- 1Department of Ecology, Evolution & Behavior, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, United States

- 2United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC, United States

- 3Worldwide Fund for Nature, Arusha, Tanzania

From the 1800s to the 1950s, “spirit lions” and “spirit leopards” were blamed for countless deaths across Africa that were in fact caused by a combination of genuine carnivore attacks and murders instigated by witch doctors and secret societies. The widespread belief in supernatural spirit animals was viewed by the colonial authorities as rendering populations more vulnerable to further attacks by actual lions and leopards, as villagers were often reluctant to take concrete steps to eliminate the dangerous animals. Nearly a thousand people were attacked by lions in southern Tanzania between 1990 and 2006, involving 32 spatially discrete outbreaks that had been categorized by local communities as having been caused either by spirit lions or by real lions. Our interviews revealed that at least 40% of adults in three of the worst-hit districts believed in spirit lions and that this belief generally delayed their communities’ response. Consequently, outbreaks that were attributed to spirit lions persisted far longer than those attributed to real lions and included nearly twice as many victims. Belief in spirit lions declined with level of primary-school education, and male respondents were less likely to express a belief in spirit lions when interviewed by an American woman than by a Tanzanian man.

1 Introduction

In this special issue on the value of traditional knowledge, it is worth noting that traditional beliefs can sometimes have negative consequences. People living with large carnivores often believe in the supernatural powers of man-eating tigers, leopards, and lions. In the Sundarbans of south Asia, for example, a proportion of Muslims and Hindus alike perform daily rituals to protect themselves and their loved ones against tiger attacks, praying to Bonbibi, the guardian spirit of the forest, for protection against Dakshin Rai, the King of the South who is gifted with the ability to transform himself into a tiger (Thapar, 1997; Uddin, 2011). In the villages bordering the Sundarbans National Park, honey collectors and fishermen regularly enter tiger habitat, and if any are killed, their wives may be labeled as “husband eaters.” “Tiger widows” are often shunned by their neighbors, being blamed for their husbands’ deaths because they lacked piety during their rituals and prayers to Bonbibi and Dakshin Rai (Chowdhury et al., 2016).

Throughout Africa in the 19th and early 20th Centuries, outbreaks of man-eating leopards and lions were widely viewed as the work of “spirit animals” (Beatty, 1915; Schneider, 1982; Roberts, 1985; Nwaka, 1986; Pratten, 2007; Van Bockhaven, 2013). These supernatural entities were believed to be either actual leopards/lions that had fallen under the control of witch doctors or humans with the power to take the form of wild animals. Reinforcing these beliefs were concurrent attacks by real-life leopards or lions in the same locations as leopard or lion societies that murdered their victims with weapons that mimicked claw marks and bite wounds. In the most notorious outbreaks in Sierra Leone, Congo, Nigeria, and Tanganyika, the colonial authorities were often unable to distinguish between human and animal attacks, but the string of deaths only ended when suspects were captured and executed.

Belief in the supernatural would be expected to delay or even prevent a concerted effort to bring an outbreak under control. The magical force may be considered immune to human action or the victims somehow deserving of their fate – and any attempt to kill the spirit animal might even provoke an angry spirit into further attacks. Indeed, one of history’s worst outbreaks involved the man-eating lions of Njombe in southern Tanganyika, where local communities were so convinced that the lions were controlled by a witch doctor named Matamula Mangera that most refused to help the District Game Officer, George Rushby, locate and destroy the animals (Bulpin, 1962; Rushby, 1965). Left largely unreported, the man-eaters remained virtually unmolested for perhaps as long as fifteen years and were believed to have taken hundreds of lives. Even in the famous case of the man-eating lions of Tsavo, Patterson (1907) reported how the railway workers “assured me that it was absolutely useless to shoot them. They were quite convinced that the angry spirits of two departed native chiefs had taken this form in order to protest against a railway being made through their country.”

Nearly a thousand people were attacked by lions in southern Tanzania following the rapid conversion of natural habitat to subsistence agriculture in the final decade of the 20th Century (Kushnir et al., 2014). Habitat loss reduced the abundance of the lions’ preferred prey species, and the expansion of agriculture increased the density of a nocturnal crop pest, the bush pig, which forced people to sleep in their fields, thus rendering communities more vulnerable to lions (Packer et al., 2005). Our surveys revealed that people’s perceptions of relative risks of lion attacks were largely accurate (e.g., that adults were more at risk than children, farm fields were more dangerous than wildlife areas, etc.) (Kushnir et al., 2010; Kushnir and Packer, 2019).

