94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 13 January 2025

Sec. Media Governance and the Public Sphere

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1517963

Maud Reveilhac*†

Maud Reveilhac*† Camille Nchakga

Camille NchakgaIn an increasingly fragmented media landscape, YouTube has become a pivotal platform for alternative media channels that challenge mainstream media and governmental narratives. This study investigates how French alternative media channels on YouTube shape their identities and discourse regarding the government. The study analyzes content from these channels to understand their impact on the media ecosystem. Using word embedding and correspondence analysis, the study reveals a strong antagonistic stance toward mainstream media and government. Findings show that alternative media channels function as new gatekeepers, using decentralized mechanisms to disseminate information, thus redefining traditional gatekeeping roles. They simultaneously provide factual content and amplify skeptical narratives, contributing to public mistrust in journalism and governmental institutions. The implications are discussed along the evolving role of alternative media in shaping public perceptions and the need for ongoing research to capture these complex interactions in an ever-changing media landscape.

In an increasingly fragmented media landscape, alternative media channels on YouTube are not only dissident voices but also active sites of contestation, often in direct opposition to governments and “mainstream” media outlets (e.g., Rauchfleisch and Kaiser, 2020). These channels shape themselves as bastions of freedom of expression, platforms for diverse opinions, and avenues for representing marginalized and popular classes. They challenge mainstream media’s legitimacy, which they often portray as concentrated in the hands of a few powerful financial and political entities. This framing is supported by investigative reports, such as “Médias français, qui possède quoi? [French media, who owns what?]” (Diplomatique, 2023), that reveal ownership patterns in French media.

This study situates itself within the broader framework of the hybrid media system (Chadwick, 2017), which recognizes the interplay and interconnectedness between alternative/digital media and traditional/legacy media. While the channels analyzed here position themselves as alternative to legacy media, by claiming their ideological and financial independence, these boundaries may blur in practice. For example, content from alternative media can be picked up or referenced by legacy media outlets and vice versa. The study aims to examine whether the channels selected for this analysis represent a radical detachment from legacy media or merely a reconfiguration within the hybrid system.

Against this background, alternative media channels on YouTube assert their financial and ideological independence, emphasizing that “freedom of information has a price.” In a poignant appeal to their viewers, these channels solicit donations to ensure their “survival” and continue their “fight” for free information, thereby resonating as a rallying cry for those who feel marginalized by traditional media. These alternative media channels also position themselves as a counterweight to dominant narratives (Lewis, 2018), promising “popular, alternative, and independent information” in opposition to the “reactionary and corporate propaganda funded by billionaires” (quotes retrieved from descriptions of YouTube channels in our corpus). Some channels aim to achieve their goal of becoming truly representative television channels, denouncing the collusion between oligarchs and political power, and thus positioning themselves as the voices of social struggles (Fuchs, 2021; Holt et al., 2019).

These examples illustrate how alternative media channels on YouTube not only seek to inform but also to mobilize and unify an audience around common values of social justice and freedom of expression. Their emergence and growth reflect a growing demand for diverse and critical media perspectives, in contrast to existing power structures. This trend is further emphasized by YouTube’s role as a central medium. Due to its logic and architecture, especially the personalized recommendation of content, YouTube runs the risk of acting as a “radicalizer” (Ribeiro et al., 2020; Röchert et al., 2022). Platforms such as YouTube are designed to retain users for as long as possible, with algorithms often favoring content that is hostile to traditional media (Nocun and Lamberty, 2020).

Overall, these channels seek to create alternative spaces for information and discourse. This strategy reflects their role as subaltern “counterpublics” (Fraser, 1992), which is a theoretical lens through which this study analyzes how these channels articulate their identities and strategies in opposition to traditional media. The notion of counterpublics aligns with Habermas (1962) model of the “public sphere” which is relevant for examining how these channels attempt to rehabilitate a form of online democratic deliberation, often perceived as compromised in traditional media. The great heterogeneity of content is what gives a YouTube channel its ability to take on the attributes of the public sphere.

Moreover, the study examines their “gatekeeping” practices (Shoemaker and Vos, 2009) in a decentralized media environment, assessing how they operate as alternative sources of authority on YouTube. Assessing the channels’ gatekeeping role in modern developments (Thorson and Wells, 2016), helps us understand how these channels redefine the practices of information selection and dissemination, often in opposition to the filtering processes of major media. By challenging the traditional roles of gatekeepers, these platforms advocate for transparency and a plurality of voices often absent from dominant media discourses. Depending on the resources and professionalization of the persons or teams involved, journalistic and debunking abilities allow them to carry out tasks like dispelling false information, but with differing degrees of rigor. The study also aims to provide insights on how these gatekeeping duties are carried out.

By applying these theoretical frameworks, this study investigates how French alternative media channels construct their identities, position themselves against the government, and influence the broader media ecosystem. Specifically, using word embedding and correspondence analysis, the study identifies discourse challenging mainstream media and government, as well as different roles of alternative news channels in regard to gatekeeping practices. Findings from this research will show how alternative media discourse is shaping new forms of decentralized gatekeeping practices that challenge dominant media narratives, fostering alternative media production, and contributing to the development of an alternative public sphere.

The concept of “subaltern counterpublics” (Fraser, 1992) refers to alternative discursive spaces where marginalized groups can articulate counter-narratives and challenge mainstream ideologies. Fraser builds on Habermas’s notion of the “public sphere” (Habermas, 1989) but critiques its idealized nature, arguing that dominant public spheres often exclude particular social groups and perspectives. In contrast, subaltern counterpublics offer spaces for these groups to circulate their own discourses, enabling identity formation and political mobilization beyond the reach of dominant media narratives. However, these counterpublics are not inherently virtuous, sometimes harboring antidemocratic tendencies, as evidenced by the rise of the far-right (Figenschou and Ihlebæk, 2018; Lewis, 2018). Recent research is therefore also interested in the comments space on the YouTube platform and how this space can be affected by heated debates (Lyubareva et al., 2021).

In this study, subaltern counterpublics are operationalized through a focus on how alternative YouTube channels position themselves as counter-narratives to mainstream media, particularly regarding inclusiveness and legitimacy in news discourse. By analyzing the content and descriptions of these channels, we explore how they cultivate identities as platforms for “popular, alternative, and independent information,” which resonates with audiences who perceive themselves as marginalized by dominant narratives. This approach recognizes that while alternative media channels often position themselves in opposition to legacy media, interactions between these two spheres may occur, reflecting elements of the hybrid media system (Chadwick, 2017). For example, alternative narratives introduced by these channels can permeate mainstream discourse, and conversely, legacy media content may be referenced or critiqued by alternative outlets (Hameleers and Yekta, 2023; Harcup, 2003).

This perspective allows for an examination of how these channels serve as spaces where excluded voices can critique government policies and mainstream media representations, aligning with the role of subaltern counterpublics in contesting hegemonic norms. Drawing from the concept of subaltern counterpublics and their relevance to alternative media channels on YouTube, the following research hypothesis can be formulated:

Hypothesis 1: Alternative media channels on YouTube engage in discourse that challenges both mainstream media and the government, serving as subaltern counterpublics that articulate distinct perspectives on social and political issues.

