- Integrated Land and Resource Governance Program, Tetra Tech, Burlington, VT, United States

Community-based natural resource management bodies, including Community Resource Boards (CRBs) and Community Scouts, are responsible for governance and wildlife law enforcement in Zambia’s Game Management Areas (GMA), community lands that buffer the National Parks. Despite commitments to inclusive governance and benefit sharing, men dominate the wildlife and natural resource sectors in Zambia; they make up the vast majority of wildlife scouts who patrol the GMAs and hold most positions on the CRBs who allocate benefits and decide on management priorities. Gender blind structures within community governance institutions during the recruitment and training process and social and gender norms that see leadership roles as men’s domain act as barriers to women’s participation in the sector. In response, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) invested in a comprehensive package of activities to increase women’s effective participation in wildlife governance and law enforcement, including gender-responsive CRB elections, empowerment training for newly elected women candidates, revised community scout training curriculum, and capacity building support for organizations that support scouts and CRBs. The intervention helped increase women’s representation in CRBs from four percent to 25 percent in pilot communities. It also supported the Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) to recruit the first gender balanced cohort of community scout recruits and field an all-women patrol unit in Lower Zambezi National Park.

1. Introduction

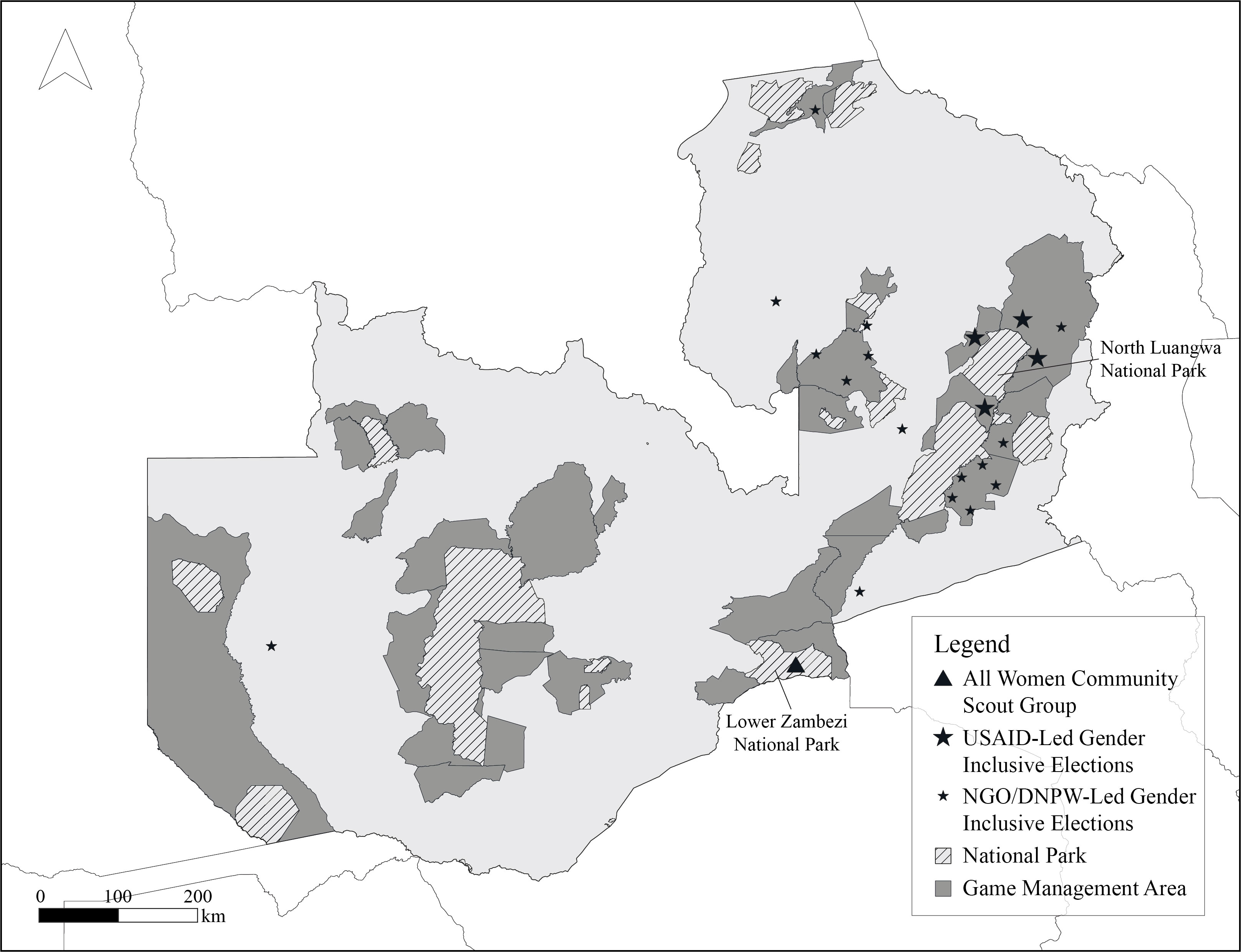

Zambia’s protected areas are home to abundant wildlife including elephant, giraffe, lion, leopard and rhino, which bring in millions of dollars from tourism, hunting, and carbon credits, as well as international biodiversity conservation support. Protected areas account for 20 percent of land in Zambia, including 20 National Parks and 36 Game Management Areas (GMAs), which act as buffer zones around the National Parks (see Figure 1) (Lindsey et al., 2014). While settlements are not allowed in National Parks, GMAs are mixed use spaces, where communities live alongside protected area habitats. But humans and animals are coming in more frequent contact with one another due to increasing wildlife populations from successful conservation efforts, as well as agricultural expansion due to increasing populations and market opportunities. This intensifies human-wildlife conflict that results in crop destruction, livestock attacks, and deadly human-animal encounters. At the same time poaching remains a major threat to animal populations in GMAs, both for bushmeat and the illegal wildlife trade (Lindsey et al., 2014; Watson et al., 2015).

Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) has been widely adopted in Zambia since the late 1990s and is codified in the Wildlife Act of 2015, as well as the Community Forest Management Regulations of 2018. Management rights in GMAs are devolved to Community Resource Boards (CRBs), elected from local communities, and community scouts are hired to carry out law enforcement responsibilities under the Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) and with support from non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Global criticisms of CBNRM approaches relate to elite capture, non-transparent governance institutions, and a lack of consideration of community dynamics (Agrawal and Gibson, 1999; Sommerville et al., 2010; Barnes and Child, 2014; Musgrave and Wong, 2016). Gender and social inclusion are often criticized as afterthoughts in the implementation of CBNRM approaches (Flintan and Tedla, 2007).