Almost all the cases examined in our previously published papers had been reported to the Wildlife Division of the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources, and we encountered no rumors of lion societies or murderous lion men within any of our primary study communities. The pattern of attacks across the lunar cycle was consistent with the behavior of lions in the Serengeti (i.e., almost all the cases occurred at night and were most frequent during the hours with little or no moonlight, Packer et al., 2011). Separate outbreaks showed characteristic spatiotemporal patterns (Packer et al., 2019), locations (e.g., farm fields; Kushnir et al., 2014), and contexts (e.g., harvest season; Packer et al., 2005), and ended with the lions’ deaths – either through the actions of District Game Officers or by villagers lacing prey carcasses with poison (Packer, 2023).

Given the overwhelming evidence that these attacks were all made by real lions, it was striking that so many people initially sought help from their local witch doctor rather than the local game control officer after the death of a loved one (Packer, 2015). A similar belief in spirit lions in neighboring Mozambique ultimately led to twenty-four people being lynched by angry mobs in 2002–2003 when the local healers ultimately failed to end the local outbreaks (Israel, 2009). Thus, in this report, we have revisited our survey results to illustrate the pervasiveness of people’s beliefs in spirit lions and to ask whether these perceptions resulted in greater numbers of lion attacks when outbreaks were attributed to spirit lions.

2 Methods

We worked in three Tanzanian districts that had experienced large numbers of lion attacks between 1990 and 2005: Lindi (185 cases), Rufiji (95), and Tunduru (67) (see Kushnir and Packer, 2019). About two-thirds of these attacks were fatal, the victims were disproportionately male, and three-fourths were adults. Using data on attack locations obtained from district records, we selected four villages in each study area, and scheduled a total of 70 questionnaire-based interviews in 2005 by randomly selecting households from each village register and alternating between female and male household heads to ensure an even gender ratio. As specified in our earlier publications, questionnaires included prompts on demographics, socioeconomics, education, attack history in family, sighting of lions and lion signs, and perceptions of risk (Kushnir et al., 2010; Kushnir and Packer, 2019). The questionnaires had received IRB approval from the University of Minnesota, all participants gave written permission, and participants ranged in age from 21 to 75 years of age.

We dichotomized the subjects’ responses indicating a personal belief in spirit lions after having first asked an open-ended question about whether the interviewee had heard about or knew anything about spirit lions and then asked for additional details, depending on the interviewee’s level of comfort. Note, however, that four people did not show up for the interview, and four others refused to discuss spirit lions, leaving a total of 62 completed responses on the subject.

An overall dataset of lion attacks across the entire country between 1983 and 2010 was subdivided into discrete outbreaks that were separated from each other either by the gap length between successive attacks or by the spatial distance between successive cases, thereby defining 32 discrete outbreaks following the epidemiological definitions of Packer et al. (2019). For each outbreak, Dennis Ikanda (DI) asked village game officers and other local officials to which type of lions their communities attributed the attacks. The outbreaks were then classified as either the result of real lions (n=21) or of spirit lions (n=11).

