- 1Geography and Environmental Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom

- 2Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3School of Environment, Earth and Ecosystem Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom

- 4Grupo de Investigación en Biodiversidad, Medio Ambiente y Salud ‐BIOMAS‐ Universidad de Las Américas (UDLA), Quito, Ecuador

- 5Instituto Geofísico, Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador

- 6Geociencias Barcelona, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Barcelona, Spain

Reference ecosystems used in tropical forest restoration lack the temporal dimension required to characterise a mature or intact vegetation community. Here we provide a practical ‘palaeo-reference ecosystem’ for the eastern Andean forests of Ecuador to complement the standard ‘reference ecosystem’ approach. Pollen assemblages from sedimentary archives recovered from Ecuadorian montane forests are binned into distinct time periods and characterised as 1) Ancient (pre-human arrival), 2) Pre-European (Indigenous cultivation), 3) Successional (European arrival/Indigenous depopulation), 4) Mature (diminished human population), 5) Deforested (re-colonisation), and 6) Modern (industrial agriculture). A multivariate statistical approach is then used to identify the most recent period in which vegetation can be characterised as mature. Detrended correspondence analysis indicates that the pollen spectra from CE 1718-1819 (time bin 4 – Mature (diminished human population)) is most similar to that of a pre-human arrival mature or intact state. The pollen spectra of this period are characterised by Melastomataceae, Fabaceae, Solanaceae and Weinmannia. The vegetation of the 1700s, therefore, provides the most recent phase of substantial mature vegetation that has undergone over a century of recovery, representing a practical palaeo-reference ecosystem. We propose incorporating palynological analyses of short cores spanning the last 500 years with botanical inventory data to achieve more realistic and long-term restoration goals.

Introduction

The 2020’s are the United Nations ‘Decade on Ecosystem Restoration’ with the goal of ‘preventing, halting, and reversing the degradation of ecosystems worldwide’ (United Nations, 2020). In the Neotropics unparalleled levels of forest restoration have been called for to reverse decades of deforestation and aid in combating climate change (IPCC, 2018; IPBES, 2018; Dave et al., 2019). The aim is to conserve biodiversity whilst enhancing carbon sequestration, mitigating soil erosion and improving water security, whilst maximising beneficial outcomes and engaging with stakeholders (Keenleyside et al., 2012; Holl, 2017; Chazdon, 2017). Successful restoration of cleared tropical forest depends on understanding past human impact and identifying the rate and route (forest succession) in which tropical forests regenerate through time (decades-centuries) and over landscape-scales (Guariguata and Ostertag, 2001). This is then followed by effectively working towards placing the degraded site back onto a successional trajectory that mimics the natural dynamism of the ecosystem (Gann et al., 2019).

The subset of restoration projects that focus primarily on re-establishing a near-natural state i.e., those indicative of minimal human impact, may employ a ‘reference ecosystem’ approach. This is where evidence from the recent past, present and projected future is used to derive a model of the ecosystem had it not been degraded (Gann et al., 2019). Local mature ecosystems are favoured as reference targets if considered analogous to that of the pre-degraded past (Gann et al., 2019). However, determining if they are indeed intact, and to what extent, is challenging. Cleared Neotropical forest takes more than c. 50 years to recover its basal area and species richness (Guariguata and Ostertag, 2001; Chazdon et al., 2007; Rozendaal et al., 2019), c. 130 years to recover its structure (Martin et al., 2013; Loughlin et al., 2018a), and likely centuries if ever to recover its species composition (Poorter et al., 2016; Rozendaal et al., 2019). The sole reliance on recently (< 100 years) disturbed forests as reference ecosystems risks species characteristic of mature forests being overlooked in restoration plans. Restoration of degraded sites that replace what was once diverse tropical forest with a simplified vegetation community risks undermining its very rationale and increasing the vulnerability of these systems to collapse (Adolf et al., 2020; Heilmayr et al., 2020). Tropical forests close to settled human populations have almost certainly been burned, cleared, or selectively logged during the last century, as baring relict ecosystems, such as those found in the most inaccessible parts of the Andes almost nowhere remains untouched by direct human impact (Sylvester et al., 2017). Today at least two-thirds of the world’s tropical forests show some degree of human intervention (FAO and JRC, 2012; Hansen et al., 2019). Without establishing reference ecosystems with a greater temporal aspect there will always remain the risk of restoring a ‘shifted ecological baseline’ sensu Pauly (1995), one that reflects long-term degradation as our expectations of what is ‘normal’ diminish over generations (Soga and Gaston, 2018).

Palaeoecology offers the ability to supplement the standard ‘reference ecosystem’ approach by providing near-natural restoration targets rooted in empirical data. Using vegetation proxy data e.g., pollen, phytoliths, sedaDNA, recovered from sedimentary archives, long-term ecosystem changes and community response to environmental and anthropogenic drivers can be characterised over periods beyond that of observational studies, which rarely exceed 60 years (Grubb et al., 2020). The advantages of incorporating evidence of past vegetation into conservation and restoration planning has long been recognised (Godwin, 1956; Swetnam et al., 1999; Willis and Birks, 2006; Jackson and Hobbs, 2009; Seddon et al., 2014; Gillson and Marchant, 2014; Whitlock et al., 2018; Fordham et al., 2020). However, the laborious nature of an in-depth, multi-millennial palaeoecological analysis prior to restoration work means that the outcomes are seldom incorporated into restoration goals (Bush et al., 2014). Here we advocate for incorporating a practical ‘palaeo-reference ecosystem’ into the standard ‘reference ecosystem’ approach where possible. Using pollen records from sediments in the Quijos Valley on the eastern Andean flank of Ecuador, a biodiversity hotspot and global priority conservation area (Myers et al., 2000; Meyer et al., 2015; Cuesta et al., 2017), we identify a time period that provides the most recent phase of widespread mature forest vegetation in the region.

