95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Conserv. Sci. , 23 August 2022

Sec. Human-Wildlife Interactions

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2022.954930

This article is part of the Research Topic Impacts of People's Engagement in Nature Conservation View all 8 articles

Nathan J. Bennett1,2*

Nathan J. Bennett1,2* Molly Dodge1

Molly Dodge1 Thomas S. Akre1,3

Thomas S. Akre1,3 Steven W. J. Canty1,4

Steven W. J. Canty1,4 Rafael Chiaravalloti1,3

Rafael Chiaravalloti1,3 Ashley A. Dayer5

Ashley A. Dayer5 Jessica L. Deichmann1,3

Jessica L. Deichmann1,3 David Gill6

David Gill6 Melanie McField1,4

Melanie McField1,4 James McNamara3,7

James McNamara3,7 Shannon E. Murphy8

Shannon E. Murphy8 A. Justin Nowakowski1,8

A. Justin Nowakowski1,8 Melissa Songer1,3

Melissa Songer1,3Biodiversity is in precipitous decline globally across both terrestrial and marine environments. Therefore, conservation actions are needed everywhere on Earth, including in the biodiversity rich landscapes and seascapes where people live and work that cover much of the planet. Integrative landscape and seascape approaches to conservation fill this niche. Making evidence-informed conservation decisions within these populated and working landscapes and seascapes requires an in-depth and nuanced understanding of the human dimensions through application of the conservation social sciences. Yet, there has been no comprehensive exploration of potential conservation social science contributions to working landscape and seascape initiatives. We use the Smithsonian Working Land and Seascapes initiative – an established program with a network of 14 sites around the world – as a case study to examine what human dimensions topics are key to improving our understanding and how this knowledge can inform conservation in working landscapes and seascapes. This exploratory study identifies 38 topics and linked questions related to how insights from place-based and problem-focused social science might inform the planning, doing, and learning phases of conservation decision-making and adaptive management. Results also show how conservation social science might yield synthetic and theoretical insights that are more broadly applicable. We contend that incorporating insights regarding the human dimensions into integrated conservation initiatives across working landscapes and seascapes will produce more effective, equitable, appropriate and robust conservation actions. Thus, we encourage governments and organizations working on conservation initiatives in working landscapes and seascapes to increase engagement with and funding of conservation social science.

Biodiversity and ecosystem services are in precipitous decline across terrestrial and marine systems on a global scale (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005; McCauley et al., 2015; Tanzer et al., 2015; Díaz et al., 2019; IPBES, 2019; Almond et al., 2020). These declines are having dramatic impacts on human society and well-being, including economic benefits and livelihoods, food production and security, cultural knowledge and practices, and vulnerability to natural hazards and climate change (IPCC, 2014; Díaz et al., 2019; IPBES, 2019). It is abundantly clear that conservation actions are urgently needed everywhere on earth - from mountain ecosystems to the oceans, and from wilderness areas to urban environments - to sustain ecosystems, maintain ecosystem services, and support human well-being (United Nations, 2015).

Yet, the approaches that society takes to conservation will need to be tailored to different conditions. For example, 26.5% of the earth’s terrestrial environment can be classified as “large wild areas”, which are sparsely populated; 17.7% as “cities and farms”, which are more populated and intensively used by humans; and 55.7% as “shared lands”, which are characterized by mixed uses and an intermediate number of people (Locke et al., 2019). Human presence and intensity of influence varies significantly across these landscape types (Riggio et al., 2020). Population density and level of human use also varies substantially across the world’s oceans - ranging from areas of “marine wilderness” or the high seas which are fished but generally less anthropogenically impacted, to coastal areas that are highly populated and more readily accessed and impacted by communities, resource users, and industrial activities (Halpern et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2018; Bennett, 2019). While there has been a historical tendency in the conservation community to think that biodiversity conservation efforts should focus on creating protected areas in less populated or wilderness areas (Sloan, 2002; Wilson, 2016; Jones et al., 2018; Pimm et al., 2018), much of the world’s biodiversity and ecosystems are found in the substantial portion of the world’s landscapes and seascapes that are more heavily used, inhabited, and influenced by human populations (Tittensor et al., 2010; Locke et al., 2019; Riggio et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). In these working landscapes and seascapes, there is a need to engage in broad scale and holistic approaches to conservation that integrate the needs of and promote benefits for both people and nature (Sayer et al., 2013; Carmenta et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2020a; Murphy et al., 2021). Adopting such integrated approaches to conservation will be vital to achieving global goals for conservation and development (e.g., as specified in the United Nations (UN) Convention on Biological Diversity, UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and UN Sustainable Development Goals) (Reed et al., 2020b; Murphy et al., 2021).

There are numerous examples of integrative conservation models (e.g., Biosphere Reserves, World Heritage Sites, Ridge to Reef Initiatives, Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs) (Jonas et al., 2014; Gurney et al., 2021)) and environmental management approaches (e.g., Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM), the Ecosystem Approach (EA), Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)) that might be applied in populated and multiple use contexts. One approach that has been broadly promoted and applied by different governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and global policy organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an integrated or working landscape and seascape approach to conservation (Mangubhai et al., 2012; Sayer et al., 2013; Kavanaugh et al., 2016; Reed et al., 2016; Kremen and Merenlender, 2018; Deichmann et al., 2019; Carmenta et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2020a; Murphy et al., 2021).

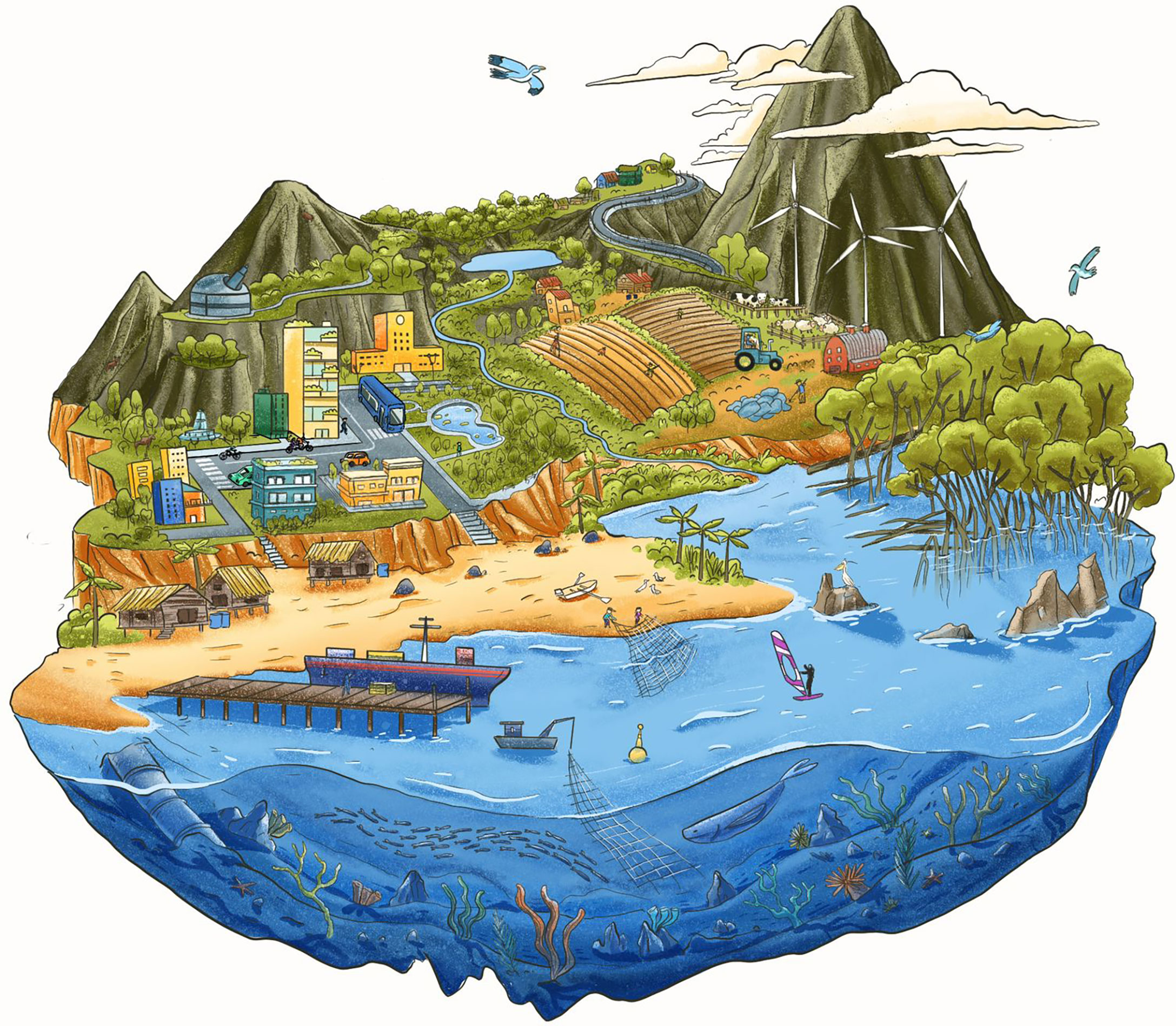

Due to the broad number of organizations and governments adopting integrated landscape and seascape approaches to conservation, a singular definition remains elusive (Bensted-Smith and Kirkman, 2010; Reed et al., 2016). In essence, working landscapes and seascapes can be defined as mosaics of natural areas, managed ecosystems, communities, uses, and infrastructures that provide ecosystem services (e.g., food, water, fiber, and fuel) and support human activities including agriculture, fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, transportation, and energy production (Kavanaugh et al., 2016; Kremen and Merenlender, 2018; Deichmann et al., 2019; Murphy et al., 2021). A stylized depiction of working landscapes and seascapes is also shown in Figure 1. Integrated approaches to conservation in working landscapes and/or seascapes focus on holistic management and sustainable use of natural resources in order to maintain and/or restore biodiversity and ecosystem services as the foundation of livelihoods and human well-being (Sayer et al., 2013; Carmenta et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2020a; Murphy et al., 2021). Defining characteristics of integrated landscape and seascape approaches to conservation include a holistic and integrative focus, multiple users and conservation actions, inclusive and coordinated governance, and effective and robust management (Table 1). These general characteristics and principles, of course, need to be adapted to different social, economic and political realities and applied projects (e.g., agro-forestry or Reef to Ridge projects) (Sayer et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2021).

