- Department of Psychology, University of Milan-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

In languages like Italian, all nouns have grammatical gender, which in most cases can be inferred from word endings. Nouns that refer to people may also convey information about the referent’s gender (i.e., semantic gender), as in the case of transparent gender-marked nouns (e.g., maestro[MASC]/maestra[FEM], ‘male/female school teacher’). Gender remains unspecified in the case of bigender nouns (e.g., cantante[MASC, FEM], ‘singer’), though these may carry gender stereotypical associations (dirigente[MASC, FEM], ‘manager’, typically associated with men). To overcome the binary gender distinction in language, one proposal for Italian gender inclusive language introduces the schwa (ə) as a neutral word-ending (e.g., maestrə). There is still no scientific evidence on the efficacy of gender-neutral forms in promoting Italian speakers’ perceptions of these role nouns as gender-neutral and of their potential to reduce grammatical and/or gender stereotypical associations. Here, we present three rating studies to investigate gender associations of role nouns presented in isolation. In Study 1 (N = 106) bigender and gender-marked role nouns with their canonical grammatical endings were tested; in Study 2 (N = 121) we tested bigender nouns and neutralized nouns ending in -ə in the written modality, while in Study 3 (N = 75) in the auditory modality. Results showed that, ə only partially reduces gender associations of neutralized role nouns. When the neutralized form of the noun evokes the masculine (e.g., direttorə, ‘director’) or when a noun carries a strong stereotypical association, as in the case of stereotypically feminine nouns like casalingə (‘homemaker’), the neutralized form seems ineffective. Furthermore, schwa in the written modality appeared more effective than the auditory modality. We discuss our findings also in light of trade-offs of this proposal from linguistic and sociolinguistic perspectives.

1 Introduction

Gender is a complex grammatical category as it conflates elements that are purely linguistic in nature as well as social and cognitive aspects of language use and processing. From a linguistic perspective, in grammatical-gender languages like Italian and French, gender is a morphosyntactic feature that classifies nouns as masculine or feminine within a binary grammatical gender system (Corbett, 1991). In Italian, nouns referring to people can be gender transparent, namely, they can express a consistent mapping between their linguistic form and their referent’s gender (maestro[MASC], ‘male teacher’; maestra[FEM], ‘female teacher’) based on an attested regularity between a word ending and its grammatical gender (Padovani and Cacciari, 2003). Other nouns can be gender opaque, namely their ending is not informative with respect to their referent’s gender since they can both refer to a female and a male referent (cantante[MASC, FEM], ‘male/female singer’). Previous psycholinguistic research in gender-marked languages has shown that grammatical gender is mastered early in language acquisition (Mornati et al., 2023) and is immediately integrated during language processing to establish coordinated agreement across different elements in the sentence (Bambini and Canal, 2021). Indeed, gender traits are activated during sentence processing to ensure agreement at various levels, such as within noun phrases (e.g., article-noun or adjective-noun agreement) and across verb-subject pairs (Chomsky, 1995; Levelt et al., 1999). When a word is processed, gender information, if grammatically relevant, is activated immediately at the morphosyntactic level during the representation of the lemma in the mental lexicon (Schriefers et al., 1999). At the syntactic level, grammatical gender is then used for establishing agreement relations during sentence processing. In the case of agreement mismatches, several psycholinguistics studies show early effects of disruption during incremental processing in gendered languages (Molinaro et al., 2011), indicating that gender information is used in the first stages of parsing. Moreover, late measures of processing suggest that reanalysis is costlier after grammatical gender mismatches than number mismatches (Horacio and Carreiras, 2005). The different behaviors observed in the case of mismatch in gender or number features provide a key to understanding the interplay of lexical and conceptual features during sentence processing.

Nouns that refer to people might also be distinguished on the basis of semantic gender, that is the conceptual representation of the noun as referring to a man or a woman. Being morphosyntactic and semantic layers distinct, there is no necessary and straightforward relation between the morphological form of a noun referring to human referents and their gender (Corbett, 2012). Previous experimental studies on gendered languages have shown that morphosyntactic gender on nouns is a reliable cue for resolving agreement dependencies in sentences and may override semantic gender agreement. For example, a study by Cacciari et al. (1997) showed that grammatical gender in epicene words in Italian (like la vittima, ‘the victim’, which is grammatically feminine but can refer to male or female individuals) took precedence over the semantic agreement in anaphoric dependencies: slower reading times of the masculine pronoun lui (‘he’, compared to lei, ‘she’) were recorded following a grammatically feminine epicene noun, despite the fact that, semantically, this noun can refer to a man. Languages that do not exhibit explicit grammatical gender traits on nouns present a complex picture regarding gender processing as well. In these cases, gender processing can occur at the semantic or pragmatic level, even in the absence of linguistic gender cues. For instance, in an ERP study conducted on English, Canal et al. (2015) showed that mismatches between the expectations about the referent’s gender (i.e., gender stereotypes) and the linguistic input (e.g., references to counter-stereotypical characters like female engineers) require additional cognitive effort, observable through neural responses like the P600 or N400 effects. These results highlight that the initial representation of the referent’s gender reflects both the information conveyed by the noun’s grammatical gender and the gender typically associated with the referent’s role. The effects of gender stereotypical associations on the processing of role nouns have been investigated in different languages, with evidence pointing to the automatic activation of stereotypes in both word and sentence reading (Banaji and Hardin, 1996; Cacciari and Padovani, 2007; Casado et al., 2023; Osterhout et al., 1997; Pesciarelli et al., 2019; Siyanova-Chanturia et al., 2015). In Italian, gender stereotypes can surface on opaque role nouns particularly (Cacciari and Padovani, 2007). For instance, the gender opaque nouns badante (‘caregiver for the elderly’) and falegname (‘carpenter’) can be both used to refer to male and to female referents, but the former is generally associated with female referents, while the latter is typically associated with male referents. On the other hand, some nouns, such as cantante (‘singer’), are not generally associated with any specific gender. Furthermore, most bigender nouns end in -a; despite their ending, which is the typical grammatically feminine word-ending, some bigender nouns could show stereotypical associations with male referents (e.g., camionista, ‘truck driver’).

Recently, research on gender has focused on forms described as ‘inclusive’, i.e., intended to overcome gender binarism in language. The so-called Gender Inclusive Language (GIL) has been promoted over the years in several countries by activists and social movements, like some feminist circles and LGBTQIA+ communities. A public debate on GIL has emerged, and different linguistic strategies have been proposed, depending on how each language conveys gender. In natural-gender languages, like English or Swedish, which mainly express gender through agreement on personal pronouns, there has been an emphasis on using pronouns that may refer to a person of any gender (e.g., English singular they), including pronouns that have been actively created for the purpose of language inclusivity, such as English ze and Swedish hen (e.g., Arnold et al., 2021; Lindqvist et al., 2019; Sanford and Filik, 2007; Vergoossen et al., 2020). In gendered languages, such as Italian, French, and German, role nouns can express a relation between their form (i.e., their word ending) and their referent’s gender. As discussed above, the Italian words maestro and maestra refer to a male and female teacher, respectively, by virtue of their endings (-o, -a), which mark masculine and feminine gender. Similarly for the pair Lehrer and Lehrerin in German. In such languages, gender-inclusive forms have been proposed as alternatives to generic masculine role nouns and double forms (see Körner et al., 2022 for review). In German, for example, building on the fact that the feminine plural ending is often -innen, the female form is used, but the lowercase i is replaced by a capital I (e.g., LehrerInnen instead of Lehrer[MASC] and Lehrerinnen[FEM]) or it is preceded by a star symbol (e.g., Lehrer*innen). In French, the most common form of GIL uses a median point inserted after the word stem, followed by the feminine ending -n and, for plurals, by an additional median point and -s (e.g., citizens is spelled citoyen・ne・s, instead of citoyens[MASC] and citoyennes[FEM]; Burnett and Pozniak, 2021).

Since in Italian morphological endings generally provide reliable gender cues, one of the proposals of GIL recommends substituting the word ending of nouns referring to people with the schwa (‘ǝ’) symbol (e.g., avvocatǝ, ‘lawyer’, instead of the masculine and feminine forms avvocato and avvocata; Gheno, 2021).1 Although other interventions have been proposed for Italian (such as using the asterisk ‘*’ as a neuter ending of words, which is widespread in written communications in substitution of generic masculine forms, e.g., car* tutt* instead of cari tutti, ‘dear all’),2 one of the merits of the schwa proposal is its applicability to spoken language as well. This proposal has gained increasing attention in Italy in the last few years, with several attempts to advocate for or against it, with great media coverage in newspapers and social media. Linguists and experts of language, including representatives of the Accademia della Crusca (which is a recognized national institution for matters related to the Italian language), intervened more than once in the debate on the introduction of GIL forms, with official communications against their introduction. Several opinion contributions have also been published by linguists and opinion makers to express concerns on the feasibility and necessity of this proposal (e.g., Giusti, 2022; Arcangeli, 2022; De Benedetti, 2022; Robustelli, 2021).3 The main argument of the opponents is not focused on preserving the language from novelty or change, which is a natural part of any language’s evolution. Instead, they emphasize economic principles, such as the need to strengthen existing linguistic tools that promote inclusive language. For instance, they advocate using masculine generic forms or gender-neutral terms when referring to mixed groups of people.4 Most importantly, they argue that introducing a non-standard grapheme and phoneme would unnecessarily complicate the morphological, phonological, and orthographic structure of the language. In this respect, it is important to note that Italian has a rich agreement system in which a change in the gender of the nouns does not remain at the level of the lexicon, but it spreads potentially over all the elements in the sentence (articles, adjectives, and verbs), via gender agreement. This, in turn, might heavily impact the readability of texts, with potential increased difficulties for people with reading impairments or more fragile populations, such as the elderly.

Similar concerns about the introduction of GIL forms have been raised in other European countries by equivalent recognized institutions, such as the Academiè Francaise in France, with political consequences as well (such as the ban of the ‘écriture inclusive’ in schools by France’s education minister at the time, in July 2021). More on the sociolinguistic side, the interplay between linguistic change, linguistic prescriptivism, and ideology is a long-debated and important topic (cf. Silverstein, 1985; cf. also Burnett and Bonami, 2019 for a recent analysis focused on France).