The gatekeeping theory traditionally focused on how journalists and editors control the flow of information to the public looking at how certain factors, such as organizational processes, editorial judgments, and individual biases, influence which news stories are reported (Shoemaker and Vos, 2009). With digitalization, however, the theory has evolved to incorporate decentralized gatekeeping practices where non-journalistic actors, such as alternative media channels and opinion YouTubers, participate in selecting and framing information. Wallace (2018) proposed a new gatekeeping model that identifies various gatekeepers, including journalists, amateurs, professionals, and algorithms, who differ in their access, selection criteria, and publication choices. The model also distinguishes between centralized (i.e., control by a central authority) and decentralized (i.e., reliance on collaborative and micro-level interactions) gatekeeping mechanisms on digital platforms.

This adaptation of the gatekeeping theory is useful in the context of the present study by highlighting how non-journalistic actors (such as opinion YouTubers and alternative media channels) can construct alternative social realities, contributing to public mistrust in journalism and government restrictions on media. Reveilhac (2024) could identify different clusters of alternative news channels based on their presentation, style, and partisanship. These clusters are labeled as “satire/entertainment,” “alternative,” “neutral/eye-witnessing,” “re-information,” and “zapping” clusters, and act as mediators between politics, entertainment, and re-information, thereby serving diverse audiences.

Alternative media already played a decisive role in the public sphere and are therefore not a particularly new phenomenon (Schwaiger and Eisenegger, 2021; Schwaiger, 2022). Nevertheless, it is assumed that alternative media are experiencing an upswing due to structural change, especially “digital” structural change. Despite this digital turn, mainstream media have been able to maintain their dominant gatekeeping role, notably by converging their productions on different platforms. For instance, mainstream media YouTube channels typically cover the same diversity of subjects as the digital or paper version of a major national press daily. Humprecht and Esser (2018) show that mainstream media oriented to the general public use social networks with the aim of attracting the largest possible additional audience (in addition to their other distribution channels) and maximizing their income. According to Eisenegger (2020), digital structural change is driven by platformization, such as the establishment of platforms like Facebook and YouTube. Central here is the increase in possible communication channels for alternative actors, media emergence — the blending of journalistic and non-journalistic content — and the long-tail metaphor, the phenomenon that numerous alternative media are in the long tail, although their reach is more limited, but their content can be disseminated effectively through networks. This means that traditional gatekeeping mechanisms can be circumvented (Neuberger et al., 2009).

Unlike traditional journalists, actors responsible of alternative news channels often lack formal journalistic training but may possess specialized skills in areas such as investigative research, technical production, or online networking, thus leveraging expertise in specific subject areas or crowd-sourced knowledge (Schweiger, 2017). Others operate with more limited resources, framing content primarily through personal or humoristic lenses. It is essential to understand capacities and constraints that shape alternative media gatekeeping practices, which range from highly professionalized to grassroots and individualistic efforts.

Critiques of mainstream media by alternative channels often center on themes of disinformation and bias. These channels position themselves as correctives to what they perceive as systemic failures of mainstream outlets to provide accurate and unbiased information. For instance, Allcott and Gentzkow (2017) highlight how the economics of fake news are often driven by incentives that can distort the truth, a critique echoed by alternative media that view mainstream outlets as complicit in spreading misinformation. By framing themselves as truth-seekers countering mainstream narratives, these channels cast mainstream media as active participants in disinformation, further reinforcing their roles as alternative gatekeepers (Allcott and Gentzkow, 2017). This stance is particularly relevant in the context of French media, where public trust in media outlets has been historically variable, often reflecting wider concerns about ownership concentration and perceived political bias (Ruellan, 2007; Croix, 2023). In this way, alternative media channels leverage this distrust by amplifying narratives that position them as trustworthy counterbalances to the mainstream press.

In the context of this study, the gatekeeping framework is applied to explore how alternative media channels on YouTube utilize platform-specific mechanisms to frame their content and disseminate it outside traditional journalistic channels. By examining the vocabulary and narrative structures employed on these channels, we seek to understand how they prioritize certain types of information and emphasize specific frames around governmental actions and mainstream media practices. This framework is essential to investigating how alternative media redefine gatekeeping roles, relying on decentralized mechanisms to influence public opinion and foster mistrust in established institutions. Given this context, the study proposes the following hypothesis related to gatekeeping practices:

Hypothesis 2: Alternative media channels on YouTube categorize their content in ways that reflect distinct approaches to government and media, emphasizing decentralized gatekeeping mechanisms that challenge traditional media practices.

This study investigates the discourse on mainstream media and government of French YouTube alternative media channels. These channels vary in political stance and are recognized for their opposition to mainstream media, often occupying a spectrum that includes both “fachosphere” channels, which are frequently criticized for promoting conspiracy theories and have faced legal issues, as well as more moderate channels that engage in nuanced critiques of the media landscape. This diversity in approach allows for a comprehensive analysis of alternative media, from radical to moderate perspectives. The selection criteria were based on two core characteristics: channels must consistently present current political news and position themselves in opposition to what they describe as the dominant media system. Here, “current political news” refers to channels that regularly discuss ongoing political events in France, while “opposition to the dominant media system” implies that these channels critique mainstream media’s perceived concentration of ownership and ideological alignment with governmental or corporate interests.

The identification of alternative media channels followed an iterative approach. First, we compiled a manual list of known alternative channels based on publicly available resources, studies on alternative media, and media watchdog reports. By exploring the recommended videos and related channels, additional channels were added to this list, provided they met the above criteria. This iterative process continued until saturation was reached, ensuring a robust and comprehensive dataset of N = 67 YouTube channels (see Annex 1 for the list of channels). The location setting on YouTube was adjusted to France, and anonymous browsing was used to avoid recommendation bias.

Following the channel selection, we retrieved videos published in 2023 using the tubeR R package. On average, between 70 and 100% of the posted videos were accessible for download, suggesting that some content was removed or restricted due to YouTube policies. This resulted in a total of n = 11,471 videos for analysis. In the next step, the youtube_transcript_api Python package was used to transcribe these videos. While some videos had pre-existing subtitles, most required transcription. The final corpus consists of nt = 11,167 (97%) valid video transcripts, which form the primary dataset for analysis.

To test Hypothesis 1, which proposes that alternative media channels on YouTube engage in discourse challenging mainstream media and the government, the study utilizes word embedding (hereafter WE) analyses. This method offers a flexible approach allowing for a deeper understanding of the semantic relationships between words by representing them as vectors in a multi-dimensional space, allowing for the identification of associations, synonyms, and thematic linkages within the discourse (Sahlgren and Lenci, 2016). Specifically, the word2vec model (Mikolov et al., 2013) was chosen to model these semantic relationships, as it has been shown to effectively capture linguistic patterns through 100-dimensional word vectors, generated with the skip-gram algorithm and hierarchical softmax for optimization. This model was implemented using the wordVectors R package (Schmidt, 2017), with a window size of 10 to balance resource use and contextual depth. Lemmatization with the udpipe R package was applied to enhance the accuracy of word embedding relationships by reducing words to their root forms. This step is crucial for ensuring that variations in word forms do not obscure the underlying semantic patterns relevant to the channels’ discourse. A similar approach was used by Reveilhac and Blanchard (2022) to uncover important dimensions of the discourse on health technologies. Hypothesis 1 is tested in two steps. First, we start by investigating the terms employed by alternative media channels that are closely associated information (“information,” “misinformation”), mainstream media (“media,” “mainstream,” “journalist”) and government (“government”). Second, semantic relationships between information and mainstream media, as well as between information and government are visualized using concept maps. These maps highlight word associations that reveal implicit and explicit framings. Furthermore, to better understand how alternative channels construct oppositional identities to mainstream media, a concept map is used to reflect the opposing terms along the “alternative-mainstream” and “information-disinformation” continuums.

