- 1Advanced Specialty Program in Endodontics, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, University of the Pacific, Stockton, CA, United States

- 2Advanced Specialty Program in Orthodontics, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, University of the Pacific, Stockton, CA, United States

In December 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first identified as an acute infectious disease in Wuhan, China, and subsequently led to an ongoing pandemic. At the onset of the pandemic, dental professionals were understood to face the greatest exposure risk to SARS-CoV-2 due to aerosolization of fluids from the oral cavity and respiratory airways. As a result, dental professionals, including academic institutions and their students and residents, halted much of their operations to minimize exposure risks and potentially slow the spread of infection to peers and patients alike. Currently, there is little in the literature that describes the changes that academic institutions have implemented in the face of pandemics. This study will discuss the chronology, modifications, and possible resultant outcomes of COVID-19 related events in respect to graduate endodontic programs in the United States.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is the most recent pandemic in modern history after the World Health Organization declared it a pandemic in March of 2020 (1). The previously most devastating pandemic was that of the “Spanish Flu of 1918,” caused by a particularly virulent strain of H1N1 influenza that left 50 million dead. Since then there have been three additional pandemics—in 1957, 1968, and 2009 (2). The advancement of medicine, technologies, and knowledge—particularly of diagnosis, vaccination, and disease surveillance—has greatly improved the prevention and supportive care of diseases since 1918. Although there are organizations tasked with pandemic response planning, there are still great challenges in preparedness, management, and treatment modalities for widespread novel diseases. In particular, there is little in the literature that describes the preparation and responses of the dental field and its educational institutions to pandemics, specifically ones transmitted by aerosols. This article strives to review the chronology, modifications, and possible resultant outcomes of COVID-19 related events with a focus on graduate endodontic programs in the United States.