A baseline gender assessment on CBNRM in Zambia (Malasha and Duncan, 2020) identified the current status and key barriers to women’s full participation within the wildlife sector, revealing two key areas of exclusion for women: wildlife governance institutions and formal employment opportunities. Men dominate CRBs that make decisions around community natural resources and revenue streams (Malasha, 2020). Yet women have a strong vested interest in how natural resources are managed. Women and men bring unique knowledge and perspectives to decision-making bodies, though women tend to be underrepresented in management institutions (Ngece, 2006; Giesecke, 2012; FAO, 2018). A growing body of evidence shows women’s participation in community resource governance brings benefits not only to women, but to their families, communities, and conservation efforts more broadly (Agarwal, 2009; Mwangi et al., 2011; Leisher et al., 2016; Beaujon Marin and Kuriakose, 2017). Prior to 2018, women made up less than 10 percent of CRB members across Zambia’s 76 elected CRBs, and only four were led by women (Malasha, 2020). Many CRBs interviewed had no women representatives (Malasha and Duncan, 2020).

According to the Wildlife Act, CRBs are responsible for identifying community priorities for benefit sharing, distributing benefits, and representing community issues with the DNPW. The lack of women’s full representation has meant that women’s issues are rarely prioritized (Malasha, 2020). The gender assessment found that even when a CRB earmarked funds for community projects that directly addressed the needs and interests of women, funds were often redirected to areas that men were more interested in. For example, one CRB reported that they spent gender earmarked funds on a social event, a community organized football match (a sport traditionally only played by men) (Malasha and Duncan, 2020). The lack of women’s participation creates a vicious cycle whereby women increasingly feel excluded from CRB governance and so remain unaware of the relevance of the group to their lives, leading to further disengagement from CRB activities.

The DNPW oversees the wildlife sector and employs 1,254 wildlife police officers to help enforce forestry and wildlife regulations (personal communication, DNPW, October 4, 2022). Local conservation NGOs also employ 1,402 community wildlife scouts to help patrol protected areas (personal communication, DNPW, October 4, 2022). In rural parts of the country where employment opportunities are scarce, community scouts are an important job opportunity for young men and women. Yet women face social and structural barriers to access employment opportunities as community scouts (Malasha, 2021). As of 2018, just 11 percent of community scouts were women (personal communication, conservation NGOs, January 30, 2019). Given that high performing community scouts are often elevated to long-term government jobs as wildlife police officers, this pipeline challenge makes it difficult for women to get hired by the DNPW. Furthermore, the wildlife law enforcement sector—and the law enforcement sector as a whole—has long been criticized for being hostile to women’s participation, as it is highly militarized, reinforcing the masculinization of the sector (Seager et al., 2021).

This paper describes structural and norms-based gender barriers within the CBNRM governance and law enforcement structures in Zambia based on qualitative and quantitative data. It then outlines interventions to support women’s economic empowerment undertaken by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in partnership with the DNPW, international and local NGOs, and the communities themselves across Zambia between 2018 and 2022.