Study site

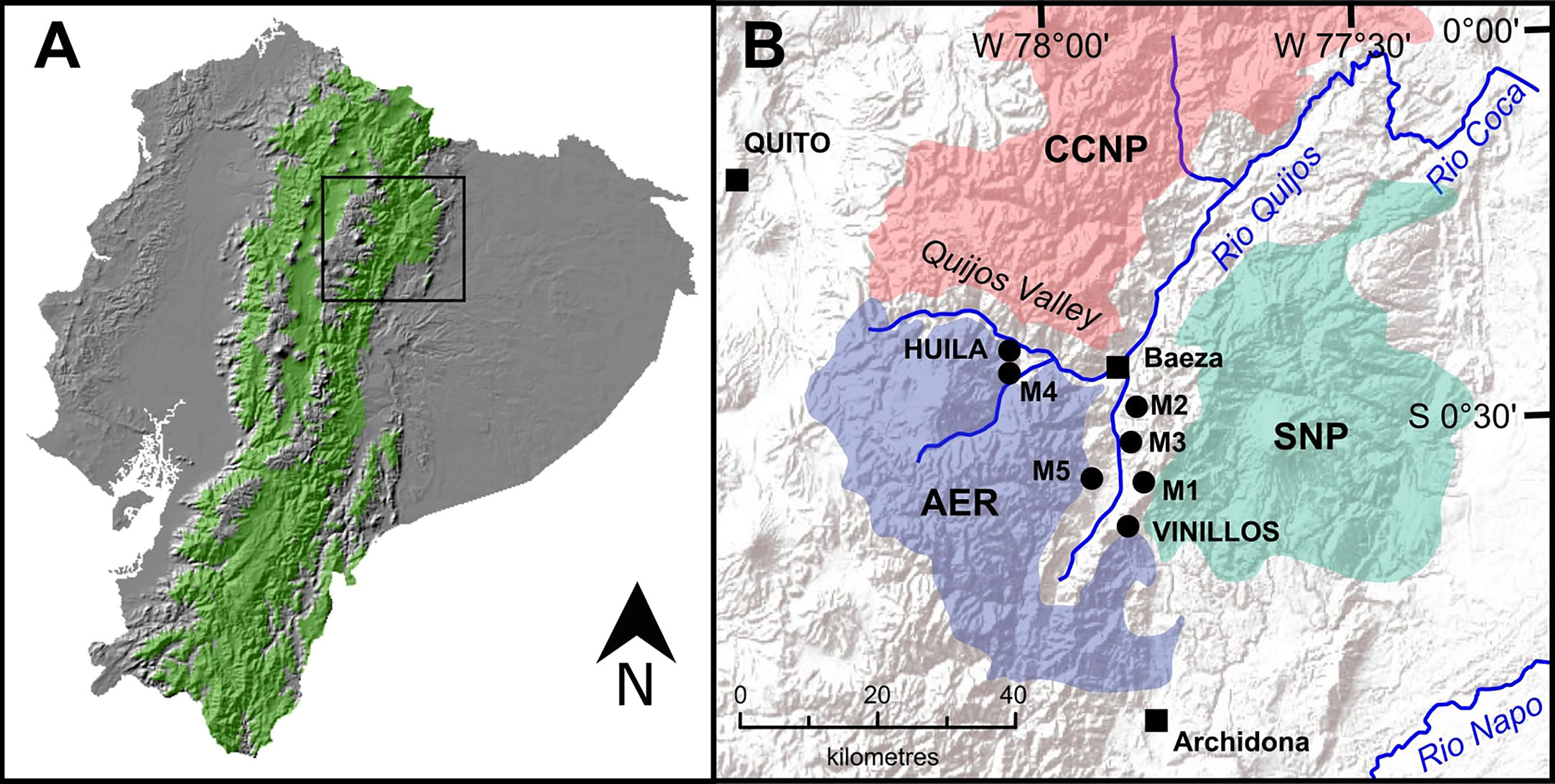

Eastern Andean montane forest forms a distinctive vegetation corridor (1,300-3,600 m asl) separating the lowland rainforests of Amazonia from the high-altitude grasslands (páramo) of the Andes (Gentry, 1995; Webster, 1995). In northern Ecuador, the Quijos Valley cuts perpendicular through the Andean forest forming a historically important trade route connecting past Andean civilizations such as the Inca to the peoples of Amazonia (Newson, 1995). Today an increasing human population, deforestation and cattle farming has led to the formation of a secondary forest mosaic landscape driven by human activity and encroaching on the outskirts of the surrounding three protected areas (Figure 1). Restoration of this degraded landscape is underway, driven by international (The Bonn Challenge, 2020), national (REDD+ Early Movers Program, 2020) and local (Humans for Abundance, 2020) restoration projects looking to restore forest ecosystems, through planting native and culturally important species in areas previously cleared for farming. However, without an appreciation of the long-term vegetation history of the region, reforestation projects in highly degraded areas based solely on planting a few endemic and native species risks working towards a simplified vegetation community.

Figure 1 (A) Republic of Ecuador with elevations corresponding to Andean montane forest (1300-3,600 m asl) highlighted in green. (B) The Quijos Valley and surrounding protected areas, Antisana Ecological Reserve (AER), Cayambe Coca National Park (CCNP), and Sumaco Napo-Galeras National Park (SNP). Black squares indicate population centres. Black dots indicate location of study sites (Loughlin et al., 2018a; Loughlin et al., 2018b).