For Hypothesis 2, which examines the categorization of channels based on their approach to mainstream media and government, correspondence analysis (hereafter CA) is applied. This method relies on the results from word embedding that enabled us to identify terms commonly used to engage in discourse challenging mainstream media and government. These terms form a “critical vocabulary,” which includes terms like “alternative,” “truth,” “propaganda,” and “censorship,” and CA identifies salient dimensions (or continuums) from this critical vocabulary. CA thus provides a framework for understanding the dimensions along which these channels position themselves in relation to mainstream media. Practically, we aggregate all video transcripts from each channel into a single document, creating a Document-Term Matrix (DTM), where cells represent the proportion of words relative to the total vocabulary of each channel. The DTM is transposed so that rows represent words and columns represent channels. The DTM was calculated using the quanteda R package, and the CA performed with the ca() function from the FactoMineR package. The CA outputs reveal clusters of channels with similar discursive practices, allowing us to explore whether specific subgroups within alternative media emphasize different criticisms or prioritize certain aspects of their discourse on mainstream media and government. By examining the position of each channel along the CA dimensions, we can identify whether these channels form coherent factions, either within alternative media or in contrast to legacy media representations. This clustering analysis also adds a layer of theoretical depth by highlighting potential divides within alternative media discourse itself, enriching our understanding of the diversity within these opposition channels.

Figure 1 summarizes the adopted methodology.

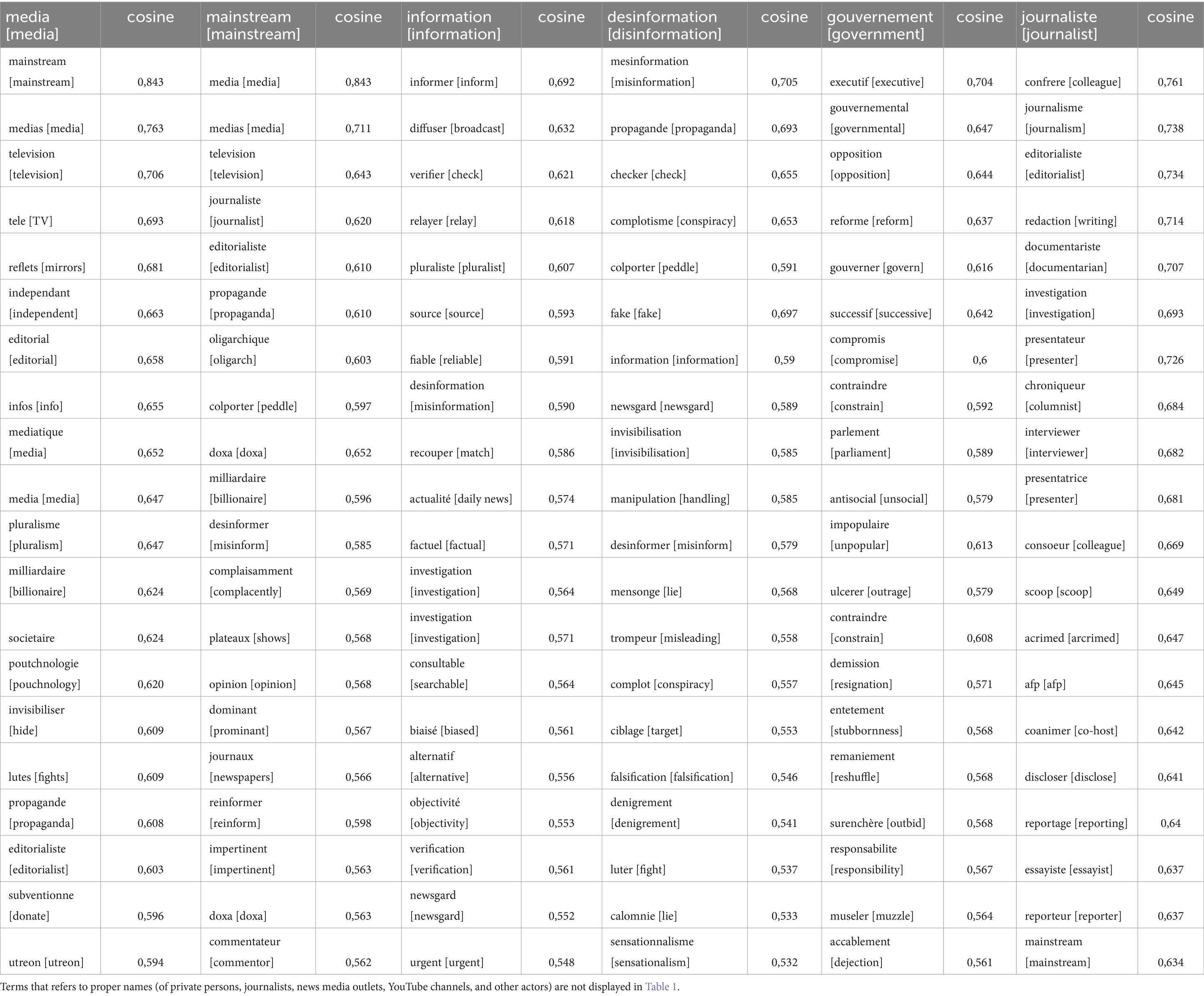

To evaluate hypothesis 1 according to which alternative news channels on YouTube engage in discourse that challenges mainstream media and the government, the trained word2vec model was used to access nearest n words closest to the words “media,” “mainstream,” “information,” “misinformation,” “government” and “journalist.” Table 1 shows that terms similar to media include “mainstream,” “pouchnology,” “pluralism,” “billionaire,” which suggests a criticism against the organization of the French media system. Looking at the terms similar to mainstream media, the term “doxa” appears on the top of the list. Information is related to positive terms such as “check,” “verification,” “alternative,” but also more negative terms such as “biased” and “newsgard.” Concerning the disinformation, it is closely related to democratic issues such as “conspiracy” and “propaganda,” and also more generic terms such as “lie” and “sensationalism.”

Table 1. Closest lemmas to mainstream and government related terms, with English translation into squared brackets.