In the last decade, several studies have been carried out with speakers of different languages to investigate the efficacy of neutralized forms, providing mixed results. Körner et al. (2022), for example, presented German participants with the first part of a sentence containing a role noun, either in the generic masculine, i.e., masculine form with an underspecified meaning, or in the neutralized star form, and asked them to rate the acceptability of a continuation sentence that disambiguated the gender of the role noun. Sentences following generic masculine forms were more often and more quickly judged to be compatible with male referents compared to female referents, whereas the opposite was true for neutralized forms, which seemed to carry a feminine bias. Using a similar paradigm with French speakers, Tibblin et al. (2023) similarly found that contracted double forms with a similar surface form to feminine nouns, such as les voisin·es[MASC,FEM] (‘the neighbors’) carried a feminine bias. However, the opposite was true for forms such as le voisinage (‘the neighborhood’), although in both cases the bias was smaller than the one observed for generic masculine forms. In Zacharski and Ferstl (2023), German speakers judged whether pictures with male, female, or non-binary connotations were appropriate representations of role nouns presented in the masculine, feminine, or neutralized form. In this case, participants quickly accepted pictures of all genders in association with the neutralized form, suggesting that the intervention worked as intended.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated the efficacy of schwa in neutralizing the referent’s gender information conveyed by the grammatical gender on Italian role nouns. Italian provides an interesting testing ground to assess the effects of GIL interventions. First, Italian is characterized by an overall transparent orthography (including regular and transparent gender associations) and a rich morphosyntactic agreement system, as discussed above. Thus, any change introduced at the phono-orthographic level impacts higher levels of linguistic processing. This does not happen in natural-gender languages, like English, in which the only proposed change pertains to the use of the plural pronoun (they) as singular to refer to non-binary individuals or to be used in cases in which neutral (ungendered) forms of pronouns are warranted. Second, schwa replaces standard suffixes with a non-letter symbol in writing (and a non-standard linguistic phoneme in the oral modality) with a specific linguistic function whose effects need to be empirically assessed. This proposal differs from GIL proposals in other gender-marked languages like French or German, in which a non-letter symbol is used to emphasize the juxtaposition of feminine and masculine linguistic forms, which nevertheless remain in their canonical form.

Beyond these general concerns, there are at least two other potential issues to face with respect to the introduction of ǝ. First, its visual similarity with the feminine ending -a (or the feminine plural -e). In the written modality, this may induce a female bias, namely, the preferred activation of a female representation when referents of any gender are grammatically acceptable, exacerbating a phenomenon already observed in other studies on GIL (e.g., Körner et al., 2022; Tibblin et al., 2023). Second, the schwa phoneme does not belong to the standard Italian phonemic inventory except in specific southern dialects (Bertinetto and Loporcaro, 2005). Its introduction might thus potentially have two side effects that need to be assessed experimentally. On the one hand, speakers of standard Italian may not perceive this sound as being significantly different from other Italian vowels and, consequently, assimilate it to one or more native vowels, as often happens in second language acquisition (PAM-L2 model, Best and Tyler, 2007). On the other hand, even when the schwa phoneme is correctly identified, the neutralized words might be associated with grammatical forms already present in regional dialects, such as Napoletano (spoken in Naples and the surrounding area in the Campania region) and Barese (spoken in Bari and the surrounding area in the Apulia region), which feature vowel reduction to [ə] (Repetti, 2000). As a consequence, the speakers of dialects that include [ə] in their vowel systems may recognize it but fail to associate it with gender neutrality, showing a male bias instead. Due to a common (passive) knowledge of the dialectal repertoire across Italy, this association could also occur among speakers of other dialects, leading to unpredictable effects on people’s interpretation. Given that one of the advantages of the schwa is the fact that it is also “pronounceable,” and that its use has recently started to extend to oral communication, it is important to investigate if the schwa sound is actually recognized as a distinct phoneme by speakers of standard Italian and if it is perceived as gender-neutral.

This article presents the findings of three studies investigating gender associations of Italian role nouns presented in different forms: gendered, bigender, or neutralized. The results of the three studies are then compared to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of the schwa in neutralizing gender on nouns.

2 The research

In three independent studies, we investigated the gender of the referent associated with role nouns and the efficacy of the symbol ə in neutralizing the noun’s gender association. Given the novelty of this GIL proposal, our research aims at setting a first baseline to assess the efficacy of this intervention in basic, low-level terms: is a noun ending in schwa perceived as ‘neutral’ with respect to gender? Albeit limited in its scope, we believe that such preliminary assessment is necessary to progress in the debate about the feasibility or opportunity of such intervention.

By adopting a modified version of the task used by Misersky et al. (2014), participants were shown role nouns and asked to judge how much each role noun was more likely to refer to a man or a woman using a visual analog scale. No numerical intervals appeared on the scale; only the endpoints were labeled as Man on the left and Woman on the right ends of the scale. In all studies, the stimuli were in Italian, and the participants were native Italian speakers. The studies were administered online via a laptop or personal computer. Studies 1 and 2 were conducted using the Qualtrics web system, while Study 3 was administered through the Labvanced testing platform.

The methodological procedure was the same across studies: after reading the study information and providing consent to participate, participants filled in some demographic information (such as their self-reported gender and age) and received task instructions.

They were then presented with a list of role nouns (one at a time) in their singular form and with no preceding article, either in written form (Studies 1 and 2) or audio format (Study 3). Each stimulus was evaluated by participants on the visual analog scale. At the beginning of each trial, the slider handle appeared in the middle of the scale, and participants had to click on the slider to provide their rating and proceed to the next trial. The question “How likely is it that this noun refers to a man vs. a woman?” appeared immediately above each role noun, as shown in Figure 1.

Before conducting the studies, the research protocol was evaluated and approved by the local commission of the Psychology Department for minimal risk studies.

Study 1 served as the baseline: it included both gender-marked nouns either in their masculine or feminine grammatical endings (maestro[MASC]/maestra[FEM], ‘school teacher’), which convey explicit information about the gender of the referent, and common gender nouns, namely, bigender nouns that do not change their ending depending on their referent’s gender and can both indicate a female and a male referent (cantante[MASC, FEM], ‘singer’). This setup was designed to explore gender associations of role nouns by disentangling (i) the role of grammatical gender, specifically conveyed by gender suffixes on gender-marked role nouns, and (ii) the gender stereotypical associations that might affect the perceived gender category (man or woman) associated with bigender role nouns, in which the form of the noun per se does not convey any information about the referent’s gender. We expect that participants will rely on the grammatical gender cues available on gender-marked role nouns, thus using the left end of the scale (man) for nouns in the masculine form, and the right end of the scale (woman) for nouns in the feminine form, respectively. In the absence of linguistic gender cues, as in bigender nouns, we expect participants to rely on possible stereotypical associations, similarly to what has been observed in languages like English.

Study 2 we used the same bigender role nouns as In Study 1. However, for the gender-marked nouns, the symbol ə replaced the final vowel (i.e., it was used as a suffix), hypothetically neutralizing the gender information conveyed by the form of such nouns. Besides removing gender information conveyed by grammatical form, ə could also act as an explicit neutrality marker thus also reducing stereotypical associations. The rationale behind this manipulation was to understand the gender associations between a role noun and its referent by comparing the canonical forms of the noun used in Study 1 (i.e., masculine and feminine nouns ending in -o and -a, respectively) to the neutralized forms in Study 2 (i.e., the form ending in -ə). To be effective as a form of GIL, the nouns ending in -ə should be judged as neutral on the gender scale, with ratings around the middle point, compared to grammatically gender-marked nouns, which, by contrast, are expected to be polarized toward one of the opposite ends of the scale.

Study 3’s stimuli consisted of a subset of bigender role nouns from Studies 1 and 2, as well as gender-marked nouns with neutralized endings (i.e., ə as in Study 2), but presented in an auditory format. The purpose of Study 3 was to examine whether participants could perceive the schwa sound as genuinely gender-neutral. If this is the case, then people should associate the nouns ending in schwa with gender neutrality, similarly to what is expected for its written counterpart. As said above, since the schwa phoneme does not exist in the Italian phonemic inventory except in some southern Italian dialects, it’s important to assess its efficacy in being perceived as gender-neutral, irrespective of inter-speaker variability.

2.1 Data treatment

For each noun in each study, we computed descriptive statistics (cf. Supplementary Table 1) obtained from the participants’ ratings on the visual analog scale recorded as numerical values ranging from 05 (i.e., Man) to 100 (i.e., Woman). For the purposes of the statistical analyses, a centered score was first calculated for each noun: we subtracted the value 50 (considered the neutral zero) from each role noun and then divided the score obtained by 100. This yields values ranging from −0.5, which indicates a fully male association, to +0.5, which indicates a fully female association. This provides a measure of the male vs. female association of each noun compared to the 0 (neutral) value. We then standardized these scores on a 0 to 1 continuum, in order to get the absolute distance from the neutral point. This second coding schema was used to assess the strength of the deviation from a neutral expectation was, irrespective of polarity. Taken together, these values can be used to test whether each noun is associated with a male vs. female representation (on the basis of their polarity), and the strength of this association (on the basis of their absolute distance from zero). All analyses were conducted in the R environment.

For each study, we built two models, each using one of the described scores as the dependent variable. Independent variables included the noun’s gender, participants’ self-reported gender, and age, along with two-way interactions: noun gender × self-reported gender and noun gender × age. All models incorporated random intercepts and slopes for participants and items (full model outputs are available in the OSF repository). The rationale for including gender and age of participants in these models is based on previous results suggesting that these factors might modulate stereotypical expectations (Siyanova-Chanturia et al., 2015) and can influence language processing and judgment tasks (e.g., Canal et al., 2015; Garnham et al., 2015). Additionally, age might be particularly relevant for Studies 2 and 3 with neutralized nouns, potentially reflecting generational differences in attitudes, language use, and language processing.