Methods

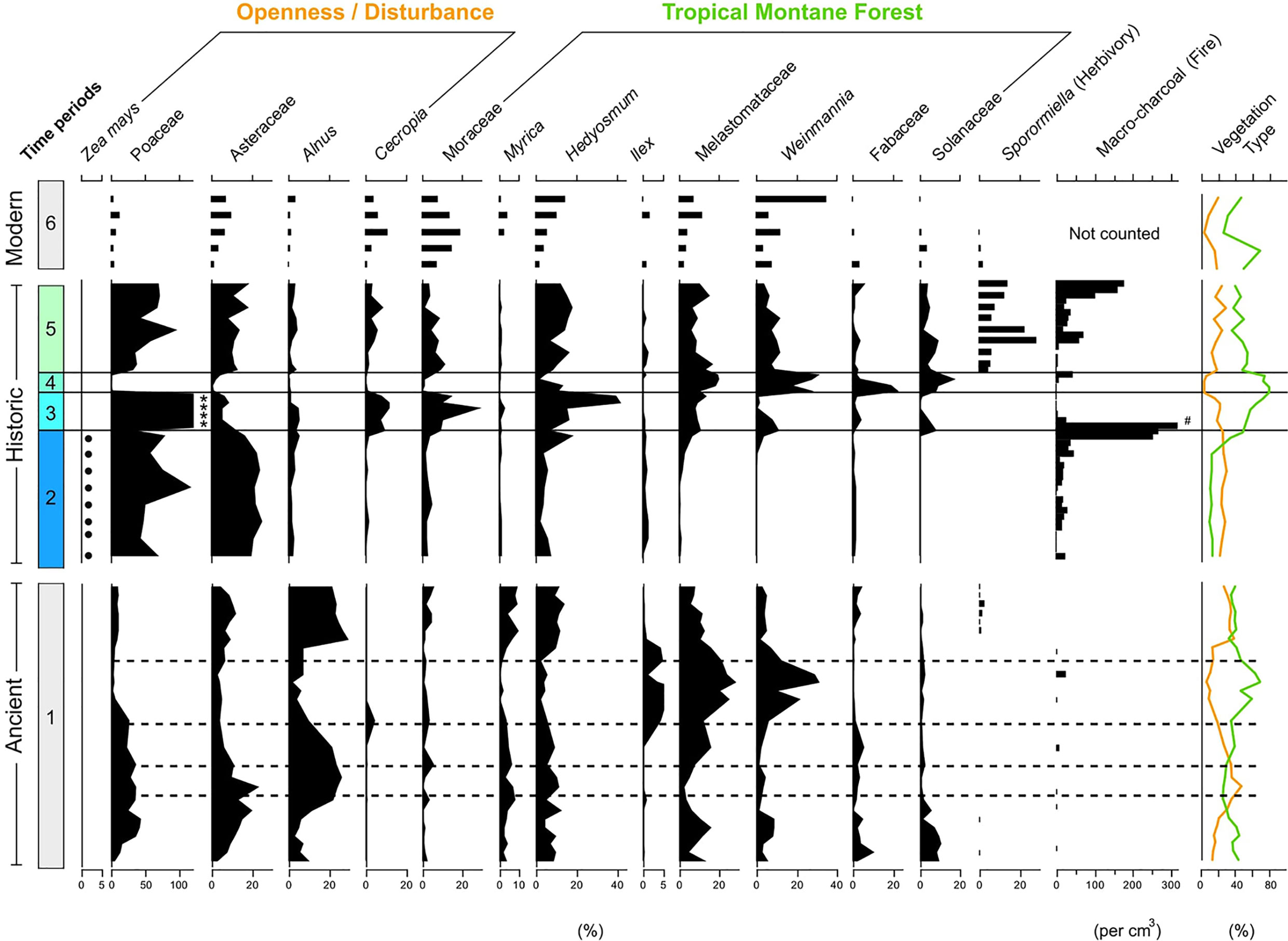

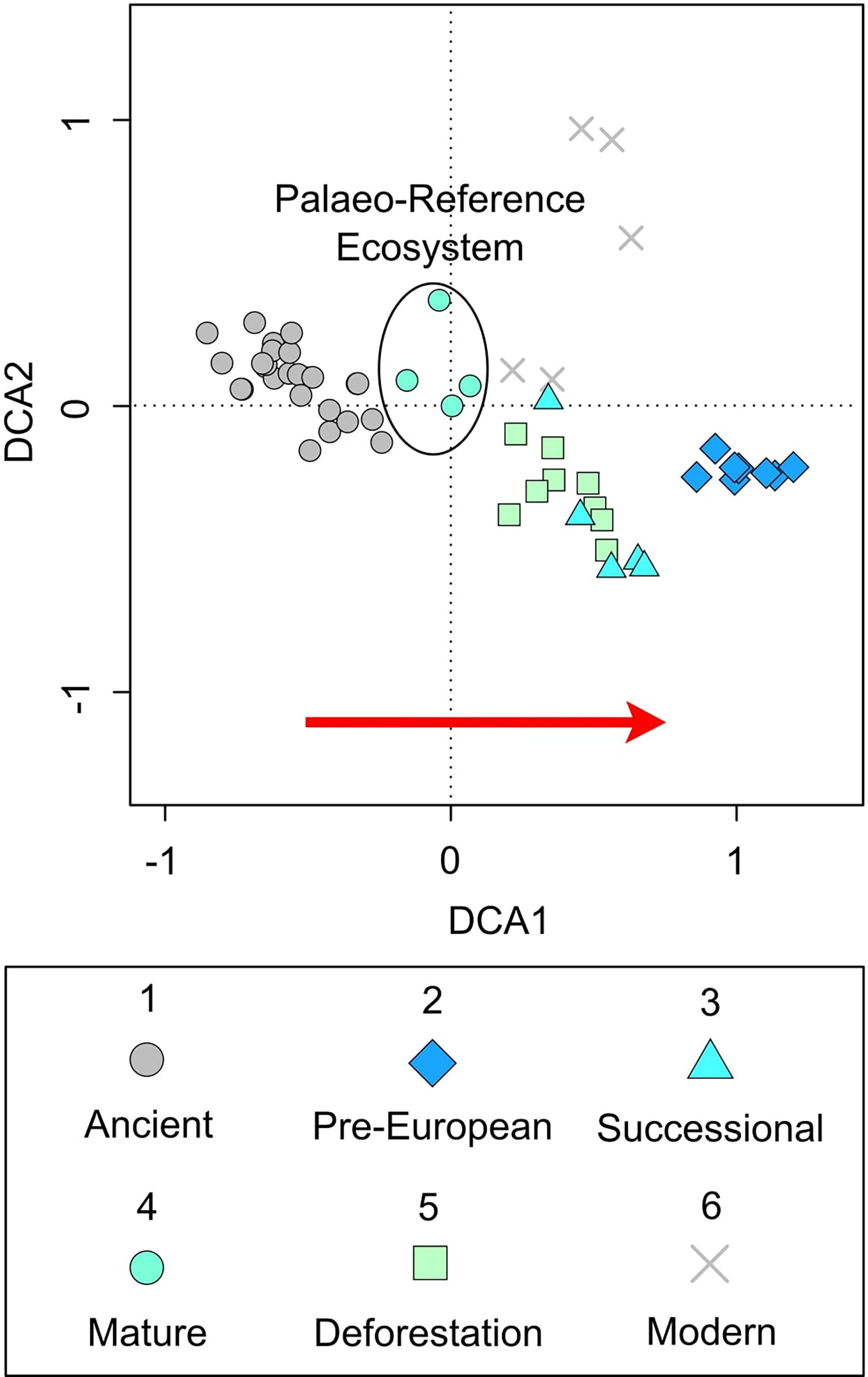

To establish a palaeo-reference ecosystem pollen records from the pre-human arrival landscape, recent past (c. last 700 years), and the modern mosaic landscape were analysed (see Loughlin et al., 2018a; Loughlin et al., 2018b). Data analysis and visualisation was undertaken in the ‘R’ statistical computing environment (R Core Team, 2020) using the package ‘vegan’ (Oksanen et al., 2019). Pollen assemblages covering six time-bins were characterised using a stratigraphically constrained cluster analysis (CONISS) on pollen percentage data corresponding to 1) Ancient (pre-human arrival); 2) Pre-European (Indigenous cultivation), 3) Successional (European arrival/Indigenous depopulation), 4) Mature (diminished population), 5) Deforestation (re-colonisation), and 6) Modern (industrial agriculture) time periods (Figure 2). Detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) was then used to provide a method of visualising the relationship between these pollen assemblages within their respective time bins (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Synthetic summary diagram of selected pollen types grouped into time bins. 1) Ancient (pre-human arrival), 2) Pre-European (Indigenous cultivation), 3) Successional (European arrival/Indigenous depopulation), 4) Mature (diminished population), 5) Deforestation (re-colonisation), and 6) Modern (industrial agriculture). Sporormiella fungal spores and macro-charcoal included as proxies of herbivory and fire respectively. Dashed lines in the ‘Ancient’ (1) time bin represent the position of volcanic tephra layers within the sediment. Due to the abundance of Poaceae (grass) pollen in the ‘Historic’ record grass pollen was excluded from the pollen sum. Asterisks (*) in the ‘Historic’ (3) time bin represent where Poaceae pollen exceeded 100% of the pollen sum. Zea mays presence recorded as dots (.) The ‘Modern’ records are displayed as bars as they are distinct geographic sites (see Figure 1). Hash (#) indicates where macro-charcoal exceeds 300 fragments per cm3.

Figure 3 Practical palaeo-reference ecosystem. Detrended correspondence analysis of pollen data grouped into time bins (re-plotted from Loughlin et al., 2018a). 1) Ancient (pre-human arrival) (Loughlin et al., 2018b), 2) Pre-European (Indigenous cultivation), 3) Successional (European arrival/Indigenous depopulation), 4) Mature (diminished population), 5) Deforestation (re-colonisation), and 6) Modern (industrial agriculture). Red arrow indicates an increasing signal of human impact.

Results and interpretation

The ordination (Figure 3) shows the signal from the pre-human arrival landscape (c. 45,000-42,000 years ago), indicative of a mature vegetation assemblage, is most similar to that which occurred in the historical record between CE 1718-1819, a period following peak Indigenous depopulation and the abandonment of the region by Europeans (time bin 4 – diminished population). Whilst the period after re-colonisation (post-CE 1819 and industrial agriculture) was shown to be most like that of the early secondary forest succession which followed European arrival and early Indigenous depopulation (c. CE 1588-1718). The open-agricultural landscape managed by the pre-European Indigenous population showed the greatest disparity and is characterised by evidence of intensive land management (Loughlin et al., 2018a).