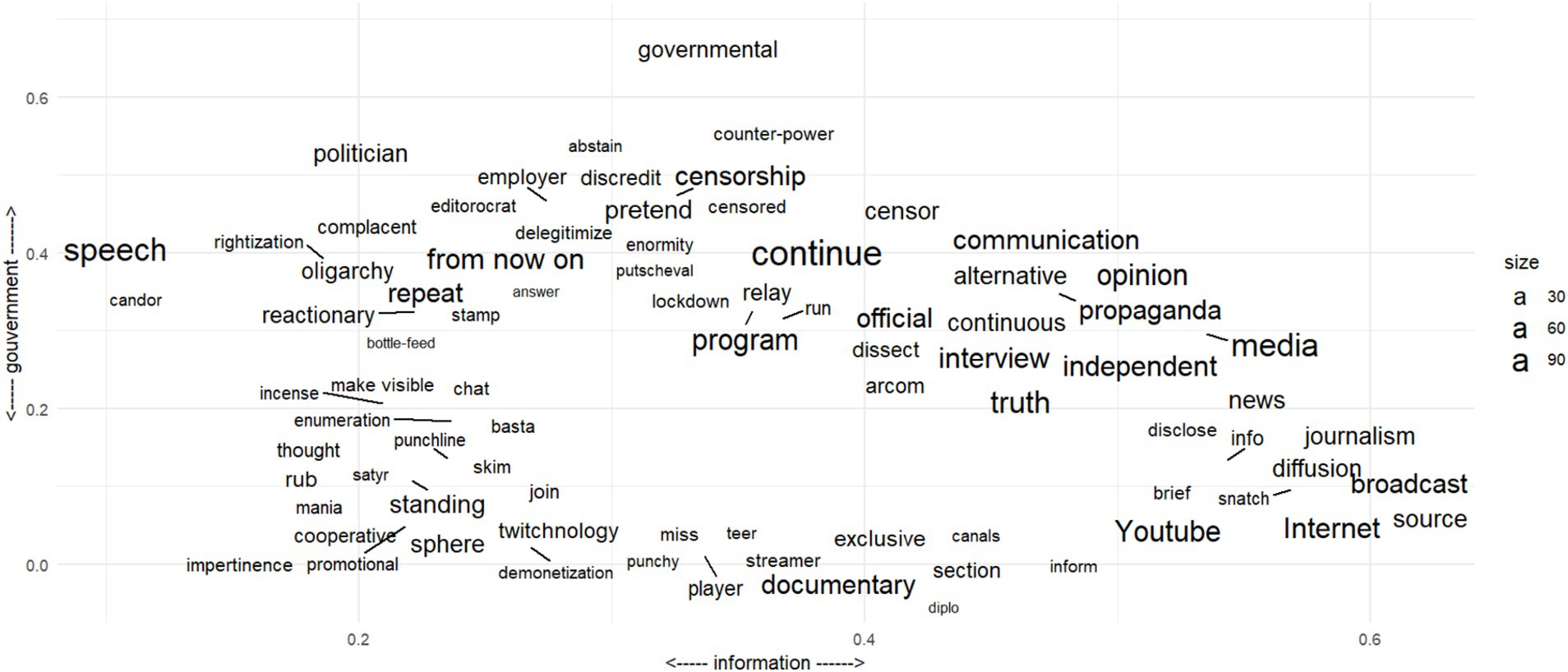

To further evaluate hypothesis 1, we rely on maps of word embedding displaying closely related terms to concepts (see Figures 2, 3) and continuums (see Figure 4). The size of the terms reflects frequency. Figure 2 shows the terms nearest to the word “media” which are also most similar to “information” (x-axis) and “government” (y-axis). Therefore, terms in the top-left corner are strongly related to government and little related to information and include terms such as: “rightization,” “oligarchy,” “editocrat,” “complacent,” “reactionary,” “delegitimize.” In the top-right corner are terms strongly related to government and information. This includes a few terms, among which are: “opinion,” “censor,” “propaganda.” The bottom-right corner includes terms highly connected to information but little related to government. Here we see terms referring to salient information biases and challenges such as: “truth,” “disclose” and “source.” Keeping in mind that the analyzed texts stem from alternative YouTube channels, the interpretation of this word embedding representation suggests that alternative channels depict the government action on information as untransparent, censoring information and manipulating opinion.

Figure 2. Word embedding nearest to “media” with highest cosine similarity to “information” and “government” (terms are translated into English).

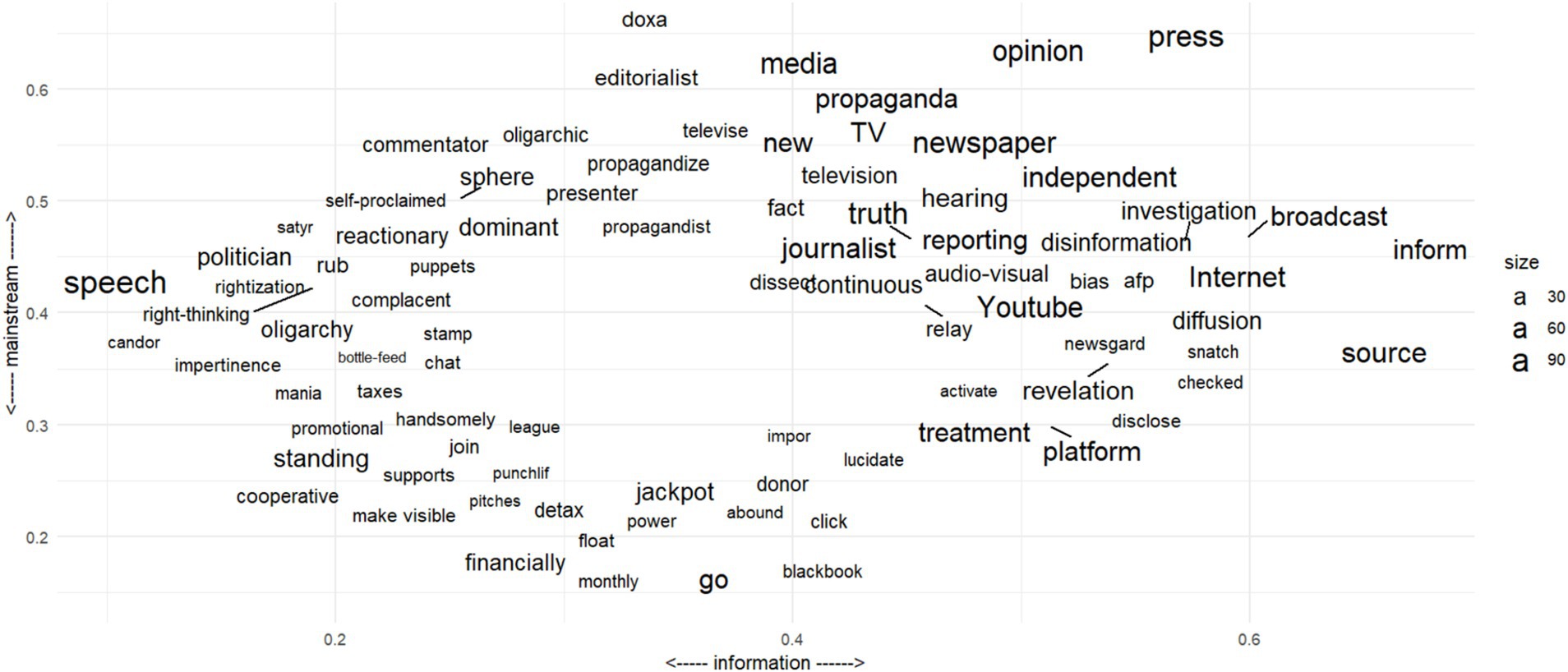

Figure 3. Word embedding nearest to “media” with highest cosine similarity to “information” and “mainstream” (terms are translated into English).