2. Intervention context – Barriers to effective participation

Malasha and Duncan’s (2020) baseline gender assessment – which included a literature review, focus group discussions and key informant interviews – identified a number of structural, social and gender norms barriers that prevent women from entering and effectively participating in the wildlife and natural resource sectors in Zambia.

Within community governance institutions, structures are generally gender blind, as procedures for carrying out elections do not explicitly include or exclude women (Malasha, 2020). CRB terms last for three years, and elections are often carried out in a rush towards the end of a term. As a result, little attention and resources are available to fund well-run and inclusive elections. Since CRB positions are responsible for community benefit sharing, have a role in employing community scouts and are one of the few formal power structures in rural areas, they are highly coveted. Candidates with personal resources to spend on elections are at a considerable advantage, as buying food and drinks for perspective voters is a common practice (Malasha and Duncan, 2020). This practice disadvantages women, even from wealthier households, who typically have less decision-making power and access to financial resources at the household level (World Bank, 2012; Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2015).

There are equally strong structural barriers that prevent women from becoming community scouts. Rules governing the selection process for scout candidates are often gender blind, which can inadvertently discriminate against women. For instance, community scouts must have a Grade 12 certificate and are often required to pass a physical fitness test that includes running in heavy boots and backpacks, physical tasks which women are less likely to have experience with than men (Malasha and Duncan, 2020). The Grade 12 certificate, a seemingly gender-neutral requirement, also acts as a barrier to women’s participation, as women are less likely to have graduated from high school than men — Zambia’s secondary gender parity index was 0.84 in 2015 (Central Statistical Office of Zambia, 2016). Once selected, training approaches for scouts are typically one-size-fits-all, focused on eliminating low performers rather than building up the capacity of nascent recruits (Malasha, 2021).

In addition to structural barriers, women face social norms and cultural barriers that inhibit their participation. Gender norms and stereotypes in Zambia dictate that are men are seen as decision makers in both the home and public spaces, while women oversee family care and household chores (Malasha and Duncan, 2020). Women’s care responsibilities limit the time they have available to attend community governance meetings, which impacts women’s knowledge about natural resource management issues. Furthermore, even when women are in attendance, women interviewed for the gender assessment reported that their views are often ignored (Malasha and Duncan, 2020). Some women said they were not comfortable speaking up in large mixed gender public settings. Culturally, leadership roles, including wildlife law enforcement, are men’s domain (Malasha and Duncan, 2020; Seager et al., 2021). Thus, when women choose to step outside of prescriptive gender norms and run for CRB office or enter wildlife scout employment, they often face push back from family members, their community, and the institutions in which they work (Bessa et al., 2021).

These gender norms are particularly challenging for wildlife scouts to navigate. USAID conducted focus group discussions with 10 newly recruited young women scouts and five new women CRB members during their first year of service. Scout recruits are typically young women, at an age when traditionally women in Zambia get married and start having children. Thus, these young women are breaking the mold by entering formal employment. Interviews with women scouts revealed that while their families may appreciate the income they bring home, they often face backlash—accused of neglecting their familial duties and jeopardizing their chances of marriage (Bessa et al., 2021). Married women scouts report that they often face pushback from their husbands, who may resent their wife for earning income, leaving childrearing and home responsibilities to them, and spending weeks in the field with other men. Even while out on patrol, women say they are frequently relegated to supporting roles, expected to cook, clean, and guard camp, as opposed to going on patrols, or given unrealistic tasks to prove they are not cut out for the work (Bessa et al., 2021). NGOs and government extension officers often cite these threats of backlash as reasons to avoid hiring women as scouts. Thus, harmful gender norms are used as an excuse to perpetuate gender inequality.

Women scouts interviewed also reported incidences of gender-based violence (GBV) from intimate partners. Some said their spouses have accused them of infidelity or seized their wages (Bessa et al., 2021). A few scouts also faced threats of physical or verbal harassment from community members for taking on men’s roles. Women scouts reported instances of harassment and sexual coercion at work, where supervisors made non-consensual sexual advances to junior women staff and threatened retaliation against women who did not comply (Bessa et al., 2021). Only in recent years has the sector begun to acknowledge and pay attention to GBV risks, rather than simply discouraging women from entering the discipline.

Despite these barriers and risks, women are eager to participate in the sector, recognizing the potential benefits, as well as the risks, of stepping outside of traditional gender roles. At the same time, there is a need to build support from within their families and communities (Malasha and Duncan, 2020). When women have greater decision-making power in natural resource management, their interests are more likely to be considered (Ngece, 2006; Giesecke, 2012; FAO, 2018). Women’s participation increases their income earning potential, either through formal employment as wildlife scouts or benefit sharing from CRB roles. When women earn more money, they prioritize family education, health and nutrition spending, increasing household wellbeing (Smith and Haddad, 2000; Armand et al., 2020; Booysen and Guvuriro, 2021). Involving women in natural resource governance and enforcement also increases the adoption of sustainable practices, crucial in both adapting to and mitigating the growing threat of climate change (Agarwal, 2009; Mwangi et al., 2011; Leisher et al., 2016; Beaujon Marin and Kuriakose, 2017).