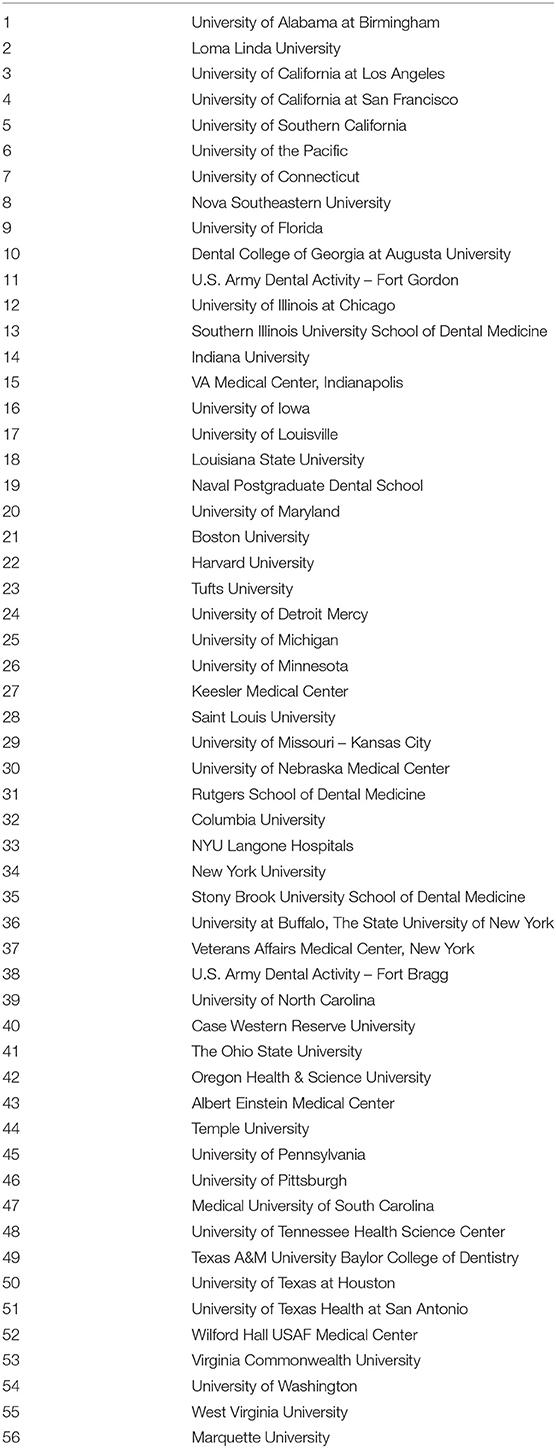

Endodontics Specialty Education

Endodontics is a specialty of dentistry recognized by the American Dental Association (3) that specializes in diagnosing and treating tooth pain and performing root canal treatment (4). To become an endodontist in the United States, one requires training beyond dental school; currently, there are 56 operational postgraduate endodontic programs in the United States that are accredited by the Commission on Dental Accreditation (5, 6) (Table 1). The length of the programs may range from 24 to 36 months, and graduates may receive a Certificate in Endodontics or in conjunction with a Master's degree, which is not offered in every program. Graduate endodontic programs also vary in their respective institutions; they may be public, private, federal, hospital-based, or through the Armed Forces.

Standards of Clinical Practice and Dental Education

In the United States, entry into the dental profession requires graduation from a Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA)-accredited dental school. Admission into a dental school may require a bachelor's degree, satisfying a number of course requirements (i.e., Biology, General Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, etc.), and a satisfactory score on the Dental Admission Test if one is an American citizen. International applicants may be required to have additional requirements, such as taking the Test of English as a Foreign Language. The ability to legally practice dentistry varies state by state. While all mandate that an applicant for licensure to practice dentistry must graduate from a dental school, some require that the applicant complete a minimum of 1 year of postgraduate training in general dentistry (7) or that the applicant successfully pass a competency exam proctored by various organizations (i.e., Western Regional Examining Board, Commission on Dental Competency Assessments, etc.) (8).

Organizations and Associations That Influence the Practice of Dentistry

The American Dental Association (ADA) is the accredited dental standards body of the American National Standards Institute and is also the representative for the International Organization for Standardization Technical Committee in Dentistry (9). The ADA was founded in 1859 and serves as the largest national dental association; it plays a role in advocating for dentists and dental public health (10). The ADA also serves to provide standards in many aspects of the dental profession. While the ADA works on the national level, there are also state and local dental governing bodies.

The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) is the national organization for the field of endodontics founded in 1943 that advocates for the specialty, which was recognized by the ADA in 1963 (11). Like the ADA, the AAE plays a role in advocating for the dental public health, especially in regard to patient pulpal and periapical health.

The CODA (5) was established in 1975 and serves the public and profession by developing accreditation standards that promote and monitor the continuous quality and improvement of dental education programs (12). Dental education programs must report to CODA to maintain accreditation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, dental education programs were required to report to CODA the changes implemented in each respective program, which will be discussed later in this report.