3 Results

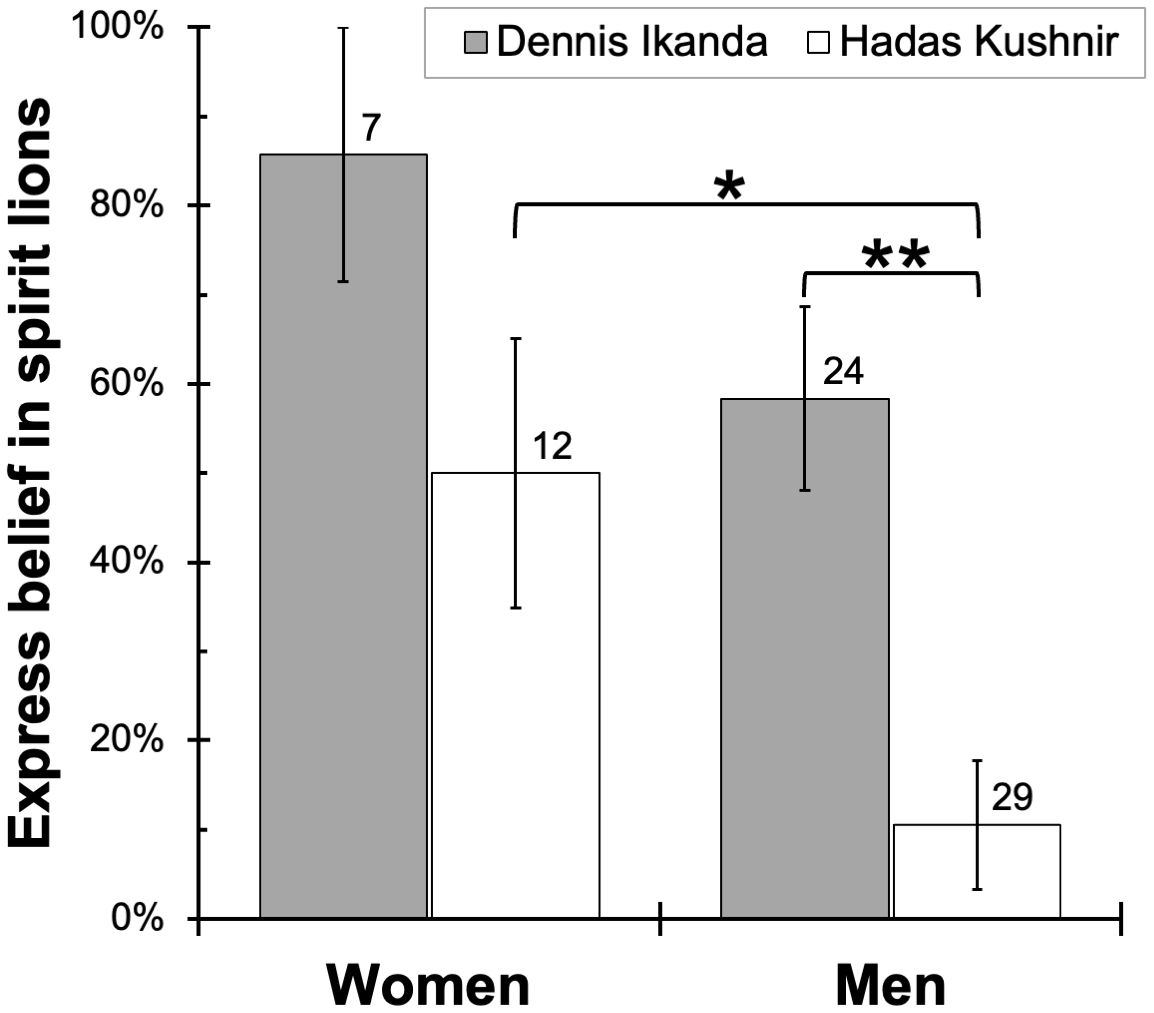

Over 45% of the 62 respondents indicated a belief in spirit lions, but the data showed a strong interaction between the subject’s gender and the interviewer’s identity (Figure 1). While a similar proportion of men and women expressed a belief in spirit lions to Dennis Ikanda (DI, a Tanzanian man), men were far less likely to admit belief to Hadas Kushnir (HK, an American woman) (women: DI vs HK: P=0.1733; men: DI vs HK: P=0.0016), implying that men were reluctant to express a belief in the supernatural to a female outsider. Belief in spirit lions did not vary significantly across the three districts (Lindi: 48%, n=19; Rufiji: 38%, n =21; Tunduru: 50%, n=22). Although belief in spirit lions declined with levels of primary school education (Figure 2), it did not correlate with age: while the younger generation might be expected to be more skeptical of the supernatural, 6 of 10 respondents in their 20s professed a belief in spirit lions.

Figure 1 Proportion of respondents of each sex who expressed a belief in spirit lions. Data are separated according to the identity of the interviewer, as men were significantly less likely to reply in the affirmative to Hadas Kushnir than to Dennis Ikanda (P<0.01, Fisher Test) and men were less likely than women to express belief in spirit lions to Kushnir (P<0.05). Vertical lines are standard errors. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Figure 2 Proportion expressing belief in spirit lions declined with the number of years of primary school education. “Standard” refers to the final school year of each individual (e.g., Standard 2, Standard 4, Standard 6); “Completed Standard 7” includes one individual who reached Form 2 in secondary school; all the rest left after the final year of primary school. The declining belief in spirit lions remains significant (P=0.03) in a univariate regression and when controlling for the interaction term between gender and interviewer ID.