3 Study 1

3.1 Participants and stimuli

One hundred and six participants (N = 106; 81 females; mean age 26.6, SD = 10.9; age range 18–62) completed the study. They were recruited via social media and volunteered to participate in the study.

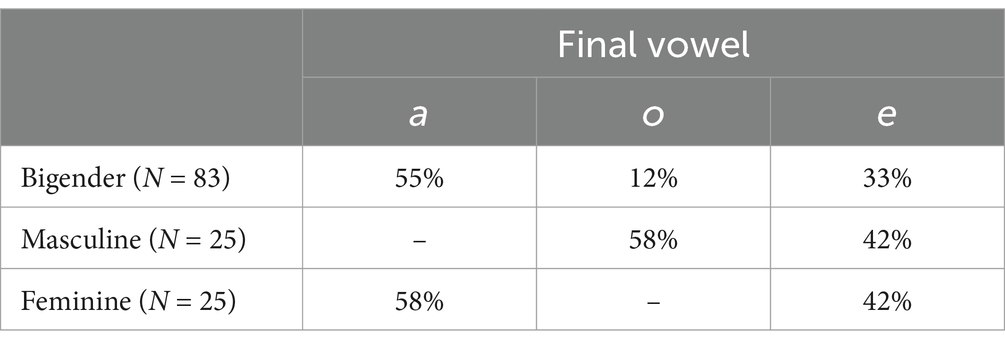

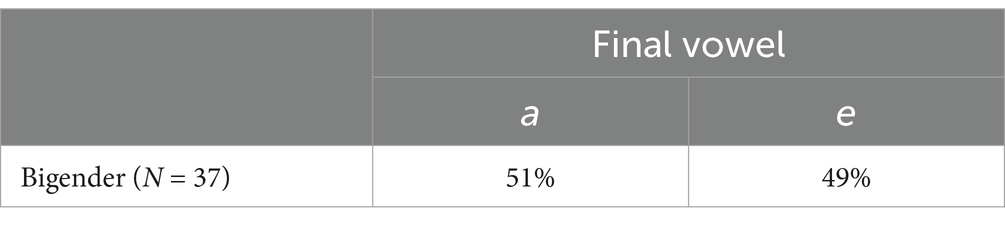

As for the stimuli, we individuated 1306 Italian role nouns: 80 were bigender, and 50 were gender-marked. Gender-marked role nouns appeared in both their masculine and feminine forms (maestro[MASC], maestra[FEM] ‘teacher’). Bigender role nouns appeared in their canonical singular form (falegname[MASC, FEM] ‘carpenter’). The majority of bigender role nouns ended with the vowels -a and -e; gender-marked role nouns in their feminine form ended either with -a or -e; gender-marked role nouns in their masculine form ended with -o or -e (Table 1).

3.2 Results

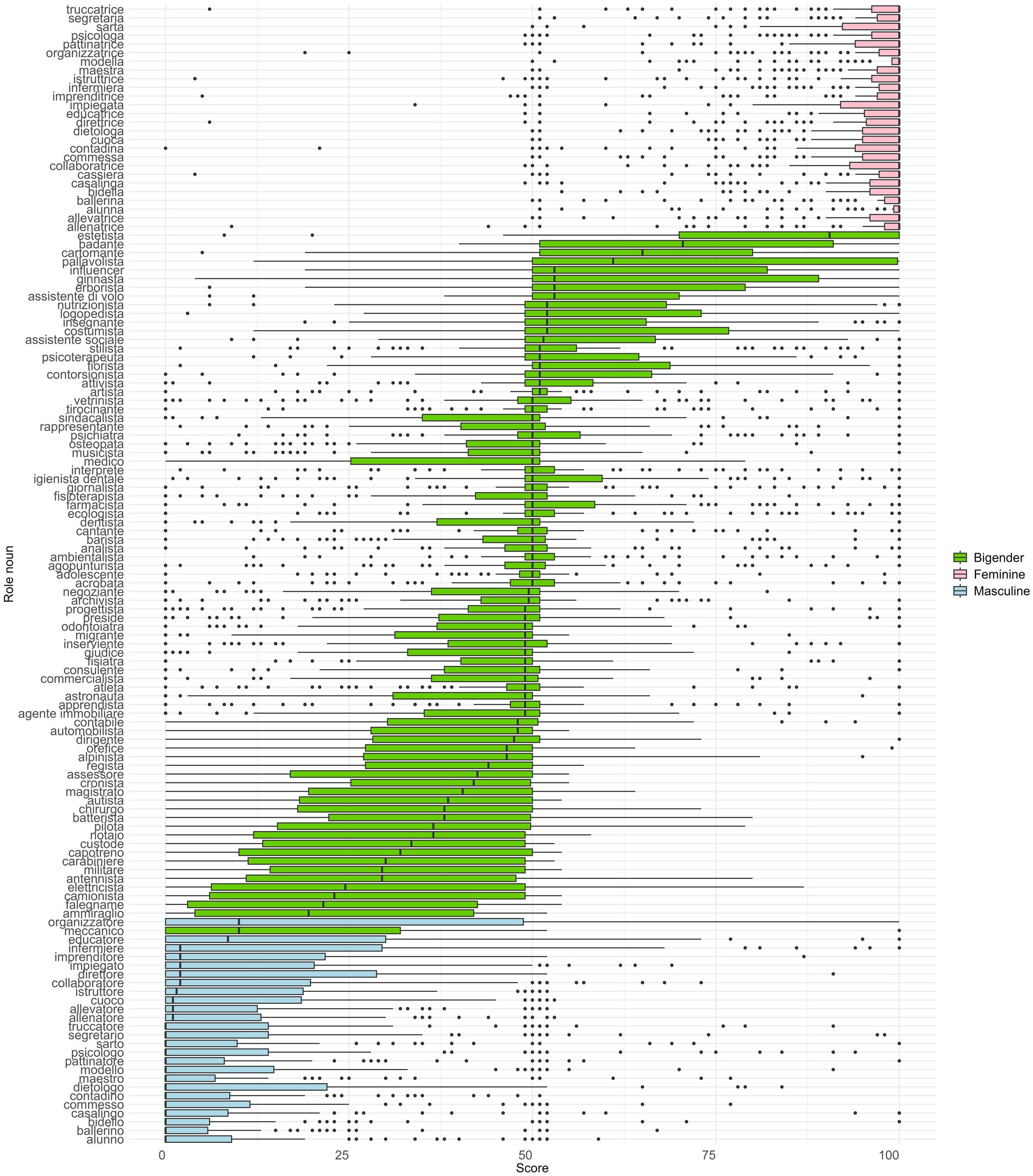

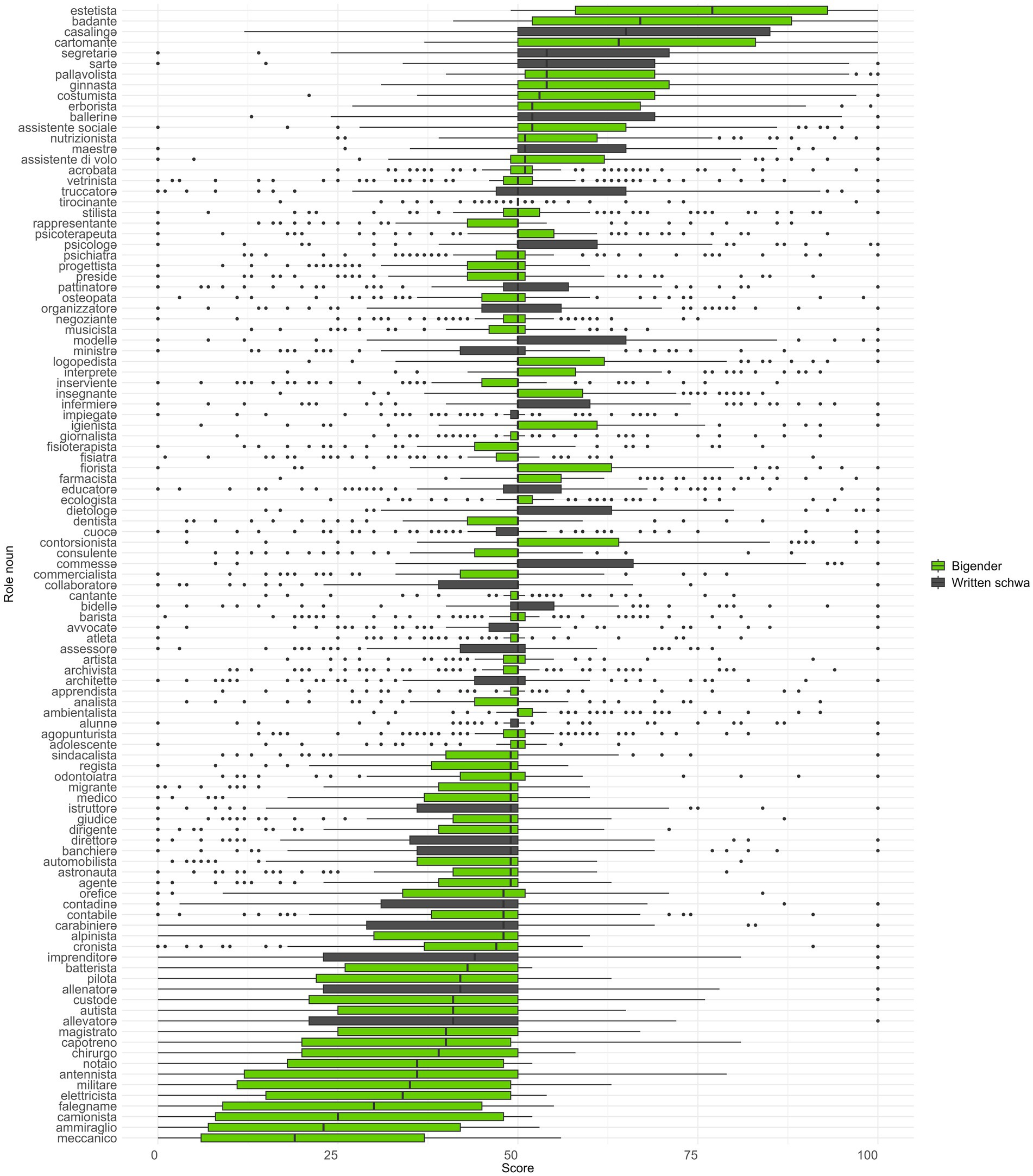

The dataset consisted of 13,780 observations. Overall, mean ratings for each word ranged between 6.48 and 96.68 (M = 48.57; SD = 32.84). As expected, masculine gender-marked nouns received the lowest rating, ranging from 6.48 to 23.98 (M = 11.48; SD = 4.07), and feminine-marked role nouns received the highest ratings, ranging from 92.86 to 96.69 (M = 94.85; SD = 0.86). More variability was instead observed in bigender nouns, which received ratings ranging from 18.70 to 81.94 (M = 45.61; SD = 12.42). It is worth noting that the average ratings given to masculine nouns have a wider distribution as compared to feminine nouns: masculine nouns reach up to a quarter of the scale, while feminine nouns are highly polarized toward the extreme end of the scale. The ratings distribution is plotted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Ratings distributions associated with role nouns in Study 1, ordered by median value. The vertical ticks in each boxplot represent the median rating. The noun’s gender (masculine, feminine, bigender) is color-coded.

