95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 16 January 2025

Sec. Multimodality of Communication

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1517858

This article is part of the Research Topic The Interplay of Interactional Space and Multimodal Instructions in Teaching Contexts View all 4 articles

This paper explores the co-construction of ‘Activity Spaces’ within weekly rehearsals of an amateur, mixed-level dance company. Data are taken from field notes, participant observation experience, and video recordings. An earlier analysis identified three canonical spatial divisions that participants co-create during ballet rehearsals: the ‘Dancing Space’, the ‘Teaching Space’, and the ‘Peripheries’. The present study shows that these Activity Spaces are not demarcated physically but are instead entirely co-constructed through participants’ own multi-modal actions within the rehearsals. An important aspect of this co-construction are the participation roles dancer, choreographer, participants not currently dancing. Participants’ contributions to activities are in part negotiated through their turn design and their positioning within and across Activity Spaces. The analysis focuses in on the ‘Teaching Space’, how it is assigned meaning within the group, and how it is reconfigured according to participants’ needs through their mobilisation of multi-modal resources. Of special interest are moments in which a member takes up or relinquishes a teaching/choreographing role. Features given attention include bodily orientations, such as dancers’ positioning of themselves to have visual access to the choreographer; prosodic features, such as choreographers’ use of raised volume relative to surrounding interaction; and verbal contributions from the choreographer and from dancing and currently-not-dancing participants. Data are in English.

This paper explores the co-construction of ‘Activity Spaces’ within weekly rehearsals of an amateur, mixed-level dance company. Dance instruction has been the focus of a number of interaction-oriented studies, including Kelly (1999), e.g., Keevallik (2010, 2013, 2015, 2021), Douglah (2020, 2021), Ehmer (2021, 2023), and Reed (2025). While these have focused on dance lessons in the disciplines line dancing (Kelly), Lindy Hop (Keevallik), show dance (Douglah), Tango (Ehmer, Reed), and Waltz (Reed), the present contribution examines instructional interaction during rehearsals rather than lessons and in the discipline of ballet. Utilising a mixed-method approach of ethnographic participant observation alongside multi-modal Conversation Analysis, the research provides a textured, multi-scale analysis of participants’ (dancers’, choreographers’) interactional co-construction of zones in the rehearsal space in which space is coupled with types of activity. In examining participants’ co-construction of space, the paper takes as a focal site Richmond Ballet, an amateur dance company based in London. The group meets weekly for three-hour sessions in a purpose-built studio within a performing arts college and work towards an annual, public final performance, in which several pieces are performed. Data are taken from field notes, participant observation experience, and video recordings of these weekly rehearsals, in which members alternate to take charge of a particular dance and where, consequently, there is no one ‘leading’ member across an evening.

The paper will first outline three canonical spatial divisions that participants co-create during ballet rehearsals: the ‘Dancing Space’, the ‘Teaching Space’, and the ‘Peripheries’ (Smart, 2025). Emphasis is given to the finding that these Activity Spaces are not demarcated in any physical way or using any tangible borders but are instead entirely co-constructed through participants’ own multi-modal actions and turn design within the rehearsals. An important aspect of this co-construction are the participation roles dancer, choreographer, and members not currently dancing. Participants’ contributions to activities are in part negotiated through their positioning within and across Activity Spaces. The analysis then considers the ‘Teaching Space’, how it is assigned meaning within the group, and how it is reconfigured according to participants’ needs through their mobilisation of multi-modal resources. Particular foci considered through attention to individual episodes include practices for the co-construction of space, transition of role for instructors, turn design in preparation for instructional activity in order to ensure visibility, and flexible use of spatial boundaries in accordance with the purpose and temporality of particular activities during rehearsals. Our concept of ‘activity’ is of an interactional unit or ‘domain’ (Mazeland, 2019) that consists of ‘multiple, normatively ordered sequences of action’ (Robinson, 2012, p. 257) with an overarching topical or goal-oriented coherence (Heritage and Sorjonen, 1994). Robinson (2012) distinguishes between activities and projects, the latter having ‘an overall structural organisation that involves multiple, ordered … activities’ (p. 267). In our analysis, we treat the entire three-hour session as the interactional project, and individual components, such as run-throughs or rehearsals of specific parts, as activities. The typical ordering of activities in Richmond Ballet sessions is as follows: a general warm-up class led by one member, then three to four rehearsals of individual pieces for later performance. These rehearsals comprise of practicings—in which new sections are taught and trouble sources revisited and clarified for polishing—and run-throughs, where a piece is completed with the music and without pausing. Run-throughs are typically followed by a practicing, in which the instructor gives feedback relating to specific moments in the piece and dancers work to refine these. The order of pieces being rehearsed in a given session is circulated in advance to members via WhatsApp, and alters each week (despite these being for the same three or four pieces for the entirety of the year).

The paper contributes to the growing body of interaction-oriented research on embodied skills instruction (Ehmer and Brône, 2021) in group settings. More specifically, it contributes to an understanding of space as a social construct and resource in embodied instruction. In studies of naturally occurring interaction, space has been shown to be a ‘social phenomenon’ that is ‘locally accomplished’ (McIlvenny et al., 2009, p. 1881, emphasis in the original). Hausendorf (2013) uses the term ‘situational anchoring’ to conceptualise the joint achievement of ‘a mutually shared “here”’ (p. 277; see also Hausendorf, 2010). Resources for co-constructing interactional space can be verbal, such as place references (Schegloff, 1972) and deixis (Auer and Stukenbrock, 2022), but also embodied. For example, Mondada (2009) shows how strangers asking others for directions ‘organise their spatial approach’ (p. 1983) by seeking mutual gaze and gradually slowing down their walk, amongst other practices. As these not-yet-interactants coordinate their embodied actions and gradually establish a mutual orientation, they co-create what Mondada calls an ‘interactional space’ (Mondada, 2013), a term that refers ‘both to an interactional conceptualisation of space and to a spatial conceptualisation of interaction’ (ibid.: 250, emphasis in the original). Arguably, research in this area has tended to emphasise the second, that is, the study of interactional phenomena as situated in jointly accomplished spaces, rather than the jointly accomplished spaces themselves (but see, for example, Noy, 2012; Smith, 2017). The co-construction of interactional spaces can be most clearly observed at their boundaries, for example, during conversational opening, joining, or closing sequences (e.g., Mondada, 2009; Broth and Mondada, 2013; Harjunpää et al., 2018; Tuncer, 2018) or in settings where participants necessarily move from one location to another, such as on guided tours (e.g., Mondada, 2013; Best and Hindmarsh, 2019). An important resource in this regard is what Hausendorf and Schmitt (2022) call ‘architecture-for-interaction’, that is, any pre-structured built environment that ‘enables and suggests social interaction, albeit without having the ability to determine or forestall what will take place’ (p. 441). Architecture (understood broadly) is seen as providing cues for how buildings and other structures can be used, which may—but does not have to—impact on how participants co-construct such spaces.