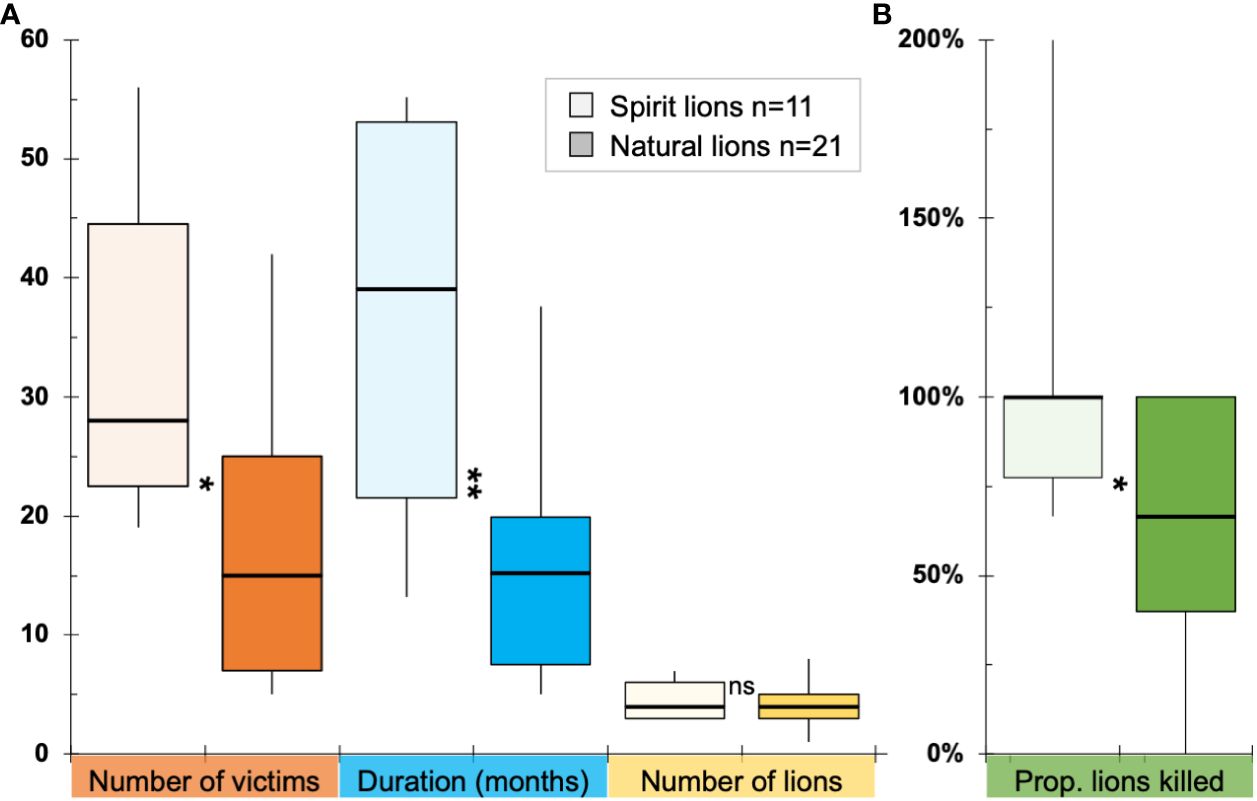

Classification of a particular outbreak as being caused by spirit lions was largely driven by the severity of the initial attack in each series. If the first victim died, people attributed the outbreak to spirit lions; if the victim lived, the outbreak was attributed to real lions. “Spirit outbreaks” involved more victims and lasted longer than “natural outbreaks,” even though people reported a similar number of lions being involved in each type (Figures 3A). Finally, a significantly higher proportion of the reported lions were ultimately killed in spirit outbreaks than in natural outbreaks (Figure 3B).

Figure 3 Comparisons between outbreaks that were widely held to have been caused by spirit lions (lighter colors) and those that were generally accepted as being caused by real lions (darker colors). (A) Number of victims: P=0.0147; duration: P=0.0042; number of lions: P=0.7039. (B) Proportion lions killed: P=0.0238. Box plots indicate medians, quartiles, and 10% and 90% percentiles. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

4 Discussion

Male interviewees appeared reluctant to admit their belief in spirit lions to HK, suggesting a possible concern that their views might not be taken seriously by a female outsider. If so, then it is likely that over half of all our respondents in fact harbored some level of conviction that lion attacks involved supernatural forces – and although belief in spirit lions declined with the number of years of primary school education, 60% of interviewees in their twenties (the youngest cohort in our survey) reported a belief in spirit lions. Given the pervasiveness of these beliefs, it is not surprising that communities responded less effectively during outbreaks that they presumed to involve spirit lions. A more passive attitude toward the dangers of man-eating lions likely led to greater numbers of victims over longer stretches of time than man-eaters that were immediately recognized as flesh-and-blood animals.

