- Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, School of Social Sciences, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Introduction: Despite growing environmental awareness and the efforts of a variety of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) to influence the wildlife protection policy agenda, wildlife laws remain outside the remit of mainstream criminal justice. Adopting a green criminological perspective, this article considers wildlife crime in respect of threats to UK marine wildlife. It examines the UK’s legal and enforcement framework and the scope and nature of both marine wildlife crime and harms to marine wildlife. Its core question is to consider the extent to which the UK’s wildlife law approach provides for effective wildlife protection and is adequate to deal with the threats facing marine wildlife.

Methods: The research is a mixed methods study that considers the relevant law, case law and reporting of wildlife crimes as well as the enforcement approach to marine wildlife crime. The article’s methodological approach is socio-legal in nature commencing with a review of the relevant literature on threats to marine wildlife and incorporating analysis of the current law and case law available via the legal databases BAILII and Westlaw. The study also conducted an analysis of licences for disturbance of marine wildlife via an examination of the open access case management database managed by the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) the main enforcement body for marine wildlife incidents in the UK.

Results: The research identifies that while in principle the UK has robust legal protection for marine wildlife, in practice, policy allows exploitation and disturbance of marine wildlife that causes harm to individual animals and is detrimental to efforts to conserve marine wildlife and marine ecosystems.

Discussion: This research concludes that in the UK, potentially strong legislation existing on paper is arguably not backed by an effective enforcement regime. The remote nature of marine wildlife incidents, competition between marine wildlife and leisure and commercial activities and the very wording of legislation all create enforcement challenges. This article argues for marine wildlife crime to be integrated into mainstream crime policy linked to other forms of offending and criminal justice policy, rather than being largely seen as a purely environmental issue and a ‘fringe’ area of policing.

1 Introduction

Despite growing environmental awareness and the efforts of a variety of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) to influence the wildlife protection policy agenda, wildlife laws remain outside the remit of mainstream criminal justice. Wildlife law enforcement is often a fringe area of policing whose public policy and enforcement response exists within a policy and legislative framework that seeks to provide for wildlife protection whilst simultaneously allowing the exploitation of wildlife (Nurse, 2013). The urban-centric focus of criminology is evident in respect of environmental and wildlife crimes, which have received relatively little focus in mainstream criminology (Nurse, 2015; Nurse and Wyatt, 2020). However, given the threat to the planet’s biodiversity and wide-scale harms that result from wildlife crimes, green criminology argues for wildlife crime as an important area of criminological inquiry (Potter et al., 2016). In particular, green criminological inquiry into wildlife crime identifies that ‘wildlife-related crime and harm are significant issues within crime and justice discourse, and there is often a link between wildlife crimes and other offending’ (Nurse and Wyatt, 2020: 3). In addition, wildlife is an important part of ecosystems and wildlife crime discourse often identifies the importance of wildlife harms to other aspects of environmental protection. In this respect, green criminology identifies the importance of environmental protection laws to wider harms of greater significance than much mainstream crime such as street crimes (Lynch and Stretesky, 2014).

This article considers a distinct aspect of wildlife crime; namely harms against marine wildlife. Its core analysis concerns the legal protection provided to marine wildlife and gaps in that protection within the UK’s legislative framework. In principle marine wildlife is protected within the UK’s legal framework and by virtue of the UK’s implementation of European law. Yet NGO’s have argued that marine wildlife, particularly cetaceans continue to suffer from disturbance and persecution that raises questions about the adequacy of legal protection (Green et al., 2012). The analysis carried out for this study identified that while a general framework of marine mammal protection exists, contemporary UK legislation is incomplete in respect of providing fully effective marine mammal welfare protection. A number of core issues were identified relating to the inadequacy of legislation; inconsistency of legislation; inadequacy in enforcement; and incoherence and application of penalties.

2 The current study

This study examines issues relating to the enforcement of wildlife laws including investigation and prosecution of marine wildlife crimes and harms in the UK. It considers the adequacy of the legal framework for the investigation of offences committed against UK marine wildlife as well as providing for a critical analysis of enforcement issues through literature and case analysis. From the outset it should be made clear that while the discussion of marine wildlife crimes has its initial focus on analysis of acts defined as crimes, the article also considers the wider issue of harms consistent with green criminology’s consideration of negative impacts on the environment and non-human nature that contravene legislation but may not be defined as crimes (White and Heckenberg, 2014: 8). Accordingly, what matters is the harm caused to marine wildlife in contravention of the aims of wildlife protection legislation, irrespective of whether that harm was a crime, an administrative permit breach, or a contravention of regulatory control.

Wildlife crime can be broadly defined as the illegal exploitation of wildlife species, including poaching (i.e. illegal hunting, fishing, killing or capturing), abuse and/or trafficking of wild animal species. In UK law, wildlife is generally defined as any non-domesticated non-human animals. For example, the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, the primary law protecting wildlife in Britain, defines wildlife according to criteria that specifies wildlife as animals living ‘naturally’ in a wild state and excludes animals bred in captivity.1 Separate legislation (e.g. the Animal Welfare Act 2006) protects companion animals living under human control.2345 However, it should be noted that legislative definitions of wildlife vary across jurisdictions and in academic discourse such that some definitions would exclude fish and other definitions define wildlife as including fauna and flora (see later discussion of CITES and UK endangered species legislation). UK wildlife law provides for general protection of wildlife, subject to a range of permissible actions that allow wildlife to be killed or taken for conservation management purposes (e.g. culling to maintain herd health or to conserve other wildlife), killing for legal (and regulated) sporting interests (e.g. shooting and fishing), or to protect farming or other commercial interests (e.g. the killing of so-called ‘pest’ species). However, wildlife laws often contain prohibited methods of killing or taking wildlife such as prohibitions on using snares, poison or taking or harming or disturbing wildlife during the breeding season. Accordingly, wildlife law creates a range of offences whilst arguably allowing continued exploitation of wildlife.

