- 1School of Animal, Rural and Environmental Sciences, Nottingham Trent University, Southwell, United Kingdom

- 2Research Centre for Agroecology, Water & Resilience, Coventry University, West Midlands, United Kingdom

Human-carnivore coexistence (HCC) on agricultural lands affects wildlife and human communities around the world, whereby a lack of HCC is a central concern for conservation and farmer livelihoods alike. For intervention strategies aimed at facilitating HCC to achieve their desired goals it is essential to understand how interventions and their success are perceived by different stakeholders. Using a grounded theory approach, interviews (n=31) were conducted with key stakeholders (commercial livestock farmers, conservationists and protected area managers) involved in HCC scenarios in Limpopo, South Africa. Interviews explored perceptions of successful intervention strategies (aimed at increasing HCC), factors that contribute to perceptions of strategy effectiveness and whether coexistence was a concept that stakeholders considered achievable. The use of grounded theory emphasised the individual nature and previously unexplored facets to HCC experiences. The majority of stakeholders based their measures of success on changes in livestock loss. Concern has been raised over the subjectivity and reliance on recall that this measure involves, potentially reducing its reliability as an indicator of functional effectiveness. However, it was relied on heavily by users of HCC interventions in our study and is therefore likely influential in subsequent behaviour and decision-making regarding the intervention. Nonetheless, perceptions of success were not just shaped by livestock loss but influenced by various social, cultural, economic and political factors emphasising the challenges of defining and achieving HCC goals. Perceptions of coexistence varied; some stakeholders considered farmer-carnivore coexistence to be impossible, but most indicated it was feasible with certain caveats. An important element of inter-stakeholder misunderstanding became apparent, especially regarding the respective perceptions of coexistence and responsibility for its achievement. Without fully understanding these perceptions and their underpinning factors, interventions may be restricted in their capacity to meet the expectations of all interested parties. The study highlights the need to understand and explore the perceptions of all stakeholders when implementing intervention strategies in order to properly define and evaluate the achievement of HCC goals.

1 Introduction

Coexistence between people and wildlife has become an increasingly important component to many conservation efforts, and yet it is a concept without a universally standardized definition (IUCN SSC HWCTF, 2022). The complexity and highly contextualized nature of coexistence suggests that it may be best viewed as a suite of notions relating to the sharing of landscapes with wildlife, rather than a single, definable construct (IUCN SSC HWCTF, 2022). With this nuanced designation in mind, increasing the means for carnivores and human communities to share natural resources in a sustainable fashion is considered critical to the survival of many large carnivore species and vital for human livelihoods and global food security (Ripple et al., 2014; Boronyak et al., 2020). International interest in increasing coexistence (in its various forms and interpretations) with carnivores in agricultural areas has led to the development of numerous techniques designed to reduce livestock depredation (Miller et al., 2016) but understanding the effectiveness of interventions intended to facilitate so-called human-carnivore coexistence (HCC), is of worldwide concern. If effective, interventions should lead to a reduction in livestock depredation and encourage species conservation thereby benefiting both humans and wildlife (Hazzah et al., 2014; Lichtenfeld et al., 2015). However, studies show that the implementation of an HCC intervention does not guarantee ecological success nor benefit to humans (Bennett et al., 2016). Despite research into different strategies designed to increase HCC, there have been limited attempts to document their success on a global scale and published information about evidence-based effectiveness of interventions against carnivores is limited (Eklund et al., 2017; van Eeden et al., 2018b; Khorozyan and Waltert, 2019; Khorozyan and Waltert, 2021).

Interventions are primarily designed to reduce livestock loss, presuming that a reduction in loss will facilitate coexistence. Subsequently, studies of HCC intervention effectiveness tend to involve quantitative measurements of livestock loss before and after strategy implementation (Miller et al., 2016; Eklund et al., 2017; van Eeden et al., 2018b), thereby focusing on the biological aspects of conflict reduction. Yet, the actual outcomes of HCC scenarios are shaped by diverse social elements (Naha et al., 2014). Likewise, the long-term success of these initiatives relies on numerous factors including willingness to adopt intervention strategies and human behavior changes (Zorondo-Rodríguez et al., 2019). Perceptions of carnivores are not based on livestock loss alone (Marchini and Macdonald, 2018), but perceptions do influence acceptance of mitigation strategies independently of scientific evidence (van Eeden et al., 2018b). It is therefore essential to understand how interventions are perceived by different stakeholders alongside the factors shaping these perceptions.

Since conservation is as much about people as it is about wildlife, understanding or adapting ecological parameters in isolation of the human dimension cannot increase HCC (Bennett et al., 2016). Social science approaches are therefore essential to understand the drivers and impacts of attitudes, tolerance and behavior towards wildlife (Nuno and St John, 2015; Brittain et al., 2020). In particular, grounded theory is an established method that allows concepts, categories and theories to emerge from the data (Glaser, 1978). This allows for in-depth exploration of stakeholder experience to generate theory. The current study adopted a constructivist Charmazian approach to grounded theory, acknowledging that the researcher holds prior knowledge; theory hence arises from reflexive interactions between the researcher, participants, and data (Charmaz, 2006).

The study began with an open-ended question that identified the topic of HCC without making assumptions about it (Corbin and Strauss, 1990). Whilst the use of grounded theory is not limited to a specific discipline (Hussein et al., 2014) and given its ability to reveal in-depth views of participants (Charmaz, 2006) our study joins a surprisingly limited number of previous studies in utilizing it in the context of HCC (Rust, 2015; Margulies and Karanth, 2018; Bogezi et al., 2019). As per practices for grounded theory studies, this paper does not focus on quantitative statistics but explores perceptions of HCC intervention success and the means of measuring it among a range of stakeholders involved in the use of livestock protection strategies in South Africa. Additionally, the factors that contribute to these perceptions and whether coexistence was a concept that stakeholders considered achievable were investigated.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Area

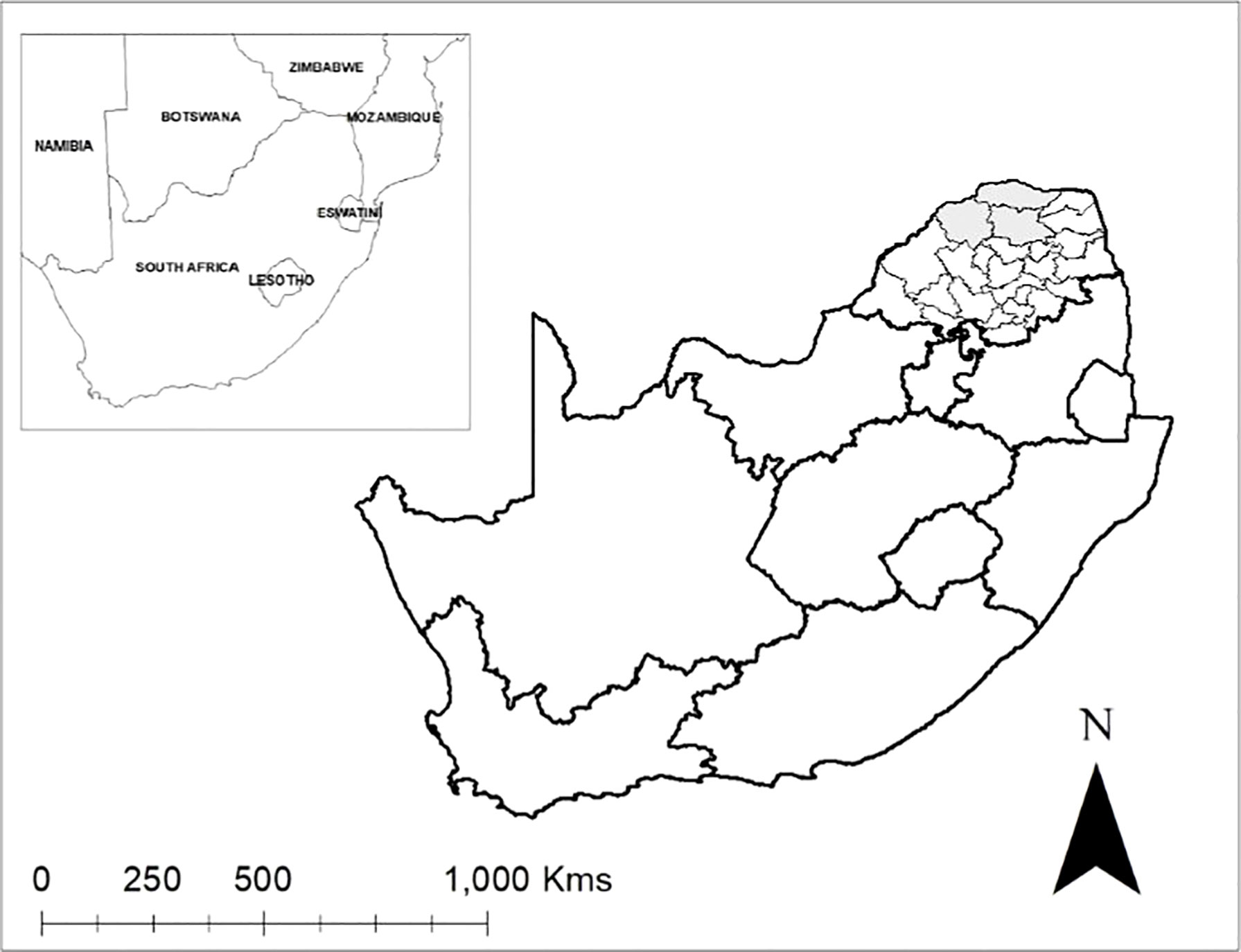

The study was conducted in two districts of the Limpopo Province, South Africa. In the Capricorn district, data collection took place in the Blouberg local municipality, whilst in Vhembe district, data were collected in the Makhado and Musina local municipalities (central coordinates 22°41’10.37”S, 29°11’27.17”E; Figure 1). This region has a semi-arid climate and is prone to frequent drought (mean temperature over the study period was 25.4°C ± 2.9), with the far northern and southern regions of the province being particularly vulnerable to climate change (Anon, 2016). Rainfall occurs mainly during the summer months (October to April), and ranges from 200 millimeters (mm) in the hot dry areas, to 1500 mm in cooler areas (Anon, 2016).

