skewed positively. To account for this skew, we normalized these variables using the Rankit procedure (Soloman and Sawilowsky, 2009). Bivariate, unique, moderated, and mediated associations all used these scores.

Several regression models were conducted in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2017) using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimator to account for missing data via imputation. In the first set of cross-sectional models, T1 relational aggression, altruistic prosociality, and public prosociality variables were separately regressed upon popularity goals, preference goals, and social status insecurity. In the second set of longitudinal models, T2 relational aggression, altruistic prosociality, and public prosociality were each separately regressed upon social goals and status insecurity in addition to the T1 level of the respective behavior. Separate regression models were ran to examine the directional effects of self-perceptions of status (dominance and prestige) on relational aggression, altruistic prosociality, and public prosociality.

We also tested whether social status insecurity moderated these associations. Moderation tests were conducted using the Hayes Process macro (see Hayes, 2017), which tests interaction effects using three predictors (two main effects, and the interaction term entailing a product of the two main effect variables) on a given outcome. Where interaction terms were significant predictors of the outcome variable, follow-up analyses using tests of simple slopes (e.g., Aiken and West, 1991) were ran to examine under which levels (±1 SD) of social status insecurity were the predictor and outcome related.

Finally, tests of basic indirect effects to examine whether social goals were related to self-perceptions of status via relational aggression and prosocial behaviors were ran using Hayes Process macro with a bootstrap estimation approach using 5000 samples. Indirect effect tests were each conducted separately to examine whether each social goal (T1 popularity goals and preference goals) was related to each form of status (T2 dominance and prestige) via the behaviors of relational aggression, altruistic prosociality, and public prosociality (tested at both T1 and T2). Indirect effects of the predictor on the outcome via the mediator were considered significant if the confidence interval of the indirect effect did not include zero.

Results

Attrition tests and mean-level changes over time

One hundred twenty participants from T1 also completed the study at T2. To examine any potential differences between those who persisted and those who did not, we tested for mean-level differences on T1 variables. There were no significant differences between those who persisted in the study and those who didn't. We used paired sample t-tests to see if average levels of aggression, prosociality, and self-perceptions of status changed over time. Relational aggression scores decreased from the first to second time point (Mdiff = 0.07), paired t(119) = 16.98, p < 0.01, d = 1.55. No other measures differed in their mean level over time.

Differences by gender and college-student status

Means and standard deviations of the study variables can be found in Table 1. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine mean-level gender differences and differences by college student status. Women scored significantly higher in altruistic prosocial behavior at T1, t(206) = 2.27, p = 0.02, and T2, t(65.771) = 2.12, p = 0.038 (respectively, M = 4.19; SD = 0.69; M = 4.28; SD = 0.68) than men (M = 3.95; SD = 0.80; M = 3.95; SD = 0.86), while men scored higher in public prosocial behaviors at T1, t(171.301) = −3.33, p < 0.01, and popularity goals at T1, t(206) = −2.52, p = 0.01 (respectively, M = 2.09; SD = 0.95; M = 2.93; SD = 0.92) than women (M = 1.68; SD = 0.77; M = 2.62; SD = 0.89). There were no other gender differences. We also tested whether the variables differed in their average levels across participants currently in college or not. Popularity goals and self-perceptions of dominance at T1 were both higher in participants in college (respectively, M = 2.90; SD = 0.87; M = 3.00; SD = 1.03) than those not in college (M = 2.56; SD = 0.86; M = 2.68; SD = 1.09).