Few conversation analytic studies have considered the use of space as an interactional resource in instruction settings. Among those that have done so, there is a focus on space as a way of providing individualised opportunities for learning within larger group settings. Lundesjö Kvart (2020) draws on Mondada’s concept of interactional space for her related notion of ‘instructional space’ in a study of group horse-riding lessons. Riding teachers and students together create instructional spaces for the purpose of brief individual (i.e., non-group) interactions among the constantly moving horse-rider pairs. As horse-rider pairs pass by the instructor, both parties are physically close enough to engage in brief one-to-one interactions. Teachers co-create this instructional space by addressing riders by name, giving them individualised directives, and speaking in a quieter voice than when they are addressing the whole group. Instructions and instructed actions are done to fit the temporal window of the instructional space, that is, the short time that teacher and learner are within close proximity (see also Hall, 1966).

Lundesjö Kvart’s (2020) analysis shows learners moving into teachers’ spaces for an opportunity to receive instruction. Here, teachers are quasi-immobile, while learners are on the move. In contrast, Reed and Szczepek Reed’s (2013) analysis of music masterclasses shows teachers moving into learners’ spaces to create learning opportunities. In the sequential organisation of slots for instruction and performance, masters’ entering and retreating from the stage co-constructs the opening and closing of their instruction slot and—simultaneously—the closing of students’ previous performance slot (master entering the stage) and the initiation of the next one (master retreating). Similarly, Jakonen (2020) describes teachers entering into learners’ spaces in a study of classroom interaction. Teachers who make their rounds while students are working independently walk from one desk to another to assess students’ progress and display availability for individual instruction. Their bodily actions and orientations co-construct these sequences from (pre-)openings (by leaning in) to closing (by walking away). This finding is reminiscent of the embodied shaping of the classroom floor when teachers physically leave and then resume teaching activities (Macbeth, 1992). In another study on classroom interaction, Batlle Rodríguez and Evnitskaya (2024) describe teachers moving out of spaces they previously occupied to create learning opportunities. The authors find that teachers in Spanish-as-a-foreign-language classrooms use a combination of gaze, pointing, and stepping back to give students space to engage in peer repair sequences. By stepping away, teachers are argued to leave their ‘“authoritative” position’ (p. 303), ‘delegate the responsibility for repair work’ (p. 317), and give students the chance to ‘renegotiate … the participation framework’ (ibid.). The spaces that teachers are navigating are thus conceptualised as epistemic as well as physical positions and teachers’ departure from them as temporary departures from their epistemic positioning as well as from the interaction itself. A similar practice is reported in Veronesi’s (2007) study of university lecturers’ movements in front of a class. Veronesi emphasises proxemics, noting a connection between interactional and physical proximity as lecturers stand near students when they are closely engaged in discussion with them but step away when two students are interacting exclusively with each other (ibid.: 119–125). Further, in a recent microanalytic study of a single lecturer’s pacing up and down in front of her students, Reed et al. (2024) understand the lecturer’s walking behaviour as ‘[constituting] the spatial arrangements’ of the lecture. Using dance as a lens to understand the lecturer’s footwork, figures, and rhythms, these are shown to be oriented to the instructional activity of lecturing and its spatial accomplishment. Finally, Hausendorf and Schmitt (2022) demonstrate their concept of ‘architecture-for-interaction’ (see above) with an example of students’ gradual arrival in a lecture hall. The students ‘follow the built-in affordances for walk-on-ability’ (p. 450) by treating the pre-existing structure of the room as guiding cue, for example, for where to go and who to interact with, or not. The study shows that pre-structured space can shape interaction as much as interaction can co-construct space.

The present study contributes to this body of work by showing how ballet dancers and choreographers use multi-modal resources to co-construct and negotiate instruction-relevant spaces during rehearsal. Specifically, the analysis focuses on resources such as turn design (lexical, prosodic, embodied), relocations from one place to another, and the manipulation of objects to show the interactional construction of the Teaching Space as a space that has flexible and locally emergent boundaries.

The data for this project were video recorded sessions of an amateur dance company, filmed across a period of 6 months from January to July of 2023. The field site is Richmond Ballet (anonymised), based in London, UK, who meet each Thursday for 3 h of rehearsals towards an annual performance. The company was founded in 1967 and is currently made up of 26 members of varying abilities, with the ages of members ranging from mid-twenties to mid-eighties. The full data corpus comprises 31 h of video footage taken from 12 rehearsal sessions, with cameras positioned at the front and back of the hired studio space to capture as much natural data as possible throughout the evening. In addition to the video data, one of the authors underwent a period of ethnographic participant observation with Richmond Ballet, building on a prior membership of 6 years with the company through continued involvement as well as the creation of reflective field notes after sessions. All participants gave their permission to be both recorded and observed in line with this study, and all names and faces have been anonymised in accordance with this.

The project adopts a multi-scalar approach to analysis, which entails engaging with ethnographic participant observation across the scale of months; and employing multimodal Conversation Analysis at a closer, micro-analytic scale. The combined findings of both methods, drawing on a shared theoretical stance of social constructionism, facilitate an investigation of Richmond Ballet that is both long-term (findings from 6 months’ worth of observation) and micro analytic in nature. Ethnographic Participant Observation (Hammersley and Atkinson, 2019, p. 4) was employed to gain an understanding, from within the group, of the norms and routines of members as well as how they organise themselves throughout the year. The findings of this participatory method informed the selection of the central phenomena—the co-construction of a Teaching Space—for closer attention.

Following a period of repeated viewing of the video recordings, particular moments were selected for closer analytic attention. Episodes were selected which foregrounded the interactional achievement of the Teaching Space as a distinct zone, either at the beginning of a rehearsal when a member took on an instructing role or demonstrating a negotiation of altered boundaries. A process of multimodal Conversation Analysis was then employed in the creation of transcripts and analysis of phenomena of interest. Contributing to an ever-expanding body of work in multimodal analysis (Streeck et al., 2011; Mondada, 2019a), the project follows the Conversation Analysis tradition (Schegloff, 2007), privileging sequentiality and facilitating close attention to the moment by moment unfolding of interaction as it naturally occurred within the field site. The transcript notations are inspired by Mondada (2019b) for embodied actions and by Selting et al. (2009) for prosodic features. To keep transcripts to a manageable length, intonation units are not shown as individual lines in the transcript. Intonation unit boundaries are indicated only by the punctuation marks that mark phrase-final pitch. Based on these conventions, the notations were adapted to deal with the specific context of the Richmond Ballet rehearsals as well as the nature of this amateur company as a physical craft group, for whom movement and embodied action is central.