3. Project description

Based on the findings from the gender assessment, USAID identified two entry points for women’s meaningful engagement in wildlife management: formal employment as community scouts and leadership roles as CRB members. USAID aimed to enhance effective participation in these areas by addressing structural barriers and gender norms to entry, as well as building women’s capacity for success once they are in the roles. To address CRB capacity, in 2020, in partnership with NGO partner Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS), the Zambia CRB Association and DNPW, USAID piloted gender inclusive elections in four chiefdoms surrounding North Luangwa National Park — Chifunda, Chikwa, Mukungule, and Nabwalya (Malasha, 2020). To address wildlife employment opportunities, USAID worked with DNPW and another NGO partner, Conservation Lower Zambezi, to recruit and train a cohort of all-women community scouts, alongside mixed-gender community scout groups from across the country. Pre-recruitment sensitization efforts took place ahead of formal recruitment, followed by a three-month residential training program at Chunga Wildlife Training Centre in Kafue National Park, after which scouts were posted at their new jobs. Details on the specific programmatic elements undertaken are described below.

3.1. Laying the groundwork

3.1.1. Carry out a gender assessment

The gender assessment allowed USAID to identify barriers to women’s participation and target approaches to different stakeholders. Most importantly, it created an evidence base for discussing the activities with government and NGO counterparts, as well as identifying individuals who might be resistant to the work and those who could act as potential champions. Some of the outcomes of the assessment are described above and have fed into adaptive management.

3.1.2. Work through champions

Because gender norms are rooted in existing social power dynamics, at the beginning of the project USAID identified champions at different levels and invested in them to lead gender dialogues and influence norms change within their spheres of influence. Traditional leaders, who hold hereditary positions, are charged with carrying out administrative functions under Zambia’s customary governance system and are the custodians of cultural norms and practices. They were a primary target for gender champions work, based on their influential role in communities. The other group of champions targeted were community facilitators from partner NGOs who had worked in the communities for years and built-up trust and respect. These champions engaged with influential individuals in communities who were resistant to the work in the hopes of shifting their position over time.

3.2. Recruiting women to participate

Before USAID interventions, both scout recruitment and elections were gender-blind. But in practice, there were many steps that prevented women from stepping forward initially and engaging effectively. To address these barriers, USAID mobilized teams of conservation experts with a gender focus to support the scout recruitment and CRB election through the following steps.

3.2.1. Increase awareness

The team focused on increasing awareness of open opportunities. Because women have smaller social networks than men and have been traditionally excluded from public roles, they often do not know when job recruitments occur. Staff made concerted outreach efforts to women’s and religious groups and targeted training centers, clinics and water access points where women are more present. For elections, community sensitization meetings were held with women, men, and traditional leaders to explain the election process and help potential women candidates navigate the required steps. Based on discussions with community and traditional leaders, traditional leaders proactively reached out to families where women had limited support to answer questions and encourage men to support women’s candidacies.

3.2.2. Consider quotas carefully

To advance recruitment of women community scouts, USAID considered the advantages and risks of using quotas and targets to reach women. USAID partnered with Conservation Lower Zambezi, who had already committed to mobilize an all-women scout team. Since scout trainings commonly bring together multiple CRBs and NGOs, USAID agreed to subsidize the participation of women from other partner organizations to train a cohort of equal numbers of men and women. USAID supported Chunga Training Centre to adopt gender-responsive approaches in the delivery of training and all women managed to graduate (Malasha, 2021).

While no government mandated gender quotas exist for CRBs, four traditional leaders worked with FZS to adopt affirmative action policies to build support for women’s participation in CRB elections. Some chiefs were supportive, but only encouraged their subjects to participate, while one went further and implemented a 50 percent gender quota for the 10 person CRB. While quotas were helpful in increasing women candidate’s participation, they did not guarantee elected women were able to meaningfully engage in the work (Malasha, 2021).

3.2.3. Revisit pre-requisites

USAID worked with partners and DNPW to revisit the pre-requisites for recruitment that often make it difficult for women to compete fairly with men. Many pre-requisites for scout recruitment act as a barrier for women’s participation, such as a Grade 12 certificate or physical endurance and fitness tests that are designed for men. The tests are not based on the minimum fitness or knowledge required to perform the job, for example by allowing all who complete the test within the time limit to proceed, but rather allow the fastest individuals to move forward to the next step. Continued dialogue with government and NGOs is required to further revise the pre-requisites for community scouts, as there is still a strong push for an educational requirement because it allows individuals to advance to a Wildlife Police Officer position. By law, there are no educational requirements for CRB members, a fact that was stressed during public meetings with potential women candidates and community members, as a lack of education and literacy had been used to discourage women from participating in the past (Malasha, 2021).

