95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

COMMUNITY CASE STUDY article

Front. Conserv. Sci. , 02 April 2025

Sec. Conservation Social Sciences

Volume 6 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2025.1553549

This article is part of the Research Topic Advancing the Science of Environmental Justice in the International Wildlife Trade View all 10 articles

Michelle Anagnostou1*

Michelle Anagnostou1* Celine Boon Yuan Ng2

Celine Boon Yuan Ng2 Robin Cepeda3

Robin Cepeda3 Jessica Grace Huiyi Lee4

Jessica Grace Huiyi Lee4 Adrian Hock Beng Loo5

Adrian Hock Beng Loo5 Peng Xiong Keith Ng5

Peng Xiong Keith Ng5 Keanu Sitjar6

Keanu Sitjar6 Hui Min Steffi Tan2

Hui Min Steffi Tan2 Yong Jen Tang7

Yong Jen Tang7 Wai Kit Ting4

Wai Kit Ting4Despite gaining traction in international forums, such as in global climate action spheres, the potential of youth in contributing to a legal and sustainable international wildlife trade remains under-tapped, overlooked and underexplored. This is an emerging topic of discussion, as Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) were first encouraged to explore opportunities to engage youth during the seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties in 2016. In April 2024, the first meeting of the CITES Global Youth Network was held in Singapore, where concrete actions were collaboratively identified by youth from around the world. This paper aims to answer the following question: how may youth contribute to achieving the goals of the CITES Strategic Vision by 2030? As a first step in answering this question, this community case study collates the diverse voices of members of the CITES Global Youth Network. Using a backcasting perspective, and the CITES Strategic Vision as our desired future by 2030, we outline how youth may contribute to achieving the Vision, and offer ideas of how youth can be supported. We argue that youth are underrepresented voices in wildlife trade decision-making, and that their deeper and more meaningful engagement in CITES processes has significant potential to improve outcomes for a legal and sustainable wildlife trade in the long-term and fundamental to achieving intergenerational equity as envisioned by the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an international agreement that aims to ensure that the trade in wild animals and plants is not harmful to their survival. Established in 1975, CITES has grown to a membership of 185 Parties and provides a framework for regulating the trade of over 40,000 species. The Convention remains critically important, with recent reports indicating that illegal wildlife trade threatens over 4,000 species and occurs in at least 162 countries (UNODC, 2024). Of the 4,000 trafficked species, an estimated 3,250 are listed in the CITES Appendices (UNODC, 2024). By setting wildlife permitting and management guidelines and encouraging global cooperation, CITES safeguards endangered species from overexploitation while promoting sustainable trade practices that benefit biodiversity and local economies. There are massive challenges to achieving the goals of CITES, as it requires balancing the protection of wildlife with the demands of global trade, economic development, diverging cultural values, and sometimes organised crime involvement in CITES noncompliance.

Power imbalances in broader global governance are also prevalent in the realms of conservation and wildlife trade governance, influencing decision-making processes, resource allocation, and the enforcement of regulations. Many marginalised voices are not adequately represented in wildlife trade decision-making, which affects the efficacy and fairness of these decisions. For example, CITES has been criticised as being structurally dominated by Parties and organisations that are “Western, wealthy, and urbanized” (‘t-Sas-Rolfes et al., 2024). One type of marginalised voice is that of youth. Youth are thought to be essential for achieving sustainability goals, as they are creative, optimistic, dynamic, and innovative (including technologically) (Ekka et al., 2022). Youth-driven initiatives are a powerful force for a greener future. Youth can be effective agents of change for spreading awareness of complex sustainability and justice issues, and for mobilising communities (Kumar, 2023). Actively involving youth in sustainability efforts may instill a sense of responsibility and leadership in young individuals (Kumar, 2023). Challenges to youth involvement include a lack of: comprehensive education; resources and funding; representation and inclusion; support and mentorship; and political and policy support (Kumar, 2023). As the generation that will bear the long-term consequences of today’s actions, finding ways to meaningfully involve youth in wildlife trade decision-making will help ensure that efforts are forward-looking and inclusive of future needs.

In the field of future-oriented studies, forecasting is a commonly used approach. However, forecasting predicts likely futures based on dominant past and existing trends. This means that it uses trends which may be part of the problem, and therefore insufficient in terms of the level of disruption required to achieve a desired scenario. Backcasting, on the other hand, first identifies desirable futures and then works backwards to determine the feasibility of that future and the steps required to reach it. Backcasting is valuable for studying ways to overcome long-term complex sustainability issues. According to seminal work by Dreborg (1996), backcasting is favorable when: (1) the problem is complex, affecting many sectors and levels of society; (2) there is a need for major change; (3) dominant trends are part of the problem; (4) the problem is largely a matter of externalities; and (5) the time horizon is long enough to allow considerable scope for deliberate choice. Therefore, backcasting is a useful approach to understanding a future with a legal and sustainable international wildlife trade.

CITES Parties were first encouraged to explore opportunities to engage youth during the seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties in 2016 (see Conf. 17.5 Rev. CoP18 on Youth Engagemen; CITES, 2016). Parties and the CITES Secretariat were invited to work with universities, youth groups, and other relevant associations and organisations, to create educated, engaged, incentivised, and empowered youth that can inform CITES decision-making processes. Parties and observer organisations were also invited to include youth delegates on official delegations and provide learning opportunities at CITES meetings. At the 77th meeting of the CITES Standing Committee in Geneva, Switzerland, in November 2023, the Committee supported Singapore’s efforts in establishing the CITES Global Youth Network (CGYN). In February 2024, CITES sent a Notification to the Parties concerning the Establishment of the CITES Global Youth Network, published at the request of Singapore. Parties and observers were encouraged to nominate youths affiliated with their organisations to attend the CITES Youth Leadership Programme 2024.

