94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Dent. Med. , 07 October 2021

Sec. Dental Materials

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fdmed.2021.733242

This article is part of the Research Topic Biofunctional Applications of Zirconia in Dental Devices View all 5 articles

Lu Sun1

Lu Sun1 Guang Hong1,2*

Guang Hong1,2*Zirconia-based bioceramic is a potential material for dental implants developed and introduced in dentistry 30 years ago. However, some limitations still exist for zirconia implants caused by several factors, such as manufacturing difficulties, low-temperature degradation (LTD), long-term stability, and clinical experience. Several studies validated that some subtle changes on the zirconia surface might significantly impact its mechanical properties and osseointegration. Thus, attention was paid to the effect of surface modification of zirconia implants. This review generally summarizes the surface modifications of zirconia implants to date classified as physical treatment, chemical treatment, and surface coating, aiming to give an overall perspective based on the current situation. In conclusion, surface modification is an effective and essential method for zirconia implant application. However, before clinical use, we need more knowledge about these modification methods.

Dental implant is a competitive and attractive treatment for replacing missing teeth. It reported that significant increase in dental implants in the United States from 0.7% in 1999 to 2000 to 5.7% in 2015 to 2016, and estimated implant prevalence could be as high as 23% by 2026 (1). The widespread application of dental implants relies on their high survival rate. A recent analysis indicated that a 10-year survival rate of the dental implant was 96.4% (2). Until now, titanium is still the priority choice of dental implant material, which has been used for almost 50 years. The shortcoming of titanium bothers practitioners and patients, such as allergic reactions, titanium deposits, discoloration of the mucosa, or unsatisfied aesthetic outcomes (3, 4). From this standpoint, an innovative type of implant material is urgently needed.

The first trial and the first generation of ceramic implants is aluminum oxide implant, which is proved to be osseointegrated (5). Whereas, the biomechanical properties of aluminum oxide implant, known as fracture toughness, are not satisfying, which consequently caused its unstable long-term survival rates, between 65 to 92% (6). Although aluminum oxide dental implant faces its failure and withdrawal from the market, it still provides a positive concept and direction: a metal-free material should be developed, such as ceramic material. Zirconia is a potential ceramic manufactured as a dental implant abutment since 1995 (7). It was recently thought to be a potential implant material attributed to its superior mechanical properties, outstanding biocompatibility, and ivory color (8, 9). Nevertheless, zirconia materials still need further evolutions on their fracture toughness (10).

It is known that morphology, chemical composition, and roughness are the three main factors affecting newly formed tissue quality and quantity (11). Surface modifications on implants were proved to affect the osseointegration process and mechanical properties, used on titanium implants for over 25 years (12). Thus, particular attention was paid to exploring the surface modification benefits of zirconia. A recent study indicated that surface modification of zirconia might change its interfacial surface characteristics and advance biological performance (13). However, the exploration of surface modification on zirconia is still far from sufficient. This review summarizes zirconia's primary and potential surface modification methods, classified as physical treatment, chemical treatment, and coating, giving an overall perspective of the present situation and providing available clues for future improvement.

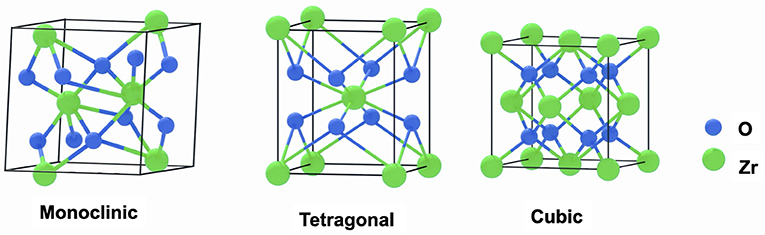

Zirconia crystals are temperature-dependent, consisting of three phases: monoclinic crystal structure, tetragonal crystal structure, and cubic crystal structure (Figure 1). With the temperature increasing, zirconia changes its phase from a monoclinic structure to a tetragonal structure at around 1,170°C; then to a cubic structure at around 2,370°C; finally melts at 2,716°C (14). Phenomena termed Phase Transformation Toughening provides an excellent property to zirconia (15). In general, the tetragonal phase is a metastable state of zirconia at room temperature, which got the micro-cracks process under stress. More concentrated stress will provoke a zirconia phase transformation from tetragonal to monoclinic with a consequent 4% volume expansion (16), finally stopping the micro-cracks propagation, recovering, and strengthening toughness (17).

Figure 1. Structure diagrams of the monoclinic phase crystal, tetragonal phase crystal, and cubic phase crystal of zirconia.

Meanwhile, the phase transformation from tetragonal to monoclinic will accelerate Low-Temperature Degradation (LTD), also known as aging (18). LTD occurs in the presence of humid environments, such as water or body fluid, through a slow surface transformation from a metastable tetragonal phase to a stable monoclinic phase (19). In that case, zirconia will lose its Zr-O-Zr bond, leading to increasing monoclinic content. In addition, the forming micro-cracks in transforming regions make material lose strength (20), finally results in degradation.

For improving the defect of crystalline transformation, researchers find that small amounts of additional elements can stabilize the tetragonal or cubic phase of zirconia, such as yttria, magnesium, or ceria. Currently, yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystalline (Y-TZP) is the most common candidate for zirconia implants (21). Additionally, alumina toughened zirconia (ATZ), zirconia toughened alumina (ZTA), magnesium partially stabilized zirconia (Mg-PSZ), and ceria partially stabilized zirconia/alumina nanocomposite (Ce-TZP/Al2O3) were also reported as potential materials for dental implants (22).

