- 1Institute of Communication and Media Studies, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Germany

- 2DekaBank Deutsche Girozentrale, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- 3Lautenbach Sass, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Purpose: The article introduces and evaluates a method for applying a new management tool for corporate communications and public relations: the Communication Business Model (CBM).

Design/methodology/approach: The conceptual development of a multidimensional method for identifying, analyzing, and assessing business models of communication departments is combined with an evaluation study providing empirical findings from a pilot project with 53 communication departments.

Findings: The results of the study show that the CBM approach works in practice, as four distinct business models could be identified. The validity of the proposed assessment method is substantiated. Prerequisites, obstacles, and success factors for using the method are identified.

Research limitations/implications: The article reports about the first application of the business model approach – a well-known concept in general management – to communication departments. However, as the findings refer to a pilot study, future research is required to test and validate the tool in a wider range of organizations and contexts.

Originality/value: The study shows how research in the field of communication management and public relations can be translated into practice and how the success of such efforts can be evaluated. Developing, applying, and testing a method for using a management tool that addresses a long-standing leadership challenge helps communication leaders apply theoretical knowledge to their daily work.

1 Introduction

Within communication science, the field of communication management and public relations is gaining in importance – not least because the importance of building positive images, dealing with fake news and promoting innovation in deeply mediatized societies has grown (Hepp, 2020). Growing efforts for professional communication, on the other hand, raise the question of how communication creates value for organizations (Buhmann and Volk, 2022). Academic and professional discourse on this topic is extensive, but essentially limited to explaining value creation through communication at a conceptual level by outlining the impact of communication activities on intangible assets such as reputation, relationships or corporate brands (e.g., Balmer and Greyser, 2006; Grunig et al., 2002; Van Riel and Fombrun, 2007). The question how value can be created in practice and how communication practitioners can act strategically in their daily work is largely neglected (Andersson, 2023). A small but growing body of knowledge has addressed this gap in recent years. Communication scholars following this route (e.g., Aggerholm and Asmuß, 2016; Frandsen and Johansen, 2010; Gulbrandsen and Just, 2016, 2022) are inspired by strategy-as-practice approaches in management studies that pays attention to strategy-making or strategizing. Strategizing is ‘the making of strategy’. More precisely, it refers to the “detailed process and practices which constitutes the day-to-day activities of organizational life and which relate to strategic outcomes” (Johnson et al., 2003, p. 14).

An integral part of strategizing is the use of management tools that translate abstract theories or concepts into actionable frameworks. They are defined as “methods, frameworks, or standardized procedures that support managers in solving problems in a structured manner” (Buhmann and Volk, 2022, p. 481) or simply as “support mechanisms in decision-making” (Volk and Zerfass, 2020). Recently, business models – a concept well-established in management science – have been introduced as a promising approach to articulate and optimize the strategic role of communication departments. The Communication Business Model (CBM) provides a framework that helps communication departments to map and analyze the key elements of their operations, including resources, activities, products, and value creation, and understand their interrelationships. We have explained this approach elsewhere in more detail (Zerfass and Lautenbach, 2022; Zerfass and Link, 2024).

Initial feedback from academia and practice has shown that the approach seems quite promising, but it remains unclear whether and how it can be used in the profession. Implementing management tools requires empirical methods and didactic concepts that enable communication leaders and practitioners to use them properly, as outlined by strategy-as-practice scholars in general management (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2015).

An important research gap that needs to be filled to realize the leap in the debate on value creation through communications is therefore to show how a conceptual framework – the CBM – can be systematically applied to managing communications and public relations in real-world organizations. This requires the development and testing of methods that are both research-based and practice-oriented.

To answer this overarching research question, we (a) developed a multidimensional method for identifying and assessing business models in communication departments based on the Communication Business Model (CBM) approach; (b) tested the method in a pilot study with 53 communication departments (from larger departments to smaller teams) in one industry in Germany; (c) evaluated the method in focus group sessions and individual interviews.

2 Literature review and theoretical background

2.1 The Communication Business Model (CBM) approach

Communication departments have received little attention as a unit of analysis so far. This is somehow surprising, as resources and expertise for communications in organizations are allocated there. The business model approach helps to address this challenge as it allows to describe the basic principle of how such a unit operates, what services and products it provides, how it creates value for an organization, and what revenues and resources are allocated (Zerfass and Link, 2024).

When transferring the business model concept to communication departments, some systematic differences should be acknowledged. Firstly, products and services are not provided for external customers but for the organization itself, i.e., for other departments or divisions. Thus, activities and their results must be valuable to those internal clients. Secondly, with a few exceptions (shared service centers; licensing income for brands, etc.), value is not created at the level of the communication department, but elsewhere in the organization. This places specific demands on the allocation of expenses and income.