In employing these approaches together in tandem, the present analysis is able to gain a picture of the field site across multiple timescales, with findings operating on the close, micro-analytic scale as well as the broader timescale of months throughout the company’s year.

Within the hired studio space used weekly by this amateur dance group, an earlier ethnographic study (Smart, 2025) identified three distinct areas or zones with participant-created normative divisions. Rather than being marked out by physical boundaries, these zones are defined by group members’ own actions, orienting to these spaces as sites of particular activities such that these areas—or Activity Spaces—are co-constructed across the course of the rehearsal sessions. The three Activity Spaces are briefly introduced here; a more in-depth analysis can be found in Smart (2025). In addition to the interactional achievement of these Activity Spaces, the purpose-built studio houses certain artefacts and affordances which contribute to their normative arrangement, serving as ‘cues’ (Hausendorf and Schmitt, 2022, p. 465). These include, for example, the mirrored wall used as the ‘front’ for the dancing group, enabling them to see themselves during sessions (see Figure 1, below). These aspects of the ‘built and furnished space’ (Hausendorf and Jucker, 2022, p. 11) shape participants’ decisions and normative arrangements, with aspects such as the studio’s mirrored wall and open centre (with no furnishings or obstructions) being already ‘prepared and arranged’ (p. 11) for particular activities—namely, dance rehearsal.

Across the data corpus these Activity Spaces were identified as standardised, normative zones for particular types of activities such that space and activity were here coupled. The basis for this theorisation of Activity Spaces is Goodwin’s ‘Situated Activity’ (2003, p. 9), which noted that participants oriented to particular spaces as a ‘shared focus for the organisation of cognition and action’ (Goodwin, 2003, p. 2). In the present study, particular spaces became regular zones for activity/ies related to the group’s shared craft of dance and goals of a final cohesive performance within and throughout rehearsals.

The data corpus revealed three distinct Activity Spaces co-constructed by members’ (inter)actions throughout Richmond Ballet rehearsals and re-constructed week after week to become normative over the years. These spaces have been labelled the Dancing Space, Teaching Space, and Peripheries. Whilst this paper focuses on the construction of the Teaching Space specifically, these spaces do not exist in isolation and, instead, are positioned relative to one another. Consequently, an outline of each is here given.

The Dancing Space (DS) is the largest of the three Activity Spaces and takes up the centre of the studio. It is here that dancing activity takes place during the rehearsals, with the practicing and running of pieces with music occurring in this area. Members move into this space when a dance they are cast in is announced for rehearsal, entering from, for example, the Peripheries, or remaining in the space if they were also involved in the previous rehearsal. Those no longer needed in the upcoming rehearsal slot—for example, those who are not cast—leave this space during this period of crossover, with their removal further positioning this Activity Space as a site for dancing activity.

The Peripheries are made up of a thin strip around the studio’s walls, extending about two feet away from the ballet barres that line each one. Members of Richmond Ballet place their personal possessions here upon entering the studio at the beginning of sessions and return here to retrieve any items they may need throughout the evening, including water bottles, pointe shoes, and props. When not actively involved in the piece being rehearsed, group members typically sat or stood here and either stretched, watched the ongoing rehearsal, engaged in social conversation with fellow members, or in a combination of these activities.

With this overview in place, discussion can now turn to the central matter of this paper: the construction of the Teaching Space as a zone for instructional activity. Beginning with a description of the normative arrangements of this Activity Space, we will first provide a contextual background before looking to the ways members continually position this space as a site of instruction, considering instructors’ turn design as well as the flexible and emergent nature of the space and its boundaries.

A thin strip across the wall designated the ‘front’, the Teaching Space (TS) is directly in front of a floor-to-ceiling mirrored wall. It is in this space that instructors stand, facing and teaching dancers from here. The Teaching Space offers the broadest view of all dancers in the Dancing Space, and, furthermore, provides a good place from which to film a particular dance as a guide, with this footage then being circulated to all members involved via social media. It is this space that is the focus of this paper, and the co-construction of this zone will be discussed in greater detail in the coming analysis.

As discussed, during the rehearsal of a particular piece the instructor-choreographer typically stands in the centre of the Teaching Space at the front of the room, facing the dancing members in the Dancing Space. This bodily-spatial arrangement, which is a ‘mobile formation’ (McIlvenny et al., 2014) or ‘F-Formation’ (Kendon, 1990, pp. 209–238), is mutually beneficial; not only providing an effective view of dancing members for the instructor, but also being the position from which most cast members are able to see the instructor. In these moments, a particular spatial dyad of Instructor/Learner is created, with members adopting these roles orienting their bodies spatially such that they are in this configuration, with learning cast members facing their instructor (Figure 2).

Instructing members largely remained facing their cast dancers throughout rehearsal sessions or ‘mirrored’ dance movements—that is, executing the same steps with the opposite limb—to enable them to continue watching from this vantage point as they guide their learners. Mirroring here refers to an activity by the instructor rather than the learners, who have often been described as ‘mirroring’ teachers’ body movements in embodied instruction settings (see Ivaldi et al., 2021, p. 8). By mirroring dancers’ movements in reverse, instructors were able to “check” or observe their learners, offering assessment or feedback where relevant. On occasion, however, instructors turned to face the same direction as their dancers and execute the steps in the same bodily orientation. Whilst the bodily orientation of the instructor altered in these moments, the spatial boundaries remained intact, with the instructor remaining in front of the dancers and visible to all.

The mirrored wall became a valuable resource in these moments, enabling instructors to demonstrate movement sequences in the target bodily orientation whilst still monitoring learners’ actions. The use of mirrors as an instructional resource in dance classes is widely recognised, with Douglah describing instances of ‘demonstration’ in dance class with instructors facing the same direction as students (Douglah, 2020). During these instances, dancers were able to ‘use the mirror both to see themselves and also to see T’s demonstration’ (T being the Teacher) (Douglah, 2020, p. 15), and furthermore, in facing the mirror the teacher is ‘provided the chance to use the mirror as a tool while demonstrating’ (Douglah, 2020, p. 15). This was visible within the focal context of this paper through instructors’ gaze patterns as they observed cast members in the mirror and provided feedback based on their observations here.