Sandblasting is an approach for obtaining optimal micro-roughness surfaces. The roughened surface shows a beneficial effect on two key indicators of osseointegration quality: bone-implant contact (BIC) and removal torque (RTQ), which reflects the amount of newly-form bone and the bond strength between implant and bone (23, 24). M. Gahlert. et al. (25) inserted zirconia implants with both machined and sandblasted surfaces into thirteen adult miniature pigs on the maxillae incisor area to test the different designs. The surface analysis showed that sandblasted zirconia implants had a higher surface roughness than machined zirconia implants. I. Mihatovia. et al. (26) investigated zirconia implants with three different surface roughness (Z1 < Z2 < Z3) in a dog model. Tissue biopsies after ten weeks of healing showed that the total BIC of three groups was significantly different as Z3(69.5%)>Z1(49.7%)>Z2(37.1%). It indicated that surface roughness plays a positive role in BIC. Another animal experiment compared machined zirconia surface with two kinds of porous zirconia surfaces verified that the RTQ value of the machined group showed significantly lower than all other types after six weeks healing period in rabbit tibia and femur (27). It demonstrated that zirconia with a rougher surface integrates more firmly in bone.

A study seeding human osteoblasts on 120 μm and 250 μm Al2O3 airborne particle abraded zirconia surfaces and machined surfaces proved that sandblasting surface before sintering could increase the initial osteoblasts cell adhesion up to 175%, compared with the machined samples. It also suggested that sandblasted zirconia implants can achieve higher stability in bone than machined zirconia implants and positively affect the interfacial shear strength (28). However, the mechanical forces formed during sandblasting will induce LTD (29). Even though LTD simulated by steam autoclave aging has few significant effects on the roughness, it still needs highlighting that the specimen preparation processing has a high impact on forming LTD (30). Also, sandblasting procedures will cause additional surface elemental composition due to inevitable alumina contamination (31).

Laser treatment is a fast, clean, contact-less, and easy-operating technique with high accuracy on material surfaces (32). The application of laser in dentistry began from the end of the 1990s on endodontic, periodontal, and oral surgery (33). Laser irradiation is verified to enhance surface roughness (34). It was reported that zirconia treated by femtosecond laser irradiation could create a consistent roughness on the interface between zirconia and resin cement and get higher early bond strength values (35). Fiber lasers, which can make 2 μm-wide grooves, were proved to produce adequate roughness on zirconia surfaces and increase new bone formation and mechanical strength on the bone-implant interface (36). Additionally, laser technologies positively affect wettability, acting as a critical determinant of cell adhesion, proliferation, and calcification, contributing to accelerating zirconia osseointegration (37, 38). Studies showed that laser treatment would not exhibit phase transformation to zirconia while improving mechanical properties (39, 40).

Creating a super-hydrophilic surface with a contact angle lower than 20° is the most attractive ultraviolet (UV) light treatment ability (41). High surface wettability contributes to improving integrations between soft tissue and dental implants (42). An animal study that placed UV-modified rough zirconia implant into rat femurs revealed the BIC increased by 1.7 folds after four weeks of healing compared with non-treated surfaces, and the amount of bone volume increased 13% at the same time (43). In addition, plenty of studies demonstrated that UV irradiation led to a significant improvement in initial cell adhesion, spreading, proliferation, and collagen release (44–46).

To investigate the effect of UV light on surface characteristics, Taskin Tuna. et al. (47) treated zirconia discs by UV light for 15min and found the contact angles were changed from 56.4°~69° to 2.5°~14.1° after UV treatment. Taskin's study elucidated that UV-treated samples showed a significant surface elemental composition change with a decrease of carbon by 43%~81% and an increase of oxygen by 19%~45%, which was thought to be the conversion factors of material hydrophobic to hydrophilic (48, 49). Meanwhile, an increase of the monoclinic crystalline was observed in this study. Conversely, another study demonstrated that no crystal phase transformation from tetragonal to monoclinic occurred. Thus, UV treatment could significantly reduce the aging of zirconia (50). However, crystalline transforming triggered by UV light is a controversial viewpoint, so that more efforts are needed for this promising strategy.

Acid etching treatment of zirconia using hydrofluoric acid, nitric acid, or sulfuric acid is an efficient method to roughen any irregular surfaces homogenously without destroying material morphology (51, 52). Since acid etching could remove the additional residues caused by sandblasting, acid etching usually worked in conjunction with sandblasting, known as sandblasted, large grit, acid-etched (SLA) (53). SLA is an efficient surface treatment with topographical and chemical changes, leading to a fundamental epochal shift in implantology (54). SLA zirconia implant shows good BIC values for bone integration without interfering with osteoblasts proliferation and differentiation (55, 56). An animal study compared SLA, sandblasting alone, and alkali-etched sandblasting treatments showed that SLA-treated zirconia was related to the highest BIC rate, followed by sandblasting, while the alkali-etching sandblasted group created the lowest BIC rate (57). However, heat-treatment and acid-etching can decrease the flexural strength of zirconia, suggesting it may not be as effective as it is applied on titanium (58).

