- Department of Educational Psychology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

Introduction: In this paper we propose that one of the core developmental aims of adolescence is to cultivate a capacity for active balancing as the primary process for creating a coherent, agentic self capable of contributing to the functioning and purposes of the communities which adolescents inhabit, including society as a broader community. While there many valuable initiatives and programs to promote positive development, learning, and wellbeing, these efforts typically take a siloed approach focusing on one dimension of development (e.g., social-emotional learning), leaving adolescents to create coherence from these disconnected approaches. As adolescence face an increasingly uncertain future (e.g., career instability), serious threats to human survival (e.g., environmental degradation), social divides (e.g., political and ideological polarization), etc., a siloed approach to adolescent development is not simply outmoded but it reinforces a fragmented self.

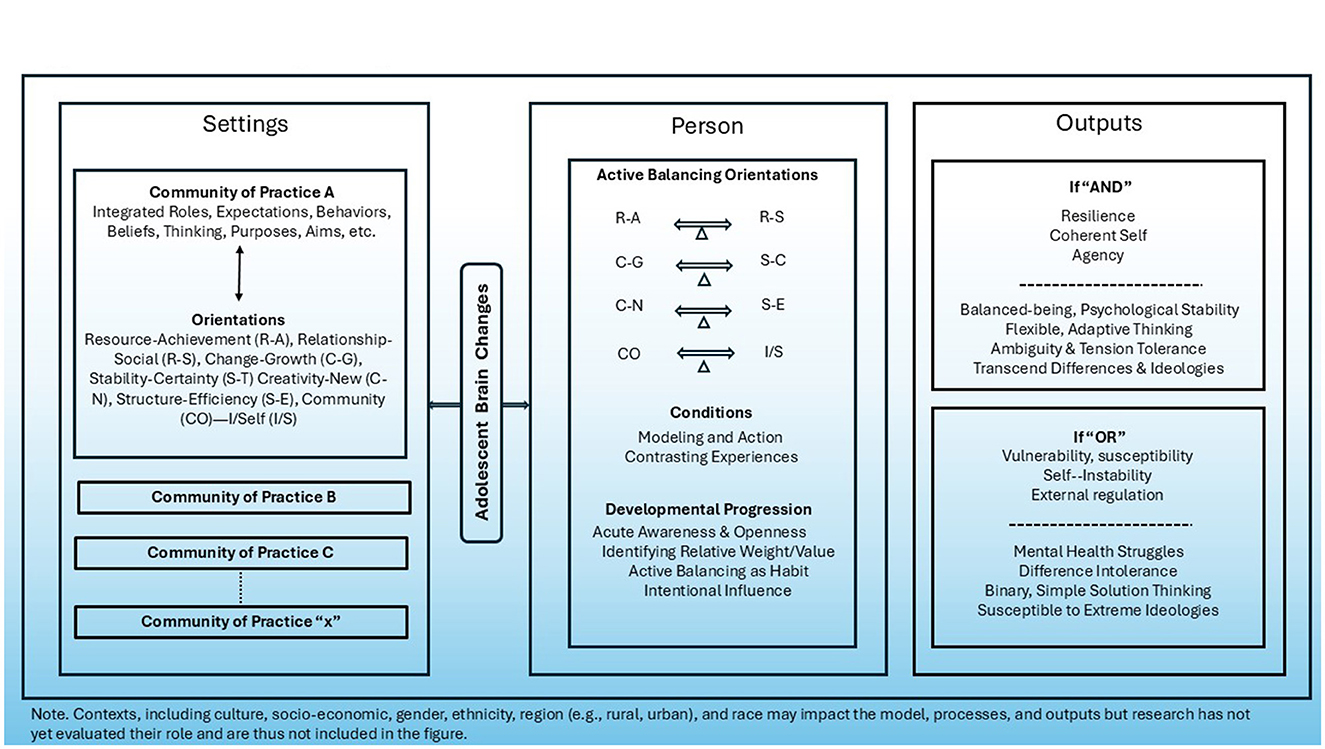

Conceptual model and background: In this paper we argue that a siloed approach to adolescent development and learning may contribute to a fragmented sense of self and agency, which can be associated with increased vulnerability to mental health challenges. We first link the proposed developmental aim of adolescence to neuroscience findings that identify three brain changes during adolescence that lay the groundwork for cultivating active balancing and provide an ontogenetic neurological push for adolescents to learn and manage how to engage their worlds. Leveraging this ontogenetic push, we propose adolescents can cultivate their capacity for active balancing within the cultural communities of practice they inhabit. These communities provide a ready and powerful fusion of action, affect, and thought into coherent and relevant understandings of the why, how, and utility of practices in a community, or what we label orientations. Active balancing is the process of actively seeking to establish or reestablish one's intended balance among these orientations.

Conclusions and implications: Building the capacity for active balancing, we suggest, engenders greater resilience and adaptability to a range of situations, a tolerance for and ability to resolve tensions, and an ability to transcend vast differences, including cultural and ideological. Implications for both the adolescent and society are discussed.

Introduction

Forging a meaningful, coherent self as an interconnected agent-in-society who can contribute to the functioning and purposes of the communities one inhabits (e.g., exercise agency) is a quintessential task of human adolescence (Berzonsky, 2011; Branje et al., 2021; Brockmeier, 2009; Erikson, 1994; Hill et al., 2013; Romer and Hansen, 2021). However, despite numerous programs, initiatives, and reforms designed to support adolescents in this task (e.g., social-emotional curricula), we see signs of a breakdown in their agency (e.g., apathy) and their purposeful functioning marked by increased vulnerability to mental health problems (e.g., depression, anxiety), problems further aggravated by a pandemic (Duffy et al., 2019; Luthar et al., 2020; Mojtabai and Olfson, 2020). During this developmental period, adolescents face multiple challenges from building self-esteem, managing family expectations, and participating and exceling in different programs (after-school programs, extracurricular activities, hobby clubs etc.) through the initiatives offered by various organizations. These initiatives, each focused on important aspects, tend to approach development in a siloed manner (e.g., socio-emotional foci), leaving adolescents to forge a coherent self from these fragmented efforts. Missing is an approach to adolescent development that can situate these siloed approaches within a conceptual model rooted in what we see as the distinct developmental aim of adolescence.

We propose that one of the distinct developmental aims of adolescence (puberty to roughly age 18) is cultivating a capacity for active balancing as the dominant approach for creating a coherent self as an agent-in-society. That is, adolescence is about the need to cultivate the ability of active balancing within a cultural community of practice. Cultural communities of practice are defined as communities of practice that have distinct amalgamations and weightings (valuing) of integrated attitudes, beliefs, thoughts, etc. that guide a community's action (Brockmeier, 2009), which we refer to as orientations. Hence, active balancing is the process of cultivating balance among these orientations within and across the cultural communities of practice of one's life. For example, an inclination to favor stability and certainty, as an orientation, might be valued more than fostering an inclination toward change and growth within a cultural community of practice. One developmental aim of adolescence, therefore, is to learn how to actively balance both the stability as well as the change while being present within the cultural community of practice.

To argue that active balancing is a developmental aim, we first present evidence from the field of neuroscience that highlights three changes during adolescence that lay the groundwork for cultivating active balancing. Next, we situate the growth and development of active balancing within these cultural communities of practice, arguing that active balancing requires an “AND” rather than an “OR” approach to orientations. We argue that cultivation of active balancing could support adolescents in fostering resilience and adaptability, potentially enhancing their ability to tolerate and resolve tensions, as well as navigate cultural and ideological differences and, therefore, support participating in society while progressing toward a coherent self. We then discuss different supports that cultivate active balancing and conclude with discussion of the implications of active balancing for adolescents, research, and society.

