94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Conserv. Sci., 23 June 2021

Sec. Human-Wildlife Interactions

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.683356

This article is part of the Research TopicUnderstanding Coexistence with WildlifeView all 17 articles

Long histories of sharing space and resources have built complex, robust, and enduring relationships between humans and wildlife in many communities across the world. In order to understand what makes it possible for humans and wildlife to share space, we have to look beyond the ecological and socio-economic study of damages caused by human-wildlife conflict and explore the cultural and societal context within which co-existence is embedded. We conducted an exploratory study on the institution of Waghoba, a big cat deity worshiped by the Indigenous Warli community in Maharashtra, India. Through our research, we found that the worship of Waghoba is highly prevalent, with 150 shrines dedicated to this deity across our study site. We also learnt that the Warlis believe in a reciprocal relationship, where Waghoba will protect them from the negative impacts of sharing spaces with big cats if the people worship the deity and conduct the required rituals, especially the annual festival of Waghbaras. We propose that such relationships facilitate the sharing spaces between humans and leopards that live in the landscape. The study also revealed the ways in which the range of institutions and stakeholders in the landscape shape the institution of Waghoba and thereby contribute to the human-leopard relationship in the landscape. This is relevant for present-day wildlife conservation because such traditional institutions are likely to act as tolerance-building mechanisms embedded within the local cosmology. Further, it is vital that the dominant stakeholders outside of the Warli community (such as the Forest Department, conservation biologists, and other non-Warli residents who interact with leopards) are informed about and sensitive to these cultural representations because it is not just the biological animal that the Warlis predominantly deal with.

Human-wildlife conflict emerged as a field of study within conservation research and practice in the 1990s and has since been developing (Woodroffe et al., 2005; Redpath et al., 2015; Pooley et al., 2017; Bhatia et al., 2019). Research pertaining to the study of ecology, diet, geography, distribution of attacks, and mitigation practices associated with the “conflictual” wildlife species dominated the treatment of the issue, often centered in and around protected areas (Edgaonkar and Chellam, 2002; Andheria et al., 2007; Athreya et al., 2013, 2016; Kshettry et al., 2017). Over time, the field of study has expanded, not only geographically to look at human-wildlife interactions in multi-use landscapes, cities, and other non-protected areas (Athreya et al., 2013; Chapron et al., 2014; Carter and Linnell, 2016; Landy, 2017; Miller et al., 2017; Dhee et al., 2019), but also ideologically to include the study of the numerous dimensions associated with human-wildlife interactions (Ghosal et al., 2013; Aiyadurai, 2016; Crown and Doubleday, 2017; Doubleday, 2017; Bhatia et al., 2019; Nijhawan and Mihu, 2020).

There has progressively been a recognition that these conflictual interactions are far more complex and constitute only a portion of the multiple types of interactions that exist between humans and wildlife (Kolipaka et al., 2015; Carter and Linnell, 2016; Crown and Doubleday, 2017; Linnell et al., 2020). Furthermore, there is also a steadily growing body of research that seeks to understand the social, anthropological, political, inter-institutional, cultural, psychological, and other human factors that shape human-wildlife interactions (Redpath et al., 2015; Landy, 2017; Pooley et al., 2017; Bhatia et al., 2019).

Even though the study of human-wildlife interactions has been a relatively recent development within the conservation literature, it is by no means a novel subject matter to the innumerable societies across the world who have been sharing space with animals for centuries (Ingold, 2000; Messmer, 2000; Bhatia et al., 2019). Consequent to the long histories of cohabiting landscapes with wildlife, all societies have attempted to make sense of their interactions with other species and manage the consequences that these interactions produce (Ghosal, 2013). Societies across the world conceptualize nature and animals in a multitude of ways (Descola, 1992; Gadgil et al., 1993; Descola and Pálsson, 1996; Ingold, 2000; Goldman et al., 2010; Jalais, 2014; Aiyadurai, 2016; Dhee et al., 2019) making it imperative to understand them through their local reality, context and worldview. In some communities, narratives and knowledge surrounding human-wildlife interactions can also be seen entwined into informal social institutions. For example, in Dibang Valley the kinship ties of brotherhood and taboos describing the ill consequence of killing a tiger contribute significantly to the relationship between humans and tigers in that landscape (see Aiyadurai, 2016; Nijhawan and Mihu, 2020).

The Warlis, an Indigenous community from North-western Maharashtra, have, for centuries, shared spaces with big cats. This landscape has been home to leopards (Panthera pardus fusca) and historically even tigers (Panthera tigris tigris). The Warlis worship a big cat deity called “Waghoba.” In this study, we carried out an ethnographic inquiry that explores the emergent themes in oral histories, narratives of worship, power structures, and belief systems. Our aim was to understand narratives related to Waghoba and the negotiation of shared spaces in relation to big cats in multi-use landscapes i.e., a mosaic of agricultural, industrial and forested landscapes. Social institutions can be understood as an enduring set of ideas, beliefs and practices that function to satisfy various human needs (Johnson, 2000). They may be formal such as the state, prisons, schools or informal institutions such as political ideology, cultural norms, belief systems, etc., and form an interrelated system of social norms and roles by people united for a common goal (Abercrombie et al., 1994). Previously, other studies have established the link between large cats and Waghoba in other parts of Maharashtra (Ghosal and Kjosavik, 2015; Pimpale, 2015, Athreya et al., 2018). In this study we considered not only the deity but the “social institution of Waghoba” as the subject, exploring the multilayered and interrelated features of Waghoba worship and people-leopard relations including facets of religion, politics, and kinship.

Scholars in the past have described the Warlis as animists (Save, 1945; Dandekar, 2005). However, there is growing recognition in academia about the immense heterogeneity in indigenous cosmologies across the world, and how they often cannot be encapsulated into the pre-existing frameworks of animism and totemism. Århem (2016) discusses the ways in which South Asian animism is particularly distinct from Amerindian animism, and the need to decolonize our perspective in order to recognize the existence of various cosmologies. Therefore, in an attempt to broaden the way we interpret and understand the cosmologies we encounter, in this paper we have chosen not to restrict ourselves to using pre-existing animistic frameworks as the only way to understand Warli cosmology.

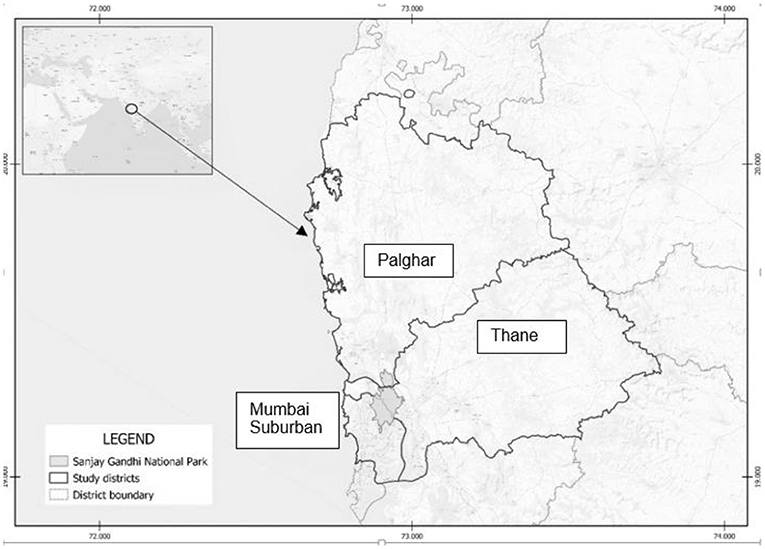

Fieldwork for this study was conducted in both multi-use landscapes and protected areas. These include hamlets and villages in parts of the Mumbai Suburban (446 km2), Thane (4,214 km2), and Palghar (5,344 km2) districts located toward the north-west of Maharashtra, India (Maharashtra Government, 2018) (Figure 1). These regions encompass the northern hills of the Western Ghats and Maharashtra's western coastal plains bordering the Arabian Sea.

Figure 1. The study was conducted in parts of the districts Palghar, Thane, and Mumbai Suburban in Maharashtra, India. Map credits: Shweta Shivakumar.