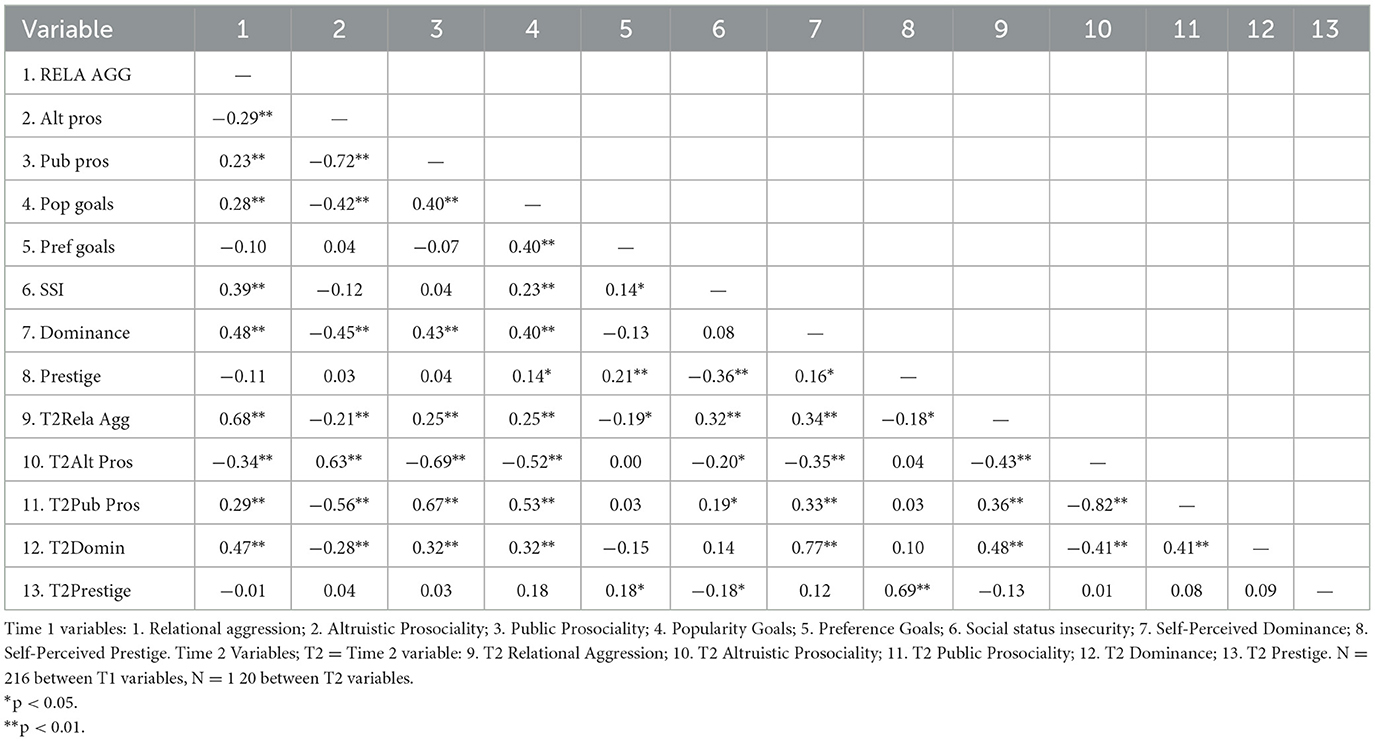

Social goals, status insecurity, relational aggression, and prosocial forms

Correlations among the study variables can be found in Table 1 and were mostly as expected (selected correlations are reiterated here and in the next section). T1 popularity goals were positively related to T1 and T2 relational aggression and public prosociality and negatively related to T1 and T2 altruistic prosociality. T1 social preference goals were unrelated to T1 relational aggression and unrelated to T1 public and altruistic prosociality, unrelated to T2 prosocial behaviors, and negatively related to T2 relational aggression. T1 social status insecurity was positively related to T1 and T2 relational aggression, unrelated to T1 altruistic and public prosociality, positively related to T2 public prosociality and negatively to T2 altruistic prosociality.

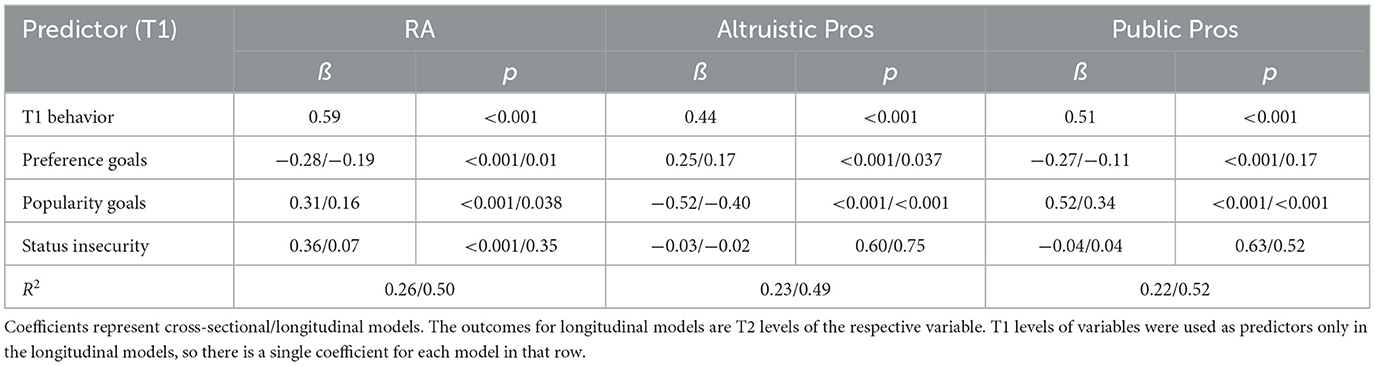

In order to examine the degree to which relational aggression and forms of prosociality were uniquely explained by popularity and preference goals and status insecurity, we regressed each of these behaviors onto the predictors in a cross-sectional model (using all T1) data, as well as in a longitudinal model in which the outcome variables were T2 assessments of behaviors, which were also regressed onto T1 level of each respective behavior. As seen in Table 2, T1 relational aggression and each form of prosociality predicted themselves over time. Popularity goals were concurrently positively related to and predicted increases in both relational aggression and public prosociality, and were concurrently negatively related to and predicted decreases in altruistic prosociality. Preference goals were concurrently positively related to and predicted increases in altruistic prosociality, were concurrently negatively related to and predicted decrease in relational aggression, and were concurrently negatively related to public prosociality (but not over time). Social status insecurity was concurrently positively related to and predicted increases in relational aggression over time, and was unrelated to both altruistic and public prosociality.

Table 2. Cross sectional and longitudinal associations: social goals, status insecurity, aggression, and prosociality.

Self-perceptions of status, relational aggression, and prosocial forms

In bivariate correlations, T1 relational aggression and T1 public prosociality were positively related to T1 and T2 dominance, and were unrelated to T1 and T2 prestige. Altruistic prosociality was negatively related to T1 and T2 dominance, and unrelated to T1 and T2 prestige. Given existing research demonstrating longitudinal bi-directional associations between forms of status and social behaviors like aggression and prosociality, we ran models testing associations with both directional paths (i.e., in the longitudinal models, from T1 self-perceptions of status to T2 behaviors, and from T2 behaviors to T2 self-perceptions of status). Despite research showing both aggression and peer status are mutually associated over time (using peer-nominated status rather than self-perceptions; e.g., Ojanen and Findley-Van Nostrand, 2014), these longitudinal associations were mostly non-significant, with the exception of one path that trended toward significance. T1 prestige was moderately negatively related to T2 relational aggression while controlling for T1 relational aggression and dominance (ß = −0.13, p = 0.09).