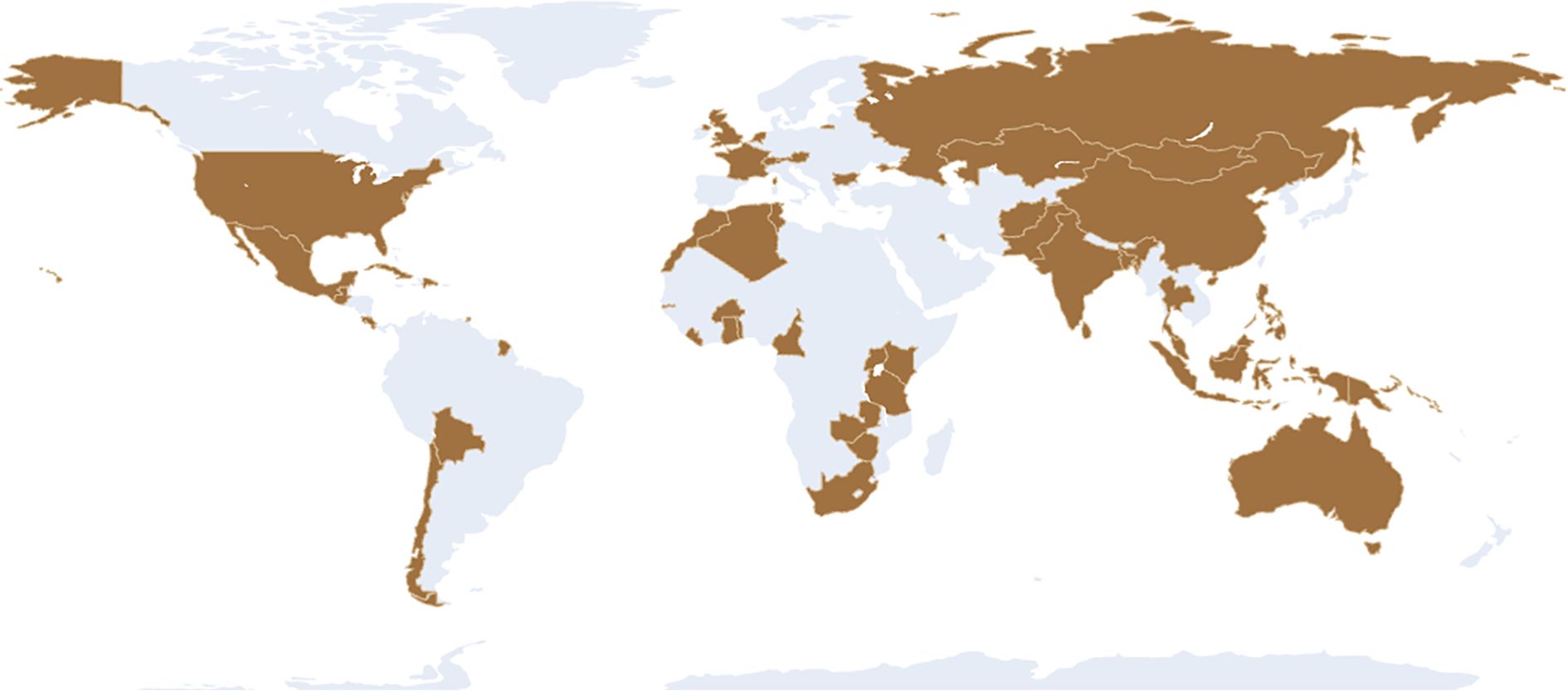

From April 22 to 25, 2024, the CITES Global Youth Network held its inaugural Youth Leadership Programme (CYLP) in Singapore. Forty-one youths between the ages of 18 to 30 attended the symposium in person, traveling from 31 unique countries to participate and help shape the future of the Network (see Table 1; Figure 1). External donor funding enabled in-person representation from low- and middle-income countries. The Programme established diverse sub-groups within the broader Network during the four-day in-person programme to take the lead on priority actions under each of these pillars. The five pillars are: Research and Innovation, Governance, Communications, Education and Public Awareness (CEPA), Networking and Collaboration, and Capacity Building. The Research & Innovation team (i.e., the authorship team) co-developed this study through in-person and virtual brainstorming and discussion sessions.

Table 1. List of countries represented by youth at the 2024 CITES Youth Leadership Programme in Singapore.

The programme included presentations from CITES leaders, training on a mock Conference of the Parties (CoP), field trips to the Centre for Wildlife Forensics and Centre for Wildlife Rehabilitation, an illegal wildlife trade “Amazing Race” at the Singapore Zoo, a mock CoP, and multiple collaborative sessions dedicated to facilitated discussions and reflections. CYLP provided multiple opportunities for youth to connect, collaborate, and collectively shape the Network’s mission, vision, and strategic roadmap across the five pillars. Youth were divided into four groups, each with multiple regional representatives to cultivate the sharing of diverse perspectives. Each group had a facilitator to foster active participation and offer constructive feedback, and all ideas were noted down by independent scribes. A final report was prepared based on the points discussed throughout CYLP, which was reviewed and approved by CGYN advisors and members.

A key feature of CGYN is the composition of the youth who were already working in CITES Management Authorities upon joining, or in related vocations that address wildlife trade legality and sustainability, such as regulatory, enforcement, research, education/awareness, or policy-related professions. Since its inception, there has been a close working relationship between CGYN and the CITES Secretariat, CITES Management Authorities, and relevant non-governmental organisations. This cooperative approach maximises collective impact for sustainable wildlife trade by aligning joint efforts with CITES principles and resolutions. This paper sets a path not only for future leaders but also the current leaders to better understand the need for an equitable and shared future. Lastly, as a collective output by a team of youths, this paper exemplifies the promises of youth involvement and engagement in wildlife trade issues.

Engagement and empowerment of youth have been gaining traction in other international forums, such as YOUNGO, the official youth constituency of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and the Global Youth Biodiversity Network (GYBN), the official group for the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). However, the role that youth can play in supporting efforts to achieve a legal and sustainable international wildlife trade remains an under-discussed and understudied topic. This community case study seeks to address this knowledge gap. Specifically, this study uses a “backcasting” approach to outline the necessary steps for realising the CITES Strategic Vision by 2030, with a particular focus on the contributions of youth toward achieving this Vision. The key research question that this paper addresses is: how can youth contribute to achieving the goals of the CITES Strategic Vision by 2030? The future scenario we used for the present study was centered around the CITES Strategic Vision 2021-2030 (CITES, 2021), as it already has the support of CITES member states and global leaders in wildlife trade governance. We also highlight the challenges for youth empowerment in CITES processes, and the importance of overcoming the challenges to achieve intergenerational equity. As this study serves as an initial step in understanding the role of youth in achieving a legal and sustainable wildlife trade, we have developed actionable strategies to bridge the gap between the present and our desired outcome (i.e., the goals of the CITES Strategic Vision). However, while we recognize the importance of establishing time intervals for each milestone, this remains a crucial next step for future research.