The climate in these regions is tropical, humid, and warm. These regions support both agricultural as well as small and large-scale business industries such as textile, chemicals and steel. Protected areas included within our study site are Sanjay Gandhi National Park (103 km2), Tungareshwar Wildlife Sanctuary (85 km2), and Tansa Wildlife Sanctuary (320 km2) (Maharashtra Forest Department, 2021). Mammalian species such as the leopard, jungle cat (Felis chaus), spotted deer (Axis axis), barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak), sambar (Rusa unicolor), common langur (Semnopithecus entellus), and black-naped hare (Lepus nigricollis) have been recorded here (Maharashtra Forest Department, 2021).

Anecdotal evidence, government records, and media reports indicate both the historical presence of tigers (with recent sightings of an individual from 2003) and the current presence of leopards in the landscape (Anonymous, 1882; Bhagat, 2010). Records indicate that the Warli community have historically been inhabitants of the presently identified regions of Mumbai Suburban, Thane, and Palghar districts (Save, 1945). Our study area was chosen based on the prior knowledge that both Warlis and big cats are present in this region.

The Mahadeo Kolis, Malhar Kolis, Thakkers, and Dublas are other smaller (population wise) indigenous groups in the vicinity that also worship some deities of the Warli pantheon, including Waghoba. However, for this study, we chose to focus on this institution among the Warlis. We found that the Warlis are the most abundant of the groups mentioned above that share the landscape, giving us a larger group of people to engage with while also allowing our initial inquiry to be focused on one community.

Ethnographic approaches are increasingly being employed to study the diversity of human-wildlife relations, particularly in the context of conservation (Goldman et al., 2013; Khumalo and Yung, 2015; Aisher and Damodaran, 2016; Aiyadurai, 2016; Vasan, 2018). Ethnography allows for an exploration into the narratives, myths, stories, traditions, practices, and lived experiences of a group or community and how these shape people's beliefs and attitudes concerning the area of inquiry. Through the use of in-depth unstructured or semi-structured interviews, group discussions, and participant observation, an ethnography can produce rich qualitative data (Bernard, 2017; Vasan, 2018). Hence, we chose this approach to study the social institution of Waghoba among the Warlis of north-western Maharashtra.

Our study was a short-term ethnography (Pink and Morgan, 2013) (as opposed to a traditional in-depth long-term ethnography typically spanning over 6 months in the field), which comes with acknowledging the unfeasibility of getting a complete and detailed understanding of the subject matter. Like all such studies, this paper reflects our understanding and interpretation of these cultural systems.

For this study, RN (the first author of this paper) conducted fieldwork for 6 months (November 2018 to April 2019) with the assistance of OP, wherein they spent several days each month living in the study site to build trust and social connections among the communities and traveled to document Waghoba shrines. Interviews and participant observation were conducted concurrently with the documentation activity. Informed oral consent was obtained from every participant before conducting interviews and obtained from community members for the researchers to participate in, observe and document traditional practices. Three main methods were employed to collect data for this study; the documentation of Waghoba shrines, semi-structured interviews, and participant observation. This study's ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at WCS-India (Project no. 2018/6).

Even though previous studies, as well as anthropological and historical records, have documented the existence of a big-cat deity called Waghoba that is worshiped by Warlis and other Indigenous communities in Maharashtra, they do not provide a clear understanding of its current widespread prevalence and prominence (Ghosal and Kjosavik, 2015; Pimpale, 2015; Athreya et al., 2018). In order to explore the geographical spread of the belief in Waghoba and understand its iconography and physical characteristics, we documented Waghoba shrines throughout the study area.

The initial Waghoba shrines that we documented were identified based on prior knowledge and snowball sampling in the area. Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP) has been known to be home to one of the world's highest population densities of leopards (Surve and Ahmed, 2017). Both SGNP and the adjoining Aarey Milk Colony contain multiple hamlets of Warli residents. We began fieldwork here and expanded north toward the Maharashtra-Gujarat border via National Highway 48 (NH48). Over the period of fieldwork (November 2018 to April 2019) we traveled ~2,125 km through Dahanu, Palghar, Talasari, Boisar, Vasai, Wada, and Jawhar regions, all known to have resident Warli communities.

In many cases, a shrine may not evidently belong to Waghoba, as many deities in the region (including Waghoba) have shrines which appear the same to an outsider i.e., sacred stones covered in vermillion paste. Therefore, we always consulted with nearby residents, shamans or elders to ensure correct identification of the shrine. We also asked questions about how old the shrines were, how they were made, who visited them, and how often. The GPS location of each shrine was recorded so as to map the geographical distribution of Waghoba shrines in the study area. All data points were added to a map using QGIS (see Figure 2). To create a visual repository of the deity and understand its physical characteristics, multiple photographs were taken at each shrine (check Supplementary Material). It was ensured that the photographs documented all the relevant details of each deity, and when applicable, its surrounding structure and any other deities in proximity. The process of documentation was also utilized as an opportunity for the primary researcher to become acquainted with people in the study area, establish a social network, and identify potential participants for the semi-structured interviews that were conducted subsequently.

A total of 34 semi-structured interviews were conducted with individuals within the study area during the span of fieldwork. A set of questions were prepared prior to the interview (see Supplementary Material for the interview guide), however the researchers exercised opportunistic discretion while asking questions in order to be flexible and sensitive to the flow of the conversation and each participant's particularities. The questions were designed to gain knowledge about and gather narratives on the role of Waghoba in the lives of the Warli, the history of Waghoba worship, associated festivals, rituals and traditions and the ties between Waghoba and human-leopard interactions. Multiple origin stories, narratives and beliefs associated with Waghoba and encounters with big cats were also recorded during the interviews. A purposive snowball sampling method was used to identify individuals in the landscape who had narratives and knowledge to share about Waghoba, a sampling method often used to document cultural phenomena (Bernard, 2017).

During fieldwork, there were typically four researchers who were part of the team. RN and OP conducted the interviews in the presence of two local field assistants, further referred to collectively as “field researchers.” The interviews were conducted in either Marathi or the Warli language. All the four field researchers speak Marathi, the state language of Maharashtra, which is linguistically similar to the Warli language, allowing the field researchers to converse with all the participants without much difficulty. The documentation of Waghoba shrines involved extensive travel across the entire landscape. Therefore, the researchers could not spend substantial time in each place to build their social connections. In this case, the field assistants played multiple roles; a bridge between the researchers and participants, a guide to the landscape, and a translator when the researchers encountered unfamiliar variants or tonal differences in language.

Participants of the study included Warli men who were farmers, school teachers, shamans (medicine men, conductor of rituals), sarpanch (village heads), and artists. All of these participants were men. The only exception to this was an expert interview conducted with a woman scholar who did not identify herself as Warli, but lived as part of a Warli community and had many insights into Warli culture. A majority of the participants were middle-aged and elderly men within the community. Even though we also aimed to interview Warli women, many factors restricted this. Firstly, our team of field researchers was male-dominated, with only one woman and three men, perhaps making it intimidating for women to participate. Secondly, the Warli community is patrilineal (Save, 1945), making it difficult to approach women directly. Furthermore, we did not spend enough time in each new site for women to grow comfortable enough to participate in interviews. We suppose that due to these reasons, women were hesitant to engage with us and often redirected the conversation to men within the household or village. The interviews were recorded using a handheld audio recorder after gaining informed, oral consent. To safeguard the anonymity of the participants, it was ensured that names and other identifiers were omitted from the interviews. The duration of interviews varied between 10 and 55 min. The audio recordings were translated into English and transcribed by multiple people, then checked by RN for accuracy. The interview quotes that appear in the text have been paraphrased to make them coherent after direct translation.

Participant observation is a central method used in ethnographic fieldwork wherein data is produced through direct observations, group discussions, and off-the-record conversations (Bernard, 2017). This allows for a flexible approach to fieldwork and produces valuable data that may be difficult to procure through other methods (Bernard, 2017, p.342; Vasan, 2018).