Electrochemical treatments, such as electrochemical anodic oxidation, electrochemical deposition, or micro-arc electron, can make a composite coating or nanostructures on titanium surfaces and significantly improve osteointegration and antibacterial abilities (59). However, zirconia has a limitation in electrochemical application because of its non-conductive character. Liu et al. (60) introduced the electrochemical deoxidation (ECD) technique to improve zirconia surfaces, which removed oxygen from the solid metal oxides via molten salt electrolysis. It suggested that ECD treated zirconia showed well-arranged microporous, low contact angles, and a slight decrease in monoclinic phase content (−4.4 wt%).

Based on the advantages of electrochemical technology, much effort has contributed to fabricate the nanostructures on zirconia (61–63). Among all methods, nanotubes are an emerging surface modification developed for drug delivery systems. The nanotube structure is related to well pore controllability, high surface area, stable chemical ability, mechanical rigidity, and excellent compatibility (64, 65). A study showed that electrochemical anodization could form a highly self-organized zirconia nanotube with a diameter of about 50 nm~130 nm, a length of 17 μm, and a high aspect ratio of more than 300 (66). It was verified that the nanotube structure on zirconia could be successfully obtained, but it cannot achieve an orderly arrangement due to the otherness between zirconia and other metals, such as different conductivities. Thus, the reaction condition of zirconia anodic oxidation technology needs to be explored furtherly (67). Guo et al. (68) soaked zirconia nanotubes into stimulated body fluids (SBF) for 20~30 days and found bone-like apatite could form on the surface of zirconia nanotubes, which indicates that zirconia nanotubes could exhibit favorable bioactivity. However, electrochemical treatment on zirconia is still limited in laboratory research and needs further investigation.

Calcium phosphate (Ca3PO4, CaP) is a biological apatite that favors zirconia stabilizing, stimulates bone repair, and accelerates cell attachment and proliferation (69). The calcium phosphate family includes several members with different crystallization, dissolution, and phase transformation processes which exhibit various properties (70). Hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, HA) is one of the most stable and least soluble calcium phosphate family members. HA is the primary mineral component of bones and has bioactive abilities to assist tissue response and enhance osseointegration (71). It was reported that zirconia enriched with HA showed more new bone formation than those free of HA (72). HA coating also significantly improves coating stability and bonding strength on zirconia (73).

However, the technology of calcium phosphate coating usually provides unsatisfied stability and weak bond strength to the base materials (74). Excess calcium ions even induce cubic phase zirconia which results in low mechanical strength (75). The thermal spraying coating method, such as plasma spraying, is usually used for calcium phosphate coating due to its high deposition rate and low cost. Nevertheless, it is not appropriate for complex morphology because of the high processing temperature and inhomogeneous thickness. Such inhomogeneous thickness can induce delamination and exfoliation, thus causes the premature failure of implants (76). The sol-gel method is developed to resist these drawbacks, which is proved to be an alternative low-temperature coating and results in a relatively homogeneous surface (77). Other advanced techniques are also introduced into calcium phosphate coating. For example, wet powder spraying (WPS) can accomplish complex curved surfaces with different thicknesses relying on its particular versatility (78). Aerosol deposition technique could produce a high-quality coating on the zirconia surface with controlled pore size and porosity (79).

Bioactive glass is a composition system of Na2O-CaO-SiO2-P2O5, which was commercially trademarked as Bioglass 45S5 (80). The bioactive properties make bioglass applicable as a coating material for dental implants. Bioglass positively interacts with the biological environment by forming a hydroxyapatite layer between the tissue and material (81). It was found that bioglass induced a rapid chemical combination and a faster apatite formation on bone tissue, which indicated that the healing period of dental implants might be reduced by using bioglass coatings (82).

Zirconia implant has a challenge in the bioglass coating due to its long-term stability. The insufficient mechanical properties will induce bioglass to be fragile (83). Moreover, bioglass is incompatible for thermal coating on zirconia because of its higher thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) (15·10−6 K−1) than zirconia (10.8-12.5·10−6 K−1) (84). During cooling, bioglass and zirconia or other metals will shrink in different degrees, making coating cracks. An ideal situation is that bioglass has a slightly lower TEC than the base material (85). A study proved that substituting the bioglass elements, such as replacing Na2O with K2O and replacing CaO with MgO, will efficiently decrease the TEC of bioglass (86). A. Kirsten et al. (87) added a tailored substitution of alkaline earth metals and alkaline metals into Bioglass 45S5, showed that the TEC of the novel glass was slightly lower (11.58·10−6 K−1) than that of the zirconia (11.67·10−6 K−1). It might provide a possibility of applying bioglass coatings on zirconia surface modification.

Arginine–glycine–aspartate (Arg–Gly–Asp or RGD) tripeptides widely exist in adhesive proteins in the extracellular matrix, act as a significant factor in cell adhesion (88). Immobilizing these biomolecules such as RGD peptides on the material surface to promote the biological responses and biochemical properties is the so-called biomimetic surface modification, also known as biofunctionalization (89). RGD peptide can be successfully coated onto the zirconia surfaces as a stable and functional chemically attached coating (90). A study that grafted RGD-containing peptides onto zirconia validated that it can accelerate the osseointegration, improve the per-mucosal sealing, and incorporate to antimicrobial (91). Consistently, a study formed a hybrid nano/micro-scale zirconia surface by coating with RGD and magnesium ion (Mg+) revealed that it could improve the cell adhesion, spreading, and migration of osteoblasts and accelerate their mineralization (92).