Figure 1 Stylized depiction of integrated conservation in interconnected working landscapes and seascapes. The image shows how working landscapes and seascapes are mosaics of natural areas, managed ecosystems, communities, uses, and infrastructures that provide ecosystem services (e.g., food, water, fiber, and fuel) and support human activities. Conservation in working landscapes and seascapes is characterized by holistic management, integrative thinking, multiple conservation actions, sustainable uses, inclusive processes and coordinated governance, in order to effectively maintain and/or restore biodiversity and ecosystem services as the foundation of livelihoods and human well-being. (Credit: Max Jake Palomino - Instagram @jakeilus).

It is often claimed by conservation scientists that conservation decisions, management and policy should be evidence-based or evidence-informed (Sutherland et al., 2004; Adams and Sandbrook, 2013; Legge, 2015) and that conservation evidence base should include an understanding of both the environmental and human aspects of the social-ecological systems (Ban et al., 2013; Guerrero and Wilson, 2016; Levin et al., 2016). As people and social processes are at the core of integrated landscape and seascape approaches to conservation (Sayer et al., 2013; Kremen and Merenlender, 2018; Murphy et al., 2021), insights from the social sciences are essential to address the social and governance complexities of working with multiple stakeholders, interests and institutions at the scale of landscapes or seascapes. Thus, conservation agencies and organizations working in landscapes and seascapes need to invest in and engage with insights from both the natural and social sciences to design effective, equitable, and robust initiatives (Mangubhai et al., 2015; Bennett et al., 2017b; Brockington et al., 2018; Bennett, 2019; Murphy et al., 2021). Yet, social science contributions are often undervalued and underrepresented in landscape and seascape approaches (Brockington et al., 2018). Our focus here is to inform such engagements through examining specific roles and contributions of the social sciences to conservation efforts (e.g., decision-making, planning and management) in working landscape and seascape initiatives. The conservation social sciences include a broad set of disciplines, theories, methods and analytical approaches that can be used to provide insights related to the human dimensions (i.e., a general term that refers to social, cultural, economic, health, political and governance aspects) of environmental challenges and management (Newing et al., 2011; Sandbrook et al., 2013; Bennett et al., 2017a; Niemiec et al., 2021).

A number of past papers have called for more attention to the social sciences in conservation (Mascia et al., 2003; Sandbrook et al., 2013; Bennett et al., 2017b), and there have been numerous explorations of the human dimensions of specific conservation issues, such as human-wildlife interactions (Bruskotter and Shelby, 2010; Decker et al., 2012), private land conservation (Knight et al., 2010; Prokopy et al., 2019), river management (Dunham et al., 2018), invasive species (Head, 2017), bird conservation (Dayer et al., 2020), insect conservation (Hall and Martins, 2020), marine protected areas (Charles and Wilson, 2009; Christie et al., 2017), and ecological restoration (Egan et al., 2012; Stanturf et al., 2012). Within the context of working landscapes or seascapes, quite a few papers also focus on specific conservation social science topics, including culture (Poe et al., 2014; Cuerrier et al., 2015; Brown and Hausner, 2017), social networks (Cohen et al., 2012; Bixler et al., 2016; Zinngrebe et al., 2020), and governance (Nagendra and Ostrom, 2012; den Uyl and Driessen, 2015; Imperial et al., 2016; Boucquey, 2020; Chiaravalloti et al., 2021) to name a few. Yet, based on our review and knowledge of the literature, there has been no comprehensive exploration of potential conservation social science contributions to working landscape and seascape initiatives.

In this exploratory paper, we aim to fill this niche by asking: “What social science topics and questions are key to improving our understanding of the human dimensions of conservation in working landscapes and seascapes?” and “How can this knowledge of the human dimensions inform conservation decision-making and management in working landscapes and seascapes?” We examine this question using the Smithsonian Working Land and Seascapes (WLS) initiative as a case study, as it provides an established global program and network of conservation project sites focused on both terrestrial and marine environments.

Working Land and Seascapes (WLS) is a multidisciplinary initiative of the Smithsonian Institution, a complex of 21 museums, nine research centers, the National Zoo, and global field sites for research and conservation. The WLS mission is to foster healthy, resilient and productive land and seascapes for the benefit of people and nature. The initiative seeks to achieve this mandate through the application of science, as well as broader engagements with and capacity development of partners to provide insights from science to inform and improve conservation policy and practice (Canty et al., 2022). Partners include individuals and organizations in communities, governments, non-governmental organizations, universities, and the private sector. The long-term goal of WLS is to ensure that proposed conservation initiatives are supported by a holistic understanding of the human-nature dynamic to increase efficacy, equity and durability of interventions.

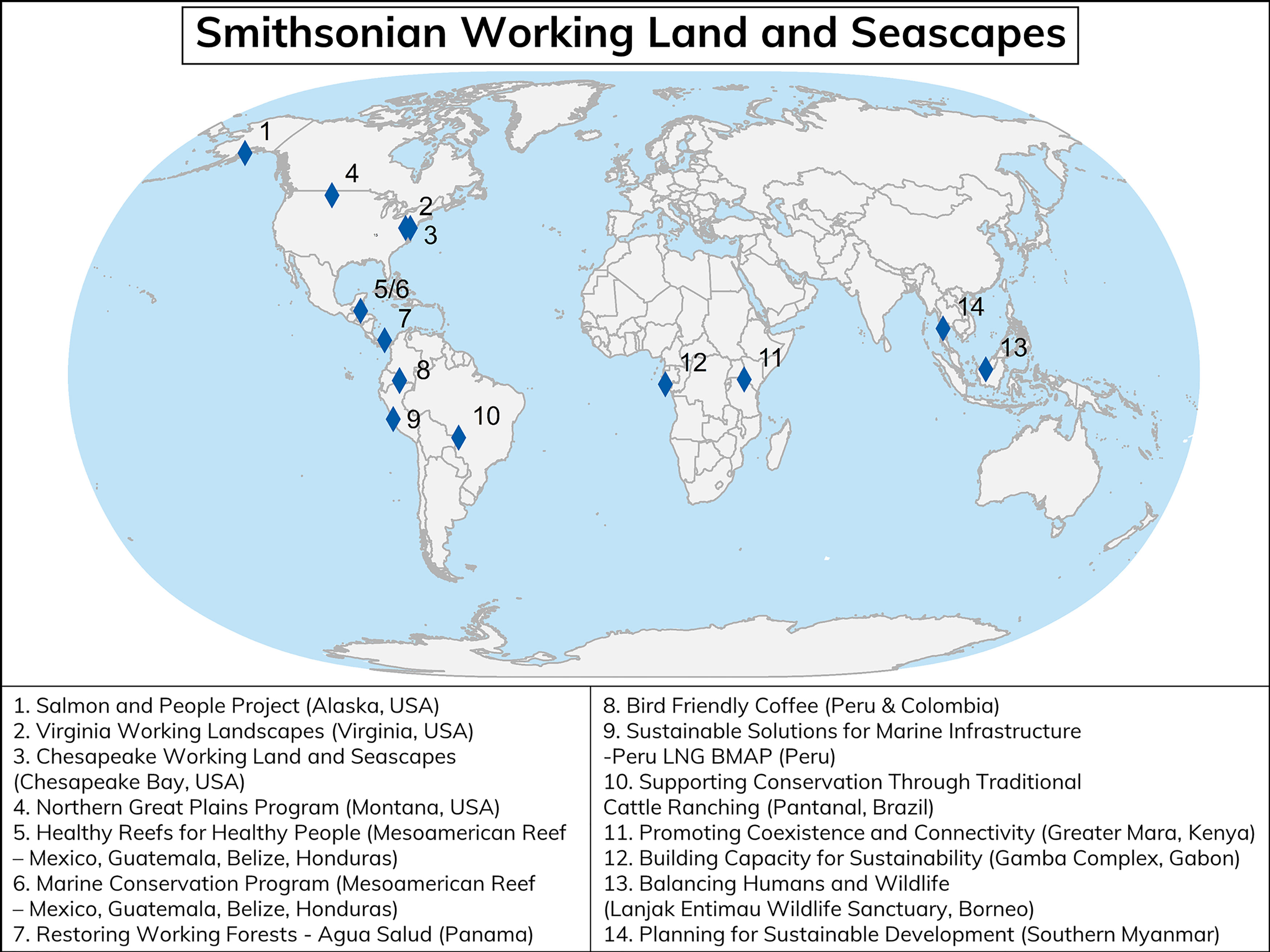

The WLS initiative currently supports 14 projects that span 13 countries (Figure 2, see https://wls.si.edu and (Canty et al., 2022) for more information on projects). In each location, WLS conducts research and works with partners to mitigate human impacts and protect or restore species and ecosystems ranging from coral reefs to grasslands to tropical forests. Conservation challenges in these diverse regions of the world are complex and have to contend with social and economic issues related to equity, governance, livelihoods, policy, and management. As all of these projects occur in landscapes and seascapes where people live and work, there is a need to apply and engage with insights from both natural and social sciences to achieve conservation success.