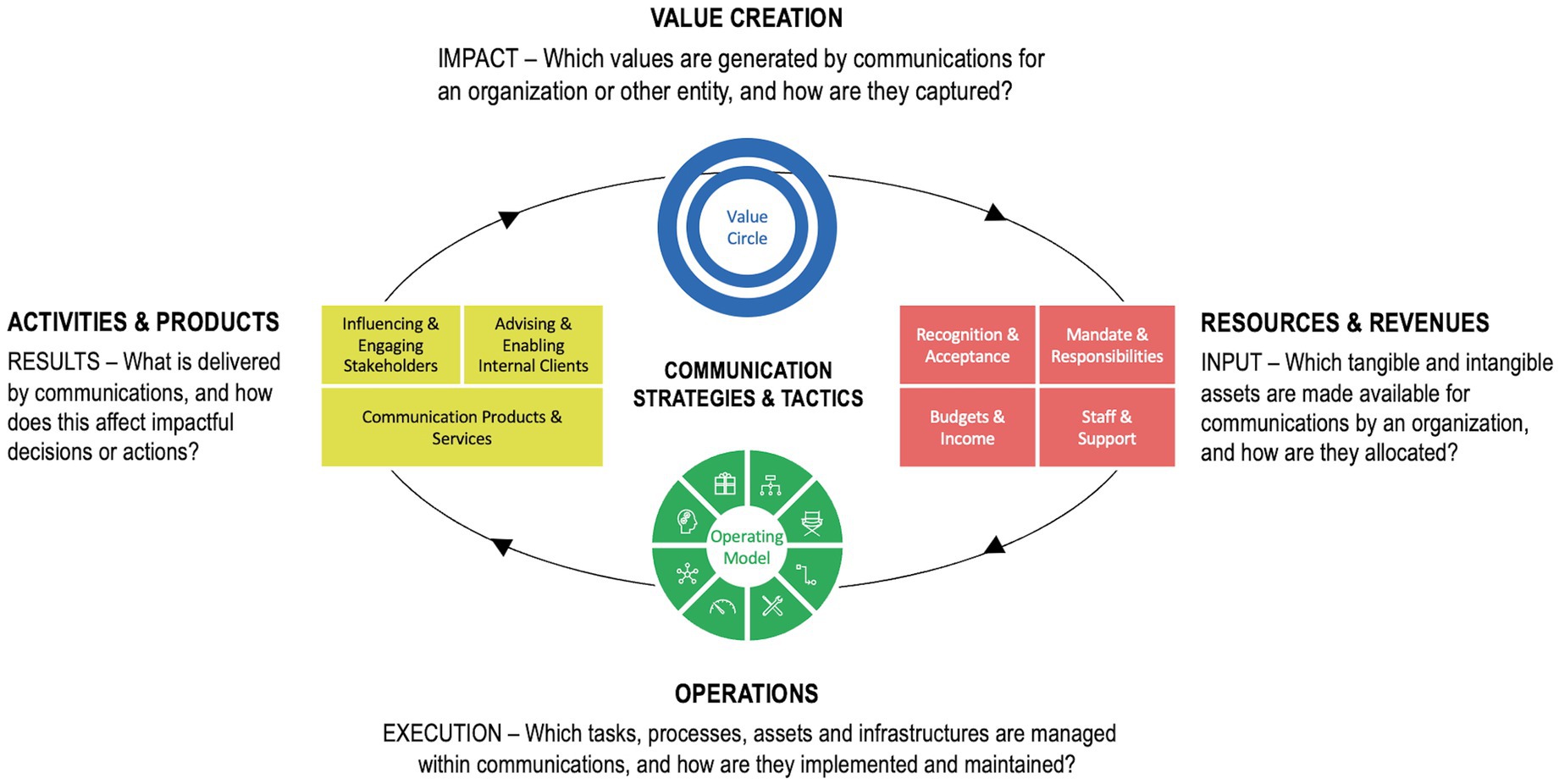

The framework shown in Figure 1 outlines the generic architecture of business models for communication departments. The Communication Business Model is a management tool that can be applied to communication units on various levels of an organization, e.g., for a global communication department in the headquarter, a communication department in a business division, or in a country subsidiary. It comprises four elements that help to describe, discuss, and further develop the entire value creation process of such an entity: from the provision of the required resources by the organizational management or internal clients (input), to the combination and transformation of resources (execution) and the resulting activities and products (results), to the intangible and tangible values that are thereby created for the organization (impact). The CBM also maps whether and how this value creation influences or increases the provision of resources for the communication department and its staff. This is the revenue component at the heart of any business model.

Figure 1. The four sub-models of the CBM [(Zerfass and Link, 2024, p. 393) / Source: Leipzig University and LautenbachSass].

The CBM consists of four sub-models:

1. The resource and revenue model specifies which tangible resources (budgets, internal billing costs, staff positions, rooms and facilities, technology) and intangible resources (in general: internal recognition and acceptance; specifically: mandates and responsibilities) are made available to a communication department. It further describes how the department, and its staff benefit from the success of its work, which is captured as revenue.

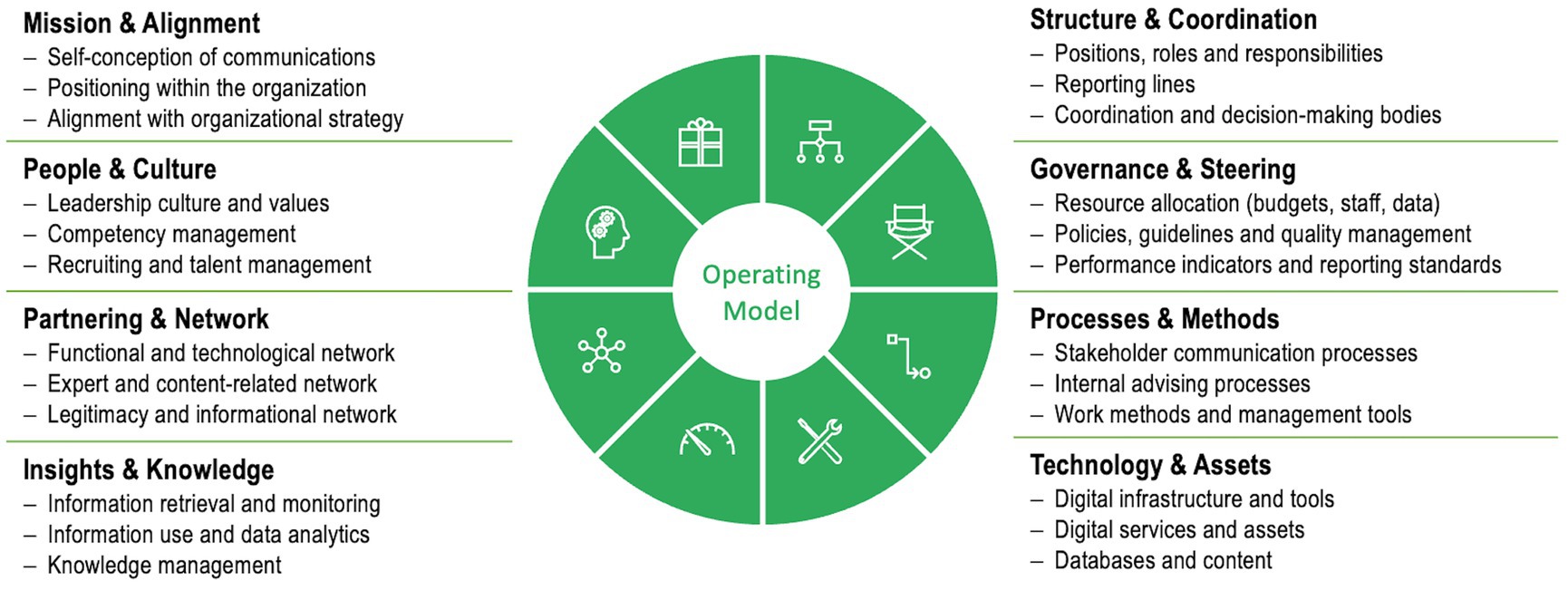

2. The operating model (Figure 2) defines how a communication department manages, implements, and continues to develop its tasks, processes, assets, and infrastructures. This includes organizational structures and coordination routines, governance, leadership culture, competence development, the management of partner networks and knowledge (including analytics), work processes (e.g., content management, campaign management, internal coaching) and management tools, but also the digital infrastructure and the management of texts, audio-visual content, contacts, data and brand rights.

3. The activities and product model describes which products (such as content in various formats, social media channels, publications, trade fair presentations, events, branding manuals) and services (such as issues monitoring, media training, internal consulting) are offered by a communication department. It further explains how these communication products and services are supposed to change the knowledge, attitude or behavior of stakeholders or internal clients in such a way that their future decisions or actions have a positive impact on organizational goals.

4. The value creation model explicates which values the communication department delivers through its activities for the overall organization or for internal clients. This is used to outline and specify the value proposition. Here, the authors of the CBM approach have integrated an existing, research-based approach already used by several global companies: the Communication Value Circle (Zerfass and Viertmann, 2017). It systematizes communication goals holistically in twelve dimensions (employee commitment, customer preferences, publicity; reputation, brands, corporate culture; topic leadership, innovation potential, crisis resilience; legitimacy, trust, relationships) and links them to four generic dimensions of corporate, business or functional goals (supporting the production of goods and services; building up intangible capital; further developing the strategy; securing the company’s reputation, securing flexibility).

Figure 2. Dimensions of the operating model for a communication department [(Zerfass and Link, 2024, p. 395) / Source: Leipzig University and LautenbachSass].

