- 1Willem Pompe Institute for Criminal Law and Criminology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2Key Laboratory of Ecology and Environmental Protection of Rare and Endangered Animals and Plants, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, China

The Laos borders with China, Myanmar, and Thailand have been identified as vulnerable hubs for illegal wildlife trade. In particular, some special economic zones (SEZs) in Laos are linked to illegal wildlife products, including tiger bones, rhino horn, and ivory for sale. SEZs are zones granted more free market-oriented economic policies and flexible governmental measures. In this study, we conducted on-site observations to identify high-valued wildlife, including (parts of) tigers, rhinos, bears, and pangolins in 2 of the 13 SEZs—the Golden Triangle and Boten SEZs—and conducted semistructured interviews with anonymous participants in 2017 and 2019. The trend regarding illegal wildlife trade in these SEZs seems to fluctuate. In the Golden Triangle SEZ, we found that the illegal trade in wildlife is present but occurs more covertly than previously observed; the trade transformed underground to online social media. In Boten SEZ, we found a decrease in bear bile products and an increase in the volume of tiger products openly for sale. Informants explained that the decrease of openly sold wildlife in the Golden Triangle SEZ has been influenced by media and political attention as well as inspections from local authorities, while in Boten SEZ, illegal wildlife traders diversified into tiger products, due to the decline in bear bile products and the reduction in the opportunity to obtain them.

Introduction

The illegal wildlife trade in Southeast Asia is considered a great threat to local biodiversity and ecosystems (Nijman, 2010; Harrison et al., 2016) and has a serious potential risk to public health (Coker et al., 2011; Greatorex et al., 2016; Erkenswick et al., 2020; Van Uhm and Zaitch, 2021). Laos is an important hub of illegal wildlife trade in the Southeast Asian region due to porous borders, low priorities of law enforcement, and significant Chinese interests (Nooren and Claridge, 2001; Gomez and Shepherd, 2018; Kasper et al., 2020). It has rich biodiversity (Soejarto et al., 1999; Tilker et al., 2020), and several endangered species have been driven to the edge of extinction or were extirpated such as the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus) and, as recently as 2019, the tiger (Panthera tigris) (Rasphone et al., 2019; Veríssimo and Glikman, 2020). The high value of products from endangered species, such as those from tigers, rhinos, and elephants, has increasingly attracted Chinese crime groups that exploited the economically deprived Laos environment in recent years (Linkie et al., 2018; Walker, 2018; Martin, 2019; Van Uhm, 2019).1

Laos is a quickly developing country, with an annual GDP growth of 7.7% since 2009. The government has assigned 13 special economic zones (SEZs) to stimulate economic development, attract investment, and create jobs by providing tax incentives, trade benefits, deregulation, and other investment privileges. The SEZs are said to play an important role in Laos’ development (PankeoVieng-vilay, 2016; Xinhua Silk Road, 2018), and infrastructures were built in some SEZs linked to the Chinese “One Belt One Road” initiative (UNODC, 2013; Gong, 2019; Van Uhm, 2019; Ng et al., 2020). However, several SEZs have also harbored illegalities such as wildlife trade, drug smuggling, and human trafficking (Tan, 2017; Van Uhm and Wong, 2021). Criminal networks are known to take advantage of weak inspection procedures, record-keeping systems, and the lack of coordination and cooperation between the special zone and customs and law enforcement authorities (Nyíri, 2012; Davis et al., 2016; Tan, 2017; Krishnasamy et al., 2018). According to the UNODC (2019: 18), “Casinos in SEZs in border areas of Mekong countries are known to facilitate money laundering and trafficking of illicit goods. In particular, SEZs in Lao PDR and Myanmar have become major gambling centers identified as key nodes in the illicit trade of drugs, precursors, and wildlife products.”

