- Wellesley Centers for Women, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA, United States

Introduction: Father-adolescent talk about sex can protect adolescents from sexual risk behaviors. However, few studies explore how family members view fathers' talk with adolescents about sex and relationships. An understanding of how fathers, mothers, and adolescents view fathers' roles in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships can help to guide fathers' talk with adolescents and inform programs to provide targeted support for father-adolescent communication about sex and relationships.

Methods: This study investigates family perceptions of father-adolescent communication about sex and relationships by triangulating data from fathers, mothers, and adolescents using content analysis to conduct between-family analysis and within-family approaches with 15 families (n = 45 individuals) with high school-aged adolescents from across the U.S.

Results: Analyses showed agreement on the importance of fathers' roles in family talk about sex. The findings showed shared recognition of the importance of fathers' roles in family talk about sex. Between-group analyses showed that fathers, mothers, and adolescents view fathers' roles as emotional supports and open communicators with their adolescents about sex and relationships and as educators and advisors for their adolescent children. Within-family analysis showed that families often agreed that there were gender differences in how fathers talked with their sons and daughters, but family members expressed different views on how adolescents' gender impacts father-adolescent communication about sexual topics.

Discussion: These findings may encourage fathers who are uncertain about the value of their roles in talking with their adolescent children about sex and relationships. They also highlight the importance of examining how fathers' messages to their adolescents about sex and relationships may continue to follow patterns of gender stereotypes. This is the first study to qualitatively triangulate perspectives of fathers, mothers, and adolescents on father-adolescent communication about sex and relationships. Since fathers are often less involved than mothers in parent-adolescent communication about sex and relationships, an understanding of how mothers and adolescents see fathers' roles and messages can help provide a pathway for fathers' engagement which works within a family system.

1 Introduction

Fathers' talk with adolescents about sex can help reduce adolescents' sexual risk behavior (Wright, 2009; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012), yet most research and intervention programs focus on the mother-adolescent dyad (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012; Widman et al., 2016). Many fathers believe that it is important to talk with their adolescents about these topics (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019; Grossman et al., 2022), but fathers are less likely than mothers to talk with adolescents about sex and relationships (Sneed et al., 2013; Grossman et al., 2021). This may in part relate to fathers' discomfort talking with adolescents about sexual issues and lack of clarity about their roles in these conversations and how to initiate them (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019; Grossman et al., 2022; Scull et al., 2022). While some qualitative studies investigate how fathers understand and experience talk with adolescents about sex and relationships (e.g., Randolph et al., 2017; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019; Scull et al., 2022), little research explores how other family members view this communication. As many fathers seek to identify and fulfill their roles in supporting their adolescents' sexual health, an understanding of how adolescents and other caregivers in the family (often mothers) view fathers' roles in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships can help to guide fathers' talk with adolescents about sex and relationships. It can also inform programs which provide targeted support for fathers' talk with adolescents about sex and relationships.

High school (age 14–18) is a key time for adolescents' development of relationships and sexual behavior (Giordano et al., 2006) and provides an important window for fathers to talk with adolescents about sexual issues. Only 16% of 9th grade adolescents have had sex, while 48% of adolescents have had sex by the end of high school [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2021]. Talk with adolescents about sex is more effective in reducing sexual risk behaviors before adolescents are sexually active (Clawson and Reese-Weber, 2003). However, more than 40% of adolescents have sex before parents talked with them about protection methods or sexually transmitted infections (Beckett et al., 2010). Therefore, understanding the roles fathers can play in talk with their high school adolescents about sexual issues is a meaningful way to support adolescents' sexual health.

1.1 Parent sexuality communication

Much research documents mothers' roles as the primary family source of talk with adolescents about sex (Flores and Barroso, 2017) and the protective impact of mother-adolescent communication about sex on adolescent sexual behavior (Widman et al., 2016; Scull et al., 2022) as well as sexual health attitudes and self-efficacy (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2007; Hutchinson and Montgomery, 2007; Sneed et al., 2015). Parent-adolescent talk about sex is most effective when adolescents see parents as knowledgeable, efficacious, and comfortable with talk about sex (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006; Flores and Barroso, 2017), but the specific components that make father-adolescent communication effective are not well understood. Initial findings suggest that fathers' talk with adolescents about sex can play a protective role (Wright, 2009; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012; Grossman et al., 2022), although research is mixed about its impact, with stronger effects on adolescents' sexual behavior for mothers' than fathers' talk with adolescents about sex (Widman et al., 2016). Research has not yet explored whether father-adolescent talk about sex has similar impacts for sons and daughters, but parent-adolescent talk (largely assessed with mothers and adolescents) shows greater protective impact on contraceptive and condom use for daughters than sons (Widman et al., 2016). The impact of family communication about sex can be understood through sexual socialization theory, which describes a process through which adolescents learn about sexual beliefs and values through parents' messages to their children (Shtarkshall et al., 2007) through avenues such as conversations, shared cultural messages, and role modeling. These beliefs in turn shape adolescents' own sexual values and beliefs (Ashcraft and Murray, 2017).

Fathers may differ from mothers in their approaches to, content of, and role in talk with their adolescents about sex and relationships (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019; Scull et al., 2022). While research identifies direct communication (i.e. talk about sexual issues) as a primary approach for mother-adolescent communication (Wright, 2009; Scull et al., 2022), fathers use multiple ways to bring up sexual topics with their adolescents, including direct communication, less straight-forward approaches, and leading by example (Grossman et al., 2021, 2022). Similar to mothers, fathers often focus their talk with adolescents on areas they identify as important for adolescents' health and safety, such as healthy and unhealthy relationships and pregnancy and STI (sexually transmitted infection) prevention (Sneed et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2021; Grossman et al., 2022). Qualitative studies suggest that fathers see their responsibility to adolescents in talk about sex as educators and advisors, responsive listeners, and role models (Grossman et al., 2022). Initial findings suggest that adolescents also view fathers as making meaningful contributions to talk about sex, with male adolescents identifying a need for father-adolescent talk about specifics of condom use and talking with adolescents about male perspectives and their own experiences (Flores and Barroso, 2017; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019). However, few studies investigate how adolescents view fathers' role and messages in father-adolescent talk about sex.

We know of no studies which investigate how mothers view fathers' talk with adolescents about sex. Parenting research shows that children's outcomes improve with greater collaboration between their parents (e.g., Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2023). Developing programs to support father-adolescent talk about sex and relationships also need to consider the larger family system, in order to promote healthy and effective communication. The lack of research on mothers' perspectives on father-adolescent communication about sexual topics is a key gap in informing program development. In addition, as mothers are often the primary sex educators of their adolescents (Wright, 2009; Scull et al., 2022), their perceptions are important. Mothers also play a key role in gatekeeping fathers' level of engagement with their children (Schoppe-Sullivan and Altenburger, 2019), which suggest that their support could open up opportunities for father to talk with their adolescent children about sex and relationships.

Dyadic research on mother-adolescent communication about sex may help to understand the need to explore multiple perspectives on father-adolescent communication. Prior research on mother-adolescent communication shows a disconnect between how mothers and adolescents view their conversations with each other about sexual topics with adolescents less likely than their mothers to report that a conversation about a sexual topic (e.g., birth control, delaying sex) occurred (Atienzo et al., 2015; Scull et al., 2022). This may in part reflect parents' vague comments about sex which can be ambiguous for adolescents to interpret (Aronowitz and Agbeshie, 2012) and tend to occur when parents feel awkward or uncomfortable talking with their adolescents about sexual topics (Murphy-Erby et al., 2011; Alcalde and Quelopana, 2013). Regardless of whether adolescents' perceptions of talk with parents about sex are accurate, it is adolescents' perceptions of communication (rather than those of parents) which are predictive of adolescents' reduced sexual risk behavior (Kapungu et al., 2010). Therefore, gaps in how parents and adolescents perceive family talk about sex are important to understand. It is also important to explore how adolescents and fathers perceive father-adolescent talk about sex and relationships, which has not yet been investigated. Research that investigates multiple family perspectives on father-adolescent communication can help to paint a fuller picture of its roles and potential impact.