To test whether the ratings provided by the participants depended on the lexical form of the noun, we computed a centered score as detailed in Section 2.1 and computed the means of the centered score in relation to the noun’s gender. Masculine nouns showed a mean of −0.38, feminine nouns of +0.44, and bigender nouns obtained a mean value of −0.05.

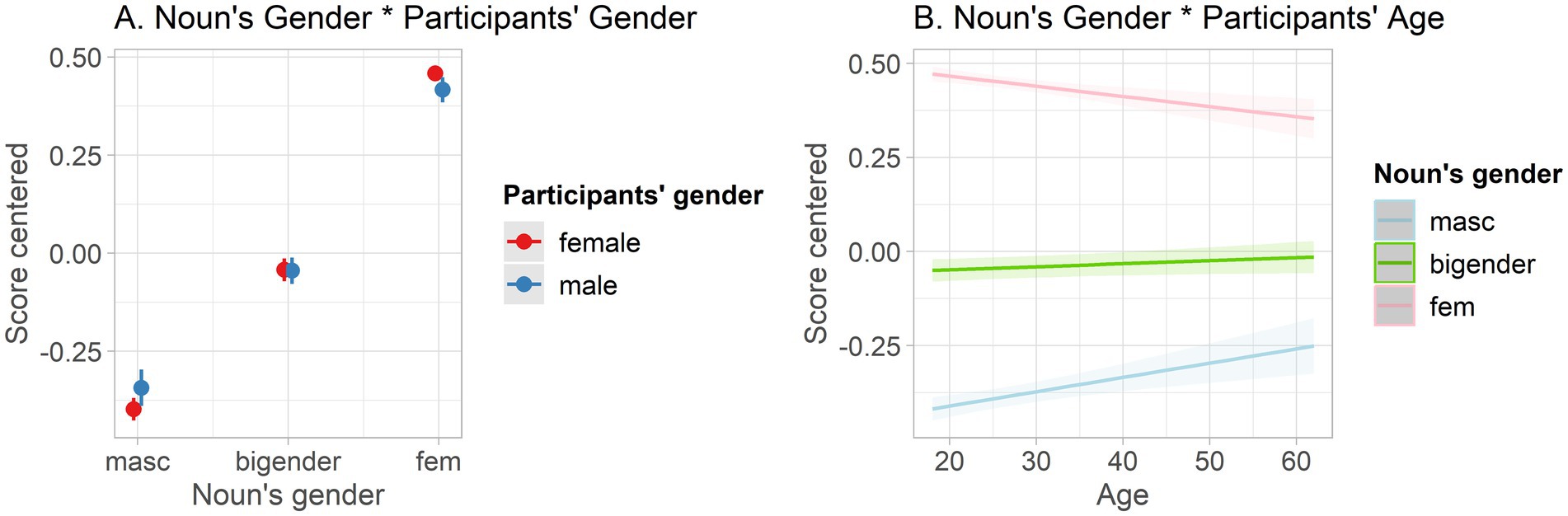

In the analyses, masculine was set as the reference level for the variable Noun’s Gender. Results of the linear mixed-effects model with the centered score as the dependent variable revealed that ratings for masculine nouns differed significantly from those for bigender (t = 11.71, p < 0.001) and feminine nouns (t = 20.80, p < 0.001). The interaction between noun’s gender and participants’ gender was significant for gender-marked nouns (t = −2.26, p = 0.025): female participants rated masculine nouns closer to the masculine extreme and feminine nouns closer to the feminine extreme compared to male participants. Participants’ gender did not significantly modulate ratings of bigender nouns compared to masculine nouns (t = −1.94, p = 0.054, Figure 3A). Additionally, the Noun’s Gender × Participants’ Age interaction showed a difference between masculine and bigender nouns (t = −2.62, p = 0.010) and between masculine and feminine nouns (t = −3.92, p < 0.001, Figure 3B): older participants rated masculine nouns closer to bigender compared to feminine nouns.

Figure 3. Effect plots of the interaction between Noun’s Gender * Participants’ Gender (A) and of the interaction between Noun’s Gender * Participants’ Age (B) from the analysis on the centered score.

We then calculated the absolute distance from zero for the ratings and found the following mean values: 0.40 for masculine nouns, 0.45 for feminine nouns, and 0.14 for bigender nouns. To test the differences across the noun categories, we ran a linear mixed-effects model as described in Section 2.1. Results showed that masculine nouns’ absolute ratings were significantly different from bigender nouns (t = −7.57, p < 0.001), but not from feminine nouns (t = 0.71 p = 0.482). The Noun’s Gender × Participants’ Gender interaction mirrored what was found with centered scores for gender-marked nouns (t = 2.17, p = 0.033) and bigender nouns (t = 1.20, p = 0.234). Age, as captured by the Noun’s gender × Participants’ Age interaction, did not significantly modulate participants’ ratings when contrasting bigender and masculine nouns (t = 1.25, p = 0.216). As for gender-marked nouns, their ratings, particularly on the masculine form, became closer to neutrality as the age of the participants increased (t = 2.72, p = 0.008).

3.3 Discussion

In the present study, we tested gender associations of Italian role nouns that were either gender-marked, namely informative with respect to the gender of their referents, or bigender, namely ambiguous with respect to their referents’ gender. Specifically, this first study aimed at testing the effect of grammatical gender conveyed by gender suffixes on gender-marked role nouns and the effect of gender stereotypical associations on bigender role nouns.

The ratings were distributed across the scale according to the grammatical gender of the nouns: masculine nouns received the lowest ratings, most bigender nouns’ ratings were toward the middle part of the scale, and feminine nouns received the highest ratings. Bigender nouns were the closest to the neutral zero, followed by masculine nouns and, ultimately, by feminine nouns, which were the most distant. Also, gender stereotypical associations emerged in the case of bigender role nouns as suggested by the wide distribution of the average ratings: while participants rely on the grammatical gender cues available on gender-marked (feminine, masculine) role nouns, they might rely on stereotypical associations in the absence of linguistic gender cues.

As for gender-marked nouns, our findings suggest that feminine nouns are more strongly associated with female referents than masculine nouns are with male referents. This aspect emerges primarily from the significant difference between masculine and feminine nouns in interaction with gender and age. In particular, with respect to age, the older the participants were, the greater the gap between the absolute values assigned to masculine and feminine nouns, with the former getting closer to the neutral zero compared to the latter. One possible interpretation is that masculine role nouns may be perceived as under-specified in terms of gender, aligning with the notion of a generic masculine use (cf. Cacciari and Padovani, 2007), which seems to be particularly evident in the older generations, compared to the younger ones. It is particularly notable that the same role nouns were used in both their masculine and feminine forms in this study, yet the feminine forms were rated as further from neutrality by the older participants. This effect is notable given the task design, which did not explicitly encourage a generic masculine interpretation. Specifically: (a) singular forms were used, (b) both feminine and masculine forms were presented to the same participants, and (c) the task explicitly required participants to associate the noun form with the gender of a potential referent. Additionally, an interaction effect emerged involving participants’ gender. Female participants provided more extreme ratings for both masculine and feminine nouns compared to male participants.

As for bigender nouns, participants’ ratings varied quite a lot on the scale, depending on the noun. Some nouns were perceived as truly neutral (such as artista (‘artist’), cantante (‘singer’), and giornalista (‘journalist’), among others), receiving ratings hovering around 50. Other bigender nouns, instead, presented a distribution that showed some gender stereotypical associations. For example, the nouns falegname (‘carpenter’) and camionista (‘truck driver’) received lower ratings than the masculine-marked noun organizzatore di eventi (‘event planner’), showing a stronger association with a male referent than a grammatically masculine noun. Similarly, the bigender nouns estetista (‘beautician’) and badante (‘caregiver for the elderly’) received ratings around 75, indicating a clear stereotypical association with female referents. These results suggest that, although bigender nouns are unmarked with respect to gender, some of these nouns are strongly associated with male or female representations, likely reflecting existing gender stereotypes.

4 Study 2

4.1 Participants and stimuli

Participants (N = 121; 67 females, 2 non-binary; mean age 31.8, SD = 10.8; age range 20–65) were recruited on the Prolific website7 and received monetary reimbursement for their participation according to the Prolific guidelines (i.e., 9 euros per hour).