Adolescent brain development supporting active balancing

Research on brain development during adolescence suggests that the neurological groundwork for active balancing emerges and becomes consolidated during adolescence (Marek et al., 2015; Váša et al., 2020). There are three major interconnected changes that allow for a profound shift in brain function, where the integration of affective and cognitive networks, guided by salience, underpins a dynamic capacity for more sophisticated and reflective understandings and interactions with the world. These interconnected changes, described next, provide the neurological structure for cultivating active balancing but the changes alone do not ensure it. Rather cultivating active balancing requires experiences within the cultural communities of practice in adolescents' daily lives to leverage the neurological potential.

One change that supports active balancing is the functional integration of existing major brain networks during adolescence. Research indicates that there is a major cross-network coupling (e.g., new neural pathways) that allows for the integration (e.g., unifying) of social, motivational, emotional, and cognitive large-scale networks and their concomitant operations into a functional unit (Kilford et al., 2016; Luna et al., 2015; Marek et al., 2015). In particular, the default network, involved in self-referential and interpersonal functions (e.g., inferring others mental states) among other functions, and the central executive network, involved in cognitive functions (e.g., decision-making, inhibition, planning), becomes functionally integrated. Supporting this integration, adolescents experience a period of heightened affective awareness, or hyper-responsiveness/sensitivity, in which the intensity of motivation, emotion, and reward is magnified. This heightened awareness is most acute in early adolescence, with a decline in mid-to-late adolescence (Galván, 2010). While the ontogenetic purpose of this heightened awareness is not fully understood, it certainly raises the valuation of social and cognitive processes (Kilford et al., 2016). Although there are important within network changes during adolescence, these changes are akin to fine tuning of the networks rather than any major restructuring of a given network; major changes within these distinct networks appear to slow down and stabilize prior to adolescence (Marek et al., 2015). To clarify, this does not mean that within network changes in neural pathways (e.g., myelination) during adolescence stops or are unimportant. Instead, it indicates that a major ontogenetic focus of adolescent brain development appears to be between network integration rather than within network growth or expansion (Stevens et al., 2009).

There are several implications of this cross-network integration. First, integration is considered vital for the maturation of adult-level capacities, such as inhibitory control (Labouvie-Vief et al., 2010; Menon, 2013) and the ability to “flexibly, voluntarily, and adaptively coordinate” goal-directed behavior (Luna et al., 2015). Practically, this integration can be seen in adolescents' burgeoning skills requiring coordination across large scale networks, such as the development of strategic thinking skills to influence human systems (Larson and Angus, 2011; Larson and Hansen, 2005). Second, we suggest that the ontogenetic push to integrate networks into a functional unit appears to induce a drive for adolescents to integrate, organize, and understand their experiences as part of a cohesive whole. For example, identity development (e.g., self) is considered a major task of adolescence, which requires the integration of social, cognitive, and affective information and processes (Pfeifer et al., 2013; Pfeifer and Berkman, 2018). The integration of networks into a cohesive unit during adolescence, then, represents not only a fundamental shift in individuals' capacities but also a shift in how adolescents engage the settings of their lives from a new functional purview that prioritizes coherence across experiences (Rivera et al., 2013).

A second change that supports active balancing is a shift toward reliance on salience to interpret and prioritize experience, which results from the functional segregation (i.e., development) of the salience network during adolescence (Fair et al., 2007; Schimmelpfennig et al., 2023). As the name implies, the salience network's function is to detect and assign salience, value, or relevance to internal and external information and operations (Uddin et al., 2019). Research indicates the salience network becomes a primary regulatory hub for the coordination and initiation of interconnected networks to guide present and future behavior (Menon, 2013; Seeley, 2019; Snyder et al., 2021). The role of the salience network means that the functional integration of networks described in the previous paragraphs is not the result of a haphazard or predetermined process but is guided by salience due to the emergence of the salience network during adolescence. Assigning salience to internal and external information is neither haphazard or predetermined but likely the result of the past and present experiences within and across settings. Salience, then, is a powerful organizing mechanism for creating coherence across networks and experiences (Rakesh et al., 2023).

The impact of the emergence of salience network during adolescence is likely evident across several established research domains, such as meaning, intentionality, purpose, and identity. Frankl's (1946) seminal work on individual's perpetual search to make meaning, even under conditions of extreme duress and affliction, was considered the foundation for wellbeing and growth throughout life. Baumeister and Hippel (2020) argue that evolution pushed the emergence of brain structure that positioned the use of meaning to organize, interpret, and guide interactions with one's environment, thereby enhancing survival and adaptation. Meaning making, or meaning construction, is also central to Kegan's (1982) developmental constructivist theory and is thought to propel learning through engaging contradictions and paradoxes that propel learning. Finally, within many identity theories, salience or meaning is embedded in attempts to understand the self both as its own entity and as an entity in relation to others, institutions, society, etc. (Erikson, 1994; Hill et al., 2013). Thus, beginning in adolescence salience appears to become a primary process that guides the integration of experience into a coherent whole, including a coherent self (Davidow et al., 2018). Practically, we suspect the primacy of salience during adolescence coincides with adolescent's questioning and evaluation of the importance everyday experiences, including the relevance of specific educational experiences.

A third change supporting active balancing is a deepening capacity for deliberative awareness during adolescence. In addition to neuroscience, there are numerous other fields that focus on different aspects of deliberative awareness, so many that we cannot cover each of their linkages to active balancing. We chose instead to highlight research most relevant to active balancing. Neuroscience indicates that during adolescence there is growth in executive functioning, including an increased capacity for abstract, complex, and flexible thinking, greater perspective taking and social awareness, and increased capacities for planning (e.g., future planning) and focused attention (Best and Miller, 2010; Blakemore, 2012; Dumontheil et al., 2010; Luna et al., 2004). From the field of cognition, it is well documented that adolescents develop greater capacities for metacognition (e.g., awareness of and reflecting on one's thought processes) and multidimensional thinking (Keating, 2004). In the field of expertise development, deliberate practice, which presumes conscious awareness or introspection, is a key component that appears to differentiate greater/lesser expertise development (Ericsson et al., 1993), which can develop during adolescence. In the rapidly expanding field of mindfulness, awareness of or paying attention on purpose in the present to one's thought processes is integral to the practice of mindful living and has been linked to wellness (Carson and Langer, 2006; Kabat-Zinn and Hanh, 2009). Adolescents' expanding capacity for deliberative awareness, then, promotes sophisticated, flexible, and adaptive thinking that might otherwise become get trapped by rigid, absolutist, and binary thinking tendencies without substantial brain development (e.g., Carson and Langer, 2006). Deliberative awareness, in our view, enables intentionality and forethought in the process of assigning salience so that salience is not beholden to past values or momentary, situational salience.

Overall, these three neurological changes combined suggest a distinct ontogenetic push to maximize adolescents' emerging capacities for perceiving and engaging their environments, relationships, society, and the world as a coherent whole. As a result, salience becomes the dominant process guiding the integration of affective and cognitive systems for a more sophisticated and coherent approach for engaging the settings of one's life (Rakesh et al., 2023). This ontogenetic push may offer opportunities for adolescents to explore new ways of engaging with their environments, using their emerging capacities, but the actual learning and its efficacy will depend on experience within settings, or more specifically, experience as a member of a cultural community of practice (Handley et al., 2006).