2.2 Using management tools to enable strategizing in practice

Research into the use of management tools has a long tradition. Many studies take a more instrumental and normative view of how tools are being used and which tools are suitable for which situation or challenge (Volk and Zerfass, 2020). The strategy-as-practice perspective has shifted this focus to how and why managers adopt tools, also taking into account social and (micro-) political dynamics within organizations. Strategizing is then seen as both a “deliberate and non-deliberate activity […] informed by the social practices people carry and participate in as they carry out their work” (Andersson, 2023, p. 2). Recent work, such as Volk and Zerfass (2020), highlights the role of management tools in supporting strategizing within communication units. The state of research on strategizing in communication management reflects a growing but underdeveloped area. While general management has extensively studied strategizing as a process of strategy formulation and implementation, its application in communication departments has been less thoroughly investigated. Existing frameworks focus on broad organizational contributions but often neglect how communication units align their strategic actions with corporate priorities. Communication departments usually manage different tasks varying from developing and executing campaigns to maintaining human resources, infrastructure, and budgets. Such tasks require profound knowledge of business acumen (Ragas and Culp, 2021) and the competence to use suitable management tools when needed (Stöger, 2016).

Management tools, like business models, provide practitioners with actionable frameworks to connect resources, processes, and outcomes. However, Volk and Zerfass (2020) identify challenges, such as limited familiarity with these tools and a lack of tailored methodologies. Empirical research has revealed that communicators tend to have a different, more operational understanding of the term “tool” as they often associate it with digital services or project management tools (Volk and Zerfass, 2020). Very few seem to have the prevalent understanding of management tools as “thinking tools” that provide frameworks and procedures to structure and solve complex problems in the social world. The aforementioned empirical study showed that tools have gained importance for communication leaders, but only few companies use and document tools systematically (Volk and Zerfass, 2020). It also revealed that easy-to-implement tools such as editorial plans, budget plans or mission statements are preferred by communicators. Although more complex analysis tools are rated as very satisfactory, they are used less often. Thus, high effort can act as a deterrent for implementation.

This is in line with the findings of Bolland (2020), who argues for combining analytical frameworks with adaptability to the real world. Another study from general management research indicates that the distribution and significance of tools can change over time (Rigby and Bilodeau, 2018), meaning that also more complex tools find their way into practice. Aggerholm and Asmuß (2016) emphasize the dialogical and interpretive dimensions of strategy-making, suggesting that communication strategizing is a dynamic, interactive process rather than a rigid top-down directive. Through ethnographic fieldwork the authors illuminate organizational practices by analyzing micro-interactions that legitimize actions as institutionalized practices, emphasizing how strategic actions are shaped by context, time, and space.

The use of management tools can be worthwhile for communication departments in several ways. By using management tools, they demonstrate rationality and promote the acceptance of their department among top management and internal clients. Thus, their own position and standing can be improved. The collection and documentation of such methods is also an important prerequisite for further development and professionalization. Tools never provide patent solutions, but rather food for thought and implementation aids, from which solution approaches can be derived. At best, they are integrated into existing processes and structures (March, 2006).

3 A multidimensional method to identify business models of communication departments

The CBM has been introduced as a comprehensive management tool that allows communication departments to analyze their work and their own actions. However, the implementation of such a complex approach is usually fraught with obstacles. Applying management tools requires empirical methods and didactic concepts that enable communication leaders and practitioners to use them properly, as outlined by strategy-as-practice scholars who have studied the use of tools in general management (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2015).

To answer our research question, we first focused on the conceptual development of a method for implementing the new management tool. Initially, there were no limitations – we considered a wide range of existing knowledge and instruments. Just as a management tool must fit the goals of the decision-makers that apply it, the methods must fit the issue being addressed. We therefore addressed the question of which methods represent the best possible translation of the four CBM sub-models and their dimensions and are thus most suitable for identifying business models in communication units. The methods under consideration had to fit the theoretical considerations. At the same time, ease of implementation in practice was important. In several rounds of discussion with researchers and consultants experienced in benchmarking communication departments, various options were weighed against each other before a multidimensional method was developed.

3.1 A self-assessment approach for identifying business models

As described, there are some particularities in transferring the business model approach to communication departments. Since products and services are not provided for external customers but for the organization itself, it would have been difficult to identify the business model of a communication department based on an external analysis. Therefore, a look inside the organization is essential. Focusing on the individual sub-models of the CBM, it becomes evident that the information needed is sometimes difficult to grasp. This is apparent, for example, when the operating model and the associated internal processes are to be described and evaluated.

Referring to the strategy-as-practice discourse in general management and communication management (e.g., Aggerholm and Asmuß, 2016; Andersson, 2023; Bolland, 2020; Volk and Zerfass, 2020) we considered a variety of methods for our research. In his book on strategizing Bolland (2020) reviews the most common approaches for strategy-making, such as structured interviews, scenario development or cooperation with consulting firms. He proposes various criteria to check whether management tools are suitable for strategizing. In addition to general acceptance and practicability, he sees clarity of results, cost efficiency and time efficiency as important factors for evaluating a tool. In addition, managers should be aware of the proposed frequency of use and the associated risks, i.e., the validity and reliability of the tool (Bolland, 2020, p. 151).

For our investigation, data retrieved from document analysis or technical analysis would have been a solid starting point. However, these numbers are seldom tracked and available in communication units. As the individual elements of the CBM ultimately aim to analyze the work and value creation of communication department, it seems to make sense to interview those who do this work on a daily basis. We therefore decided to develop a joint self-assessment, addressing the micro level of organizational practices and co-creational aspects of the usage of management tools.

In a self-assessment, people are asked to make a judgment about their own abilities, characteristics, or actions. Leaders and team members of a communication department know about their department and their organization; they are in the best position to assess each dimension of the CBM. Of course, not everyone will know ad hoc how the department is gaining resources, providing services, creating value, and making profits. But it seems useful to think about it together and reveal the tacit knowledge that shapes daily work. In a department organized based on division of labor, everyone takes on certain tasks and can contribute their part to answering the self-assessment. In this way, different ways of thinking and points of view can be brought together in a joint cognitive process.

At the same time, a self-assessment has the advantage of minimizing aspects of social desirability that are linked to alternative methods like interviews. People tend to present themselves in a way that is socially acceptable (Bergen and Labonté, 2020) and are often unwilling to report accurately on sensitive topics (Fisher, 1993). A joint assessment allows teams to reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of their routines and performance in an intimate atmosphere. To this end, it is important to ensure that supervisors cannot use such insights to draw conclusions about the work of individuals. In order to reduce such fears, self-assessment data should be analyzed by a trusted external party and results should only be reported in an aggregated way. On the practical edge, collecting data through self-assessments is more flexible and requires less organizational effort, compared to interviews or focus groups conducted by external analysts. Communicators can integrate the time needed in their busy team schedules and will be able to shift it if necessary.

3.2 Elements of the proposed method

To identify existing business models for communication departments, an assessment method with several instruments was developed that minimizes the involvement of external analysts and builds on the commitment of the participating communicators.

1. First, data and facts about the communication unit and organization should be gathered in written form. The unit heads are asked to provide basic data on the organization (e.g., locations, products and services, key markets, customers and clients, number of employees) and the communication unit (number of employees, composition of the budget, other units with communication tasks within the organization). Furthermore, the mission of the communication units should be documented, which includes the role of the communication unit, its responsibilities, and main tasks.