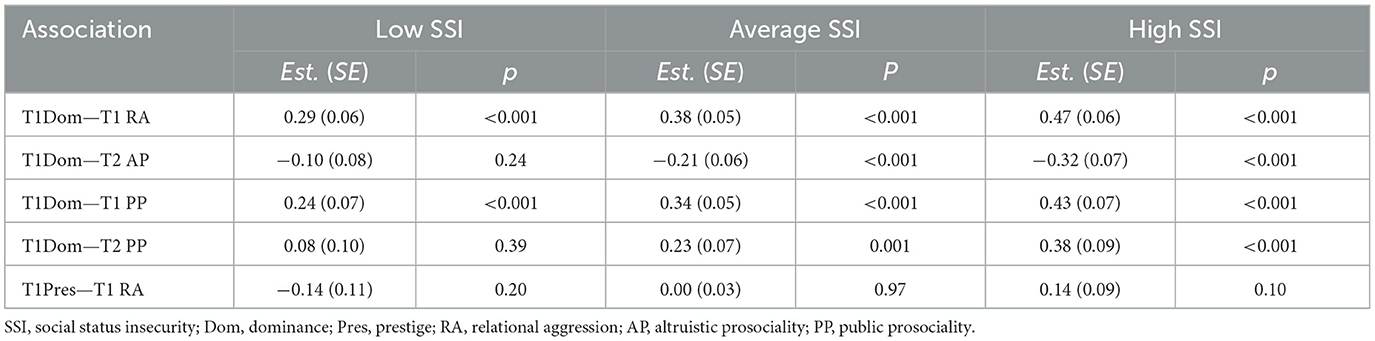

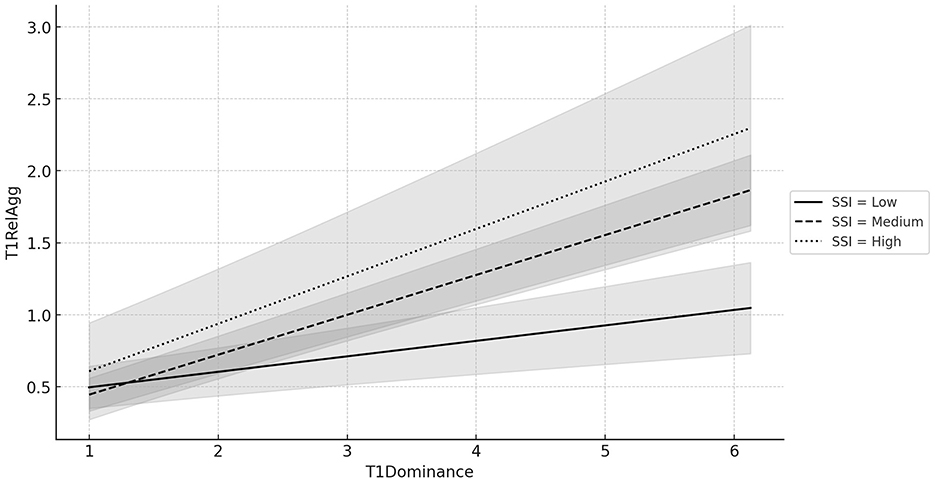

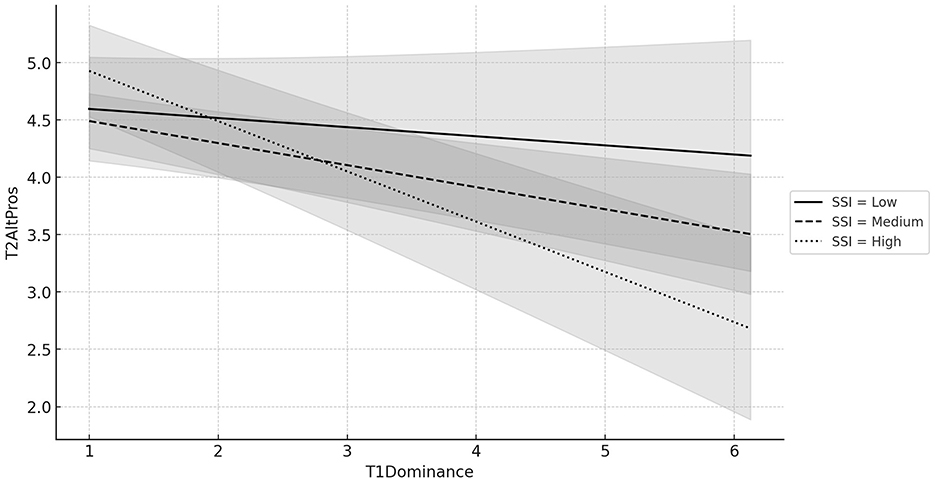

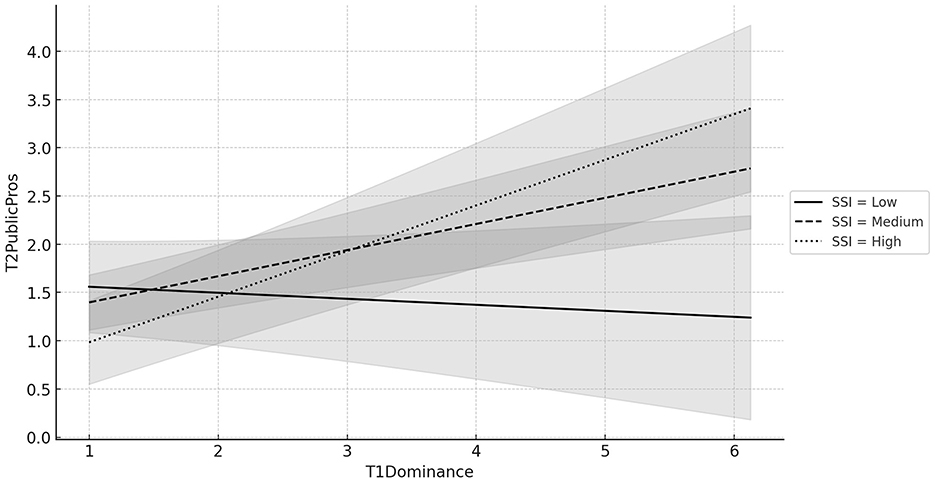

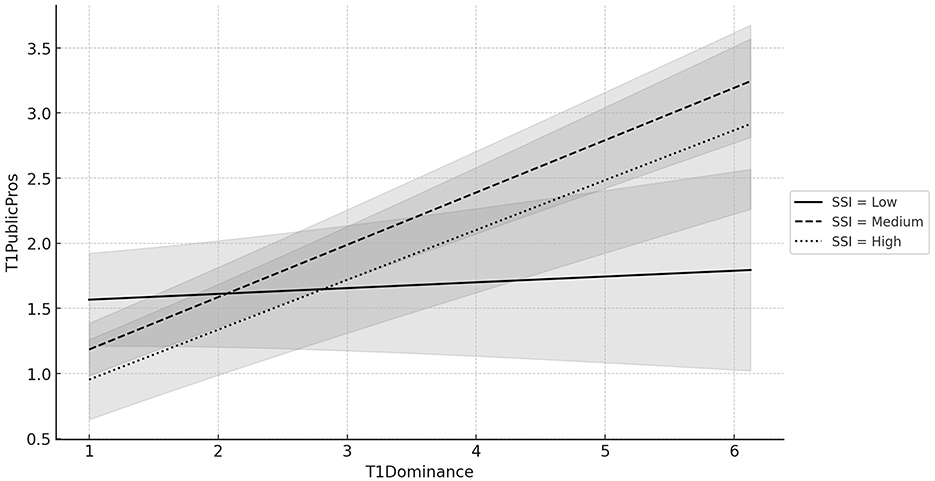

We also tested whether social status insecurity may moderate these associations by regressing each behavioral variable (Y) onto self-perceptions of status (A) and social status insecurity (B), as well as their interaction term (AxB). Several models tested indicated that, social status insecurity (B) moderated associations between T1 dominance (A) and T1 relational aggression (interaction estimate = 0.10, SE = 0.05, p = 0.04); T2 (but not T1) altruistic prosociality (interaction estimate = −0.13, SE = 0.06, p = 0.03); T1 public prosociality (interaction estimate = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = 0.03); and T2 public prosociality (interaction estimate = 0.17, SE = 0.07, p = 0.01). Simple slopes analysis testing associations between dominance and these social behaviors at different levels of social status insecurity indicated that in general, the association between self-perceptions of dominance and relational aggression or prosocial forms strengthen as participants' level of social status insecurity increases. For instance, dominance was unrelated to prosocial forms for participants low in social status insecurity, while these associations were significant for people both average and high in social status insecurity, and the strongest for people high in social status insecurity. See Table 3 for associations by low, average, and high social status insecurity, and see Figures 1–4 for graphical representations of the follow-up tests for significant interactions. For T1 relational aggression and public prosociality, dominance was positively related across levels of social status insecurity, but these associations differed in magnitude across levels (again, with the strongest being for high social status insecurity). Social status insecurity did not moderate any associations between self-perceptions of prestige and prosociality or T2 relational aggression, but it did moderate the association between T1 prestige and T1 relational aggression (interaction estimate = 0.16, SE = 0.07, p = 0.042). However, follow-up simple slope analysis indicated that when separating among those low, average, and high in social status insecurity, the associations between prestige and relational aggression became non-significant for each group (though for those high in social status insecurity, the effect was positive and trending toward significance, estimate −0.14, p = 0.10; for those low in social status insecurity, the effect was negative but non-significant).

Table 3. Moderation by social status insecurity: simple slopes results for significant interaction terms.

Figure 1. Simple slopes: association between T1 dominance and T1 relational aggression at low, average, and high levels of social status insecurity (SSI).