Thus, for an act to be a wildlife crime, it must be something that is proscribed by legislation; an act committed against or involving wildlife, e.g. wild birds, reptiles, fish, mammals, plants or trees which form part of a country’s natural environment or be of a species which are visitors in a wild state; and involve an offender (individual, corporate or state) who commits the unlawful act or is otherwise in breach of obligations towards wildlife. (Nurse and Wyatt, 2020: 7). Arguably a wildlife crime must also be subject to some form of criminal sanction such as a fine or prison sentence which is designed primarily as a punitive measure, embodying principles of retributive justice (Nurse, 2011; Öberg, 2013).

These elements clarify that wildlife crime is a social construction as it relates to violation of existing laws. Accordingly, laws can be changed, which can reconfigure what is considered to be a crime according to contemporary conceptions. For the purposes of this paper’s discussion, marine wildlife is defined as flora and fauna that live in the salt water of the sea or ocean, or the brackish water of coastal estuaries.

2.1 Threats to marine wildlife

Previous research has identified that ‘the seas around the UK are under pressure as never before including through the drives for major offshore development of marine renewables and offshore oil and gas resources, along with increasing pressure from leisure and tourism, boats, whale-watching, recreational fishing and the continued mismanagement of our fisheries’ (Green et al., 2012:5). IPBES (2019) indicate that globally approximately 33% of marine mammals are at risk of extinction and that threats facing marine wildlife include pollution, climate change and human interference. More recently, scientists at Arizona State University estimated that about 44,000 turtles across 65 countries were illegally killed and exploited every year over the past decade, resulting in the deaths of more than 1.1 million sea turtles illegally killed in the past 30 years (Quaglia, 2022). This aspect of marine wildlife exploitation is firmly linked to consumer demand for marine wildlife products that can be linked to a variety of consumer demand perspectives (Veríssimo et al., 2020; Pheasey et al., 2021). Trade in marine wildlife species would be regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in respect of those species threatened by trade (Wyatt, 2013). CITES effectively bans trade in species that are threatened by trade and creates a regulatory framework that in principle provides for sanctions for illegal wildlife trade and trafficking. Accordingly, certain marine wildlife are subject to illegal exploitation to satisfy human demand, despite the protection afforded by wildlife legislation. For example, UNODC’s World Wildlife Crime Report for 2020 identifies that turtles are illegally trafficked to fulfil consumer demand and that ‘some turtle and tortoise species are valuable enough to air courier, making use of carry-on or checked luggage’ (UNODC, 2020: 75). In addition, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing along with social and economic impacts, ‘directly threatens imperiled marine wildlife, such as sea turtles’ (Miller et al., 2019: 1). Thus, the illegal trade in marine wildlife and derivative products exists alongside the legal trade and represents a potential threat to the sustainability of some species.

Separate from the threats caused by direct illegal activity, marine wildlife are subject to threats from legal, permitted activity such as development of the marine environment for wind farms and oil and gas extraction activity (Bergström et al., 2014). Marine wildlife also suffers disturbance caused by leisure and commercial activities. In the UK concerns have been raised about the health and status of a range of UK marine species, including the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus). These species are considered to experience disturbance and harassment from increasing inshore leisure traffic, public activities that cause disturbance such as marine tourism which impacts negatively on wildlife and development of the marine environment (Kelly et al., 2004).

3 Material and methods

This study’s focus on the content and focus of wildlife law is socio-legal in nature, extending beyond a doctrinal analysis of law and case law to also consider the social context of marine wildlife protection (Harris, 2013). The study commenced with analysis of the literature on threats to marine wildlife and relevant green criminological and law literature on wildlife crime, the protection of marine wildlife and contemporary issues in protection of marine ecosystems. Accordingly, the research approach was to consider the current legal landscape for marine protection in the UK and internationally, together with environmental law discourse on the adequacy of contemporary wildlife law. This included analysis of the current law, debates on law reform and critiques of wildlife law provided by NGOs and environmental policy professionals.

To assess elements of current legal analysis this study’s analysis of law and marine wildlife protection made use of socio-legal methodologies to consider the content of law and relevant case law. To identify suitable materials, searches were conducted on the legal databases BAILII6 and Westlaw using ‘marine wildlife’ as a key search term, followed by ‘marine’ ‘dolphin’ ‘porpoise’ ‘seabird’ and ‘whale’ for triangulation and to ensure that no relevant cases were missed. The resultant cases were then subject to content analysis identifying the relevant legislation, species involved and the legal issues at the heart of each case to determine their relevance for this paper’s analysis. Cases that did not involve marine wildlife protection issues (including wider wildlife protection concerns) were discarded. Cases that met the criteria were subject to a detailed analysis. For example, the keyword ‘marine’ returned 22,851 results in Westlaw, whereas the term “marine wildlife” had returned 16 cases in Westlaw and 10 cases in BAILII. Initial sifting of the Westlaw cases identified many that contained the word ‘marine’ but that fell outside of the terms of the research as they included, for example, a substantial number of marine insurance cases, planning permission claims not related to marine wildlife and other ancillary issues such as contract disputes and arbitration decisions.