2. Second, a self-assessment describing the four elements of a business model for communications in multiple dimensions was developed. It culminated in a questionnaire with a total of 83 statements. For each statement, the communication teams were asked to rate the status of their unit on a five-point Likert scales (1 = not true at all; 5 = completely true) and to add a qualitative comment, highlighting specific practices, challenges, or achievements in the respective dimension.

The resource and revenues model was operationalized using four dimensions, each comprising three statements: (1) recognition and acceptance (e.g., “The organization’s management and other decision-makers have a clear understanding of the contribution of communications to the success of the organization.”), (2) mandate and responsibilities (e.g., “The general responsibilities of the communication unit within the organization are clearly defined.”), (3) staffing and support (e.g., “The staffing of the communication unit is sufficient to perform the assigned tasks well.”) and (4) budgets and income (e.g., “The communication unit receives an annual budget of sufficient size to perform the assigned tasks well.”).

The second section of the questionnaire focused on the operating model, which was the biggest section due to its eight dimensions. For each dimension, five statements needed to be rated: (1) structure and coordination, (2) governance and steering, (3) processes and methods, (4) technology and assets, (5) insights and knowledge, (6) partnering and network, (7) team and culture, and (8) mission and alignment.

The activities and product model was operationalized by means of three dimensions, each with five statements: (1) communication products and services [e.g., “The communication unit offers internal services for the organization’s management and other internal decision-makers in a contemporary manner (e.g., media training, issue analysis, advice on business policy or content decisions).”], (2) influencing and engaging stakeholders (e.g., “Overall, the communication unit is a central contact within the organization for managing stakeholder relationships.”) and (3) advising and enabling internal clients (e.g., “Overall, the communication unit is the key contact within the organization for communication trends, public opinion building, and societal developments.”).

The fourth sub-model (value creation) comprised four dimensions with four statements each and was thus surveyed using 16 items. In terms of (1) enabling operations, for instance, the statement “Overall, the services provided by the communication unit make a positive contribution to the ongoing success of the organization and thus to the current value added” is to be evaluated. Similarly, the value contribution to (2) building intangibles, (3) ensuring flexibility, and (4) adjusting strategy is to be assessed.

(3) Third, an elevator pitch was developed to invite communication teams to describe the business models of their departments in a structured way in a few sentences. The participants were asked to imagine the following situation: “A new top executive takes a tour of the building on the first day and happens to meet you at the coffee machine. You are asked what exactly your communication department does and how it can support the organization’s continued success. How do you explain that in a nutshell?”

Five questions need to be answered here: (1) What is our mission within the organization and from whom do we get our resources (resources)? (2) How does our communication unit work (operating model)? (3) What specific outputs (products and services) do we create and for whom (outputs)? (4) How do we contribute to the success of the organization and what values do we create (value creation)? (5) How do we, as a communication unit, benefit from the success of our work for the organization (revenues)?

To support reflection and data collection, an interactive workshop with gamification elements was developed. It was up to the teams whether to use the workshop design or alternative ways, which ensures maximum flexibility. We developed a digital whiteboard using Miro software as well as a paper canvas and action cards for each of the four sub-models (Figure 3). A canvas is a management template. It helps to visualize business models (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010) and stimulates an interactive discussion. Action cards support participants in the discussion through provoking questions or small exercises. Overall, two workshop sessions of three to four hours each were recommended for the self-assessment. The four sub-models could be discussed in any order. Results had to be noted and transferred into the written questionnaire in the next step.

4 Application of the method in a pilot study

In a next step, the presented method was implemented and evaluated to see if it works in practice. It was applied in a pilot study with communication units in 53 organizations. The authors assisted in implementing the CBM and monitored the whole process; the pilot project was implemented by a team of specialized consultants. The data was collected over a period of two months in the summer of 2021 and analyzed thereafter.

4.1 Implementation: analyzing 53 communication departments

The 53 organizations operate as applied research institutes in different markets across Germany. They pursue comparable goals and they work closely together under a joint brand in a network of currently 76 institutes with almost 32,000 employees overall. Each communication unit of the 53 organizations went through the self-assessment and was provided with a material kit including the written questionnaire, instructions with detailed information on the data collection process and tips for the implementation of the workshop in the team, printed copies of the workshop documents as well as an online version of the canvases for the workshop participants. Each communication unit appointed a moderator for the workshop sessions from their own team; they were briefed by the consultants. The whole process was assisted by the consultants who supported as needed and offered a help desk for communicators applying the method. During the individual data collection, three digital consultation hours were offered, to share experiences between the communicators and to clarify ambiguities and questions about the methodological procedure.

4.2 Results: identification of four distinct business models

Overall, the pilot study has shown that the conceptual approach works in practice and that the CBM can be used as a communication management tool. The findings from the pilot study do not only refer to the business models as such, but also to the applied method itself. The self-assessment allowed for a structured self-reflection and systematic analysis of the entire performance process of communications across all organizations in the pilot study. The data were evaluated and interpreted by the consultants; a final report was prepared that identified gaps and suggests options for action. The results were discussed with the leaders of the communication units in a workshop. Follow-up activities were developed and implemented in several participating organizations.