This normative spatial arrangement, with the Teaching and Dancing Spaces distinct and relational as shown in the diagram and images, was the most frequent spatial organisation throughout rehearsals in the data corpus. However, the instructor and learner roles within Richmond Ballet were highly flexible, as the three-hour rehearsing sessions were split into smaller segments of between 30 and 40 min, in each of which a different member was called upon to take up the instructor-choreographer role and develop their piece. This order was pre-determined and circulated each week, and during the sessions a fellow member would call upon the next member to take up their role as instructor. With each piece having a different instructor-choreographer, then, the moments of transition between rehearsal segments (and, consequently, between instructing members) becomes relevant for consideration of the co-construction of the Teaching Space as a zone for instructing activity.

We now turn to the specific practices that Richmond Ballet members employ in their co-construction of the Teaching Space. We focus, first, on the instructor’s turn design as they enter the Teaching Space and prepare for instruction; and, second, on participants’ flexible treatment of Teaching Space boundaries as they fit the space to their local activities and requirements.

Throughout the data corpus, there were several episodes in which instructors’ turns were designed to hold the floor until they had physically reached the Teaching Space at the beginning of their rehearsal slot. In this way, instructing members constructed the Teaching Space through their turn design as the particular zone for instruction, holding off from delivering physical, actionable instruction until situated in this Activity Space. This section will consider two examples of this pattern of turn design identified at the period of crossover between rehearsals and thus between new choreographers, exemplifying the construction of this Activity Space as a site for teaching within the broader studio space and the temporal setting of the Richmond Ballet rehearsal session(s).

This first extract comes at the period of handover between two pieces being rehearsed. Following the previous rehearsal, those involved have vacated the Dancing and Teaching Spaces to return to the Peripheries, and Naomi’s piece is next in the rehearsal rota for the evening. Having been named by a fellow member moments beforehand, Naomi, as instructor, gathers her notebook with choreographic details and walks into the Teaching Space as is typical and expected of members fulfilling this role; however, it is the design of her spoken turns as she does so that is noteworthy. As she bends down to pick up her notebook in the Peripheries, Naomi utters her first turn ‘oka:y’, lengthening the /eɪ/diphthong such that the completion of the word ‘okay’ coincides with her grasping of the book (lines 1–2, Figure 3). The grasping of the notebook further contextualises her shift into role as instructor, picking up an artefact regularly utilised in the teaching and polishing of choreography and, subsequently, recognisable as such to the dancers in the room.

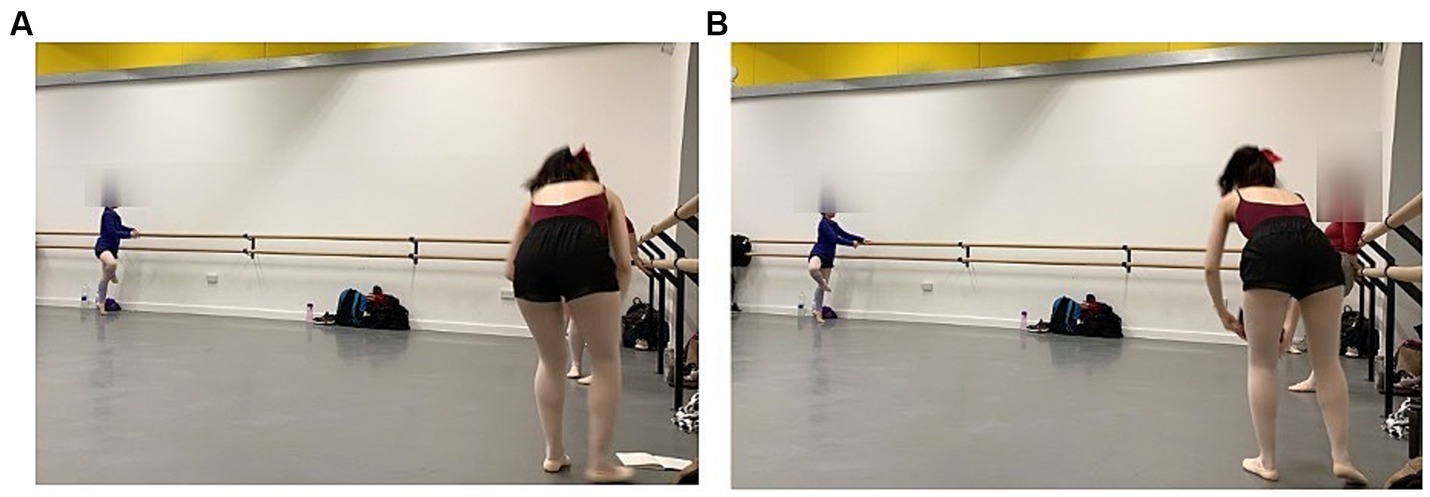

Figure 3. (A,B) Beginning and end of ‘oka:y’, lengthened to coincide with Naomi’s bending down and picking up her notebook.

As she stands and begins to walk from the Peripheries towards the Teaching Space, Naomi adds another lengthened turn, ‘so: (.)’ (lines 3–4, Figure 4). Both tokens are produced with increased loudness and a marked pitch movement on the lengthened vowels consisting of a high step-up followed by a fall-to-low.

Throughout the data corpus, both ‘okay’ and ‘so’, when used by instructors, function as predictors of upcoming instruction-relevant talk. ‘okay’ has been shown to be a marker of sequential transitions (Beach, 1993; Mondada and Sorjonen, 2021; Bangerter and Clark, 2003), and ‘so’ a preface for incipient actions (Bolden, 2009). Tuma (2022) describes the use of ‘okay so’ as a combined phrase in the EFL classroom, where students working together on a language task mark transitions from one task component to the next with ‘okay so’, as well as with embodied actions. In the extract above, the two items are not produced as a combined phrase. Instead, they are separated by a 1.4 s pause, and each item is produced as a separate intonation unit with a fully developed pitch accent. While ‘okay’ accompanies Naomi’s bending down and picking up her notes, ‘so’ occurs as she takes her first step away from the Peripheries and towards the Teaching Space. Therefore, in addition to marking the transition to a new activity, the two tokens appear to function also as turn-holding devices. By vocalising while preparing for and initiating her relocation into the Teaching Space, Naomi ‘[occupies] turn space’ (Keevallik, 2014: 114) and prospectively lays claim to the upcoming sequential slot for vocal and embodied instruction, which will only begin once she has physically reached the Teaching Space.

Thus, ‘okay’ and ‘so’ focus the attention of cast members and indicate to those cast in her piece an upcoming instructional episode. This is supported in the multimodal actions of those dancers cast in the piece as they cease talking and begin to turn their body and gaze towards her (Figure 5), their bodily adjustments indicative of their waiting for instruction. Having been selected as the next instructor in the evening (and her piece the next rehearsal), Naomi’s turn-holding serves to take up this role following selection and hold the floor until she is in the Teaching Space and physically positioned to give dance-related instruction.