Comments by the interviewees help explain the slower response to alleged attacks by spirit lions:

35-yr-old man, Rufiji: “During the last outbreak, people … sent for witchdoctors/elders three times to determine if the lion causing the problem was a spirit lion or a normal lion. The first two times they were unable to tell, but the third time they … determined that it was just a normal lion.”

38-yr-old woman, Rufiji: “Attacks are usually instigated by local village members secretly and can only be uncovered through witchcraft. Rituals are conducted after killing the spirit lion, likely in secrecy.”

42-yr-old woman, Rufiji: “Spirit lions cannot be killed when hunted. To kill a spirit lion, it is necessary to consult a different witch doctor than the one who created it.”

- 43-yr-old woman, Tunduru: “Spirit lions are not seen when hunted, so normal lions are killed instead. You cannot kill a spirit lion.”

70-yr-old woman, Lindi: “Spirit lions are sent when there is a misunderstanding. Spirit lions do not roar but attack; normal lions do roar but do not attack. Spirit lions are sent, they are not normal lions that attack people. Normal lions do not attack even when they meet people. You must see elders before hunting spirit lions.”

70-yr-old man, Lindi: “Spirit lions … kill many people before they are finally killed after rituals have been made to contain them. The problem of man-eating outbreaks can be prevented from happening in the area using ritual practices. The problem is that people lack trust in the process in these modern times.”

The fact that spirit outbreaks only ended after a higher proportion of lions was destroyed could be due to several reasons. First, without a rapid response, the animals classified as spirit lions may have become less intimidated around people and hence grown so persistent that they continued their attacks until they were all killed. In contrast, a proportion of lions in the “real lion outbreaks” that had experienced a more forceful response may have reverted to alternative prey or moved elsewhere. Second, even though multiple lions were almost always involved, spirit lion outbreaks were almost always attributed to a particular lion (e.g., Ulanga (“punisher”), Simba Karatasi (“lion that moves like windblown paper”)), and some were even named after a specific witch doctor. Hence, the true number of man-eating lions was underestimated, and a higher “proportion” was reported as having been ultimately killed. For example, villagers in Rufiji District attributed forty-seven attacks to a male that they had named “Osama”, but the outbreak actually involved multiple individuals, including several adult females, and Osama would have been a small cub when the string of attacks first started (Packer, 2015).

Across three villages in Sumatra, McKay et al. (2018) reported a greater tolerance for hypothetical tiger attacks in the community with the most widespread beliefs in “spirit tigers,” as these are viewed as ancestral figures that play an important role in enforcing moral codes. The authors therefore suggested that such spiritual values provide important potential conservation benefits. But whereas the Sumatran tiger is classified by CITES as critically endangered, Tanzania is home to far more lions with concomitantly higher frequencies of lion attacks, so community tolerance for spirit lions risks many more lives in Tanzania than in Indonesia. However, efforts to change attitudes toward dangerous animals usually rely on rational decision making (i.e., highlighting financial benefits from ecotourism vs. the costs of agricultural losses), but these will carry little weight for people with deep-seated beliefs in the supernatural. In our response to villagers’ widespread beliefs in spirit lions, we approached man-eating as a public health issue and focused on the need for crop protection against nocturnal bush pigs, as most outbreaks started with attacks on people sleeping in their fields to protect their crops (Packer et al., 2005). We pilot-tested alternative methods for minimizing crop losses (comparing eleven control plots with seventeen equipped with irritants (noise makers or lights), and twelve with physical barriers) and found that simple low-tech fences made from woven strips of wood were sufficient to exclude bush pigs from agricultural fields (Packer, 2023). Once the impacts of the fence became apparent, one villager started building his own fences, and his neighbors soon adopted the same tactic. Whereas spirit lions have mystical powers, bush pigs do not, so perhaps our conflict-mitigation project succeeded because it conformed with people’s rational understanding rather than expressed any doubts about their irrational beliefs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) University of Minnesota. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. HK: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation. DI: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Lyimo and E. Hyera for assistance with data collection. The Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, Tanzanian Wildlife Division, and the Commission for Science and Technology provided permission to conduct research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

Note that the opinions and views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of USAID.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2024.1299575/full#supplementary-material

References

Beatty K. L. (1915). Human Leopards; an account of the trials of Human Leopards before the Special Commission Court (London: Hugh Rees).