The vegetation history of the Andean forest in the Quijos Valley viewed through this palaeoecological lens shows a direct response to changing human impact characteristic of the narrative of European arrival in the Americas (Koch et al., 2019). Within 30 years of the establishment of the first European settlement in the Quijos Valley (Baeza; CE 1559), the Indigenous cultivated landscape began a 250-year sequence of forest regrowth (c. CE 1588-1819). As the Indigenous peoples were exploited as forced labour by the occupying Europeans their numbers declined, culminating in CE 1578 with the Indigenous revolt led by the “great cacique Jumandi” (Uzendoski, 2004). As much of the surviving Indigenous population fled reprisals and disease, the region was gradually abandoned by the European colonizers (Newson, 1995). For c. 130 years (CE 1588 -1718) secondary forest regrowth occurred, characterised by pioneer taxa such as grasses and the fast growing tree Cecropia. This was subsequently followed by a more mature and structurally developed forest becoming established c. CE 1718-1819, characterised by the pollen of Melastomataceae, Fabaceae, Solanaceae and Weinmannia, in a region that was by then virtually uninhabited (Newson, 1995). Not until c. CE 1819 does any evidence of renewed human impact on the palynological signal occur in the form of an increase in disturbance indicators (Figure 2), and even then, the former population centre at Baeza consisted of only three small huts (Jameson, 1858).

Discussion

Prior to European arrival in the Americas (CE 1492), it has been estimated that c.60 million people lived in social structures from small groups of hunter gathers to vast civilisations (Koch et al., 2019). For thousands of years people domesticated crops, moulded landscapes to fit their needs and drove changes in ecosystems (Montoya et al., 2020; Duncan et al., 2021). However, within a century as much as 90% (c. 54 million people) of the population were dead as the result of European conquest and imported diseases (Koch et al., 2019). This continental scale depopulation led to population centres, managed land, and cultivated fields (c. 56 million hectares (Koch et al., 2019)) undergoing secondary succession, as vegetation reoccupied what was previously cleared (Hamilton et al., 2021).

Across the Americas in the following century (CE 1500’s) this sequence of Indigenous depopulation followed by the expansion of vegetation and an increase in carbon sequestration is repeated. However, its effects were felt globally. Ice cores from Antarctica show that c. CE 1600 a rapid (~20-50 years) decline (7-10 ppm) in atmospheric CO2 occurred (Ahn et al., 2012). At the same time (c. CE 1600-1750) biomass burning in the southern hemisphere reached a new low, only increasing again during the industrialisation of the 1800’s (Marlon et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010). Vegetation, previously held at bay by Indigenous land management recolonised the land, sequestering some 5-10 Gt C (Gigatonnes of carbon) (Nevle and Bird, 2008; Lewis and Maslin, 2015; Koch et al., 2019) driving changes in global climate, and potentially contributing to the Little Ice Age which reached its peak c. CE 1610 (Dull et al., 2010; Lewis and Maslin, 2015). However, the synchronicity of these events has been questioned as land abandonment and forest regrowth throughout Amazonia has been observed in the centuries prior to European arrival (Bush et al., 2021; Hamilton et al., 2021).