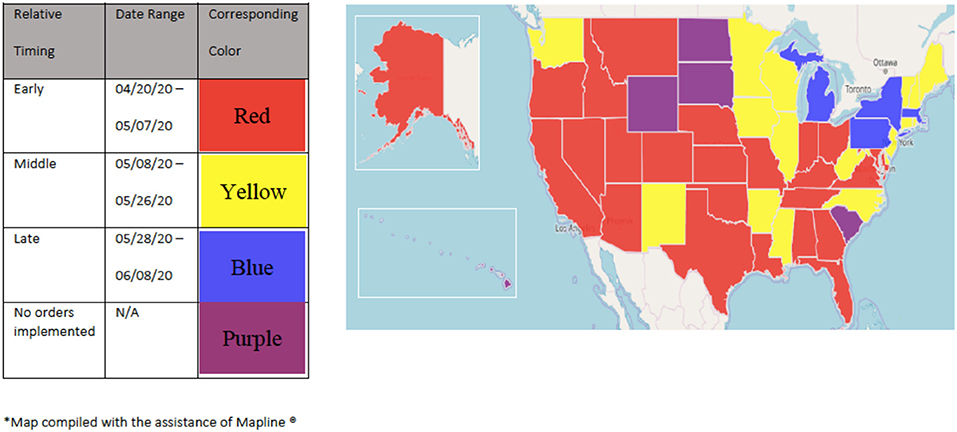

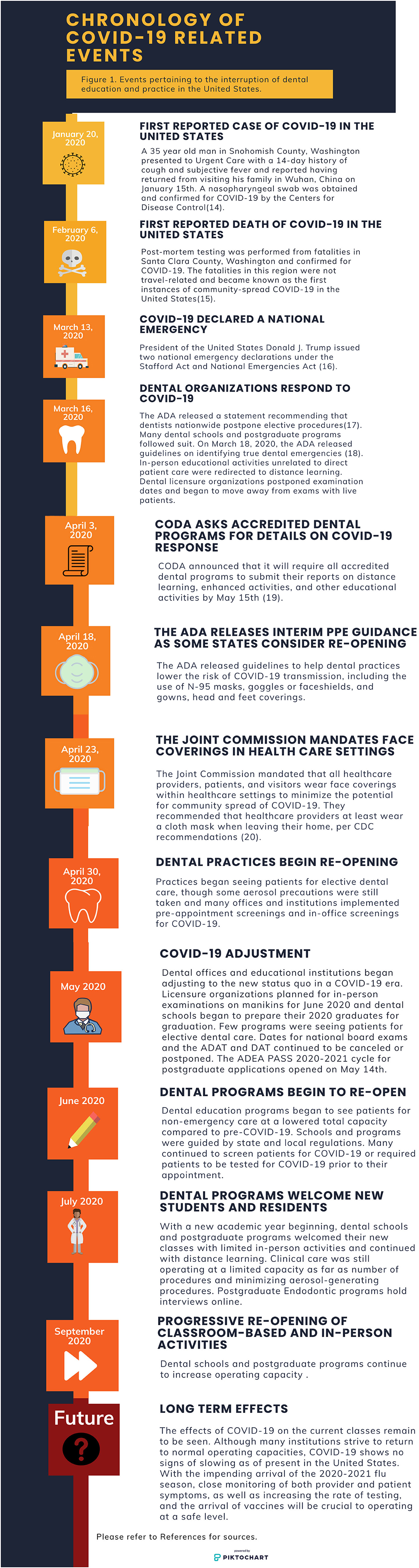

Chronology of COVID-19 Related Events Leading to the Interruption Dental Education and/or Practice

The first confirmed case of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States was reported on January 20, 2020 (13, 14) in the state of Washington. The first reported death from the disease was February 6, 2020, from the San Francisco Bay Area (15). It was not until March 2020 that COVID-19 made its impact on the day-to-day lives of Americans. Restrictions on public gatherings were made to reduce or slow the spread of the disease, which included the immediate halt of in-person attendance in schools. Endodontic programs were not immune to these stipulations. In-person classes moved to remote learning modalities, and patient care was limited to an emergency-basis only. As COVID-19 has become better understood, guidelines for dental-related patient care changed and continue to change. See Figure 1 for a summary of the COVID-19 related changes to dental education and practice (14–20).

Figure 1. Events pertaining to the interruption of dental education and practice in the United States.

Temporary Modifications

Clinical Care

On March 16, 2020, the ADA voted to recommend that dentists postpone all but emergency and urgent care in order to help mitigate the spread of COVID-19 and alleviate the burden that dental emergencies would place on hospital emergency departments (21). Tele-dentistry was encouraged to monitor patient symptoms unless treatment was absolutely indicated as a true dental emergency (22).

Endodontic programs in the United States were restricted to emergency clinical care. Due to the nature of dental pain, oftentimes being related to endodontic pain, endodontists and endodontic programs were operating as frontline workers (23).

In direct response to the COVID-19 pandemic, new protocols were implemented for screening patients prior to their appointments, as well as when they arrive for treatment (24), which will be described later in this article.

Curriculum Delivery and Content

In-person activities unrelated to direct patient care were re-directed to distance learning modalities, such as conference calls, Zoom, Skype, Webex, and webinars or online continuing education courses. These aspects of a curriculum include didactic courses, literature reviews, and case seminars. The delivery of didactic content also varied among synchronous and asynchronous methods. Asynchronous content delivery offers students the opportunity to learn at their own pace. There are ongoing studies focused on evaluating the differences in performance between synchronous and asynchronous delivery of educational content. Previous examinations that had been held in person also saw a change. Examinations were administered online, as written projects, or through conference calls in the form of oral examinations. Future studies should quantitate these different forms of examinations across the different postgraduate endodontic programs, which may help identify whether these temporary modifications are adequate assessment modalities.

The Role of the American Dental Association's CODA Policy on Interruption of Education

The COVID-19-related interruptions to clinical care and other academic activities in postgraduate endodontic programs merited accommodations by CODA, which released a statement regarding COVID-19 as early as March 13, 2020 (25). CODA released its first announcement for guidance on the interruption of education on March 30, 2020, after receiving guidance from the United States Department of Education (26); the organization then announced on April 3, 2020, to dental education programs that they report on their respective interruptions to education as a result of the pandemic by May 15, 2020 (27).