1.2 Role of adolescent gender and development

Adolescent gender plays a key role in mothers' and fathers' talk with adolescents about sex, shaping its content, frequency, and impact (Wright, 2009; Widman et al., 2016; Flores and Barroso, 2017; Evans et al., 2020). Therefore, research is needed to explore how families view fathers' communication with sons and daughters about sexual topics. While mothers are more likely to talk with their daughters than sons about sex, fathers more often talk with their sons than daughters about sex (Wright, 2009; Evans et al., 2020). Fathers often express particular discomfort talking with their daughters about sex, identifying a lack of role clarity and fear of being intrusive or ineffective, as well as belief that mothers should take this role (Wyckoff et al., 2008; Kachingwe et al., 2023; Grossman et al., 2024). Questions about whether fathers should have a role in talk with their adolescents about sex make uncertainty of fathers' roles salient in ways which may differ from mothers. Some fathers point out their daughters' discomfort talking with a parent of a different gender, while others note that male perspectives can be useful for both sons and daughters (Grossman et al., 2022). One study found that adolescent daughters viewed fathers' discomfort talking with them about sex as a barrier to effective father-daughter communication (Nielsen et al., 2013). Fathers also talk more with their daughters than sons about delaying sex (Flores and Barroso, 2017), suggesting that fathers may pass on traditional gender role expectations that daughters must resist boys' sexual advances (Flores and Barroso, 2017; Evans et al., 2020). Differences in father-adolescent communication with their sons and daughters show why it is useful to explore family members' beliefs about the role of adolescent gender in father-adolescent communication about sex.

1.3 The current study

Understanding how fathers, mothers, and adolescents view fathers' roles and messages to adolescents about sex and relationships can help identify opportunities for fathers to engage in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships in ways that fit within the family system. For example, fathers may assume that mothers and adolescents would not welcome or value their engagement in talk with their adolescents about sex and relationships (Wyckoff et al., 2008; Grossman et al., 2024), while studies suggest that adolescents want fathers to be part of these conversations (Nielsen et al., 2013; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019). Fathers' belief that mothers and adolescents want fathers to join these conversations may increase fathers' engagement with adolescents in talk about sex and relationships. Further, no papers triangulate how family perspectives of mothers, fathers, and adolescents within the same family see fathers' roles. Comparing individuals in the same family can add a unique understanding about the family system in which father-adolescent communication about sex occurs rather than solely investigating fathers, mothers, and adolescents as separate groups.

In our prior research (Grossman et al., 2022, 2024), we analyzed interviews with 43 fathers, including the fathers from this sample, to assess fathers' perspectives on the content and process of their talk with their teens about sex and relationships. The 15 fathers in the current sample were drawn from that larger sample of fathers included in our prior work, while the 15 mothers and 15 adolescents included in this sample have not been included in prior publications. The current research addresses gaps in our prior work by including mothers' and teens' perspectives in order to take a more holistic family-based approach to understanding father-teen communication about sexual topics. This is particularly important as family members' perspectives often differ in terms of how they describe the content and frequency of family communication about sex (Grossman et al., 2017; Scull et al., 2022). This study contributes to the field as it is the first study to triangulate fathers, mothers, and adolescents' perspectives on father-adolescent communication about sex and relationships.

To compare how fathers, mothers, and adolescents view father-adolescent talk about sex and to assess how individuals in the same family view this communication, this study will use both between-family and within-family analytic approaches. This study uses a between-family approach to do in-depth investigation of how fathers, mothers, and adolescents separately view fathers' roles and messages in talk with adolescents about sex. This study uses a within-family analysis to investigate how members of the same family view fathers' roles in talk with the adolescent about sex in similar and different ways.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Recruitment and participants

We worked with several community programs across the U.S. to invite fathers of high school-aged adolescents (14–18 years old) to participate in our interview study. We advertised through online flyers in English and Spanish and conducted Zoom informational sessions in collaboration with community programs. Participants were instructed to complete an online survey to provide contact information and establish their eligibility to participate in the study. Eligible participants identified as a father (biological, step, adoptive, or foster) and had a relationship with their high school-aged adolescent. Of the 64 fathers who completed the online survey, 21 fathers were either not eligible or chose not to move forward with the interview process. Those who met the requirements were contacted via phone call, text, or email to participate in interviews. Adolescents of participating fathers and an additional parent, if identified, were invited to participate in their own interviews. Only adolescents with parental consent to participate were contacted. A total of 71 interviews were conducted in English and 10 in Spanish. Forty-three fathers, 16 mothers, and 22 adolescents were interviewed as part of a larger study. Out of the 43 fathers, 15 were part of a family where the mother and adolescent also participated in interviews. These 15 family triads of fathers, mothers, and adolescents make up the sample for this study.