Figure 1 Location of the Blouberg, Makhado and Musina Municipalities (grey) within the Limpopo Province, South Africa, where the data collection occurred. Inset map shows the location of South Africa within Southern Africa.

Limpopo has a dualistic economy comprising both large commercial farms and small subsistence farms (Grwambi et al., 2006). Limpopo’s agricultural output is a major contributor to the national sector and a primary source of employment in the province. Subsistence farming is practiced in all sectors of society within Limpopo whilst commercial farms tend to be run by a small percentage of predominantly white Afrikaans and English-speaking farmers (Blouberg Local Municipality, 2014). Livestock (goats, cattle and sheep) are farmed by >150,000 households in the province (StatsSA, 2016); these farmers experience losses to carnivores and therefore utilize a number of protection measures such as kraals, electric fenced kraals, herders and livestock guardian dogs (LGDs).

The study area falls into the Vhembe biosphere reserve which includes Mapungubwe National Park and Cultural Landscape World Heritage Site, the Makgabeng Plateau and the Blouberg and Soutpansberg mountain ranges (UNESCO MAB Biosphere Reserves Directory, 2016). Formal protected areas cover 11% of Limpopo (Anon, 2016) and the province is known for its rich biodiversity which supports 152 species of mammals (UNESCO MAB Biosphere Reserves Directory, 2016). Free ranging carnivore species move across farmland, including leopard (Panthera pardus), brown hyena (Hyaena brunnea), spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), caracal (Caracal caracal), African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) and black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas) (Findlay, 2016). Game farms, where farmers manage populations of non-domestic ungulate species for hunting or breeding purposes, occur in the study area; however, naturally occurring free-ranging herbivore species also occur.

The study protocol was approved by the Nottingham Trent University School of Animal, Rural and Environmental Sciences Ethical Review Group (ARE880), whereby all participants gave informed consent prior to inclusion in the study and were aware of their right to withdraw.

2.2 Survey Development

Three key informant [i.e. people whose social or professional positions enable them to have specialist knowledge about people, organizations and other aspects relevant to the study] interviews were conducted to provide local insight into the research topic. These informed survey design and the pre-testing of the main interview guide.

2.2.1 Key Informant Interviews

The use of gatekeepers, [i.e. a person or institution that is in a position to establish connections and/or give permission for the research (Newing, 2011)], from the research base and research team contacts in South Africa was employed initially to identify potential participants from each predetermined stakeholder group. Purposive sampling (Newing, 2011) was then used to select participants who had specialist knowledge and/or insights of the subject and area. These became the key informants and were invited to participate in the survey development phase of the study. Key informants were engaged in a conversational interview and a question guide was used to prompt discussions, where needed. Confirmation of eligibility to act as a key informant was determined when the participant demonstrated knowledge of the area and livestock-carnivore interactions. The interview was structured to develop background understanding for the researcher and context for the study. Immediately following the conversational interview, key informants reviewed a draft interview guide to be used for the main study and provided feedback on the questions. The findings from these discussions shaped the content, language and terminology of the main study interview guide.

Key informant interviews were conducted in English by the first author between July-August 2019 at a location convenient to the key informant. Participants agreed to provide their responses in English; an Afrikaans-speaking translator was offered but not utilized. Key informants identified themselves as being from either the farmer (n=1) or NGO stakeholder group (n=2) (Table 1). Key informants were excluded from participating in the main study.

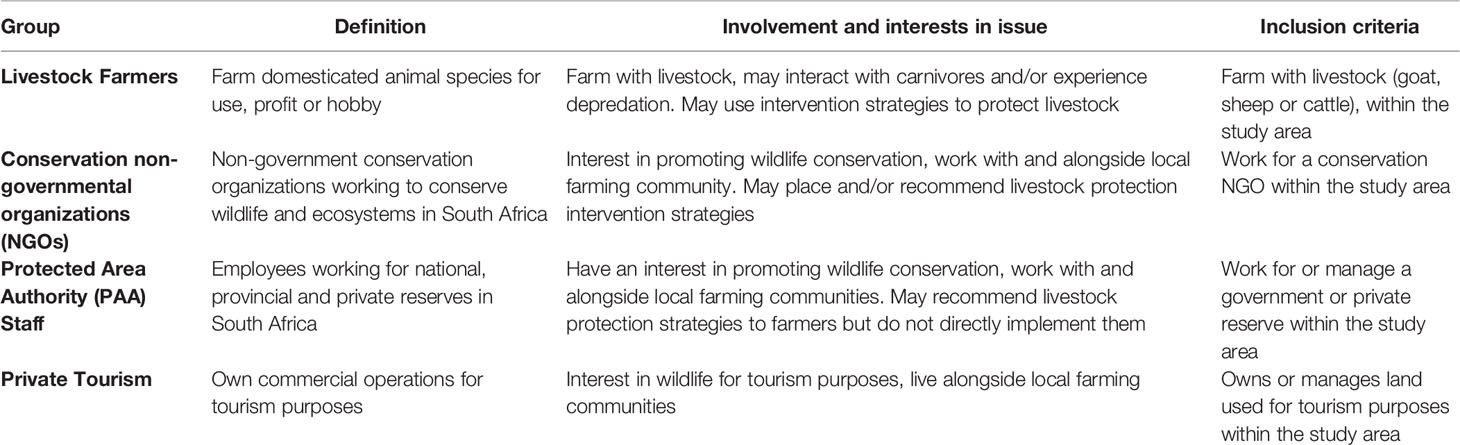

Table 1 Interview inclusion criteria for stakeholder groups involved in human-carnivore coexistence scenarios in South Africa.

2.3 Grounded Theory Interviews

2.3.1 Participant Recruitment

In grounded theory, a theoretical sample of informants is sought to provide diverse perspectives on a topic (Vaccaro et al., 2010). Therefore, the participants in the study were selected with the aim of including a range of stakeholders involved in HCC scenarios (Table 1 outlines stakeholder inclusion criteria).

2.3.2 Farmer Stakeholders

A combination of strategies was used to recruit farmers. Purposive, convenience sampling was initially used to target participants. Gatekeepers were used to help recruit livestock farmers who were using various types of intervention strategies. To recruit further participants, local events including livestock auctions and farmer union meetings were attended. Additionally, snowball sampling (Newing, 2011) was utilized when participants suggested other farmer(s) as a potential participant. From these community-based opportunities and gatekeepers, a database of all potential participants was created. Only farmers within 100km of the research base were contacted as this distance was deemed feasible for daily travel under existing road conditions.

Following grounded theory processes, initially only eight farmers were invited to participate. Further participants were recruited using theoretical sampling until saturation was reached [as per grounded theory methodology in which there is no pre-determined or standard sample size (Vaccaro et al., 2010)]. After conducting a number of interviews, it became possible to predict how a participant was likely to respond to particular questions based on their responses to initial questions and the responses provided by previous participants of similar backgrounds. Unlike other research methods, the processes of data collection and analysis in grounded theory are merged with the researcher moving back and forth between the two to ground the analysis in the data. The aim is to reach theoretical saturation i.e., when continued data collection fails to reveal or add any new information (Newing, 2011). Theoretical saturation was considered to have been achieved when this predictive ability occurred in >3 consecutive interviews within each stakeholder group.

Interviews were conducted with the person on the farm who identified themselves as having the most knowledge about the livestock. In most cases this was the farm owner (n=19). One interview was conducted with the farm manager.

2.3.3 Conservation, PAA and Tourism Stakeholders

Recruitment of conservation and PAA stakeholders followed a similar process to farmers whereby key informants were firstly used to identify possible participants. Snowball sampling was used to recruit the (single) tourism stakeholder whereby an NGO contact suggested the meeting.

2.3.4 Survey Instrument

Drawing on observations made in the key informant discussion, an interview guide was finalized and subsequently tailored to each stakeholder group. The questions were designed to explore perceptions of intervention strategy success and coexistence (Supplementary Material). Following grounded theory processes, the guide was amended and added to as the study progressed to allow for the exploration of emerging ideas and theories. The questions were designed to explore the following topics:

*Perceptions of and attitudes towards carnivores

*Livestock farming practices (either on the farm or used in the area, depending on stakeholder group)

*Use of intervention strategies/awareness of interventions used in the area

*Determining intervention success and factors contributing to success

*Perceptions of coexistence.

2.3.5 Survey Administration

Interviews were conducted by the first author between September 2019 and May 2020. Thirty-seven potential farmer participants were contacted via phone and invited to interviews. The majority (n=20) responded positively and interviews were subsequently arranged. Of the remaining 17, five responded with reasons to be excluded from the study including relocation outside of the area (n=2), cessation of farming (n=2) and being unwilling to participate (n=1). Potential participants who failed to respond to three messages and/or calls were excluded from the study (n=12).