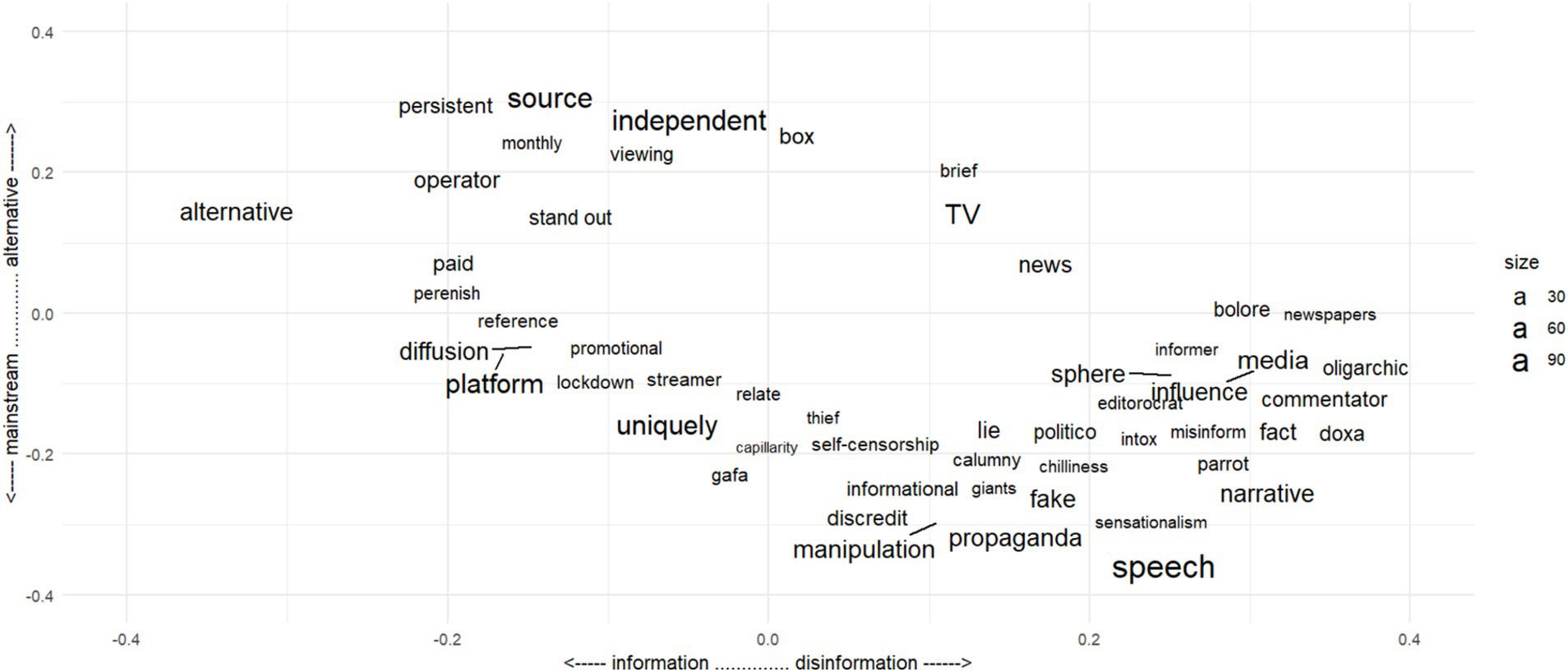

Figure 4. Word embedding nearest to “media” with highest cosine similarity to the continuums “information—disinformation” and “mainstream—alternative” (terms are translated into English).

Figure 3 shows the terms nearest to the word “media” which are also most similar to “information” (x-axis) and “mainstream” (y-axis). Therefore, terms in the top-left corner are strongly related to mainstream media and little related to information and include terms such as: “doxa,” “oligarchy,” “self-proclaimed,” “propagandist,” “puppets.” In the top-right corner are terms strongly related to mainstream media and information. This includes a few terms among which are: “opinion,” “propaganda,” “fact,” “truth.” The bottom-right corner includes terms highly connected to information but little related to mainstream media. Here we see terms referring to information diffusion such as: “broadcast,” “platform,” “source,” “inform.” The interpretation of this word embedding representation suggests that alternative channels portray the mainstream media as being submissive to government (“puppets”) and biased (“doxa”). Mainstream media are also accused of participating to disinforming the opinion and to diffuse propaganda.

Figure 4 displays the terms nearest to “media” which are most similar to the continuums “information–disinformation” (x-axis) and “mainstream–alternative” (y-axis), the size of the terms reflecting their frequency. The second continuum emphasizes the opposition between mainstream and alternative where terms situated on the top refer closely to the alternative media and include terms such as: “independent,” “source,” “persistent.” The terms related to mainstream media are situated at the bottom and include: “self-censorship,” “lockdown,” “gafa.” Figure 4 also shows that most terms related to disinformation are assigned to mainstream media (bottom-right corner) and include: “propaganda,” “manipulation,” “calumny,” “intox,” “parrots,” “puppets.” Interpreting these terms suggests that mainstream media are accused of participating in disinformation both in voluntary and involuntary ways.

Based on these word embedding, we can identify words frequently appearing in the context of criticizing mainstream media and government (see also Annex 2: Figures A1, A2 for further media related terms with respect to the “people” and the “elite”). This list of salient terms form a “critical vocabulary” which includes: “alternative,” “pluralism,” “pluralist,” “billionaire,” “doxa,” “dominant,” “concentration,” “editocrates,” “mediatico,” “verification,” “veracity,” “truth,” “fact,” “facts,” “decomplex,” “decrypt,” “source,” “debunker,” “distill,” “stamp,” “transparency,” “independence,” “self-censorship,” “conspiracy,” “conspire,” “insidous,” “fake,” “incorrect,” “propaganda,” “intox,” toxic,” “slander,” “lie,” “bashing,” “cheater,” “novlang,” “disinformator,” “disinformation,” “misinform,” “mistification,” “puppets,” “parrot,” “satire,” “alarmism,” “hysterize,” “detractor,” “complacent,” “connivance,” “fachosphere,” “arcane,” “slide,” “censorship,” “censor,” “distrust,” “muzzle,” “silence,” “silencing,” “hush,” “oligarchy,” “oligarchic,” “reactionary,” “discredit,” “legitimation,” “self-proclaimed,” “collusion,” “locking,” “manipulation,” “bludgeoning.” Correspondence analysis is conducted to assess what dimensions or continuums are encompassed when relying on these words. To do so, all the videos’ transcripts from each channel are combined into a single document for each channel and a DTM is calculated, where each cell represents the proportion of a word given all the words used by a channel. Each channel is assigned a score reflecting its total reliance on the critical vocabulary.