Throughout tropical South America forest recovery driven by Indigenous population decline is observable through palaeoecological proxy records (Flantua et al., 2016). In Neotropical rainforests (Bush et al., 2007; Maezumi et al., 2018; de Souza et al., 2019), savannahs (Carson et al., 2014; Brugger et al., 2016) and Andean montane forests (Chepstow-Lusty et al., 2009; Bush et al., 2015; Loughlin et al., 2018a) pollen assemblages record vegetation rebounding following depopulation, while evidence of Indigenous agriculture in the form of cultivar pollen and phytoliths e.g. Zea mays, disappears from sedimentary archives (Whitney et al., 2014; Loughlin et al., 2018a). In areas regularly burned prior to European arrival, evidence of fire disappears (Bush et al., 2008; Nevle and Bird, 2008; de Souza et al., 2019), in contrast to areas naturally prone to fires such as dry forests, where burning increased as the previously cleared forest expanded (Liebmann et al., 2016).

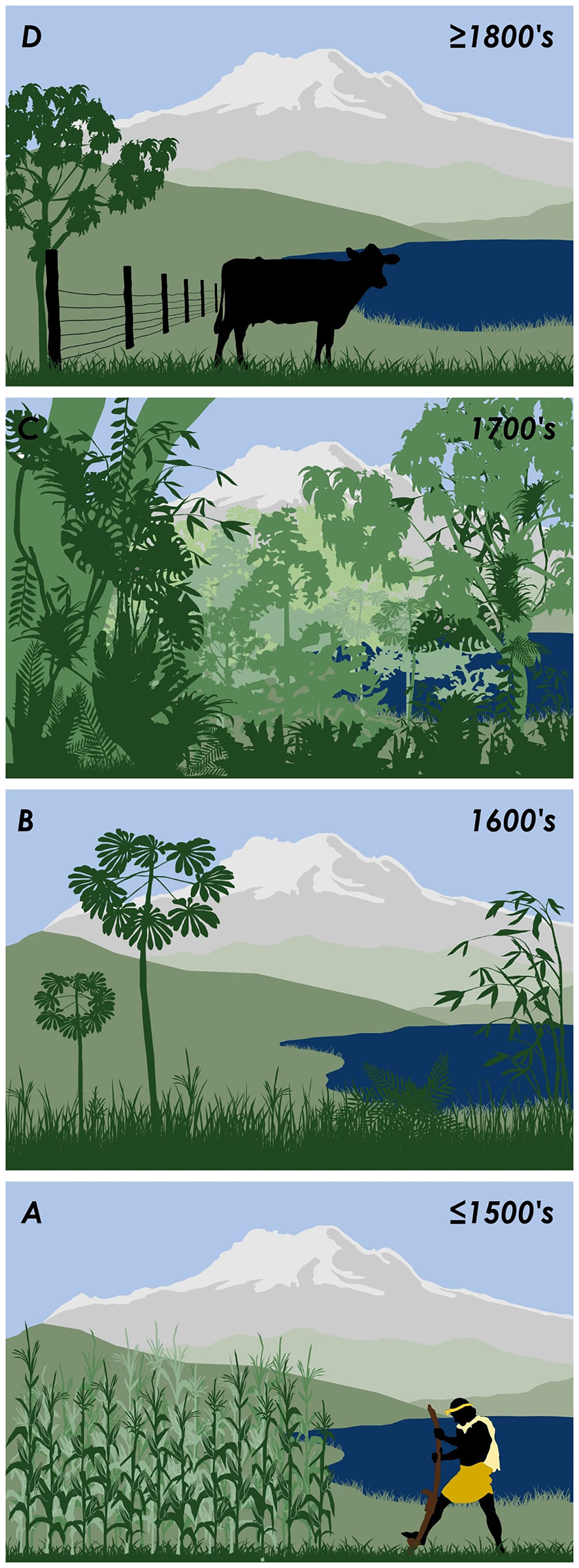

Our case study shows that abandonment of the pre- CE 1500 agricultural land (Figure 4A) lead to more than two centuries of vegetation succession through the 1600 -1700’s (Figures 4B, C) followed by modern deforestation and cattle farming post- CE1800 (Figure 4D). The 1700’s (Figure 4C) therefore provide the most recent phase of substantial mature vegetation that has undergone over a century of recovery and represents a practical palaeo-reference ecosystem. Ancient pre-human arrival records may provide more robust data when exploring issues such as species migration, adaption and extinction (Vegas-Vilarrúbia et al., 2011),while changes in climate through the late Quaternary may provide useful analogues of biotic responses to our current human driven climate (Fordham et al., 2020). However, the primary issue that limits the implementation of palaeoecology into restoration practice is ‘practicality’ and here ancient sediment becomes ‘impractical’. Ancient palaeo-reference ecosystems i.e. those established prior to human arrival in the Americas and therefore during the last ice-age are 1) unlikely to best represent the vegetation composition required today; 2) would completely eliminate any human signal, representing millennia of Indigenous selective cultivation and domestication (Levis et al., 2017); 3) the paucity of ancient sediment within the tectonically dynamic Andes and fluvially dynamic Amazon, would lead to large regions being categorised on single records; and 4) ancient sediments, requiring large lakes would produce proxy signals (particularly pollen) from a wide region, leading to a homogenisation of the local landscape signal (Jacobson and Bradshaw, 1981).

Figure 4 Summary diagram of Ecuadorian montane forest succession driven by changes in land use. (A) pre-CE 1588 Indigenous agriculture, (B) CE 1588-1718 European arrival and Indigenous depopulation leading to secondary forest growth, (C) CE 1718-1819 a diminished population and establishment of mature forest, and (D) post-CE 1819 re-colonisation of the landscape and modern farming.

The use of a recent target i.e. the 1700’s, overcomes these issues as 1) only short (< 1m) sediment cores are required, easily obtainable from frequently occurring bogs and small ponds; 2) cores can be quickly and easily recovered and dated with confidence that the required sediments are present; 3) multiple short cores focused on a narrow time frame can be examined, overcoming the issue of relying on single sites; and 4) the Indigenous land-use signal, containing taxa culturally favoured over the preceding millennia are retained. Expanding the search for practical palaeo-reference ecosystems across the Americas will likely identify differing periods for individual regions dependant on historical changes in human impact on the landscape. However, the scale of continental forest regrowth following Indigenous depopulation across the Americas occurring on a scale detectable in global climate records, provides a compelling marker. The addition of a ‘palaeo-reference ecosystem’ offers to supplement the standard ‘reference ecosystem’ approach allowing for a greater understanding of the structure and composition of local mature forests. However, it does not demand that specific species or plant communities are restored, this decision remains the purview of the restoration ecologist, land managers and stakeholders, whose mandate is to restore and rehabilitate.