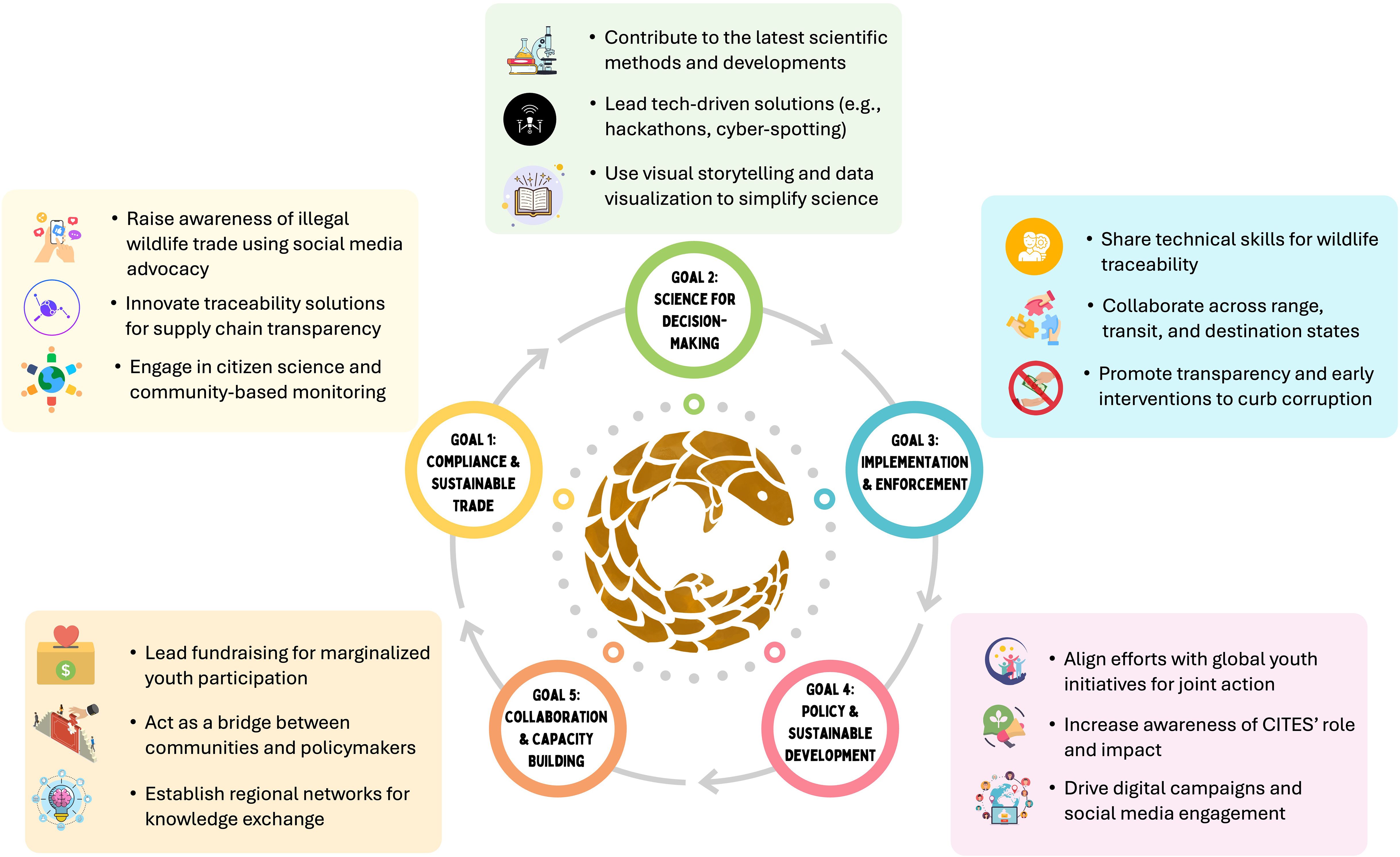

CITES’ Vision Statement is: “By 2030, all international trade in wild fauna and flora is legal and sustainable, consistent with the long-term conservation of species, and thereby contributing to halting biodiversity loss, to ensuring its sustainable use, and to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (CITES, 2021).” The CITES Strategic Vision 2021-2030 includes a number of goals, objectives, and indicators. The indicators in the Vision are the responsibility of CITES parties. However, CGYN has envisioned clear actionable objectives for youth to support achieving the goals of the Vision. The results first outline the values of the Network and how they align with the CITES Strategic Vision, followed by outlining the various ways in which youth can contribute to legal and sustainable wildlife trade, using the Convention’s strategic goals and objectives as a guiding framework. While the discussion highlights ideas from current CGYN members, youth contributions to the goals of the CITES Strategic Vision extend far beyond the Network’s membership. Young people worldwide can take on leadership roles in promoting a legal and sustainable wildlife trade (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Visual Representation of youth contributions to the five pillars of the CITES Strategic Vision.

To achieve Goal 1, in their roles across sectors of society, including public, private, non-governmental, and inter-governmental organisations, youth can support Parties in compliance with their obligations under the Convention through the adoption and implementation of appropriate legislation, policies, and procedures. Achieving compliance with the Convention necessitates that wildlife traders and users have a thorough understanding of relevant laws and policies. Engaging youth is widely recognised as a critical step in wildlife conservation (Sithole et al., 2024). However, many young people remain unaware that the illegal wildlife trade is occurring in their own countries or regions, and the vital role of CITES in combating it. This lack of awareness allows the issue to grow unchecked, especially as smaller, everyday seizures often go unreported or are deemed unnewsworthy. This in turn hinders youth capacities to innovate and drive meaningful change. CGYN can address this gap by educating and raising awareness about illegal wildlife trade at local, regional, and global levels, empowering youth to curb its growth. By fostering awareness, the Network has the potential to reduce demand for illegal wildlife products within a generation and inspire future leaders to champion sustainable trade practices.