Polydopamine (PDA) is an essential component of marine mussel adhesion proteins, one of its unique abilities is attaching to organic and inorganic materials underwater (93). Since 2007, PDA adhesive coating has been widely applied on several material surfaces, including noble metals, oxides, semiconductors, synthetic polymers, and ceramics (94). A study suggested that PDA-coated zirconia performed better than uncoated zirconia on cell adhesion, spreading, and proliferation (95). Besides great adhesive ability, PDA coating enhances antimicrobial properties by reducing bacterial adhesion, which plays a positive role in peri-implant soft-tissue regeneration (96). Xu. et al. coated a PDA-containing nanolayer on a 3D-plotted bio-ceramic scaffold and pointed out it was a viable and effective strategy to accelerate osteogenesis (97). Additionally, PDA can be used as a cross-linking. A recent study that treated zirconia with PDA coating showed that PDA improved the bond strength between the resin cement and zirconia surface (98). The manufacture of PDA coating is easy-going and multi-functional. PDA coating on zirconia should be a worthy exploration aspect by more researchers.

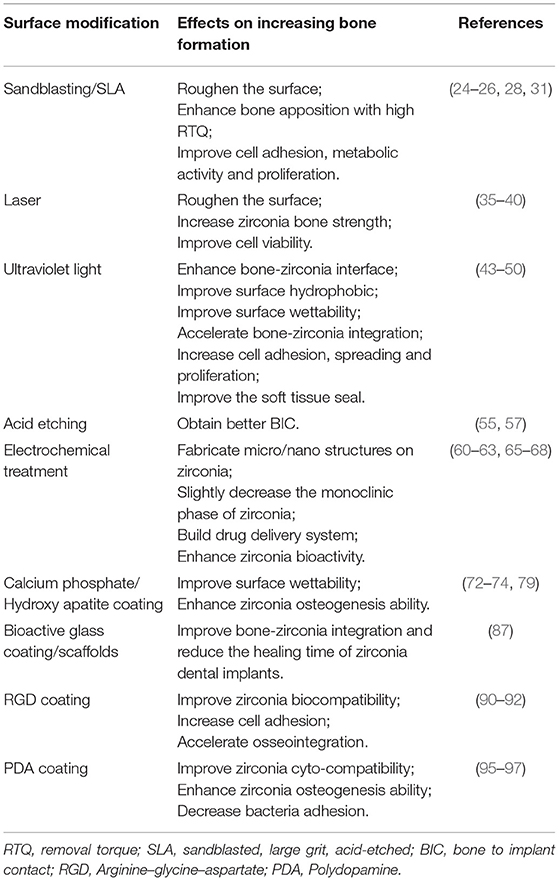

More and more researchers are devoted to investigating metal-free dental implants, especially zirconia, which is considered a competitive material for dental implants. However, the exploration of zirconia dental implants needs more effort. Surface modifications are introduced to improve zirconia properties. It effectively enhances bone osseointegration by adjusting surface roughness, morphology, hydrophilicity, chemical stability, and antibacterial resistance. The strategies for bone tissue engineering through surface modifications on zirconia-based materials in the review were summarized in Table 1. Sandblasting is a practical approach to obtain optimal micro-roughness surfaces. However, the formed mechanical forces during sandblasting will induce the LTD phenomenon. It would also slightly change the surface elemental composition due to inevitable alumina contamination. From that point, the acid etching method was introduced. For zirconia, acid etching and electrochemical treatments are less efficient than metals, and they are still under laboratory exploration. Contact-less physical treatments such as laser and UV are applied to surface modification, improving surface properties and cell viability. More recently, coatings are also introduced as surface treatments, which could enhance bioactivity, biocompatibility, or potential antibacterial properties of zirconia. However, it still faces a problem about the stabilities and application of these coatings. This review summarizes not all but most frequently used and potential techniques and gives general information on the usage of surface modification on zirconia, and it suggests surface modification would successfully improve the surface characteristic and compatibility of zirconia materials.

Table 1. Strategies for bone tissue engineering through surface modifications on zirconia-based materials in review.

LS and GH contributed to the conception and design of the study. LS collected the articles, organized the database, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LS and GH wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Elani HW, Starr JR, Da Silva JD, Gallucci GO. Trends in dental implant use in the US, 1999–2016, and projections to 2026. J Dental Res. (2018). 97:1424–30. doi: 10.1177/0022034518792567

2. Howe MS, Keys W, Richards D. Long-term (10-year) dental implant survival: a systematic review and sensitivity meta-analysis. J Dent. (2019) 84:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2019.03.008

3. Sicilia A, Cuesta S, Coma G, Arregui I, Guisasola C, Ruiz E, et al. Titanium allergy in dental implant patients: a clinical study on 1500 consecutive patients. Clin Oral Implants Res. (2008) 19:823–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01544.x

4. Ioannidis A, Cathomen E, Jung RE, Fehmer V, Hüsler J, Thoma DS. Discoloration of the mucosa caused by different restorative materials–a spectrophotometric in vitro study. Clin Oral Implants Res. (2017) 28:1133–8. doi: 10.1111/clr.12928

5. Andreiotelli M, Wenz HJ, Kohal RJ. Are ceramic implants a viable alternative to titanium implants? A systematic literature review. Clin Oral Implant Res. (2009) 20:32–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01785.x

6. Cionca N, Hashim D, Mombelli A. Zirconia dental implants: where are we now, and where are we heading? Periodontology. (2017) 73:241–58. doi: 10.1111/prd.12180

7. Glauser R, Sailer I, Wohlwend A, Studer S, Schibli M, Schärer P. Experimental zirconia abutments for implant-supported single-tooth restorations in esthetically demanding regions: 4-year results of a prospective clinical study. Int J Prosthodont. (2004) 17:285–90.