Figure 2. Simple slopes: association between T1 dominance and T1 public prosociality at low, average, and high levels of social status insecurity (SSI).

Figure 3. Simple slopes: association between T1 dominance and T2 public prosociality at low, average, and high levels of social status insecurity (SSI).

Figure 4. Simple slopes: association between T1 dominance and T2 altruistic prosociality at low, average, and high levels of social status insecurity (SSI).

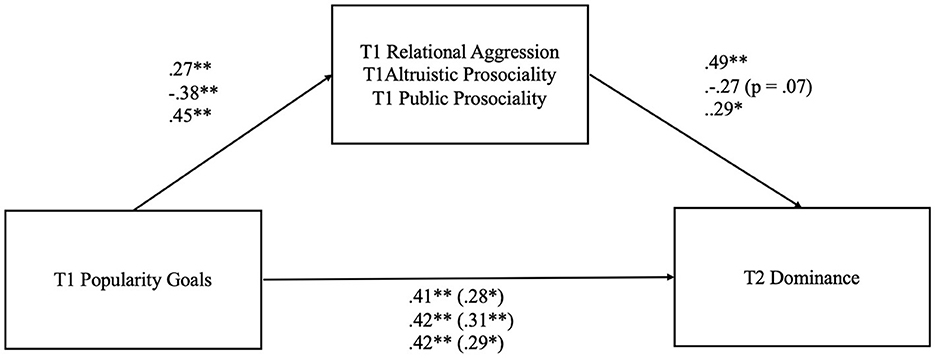

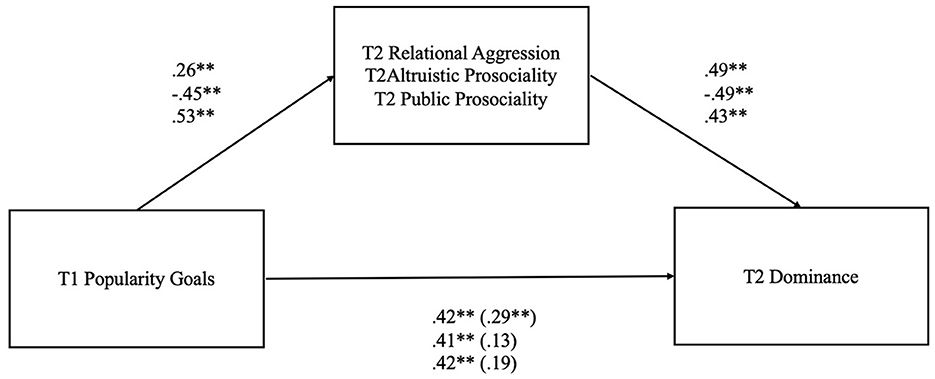

Tests of indirect associations

We were also interested in testing whether relational aggression and forms of prosociality mediated links between social goals and self-perceptions of status. That is, based on empirical and theoretical accounts of social cognition (goals) underlying behaviors (aggression and prosociality), which in turn drive responses from peers (status; e.g., Crick and Dodge, 1994), we expected that relational aggression and forms of prosociality would mediate links between popularity/preference goals and dominance and prestige. We tested several basic mediation models in which T1 popularity or preference goals were used as a predictor, T1 and T2 social behavior variables were used as mediators, and T2 self-perceptions of status were used as outcomes. All indirect paths from T1 popularity goals and T1 preference goals to T2 prestige via T1 or T2 aggression and prosociality were non-significant. All indirect paths from T1 preference goals to T2 dominance were also non-significant. T1 popularity goals predicted T2 dominance via: T1 relational aggression (indirect effect estimate = 0.13, SE = 0.05, CI = 0.04–0.24); T1 public prosociality (indirect effect estimate = 0.13, SE = 0.06, CI = 0.01–0.26); T2 relational aggression (indirect effect estimate = 0.13, SE = 0.05, CI = 0.03–0.24); T2 altruistic prosociality (indirect effect estimate = 0.22, SE = 0.08, CI = 0.08–0.39); and T2 public prosociality (indirect effect estimate = 0.23, SE = 0.08, CI = 0.07–0.39). See Figure 5 for coefficients of associations in the model including T1 social behaviors, and Figure 6 for coefficients of associations in the model including T2 social behaviors.

Figure 5. Tests of indirect effects from T1 popularity goals to T2 dominance via T1 social behaviors. Each row of coefficients represents a different model (1 = including T1 relational aggression as M; 2 = including T1 altruistic prosociality as M; 3 = including T1 public prosociality as M). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Figure 6. Tests of indirect effects from T1 popularity goals to T2 dominance via T2 social behaviors. Each row of coefficients represents a different model (1 = including T1 relational aggression as M; 2 = including T1 altruistic prosociality as M; 3 = including T1 public prosociality as M). **p < 0.01.