Figure 2 Map of locations of Smithsonian Institution’s Working Land and Seascape Initiative projects (Credit: Craig Fergus).

To understand social science topics of interest and relevance across the Smithsonian WLS, we conducted a series of qualitative key informant interviews with 2-3 representatives working in a selection of 14 WLS project sites. The research project and methods described below were reviewed by the Smithsonian Institution Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (Protocol # HS21008). A key informant interview approach was chosen as it is appropriate for such an exploratory study (Denzin, 2003; Drury et al., 2011). The semi-structured interview (Kallio et al., 2016) was guided by a set of open-ended questions co-designed by the lead author with the research team. Interview questions were related to the project background, social and environmental objectives, conservation activities and outcomes, strengths and barriers to success, pertinent social issues and human dimensions topics, current and ongoing social science research, social science knowledge gaps, needs and priorities, and capacity strengths and needs (see Supplementary Materials for the interview questions). Two to three (2-3) key informant interviewees were purposefully sampled in each of the 14 Smithsonian WLS sites (total n=30). Key informants were selected to include at least one researcher associated with the Smithsonian WLS initiative and one representative from a local organization - both of whom were engaged in or knowledgeable of conservation of the landscape or seascape at the site. Interviewees were contacted and invited to participate via email. All interviews were conducted by the lead author via phone (n=4) or on a virtual meeting platform (n=26) between March and May 2021. Interviews took between 30 - 150 minutes. We note that our remote study design and research strategy was influenced by the COVID pandemic.

Results from the interviews were transcribed verbatim, except for one interview that was conducted in Spanish and translated. The lead author then carried out an initial round of open-coding - meaning that themes were allowed to emerge from the data (Benaquisto, 2008) - to identify key social science questions and topics (e.g., human well-being, governance, social networks, etc.) from the combined qualitative data set. A second review of all of the interview transcripts was then undertaken to identify additional questions related to each of the key social science topics and any new topics. By the end, thematic saturation was reached, meaning that no new topics were emerging during analysis of the final interviews (Strauss, 1987). During the process, topics were further lumped into similar and split into discrete categories based on the nature and focus of the questions. Finally, similar questions were combined together.

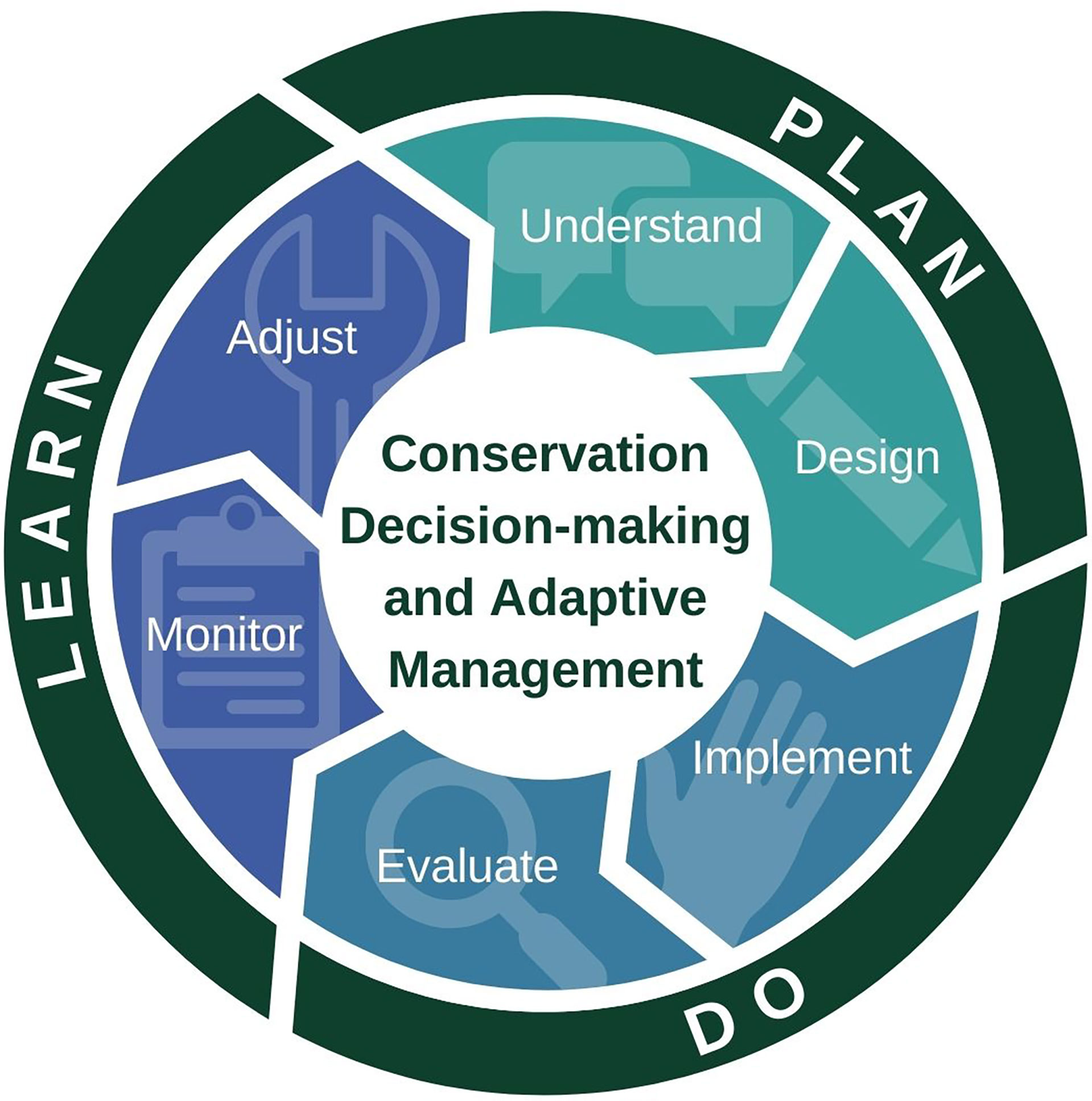

While this thematic analysis helped us to answer our first research question, an additional layer of categorization was required to better show and communicate how and when insights from conservation social science could be applied to conservation decision-making and management in working landscapes and seascapes. Thus, the social science topics and related questions were subsequently categorized into the “plan”, “do”, and “learn” stages of the adaptive management cycle (Figure 3; Adapted from ESSA, 2022). Adaptive management refers to a proactive and iterative process of decision-making that is guided by various forms of knowledge (e.g., natural science, social science, traditional knowledge), collective learning and deliberative processes to re-orient management to changing conditions (Holling, 1977; Walters, 1986; Williams, 2011; Allen and Garmestani, 2015). The general stages of adaptive management were used to categorize the results because it is a commonly applied process and framework in environmental conservation and management initiatives, ranging from protected areas to river basin to wildlife to fisheries management (Walters, 1986; Uychiaoco et al., 2005; Hockings et al., 2006; Ban et al., 2012; Allen and Garmestani, 2015). It is also promoted as a characteristic of integrated landscape and seascape initiatives (Sayer et al., 2013; Carmenta et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2020a; Murphy et al., 2021).

Figure 3 Integrating the elements of social science into the planning, doing, and learning phases of conservation decision-making and adaptive management (Credit: Sarah Wheedleton; Adapted from ESSA, 2022).

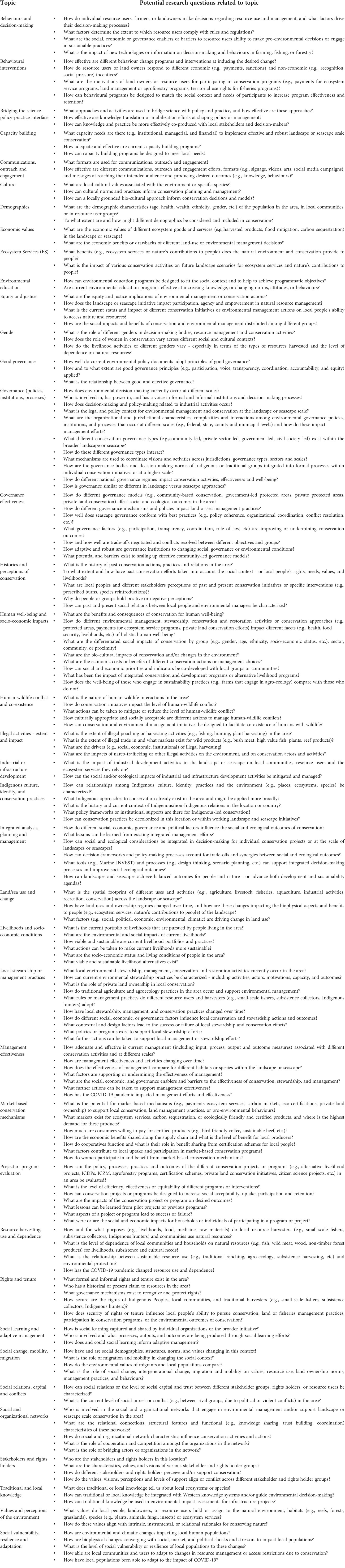

This exploratory study identifies 38 topics and linked questions related to how insights from social science might inform the planning, doing, and learning phases of conservation decision-making and adaptive management (see Tables 2, 3). However, we also found that potential conservation social science research topics focused on working landscapes and seascapes fell into two overarching categories: 1) those with a place-based or problem-focused orientation and 2) those with a synthetic or theoretical orientation. We define place-based or problem-focused conservation social science research projects as those that seek to respond to a context or project specific conservation problem and to produce insights and solutions that could be readily applied during the planning, doing, and learning phases of conservation decision-making and adaptive management (Bennett et al., 2017b). Projects with a theoretical or synthetic orientation are those that are curiosity driven or aim to produce generalizable insights that are broadly applicable beyond the scale of an individual project or location (Sandbrook et al., 2013). Thus, we present results related to each category below while recognizing that these two categories are not mutually exclusive, as social science research projects may contain elements of both, but the differentiation is useful for heuristic and analytical purposes.