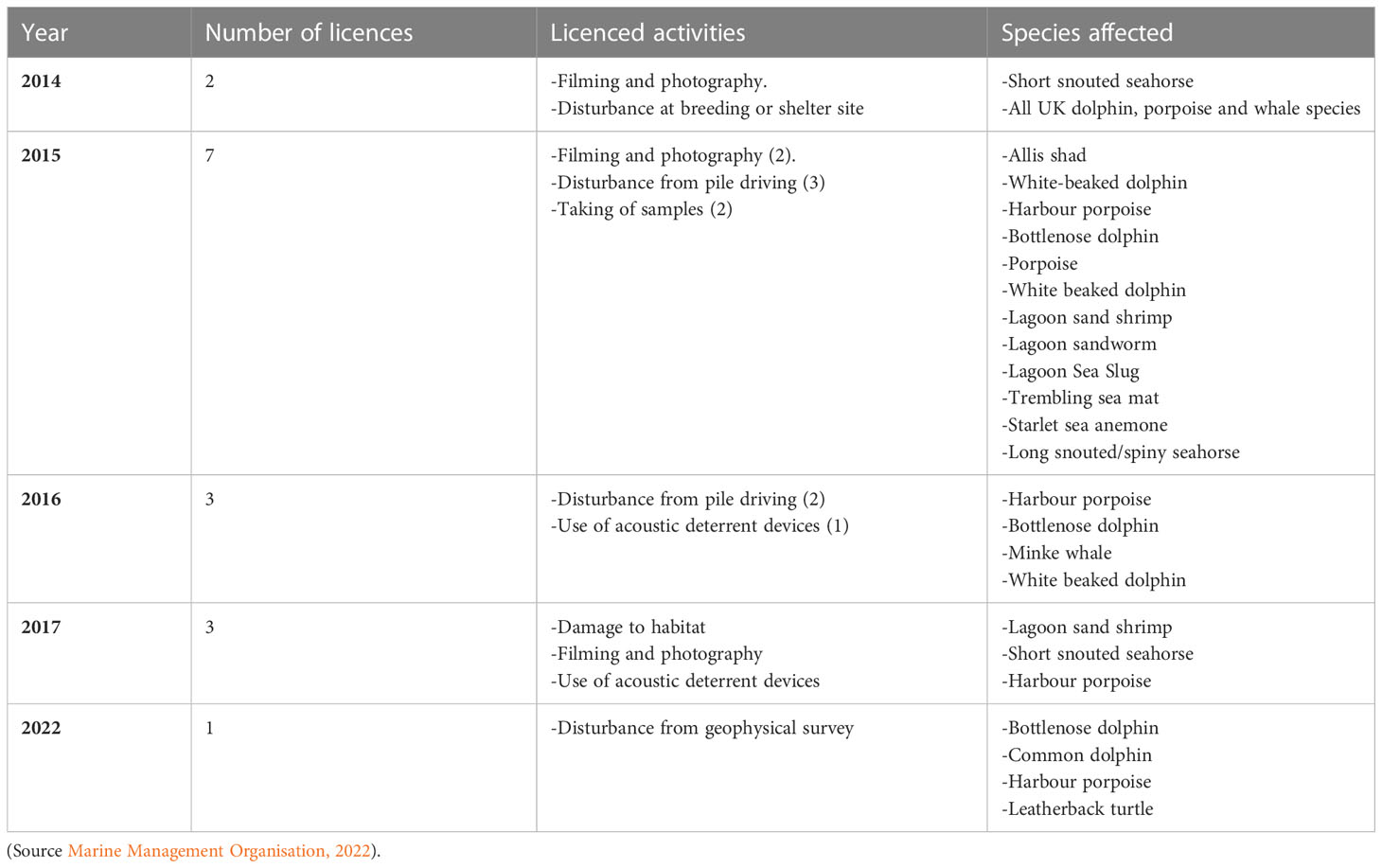

The study also conducted analysis of relevant licences granted for disturbance of marine wildlife and the marine environment by the Marine Management Organisation (MMO). The MMO is the main enforcement body for marine wildlife incidents in the UK. The MMO licences and regulates marine activities in the UK and is, for example, responsible for managing and monitoring fishing fleet sizes and quotas for catches, ensuring compliance with fisheries regulations, such as fishing vessel licences, time at sea and quotas for fish and seafood, dealing with pollution incidents and with illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing. The MMO’s open access case management database provides details of licences granted for regulated activities such as the taking of otherwise protected wildlife for scientific purposes, licences for development that will cause disturbance to marine wildlife such as pile driving and seismic disturbance activities in the construction and development of wind farms, and use of acoustic deterrence devices during clearance or other works. Analysis of licences as part of this study, identified the nature and scope of permitted activities and clarified the nature of some of the impacts on marine wildlife from development and other regulated activities.

4 Results

Overall, UK marine wildlife is protected by means of a range of international law, EU and UK law.7 Most jurisdictions now have laws that make animal abuse an offence and provide for general wildlife and companion animal protection; albeit some variation exists in how offences are framed. At a basic level, laws generally provide protection for companion animals in the form of anti-cruelty statutes that govern the relationship between humans and their non-human animal companions. As a minimum, these statutes prohibit the deliberate, intentional, and arbitrary inflicting of pain. In respect of livestock and animals that are exploited for human consumption in the food industry, animal welfare laws provide a regulatory function, ensuring or attempting to ensure that animals are reared and slaughtered in a humane manner and that the suffering experienced by animals is minimised so far as is possible. In respect of wildlife, laws provide for the conservation, management, protection, and prohibition on certain methods of killing wildlife (Vincent, 2014; Nurse, 2015). But arguably wildlife living outside of human control is protected less than non-human companions and is protected only so far as the interests of wildlife coincide with human interests (Schaffner, 2011; Ryland and Nurse, 2013; Nurse and Wyatt, 2020). An underlying principle is that wildlife is arguably defined as a natural resource available for human exploitation but should be protected from actions that threaten sustainability of wildlife populations. Individual wildlife laws also create specific offences in respect of prohibited methods of taking or killing wildlife and against intentional disturbance of wildlife. In addition, in some circumstances, animal welfare legislation will apply to marine wildlife although arguably this is restricted to circumstances where it comes under human control or in respect of the welfare considerations on humane killing of wildlife intended to prevent unnecessary suffering. This would apply in respect of activities where the killing of wildlife is deemed necessary such as killing of wildlife for scientific analysis.