We employed the same 80 bigender nouns included in the previous experiment, which remained in their canonical form, being amenable to being associated with either male or female referents. On the contrary, the 50 gender-marked nouns were made neutral by substituting the final vowel with the ə symbol. For instance, the nouns impiegato[MASC] and impiegata[FEM] (‘employee’) were made neutral by substituting the suffixes -o and -a with -ə, obtaining the gender-neutral form impiegatə[NEUT]. This operation collapsed the 50 gender-marked nouns into 25 gender-neutral items. Three additional nouns (avvocatə, ministrə, and ingegnerə, cf. footnote 2) have been included in the present study in their neutralized form. Hence, a total of 108 nouns denoting professional roles were considered in the study. With respect to the role nouns ending with the agentive suffix -tore in the masculine and -trice in the feminine forms, such as allenatore[MASC] and allenatrice[FEM] (‘trainer’), we adhered to the standards identified by Gheno (2021), namely we added the ə at the end of the masculine form, maintaining part of the masculine suffix (-or), obtaining the neutral form allenatorə.

4.2 Results

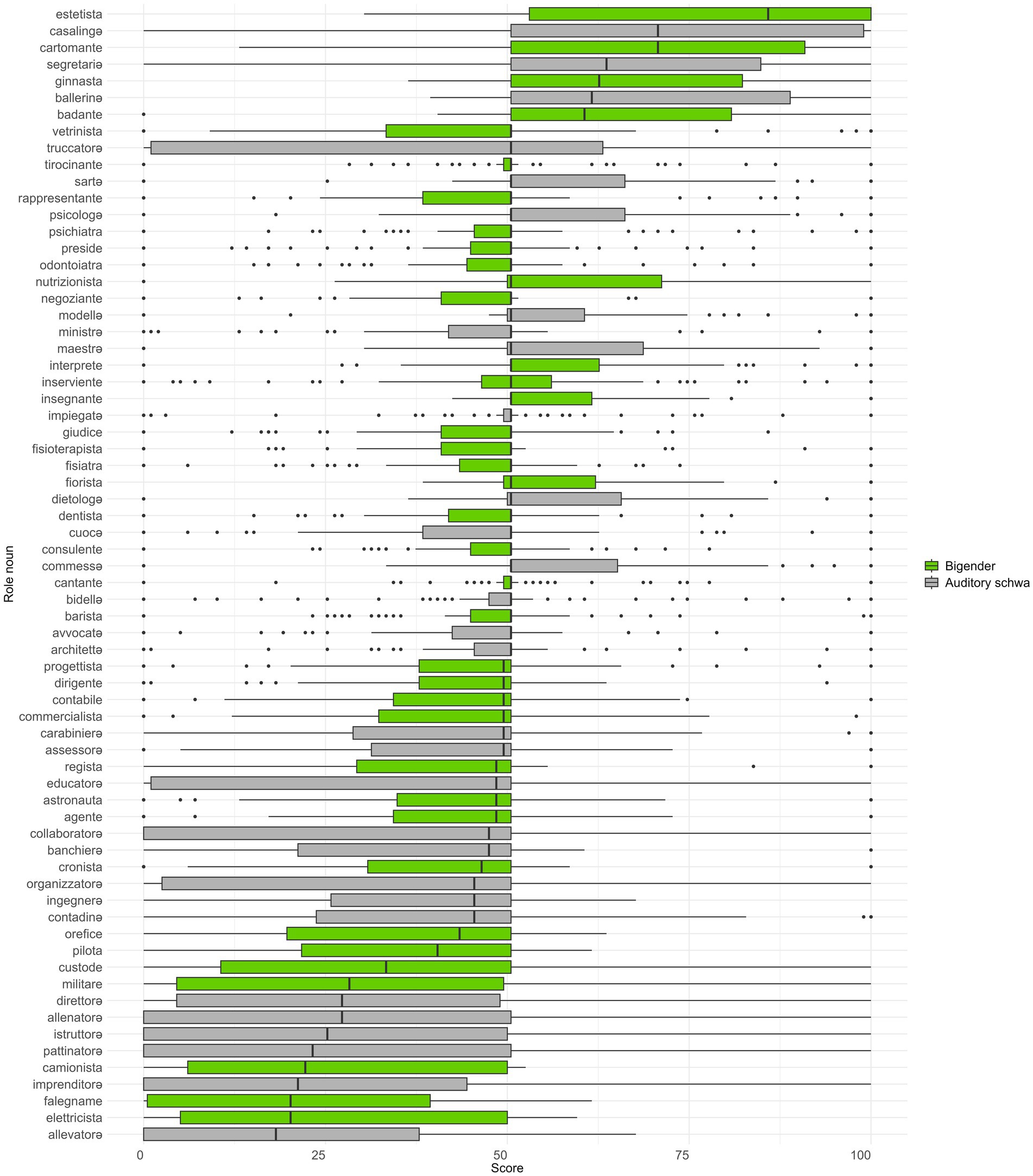

The dataset consisted of 13,068 observations. All the participants completed the experiment. As in the previous study, we computed the descriptive statistics associated with each noun (cf. Supplementary Table 1). Overall, the ratings ranged from 21.60 to 75.93 (M = 47.34; SD = 9.73). We then inspected ratings distribution across the two noun types: bigender nouns and neutralized nouns (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Ratings distributions associated with role nouns in Study 2, ordered by median value. The vertical markers in each boxplot represent the median rating. Noun’s class (schwa or bigender) is color-coded.

The ratings on bigender nouns ranged from 21.60 to 75.93 (M = 46.29, SD = 10.32), while the ratings on neutralized nouns ranged from 36.20 to 67.60 (M = 49.84; SD = 7.81). The neutralized nouns ending with the agentive suffix -torə received the lowest ratings, that is, they were the most masculine-perceived neutral nouns. The neutralized nouns casalingə (‘housekeeper’) and segretariə (‘secretary’) received the highest mean ratings (67.60 and 59.55, respectively). As in Study 1, the bigender nouns receiving the highest ratings were estetista (‘beautician’) and badante (‘caregiver for the elderly’), confirming their stereotypical association with female referents; and the bigender nouns camionista (‘truck driver’) and falegname (‘carpenter’) received ratings that were around 25, confirming the stereotypical association with male referents.

In analogy to Study 1, we tested whether there was a difference between the ratings depending on the nouns’ lexical form (bigender vs. neutralized). To do so, we computed a centered score as detailed above and computed the means of the centered score in relation to the noun’s form. Bigender nouns received a mean centered score of −0.037, while neutralized nouns received a mean score of −0.001. The results of the linear mixed effect model on the centered score showed no reliable difference (t = 1.75, p = 0.081) between the noun’s lexical forms, nor a significant interaction with participants’ age or gender. We then computed the absolute distance to the neutral zero as in Study 1 and computed the mean values associated with neutralized (0.12) and bigender (0.10) nouns. The analysis on absolute scores, showed a main effect of noun’s form, indicating that bigender nouns were overall perceived as more neutral than neutralized nouns (t = −2.52, p = 0.013). A significant Noun’s Gender × Participants’ Age interaction also emerged (t = 3.09, p = 0.002): as participants’ age increased, ratings for neutralized nouns became more distant from the neutral zero, while ratings for bigender nouns moved closer to the neutral zero. No significant interaction was observed between participants’ gender and noun’s form.

4.3 Discussion

In Study 2, we tested gender associations of 108 role nouns on a 0–100 scale: 80 were grammatically bigender, namely, they can refer to both masculine and feminine referents, and 28 were neutralized nouns containing the schwa symbol as a suffix. The proposal of the schwa symbol aimed at removing any gender information from the lexical form of the noun in order to include referents of any gender. The objective of this study was to test gender associations of neutralized role nouns and compare them with gender associations of bigender nouns. The prediction was to observe ratings around the midpoint of the scale for both neutralized and bigender nouns. Overall, the ratings showed a wide distribution, with ratings from 20 to 75, despite the fact that, in this study, no noun was gender-marked with respect to its morphological form. Bigender nouns received ratings consistent with those found in Study 1 (cf. also Section 6). As for the ratings of neutralized nouns, their distribution proved to be more varied than expected, moving away from the center of the scale, especially for those nouns that are generally considered stereotypically male or female professions. The neutralized nouns that were perceived as more ‘masculine’ were those ending with the agentive suffix -torə which strictly evokes a masculine trait, conveyed by the suffix, which is superficially different from its feminine typical counterpart, ending in -trice (the meaning of such suffix is similar to the agentive marker -er in English, as in teach-er). Therefore, their ratings might be attributed to their surface form. On the other hand, the neutralized nouns casalingə (‘housekeeper’) and segretariə (‘secretary’) received ratings that were close to the right end of the scale, indicating a stereotypical association with feminine referents, despite their neutralized form. However, considering that the distribution of the ratings observed in Study 1 on non-neutralized nouns ranged from 6 to 96, the adoption of the schwa as a gender-neutral word ending seems to be somehow effective in reducing gender associations, at least for some role nouns. The comparison between neutralized and bigender nouns revealed that bigender nouns were overall perceived as more neutral than neutralized nouns, but the ratings were modulated by participants’ age.

On the one hand, our results suggest that some efficacy of adopting the schwa as a neutral gender suffix in the written form, as it makes such nouns perceived as gender-neutral. However, its efficacy seems to be modulated by the participants’ age, and only emerges in younger participants. On the other hand, schwa seems ineffective for the cases in which the form of the neutralized noun evokes the masculine or when there the canonical form of the noun carries a strong stereotypical association.

5 Study 3

5.1 Participants and stimuli

Seventy-five participants (45 female, 4 non-binary; mean age 29.05; SD = 13.37; age range 18–71) were recruited through the Sona online experiment management system and through snowball sampling. Given the role that the participants’ Italian dialect may play in this study, we also asked for their geographical origin. Most participants (N = 66) reported spending their first years of life in northern Italy (62 in Lombardy, 3 in Emilia Romagna, 1 in Veneto); the remaining 9 were from southern Italy (6 from Campania and 2 from Apulia, two southern regions in which schwa is part of the regional dialects; 1 from Sicily).

As for the stimuli, 68 role nouns were selected among the stimuli presented in their written form in Studies 1 and 2. The stimuli set was smaller than in the previous studies, because bigender (N = 38) and neutralized (N = 30) nouns were matched based on the ratings obtained in the previous studies, in an attempt to have two balanced subsets of stimuli in terms of phonological endings (Table 2). In line with the written norming and the recommendations of Gheno (2021), the neutralization of gendered nouns consisted in substituting the word-final vowel sound with [ə] (e.g., /contadinə/ ‘farmer’). As in Study 2, bigender nouns were presented in their canonical unaltered form (e.g., /artista/ ‘artist’).