Young people’s digital literacy enhances their connectivity and amplifies the voices of youth from low- and middle-income countries, and/or historically marginalised communities, empowering them as credible advocates for policy change (McPherson, 2007). This capability can assist CITES Parties in advancing their agendas, leveraging social media for advocacy, and addressing misinformation about wildlife conservation and sustainable use. Youth-led innovation occurs when young people, “instigate potential solutions to a problem, often one that they have identified or defined themselves, and take responsibility for developing and implementing a solution” (Sebba et al., 2009). Youth can directly support supply chain transparency both by developing innovative solutions to traceability (see Goal 3) and by increasing consumer awareness. Youth can lead creative and innovative legal awareness and public education campaigns by sharing information about CITES-listed species, promoting their conservation, explaining how wildlife products are sourced, and advocating for sustainable fashion trends. Youth’s mastery of social media and technology offers a transformative platform to inspire global action, rally support, and promote awareness in addressing wildlife trade issues. Social media campaigns led by youth have the potential to amplify voices, expose illegal activities, and educate the public on the importance of sustainable trade practices. For instance, social media platforms such as, Instagram and TikTok can be leveraged to create compelling narratives and visually engaging content that highlights the plight of CITES-listed species, fostering a sense of urgency and collective responsibility among diverse audiences (PwC, 2023; GITOC, 2024). The active engagement, content sharing, and widespread adoption of social media by young users play a crucial role in driving an online platform’s growth and viral success. Establishing a strong stance against wildlife exploitation can significantly enhance an online platform’s ethical integrity. Social media shapes the formation of young people’s identities (Pérez-Torres, 2024), and therefore in turn, may be a powerful tool to instill long-term values of wildlife protection among users, and set the tone for zero tolerance of wildlife exploitation.

Beyond awareness, public engagement in citizen science initiatives has proven to be a proactive approach to combating illegal wildlife trade. By harnessing the power of crowdsourced data, young volunteers can participate in passive surveillance efforts, reporting suspicious activities such as the sale of endangered species or products derived from them on digital marketplaces. A notable example is the use of mobile applications that allow users to upload geotagged photographs of suspected wildlife crimes, which are then analysed by experts to support law enforcement actions (Padma, 2022). While engaging in wildlife photography to document illegal trade is a commendable endeavour that can significantly contribute to conservation efforts, it is essential to recognize and address the personal risks involved. These risks include potential confrontations with traffickers, legal implications, and exposure to hazardous environments. Youth must ensure that their safety is not compromised prior to taking any action by themselves. Before embarking on any assignment, a risk assessment and thorough research is crucial, such as understanding the area, species involved, and the nature of the illegal activities to anticipate potential dangers. Additionally, there is a need to understand local laws and regulations related to wildlife trade and photography. This knowledge can prevent unintentional legal violations and inform them about their rights. Furthermore, ensuring anonymity and maintaining a well-structured safety plan is critical for wildlife photographers documenting illegal trade. Operating discreetly by blending into the environment, using inconspicuous equipment, and avoiding overt documentation in high-risk areas can minimize personal exposure. Additionally, safeguarding personal information, such as obscuring metadata from images and limiting identifiable online traces, reduces risks of retaliation. Collaboration with established conservation organizations such as TRAFFIC and WWF could help enhance security by providing legal and logistical support, ensuring that the evidence collected is properly handled and acted upon.

Additionally, youth must be aware of legal protections under international and national frameworks designed to safeguard young environmental defenders. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recognizes the right of youth to participate in environmental advocacy while ensuring their safety from threats and retaliation (UNGA, 1989; UNEP, 2021). Similarly, the Escazú Agreement, a regional treaty in Latin America and the Caribbean, establishes legal protections for environmental defenders, emphasizing access to justice and safety mechanisms (ECLAC, 2018). At the 16th meeting of the CoP of the CBD in Colombia (2024), discussions on strengthening protections for environmental defenders, including young conservationists, highlighted the urgent need for legal frameworks that ensure their safety in biodiversity activism (Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Colombia, 2024). While not all countries have specific laws protecting young conservationists, organizations such as the Environmental Justice Foundation and Amnesty International also provide legal assistance, and publicly available risk assessment tools to support advocacy for environmental defenders. Youth can also benefit from initiatives such as the National Geographic Young Explorers program, which equips emerging conservationists with the skills and resources needed for fieldwork in challenging environments. Additionally, maintaining a structured safety protocol (e.g., emergency contacts with trusted individuals, regular check-ins, and contingency plans) enhances protection while reinforcing responsible investigative practices. These proactive measures, combined with legal awareness and institutional support, empower youth to contribute meaningfully to conservation while ensuring their security in the field.

Moreover, youth-driven innovation can extend to creating educational tools and community-based programs that align with CITES Goal 1. For instance, university-led hackathons focusing on wildlife conservation can generate novel solutions to address gaps in monitoring and enforcement. Partnerships between youth organisations and conservation bodies can also facilitate training programs, equipping young individuals with the skills needed to engage effectively in sustainable trade advocacy and policy development. Through initiatives that combine technology, community engagement, and policy advocacy, youth can drive progress toward ensuring trade in CITES-listed species is conducted in full compliance with the Convention, safeguarding their conservation and sustainable use.

To be most effective in contributing to Goal 1, youth will need to be supported through gaining relevant knowledge and expertise on CITES regulations, including non-detriment findings (NDFs) and how they implicate trade and domestic contexts for wildlife trade law and policy. Indicators of this include that: youth are employed in CITES Management and Scientific Authorities and enforcement focal points; youth voices are heard regarding amendments to the Appendices that correctly reflect the conservation status and needs of species; and that youth are involved in multiple stages of efforts to improve the conservation status of CITES-listed specimens, develop national conservation actions, and support their sustainable use and promote cooperation in managing shared wildlife resources.

Goal 2 states that Parties’ NDFs must be based on the best available scientific information and their determination of legal acquisition is based on the best available technical and legal information. Youth can support this objective when young staff are involved in the writing of NDFs that are submitted by Parties; and educated on legal acquisition findings as per their national regulatory framework, as recommended by Resolution Conf. 18.7 (Rev. CoP19). Young researchers can often contribute the latest methods and developments in their fields and an understanding of the perspectives of diverse communities due to the increasing internationalisation of research careers (Jørgensen et al., 2019). Goal 2 requires that Parties have sufficient information to make listing decisions that are reflective of species conservation needs. To this end, youth can conduct collaborative and interdisciplinary research, including leading and participating in population surveys or other analyses in exporting countries to better understand the population status of Appendix-I and -II species, including trends and impacts of trade and recovery efforts. Youth can actively contribute to scientific efforts by reporting wildlife populations and trade data, monitoring online marketplaces for illegal wildlife trade (i.e., “cyber spotters”), and tracking wildlife sightings, trafficking, and habitat disturbances. Empowering youth-driven innovation is key to advancing sustainability goals, while simultaneously building the skills and leadership capacities of young people to inspire and guide future generations (Bastien and Holmarsdottir, 2017). Youth can pilot and introduce new technologies for species monitoring and data collection. Hackathons for technology-related solutions for illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade may be valuable examples of harnessing youth capacities.