3.2.4. Help women prepare for candidacy

In order to reduce information and resource barriers that prevent women from being successful candidates, USAID identified cohorts of women interested in elections and helped prepare them physically and mentally in the weeks prior to the election. USAID and partners helped women candidates develop campaign strategies and practice public speaking skills. Women were encouraged to tailor campaign messages to their local context and build on their own personal strengths, rather than simply mimicking the approaches commonly taken by men. This cohort preparation model created a support structure for women candidates and helped ensure there was a critical mass of skilled women to stand for election. For scout recruits, USAID’s partners outlined the physical fitness requirements for women ahead of time so they were able to practice and support women with gender sessions throughout to empower them to overcome challenges faced during training.

3.2.5. Ongoing community gender dialogue

Building on the entry level discussions with chiefs, community members were engaged early on to help them understand the goals of women’s empowerment in the CRB election process and identify potential champions who could sway resistant members to accept women as leaders of their CRBs. Shifting gender norms is challenging and takes time, hence continued engagement with traditional leaders, community members, and women candidates, particularly through champions, is critical to encourage women’s participation and garner community buy-in.

3.3. Supporting women in their new roles

Increasing women’s representation in these leadership bodies is an important first step, but the program also provided follow-on support to ensure women were able to meaningfully participate in their new organizations. This included further orientation and training on their roles, establishing support networks for new recruits, and working to adapt institutional policies and structures within supporting NGOs and government agencies to better enable women’s participation.

3.3.1. Revisit curriculum

Once selected for their new roles, scouts go through a three-month intensive field training program. At the request of Chunga Wildlife Training Centre, USAID supported an evaluation of the three-month curriculum to better address the needs of women in the training program. The curriculum now includes a gender module that discusses gender equality, gender norms, and GBV risks. USAID also provided training to the center’s instructors to increase their capacity to carry out gender integration. USAID is also providing training and capacity building support to the DNPW to ensure gender integration is included in longer-term department training and support for community scouts.

3.3.2. Orient women on job entry

USAID promoted a gender-responsive CRB orientation to build members’ understanding of position requirements and emphasize the equal role of women and men on the committee. CRBs rarely receive comprehensive introductions to their roles and responsibilities, which often leads to the sidelining of women members, who may be first time candidates and less aware of their duties and rights within the organization, or less willing to speak up in public settings due to engrained gender norms (Malasha, 2021). Spouses of women CRB members were also invited to the orientation to help them understand the roles of women in the institution.

3.3.3. Establish support networks

Newly elected women CRB members and community scouts can become isolated, as they are often the only woman, or one of a handful of women, within these institutions. Establishing support networks and creating spaces for women to come together is therefore important. The all-women scout unit provides a built-in support network for new recruits. Women work in this unit for a period of time, after which they can apply for a position in a specialized unit. This approach provides a support structure for young women to develop skills and build confidence as they enter the field, but does not permanently isolate them within a separate structure. While wildlife law enforcement is male-dominated, Lower Zambezi National Park, where the all-women unit works, has one of Zambia’s highest ranking woman wardens, who plays an ongoing mentorship role with the new recruits.

3.3.4. Build institutional capacity to support long-term change

USAID also focused on building the capacity of the organizations that support scouts and CRBs. By training DNPW, NGO and associated staff who work directly with communities, partners gained technical skills and knowledge to advance women’s leadership and economic empowerment within communities and their respective areas of operation. USAID developed a training of trainer’s course on women’s leadership and empowerment, designed to be integrated into existing extension programs. During the training, conservation organization staff were trained to deliver a 12-module course that builds women’s confidence and assertiveness and their capacity to combat gender norms, communicate effectively, and effectively lead other women and men within their organizations. Conservation organizations are now using these materials to mobilize candidates and train women leaders in village action groups and CRBs. The training brings together individuals from across the country, building a community of practice and common language around gender integration in the wildlife space.

3.4. Combating gender-based violence

When women step outside traditional gender norms to enter a male-dominated field, the risk of GBV increases. To mitigate this risk, USAID invested in ongoing community dialogues about gender norms, developed materials and tools for implementing partners, and trained supervisors on GBV risks and mitigation measures. But sector wide shifts require additional top-down engagement and reform. USAID partnered with the Gender Division in the Vice President’s Office to raise awareness on gender and GBV issues within the DNPW. USAID documented evidence of GBV in the wildlife sector and is helping conservation NGOs examine what they can do to effectively respond to and mitigate risks of GBV, while also identifying referral pathways for GBV service providers in the communities they work.

4. Data collection

Data for the following sections comes from formal and informal interviews with the participants in the above processes. Election data was collected during the gender-responsive CRB election process, with local staff recording the number of women and men who ran for a position, as well as those who were elected to both village action groups and CRBs. Project staff then conducted follow up interviews with women and men CRB members at least six months after they were elected. For community scouts, data on the number of women and men scout recruits comes from DNPW. Follow up interviews were also conducted with women scouts six months and one year after completing the training course. Views shared were recorded anonymously to encourage candor.