As described above, in this study, the stimuli were auditorily presented. They were recorded with a professional microphone Shure SM57 by a female native Italian speaker who was born and raised in Northern Italy (i.e., Milan, Lombardy). The final vowel sound of each word was analyzed acoustically to test whether F1 and F2 formant values aligned with typical central vowel formant values (500 Hz and 1,500 Hz, respectively). Some of the stimuli were then re-recorded under identical environmental conditions to ensure an acceptable acoustic distance from the other vowels in Standard Italian’s phoneme inventory. The final formant values for each stimulus and a chart showing their distribution in the vowel space are available in Supplementary material (cf. Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). Finally, each word was extracted as a separate audio file, AC contamination was filtered at 50 Hz, and the volume was normalized to maximize audibility using the Praat script package GSU Tools (Owren, 2008).

Given the fleeting nature of auditory input and the subsequent demands on real-time processing, in this study participants did a practice task with three role nouns that were not included in the analyses. To ensure a similar experience for all participants, the study could only be accessed on a computer, not on mobile devices, and the participants were required to confirm that they were wearing headphones before starting. They were also given the opportunity to repeat the short practice if they needed more time to adjust the volume.

5.2 Results

The final dataset consisted of 5,100 observations. As a preliminary step, the scores, originally recorded on a scale from 1 to 100 (see Footnote 5), had to be rescaled from 0 to 100 in order to allow for a comparison with the results of Studies 1 and 2. Figure 5 shows the distribution of the responses.

Figure 5. Ratings distributions associated with role nouns in Study 3, ordered by median value. The vertical markers in each boxplot represent the median rating. Noun’s class (schwa or bigender) is color-coded.

Participants’ responses to the nouns ranged from an average score of 20.66 (allevatorə, ‘breeder’) to 78.13 (estetista, ‘beautician’), with the majority of answers clustered around an overall mean score of 46.18 (SD = 22.73) for bigender nouns and 44.35 (SD = 25.99) for neutralized nouns. Consistently with Study 2, 9 out of the 10 neutralized nouns that were considered more likely to refer to male professionals (range = 20.66–34.72) ended in -torə, with the only exception being contadinə (‘farmer’). The ratings for the rest of the role nouns (both neutralized and bigender) converged toward the central values (Figure 5). In other words, they were generally considered as likely to be associated with masculine or feminine referents, except for a small number of nouns referring to stereotypically feminine professions, such as casalingə (‘housekeeper’) and cartomante (‘fortune-teller’), which were rated higher. In analogy with the previous studies, we computed a centered score as detailed in Section 2.1 and found the following mean values: −0.04 for bigender nouns and − 0.06 for neutralized nouns. We then tested whether the ratings were significantly different based on the lexical form of the nouns. The results of the linear mixed effect model on the centered score showed that ratings were not significantly different based on the lexical form of the noun (t = −0.13, p = 0.892). We then computed the absolute score and we computed the means for each noun type: 0.14 for bigender nouns and 0.18 for neutralized nouns. Results from the linear mixed-effect model on the absolute score showed that bigender nouns were perceived as closer to zero compared to neutralized nouns (t = −2.42, p = 0.017). This effect was significantly influenced by the interaction between the lexical form of the nouns and participants’ age (t = 3.76, p < 0.001): as participants’ age increased, neutralized nouns were perceived as less neutral, while bigender nouns were perceived as more neutral. No other significant results emerged.

5.3 Discussion

In Study 3, we tested gender associations of 68 role nouns presented auditorily. While around half of these nouns (N = 38) were bigender and were presented to participants in their canonical form, the rest (N = 30) were neutralized by substituting the grammatical ending with a schwa phoneme, in order to test whether the neutralization would reduce gender associations. As in Study 2, the wide range of responses obtained for both bigender (from 22.98 to 78.13) and neutralized nouns (from 20.66 to 71.88) indicated that the absence of grammatical information regarding gender did not neutralize the gender stereotypical associations, especially for female- or male-dominated professions. Regarding neutralized nouns specifically, the role of the surface form of words seemed to play an even more important role in this auditory study than in Study 2, since almost all neutralized nouns ending with the suffix -torə (except contadinə, ‘farmer’) were considered more likely to refer to men than women. This finding may be due to the limited prominence of word-final phonemes in speech (especially of reduced vowels), compared to the visually salient ə grapheme, which, in the previous study, led to neutral scores for the grammatically marked nouns ending in -torə that do not carry strong stereotypical associations (e.g., collaboratorə, ‘coworker’; organizzatorə, ‘organizer’). The rest of the neutralized nouns were generally considered gender-neutral, except for a limited number of nouns at the higher end of the scale, i.e., those referring to roles traditionally taken on by women. While it is tempting to interpret this finding in terms of a possible female bias, it is worth pointing out that most of the other role nouns achieved neutrality, even those that were not considered exclusively masculine in Study 1, such as the grammatically masculine impiegato[MASC], ‘employee’ (M = 18.50) and cuoco[MASC], ‘cook’ (M = 15.53). Crucially, when considering the absolute distance to the neutral zero value, bigender nouns were evaluated closer to the neutral value than the neutralized nouns in schwa. However, this effect was modulated by the participants’ age. Indeed, ratings were closer to neutrality for younger than older participants. This might depend on the familiarity with the symbol and participants’ experience in being exposed or in using inclusive language, which are presumably higher in younger generations. Another possibility is that older participants relied more on the stem of the noun in evaluating the neutralized nouns, potentially ignoring the symbol. Overall, the responses to auditory stimuli further highlighted the critical challenge of providing a truly gender-neutral alternative to neutralized forms that resemble grammatically masculine suffixes (i.e., -tore) and, therefore, elicit strong associations with the masculine gender. In addition, the persistence of strong stereotypical associations with a small number of feminine nouns suggests that, even when the surface form of these nouns does not carry gender information, speakers do not perceive them as genuinely neutral.

6 Comparative analyses across studies

In this section, we will compare the results of the three studies by running linear mixed-effect models on a dataset that included all participants. The questions that can be answered by these analyses are: (a) whether the ratings on bigender nouns are consistent across studies; (b) whether the ratings on masculine and feminine nouns are significantly neutralized by the adoption of schwa, by comparing gender-marked vs. gender-neutralized forms of the same nouns across studies; and (c) if there is a difference in the effectiveness of neutralization between the use of schwa in the written form and its use in the oral form, by comparing ratings on the gender-neutralized forms in Study 2 and 3.

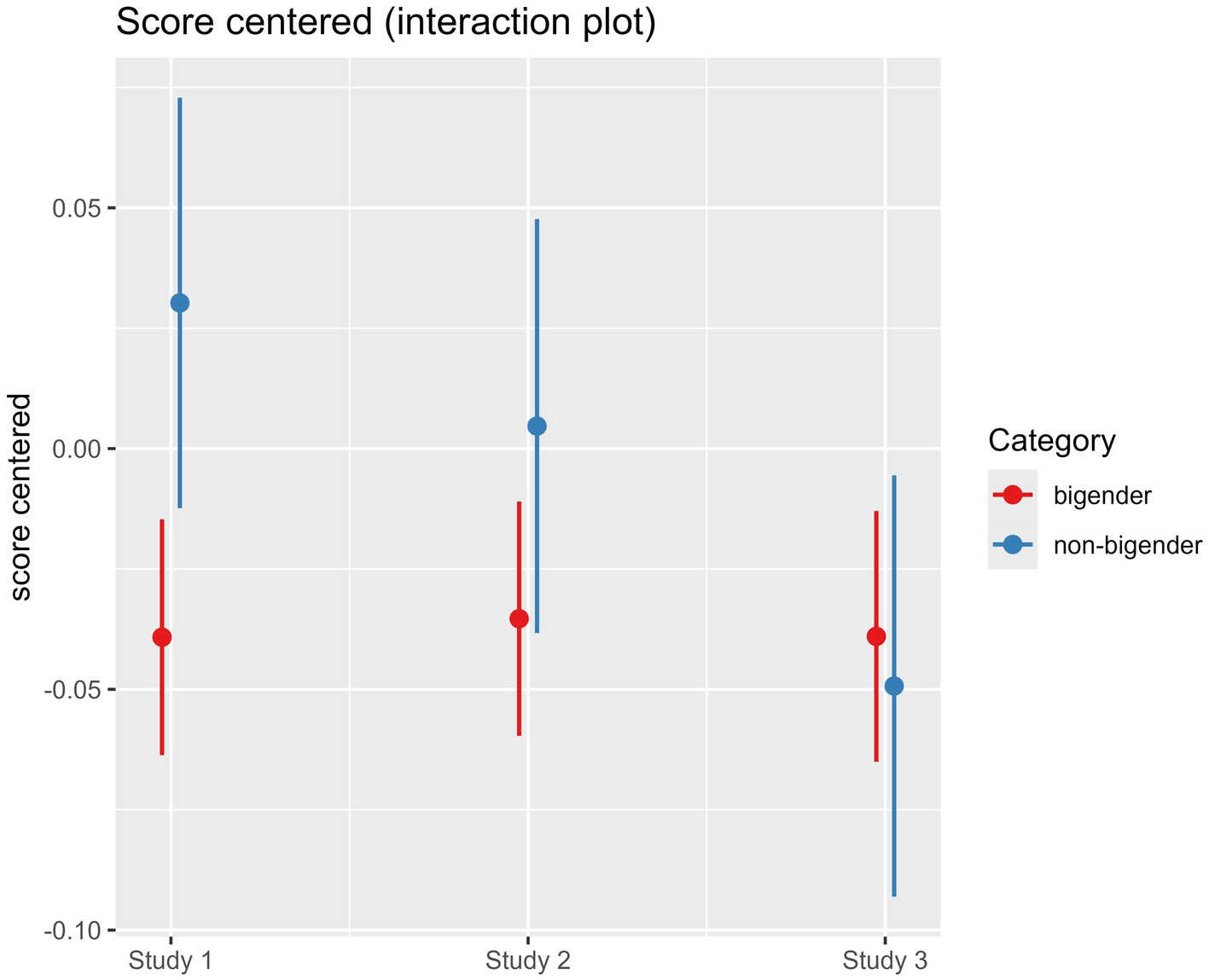

We first operated a selection of the role nouns that were shared across the studies, resulting in a subset of 60 nouns, 30 bigender and 30 that appeared either in their gendered form (Study 1) or in their neutralized form (Studies 2 and 3). We then created a two-level variable category by adding a column to the dataset, in which masculine and feminine nouns from Study 1 and neutralized nouns from Study 2 and 3 were labeled as non-bigender, while bigender nouns from the three studies were labeled as bigender.