8. Ko HC, Han JS, Bächle M, Jang JH, Shin SW, Kim DJ. Initial osteoblast-like cell response to pure titanium and zirconia/alumina ceramics. Dental Mater. (2007) 23:1349–55. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.11.023

9. Depprich R, Ommerborn M, Zipprich H, Naujoks C, Handschel J, Wiesmann HP, et al. Behavior of osteoblastic cells cultured on titanium and structured zirconia surfaces. Head Face Med. (2008) 4:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-4-29

10. Turon-Vinas M, Anglada M. Strength and fracture toughness of zirconia dental ceramics. Dental Materials. (2018) 34:365–75. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2017.12.007

11. Deligianni DD, Katsala N, Ladas S, Sotiropoulou D, Amedee J, Missirlis YF. Effect of surface roughness of the titanium alloy Ti−6Al−4V on human bone marrow cell response and on protein adsorption. Biomaterials. (2001) 22:1241–51. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00274-X

12. Bosshardt DD, Chappuis V, Buser D. Osseointegration of titanium, titanium alloy and zirconia dental implants: current knowledge and open questions. Periodontology. (2017) 73:22–40. doi: 10.1111/prd.12179

13. Han A, Tsoi JKH, Lung CYK, Matinlinna JP. An introduction of biological performance of zirconia with different surface characteristics: a review. Dent Mater J. (2020) 39:523–30. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2019-200

14. Gautam C, Joyner J, Gautam A, Rao J, Vajtai R. Zirconia based dental ceramics: structure, mechanical properties, biocompatibility and applications. Dalt Trans. (2016) 45:19194–215. doi: 10.1039/C6DT03484E

15. Piconi C, Maccauro G. Zirconia as a ceramic biomaterial. Biomaterials. (1999) 20:1–25. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00010-6

16. Sanon C, Chevalier J, Douillard T, Cattani-Lorente M, Scherrer SS, Gremillard L, et al. new testing protocol for zirconia dental implants. Dent Mater. (2015) 31:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.09.002

17. Assal PA. The osseointegration of zirconia dental implants. Schweizer Monatsschrift fur Zahnmedizin. (2013) 123:644–54.

18. Lughi V, Sergo V. Low temperature degradation-aging-of zirconia: A critical review of the relevant aspects in dentistry. Dental materials. (2010) 26:807–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.04.006

19. Chevalier J. What future for zirconia as a biomaterial? Biomaterials. (2006) 27:535–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.034

20. Chevalier J, Loh J, Gremillard L, Meille S, Adolfson E. Low-temperature degradation in zirconia with a porous surface. Acta Biomater. (2011) 7:2986–93. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.006

21. Kohal RJ, Att W, Bächle M, Butz F. Ceramic abutments and ceramic oral implants. An update Periodontol. (2008) 47:224–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00243.x

22. Hanawa T. Zirconia versus titanium in dentistry: a review. Dent Mater J. (2020) 39:24–36. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2019-172

23. Manzano G, Herrero R, Montero J. Comparison of clinical performance of zirconia implants and titanium implants in animal models: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Implants. (2014) 29:311–20. doi: 10.11607/jomi.2817

24. Buser D, Nydegger T, Hirt HP, Cochran DL, Nolte LP. Removal torque values of titanium implants in the maxilla of miniature pigs. Int J Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. (1998) 13:611–9.

25. Gahlert M, Gudehus T, Eichhorn S, Steinhauser E, Kniha H, Erhardt W. Biomechanical and histomorphometric comparison between zirconia implants with varying surface textures and a titanium implant in the maxilla of miniature pigs. Clin Oral Implants Res. (2007) 18:662–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01401.x

26. Mihatovic I, Golubovic V, Becker J. Schwarz, F. Bone tissue response to experimental zirconia implants. Clin Oral Investigat. (2017) 21:523–32. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1904-2

27. Sennerby L, Dasmah A, Larsson B, Iverhed M. Bone tissue responses to surface-modified zirconia implants: a histomorphometric and removal torque study in the rabbit. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. (2005) 7:s13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2005.tb00070.x

28. Al Qahtani WM, Schille C, Spintzyk S, Al Qahtani MS, Engel E, Geis-Gerstorfer J, et al. Effect of surface modification of zirconia on cell adhesion, metabolic activity and proliferation of human osteoblasts. Biomed Eng. (2017) 62:75–87. doi: 10.1515/bmt-2015-0139

29. Fratucelli ÉDDO, Candido LM, Pinelli LAP. Surface properties and flexural strength of a monolithic zirconia submitted to grinding and regenerative heat treatment. Int J Appl Ceramic Technol. (2021) 18:525–31. doi: 10.1111/ijac.13660

30. Yang H, Xu YL, Hong G, Yu H. Effects of low-temperature degradation on the surface roughness of yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal ceramics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthet Dent. (2021) 125:222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2020.01.005