Twenty-eight potential conservation participants were identified and contacted via phone and invited to interviews. Thirteen did not respond and four gave reason not to be included e.g., no longer working in the area or retired. Eleven responded positively and interviews were arranged. Six interviews were conducted in person at a location chosen by the participant. Due to restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 global pandemic (beginning March 2020 and continuing beyond the study end in December 2020), the remaining five interviews were conducted remotely using MS Teams (v1.4) or Skype (v8.72.0.82) (according to participant preference). Where possible, separate interviews were conducted with multiple people working for the same organization (n=6 of the eleven interviews were from 3 organizations).

Interviews were conducted at a location chosen by the participant. It was observed that the participant’s partner would frequently listen to the interview from a nearby room and would occasionally make comments in response to questions. These comments were included in transcription and identified as being made by someone other than the main participant. All conversations were conducted in English. The participants chose to provide their responses in English; an Afrikaans- speaking translator was available but not requested by participants. In-person interviews were recorded using a Dictaphone (Speak-IT Premier Digital Voice Recorder) whilst interviews conducted remotely were recorded using MS Teams recording function or Skype recording. After each interview, the researcher’s thoughts and observations on the interviews were recorded as field notes, as well as noting relevant details of conversations prior to and post interview. Participants were thanked for their time but not paid or rewarded for participation.

2.4 Participant Observation

Participant observation was conducted by the first author and occurred for the full duration of in situ fieldwork (July 2019 - March 2020). Participant observation involved observing and recording people in their daily lives and routines (Newing, 2011). Observations of behaviors and informal (unstructured) conversations were conducted with anyone from the stakeholder groups within the study area. Participant observation helped to triangulate data and provided the opportunity to test the accuracy and validity of interview data through further conversations and observations of behavior. Observations and conversations were recorded in the form of field notes.

2.5 Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed using semantic style transcription, adapted from Jeffersonian transcription protocols (Jefferson, 2004). During transcription of the key informant interviews, a transcription protocol was developed. The protocol was developed to allow for consistency in transcription and to reduce the chance of transcriber fatigue. The protocol listed what to include in transcriptions, formatting and use of symbols. As far as possible, transcription was conducted as soon after the interview as feasible. Data analysis and interpretation were conducted initially by the first author, with co-authors providing feedback and discussion at key points throughout.

Transcripts were coded following Charmaz (2006) using initial, focused and theoretical coding. QSR NVivo v12 (http://www.qsrinternational.com) was used to record the codes. Initial coding occurred line by line using gerunds to draw out the participants’ actions. Initial coding was followed by focused coding in which the most frequent or significant initial codes were identified. The theoretical direction of the coding was advanced through codes becoming more conceptual rather than line by line and tentative decisions were made about which initial codes made the most analytical sense. Theoretical coding was then used to help theorize the focused codes and identify relationships between the categories identified in focused coding. This process led to the formation of the overall analytical story.

Following the initial coding of the first eight farmer interviews, ideas and theories began to emerge. The emerging themes were reviewed and it was decided which needed further exploration. The original interview guide was reviewed and amended to include further questions to be asked to subsequent participants. Using theoretical sampling, further farmers were selected with the aim that subsequent interviews would contribute to emerging theories. Prior to conducting any interviews with conservation stakeholders, the interview guide was adapted to explore any emerging theories from farmer interviews which were worth exploring with conservation stakeholders. After conducting six interviews with conservation stakeholders, responses were then used to guide further farmer interviews (n=5). A similar process was applied for PAA and tourism stakeholders. In this way, responses were used to inform future interviews with different stakeholders to ensure that all emerging theories were explored among all stakeholder groups. This process of moving between data collection and analysis occurred throughout the study.

Alongside coding, analysis occurred through conceptual memo-ing. Memos are theoretical notes about the data and the conceptual connections between categories (Holton, 2007). Throughout the coding process, memos were kept to document the researchers’ reflections and thinking. Memos were used in the back-and-forth process between analysis, data collection and coding. Memos were used to define codes and theories, explore relationships between codes and make comparisons across the dataset.

Once all interviews were coded, theoretical codes and memos were used to draw out and identify the overall themes that contributed to participants’ perceptions of success and coexistence. Comparisons were made between stakeholder groups to draw out similarities and differences between the emerging themes. This resulted in the generation of the overall themes in relation to success and coexistence. As grounded theory uses a theoretical sample, the use of descriptive statistics in analyses is not appropriate; instead, the results focus on exploring the emergent themes.

Participant Observation

All field notes were digitized for analysis and entered into qualitative data analysis software (QSR) NVivo v12. Field notes were coded as above using initial, focused and theoretical codes to draw out concepts and theories from the observations. Coded data were integrated with interview data to allow for similarities and differences between emerging theories to be explored. Analytical memos documented reflexive thoughts and ideas throughout the coding process.

3 Results

Thirty-one interviews were conducted in total: 20 commercial farmers, 7 NGO workers, 3 PAA and 1 private tourism operator. Interviews lasted between 20 minutes and 1 hour 43 minutes with an average length of 45 minutes. All interviews were conducted in one conversation. Quotes are used throughout the text; participant ID is provided after each quote. “F” represents farmers, “N” represents conservation stakeholders. The classification groups were based on the participants employment type and not their values, beliefs or ethos. It is recognized that some farmers will also undertake conservation work or hold conservation beliefs, whilst some conservation workers will also farm. The classification of stakeholder type is therefore caveated as being purely based on their primary source of income.

Participants ranged in age from 27 to 81, with an average age of 50.5 years. Of the farming group, participants were predominantly male (18M, 2F). The majority of conservation stakeholders were also male (9M, 2F); all PAA participants were male. Nine farmers had a higher education qualification (ranging from diploma to BSc). All NGO and PAA stakeholders had a higher education qualification (diploma to MSc). Farmers in the study kept sheep, goats and cattle; 8 farmed with more than one livestock type, 9 kept only cattle, 2 only sheep and 1 only goats. Herd size ranged from 15 - 1500. Farms had an average size of 2290.25 hectares. Three farmers did not use any intervention strategy, but others used electric fence kraals (n=6), kraals (n=7), LGDs (n=7) or herders (n=3). Multiple strategies were used by 12/20 farmers. Use of lethal control methods (trapping, shooting and poison) was mentioned by 10/20 farmers. Period spent living on the farm ranged from 2- 72 years. Conservation stakeholders had spent between 1- 20 years in their roles.

Farmers in the study predominantly made their own decision regarding intervention implementation. The type(s) of intervention strategy used by farmers were not pre-determined or targeted by the researcher and therefore perceptions are likely based on a mixture of NGO-implemented and farmer- implemented methods, depending on each farmer’s method(s) of choice. Some farmers were or had been, involved in a LGD placement program operated by an NGO. In the program, LGDs are placed with farmers who enter into an agreement with the NGO to cease all forms of lethal carnivore control on the property. However, not all farmers were known by conservation stakeholders and not all farmers had been involved in conservation initiatives. Protected area authority stakeholders did not place intervention strategies with farmers but may have worked with farmers and conservationists, as well as recommended interventions.