On April 14, 2020, temporary flexibility in accreditation standards in response to COVID-19 for the Class of 2020 was released (28). This included temporary flexibility related to the percentage of time dedicated to clinical care and research requirements, as well as assessment methods. Since the April announcement, CODA has met several times to announce amendments to or extensions on the initial temporary guidelines. As early as August 2020, CODA extended use of distance education through December 31, 2020 (27). CODA announced October 20, 2020 temporary guidelines for accreditation standards for the Class of 2021 (29).

In respect to graduate endodontics, CODA has allowed the temporary use of distance education and the use of simulated competencies in lieu of patient-based scenarios should it be necessary. As of the October 2020 temporary guidelines for graduates of the Class of 2021, programs have been allowed to adjust minimum program expectations, provided that the program assures that its resident is competent upon graduation. In addition to the quantitative changes that CODA recommends, the organization similarly suggested temporal changes from the minimum of 104 weeks to 24 months with a minimum of 40% and maximum of 60% of the program devoted to clinical care. Modification to research requirements was also recommended: a program may accept a research protocol in lieu of a publishable manuscript (29). This change is particularly helpful to residents who are enrolled in a Master's in Science (MS) program as school lockdowns have halted most if not all research activities. Changes in CODA-recommended graduation minimums for the Class of 2022 remain to be seen.

Support of the AAE to Postgraduate Education

Staying true to their commitment in supporting endodontic education, the AAE through its Committee on Educational Affairs organized a virtual lecture series for endodontic residents in North America. This is in addition to the COVID-19 related webinars that can be accessed free of charge by the public. The lectures spanned various advanced endodontic topics for 7 weeks. The lectures, which were delivered mostly by program directors or educators, served two purposes: (1) to continue educating the residents and (2) to comply with CODA's standards for curriculum and program duration even during the restrictions on in-person activities. CODA would eventually modify its advanced specialty education in endodontics standards for the Class of 2020, but at the start of the pandemic's activity restrictions, endodontic program directors were uncertain on how to comply with CODA's standards. This was especially true for most programs that barely had 3 months left before their senior residents would graduate from their 24-month programs.

The AAE provided the virtual lecture links for the participants to pre-register for the lecture series (30). The attendance and log time of the participants were communicated by the AAE to the program directors, who used the residents' participation time in the lectures as their official attendance record. Each lecturer was given at least 90 min to teach. In April 2020 when the virtual lecture series started, there were a total of 622 endodontic residents in North America. Some schools or residents did not participate in the lecture series; however, from the AAE's attendance record, over 300 individuals pre-registered for each lecture with unique viewers ranging from 220 to 320 during the actual lectures. The virtual lecture series continued even after the in-person activity restrictions were lifted with international speakers from outside North America participating during this period.

In addition to the AAE COVID-19 initiatives, the AAE Foundation launched a COVID-19 Relief Fund to 186 AAE resident members. A total of $93,000 was distributed to 56 endodontic programs in North America. According to the AAE Foundation, the COVID-19 Relief Grants were intended to help offset the financial impact caused by the pandemic and to provide a small token of support during a significant social and economic shift (31).

The Effects of the Temporary Modifications

Although many dental emergencies fall under the jurisdiction of endodontics, many postgraduate endodontic programs saw a great reduction in clinical care. Appointments for asymptomatic patients requiring elective endodontic procedures were postponed until further notice or until an emergency or flare-up occurred. The AAE advised patients see an endodontist only for dental emergencies, which includes severe dental pain, dental infection symptoms (i.e., bleeding, swelling) or a dental infection-related fever (32). As a result, many endodontic residents lost nearly 3 months of clinical experience. In addition, recall exams were canceled to reduce the number of non-emergent patient cases.

As the COVID-19 pandemic carried into the later months of 2020, the endodontic application cycle also saw significant changes to its process. Applicants were unable to sit for the Advanced Dental Admission Test (ADAT); as a result, applicants were not required to have an ADAT score for the 2020–2021 application cycle. Postgraduate endodontic programs held interviews remotely over online teleconferencing applications.