5. Results

5.1. CRB Elections

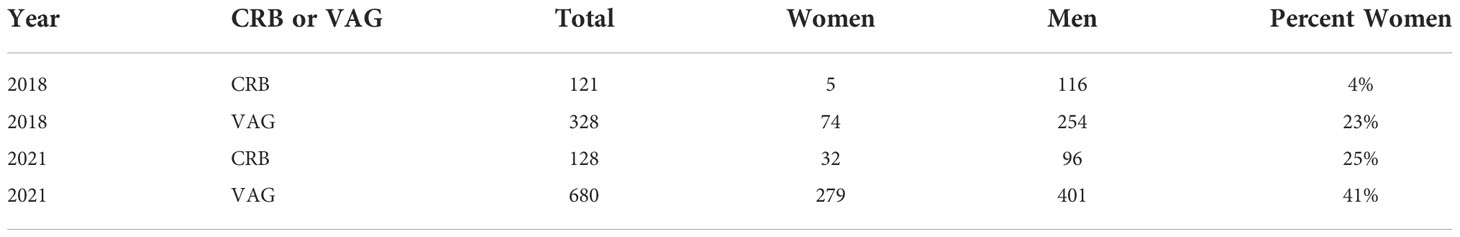

During the first phase of gender-responsive CRB election pilots, 52 percent of potential candidates across the four chiefdoms were women (Malasha, 2020). Women now hold one in four CRB seats in these communities—up from four percent in 2018—and some hold leadership positions such as chairperson, vice-chairperson, or secretary. Village Action Groups (VAGs) in these communities, which support the work of the CRBs, saw women’s participation increase from 23 percent to 41 percent (see Table 1).

The gender-responsive election approach has subsequently been adopted by 12 additional NGOs, who have carried out pre-election sensitization and training in 21 new GMAs since 2020. 16 NGOs have been trained to deliver the women’s leadership and empowerment training and are integrating these approaches into their work with women leaders in communities.

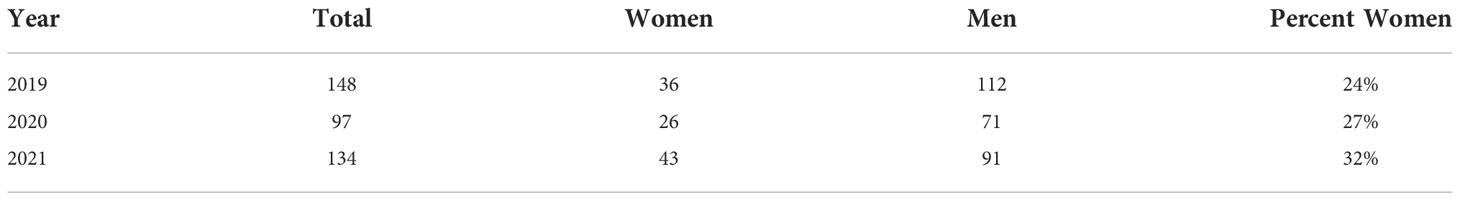

5.2. Wildlife scout recruitment

Under the gender-responsive wildlife scout recruitment process, DNPW recruited a scout training class of 45 men and 45 women, the most inclusive cohort in the history of the scout training school. The cohort of women recruits supported one another through the grueling and physically demanding three-month training program. This critical mass of women recruits pushed the school to examine their own processes, curriculum, and requirements. Subsequent classes have also included a larger share of women than in the past, demonstrating a relatively quick shift in recruitment practices and acceptance of women as wildlife scout recruits (see Table 2).

Upon graduation, 10 scouts were selected for Zambia’s first all-women patrol unit in Lower Zambezi National Park. These women scouts are performing the same tasks as their men counterparts. While many still receive push back for stepping outside traditional gender norms, they now have well-respected jobs and a stable source of income to support themselves and have become role models in their communities.

Law enforcement is still a men-dominated sector, and women scouts have to navigate pushback from within families, communities, and the institutions they serve. In some cases, this resistance has escalated to instances of GBV (Bessa et al., 2021).

6. Discussion

Over the past four years, USAID has worked with DNPW, conservation NGOs, and local partners to implement the suite of activities outlined above to increase women’s participation in the wildlife sector in Zambia. The effort has achieved notable successes, dramatically increasing the number of women elected to CRBs and expanding the number of women scout recruits through approaches that improve their experiences and reduce risks. But shifting gender norms takes time, and the program has learned and adapted from the challenges it faced.

6.1. Successes

Two key elements enabled program success. First, the gender analysis was an important first step to contextualize the challenges preventing women from fully participating in the wildlife sector. The analysis identified elected governance and wildlife scout positions as areas for potential impact that were accessible to many rural women. It also revealed the risks associated with gender equality interventions, particularly related to GBV. Socializing these analyses was crucial to gain buy-in and interest from government, NGOs and traditional leaders.