When enquiring about Waghoba shrines in our field site, participants shared details about an annual festival called “Waghbaras” observed for Waghoba. During this time, a pooja or ritual ceremony is conducted, and people make offerings to Waghoba. This was an ideal setting to understand this institution and observe rituals performed for the deity. We opportunistically attended three such ceremonies at different shrines, all of which will be unspecified to protect participants' and attendees' identities. RN was the primary observer at all three ceremonies, whereas OP and NS accompanied her at different ceremonies. We took photographic and video recordings of these ceremonies after obtaining consent from multiple attendees. It is not viable to take consent from each and every attendee as people kept flowing in and out of the venue. However, when video shooting any person in particular, consent was obtained from them personally. RN took notes of direct observations of the sequence of events that unfolded through the ceremony. One ceremony was observed during the night, another one was observed through the entire night and the next morning, while the third one was observed only during the morning after its commencement.

The exploratory nature of this study bears its own limitations. The fieldwork for our study was conducted over a short period of time and across a large geographic area. This meant that we could not spend as much time as we would have liked in each Warli settlement to gain the kind of depth and nuance that we strive for. Furthermore, the short-term nature of our study did not allow us to engage with the local community in a way that would have allowed us to collaborate and co-produce this paper with them. We recognize that this as a significant shortcoming and strive to be more collaborative in our future research (Smith, 1999; Sultana, 2007; Koster et al., 2012; Dutta, 2018). Another consequence of doing an exploratory study was that we had to be open to more opportunistic methods rather than doing systematic sampling. Even though we attempted to ensure as much representation as possible across age, class and socioeconomic status, stratified systematic sampling would have ensured more representational participant group. Our aim for representation was further compounded by the reality on ground wherein some, especially marginalized parts of society, were not accessible to us as researchers. This was particularly the case with gender representation as most of the Warli women that we approached hesitated to engage with us and often redirected the conversation to men.

The GPS locations of all the shrines were mapped using the software QGIS to show their spatial spread. Textual data, consisting of interview transcripts from semi-structured interviews and field notes from participant observations, were analyzed inductively. For this, a grounded theory method was used through which one can identify emergent themes and patterns within the data based on a grounded understanding of the social context gained through knowledge and ethnographic experience, rather than through a predetermined hypothesis. This process involves coding the data followed by developing, checking, and integrating theory and then writing analytic narratives (Charmaz and Belgrave, 2015; Tie et al., 2019).

NVivo software (version NVivo12 Pro) was used to code the data manually. As various themes and narratives emerged from the data, nodes and sub-nodes within NVivo were created. Extracts from each interview that proved explicitly relevant to each node were accumulated from all the transcripts. Relationships between different nodes created on Nvivo were identified and grouped to explore the central themes and narratives that emerged. Parallel to this, origin stories, narratives, and beliefs associated with Waghoba and accounts of encounters with big cats were also accumulated into separate nodes. Notes from participant observations were analyzed manually.

The prominent themes that emerged in this process included the history of Waghoba worship, rituals, and traditions, people's perception of the big cat (through stories and interactions), negotiation of shared spaces, and social dimensions of the worship. Themes and stories that illuminated the origin of Waghoba were then stitched together manually.

Through extensive mapping we documented 150 Waghoba shrines within the study site (Figure 2). A majority of these shrines were found in multi-use landscapes and a few in protected areas (PAs) like the Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Tungareshwar Wildlife Sanctuary which were being frequented by nearby residents. Prior studies on Waghoba (Athreya et al., 2018) have documented the presence of a few shrines in parts of our study site. Further, studies by Ghosal (2013) and Pimpale (2015) have documented the presence of Waghoba shrines in other parts of Maharashtra and Goa, India. We found clusters in various parts of our study site, particularly in the Palghar district where numerous Warli communities live. We noted that all the villages that housed people from the Warli community had at least one Waghoba shrine in their vicinity, if not more. Some of the villagers explained that many villages may have two shrines: one in the village and one on a local hilltop. Though we were able to locate and document almost all the Waghoba shrines that were within the premises of the villages that we traveled to, the same was not always possible of the hilltop shrines. Due to this reason, we cannot claim that we have exhaustively documented all the Waghoba shrines in the study area.

Among the multiple communities that worship the big cat deity, Waghoba is known by multiple names such as Waghdev, Waghya, Waghjai, Bagheshwar, Waghjaimata (female form), with Waghoba being the most commonly used name in our study site (Gadgil and Malhotra, 1979; Newman, 2012; Ghosal and Kjosavik, 2015; Athreya et al., 2018). Waghoba is derived from the Marathi words “wagh” which means big cats and “ba,” a term assigned to an elderly or paternal figure in the community. The interviews revealed that the people in this landscape perceived leopards and tigers to be alike and considered them both to be a form of Waghoba. The word wagh is similar to the Hindi word bagh, which is used to refer to both the tiger and the leopard in other parts of India (Mathur, 2016); which indicates that people in this landscape have their own taxonomic categorization of these species which may not be concordant within the specifics of modern scientific taxonomy (Shull, 1968; Landy, 2017).

The iconography of Waghoba that we came across was of a feline under the sun and moon, carved on either stone or wood (specifically teakwood) slabs covered with a bright vermillion paste. Some participants explained that the sun and moon symbolized energy. Many villages had Waghoba shrines built at the entrance to the village indicating that Waghoba might be considered as a gatekeeper, protecting the entire village. Shrines that we came across ranged from small, modest monuments to big, elaborate ones that were seen particularly in semi-urban parts of the study site (Figure 3).

Participants could not account for the age of the shrines in their respective villages but stated that they were at least a few 100 years old. Wooden idols that decayed were replaced in the same place every 15–20 years. It may be relevant to note that not all shrines consisted only of the Waghoba idols, idols of other deities such as the Gaondevi (village goddess), Zoting (spirit of a man) or Veer (soldiers) could often be seen established within the same shrine premises. This suggests that Waghoba exists within an interconnected network of deities worshiped by the community. However, in many Warli villages, Waghoba was worshiped as the chief village deity or gaondev.

Waghoba is worshiped above all for protection from big cats, disease and calamities. Participants spoke of the wagh as the junglacha raja (king of the jungle). One participant also called Waghoba the “main boss.” Furthermore, many of them also stated that the wagh is to the forest what the sarpanch/patil (village head) is to the village, extending both the deity and the animal a sense of authority (Descola, 2013). They stated that when people roam in the forests, they put their trust in Waghoba because he is their protector.

“The wagh is known and accepted as the king of the jungle. We pray to him so that he protects us and does not do us any harm.”

The Warlis are known to commence important life and social events such as weddings, naming a child and building new homes only after receiving blessings from Waghoba. One participant said, “Since Waghoba is a gaondev or village god, when there is a wedding, the invitation is first brought to Waghoba before being distributed.”

The institution of Waghoba has persisted over centuries through oral tradition and ritual practice. While there is no single origin story of this deity, we came across multiple parallel narratives that describe myths or instances that gave birth to the deity. While some participants, especially shamans, shared elaborate origin stories, most of the other participants narrated fragments of these stories, containing similar underlying beliefs. Stitching together fragments of stories from different interviews, we learnt of the origin stories that narrate how the deity came into being.

These narratives illustrate a woman, typically a princess or chief's daughter, who gives birth to a baby out of wedlock. When his mother is out doing chores, the baby shape-shifts into a tiger and hunts the villager's livestock. Troubled and scared by the tiger, the villagers decide to kill the tiger. To save her child, the mother mediates between the angry villagers and her baby. In the negotiation that follows, she asks her child to go away into the forest and in exchange, the people would install shrines for the wagh, and once a year give an offering of the animals he likes (such as chickens and goats) to make peace. That is the story of how the wagh then took sanctuary in the forest and Waghoba shrines came to be established across all villages.

Some parallel narratives of peoples lived experiences were also shared to illuminate the birth of local shrines in villages. The local shrine located at Kartod Village was cited by many participants as the foremost Waghoba shrine in the landscape and was among the few shrines that we came across which had been made into a big temple.

Years ago, a wagh was terrorizing our ancestral village called Kartod. The wagh kept entering people's houses, which at the time were made of thick leaves. Eventually everyone abandoned this village and moved into other settlements. Then one night, in the new settlement, a crying baby attracted the wagh again. However, the baby's mother beat the creeping wagh with a stick, which ended up killing it. After hearing about this, all the scared villagers appealed to the shamans to do something about so as to evade misfortunes. The shamans suggested worshiping the troublemaking wagh after which shrines were made in every village to pacify the wagh. They were the ones who began offering animal sacrifice and observing the Waghbaras festival which is now practiced in all shrines.