From brain development to orientations

The active balancing framework builds on self-regulated learning (SRL) and theory self-determination theory (SDT) but also differs from these theories in important way. Self-regulated learning (SRL) theory stresses the importance of integrating affective, cognitive, and behavioral components of learning to achieve a desired outcome (Pintrich, 1999). SDT similarly focuses on a striving toward motivational integration or ownership of extant values, commitments, beliefs, personal interests, and behaviors in pursuit of a goal or outcome (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Both SRL and SDT position integration in relation to the ‘self' (e.g., integrating motivation so it is congruent with one's sense of self; Vansteenkiste et al., 2018). As we outline next, the active balancing framework also focuses on integration of affect, cognition, and behavior into a functional unit based on attitudes, beliefs, thoughts, behaviors, etc., within cultural communities of practice as well as individual's cumulative experience. While the focus of SRL and SDT is on learning related to achieving an outcome or goal in a given setting (e.g., school), active balancing focuses on the dynamic process of balancing the relative prominence of orientations for engaging in one's communities of practice. Active balancing, then, is about building and sustaining one's active balancing capacity rather than achieving a goal or outcome. Stated more succinctly, the overarching aim is to employ active balancing as a lens for engaging in one's environment, taking necessary steps to adjust the perceived imbalance. When this occurs, we suggest an adolescent build their agency and a coherent sense of self who can effectively participate in the many settings of their daily lives.

The cultural communities of practice in which adolescents participate provide opportunities for them to build coherence, leveraging newfound capacities in the process. A cultural community of practice refers to “people's participation in cultural practices,” “emphasizing the active and interrelated roles of both individuals and cultural communities” (Rogoff, 2016, p. 16). A cultural community of practice provides a ready and powerful fusion of action, affect, and thought into coherent and relevant understandings of the why, how, and utility of practices in a community (Bruner, 1990, 2009; Rogoff, 2003, 2016)—we refer to these as a community's orientations. Orientations function as dispositional inclinations serving as motivational and organizational guides for understanding experience and for engaging in the behaviors and practices of a cultural community. Orientations are not static, but morph over time and can become obsolete or irrelevant. Additionally, some orientations may be more prevalent in some communities than in others, or an orientation may be relatively non-existent in one community but prominent in another.

Communities' orientations provide the raw material from which adolescents can begin to cultivate active balancing. Adolescents intuit the relative value of different orientations from their experiences in a community, and from these experiences, they assemble a distinct weighting of orientations to guide their perception and action, not just within a specific community, but also in their lives. Active balancing, then, is the process of balancing these orientations.

Common orientations

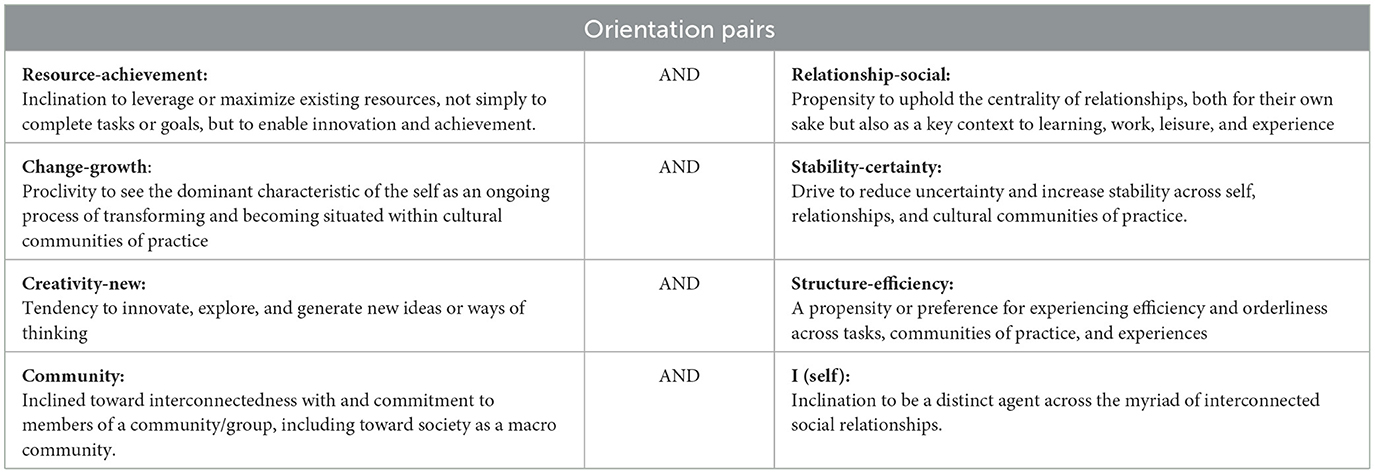

There are four sets of orientations common across cultural communities that provide opportunities for adolescents to cultivate active balancing. Within each set, two orientations tend to create natural tension points (e.g., compete for prominence) for adolescents to examine and seek to establish or reestablish balance, e.g., the relative value placed on each orientation. Table 1 provides a description of each orientation within its set.

Resource-achievement and relationship-social orientations

The first set of orientations is resource-achievement and relationship-social orientations. Our conceptualization of the resource-achievement orientation draws from two literatures. First, research from the field of business suggests that adequacy of resources (e.g., from low to high resource), including employee's perception of resource adequacy, is associated with innovation and performance (Amabile, 1996; Weiss et al., 2017). Too few actual resources, with employee's perception that these resources are inadequate, has been associated with low innovation performance (e.g., problem solving), but a wealth of resources has also been associated with low innovation as resources go underutilized or ignored (Weiss et al., 2013). A relative balance between too few and an excess of resources appears better suited to innovation and job performance, although what is considered adequate can vary considerably. Second, there is a vast research literature on achievement motivation theory, with its many offshoots (e.g., achievement goal theory), suggesting that individuals' orientation toward performance goals, such as performance- and mastery-goals, influences their behavior and motivation to engage in learning (see Urdan and Kaplan, 2020 for review of theory), including engaging the available resources. While performance- and mastery-goals are often pitted against each other, their relation to an outcome (e.g., achievement) appears to depend on the conditions under which a goal is sought, for example, performance-goals predict achievement when performance is the dominant condition (Senko, 2019). Thus, balancing performance- and mastery-goals per conditions appears most effective. From these two research lines, we define a resource-achievement orientation, as an inclination to leverage or maximize existing resources, not simply to complete tasks or goals, but to enable innovation and achievement.

Our conceptualization of a relationship-social orientation is rooted in relational-cultural theory (RCT). The core of RCT is that human development occurs through and toward relationships (Miller, 1976). RCT emphasizes “growth fostering” relationships that are characterized by growing toward mutuality and communality (vs. individualization and separation), which contribute to sustained development and flourishing (Comstock et al., 2008). Growth fostering relationships, by definition, are not static but dynamic, and are posited to promote “a sense of zest/enthusiasm, clarity about oneself, the other and the relationship, a sense of personal worth, the capacity to be creative and productive, and the desire for more connection” (Jordan, 2008, p. 2). As conceptualized here, a relationship-social orientation is a propensity to uphold the centrality of relationships, both for their own sake but also as a key context for learning or growth.

Change-growth and stability-certainty orientations

We draw on several research literatures for the conceptualization of a change-growth orientation. First, from a dialectical perspective, ongoing processes of change are endemic to persons' lived experience within the myriad of relationships in cultural communities of practice, which are also subject to ongoing change processes (Basseches, 1980, 2005; Baxter, 2004; Veraksa et al., 2022). Second, from the psychological and business literature the notion of change- or growth-oriented mindsets suggests that when individuals believe a trait (e.g., intelligence) is malleable they are more likely to persist in learning and build resilience (Dweck, 2006; Galleno and Liscano, 2013), that is, to embrace change as normative. Thus, we define a change-growth orientation as a proclivity to see the dominant characteristic of the self as an ongoing process of transforming and becoming, situated within cultural communities of practice.