Discussion

Research on peer status and aggression during adolescence is voluminous and growing. However, an understanding the role of peer status in both aggression and prosocial behaviors in emerging adults is just emerging. In this study, we demonstrated that social goals for popularity and social preference among peers are related to and predict changes in relational aggression and both self- and other-oriented forms of prosocial behaviors across 8 months in emerging adults. The results align with and depart from expectations and existing research in some ways. However, they suggest that striving for popularity, a known predictor of relational aggression and forms of bullying in youth (e.g., Dawes and Xie, 2014; Dumas et al., 2019; Ojanen and Findley-Van Nostrand, 2014) continues to be a risk factor for relational aggression in emerging adults. Further, the results also suggest that forms of prosocial behaviors should be understood separately, especially as they pertain to peer status strivings which show divergent links with self- or other-oriented behaviors. Given that relational victimization has implications for negative adjustment in emerging adults (e.g., Gros et al., 2010; Holterman et al., 2016), further understanding these behaviors is important.

Relational aggression and prosocial behaviors: associations with social goals

We found that popularity goals predicted heightened relational aggression and public prosociality, and predicted lower altruistic prosociality, concurrently and over time in emerging adults. This is in line with expectations based on adolescent research linking status-oriented social goals to both aggression and self-serving/proactive prosocial behaviors (Dawes and Xie, 2014; Findley-Van Nostrand and Ojanen, 2018; Ojanen and Findley-Van Nostrand, 2014). While emerging adults may conceptualize popularity distinctively and more prosocially relative to younger populations (Lansu et al., 2023), the finding that popularity goals predict behaviors that have previously been linked to heightened status in youth suggests that at least for some, aggression and prosociality are perceived to serve the purpose of establishing popularity. This is in line with developmental accounts of processes that form and sustain status hierarchies (Hawley, 2014), which have also been established in young adults (Cheng et al., 2010). Further, our findings are also in line with work finding overlap between proactive use of prosocial behaviors and aggression in adolescents (Boxer et al., 2004); in this study, relational aggression was positively correlated with public prosociality at T1 and T2.

Outside of research focusing on peer relationships, emerging adult relational aggression has been tied to cognitive and interpersonal issues such as hostile attribution bias, disordered personality, and anger (e.g., Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Ostrov and Houston, 2008). Meanwhile, relational aggression has also been described as “adaptive” in that it serves a social hierarchical function of status (Hawley, 2003 Volk et al., 2015), a proposition which may at face value seem contradictory. However, these lines of research may be less contradictory and more reflective of either different perspective of the same behaviors, or different underlying etiologies that are not yet well understood.

Rectifying these viewpoints is an area for future study, but with regards to the current findings, it could be that as popularity becomes distinct in emerging adulthood, those who continue to conceptualize and strive for popularity along the lines of the more adolescent-normative view themselves experience a profile of social skill deficits that lead to aggressive behavior intended to serve one's reputation. Emerging adults who strive for social preference, as more reflective of being generally liked and held in high regard by others, are less likely to use relational aggression and instead are more genuinely prosocial. Indeed, in this study social preference goals were negatively related to and predicted decreases in relational aggression and were positively related to and predicted increases in altruistic prosociality over time. Thus, in terms of social motivational strategy, emerging adults who value social preference seem to be most likely to engage in behaviors that would facilitate generally cohesive peer relationships. This is in line with adolescent research, which has found that social goals for communion, closeness, and preference are related to lower aggression and higher prosociality (e.g., Findley-Van Nostrand and Ojanen, 2018; Salmivalli et al., 2005).

Our results also found that while social preference goals were negatively related to public prosociality in concurrent data, this longitudinal association was non-significant. Thus, while the general pattern of correlates with relational aggression seemed to also be found with public prosociality, this may be less true of social preference goals. Perhaps some emerging adults who strive for preference may expect proactive use of prosocial behaviors to facilitate this aim, while others are less inclined to consider prosocial behaviors in terms of self-interest. Research differentiating between public and altruistic prosociality finds these are inversely related to moral reasoning and other social cognitive constructs (e.g., Carlo et al., 2003). In general, understanding more about the social motivational profile of those who engage in a variety of forms of prosocial behaviors is warranted.

Social status insecurity and self-perceptions of status

In this study, status insecurity was concurrently positively related to and predicted increases in relational aggression over time. This is consistent with adolescent research, which has found that higher status insecurity is related to overt and relational forms of aggression (Li et al., 2010; Li and Wright, 2013; Long and Li, 2020). This finding was as expected based on adolescent research specifically examining insecurity in social status, but also research demonstrating more general links between relational insecurities and aggression (e.g., Brodie et al., 2019). Contrary to expectations, social status insecurity was unrelated to prosocial behaviors. While status insecurity being independent of altruistic prosociality is logical given the nature of altruism, which is in theory other-oriented and not rooted in striving for status, we expected public prosociality to be higher in people who may be insecure about their social standing, as these behaviors could conceivably reaffirm status. However, while not directly related to prosocial behaviors over time, social status insecurity did play an important role in moderating associations between prosocial behaviors and self-perceptions of status (see below).

Despite bivariate correlations between self-perceptions of dominance and relational aggression, public prosociality, and altruistic prosociality, these associations were non-significant over time. Further, in both correlations and the longitudinal models, prestige was largely unrelated to aggression and prosociality (apart from one marginal trend in which T1 prestige predicted lower T2 relational aggression). However self-perceptions of dominance seem to be meaningful for relational aggression and prosocial behavior for people with some degree of felt insecurity about their status. These associations indicated effects that were consistently strongest for those average and especially high in social status insecurity: dominance predicted higher concurrent relational aggression and public prosociality, and lower altruistic behaviors increasingly so as participants reported greater insecurity in their status. Thus, feeling as though one holds dominance (characterized by coercive use of force and intimidation; Cheng et al., 2010) over others may lead to increasingly strategic use of both relationally aggressive behaviors and proactive prosocial acts, and an increasingly weaker inclination for altruistic or other-oriented acts, only if one feels as though there is a threat to lose their dominance. However, unexpectedly, social status insecurity did not moderate the link between dominance and later (T2) relational aggression. We are unsure if this is a power issue given the lower sample size at T2, or more reflective of insecurity playing a larger role immediately vs. over time.