The festival of Waghbaras which literally translates to wagh-festival is observed annually to appease Waghoba. It is popularly celebrated on the auspicious day of Vasu Baras which is the first day of the Hindu festival of Diwali based on the lunar calendar. The festival entails celebrations, rituals and traditions to appease Waghoba at the local shrine.

We observed three of these ritual ceremonies at shrines located in both rural and semi-urban parts of our study site. These ceremonies typically last for two days and the intervening night, with traditional music and dancing throughout the night. Relatives and friends of participants from neighboring villages also attend the ceremony. Members of the community, even those that have moved away to other parts of the world return at this time to participate in the annual worship rituals for Waghoba. While one of the observed ceremonies took place in a rural hamlet, the other two took place in semi-urban areas. The shaman led the ceremony and performed all the rituals with the remaining participants following his directive. People offered a variety of things as per their ability, from flowers, coconuts, and incense to toddy (fermented palm drink), chickens and, goats. The idols are also smeared with vermillion paste, which is considered auspicious. Orally passed down chants and songs dedicated to Waghoba were presented throughout the festival days and nights. However, the main feature of the ceremony, was the sacrifice of the chickens and goats. The head of the sacrificed animal was kept at the shrine and the rest of the meat was distributed among people.

During worship rituals, the shaman is believed to take the form of a wagh by entering into a state of trance. Participants recall instances of the shaman climbing trees, roaming the vicinity on all fours and also having tremendous physical strength at such times. Shamans are also sometimes believed to be capable of retrieving medicinal plants from the mountains in this state. This happens several times through the night and day when attempting to evoke the spirit of Waghoba. It is also believed that he has a strong intuition or may prophesize, which should be heeded.

“Some bhagats would take the form of a wagh, as in the spirit of the wagh would come in them. They would behave like a wagh would; go on all fours. If there is a region with thorns etc., he will pass through that as well. And after that, until the spirit of the wagh is in him, the thorns won't hurt him.”–Interview participant

We also observed apparent gendered dimensions associated with the worship of Waghoba that could influence the way men and women perceive leopards differently. Within the Warli community, the role of a shaman is always played by a man. One person stated “The bhagat leads the rituals and everyone else follows. This knowledge, of how to conduct rituals, has been learned from elders.” Historically only men participated in the worship ritual and ceremonies, whereas women were traditionally not permitted to attend the ceremonies. However, in recent times, women are being included and “allowed” to attend the rituals. We observed this particularly during the Waghbaras ceremony in semi-urban areas.

Participant observation during the fieldwork and data collected from key informants revealed a prevailing belief among locals that certain women within the community were well-versed with dark magic. Furthermore, during fieldwork the field researchers experienced instances where they were advised to leave the premise of a shrine or not enter one when particular women (whom locals believed to be witches/holders of such powers) were around. Literature on the Warli people is also indicative of such beliefs. Warli men who are shamans are known to mediate the relationship between people and deities by performing the right rituals which may be considered “good” whereas women are known to practice forms of “evil” magic (Dandekar, 2005). There are also beliefs among the Warlis that witchcraft and its tendencies are innate to women (Save, 1945).

Considering that it was traditionally men who participated in ritual and ceremonial worship of Waghoba, there exists a history of disparity in the ritualistic interaction with the deity among men and women. This denotes that there are gendered dimensions to the worship of Waghoba as well as people's relationship with the wagh. If women have historically been alienated from the direct worship and opportunity to negotiate with Waghoba, it could be having implications on women's perception toward leopards being different from those of men. As we were unable to engage with many women in our study, we were unable to explore the specific nature of the gender related similarities or differences. However, our data indicates that there is great scope for future studies to investigate the gendered dimensions of Waghoba worship.

The Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Tungareshwar Wildlife Sanctuary are known to have documented populations of leopards (Surve and Ahmed, 2017). In other parts of our study sites in multi-use landscapes, we noted through anecdotes that leopards were seen and rescued frequently by the local Forest Department and wildlife rescue NGO. This, along with narratives from interview participants indicates that the leopard is not a distant, but an active part of the landscape. The lines appear blurred between the wagh and Waghoba among the people we interviewed. A participant explained through the analogy: just as our gods have human form, tigers and leopards are forms of the deity Waghoba. Within this belief system, not only are living beings such as leopards worshiped but also “inanimate” beings such as stars, thunder and rain. One participant explained how people pray to the relevant gods for their livestock's protection from factors such as rain, disease, etc. Likewise, they pray to Waghoba so that the large cats do nott eat their livestock. This underpins the Warli worldview which sees waghs as stitched with Warli cultural identity, rather than as just a biological being.

Nearly all participants considered the animal to be a god. However, if not propitiated or appeased appropriately, the god can harm them or their livestock, through the animal. Similarities have been noted, not just in cases of other human-feline relations, but also among human-snake relations in South India by Landry Yuan et al. (2020). They suggest that the snake (animal) and snake-deity are “inexorably connected in the sense that any affliction posed toward snakes, wither intentional or accidental, is believed to bring forth the wrath of the Nagas (serpent-gods) in various forms…” (Landry Yuan et al., 2020). Although there is an element of fear associated with the big cat, there is also trust in the wagh as a protector of the people. An example of this can be seen in the story of a little boy who was once looked after by a leopard. The little boy fell asleep at a Waghoba shrine during a ritual and was forgotten there. When his family went back to fetch him they found a wagh sitting guard over the sleeping child. Once villagers approached the shrine, the wagh went away, having done no harm. It is believed that the wagh kept watch over the boy, because it knew that the people worship him. One participant shared a story demonstrating the faith his father had in Waghoba. Such narratives, both of the past and present reinforce the belief among people that their faith in Waghoba is what keeps them safe.

“Let me tell you an incident of 30–35 years ago. My father was going to my mother's village before they got married, by the road on foot. He saw a wagh right in front of him. Now what do you do in these situations? The person cannot attack it right…so my father said “if you are going to eat me then go ahead. You are our god.” Then he closed his eyes. The wagh just walked away. Didn't do anything.”

Another narrative of protection associated with leopards is that when people are walking in the forest or in the dark, leopards walk with people, escorting them back to their homes. Many of the people we interviewed also explained that Waghoba protects not only individual people but also guards the village as a whole.

The prevalence of Waghoba across the landscape was extensive. Almost every Warli village in our study area that we came across had a Waghoba shrine where people would regularly conduct ritual ceremonies. With the occurrence of over 150 shrines (and likely many more), we can therefore say that Waghoba is not just a relic whose traces are found in a single place, but an actively worshiped deity who is considered an integral part of the social institutions in this landscape. The full extent of Waghoba's geographical reach is yet to be documented and holds potential to underscore the deity's relevance in the larger landscape and daily lives of residents. The origin myth for Waghoba contains elements of what is termed “human-wildlife conflict” or “livestock depredation by big cats” in the conservation science literature. The origin myth narrates how the wagh is asked to leave the village for causing mayhem by eating livestock. This shows how, not just the wagh, but also livestock depredation as being morally and materially accepted, having found cultural representation. The dominant conservation discourse contains a narrative wherein predators happen to transition over time from eating “natural” or “wild” prey to eating livestock out of necessity as if livestock depredation is a new phenomenon that we have just had to start making sense of, coping with, mitigating, and addressing. This dilutes the fact that these interactions have been an everyday reality for communities over centuries. The Warli belief system pre-dates the onset of the human-wildlife conflict discourse by at least a few 100 years. The origin story illustrates how; to deal with the losses caused by the wagh eating their livestock, the people initiated a negotiation with Waghoba; and by extension the wagh.

There have been many studies that explore the relevance of existing belief systems and narratives to conservation, specifically human-wildlife co-existence (Hill, 2011; Kolipaka et al., 2015; Aiyadurai, 2016; McKay et al., 2018; Parathian et al., 2018; Nijhawan and Mihu, 2020). For example Li et al. (2014) discuss how Tibetan Buddhism contributes toward the sharing of space between shepherds and snow leopards. However, Warli narratives are particularly unique because they not only instill an ethic of not killing big cats, they also provide ways in which to comprehend and process the loss and complexities that arise consequent to incidents of human-wildlife conflict (such as livestock depredation).