Return to Practice

The ADA released a “Return to Work Interim Guidance Toolkit” in April 2020 (33).

Modifications to Clinical Practice

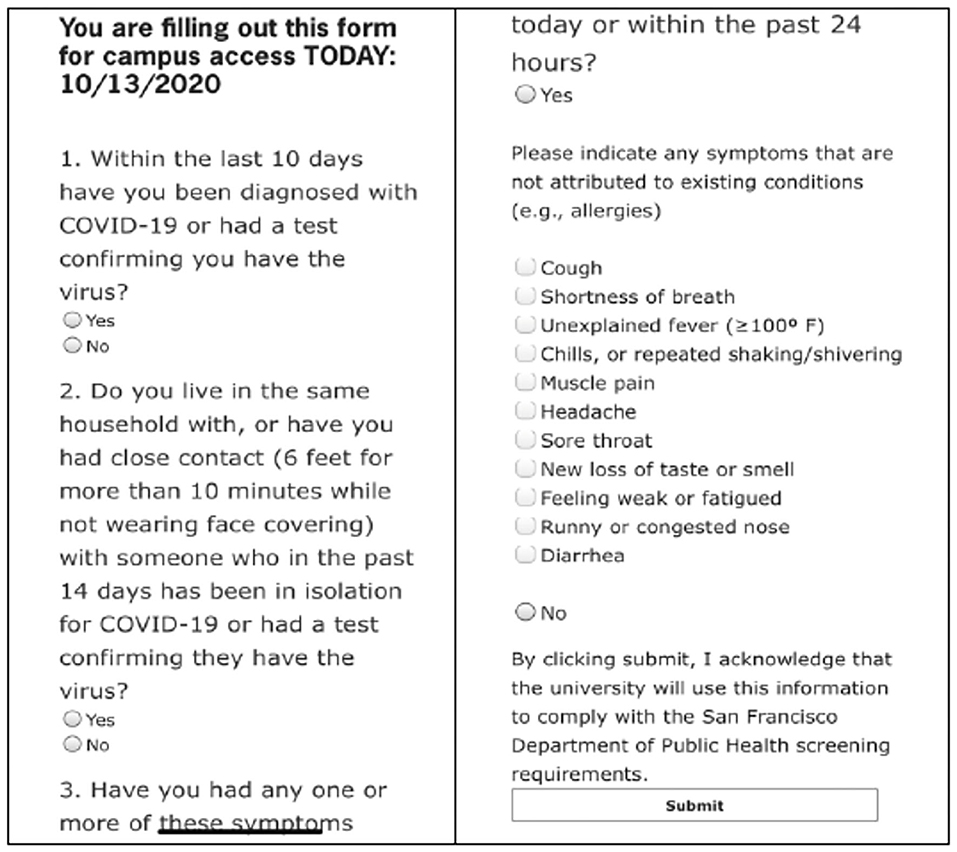

Patient and provider monitoring has changed vastly since the onset of COVID-19. Patients and providers are screened for COVID-19 symptoms prior to their appointments (Figure 2 with example of screening questions) (34). Some offices and programs have required their patients to obtain COVID-19 tests with a negative result within 2–5 days of their dental appointment. Many providers will record a patient's temperature as part of the screening process in addition to a questionnaire when the patient arrives for their appointment. As patients arrive, they are asked to socially distance in the waiting room and that they wear masks. Some offices or programs have asked patients to wash their hands and perform an oral disinfecting rinse (i.e., hydrogen peroxide, chlorhexidine, Listerine®) prior to being seated in the dental chair.

Although the ADA recommends that dental providers use universal precautions in patient care, the use of National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)-approved or tested N95 masks, fluid impervious gowns, face shields, and hair coverings has become more prevalent. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, it was recommended that all aerosol-generating procedures (except for true dental emergencies) be delayed. The practice of cleaning chairs, operatories, and instruments still follow pre-existing universal protocols and may even extend to other areas outside of clinical practice, including disinfection of doors, chairs, and other items in bathrooms and waiting rooms (35).