For youth engaged in documenting suspected illegal wildlife trade (such as on iNaturalist) and/or cyber-sleuthing efforts, prioritizing content-sharing protocols is essential to prevent misinformation and protect themselves from potential legal or digital threats. Ensuring that findings are reported through credible channels, using encrypted communication, and verifying authenticity before dissemination strengthens the impact of their work. While social media platforms play a powerful role in amplifying awareness, the ultimate goal is not merely virality but fostering meaningful action against illegal wildlife trade. Raising public consciousness must align with tangible efforts to safeguard biodiversity, reinforcing the urgency of combating trafficking networks and preserving ecological integrity. While cyber-sleuthing can enhance wildlife trade monitoring, it is crucial to ensure that efforts do not inadvertently make species more vulnerable to exploitation. Cyber spotters must work discreetly alongside ecologists and adhere to ethical wildlife photography practices to prevent unintentionally exposing species locations to poachers or traffickers. The principle of “do no harm” should guide all investigative efforts, prioritizing the protection of wildlife and social equity over publicizing findings (see Roe et al., 2020). By integrating ethical guidelines with conservation science, cyber-sleuths can contribute valuable intelligence while safeguarding the very species they aim to protect.

The integration of advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), further enhances the capacity to detect and disrupt illegal wildlife trade. Youth with coding and data science skills can contribute significantly to these efforts by developing or improving AI models that mine data from online platforms, identify wildlife trafficking networks, and classify illegal wildlife products. Recent advancements include the use of image recognition software to differentiate between legal and illegal wildlife goods, as well as predictive modelling to identify trafficking hotspots (Xu et al., 2019; Kulkarni and Di Minin, 2023; Zhang, 2024). Youth can contribute more efficiently by developing or enhancing these AI technologies, leveraging their expertise in coding, data science, and user-centered design to create tools that are not only precise but also accessible to a broader range of users. For instance, young technology enthusiasts can collaborate with conservation organisations to optimise image recognition algorithms for accuracy or to design user-friendly interfaces for reporting wildlife crimes. Initiatives like the AI Guardian of Endangered Species further highlight opportunities for youth to participate in the deployment and improvement of automated systems that screen vast amounts of online content, flagging potential violations for investigation by authorities (Zhang, 2024).

Goal 2 also incorporates objectives that Parties will cooperate in sharing information and tools relevant to the implementation of CITES. Youth can be powerful vessels to break down political barriers to information sharing between Parties within CGYN (see Figure 3). Countries are often restricted from sharing information due to political barriers, limiting opportunities for cooperation on illegal wildlife trade issues (Anagnostou, 2024). However, youth (depending on their roles) are often not bound by the same diplomatic restrictions and can freely exchange ideas, support, knowledge, and solutions. Through their international networking, online platforms, and collaborative initiatives, youth may leverage their unique positions to promote dialogue and understanding as a global community. Youth can establish networks of contacts across borders, including source, transit, and destination locations, and sectors to have cross-cutting, inclusive discussions and facilitate the creation of partnerships. Youth can develop channels for sharing information amongst each other that are relevant to the implementation of CITES, such as reports, scientific papers, shared databases, and data analysis/visualisation software. This paper is in itself a prime example of the above.

Figure 3. Geographic distribution of countries with youth delegates that have been formally nominated and invited to the 2025 CITES Global Youth Summit.

In addition, CGYN has identified Communication, Education, and Public Awareness (CEPA) as one of its main pillars for empowering youth to address wildlife trade challenges. CEPA is a widely recognised tool endorsed by international conservation frameworks, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), to bridge the gap between complex scientific data and actionable conservation strategies (Hesselink et al., 2007; Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), 2022). Youth are uniquely positioned to leverage CEPA principles through innovative and adaptive approaches to science communication. Recent studies highlight the importance of visual storytelling and data visualisation in making scientific information accessible and actionable. Youth can harness this potential by creating infographics, interactive dashboards, and multimedia content that distill critical conservation data into compelling formats.

Exposure to wildlife and protected areas through targeted ecotourism opportunities for youth is important to instill a balanced view of wildlife, especially with increasing urbanisation (Seddon and Khoja, 2003). In addition, formal education of wildlife and conservation in school and participation in environmental clubs are critical, including supporting access for girls (Kioko and Kiringe, 2010; Nadeson and Barton, 2014). Youth in wildlife conservation volunteering and educational programs can also share their knowledge with parents/older adults and contribute to community-wide change (Kaukonen, 2014). However, youth engaging in political activities for broader-scale social change may be more challenging (Rendell and Kantamaturapoj, 2021).

To be most effective in their contributions to Goal 2, youth could be supported through facilitating access to research opportunities, and capacity building of how to generate relevant data for NDFs, and relevant scientific data analysis software (e.g., NVivo; Geographic Information System (GIS); Open source intelligence (OSINT); crime analysis techniques). Research training opportunities can be provided by research institutions through specialized modules and certificate programs, or pursued independently by youth through self-driven learning initiatives. Institutions, such as universities, think tanks, non-governmental organisations, inter-governmental organisations, and public sector and enforcement agencies, can all be involved in providing credible, structured curricula online and in-person. However, access to these learning resources may be limited by affiliation and location. Therefore, a complimentary approach is to expand the development and use of freely accessible, remote, high-quality online resources recognised by leading organisations (e.g., self-paced virtual courses, live-streamed workshops, webinars, briefs, toolkits, and other digestible formats). Youth-led initiatives, such as CGYN and other networks, can bridge the gap between formal institutional guidance and self-motivated learning. Youth may benefit from workshops to learn data analysis and ecological modelling techniques, and participatory methods for social research on livelihoods, empowering young people to support decision-making with scientifically sound recommendations. In addition, creating mentorship opportunities within CITES Authorities and related institutions where experienced scientists can guide young people in conducting and presenting research to impact CITES decisions would be valuable. Youth could also be supported with guidance on understanding relevant political contexts and possible information-sharing barriers, and how to navigate them. Finally, youth could also be present at future CoPs and able to participate in side events where Parties present information and tools relevant to the implementation of CITES.