The findings that prestige was unrelated to aggression and prosociality, and these associations did not differ based on social status insecurity (with the exception of one association with relational aggression, which was then non-significant in follow-up tests), were somewhat surprising. However, some of the differences between our present line of thinking may be because of distinctions in this view of status vs. those typically examined in the adolescent literature. That is, while dominance and prestige are well-validated in terms of capturing two distinct forms of status and strategies to navigate social hierarchies (Maner and Case, 2016; Cheng et al., 2010), they are conceptually not entirely overlapped with popularity and preference as forms of status among peers. Both prestige and preference align with the communal dimension of interpersonal tendencies, whereas both dominance and popularity align with the agentic dimension of interpersonal tendencies (Locke, 2015). However, popularity may itself be attained via either dominance or prestige strategies—for instance, Resource Control Theory posits that both prosocial (e.g., flattery, ingratiation) and coercive (e.g., forceful) strategies can facilitate high status, especially if these are effectively balanced (Hawley, 2003). Here, we approached self-perceptions of status from a view of general dominance/prestige because of its strong background in explaining adults' status cognition and behaviors and its well-validated self-report assessment (Cheng et al., 2010) relative to the scarcity of valid self-reports of self-perceptions of popularity and preference. However, it would be useful to examine self-perceptions of popularity and preference, and/or dominance and prestige among peers more specifically given their proximity to the current constructs of interest.

Contributions, limitations, and future directions

This study contributes to future research in a few ways. First, it suggests that examining social motivations for status-oriented behaviors is meaningful in emerging adults, a population where this research has previously not focused. More detailed examinations informed by these results would be helpful. For instance, recent work in adolescents suggests that avoiding low popularity may drive aggression more so than striving for high popularity (Lansu and van den Berg, 2024), which may also be true of young adults (while recognizing that popularity is somewhat distinct at this age; Lansu et al., 2023). Second, this research extends the literature on forms of prosocial behaviors (Carlo and Randall, 2002) by examining these in the context of peer social status dynamics. As with previous studies, the altruistic and public forms of prosocial behaviors are generally inversely related to status-relevant goals and behaviors. Third, while the design of the study allowed us to capture constructs only across 8 months, it still offers a view of the developmental nature of emerging adulthood relational aggression and prosocial behaviors. This longitudinal data is valuable in overcoming issues inherent to cross-sectional findings (though most findings replicated in both the cross-sectional and longitudinal models). However, future longer term longitudinal studies could flush out these mechanisms in more detail.

This study was not without limitations. First, all variables were self-reported and subject to social desirability and other biases. While social goals and status insecurity are best self-reported, replications of findings using peer or other assessments of social behaviors and actual peer status is an important next step. As described earlier, self-perceptions of status are distinct from a more generalized consensus among peers or familiar others. Second, attrition from the first to second timepoint was higher than desired. Prolific is a valuable recruitment tool for research—however, it does not able us to speak to why some participants opted to not continue their participation to the second time point. Some may have simply no longer been active on the platform and thus did not see the follow-up recruitment call to participate, while disinterest in the study given the content could have also been a factor for some. Yet, there were no mean-level differences in the Time 1 variables for those who persisted vs. did not, which suggests there may not have been meaningful selection effects that would affect results. However, relational aggression did decrease over time, which can either reflect changes in willingness to report undesirable behaviors, or perhaps greater maturity over the 8-month period that led to a reduction in these acts.

This study was also limited in that it did not capture a number of other factors that may affect findings. For instance, individual difference variables like personality, social cognition (e.g., biases), or emotional reactivity may interplay with goals and status insecurity in explaining aggression and prosociality. Nonetheless, we expect that the current findings contribute to existing research and can inform efforts to address these limitations.

Conclusion

Better understanding relational aggression in emerging adults is important, as victimization by such behaviors has negative impacts on adjustment and wellbeing and is perceived as common among those at this developmental stage. To the extent that relational aggression serves as function of status, as our results and others suggest, it is also important to understand other behaviors to paint the clearest picture of strategic efforts toward popularity and preference. This study suggested that beyond relational aggression, proactive (public) forms of prosociality are also tied to striving for popularity, while more altruistic or other-oriented forms of prosociality are more linked to desires for social preference. Social preference goals also predicted decreases in use of relational aggression, and thus may serve an interpersonally protective function. Tests of indirect effects suggest that popularity goals are linked to higher status via relational aggression and use of prosocial behaviors, while the moderation results suggest that self-perceptions of dominance are only linked to aggression and prosociality for those with some degree of insecurity in their felt status. In terms of practical application of results, findings suggest that targeting social motivations (for instance, by attempting to promote more prosocial forms of status-seeking) could be an avenue of reducing relational aggression. Collectively, the results inform efforts to better understand peer relationships of emerging adulthood, as a unique developmental period.

Data availability statement

The dataset for this study can be found in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/udf86/).

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by Roanoke College Institutional Review Board. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Participants provided their consent electronically.

Author contributions

DF-V: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BC: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for this study was provided by an internal grant awarded to the DF-V.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abele, A. E., and Wojciszke, B. (2014). “Communal and agentic content in social cognition: a dual perspective model,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 50 (New York, NY: Academic Press), 195–255. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800284-1.00004-7

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. London: Sage Publications, Inc.

Arnett, J. (2014). Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199929382.001.0001

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskiene, R., and Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 1, 569–576. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7

Bailey, C. A., and Ostrov, J. M. (2008). Differentiating forms and functions of aggression in emerging adults: associations with hostile attribution biases and normative beliefs. J. Youth Adolesc. 37, 713–722. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9211-5

Baumeister, R. F., Bushman, B. J., and Campbell, W. K. (2000). Self-esteem, narcissism, and aggression: does violence result from low self-esteem or from threatened egotism? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 9, 26–29. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00053

Boxer, P., Tisak, M. S., and Goldstein, S. E. (2004). Is it bad to be good? An exploration of aggressive and prosocial behavior subtypes in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 33, 91–100. doi: 10.1023/B:JOYO.0000013421.02015.ef

Brodie, Z. P., Goodall, K., Darling, S., and McVittie, C. (2019). Attachment insecurity and dispositional aggression: the mediating role of maladaptive anger regulation. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 36, 1831–1852. doi: 10.1177/0265407518772937

Bushman, B. J., and Anderson, C. A. (2001). Is it time to pull the plug on hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychol. Rev. 108, 273–279. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.108.1.273

Card, N. A., and Little, T. D. (2006). Proactive and reactive aggression in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis of differential relations with psychosocial adjustment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 30, 466–480. doi: 10.1177/0165025406071904

Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Sawalani, G. M., and Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Dev. 79, 1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x

Carlo, G., Hausmann, A., Christiansen, S., and Randall, B. A. (2003). Sociocognitive and behavioral correlates of a measure of prosocial tendencies for adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 23, 107–134. doi: 10.1177/0272431602239132