Our conceptualization of a stability-certainty orientation is similar to social-identity theory and its extension to uncertainty-identity theory conceptualizations (Burke and Stryker, 2016; Hogg, 2021). An assumption of social-identity theory is that individuals are motivated to reduce uncertainty in search of predictability and stability, or at least some minimally sufficient certainty (Hogg, 2007). Reducing uncertainty occurs within various social groups to which someone belongs as individual's identify with the beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, etc. of a group (Hogg, 2021). While uncertainty-identity theory has been used to explain individual motives for identifying with groups and how this predicts radicalization, here we adopt the general principles around individuals being oriented toward stability and (sufficient) certainty. Thus, a stability-certainty orientation is defined as an inclination toward reducing uncertainty and increasing stability across self and relationships (broadly defined) within cultural communities of practice.

Creativity-new and structure-efficiency orientations

The creativity-new orientation draws on the literature on creativity. Highly creative individuals appear to be driven by a strong desire to explore and come up with new or different ideas, experiencing enjoyment in the process (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997; Ivcevic and Nusbaum, 2017; Kaufman, 2023). In Maslow's theory of self-actualization (Maslow, 1954, 1998), creativity is considered a characteristic of those who are moving toward self-actualization, which presumes basic human needs are being met. As used here, a creativity-new orientation refers to a desire to innovate, explore, and generate new ideas or ways of thinking.

Our conceptualization of the structure-efficiency orientation draws loosely from research on personality types, especially conscientiousness. Conscientiousness broadly refers to a trait of being meticulous, careful, and diligent (Goldberg, 1993). While conscientiousness is often considered an inherited trait, though some propose otherwise (Roberts et al., 2014), it tends to be associated with other socio-cultural facets, such as attention to detail, a desire for efficiency and orderliness, and sense of obligation (Hoyle, 2010). In the present context, a structure-efficiency orientation is defined as a propensity or preference for experiencing efficiency and orderliness across tasks, settings, and experiences.

Community and I (self) orientations

Theory and research from a community psychology framework informs our conceptualization of a community orientation. From this framework, a psychological sense of community is defined as a resource of feeling that one is interconnected with others and belongs to a group in which members are committed to each other and meeting needs (e.g., McMillan and Chavis, 1986). Recent conceptualizations expand this definition to incorporate a sense of responsibility and obligation to the community as well (Nowell and Boyd, 2014; Stewart and Townley, 2020). We conceptualize a community orientation as being inclined toward interconnectedness with and commitment to members of a community/group, including toward society as a macro community.

There are few topics examined in social science as much as the “I” (self) and identity, so much so that tying our conceptualization of the I (self) orientation to a tradition is not feasible or practical. Instead, we associate the I orientation more generally to key notions across many traditions. Quite clearly the idea of self is inextricably linked to the social and cultural—to layered relationships within and across settings, people, and time (McAdams and Cox, 2010). While interconnected, the I (self) is also a distinct agent that can perceive and understand this distinctness and its interdependence (Baumeister, 2011). From these notions, we conceptualize the I (self) orientation as striving to be a distinct agent across the myriads of interconnected social relationships.

Active balancing: “AND” not “OR”

We have thus far described the relative value placed on an orientation in a community of practice in “OR” terms (i.e., one orientation valued over another) to convey what may seem like two orientations vying with each other for prominence. For example, an orientation toward resource-achievement may seem to compete with an orientation toward relationship-social. We think this perceived tension between orientations is a common experience as there seems a natural proclivity to favor some orientations over others, particularly when a given orientation has had demonstrated utility in one's daily life (e.g., resulted in achieving a goal or outcome). Whereas many theories and initiatives (e.g., SEL) take a siloed understanding of orientations and human development (e.g., relational-cultural theory), the apparent competing nature of sets of orientations is a distinctive feature of the active balancing framework.

Favoring one orientation over another might contribute to an imbalanced approach to engaging communities, even if it produces desired results, potentially posing challenges to the development of a coherent self. For adolescents, the imbalance created by an OR approach is not simply at odds with their emergent capacities propelling them to create coherence across cultural communities of practice, but we suggest it can also create points of vulnerability. From this perspective, an OR approach to orientations is more likely to promote binary thinking processes to understand one's experiences, making one prone to deny or ignore the complexity of life's realities, favoring simplistic understandings and solutions (Shelton and Dodd, 2021). Similarly, an OR approach is also likely to result in a less stable self, one that is more easily disrupted and overwhelmed in the face of conflicting information, with a tendency for slight disruptions to cause breakdowns (e.g., mental health) in one's agency. Practically speaking, an OR approach may be seen in a tendency to exclude or dismiss different ideas and others (e.g., othering), employ unreflective heuristics and shallow algorithms to guide decisions and actions (e.g., Keating, 2004), and rely on external mechanisms to regulate affect, thinking, and behavior.

We propose that an “AND” approach to orientations—active balancing—is better aligned with the ontogenetic push during adolescence and the long-term cultivation of the self. As such, an AND approach allows the self to remain dynamic and adaptive across communities and time. Active balancing is the process of seeking balance between one orientation AND another. The object or target of balancing is between orientations in a set rather than on a single orientation. Active balancing requires intentionality, developing awareness of the relative weighting of orientations and how they work or do not work in tandem, and then acting to (re)calibrate balance among orientations. Developing awareness of the weighting of orientations in a set includes awareness of each orientation's weighting within a community of practice, as well as one's leanings and preferences toward each orientation.

We suggest an AND approach of actively working toward balancing orientations, including resolving inevitable tensions that arise, promotes more flexible and adaptive thinking, a greater capacity to resolve and tolerate tensions, greater psychological resilience and stability (e.g., not easily disrupted or overwhelmed), and an ability to transcend vast differences, including cultural and ideological differences. Practically, an AND approach should be seen in a tendency to value different others and ideas, the use of reflective, purposive heuristics and sophisticated cognitive algorithms, and internally, well-regulated affect, thinking, and behavior, all of which can be considered indicators of positive mental health or wellbeing (e.g., Bitsko et al., 2022).

Active balancing is not a pejorative “academic exercise” for adolescents, rather it is intimately linked to their identity and becoming an agent-in-society who can contribute to the functioning and purposes of cultural communities of practice, including society as broad community of practice. Identity and meaning have long been considered by theorists a major task of adolescence (Berzonsky, 2011; Erikson, 1994; Hill et al., 2013), as is developing personal agency (Brockmeier, 2009; Hansen et al., 2017; Romer and Hansen, 2021). Here, personal agency is the ability to intentionally influence or change the conditions of one's life, to act on one's and on other's behalf, which is mediated through the cultural communities of practice in which one participates (Brockmeier, 2009). Active balancing, we suggest, supports identity and agency by expanding opportunities and creating alternative ways for adolescents to understand their cultural communities of practice, bringing a new or heightened awareness of the intersection of orientations and communities. Further, active balancing locates meaning beyond any single existing system, which allows adolescents to forge a meaning-driven identity rather than trying to “find” or locate a pre-existing meaningful identity within existing systems (e.g., education, work). Thus, active balancing allows adolescents to forge a meaningful, coherent self as an agent-in-society within their communities of practice.

Cultivating active balancing

The foundation of the cultivating process hinges on adolescents' embracing the dynamicity of the self and the tension or discomfort caused by a present imbalance as they intentionally work toward regaining balance again. This process unfolds within the cultural communities of practice of adolescents' daily lives. Ideally, there would be at least one community that encourages the cultivating process, although we think the more communities that encourage active balancing the easier it will be for adolescents to cultivate active balancing.

Supporting active balancing

How does a cultural community of practice support adolescents' active balancing? To answer that question, we first need to set aside a desire to look for a single way or method. Cultivating active balancing rests with the person, the adolescent, so the adolescent must tailor methods that work for them. That said, a community of practice generally supports active balancing when it's members (a) model active balancing themselves, including candid communication of the tensions and imbalances among orientations they experience and how they resolve them, and (b) create conditions in which individual members can openly evaluate the community's and their own orientations absent reprisal or intrusive interjection of advice.