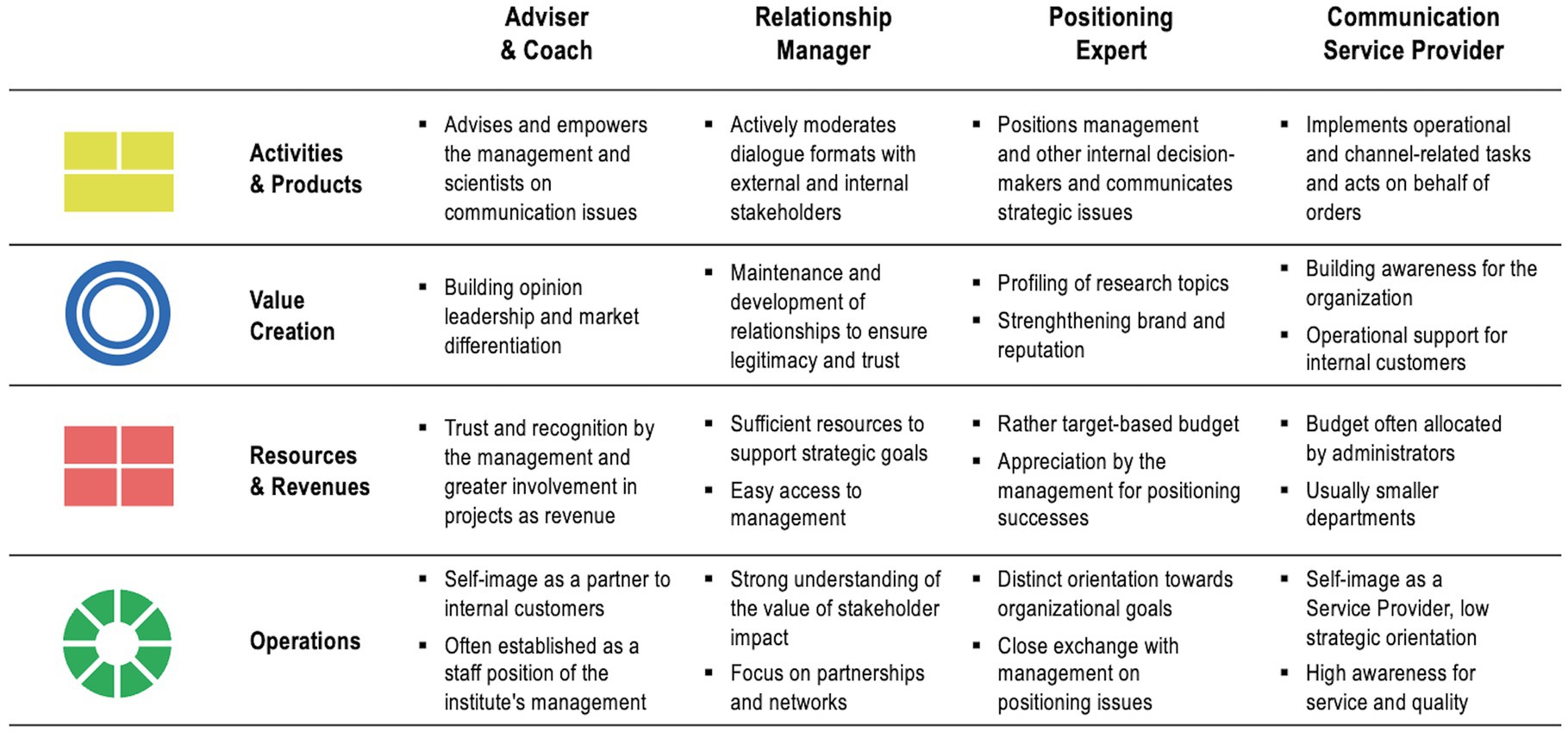

By applying the described method, four types of business models for communication departments were inductively identified in the sample. Based on the dominant orientation of the units, they can be described as Adviser & Coach, Relationship Manager, Positioning Expert, Communication Service Provider (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Business models of communication departments identified in the pilot project (Source: Authors).

The pilot study revealed that the majority of the analyzed communication departments adhere to the Communication Service Provider model. They focus on creating content, arranging events and supporting their top management with communication skills, while influencing or advising internal clients is less relevant. Comparatively fewer act as Positioning Experts: they often attempt to influence the acceptance of their organization in politics and society through thought leadership activities. The Relationship Management business model with a strong focus on maintaining favorable relationships with key stakeholders as a prerequisite of organizational success is also not very common. Despite the volatile and dynamic environment of the industry at hand, only a few communication departments in the sample explicitly position themselves as enablers of success through advising, coaching and empowerment (Adviser & Coach).

The business models identified may be found in other industries as well. But there will also be other approaches as this solely depends on what was intentionally planed or emerged by communication leaders and their team. Irrespective of the core characteristics of the business models at hand, the pilot study showed that many departments claim to offer services or create value without having suitable workflows in place. Others implement routines or technologies in their daily operations to raise efficiency but de-couple such efforts from the prioritization of deliverables and the value proposition for internal decision-makers. Last but not least, a clear understanding of resources and revenues and how they are aligned to other parts of the department’s business model was scarce.

4.3 Critical reflection and research questions

The results of the pilot study show that the approach basically works, and that the implementation of the CBM management tool was successful. In a further step, the assessment was evaluated to identify possibilities for improvement and further development of the approach and the method. This was investigated by answering the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the strengths and weaknesses of the Communication Business Model approach as a management tool?

RQ2: What are the strengths and weaknesses of the multidimensional self-assessment method?

RQ2a: What are the success factors and obstacles of the method?

RQ2b: How can the method be further improved?

5 Outline of the evaluation study

To evaluate the method and answer RQ1 and RQ2, a qualitative approach was chosen to achieve a high level of insight and to get as much detail as possible. In March and April 2022 semi-structured in-depth interviews with two mini-focus groups and three individuals were conducted digitally via Microsoft Teams. Focus groups normally consist of six to nine persons, who discuss a certain issue or topic and are supervised by a moderator (Palmer, 2019). However, mini-focus groups can be beneficial when topics need to be explored in greater depth (Palmer, 2019, p. 71). They allow to combine the advantages of one-on-one interviews, and still profiting from the dynamics of a group discussion (Sage Publishing, 2012).

The interviews were held with (a) heads of communication departments involved in the pilot study (representing project managers interested in the use of management tools); (b) communicators involved in the team workshops (representing practitioners whose knowledge and experiences are needed to apply the method); and (c) consultants (who steered the process and applied the method). The project managers (n = 3) were interviewed individually, as they had different roles (project manager, initiator of the project, strategy officer) and thus different valuable insights into the project. The communicators (n = 5) were interviewed in a mini-focus group since they all completed the self-assessment but implemented it differently in their organizations. This enabled a lively discussion in which different aspects could be deliberately contrasted. The consultants (n = 3) were also interviewed in a mini-focus group to reflect on their different roles and associated tasks.

The interviews and focus groups were structured based on specific guidelines for the three groups. The guidelines comprised the following blocks: (1) objectives of testing the method in a pilot study; (2) implementation and evaluation of the method; and (3) implications in terms of further use of the method for mapping and discussing the work of the communication unit.

6 Results

Members of the assessed organizations (project managers and communicators) and consultants were asked to reflect on the Communication Business Model approach (as a management tool) as well as on the self-assessment (as method). Insights from the three perspectives were triangulated to evaluate the approach and the method. Based on the interviews, strengths and weaknesses of the approach and the method were identified. Furthermore, the data shows which requirements should be met when implementing the self-assessment and which obstacles can occur. Last but not least, the evaluation study revealed how the method could be optimized.

6.1 Strengths and weaknesses of the Communication Business Model approach as a management tool

Overall, the CBM was evaluated as a useful method by communicators, project managers, and consultants. One strength of the tool lies in its capability to reflect on one’s own work. From the project managers’ point of view, the CBM serves as a framework with consistent dimensions and criteria that can be applied to all kinds of communication units throughout the organization, in the global headquarter as well as in larger and smaller entities. According to the members of the organization, the approach allows a thorough analysis of the resources, capacities, and performance of the communication units. One project manager summarized the tool’s benefits:

“The intention [of the project] was to highlight the contribution that [communication units] make in their daily work to acquire resources for the organization, both directly and indirectly. In the sense of: What kind of business models are they hiding behind? Are they just coaches? Are they just service providers? Are they just consultants? Are they just recipients of orders […]? […] What are they doing?”

The business model approach allows not only the evaluation of the activity of a particular entity, but also the comparison with other communication units. Units with different sizes and budgets can be compared by using consistent measurements. The communicators saw the use of the approach as an opportunity to compare themselves with other units and to review how others position themselves on certain issues and set out their priorities. One interviewee emphasized that it is particularly exciting to see to what extent other units perceive the internal recognition of their department. The project managers stated that the distinctions between the corporate level at the headquarter and the decentralized units are very interesting. At the same time, the approach offers a high degree of comparability between the heterogeneous communication units.

When asking the communicators for the reasons they participated in the pilot study, one of the most important reasons mentioned was internal positioning. They reported that communication departments often do not receive sufficient recognition from internal clients, thus, they strive to make their own performance visible. The CBM approach allows them to show what they are delivering and how they contribute to value creation. According to the communicators, the approach provided them with specific arguments for why communication is important and valuable. By explaining their work to decision-makers, they hoped to gain more visibility and appreciation.