In many variants of the origin story, Waghoba, is depicted as someone who was born human. They narrate how, as he grew up, he strayed away from his human origin and succumbed to his disposition of being a wagh. The origin stories narrate instances where Waghoba, out of his inevitable disposition, kills livestock and the ways in which a negotiated deal is struck between the people and Waghoba to maintain co-existence. Further, it is Waghoba's mother, rather than an authority such as the king or chief, that initiates the negotiation between the people and Waghoba; making this act entwined in kinship. This allows for people to see him as not just a menacing man-eater but also as someone who is on the one hand bound by his nature of being a wagh, while on the other hand bound by a promise he has made with his human kin. The belief in the possibility of negotiating space with the wagh perhaps stems from feelings of relatedness and kinship owing to his human origin and familial ties in the origin story (Jalais, 2014). It also allows for this institution to perpetuate shared space for wildlife to flourish in multi-use landscapes.

The festival of Waghbaras acts as a manifestation of this bargain through offering animal sacrifice of livestock to Waghoba in exchange of his benevolence and protection from danger and harm, especially of kinds caused by big cats. Communal gathering, music and dancing, and feasting are all as important as the ritualistic aspects of Waghoba worship, as they strengthen communal bonds and reinforce a sense of Warli identity within all the participating members of the community (Bird-David, 1999). Furthermore, the kinship ties in the origin myth perhaps strengthen people's belief that Waghoba will hold up his end of the deal, protecting them from big cats. For example, a majority of participants in our study cited reasons such as having conducted the required rituals inaccurately or intermittently rather than annually to justify the adversities associated with big cats. This may also be perceived as a mutual dependence of Waghoba on the people (for propitiation) and of the people on Waghoba (for protection), paving way for a relatedness and reciprocal relationship. Several scholars note that societies with such human-animal dynamics are built on values of mutual respect and reciprocity (Hill, 2011; Ghosal, 2013; McIntosh and Maly, 2014; Artelle et al., 2018). Hill (2011) puts forward that in such systems, humans and animals enter into obligations and failure to honor these can pose threats and complications. These values, combined with the periodic festival, which reinforces the belief in negotiations and materializes it though sacrificial offerings are perhaps what contributes to sustaining Warli relationships with waghs. This also relates to the body of literature describing narratives of retribution for disrespectful acts present in various indigenous cosmologies (Atleo, 2011; Turner, 2014; Artelle et al., 2018; McKay et al., 2018).

When there is an occasional incident of livestock depredation, more often than not, people in this landscape attribute it to their own oversight rather than blaming the predator. It is understood as a consequence of the people not having met their end of the bargain i.e., conducting the required rituals and making offerings. McKay et al. (2018) draw parallels from Sumatra where people perceived tiger-related deaths as retribution for when moral codes (such as unfairly dividing an inheritance or committing adultery) were broken by family members, rather than blaming the tiger alone. Rather than only holding the animal accountable, the process of perceiving negative encounters in this manner, allows for the blame to be shared between the people, leopard and Waghoba. Institutions such as the Forest Department and conservation organizations predominantly understand human-wildlife conflict as rooted in material and socio-economic losses and therefore, respond through techno-managerial measures (such as mitigation and compensation). The institution of Waghoba illustrates how residents could be processing incidents of conflict in a notably different manner to the other stakeholders or institutions in the landscape. This elucidates the need for more recognition of and sensitivity toward local belief systems especially in the context of incidents of human-wildlife conflict, which currently have little to no place in the mitigation-compensation metric.

This is relevant for present day wildlife conservation because such traditional institutions are likely to act as acceptance building mechanisms embedded within local cosmology. Studies have shown that people are more likely to base their perceptions toward wildlife on social factors rather than objective assessments of the threats posed by wildlife (Dickman, 2010; Redpath et al., 2013). While efficiency in addressing real economic losses is an important factor in conflict mitigation, perceived efficiency and perceived risk are also important aspects defining human-wildlife relationships. Addressing human-wildlife conflict has to therefore also stem from understanding the perceptions and belief systems of the range of stakeholders in any landscape (Miller et al., 2017).

While there are cultural narratives that have a discourse surrounding human-wildlife conflicts embedded within them, there are also social structures, politics and relations of power that govern and aid the persistence of these social institutions. The ethnographic fieldwork shed light on some of the many influences that shape the institution of Waghoba. While we cannot claim any insight about the factors that have historically been a part of shaping this institution, we can illuminate a few factors that shape the institution of Waghoba in the present.

When animals are perceived as persons or spiritual entities, rituals can play an important role in materializing their relationship with people. The shaman holds a key place in many animistic cultures as the mediator between humans and other beings (Hill, 2011). Similarly, the bhagat, the local equivalent of a shaman, holds significance when it comes to the worship of Waghoba. While the specific nature of shamanism varies across societies, it typically shares three main elements including (a) belief in the existence of a spirit world, (b) a capacity of the shaman's spirit to enter into the supernatural world, (c) the shaman's ability to treat ailments and help people overcome various difficulties and problems in the real world (Stutley, 2003).

The shamans powers described by our participants parallels with a plethora of narratives concerning therianthropy i.e., human-animal-superhuman transformations (particularly tigers, leopards and jaguars in this context), which have been documented across cultures in Africa (Quammen, 2004), South America (Kohn, 2007), South and South-East Asia (Boomgaard, 2001; Oppitz et al., 2008; Brighenti, 2011; Newman, 2012; McKay et al., 2018).

Paying attention to shamans and such rituals may perhaps be of interest to conservation practitioners or policy-makers due to their strong role in influencing views and beliefs about big cats. As a mediator between the people and Waghoba, the shaman has a powerful, pre-eminent social position. Typically, the Forest Department or other such formal institutions are expected to mediate, especially estranged relationships between people and big cats. Here, we are presented with situations where it could equally be the shaman negotiating between people and big cats, displaying a complimentary role of both formal and informal institutions. So far, very few conservation actions by government authorities or NGOs have acknowledged the influential role of such informal, traditional institutions, let alone inculcated them into the conservation ethos.

Furthermore, the Waghbaras ceremony typically runs through contributions from each household in the village or sometimes just participating members. The animals to be sacrificed, fee for the shaman and other expenses are all covered through these contributions. Hence, the scale of these ceremonies also differs based on how much people from different communities are able to offer each year. In both shrines located in semi-urban and protected area settlements, we observed support from local political parties, city-dwelling allies of the local Warli participants, and other people who can be considered influential, particularly monetarily. Consequently, the ceremonies in semi-urban settlements were grander than the comparatively modest ones observed at the rural settlements. The institution of Waghoba is thus shaped over time and is susceptible to the influence of local politics. Such adaptations also present facets of how non-Warlis interact with this institution and influence its sustenance.

Historically, colonial administrators and ethnographers writing about various communities, particularly marginalized indigenous communities in India, conceptualized them to be in contrast to what they saw as the general and universal features of Indian society, by extension the dominant Hindu society. Consequently, indigenous communities are structurally conceptualized as existing at the fringes of the larger Indian society (Xaxa, 2005). The cultural transitions that these communities are experiencing are therefore understood as a process of acculturation arising from their interaction with, and integration into, the larger, dominant society. One of the many ways in which this integration occurs is through religious conversion. Bose (1941) describes this acculturation of indigenous groups into the wider Indian society, by extension the Hindu society, as invariably providing marginalized societies protection and security. Srinivas (1977) also discusses Sanskritisation, the process through which lower castes in the hierarchy emulate the lifestyle and practices of higher castes (Xaxa, 2005). While the former belief perpetuates the idea that culture is static and unitary, these systems are far more dynamic and fluid. It perceives them as unidimensional rather than a process through which communities interact with the world and incorporate and transform elements over time (Rapport and Overing, 2000).