We inject a few cautionary words here about supporting adolescents' active balancing. Supporting adolescents' cultivation of active balancing in a community of practice is not about scheduling a dedicated time for them to reflect on their balance of orientations, what they are doing to resolve imbalances, etc. Quite the opposite! Supporting active balancing should be about a way of being within a community, in which members, and the community itself, strive toward balance of orientations, all the while engaging in its practices. The adolescent, other members of the community of practice, and the community itself are dynamically evolving. Thus, to support adolescents' active balancing, ideally the community is also working toward balance.

Contrasting experiences

While the role of contrasting experiences has been implicit to this point, here we explicitly discuss their importance for active balancing. Use of the term “developmental experiences” came to prominence through the work of Hansen et al. (2003, 2010, 2017) to represent adolescent's specific experiences (e.g., setting goals) of the opportunities afforded in organized youth programs (e.g., sport) or other settings in which they participate. Developmental experiences, it was argued, are the building blocks for a range of social and emotional skills (e.g., teamwork). While developmental experiences may contribute to adolescents' social and emotional skills, we propose this understanding of developmental experiences has limited utility in relation to cultivating a coherent self through active balancing. Instead, we propose that the nature of active balancing requires contrasting experiences.

Contrasting experiences represent a perceived discordance, juxtaposition, contradiction, or differentiation between what one expects or desires and what one experiences within one's cultural community of practice (Struyven et al., 2008). Indeed, we suggest that there can be little cultivation of the self as an agent-in-society without experiencing difference and incongruity, especially among orientations. A common source of contrasting experiences can be actual or perceived limitations on one's volition and agency, to which adolescents may be particularly attuned as they strive for adult status (Hansen and Jessop, 2017). Contrasting experiences are not automatically or necessarily negative, that is, they do not need to produce an aversive emotional reaction. Instead, contrasting experiences may engage a sophisticated alert system that something is other than desired or expected, which we suggest provides motivation to examine the source of contrast, or at least to determine whether it matters. For active balancing, contrasting experiences emerge from experience of orientations. We suggest that contrasting experiences are truly developmental because they initiate reflective processes that lead to growth (Syvertsen et al., 2024).

It is instructive, here, to consider the availability of opportunities within (and across) cultural communities of practice for contrasting experiences since they are essential for adolescent's active balancing and cultivation of the self. If a cultural community of practice is relatively isolated or insulated, or if members of a community avoid contrasting experiences, we think this could result in fewer or minimal contrasting experiences, and hence limit balancing opportunities. In the relative absence of contrasting experiences, there would be little need for active balancing since the consistency of experience in a community obviates imbalance. Under such conditions, a cultural community of practice, or members of the community, may come to experience difference or contrast as a threat to balance, or even a threat to one's way of engaging the world. Routine exposure to contrasting experiences, for the adolescent, and ideally for a community of practice, would afford opportunities to engage in active balancing and cultivate a coherent self that is an efficacious agent-in-society, including a self (and community of practice) that can thrive amid cultural, social, and global change.

Steps toward active balancing

While we next outline a possible development progression toward building active balancing, the progression represents “educated guess” since research has yet to be conducted based on the model. Thus, the lack of research using this proposed model is a limitation at this stage in understanding any development progress. The first step in cultivating active balancing is for adolescents to develop an acute awareness of orientations within the cultural communities of practice in which they participate. This step opens the door to understanding a community of practice in a new light and becoming aware of one's own orientations. This awareness provides opportunities for the adolescent to observe and accept its own orientations by acknowledging all the possible factors, demographic as well as socio-economic, that might have influenced the orientations. Without awareness of their community's orientations as well their own, an adolescent will be unable to “see” or experience the potential tensions between differential weightings of orientations and, thus, will be unable to balance orientations. However, this does not mean an adolescent may not experience tension if they do not perceive orientations as they participate in a community of practice. Rather, without an acute awareness of what is causing the tension (e.g., imbalance among orientations) their options to resolve the tension are limited. Thus, developing an acute awareness of orientations is an essential first step toward active balancing.

As awareness of orientations grows, an adolescent can engage in a second step of understanding the relative weighting or value of an orientation, again within the everyday cultural communities they inhabit. It is here that we might expect an adolescent to question the utility or value placed on an orientation, which could result in a heighted experience of tension, although this tension can now be associated with a source. We consider this experience of tension or conflict as a necessary and healthy process, and it is integral to active balancing. There is a natural desire to resolve tensions (Sinhababu, 2017) that emerge from an imbalance or mismatch in weightings of orientations in a community of practice and an adolescent's own weightings. From this tension, an adolescent can engage in seeking to establish or restore balance. At this point, the adolescent begins to make use of this information to work toward balancing orientations, that is, they begin to engage in active balancing.

Of course, beginning to engage in active balancing will not be linear or smooth as it involves establishing and then losing one's balance, only to reestablish or forge a new balance. However, with sufficient and repeated attention paid to active balancing within everyday communities of practice, adolescent's active balancing can emerge as a habituative form (Lally and Gardner, 2013). As habitus, active balancing emerges as a way of being, that is, as a normative process for cultivating and understanding the self. In principle, it is here that we should see greater psychological stability and ability to resolve and tolerate tensions. That said, active balancing will always be a dynamic habit rather than a static one.

As active balancing becomes a way of being, we envision active balancing turning from an inward facing to an outward facing stance. At this point, adolescents may develop their own descriptions and vocabulary for communicating the balance of orientations in their everyday communities of practice. Like the process of building high level expertise (e.g., concert pianist) through deliberate practice (Ericsson et al., 1993), one may devise a distinct vocabulary that synthesizes learning into integrated ideas, practical analogies, or idioms, which become communication tools for the reciprocal enrichment and enhancement of active balancing for the community of practice. At this point, the self is operating as an intentional and active agent-in-society, one who can seek to bring change in practices and processes to the relative balance of orientations within a cultural community.

Discussion

In this paper we proposed that a core aim of adolescence is to cultivate an active balancing capacity, leveraging distinct ontogenetic neurological growth during this period. Active balancing is framed as a process that, as habitus, becomes a way of being for engaging in and influencing one's cultural communities of practice. As such, this last section discusses the implications of cultivating active balancing for both the adolescent and for society more broadly, including framing wellbeing and mental health from a perspective of active balancing and movement toward balanced-being.

Balancing and agency

The notion of striving for balance in one's life to avoid negative and promote positive outcomes is a common theme in research and in popular vocabulary (e.g., Christiansen and Matuska, 2006). For example, the research on the concept of “work-life balance” suggests employees who perceive a healthy balance between work and life (e.g., family) demands/roles report greater job satisfaction and work engagement (Brough et al., 2020). A common focus in research literature is on an individual balancing the competing demands of roles (e.g., worker, parent) or time commitments across systems (e.g., job). Imbalance in these models, then, is due to an individual's inability to manage competing demands emerging from dueling systems. Such models, we suggest, effectively dismiss a system's culpability in contributing to imbalance while relegating individual's agency to a reactionary, extramural activity that is independent of the systems they inhabit. Hence, much effort is devoted to providing individuals with ways to mitigate the impact of systems on the person (e.g., self-care).

Active balancing locates processes within and across the cultural communities of practice in which adolescents participate. The focus is not on competing time or role demands across settings (Van den Broeck et al., 2017), rather the focus is on examining a community's orientations and the weight given to them, followed by the intentional critiquing of one's own orientation leanings to understand and work toward balance. As we have argued, this intentional process of active balancing increases adolescents' agency by expanding opportunities to understand their community and generates pathways toward change, both for the self and the community (c.f., Rand and Cheavens, 2009). That said, we have described an ideal scenario in which both the person and the community seek balance and change, but we also acknowledge that communities vary in their openness to change, including openness to critique by its members. Even under less-than-ideal conditions, however, adolescents can cultivate active balancing as they face contrasting experiences that propel learning, which could include seeking a different community if their agency is restricted for too long.