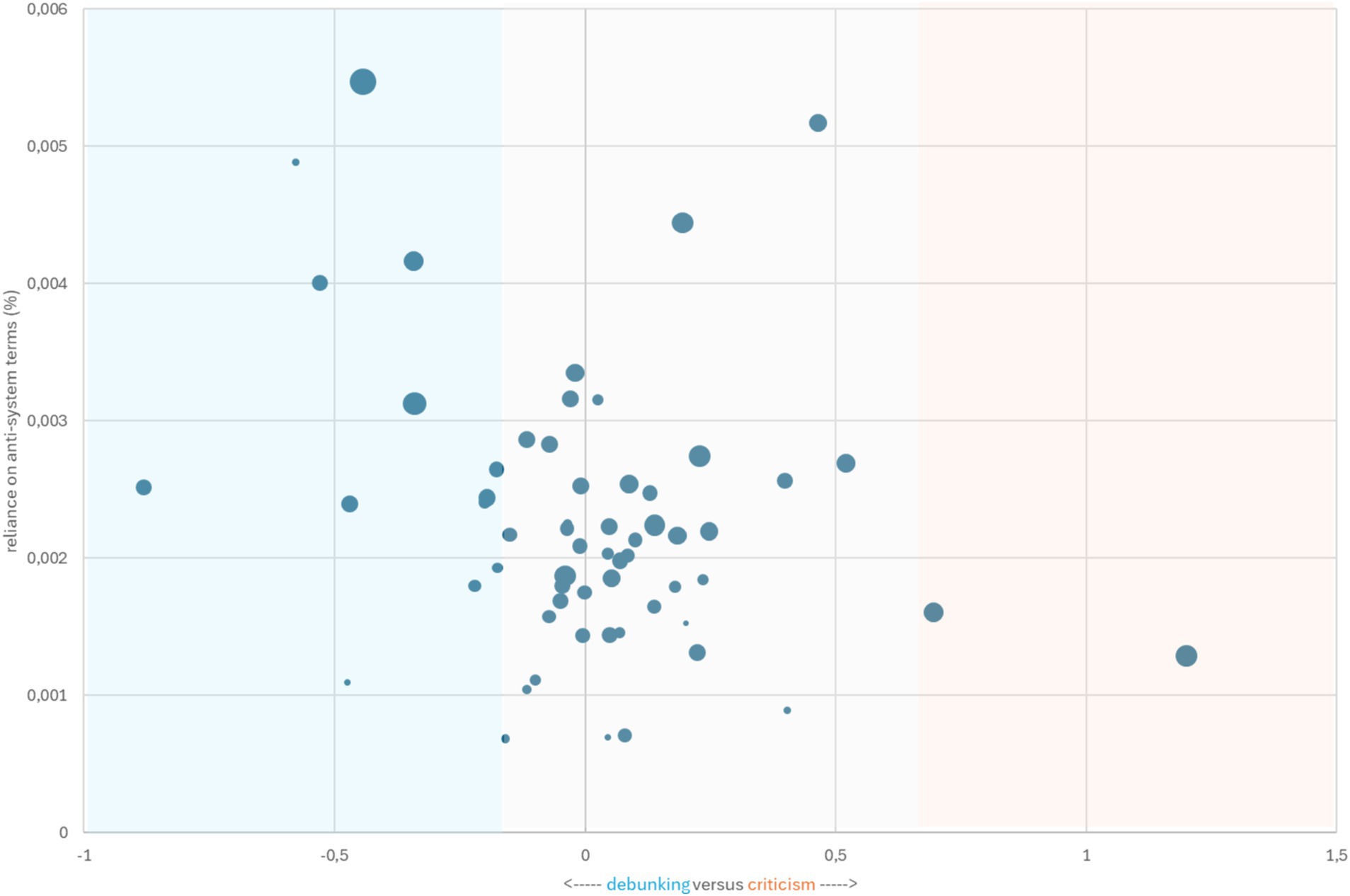

This DTM is transposed with the rows representing the words and the columns representing the channels. Only the words inside the list of salient terms are included in the correspondence analysis. The results (see Annex 3) show a uni-dimensional construct which can be interpreted along a “debunking versus criticism” continuum, where debunking suggests a focus on providing alternative and factual content (e.g., “debunk,” “intox,” “disinformation,” “veracity”) and criticism suggests a focus on criticizing the actions of mainstream media and the government (e.g., “censure,” “oligarchy,” “pluralism,” “bashing”). The coordinates on this continuum can be used to access what is the focus of each channel. A positive score indicates a tendency toward criticism, while a negative score suggests a tendency toward debunking.

The two scores are combined in Figure 5, where the reliance on the critical vocabulary is displayed along the y-axis and the score along the “debunking versus criticism” continuum is displayed along the x-axis. The size of the dots reflects the proportion of words referring to media (including: “journalist(s),” “media,” “press”) and government for each account. Channels vary in their tendency to debunk versus criticize, their reliance on critical language, and their overall focus on government and media topics. For instance, some channels balance high criticism scores with moderate critical language and high focus on mainstream media and government. Other channels emphasize debunking, also showing high critical language usage. Most channels indicate a focused approach on balancing criticism and debunking with a high use of critical language. This can inform viewers or researchers about the likely perspective and content style of each channel. For viewers seeking criticism, some channels provide strong critical content with a high focus on government/media, while others offer content focused more on debunking rather than criticizing.

Figure 5. Categorization of accounts based on a “debunking versus criticism of government and media” score (x-axis), a “reliance on critical words toward government and media” score (y-axis), and a “focus on government and media” score (size of dots).

To test hypothesis 1, which postulates that alternative news channels on YouTube challenge mainstream media and the government, a word2vec model was used to identify the closest terms to “media” in relation to key concepts such as “mainstream,” “information,” “disinformation,” “government,” and “journalist.” The analysis revealed that salient terms frame the mainstream media in terms of “pluralism” and “billionaire,” suggesting criticism of media ownership and diversity. This aligns with subaltern counterpublics theory (Fraser, 1992), especially because these terms reflect a perception that mainstream media lack diversity and are controlled by elite interests, thus excluding voices outside dominant ideologies. In this context, “billionaire” and “pluralism” represent a critique of media ownership, which alternative media channels argue is complicit in upholding the existing power structures by limiting true diversity in media representation. Mainstream media are also associated with “doxa,” indicating a perception of mainstream media as upholding dominant ideologies. This aligns with the alternative media view of themselves as challengers to these mainstream ideologies, framing the mainstream media as reinforcing established power dynamics. This critique resonates with gatekeeping theory, as alternative media claim to break away from the traditional gatekeeping mechanisms that supposedly promote only a narrow range of acceptable discourses. The terms associated with “information” provide a more nuanced picture of how alternative media channels frame their role versus that of mainstream outlets. Positive terms included “factual,” “verification,” “alternative,” and “transparency,” while negative terms like “infobesity” also appeared. This distinction aligns with the theory of subaltern counterpublics, as alternative media channels view themselves as purveyors of truthful information and transparency that counterbalance what they perceive as the oversimplification and excess of the mainstream narrative. “Disinformation” was related to “conspiracy,” “propaganda,” “intox,” and “calumny,” reflecting concerns about misinformation. The associations suggest that alternative channels view mainstream media as active agents in spreading misinformation, a finding that reflects concerns documented in the literature, such as those by Allcott and Gentzkow (2017), on the perceived economic incentives that fuel fake news. These terms support the framing of mainstream media as untrustworthy gatekeepers, a notion that these alternative channels seek to counter by casting themselves as defenders of accuracy and critical thought. Terms related to the government included “muzzle,” “oligarchy,” “distrust,” and “silence,” suggesting a view of the government as suppressive and controlling information. The use of these terms reflects the subaltern counterpublics’ stance on the exclusionary practices of dominant institutions. Government-associated terms like “opinion,” “censure,” and “lie” indicate perceived manipulation of information by the government. This antagonistic framing of the government resonates with the gatekeeping theory by suggesting that both the government and mainstream media act as centralized gatekeepers, filtering information to maintain authority. Alternative media, on the other hand, perceive their role as a countervailing force that subverts these traditional gatekeeping structures by offering uncensored and diverse information. Furthermore, terms like “muzzle,” “oligarchy,” “hysterics,” “dominant,” and “puppets” suggest that mainstream media are viewed as complicit with government agendas and lacking independence. Terms such as “opinion,” “doxa,” “propaganda,” and “conspiracy” imply that mainstream media are seen as disseminating biased and misleading information. This supports previous research by Bennett and Livingston (2018), which highlighted how digital media platforms are reshaping political communication and public perceptions of authority. On the opposite, terms associated with alternative media included “independent,” “safeguard,” and “persistent,” indicating a perceived role in providing diverse and reliable information, thereby contrasting with the terms associated to mainstream media, such as “reactionary,” “censor,” and “denigrate,” that suggest an image of mainstream media as restrictive and disparaging. These findings align with Fraser’s notion of subaltern counterpublics by positioning alternative media as sites of resistance against dominant ideological narratives. They frame themselves as challenging both the restrictive nature of mainstream media and the influence of governmental control over public discourse. Indeed, mainstream media were associated with disinformation terms like “silence,” “poison,” “editocrats,” “parrots,” and “puppets,” suggesting that they are perceived as active participants in spreading misinformation. This finding resonates with Allcott and Gentzkow's (2017) research on the economics of fake news, emphasizing the perceived failure of mainstream media to provide unbiased information, thereby reinforcing the alternative channels’ positioning as authentic and transparent sources of news.