There is little doubt that massive global restoration efforts are required to help mitigate anthropogenic climate change and combat deforestation (IPCC, 2018; IPBES, 2018; Chazdon and Brancalion, 2019; Dave et al., 2019). Despite this, active restoration of cleared tropical forests cannot continue to overlook the long-term impact of humans in areas where the target is to place degraded sites back onto a successional trajectory that mimics the natural dynamism of the ecosystem. It is now clear that in many regions human populations have significantly modified tropical ecosystems over thousands of years (Denevan, 1992; Heckenberger et al., 2003; Sylvester et al., 2017; Loughlin et al., 2018a; Lombardo et al., 2020; Prümers et al., 2022). However, if reference ecosystems continue to be used in restoration ecology, then the vegetation of the recent past must be incorporated into establishing practical and robust (palaeo-) reference ecosystems, that reduce the risk of recreating ecologically diminished ecosystems that today we may erroneously see as ‘natural’.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Environmental Information Data Centre (EIDC) https://doi.org/10.5285/952e8ddb-b573-44ad-a930-2c8c5164a381.

Author contributions

NL, WG, EM, and PM conducted the fieldwork. NL, WG, and EM designed the research. NL conducted the laboratory work. NL wrote the manuscript with contributions from WG, JD, FC, PM, and EM. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and The Open University through a scholarship to NL (NE/L501888/1), and a NERC fellowship to EM (NE/J018562/1). Permits for fieldwork in Ecuador were provided by the Ministry of Environment, Ecuador (14-2012-IC-FLO-DPAP-MA).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adolf C., Tovar C., Kühn N., Behling H., Berrío J. C., Dominguez-Vázquez G., et al. (2020). Identifying drivers of forest resilience in long-term records from the neotropics. Biol. Lett. 16 (4), 20200005. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2020.0005

Ahn J., Brook E. J., Mitchell L., Rosen J., McConnell J. R., Taylor K., et al. (2012). Atmospheric CO2 over the last 1000 years: A high-resolution record from the West Antarctic ice sheet (WAIS) divide ice core. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 26, GB2027, doi: 10.1029/2011GB004247

Brugger S. O., Gobet E., van Leeuwen J. F. N., Ledru M.-P., Colombaroli D., van der Knaap W. O., et al. (2016). Long-term man–environment interactions in the Bolivian Amazon: 8000 years of vegetation dynamics. Quat Sci. Rev. 132, 114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.11.001

Bush M. B., Mosblech N. A. S., Church W. (2015). Climate change and the agricultural history of a mid-elevation Andean montane forest. Holocene. 25 (9), 1522–1532. doi: 10.1177/0959683615585837

Bush M. B., Nascimento M. N., Åkesson C. M., Cárdenes-Sandí G. M., Maezumi S. Y., Behling H., et al. (2021). Widespread reforestation before European influence on Amazonia. Science 372 (6541), 484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.abf3870

Bush M. B., Restrepo A., Collins A. F. (2014). Galápagos history, restoration, and a shifted baseline. Restor. Ecol. 22 (3), 296–298. doi: 10.1111/rec.12080

Bush M. B., Silman M. R., Listopad C. M. C. S. (2007). A regional study of Holocene climate change and human occupation in Peruvian Amazonia. J. Biogeogr. 34 (8), 1342–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01704.x

Bush M. B., Silman M. R., McMichael C., Saatchi S. (2008). Fire, climate change and biodiversity in Amazonia: a late-Holocene perspective. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B Biol. Sci. 363 (1498), 1795–1802. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.0014

Carson J. F., Whitney B. S., Mayle F. E., Iriarte J., Prümers H., Soto J. D., et al. (2014). Environmental impact of geometric earthwork construction in pre-Columbian Amazonia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111 (29), 10497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321770111

Chazdon R. L. (2017). Landscape restoration, natural regeneration, and the forests of the future. Ann. Mo Bot. Gard. 102 (2), 251–257. doi: 10.3417/2016035

Chazdon R., Brancalion P. H. S. (2019). Restoring forests as a means to many ends. Science 365 (6448), 24–25. doi: 10.1126/science.aax9539

Chazdon R. L., Letcher S. G., van Breugel M., Martínez-Ramos M., Bongers F., Finegan B. (2007). Rates of change in tree communities of secondary Neotropical forests following major disturbances. Philos. Trans. R. Soc Lond. B Biol. Sci. 362 (1478), 273–289. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1990

Chepstow-Lusty A. J., Frogley M. R., Bauer B. S., Leng M. J., Boessenkool K. P., Carcaillet C., et al. (2009). Putting the rise of the Inca empire within a climatic and land management context. Clim Past 5 (3), 375–388. doi: 10.5194/cp-5-375-2009

Cuesta F., Peralvo M., Merino-Viteri A., Bustamante M., Baquero F., Freile J. F., et al. (2017). Priority areas for biodiversity conservation in mainland Ecuador. Neotropical Biodivers. 3 (1), 93–106. doi: 10.1080/23766808.2017.1295705

Dave R., Saint-Laurent C., Murray L., Antunes Daldegan G., Brouwer R., de Mattos Scaramuzza C. A., et al. (2019). “Second Bonn challenge progress report,” in Application of the barometer in 2018. gland (Switzerland: IUCN).

Denevan W. M. (1992). The pristine myth: The landscape of the americas in 1492. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 82 (3), 369–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01965.x

de Souza J. G., Robinson M., Maezumi S. Y., Capriles J., Hoggarth J. A., Lombardo U., et al. (2019). Climate change and cultural resilience in late pre-Columbian Amazonia. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3 (7), 1007–1017. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0924-0

Dull R. A., Nevle R. J., Woods W. I., Bird D. K., Avnery S., Denevan W. M. (2010). The Columbian encounter and the little ice age: Abrupt land use change, fire, and greenhouse forcing. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 100 (4), 755–771. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2010.502432

Duncan N. A., Loughlin N. J. D., Walker J. H., Hocking E. P., Whitney B. S. (2021). Pre-Columbian fire management and control of climate-driven floodwaters over 3500 years in southwestern Amazonia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118 (40), e2022206118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022206118

FAO, JRC. (2012). Global forest land-use change 1990–2005. Eds. Lindquist E. J., D’Annunzio R., Gerrand A., MacDicken K., Achard F., Beuchle R., et al (Rome: FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and European Commission Joint Research Centre) 118 (40), e2022206118.