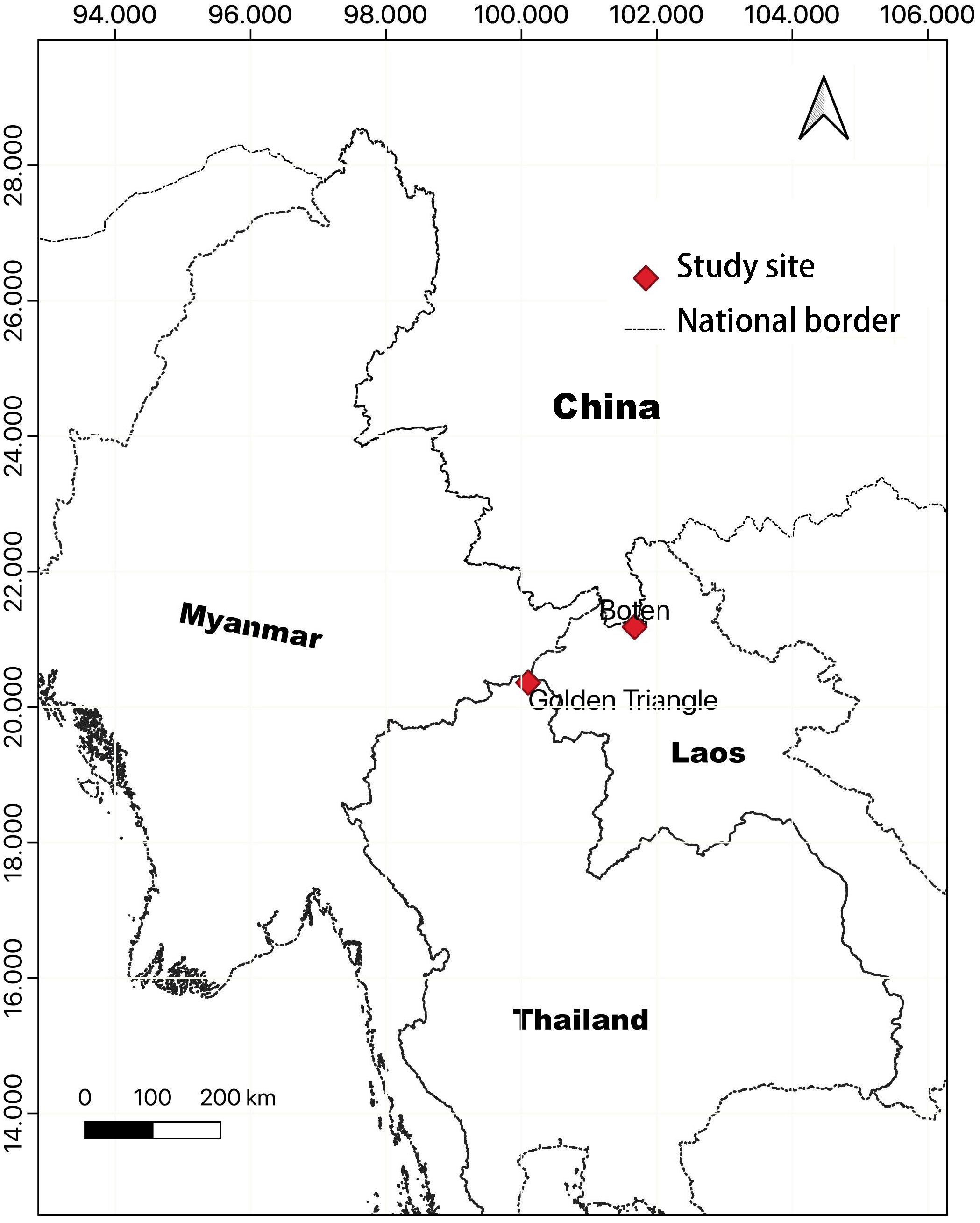

Among the SEZs in Laos, the Golden Triangle SEZ lies at the bordering area of Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand, and Boten SEZ lies at the border with China (Figure 1). Both SEZs in northern Laos were identified as major markets for tiger, bear, rhino, and pangolins among other illegal wildlife products (EIA, 2015; Krishnasamy et al., 2018). For example, products of tigers, rhinos, and pangolins were found to be openly sold in the Golden Triangle SEZ (EIA, 2015). Boten SEZ, in northern Laos bordering with Mohan of China, was visited by Krishnasamy et al. (2018). In one day, the authors found numerous wild species for sale in seven outlets, which included endangered species such as pangolin and bear parts. The wildlife trade in these two SEZs is complicated because different stakeholders are involved, both legitimate and illegitimate. The U.S. Treasury Department placed the co-owner and director of the Kings Romans Casino of the Golden Triangle SEZ on its organized crime sanctions blacklist in 2018, calling his network a transnational criminal organization engaged in “human trafficking and child prostitution, drug trafficking, and wildlife trafficking” (US Department of the Treasury, 2018). The SEZs are also under development, e.g., with $0.5 billion co-investment from stakeholders in Boten SEZ (PankeoVieng-vilay, 2016).

Figure 1 The position of the Golden Triangle and Boten special economy zones (SEZs) in Southeast Asia.

Understanding the situation of illegal wildlife markets requires long-term interdisciplinary approaches that integrate socioeconomic, biological, and criminological data (Singh, 2008; Ostrom, 2009; Blair et al., 2017). For instance, on-site observations of marketplaces to identify illegal species as determined by biologists contributed to the identification of authentic species/products, providing a link regarding the origins of the illegal products as well as allowing the mapping of visible illegal wildlife markets. Scholars revealed the trends and dynamics in the markets and provided insights on endangered species that are offered for sale and their quantities and prices on the black market (e.g., Nijman et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Gomez and Shepherd, 2018).

Criminological research based on interviews with people directly or indirectly involved in the illegal wildlife trade proved to be important in understanding the motivations, drivers, and decisions made in the illegal wildlife trade (Wyatt, 2013; Van Uhm, 2016; Pires and Moreto, 2018; Sollund, 2019; Wong, 2019). For example, the criminological literature shows that interventions can have a positive effect locally, but criminal activities can also move to other areas, the so-called “waterbed effect.” First, geographic displacement can mean that after interventions to tackle wildlife crimes in particular places, these crimes can move to other neighborhoods (Pires and Moreto, 2018). Second, illegal wildlife markets can also transform from visible illegal activities to underground markets through hard-to-detect channels via social media (Lavorgna, 2014). Third, wildlife crime groups can diversify into other markets in order to spread the risks and evolve their organizations (Van Uhm et al., 2021; Van Uhm and Nijman, 2022).

In this paper, we update the information on illegal wildlife in the Golden Triangle and Boten SEZs in Laos, by combining on-site observations and interviews with informants, including illegal wildlife traders. We visited the Golden Triangle SEZ in 2017 and 2019 and visited the Boten SEZ only in 2019. We aim to 1) present the species openly offered for sale from a snapshot of the local market and 2) analyze fluctuations in illegal wildlife trade and seek to explain these with reference to market transformation, geographic displacement, and diversification.

Materials and methods

Study area

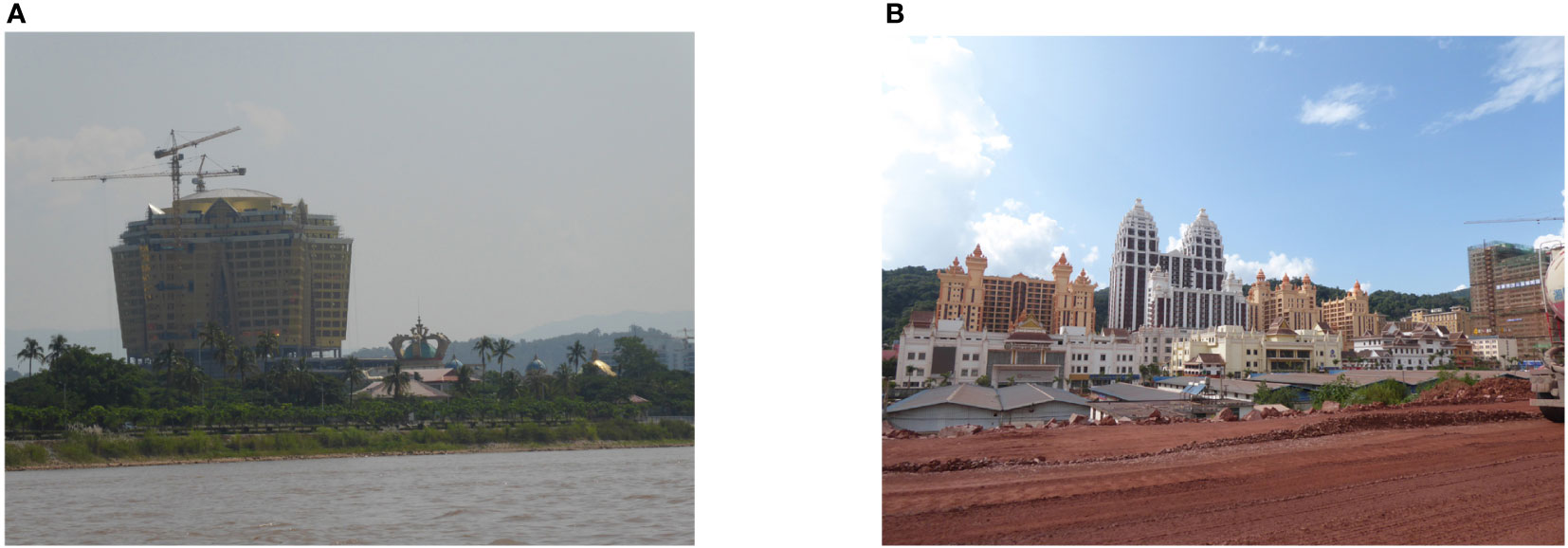

The Golden Triangle SEZ lies at the Mekong riverside, in Bokeo Province of Laos between 20°21′N and 20°22′N and between 100°5′E and 100°6′E, where Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand meet (Figure 1). The area of the Golden Triangle SEZ is around 3,000 ha, and it was co-launched as SEZ since 2007 by the Laos government and the Chinese Hongkong Kings Roman group. The main buildings in the town include the Kings Romans Casino and a small Chinatown with shops, as well as hotels and restaurants around the main casino (Figure 2A).

The Boten SEZ is located in Luang Namtha Province of Laos, toward Mohan of Yunan Province in South China. The coordination is 21°11′N to 21°12′N and 101°40′E to 101°41′E, with a total area of 1,640 ha (Figure 1). It was assigned as SEZ since 2003. The construction of a cross-border railway started in 2016 under the “Chinese One Belt One Road” initiative2 (Figure 2B).