A need to reconceptualize adolescence

Active balancing can flourish when members of a cultural community of practice, including adolescents, are treated as competent partners who contribute to the community. Unfortunately, it is commonplace for many communities of practice (e.g., institutions, society) to marginalize or exclude adolescents based on skewed beliefs about their supposed lack of capability (Offer and Schonert-Reichl, 1992). Such beliefs, especially in the United States, are historically rooted in past research-based stereotypes (Hall, 1905) that have been maintained and reinforced over time (e.g., Steinberg and Scott, 2003). Not only do we think such beliefs are unwarranted, but we also suggest they deprive adolescents of opportunities to integrate, organize, and understand experiences as a participatory member of society into a coherent whole. That is, such bias deprives adolescents of opportunities to cultivate active balancing within the context of being a full member of society. Supporting adolescents' cultivation of active balancing, then, will require overcoming deeply held biases about adolescents. For cultural communities of practice willing to include adolescents as competent partners, the supports for active balancing outlined earlier offer a pathway forward.

One community of practice ripe for supporting active balancing is parenting. Research highlights that parenting, especially during the adolescent years, can be challenging and confusing (Hancock, 2014). Part of the challenge, we suggest, has been the absence of an articulated aim of adolescence (beyond a time of transition), leaving parents to rely on their own experience as an adolescent and any fragments of research messages based on siloed approaches. By defining active balancing as the developmental aim of adolescence, pathways can be generated to support this aim. One pathway for parents is cultivating their own active balancing capacity, thereby positioning them to support their adolescent child's active balancing. Parents can engage in active balancing to identify their own leanings and preferences toward different orientations and seek contrasting experiences to enrich their own cultivation toward active balancing. In doing so, we think parents can help support similar opportunities for contrasting experiences to their adolescent child, while the parent models active balancing themselves (Wiese and Freund, 2011).

Toward “balance-being”

Finally, we have positioned active balancing as a process that promotes positive mental health and wellbeing, as well as promoting thriving and resilience, but not by directly intervening through a program, such as curricula to teach missing skills (e.g., SEL skill). Rather, active balancing is a way of being in and across one's cultural communities of practices that ultimately results in adolescent's ability to exercise agency, thereby potentially reducing many of the precursors (e.g., isolation) of mental health problems (e.g., depression). For example, belonging to a group or community is important for wellbeing and health among adolescents (Leary and Baumeister, 1995). Research suggests that adolescents may be especially sensitive to the impacts of not belonging (ostracism, isolation), possibly because of neural developments that heighten sensitivity to social and identity-related information (Allen, 2020). Thus, adolescents may be particularly sensitive to matters of belonging or not belonging within their cultural communities. Cultivating active balancing within one's communities of practice could increase belonging to a community and inculcate an authenticity for participating, especially when members and the community seek balance and change. Ultimately, we think cultivating one's active balancing capacity should result in “balanced-being” (self) capable of dynamic growth across the lifespan.

Conclusion and implications

Active balancing has important implications for educators, researchers, parents, and youth workers. To support adolescents in managing the competing demands of different orientations, adults, such as youth workers, teachers, and parents, can be instrumental in creating environments that model and support active balancing. Each environment, such as organized youth programs (e.g., sport team), can provide intentional opportunities for adolescents to experience contrasting orientations, especially experiences that challenge assumptions about how the world works. Ideally, adults would model active balancing themselves while creating conditions to support the same for adolescents. Toward this end, educators and youth workers, for example, can integrate reflective practices into their pedagogy that prompts adolescents to identify, discuss, and balance orientations. Part of these reflective practices should involve embracing and exploring the natural tensions that arise from orientations. We caution adults, here, not to turn reflective practices into a formulaic practice that becomes a substitute for the dynamic and ongoing process of cultivating active balancing habits. Similarly, if adults are unwilling to explore and appropriately share their experience of tensions between orientations, adolescents will likely perceive the “hypocrisy” and see active balancing as irrelevant for adults.

Supporting active balancing is not solely, or even primarily, the domain of adults, however. Adolescents can intentionally create spaces for open dialogue to explore how they balance orientations, the tensions that arise, how they navigate challenges, etc. We do not see an imperative for these spaces to be formal or structured, rather the imperative is that adolescents in the space intentionally discuss and explore active balancing. Some minimal level of understanding of active balancing would be needed, whether in the form of access to materials on framework or through key relationships, such as Zeldin et al. (2013) work on youth-adult partnerships.

Admittedly, the active balancing framework is new and, as of yet, there is no research directly on it. We see several research avenues from this proposed model. Clearly there is a need to develop measures for key constructs, especially orientations, in order to test and validate the model. Assessing the “AND” vs. “OR” aspect of orientations will be essential. While measure development can be an arduous and time-consuming task, the advent of AI may be able to assist in the development process to shorten the time required. We also suggest including adolescents in any measure development process, not simply to benefit from their voice, but also to support their engagement and agency.

With measures of orientations developed, even if they are not fully tested, researchers can design studies to understand the potential associations of orientations and various outputs (see Figure 1). Research studies need not favor one method or another (e.g., quantitative). If, as proposed, an AND approach to orientations is the developmental aim of adolescence, we would expect to see positive associations with indicators reflecting a greater tolerance for tension, difference, and ambiguity, greater psychological and emotional stability, and ability to effectively engage in different communities of practice as agentic member of the community who can also contribute to change in it. We also see a need for research examining active balancing in relation to concepts like belonging, mindfulness, and identity. Although we did not directly discuss active balancing in relation to important socio-cultural contexts (e.g., gender), these contexts are part of the idea of cultural communities of practice. Thus, these contexts need to be examined to comprehend the strengths and limitations of active balancing.

In conclusion, we presented a novel framework for understanding adolescence through the lens of active balancing, offering a shift from viewing this developmental period as one dominated by “storm and stress” to recognizing it as a time of profound growth and learning. By cultivating the capacity for active balancing, adolescents can develop a coherent, agentic self capable of navigating the complexities of modern life. This approach emphasizes the importance of balancing orientations—such as change vs. stability or relationships vs. achievement—in ways that promote adaptability, resilience, and wellbeing. The active balancing framework has broad implications for researchers, educators, practitioners, and importantly, for adolescents themselves. Future research must focus on developing reliable measures for assessing orientations and balancing capacities, alongside exploring the model's applications across diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts. By supporting active balancing, we can foster adolescents' development into balanced, self-aware individuals capable of contributing meaningfully to their communities and society at large.

Author contributions

AJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ML: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Basseches, M. (1980). Dialectical schemata: a framework for the empirical study of the development of dialectical thinking. Hum. Dev. 23, 400–421. doi: 10.1159/000272600

Basseches, M. (2005). The development of dialectical thinking as an approach to integration. Integral Review 1, 47–63.

Baumeister, R. F. (2011). Self and identity: a brief overview of what they are, what they do, and how they work. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1234, 48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06224.x

Baumeister, R. F., and Hippel, W. V. (2020). Meaning and evolution: why nature selected human minds to use meaning. Evoluti. Stud. Imaginat. Cult. 4, 1–18. doi: 10.26613/esic.4.1.158

Baxter, L. A. (2004). A tale of two voices: relational dialectics theory. J. Family Commun. 4, 181–192. doi: 10.1207/s15327698jfc0403&4_5

Berzonsky, M. D. (2011). “A social-cognitive perspective on identity construction,” in Handbook of Identity Theory and Research, eds. S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, and V. L. Vignoles (New York: Springer New York), 55–76.