The Indian Constitution recognizes Indigenous Peoples and notifies them as “Scheduled Tribes.” Our field site, the Dahanu sub-district of Maharashtra is listed as a “Full Schedule Area” indicating that a majority of its resident population are Indigenous. Participant observation revealed a melting pot of religious practices and beliefs in the region pertaining to Christianity and Hinduism in these regions. Additionally, literature on the history of these regions indicated that Christian missionaries have been active in the region for several decades (Save, 1945). The presence of multiple shrines and temples of Hindu deities were also noted in these regions. While some Warli participants in the study claimed that Indigenous people like themselves do not participate in idol worship like Hindus do, some others affirmed that they also worship deities from the Hindu pantheon. Moreover, idols and pictures of Hindu deities were observed at some participant's residences, where interviews were often conducted. We also came across narratives of Waghoba entangled in narratives of Hindu deities. For example, some participants declared that Waghoba was a form of the Hindu deity Hanuman as they are both unmarried. Some said Waghoba is a form of the Devi's (goddess) vehicle which is a tiger. It appears as though worship for the Warlis has amalgamated Waghoba and deities from the Hindu pantheon. This indicates more plurality in religiosity among the Warli than we had presumed.

Despite the prevalence and layering of other religious beliefs among Waghoba worshippers, the commitment to continue performing traditional rituals in order to continue their relationship with the deity appear to remain strong. West (2005) notes that one of the main changes that is associated with religious conversion include changes in the structure of the workweek and beginnings of a loss of knowledge about mythology. However, even in instances where conversion takes place across entire landscapes, it may still be common to see people retain some of their erstwhile beliefs and practices (West, 2005; Oppitz et al., 2008; Shaffer et al., 2018).

Participant observations revealed that members of the community who have converted or expanded their religious beliefs continue to worship Waghoba as one of their chief deities and take part in the Waghbaras festival. This indicates that Waghoba is not just a deity who is worshiped within the confines of one belief system but is an integral part of the cultural fabric, entwined with the traditions and social life of this landscape. This has also been observed by Ghosal and Kjosavik (2015) who studied this institution among the Thakkars and Mahadeo Kolis in Akole, Maharashtra.

Similarly in the Sundarbans, Bonbibi is worshiped as the woman of the forest who was sent by Allah to save people from tigers. Bonbibi's worshippers think of her as a “forest superpower” rather than in terms of “Muslim” or “Hindu,” who extends her protection to all her worshippers regardless of the community identities. Bonbibi, who serves a particular role as the woman of the forest and is worshiped for that in particular, cannot be replaced by other deities worshiped in the landscape like Krishna or Kali (Jalais, 2014). In this manner, even though the Warlis now also worship other deities, the worship of Waghoba continues, owing to specific role he has of protecting people from big cats, rendering the deity irreplaceable in the landscape. We suggest that such relationships enable the communities who have such relations with wildlife to be more accepting of the presence of big cats in their landscapes. Furthermore, we propose that the presence of such relationships in a landscape makes it easier for large carnivores such as leopards and tigers to reclaim the areas they used to once live in. This is because there is already a pre-existing and very powerful relationship the people of that landscape have with these animals through the icons in their culture.

When addressing conservation concerns in areas where local communities share intimate, multi-layered relationships with wildlife, the discourses and practices of people sharing the landscape are often diminished to give way for the narratives attached to the species of concern. When conservationists focus on only the ecological aspects of conservation without engaging with its social dimensions, it leaves local communities (who face direct impacts) feeling neglected and often pitted against the species being conserved at the interest of powerful governments, scientists, urban elites etc. This can perhaps result in uncooperative responses from the community when approached for conservation initiatives (Jalais, 2008; Dickman, 2010; Mishra et al., 2017). Acknowledging these beliefs and integrating them into bureaucratic practices lends these communities the respect and justice they deserve, especially owing to the lack of representation in decision making on their own land. An understanding of this can help dominant stakeholders outside the Warli community (such as the Forest Department, conservation biologists, and non-Warli residents who interact with leopards) develop the required insight and sensitivity to work in such landscapes as it is not just the biological animal that the Warli are predominantly living with.

Further, Waghoba exists not only in remote, rural landscapes, but also in cities such as Mumbai fostering the capacity to capture the imagination of a larger urban population. Such belief systems have largely been external to urban policy and planning in India. Narayanan and Bindumadhav (2019) propose species-inclusive cities which imagine and build new kinds of urban ecosystems that allow for reconciliation between human development and biodiversity (in this case, along with people's varied relations with biodiversity as well). In such systems, species are also considered as social actors. Such ways of thinking already exist within the Warlis, who live in the heart of Mumbai.

When it comes to conservation ethics and pro-conservation behavior, group dynamics and positionality plays a huge role in defining individual behavior (Hare et al., 2018). Bhatia et al. (2021) argue that identifying areas of societal or individual motivations which are either complimentary or contrasting to biodiversity conservation, particularly through examining folklore can provide knowledge to design culturally meaningful strategies which facilitate human-wildlife coexistence. Further, conserving and integrating diverse sets of knowledge, both biophysical and sociocultural, can give greater adaptive capacity to such strategies allowing them to sustain through societal and environmental changes (Berkes et al., 2000; Gavin et al., 2015). Waghoba is exemplary in underlining how as systems, values and people's surroundings evolve, institutions adapt to these changes in order to persist (Berkes and Turner, 2006; Artelle et al., 2018).

In many landscapes, people have an antagonistic relationship with predators and returning species are not accepted (Boomgaard, 2004; König et al., 2020). Acceptance of large predators in human dominated landscapes is then viewed as an aberration despite many societies having a history of shared spaces with them. In this way, myths and narratives that build on local institutions, such as that of Waghoba, carry relationships forward even though the animals themselves have gone. Through this paper, we would like to propose that these relationships could be crucial for enabling the return of carnivores, such as large cats, in areas where they have been extirpated; because the relationships that people have with them still exist in the landscape.

Through our study we have explored some of the myriad ways in which the Warli and big cats have interacted though history, ranging from various degrees of conflicts to forms of coexistence, that shape their present day relations. The institution of Waghoba reveals that there is a long history of engaging with issues surrounding human-wildlife interactions and trying to comprehend the consequences associated with sharing space with potentially dangerous or conflictual predators. The festival of Waghbaras exemplifies the presence of systems arisen from such continued engagements. As negative interactions (such as livestock depredation) may still occasionally occur in the landscape, they are likely to be more accepted under the institution of Waghoba, notwithstanding the spiritual complexities and economic losses people face. We believe these complex and nuanced relations have a role in aiding shared spaces.

Our aim was to document shrines and narratives, explore the prevalence of this institution and describe its relevance for conservation. What this groundwork has brought to light is the potential for a detailed enquiry into the nuances of the institution of Waghoba. This can widen the scope to present insight on the different meanings of Waghoba worship and how this institution impacts how humans and big cats share space and resources.

An underlying aim of our study is to contribute toward diversifying the ways in which we understand and approach human-wildlife interactions. It does so by shedding light on how local institutions that contribute to co-existence are not devoid of conflict, but have a role in negotiating the conflicts that arise. Locally produced systems that address issues surrounding human-wildlife interactions may exist in several other cultures and landscapes. While conservation interventions have shown a movement toward the inclusion and participation of local communities, there is still a lack of recognizing that landscapes have a history before our own point of entry into them, which is valuable to consider. Conservationists are often looking for scalable interventions across landscapes. This paper however, forces us to reconsider the precedence of scalability by illustrating the role of localized specificities and histories of landscapes which would necessitate its own intervention model, if intervention is needed at all. It is worth reflecting on how fleeting our conservation interventions can be in comparison with something as resilient as the institution of Waghoba.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human Study Ethics Committee, Wildlife Conservation Society-India. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

VA, RN, and Dhee conceived and designed the study. AA provided funding for the study. RN and OP collected the data. RN and Dhee analyzed the data and led the writing of the manuscript. NS helped in coordination of fieldwork and supported data collection. VA and JL provided guidance, critical reviews, and editing. All authors have contributed significantly to the drafts of the manuscript and have given their approval for publication.