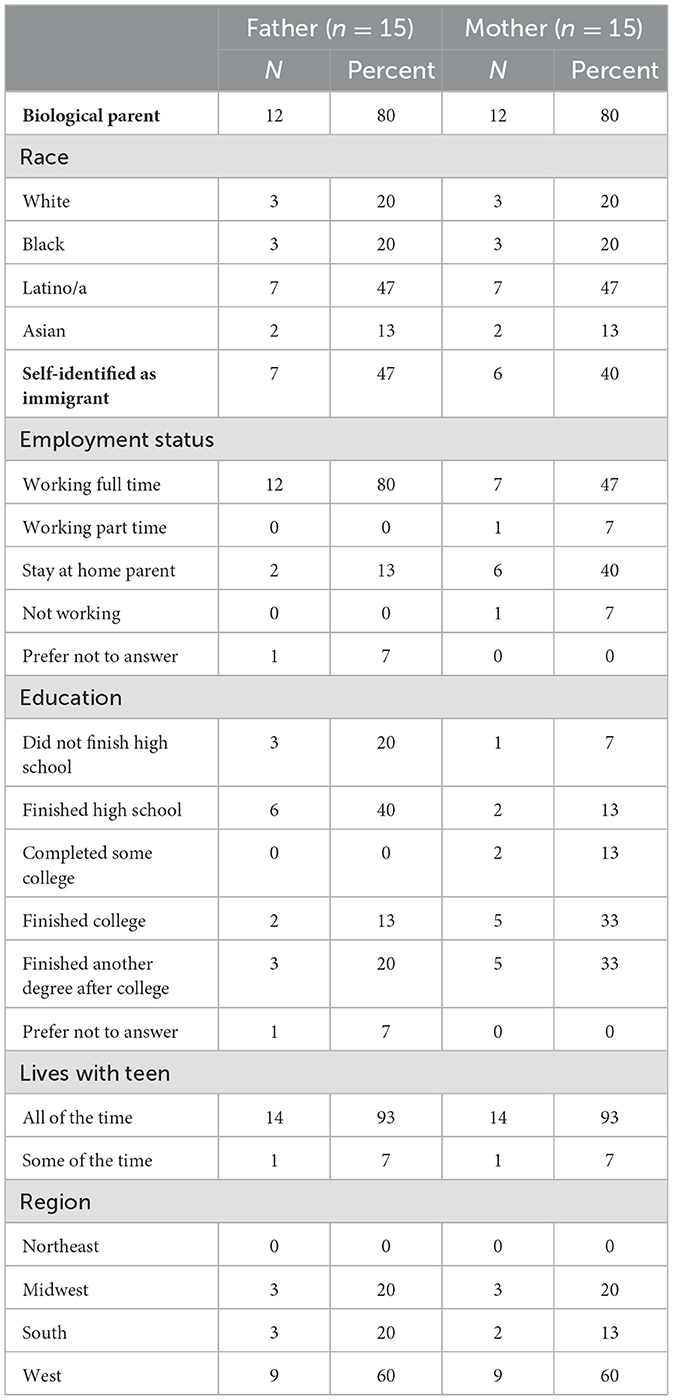

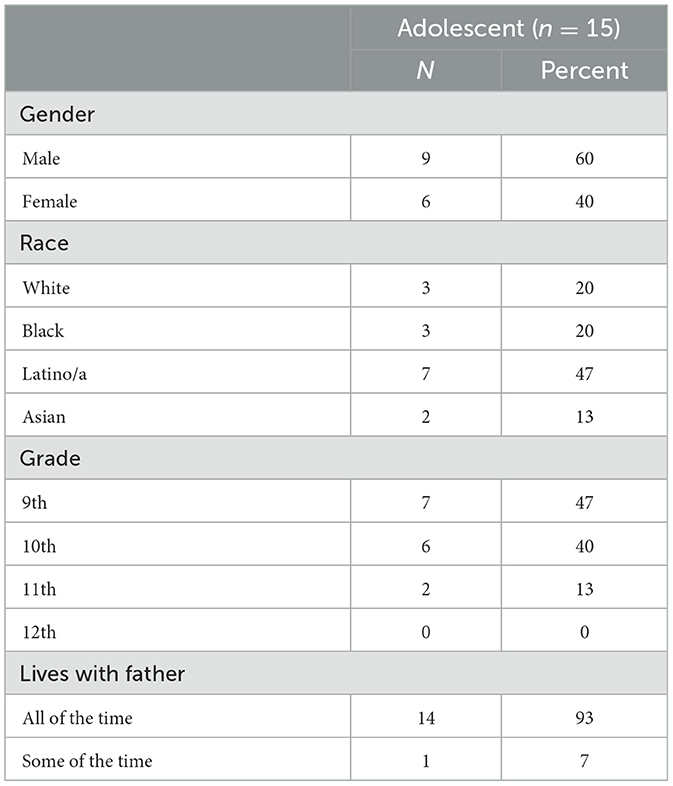

The parents in our sample of 15 triads live throughout the U.S (see Table 1). Over half (60%, n = 9) of families lives in the Western part of the U.S., 20% (n = 3) lived in the Midwest and 20% (n = 3) of lived in the South. All fathers identified as male and heterosexual. Most fathers were biological (80%, n = 12) and the majority identified as Latino (47%), Black (20%), or White (20%). Most fathers worked full time (80%, n = 12). Fourteen fathers (93%) live with their adolescents all the time. For one family, the father lives with the adolescent some of the time. Seven fathers (47%) self-identified as immigrants to the U.S. Six fathers reported their highest education level (40%) was graduating high school while 5 fathers (33%) reported completing college. All mothers identified as female. Most mothers were biological (80%, n = 12) and the majority identified as Latina/o (47%), Black (20%), or White (20%). Halk of mothers worked full time (47%, n = 7) Fourteen mothers (93%) live with their adolescents all the time. For one family, the teen splits their time between the mother's and father's household. Six mothers (40%) self-identified as immigrants to the U.S. Ten mothers (67%, n = 10) reported completing college. The adolescents in our sample (see Table 2) had an average age of 15 years old (SD = 1.10), and nine identified as male (60%) while six identified as female (40%). All 15 adolescents (100%) lived with their father some or all the time.

We compared sample descriptives for the 15 fathers who were part of the current sample and the 28 fathers who were part of the larger interview study, but who did not have a participating child or second parent. Compared to the larger sample, the 15 fathers who participated in the current study were more likely to live in the Western part of the U.S., (60% vs. 29%), were less likely to identify as White (20% vs. 46%) or Black (20% vs. 39%), and more likely to identify as Latino (47% vs. 11%). Fathers in the current sample were more likely to live with their teen all the time (93% vs. 71%) and have completed a high school degree or less (64% vs. 14%), while fathers in the larger sample were more likely to have completed some college (29% vs. 0%) or have completed a four-year degree or higher degree after college (57% vs. 36%). Fathers in both samples were equally likely to be a biological parent (82% larger vs. 80% current sample).

2.2 Data collection

Interviews were conducted from February to June of 2021. Ranging from 50 min to 1 h and 20 min, most interviews with fathers were ~1 h long. Interviews with mothers were ~1 h, while interviews with adolescents lasted about 45 min. All interviews took place on Zoom where they were recorded and facilitated at a convenient time for the participant. The four interviewers, one of which was the PI, all had previous experience conducting qualitative interviews. Additionally, all interviewers completed a PI-led training to understand the protocol and asked questions in both individual and group settings to further clarify the interview questions. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewers reiterated that the purpose of the study was to better understand how families communicate about the topics of dating, relationships, and sex–especially regarding how fathers and adolescents communicate about these subjects. The interviewer also acknowledged that these topics can be uncomfortable or embarrassing to talk about, which is completely normal. Participants were informed that they could skip any questions they did not want to answer. Then they were asked to think of a pseudonym to protect their identity. Interview protocols were based on the team's prior research on family communication about sex and broader research on father-adolescent communication. Protocols were later modified based on feedback from the interview team and participants in pilot interviews. Fathers, mothers, and adolescents were asked questions in the context of father-adolescent communication about dating, relationships, and sex. Main topics included what a father's role in these conversations entails, what information is important for adolescents to understand, and whether and how adolescent gender plays a role in communicating messages or expectations for adolescents. They were also asked about barriers to father-adolescent communication. Questions varied slightly to be applicable for father, mother, and adolescent interviews. For example, mothers were asked about what they think is important for adolescents to understand, as well as how her response would compare to that of the adolescent's father. Adolescents were asked a modified question about what they think their father views as important for them to know.

2.3 Data analysis

Content analysis was used to identify and organize themes and subthemes found in the interview transcripts (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). First, interview transcripts were coded using NVivo 12.0 (QSR International: Melbourne, Australia) to identify patterns in study data. For between-group analysis, the authors summarized preliminary reflections on themes and subthemes for each group (fathers, mothers, and adolescents). Then themes and subthemes were compared and integrated across the three groups to explore thematic similarities and differences between groups. Themes and subthemes were discussed, edited, and labeled. The authors developed written definitions for each theme and subtheme to create a coding scheme, specifying which content should be included and excluded. Using these definitions, the authors returned to the transcripts for a final round of coding, with additional discussion and revisions of the theme definitions as needed. Since the themes were not mutually exclusive, the same text in a transcript could be coded multiple times. We then used a modified constant comparative analysis (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) to conduct a within-family triangulation analysis to explore how responses from members of each family (father, mother, adolescent) compared to each other (i.e., how responses within a family were consistent or inconsistent for a given topic). For this analysis, we created a document for each main theme identified in content analyses which included responses from each member of a specific family. We read each family's interview (father, mother, adolescent) consecutively to identify themes of agreement and disagreement and areas of focus within each individual family. We then drafted memos comparing responses within each family. Finally, we combined memos across families to identify common patterns within families. Analyses for this paper focused on participants' perceptions of a father's role in talk with the adolescent about sex and relationships, important information that fathers want adolescents to know, and the role of adolescent gender on the messages adolescents receive from their father.