Best, J. R., and Miller, P. H. (2010). A developmental perspective on executive function. Child Dev. 81, 1641–1660. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01499.x

Bitsko, R. H., Claussen, A. H., Lichstein, J., Black, L. I., Jones, S. E., Danielson, M. L., et al. (2022). Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Suppl. 71:1. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1

Blakemore, S.-J. (2012). Development of the social brain in adolescence. J. R. Soc. Med. 105, 111–116. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110221

Branje, S., De Moor, E. L., Spitzer, J., and Becht, A. I. (2021). Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: a decade in review. J. Res. Adolesc. 31, 908–927. doi: 10.1111/jora.12678

Brockmeier, J. (2009). Reaching for meaning: human agency and the narrative imagination. Theory Psychol. 19, 213–233. doi: 10.1177/0959354309103540

Brough, P., Timms, C., Chan, X. W., Hawkes, A., and Rasmussen, L. (2020). “Work–life balance: definitions, causes, and consequences,” in Handbook of Socioeconomic Determinants of Occupational Health, ed. T. Theorell (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 473–487.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of Meaning: Four Lectures on Mind and Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University press.

Burke, P. J., and Stryker, S. (2016). “Identity theory: progress in relating the two strands,” in New Directions in Identity Theory and Research, eds. J. E. Stets and R. T. Serpe (New York, NY: Oxford Academic). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190457532.003.0023

Carson, S. H., and Langer, E. J. (2006). Mindfulness and self-acceptance. J. Ration.-Emot. Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 24, 29–43. doi: 10.1007/s10942-006-0022-5

Christiansen, C. H., and Matuska, K. M. (2006). Lifestyle balance: a review of concepts and research. J. Occupat. Sci. 13, 49–61. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2006.9686570

Comstock, D. L., Hammer, T. R., Strentzsch, J., Cannon, K., Parsons, J., and Ii, G. S. (2008). Relational-cultural theory: a framework for bridging relational, multicultural, and social justice competencies. J. Counsel. Dev. 86, 279–287. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00510.x

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. HarperPerennial, New York 39, 1–16.

Davidow, J. Y., Insel, C., and Somerville, L. H. (2018). Adolescent development of value-guided goal pursuit. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.05.003

Duffy, M. E., Twenge, J. M., and Joiner, T. E. (2019). Trends in mood and anxiety symptoms and suicide-related outcomes among US undergraduates, 2007–2018: evidence from two national surveys. J. Adolesc. Health 65, 590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.033

Dumontheil, I., Apperly, I. A., and Blakemore, S. (2010). Online usage of theory of mind continues to develop in late adolescence. Dev. Sci. 13, 331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00888.x

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., and Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 100:363. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

Fair, D. A., Dosenbach, N. U. F., Church, J. A., Cohen, A. L., Brahmbhatt, S., Miezin, F. M., et al. (2007). Development of distinct control networks through segregation and integration. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 104, 13507–13512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705843104

Frankl, V. E. (1946). “Ein Psycholog erlebt das Konzentrationslager,” in Österreichische Dokumente Zur Zeitgeschichte, 1. Available at: https://ixtheo.de/Record/1075959683 (accessed April 16, 2004).

Galleno, L., and Liscano, M. (2013). Revitalizing the self: assessing the relationship between self-awareness and orientation to change. Int. J. Human. Soc. Sci. 3, 62–71.

Galván, A. (2010). Adolescent development of the reward system. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4:1018. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.006.2010

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am. Psychol.48:26. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26

Hall, G. S. (1905). Adolescence: Its Psychology and its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education (Vol. 2). D. New York City: Appleton.

Hancock, D. (2014). Consequences of parenting on adolescent outcomes. Societies 4, 506–531. doi: 10.3390/soc4030506

Handley, K., Sturdy, A., Fincham, R., and Clark, T. (2006). Within and beyond communities of practice: making sense of learning through participation, identity and practice*. J. Managem. Stud. 43, 641–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00605.x

Hansen, D. M., and Jessop, N. (2017). “A context for self-determination and agency: adolescent developmental theories,” in Development of Self-Determination Through the Life-Course, eds. M. L. Wehmeyer, K. A. Shogren, T. D. Little, and S. J. Lopez (Amsterdam: Springer Netherlands), 27–46.

Hansen, D. M., Larson, R. W., and Dworkin, J. B. (2003). What adolescents learn in organized youth activities: a survey of self-reported developmental experiences. J. Res. Adolesc. 13, 25–55. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.1301006

Hansen, D. M., Moore, E. W., and Jessop, N. (2017). Youth program adult leader supports and development of adolescents' capacity for agency. J. Res. Adolesc. 28, 505–519. doi: 10.1111/jora.12355

Hansen, D. M., Skorupski, W. P., and Arrington, T. L. (2010). Differences in developmental experiences for commonly used categories of organized youth activities. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 31, 413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.07.001

Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., and Sumner, R. (2013). Addressing important questions in the field of adolescent purpose. Child Dev. Perspect. 7, 232–236. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12048

Hogg, M. A. (2007). Uncertainty–identity theory. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 39, 69–126. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)39002-8

Hogg, M. A. (2021). Self-uncertainty and group identification: consequences for social identity, group behavior, intergroup relations, and society. Adv. Exp. Social Psychol. 64, 263–316. doi: 10.1016/bs.aesp.2021.04.004

Ivcevic, Z., and Nusbaum, E. C. (2017). “From having an idea to doing something with it: self-regulation for creativity,” in The Creative Self (London: Elsevier), 343–365. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128097908000200 (accessed April 16, 2024).

Jordan, J. V. (2008). Recent developments in relational-cultural theory. Women Ther. 31, 1–4. doi: 10.1080/02703140802145540

Kabat-Zinn, J., and Hanh, T. N. (2009). Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. Buena Park, CA: Delta.

Kaufman, S. B. (2023). Self-actualizing people in the 21st century: integration with contemporary theory and research on personality and wellbeing. J. Human. Psychol. 63, 51–83. doi: 10.1177/0022167818809187

Keating, D. P. (2004). “Cognitive and brain development,” in Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, eds R. M. Lerner and L. Steinberg (London: Wiley), 45–84.

Kegan, R. (1982). The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kilford, E. J., Garrett, E., and Blakemore, S.-J. (2016). The development of social cognition in adolescence: an integrated perspective. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 70, 106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.016

Labouvie-Vief, G., Grühn, D., and Studer, J. (2010). “Dynamic integration of emotion and cognition: equilibrium regulation in development and aging,” in The Handbook of Life-Span Development (1st ed.), eds. R. M. Lerner, M. E. Lamb, and A. M. Freund (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley).

Lally, P., and Gardner, B. (2013). Promoting habit formation. Health Psychol. Rev. 7, S137–S158. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2011.603640

Larson, R. W., and Angus, R. (2011). Adolescents' development of skills for agency in youth programs: learning to think strategically. Child Dev. 82, 277–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01555.x

Larson, R. W., and Hansen, D. M. (2005). The development of strategic thinking: learning to impact human systems in a youth activism program. Hum. Dev. 48, 327–349. doi: 10.1159/000088251

Leary, M. R., and Baumeister, R. F. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Luna, B., Garver, K. E., Urban, T. A., Lazar, N. A., and Sweeney, J. A. (2004). Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Dev. 75, 1357–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00745.x

Luna, B., Marek, S., Larsen, B., Tervo-Clemmens, B., and Chahal, R. (2015). An integrative model of the maturation of cognitive control. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 38, 151–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-034054

Luthar, S. S., Kumar, N. L., and Zillmer, N. (2020). High-achieving schools connote risks for adolescents: Problems documented, processes implicated, and directions for interventions. Am. Psychol. 75:983. doi: 10.1037/amp0000556

Marek, S., Hwang, K., Foran, W., Hallquist, M. N., and Luna, B. (2015). The contribution of network organization and integration to the development of cognitive control. PLoS Biol. 13:e1002328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002328

McAdams, D. P., and Cox, K. S. (2010). “Self and identity across the life span,” in The Handbook of Life-Span Development (1st ed.), R. M. Lerner, M. E. Lamb, and A. M. Freund (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley).