Timeline and Capacity Limitations for Clinical Activities

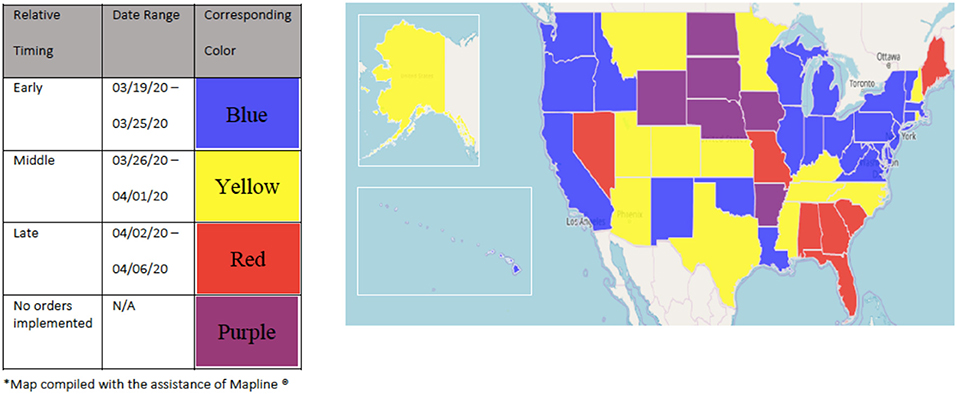

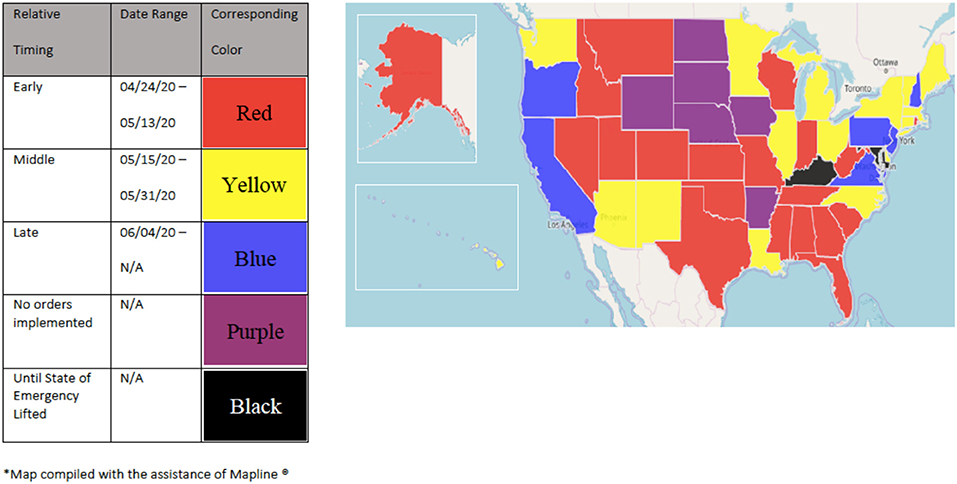

Dental offices and schools are subject to scrutiny at the state and local levels; as a result, “stay-at-home” and “re-opening” dates varied considerably across the United States. Some states installed “re-opening” plans that were predicated on the numbers of new and active cases of COVID-19 infections. These metrics therefore defined which businesses and institutions were considered essential to the public and also defined the capacity by which these practices could operate. While most states enforced “stay-at-home” orders, some states such as Arkansas, Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming held off on any orders (36). Figure 3 depicts the early, middle, and later dates when states declared “stay-at-home orders” and ceased most operations. Figure 4 depicts the early, middle, and later dates when states “re-opened.” Figure 5 depicts the early, middle, and later dates when states declared that dental practices could begin “normal” operations following public health guidelines (37–39). Clinical operations at dental schools similarly followed local public health guidelines; the number of patients seen in these settings was limited by the number of people allowed in the buildings according to social distancing guidelines. As a result, some clinics were not able to operate at their full capacity.

Recommendation and Conclusion

This article serves as a general historical account of COVID-19 and its effects on postgraduate endodontic programs in the United States. Further studies are required to identify quantitative data of COVID-19 effects on postgraduate programs, especially the effects on the classes of 2020, 2021, and 2022. In addition, this study may serve as insight for future educational operations to improve student and resident experiences and improved patient outcomes in the event of a future outbreak of infectious disease.

The COVID-19 pandemic, while debilitating, has revealed the adaptability and resourcefulness of many institutions. Online delivery of educational content is not a new concept with distinct advantages even in a healthcare profession such as dentistry (40). It was readily embraced during these challenging times, but it also highlighted some obstacles, especially during the early weeks of the COVID-19 shutdown. The most frequently encountered obstacles were difficulties experienced by both educators and students in adjusting to different online learning styles, having to perform responsibilities at home, and poor communication or lack of clear directions from educators (41). Generational gaps were evident in the early stages in adopting distance learning; however, the user-friendly interface of many of the virtual communications platform continue to evolve to facilitate ease of use.