Second, the program engaged and cultivated local leaders with social influence and power as project champions early on. In the early stages of work, these champions helped advocate for women’s participation, making it clear to community members that they supported and encouraged women’s inclusion in CRB elections and scout recruitment efforts. In the longer-term, champions create a mechanism for scaling by leveraging their networks and broader influence. Providing champions with additional resources and connections to better leverage existing resources can help build long-term support for gender norms shifts.

The willingness of government and NGOs to acknowledge GBV risks within the sector and take proactive steps to address them was remarkable and it is worth sharing more broadly. Multiple NGOs have identified pathways to examine GBV risks within their operations and the communities they support. Long term, this will help create a more inclusive environment that supports women’s participation and safety.

The USAID package of approaches was deployed through multiple partners in different locations across Zambia. While there was a critical mass of activities around women’s leadership and empowerment in elections within the North Luangwa ecosystem and around community scout recruitment and training in the Lower Zambezi ecosystem, the diversity of approaches and partners makes a full evaluation of impacts challenging. The breadth of organizations involved in this effort, however, is extremely encouraging, and the women’s leadership and empowerment training of trainers cohort has become a strong platform for social inclusion within Zambia’s conservation sector.

Each of the approaches implemented received a generally positive review by community members, traditional leadership, NGOs and government alike. Most importantly, the individual women expressed gratitude that their aspirations and capacity development were kept paramount in all activities. These women were able to push beyond traditional gender norms in their communities, acknowledging the risks but also eager to seize new opportunities for themselves (Malasha, 2020).

6.2. Challenges

Despite these successes, increasing women’s participation in the male-dominated wildlife and natural resource sectors is challenging.

6.2.1. Pushback from the community and some stakeholders

The use of quotas or targets can be an effective way to increase women’s representation within the labor market and in decision-making bodies (Beaman et al., 2009; Beaman et al., 2010; Pande and Ford, 2011). But quotas can be less effective at achieving improved outcomes when there are perceived to be few viable women candidates (Profeta, 2017). While quotas were effective in wildlife scout recruitment, CRB based quotas often faced pushback from community members, who felt they were used to force out qualified men in favor of less qualified women. USAID and its partners are moving beyond a simple quota-based metric of success and instead focusing on the quality of engagement.

Both women CRB members and wildlife scouts have faced persistent community resistance to women in leadership roles, at times escalating GBV. This pushback has come from both men and women. This illustrates the long-term nature of efforts to change gender norms. Yet the support of some progressive chiefs and village headpersons is creating shifts in acceptance, and as more women are seen in these positions of authority, increased community acceptance may follow.

Efforts to increase women’s participation received opposition from some key stakeholders, especially within government partners. These individuals were wary of discussions of gender equality, arguing it would disturb the status quo and could reveal other weaknesses within the department, such as a lack of transparency in managing resources and related revenues. Given the structure of the wildlife industry in Zambia, the DNPW is a key stakeholder whose buy-in and support is necessary to take these initiatives beyond initial pilot communities.

6.2.2. Limited capacity of NGOs to respond

Though many organizations were willing to promote inclusive approaches, they have limited institutional capacity to advance gender integration or address GBV. Concerns over the cost and time associated with effective gender integration remains a consistent challenge cited by partners. Pre-election and recruitment support for women candidates requires advanced planning and staff resources. While many of these activities could be built into standard, year-round work plans, leveraging other travel/meetings to reduce costs, in practice these efforts are still viewed as a one-off project.

7. Conclusions and the way forward

The approaches taken in Zambia could be adapted to community-based natural resource management frameworks in other countries, as the structural and gender norms barriers that restrict women’s participation in natural resource sector are present globally. By building a cadre of gender champions and addressing underlying gender norms, in addition to improving recruitment and training practices, USAID hopes the transformations seen in the wildlife sector in Zambia will last beyond the time frame of the project and contribute to lasting change in the sector.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the drafting and revision of the manuscript and have read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This case study discussed in this paper is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and implemented by Tetra Tech through the Integrated Land and Resource Governance (ILRG) task order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights II (STARR II) Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contract.

Conflict of interest

Authors MS, TB, PM and MD were employed by the company Tetra Tech.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agarwal B. (2009). Gender and forest conservation: The impact of women’s participation in community forest governance. Ecol. Economics 68 (11), 2785–2799. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.04.025

Agrawal A., Gibson C. (1999). Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 27 (4), 629–649. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00161-2

Armand A., Attanasio O., Carneiro P., Lechene V. (2020). The effect of gender-targeted conditional cash transfers on household expenditures: evidence from a randomized experiment. Economic J. 130 (631), 1875–1897. doi: 10.1093/ej/ueaa056

Barnes G., Child B. (2014). “Elite capture: a comparative case study of meso-level governance in four southern Africa countries,” in Adaptive cross-scalar governance of natural resources (London: Routledge).