Carlo, G., and Padilla-Walker, L. (2020). Adolescents' prosocial behaviors through a multidimensional and multicultural lens. Child Dev. Perspect. 14, 265–272. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12391

Carlo, G., and Randall, B. A. (2002). The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 31, 31–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1014033032440

Casper, D. M., Card, N. A., and Barlow, C. (2020). Relational aggression and victimization during adolescence is a meta-analytic review of unique associations with popularity, peer acceptance, rejection, and friendship characteristics. J. Adolesc. 80, 41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.12.012

Chávez, D. V., Salmivalli, C., Garandeau, C. F., et al. (2022). Bidirectional associations of prosocial behavior with peer acceptance and rejection in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 51, 2355–2367. doi: 10.1007/s10964-022-01675-5

Chen, P., Coccaro, E. F., and Jacobson, K. C. (2012). Hostile attributional bias, negative emotional responding, and aggression in adults: moderating effects of gender and impulsivity. Aggress. Behav. 38, 47–63. doi: 10.1002/ab.21407

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., and Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104, 103–125. doi: 10.1037/a0030398

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., and Henrich, J. (2010). Pride, personality, and the evolutionary foundations of human social status. Evol. Hum. Behav. 31, 334–347. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.02.004

Cillessen, A. H., Mayeux, L., Ha, T., de Bruyn, E. H., and LaFontana, K. M. (2014). Aggressive effects of prioritizing popularity in early adolescence. Aggress. Behav. 40, 204–213. doi: 10.1002/ab.21518

Cillessen, A. H. N., and Mayeux, L. (2004). From censure to reinforcement: developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Dev. 75, 147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x

Cillessen, A. H. N., and Rose, A. J. (2005). Understanding popularity in the peer system. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 14, 102–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00343.x

Crick, N. R. (1996). The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children's future social adjustment. Child Dev. 67, 2317–2327. doi: 10.2307/1131625

Crick, N. R., and Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychol. Bull. 115, 74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74

Crick, N. R., and Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 66, 710–722. doi: 10.2307/1131945

Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., Burr, J. E., Cullerton-Sen, C., Jansen-Yeh, E., Ralston, P., et al. (2006). A longitudinal study of relational and physical aggression in preschool. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 27, 254–268. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.02.006

Dahlen, E. R., Czar, K. A., Prather, E. E., and Dyess, C. (2013). Relational aggression and victimization in college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 54, 140–154. doi: 10.1353/csd.2013.0021

Dawes, M., and Xie, H. (2014). The role of popularity goal in early adolescents' behaviors and popularity status. Dev. Psychol. 50:489. doi: 10.1037/a0032999

Dumas, T. M., Davis, J. P., and Ellis, W. E. (2019). Is it good to be bad? A longitudinal analysis of adolescent popularity motivations as a predictor of engagement in relational aggression and risk behaviors. Youth Soc. 51, 659–679. doi: 10.1177/0044118X17700319

Eisenberg, N., and Fabes, R. A. (1998). “Prosocial development,” in Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 3: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development, 5th Edn., eds. N. Eisenberg, and W. Damon (New York, NY: Wiley), 701–778.

Ethridge, P., Sandre, A., Dirks, M. A., and Weinberg, A. (2018). Past-year relational victimization is associated with a blunted neural response to rewards in emerging adults. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 13, 1259–1267. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsy091

Findley, D., and Ojanen, T. (2013). Agentic and communal goals in early adulthood: associations with narcissism, empathy, and perceptions of self and others. Self Identity 12, 504–526. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2012.694660

Findley-Van Nostrand, D., and Ojanen, T. (2018). Forms of prosocial behaviors are differentially linked to social goals and peer status in adolescents. J. Genet. Psychol. 179, 329–342. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2018.1518894

Goldstein, S. E., Chesir-Teran, D., and McFaul, A. (2008). Profiles and correlates of relational aggression in young sdults' romantic relationships. J Youth Adolescence 37, 251–265. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9255-6

Gros, D. F., Stauffacher Gros, K., and Simms, L. J. (2010). Relations between anxiety symptoms and relational aggression and victimization in emerging adults. Cognit. Ther. Res. 34, 134–143. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9236-z

Hawley, P. H. (2003). Prosocial and coercive configurations of resource control in early adolescence: a case for the well-adapted Machiavellian. Merrill Palmer Q. 49, 279–309. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2003.0013

Hawley, P. H. (2014). The duality of human nature: coercion and prosociality in youths' hierarchy ascension and social success. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 433–438. doi: 10.1177/0963721414548417

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hensums, M., Brummelman, E., Larsen, H., van den Bos, W., and Overbeek, G. (2023). Social goals and gains of adolescent bullying and aggression: a meta-analysis. Dev. Rev. 68:101073. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2023.101073

Holterman, L. A., Murray-Close, D. K., and Breslend, N. L. (2016). Relational victimization and depressive symptoms: the role of autonomic nervous system reactivity in emerging adults. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 110, 119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.11.003

LaFontana, K. M., and Cillessen, A. H. N. (2010). Developmental changes in the priority of perceived status in childhood and adolescence. Soc. Dev. 19, 130–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00522.x

Lansu, T. A. M., and Cillessen, A. H. N. (2012). Peer status in emerging adulthood: associations of popularity and preference with social roles and behavior. J. Adolesc. Res. 27, 132–150. doi: 10.1177/0743558411402341

Lansu, T. A. M., Findley-Van Nostrand, D., and Cillessen, A. H. N. (2023). Popularity according to emerging adults: what is it, and how to acquire it. Emerg. Adulthood 11, 331–345. doi: 10.1177/21676968211066668

Lansu, T. A. M., and van den Berg, Y. H. M. (2024). Being on top versus not dangling at the bottom: Popularity motivation and aggression in youth. Aggress. Behav. 50:e22163. doi: 10.1002/ab.22163

Li, Y., Wang, M., Wang, C., and Shi, J. (2010). Individualism, collectivism, and Chinese adolescents' aggression: intracultural variations. Aggress. Behav. 36, 187–194. doi: 10.1002/ab.20341

Li, Y., and Wright, M. F. (2013). Adolescents' social status goals: relationships to social status insecurity, aggression, and prosocial behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 43, 146–160. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9939-z

Locke, K. D. (2015). Agentic and communal social motives. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 9, 525–538. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12201