Table 2 Overview of social science topics that emerged from the interviews organized by their contribution to planning, doing and learning stages of conservation decision-making and adaptive management.

Table 3 Potential questions linked to key social science topics related to conservation in working landscapes and seascapes (topics are listed alphabetically, questions were identified from key informant interviews).

The analysis and categorization process suggests that social science research projects with a place-based or problem-focused orientation have the potential to make unique contributions to the three stages of conservation decision-making and adaptive management in working landscapes and seascapes as follows:

1. Planning: Understanding the social context and designing conservation approaches, plans, and management to match;

2. Doing: Evaluating and improving implementation of conservation policies, processes and activities; and,

3. Learning: Monitoring impacts and adjusting actions to improve the ecological and/or social outcomes of conservation.

Below, we discuss results related to social science topics and questions for each of these place-based or problem-focused contributions (Planning; Doing; Learning). The topics are also summarized in Table 2, while Table 3 provides an overview of potential questions related to each topic.

Results showed how the conservation social sciences can contribute to conservation through improving understanding of the local social context where conservation is taking place and shaping conservation approaches, plans, and management. In other words, participants emphasized how knowledge of the human dimensions can be used to ensure that the institutions and strategies of conservation fit the attributes of the social context. Interviewees often discussed how foundational information about the social context includes knowledge of the characteristics of and interactions among stakeholders and rights holders, as well as demographics (e.g., age, health, wealth, ethnicities, gender, etc.) of the population or specific groups, within a landscape or seascape. Research into the values and visions of different stakeholders, rights holders and groups (e.g., genders, ethnic groups, livelihood groups, etc.) was seen as a means to work with these groups and to design conservation initiatives and management interventions that would be socially acceptable and culturally appropriate. Interviewees felt the design of conservation programs or interventions could benefit from knowledge of the factors that shape the decision-making processes of different groups (e.g., farmers, small-scale fishers, industrial sector, etc.) and the reasons that they adopt certain pro-environmental or destructive behaviours, engage in programs, or comply with regulations. Conservation decisions might also be informed by a solid understanding of various aspects of the broader economic (e.g., current livelihoods and socio-economic conditions), social (e.g., the quality of social relations and amount of conflict in the area, and levels of social vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation practices), or institutional (e.g., pre-existing rights and informal tenure) context. Understanding and embedding culture - norms, values and practices - into conservation was mentioned often in the interviews. Specific attention was also paid in many interviews to the need to specifically explore and incorporate Indigenous culture, visions and practices into conservation models and practices.

An understanding of human-environment interactions in both the past and present was also seen as fundamental to making good conservation decisions. Many participants discussed how social science methods could be applied to examine the relationship between local people and their environment, including a) levels of resource harvesting, use and dependence, b) values and perceptions associated with the environment or species, and c) the extent and impact of illegal activities (e.g., bushmeat hunting, harvesting of endangered species, fishing, narco-trafficking). It was also felt that it could be useful to examine how and why these human-environment relationships had changed over time, including through studies on changing landscape and seascape uses of resources and impacts on the landscape or seascape and how social change, mobility and migration influences values, resource use, and illegal activities. Interviewees often emphasized the need to not make assumptions about conservation practices in the area, and thus the need to characterize the types of local stewardship, management, restoration, and conservation activities that are already occurring and to examine the history and perceptions of conservation governance and actions. Several interviewees touched on the importance of understanding gendered differences in resource use and involvement in conservation. Some also discussed how studies of traditional or local knowledge of the environment could be used to inform planning and management. Finally, many interview participants emphasized the importance of combining the different social, cultural, economic and governance considerations with ecological values (e.g., through focusing on economic values or ecosystem services) into integrated conservation planning and management.

The research also demonstrated how social sciences can contribute to conservation through helping to understand, evaluate, and improve conservation policies, processes, and activities. Across most sites, interviewees discussed the importance of understanding various aspects of governance policies, institutions, and processes. This included, for example, exploring how decisions are made, who is involved in decision-making, policy frameworks and jurisdictional complexities, coordination mechanisms, or the governance types (i.e., community-led, private-sector led, government-led, civil-society led) in the landscape or seascape. Similarly, participants mentioned there was a need to characterize and evaluate the adoption of good governance practices, such as participation, voice, transparency, coordination, accountability, and equity, as well as social learning and adaptive management processes. Results also suggested that insights could be gained from examining the membership, structure, and functioning of both formal and informal social and organizational networks involved in different environmental management activities, conservation initiatives, or landscape/seascape governance.

Interviewees often discussed the importance of characterizing and evaluating conservation supporting activities, including capacity building initiatives, environmental education programs, as well as public communications and outreach efforts. The use of social science to examine the design, uptake and effectiveness of behavioural interventions for different resource user groups (e.g., fishers, farmers, private landowners) and industrial actors was also mentioned in many interviews. Many natural scientists who were interviewed were concerned with the effectiveness of current and potential efforts to bridge the science-policy-practice interface - which included knowledge translation, mobilization, and co-production practices for and with a variety of government, non-governmental, and industrial actors. Finally, interviews often touched on the usefulness of economic and social research into the market potential, design, effectiveness and equitability of market-based conservation mechanisms, such as payments for ecosystem service programs, carbon markets, and certification schemes (e.g., for bird friendly coffee, sustainable beef, fisheries certifications).

The research provided insights into how the conservation social sciences can contribute through helping to understand the social and/or ecological outcomes of conservation, as well as the factors that are producing these outcomes and what improvements might be made. Many interviewees mentioned the need to understand the social outcomes of conservation actions and decisions, through research on the economic values of different ecosystem goods and services or the impacts of conservation actions on human well-being or socio-economic indicators. The equity and justice implications of conservation was also mentioned by a number of interview participants, with consideration given to both procedural (participation, agency, empowerment) and distributional (fairness of costs and benefits to different groups) dimensions. Participants suggested that while understanding ecological outcomes is primarily the realm of natural science, social science methods might be employed to study traditional knowledge about the ecological outcomes of conservation, or to evaluate levels of management or governance effectiveness.

Nonetheless, interviewees often placed emphasis on the need to simultaneously understand both social and ecological outcomes, through conducting research on levels of human-wildlife conflict and coexistence, using biocultural indicators for human well-being, or tracking how different planning and management decisions have impacted the ecosystem services (or Nature’s Contributions to People) that people rely on. Interdisciplinary indicators and analysis, interview participants felt, were necessary to be able to identify trade-offs and synergies and pursue the multiple social and ecological objectives inherent in landscape or seascape approaches.

Interviewees also mentioned the need to move beyond just describing outcomes towards understanding why they are happening as this information can be helpful to identify interventions. For example, it was suggested that project or program evaluations as well as rigorous analytical approaches (e.g., causal chain analysis) could be employed to understand which factors - related to governance models, management actions, interventions, or the broader social and governance context - are producing different social or ecological outcomes.

Finally, interviewees also discussed how the social sciences might be used to explore curiosity-driven, theoretical, or synthetic research questions related to conservation in working landscapes and seascapes. They explored how “big picture” questions might extend on past research related to any social science theory or topic (e.g., such as those discussed above or highlighted in Table 3 - equity and justice, environmental stewardship, governance, behaviours, human-nature relations, etc.), and through doing so provide more generalizable knowledge and broadly applicable insights that transcend beyond individual initiatives or locations. Some interviewees went further to argue that producing theoretical and generalizable knowledge was the real role of social science, not just to produce site specific insights or provide information that aims to achieve some practical or instrumental outcome for conservation. Those participants trained in the social sciences, in particular, stressed that current conservation social science efforts were often limited in scope and overly mandate driven, rather than being broad, creative and curiosity driven. This, they felt, limited the true potential of conservation social science to produce novel or synthetic insights. Yet even though some interview participants emphasized that there is space for broader research on many social science topics, there were relatively few specific theoretical or synthetic questions that emerged from the interviews. Broader questions did emerge, nonetheless, related to topics such as culture, human well-being, governance, gender, local stewardship, as well as rights and tenure (see Table 3).

To ensure that conservation social science research projects expand beyond a place-based or problem-focused approach, participants suggested that social science on conservation in working landscapes and seascapes should also: 1) employ systematic reviews or meta-analyses of published research or available data; 2) develop insights, lessons learned, or best practices related to specific topics above (e.g., efforts to bridge science-policy-practice, community-based conservation, integrating human well-being, Indigenous approaches, gender) from across multiple sites or case studies; and/or, 3) engage with curiosity-driven, theory-driven, or hypothesis-driven research projects that examine fundamental questions about the human condition, that contribute to social theory, or that provide insights into human-nature relations or the social aspects of conservation.