Moreover, the CBM approach can also be used for external positioning. The project managers said that the implementation of a well-designed management tool developed by renowned experts in the field can be beneficial for the organization’s brand. The scientific foundation of the approach underscores the quality of the results for internal and external stakeholders. Besides this reputational factor, all interviewees valued that the different perspectives of researchers, consultants and communicators were already taken into account when developing the management tool.

According to a consultant, the CBM is also characterized by the fact that it helps to take another perspective than most other communication management tools. The business model framework closes a gap in theory and practice by focusing on the value contribution of communications, taking a managerial perspective. The approach helps to systematize the value contribution of communication units from a superior perspective by checking whether communications meet the expectations of top management. A consultant summarized this by saying:

“[…] that is a crucial keyword, that you start thinking client-oriented. In other words, thinking about the money providers, the resource providers. We want to know exactly what they actually expect from us and then, secondly, we want to check to what extent our activities as a communication unit meet this mandate in all relevant dimensions, or whether we need to change to meet the mandate.”

6.2 Success factors and obstacles of the method

As outlined, the communication units were able to decide on their own how to implement the self-assessment. They had various instruments and support services at their disposal, such as paper canvases, digital whiteboards, and a help desk run by the consultants. The results show that the self-assessment was applied rather differently, and the services were used spontaneously when they were needed. Some communication units distributed the questionnaire to their team members by email, others held one or more workshops and used canvases to answer the questionnaire. Nevertheless, the interviewees reported several prerequisites, obstacles and success factors that should be considered when adopting the management tool in the future.

When implementing the self-assessment, the appropriate technological, structural, and personnel preconditions should be created within the organization. The communicators stated that technology was less of a problem. A project manager said that the choice of a suitable collaboration software for working on canvases was important at the beginning because this allows an exchange, regardless of whether people work through the self-assessment in presence or digitally. The chosen software, Miro, fulfilled the desired purposes. In addition, a suitable information infrastructure had to be created, as indicated by a project manager. This was to ensure that all communication departments were informed about the project. An important part of this information infrastructure were multipliers within the organization who stimulated their peer communicators to participate in the self-assessment and answered questions when needed. These multipliers were usually the heads of communications in the respective units or communicators nominated by them.

The project managers considered the motivation and preparation of the communication departments for the self-assessment to be the most important prerequisite for the success of the method. One project manager felt that the activation phase was crucial for being able to foresee which formats would be needed by the departments to achieve the highest possible level of participation. Furthermore, the project managers noted that their function in the project was mainly to create trust and reduce fears. Critical voices were occasionally raised, especially at the beginning of the project. Mostly, this concerned the question of who would ultimately see the results and how these would be communicated to the outside world. Some team members were worried that conclusions could be drawn on their personal performance. Not least for this reason, the transparent communication of the objectives of the self-assessment and trust-building is very important for the success of the method. One project manager summarized:

“We had to point out: The results [are all] for you, and we are not doing a big evaluation for everyone, and no board member will get to see that, or something like that. These were fears that had to be addressed and dispelled, and I found that quite interesting. You can see what kind of worries people have [when doing a self-reflection].”

Although the implementation of the self-assessment was successful and positively evaluated, the participants reported some obstacles and challenges. The challenge most frequently mentioned by the members of the organizations involved relates to the time required to go through the process. According to one project manager, this aspect was underestimated by everyone and thus, no realistic briefing was prepared for implementation. From her point of view, it would be very important that the time frame is communicated realistically from the beginning on. Another project manager stated that when it comes to implementation, it is essential to remember that communication departments are under a lot of time pressure and have many other ad hoc tasks to complete. The communicators in the teams usually do not have a nine-to-five job and have to act at short notice. According to this project manager, the added value of the self-assessment should be emphasized repeatedly to keep the motivation in participating high. Communicators also stated that they underestimated the effort for the self-assessment. From their point of view, also the timing of the self-assessment was not perfect as it fell within the summer holiday season.

Difficulties with terminology and academic frameworks is another challenge that was particularly brought up by communicators. In part, this was anticipated, as a glossary of terms was provided, and a help desk offered. But problems arose when applying the instrument because statements in the questionnaire or underlying models were not understood. For example, the project managers noticed that questions about management and strategy terms kept coming up:

“But what was much more complex, and what is always underestimated at headquarters, is that they deal with other terms and other insights into data and information. [Do communicators] really know what is meant by budget share and [what it means in detail]? How do I put this together in the end? When do I speak of full-time equivalents?”

Another project manager explained that with the different backgrounds of the communicators. From her point of view, communicators cannot be expected to use conceptual models, saying “not every colleague leading the self-assessments as multiplier has necessarily been trained in communication science, many are also journalists or event specialists or social media/digital experts […] we could have explained more there.” She recommended going into more depth right at the beginning and allocating time to explain the model and clarify all questions about terms. The project managers reported that they were able to sort out all questions during the project, e.g., in consultation hours, but that they were no longer able to reach all multipliers during the overall process.

An additional problem arose during the self-assessment process. As explained above, 53 communication units took part in the assessment. Some of these were located at different sites and comprise several teams. Communicators indicated that they found it difficult to reach consensus in answering the questions. Depending on the position and role of those involved, discrepancies in perception became apparent. For example, one interviewee reported to be the only employee in his team who held a full-time position and, consequently, from his perspective, also had a better overview on certain issues. He regarded some discussions with his colleagues to be exhausting.

Some communicators criticized the fact that, in the final analysis, mean values had to be given in many cases because it was necessary to reach agreement under the conditions described. According to the communicators, some important discussion points got lost with the number-based rating scales, since it is no longer comprehensible how the mean values came about. One project manager concluded:

“Due to this composition of the different teams, which then had to consolidate on one answer, I’m afraid that a lot of average values were created, which you can no longer differentiate on a purely numerical basis […]. This is perhaps a small fly in the ointment, that you simply no longer know why we are in the middle everywhere, even though there were heated discussions, because certain teams saw themselves on the far left and others on the far right.”

Furthermore, the interviews showed that the self-assessment was partly coordinated with board members or other stakeholders in the respective organization. One communicator admitted that the information was partially adjusted based on this, but that the team still remained honest in its answers. However, the answers were not only coordinated with stakeholders outside the units, but the communicators themselves also used the self-assessment strategically. One communicator said at the beginning of the interview:

“[…] we filled out the questionnaire very strategically. And we filled it out strategically because, of course, we know exactly how this kind of work is read by the relevant decision-makers.”

This same communicator said that his department created two versions of the questionnaire: a version with desirable information that is only accessible internally to the team and a version that positions the unit in front of decision-makers of the organization. Another communicator emphasized that he did not want to be too negative about the perceived recognition of his department. He said:

“That’s why I always found it a bit difficult to say that this has to be rated very low. [I] also have different plans as to what I would like to implement and carry out than someone who is only involved part time in PR. But then, of course, you must sweep it under the rug. You have to represent your own point of view […]. Because otherwise you would not need me. You [might] feel a bit worthless yourself, which I know exactly that I’m not.”

According to all interviewees, several factors contributed to the success of the method. They stated that the trust-based cooperation between all project partners was a main success factor. One project manager spoke of “blind trust” in the inventors of the management tool and to the consultants, who also considered trust to be important in a project of this magnitude.