Long, Y., and Li, Y. (2020). The longitudinal association between social status insecurity and relational aggression: moderation effects of social cognition about relational aggression. Aggress. Behav. 46, 84–96. doi: 10.1002/ab.21872

Lu, T., Li, L., Niu, L., Jin, S., and French, D. C. (2018). Relations between popularity and prosocial behavior in middle school and high school Chinese adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 42, 175–181. doi: 10.1177/0165025416687411

Malamut, S. T., van den Berg, Y. H. M., Lansu, T. A. M., and Cillessen, A. H. N. (2021). Bidirectional associations between popularity, popularity goal, and aggression, alcohol use and prosocial behaviors in adolescence: a 3-year prospective longitudinal study. J. Youth Adolesc. 50, 298–313. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01308-9

Maner, J. K., and Case, C. R. (2016). “Dominance and prestige: dual strategies for navigating social hierarchies,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 54 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 129–180. doi: 10.1016/bs.aesp.2016.02.001

Mestre, M. V., Carlo, G., Samper, P., Malonda, E., and Mestre, A. L. (2019). Bidirectional relations among empathy-related traits, prosocial moral reasoning, and prosocial behaviors. Soci. Dev. 28, 514–528. doi: 10.1111/sode.12366

Murray-Close, D., Ostrov, J. M., Nelson, D. A., Crick, N. R., and Coccaro, E. F. (2010). Proactive, reactive, and romantic relational aggression in adulthood: measurement, predictive validity, gender differences, and association with intermittent explosive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 44, 393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.09.005

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B.O. (1998-2017). Mplus User's Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Nelson, D. A., Springer, M. M., Nelson, L. J., and Bean, N. H. (2008). Normative beliefs regarding aggression in emerging adulthood. Soc. Dev. 17, 638–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00442.x

Ojanen, T., and Findley-Van Nostrand, D. (2014). Social goals, aggression, peer preference, and popularity: longitudinal links during middle school. Dev. Psychol. 50, 2134–2143. doi: 10.1037/a0037137

Ojanen, T., Findley-Van Nostrand, D., and McVean, M. L. (2024). Is bullying always about status? Status goals, forms of bullying, popularity and peer rejection during adolescence. J. Genet. Psychol. 185, 36–49. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2023.2254347

Ojanen, T., Grönroos, M., and Salmivalli, C. (2005). An interpersonal circumplex model of children's social goals: links with peer-reported behavior and sociometric status. Dev. Psychol. 41, 699–710. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.699

O'Mealey, M., and Mayeux, L. (2022). Similarities and differences in popular peers in adolescence and emerging adulthood. J. Genet. Psychol. 183, 152–168. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2021.2019666

Ostrov, J. M., and Houston, R. J. (2008). The utility of forms and functions of aggression in emerging adulthood: association with personality disorder symptomatology. J. Youth Adolesc. 37, 1147–1158. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9289-4

Raine, A., Dodge, K., Loeber, R., Gatzke-Kopp, L., Lynam, D., Reynolds, C., et al. (2006). The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggress. Behav. 32, 159–171. doi: 10.1002/ab.20115

Reig-Aleixandre, N., Esparza-Reig, J., Martí-Vilar, M., Merino-Soto, C., and Livia, J. (2023). Measurement of prosocial tendencies: meta-analysis of the generalization of the reliability of the instrument. Healthcare 11:560. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11040560

Reijntjes, A., Vermande, M., Olthof, T., Goossens, F. A., Vink, G., Aleva, L., et al. (2018). Differences between resource control types revisited: a short term longitudinal study. Soc. Dev. 27, 187–200. doi: 10.1111/sode.12257

Ruschoff, B., Dijkstra, J. K., Veenstra, R., and Lindenberg, S. (2015). Peer status beyond adolescence: types and behavioral associations. J. Adolesc. 45, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.013

Salmivalli, C., Ojanen, T., Haanpää, J., and Peets, K. (2005). “I'm OK but you're not” and other peer-relational schemas: explaining individual differences in children's social goals. Dev. Psychol. 41, 363–375. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.363

Samson, J. E., Ojanen, T., and Hollo, A. (2012). Social goals and youth aggression: meta-analysis of prosocial and antisocial goals. Soc. Dev. 21, 645–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00658.x

Soloman, S., and Sawilowsky, S. (2009). Impact of rank-based normalizing transformations on the accuracy of test scores. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 8, 448–462. doi: 10.22237/jmasm/1257034080

Tremblay, R. E. (2000). The development of aggressive behaviour during childhood: what have we learned in the past century? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 24, 129–141. doi: 10.1080/016502500383232

van den Berg, Y. H., Lansu, T. A., and Cillessen, A. H. (2020). Preference and popularity as distinct forms of status: a meta-analytic review of 20 years of research. J. Adolesc. 84, 78–95. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.07.010

Volk, A. A., Dane, A. V., Marini, Z. A., and Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Adolescent bullying, dating, and mating: testing an evolutionary hypothesis. Evol. Psychol. 13:1474704915613909. doi: 10.1177/1474704915613909

Voulgaridou, I., and Kokkinos, C. M. (2023). Relational aggression in adolescents across different cultural contexts: a systematic review of the literature. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 8, 457–480. doi: 10.1007/s40894-023-00207-x

Werner, N. E., and Crick, N. R. (1999). Relational aggression and social-psychological adjustment in a college sample. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 108, 615–623. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.4.615

Wright, M. F., Li, Y., and Shi, J. (2012). Chinese adolescents' social status goals: Associations with behaviors and attributions for relational aggression. Youth Soc. 46, 1–23. doi: 10.1177/0044118X12448800

Keywords: relational aggression, prosocial behaviors, social goals, popularity, emerging adulthood

Citation: Findley-Van Nostrand D and Campbell B (2024) Goals for, insecurity in, and self-perceptions of peer status: short term longitudinal associations with relational aggression and prosocial behaviors in emerging adults. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2:1433449. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2024.1433449

Received: 15 May 2024; Accepted: 18 November 2024;

Published: 18 December 2024.

Edited by:

Christian Berger, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, ChileReviewed by:

Zheng Huang, Nanjing Vocational University of Industry Technology, ChinaEduardo Franco, Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, Peru

Copyright © 2024 Findley-Van Nostrand and Campbell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Danielle Findley-Van Nostrand, ZmluZGxleUByb2Fub2tlLmVkdQ==

†Present address: Benjamin Campbell, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

Danielle Findley-Van Nostrand

Danielle Findley-Van Nostrand Benjamin Campbell

Benjamin Campbell