This work was supported by Wildlife Conservation Trust, and Research Council of Norway (grant 251112) for JL.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank Dr. Sahil Nijhawan for reading the manuscript and providing his valuable inputs. We would like to thank our field assistants Sandesh Mahale, Parag Raorane, Krunal Parekh, and Raymond D'Souza for their help and enthusiasm throughout fieldwork. We would also like to thank our multiple hosts in Jawhar, Dahanu, and Mumbai for their time and hospitality. We thank the staff at WCS-India for their support. Most importantly, we are grateful to numerous Warli people who graciously welcomed us to their homes and shared their knowledge and narratives with us.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2021.683356/full#supplementary-material

Århem, K. (2016). “Southeast Asian animism: a dialogue with amerindian perspective, “ in Animism in Southeast Asia, eds K. Århem and G. Sprenger (New York, NY: Routledge), 279–301.

Abercrombie, N., Hill, S., and Turner, B. S. (1994). The Penguin Dictionary of Sociology. London: Penguin Books.

Aisher, A., and Damodaran, V. (2016). Introduction: human–nature interactions through a multispecies lens. Conserv. Soc. 14, 293–304. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.197612

Aiyadurai, A. (2016). “Tigers are our brothers”: understanding human-nature relations in the Mishmi Hills, Northeast India. Conserv. Soc. 14:305. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.197614

Andheria, A. P., Karanth, K. U., and Kumar, N. S. (2007). Diet and prey profiles of three sympatric large carnivores in Bandipur Tiger Reserve, India. J. Zoo. 273, 169–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00310.x

Artelle, K. A., Stephenson, J., Bragg, C., Housty, J. A., Housty, W. G., Kawharu, M., et al. (2018). Values-led Management: the guidance of place-based values in environmental relationships of the Past, Present, and Future. Ecol. Soc. 23:35. doi: 10.5751/ES-10357-230335

Athreya, A., Pimpale, S., Borkar, A. S., Surve, N., Chakravarty, S., Ghosalkar, M., et al. (2018). Monsters or gods? narratives of large cat worship in Western India. Cat New 67, 23–26.

Athreya, V., Odden, M., Linnell, J. D. C., Krishnaswamy, J., and Karanth, K. U. (2016). A cat among the dogs: leopard panthera pardus diet in a human-dominated landscape in Western Maharashtra, India. Oryx 50, 156–162. doi: 10.1017/S0030605314000106

Athreya, V., Odden, M., Linnell, J. D. C., Krishnaswamy, J., and Karanth, U. (2013). Big cats in our backyards. Persistence of large carnivores in a human dominated landscape in India. PLoS ONE 8:e57872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057872

Atleo, E. R. (2011). Principles of Tsawalk. An Indigenous Approach to Global Crisis. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Berkes, F., Colding, J., and Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 10, 1251–1262. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2000)0101251:ROTEKA2.0.CO;2

Berkes, F., and Turner, N. (2006). Knowledge, learning, and the evolution of conservation practice for social-ecological system resilience. Hum. Ecol. 34, 479–497. doi: 10.1007/s10745-006-9008-2

Bernard, H. R. (2017). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bhagat, S. (2010). “How Mumbai Lost Its Animal Instinct” in Times of India. Available online at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/how-mumbai-lost-its-animal-instinct/articleshow/5854425.cms (accessed January 2, 2021).

Bhatia, S., Redpath, S. M., Suryawanshi, K., and Mishra, C. (2019). Beyond conflict: exploring the spectrum of human–wildlife interactions and their underlying mechanisms. Oryx 54, 621–628. doi: 10.1017/S003060531800159X

Bhatia, S., Suryawanshi, K., Redpath, S. M., Namgail, S., and Mishra, C. (2021). Understanding people's relationship with wildlife in trans-himalayan folklore. Front. Environ. Sci. 9:595169. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.595169

Bird-David, N. (1999). Animism revisited: personhood, environment, and relational epistemology. Curr. Anthropol. 40, 67–91. doi: 10.1086/200061

Boomgaard, P. (2001). Frontiers of Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World 1600-1950. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Boomgaard, P. (2004). “Primitive tiger hunters in indonesia and malaysia, 1800-1950,” in Wildlife in Asia: Cultural Perspectives, eds J. Knight (London: RoutledgeCurzon), 185–206.

Brighenti, F. (2011). Kradi mliva: the phenomenon of tiger-transformation in the traditional lore of the kondh tribals of orissa. Lokaratna 4, 11–25.

Carter, N. H., and Linnell, J. D. (2016). Co-adaptation is key to coexisting with large carnivores. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 575–578. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2016.05.006

Chapron, G., Kaczensky, P., Linnell, J. D. C., Manuela von, A., Huber, C., et al. (2014). Recovery of large carnivores in europe's modern human-dominated landscapes. Science 346, 1517–1519. doi: 10.1126/science.1257553

Charmaz, K., and Belgrave, L. L. (2015). “Grounded theory,” in The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, ed G. Ritzer (Oxford: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.), 1–5.

Crown, C., and Doubleday, K. (2017). “Man-eaters” in the media: representation of human-leopard interactions in india across local, national, and international media. Conserv. Soc. 15,304–312. doi: 10.4103/cs.cs_15_92

Dandekar, A. (2005). Mythos and Logos of the Warlis: A Tribal Worldview. Delhi: Concept Publishing Co.

Descola, P. (1992). “Societies of nature and the nature of society,” in Conceptualizing Society, ed A. Kuper (London: Routledge), 107–126.

Descola, P. (2013). Beyond Nature and Culture. Translated by Janet Llyod. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Descola, P., and Pálsson, G. (1996). Nature and Society: Anthropological Perspectives. London: Routledge.

Dhee, Athreya, V., Linnell, J. D. C., Shivakumar, S., and Dhiman, S. P. (2019). The leopard that learnt from the cat and other narratives of carnivore–human coexistence in Northern India. People Nat. 1, 376–386. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10039

Dickman, A. J. (2010). Complexities of conflict: the importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human-wildlife conflict. Anim. Conserv. 13, 458–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x

Doubleday, K. (2017). Nonlinear liminality: human-animal relations on preserving the world's most famous tigress. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/00167185 Geoforum 81, 32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.02.005

Dutta, R. (2018). Decolonizing both researcher and research and its effectiveness in indigenous research. Res. Ethics 12, 1–24. doi: 10.1177/1747016117733296

Edgaonkar, A., and Chellam, R. (2002). Food habit of the Leopard, Panthera pardus, in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Maharashtra, India. Mammalia 66, 353–360. doi: 10.1515/mamm.2002.66.3.353

Gadgil, M., and Malhotra, K. C. (1979). Role of deities in symbolizing conflicts of dispersing human groups. Ind. Anthropol. 9, 83–92.

Gadgil,. M., Berkes,. F., and Folke, C. (1993). Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio 22, 151–156.

Gavin, M. C., McCarter, J., Mead, A., Berkes, F., Stepp, J. R., Peterson, D., et al. (2015). Defining biocultural approaches to conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.12.005

Ghosal, S. (2013). Intimate beasts: exploring relationships between humans and large carnivores in Western India (Ph.D. thesis.). Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås, Norway.

Ghosal, S., Athreya, V. R., Linnell, J. D. C., and Vedeld, P. O. (2013). An ontological crisis? a review of large felid conservation in India. Biodivers. Conserv. 22, 2665–2681. doi: 10.1007/s10531-013-0549-6

Ghosal, S., and Kjosavik, D. J. (2015). Living with leopards: negotiating morality and modernity in Western India. Soc. Nat. Resour. 28, 1092–1107. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2015.1014597

Goldman, M. J., De Pinho, J. R., and Perry, J. (2010). Maintaining complex relations with large cats: maasai and lions in Kenya and Tanzania. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 15, 332–346. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2010.506671

Goldman, M. J., De Pinho, J. R., and Perry, J. (2013). Beyond ritual and economics: maasai lion hunting and conservation politics. Oryx 47, 490–500. doi: 10.1017/S0030605312000907

Hare, D., Blossey, B., and Reeve, H. K. (2018). Value of species and the evolution of conservation ethics. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5:181038. doi: 10.1098/rsos.181038

Hill, E. (2011). Animals as agents: hunting ritual and relational ontologies in Prehistoric Alaska and Chukotka. Camb. Archaeol. J. 21, 407–426. doi: 10.1017/S0959774311000448

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge.