The multimodal achievement of this transition, with Naomi’s physical movement towards the Teaching Space as she utters the two tokens, serves a double function. It gathers the attention of her cast dancers from her space in the Peripheries, ensuring their readiness by projecting her upcoming arrival in the Teaching Space and preparing the upcoming instructional activity [see Dausendschön-Gay and Krafft (2009) and Schmidt (2018) for a distinction between projection and preparation]. It also allows her to shift into an instructing role in order to grasp and claim this before being physically present in the corresponding Activity Space. Furthermore, Naomi’s gaze towards the Teaching Space having picked up the notebook projects her target location and further indicating to dancers her shift into instructing role.

No instruction is given whilst Naomi is in the Peripheries, and the floor is held through further spoken turns as she moves into the Teaching Space, continuing to speak without giving actionable imperatives for her dancers. The walk from her position in the Peripheries to the Teaching Space is relatively short and covered by just 10 steps; however, as she walks from one to the other Naomi gives an overview of her general goals and intentions for the rehearsal, stating ‘I wanna do a new bit today’ (line 5). Whilst this turn sets out her intentions for the practical outcomes of the 40-min slot, giving dancers a broad understanding of what is to come, there is still not yet a physical task for them to complete. This is then extended further as she continues ‘I do not wanna spend too long on the bits weve already done’ (lines 6–8), coming to stand with weight firmly distributed across both feet partway through the turn as she utters the word ‘bits’. Naomi has here walked into the centre of the Teaching Space, coming to face the Dancing Space straight on (Figure 6). In doing so, the instructor/learner dyad is established, with this dancer-facing position facilitating not only the best view of everybody for Naomi as instructor but also the best view of herself for the dancing group. This turn design holds significance on two levels, then; the practical, spatial, and temporal need to gather resources and move into the Teaching Space, and the taking up of a particular role in the interaction, projecting the self as the ‘instructor’ ahead of giving active instruction to dancers. Furthermore, the open space of this studio, purpose-built for dance activity, is relevant in relation to this movement into the Teaching Space, demonstrating the concept of ‘architecture for interaction’ (Hausendorf and Schmitt, 2022, p. 441). These periods of handover are facilitated through the shared space, in which all members are mutually visible and easily able to move in line with the shifting roles of the sessions, being easily heard as they do so.

Once here, with both feet firmly planted and body oriented towards the Dancing Space, Naomi gives the first instruction-oriented turn—‘can we just do like a walk through of it’ (with it here referring to the piece as it has been learnt to date)—and continues with further detail about the intended task as she states ‘just for brains and then if things are messy we can tidy them up later’. Dancers respond to this by beginning to move, walking towards the Dancing Space or putting down their drink bottles in preparation and, in doing so, orienting to Naomi’s instructing role and positioning themselves as learners relationally as they adhere to her request and prepare, bodily, to dance. In this regard, Naomi’s spoken turns whilst walking towards the Teaching Space serve as a preface of what is to come once she is positioned in the Teaching Space. Further, this preface also serves as an overview for learners of the main, overarching activity goals for the rehearsal segment.

Naomi’s coordination of her spoken and embodied actions in this extract have constructed the Teaching Space as a site of instructional activity, with her spoken turns holding the floor across several actions as she gathered her notebook and moved into this Activity Space. The nature of this turn design, comprised of two discourse markers with elongated vowels and pauses, and a general overview of the upcoming rehearsal, lays claim to the sequential slot for teaching, which has begun temporally but not spatially: while Naomi has not yet reached the Teaching Space, dancers are not yet given any instructions or tasks. It is only once she is present in the Teaching Space and well positioned to observe the planned walk-through activity that this is actioned by Naomi in her instructing role.

This use of turn design during the period of crossover between rehearsals—holding the floor before entering the Teaching Space—was not particular to this instance or to Naomi. Another example selected to demonstrate the regularity of this phenomenon comes from a separate rehearsal 1 month later in which Tamara is the instructing member.

Much like in the previous extract, Tamara begins her rehearsal session in the Peripheries, having not been involved in the prior rehearsal. In a similar way to Naomi in Extract 1, Tamara holds the floor across several spoken turns as she moves into the Teaching Space, only giving actionable instruction once positioned there, where she may see and be seen. Once again, the turn design of an instructing member as they coordinate their spoken and bodily movement constructs the Teaching Space as a site for instructional activity, with learners this time waiting to enter the Dancing Space until Tamara has begun her own towards the Teaching Space.

Initially, the shift into the next rehearsal segment—Tamara’s piece—is marked by a fellow member as they verbalise both this shift in activity and Tamara’s shift into an instructor role, telling her ‘Tamara youre on’ (line 1). With the rehearsal slot commenced, and Tamara’s role as instructor announced, she begins to speak from her position in the Peripheries as she starts up her laptop to locate the music for the piece, uttering a lengthened ‘um::’ (line 3). Like Naomi’s, this elongated vocalisation allows her to occupy turn space vocally, holding the floor between now and her eventual start of the sequence. Tamara’s next turn is also similar to several of Naomi’s as she gives an overview of her aims for the rehearsal session—‘so we are gonna do a chunk of the same bit as last week’ (lines 3–4). She then extends this turn, adding ‘to reiterate I’m experimenting it may change’ (line 5). This extension, adding information about the choreographic process, not only serves to remind dancers, practically, that the upcoming choreography is subject to change but also lengthens her turn and continues to hold the floor as she works on her laptop. Whilst still in the Peripheries, Tamara also tells her cast dancers ‘I’ve broken it down into the bars and counts’ (lines 8–9), giving information about the work she has done outside of rehearsals in counting and dividing the music, which is particularly challenging to count clearly. Much like Naomi, then, Tamara—whose role as instructor has been invoked, but who is not yet in the Teaching Space—produces talk that is sequence-organisational. While offering information to cast members (rather than, for example, specific or actionable imperatives), Tamara manages the temporal emergence of the instruction sequence and her own claim to the next sequential slot while not yet in the space from which she will eventually perform instruction.

Worth noting at this point are the actions of cast members as Tamara remains in the Peripheries. Rather than enter the Dancing Space, as is typically the case for those involved in an upcoming rehearsal, they remain in the Peripheries also, orienting to Tamara’s role as selected sequence initiator through their gaze and bodily orientation. In doing so, they appear to be awaiting Tamara’s own movement as initiator, beginning the instruction sequence proper by entering the relevant Activity Space and, in doing so, prompting their own movement. Their behaviour treats Tamara as having authority over the temporal and spatial framing of the rehearsal sequence.