In respect of marine wildlife, the EU Habitats Directive offers ‘strict’ protection to all cetaceans under Article 12 and is transposed through Conservation Regulations in each of the UK’s devolved administrations (Green et al., 2012). In Scotland, the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 protects individual marine mammals from disturbance while further protection is afforded to any wild animal of a European Protected Species (including all cetaceans), under the Conservation (Natural Habitats etc.) Amendment (Scotland) Regulations 2004. The Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 also makes it an offence to kill, injure or take a live seal, except under license. In England and Wales, the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulation 2007 make it an offence to deliberately capture, kill, disturb, or trade in the animals listed in Schedule 2 (which includes all dolphins, whales and porpoises) except under license, reflecting the reality of protection for marine wildlife except where human interests may conflict. Thus, in principle, any interference with or harm caused to marine wildlife is regulated and monitored. The Wild Mammals (Protection) Act 1996 contains provisions for the protection of wild mammals from certain cruel acts. If a person mutilates, kicks, beats, nails or otherwise impales, stabs, burns, stones, crushes, drowns, drags or asphyxiates any wild mammal with intent to inflict unnecessary suffering he shall be guilty of an offence.

The Fisheries Act 2020 has also been implemented as a consequence of the UK leaving the European Union. The Act’s introductory text describes it as ‘an Act to make provision in relation to fisheries, fishing, aquaculture and marine conservation; to make provision about the functions of the Marine Management Organisation’ (Fisheries Act 2020). The Act sets out eight fisheries objectives several of which are relevant to this article’s discussion namely: the sustainability objective; the precautionary objective; the ecosystem objective; the scientific evidence objective and the bycatch objective. Taken together, these objectives set out the principle of a sustainable approach to fisheries based on the principle that the fishing capacity of fleets is such that fleets are economically viable but do not overexploit marine stocks and fish and aquaculture activities are managed using an ecosystem-based approach so as to ensure that their negative impacts on marine ecosystems are minimised (or indeed where possible, reversed). This also means that incidental catches of sensitive species are minimised and, where possible, eliminated and bycatch should also be eliminated.

Separate from the hard law elements of UK legislation, the ‘soft law’ elements of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are also relevant to the protection of marine wildlife (Pinn, 2016). MPAs are protection areas defined by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) as parts of intertidal or subtidal environments, together with their overlying waters, flora and fauna and other features, that have been reserved and protected by law or other effective means. MPAs are ‘spatially-delimited areas of the marine environment that are managed, at least in part, for conservation of biodiversity’ but they can be declared for a variety of reasons and thus the specific goals and protection of each MPA need to be carefully defined (Edgar et al., 2007: 533). Data from the JNCC indicates that there are 374 MPAs in UK waters covering 338,545 km2 and 38% of all UK waters (JNCC, 2022). -Voluntary codes for marine wildlife watching are also in place in different parts of the UK in order to minimize the harm caused to marine wildlife by this activity, primarily through disturbance.

4.1 Legislative issues

The Law Commission (the body responsible for reviewing UK law) considered that several species protected by the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats are not (adequately) protected under UK domestic law (Law Commission, 2015: 60). In particular, the Commission considered potential gaps in the protection of marine wildlife, in the extent of wildlife protection and consistency in wildlife protection. In addition, inadequacies in the legal definition of disturbance and in the application of animal welfare legislation such as the Animal Welfare Act 2006 to marine wildlife protection were considered. Analysis for this research confirmed that several issues identified by the Law Commission had not yet been resolved and that gaps in marine wildlife protection remain in force.

A significant gap in legislation and its practical enforcement relates to welfare concerns. While legislation creates offences in relation to intentional acts and specifically prohibited acts that impact negatively on marine wildlife it is largely silent in respect of welfare considerations. Disturbance is one of the most prevalent forms of harm caused to marine wildlife (discussed further later in this article) but the offence as constituted in most legislation relates to the ‘act’ of disturbance rather than the nature and duration of that disturbance such that consideration of causing ‘unnecessary suffering’ through a disturbance act could come into play. In principle the welfare considerations of the UK’s Animal Welfare Act 2006 (and its associated devolved legislation) come into play in the specific circumstances in which marine wildlife come under direct human control. The Act applies to vertebrate animals and it’s definition of a ‘protected animal’ (an animal covered by the Act’s provisions) relates to: a) an animal of a kind which is commonly domesticated in the British Islands; (b) an animal under the control of man whether on a permanent or temporary basis, or (c) an animal not living in a wild state. Thus, marine wildlife that are being handled for the purposes of collecting samples or scientific monitoring, those that are caught accidentally as part of fisheries or other operations and thus temporarily under the control of man and marine wildlife brought into a captive environment (e.g. fish farms in coastal waters) are arguably owed a duty of animal welfare in accordance with animal welfare provisions. However, the evidence analysed as part of this research did not reveal any evidence of animal welfare act prosecutions for marine wildlife welfare offences despite the fact that harbour porpoise bycatch arguably represents a significant welfare problem with Northridge et al. (2018) estimating UK porpoise bycatch in 2017 to be between 587 and 2615 individuals with a best estimate of 1098. The discussion of disturbance licences later in this analysis also identifies that welfare considerations are somewhat minimised in the granting of licences for development and disturbance.

4.2 Enforcement framework

Enforcement of wildlife crime in the UK is the responsibility of the police and other specialist agencies. The MMO is the main enforcement body for marine wildlife incidents in the UK, while criminal matters remain the responsibility of the police, questions have been raised about the extent to which wildlife is a policing priority. In evidence to the 2012 environment select committee, the representative of the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO, then the representative body for senior police leaders) commented:

In 2004 the point was made that Chief Constables undoubtedly have sufficient resources with which to combat wildlife crime but there were few indications from government that this was an area to which resources needed to be applied. The situation today is exactly as it was in 2004 in that there remains little encouragement from government to direct resources to wildlife crime.

(House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, 2012: 61)

Thus, Chief Police Officers acknowledged that wildlife crime was not identified by the justice ministry as being a core policing priority. Accordingly, it remained largely down to individual Chief Officers to determine its importance and the priority afforded to wildlife crime resources within their force area. However, it should be noted that a National Police Wildlife Crime Unit (NWCU) does exist in the UK to provide support for police wildlife crime activity. In its Wildlife Crime Policing Strategy for 2018-2021, the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC, 2018)8 identified the operational wildlife priorities as being: badger persecution; bat persecution; CITES; freshwater pearl mussels; raptor persecution; and poaching (NPCC, 2018: 7). In respect of marine wildlife crime, the NPCC identified that ‘concern is growing daily about levels of disturbance to protected marine life all around our coasts. As marine ecotourism is a well-established and still fast-growing tourism activity, the potential to cause wildlife harm is growing too’ (NPCC, 2018: 3).

The MMO licences and regulates marine activities in the UK and is, for example, responsible for managing and monitoring fishing fleet sizes and quotas for catches, ensuring compliance with fisheries regulations, such as fishing vessel licences, time at sea and quotas for fish and seafood, dealing with pollution incidents and with illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing.

Available data shows that in 2019-20 there were 196 offences relating to wildlife recorded by the police in Scotland, an increase of 13% (171 recorded offences) in comparison with 2018-19 (Scottish Government, 2022: 8). The data identifies 27 fish poaching incidents recorded by Police Scotland (Scottish Government, 2022: 9). There were no CITES-related offence recorded by Police Scotland in 2019-20. Figures from Wildlife and Countryside Link, identifies that in 2020 there were 477 reported incidents related to sea fisheries, nets boats and cockling in England and Wales, these related to 469 confirmed cases of criminal offences and 45 defendants convicted (Wildlife and Countryside Link, 2021: 15). Evidence of marine mammal disturbance incidents provided by Cornwall Marine Coastal Code Group indicate that there were 193 disturbance incidents in 2019 and 366 incidents in 2020. The data suggests that these related to 90 probable cases of criminal offending in 2019 and 33 cases in 2020. However, these resulted in only six cases being referred to police in 2019 and one in 2020 (Wildlife and Countryside Link, 2021: 31). In addition, ‘despite the UK’s compliance with its obligations under EU regulations in relation to harbour porpoise bycatch in gillnets, annual estimates of bycaught animals remain high’ (Calderan and Leaper, 2019: 50). It is also considered that ‘EU monitoring and mitigation requirements as they currently stand are insufficient to provide either the necessary observer coverage or the type and level of mitigation needed to effect a substantial reduction in porpoise bycatch’ (ibid.).

4.3 Case law

Analysis of case law databases identified eight cases relevant to this article’s discussion of marine wildlife protection since the year 2000. Cases involved a range of legislation, namely the Sea Fish (Conservation) Act 1967; the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981; Directive 92/43 (the Habitats Directive), the Electricity Act 1989 section 36 and Marine Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2007, the Marine and Coastal Act 2009 and tort action.9 Four of these cases involved judicial review of decisions to allow development and activity that it was claimed would adversely affect the marine environment and marine wildlife. Three of these cases were brought by NGOs. R. (on the application of Greenpeace Ltd) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs [2005] EWCA Civ 1656 was an appeal against dismissal of an application for judicial review ([2005] EWHC 2144) of the secretary of state’s decision to make the Southwest Territorial Waters (Prohibition of Pair Trawling) Order 2004. The appeal was dismissed, and the court concluded that the Order had been lawfully made under the Sea Fish (Conservation) Act 1967 s.5A despite the lack of a scientific basis for the order. In 2014 in RSPB v Secretary of State [2014] EWHC 1645 (Admin) judicial review was sought on a decision by the secretary of state which would have allowed the defence and aerospace company BAE (BAE Systems [Operations] Ltd. also referred to as British Aerospace) to cull 552 pairs of lesser black-backed gulls (seabird). The court concluded that the Secretary of State was entitled to make the decision and had carefully and rationally assessed the numbers which could be safely culled without impairing the long-term viability of the gulls on the site. In 2016 the RSPB sought judicial review of two decisions by Government ministers to grant consent for the construction of the Neart na Gaoithe Offshore Wind Farm. The RSPB’s claims were upheld and the court concluded that the environmental information in the case was considered inadequate to meet the threshold of appropriate assessment of environmental impacts. However, this decision was overturned in 2017 and the wind farm development was allowed to commence (BBC News, 2017).

Elsewhere, case law identifies failures in the UK’s legal framework for marine wildlife protection. In 2018, the European Commission brought legal action against the UK alleging that the UK had failed to fulfil its obligations under the Habitats Directive (art.3(2), art.4(1) and Annexes II and III) by failing to designate sufficient sites for the protection of the harbour porpoise. The court upheld the Commission’s claim and confirmed that the United Kingdom had failed in its obligations. The UK later proposed to designate six new sites for harbour porpoise protection. Subsequently, in June 2020 the Benyon review into marine protection recommended the introduction of Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) to complement the existing MPA network, enabling greater recovery of the marine ecosystem. HPMAs adopt a policy of strict protection of the marine environment with a presumption against any activity involving extraction, destruction or deposition being permitted in those areas and strict protections on other damaging activities. HPMAs have potential benefits to marine wildlife in adjacent MPAs and the Benyon Review recommended that the UK Government should pilot around five HPMAs with a recommendation that some or all of the pilot sites could be co-located with existing Marine Protected Areas such as Marine Conservation Zones, in effect to upgrade the status of some of those sites (Benyon, 2020). The Government in its response to the Benyon Review accepted the recommendation and confirmed that it would begin introducing HPMAs by identifying a number of locations within English waters with which to pilot HPMAs and its approach to this enhanced level of marine protection (UK Parliament, 2021).

In 2019 in Thomson v Marine Management Organisation [2019] EWHC 2368 (Admin) judicial review was sought over a failure to consider attributes of important habitats for seabed flora and fauna before granting a dredging licence. This application was dismissed in part because the court disagreed with the claimant on the weight to be given to the JNCC guidance on environmental matters. In essence the court highlighted the reality that environmental concerns do not always outweigh other factors in considering licences.

Overall, this brief analysis of case law identifies that in some respects the UK has failed in its compliance with European legislation, particularly in respect of protection for the harbour porpoise. But it also identifies the extent to which the courts may adopt a restrictive approach in respect of the weight attached to environmental and wildlife protection when weighed against commercial interests. The bar appears to be set high for environmental and wildlife issues to take priority over commercial concerns and development.

4.4 Licences

Analysis of granted licences for marine disturbance was carried out as part of this study and identified a total of 16 relevant licences granted in the last 10 years. Two licences were granted in 2014, seven in 2015, three in 2016, three in 2017 and one in March 2022. Table 1 provides an overview of the licences granted and this article’s analysis shows that various purposes were identified in license applications including: filming and photography that might cause disturbance to marine wildlife, taking of samples for monitoring purposes, damage to habitats used by marine wildlife for shelter or protection, taking of marine wildlife for scientific purposes and geophysical surveys. Licence applications indicate the maximum number of wildlife that may be affected by a licence where the licences involve specific activity that potentially has significance impact on marine wildlife. This may be the case where the licenced activity may be of a protracted nature, such as seismic disturbance caused by pile driving activities over several months. Where numbers are specified, potentially the impact of the licences issued during the study period provides for disturbance of 23 leatherback turtles, 16 minke whales, 1,554 harbour porpoises, 50 white beaked- dolphins. These are indicative maximum numbers with the potential impact being higher, for example one licence involving use of acoustic deterrent devices indicated that a maximum of 1,446 harbour porpoises would be affected in any 24-hour period for a licence that would run for three months.

These figures indicate that considerable disturbance could be caused to marine wildlife over the period by licenced and authorized activity.

5 Discussion

As this paper identifies, while wildlife legislation provides for broad protection of marine wildlife, there remain some issues within the UK’s regime in respect of: the extent of legislative protection; consistency with international law provisions; loopholes or inconsistency in legislation; and the extent to which legislation is effectively enforced. Case law and legislative analysis identifies that the UK has previously failed in its compliance with European legislation, particularly in respect of protection for the harbour porpoise. But it also identifies that in situations where environmental impacts and commercial interests are in conflict, the weighting attached to these competing interests creates a high hurdle for environmental and wildlife protection interests to overcome.

International perspectives allow continued use and exploitation of animals with the proviso that such use should be sustainable. Even where this does result in animal killing or harm, there is a general presumption in law that any suffering or disturbance to wildlife should be the minimum necessary in respect of the permissible act. But this also means that there are variations in the level of suffering, pain or disturbance considered legally permissible in different practices that may impact negatively on animals. In the marine environment, this includes disturbance of marine wildlife as part of permitted development.

The evidence of UK marine wildlife protection is that disturbance of marine wildlife remains a significant problem. Not just in respect of disturbance linked to leisure activities that can potentially give rise to offences under legislation but also where ‘soft law’ measures such as the Marine Wildlife Watching Code may be deployed to minimise the harm to marine wildlife from tourism and wildlife watching activities. Evidence also indicates that despite the protection afforded by international and national law, disturbance caused by commercial activities causes considerable inconvenience and possible harm to marine wildlife. In this regard, licenced activity pits the interests of commercial activity against the interests of marine wildlife protection with the anthropocentric perspective often winning out. Where this is the case, minimising harm and disturbance should be a priority and indeed, guidance from the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) requires that ‘the operator is expected to make every possible effort to design a survey that minimises the sound generated and the likely impacts to marine mammals’ (JNCC, 2017: 4). Yet analysis of the licences granted and of case law shows that ‘every possible effort’ is a low threshold to meet seemingly requiring that operators make some effort but clearly not that disturbance and harm be eliminated. Thus, within the confines of the law, significant disturbance can be permitted, and an enforcement challenge exists in establishing that action (or lack of action) taken by operators causing disturbance is either inadequate, or clearly represents a contravention of the law.

The preliminary analysis of this article identifies that while international law mechanisms such as the EU Habitats Directive and the Bern Convention provide for broad protection of wildlife and set basic standards of legal protection, the wording of legislation and its interpretation create difficulties. In particular, legislation creates offences in respect of deliberate killing, disturbance or the destruction of these species or their habitat. However, potentially limiting protection to deliberate killing requires further examination of how legislation deals with accidental or negligent killing of wildlife or harm caused by omission.

The evidence suggests that marine wildlife crimes and harms are not infrequent in the UK, based on figures from Wildlife and Countryside Link and other monitoring bodies. These show evidence of 477 reported marine incidents (related to sea fisheries) in 2020, linked to 469 criminal offences and figures specifically for disturbance incidents also identified 90 probable criminal cases in 2019 and 33 in 2020. Yet the data on prosecution numbers provided in the Scottish Wildlife Crime Report and in Wildlife and Countryside Link data (referred to earlier in this article) indicate a relatively low level of prosecution for the sea fisheries cases as well as a low level of disturbance cases being reported to the police, again indicating limited prosecution activity for marine wildlife cases. For example, in 2018, 2019 and 2020 there were 73, 90, and 33, probable cases of criminal offending in respect of marine disturbance in Cornwall alone. But only 3, 6 and 1 cases respectively were referred to the police. This indicates that even where criminal activity is being carried out, formal enforcement activity is limited and in respect of marine mammals, Wildlife and Countryside Link report that ‘reported cases rarely lead to prosecution’ (Wildlife and Countryside Link, 2021: 31). The estimated numbers of bycatch indicate ‘many thousands of cetaceans are bycaught in fishing gear in European waters’ and that marine wildlife are still being harmed through ‘accidental’ catching activity, something that NGOs and other monitoring bodies have identified as a problem for some time and that causes significant welfare issues (Dolman and Brakes, 2018: 1).

This article concludes that in the UK, potentially strong legislation on paper is arguably not backed by an effective enforcement regime. As with other areas of wildlife crime, the remote nature of marine wildlife crimes hampers both reporting and enforcement of crimes. First, reporting relies on witnesses understanding that what they are viewing is a crime and in the case of tourism and leisure activities, the legal nature of the activity may mask the extent to which lay persons viewing activity fully understand that what is being witnessed is a crime. Secondly, the remote nature of many offences occurring in the marine environment, like many rural crimes, means that they may not be witnessed in a manner that is consistent with speedy reporting to enforcement authorities. Finally, the marine environment arguably creates challenges in securing reliable evidence on which to bring prosecution or other enforcement, notwithstanding previously mentioned issues with witness evidence. The wording of legislation itself which relies on proving ‘intent’ to commit an offence is also problematic.

Preventing marine wildlife crime is both an enforcement issue linked to how best to secure effective enforcement of existing legislation, and a policy issue that raises questions about the circumstances in which harm caused to protected marine wildlife becomes permissible. In practice, policy allows exploitation and disturbance of marine wildlife that causes harm to individual animals and is detrimental to efforts to conserve marine wildlife and marine ecosystems. But a green criminological perspective would argue that preventing harms to the environment and non-human nature should be a policy imperative and that the focus of enforcement and justice system action should incorporate both a precautionary principle approach and a polluter pays one. Accordingly, this article argues for marine wildlife crime to be integrated into mainstream crime policy linked to other forms of offending and criminal justice policy, rather than being largely seen as a purely environmental issue and a ‘fringe’ area of policing. To achieve this, wildlife crime arguably needs to be made a notifiable offence in the UK, so that it becomes something that mainstream policing agencies are required to record and consider as a policing priority. In addition, lack of resources and adequate training need to be addressed, including a concern that ‘prosecutorial capacity is hampered by a lack of dedicated resources, training, and limitations brought about by the legislative framework’ (UNODC, 2021: 17). Improving marine wildlife crime enforcement and preventing harms to marine wildlife requires addressing these issues so that the strong regime that in principle exists within legislation is intreated into a system that sees wildlife harms as not just a regulatory issue but a criminal justice issue to be considered alongside other crimes and supported by an effective environmental protection policy.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. data can be found here: https://marinelicensing.marinemanagement.org.uk/.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The author declares that this research was conducted within the author’s allocated institutional research time and in the absence of any direct external funding for the work.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the support of colleagues from Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) who provided a copy of a seismic (disturbance) license and commented on the adequacy of its animal welfare consideration within the license conditions. Thanks also to Elliot Doornbos for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ For example, the guidance in the Act states that the definition of ‘wild bird’ in section 27(1) is to be read as not including any bird which is shown to have been bred in captivity unless it has been lawfully released into the wild as part of a re-population or re-introduction programme. Accordingly, the definition of marine wildlife employed in this article would not include farmed species of marine wildlife (e.g. farmed salmon) but would extend towards crimes committed against wild salmon.

- ^ There is country-specific legislation in Scotland and Northern Ireland; the Animal Health & Welfare

- ^ (Scotland) Act 2006 and the Welfare of Animals Act (Northern Ireland) 2011. The three Animal Welfare Acts

- ^ have similar aims of preventing harm and promoting animal welfare although there are some differences in the

- ^ respective Acts.

- ^ British and Irish Legal Information Institute, an online searchable database of British law and related case law.

- ^ Following its ‘Brexit’ departure from the European Union, the UK reconfigured its environmental and wildlife protection laws with the aim of integrating the previous EU into UK law, albeit with some exceptions and variation.

- ^ The NPCC is the successor organisation to the ACPO

- ^ It should be noted that the reported case law does not represent all prosecuted cases, some of which may not be clearly identified or reported as marine wildlife cases or indeed may not be reported at all. It should also be noted that wildlife offences in the UK are not notifiable and so are not distinguished as wildlife cases in police and official crime statistics. Instead, they are included in the category of ‘other notifiable offences’ which makes it difficult to clearly determine how many wildlife cases take place each year (Nurse and Harding, 2022).

References

BBC News. (2017) Judge overturns firth of forth and firth of Tay wind farms block. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-39934095 (Accessed 30 August 2022).

Benyon R. (2020) Benyon review into highly protected marine areas: Final report. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/890484/hpma-review-final-report.pdf (Accessed 15 August 2022).

Bergström L., Kautsky L., Malm T., Rosenberg R., Wahlberg M., Capetillo N. A., et al. (2014). Effects of offshore wind farms on marine wildlife–a generalized impact assessment. Environ. Res. Lett. 9 (3), 1–12. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/9/3/034012

Calderan S., Leaper R. R. (2019). Review of harbour porpoise bycatch in UK waters and recommendations for management (WWF UK). Available at: https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-04/Review_of_harbour_porpoise_in_UK_waters_2019.pdf (Accessed 20 August 2022).

Dolman S. J., Brakes P. (2018). Sustainable fisheries management and the welfare of bycaught and entangled cetaceans. Front. Vet Sci. 5. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00287

Edgar G. J., Russ G. R., Babcock R. C. (2007). “Marine protected areas,” in Marine ecology. Eds. Connell S. D., Gillanders B. M. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 534–565.