Youth can help ensure that Parties have in place administrative procedures that are transparent, practical, coherent and user-friendly, and reduce unnecessary administrative burdens. Young staff in CITES Authorities could be trained to make use of the simplified procedures provided for in Resolution Conf. 12.3 (Rev. CoP19), and to use an electronic system for the issuance of permits. Youth with technical skills can share their skills with other youth around the world and develop innovative tools that would aid in the traceability of wildlife trade supply chains. For example, youth can be involved in the rapid detection of illegal wildlife online, and the development of mobile applications and online platforms where youth can anonymously report sightings of illegal wildlife trade, aiding enforcement agencies. Youth can also participate in community-based surveillance for illegal trade, such as through programs to train volunteers.

Youth could be presented with opportunities to attend training and capacity-building programmes, and to access information resources to implement CITES, including the making of non-detriment and legal acquisition findings, and issuance of permits and enforcement strategies. Additionally, CITES Authorities can facilitate these supports by providing internships or volunteer opportunities for youth interested in conservation enforcement, building capacity at the grassroots level. Sufficient resources are required at national and international levels to support these efforts. Youth can identify avenues to obtain funding that will advance their activities in alignment with the Convention. They can also be involved in organising fundraisers aimed at acquiring resources, such as anti-poaching patrol equipment. In addition, while changes to the legal system are likely to be in the hands of senior government officials, youth can play an advocacy role in ensuring parties recognise criminal offences relating to illegal trade in wildlife as serious crimes.

Objective 3.5 states that Parties should work collaboratively across range, transit and destination states to address entire illegal trade chains, including through strategies to reduce both the supply of and demand for illegal products. This is an area where CGYN has significant potential. Even in the Network’s early stages, ideas are being exchanged, and collaborations are being established between youth across range, transit and destination states, to address entire illegal trade chains.

Corruption is a commonly recognised driver of illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade globally (OECD, 2018). To achieve Goal 3, Parties are expected to take measures to prohibit, prevent, detect and sanction corruption. Engaging youth in integrity management, anti-corruption interventions, and proactive preventative action will likely lead to disruptive changes to global wildlife trade governance. Parties could actively engage in measures to prevent corruption, including early intervention with young staff to discourage corrupt behaviours from the outset. With guidance and support from trusted mentors, youth can also be advocates for greater transparency within their organisations. An awareness of potential risks and legal protections is crucial. Youth could be empowered to raise concerns in appropriate forums, such as ethics committees or secure anonymous reporting systems to protect privacy. Young staff could educate themselves on the organisation’s policies, relevant laws, and best practices for transparency.

To ensure youth remain safe when confronting corruption, we recommend using encrypted digital reporting tools and secure platforms (e.g., Crimestoppers), and leveraging whistleblower hotlines from reputable organizations with strong security measures, including independent anti-corruption bodies. Sensitive information on illegal wildlife trade and corruption should only be shared with trusted entities known for their integrity. Additionally, we encourage advocating for systems and technologies that minimize opportunities for corruption and misconduct in wildlife trade decision-making. Building a support network with trusted colleagues, both locally and internationally, can provide added protection, especially in environments where corruption is deeply entrenched. In such cases, youth may also be able to engage international watchdogs to apply external pressure. Finally, conducting thorough risk assessments and developing mitigation strategies is essential for ensuring safety while taking action against corruption.

In alignment with Goal 4, Parties could co-develop or otherwise support the capacity of young members of Indigenous and local communities to pursue sustainable livelihoods. CGYN members could seek to increase the number of CITES-listed species for which youth have designed/implemented relevant sustainable wildlife management policies. Youth that are cross-appointed or seconded to other multilateral youth initiatives, such as the Global Youth Biodiversity Network, can identify synergies, streamline efforts, avoid duplication, and find opportunities for joint action to achieve both the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the CITES Strategic Vision.

Furthermore, youth can lead efforts to raise global awareness of CITES’ role, purpose, and achievements. An indicator of this is an increased number of applicants to join the Youth Network due to increased interest in CITES among youth from around the world. Youth can easily and comfortably share content and information, and connect and engage on social media. As such, young leaders can spearhead communications efforts, including creating and encouraging the use of identified hashtags (e.g., #cites, #citescop19 #worldwildlifeday, etc.) on social media platforms. In this regard, young professionals may be assets as they will have a deeper understanding of trends in younger generations which could be a reason for an increase or reduction in trade demands.

Youth can be heavily involved in producing scientific research, data collection, and innovation towards the Sustainable Development Goals which can help in the crafting of policies, including providing feedback on research and policy documents from a fresh perspective (Lim et al., 2017). In addition, CITES youth could seek to increase the number of events held by the Network independent of official CITES meetings. Youth could establish a communication platform to stay on top of events, documents, learning opportunities, presentations, and Notifications to the Parties issued by the CITES Secretariat that may have a bearing on achieving the goal of CITES. To best provide these contributions, youth could be supported through invited participation in policy consultations, including for multilateral agreements that are relevant to the Convention.

Goal 5 requires that Parties and the Secretariat support and enhance existing cooperative partnerships to achieve their identified objectives. This can be achieved when youth involvement in an increasing number of intergovernmental and non-governmental organisations participate in and/or fund CITES workshops and other training and capacity-building activities where youth attendance is encouraged. This can be supported by youth-led fundraising, with guidance from the Secretariat, prioritising financial aid to youth from Indigenous and historically marginalised communities.

An additional measure of success is an increased number of cooperative actions taken by youth to prevent species from being unsustainably exploited through international trade. Youth involved in the Network and other informal connections could include alliances between CITES and other relevant international partners to advance CITES objective and mainstream conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. This can start at the grassroots level, with youth serving as a vital, accessible link to communities, helping countries engage with those living near wildlife or relying on CITES-listed species. CGYN can form regional youth chapters that work on regional conservation issues and share their work globally. There, lessons could be shared, ideas exchanged and blended, then tested and refined through ongoing improvement. CGYN will host regular webinars where youth and experts can discuss challenges, solutions, and share knowledge and resources to progress on CITES goals. Further, they can create a shared library of resources, studies, and success stories accessible to anyone working on CITES-related projects.