In this paper, we provide an exploratory analysis of the potential contributions of the social sciences to conservation in working landscapes and seascapes. The contribution of this paper is that it moves beyond previous calls for more conservation social science as an essential input into evidence-informed conservation (Mascia et al., 2003; Bennett et al., 2017b), and the past emphasis on the different disciplines, methods, and theoretical underpinnings of conservation social science (Newing et al., 2011; Moon and Blackman, 2014; Bennett et al., 2017a). Instead, this paper identifies a suite of specific human dimensions topics and questions that might be the focus of research on and for conservation in working landscapes and seascapes. In particular, the research highlights 38 distinct topics and related questions that could be the focus of conservation social science across the planning, doing and learning phases of conservation decision-making and adaptive management in integrated landscape and seascape initiatives.

We note that many of the specific topics and questions identified here are not particularly novel from a theoretical standpoint, often having been already explored in publications in the broader conservation social science literature. Yet, novel research or theoretical contributions in the conservation social sciences may not produce the place-based knowledge and actionable insights that is required by practitioners, managers, and policy-makers to make evidence-informed conservation decisions (Beier et al., 2017; Niemiec et al., 2021). Basic information related to the many human dimensions topics and questions presented in Table 3 is required to inform actions during the different stages - planning, doing and learning - of conservation in working landscapes and seascapes. This research does, however, make a novel contribution by highlighting that there is a much broader set of potential social science topics than are often prioritized at each stage in conservation. For example, conservation planning processes often incorporate social considerations that can be easily spatialized, such as land/sea uses, social and economic values, as well as rights and tenure (Ban et al., 2013; Cornu et al., 2014; Mangubhai et al., 2015), but not the broader set of social considerations (e.g., gender, traditional knowledge, local stewardship practices) that emerged from this research. Similarly, social impacts and human well-being have seemingly become the primary focus of social monitoring and evaluation efforts at the learning stage of conservation (Schreckenberg et al., 2010; Milner-Gulland et al., 2014; de Lange et al., 2016; Schleicher, 2018; Ban et al., 2019). Thus, this paper adds to the literature by showing that the potential contributions of place-based and problem-focused social sciences to conservation policy and practice are much more expansive than is often the focus of government agencies and conservation organizations.

At the same time, these results emphasize how social science research on conservation in working landscapes and seascapes can make synthetic or theoretical contributions. Such approaches to research can produce generalizable knowledge or novel insights that could change the way that we think about conservation or guide the (re)design of overarching conservation approaches, policies or programs (Sandbrook et al., 2013; Bennett and Roth, 2019; Wyborn et al., 2020). Previous examples of high impact theoretical research include studies into the factors that enable successful common pool resource management (Ostrom, 1990; Agrawal, 2001; Cox et al., 2010) or biocultural approaches to conservation (Pilgrim and Pretty, 2010; Sterling et al., 2017). Yet, as noted above, there were fewer specific “big picture” questions that emerged from the interviews. Perhaps this is because the questions we asked were oriented towards the site level or because deep engagement with existing social science literature related to a topic is required to identify gaps in knowledge or theory and relatively few of our sample were trained in the social sciences. This is another potential reason why the research questions related to many of the social science topics were not as novel. Regardless, there is ample scope to further develop curiosity-driven, theory-driven and synthetic social science research questions and projects related to conservation in working landscapes and seascapes.

While the results presented here stemmed from research focused specifically on conservation in working landscapes and seascapes (in particular, 14 sites within the Smithsonian Working Land and Seascapes Initiative), we recognize that many of the topics and questions that emerged from the exploratory interviews are also pertinent and applicable to other types of conservation problems (e.g., species or habitat conservation, protected areas management, ecosystem-based management) in other locations. What then is unique about the identified social science needs for conservation in working landscapes and seascapes? As discussed in the introduction, integrated conservation initiatives work to achieve beneficial outcomes for nature and people in landscapes and seascapes that are a mosaic of ecosystems, communities, users, infrastructures, human activities, conservation actions, and governance jurisdictions (Kremen and Merenlender, 2018; Deichmann et al., 2019; Murphy et al., 2021). As working landscapes and seascapes are viewed as a key operational unit for the integrated management of human activities and nature, the potential social science questions that identified here tend to focus at a larger scale than site-based research and often seek to understand the multiplicity of users, sectors, human activities, conservation actions and jurisdictions within the scape. For example, there is a significant emphasis in the proposed questions on understanding the demographics, values, perspectives, livelihoods, resource use, and behaviors of different communities and user groups across the landscape or seascape. Many of the proposed conservation social science questions are also related to central aims or defining characteristics of landscape or seascape conservation initiatives (Carmenta et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2021; Reed et al., 2020a and 2020b; Sayer et al., 2013). There was a strong emphasis, for instance, on the need for a greater understanding of whether and how conservation actions and sustainable use of biodiversity supports human well-being, which is a key target of integrated conservation (Reed et al., 2016; Annis et al., 2017; Carmenta et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2021). Similarly, inclusive decision-making and coordination of governance across jurisdictions are defining characteristics of conservation at this scale (Sayer et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2021), and many research questions emerged related to both the quality and functioning of governance within landscapes and seascapes. Finally, the suggested research questions highlight the need to assess local social networks and approaches to conservation, which is important as grassroots movements and bottom-up initiatives are increasingly seen as critical to successful conservation and management actions in working landscapes and seascapes.

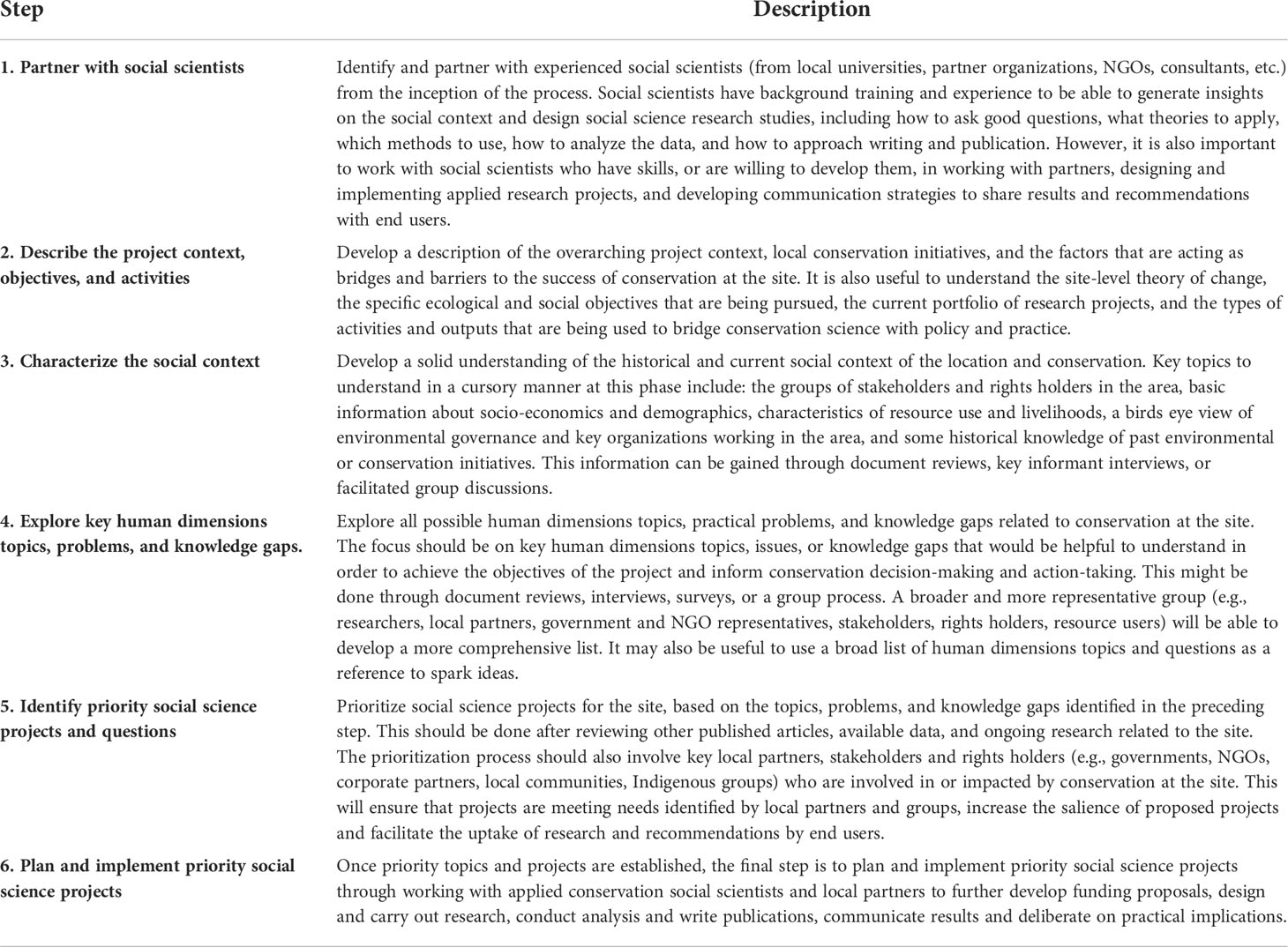

This research emphasizes how an understanding of local people and social processes is key to making evidence-informed decisions in the conservation of working landscapes and seascapes. Thus, we recommend that conservation social science be mainstreamed in these initiatives by organizations working in this space. This requires strategic planning to develop social science research programs, building organizational capacity in the social sciences, and effectively bridging insights from the science with policy and practice. First, we are not aware of any integrated conservation initiatives or organizations that have developed and implemented a coherent and comprehensive program of social science research. We suggest that there is a need for these initiatives and organizations to move beyond “one-off” social science projects. For those organizations and initiatives wishing to develop a conservation social science research agenda that builds on existing social science that is being conducted, we provide a general set of steps that might be used to identify, prioritize and plan social science projects for a particular landscape or seascape initiative or context (Table 4). We encourage the co-development of research agendas with local partners, stakeholders, and rights holders to ensure that it meets local needs (Naugle et al., 2020; Norström et al., 2020; Chambers et al., 2021). While the priority for many organizations may be place-based and problem-focused research that produces actionable knowledge, opportunities to develop generalizable knowledge and scalable insights should also be explored. Key considerations when designing the social science research program, to ensure that it truly focuses on conservation of the landscape or seascape, include bridging across scales (e.g., from individual projects to the scape), incorporating multiple systems (e.g., forests, freshwater, agriculture), and considering multiple groups and sectors (e.g., NGOs, farmers, landowners, hunters, foresters, industry).