Having given this contextual information regarding choreography and music, Tamara produces a lengthened ‘so:’ (line 11), extending the /oʊ/diphthong. Much like Naomi’s utterances ‘oka:y’ and ‘so:’, then, this lengthened turn serves to hold the floor as well as marking the transition to the upcoming instruction. Having started walking towards the middle of the room, Tamara comes to stand, holding her notebook as she does so and giving the aims of the session; ‘and I’m gonna try some of it to the music today as well’ (lines 11–12), coming to a stand as she utters the word ‘music’. She then starts to walk through the Dancing Space (Figure 7) and begins another spoken turn—‘so: if I could do the sa:me (.) formation: (.) as before’ (lines 14–17), alluding back to the previous week’s session. Much like Naomi, Tamara lengthens this turn with pauses and elongated vowel sounds, extending the duration of her spoken turn. Her turn has been designed, then, emergently, such that she completes the turn when she approaches the middle of the room and then turns to face dancers, asking one dancer ‘Lauren can you remember’ (line 17, Figure 8). In doing so, Tamara has coordinated her verbal and embodied resources in order to arrive in the Teaching Space, a point where she is able to effectively view the full formation and complete the spoken turn at approximately the same time, turning now to a specific query aimed at Lauren, a particular cast member. The combination of bodily and spoken resources to align temporally resembles Goodwin’s (1979) finding that turn construction occurs in situ and is fitted to specific recipients and their embodied conduct. The turn being produced in this way (lines 14–17) is the first to give an actionable, dance-based instruction to the dancers, with the ‘same formation as before’ calling them to create a familiar pattern in the choreography. Tamara’s coordinated completion of this instructional turn along with the significant bodily turn to face the dancers establishes the familiar instructor/learner dyad which provides the most effective view of dancers. Once here, Tamara walks backwards, maintaining this bodily arrangement and moving closer to the mirrored wall, providing more space for those dancing.

Tamara’s movement through the Dancing Space and into the Teaching Space is followed by dancers’ own movement into the Dancing Space behind her. The sequentiality of this physical movement, following Tamara’s walk towards the Teaching Space, indicates a recognition on the part of group members of Tamara’s turn ‘so: if I could do the sa:me (.) formation: as before’ as an actionable instruction and the beginning of the rehearsal session. Further, this suggests that the Teaching and Dancing Spaces exist in a dyadic relationship, relative to one another, rather than as entirely individual Spaces; the Teaching Space is co-constructed relative to the Dancing Space with members executing the steps, and vice versa.

Once positioned in the normative Teaching Space, Tamara’s imperatives become more specific and practical in nature, requiring particular actions on the part of the cast dancers, with one example being the request ‘can I have four in the middle circle’ (lines 23–25). This strengthens the notion that Tamara’s previous turns were designed to hold the floor having been selected by name as the next speaker by other members in accordance with the pre-circulated rota. Tamara’s previous turns contrast in their more general, broad, and informative nature to these more specific imperatives, which request responses by way of bodily actions on the part of specific members in the Dancing Space. Given her position in the peripheries as she locates the music on her laptop, it may be noted that Tamara’s turns are issued when she has been selected as next speaker, but is not yet ready to enter the Teaching Space and deliver instructional activity. Furthermore, her turns whilst walking serve to frame the upcoming instructional activity in much the same way as Naomi’s in extract 1, making sense of it for learners and achieving something that is not dependant on visibility for these learners. The distinction between general and specific imperatives partially resembles Vine’s (2004) distinction between ‘NOW’ and ‘LATER directives’ as well as Szczepek Reed et al.’s (2013) between ‘local’ vs. ‘non-local action directives’. The distinction allows instructors to specify whether an imperative is made relevant in the here and now, requiring immediate compliance; or at some unspecified point in the future, in- or outside the current learning environment.

Finally worth noting is an action taken by Tamara as dancers move into the requested formation: she places her notebook on the floor in front of her, standing behind it. This somewhat atypical action gives boundary to the Activity Space, marking the edge of the Teaching Space with a physical object as a marker that is not crossed by any dancing members throughout the rehearsal’s duration (Figure 9).

These two extracts have demonstrated one of the ways in which instructor-choreographers position the Teaching Space as a site for instructional activity, drawing on the coordination of multimodal resources in order to hold the floor as they move into this Activity Space from another. In doing so, they alter their speech, slowing their turns and lengthening vowel sounds as well as designing the content of these turns such that no instruction requiring physical dance action is given until instructors are positioned in this Activity Space. Consequently, these turns serve to lay anticipatory claim to the upcoming teaching slot until the instructing member has arrived in the Teaching Space.

From a practical standpoint, it has been highlighted that the Teaching Space is the most effective space from which to see a full piece and from which to be seen by all dancers, and as such this turn design indicates a priority given to visibility by these instructing members during rehearsals. Indeed, it has been noted that in dance instructional settings visibility of the teaching member is prioritised, and that ‘teachers may take extra precautions to render their bodies adequately visible’ (Keevallik, 2010, p. 416). Looking beyond the practical, this pattern of turn design speaks also to the frequently shifting roles in this part-time, voluntary community group and the ways in which members ‘pick up’ these roles as a gradual progression. It is through actions such as these that the Activity Spaces, and in particular the Teaching Space, come to be normatively co-constructed, serving as zones for particular types of activity with which they are being coupled. However, the boundaries of the Teaching Space are not so rigidly defined as a static diagram may suggest, and it is this flexibility that we turn to next, as we consider the pliable nature of the Teaching Space boundaries.

Whilst the Teaching Space typically remained at the front of the studio, against the mirrored wall, throughout the data corpus, this Activity Space was often lengthened and moulded in accordance with the aims of a particular activity. In these instances, the physical relationship of members in space was maintained, with the instructor-choreographer remaining in front of the dancing members in the normative dyadic arrangement of instructor/learner (and, consequently, Teaching Space/Dancing Space). We turn now to several moments from the data corpus that demonstrate the ways in which members continue to co-construct and recognise the Teaching Space as a distinct zone and site for instructional activity, but one with flexible boundaries. The employment of a number of multimodal resources on the parts of both instructors and learners coordinate to maintain the characterisation of this as the Teaching Space that is being extended, rather than as an act of entering the Dancing Space.