31. Blatt S, Pabst AM, Schiegnitz E, Hosang M, Ziebart T, Walter C, et al. Early cell response of osteogenic cells on differently modified implant surfaces: Sequences of cell proliferation, adherence and differentiation. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. (2018) 46:453–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.12.021

32. Roitero E, Anglada M, Mücklich F, Jiménez-Piqué E. Mechanical reliability of dental grade zirconia after laser patterning. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. (2018) 86:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.06.039

33. Martens LC. Laser physics and a review of laser applications in dentistry for children. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. (2011) 12:61–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03262781

34. Zhang H, Du K, Li X. Enhancement blueshift of high-frequency laser-induced periodic surface structures with preformed nanoscale surface roughness. Opt Express. (2019) 27:19973–83. doi: 10.1364/OE.27.019973

35. Prieto MV, Gomes ALC, Martín JM, Lorenzo AA, Mato VS, Martínez AA. The effect of femtosecond laser treatment on the effectiveness of resin-zirconia adhesive: an in vitro study. Laser Appl Med Sci Res Cent. (2016) 7:214–9. doi: 10.15171/jlms.2016.38

36. Taniguchi Y, Kakura K, Yamamoto K, Kido H, Yamazaki J. Accelerated osteogenic differentiation and bone formation on zirconia with surface grooves created with fiber laser irradiation. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. (2016) 18:883–94. doi: 10.1111/cid.12366

37. Aivazi M, Fathi M, Nejatidanesh F, Mortazavi V, Beni BH, Matinlinna JP. Effect of surface modification on viability of L929 cells on zirconia nanocomposite substrat. J Lasers Med Sci. (2018) 9:87–91. doi: 10.15171/jlms.2018.18

38. Liu D, Matinlinna JP, Tsoi JKH, Pow EH, Miyazaki T, Shibata Y, et al. A new modified laser pretreatment for porcelain zirconia bonding. Dent Mater. (2013) 29:559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.03.002

39. Delgado-Ruíz RA, Calvo-Guirado JL, Moreno P, Guardia J, Gomez-Moreno G, Mate-Sánchez JE, et al. Femtosecond laser microstructuring of zirconia dental implants. J Biomed Mater Res - Part B Appl Biomater. (2011) 96:91–100. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31743

40. Parry JP, Shephard JD, Hand DP, Moorhouse C, Jones N, Weston N. Laser micromachining of zirconia (Y-TZP) ceramics in the picosecond regime and the impact on material strength. Int J Appl Ceram Tec. (2011) 8:163–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7402.2009.02420.x

41. Schünemann FH, Galárraga-Vinueza ME, Magini R, Fredel M, Silva F, Souza JC, et al. Zirconia surface modifications for implant dentistry. Mater Sci Eng C. (2019) 98:1294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.01.062

42. Wang Y, Zhang Y, Sculean A, Bosshardt DD, Miron RJ. Macrophage behavior and interplay with gingival fibroblasts cultured on six commercially available titanium, zirconium, and titanium-zirconium dental implants. Clin Oral Investig. (2019) 23:3219–27. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2736-z

43. Brezavšček M, Fawzy A, Bächle M, Tuna T, Fischer J, Att W. The effect of UV treatment on the osteoconductive capacity of zirconia-based materials. Materials. (2016) 9:958. doi: 10.3390/ma9120958

44. Yang Y, Zhou J, Liu X, Zheng M, Yang J, Tan J. Ultraviolet light-treated zirconia with different roughness affects function of human gingival fibroblasts in vitro: The potential surface modification developed from implant to abutment. J Biomed Mater Res - Part B Appl Biomater. (2015) 103:116–24. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33183

45. Guo L, Smeets R, Kluwe L, Hartjen P, Barbeck M, Cacaci C, et al. Cytocompatibility of titanium, zirconia and modified PEEK after surface treatment using UV light or non-thermal plasma. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:5596. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225596

46. Tuna T, Wein M, Altmann B, Steinberg T, Fischer J, Att W. Effect of ultraviolet photofunctionalisation on the cell attractiveness of zirconia implant materials. Eur Cells Mater. (2015) 29:82–96. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v029a07

47. Tuna T, Wein M, Swain M, Fischer J, Att W. Influence of ultraviolet photofunctionalization on the surface characteristics of zirconia-based dental implant materials. Dent Mater. (2015) 31:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.10.008

48. Henningsen A, Smeets R, Heuberger R, Jung OT, Hanken H, Heiland M, et al. Changes in surface characteristics of titanium and zirconia after surface treatment with ultraviolet light or non-thermal plasma. Eur J Oral Sci. (2018) 126:126–34. doi: 10.1111/eos.12400

49. Al Qahtani MS, Wu Y, Spintzyk S, Krieg P, Killinger A, Schweizer E, et al. UV-A and UV-C light induced hydrophilization of dental implants. Denl Mater. (2015) 31:157–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.04.011

50. Roy M, Pompella A, Kubacki J, Piosik A, Psiuk B, Klimontko J, et al. Photofunctionalization of dental zirconia oxide: Surface modification to improve bio-integration preserving crystal stability. Colloids Surfac B: Biointerfaces. (2017) 156:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.05.031

51. Nishiguchi S, Kato H, Neo M, Oka M, Kim HM, Kokubo T, et al. Alkali-and heat-treated porous titanium for orthopedic implants. J Biomed Mater Res. (2001) 54:198–208.3. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200102)54:2<198::AID-JBM6>3.0.CO;2-7