To evaluate hypothesis 2, which suggests that the framing of news by alternative media channels on YouTube contributes to public mistrust in mainstream journalism and the government, a critical vocabulary list was compiled based on the terms mentioned above. Correspondence analysis revealed a “debunking versus criticism” continuum, with channels scoring either toward debunking misinformation or criticizing mainstream media and government actions. While some channels scored high in criticism with moderate critical language and focus on mainstream media and government, others emphasized debunking showing high critical language usage. Channels that emphasize criticism. Channels with a debunking focus prioritize exposing what they perceive as falsehoods or misrepresentations in mainstream media and governmental narratives. These channels often use intense, critical language and explicitly label mainstream narratives as misleading or deceptive. The emphasis on debunking aligns with the theory of gatekeeping, as these channels position themselves as alternative gatekeepers who actively “correct” or counter mainstream narratives. By casting doubt on the reliability of traditional gatekeepers, these channels reinforce a narrative of institutional mistrust and align with Allcott and Gentzkow's (2017) work on the economics of fake news, suggesting that alternative media can heighten public skepticism by presenting themselves as defenders of truth. Furthermore, there are balanced content channels providing a mix of criticism and debunking. These “balanced content” channels combine elements of both strategies, challenging mainstream media and government narratives by offering critical analysis while also seeking to “debunk” specific claims or stories. This mix reflects a hybrid approach to gatekeeping, where these channels provide spaces for contested narratives and act as intermediaries that blend criticism with correction. By engaging in both debunking and criticism, these channels reinforce their role as alternative information sources that fulfill the public’s perceived need for transparency and accountability—qualities they claim mainstream outlets lack.

The findings of this study contribute to the theoretical adaptation of gatekeeping theory by highlighting how non-journalistic actors, such as YouTube alternative media channels, influence the flow of information. Traditional gatekeeping roles, as described by Shoemaker and Vos (2009) and expanded by Thorson and Wells (2016), are increasingly decentralized in the digital media landscape, with information dissemination now controlled by a diverse array of actors. This study reveals how alternative media channels act as new gatekeepers, framing mainstream media and government in ways that reflect public distrust and cynicism. By frequently associating terms such as “propaganda,” “conspiracy,” and “disinformation” with mainstream media, these channels reinforce an adversarial stance that challenges the credibility of traditional journalism and government institutions (Lewis, 2018). This supports Fuchs (2021) argument that digital platforms are reshaping public perceptions and contributing to the erosion of trust in established authorities. By positioning themselves as correctives to perceived bias and misinformation, alternative media channels amplify skeptical narratives, which in turn influence public attitudes toward legacy media and political authorities.

Second, the study provides evidence that alternative media channels may contribute to the polarization of public discourse. The critical vocabulary analysis uncovered terms such as “doxa,” “dominant,” “puppets,” and “propaganda,” which suggest that mainstream media are viewed as tools of elite control and disseminators of biased information. This aligns with research by Nocun and Lamberty (2020), which demonstrates how social media platforms can intensify societal divides by facilitating the spread of misinformation. The polarized framing is further reflected in terms such as “censure,” “oligarchy,” and “hysterics,” which underscore a narrative of conflict and opposition. Such language not only positions mainstream media and government as adversaries but also creates a sense of in-group solidarity among viewers who feel disenfranchised by traditional media. This divisive rhetoric may deepen ideological divides within the public sphere, contributing to an increasingly polarized media landscape.

Finally, the identification of a “debunking versus criticism” continuum within the discourse of alternative media channels suggests that these channels fulfill diverse roles within the information ecosystem. The continuum highlights a spectrum where some channels focus primarily on debunking misinformation and delivering factual content, while others emphasize direct criticism of mainstream media and government actions. This reflects a multifaceted approach to gatekeeping, where channels simultaneously serve as sources of information and as critics of dominant institutions (Rauchfleisch and Kaiser, 2020). By catering to a range of viewer preferences—whether for debunking, criticism, or a combination of both—alternative media channels illustrate the complexity of their impact on public discourse. They can function both as purveyors of factual information and as active participants in ideological critique, thereby blurring the lines between information dissemination and opinion-based commentary.

Despite the valuable insights provided, this study has several limitations. First, while the study employs word2vec models and word embedding to analyze the discourse of alternative media channels, these models inherently rely on term frequency and co-occurrence, which may overlook context-specific meanings, such as irony or sarcasm, embedded within a cultural and social framework. To address this, future research could benefit from a stratified qualitative analysis of specific clusters, examining representative segments of video content within each cluster to better understand the contextual nuances behind the terms identified in the embedding. This approach would allow for a more interpretive lens, adding depth to the labeling of each cluster and enhancing our understanding of the socio-cultural context of these narratives.

Additionally, the study focuses solely on YouTube transcripts, which may not capture the full breadth of alternative media content, as platforms such as blogs, social media posts, and podcasts were not included. This platform-specific focus may limit the representativeness of the findings, as alternative media channels frequently distribute content across multiple platforms to reach diverse audiences. Future studies could improve representativeness by integrating data from a wider range of platforms.

Furthermore, the analysis is limited to the French media system and content in French, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other cultural and linguistic contexts. To address this, a comparative approach that includes multiple languages and countries could provide insights into the global dynamics of alternative media discourse. This study further provides a snapshot for a single year, namely 2023. Future research could employ a longitudinal approach to observe how the framing and positioning of these channels evolve in response to political or societal shifts over time. Tracking changes in the discourse network over multiple years may reveal trends or shifts in the relationships between clusters, adding to our theoretical understanding of the alternative media ecosystem. Additionally, the analysis of editorial choices and audience interactions, such as comment patterns, could shed light on how user engagement influences content production and narrative direction.

Finally, the correspondence analysis reveals a clustering of channels based on their critical vocabulary usage, yet this study does not fully explore the connections and distinctions within these clusters. Integrating network analysis techniques, such as centrality measures, could allow future research to examine the similarities and dissimilarities within and across clusters, potentially uncovering factional structures within the alternative media landscape. For example, by exploring connections between channels based on shared vocabulary or thematic overlaps, researchers could investigate whether distinct factions exist both within alternative media and between alternative and legacy media. Such an approach would offer a more comprehensive view of the relationships among these channels and how they may collectively interact within YouTube’s recommendation ecosystem.

In conclusion, the study provides important insights into how alternative media channels on YouTube engage in discourse that challenges mainstream media and the government. These channels play a significant role in shaping public perceptions, contributing to both informed skepticism and potential distrust. The study offer insights about whether these channels represent a radical detachment from legacy media or a reconfiguration within the hybrid media system. Rather than fully detaching from traditional frameworks, these channels adapt, resist, and respond to legacy media’s established narratives, presenting themselves as challengers through critique and correction. This indicates that alternative media strategically position themselves within the hybrid media system to contest dominant narratives.