Within this first extract, Naomi as instructor is teaching a new, challenging sequence of steps to the learning dancers. The final pattern of the steps will be two concentric circles, with four members in each moving in opposite directions. In the learning of this sequence, Naomi has opted to teach the steps alone, removing the changing bodily alignment in a common teaching method which aims to reduce confusion and ensure that all dancers are executing the correct steps. Furthermore, teaching the steps in a straight line provides greater visibility for dancers copying the sequence as their instructor demonstrates, facilitating greater ease of learning. Throughout this extract, Naomi remains in front of the dancing group such that she is visible to all members; however, she lengthens the Teaching Space into the studio and, in doing so, shortens the Dancing Space collaboratively with members as they move to stand behind her (see Figures 10, 11).

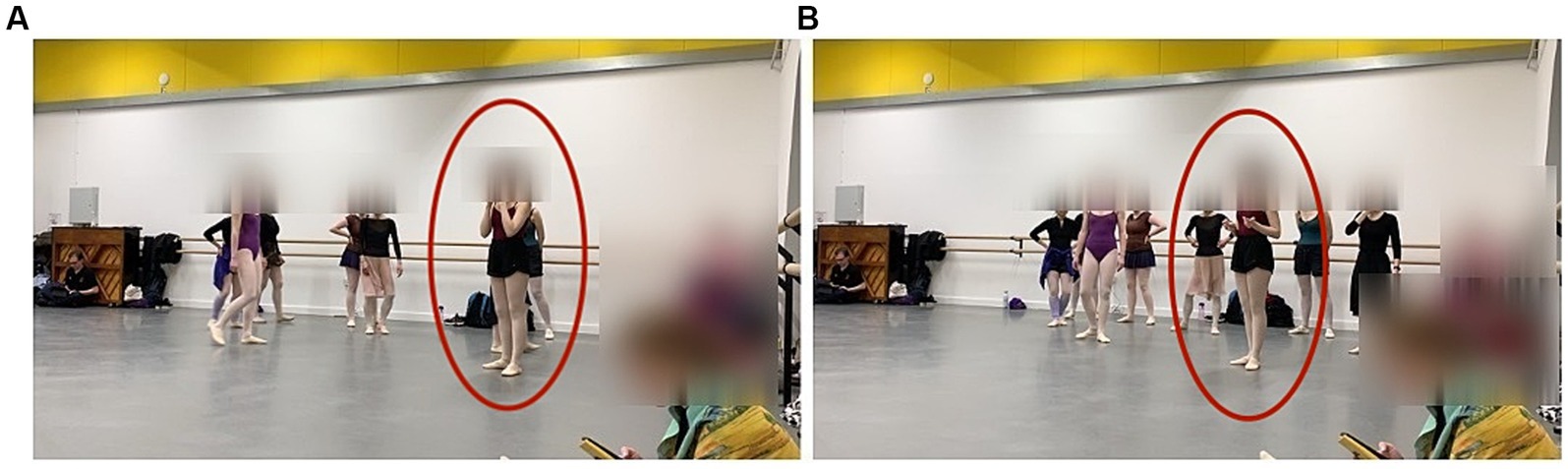

Figure 11. (A,B) Naomi positions herself first, and others position themselves in spatial relation to Naomi.

At the beginning of the extract, Naomi outlines her goals for this section of the rehearsal from her position near the mirrored wall, telling the dancers ‘the next step im gonna teach it straight’ and adding contextual information ‘it moves in a circle but were gonna learn it straight’ (lines 1–4). With this overview in place, Naomi walks towards the corner of the room, pointing with her index finger towards the target direction and stepping forwards in line with the projected trajectory and simultaneously with a place formulation (Schegloff, 1972): ‘so lets just like do it from the corner so weve got space’ (lines 6–8, Figure 10). This spoken turn, in addition with Naomi’s movement as she begins to walk towards the corner, projects the intended start position for this teaching section, with her point focussing in on the section of the room she intends to teach from. With the dancers already aware that they will be learning a new step, Naomi here projects also the extension of the Teaching Space, pointing to where she will extend it prior to doing so.

Naomi positions herself first, facing the front of the studio (the mirrored wall) and planting both feet firmly such that her weight is evenly spread. The cast dancers then move to position themselves behind her (Figure 11). What results, then, is the familiar instructor/learner spatial relationship, with the instructing member in front of dancing members, and with the Teaching Space stretched further into the room. Whilst here, dancing members also orient to Naomi’s role as instructor through their gaze patterns, looking to her as she speaks and watching her bodily movements as she dances in the same way as is typical with the normative spatial arrangements seen in section one.

Together, through this bodily coordination of the eight parties present and actively involved in this dancing activity, Richmond Ballet members have co-constructed the physical relationship between the Dancing Space and Teaching Space, maintaining this in a different section of the room with cast members positioning themselves as learners behind Naomi, who in turn is positioned by them as a knowledge source. The familiar instructor/learner actions indicate that the Teaching Space is a relative construction, then, and not bound to the normative arrangements that see it occupying a static, thin strip of space. Rather, this Activity Space is flexible in relation to the needs and goals of the activity underway.

A number of multi-modal features within this episode continue to characterise the space as an extended Teaching Space rather than the entry of an instructor into the Dancing Space. Before the target sequence is demonstrated and taught, Naomi addresses the dancers as a group, turning as she does so such that she is facing the dancing members as she tells them ‘everyones going to do the same on the same leg’ (lines 14–16), turning to face her learners as they gaze towards her and turning back to face the front as she leads into the demonstration ‘were going to do’ (line 18, Figure 12).

Whilst her feet remain facing the front of the room, with her bodily torque (Schegloff, 1998) indicating this to be a temporary alignment, Naomi’s decision to face the dancers as she delivers this turn (along with the reciprocal gaze of learners) maintains the face-to-face dyad typically seen during Richmond Ballet rehearsals, strengthening further the understanding that the Teaching Space is still present and oriented to multimodally by all participants, simply lengthened. Indeed, this arrangement is reestablished at several points throughout the teaching segment, with Naomi turning her head and gaze towards the dancing members rather than straight ahead as is the choreographed alignment (Figure 13). The dancers display their recognition of Naomi’s head turn as an instructional move by not turning their own heads (which would treat the head turn as a piece of choreography) and by looking to her instead.

In addition to these bodily actions, positioning this as the site of teaching and, therefore, an extension of the Teaching Space, Naomi’s continued instructional turns fall in line with many other instances of instructional activity in the data corpus. Her spoken counting of the steps (lines 18–19) serves to indicate the tempo of the new sequence to the learners, familiarising them with it before attempting them with music. Naomi’s rhythmically delivered counts help synchronise the dancers’ embodied movements (see also Keevallik, 2020; Hofstetter and Keevallik, 2023) and align their bodies (Krug, 2022) with the future musical rhythm. In this way, her turns illustrate her continuing instructing activity and, consequently, the space she is in as the Teaching Space.