Table 4 Steps to identify, prioritize, and develop social science research projects for a working landscape or seascape project.

Second, we recommend that conservation agencies and organizations working on conservation in working landscapes and seascapes build their internal capacity to conduct social science - through hiring trained and experienced social scientists to help develop the program of research, design and carry out research projects, and analyze and publish the results (Bennett et al., 2017b). Engaging with experienced and trained social scientists will help to ensure that the research agenda and individual research projects are rigorously designed, are grounded in the relevant theory, and make a novel contribution to the literature (Bennett et al., 2017b; Dayer et al., 2020). Donors and funding agencies thus need to support the expansion of programs and budgets to include social scientists and social science research. We note that tackling a social science research agenda for adaptive management in a working landscape or seascape will require more than a single social scientist. Interdisciplinary conservation science programs should include a balance of natural and social scientists, including a team or network of social scientists with complementary training in different disciplines, theories, and methods.

Third, there is a need to ensure that there are clear mechanisms and processes for bridging or embedding the insights from social science into policy and practice for conservation in working landscapes and seascapes (Lubchenco, 1998; Nguyen et al., 2017; Posner and Cvitanovic, 2019). As we have highlighted throughout this paper, this integration of social science needs to occur during all stages - planning, doing, and learning - of conservation planning and adaptive management (Armitage et al., 2010; Jacobson et al., 2014; Redford et al., 2018). Human dimensions information needs to also be merged with insights from the natural sciences in order to achieve the holistic aspirations and dual social-ecological objectives of these initiatives. The development of intentional partnerships of researchers, practitioners, policy-makers and stakeholders to co-produce research projects and outputs may be particularly helpful in producing usable knowledge that can guide decisions in working landscapes and seascapes (Naugle et al., 2020; Norström et al., 2020; Chambers et al., 2021). Yet, we also recognize that it may not be a matter of simply integrating social science insights into pre-existing conservation frameworks; instead research on some of these topics (e.g., culture, gender, traditional knowledge, Indigenous approaches) may be quite disruptive to conventional thinking and require innovation. For example, research into Indigenous culture, visions and practices, or approaches to conservation may reveal insights that will necessitate a re-imagining, re-thinking, or decolonizing of conservation models and practices (Araos et al., 2020; Leonard et al., 2020; Rayne et al., 2020).

Finally, we recognize that this study has some limitations. While the list of 38 topics and questions contained herein is quite comprehensive, it surely does not cover all possible topics and questions that could be asked in other working landscapes and seascapes around the world. It draws insights from only 14 sites in a limited number of geographies, and our interview sample (n=30) was relatively small. The sample of key informants could have also included more representatives from many groups - such as local stakeholders or government representatives. As a result, this study may have missed some topics and we were also unable to explore each topic in depth. Furthermore, a different researcher or team may have coded the topics differently and/or found more or less topics in the same qualitative data. Our approach of generalizing from the data also means that we have inevitably lost finer scale resolution in how the topics and questions were framed and might be applied at each site. Thus, we recommend that the list of topics and questions be viewed as a foundational reference – and urge caution as not all topics and questions will be applicable to all sites, or may not be framed in a way that is sensitive to the local context. Future research should build on this foundation through systematically reviewing past social science research on or for integrated landscape and seascape initiatives and identifying additional topics as well as place-based, problem-focused, synthetic or theoretical research questions that might help to improve current practice or lead to innovations. In spite of these limitations, this paper expands upon the previous literature in several important ways outlined above.

Integrated landscape and seascape approaches to conservation, which are a vital tool for achieving global goals for biodiversity and development, focus on holistic management and sustainable use of natural resources in order to maintain and/or restore biodiversity and ecosystem services as the foundation of livelihoods and human well-being. Insights from the social sciences are essential to address the social and governance complexities of working with multiple stakeholders and rights holders, interests, and institutions at the scale of landscapes or seascapes. This paper examines the specific topics that might be examined to inform these initiatives across the planning, doing, and learning stages of conservation decision-making and adaptive management. It also emphasizes how conservation social science can be place-based/problem-focused and/or synthetic/theoretical in orientation. We contend that using social science to understand different aspects of the social, economic, cultural, and governance context can help to ensure that conservation approaches, plans and management actions are more effective, socially equitable, and robust. Thus, we call on governments, non-governmental organizations, funding agencies, research funders, and private sector actors engaged with integrated conservation initiatives in working landscapes and seascapes to work with and support social scientists. Mainstreaming of insights from the social sciences into conservation in working landscapes and seascapes requires re-peopling our conservation imagination, developing conservation social science research programs, establishing interdisciplinary teams that include social scientists, and creating processes to integrate insights.

The qualitative interview data associated with this study is not publicly available to maintain anonymity and confidentiality of research participants. The interview protocol and questions are included in the Supplementary Material.

This study involved human participants and was reviewed and approved by Smithsonian Institution Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (Protocol # HS21008). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

NB: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and writing - original draft. MD: funding acquisition, project administration, conceptualization, methodology - review, and writing - review & editing. TA: conceptualization and writing - review & editing. SC: conceptualization, methodology - review, and writing - review & editing. RC: writing - review & editing. AD: writing - review & editing. JD: conceptualization, methodology - review, and writing - review & editing. DG: writing - review & editing. MM: writing - review & editing. JM: writing - review & editing. SM: writing - review & editing. AN: writing - review & editing. MS: conceptualization, methodology - review, and writing - review & editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Working Land and Seascapes Initiative, Smithsonian Institution.

We are grateful to all of the interview participants. The illustration of working landscapes and seascapes (Figure 1) was designed by Max Jake Palomino (https://www.instagram.com/jakeilus/). The map (Figure 2) was created by Craig Fergus. Figure 3 was created by Sarah Wheedleton. This is Smithsonian Marine Station contribution number 1182.

NB was hired as a freelance consultant by the Smithsonian Institution to carry out this project. JM is employed by Conservation Research Consultants Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2022.954930/full#supplementary-material

Adams W. M., Sandbrook C. (2013). Conservation, evidence and policy. Oryx 47, 329–335. doi: 10.1017/S0030605312001470

Agrawal A. (2001). Common property institutions and sustainable governance of resources. World Dev. 29, 1649–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00063-8

Allen CR, Garmestani AS (2015). Adaptive management of social-ecological systems (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands) (Accessed December 11, 2015).

Almond REA, Grooten M, Petersen T(2020). Living planet report 2020: Bending the curve of biodiversity loss (Gland, Switzerland: WWF). Available at: http://www.deslibris.ca/ID/10104983 (Accessed 28, 2021).

Annis G. M., Pearsall D. R., Kahl K. J., Washburn E. L., May C. A., Taylor R. F., et al. (2017). Designing coastal conservation to deliver ecosystem and human well-being benefits. PloS One 12, e0172458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172458

Araos F., Anbleyth-Evans J., Riquelme W., Hidalgo C., Brañas F., Catalán E., et al. (2020). Marine indigenous areas: Conservation assemblages for sustainability in southern Chile. Coast. Manage. 48, 289–307. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2020.1773212

Armitage D., Berkes F., Doubleday N. (2010). Adaptive Co-management: Collaboration, learning, and multi-level governance (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press).

Ban N. C., Cinner J. E., Adams V. M., Mills M., Almany G. R., Ban S. S., et al. (2012). Recasting shortfalls of marine protected areas as opportunities through adaptive management. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 22, 262–271. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2224

Ban N. C., Gurney G. G., Marshall N. A., Whitney C. K., Mills M., Gelcich S., et al. (2019). Well-being outcomes of marine protected areas. Nat. Sustain. 2, 524. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0306-2

Ban N. C., Mills M., Tam J., Hicks C. C., Klain S., Stoeckl N., et al. (2013). A social–ecological approach to conservation planning: embedding social considerations. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 194–202. doi: 10.1890/110205

Beier P., Hansen L. J., Helbrecht L., Behar D. (2017). A how-to guide for coproduction of actionable science. Conserv. Lett. 10, 288–296. doi: 10.1111/conl.12300

Benaquisto L. (2008)Open coding. In: The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications). Available at: http://knowledge.sagepub.com/view/research/n299.xml (Accessed May 1, 2013).