2.4 Rigor

To reinforce the accuracy of the coding, reliability checks were conducted, where reliability is calculated by the number of agreements divided by the total number of codes (Miles and Huberman, 1994). To reduce bias in interpreting the interview content, reliability checks included an individual who did not conduct any of the interviews. Data was coded in groups of five participants from each category of fathers, mothers, and adolescents, after which the inconsistencies were discussed and resolved. The final intercoder reliability is 91%, which demonstrates a high level of agreement between the two coders.

2.5 Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol #201059R, 28 October 2020). All participants provided informed consent before participating in the interviews. Adolescent participants received parental consent to participate, as well as giving their own assent. All participants were informed about the study's purpose and the costs and benefits of participation. They were told that their participation was voluntary and that they could skip any questions or end the interview at any time. Participants also received an explanation of how their privacy would be protected prior to consenting. All participants were offered a $50 gift card for their time and given a list of resources for adolescents' sexual health.

3 Results

3.1 Between family analysis

3.1.1 Between family analysis: father roles in talk about sex and relationships

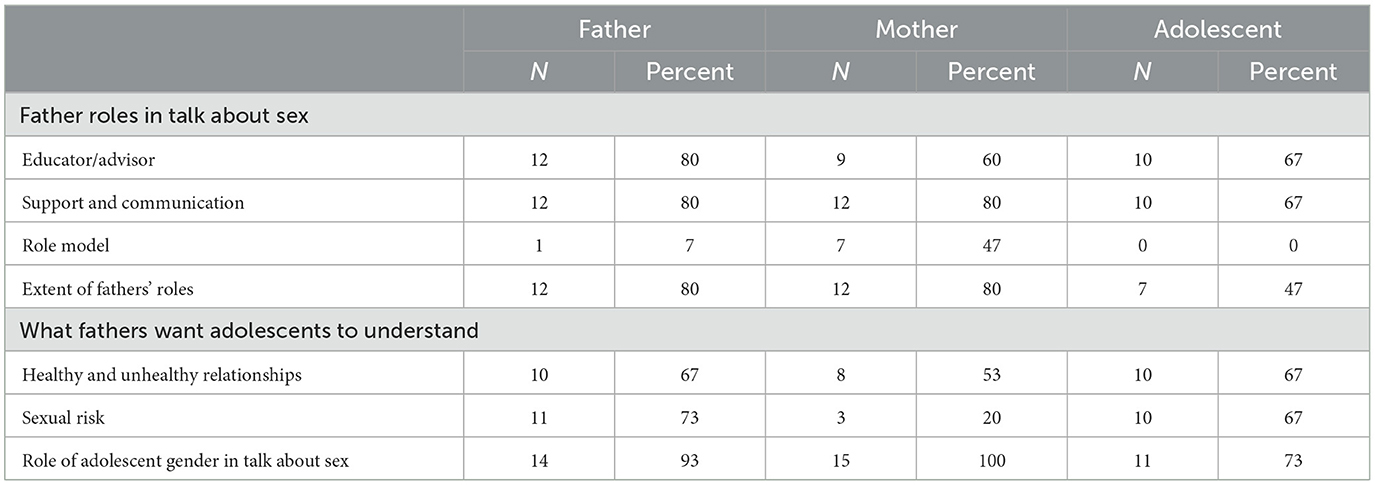

The theme Father roles in talk about sex and relationships focuses on family members' priorities for whether and how fathers should be involved in engaging with their adolescents around sex and relationships (see Table 3). This theme includes four subthemes: educator and advisor, support and communication, role model, and extent of fathers' roles. The subtheme of educator and advisor addresses fathers' roles providing information and guidance for their adolescents regarding sex and relationships. This role was identified as important by fathers (n = 12), mothers (n = 9), and adolescents (n = 10), with a similar focus between groups. Felix talked about his role guiding his son, “He needs to know what's expected of him in engaging with the opposite sex, you know do's and don'ts. He needs to be clear on like what things I am not okay with… I really want him to know like what is socially okay and what's crossing the line.” Vanessa (a mother in the sample) described a similar role for fathers in advising their sons, “The ideal one for me is an informed father, a father that explains things with the right words…that teaches them what is the right thing to do regarding relationships.” Adolescents also described the importance of fathers sharing advice. Jack shared, “The father's role would be like to try and listen and understand what the child is trying to tell them and try and give advice to help them out.”

The subtheme of support and communication addresses fathers' emotional support for their adolescents and open communication about sex and relationships. The importance of this role was expressed similarly by fathers (n = 12), mothers (n = 12), and adolescents (n = 10). One father, Derek2, discussed how he shows support for his daughter, “As long as she knows she could talk to me about whatever she wants to talk about, I think that would be the most important part of this conversation. That she doesn't need to hide anything… That would be my biggest goal, that there is a communication, there is an avenue that if she needs me, I could definitely be there.” Many mothers shared similar beliefs about the importance of fathers' open communication with their adolescents. For example, Elena shared, “I think that both a father and a mother should be willing to engage in open conversation with their children about sex and relationships, at an age-appropriate level.” Adolescents also discussed the key roles fathers play in support and communication. Aaron described how he views a father's role, “That no matter who it is that I'm dating, he'll be supportive of me, unless they're really bad for me. He wants the best for me.”

The role model subtheme focuses on how fathers show adolescents how to act in a healthy relationship, often with an adolescent's mother. This subtheme was primarily discussed by mothers (n = 7), while virtually absent in interviews with fathers (n = 1) and adolescents (n = 0). Several mothers talked about role modeling as one of fathers' most valuable contributions. Joy talked about why she thinks this role is meaningful, “I think that one of the father's roles is modeling, love, and respect for the mother of the adolescent. I think that it's difficult to have conversation about dating and relationships if what you modeled is unhealthy because then the kid doesn't necessarily find you credible.” Mari shared, “having that male role model to ask questions, to be super open with, I feel that's super important.”

The subtheme of extent of fathers' roles focuses on expectations for fathers' involvement in talk with their adolescents about sex and relationships. This topic was discussed more by mothers (n = 12) and fathers (n = 12) than adolescents (n = 7). Participants across all three groups often discussed how both fathers and mothers should be involved in talk with adolescents about sex, with many describing how the extent of parent roles in talk should differ based on adolescent gender. One father, Ted, shared his thoughts on fathers' roles, “The father should, if not lead the conversation, play just a vital part of the conversation, especially giving her (his daughter) perspective about what adolescent boys, you know, what what's on their mind, what they think like, and what they– You know, no matter what they say, we know adolescent boys.” A mother, Mari, talked about the importance of fathers' involvement for all adolescents, with a unique role for male adolescents, “I feel like both of our roles are super important. And of course, with dad, him being a male, right? There's probably things that he shares with his dad that he doesn't share with me, which is totally fine.” Haley, an adolescent, also talked about differing roles for fathers depending on the adolescent's gender, “I think if there's a boy talking about that, then the father would play a lot more role than their mother.”

3.1.2 Between family analysis: what fathers want adolescents to understand

The theme What fathers want adolescents to understand addresses key messages fathers want to pass on to adolescents about sex and relationships. This theme included two subthemes: healthy and unhealthy relationships and sexual risk. The subtheme of healthy and unhealthy relationships addresses fathers' messages to adolescents related to taking care of their social and emotional health in relationships, treating people with respect, and resisting peer pressure. These messages from fathers were described by fathers (n = 10), mothers (n = 8), and adolescents (n = 10), with a similar focus between groups. For example, Jones described his messages to his son, “to experience different things, and not get locked down to somebody. There's gonna be growing relationship changes throughout your life, so don't take anything like it's the end of the world like, ‘Oh so-and-so doesn't like me.”' A mother, Joy, talked about her husband's message to her adolescent related to his race, “I think that as a darker man, he's concerned about [adolescent's name]'s self-esteem in how he makes his dating choices, coming from that worldview. He says ‘You're out here to be yourself. So if someone, you know, is displeased with your physical appearance, your financial contribution, your conversation, anything, then it just means that you're not a good match.”' An adolescent, Stephen, shared what message he thinks his father wants him to know, “always being respectful. I think the way my dad treats my mom like that. I have a lot of sisters and so there's that too, like just the way he's taught me to treat my sisters, just treat them like I'll never hit a woman, never– Like almost kind of just put her first and make sure that like everything is good with her.”