52. Iwaya Y, Machigashira M, Kanbara K, Miyamoto M, Noguchi K, Izumi Y, et al. Surface properties and biocompatibility of acid-etched titanium. Dent Mater J. (2008) 27:415–21. doi: 10.4012/dmj.27.415

53. Cabrini M, Cigada A, Rondell G, Vicentini B. Effect of different surface finishing and of hydroxyapatite coatings on passive and corrosion current of Ti6Al4V alloy in simulated physiological solution. Biomaterials. (1997) 18:783–7. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(96)00205-0

54. Annunziata M, Guida L. The effect of titanium surface modifications on dental implant osseointegration. Biomater Oral Craniomaxillofacial Appl. (2015) 17:62–77. doi: 10.1159/000381694

55. Hafezeqoran A, Koodaryan R. Effect of zirconia dental implant surfaces on bone integration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. (2017) 2017:12. doi: 10.1155/2017/9246721

56. Kohal RJ, Baechle M, Han JS, Hueren D, Huebner U, Butz F. In vitro reaction of human osteoblasts on alumina-toughened zirconia. Clin Oral Implants Res. (2009) 20:1265–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01735.x

57. Saulacic N, Erdösi R, Bosshardt DD, Gruber R, Buser Acid D. and alkaline etching of sandblasted zirconia implants: a histomorphometric study in miniature pigs. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. (2014) 16:313–22. doi: 10.1111/cid.12070

58. Sato H, Yamada K, Pezzotti G, Nawa M, Ban S. Mechanical properties of dental zirconia ceramics changed with sandblasting and heat treatment. Dent Mater J. (2008) 27:408–14. doi: 10.4012/dmj.27.408

59. Liu J, Pathak JL, Hu X, Jin Y, Wu Z, Al-Baadani MA, et al. Sustained release of zoledronic acid from mesoporous TiO2-layered implant enhances implant osseointegration in osteoporotic condition. J Biomed Nanotechnol. (2018) 14:1965–78. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2018.2635

60. Liu J, Hong G, Wu YH, Endo K, Han JM, Kumamoto H, et al. A novel method of surface modification by electrochemical deoxidation: effect on surface characteristics and initial bioactivity of zirconia. J Biomed Mater Res - Part B Appl Biomater. (2017) 105:2641–52. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33805

61. Zhao J, Wang X, Xu R, Meng F, Guo L, Li Y. Fabrication of high aspect ratio zirconia nanotube arrays by anodization of zirconium foils. Materials Letters. (2008) 62:4428–30. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2008.07.054

62. Tsuchiya H, Macak JM, Sieber I, Schmuki P. Self-organized high-aspect-ratio nanoporous zirconium oxides prepared by electrochemical anodization. Small. (2005) 1:722–5. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400163

63. Zhao J, Xu R, Wang X, Li Y. In situ synthesis of zirconia nanotube crystallines by direct anodization. Corrosion Science. (2008) 50:1593–7. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2008.01.026

64. Roy P, Berger S, Schmuki P. TiO2 nanotubes: synthesis and applications. Angewandte Chemie Int Ed. (2011) 50:2904–39. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001374

65. Losic D, Simovic S. Self-ordered nanopore nanotube platforms for drug delivery applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. (2009) 6:1363–81. doi: 10.1517/17425240903300857

66. Tsuchiya H, Macak JM, Taveira L, Schmuki P. Fabrication characterization of smooth high aspect ratio zirconia nanotubes. Chem Phys Lett. (2005) 410:188–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2005.05.065

67. Jiang W, He J, Zhong J, Lu J, Yuan S, Liang B. Preparation photocatalytic performance of ZrO2 nanotubes fabricated with anodization process. Appl Surf Sci. (2014) 307:407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.04.047

68. Guo L, Zhao J, Wang X, Xu R, Lu Z, Li Y. Bioactivity of zirconia nanotube arrays fabricated by electrochemical anodization. Mater Sci Eng C. (2009) 29:1174–7. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2008.10.003

69. Dorozhkin SV. Calcium orthophosphates in nature, biology and medicine. Materials. (2009) 2:399–498. doi: 10.3390/ma2020399

70. Wang L, Nancollas GH. Calcium orthophosphates: crystallization and dissolution. Chem Rev. (2008) 108:4628–69. doi: 10.1021/cr0782574

71. Frame JW. Hydroxyapatite as a biomaterial for alveolar ridge augmentation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (1987) 16:642–55. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(87)80048-6

72. Aboushelib MN, Shawky R. Osteogenesis ability of CAD/CAM porous zirconia scaffolds enriched with nano-hydroxyapatite particles. Int J Implant Dent. (2017) 3:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s40729-017-0082-6

73. Pardun K, Treccani L, Volkmann E, Li Destri G, Marletta G, Streckbein P, et al. Characterization of wet powder-sprayed zirconia/calcium phosphate coating for dental implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. (2015) 17:186–98. doi: 10.1111/cid.12071

74. Yang JZ, Sultana R, Ichim P, Hu XZ, Huang ZH, Yi W, et al. Micro-porous calcium phosphate coatings on load-bearing zirconia substrate: processing, property and application. Ceram Int. (2013) 39:6533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.01.086