Bennett N. J. (2019). Marine social science for the peopled seas. Coast. Manage. 47, 244–252. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2019.1564958

Bennett N. J., Roth R. (2019). Realizing the transformative potential of conservation through the social sciences, arts and humanities. Biol. Conserv. 229, A6–A8. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.07.023

Bennett N. J., Roth R., Klain S. C., Chan K. M. A., Christie P., Clark D. A., et al. (2017a). Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol. Conserv. 205, 93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.006

Bennett N. J., Roth R., Klain S. C., Chan K. M. A., Clark D. A., Cullman G., et al. (2017b). Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conserv. Biol. 31, 56–66. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12788

Bensted-Smith R., Kirkman H. (2010). Comparison of approaches to management of Large marine areas (Cambridge, UK: Fauna & Flora International).

Bixler R. P., Johnson S., Emerson K., Nabatchi T., Reuling M., Curtin C., et al. (2016). Networks and landscapes: a framework for setting goals and evaluating performance at the large landscape scale. Front. Ecol. Environ. 14, 145–153. doi: 10.1002/fee.1250

Boucquey N. (2020). The “nature” of fisheries governance: narratives of environment, politics, and power and their implications for changing seascapes. J. Polit. Ecol. 27, 169–189. doi: 10.2458/v26i1.23248

Brockington D., Adams W. M., Agarwal B., Agrawal A., Büscher B., Chhatre A., et al. (2018). Working governance for working land. Science 362, 1257–1257. doi: 10.1126/science.aav8452

Brown G., Hausner V. H. (2017). An empirical analysis of cultural ecosystem values in coastal landscapes. Ocean Coast. Manage. 142, 49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.03.019

Bruskotter J. T., Shelby L. B. (2010). Human dimensions of Large carnivore conservation and management: Introduction to the special issue. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 15, 311–314. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2010.508068

Canty S. W. J., Nowakowski A. J., Connette G. M., Deichmann J. L., Songer M., Chiaravalloti R., et al. (2022). Mapping a conservation research network to the sustainable development goals. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 4, e12731. doi: 10.1111/csp2.12731

Carmenta R., Coomes D. A., DeClerck F. A. J., Hart A. K., Harvey C. A., Milder J., et al. (2020). Characterizing and evaluating integrated landscape initiatives. One Earth 2, 174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.01.009

Chambers J. M., Wyborn C., Ryan M. E., Reid R. S., Riechers M., Serban A., et al. (2021). Six modes of co-production for sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 4, 983–996. doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00755-x

Charles A., Wilson L. (2009). Human dimensions of marine protected areas. ICES J. Mar. Sci. J. Cons. 66, 6–15. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsn182

Chiaravalloti R. M., Homewood K., Dyble M. (2021). Sustainability of social–ecological systems: The difference between social rules and management rules. Conserv. Lett. 14, e12826. doi: 10.1111/conl.12826

Christie P., Bennett N. J., Gray N. J., ‘Aulani Wilhelm T., Lewis N., Parks J., et al. (2017). Why people matter in ocean governance: Incorporating human dimensions into large-scale marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 84, 273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.08.002

Cohen P. J., Evans L. S., Mills M. (2012). Social networks supporting governance of coastal ecosystems in Solomon islands. Conserv. Lett. 5, 376–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00255.x

Cornu E. L., Kittinger J. N., Koehn J. Z., Finkbeiner E. M., Crowder L. B. (2014). Current practice and future prospects for social data in coastal and ocean planning. Conserv. Biol. 28, 902–911. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12310

Cox M., Arnold G., Tomás S. V. (2010). A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecol. Soc 15, 38. doi: 10.5751/ES-03704-150438

Cuerrier A., Turner N. J., Gomes T. C., Garibaldi A., Downing A. (2015). Cultural keystone places: Conservation and restoration in cultural landscapes. J. Ethnobiol. 35, 427–448. doi: 10.2993/0278-0771-35.3.427

Dayer A. A., Silva-Rodríguez E. A., Albert S., Chapman M., Zukowski B., Ibarra J. T., et al. (2020). Applying conservation social science to study the human dimensions of Neotropical bird conservation. Condor 122, 1–15. doi: 10.1093/condor/duaa021

Decker D. J., Riley S. J., Siemer W. F. (2012). Human dimensions of wildlife management. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

Deichmann J. L., Canty S. W. J., Akre T. S. B., McField M. (2019). Broadly defining “working lands.” Science 363, 1046–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw3007

de Lange E., Woodhouse E., Milner-Gulland E. J. (2016). Approaches used to evaluate the social impacts of protected areas. Conserv. Lett. 9, 327–333. doi: 10.1111/conl.12223

den Uyl R. M., Driessen P. P. J. (2015). Evaluating governance for sustainable development – insights from experiences in the Dutch fen landscape. J. Environ. Manage. 163, 186–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.08.022

Díaz S., Settele J., Brondízio E. S., Ngo H. T., Agard J., Arneth A., et al. (2019). Pervasive human-driven decline of life on earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 366, eaax3100. doi: 10.1126/science.aax3100

Drury R., Homewood K., Randall S. (2011). Less is more: the potential of qualitative approaches in conservation research. Anim. Conserv. 14, 18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00375.x

Dunham J. B., Angermeier P. L., Crausbay S. D., Cravens A. E., Gosnell H., McEvoy J., et al. (2018). Rivers are social–ecological systems: Time to integrate human dimensions into riverscape ecology and management. WIREs Water 5, e1291. doi: 10.1002/wat2.1291

Egan D., Hjerpe E. E., Abrams J. (2012). Human dimensions of ecological restoration: Integrating science, nature, and culture. Washington, DC: Island Press.

ESSA. (2022). The Adaptive Management Mindset to manage social ecological systems. ESSA. Available at: https://essa.com/approach/ [Accessed August 12, 2022].

Guerrero A. M., Wilson K. A. (2016). Using a social-ecological framework to inform the implementation of conservation plans. Conserv. Biol. 31, 290–301. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12832

Gurney G. G., Darling E. S., Ahmadia G. N., Agostini V. N., Ban N. C., Blythe J., et al. (2021). Biodiversity needs every tool in the box: use OECMs. Nature 595, 646–649. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02041-4

Hall D. M., Martins D. J. (2020). Human dimensions of insect pollinator conservation. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 38, 107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2020.04.001

Halpern B. S., Walbridge S., Selkoe K. A., Kappel C. V., Micheli F., D’Agrosa C., et al. (2008). A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 319, 948–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1149345

Head L. (2017). The social dimensions of invasive plants. Nat. Plants 3, 17075. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.75

Hockings M., Stolton S., Leverington F., Dudley N., Courrau J. (2006). Evaluating effectiveness: A framework for assessing the management effectiveness of protected areas. 2nd edition (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN).

Holling C. S. (1977). Adaptive environmental assessment and management. Vancouver, BC: Institute of Resource Ecology, University of British Columbia.

Imperial M. T., Ospina S., Johnston E., O’Leary R., Thomsen J., Williams P., et al. (2016). Understanding leadership in a world of shared problems: advancing network governance in large landscape conservation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 14, 126–134. doi: 10.1002/fee.1248

IPBES (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services (Bonn, Germany: Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services). Available at: https://www.ipbes.net/system/tdf/spm_global_unedited_advance.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=35245.

IPCC (2014). Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability (New York, NY: International Panel on Climate Change, United Nations Environment Program).

Jacobson C., Carter R. W., Thomsen D. C., Smith T. F. (2014). Monitoring and evaluation for adaptive coastal management. Ocean Coast. Manage. 89, 51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.12.008

Jonas H. D., Barbuto V., Jonas H. C., Kothari A., Nelson F. (2014). New steps of change: Looking beyond protected areas to consider other effective area-based conservation measures. Parks 20, 111–128. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2014.PARKS-20-2.HDJ.en

Jones K. R., Klein C. J., Halpern B. S., Venter O., Grantham H., Kuempel C. D., et al. (2018). The location and protection status of earth’s diminishing marine wilderness. Curr. Biol. 28, 2506–2512. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.010

Kallio H., Pietilä A.-M., Johnson M., Kangasniemi M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031

Kavanaugh M. T., Oliver M. J., Chavez F. P., Letelier R. M., Muller-Karger F. E., Doney S. C. (2016). Seascapes as a new vernacular for pelagic ocean monitoring, management and conservation. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, 1839–1850. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsw086

Knight A. T., Cowling R. M., Difford M., Campbell B. M. (2010). Mapping human and social dimensions of conservation opportunity for the scheduling of conservation action on private land. Conserv. Biol. 24, 1348–1358. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01494.x

Kremen C., Merenlender A. M. (2018). Landscapes that work for biodiversity and people. Science 362, eaau6020. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6020

Legge S. (2015). A plea for inserting evidence-based management into conservation practice. Anim. Conserv. 18, 113–116. doi: 10.1111/acv.12195

Leonard K., Aldern J. D., Christianson A., Ranco D., Thornbrugh C., Loring P. A., et al. (2020). Indigenous conservation practices are not a monolith: Western cultural biases and a lack of engagement with indigenous experts undermine studies of land stewardship. EcoEvoRxiv, Online. doi: 10.32942/osf.io/jmvqy

Levin P. S., Breslow S. J., Harvey C. J., Norman K. C., Poe M. R., Williams G. D., et al. (2016). Conceptualization of social-ecological systems of the California current: An examination of interdisciplinary science supporting ecosystem-based management. Coast. Manage. 44, 397–408. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2016.1208036

Locke H., Ellis E. C., Venter O., Schuster R., Ma K., Shen X., et al. (2019). Three global conditions for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use: an implementation framework. Natl. Sci. Rev. 6, 1080–1082. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwz136

Lubchenco J. (1998)Entering the century of the environment: A new social contract for science (Accessed September 17, 2021).