The subtheme of sexual risk addresses fathers' messages to adolescents related to reducing sexual risk behavior by avoiding STIs and adolescent pregnancy, often focused on thinking through consequences of sexual decisions. These messages were primarily described by fathers (n = 11) and adolescents (n = 10), but less by mothers (n = 3). For example, one father, Mickey shared his message to his son, “‘you come to me and I will show you how to properly put on a condom. I don't care if anybody promises you that they're on some type of pill or IUD or shot or whatnot or some type of birth control.' He needs to protect himself at all times.” An adolescent Heather, talked about message from her father, “Be very careful in what you do and who you trust yourself with, because a family member has an adolescent pregnancy and she's struggling right now. So it's just kind of like, ‘Her life doesn't seem very easy. Do you want that for yourself?”' Mothers who raised this topic described similar messages from fathers to their adolescents. Wendy shared her husband's focus, “with his family, there are several young people who have had children at an early age so he says that he does not want that to happen with his children.”

3.1.3 Between family analysis: role of adolescent gender in talk about sex

Almost all participants talked about similarities and differences in how adolescents' gender shaped fathers' engagement with their sons and daughters related to sex and relationships. The theme, Role of adolescent gender in talk about sex, was discussed by most fathers (n = 14), all mothers (n = 15) and many adolescents (n = 11). Many fathers, mothers, and adolescents discussed differences in how fathers approached talk with their daughters compared to their sons about sex and relationships, often focusing on fathers' greater comfort talking with sons than daughters about sex and relationships and their emphasis with their daughters on protecting themselves in relationships. A father, Roberto, talked about how it would be easier for him to talk with a son than a daughter about sex and relationships, “I think I would have the courage, because we would have the same sex. I would have the courage to speak…tell him about our body, right? Our organs–what are they for. And about having a relationship, about masturbation–the dangers that exist with doing it with anyone, right? I would feel more comfortable because we are both boys.” Olivia, an adolescent, also expressed her belief that her father would be more at ease talking with a son than daughter about sexual issues, “He would probably have a more casual approach and be more willing to share his past experiences just because he feels like it would probably be easier for him to relate to a son rather than a daughter.” Beth, a mother, provides an example of how her husband focused more on their daughters' safety than that of their sons, “Making sure that she takes care of herself and is always safe and always makes sure that she watches out for herself with guys because not every guy can be trusted, unfortunately.” However, several fathers highlighted ways in which their messages about sex and relationships were (or would be) similar for sons and daughters, although this was rarely discussed by mothers and adolescents. For example, one father, Al, talked about how he applies the same messages to his sons and daughters, “Realistically, the message is the same, male, or female, in my opinion. You need to be safe. You need to understand how enjoyable it can be, and you need to know about consent, and you need to know about any potential dangers with it and all that. But there's no difference, in my opinion, my boys are gonna have the exact same rules.”

3.2 Within family analysis

In this section, we investigated the consistency of responses within each family (triangulation between a father, mother, and daughter/son in the same family) for each main theme.

3.2.1 Within family analysis: father roles in talk about sex and relationships

In most participating families (n = 10, 67%), fathers, mothers, and adolescents consistently described the importance of Father roles in talk about sex and relationships, although their specific ideas about what fathers' role should be varied among family members. For example, Al described how he views a father's role, “Whether that's a bad relationship, whether that's just jumping into sex too soon. Whether that's having a baby when you weren't prepared to have a baby. Whether that's, you know, getting, uh, a vaccination for HPV, whatever it might be. I feel like a dad's responsibility then is to teach your kids all of these things.” Al's wife Elena also emphasized the importance of a father's role, but focused on different factors, “I think that the most important thing that a father can do is to model healthy relationships for their children regardless of the gender…secondly, I think that both a father and a mother should be willing to engage in open conversation with their children about sex and relationships.” Lastly, their son, Aaron, shared, “I think it should be someone's sort of duty to inform their kids but not like overstep or make their kid uncomfortable…A lot of times, especially in America, and there's like the stereotypical like gender role. Like the father should go out and work, and the mother should stay home with the kids. But I don't really subscribe to that. So I think that the parents should really share the responsibility as they see fit.” In all but one of these families (n = 9), participants described fathers as highly involved in family talk with the adolescent about sex and relationships. For example, Derek2 shared, “I look at myself as somebody who could give her advice on the opposite side. I think I know guys pretty well and I try to give her as much insight as I can. She's going to make her own decisions and act only hope that I've raised her to a point where those decisions will be good.” In the family which described low father engagement, the mother, Roxana, described a wish for the father's engagement, but a lack of actual talk with their adolescent daughter, “I can't imagine him talking about that.”

In some families (n = 5, 33%), there was disagreement between family members about whether fathers should play an important role in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships. In Jones' family, he and his wife described the mother's role as primary in talk about sex and relationships, while his daughter identified a key role for fathers. Jones explained, “I don't know why that is, but it's kind of done that way since they've kind of gotten to the puberty age. It's always been, you know, mom takes us to the doctor, mom takes us to the gynecologist. You know what I mean? You know, my wife is probably having a more active role in it.” His wife Nicole agreed, “The female in the relationship takes the lead, just because I feel like [adolescent's name] would be more comfortable talking to me.” In contrast, his daughter Olivia discussed how she sees a father's role, “Be there if you have any questions or kind of just be in your corner and like be able to support you and your decisions while, um, like warning you of potential dangers or like red flags that they might see…I think that the father's job is usually to be like the protector of their children and to caution them from making the same mistakes that they might've made when they were younger.” In families where there was disagreement about whether fathers should play a meaningful role in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships, at least one family member described the father in the family as disengaged from talk with the adolescent about sex and relationships. As with Jones' description of his lack of engagement in talk with his adolescent about sex, Omar talked about how his ideas for a father's role do not match his own interactions with his son, “In my case, well, it's been a bit difficult, because no–we haven't had that confidence and we haven't really had those talks that we should have as a father and son.”

3.2.2 Within family analysis: what fathers want adolescents to understand

In most families (n = 9) there was agreement between fathers, mothers, and adolescents about What fathers want adolescents to understand about sex and relationships, with a frequent focus on healthy relationships. For example, everyone in Pedro's family described Pedro's messages about the importance of being in a good relationship. Pedro shared key messages he wants his son to know, “to be careful, to make sure who he is dating, and when that time comes just to make sure that you know, it's a good person to him.” Pedro's wife Freida emphasized overlap with Pedro in what they want to share with their son, “I think the ideas are pretty similar. I feel like we have the same interest for our kids. We want them to be in a happy relationship.” Their son Zaro talked about what he feels his father wants to convey, “He would tell me about how I can make the relationship stronger, how I know that person's the right person for me. I think that's how he's gonna help me.”