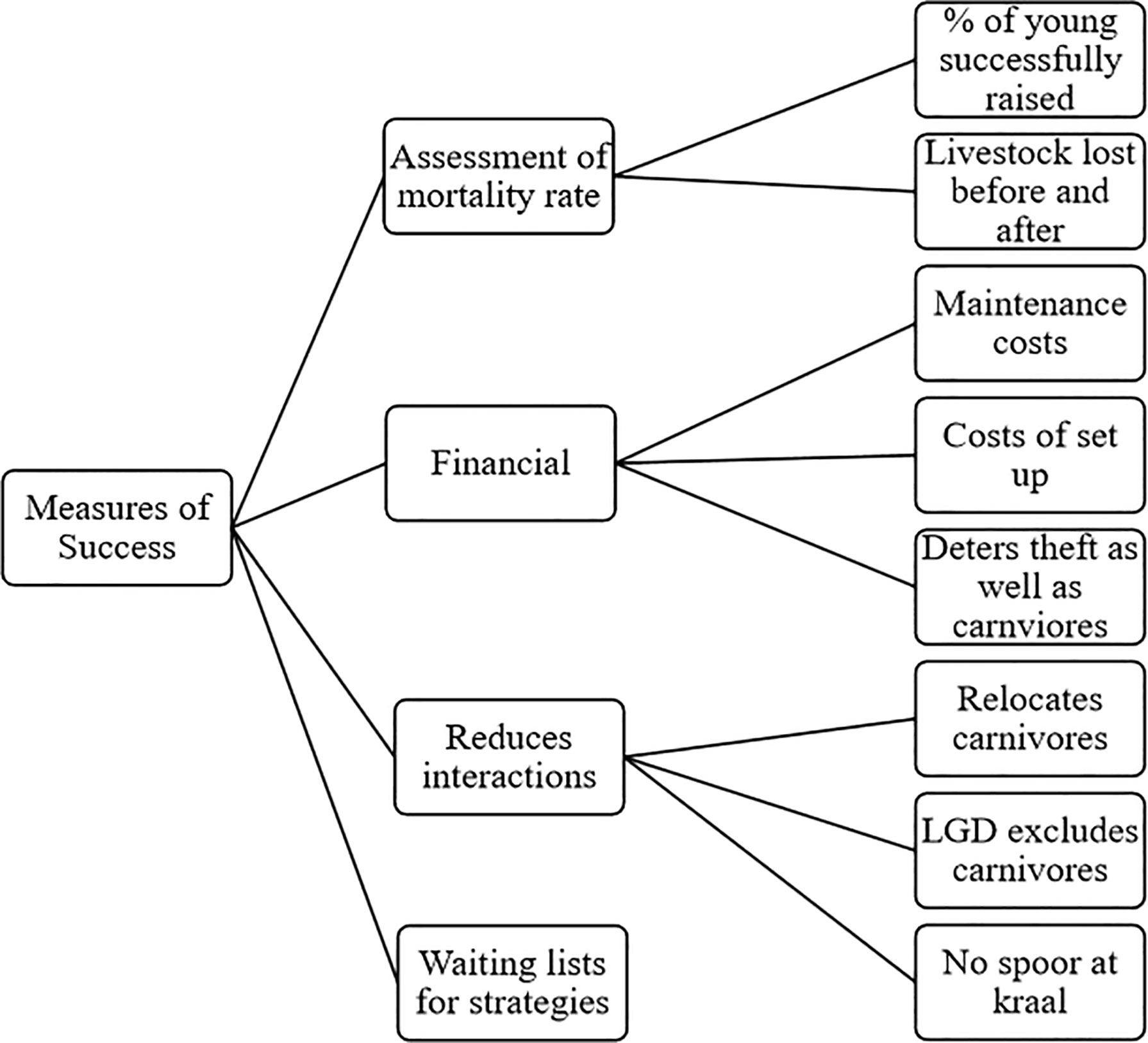

3.1 Stakeholder Measures of Success

The majority of participants (n=23/31) measured success by a reduction in livestock loss (Table 2). Change in livestock loss was measured in a number of ways: numerical difference between losses before and after interventions, reduced number of incidents of loss or injury and increased percentage of livestock successfully raised from birth. Change in potential for loss was also considered a measure of success (n=6/31). This was measured in a variety of ways: seeing less carnivore tracks at kraals, physical separation of livestock and carnivores (e.g. fences), and increasing the energy required by carnivores to get livestock (e.g. kraals or guards). Two farmers stated that they considered success of HCC interventions to be unmeasurable. “It’s one of those things you actually can’t measure” F20. One gave the reason that success cannot be measured as it is impossible to not known what livestock losses would be without the intervention. The other did not give any reason for their perspective despite being asked. There did not appear to be any relationship between a participant’s duration on the farm or in a conservation role, and their measure of intervention success. Specific success indicators were more diverse but showed commonalities between stakeholder groups. Measures of success and the relationships between them are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2 Stakeholder measures of intervention strategy success emerged in two main categories; illustrative quotes are used to describe the categories.

Figure 2 Specific stakeholder measures of success for human-carnivore coexistence intervention strategies and their relationships.

3.1.1 Determining Success

Over half of the farmers (n=13/20) believed that only they can measure/determine the success of interventions. “I think the farmers because most of the info comes from us” Partner of F09. Other farmers determined success using reports from herders or farmer managers. Some NGO stakeholders based their measures of success on reports from farmers. “From the project side that’s who we take our cues from on ok this isn’t working or this working, so I would definitely say ja it’s basically the farmers themselves” N07. In contrast, two NGO stakeholders thought that it is scientists who measure success.

3.1.2 Responsibility for Achieving Success

Over half of all participants (n=18/31) felt that the farmer was solely responsible for achieving success. “I’m the owner I cannot tell another guy it’s your responsibility, you know I must pay my salaries and I must you know make profit on the farm and so and so, no it’s my responsibility” F08. Two NGO participants reported that whilst most responsibility falls to the farmer, to succeed they must have support and collaborate with conservation organizations. “It’s the farmers main job but he has to have assistance from NGOs like us, there has to be collaboration between farming, the farming community and nature conservation organizations and the government nature conservation departments” N11. It was suggested by one conservationist that all stakeholders must take their share of responsibility to achieve success. One conservationist felt that farmers can want NGOs to take responsibility of intervention use.

3.1.3 Success Feasibility

All conservation stakeholders (n=11) thought successful intervention strategies were possible. However, a minority of farmers (n=3/20) felt that successful interventions were not possible. “There’s nothing yet that was successful” F07. Farmer perception here appeared to be influenced by past experiences with different intervention strategies.

3.1.4 Factors Shaping Perception of Success

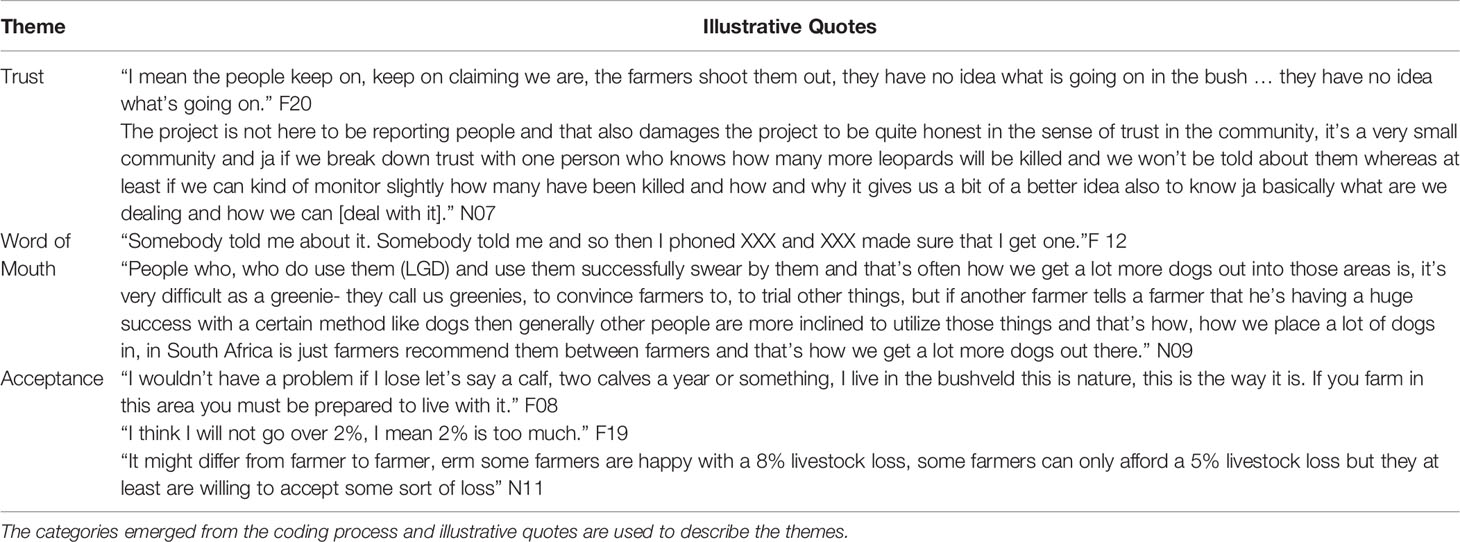

Three major themes emerged as factors that contributed to participants’ overall perception of success: trust, word of mouth and acceptance (Table 3).

Table 3 Following a grounded theory approach and using data derived from 31 interviews, three major themes emerged as factors that contributed to perceptions of success.

3.2 Perceptions of Coexistence

3.2.1 Defining Coexistence

Two phrases emerged as the most common ways to describe coexistence: “Live and let live” –was used by four farmers (F05, F13, F14 and F16). “Harmony” was also used by four participants: two farmers and two conservation stakeholders (Partner of F09, F15, N05 and N09). A common feature amongst participant’s definitions was an acknowledgement of being able to live in the same area and there being a place for people and wildlife. “Coexistence means that there, there’s a place, or there needs to be a place for each and everything. That’s coexistence, if I don’t have a place on my property for baboon or a place for a leopard then you don’t coexist” F10. “Well it’s living alongside with nature” N01.

3.2.2 Perceived Potential for Farmer-Coexistence to Occur

Coexistence between farmers and carnivores was thought possible by the majority (n=22/31) of participants. “Most definitely, they can coexist. A farmer might give you a way different answer. Yes I believe they can coexist with predators, it will be harder but you need to understand your role within the bigger picture and then you can coexist” N06. “Ja of course you can, like I said there’s plans to be made without just killing everything, you can be a livestock farmer and have jackal or hyena on your property. You don’t have to kill them all” F14. However, not all participants (n=4/31) thought that coexistence between livestock farmers and carnivores was possible. “So in that stage [if farming crops] I think it’s possible but when there’s livestock I don’t think it’s possible” F07. “Not if you live from your farm animals you won’t because leopard is in nature to catch a calf erm the price is, if we get a lot of money for our cattle and you can have a good living then I think we can tolerate it but at the moment the prices are so bad so you cannot lose one” F2.

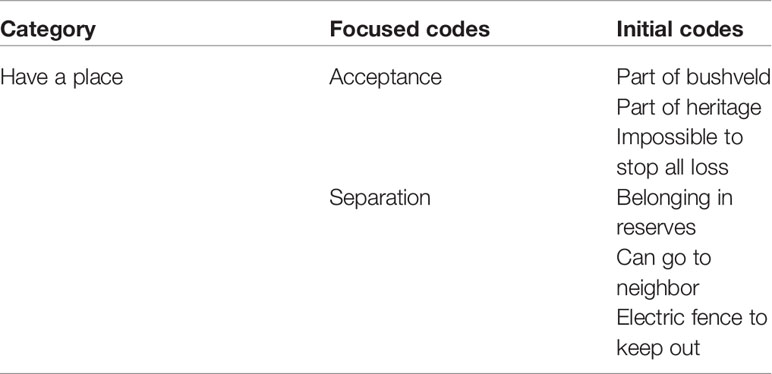

Population growth was considered a barrier to coexistence. “Not in Africa no, not with the er, not with the amount of human population growth erm no, it’s unfortunately not, it’s never going to happen” N09. Some participants (n=5; 4F and 1C) indicated coexistence to only be possible in reserves and protected areas. Whilst carnivores were considered to have a place within the South African landscape, precisely where this place was emerged in two opposing categories (Table 4).