On-site observations

The two SEZs were visited by the authors, a Chinese ecologist and a Dutch criminologist, in October 2019 and combined with an earlier on-site observation of the marketplace and interviews in the Golden Triangle SEZ in June 2017. We visited 13 shops and 3 restaurants in the Golden Triangle SEZ and 14 shops and 5 restaurants in Boten SEZ, including stores involved in former studies (i.e., EIA, 2015; Krishnasamy et al., 2018), as well as newly opened stores or restaurants. In both SEZs, the illegal wildlife trade is concentrated in certain areas; these areas with several streets were selected, and well-known illegal wildlife traders with shops were visited. Some of the visited shops specialized in traditional Chinese medicine, some sold tiger bone wines, while others were mainly doing business in animal products such as ivory, pangolin scales, and rhino horn. The same places were visited in 2017 and 2019, and the openly sold wildlife and wildlife products were observed and then later recorded on paper. The authors asked for the same high-valued wildlife species, including tigers, rhinos, bears, and pangolins, and recorded it when the wildlife for sale was openly displayed. The conservation status of the wildlife/products was checked according to the Laos Wildlife and Aquatic Law as well as the international Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

During the on-site observations, we asked for high-valued wildlife products such as ivory, rhino horn, pangolin scales, or tiger bone wine and whether we could book wildlife meals in restaurants, but no wildlife products were purchased or booked during the research. At each shop or restaurant, we recorded the GPS location, number of wildlife openly for sale, species, and conditions (taking photographs when possible) and elicited information from traders on the origin (captive bred or wild), market value, and turnover rates. We recorded evidence when the prices of wildlife products were openly displayed and by asking staff. The same on-site observation process was used in the Golden Triangle SEZ in 2017 and 2019 as well as in Boten SEZ in 2019 in order to compare the empirical results. Additional empirical data were acquired during conversations with store owners and sellers, which sometimes resulted in semistructured and open interviews as described below. The on-site observations are listed in Tables 1, 2, and the products found in the same area were compared between the two visits and earlier published references.

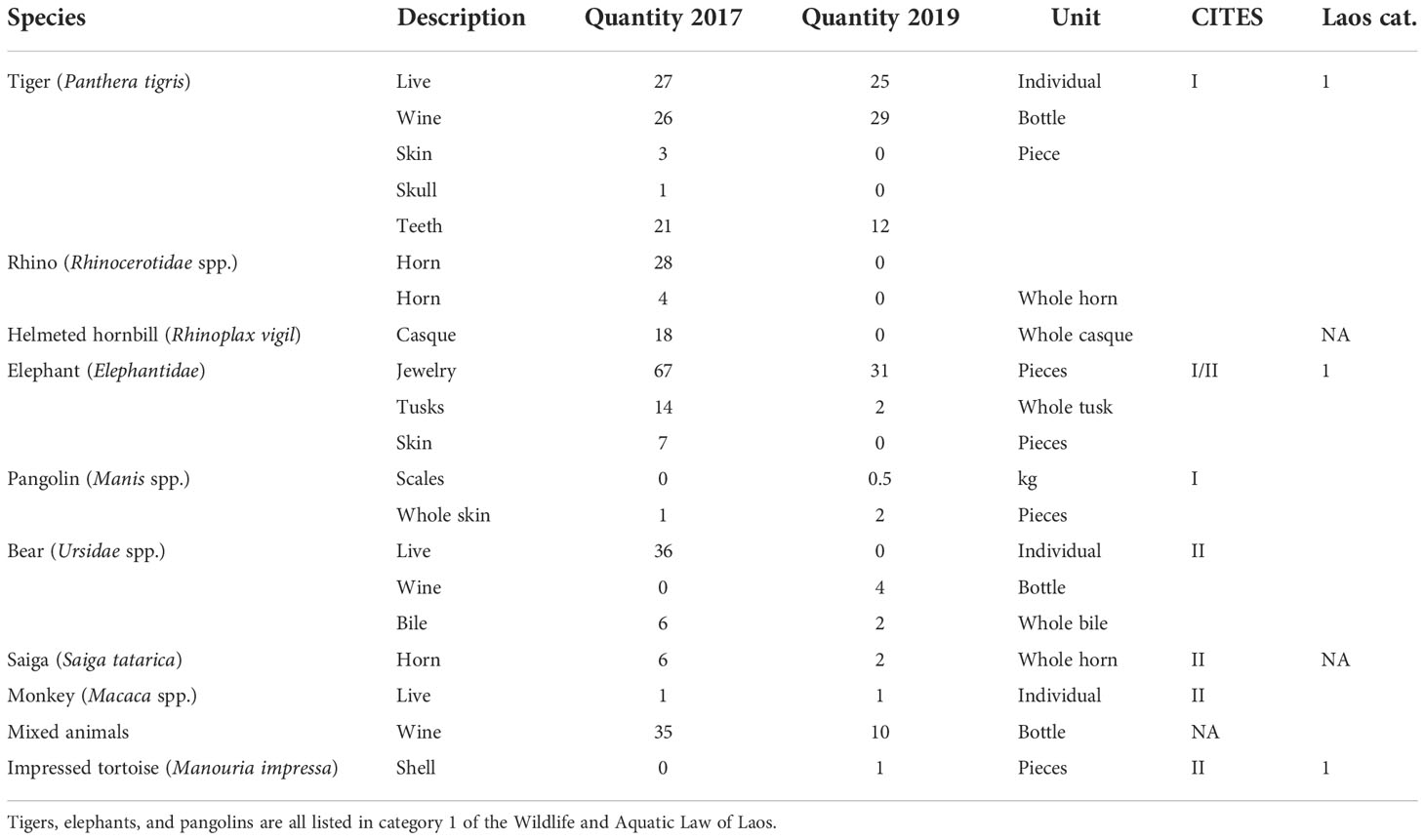

Table 1 Open wildlife trade in the Golden Triangle SEZ, Laos—the endangered species in the casino, wildlife shops, and wild meat restaurants in 2017 and 2019.

Table 2 Wildlife trade in Boten SEZ, Laos—the endangered species in the wildlife shops and wild meat restaurants in 2019.

Interviews and participant observation

During our field visits, we also performed semistructured and open interviews on the illegal wildlife trade, particularly in relation to high-valued wildlife, including (parts of) tigers, rhinos, bears, and pangolins. In total, we interviewed 11 people in the Golden Triangle SEZ in 2017 and 12 people in 2019. In addition, we interviewed 9 people in Boten SEZ in 2019. The informants were directly or indirectly involved in the illegal wildlife trade, e.g., sellers, traders, and smugglers. The respondents provided their informed consent, and the conversations were held in Mandarin and then translated into English. Regarding the storage and processing of empirical data, recordings are valuable; however, considering the sensitivity of the subject, some interviews were not recorded (Davis et al., 2020). In such cases, note-taking (afterward) ensured the recording of the empirical data. This also resulted in more trustful situations where people were able to speak in more detail about their illegal activities (Polsky, 1967).