Flantua S. G. A., Hooghiemstra H., Vuille M., Behling H., Carson J. F., Gosling W. D., et al. (2016). Climate variability and human impact in south America during the last 2000 years: synthesis and perspectives from pollen records. Clim Past. 12 (2), 483–523. doi: 10.5194/cp-12-483-2016

Fordham D. A., Jackson S. T., Brown S. C., Huntley B., Brook B. W., Dahl-Jensen D., et al. (2020). Using paleo-archives to safeguard biodiversity under climate change. Science 369 (6507), eabc5654. doi: 10.1126/science.abc5654

Gann G. D., McDonald T., Walder B., Aronson J., Nelson C. R., Jonson J., et al. (2019). International principles and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. second edition. Restor. Ecol. 27 (S1), S1–S46. doi: 10.1111/rec.13035

Gentry A. H. (1995). “Patterns of diversity and floristic composition in Neotropical montane forests,” in Biodivers conserv Neotropical montane for. Eds. Churchill S. P., Balslev H., Forero E., Luteyn J. L. (New York: The New York Botanical Garden), 103–126.

Gillson L., Marchant R. (2014). From myopia to clarity: sharpening the focus of ecosystem management through the lens of palaeoecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29 (6), 317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.03.010

Grubb P. J., Lloyd J. R., Pennington T. D., Páez-Bimos S. (2020). A historical baseline study of the páramo of antisana in the Ecuadorian Andes including the impacts of burning, grazing and trampling. Plant Ecol. Divers. 13 (3-4), 225–256. doi: 10.1080/17550874.2020.1819464

Guariguata M. R., Ostertag R. (2001). Neotropical Secondary forest succession: changes in structural and functional characteristics. For Ecol. Manage. 148 (1), 185–206. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00535-1

Hamilton R., Wolfhagen J., Amano N., Boivin N., Findley D. M., Iriarte J., et al. (2021). Non-uniform tropical forest responses to the ‘Columbian exchange’ in the neotropics and Asia-pacific. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1174–1184. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01474-4

Hansen A., Barnett K., Jantz P., Phillips L., Goetz S. J., Hansen M., et al. (2019). Global humid tropics forest structural condition and forest structural integrity maps. Sci. Data. 6 (1), 232. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0214-3

Heckenberger M. J., Kuikuro A., Kuikuro U. T., Russell J. C., Schmidt M., Fausto C., et al. (2003). Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest or Cultural Parkland? Science. 301 (5640), 1710–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.1086112

Heilmayr R., Echeverría C., Lambin E. F. (2020). Impacts of Chilean forest subsidies on forest cover, carbon and biodiversity. Nat. Sustain. 3, 701–709. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0547-0

Holl K. D. (2017). Restoring tropical forests from the bottom up. Science 355 (6324), 455–456. doi: 10.1126/science.aam5432

Humans for Abundance (2020). Available at: https://www.humansforabundance.com/ (Accessed 2020 Aug 30).

IPBES (2018). The IPBES assessment report on land degradation and restoration. Eds. Montanarella L., Scholes R., Brainich A. (Bonn, Germany: IPBES Secretariat).

IPCC (2018). “Summary for policymakers,” in Glob warm 15°C IPCC spec rep impacts glob warm 15°C pre-ind levels relat glob greenh gas emiss pathw context strength glob response threat clim change sustain dev efforts eradicate poverty. Eds. Masson-Delmotte V., Zhai P., Pörtner H.-O., Roberts D., Skea J., Shukla P. R., et al (Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization).

Jackson S. T., Hobbs R. J. (2009). Ecological restoration in the light of ecological history. Science 325 (5940), 567–569. doi: 10.1126/science.1172977

Jacobson G. L., Bradshaw R. H. W. (1981). The selection of sites for paleovegetational studies. Quat Res. 16 (1), 80–96. doi: 10.1016/0033-5894(81)90129-0

Jameson W. (1858). Excursion made from Quito to the river napo, January to may 1857. J. R Geogr. Soc. Lond. 28, 337–349. doi: 10.2307/1798328

Keenleyside K. A., Dudley N., Cairns S., Hall C. M., Stolton S. (2012). Ecological restoration for protected areas: principles, guidelines and best practices (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN).

Koch A., Brierley C., Maslin M. M., Lewis S. L. (2019). Earth system impacts of the European arrival and great dying in the americas after 1492. Quat Sci. Rev. 207, 13–36. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004

Levis C., Costa F. R. C., Bongers F., Peña-Claros M., Clement C. R., Junqueira A. B., et al. (2017). Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on Amazonian forest composition. Science 355 (6328), 925–931. doi: 10.1126/science.aal0157

Lewis S. L., Maslin M. A. (2015). Defining the anthropocene. Nature 519 (7542), 171–180. doi: 10.1038/nature14258

Liebmann M. J., Farella J., Roos C. I., Stack A., Martini S., Swetnam T. W. (2016). Native American depopulation, reforestation, and fire regimes in the southwest united states 1492–1900 CE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113 (6), E696–E704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521744113

Loughlin N. J. D., Gosling W. D., Coe A. L., Gulliver P., Mothes P., Montoya E. (2018b). Landscape-scale drivers of glacial ecosystem change in the montane forests of the eastern Andean flank, Ecuador. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 489, 198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.10.011

Loughlin N. J. D., Gosling W. D., Mothes P., Montoya E. (2018a). Ecological consequences of post-Columbian indigenous depopulation in the Andean–Amazonian corridor. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2 (8), 1233–1236. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0602-7

Lombardo U., Iriarte J., Hilbert L., Ruiz-Pérez J., Capriles J. M., Veit H. (2020). Early Holocene crop cultivation and landscape modification in Amazonia. Nature 581, 190–193. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2162-7

Maezumi S. Y., Robinson M., de Souza J., Urrego D. H., Schaan D., Alves D., et al. (2018). New insights from pre-Columbian land use and fire management in Amazonian dark earth forests. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6 (111), 1–23. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00111