Table 4 The initial and focused codes that make up the category of carnivores having a place in South Africa.

3.2.3 Factors Involved in Achieving Coexistence

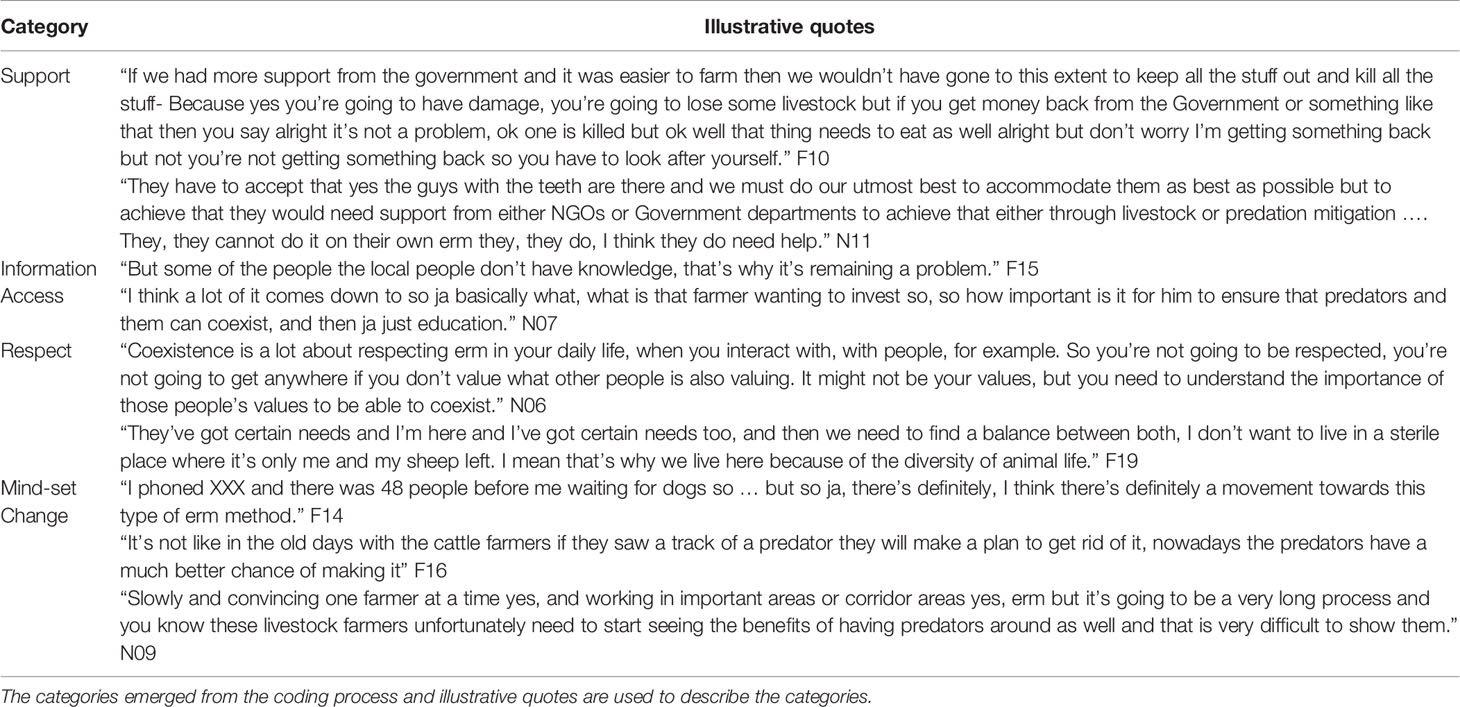

Four categories emerged as factors that will need to be addressed in order to achieve coexistence (Table 5).

Table 5 Following a grounded theory approach and using data derived from 31 interviews, four major categories emerged as being necessary to address to achieve coexistence.

4 Discussion

Our use of a Charmazian grounded theory approach to exploring stakeholder perceptions of HCC intervention success and its measurement enabled a deep and insightful understanding of human-carnivore interactions in this South African rural community. The use of grounded theory provided an in-depth insight into the perceptions of different stakeholder groups, their interactions and communications. The richness of the data generated, and the subsequent theories that emerged from them have revealed new insights into the key factors involved in stakeholder perceptions of intervention success as well as the personal and context-specific nature of HCC. Whilst the majority of stakeholders used livestock loss to measure success, perceptions of success were not just shaped by livestock loss but influenced by various personal factors such as livestock type, herd size and source of income. Most participants felt that coexistence was achievable, four expressed that it was not. This kind of inter- and intra- stakeholder disagreement can have important impacts within a community or project area, even if they happen to be shared by only a minority. Such findings highlight the importance of understanding stakeholder perceptions of success and coexistence, as well as the factors that shape these perceptions. Understanding the social reality of the stakeholders is key to tailoring interventions to different scenarios in order to achieve optimal effectiveness for all involved (Pooley et al., 2017). For example, issues of power or authority and inequality (real or perceived) in economic circumstances or political representation/protection likely reflect in the varied individual circumstances and responses to HCC (Margulies and Karanth, 2018), as found in this study. In this sense, the individual circumstances explored here might be shared by many people but do not necessarily fully reflect the suite of situations arising from diverse economic and political systems. Exploring stakeholder perceptions through a political ecology perspective may therefore be beneficial to future studies of HCC scenarios.

4.1 Measures of Success

Farmers and conservationists were typically measuring success in the same way. Similar to other published studies, livestock loss was quantified in a variety of ways including number of livestock lost, percentage loss of stock, loss of stock per period or financial loss (Inskip and Zimmermann, 2009; van Eeden et al., 2018a), highlighting the reliance on livestock indicators by end-users of intervention methods. Furthermore, the use of change in potential for loss as a measure of success aligns with other studies investigating the potential for attacks, e.g., carnivore visitation rates (Miller et al., 2016). The research bias towards using self-reported livestock loss as a measure of effectiveness, evident in current literature, has been widely criticized (van Eeden et al., 2018b; Ohrens et al., 2019; Khorozyan and Waltert, 2021), primarily due to its reliance on recall, and its lack of objective/empirical determination. However, our findings demonstrate this bias to exist at the grass-roots level and is not peculiar to the research community. Moreover, the majority of participants considered farmers as being the stakeholder group able to provide livestock loss data, with very few considering scientific studies as a source of this information. The phrases used by participants from all stakeholder groups to describe measuring success with livestock loss (Table 2) include ‘obviously’, ‘it’s easy’ and ‘the only’, indicating that this measure is a bottom-line argument; success is only about a reduction in livestock loss, and considerations about wildlife or people are not necessarily taken into account.

Use of reported reduction in livestock loss (i.e. relying on self-reported changes following intervention implementation to determine success) without a control group has been described as a measure of perceived rather than functional effectiveness and criticized as such (van Eeden et al., 2018b). Such reliance on livestock loss may be explained by availability heuristics (Tversky and Kahneman, 1973) in which livestock loss comes to mind most easily and consequently assumed to be most important when evaluating interventions. Despite this, some research has demonstrated links between levels of livestock loss and levels of predator removal (Ogada et al., 2003; Shivik et al., 2003). This suggests that whilst perceived reduction in livestock loss may not directly correlate with increasing HCC it is probably a key indicator (van Eeden et al., 2018a). In the current study, use of reduction in livestock loss to determine success was used by participants from all stakeholder groups and therefore may be the most relevant measure to develop shared perspectives of intervention success. If livestock loss is the measure used by farmers and determines whether or not a strategy is utilized, alternative measures of success may be meaningless to farmers and more abstract concepts more difficult to visualize, ultimately reducing engagement with HCC programs. This scenario may also benefit from consideration of the influence of emotions, heuristics and biases within each stakeholder group; communication strategies which foster co-development of intervention methods and evaluation measures would likely be essential (Reed et al., 2009)

Concern has been raised over the use of farmer perceptions as measures of intervention success; i.e., the reliance on farmer recall or anecdotal records of changes in livestock losses may render these data less reliable than those collected under more controlled or purposefully designed experimental conditions. However, this stance may be overlooking the importance of these perceptions in driving behaviors relating to the wildlife or the use of (or decision not to use) an intervention. Likewise, if a farmer perceives the intervention successful (based on livestock parameters) and subsequently changes their behavior or attitude towards carnivores, whether or not the intervention is functionally effective becomes redundant, so long as that perception is maintained. If success is determined by reduction in livestock loss as indicated by farmers and users are satisfied with interventions, the role of conservationists therefore may not just be to evaluate success but to concurrently help facilitate or measure changes in behavior and attitude to ensure increased HCC. Arguably the role of conservationists then becomes one of managing perceptions, rather than focusing solely on scientifically objective measures. Indeed, the latter may even be counter-productive when stakeholder perceptions are firmly held or any level of mistrust exists between end-users and conservation or scientist stakeholders (see (Terblanche, 2020)). Having said that, the use of livestock parameters is entirely anthropocentric and does not consider the wildlife dimension of success. Livestock loss could therefore be described as a measure of potential for coexistence, but measures of wildlife occupancy and behavior would be required in order to measure true coexistence. This suggests that a more nuanced and holistic or multi-dimensional approach to evaluating success is needed, especially when it comes to measuring long term success and sustainability. This scenario may also benefit from consideration of the influence of emotions, heuristics and biases within each stakeholder group; communication strategies which foster co-development of intervention methods and evaluation measures would likely be essential (Reed et al., 2009).