Mangubhai S., Erdmann M. V., Wilson J. R., Huffard C. L., Ballamu F., Hidayat N. I., et al. (2012). Papuan bird’s head seascape: Emerging threats and challenges in the global center of marine biodiversity. Mar. pollut. Bull. 64, 2279–2295. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.07.024

Mangubhai S., Wilson J. R., Rumetna L., Maturbongs Y., Purwanto (2015). Explicitly incorporating socioeconomic criteria and data into marine protected area zoning. Ocean Coast. Manage. 116, 523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.08.018

Mascia M. B., Brosius J. P., Dobson T. A., Forbes B. C., Horowitz L., McKean M. A., et al. (2003). Conservation and the social sciences. Conserv. Biol. 17, 649–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01738.x

McCauley D. J., Pinsky M. L., Palumbi S. R., Estes J. A., Joyce F. H., Warner R. R. (2015). Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Science 347, 1255641. doi: 10.1126/science.1255641

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Our human planet: Summary for decision makers (Washington, D.C: Island Press).

Milner-Gulland E. J., Mcgregor J. A., Agarwala M., Atkinson G., Bevan P., Clements T., et al. (2014). Accounting for the impact of conservation on human well-being. Conserv. Biol. 28, 1160–1166. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12277

Moon K., Blackman D. (2014). A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conserv. Biol. 28, 1167–1177. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12326

Murphy S. E., Farmer G., Katz L., Troëng S., Henderson S., Erdmann M. V., et al. (2021). Fifteen years of lessons from the seascape approach: A framework for improving ocean management at scale. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 3, e423. doi: 10.1111/csp2.423

Nagendra H., Ostrom E. (2012). Polycentric governance of multifunctional forested landscapes. Int. J. Commons 6, 104–133. doi: 10.18352/ijc.321

Naugle D. E., Allred B. W., Jones M. O., Twidwell D., Maestas J. D. (2020). Coproducing science to inform working lands: The next frontier in nature conservation. BioScience 70, 90–96. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biz144

Newing H., Eagle C. M., Puri R., Watson C. W. (2011). Conducting research in conservation: social science methods and practice (London, New York: Routledge).

Nguyen V. M., Young N., Cooke S. J. (2017). A roadmap for knowledge exchange and mobilization research in conservation and natural resource management. Conserv. Biol. 31, 789–798. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12857

Niemiec R. M., Gruby R., Quartuch M., Cavaliere C. T., Teel T. L., Crooks K., et al. (2021). Integrating social science into conservation planning. Biol. Conserv. 262, 109298. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109298

Norström A. V., Cvitanovic C., Löf M. F., West S., Wyborn C., Balvanera P., et al. (2020). Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat. Sustain. 3, 182–190. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2

Ostrom E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action (Oxford, UK: Cambridge University Press).

Pilgrim S., Pretty J. N. (2010). Nature and culture: Rebuilding lost connections (London, UK: Earthscan).

Pimm S. L., Jenkins C. N., Li B. V. (2018). How to protect half of earth to ensure it protects sufficient biodiversity. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat2616. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat2616

Poe M. R., Norman K. C., Levin P. S. (2014). Cultural dimensions of socioecological systems: Key connections and guiding principles for conservation in coastal environments: Cultural dimensions of coastal conservation. Conserv. Lett. 7, 166–175. doi: 10.1111/conl.12068

Posner S. M., Cvitanovic C. (2019). Evaluating the impacts of boundary-spanning activities at the interface of environmental science and policy: A review of progress and future research needs. Environ. Sci. Policy 92, 141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.11.006

Prokopy L. S., Floress K., Arbuckle J. G., Church S. P., Eanes F. R., Gao Y., et al. (2019). Adoption of agricultural conservation practices in the united states: Evidence from 35 years of quantitative literature. J. Soil Water Conserv. 74, 520–534. doi: 10.2489/jswc.74.5.520

Rayne A., Byrnes G., Collier-Robinson L., Hollows J., McIntosh A., Ramsden M., et al. (2020). Centring indigenous knowledge systems to re-imagine conservation translocations. People Nat. 2, 512–526. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10126

Redford K. H., Hulvey K. B., Williamson M. A., Schwartz M. W. (2018). Assessment of the conservation measures partnership’s effort to improve conservation outcomes through adaptive management. Conserv. Biol. 32, 926–937. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13077

Reed J., Ickowitz A., Chervier C., Djoudi H., Moombe K., Ros-Tonen M., et al. (2020a). Integrated landscape approaches in the tropics: A brief stock-take. Land Use Policy 99, 104822. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104822

Reed J., Ros-Tonen M. A. F., Sunderland T. C. H. (2020b). Operationalizing integrated landscape approaches in the tropics (Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR).

Reed J., Vianen J. V., Deakin E. L., Barlow J., Sunderland T. (2016). Integrated landscape approaches to managing social and environmental issues in the tropics: learning from the past to guide the future. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 2540–2554. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13284

Riggio J., Baillie J. E. M., Brumby S., Ellis E., Kennedy C. M., Oakleaf J. R., et al. (2020). Global human influence maps reveal clear opportunities in conserving earth’s remaining intact terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 4344–4356. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15109

Sandbrook C., Adams W. M., Büscher B., Vira B. (2013). Social research and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 27, 1487–1490. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12141

Sayer J., Sunderland T., Ghazoul J., Pfund J.-L., Sheil D., Meijaard E., et al. (2013). Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 8349–8356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210595110

Schleicher J. (2018). The environmental and social impacts of protected areas and conservation concessions in south America. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 32, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.01.001

Schreckenberg K., Camargo I., Withnall K., Corrigan C., Franks P., Roe D., et al. (2010). Social assessment of conservation initiatives: A review of rapid methodologies (London: IIED).

Sloan N. A. (2002). History and application of the wilderness concept in marine conservation. Conserv. Biol. 16, 294–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00071.x

Stanturf J., Lamb D., Madsen P. (2012). Forest landscape restoration: Integrating natural and social sciences (London, UK: Springer).

Sterling E. J., Filardi C., Toomey A., Sigouin A., Betley E., Gazit N., et al. (2017). Biocultural approaches to well-being and sustainability indicators across scales. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1798–1806. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0349-6

Strauss A. L. (1987) Qualitative analysis for social scientists (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Available at: http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ref/id/CBO9780511557842 (Accessed May 1, 2013).

Sutherland W. J., Pullin A. S., Dolman P. M., Knight T. M. (2004). The need for evidence-based conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 305–308. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.018

Tanzer J., Phua C., Jeffries B., Lawrence A., Gonzales A., Gamblin P., et al. (2015). Living blue planet report species, habitats and human well-being (Gland, Switz: WWF International). Available at: http://ocean.panda.org/media/Living_Blue_Planet_Report_2015_Final_LR.pdf (Accessed September 30, 2015).

Tittensor D. P., Mora C., Jetz W., Lotze H. K., Ricard D., Berghe E. V., et al. (2010). Global patterns and predictors of marine biodiversity across taxa. Nature 466, 1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/nature09329

United Nations (2015) Sustainable development goals (New York, NY: United Nations). Available at: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (Accessed August 14, 2017).

Uychiaoco A. J., Arceo H. O., Green S. J., Cruz M. T., Gaite P. A., Aliño P. M. (2005). Monitoring and evaluation of reef protected areas by local fishers in the Philippines: Tightening the adaptive management cycle. Biodivers. Conserv. 14, 2775–2794. doi: 10.1007/s10531-005-8414-x

Williams B. K. (2011). Adaptive management of natural resources–framework and issues. J. Environ. Manage. 92, 1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.10.041

Wilson E. O. (2016). Half-earth: Our planet’s fight for life. (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company).

Wyborn C., Davila F., Pereira L., Lim M., Alvarez I., Henderson G., et al. (2020). Imagining transformative biodiversity futures. Nat. Sustain. 3, 670–672. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0587-5

Zhao Q., Stephenson F., Lundquist C., Kaschner K., Jayathilake D., Costello M. J. (2020). Where marine protected areas would best represent 30% of ocean biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 244, 108536. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108536

Keywords: conservation social science, integrated conservation, seascapes, landscapes, human dimensions, social-ecological systems, marine social science, biodiversity conservation

Citation: Bennett NJ, Dodge M, Akre TS, Canty SWJ, Chiaravalloti R, Dayer AA, Deichmann JL, Gill D, McField M, McNamara J, Murphy SE, Nowakowski AJ and Songer M (2022) Social science for conservation in working landscapes and seascapes. Front. Conserv. Sci. 3:954930. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2022.954930

Received: 27 May 2022; Accepted: 01 August 2022;

Published: 23 August 2022.

Edited by:

Claudia Capitani, Joint Research Centre, ItalyReviewed by:

Felix L. M. Ming’Ate, Kenyatta University, KenyaCopyright © 2022 Bennett, Dodge, Akre, Canty, Chiaravalloti, Dayer, Deichmann, Gill, McField, McNamara, Murphy, Nowakowski and Songer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nathan J. Bennett, bmF0aGFuLmouYmVubmV0dC4xQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.