Marlon J. R., Bartlein P. J., Carcaillet C., Gavin D. G., Harrison S. P., Higuera P. E., et al. (2008). Climate and human influences on global biomass burning over the past two millennia. Nat. Geosci. 1 (10), 697–702. doi: 10.1038/ngeo313

Martin P. A., Newton A. C., Bullock J. M. (2013). Carbon pools recover more quickly than plant biodiversity in tropical secondary forests. Proc. R Soc. B Biol. Sci. 280 (1773), 20132236. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2236

Meyer C., Kreft H., Guralnick R., Jetz W. (2015). Global priorities for an effective information basis of biodiversity distributions. Nat. Commun. 6 (1), 8221. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9221

Montoya E., Lombardo U., Levis C., Aymard G. A., Mayle F. E. (2020). “Human contribution to Amazonian plant diversity: legacy of pre-Columbian land use in modern plant communities,” in Neotropical Diversification: patterns and processes. Eds. Rull V., Carvajal A. C. (Switzerland: Springer Nature), 495–520.

Myers N., Mittermeier R. A., Mittermeier C. G., da Fonseca G. A. B., Kent J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403 (6772), 853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501

Nevle R. J., Bird D. K. (2008). Effects of syn-pandemic fire reduction and reforestation in the tropical americas on atmospheric CO2 during European conquest. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 264 (1), 25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.03.008

Newson L. A. (1995). Life and death in early colonial Ecuador (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Oksanen J., Blanchet F. G., Friendly M., Kindt R., Legendre P., McGlinn D. (2019). Vegan: Community ecology package. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria.

Pauly D. (1995). Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10 (10), 430. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)89171-5

Poorter L., Bongers F., Aide T. M., Almeyda Zambrano A. M., Balvanera P., Becknell J. M., et al. (2016). Biomass resilience of Neotropical secondary forests. Nature 530 (7589), 211–214. doi: 10.1038/nature16512

Prümers H., Betancourt C.J., Iriarte Robinson J. M., Schaich M. (2022). Lidar reveals pre-Hispanic low-density urbanism in the Bolivian Amazon. Nature 606, 325–328. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04780-4

R Core Team (2020). R: a language and environment for statistical computing (Austria, Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

REDD+ Early Movers Program (2020). Available at: https://www.un-redd.org/ (Accessed 2020 Aug 30).

Rozendaal D. M. A., Bongers F., Aide T. M., Alvarez-Dávila E., Ascarrunz N., Balvanera P., et al. (2019). Biodiversity recovery of Neotropical secondary forests. Sci. Adv. 5 (3), eaau3114. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau3114

Seddon A. W. R., Mackay A. W., Baker A. G., Birks H. J. B., Breman E., Buck C. E., et al. (2014). Looking forward through the past: identification of 50 priority research questions in palaeoecology. J. Ecol. 102 (1), 256–267. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12195

Soga M., Gaston K. J. (2018). Shifting baseline syndrome: causes, consequences, and implications. Front. Ecol. Environ. 16 (4), 222–230. doi: 10.1002/fee.1794

Swetnam T. W., Allen C. D., Betancourt J. L. (1999). Applied historical ecology: using the past to manage for the future. Ecol. Appl. 9 (4), 1189–1206. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(1999)009[1189:AHEUTP]2.0.CO;2

Sylvester S. P., Heitkamp F., Sylvester M. D. P. V., Jungkunst H. F., Sipman H. J. M., Toivonen J. M., et al. (2017). Relict high-Andean ecosystems challenge our concepts of naturalness and human impact. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 3334. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03500-7

The Bonn Challenge (2020). Available at: https://www.bonnchallenge.org/ (Accessed 2020 Aug 30).

United Nations (2020) The UN decade on ecosystem restoration 2021-2030. Available at: https://www.decadeonrestoration.org/ (Accessed 2020 Aug 30).

Uzendoski M. A. (2004). The horizontal archipelago: the Quijos/Upper napo regional system. Ethnohistory 51 (2), 317–357. doi: 10.1215/00141801-51-2-317

Vegas-Vilarrúbia T., Rull V., Montoya E., Safont E. (2011). Quaternary palaeoecology and nature conservation: a general review with examples from the neotropics. Quat Sci. Rev. 30 (19), 2361–2388. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.05.006

Wang Z., Chappellaz J., Park K., Mak J. E. (2010). Large Variations in southern hemisphere biomass burning during the last 650 years. Science 330 (6011), 1663–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.1197257

Webster G. L. (1995). “The panorama of neotropical cloud forests,” in Biodivers conserv Neotropical montane for. Eds. Churchill S. P., Balslev H., Forero E., Luteyn J. L. (New York: The New York Botanical Garden), 53–77.

Whitlock C., Colombaroli D., Conedera M., Tinner W. (2018). Land-use history as a guide for forest conservation and management. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 32 (1), 84–97. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12960

Whitney B. S., Dickau R., Mayle F. E., Walker J. H., Soto J. D., Iriarte J. (2014). Pre-Columbian raised-field agriculture and land use in the Bolivian Amazon. Holocene. 24 (2), 231–241. doi: 10.1177/0959683613517401

Keywords: Neotropics, Andes, restoration, deforestation, palaeoecology, pollen, reference ecosystem, palaeo-reference ecosystem

Citation: Loughlin NJD, Gosling WD, Duivenvoorden JF, Cuesta F, Mothes P and Montoya E (2022) Incorporating a palaeo-perspective into Andean montane forest restoration. Front. Conserv. Sci. 3:980728. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2022.980728

Received: 28 June 2022; Accepted: 12 August 2022;

Published: 02 September 2022.

Edited by:

Rob Marchant, University of York, United KingdomReviewed by:

Janelle Stevenson, Australian National University, AustraliaRachel Atkinson, Bioversity International, Peru

Copyright © 2022 Loughlin, Gosling, Duivenvoorden, Cuesta, Mothes and Montoya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicholas J. D. Loughlin, bmljaG9sYXMubG91Z2hsaW5Abm9ydGh1bWJyaWEuYWMudWs=

Nicholas J. D. Loughlin

Nicholas J. D. Loughlin William D. Gosling

William D. Gosling Joost F. Duivenvoorden2

Joost F. Duivenvoorden2 Francisco Cuesta

Francisco Cuesta Patricia Mothes

Patricia Mothes Encarni Montoya

Encarni Montoya