4.2 Perceptions of Success

Whether success was perceived as achievable was associated with strong economic drivers; for all stakeholders, success was considered easier to achieve if the farmer was financially better off. Such perceptions, particularly by farmers, may indicate a feeling of success being out of reach financially if perceived costs are high. Additionally, it may also provide a reason or excuse as to why success has not been achieved. Moreover, slightly over half of participants (n=17/30) felt that measures of success must develop from the farmer themselves. Two NGO stakeholders expressed the idea that farmers must have NGO help to achieve success; in reality this is not a sustainable practice and may indicate a desire by NGOs to preserve or justify their own existence. However, it may also reflect a recognition of shared responsibility, attempting to ensure that the burden does not fall to farmers alone.

For the intervention to be considered successful, the costs of using and maintaining the method must enable local users to make a profit from livestock. Such perceptions of success may be reflective of the commercial nature of the farming participants such that subsistence farmer perceptions may differ. For some farmers, whether success could be achieved was dependent on the livestock species farmed; success was considered more difficult to achieve with cattle in comparison to small stock (sheep and goats). Kraaling of stock at night, when many carnivores are most active, was also considered a major factor in achieving success. However, five farmers did not consider kraals a successful method for cattle, reporting that it decreased their health, increased disease, increased costs of food and increased labor costs to bring cattle to and from the kraal. Whilst losses to small stock may be greater in comparison to larger sized cattle (Badenhorst, 2014), they were also considered easier to manage with interventions. The species farmed and livestock husbandry practices utilized may therefore affect whether farmers perceive that interventions can be successful. Other limitations to being able to achieve success included carnivore habituation, unwillingness to take responsibility, and a lack of financial means to invest in interventions. “Tried different things over the years bells and this and err I don’t … none of them in the long term it works, every little thing that you change works for a short while until the predators going to figure it out” F03. The duration of intervention effectiveness is an important characteristic of success evaluations (Khorozyan and Waltert, 2021) and represents a shared concern between stakeholder groups. Carnivore habituation to interventions occurs faster in human-dominated areas where they are likely to be more exposed to artificial novelties (Blumstein, 2016). Measures of success should therefore take into account habituation and consider whether success may have a time limit (Eklund et al., 2017).

Unwillingness to take responsibility to achieve success may occur due to lack of resources or knowledge, it may also reflect antagonism between stakeholder groups in which the protection of wildlife is assigned to conservationists, or blame is levied at each other. “I mean the people keep on, keep on claiming we are, the farmers shoot them out, they have no idea what is going on in the bush … they have no idea what’s going on” F20. “Some of the farmers are very proactive and they will do a lot to try and protect their herds but other farms are not as proactive erm where they don’t really try and do they just blame everything on anybody else and ja it’s not, it’s not their problem and they just, they will just take care of it” N11. In such cases, carnivores can become viewed as problem animals associated with, and considered owned by, conservationists rather than being perceived as natural (Macdonald et al., 2010). This could negate the need to protect livestock as the problem perceptually belongs to others and conducting retaliatory killing could therefore be considered a way to spite conservationists (Terblanche, 2020). Furthermore, if the drivers for attitudes or behaviour towards predators are related to other stakeholders and not the predators themselves, interventions aimed at reducing livestock loss or changing predator behaviour will be worthless (i.e. unsuccessful) in facilitating coexistence. This emphasizes the need to understand not only stakeholder-specific perceptions of the topic, but inter-stakeholder perceptions as a potential driver of conflict over (rather than with) wildlife (Redpath et al., 2013).

Only farmer participants thought success was unachievable; this difference between stakeholder groups suggests that improved dissemination of information on successful interventions among the farming community is needed. However, it should also be considered whether conservation stakeholders are unrealistic in their expectations of achieving success or whether they may have a vested interest since without success being considered possible, their role becomes unclear. “You know if we could get towards farmers and, and predators to coexist in South Africa we’ll have achieved something huge” N09. This may also be indicative of a belief that when a project succeeds, NGOs may assume the right to claim ownership but when a project fails it is reasonable to assign blame elsewhere. Additionally, there is also a need to better understand why some farmers perceive interventions as unlikely to be successful. Previous intervention failures and lack of trust in other strategies emerged as factors likely to be important in shaping such perceptions. The differences in opinion as to whether success is achievable demonstrate the role of qualitative approaches in exploring and understanding similarities and differences among stakeholder groups, as highlighted previously (Sutherland et al., 2018).

Of particular note was a minority (n=3/20) of farmers who expressed the view that the killing of carnivores by LGDs was a sign of success. Killing or harming behaviors towards wildlife were not explicitly asked about in interviews and such LGD-interactions were not mentioned by 12 of the 13 LGD-using stakeholders interviewed. These LGD-wildlife interactions are reported in the literature (Smith et al., 2020) and typically considered undesirable from an ecological or conservation perspective. However, from a functional livestock protection perspective, the prevention of depredation by any means (lethal or non-lethal) is regarded as a successful outcome of the LGDs use by farmers. The potential misalignment between farmer and non-farmer perception of LGD success parameters is of concern for a number of reasons. Lethal LGD-carnivore interactions may go unreported by farmers either for fear of causing conflict with wildlife-focused stakeholders, or because they are not perceived as a problem behavior (i.e. the dog was performing its role). This represents a limitation to LGD evaluations, as well as any efforts by NGOs placing LGDs to identify and mitigate such behaviors. A balance must be struck between meeting the expectations of intervention users (which may include the removal or exclusion of predators from their property, e.g. by LGDs or fences) and the expectations of other stakeholders who may view such interactions less favorably. The extent and frequency of these interactions must also be considered; in scenarios where LGDs are highly targeted and defensive towards carnivores directly threatening herds they may be justified as a more responsible means of livestock protection than indiscriminate poisoning or shooting, such that a low incidence of carnivore mortality associated with their use could be deemed tolerable (Whitehouse-Tedd et al., 2020). However, evidence of their interaction with non-target species (Whitehouse-Tedd et al., 2020) counteracts such reasoning. Moreover, in other scenarios the combined farmer and LGD-induced carnivore mortality was greater post LGD-placement compared with farmer only induced mortality prior to LGD placement (Potgieter et al., 2016). Hence, including measures of human behavioral changes (or lack thereof) alongside outcomes of the intervention itself is essential for determining the extent of coexistence. In situations where interventions do not concurrently lead to desired changes in human behavior, even a low incidence of intervention-induced cost to wildlife could be enough to increase wildlife mortality (or other form of negative impact) overall.

4.3 Factors Contributing to the Perceived Extent of Success

4.3.1 Trust

Building trust and creating meaningful engagement between locals and conservationists is fundamental in understanding perceptions and achieving successful conservation outcomes (Waters et al., 2018). Levels of trust between farmers and conservationist (NGO and PAA) stakeholders were diverse, with a minority of farmers (n=2) giving all conservation stakeholders the nickname ‘greenies’. This suggests some inherent preconceived ideas about conservationists and their work which are based on a stereotype, potentially undermining their actions on the basis of being perceived to be driven by a particular broad agenda rather than a specific reality.

Conservationists by definition do not hold neutral roles, especially in the context of heightened human-wildlife interactions (HWIs) (Redpath et al., 2013; Brittain et al., 2020), and therefore it is important for conservationists to consider how they may be perceived by other stakeholders. To try and reduce or dispel any preconceptions in order to build trust, it is vital to be visible, transparent and have a presence in farming communities (Young et al., 2016). Equally important is recognition by conservationists of their role as a stakeholder and whether preconceptions in the community may discourage open communication regarding local beliefs and practices (Muhar et al., 2018).

Farmers may be supported by conservationists on the proviso that farmers will cease all lethal control on their property. Conservationists must therefore trust farmers to adhere to this and report any issues. Developing a productive relationship between stakeholder groups was thought by all stakeholder groups to take time, and farmers must have a certain level of trust in conservation stakeholders before asking for support. Good communication is vital in building a relationship and must be made using culturally appropriate terms that makes clear the expectations of all parties involved. Local socio-political customs should be acknowledged; for example, one NGO highlighted how they employed staff with differing backgrounds to work within different communities which helped increase trust and intervention uptake in their project. This is particularly important in a socially diverse country like South Africa.

4.3.2 Word of Mouth

Farmers were more likely to adopt and use an intervention strategy if another farmer had used it with success. Communicating the success of interventions via word of mouth between farmers is likely to have the biggest impact on uptake. This aligns with previous work in this farming community on the uptake of one specific intervention method (LGDs) (Wilkes et al., 2018) and with psychological theory explaining the importance of subjective norms in influencing intention to use interventions, i.e. livestock owners behaving in a manner perceived to be socially acceptable (Eklund et al., 2020). Here we heard about it from a friend of mine. He got a dog from XXX and he tell me I must phone XXX and ask for a dog because that dogs that dog he gets is protecting his goats” F06. “If you place a livestock guardian dog and we go to the neighbor no, no, no I don’t want a dog but give it a year or two, maybe three then he say ah man yeah I think I want a dog by now, I’ve had neighbors requesting a dog after 10 years because they see the success their neighbor had with these dogs” N11. Whilst this farmer-farmer communication offers a more direct and possibly more relevant or trustworthy source of information for intervention users (compared with that offered by conservationists), it also means that bad experiences with interventions are likely to be equally (or more) widely disseminated and could represent a barrier to wider uptake. “In a lot of areas I do know they have a bad name or reputation but it’s for us to go into those areas and actually to place a few and then to be successful to, to show farmers that they do work and then, then generally you have a lot more success” N09.