In the midst of the explosion of virtual education, we have learned that both synchronous and asynchronous delivery of educational content may play a role in the future of dental education curricula. Educators should therefore continuously adapt to situations that may affect their programs, residents, or students. While the distance learning model has been successful in continuing the delivery of dental educational content, the future psycho-social effects and more tangible effects such as board examination scores are yet to be determined. Further studies are indicated to quantitate these long-term effects of COVID-19. In the meantime, we recommend that individuals and institutions alike remain flexible and embrace technological advances in these and future times of duress to assure that future dental professionals can competently and safely treat patients.

Author Contributions

BA was the first writer and primary researcher. JG contributed to insight on the AAE's support of Postgraduate Endodontic programs. JC assisted in editing and feedback. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. World Health Organization (2020). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

2. Blanton PL. Perspectives on Pandemics (1918-2020): What Does History Teach Us? (2020). Available from: https://www.acd.org/about-us/history/

3. Requirements for Recognition of Dental Specialties and National Certifying Boards for Dental Specialists. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association (2018).

4. Why See an Endodontist? Available from: https://www.aae.org/patients/why-see-an-endodontist/whats-difference-dentist-endodontist/

5. CODA. COVID-19 Updates. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/coda/accreditation/accreditation-news/covid-19-updates

6. Endodontic Programs. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/coda/find-a-program/search-dental-programs#t=us&sort=%40codastatecitysort%20ascending&f:@programnamesubl_coveofacets_1=[Endodontics]

7. New York Laws & Rules. American Dental Association (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Education%20and%20Careers/Files/New_York_Licensure.pdf?la=en

8. Dental Licensure By State Map. American Dental Association (2021). Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/education-careers/licensure/dental-licensure-by-state-map

9. Dental Standards. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/dental-standards#:~:text=The%20ADA%20is%20the%20accredited,106%20Dentistry%20(TC%20106)

10. Presidents and History of the ADA. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/about-the-ada/ada-history-and-presidents-of-the-ada

11. Specialty and Association History. American Association of Endodontists. Available from: https://www.aae.org/specialty/about-aae/aae-history/specialty-association-histories/

12. CODA Accreditation. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/coda/accreditation/about-us/mission-vision-values

13. Harcourt J, Tamin A, Lu X, Kamili S, Sakthivel SK, Murray J, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from patient with coronavirus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. (2020) 26: 1266–73. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200516

14. Holshue MDC, Lindquist S, Lofy K, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. New Engl J Med. (2020) 382:929–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191

15. Soucheray S. Coroner: First US COVID-19 death occurred in Early February. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disesase Research and Policy (2020).

16. President Trump Declares State of Emergency for COVID-19. (2020). Available from: https://www.ncsl.org/ncsl-in-dc/publications-and-resources/president-trump-declares-state-of-emergency-for-covid-19.aspx

17. ADA Recommending Dentists Postpone Elective Procedures. (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/march/ada-recommending-dentists-postpone-elective-procedures

18. ADA Develops Guidance on Dental Emergency/Non-Emergency Care. (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/march/ada-develops-guidance-on-dental-emergency-nonemergency-care

19. CODA Asks Accredited Dental Programs for Details on COVID-19 Response. (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/april/coda-asks-accredited-dental-programs-for-details-on-covid19-response

20. Statement on Universal Masking of Staff Patients and Visitors in Health Care Settings. Washington, DC: The Joint Commission (2020).

21. Versaci MB. Extraordinary Contributions in Extraordinary Times. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association (2020).