From a project manager’s point of view, the implementation succeeded because the self-assessment could be flexibly adapted to the organizations involved. In his opinion, other management tools often fail because they are too little customized to the needs of the organization and therefore the gain in knowledge is extremely low.

Another success factor results from the already mentioned reputation of the project partners. This was not only used for external positioning; it also motivated the communication departments to participate. One project manager underscored the scientific foundation of the instruments and the corresponding legitimacy as a concrete success factor. In addition, the support services offered during implementation helped the communication departments. These services were used by the teams to varying degrees. Nevertheless, specifically the help desk was a valuable source of support for many departments according to the project managers. From the consultants’ point of view, their own experience with applied empirical research also contributed to the success of the project.

Overall, members of the assessed organizations and consultants rated the self-assessment method as successful. One project manager summed up the strengths primarily as the high degree of manageability and feasibility. He emphasized that the self-assessment can be used by “anyone without prior knowledge” and is therefore suitable for the corporate level as well as all other levels.

The interviews revealed that the elevator pitch as part of the self-assessment was also viewed positively. Some communicators feared beforehand that it would be another big task on top. But after applying the instrument, they noted that it was a “good exercise” to summarize their own results. All communicators indicated that the elevator pitch fit well into their day-to-day work and was understandable to all.

From the perspective of one consultant, the results of the self-assessment were characterized by high data quality. For the members of the assessed organizations, the results as well as the identified business models provided important starting points for subsequent projects and measures. They reported that they have taken the results as an opportunity to identify areas of action and pain points to be worked on in the future.

6.3 Further improvement of the method

Based on the interviews, it was also possible to identify opportunities for the enhancement of the method. Overall, the self-assessment was evaluated positively by communicators, project managers, and consultants. However, some aspects of the questionnaire were criticized. This concerned on the one hand the length, but on the other hand also the complexity and some formulations. Academically proven terms in particular had to be discussed and interpreted by the participants. While one project manager emphasized the high degree of customizability as a strength of the method, some communicators felt that the self-assessment was not always an ideal fit for the organizations. Thus, in addition to terms, they also had to discuss what meaning certain statements had in the context of their organization.

As described, the communication departments took the results as an opportunity to reflect and to derive fields of action for their area. One project manager stated that some communicators would have wished to receive an even more detailed evaluation for their team.

The project managers and the consultants addressed the fact that the business models were derived inductively. In future studies, a different method could be used, which one project manager illustrated as follows:

“It would also be imaginable in the next round to start with certain business models that we specify and check where the departments could orient toward, where they see themselves more […]. It would require further reflection to define what we want to take away from it and how we want to use it, also vis-à-vis our […] management.”

Although the method helps to take a management perspective, one consultant stated that the alignment between the expectations of management and the business models of the communication units should be highlighted. In his opinion, the mandate of the management is not tackled explicitly, but rather implicitly by the self-assessment method. He considered this to be problematic, as it remains unclear where a unit should develop in the future – from a managerial perspective.

The project managers also addressed this issue and suggest that multiple perspectives should be included in the future to obtain a broader picture. One project manager proposed offering different versions of the self-assessment, e.g., including one part for an internal client of communications that evaluates the dimensions from its point of view, mirroring communications’ performance:

“But I guess all the stakeholders with whom you do this and to whom you want to sell this [self-assessment], you could at least offer an optional variant and hold up this mirror by saying there is one level for further internal stakeholders, another for selected external stakeholders. If you limit this each time to, let us say, three somewhere, then I think it’s still manageable, then it’s also communicable to people internally without, […] creating irrevocable hurdles.”

The aforementioned points give cause for further development of the method. On the one hand, it is necessary to examine whether the self-assessment, in particular the questionnaire, can be simplified. However, this is only possible to a limited extent due to the conceptual framework (the CBM) and the scales that reflect this purpose. It should also be discussed whether questions can be adapted more closely to a specific organization without losing the advantage of a standardized management tool. Future studies could choose a deductive approach as described above and investigate whether and to what extent predefined business models can be found in communication departments.

7 Discussion: advantages, limits, and opportunity for development

The aim of the study was to provide and evaluate a concept for identifying business models in communication departments based on a recently developed management tool – the CBM. To this end, (a) a multidimensional method for identifying business models in communication departments was developed, (b) it was applied for the first time in a pilot study, and (c) it was evaluated from three perspectives.

As the pilot study shows, the methodological design proved successful, as four different business models for communication departments were identified.

In our evaluation study, we wanted to find out how the business model method can be used in practice as a management tool. The results of the interviews show that the method including the self-assessment is a promising approach when evaluating the value contribution of communication departments. The CBM fulfills all relevant criteria for a valid and reliable management tool (e.g., Bolland, 2020). It is based on scientific methods but can be used for practical purposes. One advantage of the method lies in the fact that it is designed as a self-reflection tool and therefore few prior knowledge is required by users. At the same time, clarification of relevant terms is necessary to ensure that communicators understand the instruments. The self-reflection based on the four sub-models of the CBM creates a comprehensive picture of the use of resources, the operational model, the provided services, the value creation, and how all this is connected. When implemented for communication departments within the same industry or organization, the method can create a high degree of comparability.

The approach has several advantages that set it apart from other management tools. In contrast to many other concepts, the CBM takes the perspective of top management. It aims at checking whether the needs of internal clients are met and does not focus on the perspective of stakeholders. Another advantage, which was also emphasized in the interviews, is the self-perceived familiarity of the tool, even if it was new to communicators and project managers alike. Using a well-established management tool and transferring it to the field of communication management seems to be a good idea. Elements such as the elevator pitch fit into the daily business of the communicators, internal clients, and top managers in most organizations.

The tool was also accepted due to the reputation of its initiators. When an organization is implementing a well-known tool, it might be beneficial just because it indicates that the organization makes use of state-of-the-art knowledge and tools.

Nevertheless, the method for identifying business models in communication departments has some limitations. Due to its nature, the method in the pilot study served for self-reflection and ex-post identification of business models. Therefore, the derived business models can provide valuable food for thought and identify internal inconsistencies, but they are not necessarily a starting point for future development. This would require additional methods. It might be useful to include additional parties within and outside the organization by interviewing top management (e.g., about its expectations and satisfaction) or stakeholders (e.g., about satisfaction with communication services). In this way, additional insights for advancing business models of communication departments can be generated.

Another problem that can generally arise with self-assessments of this type relates to the fact that the communicators involved are pursuing their own goals. The micro-perspective of strategizing allows to reflect on these individual motivations, power games and negotiations when management tools are being used in practice (e.g., Aggerholm and Asmuß, 2016; Bolland, 2020; Gulbrandsen and Just, 2016, 2022).

Nevertheless, the strategic use of the instruments can lead to a distorted picture of the status quo of the communication departments. As the interviews show, human fear also comes to light in this context and participants could underreport weaknesses in their unit. This should be sensitively addressed by project managers and consultants involved. Incorporating other perspectives with additional methods could be useful for this purpose as well.

8 Limitations and outlook

Although the evaluation of the CBM approach from three perspectives has yielded many insights, the study is not without limitations. One limitation refers to the method chosen for the evaluation study, for which individual and focus group interviews were conducted. The effect of conformity or social desirability could possibly influence the response behavior of interviewees. This could be the case, for example, in the mini-focus group of communicators who want to position themselves and their department in the eyes of their colleagues. Moreover, findings from those groups cannot be generalized. Deeper insights into how the tool is interpreted and applied might be gained through ethnographic methods such as observational approaches (Aggerholm and Asmuß, 2016).