Through CGYN, young people can promote new and existing partnerships and collaborations, including participating in cross-sector projects such as linking the goals of CITES with other sectors such as green finance, ecotourism, or sustainable fashion, airlines, shipping companies, and logistics companies, etc. Parties and non-state organisations could develop youth activities that include CITES-related conservation and sustainable development elements. One key approach is for more countries and institutions to establish mentorship opportunities, communication platforms, and to bring youth in their delegations to official CITES meetings.

While advocating for increased youth engagement, it is important to recognise the potential limitations of this approach. Youth-led innovation can be inhibited by negative attitudes towards youth, risk aversion, low tolerance for new and innovative ideas, resource constraints, and power dynamics, such as a reluctance to ‘hand over’ (Bastien and Holmarsdottir, 2017; Jørgensen et al., 2019). Additional challenges and concerns identified by youth during the CGYN brainstorming sessions include: resistance from senior policymakers to increasing youth participation; lack of institutionalised pathways for youth engagement; limited resources and/or lack of strategic foresight in developing youth capacity within organisations; underrepresentation of youth from countries with weaker CITES implementation frameworks; Parties not responding to notifications or calls for youth nominations; limited access to relevant education and training; perceptions of inexperience; tokenism; resource and funding constraints, especially with other CITES initiatives that require funding for immediate issues; cultural and generational barriers, and the digital divide (i.e., unequal access to digital technology). Another challenge is the retention and succession planning of staff within CITES authorities and related organisations operating in this field, creating a long-term gap in skilled and empowered personnel. While engaging youth is vital to achieving the goals outlined in the CITES Strategic Vision, the numerous challenges highlight the pressing need for external support and developing meaningful collaborations. It is important to find ways to overcome these challenges to facilitate the development of the next generation of conservation professionals across governmental and non-governmental sectors.

Shared values are crucial to international sustainability agendas, as they serve as the foundation for decision-making in pursuit of goals, foster a sense of common purpose among diverse stakeholders, ensure that initiatives are culturally sensitive, and underpin long-term commitments. The values for the CITES Strategic Vision include “a shared commitment to fairness, impartiality, geographic and gender balance, and to transparency.” CGYN’s values align closely. The Network believes in equal opportunity regardless of youths’ identifying factors. Decision-making processes aim to be clear, balanced, open, and collaborative, and conflicts of interest and personal biases and prejudices are to be minimised where possible. For example, gender is increasingly acknowledged as an essential consideration in the design of anti-illegal wildlife trade measures, yet it remains largely overlooked (Green et al., 2023). CGYN fosters diversity through collaboration and inclusivity across regions and genders, actively engaging with the global youth community to ensure every voice is heard and respected. Additional values that are embodied by CGYN include empowerment, optimism, and openness to innovation.

The growing environmental consciousness of the 1990s corresponded to the reflection of intergenerational equity in international treaties (Bertram, 2023). Intergenerational equity and duties of justice are often expressed in terms of fairness to young people and future generations for their rights to healthy and sustainable environmental heritage to be protected (Summers and Smith, 2014). This concept is widely discussed in international policy, particularly in relation to the depletion of natural resources and biodiversity, the deterioration of environmental quality, and the heightened challenges of anthropogenic climate change. Young people may not only be beneficiaries of measures to achieve intergenerational equity, but also harbingers of it (Lim et al., 2017). Modes for collaborating with youth to address intergenerational issues in global sustainability initiatives may include: (1) participation by invitation only; (2) open application recruitment; (3) knowledge-sharing through early career bodies; (4) strategic decision making to secure intergenerational perspectives at highest levels; and (5) maintaining partnerships (Jørgensen et al., 2019). We advocate for further integration of all five modes in CITES processes.

As discussed, this journey will not be without its challenges. However, we outline that supporting youth in wildlife trade governance may facilitate a number of unique contributions to a legal and sustainable international wildlife trade, including clear pathways for driving awareness raising, cross-border collaboration, information sharing, and innovation. With intergenerational collaboration, and the proactive support and mentorship from wildlife trade policy leaders, youth will ensure they are not just recipients of intergenerational equity but leaders in its realization. Overall, it is evident that youth can play important and varied roles in achieving the CITES Strategic Vision by 2030. Future studies by young researchers could include undertaking an analysis to identify knowledge and policy gaps, and where youths’ assistance is needed to address them to support the implementation of the Convention.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

MA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The publication of this paper was sponsored through a Smithsonian Institution Life on a Sustainable Planet environmental justice grant. In-kind partners in this sponsorship include the International Alliance Against Health Risks in the Wildlife Trade and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

We would like to extend our deepest gratitude to the National Parks Board Singapore, Government of Switzerland, Mandai Nature, and Temasek Foundation for providing financial and in kind support which made the Youth Leadership Programme possible. We would like to thank the CITES Secretariat for their ongoing support for our efforts to increase youth involvement in CITES processes. We would also like to express our gratitude to all the participants in Singapore for their passion, enthusiasm, collaborative spirit, and ongoing engagement.

Author YT was employed by S.E.A. Aquarium

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

‘t-Sas-Rolfes M., Challender D. W., Wainwright L. (2024). “Playing the CITES game: Lessons on global conservation governance from African megafauna,” in Environmental Policy and Governance 35, 1–16. doi: 10.1002/eet.2123

Anagnostou M. (2024). “Disentangling and demystifying illegal wildlife trade and crime convergence,” in UWSpace Repository (University of Waterloo). Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10012/21093.

Bastien S., Holmarsdottir H. B. (2017). “The Sustainable development goals and the role of youth-driven innovation for social change,” in Youth as Architects of Social Change. Eds. Bastien S., Holmarsdottir H. (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-66275-6_1

Bertram D. (2023). ‘For you will (Still) be here tomorrow’: the many lives of intergenerational equity. Transnational. Environ. Law 12, 121–149. doi: 10.1017/S2047102522000395

CITES 17.57 (Rev. CoP19), 18.31 (Rev. CoP19), 18.32 (Rev. CoP19) & 19.54 Engagement of indigenous peoples and local communities. Available online at: https://cites.org/eng/dec/index.php/44372 (Accessed February 7, 2025).

CITES (2016). Youth Engagement. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), Conf. 17.5 (Rev. CoP18). (Geneva: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

CITES (2021). CITES Strategic Vision: 2021-2030. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), Conf. 18.3. (Geneva: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (2022). Communication, Education and Public Awareness (CEPA). Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/cepa (Accessed February 7, 2025).