22. Ather A, Patel B, Ruparel N, Diogenes A, and Hargreaves K. Coronavirus diseaes 19 (COVID-19): implications for clinical dental care. J Endod. (2020) 46:584–95. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008

23. Langella J, Magnuson B, Finkelman M, and Amato R. Clinical response to COVID-19 and utilization of an emergency dental clinic in an academic institution. J Endod. (2020) 47:566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.11.025

24. Galicia J, Mungia R, Taverna M, Mendoza M, Estrela C, Gaudin A, et al. Response by endodontists to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international survey. Front Dental Med. (2021) 1:24. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2020.617440

25. Statement to CODA Site Visitors. (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/covid19_sitevisite_statement.pdf?la=en

26. CODA Guidance on Interruption of Education Related to COVID-19. (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/Further_CODA_Guidance_Interruption_Education_Related_COVID19.pdf?la=en

27. Commission on Dental Accreditation Guidelines for Reporting an Interruption of Education During COVID-19. (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/COVID-19_Guidelines_Reporting_Interruption_of_Education_Programs.pdf?la=en

28. Guidance Document: Temporary Flexibility in Accreditation Standards to Address Interruption of Education Reporting Requirements Resulting from COVID-19 for the Class of 2020. (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/ENDO_Flexibility_4_20.pdf?la=en

29. Guidance Document: Temporary Flexibility in Accreditation Standards to Address Interruption of Education Reporting Requirements Resulting from COVID-19 for the Class of 2021. (2020). Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/Endodontics_Flexibility_Class2021_13Oct2020.pdf?la=en

30. New Distance Learning Opportunities for Residents. (2020). Available from: https://www.aae.org/specialty/2020/08/05/distance/

31. COVID-19 Relief Grant. (2020). Available from: https://www.aae.org/foundation/covid19/#:~:text=Graduating%20residents%20are%20recognized%20as,who%20is%20graduating%20in%202020

32. Have a Dental Emergency? Go to an Endondontist First Not Emergency Room or Urgent Care. (2020). Available from: https://www.aae.org/specialty/2020/03/30/have-a-dental-emergency-go-to-endodontist-first-not-emergency-room-or-urgent-care/

33. Return to Work Interim Guidance Toolkit. (2020). Available from: https://f3f142zs0k2w1kg84k5p9i1o-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/04/ADA_Return_to_Work_Toolkit.pdf.

34. Return to Work Health Screener. (2020). Available from: https://sfdental.pacific.edu/employees/ReturnToWork/Login.aspx?ReturnUrl=%2femployees%2fReturnToWork%2fHealthScreener.aspx

35. Estrich C, Mikkelsen M, Morrissey R, Geisinger M, Ioannidou E, Vujicic M, et al. Estimating COVID-19 prevalence and infection control practices among US dentists. J Am Dental Assoc. (2020) 151:815–24. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.09.005

36. Governors Prioritize Health for All. (2020). Available from: https://www.nashp.org/governors-prioritize-health-for-all/

37. COVID-19 State Mandates and Recommendatoins. (2020). Available from: https://success.ada.org/en/practice-management/patients/covid-19-state-mandates-and-recommendations?utm_source=adaorg&utm_medium=covid-statement-200401&utm_content=stateaction&utm_campaign=covid-19&_ga=2.73968082.1927821369.1587415597-74982775.1584336205&fbclid=IwAR2Feq96fEgR8PRrLjHo_a1cJnbcLR9tAERday98AYkWhXWwCDBLVxQJlNw

38. COVID-19 State Mandates and Recommendations. (2020). Available from: https://governor.ky.gov/covid19

39. COVID-19 Pandemic Orders and Guidance. (2020). Available from: https://governor.maryland.gov/covid-19-pandemic-orders-and-guidance/

40. Maresca C, Barrero C, Duggan D, Platin E, Rivera E, Hannum W, et al. Utilization of blended learning to teach preclinical endodontics. J Dental Educ. (2014) 78:1194–204.

Keywords: COVID-19, endodontic, American Association of Endodontists, Commission on Dental Accreditation, American Dental Association, asynchronous, distance learning, dentistry

Citation: Aboubakare B, Chen J and Galicia JC (2021) The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Postgraduate Endodontic Programs in the United States. Front. Dent. Med. 2:628540. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2021.628540

Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 05 March 2021;

Published: 15 April 2021.

Edited by:

Yusuke Takahashi, Osaka University, JapanReviewed by:

Amber Ather, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, United StatesNileshkumar Dubey, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Ayako Washio, Kyushu Dental University, Japan

Copyright © 2021 Aboubakare, Chen and Galicia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Johnah C. Galicia, jgalicia@pacific.edu

Bianca Aboubakare

Bianca Aboubakare James Chen2

James Chen2 Johnah C. Galicia

Johnah C. Galicia