Beaman L., Chattopadhyay R., Duflo E., Pande R., Topalova P. (2009). Powerful women: Does exposure reduce bias? Q. J. Economics 124 (4), 1497–1540. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2009.124.4.1497

Beaman L., Duflo E., Pande R., Topalova P. (2010). Political reservation and substantive representation: Evidence from Indian village councils (Washington, D.C. and New Delhi, India Policy Forum, Brookings and NCAER).

Beaujon Marin A., Kuriakose A. T. (2017). Gender and sustainable forest management: Entry points for design and implementation (Washington, DC: Climate Investment Funds).

Bessa T., Malasha P., Sommerville M., Mesfin Z. (2021). Gender-based violence in the natural resource sector in Zambia (Washington, D.C., USAID Integrated Land and Resource Governance Task Order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights II (STARR II) IDIQ).

Booysen F., Guvuriro S. (2021). Gender differences in intra-household financial decision-making: An application of coarsened exact matching. J. Risk Financial Manage. 14(10), 469. doi: 10.3390/jrfm14100469

Demirguc-Kunt A., Klapper L., Singer D., Van Oudheusden P. (2015). The global findex database 2014: Measuring financial inclusion around the world (Washington, D.C., World Bank Policy Research Working Paper), 7255.

Flintan F., Tedla S. (2007). Gender and social issues in natural resource management research for development (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Organization for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa).

Giesecke C. (2012). ‘Gender and forest management, research issues (Washington, DC: USAID Knowledge Services Center).

Leisher C., Temsah G., Booker F., Day M., Samberg L., Prosnitz D., et al. (2016). Does the gender composition of forest and fisher management groups affect resource governance and conservation outcomes? a systematic map. Environ. Evidence 5 (6), 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13750-016-0057-8

Lindsey P. A., Nyirenda V. R., Barnes J. I., Becker M. S., McRobb R., Tambling C. J., et al. (2014). Underperformance of African protected area networks and the case for new conservation models: Insights from Zambia. PLos One 9 (5), e94109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094109

Malasha P. (2020). Increasing women’s participation in community natural resource governance in Zambia (Washington, DC: USAID Integrated Land and Resource Governance Task Order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights II (STARR II) IDIQ).

Malasha P. (2021). Breaking down employment barriers in Zambia: Increasing opportunities for female community scouts (Washington, D.C., LandLinks Blog).

Malasha P., Duncan J. (2020). Gender assessment of the wildlife sector in Zambia (Washington, D.C., USAID Integrated Land and Resource Governance Task Order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights II (STARR II) IDIQ).

Musgrave M. K., Wong S. (2016). Towards a more nuanced theory of elite capture in development projects. the importance of context and theories of power. J. Sustain. Dev. 9 (3), 87–103. doi: 10.5539/jsd.v9n3p87

Mwangi E., Meizen-Dick R., Sun Y. (2011). Gender and sustainable forest management in East Africa and Latin America. Ecol. Soc. 16 (1), 17. doi: 10.5751/ES-03873-160117

Ngece K. (2006). The role of women in natural resource management in Kenya (Nairobi: The Royal Tropical Institute).

Pande R., Ford D. (2011). “Gender quotas and female leadership,” in World bank world development report 2012 background paper. (Washinton, D.C., World Bank)

Seager J., Bowser G., Dutta A. (2021). Where are the women? towards gender equality in the ranger workforce. Parks Stewardship Forum 37 (1), 206–218. doi: 10.5070/P537151751

Smith L., Haddad L. (2000). Explaining child malnutrition in developing countries. a cross-countyr analysis (Washinton, D.C., International Food Policy Research Institute Research Report), 111.

Sommerville M., Jones J. P. G., Rahajaharison M., Milner-Gulland E. J. (2010). The role of fairness and benefit distribution in community-based payment for environmental services interventions: A case study from menabe, Madagascar. Ecol. Economics 69 (6), 1262–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.005

Watson F. G., Becker M. S., Milanzi J., Nyirenda M. (2015). Human encroachment into protected area networks in Zambia: implications for large carnivore conservation. Regional Environ. Change 15), 415–429. doi: 10.1007/s10113-014-0629-5

Keywords: wildlife, gender, Zambia, natural resource governance, women’s empowerment, community governance

Citation: Sommerville M, Bessa T, Malasha P and Dooley M (2022) Increasing women’s participation in wildlife governance in Zambia. Front. Conserv. Sci. 3:1003095. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2022.1003095

Received: 25 July 2022; Accepted: 15 November 2022;

Published: 06 December 2022.

Edited by:

Susan (Sue) Snyman, African Leadership University, RwandaReviewed by:

Bridget Bwalya Umar, University of Zambia, ZambiaJessica Bell Rizzolo, The Ohio State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Sommerville, Bessa, Malasha and Dooley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matt Sommerville, bWF0dC5zb21tZXJ2aWxsZUB0ZXRyYXRlY2guY29t

Matt Sommerville*

Matt Sommerville* Meagan Dooley

Meagan Dooley