The reputation (regardless of accuracy) of an intervention strategy can therefore spread quickly through farming communities and must be taken into consideration when implementing interventions and evaluating success. In cases where the reputation is erroneously based on rare instances of failures (perceived or real), this can have long-term implications for program uptake and could result in farmers choosing to avoid implementing a method that, in reality, is likely to have beneficial outcomes for them. Moreover, the method of determining success (or failure) is again important to consider. Whilst scientifically determined effectiveness (using objective and controlled experimental designs) are undoubtedly important (van Eeden et al., 2018b), perceived effectiveness may be more likely to be disseminated within the farming community via word of mouth. For interventions that have previously failed (and therefore deserve their poor reputation), choosing to avoid implementing that method is likely to be a sensible decision for farmers. It therefore becomes necessary for those responsible for implementing or advocating the intervention to either remedy it, or to replace it with a more successful one in order that trust be maintained between farmers and conservationists. It hence becomes equally important to address misinformation in order to retain or rebuild trust. In any scenario, open and honest discussion surrounding the causes for previous, perceived or existing failures, and integrating objectively determined effectiveness measures with end-user perceptions, is vital in order that farmers can make informed decisions. The sustainable use of any intervention is therefore reliant not just on its ability to function in the manner expected, but for its effectiveness to be communicated accurately and widely via trusted sources.

4.3.3 Acceptance

The majority of participants from all stakeholder groups acknowledged that it is impossible to stop livestock losses completely; losses to carnivores were largely considered part of farming in the area. “If you start farming you must know you are going to have some losses that is part of life, part of farming yes” F02. However, there was also a clear discrepancy between stakeholder groups as to what is an acceptable level of loss. Farmers would typically tolerate low percentage losses, e.g. 1-2%. “Maybe one percent or two percent but if it gets more than that then you have to get somebody, if you can’t do it yourself, you must ask somebody to put a cage or relocate the animal or something like that” F02. “I wouldn’t have a problem if I lose let’s say a calf, two calves a year or something, I live in the bushveld this is nature, this is the way it is. If you farm in this area you must be prepared to live with it” F08. In contrast, conservation stakeholders felt that farmers need to be prepared to accept much higher levels of loss, even up to 10%, here again revealing an apparent mismatch between stakeholder expectations and perceptions of each other. “Unfortunately um a lot of these farmers, they don’t want to lose any animals to, to predation erm they have an unrealistic expectation of farming in South Africa, you know you need to almost expect at least 10% loss of your animals to predators and that’s not that bad actually whereas the expectation, well in South Africa they don’t tolerate 1%” N09. NGO stakeholders may potentially be out of touch with the reality of the situation, or have expectations that do not align with those of end-users. Nonetheless, highly individualized perceptions of acceptable losses were exhibited among farmers and appeared to be shaped by factors including herd size and dependency on livestock for income. Importantly, this farmer-specific variability was appreciated by some NGO stakeholders. For example: “It might differ from farmer to farmer, some farmers are happy with a 8% livestock loss, some farmers can only afford a 5% livestock loss but they at least are willing to accept some sort of loss” N11. In order to reduce retaliatory or preventative killing of carnivores, the point at which farmers become intolerant to losses needs to be understood (Crespin and Simonetti, 2019); this should form the basis for any intervention goal. Where farmers’ tolerance for losses (i.e. the maximum number of stock they would be willing to lose) is considered to be unrealistic by conservationists, understanding and considering the drivers for the threshold becomes even more imperative. In these scenarios there may be non-biological factors at play that lead to a near zero tolerance for livestock losses, e.g. economic vulnerability, social conflicts, sense of disenfranchisement or empowerment, or redirected antagonism towards wildlife arising due to other socio-political circumstances, as documented in the Karoo (Terblanche, 2020).

4.4 Perceptions of Coexistence

4.4.1 Defining Coexistence

The overall themes emerging for “coexistence” within the stakeholder groups here were similar to those used in the literature, i.e. that coexistence occurs when the interests of humans and wildlife are both satisfied, or when a compromise is negotiated to allow the existence of both humans and wildlife (Frank, 2016). However, unlike the scientific literature in which the precise definition of coexistence varies considerably among HWI studies, stakeholders were broadly in consensus that coexistence relates to humans and wildlife being able to live together. This is particularly encouraging given that a common definition will facilitate agreed aims and goals. A shared understanding of coexistence should be key to any project aiming to increase HCC but has often been overlooked previously and risky assumptions made regarding stakeholder perceptions and definitions of coexistence.

4.4.2 Feasibility of Coexistence

The possibility for coexistence to occur was caveated by farmers, such that it was considered feasible only if their livelihood from the farm was concurrently viable. “I have a place for everything but if they cost me money or damage or something I’ll try and keep them out the way without hurting them or killing them then you can, you coexist” F10. In line with a previously identified economic basis for intervention success, the farmers using phrases such as ‘live and let live’ or living in ‘harmony’ with nature, were also those that had multiple sources of income and did not rely on livestock for their main source of income. This diversity in income streams likely provided some buffering against economic impacts of livestock loss and appears intricately linked to the belief that some losses are an inherent part of the farming system. This follows other studies that found people dependent on single livelihood strategies more hostile towards carnivores (Dickman, 2008). This was reaffirmed when farmers indicating that coexistence was not possible cited financial loss as a major barrier to coexistence; with participants expressing that if they were unable to make a living, they did not feel able to coexist with carnivores. To this end, livestock farming was considered unconducive to coexistence by its very nature, whereas crop farmers were perceived to be able to coexist with carnivores as their income would not be impacted by carnivores. “If you do it otherwise like crops I mean it’s not a problem they don’t eat veggies so it can but not with livestock no” F08. Such emphasis on financial factors were a common reason for not wanting to coexist with carnivores on farmland in previous studies (Lindsey et al., 2013) and here suggest that it is not the carnivores per se that the farmers do not tolerate, but the outcome of negative interactions. However, in the current study, other factors such as the market price of livestock also affected how much carnivore-related loss farmers were prepared to accept and in turn whether they perceived coexistence to be feasible. This indicates that perceptions of coexistence are likely to be capricious over time as well as dependent upon a suite of individual circumstances.

More tangible and constant factors, such as livestock management and the use of interventions were also important in facilitating the perceived feasibility of coexistence. “By protecting your animals against them, like with a dog, so that they can’t come and make damage … yes I think absolutely” F12. Some NGO participants took ownership of a perceived success in demonstrating coexistence. “Yes I think we’ve proved it in our project we, have proved it, it is possible erm for predators and farmers to coexist” N11. Whilst encouraging to see such positivity and claims of success, this brings the additional consideration of who is responsible for the success (or failure) of an intervention, and the possibility that such perceived ownership by one stakeholder may inadvertently disrespect reciprocal contributions by other stakeholders. Use of the term ‘we’ by the conservationist suggests a feeling of ownership over the project as well as responsibility for achieving coexistence, and contrasts with other NGO statements in regards assignment of blame. This may be indicative of a subconscious bias or underlying belief but, perhaps most importantly, it reiterates the need to acknowledge inter-stakeholder dynamics and their potential impacts on the ability for coexistence to occur.

Biological factors were also recognized by stakeholders and the availability of natural prey was recognized as playing a role in whether coexistence is possible. “I think we can live together but depends on the elements, if there’s enough food, they won’t catch each other but if there’s not enough food, that’s [quite] a problem” Partner of F09. Likewise, an increasing human population was considered a factor preventing coexistence. As the human population continues to expand, with the Limpopo province experiencing an annual population growth rate of 0.89% (Anon, 2016), HWIs have arguably become more complex (Frank et al, 2019) along with solutions to preventing conflict over wildlife. This factor may also be perceived as beyond the control of individuals, therefore putting ‘success’ further out of reach and influencing associated behavioral intentions accordingly. The sense of hopelessness expressed here suggests conservationists may feel they are fighting a losing battle. Such feelings could further exacerbate tensions between stakeholder groups but also influence their aims and what they would consider successful in coexistence goals. Expanding human populations and/or habitat fragmentation are often considered as major causes of increasing negative interactions between people and wildlife (Ocholla et al., 2013).

In common with findings pertaining to the willingness to take responsibility and a perception that carnivores are owned by, associated with, or the responsibility of conservationists (i.e. not the farmers’ fault or concern), carnivores were considered “nice to see” in national parks or zoos but not on farmland. “If they are in like the Kruger National Park- I think you can live with them. But not here” Partner of F04. “The guys that want to protect them they must take them. I don’t like them, go to the zoo if you want to look at them because we must live here and they make so difficult for us to live, to, to, to make a living so and these things stay they make it difficult for us to live here” F20. The somewhat paradoxical idea that separation between people and carnivores is needed for coexistence was reflected in one farmer’s reason for using electric fences. “I put electric fence on so then they can’t get in but I don’t kill them so they can coexist outside, so yeah I would like them to disappear from this area and let them be in a different area and if I want to see them I’ll go to that area” F10. Desire by farmers to separate people and carnivores as a means to achieve coexistence has been noted in other studies (Whitehouse-Tedd et al., 2021). However, the idea of exclusion contrasts with the perceptions of others from all stakeholder groups who considered carnivores a natural part of living in the bushveld, but often on the condition that they occurred without cost to farmers’ livelihoods. Whilst spatial and temporal considerations were important in shaping perceptions of coexistence it could be argued that it is not true coexistence if people and carnivores are separated. This relates to the importance of using definitions and metrics determined to be relevant to the stakeholders involved. As such, the concept of co-occurrence (in which two or more species occur within one ecological community but without any direct interaction), rather than coexistence (in which interaction occurs but there is no net impact for either species) (Harihar et al., 2013), may better define what many conservationists and farmers alike are striving to achieve in agricultural contexts.