Among families where there was less agreement about fathers' messages (n = 6), there was often agreement between the father and adolescent about what the fathers wanted to convey, while mothers either expressed that they were unsure what messages fathers wanted to share or felt fathers did not have messages about sex and relationships to share with adolescents. For example, Derek and his daughter both spoke about his message about the importance of healthy relationships. Derek shared his message to his daughter about what he wants her to experience in a relationship, “to be in a relationship where she felt confident and she, in my opinion, would be in charge. She would call her own shots…empowered is the word I was looking for.” His daughter Lucy described how she sees her fathers' ideas about what he wants for her in relationships, “Something safe, safe, no abusers, they're supposed to love each other, be in a healthy relationship, maybe have a family.” In contrast, Lucy's mother Beth shared that she was unsure what messages Derek wanted to share with Lucy, “I don't know that we really have talked about it. I guess we've had some assumptions like that we're probably on the same page, but no, we haven't really discussed it.”

3.2.3 Within family analysis: role of adolescent gender in talk about sex

In most families (n = 10), there was agreement between fathers, mothers, and adolescents regarding whether fathers' messages about sex and relationships differed based on their adolescent's gender (Role of adolescent gender in talk about sex). Nine out of the 10 families who were in agreement described similar explanations for gender similarities and differences in fathers' talk. In these cases, all family members described a focus on how fathers talked (or would talk) differently with their sons than daughters based on girls perceived physical and emotional vulnerability and need for protection. For example, Felix described how he talks with his daughters, “I talked to them about what to expect from a male, and then what are some red flags to look for in guys based upon even their home life or the way they talk to you, the way they treat you.” His wife Joy emphasized Felix's messages to their daughters compared to sons about self-protection, “He would give more information about how to protect yourself, making sure they were self-sufficient.” Their son Jack described why his father's conversations would be different with his daughters, “A boy is safer emotionally, in a relationship.”

However, in seven out of the 10 families, even when there was agreement that fathers' messages differ based on adolescent gender, there was inconsistency between family members about how messages were similar or different. For example, in Cesar's family, all family members identified differences in how Cesar would talk with his adolescents based on their gender. However, Cesar and his son focused on Cesar's lack of comfort talking with a daughter about sex and relationships, while Cesar's wife focused on how he would restrict his daughters' behaviors related to sex. Cesar shared, “I get nervous. I think that if he [my son] were a girl, I would be worse off… imagine talking to a woman like that and my daughter. No, man.” Similarly, his son Andrés commented, “If I was a girl, then he wouldn't feel as comfortable as he feels with a boy.” In contrast, Cesar's wife Wendy shared, “We talked about it and I say, ‘And if he was a girl, would you buy him the condoms too?' He says, ‘No. What? Are you crazy?'… I think he would keep her locked up.”

Some families (n = 5) showed less agreement regarding whether fathers' messages differed based on adolescents' gender, although there were not consistent patterns across family members. In one family, the father (Al) described his messages as consistent across adolescent gender, while his wife and their adolescent described differences in his messages. Al shared, “Realistically, the message is the same, male or female, in my opinion. You need to be safe. You need to understand how enjoyable it can be, you need to know about consent, and you need to know about any potential dangers with it and all that.” His wife Elena shared, “(Al) would talk to our children, regardless of what gender they are, about the importance of consent. He would probably stress that more strongly in cisgendered male child than he would with a female child, because both of us feel very strongly about rape and getting consent.” Their adolescent Aaron commented, “He's definitely preached to be safe, that's his number one thing. ‘Be safe, make sure that if you ever feel uncomfortable with somebody, you get out right then.' And that's just because he's seen me as a female and it's just a lot of dangerous stuff out there.”

4 Discussion

This study is unique in its triangulation of multiple family perspectives on father-adolescent talk about sex and relationships and its use of both between- and within-family analyses. Communication about sex is often perceived differently across family members, with inconsistencies in whether family members report having a conversation about a sexual topic, typically with adolescents less likely to report a conversation than parents (Atienzo et al., 2015; Scull et al., 2022), although little research compares variation in mothers' and fathers' perspectives. The use of triangulation helps to understand whether and how family members view conversations in similar and different ways. Comparing perspectives across groups (between-family analyses) can provide insight into common patterns of how family roles (father, mother, adolescent) shape perspectives on fathers' communication about sex and relationships. Investigating family members' perspectives in a single family (within-family analysis) can both confirm and add nuance to common patterns, to understand how family perspectives may differ. It may also give voice to less common patterns, which show how families can diverge in their ways of understanding fathers' roles in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships.

Both analyses suggest a high level of agreement about fathers' roles in family talk about sex. The findings showed shared recognition of the importance of fathers' roles in family talk about sex. This investment in fathers' roles in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships contrasts with low levels of fathers' engagement in talk with adolescents about sex identified in prior research (Wright, 2009; Sneed et al., 2013; Grossman et al., 2021) and suggests the need to overcome barriers that may prevent fathers from talking with their adolescents even if they believe their active engagement is important (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019; Grossman et al., 2022). Between-family analyses show agreement across father, mothers, and adolescents on fathers' roles as emotional supports and open communicators with their adolescents about sex and relationships in addition to educators and advisors. This finding is interesting as it diverges from traditional fatherhood roles, while reflecting roles more traditionally associated with how mothers support their adolescents. Families' focus on fathers serving as both advisors and supports for adolescents' health shows the need for fathers to have access to resources to support these roles, which can be challenging since most educational resources on parent-adolescent talk about sex are geared toward mothers (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012). Between-group findings also show a disconnect between groups, with only mothers identifying role modeling as an important aspect of fathers' engagement with their adolescents. It is interesting that fathers and adolescents did not identify this as a paternal role, which has been described by adolescents and fathers in prior research (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019; Grossman et al., 2022). Mothers may be in a unique position to observe and identify when fathers lead by example and may see role modeling as a way fathers can contribute even if they are not directly involved in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships.

Within-family analyses confirmed a high level of family agreement on the importance of fathers' roles in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships. It also provided insight into the minority of families with inconsistent views of fathers' roles, such as when some family members believe fathers play a key role in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships, while others see mothers as a more central support. The view of mothers as the primary family sex educators for their adolescents is well-documented (Flores and Barroso, 2017), but disparate viewpoints within families about the centrality of a father's role have not been previously explored.

Fathers' focus on healthy relationships emerged as a key message in both analyses and has been identified as a key message from both mothers and fathers in prior studies (Kapungu et al., 2010; Sneed et al., 2013). Between-groups analyses also found that fathers and adolescents, but rarely mothers, viewed sexual risk as a focus of fathers' messages to adolescents. Talking with adolescents about sexual behavior is taboo in many families due to beliefs and traditions such as those related to culture, religion, and gender (Padilla-Walker et al., 2020), which may lead to a lack of communication between fathers and mothers about this topic. Further, since mothers may not be involved in father- conversations about sexual behavior, such as when fathers take the lead in talking with sons about condom use (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019), mothers may be unaware when these conversations occur.

Within-family analyses provide additional data on the disconnect between mothers' and fathers' perspectives. In families who disagreed about fathers' messages to adolescents about sex and relationships, fathers and adolescents tended to express similar views, while mothers indicated that they either lacked information about father-adolescent communication or expressed that there was no father-adolescent communication about sexual issues. Traditional views that mothers play the primary family role in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships (Flores and Barroso, 2017) may lead mothers to assume that fathers are not involved in talk with their adolescent children about these topics, which may contribute to low communication between mothers and fathers about fathers' talk with their adolescent children about sex and relationships, although research is needed to explore this issue. Since parental talk with adolescents about sex can protect adolescents from sexual risk behaviors (Widman et al., 2016; Scull et al., 2022), these findings suggest the need for parents to talk with each other about who will share messages with adolescents about sex and agree on shared messages about this topic.