The application of the CBM in the pilot study focused on the perspective of communication leaders and their teams. They are primary responsible for developing a concise positioning for their department, which means that they will be the predominant users of this management tool in practice. Other actors who might use the CBM include external consultants hired to analyze and restructure a department, or top executives who want to develop a better understanding of those units. This might require different methods for pilot tests. Apart from this, additional insights on the framework could be generated combining findings from different perspectives (Bolland, 2020), e.g., by linking the communicators’ views investigated in this study to results of a similar study among top executives in the same organizations.

Furthermore, the evaluation of the method refers to the pilot study and thus only to one country and one type of organization. Therefore, comparisons and generalizations of the results are not possible yet.

The self-assessment method generated high quality data, which served as the basis for identifying four different business models. The evaluation of the approach and the method indicated concrete suggestions for improvement, which have already been addressed in the results section. At present, it is not possible to make any statements about the cost–benefit ratio and the recommended frequency of application of such assessments since the method was used for the first time. More application experience is needed to draw valid conclusions.

The results show how and under what conditions the CBM can be applied by communication practitioners. Building on the growing strategy-as-practice debate in the field of communication management, our study shows that the CBM helps communication practitioners to strategize: the tool stimulates structured conversations and discursive actions around communication departments performances and will support decision-making within organizations (Aggerholm and Asmuß, 2016). On a more general level our findings underline that the usage of management tools always depends on social aspects such as the individual motivation of the team or micro-political games within the organization (Volk and Zerfass, 2020). The observation of the diffusion and usage of the CBM in the professional field will be highly interesting when taking on an interpretative and social constructivist view on management tools. The study underlines that theory building in social sciences is an iterative process that can be supported by a pragmatic and participative methodology. The pilot study thus provides initial findings and reveals patterns, but only repeated use of the tool will lead to the consolidation of a holistic picture, which must be reflected against the background of existing knowledge.

Overall, this study provides first insights into the field of business models for communications. The CBM introduces a new way of assessing communication departments in organizations and thus allows communication leaders to gain valuable insights on their work and impact. Using research-based management tools can help communication departments to get a better standing and become more professional. The CBM, specifically, supports communication leaders in shaping and visualizing the DNA of their department and position themselves as a valuable unit in the organization. It underlines that only those who use the right tools and methods will manage to win in the battle for scarce resources and attention.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data collected must be treated confidentially as it originates from a study conducted jointly with communication professionals from 53 institutes of a research organization. The datasets contain information on the internal structures and strategies of the participating institutes and cannot be shared. Requests on data availability can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. FV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CL: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. AZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The publication of this article was funded by the Open Access Publishing Fund of Leipzig University supported by the German Research Foundation within the program Open Access Publication Funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all communicators at the Fraunhofer Gesellschaft who agreed to participate in the pilot study and the evaluation study.

Conflict of interest

FV was employed by company DekaBank Deutsche Girozentrale. CL was employed by company Lautenbach Sass.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aggerholm, H. K., and Asmuß, B. (2016). A practice perspective on strategic communication: the discursive legitimization of managerial decisions. J. Commun. Manag. 20, 195–214. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-07-2015-0052

Andersson, R. (2023). Public relations strategizing: a theoretical framework for understanding the doing of strategy in public relations. J. Public Relat. Res. 36, 91–112. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2023.2259523

Balmer, J. M. T., and Greyser, S. A. (2006). Corporate marketing: integrating corporate identity, corporate branding, corporate communications, corporate image and corporate reputation. Eur. J. Mark. 40, 730–741. doi: 10.1108/03090560610669964

Bergen, N., and Labonté, R. (2020). Everything is perfect, and we have no problems. Qual. Health Res. 30, 783–792. doi: 10.1177/1049732319889354

Buhmann, A., and Volk, S. C. (2022). “Measurement and evaluation” in Research handbook of strategic communication. eds. J. Falkheimer and M. Heide (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 475–489.

Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J. Consum. Res. 20, 303–315. doi: 10.1086/209351

Frandsen, F., and Johansen, W. (2010). “Strategy, management, leadership, and public relations” in The SAGE handbook of public relations. ed. R. L. Heath. (2nd Edn.) (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 293–306.

Grunig, L. A., Grunig, J. E., and Dozier, D. M. (2002). Excellent public relations and effective organizations. NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale.

Gulbrandsen, I. T., and Just, S. N. (2016). In the wake of new media: connecting the who with the how of strategizing communication. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 10, 223–237. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2016.1150281

Gulbrandsen, I. T., and Just, S. N. (2022). “From strategy to strategizing” in Research handbook of strategic communication. eds. J. Falkheimer and M. Heide (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 99–117.

Jarzabkowski, P., and Kaplan, S. (2015). Strategy tools-in-use: a framework for understanding ‘technologies of rationality’ in practice. Strateg. Manag. J. 36, 537–558. doi: 10.1002/smj.2270

Johnson, G., Melin, L., and Whittington, R. (2003). Micro strategy and strategizing: towards an activity-based view. J. Manag. Stud. 40, 3–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.t01-2-00002

March, J. G. (2006). Rationality, foolishness, and adaptive intelligence. Strateg. Manag. J. 27, 201–214. doi: 10.1002/smj.515

Sage Publishing (2012). Are we too limited on group size? Available online at: https://www.methodspace.com/blog/are-we-too-limited-on-group-size-what-about-2-or-3-person-mini-groups (Accessed December 9, 2024)

Van Riel, C. B. M, and Fombrun, C. J. (2007). Essentials of corporate communication. New York, NY: Routledge.

Volk, S. C., and Zerfass, A. (2020). Management tools in corporate communications: a survey among practitioners and reflections about the relevance of academic knowledge for practice. J. Commun. Manag. 25, 50–67. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-02-2020-0011

Zerfass, A., and Lautenbach, C. (2022). Business-Modelle für Kommunikationsabteilungen. Grundlagen und Erfahrungen aus einem Pilotprojekt. PR Magazin 43, E1–E8.

Zerfass, A., and Link, J. (2024). Business models for communication departments: a comprehensive approach to analyze, explain and innovate communication management in organizations. J. Commun. Manag. 28, 384–403. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-02-2023-0027

Keywords: business model, communication management, communication strategy, corporate communications, public relations, value creation

Citation: Link J, Vaassen F, Lautenbach C and Zerfass A (2025) A mixed-method approach to assess business models of communication departments: insights from a pilot study. Front. Commun. 10:1547040. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1547040

Edited by:

Matthias Karmasin, CMC- Institute for Comparative Media- and Communication Studies (Austrian Academy of Sciences/University of Klagenfurt), Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Tobias Eberwein, Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW), AustriaTeresa Ruão, University of Minho, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Link, Vaassen, Lautenbach and Zerfass. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jeanne Link, amVhbm5lLmxpbmtAdW5pLWxlaXB6aWcuZGU=

Jeanne Link

Jeanne Link Fiona Vaassen

Fiona Vaassen Christoph Lautenbach

Christoph Lautenbach Ansgar Zerfass

Ansgar Zerfass