Dreborg K. H. (1996). Essence of backcasting. Futures 28, 813–828. doi: 10.1016/S0016-3287(96)00044-4

ECLAC (2018). Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2018 (Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Accessible format (LC/A.2023/1-LC/PUB.2018/8/Rev.1/-*).

Ekka B., Joseph G. A., Verma P., Anandaram H., Aarif M. (2022). A review of the contribution of youth to sustainable development and the consequences of this contribution. J. Positive School. Psychol. 6 (6), 3564–3574.

GITOC. (2024). Monitoring Online Illegal Wildlife Trade: Insights From Brazil and South Africa. Geneva: Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC) (Accessed February 7, 2025).

Green A. R., Anagnostou M., Harris N. C., Allred S. B. (2023). Cool cats and communities: Exploring the challenges and successes of community-based approaches to protecting felids from the illegal wildlife trade. Front. Conserv. Sci. 4, 1057438. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2023.1057438

Hesselink F., Goldstein W., van Kempen P. P., Garnett T., Dela J. (2007). Communication, Education and Public Awareness (CEPA): A Toolkit for National Focal Points and NBSAP Coordinators. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity and IUCN. Available online at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2007-059.pdf (Accessed February 7, 2025).

Jørgensen P. S., Evoh C. J., Gerhardinger L. C., Hughes A. C., Langendijk G. S., Moersberger H., et al. (2019). Building urgent intergenerational bridges: assessing early career researcher integration in global sustainability initiatives. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainabil. 39, 153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.10.001

Kaukonen M. W. (2014). Voluntary Conservation Activities as Platforms for Youth Development: Youth Engagement in Integrated Conservation and Development Initiatives in Nepal (Helsinki: University of Helsinki).

Kioko J., Kiringe J. W. (2010). Youth’s knowledge, attitudes and practices in wildlife and environmental conservation in Maasailand, Kenya. South. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 27, 91–101.

Kulkarni R., Di Minin E. (2023). Towards automatic detection of wildlife trade using machine vision models. Biol. Conserv. 279, 109924. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2023.109924

Kumar A. (2023). Promoting youth involvement in environmental sustainability for a sustainable future. Edumania-An. Int. Multidiscip. J. 1, 261–278. doi: 10.59231/edumania/9012

Lim M., Lynch A. J., Fernández-Llamazares Á., Balint L., Basher Z., Chan I., et al. (2017). Early-career experts essential for planetary sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainabil. 29, 151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.02.004

McPherson T. (2007). Digital youth, innovation, and the unexpected. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press).

Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Colombia (2024). Environmental and territorial defenders of Latin America call for their protection ahead of COP16. Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development. Available online at: https://www.minambiente.gov.co/defensores-ambientales-y-territoriales-de-latinoamerica-lanzan-llamado-por-su-proteccion-rumbo-a-la-cop16/ (Accessed February 7, 2025).

Nadeson T., Barton M. (2014). The role of youth in the conservation of biodiversity: WWF-Malaysia’s experiences. Population 15, 6–13.

OECD. (2018). Strengthening Governance and Reducing Corruption Risks to Tackle Illegal Wildlife Trade: Lessons from East and Southern Africa, Illicit Trade (Paris: OECD Publishing). doi: 10.1787/9789264306509-en

Padma T. V. (2022). Using citizen science to track illegal wildlife trade in the Himalayas. Menlo Park: Mongabay. Available online at: https://india.mongabay.com/2022/01/using-citizen-science-to-track-illegal-wildlife-trade-in-the-himalayas/ (Accessed February 7, 2025).

Pérez-Torres V. (2024). Social media: a digital social mirror for identity development during adolescence. Curr. Psychol. 43, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-05980-z

PwC (2023). Global youth outlook: Insights into youth priorities. Available online at: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/government-public-services/global-youth-outlook.html (Accessed February 7, 2025).

Rendell A. S., Kantamaturapoj K. (2021). Youth empowerment for the protection of endangered species in Thailand: A case study of fighting extinction project. J. Humanities. Soc. Sci. Thonburi. Univ. 15, 46–57.

Roe D., Dickman A., Kock R., Milner-Gulland E. J., Rihoy E. (2020). Beyond banning wildlife trade: COVID-19, conservation and development. World Dev. 136, 105121. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105121

Sebba J., Griffiths V., Luckock F. H., Robinson C., Flowers S., et al. (2009). Youth-led innovation: Enhancing the skills and capacity of the next generation of innovators. (London: NESTA).

Seddon P. J., Khoja A. R. (2003). Youth attitudes to wildlife, protected areas and outdoor recreation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Ecotourism. 2, 67–75. doi: 10.1080/14724040308668134

Sithole S. S., Walters G. M., Mbatha P., Matose F. (2024). Youth engagement in global conservation governance. Conserv. Biol. 38, e14387. doi: 10.1111/cobi.14387

Summers J. K., Smith L. M. (2014). The role of social and intergenerational equity in making changes in human well-being sustainable. Ambio 43, 718–728. doi: 10.1007/s13280-013-0483-6

UNEP (2021). United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Principles and Policy Guidance on Children’s Rights to a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment in the ASEAN Region (Nairobi: UNEP).

UNGA (1989). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Vol. 1577 (New York: United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Treaty Series.

UNODC (2024). World Wildlife Crime Report 2024: Trafficking in Protected Species (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes (UNODC).

Xu Q., Li J., Cai M., Mackey T. K. (2019). Use of machine learning to detect wildlife product promotion and sales on Twitter. Front. Big. Data 2, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/fdata.2019.00028

Keywords: biodiversity, global governance, illegal wildlife trade, sustainability, sustainable development, youth

Citation: Anagnostou M, Ng CBY, Cepeda R, Lee JGH, Loo AHB, Ng PXK, Sitjar K, Tan HMS, Tang YJ and Ting WK (2025) Global youth as catalysts for legal and sustainable wildlife trade solutions. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1553549. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1553549

Received: 30 December 2024; Accepted: 26 February 2025;

Published: 02 April 2025.

Edited by:

Meredith L. Gore, University of Maryland, College Park, United StatesReviewed by:

Benjamin Michael Marshall, Suranaree University of Technology, ThailandCopyright © 2025 Anagnostou, Ng, Cepeda, Lee, Loo, Ng, Sitjar, Tan, Tang and Ting. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michelle Anagnostou, bWljaGVsbGUuYW5hZ25vc3RvdUBiaW9sb2d5Lm94LmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.