McMillan, D. W., and Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: a definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 14, 6–23.

Menon, V. (2013). Developmental pathways to functional brain networks: emerging principles. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 627–640. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.015

Mojtabai, R., and Olfson, M. (2020). National trends in mental health care for US adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 703–714. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0279

Nowell, B., and Boyd, N. M. (2014). Sense of community responsibility in community collaboratives: advancing a theory of community as resource and responsibility. Am. J. Community Psychol. 54, 229–242. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9667-x

Offer, D., and Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (1992). Debunking the myths of adolescence: findings from recent research. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiat. 31, 1003–1014. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00001

Pfeifer, J. H., and Berkman, E. T. (2018). The development of self and identity in adolescence: neural evidence and implications for a value-based choice perspective on motivated behavior. Child Dev. Perspect. 12, 158–164. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12279

Pfeifer, J. H., Kahn, L. E., Merchant, J. S., Peake, S. J., Veroude, K., Masten, C. L., et al. (2013). Longitudinal change in the neural bases of adolescent social self-evaluations: effects of age and pubertal development. J. Neurosci. 33, 7415–7419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4074-12.2013

Pintrich, P. R. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting and sustaining self-regulated learning. Int. J. Educ. Res. 31, 459–470. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(99)00015-4

Rakesh, D., Elzeiny, R., Vijayakumar, N., and Whittle, S. (2023). A longitudinal study of childhood maltreatment, subcortical development, and subcortico-cortical structural maturational coupling from early to late adolescence. Psychol. Med. 53, 7525–7536. doi: 10.1017/S0033291723001253

Rand, K. L., and Cheavens, J. S. (2009). “Hope theory,” in Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (Oxford: Oxford Academic), 323–333.

Rivera, F., García-Moya, I., Moreno, C., and Ramos, P. (2013). Developmental contexts and sense of coherence in adolescence: a systematic review. J. Health Psychol. 18, 800–812. doi: 10.1177/1359105312455077

Roberts, B. W., Lejuez, C., Krueger, R. F., Richards, J. M., and Hill, P. L. (2014). What is conscientiousness and how can it be assessed? Dev. Psychol. 50:1315. doi: 10.1037/a0031109

Rogoff, B. (2016). Culture and participation: a paradigm shift. Curr. Opini. Psychol. 8, 182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.12.002

Romer, D., and Hansen, D. (2021). “Positive youth development in education,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 75–108. Available at: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/50022/978-3-030-64537-3.pdf?sequence=1#page=99

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. American Psychologist 55, 68. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Schimmelpfennig, J., Topczewski, J., Zajkowski, W., and Jankowiak-Siuda, K. (2023). The role of the salience network in cognitive and affective deficits. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 17:1133367. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2023.1133367

Seeley, W. W. (2019). The salience network: a neural system for perceiving and responding to homeostatic demands. J. Neurosci. 39, 9878–9882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1138-17.2019

Senko, C. (2019). When do mastery and performance goals facilitate academic achievement? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 59, 101795. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101795

Shelton, J., and Dodd, S. J. (2021). Binary thinking and the limiting of human potential. Public Integrity 23, 624–635. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2021.1988405

Sinhababu, N. (2017). Humean Nature: How Desire Explains Action, Thought, and Feeling. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=izNdDgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=sinhababu+2017+desire&ots=2BDp6HBNNq&sig=O0W8mzbohn5jCH9KonopSMlCI6o

Snyder, W., Uddin, L. Q., and Nomi, J. S. (2021). Dynamic functional connectivity profile of the salience network across the life span. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42, 4740–4749. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25581

Steinberg, L., and Scott, E. S. (2003). Less guilty by reason of adolescence: developmental immaturity, diminished responsibility, and the juvenile death penalty. Am. Psychol. 58:1009. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.12.1009

Stevens, M. C., Skudlarski, P., Pearlson, G. D., and Calhoun, V. D. (2009). Age-related cognitive gains are mediated by the effects of white matter development on brain network integration. Neuroimage 48, 738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.065

Stewart, K., and Townley, G. (2020). How far have we come? an integrative review of the current literature on sense of community and well-being. Am. J. Commun, Psychol. 66, 166–189. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12456

Struyven, K., Dochy, F., Janssens, S., and Gielen, S. (2008). Students' experiences with contrasting learning environments: the added value of students' perceptions. Learn. Environm. Res. 11, 83–109. doi: 10.1007/s10984-008-9041-8

Syvertsen, A. K., Scales, P. C., Wu, C.-Y., and Sullivan, T. K. (2024). Promoting character through developmental experiences in conservation service youth programs. J. Posit. Psychol. 19, 834–848. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2023.2218331

Uddin, L. Q., Yeo, B. T. T., and Spreng, R. N. (2019). Towards a universal taxonomy of macro-scale functional human brain networks. Brain Topogr. 32, 926–942. doi: 10.1007/s10548-019-00744-6

Urdan, T., and Kaplan, A. (2020). The origins, evolution, and future directions of achievement goal theory. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61:101862. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101862

Van den Broeck, A., Vander Elst, T., Baillien, E., Sercu, M., Schouteden, M., De Witte, H., et al. (2017). Job demands, job resources, burnout, work engagement, and their relationships: An analysis across sectors. J. Occup. Environm. Med. 59, 369–376. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000964

Vansteenkiste, M., Aelterman, N., De Muynck, G.-J., Haerens, L., Patall, E., and Reeve, J. (2018). Fostering personal meaning and self-relevance: a self-determination theory perspective on internalization. J. Exp. Educ. 86, 30–49. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2017.1381067

Váša, F., Romero-Garcia, R., Kitzbichler, M. G., Seidlitz, J., Whitaker, K. J., Vaghi, M. M., et al. (2020). Conservative and disruptive modes of adolescent change in human brain functional connectivity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 117, 3248–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906144117

Veraksa, N., Basseches, M., and Brandão, A. (2022). Dialectical thinking: a proposed foundation for a post-modern psychology. Front. Psychol. 13:710815. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.710815

Weiss, M., Hoegl, M., and Gibbert, M. (2013). The influence of material resources on innovation projects: the role of resource elasticity. R&D Managem. 43, 151–161. doi: 10.1111/radm.12007

Weiss, M., Hoegl, M., and Gibbert, M. (2017). How does material resource adequacy affect innovation project performance? A meta-analysis. J. Prod. Innovat. Managem. 34, 842–863. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12368

Wiese, B. S., and Freund, A. M. (2011). Parents as role models: parental behavior affects adolescents' plans for work involvement. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 35, 218–224. doi: 10.1177/0165025411398182

Keywords: adolescence, active balancing, self, developmental aim, wellbeing, identity, personal agency, balanced-being

Citation: Juneja A, Hansen DM and Lemon MP (2024) Cultivating the capacity for active balancing during adolescence: pathways to a coherent self. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2:1418666. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2024.1418666

Received: 16 April 2024; Accepted: 23 September 2024;

Published: 09 October 2024.

Edited by:

Jordan Ashton Booker, University of Missouri, United StatesReviewed by:

Jochebed Gethsemane Gayles, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesSahitya Maiya, University of New Hampshire, United States

Copyright © 2024 Juneja, Hansen and Lemon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David M. Hansen, ZGhhbnNlbjFAa3UuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Abhishek Juneja†

Abhishek Juneja† David M. Hansen

David M. Hansen Michael P. Lemon

Michael P. Lemon