We then computed the centered score adopted in the analyses of the three studies (cf. section 2.1). Considering that in the following analysis, the variable relative to noun gender is substituted by the variable category (bigender/non-bigender), the absolute score eliminating the polarity of masculine and feminine nouns is no longer needed.

The mean ratings obtained by bigender nouns in the three studies are, respectively: −0.039 in Study 1, −0.035 in Study 2, and −0.037 in Study 3. Average ratings on non-bigender (neutralized) nouns are, respectively: 0.030 in Study 1, 0.004 in Study 2, and −0.049 in Study 3.

To address the questions outlined above, we developed a (nested) linear mixed-effect model with the centered score as the dependent variable, the category of the noun (i.e., the two-level variable described above), and the study (three-level variable: Study 1, 2, 3), together with their mutual interaction as independent variables, and participants and items as random intercepts.8 For comparison purposes, Study 2 was set as the reference level of the variable study in the analyses. Nested comparisons showed that (a) judgments on bigender nouns were consistent across studies (Study 1 vs. Study 2: t = −0.78, p = 0.473; Study 3 vs. Study 2: t = −0.52, p = 0.600); (b) ratings on the gender-marked nouns in Study 1 were significantly different from those obtained on the same nouns in their written form using ə in Study 2 (t = 3.69, p < 0.001); and (c) there is a difference in the effectiveness of neutralization between the use of ə in the written and oral modality, as shown by the significant difference between neutralized nouns in Study 3 compared to Study 2 (t = −6.30, p < 0.001). The full model output is available in the OSF repository. Figure 6 shows the effect plot of the interaction model.

Figure 6. Effect plot of the interaction between Noun’s Category (bigender vs. non-bigender) and Study.

7 General discussion

The present research aimed to investigate the efficacy of a gender-inclusive language proposal in Italian, specifically the adoption of the symbol ə as a gender-neutral word-ending for role nouns. By means of three studies, we aimed to contribute with a first baseline assessment of the efficacy of this intervention in making a noun ‘neutral’ with respect to gender. This preliminary assessment is a first, necessary, step prior to evaluating any higher-order effects of GIL interventions, such as broader cognitive and socio-psychological effects and their impacts on gender societal disparities.

Study 1 aimed primarily to establish a baseline regarding gender associations related to two types of noun categories in Italian: gender-marked nouns (masculine and feminine) and bigender nouns, which refer to people irrespectively of their gender. Study 2 included the same bigender nouns and the nouns that were gender-marked in Study 1, now neutralized through the adoption of the schwa symbol as a gender-unmarked word ending. Finally, given that this proposal is also tailored for spoken language, we aimed to test its effectiveness in neutralizing gender information also in the auditory modality. As explained in the introduction, the use of the schwa in spoken language could present several issues, as this sound is not part of the phonemic inventory of standard Italian but is a variant of some southern dialects. The goal of Study 3 was to test whether neutralized role nouns were actually perceived as neutral in the auditory modality by native Italian speakers.

In Study 1, the gender associations found for bigender nouns showed that expectations regarding the referent’s gender may emerge even in the absence of grammatical marking. The strength of these expectations for grammatically gender-marked nouns was more pronounced for grammatically feminine nouns than for masculine ones. We interpreted this finding as the effect of the generic interpretation of the masculine form, which can be used in Italian as the unmarked gender form (Cacciari and Padovani, 2007). Notably, this effect is stronger in older participants.

Study 2 and Study 3 showed that the adoption of the schwa as a gender-neutral suffix reduced the expectations regarding role nouns, without fully eliminating them. For cases where the form of the neutralized noun evokes the masculine, or when there is a strong stereotypical association, as with stereotypically feminine nouns, the neutralized form seems largely ineffective. Nouns with strong female stereotypical associations (such as “housekeeper” and “secretary”) were not perceived as genuinely neutral, and neutralized variants of the grammatically masculine suffixes (i.e., those ending in -tore, neutralized as -torə) elicited strong associations with the masculine gender. This latter finding might be attributable to the morpho-phonological form of words ending in -tore, which are strongly masculine-marked, being their feminine form -trice.

Overall, our findings answer these broader research questions: (1) Is schwa in the written and auditory form (equally) effective in neutralizing expectations about the referent’s gender of role nouns? (2) Is schwa effective in reducing gender stereotypical associations on role nouns?

The answer to the first question is “more yes than no”: the analysis reported in Section 6 demonstrates the effectiveness of the ə in neutralizing the gender of nouns, suggesting a probable attenuation of gender associations with specific nouns. Nonetheless, this conclusion needs to be taken with caution. First, bigender nouns were overall perceived as more neutral than nouns neutralized with schwa, both in their oral and written forms. Second, the efficacy of schwa was significantly reduced in older participants: as participants’ age increased, their perception of schwa became less neutral. Notably, this effect emerged from a relatively low age threshold, starting around 30 years of age. Third, schwa in the auditory modality was less effective than in the written modality: in the case of oral schwa, the average ratings shifted significantly toward negative values, indicating a stronger association with the masculine gender. This finding might be motivated by the fact that the Italian spoken language is characterized by significant regional variability and that the introduction of a new phoneme—much more than a new grapheme—could conflict with certain regional variants. Specifically, in some southern dialects, such as Campanian and Apulian, word-final vowels are often reduced to /ə/ regardless of their gender marker (Repetti, 2000), and a word like collaboratore[MASC] would sound exactly like the neutralized version collaboratorə that we have used in this study, whereas its feminine counterpart would sound remarkably different (collaboratricə). It is, therefore, unsurprising that words that exhibit a marked difference between their masculine and feminine forms may be perceived as grammatically masculine. It is worth mentioning, though, that the majority of the participants in Study 3 were from the north of Italy. Nevertheless, these dialectal variants are well-represented in movies, television programs, and popular Italian shows. Therefore, this is common knowledge among native Italian speakers, even if they do not use such dialects.

Turning to the second question, namely, whether schwa is effective in reducing gender stereotypical associations, the answer is “more no than yes”: the comparison between neutralized forms and bigender nouns demonstrated that the latter are, overall, perceived as being more neutral than the former. Despite being gender-neutral in their form, the evaluation of neutralized nouns in terms of their perceived gender is closely linked to stereotypical expectations, similar to what happens in the case of role nouns in natural gender languages like English (Canal et al., 2015). Indeed, the inclusive forms of ‘housekeeper’ and ‘secretary’ showed female stereotypical associations despite their neutralized form. The effect emerges in spite of the small number of stimuli strongly linked to predominantly female-dominated professions. Therefore, this effect may emerge even more strongly if a larger number of such nouns were included, as done in other studies (e.g., Cacciari and Padovani, 2007; Pesciarelli et al., 2019).

As an overall conclusion, our results suggest that the schwa neutralizes the gender information conveyed by the gender-marked suffix of the noun in the younger population. However, the schwa does not seem to act as an explicit marker of neutrality. Speculatively, for words neutralized by schwa, participants might have simply relied on the noun’s stem to make their judgments.

As with all studies, this research has limitations but also highlights interesting issues worth exploring in future research. One limitation is that the measure used in this work is explicit. It would be very interesting to test the effects of this form of inclusive language in an implicit manner (for example, through eye-movement recording or event-related potentials) in order to obtain a more reliable measure of its linguistic processing. Another limitation is that we presented stimuli in their singular form and in isolation. A clearer picture would emerge by testing the neutralized role nouns embedded in texts, as sentential/discourse context might have an effect that we could not observe in the current work and would add ecological validity to the investigation.

Our findings are also of possible interest in light of the still-alive debate surrounding generic masculine. Indeed, some studies (e.g., Gygax et al., 2008; Redl et al., 2022) have shown that when a noun is presented in its masculine form, a representation of a male referent is automatically activated. The results of our work are far from attempting to contribute to this issue, although the finding that role nouns in their masculine form are perceived as more neutral, or certainly less marked, compared to the same role nouns in their feminine form, contributes interesting data to the current debate.

Finally, it is of paramount importance to consider the tradeoff between gains and disadvantages of burdening the linguistic system by introducing a change in the morphosyntactic and morphophonological linguistic domains. Particularly for those GIL proposals that incorporate symbols, an important issue to consider in future research is the impact of these novel forms on text reading, especially in terms of potential disruptions for individuals with reading difficulties. With regard to this issue, we believe there is a risk of including one category of people while excluding another.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study can be found in online repositories and can be accessed here: https://osf.io/qrk58/?view_only=def06d88e8db468581e17109b0beef5f.

Author contributions

MA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. VG: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. VB: Writing – review & editing. CR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FF: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was supported by Fondazione Cariplo (project number: 2022-1586; call: Inequalities Research -Generare conoscenza per ridurre le disuguaglianze 2022; project title: Reducing gender inequalities through language: efficacy and feasibility of Italian gender-inclusive language).

Acknowledgments

We thank Alessandro Gabbiadini, Federico Faloppa, Marco Marelli, Giulia Bettelli, Giulio Puzella, Edoardo Zulato and Anita Cainelli for a thorough discussion of initial ideas.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1530778/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The schwa proposal was originally formulated by Luca Boschetto (https://italianoinclusivo.it/), picked up and further elaborated in Vero Gheno’s publications.