Analyses also identified gender as a key factor in fathers' roles and communication with adolescents about sex and relationships, consistent with prior research (Widman et al., 2016; Flores and Barroso, 2017; Evans et al., 2020). Between-group analyses echoed findings from prior research on gender differences in how fathers talk with their sons compared to their daughters about sex and relationships (Wright, 2009; Flores and Barroso, 2017; Evans et al., 2020). Findings showed fathers' greater comfort talking with sons than daughters, often emphasizing how a match in parent and adolescent gender between father and son can facilitate comfort and communication, consistent with prior research (Wyckoff et al., 2008; Grossman et al., 2024). Our findings also were consistent with a parents' traditional gender socialization focus on daughters' vulnerability and need for protection (Flores and Barroso, 2017; Evans et al., 2020). While some studies suggest that fathers are sharing less gender-stereotyping messages with their adolescents, such as talking with sons as well as daughters about consent (Grossman et al., 2022), research suggests many parents continue to pass on gender stereotyping messages to their adolescents, such as a focus for girls on maintaining virginity and resisting boys' advances (Flores and Barroso, 2017; Evans et al., 2020). These findings affirm the value of fathers' engagement with their adolescents in talk about sex and relationships, including their daughters, but also identified fathers' discomfort talking with their daughters about sexual issues. These findings highlight the importance of supports for fathers to learn to talk in thoughtful ways with their adolescent daughters about sex and relationships in order to support adolescents' health.

Within-family analysis showed that even with a common recognition of differences across adolescent gender, members within a family expressed different views on how adolescents' gender impacts father-adolescent communication. For example, some family members emphasized comfort while others focused on the content of messages. Further, some families did not agree on whether messages were similar or different across adolescent gender. While much research investigates patterns of gender differences in parent-adolescent talk about sex (Widman et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2020), this paper's findings highlight the complexities of investigating this issue, which encompasses both adolescent and parent gender, the gender match between parent and adolescent, and how gender shapes the content and process of talk with adolescents about sex.

While this study does not assess the role of teens' sexual identities in father-teen talk about sex and relationships, prior research suggests that fathers are often uncomfortable talking with teens about sexual identity and that teens, rather than fathers, often bring up this topic in father-teen conversations (Grossman et al., 2024). Given the current study's findings that families see fathers as key supports for teens' sexual health, skills and resources for father are needed to promote healthy father-teen conversations about sexual identity. This is especially important as parents' bias against sexual minorities can be harmful to LGBTQ+ teens (Hubachek et al., 2023).

A strength of this study is its racial and ethnic diversity. Given that almost half of this sample identified as Latino/a, the study's findings may be more reflective of these cultural groups than families from other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Future research would benefit from a comparison of racial/ethnic groups, which was not feasible given the small sample size in this study. The limitations of a small sample size are balanced by this being the first study to triangulate fathers, mothers, and adolescents' perspectives on father-adolescent communication about sex and relationships. The use of small samples is justified in cases such as hard to reach samples (Etz and Arroyo, 2015). This sample size is also consistent with other peer-reviewed qualitative papers, particularly those which include dyadic comparisons (e.g., Grossman et al., 2022; Saini et al., 2023). The gender-based findings from this study and prior research show the need for more studies which investigate the role of gender in father-adolescent talk about sex and relationships and how it influences the effects of this communication on adolescents' sexual health and behavior. This study sample includes families which include a mother and father and almost all families live in the same household. In addition, all fathers identified as heterosexual, although we do not have this information for mothers and adolescents. Research is needed to explore these processes among diverse families. For example, given the number of fathers who do not live with their adolescents, there is a need for future research to explore father-adolescent communication for non-residential fathers and their adolescents, a nascent area of research exploration (e.g., Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2023). Families who volunteered for this project are likely to be more engaged in family talk about sex and relationships than most families. Research is needed on more representative families who are less engaged in family talk about sex and relationships, which is a challenge given lows levels of fathers' participation in social science research (Davison et al., 2016). This study focused primarily on family members' attitudes about father-adolescent communication about sex and relationships. Studies which use dyadic approaches to compare reports of father-adolescent talk from fathers and adolescents from the same family would provide opportunities to explore whether fathers and adolescents follow similar patterns as mothers and adolescents in the congruence of perceived communication. Future studies that compare family members' perceptions of both mother-adolescent and father-adolescent communication could provide a more complete picture of family systems of talk about sex and relationships. This study was also conducted during the COVID pandemic, which may have shaped families' perceptions of father-adolescent communication.

This is the first study to use triangulation analysis to investigate multiple perspectives on fathers' roles and messages to adolescents regarding sex and relationships. Fathers' talk with adolescents about sex can protect adolescents from sexual risk behaviors (Wright, 2009; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012), yet fathers talk with adolescents about sex less frequently than mothers and many fathers do not talk at all with adolescents about sexual topics (Sneed et al., 2013; Grossman et al., 2021). Gaining perspectives from multiple family members can help to identify potential supports (e.g., family investment in father-adolescent talk about sex) or barriers (e.g., lack of shared understanding of father roles and messages) to fathers' involvement in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships. These findings are encouraging based on the shared recognition that fathers play an important role in socializing their adolescents about sex and relationships. Findings that adolescents and mothers support fathers' involvement in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships can help to reduce fathers' uncertainties about whether they can play a role in talk with adolescents about sex and relationships. The disconnects identified in this study between mothers' and fathers' perceptions of fathers' roles and messages suggest that even in families who support father-adolescent communication, parents may not talk to each other about this issue. High school is a key period for adolescents' development of relationships and sexual behavior (Giordano et al., 2006), which makes it a meaningful time for parents to coordinate and implement talk with their adolescents about sex and relationships. These findings suggest the need to explore family systems of communication about sex and relationships, such as whether mothers and fathers talk with each other about communication with their children about sex and relationships and whether and how their messages express similar and different values and expectations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Brandeis University Human Research Protection Program. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AD: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study received funding from Grant 1R21HD100807-01A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the families who shared their experiences and perspectives for this project. We thank Equimundo and Dr. Johnson at The National Partnership for Community Leadership for their family outreach.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alcalde, M. C., and Quelopana, A. M. (2013). Latin American immigrant women and intergenerational sex education. Sex Educ. 13, 291–304. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2012.737775

Aronowitz, T., and Agbeshie, E. (2012). Nature of communication: voices of 11–14 year old African-American girls and their mothers in regard to talking about sex. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 35, 75–89.

Ashcraft, A. M., and Murray, P. J. (2017). Talking to parents about adolescent sexuality. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 64, 305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.11.002

Atienzo, E. E., Ortiz-Panozo, E., and Campero, L. (2015). Congruence in reported frequency of parent-adolescent sexual health communication: a study from Mexico. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 27, 275–283. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2014-0025

Beckett, M. K., Elliott, M. N., Martino, S., Kanouse, D. E., Corona, R., Klein, D. J., et al. (2010). Timing of parent and child communication about sexuality relative to children's sexual behaviors. Pediatrics 125, 34–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0806

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021) 2021 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/results.htm (accessed 10 July 2023).

Clawson, C. L., and Reese-Weber, M. (2003). The amount and timing of parent-adolescent sexual communication as predictors of late adolescent sexual risk-taking behaviors. J. Sex Res. 40, 256–265. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552190

Davison, K. K., Gicevic, S., Aftosmes-Tobio, A., Ganter, C., Simon, C. L., Newlan, S., et al. (2016). Fathers' representation in observational studies on parenting and childhood obesity: A systematic review and content analysis. Am. J. Public Health 106, e14–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303391a

Etz, K. E., and Arroyo, J. A. (2015). Small sample research: considerations beyond statistical power. Prevent. Sci. 16, 1033–1036. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0585-4

Evans, R., Widman, L., Kamke, K., and Stewart, J. L. (2020). Gender differences in parents' communication with their adolescent children about sexual risk and sex-positive topics. J. Sex Res. 57, 177–188. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2019.1661345

Flores, D., and Barroso, J. (2017). 21st century parent–child sex communication in the United States: a process review. J. Sex Res. 54, 532–548. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1267693

Giordano, P. C., Manning, W. D., and Longmore, M. A. (2006). Adolescent Romantic Relationships: An Emerging Portrait of Their Nature and Developmental Significance. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Grossman, J. M., DeSouza, L. M., Richer, A. M., and Lynch, A. D. (2021). Father-teen talks about sex and teens' sexual health: the role of direct and indirect communication. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:9760. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189760

Grossman, J. M., Richer, A. M., DeSouza, L. M., Brinkhaus, J., and Ragonese, C. (2024). The “what” and “how” of father-teen talks about sex and relationships. J. Fam. Psychol. 38, 260–269. doi: 10.1037/fam0001176

Grossman, J. M., Richer, A. M., Hernandez, B. F., and Markham, C. M. (2022). Moving from needs assessment to intervention: fathers' perspectives on their needs and support for talk with teens about sex. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:3315. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063315

Grossman, J. M., Sarwar, P. F., Richer, A. M., and Erkut, S. (2017). “We talked about sex.” “No, we didn't”: exploring adolescent and parent agreement about sexuality communication. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 12, 343357. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2017.1372829

Guilamo-Ramos, V., Bouris, A., Lee, J., McCarthy, K., Michael, S. L., Pitt-Barnes, S., et al. (2012). Paternal influences on adolescent sexual risk behaviors: A structured literature review. Pediatrics 130, e1313–e1325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2066

Guilamo-Ramos, V., Jaccard, J., Dittus, P., Bouris, A., Holloway, I., and Casillas, E. (2007). Adolescent expectancies, parent-adolescent communication and intentions to have sexual intercourse among inner-city, middle school youth. Ann. Behav. Med. 34, 56–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02879921

Guilamo-Ramos, V., Jaccard, J., Dittus, P., and Bouris, A. M. (2006). Parental expertise, trustworthiness, and accessibility: parent-adolescent communication and adolescent risk behavior. J. Marri. Family. 68, 1229–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00325.x

Guilamo-Ramos, V., Thimm-Kaiser, M., and Benzekri, A. (2023). Paternal communication and sexual health clinic visits among latino and black adolescent males with resident and nonresident fathers. J. Adolesc. Health. 73, 567-573. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.04.024

Guilamo-Ramos, V., Thimm-Kaiser, M., Benzekri, A., Rodriguez, C., Fuller, T. R., Warner, L., et al. (2019). Father-son communication about consistent and correct condom use. Pediatrics. 143, 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1609

Hsieh, H.-F., and Shannon, S. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Hubachek, S. Q., Clark, K. A., Pachankis, J. E., and Dougherty, L. R. (2023). Explicit and implicit bias among parents of sexual and gender minority youth. J. Family Psychol. 37, 203–214. doi: 10.1037/fam0001037

Hutchinson, M. K., and Montgomery, A. J. (2007). Parent communication and sexual risk among African Americans. West. J. Nurs. Res. 29, 691–707. doi: 10.1177/0193945906297374

Kachingwe, O. N., Reynolds, K. D., Blakely, L., and Aparicio, E. M. (2023). Sexual health communication among Black father–daughter dyads: a grounded theory study. J. Family Psychol. 37, 464–474. doi: 10.1037/fam0001058

Kapungu, C. T., Baptiste, D., Holmbeck, G., McBride, C., Robinson-Brown, M., Sturdivant, A., et al. (2010). Beyond the 'birds and the bees': Gender differences in sex- related communication among urban African-American adolescents. Fam. Process 49, 251-264. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01321.x

Kim, S., Jemmott, J. B., Icard, L. D., Zhang, J., and Jemmott, L. S. (2021). South African fathers involvement and their adolescents' sexual risk behavior and alcohol consumption. AIDS Behav. 25, 2793–2800. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03323-8

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. Available online at: http://0search.ebscohost.com.luna.wellesley.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&An=~199597407-000&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Murphy-Erby, Y., Stauss, K., Boyas, J., and Bivens, V. (2011). Voices of Latino parents and adolescents: Tailored strategies for parent–child communication related to sex. J. Child. Poverty 17, 125–138. doi: 10.1080/10796126.2011.531250

Nielsen, S. K., Latty, C. R., and Angera, J. J. (2013). Factors that contribute to fathers being perceived as good or poor sexuality educators for their daughters. Fathering 11, 52–70. doi: 10.3149/fth.1101.52

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Rogers, A. A., and McLean, R. D. (2020). Is there more than one way to talk about sex? A longitudinal growth mixture model of parent–adolescent sex communication. J. Adolesc. Health 67, 851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.04.031

Randolph, S. D., Coakley, T., Shears, J., and Thorpe, R. J. Jr. (2017). African-American fathers' perspectives on facilitators and barriers to father–son sexual health communication. Res. Nurs. Health 40, 229–236. doi: 10.1002/nur.21789

Saini, P., Hunt, A., Kirkby, J., Chopra, J., and Ashworth, E. (2023). A qualitative dyadic approach to explore the experiences and perceived impact of COVID-19 restrictions among adolescents and their parents. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 11, 2173601. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2023.2173601

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., and Altenburger, L. E. (2019). “Parental gatekeeping,” in Handbook of Parenting (London: Routledge), 167–198.

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Wang, J., Yang, J., Kim, M., Zhang, Y., and Yoon, S. H. (2023). Patterns of coparenting and young children's social-emotional adjustment in low-income families. Child Dev. 94, 874–888. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13904

Scull, T. M., Carl, A. E., Keefe, E. M., and Malik, C. V. (2022). Exploring parent-gender differences in parent and adolescent reports of the frequency, quality, and content of their sexual health communication. J. Sex Res. 59, 122–134. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2021.1936439

Shtarkshall, R. A., Santelli, J. S., and Hirsch, J. S. (2007). Sex education and sexual socialization: roles for educators and parents. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 39, 116-119. doi: 10.1363/3911607

Sneed, C. D., Somoza, C. G., Jones, T., and Alfaro, S. (2013). Topics discussed with mothers and fathers for parent–child sex communication among African-American adolescents. Sex Educ. 13, 450–458. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2012.757548

Sneed, C. D., Tan, H. P., and Meyer, J. C. (2015). The influence of parental communication and perception of peers on adolescent sexual behavior. J. Health Commun. 20, 888–892. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018584

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. Available online at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&An = 1999-02001-000&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Widman, L., Choukas-Bradley, S., Noar, S. M., Nesi, J., and Garrett, K. (2016). Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 170, 52–61. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2731

Wright, P. J. (2009). Father-child sexual communication in the United States: a review and synthesis. J. Fam. Commun. 9, 233–250. doi: 10.1080/15267430903221880

Keywords: reproductive health, adolescent health, father-child relations, family, communication, qualitative, sexual health

Citation: Grossman JM, DiMarco AJ and Richer AM (2024) Triangulation of family perspectives on father-adolescent talk about sex and relationships. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2:1264934. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2024.1264934

Received: 21 July 2023; Accepted: 27 March 2024;

Published: 29 August 2024.

Edited by:

Jordan Ashton Booker, University of Missouri, United StatesReviewed by:

Chelsie Temmen, University of Louisville, United StatesMatthew Nielson, New York University Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Naomi Andrews, Brock University, Canada

Copyright © 2024 Grossman, DiMarco and Richer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer M. Grossman, amdyb3NzbWFAd2VsbGVzbGV5LmVkdQ==

Jennifer M. Grossman

Jennifer M. Grossman Audrey J. DiMarco

Audrey J. DiMarco