Green M., Caddell R., Eisfeld S., Dolman S., Simmonds M. (2012). Looking forward to ‘strict protection’: A critical review of the current legal regime for cetaceans in UK Waters. Chippenham: Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society.

Harris D. R. (2013). The development of socio-legal studies in the United Kingdom. Legal Studies 3 (3), 315–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-121X.1983.tb00427.x

House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee (2012). Wildlife crime third report of session 2012-2013. Vol. 1. (London: House of Commons).

IPBES. (2019) Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Available at: https://ipbes.net/global-assessment (Accessed 15 August 2022).

JNCC. (2017). JNCC guidelines for minimising the risk of injury to marine mammals from geophysical surveys (Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservancy Council).

Kelly C., Glegg G. A., Speedie C. D. (2004). Management of marine wildlife disturbance. Ocean Coast. Manage. 47 (1–2), 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2004.03.001

Marine Management Organisation (2022). Public Register. Available at: https://marinelicensing.marinemanagement.org.uk/mmofox5/fox/live/.

Miller A., McClenachan L., Uni Y., Phocas G., Hagemann M., Van Houtan K. (2019). The historical development of complex global trafficking networks for marine wildlife. Sci. Adv. 5 (3), 1–19. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav5948

Northridge S., Kingston A., Thomas L. (2018). Annual report on the implementation of council regulation (EC) no 812/2004 during 2017.

NPCC. (2018). Wildlife crime policing strategy: Safeguarding our wildlife 2018 – 2021 (Northallerton: North Yorkshire Police/National Police Chiefs Council).

Nurse A. (2011). Policing wildlife: Perspectives on criminality in wildlife crime. Pap Br. Criminol Conf. (London) 11, 38–53.

Nurse A. (2013). Privatising the green police: the role of NGOs in wildlife law enforcement. Crime Law Soc. Change 59 (3), 305–318. doi: 10.1007/s10611-013-9417-2

Nurse A. (2015). Policing wildlife: Perspectives on the enforcement of wildlife legislation (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

Nurse A., Harding N. (2022). Policing wildlife: The nature of wildlife crime in the UK and its public policy response (Nottingham: Nottingham Trent University).

Öberg J. (2013). The definition of criminal sanctions in the EU. Eur. Crimi Law Rev. 3 (3), 1–27. doi: 10.5235/219174414809354837

Pheasey H., Matechou E., Griffiths R. A., Roberts D. L. (2021). Trade of legal and illegal marine wildlife products in markets: Integrating shopping list and survival analysis approaches. Anim. Conserv. 24, 700–708. doi: 10.1111/acv.12675

Pinn E. (2016). Protected areas for harbour porpoise, but at what cost to their conservation? Environ. Law Rev. 18 (2), 197–103.

Potter G., Nurse A., Hall M. (Eds.) (2016). The geography of environmental crime (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

Quaglia S. (2022) More than 1.1m sea turtles illegally killed over past 30 years, study finds’ the guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/sep/09/more-than-11m-sea-turtles-illegally-killed-over-past-30-years-study-finds (Accessed 17 September 2022).

Ryland D., Nurse A. (2013). Mainstreaming after Lisbon: Advancing animal welfare in the EU internal market. Eur. Energy Environ. Law Rev. 22 (3), 101–115. doi: 10.54648/EELR2013008

Scottish Government. (2022). Wildlife crime in Scotland: 2020 annual report (Edinburgh: Scottish Government Environment and Forestry Directorate).

UK Parliament. (2021) Government response to the benyon review: Statement made on 8 June 2021 (Statement UIN HCWS71). Available at: https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2021-06-08/hcws71 (Accessed 15 August 2022).

UNODC. (2020) World wildlife crime report: Trafficking in endangered species, Vienna and new York: UNODC. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/wildlife/2020/World_Wildlife_Report_2020_9July.pdf (Accessed 15 September 2022).

UNODC. (2021) Wildlife and forest crime analytic toolkit report: United kingdom of great Britain and northern Ireland, Vienna and new York: UNODC. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/Wildlife/UK_Toolkit_Report.pdf (Accessed 20 December 2022).

Veríssimo D., Vieira S., Monteiro D., Hancock J., Nuno A. (2020). Audience research as a cornerstone of demand management interventions for illegal wildlife products: Demarketing sea turtle meat and eggs. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2 (3), 1–14. doi: 10.1111/csp2.164

Vincent K. (2014). Reforming wildlife law: Proposals by the law commission for England and Wales. Int. J. Crime Justice Soc. Democr 3 (2), 68–81. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v3i2.175

White R., Heckenberg D. (2014). An introduction to the study of environmental harm (Abingdon: Routledge).

Wildlife and Countryside Link. (2021) Wildlife crime in 2020: A report on the scale of wildlife crime in England and Wales (London: Wildlife and Countryside Link). Available at: https://www.wcl.org.uk/docs/WCL_Wildlife_Crime_Report_Nov_21.pdf (Accessed 10 August 2022).

Keywords: green criminology, marine wildlife, wildlife crime, animal abuse, animal harm, environmental law, environmental protection

Citation: Nurse A (2023) Preventing marine wildlife crime: An evaluation of legal protection and enforcement perspectives. Front. Conserv. Sci. 3:1102823. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2022.1102823

Received: 19 November 2022; Accepted: 23 December 2022;

Published: 03 April 2023.

Edited by:

Daan P. van Uhm, Utrecht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Andrea Albert Stefanus, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, IndonesiaHelen Uchenna Agu, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

Copyright © 2023 Nurse. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angus Nurse, YW5ndXMubnVyc2VAbnR1LmFjLnVr

Angus Nurse

Angus Nurse