2. ^Cf. Andrea Iacona’s contribution on this issue: https://accademiadellacrusca.it/it/contenuti/cari-tutti/19528.

3. ^Giuliana Giusti is a professor of linguistics and one of her notable works on inclusive language is titled “Inclusività della lingua italiana, nella lingua italiana: come e perché. Fondamenti teorici e proposte operative” (lit. “Inclusivity of the Italian Language, in the Italian Language: How and Why. Theoretical Foundations and Practical Proposals”). Massimo Arcangeli, a linguist and expert of communication, published the book “La lingua scema: Contro lo schwa (e altri animali),” lit. ‘The stupid/vanishing language: against the schwa (and other animals)’, in which he uses the ambiguous word “scema” (stupid/vanishing) to express his opinion against the introduction of the schwa proposal. Andrea De Benedetti, an Italian journalist, published the book “Così non schwa. Limiti ed. eccessi del linguaggio inclusivo,” lit. ‘This (the schwa) does not work. Limitations and exaggerations of inclusive language’, Cecilia Robustelli is a professor of Italian linguistics and published the contribution “Lo schwa al vaglio della linguistica,” lit. “the schwa under linguistic scrutiny” (in the volume La grande restaurazione 21).

4. ^https://accademiadellacrusca.it/it/consulenza/un-asterisco-sul-genere/4018

5. ^For a technical requirement of the Labvanced platform, the slider started from 1 in Study 3.

6. ^Originally, we employed 134 role nouns but some of the nouns, specifically avvocato (‘lawyer’), ingegnere (‘engineer’), banchiere (‘banker’), ministro (‘minister’), have undergone changes in their usage, shifting from being considered bigender to being marked for gender when the feminine form of the same nouns was introduced. Therefore, we decided to remove them from the set of items in the present study.

8. ^The model with participants and items as random slopes did not converge.

References

Arnold, J. E., Mayo, H. C., and Dong, L. (2021). My pronouns are they/them: talking about pronouns changes how pronouns are understood. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 28, 1688–1697. doi: 10.3758/s13423-021-01905-0

Bambini, V., and Canal, P. (2021). “Neurolinguistic research on the romance languages” in Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Banaji, M. R., and Hardin, C. D. (1996). Automatic stereotyping. Psychol. Sci. 7, 136–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00346.x

Bertinetto, P. M., and Loporcaro, M. (2005). The sound pattern of standard Italian, as compared with the varieties spoken in Florence, Milan and Rome. J. Int. Phon. Assoc. 35, 131–151. doi: 10.1017/S0025100305002148

Best, C. T., and Tyler, M. D. (2007). “Nonnative and second-language speech perception” in Language experience in second language speech learning: In honor of James Emil Flege. eds. O.-S. Bohn and M. J. Munro (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 13–34.

Burnett, H., and Bonami, O. (2019). Linguistic prescription, ideological structure, and the actuation of linguistic changes: grammatical gender in French parliamentary debates. Lang. Soc. 48, 65–93. doi: 10.1017/S0047404518001161

Burnett, H., and Pozniak, C. (2021). Political dimensions of gender inclusive writing in Parisian universities. J. Socioling. 25, 808–831. doi: 10.1111/josl.12489

Cacciari, C., Carreiras, M., and Cionini, C. B. (1997). When words have two genders: anaphor resolution for Italian functionally ambiguous words. J. Mem. Lang. 37, 517–532. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1997.2528

Cacciari, C., and Padovani, R. (2007). Further evidence of gender stereotype priming in language: semantic facilitation and inhibition in Italian role nouns. Appl. Psycholinguist. 28, 277–293. doi: 10.1017/S0142716407070142

Canal, P., Garnham, A., and Oakhill, J. (2015). Beyond gender stereotypes in language comprehension: self sex-role descriptions affect the brain’s potentials associated with agreement processing. Front. Psychol. 6:Article 1953. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01953

Casado, A., Sá-Leite, A. R., Pesciarelli, F., and Paolieri, D. (2023). Exploring the nature of the gender-congruency effect: implicit gender activation and social bias. Front. Psychol. 14:1160836. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1160836

De Benedetti, A. (2022). Così non schwa: Limiti ed eccessi del linguaggio inclusivo. Torino: Einaudi.

Garnham, A., Finnegan, E., and Oakhill, J. (2015). Counter-stereotypical pictures as a strategy for overcoming spontaneous gender stereotypes. Front. Psychol. 6:869. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00869

Gheno, V. (2021). Femminili Singolari: Il Femminismo È Nelle Parole. Edizione ampliata. Firenze: Effequ.

Giusti, G. (2022). Inclusività della lingua italiana: Come e perché. Fondamenti teorici e proposte operative. DEP. Deportate, esuli, profughe. 48, 1–22.

Gygax, P., Gabriel, U., Sarrasin, O., Oakhill, J., and Garnham, A. (2008). Generically intended, but specifically interpreted: when beauticians, musicians, and mechanics are all men. Lang. Cogn. Process. 23, 464–485. doi: 10.1080/01690960701702035

Horacio, B., and Carreiras, M. (2005). Grammatical gender and number agreement in Spanish: an ERP comparison. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 17, 137–153. doi: 10.1162/0898929052880101

Körner, A., Abraham, B., Rummer, R., and Strack, F. (2022). Gender representations elicited by the gender star form. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 41, 553–571. doi: 10.1177/0261927X221080181

Levelt, W. J. M., Roelofs, A., and Meyer, A. S. (1999). A theory of lexical access in speech production. Behav. Brain Sci. 22, 1–38. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X99001776

Lindqvist, A., Renström, E. A., and Sendén, M. G. (2019). Reducing a male bias in language? Establishing the efficiency of three different gender-fair language strategies. Sex Roles 81, 109–117. doi: 10.1007/s11199-018-0974-9

Misersky, J., Gygax, P. M., Canal, P., Gabriel, U., Garnham, A., Braun, F., et al. (2014). Norms on the gender perception of role nouns in Czech, English, French, German, Italian, Norwegian, and Slovak. Behav. Res. Methods 46, 841–871. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0409-z

Molinaro, N., Barber, H. A., and Carreiras, M. (2011). Grammatical agreement processing in reading: ERP findings and future directions. Cortex 47, 908–930. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.02.019

Mornati, G., Riva, V., Vismara, E., Molteni, M., and Cantiani, C. (2023). Infants aged 12 months use the gender feature in determiners to anticipate upcoming words: an eye-tracking study. J. Child Lang. 50, 841–859. doi: 10.1017/S030500092200006X

Osterhout, L., Bersick, M., and McLaughlin, J. (1997). Brain potentials reflect violations of gender stereotypes. Mem. Cogn. 25, 273–285. doi: 10.3758/BF03211283

Owren, M. J. (2008). GSU Praat tools: scripts for modifying and analyzing sounds using Praat acoustics software. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 822–829. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.822

Padovani, R., and Cacciari, C. (2003). Il ruolo della trasparenza morfologica nel riconoscimento di parole in Italiano. Giornale italiano di psicologia. 30, 749–772.

Pesciarelli, F., Scorolli, C., and Cacciari, C. (2019). Neural correlates of the implicit processing of grammatical and stereotypical gender violations: a masked and unmasked priming study. Biol. Psychol. 146:107714. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2019.06.002

Redl, T., Szuba, A., de Swart, P., Frank, S. L., and de Hoop, H. (2022). Masculine generic pronouns as a gender cue in generic statements. Discourse Process. 59, 828–845. doi: 10.1080/0163853X.2022.2148071

Robustelli, C. (2021). “Lo schwa al vaglio della linguistica”, in La grande restaurazione. eds. C. Sciuto Milano: Mondadori. 6–18.

Sanford, A. J., and Filik, R. (2007). ‘They’ as a gender-unspecified singular pronoun: eye tracking reveals a processing cost. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 60, 171–178. doi: 10.1080/17470210600973390

Schriefers, H., Jescheniak, J. D., and Levelt, W. J. M. (1999). Temporal characteristics of semantic and phonological processes in speech production. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 25, 1153–1176. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.25.4.1153

Silverstein, M. (1985). “Language and the culture of gender: at the intersection of structure, usage, and ideology” in Semiotic mediation. eds. E. Mertz and R. J. Parmentier (San Diego: Elsevier), 219–259.

Siyanova-Chanturia, A., Warren, P., Pesciarelli, F., and Cacciari, C. (2015). Gender stereotypes across the ages: on-line processing in school-age children, young and older adults. Front. Psychol. 6:1388. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01388

Tibblin, J., Granfeldt, J., van de Weijer, J., and Gygax, P. (2023). The male bias can be attenuated in reading: on the resolution of anaphoric expressions following gender-fair forms in French. Glossa Psycholing. 2, 1–19. doi: 10.5070/G60111267

Vergoossen, H. P., Pärnamets, P., Renström, E. A., and Sendén, M. G. (2020). Are new gender-neutral pronouns difficult to process in reading? The case of ‘hen’ in Swedish. Front. Psychol. 11:574356. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.574356

Keywords: gender stereotypes, gender inclusive language, generic masculine, role nouns, schwa

Citation: Abbondanza M, Galimberti V, Bonomi V, Reverberi C, Durante F and Foppolo F (2025) Neutralizing gender in role nouns: investigating the effect of ə in written and oral Italian. Front. Commun. 9:1530778. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1530778

Edited by:

Valentina Bambini, University Institute of Higher Studies in Pavia, ItalyReviewed by:

Filippo Domaneschi, University of Genoa, ItalyAndrea Beltrama, University of Delaware, United States

Copyright © 2025 Abbondanza, Galimberti, Bonomi, Reverberi, Durante and Foppolo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martina Abbondanza, bWFydGluYS5hYmJvbmRhbnphQHVuaW1pYi5pdA==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Martina Abbondanza

Martina Abbondanza Valeria Galimberti

Valeria Galimberti Valeria Bonomi

Valeria Bonomi Carlo Reverberi

Carlo Reverberi Federica Durante

Federica Durante Francesca Foppolo

Francesca Foppolo