Jalais, A. (2008). Unmasking the cosmopolitan tiger. Nat. Cult. 3, 25–40. doi: 10.3167/nc.2008.030103

Khumalo, K. E., and Yung, L. A. (2015). Women, human-wildlife conflict, and CBNRM: hidden impacts and vulnerabilities in Kwandu Conservancy, Namibia. Conserv. Soc. 13, 232–243. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.170395

Kohn, E. (2007). How dogs dream: amazonian natures and the politics of transspecies engagement. Am. Ethnol. 34, 3–24. doi: 10.1525/ae.2007.34.1.3

Kolipaka, S. S., Persoon, G. A., de Iongh, H. H., and Srivastava, D. P. (2015). The Influence of people's practices and beliefs on conservation: a case study on human-carnivore relationships from the multiple use buffer zone of the panna tiger reserve, India. J. Hum. Ecol. 52, 192–207. doi: 10.1080/09709274.2015.11906943

König, H. J., Kiffner, C., Kramer-Schadt, S., Fürst, C., Keuling, O., and Ford, A. T. (2020). Human-wildldife coexistence in a changing world. Conserv. Biol. 34, 786–794. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13513

Koster, R., Baccar, K., and Lemelin, R. H. (2012). Moving from research ON to research WITH and FOR indigenous communities: a critical reflection on community-based participatory research. https://www.researchgate.net/journal/Canadian-Geographer-Le-Geographe-canadien-1541-0064 Can. Geogr. 56, 195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00428.x

Kshettry, A., Vaidyanathan, S., and Athreya, V. (2017). Leopard in a tea-cup: a study of leopard habitat-use and human-leopard interactions in North-Eastern India. PLoS ONE 12:e0177013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177013

Landry Yuan, F., Ballullaya, U. P., Roshnath, R., Bonebrake, T. C., and Sinu, P. A. (2020). Sacred groves and serpent-gods moderate human–snake relations. People Nat. 2, 111–122. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10059

Landy, F. (2017). “Urban leopards are good cartographers: human-non human and spatial conflicts at Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Mumbai,” in Places of Nature in Ecologies of Urbanism. eds A. Rademacher and K. Sivaramakrishnan (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press), 67–85.

Li, J., Wang, D., Yin, H., Zhaxi, D., Jiagong, Z., Schaller, G. B., et al. (2014). Role of tibetan buddhist monasteries in snow leopard conservation. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 28, 87–94. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12135

Linnell, J. D. C., Cretois, B., Nilsen, E. B., Rolandsen, C. M., Solberg, E. J., et al. (2020). The challenges and opportunities of coexisting with wild ungulates in the human-dominated landscapes of Europe's anthropocene. Biol. Conserv. 224:108500. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108500

Maharashtra Forest Department (2021). Protected Areas. Available online at: https://mahaforest.gov.in/index.php/Contentpage/index/Ri9vMW8raGFWdjVRWmc9PQ%3D%3D/en (accessed March 7, 2021).

Maharashtra Government (2018). Districts. Available online at: www.maharashtra.gov.in/1128/Districts (accessed March 7, 2021).

Mathur, N. (2016). Paper Tiger: Law, Bureaucracy, and the Developmental State in Himalayan India. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

McIntosh N., Maly, K, and, Kittinger, J. N. (2014). “Integrating traditional ecological knowledge and community engagement in marine mammal protected areas,” in Whale-watching; Sustainable Tourism and Ecological Management eds L. Bejder, J. Higham, and R. Williams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 163–174.

McKay, J. E., St. John, F. A. V., Harihar, A., Martyr, D., Leader-Williams, N., Milliyanawati, B., et al. (2018). Tolerating tigers: gaining local and spiritual perspectives on human-tiger interactions in sumatra through rural community interviews. PLoS ONE 13:e0201447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201447

Messmer, T. (2000). The emergence of human–wildlife conflict management: turning challenges into opportunities. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 45, 97–102. doi: 10.1016/S0964-8305(00)00045-7

Miller, J. R. B., Linnell, J. D. C., Athreya, V., and Sen, S. (2017). Human-wildlife conflict in india: addressing the source. EPW 52, 23–25.

Mishra, C., Young, J. C., Fiechter, M., Rutherford, B., and Redpath, S. M. (2017). Building partnerships with communities for biodiversity conservation: lessons from Asian mountains. J. Appl. Ecol. 54, 1583–1591. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12918

Narayanan, Y., and Bindumadhav, S. (2019). “Posthuman cosmopolitanism” for the anthropocene in India: urbanism and human-snake relations in the Kali Yuga. Geoforum 106, 402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.04.020

Newman, P. (2012). Tracking the Weretiger: Supernatural Man-Eaters of India, China, and Southeasr Asia. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company Inc., Publishers.

Nijhawan, S., and Mihu, A. (2020). Relations of blood: hunting taboos and wildlife conservation in the idu mishmi of Northeast India. J. Ethnobiol. 40, 149–166. doi: 10.2993/0278-0771-40.2.149

Oppitz, M., Kaiser, T., von Stockhausen, A., and Wettstein, M. (2008). Naga Identities: Changing Local Cultures in the Northeast of India. Ghent: Snoeck Publishers.

Parathian, H. E., McLennan, M. R., Hill, C. M., Frazão-Moreira, A., and Hockings, K. J. (2018). Breaking through disciplinary barriers: human-wildlife interactions and multispecies ethnography. Int J Primatol. 39, 749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10764-018-0027-9

Pimpale, S. S. (2015). Waghoba-a large cat deity: understanding tolerance toward felids among rural populations in Maharashtra and Goa, India (Master's dissertation). Savitribai Phule University, Pune, India.

Pink, S., and Morgan, J. (2013). Short-term ethnography: intense routes to knowing. Symb. Interact. 36, 351–361. doi: 10.1002/symb.66

Pooley, S., Barua, M., Beinart, W., Dickman, A., Holmes, G., Lorimer, J., et al. (2017). An interdisciplinary review of current and future approaches to improving human–predator relations. Conserv. Biol. 31, 513–523. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12859

Quammen, D. (2004). Monsters of God: The Man-Eating Predator in the Jungles of History and the Mind. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company.

Rapport, N., and Overing, J. (2000). Social and Cultural Anthropology: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge.

Redpath, S. M., Bhatia, S., and Young, J. (2015). Tilting at wildlife: reconsidering human–wildlife conflict. Oryx 49, 222–225. doi: 10.1017/S0030605314000799

Redpath, S. M., Young, J., Evely, A., Adams, W. M., Sutherland, W. J., Whitehouse, A., et al. (2013). Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends Ecol. Evol. 28, 100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.08.021

Shaffer, C., Milstein, M., Suse, P., Marawanaru, E., Yukuma, C., Wolf, T., et al. (2018). Integrating ethnography and hunting sustainability modeling for primate conservation in and indigenous reserve in Guyana. Int. J. https://link.springer.com/journal/10764 Primatol. 39, 945–968. doi: 10.1007/s10764-018-0066-2

Shull, E. M. (1968). Worship of tiger-god and religious rituals associated among dangi-hill tribes of Dangs-district, Gujarat-State, Western India. East. Anthropol. 21, 201–206.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books.

Sultana, F. (2007). Reflexivity, positionality, and participatory ethics: negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 6, 374–385.

Surve, N., and Ahmed, A. (2017). Mumbai Leopard: Monitoring Density and Movement of Leopards Within Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Along its Periphery. A report submitted to the Maharashtra State Forest Department in January 2018. Wildlife Conservation Society-India.

Tie, Y. C., Birks, M., and Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: a design framework for novice researchers. Sage Open Med. 7, 1–8. doi: 10.1177/2050312118822927

Turner, N. (2014). Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America. Montréal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Vasan, S. (2018). Consuming the tiger: experiencing neoliberal nature. Conserv. Soc. 16, 481–492. doi: 10.4103/cs.cs_16_143

West, P. (2005). Translation, value, and space: theorizing an ethnographic and engaged environmental anthropology. Am. Anthropol. 107, 632–642. doi: 10.1525/aa.2005.107.4.632