Within this episode, Naomi and her learners extend the Teaching Space beyond its normative boundaries, collaboratively moving the Activity Space further into the room as she remains in front of the dancers in the traditional instructor/learner relationship. Naomi and the dancers employ a number of multimodal resources to characterise this as the Teaching Space extended (versus, for example, entry of the instructor into the Dancing Space), including Naomi’s continued instructional turns whilst presenting new steps, the maintenance of bodily alignment of both parties relative to each other, and the gaze of learners as they watch and follow Naomi’s actions. Furthermore, Naomi’s pointing and reference to ‘the corner’ serve to highlight this as an exception to the norm, making learners aware through this place reference—a verbal means of shifting the parameters of this Activity Space away from the normative arrangements.

To explore the flexible boundaries of the Teaching Space further, we turn now to an extract in which an instructor-choreographer, Naomi, co-constructs with a sub-section of the learners a micro-arrangement of the Teaching and Dancing Spaces, actioning a shift in the participation framework (Goffman, 1981, p. 134). This extract demonstrates further the flexibility of the Teaching Space as a co-constructed Activity Space which is not confined to a thin strip against the mirrored wall, strengthening the analyses and identification of this as a flexible and emergent Activity Space.

Within this extract Naomi, in the role of instructor, is instructing a “walking through” of the piece, counting from the Teaching Space to provide a steady tempo and accompany the dancers. One dancer poses a question, and Naomi moves closer to the dancer and her line, constructing a micro-arrangement of Teaching and Dancing Spaces before returning to the original arrangement and addressing the group as a whole once again, drawing on several multimodal resources in doing so including prosody, turn design, and proximity.

At the beginning of this extract, Naomi stands in the normative spatial arrangements for instructor and learners, facing her dancers from the front of the room. She gives instructions from here, counting the tempo and rhythm as she observes (lines 1–2). One dancer, Skylar, makes a specific request—‘can you go over the middle lines part’ (line 4). Such requests for clarification are frequent during practicing episodes, aiming to ensure clarity of choreography amongst dancers. Naomi responds as she begins to walk, agreeing ‘yeah yeah sure’ (line 8) and moving between the two dancers in the front row to reach the middle dancers in the formation and stand in front of them (lines 5–10, Figure 14).

This moment illustrates a change in the participation framework (Goffman, 1981, p. 134) in which a smaller sub-section of the dancing group become the ‘ratified participants’ in the instructional sequence (p. 134). In facilitating this, Naomi’s move closer to these learners constructs a micro Teaching Space and Dancing Space in order to get closer to those in this central line, who dance a different sequence to those around them. Proximity is a central factor here as Naomi stands in front of those who require particular instruction, allowing greater visibility for these members. This shift in participation framework and construction of a micro Activity Space arrangement is further achieved through changes in prosody, with Naomi now speaking only to this line less loudly comparative to the raised volume with which she typically addresses the full dancing group.

Particularly significant for the characterisation of this micro-arrangement are the actions of other dancers. As Naomi assists this middle row with the query relating to them only, several dancers continue to practice alone, no longer oriented to Naomi through their bodily alignment, gaze, or actions. The decision to engage in this independent practice demonstrates an awareness that, now she has come to speak specifically to a few members, Naomi is not addressing the group as a whole, and they are not ratified participants in the instructional activity at this moment. They are not, therefore, orienting to Naomi as instructor, unlike in the previous extracts where, although the instructor had moved deeper into the studio, members continued to orient to them as instructor, standing behind them and gazing towards them.

Significant for the characterisation of space in this episode is Naomi’s return to the normative Teaching Space and restoration of the prior participation framework along with the normative spatial arrangements. Whilst in the micro-arrangement, speaking with the central row of the formation, Naomi responds to a dancer query (line 12) with a specific instruction regarding how long dancers ought to take to execute a particular movement (lines 13–16). Having given the response, Naomi raises her voice as she speaks (line 19) and begins to walk back in front of the broader formation of learners (Figure 15). As seen elsewhere in the data corpus, adjustments in prosody such as raised volume were used to address a widened audience relative to the talk surrounding it. In this instance, then, the prosody of Naomi’s turn as well as her movement back towards a visible position at the front of the dancing group indicate to the dancers that the period of specific attention to a subset of the dancers is widening to include them, also, and that they are, once again, ratified participants in the instructional activity.

In addition to this raised volume, Naomi’s turn is lengthened by pauses mid-turn; (‘that’s a good point actually make sure that that (.) from the plie when you push up (.) use all three counts for that’). Looking to the temporality of the first pause, we see that it coincides with Naomi reaching the front of the room and turning to face the dancers before demonstrating, bodily, the section being discussed (a plié). This turn is therefore designed such that Naomi’s bodily actions as she models a ‘correct’ or desired step align with the terminology and description in her spoken turn. This resembles the turn design seen in Extracts 1 and 2 above, in which instructor-choreographers design their turns in order to hold the floor whilst moving into the (normative) Teaching Space from a different Activity Space.

The above extract demonstrates a distinction between an instructing member’s co-construction, along with the actions of learners and unratified participants, of a micro-arrangement of the Teaching and Dancing Spaces, responding to one particular member’s query, and the normative Teaching Space, co-constructed multimodally through resources used by the instructor as well as through dancing members’ orientation to and alignment with this projected role. The actions of dancers as they engage in independent practice, as well as their bodily orientation to Naomi as she returns to stand in front them, strengthen this characterisation, making visible the flexible and emergent boundaries of Activity Spaces.

The analysis contributes to the growing literature on instructional space(s) and their interactional negotiation, organisation, and ongoing management. The data show that members of Richmond Ballet socially construct the room in which they meet weekly as a set of normatively defined Activity Spaces (Dancing Space, Peripheries, Teaching Space) (Smart, 2025). Through a range of verbal and embodied practices, they orient to Activity Spaces as zones of ‘Situated Activity’ (Goodwin, 2003, p. 9), where space and activity are routinely and systematically coupled. The analytical focus on teaching and other instructional activities showed that dancers and instructor-choreographers co-construct the Teaching Space locally and collaboratively through verbal turn design and embodied practices.

At the beginning of a new rehearsal sequence, new instructor-choreographers transition from their non-teaching to their teaching role. While they are making their way there from the Peripheries to the Teaching Space, they can hold the floor with prefacing talk and prosodic lengthening. This turn design lays claim to the upcoming teaching slot and projects its imminent beginning. However, instructors in the data set withhold instructional talk until they have taken up their position in the Teaching Space. Participants who are not yet in the Dancing Space wait for instructors to leave the Peripheries before they do so themselves. