- Restorative Dental Sciences College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Objectives: Despite advances in endodontic treatment procedures, root canal treatment is still associated with anxiety and fear. This may cause care avoidance and subsequent oral complications due to untreated endodontic infections. Anxiety and fear levels in response to non-surgical root canal treatment performed by endodontic residents and endodontists were analyzed.

Methods: A descriptive, cross-sectional survey was conducted among patients visiting the endodontic clinics at the University Dental Hospital. The questions addressed the participant's demographics, previous root canal treatment visits, clinician's level of training, and post-treatment experience.

Results: Demographics play a role in anxiety and dental fear in root canal treatment. Men scored significantly lower in the high-anxiety category than women, and patients treated by endodontic residents expressed lower levels of anxiety. Post-treatment experience of an endodontist or endodontic resident was a significant factor in reducing dental fear and anxiety.

Conclusion: The level of anxiety and fear related to root canal experience of endodontists or endodontic residents is very low. Most of the patients expressed willingness to undergo further root canal treatment to save a tooth.

Introduction

Preoperative fear and anxiety have been identified as distinct emotional states and are a significant problem for patients and dental care providers alike. Together, they can be a significant contributor to refusal of dental treatment and deterioration of oral and dental health (1). By definition, fear and anxiety act as a signal of danger, or threat, to trigger appropriate adaptive responses. Fear is aroused by specific external stimuli, whereas anxiety is a generalized response to an unknown threat or internal conflict (2). Therefore, some patients may feel afraid of dental care because of past experiences, while others may have anxiety related to uncertainty of events to come. According to many ethologists, anxiety may be a more elaborate form of fear (3). Nevertheless, dental anxiety and dental fear are highly correlated (4). Research indicates that dental anxiety is a mental health issue and a public health concern (5).

Despite advances in dentistry, many people still consider root canal treatment a highly unpleasant experience (6). Among dental events, endodontic treatment ranked seventh among procedures that were most fear-arousing (7). A recent public opinion commissioned by the American Association of Endodontists on most common public fears showed that 59% of those sampled were more afraid of undergoing root canal treatment than speaking in public (8).

Despite quadrupling in the number of patients who describe this dental procedure as painless, the most persistent myth about root canal treatment is extreme pain (9, 10). However, ~96% of patients with a history of root canal treatment would be willing to have another root canal treatment if needed (11). Another study illustrated that the pulpectomy procedure was associated with less significant pain than extraction (12).

Patient perceptions of dental care procedures, including anesthetic infiltration, drilling, and rotary instrumentation, could contribute to overall patient anxiety and fear (13, 14). Studies addressing patient's perceptions of anxiety toward endodontic treatment placed endodontic procedures at the top of the list on provoking patient anxiety (15–17). This emotional state can cause a patient to reject endodontic treatment in favor of tooth extraction (18). The percentage of reported dental treatment avoidance related to fear ranges from 5 to 15% in different populations (19, 20). Interestingly, previous endodontic experiences do not increase fear; however, negative hearsay does (6). Carter et al. (21) analyzed endodontic fear in relation to ethnicity and suggested that different ethnicities could adopt different pathways for fear. The most commonly reported pathway for fear and anxiety of endodontic procedures among patients of White, Arab, and African descents is the cognitive conditioning pathway (21). However, findings also show that information that dissipates negative beliefs can reduce dental anxiety and fear (4).

Limited evidence exists to address whether patient or treatment factors might influence anxiety and fear specific to root canal treatment (22). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to better understand dental fear and anxiety associated with endodontic experience specifically, including what factors might change public attitudes toward endodontic treatment. Toward this end, the study questioned patients before and after endodontic treatment to assess their self-reported fear and anxiety levels in search of factors that may either exacerbate or dispel dental fear and anxiety associated with endodontic treatment.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ref. No. E-20-4881), the ethics committee at king Saud University. The participants were patients referred for non-surgical endodontic treatment to the endodontic clinics at the University Dental Hospital-Medical City King Saud University. All the participants were informed of the confidentiality of their responses. Patients were selected if they met the following inclusion criteria: adult patients aged 18 years and older who were referred for non-surgical endodontic treatment. All patients with mental, psychological, or neurogenic disorders, or those taking antidepressants, anxiolytics, sedative medications, or medications related to the conditions mentioned above were excluded. The survey provided detailed information about the purpose of the study and instructions for the participants.

The descriptive cross-sectional survey was developed and sent to be reviewed by a consultant from the American Dental Association (ADA) and generated using Microsoft forms (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, United States). The survey instrument consisted of twenty-eight questions, including a pre-treatment questionnaire adapted from the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) (23) and Dental Fear Survey (DFS) (13) numbers 1–20 and post-treatment questionnaire numbers 21–26 to address post-treatment experience, number of root canal treatments received, most feared dental procedures, and clinician level of training, in addition to demographic information (sex, age, education level, and employment status) numbers 1–4. The questionnaires were provided in two languages, English and Arabic. Both surveys have been used to assess dental anxiety and dental fear, and have been reported as valid and reliable methods in different populations (13, 23–26). The patients were given a hard copy of the survey instrument or the option to scan the barcode to complete the responses electronically. Each question asked the patients to rate their anxiety and fear responses toward root canal treatment using a five-point Likert scale. They marked one of the five responses (that were later assigned numerical values) as: 1, relaxed; 2, a little uneasy; 3, tense; 4, anxious; 5, extremely anxious or 1, Not at all; 2, a little; 3, some-what; 4, much; 5, very much.

Data Analysis

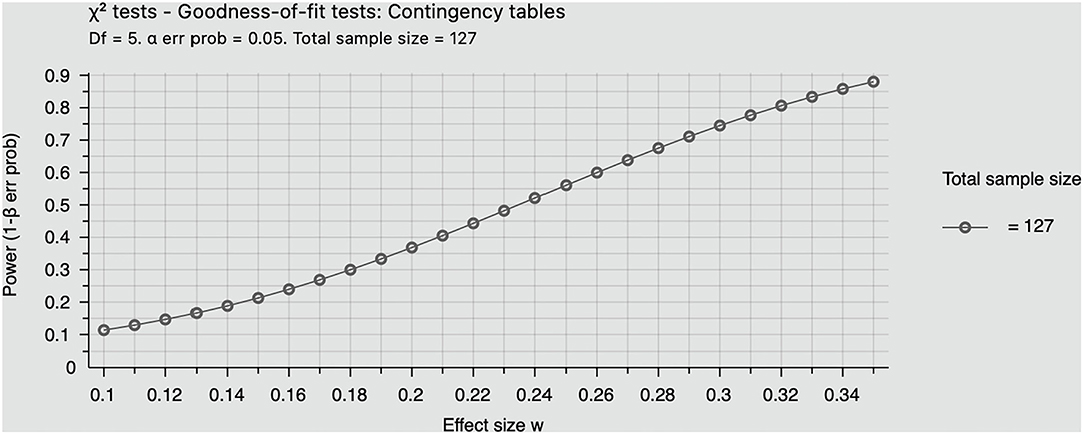

All raw data were transferred from the survey forms to an Excel spreadsheet. Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 25). Data were evaluated by Kruskal Wallis one-way ANOVA to compare patient anxiety and fear levels toward endodontic treatment before and post-treatment, and to calculate the mean scores of each. Anxiety and fear scores were dichotomized into 1–2 (low anxiety) and 3–5 (high anxiety). A chi square test was administered to detect any significant differences between self-reported anxiety and variables of previous root canal experience, levels of clinician training, number of root canal treatments received, post-treatment experiences, and other demographic variables. The role of confounding variables was explored by multivariate regression analysis. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05 and, confidence intervals were determined at 95% for all statistical calculations. A post-hoc power analysis was performed using G *power 3.1.9.4 to calculate the power of the sample size recruited.

Results

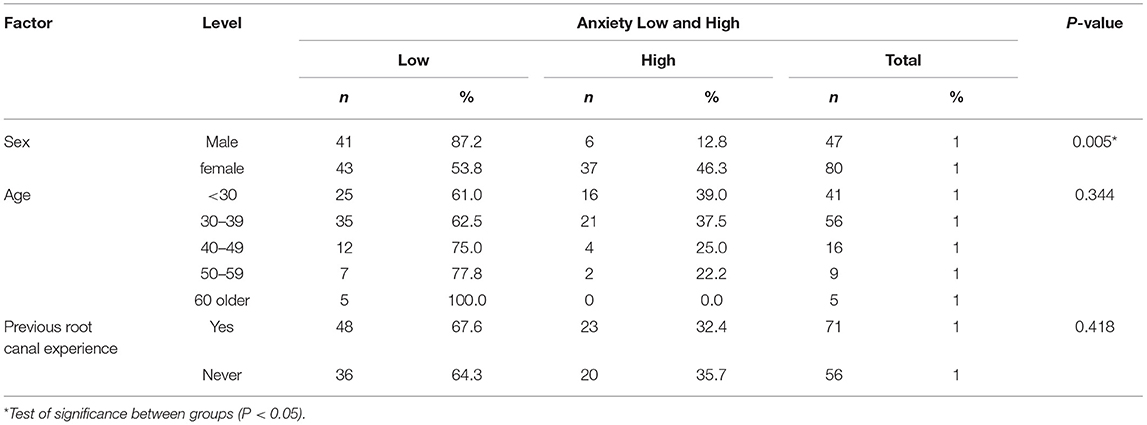

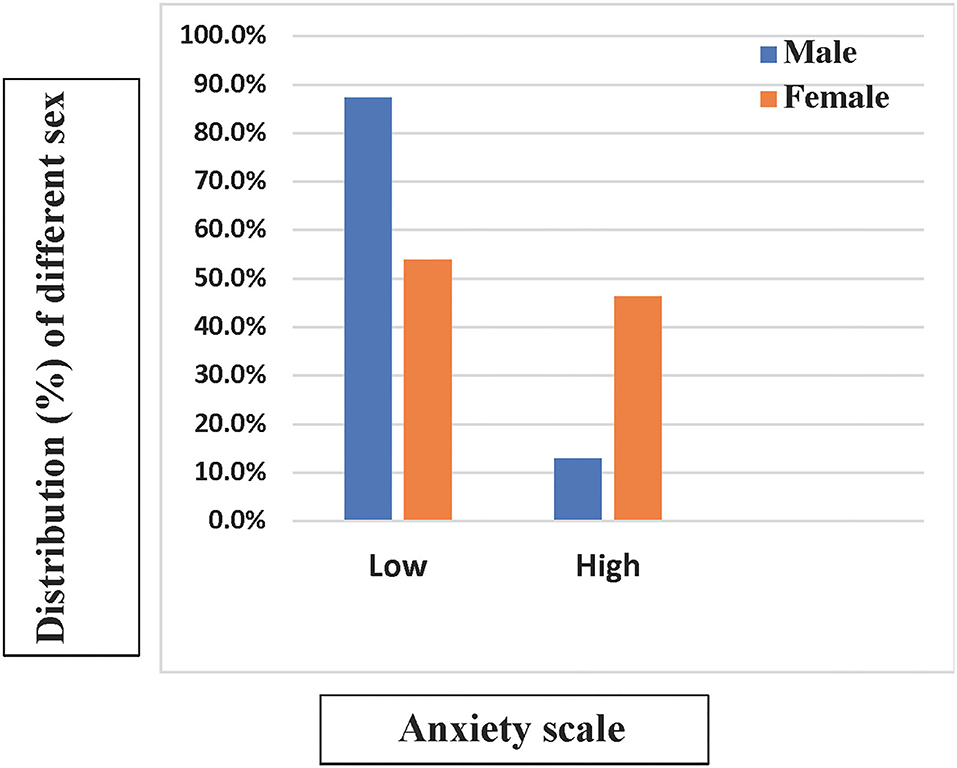

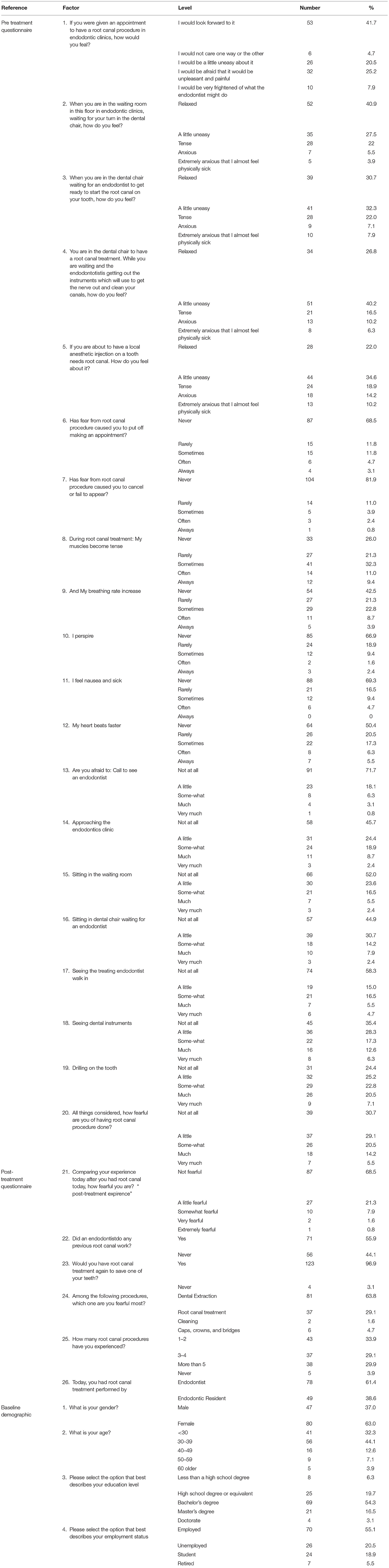

The MDAS and DFS were completed by 127 participants. Responses for baseline demographics, MDAS, and DFS are presented in Table 1. At alpha 0.05 with an effect size of 0.35 and a sample size of 127 participants, the power was equal to 0.88 (Figure 1). This study included 80 women and 47 men; 56 participants were 30–39 years, while 41 were under 30; the rest of the sample were above 40 years old. The different age groups did not show any differences in the level of anxiety (Table 2). However, a significant gender difference was found; the men scored significantly lower in the high anxiety category than the women (Figure 2). The response to the general question (How fearful are you of having a root canal procedure done?) showed that approximately 20% of the participants reported some fear of root canal treatment. Only 12 to ~1% would postpone or cancel their endodontic appointment because of dental fear (Table 1).

Table 1. Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS), Dental Fear Survey (DFS), and baseline demographics questionnaires.

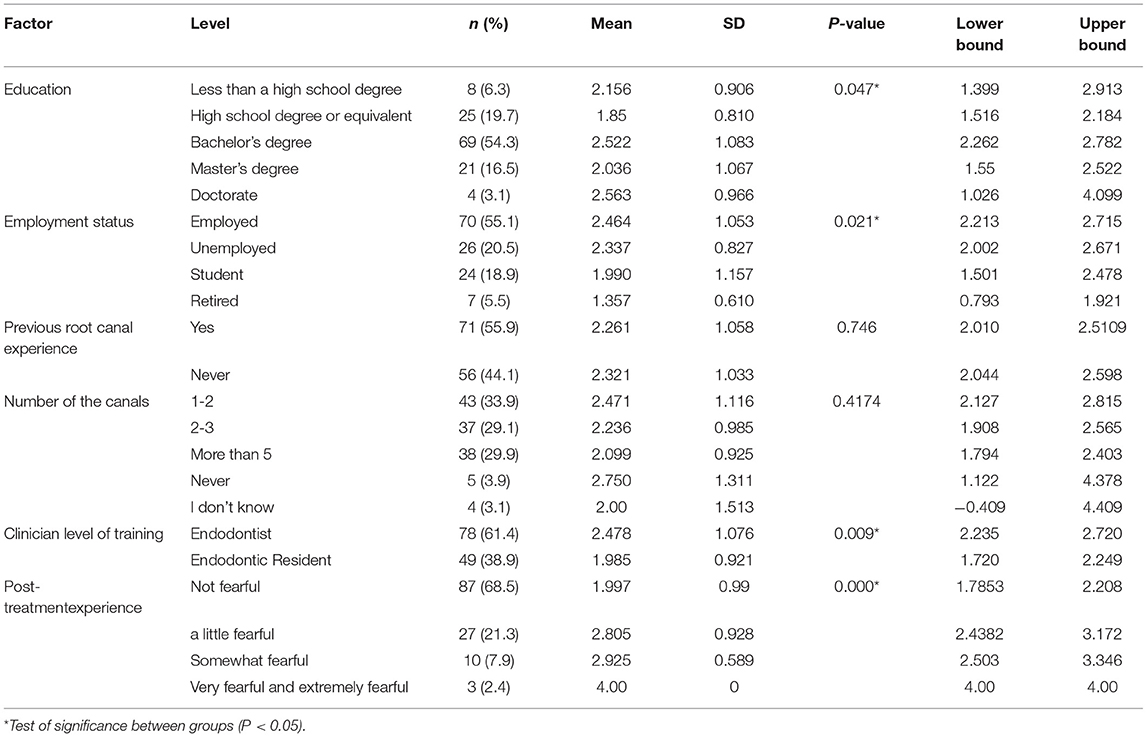

Regarding the patient's level of education and employment status, half of all the respondents had college-level education, 26% completed formal schooling or less, and the rest earned higher degrees. Participants with a bachelor's degree scored significantly higher on anxiety than those who had only completed formal schooling. In contrast, retired participants scored significantly lower on anxiety than employed participants (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean MDAS scores and SD related to education and employment status, number of root canal treatments received, clinician level of training, previous root canal treatment, and post-treatment experience.

When the respondents were asked about the most feared experience among different dental procedures, only 29% were most fearful of root canal treatment. Most of the sample (93%) had experienced at least one root canal treatment. Approximately half of the participants had been treated by an endodontist. Neither the previous root canal experience nor the number of root canal treatments showed a significant difference in anxiety level or fear scores (Tables 3, 4). When we compared those who had a previous root canal experience with patients with no previous treatment experience, we found no significant difference in anxiety levels (Table 2).

Table 4. Mean DFS scores and SD related to number of root canal treatments received, clinician level of training, previous root canal experience, and post-treatment experience.

In our study, most of the patients (61%) underwent root canal treatment performed by endodontists, while the remaining 39% received treatment from an endodontic resident. No significant difference was found in patient fear scores or the number of root canal treatments performed by clinicians (Table 4). However, the patients reported feeling more relaxed, with a significant difference in anxiety mean scores when a resident clinician treated them compared to an endodontist (Tables 2, 3). Overall, most of the patients (96%) were prepared to undergo further root canal treatment to save a tooth. In general, post-treatment experience scored significantly less in the mean scores for dental anxiety and fear, P < 0.05 (Tables 3, 4). Only some of the participants expressed fear.

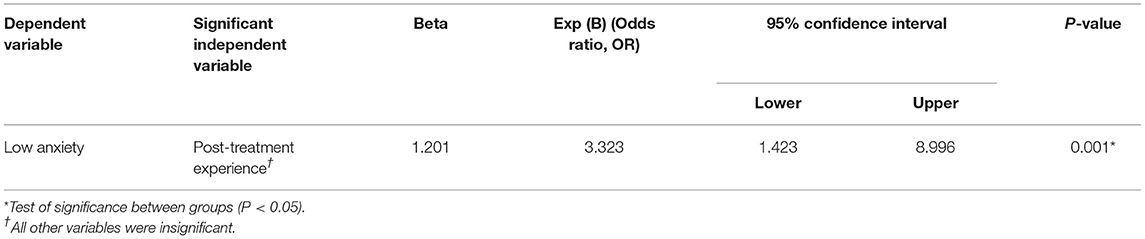

We conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis using self-reported fear as the dependent variable and all other factors (age, sex, education, employment, previous root canal experience, clinician level of training, post-treatment experience, and number of root canal treatments received) as independent variables. This showed a significant relationship between post-treatment experience and self-reported anxiety (low vs. high anxiety; B = 1.34, odds ratio 3.323, p < 0.01) (Table 5).

Table 5. Multivariable linear regression: influence of the independent variables (age, sex, previous root canal experience, clinician level of training, number of root canal treatments received, and post-treatment experience) on low anxiety.

Discussion

Previous data have reported avoidance of dental appointments due to dental fear ranging between 5 and 15% in different populations (19, 20). Our findings support this, because only a small percentage of the participants were likely to postpone or cancel their appointments because of dental fear. Most of our sample expressed willingness to undergo further root canal treatment to save a tooth, indicating their awareness and understanding of the importance of root canal treatment. This study showed that 43 (33%) of the participants fell in the high-anxiety category for self-reported fear and anxiety specifically associated with endodontic treatment, of which 43 were female. Anxiety level among the women was higher than that among the men. This finding is congruent with most dental fear studies (1, 6, 11, 27). The observed differences may be due to women having greater readiness to acknowledge their feelings (28), but others reported real differences in neural circuit and emotional reactivity (29–31). The samples consisted of different age groups, and there was no significant difference between anxiety levels and age. This finding is consistent with other studies that conclude that age is not a significant factor affecting self-reported anxiety (6, 14, 32, 33).

Previous studies have found that education can affect anxiety. Petertz et al. (1) reported that those with higher education levels demonstrated lower levels of anxiety. In contrast, we found that patients with bachelor's or higher degrees reported higher levels of anxiety compared to respondents with less formal education. An informative pathway that assumes subjects learn a negative experience from others also impacts patient's health behavior and attitude toward pain (21). The retired participants in our population expressed less anxiety than the employed participants. The results must be interpreted with caution, as this is a small sample.

Previous experience with endodontic treatment did not result in any differences in anxiety levels. A reason for this may be that half of the sample was treated by endodontists, whose level of training means that patients are less likely to experience dental trauma. These echo the findings of previous studies that avoidance of dental treatment and dental fear come mainly from cognitive conditional pathways that originate from their past dental experiences (21).

An interesting result of this study is that the patients treated by an endodontic resident were more relaxed; they had lower self-reported anxiety compared to those treated by endodontists. All the participants were referred for non-surgical root canal treatment. Regardless of the complexity of the case (behavioral or technical), the patients were treated randomly by endodontists or residents based on clinician availability. This may imply that endodontists usually treat more complex cases (34) or that residents may spend more time educating their patients. However, the participants were not aware of any recommendations and the clinic's policy prohibits patient choice. Moreover, distinction of the fear and anxiety expressed by patients treated by endodontists or residents is not the focus of this study. The results obtained have more focused answers to this question without memory biases related to the clinician's rank. Nevertheless, to date, no studies have analyzed fear and anxiety levels associated with endodontic experience related to differences in clinician seniority.

Most of the participants (96%) were prepared to have root canal treatment again to save a tooth. These results counter the findings of a recent public opinion poll commissioned by the American Association of Endodontists in 2019, in which almost 59% would avoid root canal treatment (8). A noteworthy aspect of our study was the finding that most of the participants did not feel fearful about their post-treatment experience, and this was the only factor associated with low anxiety. A recent systematic review concluded that non-surgical root canal treatment-associated anxiety was moderate and diminished after treatment (22). Given that anxiety often decreases following treatment, more frequent dental visits could also lead to more comfortable and relaxed patients. Another proposal is for endodontic providers to integrate strategic behaviors designed to strengthen patient's inherent coping capacities (13, 35). Contemporary use of instruments, dental microscopes, and pharmacology techniques can encourage patients to relax during dental visits. These increase patient confidence and reduce fears associated with endodontic treatment (35). Good communication and patient education about the treatment process can reverse negative images and fear of root canal treatment, which are still widespread among the public. This study demonstrates that different factors can play a role in dental anxiety and fear specific to endodontic treatment. It appears that root canal experience was a significant factor in reducing anxiety and fear and increased patient's likelihood of accepting future root canal treatment. It is noteworthy that advances in endodontic treatment aid the acceptance of endodontic treatment and reduce the anxiety and fear associated with it.

Within the limitations of this study, we study evaluated the anxiety and dental fear associated with non-surgical root canal treatment before and after the treatment by an endodontist or an endodontic resident in a single population. However, different interpretations by subjects could vary between different populations. Thus, qualitative studies may assist in understanding the factors associated and interplay with anxiety and dental fear of non-surgical root canal treatment.

Conclusion

In general, the level of anxiety and fear related to root canal experience conducted by endodontists or endodontic residents is very low. Most of the patients are prepared to undergo root canal treatment again to save a tooth.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted after approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ref. No. E-20-4881) King Saud University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed significantly and are in agreement with the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2022R478), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors wish to acknowledge Adriana Menezes, Director of Operations at Health Policy Institute (ADA) for her contrtibution by providing feedback on the survey instruments.

References

1. Peretz B, Moshonov J. Dental anxiety among patients undergoing endodontic treatment. J Endod. (1998) 24:435–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(98)80028-9

2. Craig KJ, Brown KJ, Baum A. Environmental factors in the etiology of anxiety. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, editors. Psychopharmacology. New York, NY: Raven Press (1995). p.1325–39.

3. Steimer T. The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2002) 4:231–49. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2002.4.3/tsteimer

4. van Wijk AJ, Hoogstraten J. Reducing fear of pain associated with endodontic therapy. Int Endod J. (2006) 39:384–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01090.x

5. Crego A, Carrillo-Díaz M, Armfield JM, Romero M. From public mental health to community oral health: the impact of dental anxiety and fear on dental status. Front Public Health. (2014) 2:16. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00016

6. Wong M, Lytle WR. A comparison of anxiety levels associated with root canal therapy and oral surgery treatment. J Endod. (1991) 17:461–5. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(07)80138-5

7. Berggren U, Meynert G. Dental fear and avoidance: causes, symptoms, and consequences. J Am Dent Assoc. (1984) 109:247–51. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1984.0328

8. AAE AAoE. Study: This Halloween, People More Scared of Root Canals Than Spiders, Snakes, Sharks Chicago, USA2019. Available online at: https://www.aae.org/specialty/communique/study-this-halloween-people-more-scared-of-root-canals-than-spiders-snakes-sharks/ (accessed October 21, 2019).

9. Klages U, Ulusoy O, Kianifard S, Wehrbein H. Dental trait anxiety and pain sensitivity as predictors of expected and experienced pain in stressful dental procedures. Eur J Oral Sci. (2004) 112:477–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2004.00167.x

10. Watkins CA, Logan HL, Kirchner HL. Anticipated and experienced pain associated with endodontic therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. (2002) 133:45–54. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0020

11. LeClaire AJ, Skidmore AE, Griffin JA, Balaban FS. Endodontic fear survey. J Endod. (1988) 14:560–4. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(88)80091-8

12. Rousseau WH, Clark SJ, Newcomb BE, Walker ED, Eleazer PD, Scheetz JP, et al. comparison of pain levels during pulpectomy, extractions, and restorative procedures. J Endod. (2002) 28:108–10. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200202000-00015

13. Kleinknecht RA, Thorndike RM, McGlynn FD, Harkavy J. Factor analysis of the dental fear survey with cross-validation. J Am Dent Assoc. (1984) 108:59–61. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1984.0193

14. Georgelin-Gurgel M, Diemer F, Nicolas E, Hennequin M. Surgical and nonsurgical endodontic treatment-induced stress. J Endod. (2009) 35:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.09.019

15. Frisk F, Hakeberg M. Socio-economic risk indicators for apical periodontitis. Acta Odontol Scand. (2006) 64:123–8. doi: 10.1080/00016350500469680

16. Udoye CI, Oginni AO, Oginni FO. Dental anxiety among patients undergoing various dental treatments in a Nigerian teaching hospital. J Contemp Dent Pract. (2005) 6:91–8. doi: 10.5005/jcdp-6-2-91

17. Eli I, Bar-Tal Y, Fuss Z, Silberg A. Effect of intended treatment on anxiety and on reaction to electric pulp stimulation in dental patients. J Endod. (1997) 23:694–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80404-9

18. Molin C, Seeman K. Disproportionate dental anxiety. clinical and nosological considerations. Acta Odontol Scand. (1970) 28:197–212. doi: 10.3109/00016357009032028

19. Schwarz E, Birn H. Dental anxiety in Danish and Chinese adults–a cross-cultural perspective. Soc Sci Med. (1995) 41:123–30. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00288-5

20. Nicolas E, Collado V, Faulks D, Bullier B, Hennequin M. A national cross-sectional survey of dental anxiety in the French adult population. BMC Oral Health. (2007) 7:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-12

21. Carter AE, Carter G, Boschen M, AlShwaimi E, George R. Ethnicity and pathways of fear in endodontics. J Endod. (2015) 41:1437–40. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.04.014

22. Khan S, Hamedy R, Lei Y, Ogawa RS, White SN. Anxiety related to nonsurgical root canal treatment: a systematic review. J Endod. (2016) 42:1726–36. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.08.007

23. Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The modified dental anxiety scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. (1995) 12:143–50.

24. Humphris GM, Freeman R, Campbell J, Tuutti H, D'Souza V. Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the modified dental anxiety scale. Int Dent J. (2000) 50:367–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2000.tb00570.x

25. Tunc EP, Firat D, Onur OD, Sar V. Reliability and validity of the modified dental anxiety scale (MDAS) in a Turkish population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. (2005) 33:357–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00229.x

26. Alamri SA, Alshammari SA, Baseer MA, Assery MK, Ingle NA. Validation of Arabic version of the modified dental anxiety scale (MDAS) and kleinknecht's dental fear survey scale (DFS) and combined self-modified version of this two scales as dental fear anxiety scale (DFAS) among 12 to 15 year Saudi school students in Riyadh city. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. (2019) 9:553–8. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_196_19

27. Stabholz A, Peretz B. Dental anxiety among patients prior to different dental treatments. Int Dent J. (1999) 49:90–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.1999.tb00514.x

28. Chaplin TM. Gender and emotion expression: a developmental contextual perspective. Emot Rev. (2015) 7:14–21. doi: 10.1177/1754073914544408

29. Kogler L, Gur RC, Derntl B. Sex differences in cognitive regulation of psychosocial achievement stress: brain and behavior. Hum Brain Mapp. (2015) 36:1028–42. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22683

30. Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Abbs B, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Makris N. Sex differences in stress response circuitry activation dependent on female hormonal cycle. J Neurosci. (2010) 30:431–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3021-09.2010

31. Donner NC, Lowry CA. Sex differences in anxiety and emotional behavior. Pflugers Arch. (2013) 465:601–26. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1271-7

32. Collado V, Nicolas E, Hennequin M. Dental difficulty for adult patients undergoing different dental procedures according to level of dental anxiety. Odontostomatol Trop. (2008) 31:35–42.

33. Akhavan H, Mehrvarzfar P, Sheikholeslami M, Dibaj M, Eslami S. Analysis of anxiety scale and related elements in endodontic patients. Iran Endod J. (2007) 2:29–31. doi: 10.22037/iej.v2i1.353

34. Lazarski MP, Walker WA, Flores CM, Schindler WG, Hargreaves KM. Epidemiological evaluation of the outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment in a large cohort of insured dental patients. J Endod. (2001) 27:791–6. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200112000-00021

Keywords: dental anxiety, dental fear, emotional state, root canal therapy, unpleasant experience

Citation: Alghofaily M and Alsalleeh F (2022) Levels of Anxiety and Fear Related to Non-Surgical Root Canal Treatment Performed by Endodontic Residents and Endodontists. Front. Dent. Med. 3:851834. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2022.851834

Received: 11 January 2022; Accepted: 10 March 2022;

Published: 14 April 2022.

Edited by:

Ikhlas El Karim, Queen's University Belfast, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sivakami Haug, University of Bergen, NorwayAnand Marya, University of Puthisastra, Cambodia

Copyright © 2022 Alghofaily and Alsalleeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maha Alghofaily, bWFsZ2hvZmFpbHlAa3N1LmVkdS5zYQ==

Maha Alghofaily

Maha Alghofaily Fahd Alsalleeh

Fahd Alsalleeh