The findings emphasize the diverse characteristics of gatekeepers in alternative media, who are not traditional journalists but rather individuals or teams leveraging skills in critical analysis, debunking, and audience engagement. This underscores the varied capacities in which alternative gatekeepers operate, from citizen journalists to organized groups with different levels of expertise in digital media literacy or investigative practices. These varied profiles suggest a more nuanced understanding of the gatekeeping function, wherein skillsets, resources, and motivations differ significantly among alternative media actors.

The study’s limitations highlight the need for continued research to fully understand the evolving media landscape and the complex interplay between distinct types of media and alternative public discourse. In addressing the objective of whether these channels represent a detachment or reconfiguration, the results reveal a hybrid dynamic: while they criticize and resist legacy media, they also draw on its frameworks to construct counter-narratives. This interplay suggests that alternative media act as both challengers to and participants in the broader media ecosystem.

The implications of the study suggest that the role of alternative media in shaping public perceptions of authority is complex and multifaceted. As these channels continue to grow in influence, they contribute not only to public mistrust of mainstream media and government but also to the broader reconfiguration of the media landscape, where audiences are increasingly drawn to sources that offer alternative framings and critiques of established institutions. Future studies might further explore the skillsets and practices employed by these alternative gatekeepers to provide deeper insights into their influence and effectiveness in countering traditional gatekeeping models.

The raw data (such as video identifiers) supporting the conclusions of the article can be made available by the authors upon request.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform’s terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

MR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CN: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Open Access costs were financed by University Library Zurich.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1517963/full#supplementary-material

Allcott, H., and Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. J. Econ. Perspect. 31, 211–236. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Bennett, W. L., and Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. Eur. J. Commun. 33, 122–139. doi: 10.1177/0267323118760317

Croix, La. (2023). Confiance dans les médias: notre baromètre en 8 chiffres. Available at: https://www.la-croix.com/economie/Confiance-medias-notre-barometre-8-chiffres-2023-11-22-1201291750 (Accessed October 15, 2014)

Diplomatique, M. (2023). Médias français, qui possède quoi?. Available at: https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/cartes/PPA (Accessed December, 2024).

Eisenegger, M. (2020). “Dritter, digitaler Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit als Folge der Plattformisierung” in Digitaler Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Historische Verortung, Modelle und Konsequenzen. eds. M. Eisenegger, M. Prinzing, R. Blum, and P. Ettinger (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 17–38.

Figenschou, T. U., and Ihlebæk, K. A. (2018). Challenging journalistic authority: media criticism in far-right alternative media. J. Stud. 20, 1221–1237. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2018.1500868

Fraser, N. (1992). “Rethinking the public sphere: a contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy” in Habermas and the Public Sphere. ed. C. Calhoun (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 109–142.

Fuchs, C. (2021). The digital commons and the digital public sphere: How to advance digital democracy today. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 16. doi: 10.16997/wpcc.917

Habermas, J. (1962). Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit; Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellscahft. Neuwied: H. Luchterhand.

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hameleers, M., and Yekta, N. (2023). Entering an information era of parallel truths? A qualitative analysis of legitimizing and De-legitimizing truth claims in established versus alternative media outlets. Commun. Res. 1:00936502231189685. doi: 10.1177/00936502231189685

Harcup, T. (2003). The unspoken-Said' the journalism of alternative media. Journalism 4, 356–376. doi: 10.1177/14648849030043006

Holt, K., Figenschou, T. U., and Frischlich, L. (2019). Key dimensions of alternative news media. Digit. J. 7, 860–869. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2019.1625715

Humprecht, E., and Esser, F. (2018). Diversity in online news. J. Stud. 19, 1825–1847. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1308229

Lewis, R. (2018). Alternative influence: Broadcasting the reactionary right on YouTube : Data & Society Research Institute.

Lyubareva, I., Mésangeau, J., Boudjani, N., El Badisy, I., and Brisson, L. (2021). La plateformisation des médias français et le ton du débat public. Revue Commun 38, 1–29. doi: 10.4000/communication.14433

Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G., and Dean, J. (2013). Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv:1301.3781. preprint

Neuberger, C., Nuernbergk, C., and Rischke, M. (2009). Journalismus im Internet: Zwischen Profession, Partizipation und Technik. Media Perspektiven 4, 174–188.

Nocun, K., and Lamberty, P. (2020). Fake Facts: Wie Verschw Örungstheorien unser Denken bestimmen. Köln, DE: Bastei Lübbe AG.

Rauchfleisch, A., and Kaiser, J. (2020). The German far-right on YouTube: An analysis of user overlap and user comments. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media. 64, 373–396. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2020.1799690

Reveilhac, M. (2024). YouTube as an information source on politics and current affairs: supply- and demand-side perspectives. First Monday 29, 1–12. doi: 10.5210/fm.v29i7.13633

Reveilhac, M., and Blanchard, A. (2022). The framing of health technologies on social media by major actors: prominent health issues and COVID-related public concerns. Int. J. Inform. Manage. Data Insights 2:100068. doi: 10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100068

Ribeiro, M. H., Ottoni, R., West, R., Almeida, V. A., and Meira, W. (2020). Auditing radicalization pathways on YouTube. In Proceedings of the 2020 conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency. arXiv:1908.08313v4.

Röchert, D., Neubaum, G., Ross, B., and Stieglitz, S. (2022). Caught in a networked collusion? Homogeneity in conspiracy-related discussion networks on YouTube. Inf. Syst. 103:101866. doi: 10.1016/j.is.2021.101866

Ruellan, D. (2007). Le journalisme ou le professionnalisme du flou. Grenoble: Presses de l’Université de Grenoble.

Sahlgren, M., and Lenci, A. (2016). The effects of data size and frequency range on distributional semantic models (Accessed January, 2024).

Schmidt, B. (2017). Word vectors. An R package for building and exploring word embedding models. Available at: https://github.com/bmschmidt/wordVectors (Accessed January, 2024).

Schwaiger, L. (2022). “Gegen die Öffentlichkeit. Alternative Nachrichtenmedien im deutschsprachigen Raum. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript.

Schwaiger, L., and Eisenegger, M. (2021). “Die Rahmung von Wahrheit und Lüge in Online-Gegenöffentlichkeiten–Eine netzwerkanalytische Untersuchung auf Twitter” in Medien und Wahrheit (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG), 359–376.

Schweiger, W. (2017). “Nachrichtenjournalismus, alternative und soziale Medien” in Der (des)informierte Bürger im Netz. ed. Wolfgang Schweiger (Wiesbaden: Springer), 27–68.

Thorson, K., and Wells, C. (2016). Curated flows: a framework for mapping media exposure in the digital age. Commun. Theory 26, 309–328. doi: 10.1111/comt.12087

Keywords: alternative media, gatekeeping theory, subaltern counterpublics, YouTube, word embedding

Citation: Reveilhac M and Nchakga C (2025) How French alternative media channels on YouTube portray the government and mainstream media on YouTube. Front. Commun. 9:1517963. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1517963

Received: 27 October 2024; Accepted: 17 December 2024;

Published: 13 January 2025.

Edited by:

Elsa Costa E. Silva, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Christian Ruggiero, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Reveilhac and Nchakga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maud Reveilhac, bS5yZXZlaWxoYWNAaWttei51emguY2g=

†ORCID: Maud Reveilhac, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9769-6830

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.