An important method for finding respondents was through snowball sampling: future participants were recruited from among their acquaintances, which is useful in contacting members of a population that are difficult to access (Goodman, 1961). Contact with gatekeepers was of great importance to gain access to the social world of illegal entrepreneurs (Davies et al., 2016). Gatekeepers are persons who control access to others and include key persons in the organizations as well as small players in the trade; they are “people who can open doors to people or places, who are aware of certain risks” (Boekhout van Solinge, 2014: p. 40). For instance, the first author has been in contact before with one informant with contacts with the staff in the casino in Golden Triangle SEZ. With his introduction, we were able to interview the staff about the trade situation in the casino and town. We repeatedly visited several stores after the store owners were familiar with us, some trust was established, and they were willing to provide more information (Van Uhm and Wong, 2019). To ensure confidentiality, the respondents were anonymized and pseudonyms were used in place of the respondent’s real name. This also allowed us to talk to key players in the illegal wildlife trade, including important and big traders of wildlife for the SEZs. During the conversation with the above key players, we acquired information about their business mode, including online/offline business structures, the ways to transport products across the borders, and the role of diversification or geographic displacement.

In addition, participant observation was used to understand the local dynamics of the illegal wildlife trade. By observing the process of the illegal trade, through direct, naturalistic observations, it was possible to gain a more in-depth understanding of the socioeconomic context in which actors operate, as well as to corroborate or refute information derived from the respondents (DeWalt and DeWalt, 2011). In addition, by observing and interpreting behavior and everyday practices in the Golden Triangle SEZ and Boten SEZ, the observations provided us the opportunity to obtain information and to engage in informal conversations and chats throughout the study period, which was helpful in clarifying and confirming data collected from the interviews. Empirical data from participant observations were collected through detailed field notes (see Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

Limitations of the study

This study sheds light on the naturalistic and local empirical dimension of the illegal wildlife trade in both SEZs, but the empirical results of this study are not generalizable to other SEZs. Since there is a thriving illegal wildlife trade and many people are involved, our interview sample is not representative. Moreover, given the sensitive nature of our topic, we are aware of questions related to the honesty of our informants. In order to strengthen the credibility and dependability of our research, we triangulated our on-site observations with interviews. The fieldwork nature of our study also enabled us to cross-check initial theoretical concepts with informants throughout the data collection phase.