Chowdhury A. N., Brahma A., Mondal R., Biswas M. K. (2016). Stigma of tiger attack: Study of tiger-widows from Sundarban Delta, India. Indian J. Psychiatry 58, 12–19. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.174355

Israel P. (2009). The war of lions: witch-hunts, occult idioms and post-socialism in northern Mozambique. J. South. Afr. Stud. 35, 155–174. doi: 10.1080/03057070802685627

Kushnir H., Leitner H., Ikanda D., Packer. C. (2010). Human and ecological risk factors for unprovoked lion attacks on humans in southeastern Tanzania. Hum. Dimensions Wildlife 15, 315–331. doi: 10.1080/10871200903510999

Kushnir H., Olson E., Juntunen T., Ikanda D., Packer C. (2014). Using landscape characteristics to predict risk of lion attacks in southeastern Tanzania. Afr. J. Ecology. 52, 524–532. doi: 10.1111/aje.52.issue-4

Kushnir H., Packer C. (2019). Perceptions of risk from man-eating lions in southeastern Tanzania. Front. Ecol. Evolution: Conserv. 7. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00047

McKay J. E., St. John F. A. V., Harihar A., Martyr D., Leader-Williams N., Milliyanawati B., et al. (2018). Tolerating tigers: Gaining local and spiritual perspectives on human-tiger interactions in Sumatra through rural community interviews. PLoS One 13, e0201447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201447

Nwaka G. I. (1986). The 'leopard' killings of southern annang, Nigeria 1943–48. Africa 56, 417–440. doi: 10.2307/1159998

Packer C. (2015). Lions in the Balance: Man-Eaters, Manes, and Men with Guns (Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press). doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226093000.001.0001

Packer C. (2023). The Lion: Behavior, Ecology and Conservation of an Iconic Species (Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press). doi: 10.1353/book.111069

Packer C., Ikanda D., Kissui B., Kushnir H. (2005). Ecology: Lion attacks on humans in Tanzania. Nature 436, 927–928. doi: 10.1038/436927a

Packer C., Shivakumar S., Craft M. E., Dhanwatey H., Dhanwatey P., Gurung B., et al. (2019). Species-specific spatiotemporal patterns of leopard, lion and tiger attacks on humans. J. Appl. Ecol. 56, 585–593. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13311

Packer C., Swanson A., Ikanda D., Kushnir H. (2011). Fear of darkness, the full moon and the lunar ecology of African lions. PLoS One 6, e22285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022285

Pratten D. (2007). The Man-Leopard Murders: History and Society in Colonial Nigeria (Bloomington: Indiana University Press). doi: 10.3366/edinburgh/9780748625536.001.0001

Roberts A. F. (1985). “'Like a roaring lion': Tabwa terrorism in the late nineteenth century,” in Banditry, Rebellion and Social Protest in Africa. Ed. Crummey D. (James Currey, London), 65–86.

Schneider H. K. (1982). “Male–female conflict and lion men of Singida,” in African Religious Groups and Beliefs. Ed. Ottenberg S. (Folklore Inst, Cupertino, CA), 95–109.

Thapar V. (1997). Land of the Tiger: A Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent. (Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press).

Uddin S. (2011). “Beyond National borders and religious boundaries: muslim and hindu veneration of bonbibi,” in Engaging South Asian Religions: Boundaries, Appropriations, and Resistances. Eds. Schmalz M. N., Gottschalk P. (State University of New York Press, New York), 61–82.

Keywords: spirit lions, man-eating, African lions (Panthera leo), Tanzania, supernatural

Citation: Packer C, Kushnir H and Ikanda D (2024) Traditional beliefs prolong outbreaks of man-eating lions. Front. Conserv. Sci. 5:1299575. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2024.1299575

Received: 22 September 2023; Accepted: 06 May 2024;

Published: 24 May 2024.

Edited by:

Eduardo J. Naranjo, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, MexicoReviewed by:

Philip Nyhus, Colby College, United StatesFrancesco Maria Angelici, National Center for Wildlife, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2024 Packer, Kushnir and Ikanda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Craig Packer, cGFja2VyQHVtbi5lZHU=

Craig Packer

Craig Packer Hadas Kushnir

Hadas Kushnir Dennis Ikanda3

Dennis Ikanda3