75. Ban S, Okuda Y, Noda M, Tsuruki J, Kawai T, Kono H. Contamination of dental zirconia before final firing: effects on mechanical properties. Dent Mater J. (2013) 32:1011–9. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2013-222

76. Le Guéhennec L, Soueidan A, Layrolle P, Amouriq Y. Surface treatments of titanium dental implants for rapid osseointegration. Dent Mater. (2007) 23:844–54. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.06.025

77. Jin SD, Um SC, Lee JK. Surface modification of zirconia substrate by calcium phosphate particles using Sol–Gel method. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. (2015) 15:5946–50. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2015.10439

78. Pardun K, Treccani L, Volkmann E, Streckbein P, Heiss C, Destri GL, et al. Mixed zirconia calcium phosphate coatings for dental implants: Tailoring coating stability and bioactivity potential. Mater Sci Eng C. (2015) 48:337–46. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.12.031

79. Cho Y, Hong J, Ryoo H, Kim D, Park J, Han J. Osteogenic responses to zirconia with hydroxyapatite coating by aerosol deposition. J Dent Res. (2015) 94:491–9. doi: 10.1177/0022034514566432

80. Rizwan M, Hamdi M, Basirun WJ. Bioglass® 45S5-based composites for bone tissue engineering and functional applications. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. (2017) 105:3197–223. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36156

81. Albrektsson T, Brånemark PI, Hansson HA, Lindström J. Osseointegrated titanium implants: requirements for ensuring a long-lasting, direct bone-to-implant anchorage in man. Acta Orthop Scand. (1981) 52:155–70. doi: 10.3109/17453678108991776

82. Chen QZ, Thompson ID, Boccaccini AR. 45S5 Bioglass®-derived glass–ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. (2006) 27:2414–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.025

83. Chen Q, Baino F, Spriano S, Pugno NM, Vitale-Brovarone C. Modelling of the strength–porosity relationship in glass-ceramic foam scaffolds for bone repair. J Eur Ceram Soc. (2014) 34:2663–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2013.11.041

85. Skallevold HE, Rokaya D, Khurshid Z, Zafar MS. Bioactive glass applications in dentistry. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:5960. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235960

86. Gomez-Vega JM, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ. Bioactive glass coatings with hydroxyapatite and Bioglass® particles on Ti-based implants. 1 Process Biomater. (2000) 21:105–11. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(99)00131-3

87. Kirsten A, Hausmann A, Weber M, Fischer J, Fischer H. Bioactive thermally compatible glass coating on zirconia dental implants. J Dent Res. (2015) 94:297–303. doi: 10.1177/0022034514559250

88. Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD. New perspectives in cell adhesion: RGD and integrins. Science. (1987) 238:491–7. doi: 10.1126/science.2821619

89. Karthigeyan S, Ravindran AJ, Bhat RT, Nageshwarao MN, Murugesan SV, Angamuthu V. Surface modification techniques for zirconia-based bioceramics: a review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. (2019) 11:131–4. doi: 10.4103/JPBS.JPBS_45_19

90. Hsu SK, Hsu HC, Ho WF, Yao CH, Chang PL, Wu SC. Biomolecular modification of zirconia surfaces for enhanced biocompatibility. Thin Solid Films. (2014) 572:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2014.07.068

91. Fernandez-Garcia E, Chen X, Gutierrez-Gonzalez CF, Fernandez A, Lopez-Esteban S, Aparicio C. Peptide-functionalized zirconia and new zirconia/titanium biocermets for dental applications. J Dent. (2015) 43:1162–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.06.002

92. Huang Z, Wang Z, Li C, Zhou N, Liu F, Lan J. The osteoinduction of RGD and Mg ion functionalized bioactive zirconia coating. J Mater Sci. (2019) 30:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10856-019-6298-7

93. Yang L, Phua SL, Teo JKH, Toh CL, Lau SK, Ma J, et al. biomimetic approach to enhancing interfacial interactions: polydopamine-coated clay as reinforcement for epoxy resin. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2011) 3:3026–32. doi: 10.1021/am200532j

94. Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB. Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings. Science. (2007) 318:426–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1147241

95. Liu YT, Lee TM, Lui TS. Enhanced osteoblastic cell response on zirconia by bio-inspired surface modification. Colloids Surf B:. (2013) 106:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.01.023

96. Liu M, Zhou J, Yang Y, Zheng M, Yang J, Tan J. Surface modification of zirconia with polydopamine to enhance fibroblast response and decrease bacterial activity in vitro: a potential technique for soft tissue engineering applications. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. (2015) 136:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.06.047

97. Xu M, Zhai D, Xia L, Li H, Chen S, Fang B, et al. Hierarchical bioceramic scaffolds with 3D-plotted macropores and mussel-inspired surface nanolayers for stimulating osteogenesis. Nanoscale. (2016) 8:13790–803. doi: 10.1039/C6NR01952H

Keywords: zirconia, ceramic, surface modification, dental implant, osseointegration

Citation: Sun L and Hong G (2021) Surface Modifications for Zirconia Dental Implants: A Review. Front. Dent. Med. 2:733242. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2021.733242

Received: 30 June 2021; Accepted: 10 September 2021;

Published: 07 October 2021.

Edited by:

Vesna Miletic, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Rui Zhou, Xi'an Jiaotong University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Sun and Hong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guang Hong, aG9uZy5ndWFuZy5kNkB0b2hva3UuYWMuanA=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.