Results

The Golden Triangle SEZ

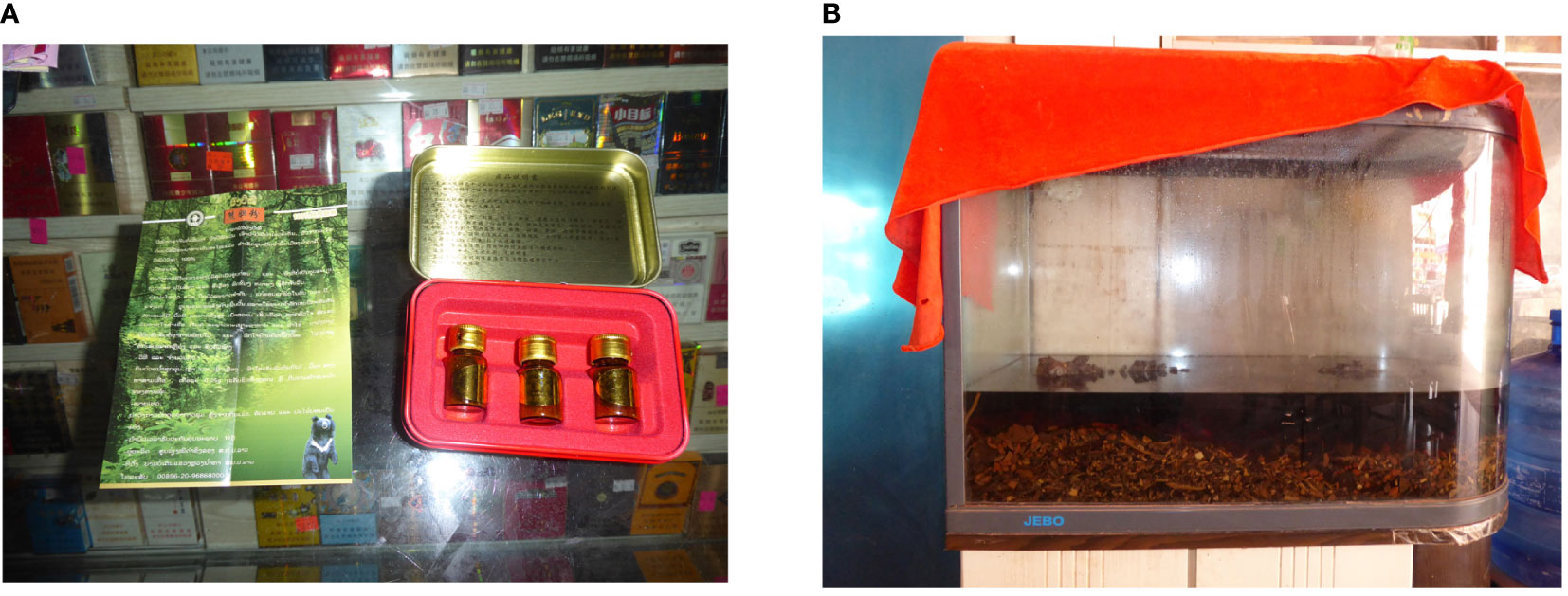

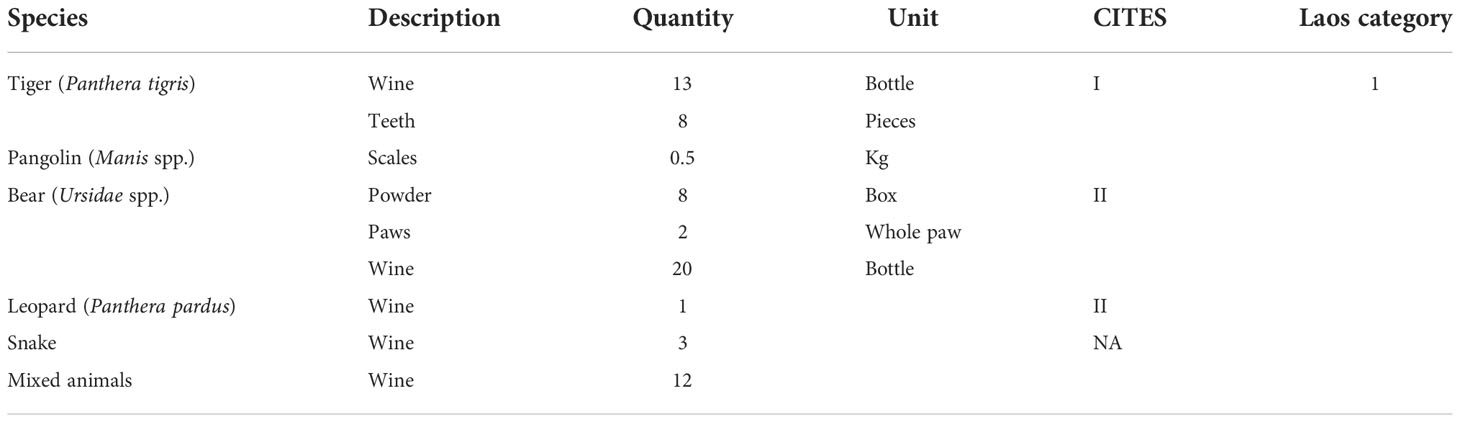

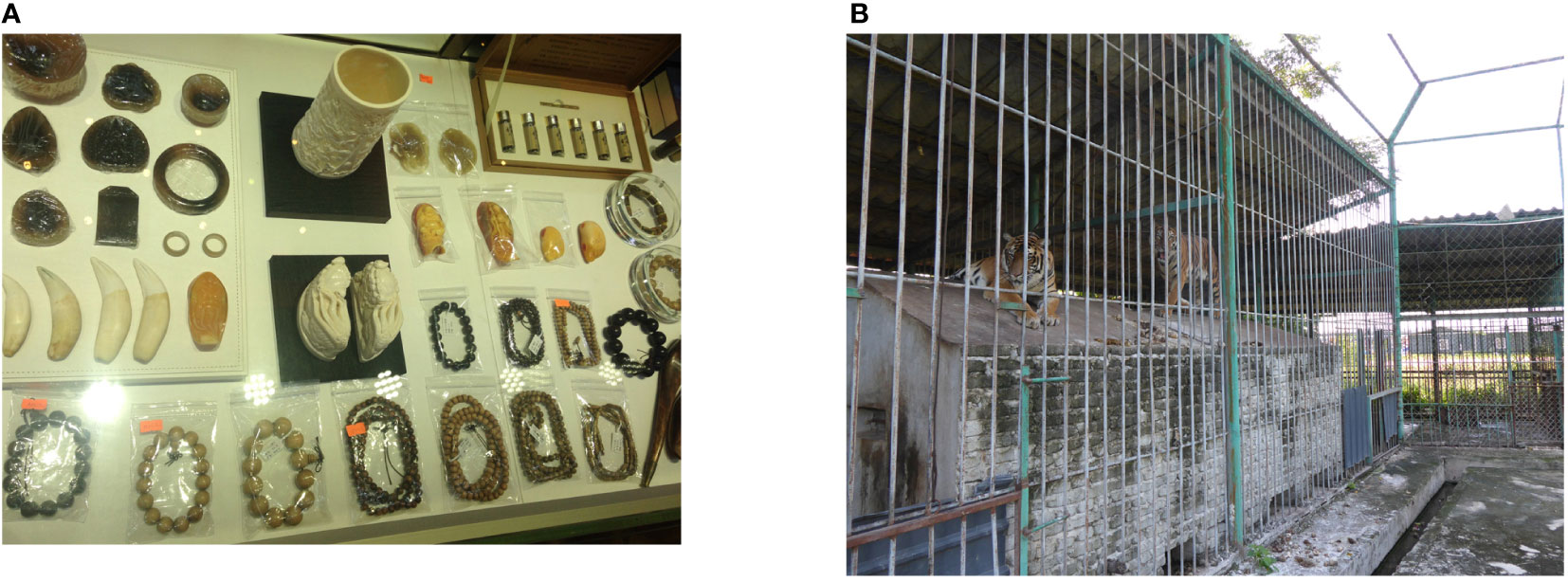

In 2017 and 2019, we recorded dozens of tiger bone wines (26 and 29, respectively), tiger teeth (21 and 12, respectively), and ivory pieces (67 and 31, respectively) openly for sale in the Golden Triangle SEZ. Even though 3 tiger skins, 1 tiger skull, and 7 pieces of elephant skin were recorded in 2017, these products were not found in 2019. Similarly, 28 rhino horn pieces, 4 rhino horns, and 18 casques of helmeted hornbills were offered for sale in 2017 but were not openly sold in 2019 (Table 1). The market has transformed and has become more “underground.” For example, pictures of illegal wildlife, such as rhino horn and tiger bone, were provided by key players in the illegal wildlife business who were able to arrange illegal wildlife on short notice. The products were in stock, e.g., upstairs in a building nearby. In addition, illegal wildlife products were available in the casino of the Golden Triangle SEZ in 2017, such as rhino horn pieces, ivory, helmeted hornbill casques, and bear bile (Figure 3A), but were not openly for sale anymore in 2019. In front of the casino, a small “zoo,” the Don Savannah Casino Zoo, was observed with 27 tigers and 36 bears in 2017. According to the informants, the animals were used for the tiger bone wines, tiger skins, and bear products (e.g., bear bile). In 2019, the bears and the cages of the bears had been removed to a different area, but 25 tigers were still present during our field trip (Figure 3B). Along the Mekong River, several restaurants offer endangered species, including pangolins. In general, fewer endangered species were openly offered for sale in 2019 in comparison to 2017 across the different wildlife species in the Golden Triangle SEZ.

Figure 3 (A) Rhino horn, tiger teeth, ivory, hornbill casques, and bear bile for sale inside the Kings Romans Casino, 2017; (B) tiger zoo, Golden Triangle SEZ, 2019.

Boten SEZ

In 2019, we recorded 13 bottles of tiger bone wine openly for sale, 8 tiger teeth, half a kilo of pangolin scales, and 20 bottles of bear bile wine among other wildlife products in Boten SEZ (Table 2). Although a previous study in Boten SEZ found 290 boxes of bear bile powder (Krishnasamy et al., 2018), the same store was visited but only openly displayed 3 boxes (Figure 4A). These particular bear bile products and their packaging have been found by the authors for sale in other parts of Laos (e.g., Vientiane; Luang Namtha), Myanmar (e.g., Kengtung; Tachileick; Mong La), and China (e.g., Daluo; Kunming). The tiger bone wines were sold in shops but were also observed in restaurants. In one of the restaurants, a backbone of a tiger was observed in a tiger bone wine aquarium (Figure 4B). On a street just off the main road, many shops sold wines, including tiger bone wines. The bottles of tiger bone wine were openly sold to customers, some of them on their way back to China. In addition, some shops in the “old” market in Boten SEZ sold openly tiger teeth and bear bile powder boxes. Even though the volume of bear products openly for sale has decreased, illegal tiger products for sale seem to be increasing in Boten SEZ. This is in line with anecdotal evidence that bear trade is switching over to tiger trade and that illegal wildlife traders diversify into the tiger trade (Coals et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2020).

Interviews and observations

In the Golden Triangle SEZ and Boten SEZ, 84% (n = 27) of our informants were store owners, traders, staff in the casino, or waiters in restaurants.3 They were directly or indirectly involved in the illegal trade in wildlife as sellers, traders, facilitators, or smugglers. In the Golden Triangle SEZ, tiger bone wine traders explained how high-quality tiger bone wine is produced in large aquariums with complete tiger skeletons where the wine has been aged for over 3 years in the center of the small Chinatown. The prices vary on the quality of the displayed tiger bone wines, from a few hundred to thousands of USD per bottle of tiger bone wine from the top segment (¥ 1,000–20,000). The tiger traders explained that they have close ties with the co-owner of the Golden Triangle SEZ in order to facilitate their (illegal) business.

The first author knew another trader of rhino horns and tiger bone wines from the field trip in 2017. At that time, the trader openly sold rhinoceros horns, tiger wines and skins, and casques of the helmeted hornbill among other high-valued wildlife products. He explained that his store has been raided by the Laos police, so he is now relocated slightly outside the China town center. We visited his new shop and he explained that he still trades under the counter in rhino horn and tiger products among other illegal wildlife, and people know about this via his WeChat account. This was confirmed by other respondents, who indicated that the open sales of illegal wildlife products in the Golden Triangle SEZ are declining,4 but the trade continues via social media. Illegal wildlife traders explained how they increasingly use WeChat for business purposes in order to avoid detection. This reflects the transformation of the market and seems to support that the open trade is slightly disappearing compared to 2017, but that illegal wildlife products are still available on request. Remarkably, three shops on the main street of Chinatown still sell openly tiger bone wine.