4.5 Factors Involved in Achieving Coexistence

Whether coexistence is perceived as possible can depend on time and place. In conservation, this has resulted in debates regarding the concepts of ‘land sparing’ versus ‘land sharing’ (also known as wildlife-friendly farming) (Green et al., 2005; Fischer et al., 2014). Whilst protected areas are vital in carnivore conservation, many reserves in Africa are not large enough to maintain viable populations of wide-ranging carnivores and in order for them to survive they will need to persist beyond the borders of protected areas (Durant et al., 2017). For those living on the borders of protected areas, tensions are often heightened and damage to livelihoods can reduce support for conservation initiatives (Anthony, 2007). Given the ever-increasing presence of humans across landscapes, coexistence with carnivores will require sharing land in many, if not most, contexts across the globe (López-Bao et al., 2017).

The notion that farmers must have support from conservation or government stakeholders in order for coexistence to be achieved was apparent across all stakeholder groups. Conservationists would likely benefit from working to gain farmers trust and provide support in a locally appropriate manner so that interventions designed to facilitate HCC are accepted and used. Likewise, farmers must be aware of (and have access to) the support available to them, along with knowledge of the available strategies and how best to utilize them to achieve the desired outcomes. Information about interventions should be made widely available in a format that is appropriate to local stakeholders.

Stakeholders are likely to hold different values towards wildlife and it is particularly important for conservationists to advocate for wildlife in a way that respects local values and beliefs (Jordan et al., 2020). In the current study, stakeholder groups acknowledged that whilst they may not have the same perceptions, they must respect each other’s values to enable the collaboration needed to achieve HCC. If interventions are implemented without understanding and respecting the values of other stakeholders, conflicts between stake-holder groups could escalate and challenge attempts to increase HCC (Eklund et al., 2020).

Interestingly, a change in farmers’ mind-set was considered important by all stakeholder groups, including farmers themselves. This demonstrates farmer-reflexivity that has arguably been unacknowledged in the conservation practitioner and academic literature. Whilst historically farmers may have attempted to eradicate carnivores on their property, participants indicated that this was beginning to change, and the younger generation was now more willing to coexist with carnivore species. This is similar to other studies that found use of non-lethal interventions has increased relatively recently (Treves and Karanth, 2003). For this mind-set change, farmers must either be motivated to coexist with carnivores or to at least use non-lethal forms of livestock protection instead of lethal methods for other reasons (e.g. reduction of financial loss); in either case this must translate into a willingness to participate in achieving this. It must be recognized that changing people’s attitude or tolerance towards wildlife is likely to occur slowly (St John et al., 2018). Subsequently, changing even just one farmer’s behavior towards carnivores could be regarded as a conservation success, especially in light of our findings in regards word-of-mouth.

5 Conclusions

Participants in this study predominantly measured success as a change in livestock loss as reported by the farmer. The use of livestock loss to determine success can perhaps be explained by cognitive biases in the form of availability heuristics which suggests that because livestock loss comes to mind most easily when evaluating success, it must be most important. Such cognitive biases may explain why livestock loss is a measure of success that can be understood by all stakeholder groups. Recent calls in the scientific literature for evaluations of HCC interventions to place greater focus on the use of controlled experimental designs and reduce reliance on farmer perceptions may not suit the interests of all stakeholders. Since stakeholder groups largely agreed that farmer-derived data on changes in livestock loss was the preferred measure of success here (and potentially elsewhere), assessing changes in attitude and behavior as a result of intervention use may be more important than assessing functional effectiveness to ensure interventions are achieving desired goals.

Ownership and responsibility emerged as areas with potential for human-human conflict to arise and highlighted how sub-conscious biases may shape the perceptions of conservation stakeholders and whether success can be achieved. Furthermore, the role of conservation stakeholders must be considered in HCC scenarios, whilst their role is to help facilitate and enable intervention use (e.g. through promotion and distribution), ultimately the farming community will only use interventions they perceive as successful. Word of mouth among farmers emerged as the best method to share successes, demonstrating the importance of subjective norms in driving perceptions and use of interventions. However, farmer networks can also spread negative information about interventions and one failed experience can have wider repercussions which impacts perceptions of success. In such scenarios, neither quantitative statistical evaluations of farmer support for an intervention, nor treatment versus control studies, would be able to adequately relay this information and its potential consequences. In-depth qualitative studies highlight the impact that the extreme minority could have on achieving HCC goals. Furthermore, given the confidence placed in word of mouth for the dissemination of intervention success (and failure), the sustainability of any intervention’s usage is dependent on the maintenance of perceived effectiveness. It is therefore likely that a combination of both perceived and functional effectiveness must be achieved for any intervention to be useful in facilitating HCC in the long-term.

Given the grounded theory approach used in the study, it is not appropriate to extrapolate or generalize the findings. Nonetheless, although the findings of this study are primarily specific to this HCC scenario in South Africa, the fundamental principles of using intervention dissemination and evaluation parameters of direct relevance to end-users, as well as acknowledgement of the importance of inter-stakeholder discord and its resolution, as revealed here, can be applied globally. Moreover, the methodology is not specific to this context and a grounded theory approach would be a valuable addition to the study of human-wildlife interaction situations globally to draw out novel aspects of scenarios and gain a more in-depth understanding of stakeholder perceptions.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Nottingham Trent University School of Animal, Rural and Environmental Sciences Ethical Review Group (ARE880). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CL, KW-T, JA and SB-H conceived and developed the project. CL collected and analyzed the data and wrote the original draft. All other authors contributed to editing the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by The On Track Foundation and C.L was supported by a Nottingham Trent University studentship for the duration of the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the gatekeepers for their support and introduction to participants. We thank the participants for their time. We would also like to thank AWCRC, PPP and COT for their logistical support.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2022.906405/full#supplementary-material.

References

Anon (2016). Limpopo Environment Outlook Report. Limpopo Provincial Government. Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism. Available at: https://soer.environment.gov.za/soer/UploadLibraryImages/UploadDocuments/300819113929_Limpopo_Environment_Outlook_Report_2016.pdf

Anthony B. (2007). The Dual Nature of Parks: Attitudes of Neighbouring Communities Towards Kruger National Park, South Africa. Environ. Conserv. 34, 236–245. doi: 10.1017/S0376892907004018

Badenhorst C. G. (2014). The Economic Cost of Large Stock Predation in the North West Province of South Africa.

Bennett N. J., Roth R., Klain S. C., A Chan K. M., Clark D. A., Cullman G., et al. (2016). Mainstreaming the Social Sciences in Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 31, 56–66. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12788

Blouberg Local Municipality (2014). Integrated Development Plan 2014-2015 (South Africa: Senwabaranwa, Blouberg Municipality).

Blumstein D. T. (2016). Habituation and Sensitization: New Thoughts About Old Ideas. Anim. Behav. 120, 255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.05.012

Bogezi C., van Eeden L. M., Wirsing A., Marzluff J. (2019). Predator-Friendly Beef Certification as an Economic Strategy to Promote Coexistence Between Ranchers and Wolves. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00476

Boronyak L., Jacobs B., Wallach A. (2020). Transitioning Towards Human – Large Carnivore Coexistence in Extensive Grazing Systems. Ambio 49 (12), 1982–91. doi: 10.1007/s13280-020-01340-w

Brittain S., Ibbett H., de Lange E., Dorward L., Hoyte S., Marino A., et al. (2020). Ethical Considerations When Conservation Research Involves People. Conserv. Biol. 34, 925–933. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13464.This

Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis (London: Sage Publications).

Corbin J. M., Strauss A. (1990). Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria. Qual. sociology. 13, 3–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00988593

Crespin S. J., Simonetti J. A. (2019). Reconciling Farming and Wild Nature: Integrating Human–Wildlife Coexistence Into the Land-Sharing and Land-Sparing Framework. Ambio 48, 131–138. doi: 10.1007/s13280-018-1059-2

Dickman J. A. (2008) Key Determinants of Conflict Between People and Wildlife, Particularly Large Carnivores, Around Ruaha National Park, Tanzania. Available at: http://re.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/KEY DETERMINANTS OF CONFLICT.pdf (Accessed October 19, 2018).

Durant S. M., Mitchell N., Groom R., Pettorelli N., Ipavec A., Jacobson A. P., et al. (2017). The Global Decline of Cheetah Acinonyx Jubatus and What it Means for Conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United. States America 114, 528–533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611122114

Eklund A., Johansson M., Flykt A., Andrén H., Frank J. (2020). Drivers of Intervention Use to Protect Domestic Animals From Large Carnivore Attacks. Hum. Dimensions. Wildlife. 25, 339–354. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2020.1731633

Eklund A., López-Bao J. V., Tourani M., Chapron G., Frank J. (2017). Limited Evidence on the Effectiveness of Interventions to Reduce Livestock Predation by Large Carnivores. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02323-w

Findlay L. (2016) Human-Primate Conflict: An Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Wildlife Crop Raiding on Commercial Crop Farms in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Available at: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk.

Fischer J., Abson D. J., Butsic V., Chappell M. J., Ekroos J., Hanspach J., et al. (2014). Land Sparing Versus Land Sharing: Moving Forward. Conserv. Lett. 7, 149–157. doi: 10.1111/conl.12084

Frank B. (2016). Human–wildlife Conflicts and the Need to Include Tolerance and Coexistence: An Introductory Comment. Soc. Natural Resour. 29, 738–743. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2015.1103388

Frank B., Glikman J. A., Marchini S. (2019). “Human–wildlife Interactions: Turning Conflict Into Coexistence,” in People and Wildlife: Conflict or Coexistence? Eds. Woodroffe R., Thirgood S., Rabinowitz A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).