Another clear difference in time is that, in 2017, the casino in the Golden Triangle SEZ sold openly rhino horn, ivory, tiger bone wine, and casques of helmeted hornbills, while that was no longer the case in 2019. Two interviewed employees of the casino explained that this has been the case since the US sanctions, but that both wildlife and drugs (methamphetamine) are still provided on request. Finally, the “zoo” with tigers is smaller than in 2017. In 2017, in addition to tigers, there was also an enclosure for bears. The animals are said to be intended for zoo purposes, but in reality, the production of tiger bone wines, meat, and skins is part of the “business model,” according to informants. However, the 36 bears were removed to a different section, and recently, another tiger and bear zoo/farm has been established nearby, which reflects geographic displacement to other areas.5

In Boten, one of our respondents was a key wildlife trader in the main street, well-known for her trade in wildlife products, particularly bear bile (Krishnasamy et al., 2018). She explained that bear bile products were locally manufactured in the bear farm of Boten, but since the bear farm was removed, trading in other products has become more attractive. For example, a relatively large number of shops off the main road now have diversified into tiger bone wine businesses and have tiger products in stock and openly for sale.

According to an illegal wildlife trader, the tiger bone wine can easily be smuggled across the border into China, as they put the tiger bone wine in another bottle and bring the empty tiger bone bottle separately. In this way, there is a low chance of control at the border. The same technique was also mentioned during an interview with two key tiger traders in the Golden Triangle SEZ and seems to be common knowledge among tiger bone wine traders in Laos.

Several wildlife traders referred to relatives and friends who live in both the Boten and Golden Triangle SEZs and are part of the same wildlife networks; this would facilitate the trade between the two special economic zones. For instance, two illegal wildlife traders in the Golden Triangle SEZ worked before in Boten SEZ, and relatives in the Golden Triangle SEZ provide rhino horns and ivory to a wildlife trader in Boten SEZ.

Moreover, several wildlife traders explained to have good contacts with the customs. The owner of a restaurant that offers tiger bone wine and has bear paws and pangolins in a freezer in Boten explained that the Laos customs are good friends, and the authors observed how a customs official indeed had lunch at their place, while tiger bone wine, bear paws, and pangolin meat are openly advertised in the restaurant. The owner explained that their symbiotic relationship enables wildlife to be smuggled into China without intervention. Another wildlife trader argued that recently it has become more difficult to smuggle whole rhinoceros’ horns into China; for larger consignments, they use rather professional smuggling networks that are also involved in drugs. This reflects the diversification of crime groups into wildlife trafficking (Van Uhm and Wong, 2021).

Discussion

The two visited special economic zones are notable because of the Chinese social and economic embeddedness. The main investors and consumers observed in these two areas are Chinese nationals. They run on Beijing time, road signs are in Mandarin, most workers are Chinese nationals, and the Yuan is the main currency, which reflects the importance of the perceived Chinese influence in the SEZs in the borderlands of the economically deprived Golden Triangle area.

With the Chinese economic growth in the 1990s and 2000s, a new class of Chinese entrepreneurs looked across the border to invest and search for economic opportunities. In combination with a series of policy initiatives (NEM) in Laos from 1986, this has encouraged a more open market-oriented economy to stimulate trade. In this context, special economic zones were also set up to attract investments and trade from abroad. Private traders were officially permitted to compete with state enterprises, and in the northwestern Laos border, trading conditions with China have seriously improved. However, the socioeconomic and geopolitical conditions also facilitate the trafficking of contraband across the borders (Van Uhm, 2023 in press; Walker, 1999: 72–75). In the context of China’s One Belt One Road initiative with infrastructure investments (Gong, 2019; Ng et al., 2020), this provides new opportunities for illegal trade in wildlife (Lemieux and Bruschi, 2019; Van Uhm, 2019).

In this paper, we updated the illegal wildlife trade dynamics in the two SEZs, the Golden Triangle SEZ and Boten SEZ, by combining methods of on-site observations of the marketplace and interviews with informants involved in the wildlife trade in order to identify and understand the fluctuations of the illegal wildlife markets. Based on the on-site observations and interviews, our study provides a presentation of the species openly offered for sale from a snapshot of the local market together with empirical data about the transformation, geographic displacement, and diversification of illegal wildlife markets in the Golden Triangle and Boten SEZs. We found that despite being protected by domestic and international laws and regulations, products from tigers, pangolins, and rhinos among other endangered species are still flourishing in these two SEZs.6

While the open illegal wildlife trade in the Golden Triangle SEZ seems to decrease, the trade in tiger, pangolin, and rhino products still exists, albeit more covertly and going underground. Informants explained that this has been influenced by local enforcement and international attention, e.g., by placing the Kings Romans Casino on the US organized crime sanctions blacklist in 2018. Our on-site observations and interviews indicate that consequently the trade has transformed to popular social media, such as WeChat. The increasing trend of illegal wildlife via social media has been noticed by several illegal wildlife studies and reflects how criminal underworlds increasingly become digital, influenced by political dynamics and enforcement priorities (Van Uhm, 2016; Di Minin et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). According to the informants, some investors and illegal wildlife traders have moved to other SEZs. This is in line with criminological findings when police patrols are increased: crime in that area seems to decline, but the decline may be occurring because the offenders have moved to a new location, not because the offenders have stopped offending (Moreto and Pires, 2018; Petrossian, 2019). Remarkably, several shops in the small Chinatown still openly sell tiger bone wine. Informants stated that this may have to do with the involvement of powerful people with political relations and immunity as well as difficulties to test whether tiger wine is based on a real tiger product.

In Boten SEZ, in comparison to the on-site observations by Krishnasamy et al. (2018) that found many bear products, including 290 boxes of bear bile powder boxes, we found 20 bottles of bear bile wine and 8 boxes of bear bile powder openly for sale. The local market for bear products was reduced because the bear farm close to Boten SEZ moved to another area, as explained by the informants. This partly reflects the “waterbed effect” where interventions can have a positive effect locally but may rise somewhere else due to the displacement of wildlife crimes. In addition to the geographical effects, enforcement priorities for certain species may also lead to an increase in other illegal wildlife species due to opportunity and diversification structures as discussed in criminological studies (Petrossian et al., 2016; Moreto and Pires, 2018; Van Uhm and Wong, 2021). With the availability of tiger bone wines, the trade in tiger bone wines seems to have increased in Boten SEZ in recent years as several shops sold it openly. The analysis of the interviews suggested that this may be a result of difficulties in product identification, the loose control and corruption of local customs officials, the change in preference due to greater attention to bear bile products, and neglecting tiger products in recent years. However, this warrants further investigation.

Both cases illustrate how the illegal wildlife trade networks are able to anticipate new situations, quickly switch their focus areas, or reshape illicit trade operations from offline to online. These capacities to operate flexibly increase the survival chances of criminal enterprises and illustrate how they can move freely through the enforcement landscape. Moreover, the illegal wildlife trade networks are socioeconomically and politically embedded in the local context; friends, family members, or corrupt officials ensure a secure environment for illegal wildlife traders (Van de Bunt et al., 2014). For instance, illegal wildlife products, including tiger bones, bear bile, and rhino horns, are traded by relatives in Boten and the Golden Triangle SEZs, while symbiotic relations with officials facilitate the wildlife crime networks to evolve and diversify (Van Uhm and Wong, 2021). This ensures interconnected networks and protected trade chains in and between the two special economic zones in the Golden Triangle borderlands that seriously complicate the prevention and enforcement of wildlife crimes.

Since China has banned all the consumption of wild meat after the outbreak of COVID-19 and strengthened the control on the border (Chinese NPC, 2020), we may expect to see a change in the wildlife trade in the near future. It can lead to a behavior change of Chinese visitors of the SEZs in a positive way due to awareness of the health risks associated with consuming wild products. However, the current regulations only confine the trade of terrestrial animals as food but did not cover the aquatic animal and medical animal product trade (Xiao et al., 2021). Moreover, it can also lead to increased demand from Chinese visitors after the reopening of the borders, because of the stricter controls in China. Informants in both SEZs explained that Chinese customers come to the areas not only for investment but also for gambling, prostitution, or drugs, in addition to wildlife. In this socioeconomic and criminogenic environment, both the Golden Triangle and Boten SEZs are quickly developing, but the current control and prevention of illegal wildlife trade is still underdeveloped.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MZ attended the on-site observations of the marketplace and interviews in 2019. DU attended both the on-site observations of the marketplace and interviews in 2017 and 2019. MZ mainly drafted the Introduction and Methods sections. DU wrote the main parts of the Results and Discussion sections. Both authors revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research is funded by the Dutch Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) (Research project: 016.Veni.195.040) and is supported by Guangxi Key Laboratory of Rare and Endangered Animal Ecology, Guangxi Normal University (20-A-01-03) and Guangxi Science & Technology Project (2021AC19106).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the informants in the Golden Triangle and Boten SEZs for their valuable information and to Dr. Chris Shepherd and Mr. Lasa Bone for their help in getting the conservation list of Laos Wildlife and Aquatic Law.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ In Laos, local people also consume wildlife (e.g., Singh, 2010; Davis et al., 2016; Davis and Glikman, 2020), which places additional pressure on these species beyond criminal networks.

- ^ The effect of the Chinese “One Belt One Road” initiative has a global impact for legal and illegal trade, e.g., there are increasing reports of wildlife trade occurring in Chinese belt and road projects (Lemieux and Bruschi, 2019; Van Uhm, 2019).

- ^ Sixteen percent of our informants were not directly or indirectly involved in the illegal wildlife trade but were able to provide information about the illegal trade, such as taxi drivers, citizens, or employees of legitimate businesses.

- ^ This is interesting in the context of the normalized trade versus actual consumption as it may be possible that the trade being pushed underground has reduced actual consumption (Rizzolo, 2020).

- ^ At a local market, we observed two captive-bred turtles and some frogs. A local store owner told us that the wild meat market is open on a certain day during the week and wild meat is traded between 3 and 4 a.m. He explained that most of the customers in the early morning were staff from the restaurants in the Golden Triangle SEZ.

- ^ Less endangered species were not the focus of this study but were “on the horizon” for being traded.

References

Blair M. E., Le M. D., Sethi G., Thach, H. M., Nguyen V. T. H., Amato G., et al. (2017). The importance of an interdisciplinary research approach to inform wildlife trade management in southeast asia. BioScience 67, 995–1003. doi: 10.1093/biosci/bix113

Boekhout van Solinge T. (2014). Researching illegal logging and deforestation. J. Crime Criminal Law Criminal Justice 3 (2), 35–48. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v3i2.179

Coals P., Moorhouse T. P., D’Cruze N. C., Macdonald D. W., Loveridge A. J. (2020). Preferences for lion and tiger bone wines amongst the urban public in China and Vietnam. J. Nat. Conserv. 57, 125874. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2020.125874

Coker R. J., Hunter B. M., Rudge J. W., Liverani M., Hanvoravongchai P. (2011). Emerging infectious diseases in southeast asia: Regional challenges to control. Lancet 377, 599–609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62004-1

Davis E. O., Glikman J. A. (2020). An assessment of wildlife use by northern Laos nationals. Animals 10 (4), 685. doi: 10.3390/ani10040685

Davis E. O., O'Connor D., Crudge B., et al. (2016). Understanding public perceptions and motivations around bear part use: A study in northern laos of attitudes of Chinese tourists and lao pdr nationals. Biol. Conserv. 203, 282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.09.009

Davis E. O., Veríssimo D., Crudge B., Lim T., Roth V., Glikman J. A. (2020). Insights for reducing the consumption of wildlife: The use of bear bile and gallbladder in Cambodia. People Nat. 2 (4), 950–963. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10164

DeWalt K. M., DeWalt B. R. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworks (Lanham: AltaMira Press).

Di Minin E., Fink C., Tenkanen H., Hiippala T. (2018). Machine learning for tracking illegal wildlife trade on social media. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2 (3), 406–407. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0466-x

EIA (2015). Sin city: Illegal wildlife trade in laos’ golden triangle special economic zone (Washington DC: EIA).

Erkenswick G., Prost S., Davis E. O., Meredith A., Phillips J., Owen M., et al. (2020). Viewpoint: COVID-19: Rigorous wildlife disease surveillance: A decentralized model could address global health risks associated with wildlife exploitation. Science 369 (6500), 145–147. doi: 10.1126/science.abc0017

Gomez L., Shepherd C. R. (2018). Trade in bears in lao PDR with observations from market surveys and seizure data. Global Ecol. Conserv. 15, e00415. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00415

Gong X. (2019). The belt & road initiative and china’s influence in southeast Asia. Pacific Rev. 32 (4), 635–665. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2018.1513950

Goodman L. A. (1961). Snowball sampling. Ann. Math. Stat 32 (1), 148–170. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177705148

Greatorex Z. F., Olson S. H., Singhalath S., Silithammavong S., Khammavong K., Fine A. E., et al. (2016). Wildlife trade and human health in lao pdr: An assessment of the zoonotic disease risk in markets. PloS One 11, e0150666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150666

Harrison R. D., Sreekar R., Brodie J. F., Brook S., Luskin M., O'Kelly H., et al. (2016). Impacts of hunting on tropical forests in southeast asia. Conserv. Biol. 30, 972–981. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12785

Kasper K., Schweikhard J., Lehmann M., Ebert C. L., Erbe S., Wayakone P., et al. (2020). The extent of the illegal trade with terrestrial vertebrates in markets and households in khammouane province, lao pdr. Nat. Conserv. 41, 25. doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.41.51888

Krishnasamy K., Shepherd C. R., Or O. C. (2018). Observations of illegal wildlife trade in boten, a chinese border town within a specific economic zone in northern lao pdr. Global Ecol. Conserv. 14, e00390. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00390

Lavorgna A. (2014). Wildlife trafficking in the Internet age. Crime Sci. 3 (1), 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40163-014-0005-2

Lemieux A. M., Bruschi N. (2019). The production of jaguar paste in Suriname: A product-based crime script. Crime Sci. 8 (1), 1–5. doi: 10.1186/s40163-019-0101-4

Linkie M., Martyr D., Harihar A., Mardiah S, Hodgetts T, Risdianto D, et al. (2018). Asia's economic growth and its impact on indonesia's tigers. Biol. Conserv. 219, 105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.01.011

Moreto W. D., Pires S. F. (2018). Wildlife crime: An environmental criminology and crime science perspective (Durham: Carolina Academic Press).

Ng L. S., Campos-Arceiz A., Sloan S., Hughes A. C., Tiang D. C. F., Li B. V., et al. (2020). The scale of biodiversity impacts of the belt and road initiative in southeast Asia. Biol. Conserv. 248, 108691. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108691

Nijman V. (2010). An overview of international wildlife trade from southeast Asia. Biodiversity Conserv. 19, 1101–1114. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9758-4

Nijman V., Zhang M. X., Shepherd C. R. (2016). Pangolin trade in the mong la wildlife market and the role of Myanmar in the smuggling of pangolins into China. Global Ecol. Conserv. 5, 118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2015.12.003

Nooren H., Claridge G. (2001). Wildlife trade in Laos: The end of the game (Amsterdam: IUCN-The World Conservation Union).

Nyíri P. (2012). Enclaves of improvement: Sovereignty and developmentalism in the special zones of the China-lao borderlands. Comp. Stud. Soc. History 54 (3), 533–562. doi: 10.1017/S0010417512000229

Ostrom E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325, 419–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1172133

PankeoVieng-vilay (2016). The oppurtunities and challenges of laos special economic zone and specific economic zone(in chinese). J. Shenyang Univ. Technology(SocialScienceEdition) 9, 214–218.

Petrossian G. A., Pires S. F., Van Uhm D. P. (2016). An overview of seized illegal wildlife entering the united states. Global Crime 17 (2), 181–201. doi: 10.1080/17440572.2016.1152548

Petrossian G. A. (2019). The last fish swimming: The global crime of illegal fishing. Santa Barbara: Praeger.

Rasphone A., Kéry M., Kamler J. F., Macdonald D. W. (2019). Documenting the demise of tiger and leopard, and the status of other carnivores and prey, in lao PDR's most prized protected area: Nam et-phou louey. Global Ecol. Conserv. 20, e00766. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00766

Rizzolo J. B. (2020). Effects of legalization and wildlife farming on conservation. Global Ecol. Conserv. 13, e01390. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01390

Singh S. (2008). Social challenges for integrating conservation and development: The case of wildlife use in laos. Soc. Natural Resour. 21, 952–955. doi: 10.1080/08941920802077515

Singh S. (2010). Appetites and aspirations: Consuming wildlife in Laos. Aust. J. anthropology 21 (3), 315–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-6547.2010.00099.x

Soejarto D. D., Gyllenhaal C., Regalado J. C., Pezzuto J., Fong H., Tan G. T., et al. (1999). Studies on biodiversity of Vietnam and Laos: The uic-based icbg program. Pharm. Biol. 37, 100–113. doi: 10.1076/1388-0209(200010)37:SUP;1-W;FT100

Sollund R. A. (2019). The crimes of wildlife trafficking: Issues of justice, legality and morality (London: Routledge).

Tan D. (2017). “Chinese Enclaves in the golden triangle borderlands,” in Chinese Encounters in southeast Asia: How people, money, and ideas from China are changing a region (Washington: University of Washington Press), 136.

Tilker A., Abrams J. F., Nguyen A., Hörig L, Axtner. J, Louvrier J, et al. (2020). Identifying conservation priorities in a defaunated tropical biodiversity hotspot. Diversity Distributions 26, 426–440. doi: 10.1111/ddi.13029

UNODC (2013). Transnational organized crime threat assessment: East Asia and the pacific (Vienna: UNODC).

UNODC (2019). Transnational organized crime in southeast Asia: Evolution, growth and impact (Vienna: UNODC).

US Department of the Treasury (2018) Treasury sanctions the zhao wei transnational criminal organization. Available at: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0272.

Van de Bunt H., Siegel D., Zaitch D. (2014). The social embeddedness of organized crime. in Paoli L. (Ed). The oxford handbook of organized crime (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Van Uhm D. P. (2016). The illegal wildlife trade: Inside the world of poachers, smugglers and traders (New York: Springer).

Van Uhm D. P. (2019). “Chinese Wildlife trafficking networks along the silk road,” in Organized crime and corruption across borders. Eds. Lo T.W., Siegel D., Kwok S. I. (London: Routledge).

Van Uhm D. P. (2023). In press. Organized Environmental Crime: Black markets in gold, wildlife, and timber (Santa Barbara: Praeger).

Van Uhm D. P., South N., Wyatt T. (2021). Connections between trades and trafficking in wildlife and drugs. Trends Organized Crime 24 (4), 425–446. doi: 10.1007/s12117-021-09416-z

Van Uhm D. P., Wong R. W. Y. (2019). Establishing trust in the illegal wildlife trade in China. Asian J. Criminology 14 (1), 23–40. doi: 10.1007/s11417-018-9277-x

Van Uhm D. P., Zaitch D. (2021). “Defaunation, wildlife exploitation and zoonotic diseases - a green criminological perspective,” in Notes from isolation: Global criminological perspectives on coronavirus pandemic. Ed. Siegel D. (The Hague: Eleven International Publishing).

Van Uhm D. P., Nijman R. C.C. (2022). The convergence of environmental crime with other serious crimes: Subtypes within the environmental crime continuum. European J. Criminology, 19 (4), 542–61.

Van Uhm D. P., Wong R. Y. (2021). Chinese Organized Crime and the Illegal Wildlife Trade: Diversification and Outsourcing. Trends in Organized Crime 24 (4), 486–505.

Veríssimo D., Glikman J. A. (2020). Influencing consumer demand is vital for tackling the illegal wildlife trade. People Nat. 2 (4), 872–876. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10171

Walker A. (1999). The legend of the golden boat: Regulation, trade and traders in the borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma (Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press).

Wyatt T. (2013). Wildlife trafficking: A deconstruction of the crime, the victims, and the offenders (London: Springer).

Xiao L., Lu Z., Li X., Zhao X., Li B. V. (2021). Why do we need a wildlife consumption ban in China? Curr. Biol. 31 (4), R168–R172. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.036

Xinhua Silk Road (2018). Invest in laos: The special economic zones and specific econmomic zone, and preferential policy (in chinese) (Xinhua Silk Road).

Xu Q., Cai M., Mackey T. K. (2020). The illegal wildlife digital market: An analysis of Chinese wildlife marketing and sale on Facebook. Environ. Conserv. 47 (3), 206–212. doi: 10.1017/S0376892920000235

Keywords: illegal wildlife trade, cross-border crime, Laos special economic zone, social ecological, conservation, green criminology

Citation: van Uhm DP and Zhang M (2022) Illegal wildlife trade in two special economic zones in Laos: Underground–open-sale fluctuations in the Golden Triangle borderlands. Front. Conserv. Sci. 3:1030378. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2022.1030378

Received: 28 August 2022; Accepted: 26 October 2022;

Published: 06 December 2022.

Edited by:

Richard T. Corlett, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Melanie Flynn, University of Huddersfield, United KingdomMichael J. Lynch, University of South Florida, United States

Copyright © 2022 van Uhm and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daan P. van Uhm, ZC5wLnZhbnVobUB1dS5ubA==

Daan P. van Uhm

Daan P. van Uhm Mingxia Zhang

Mingxia Zhang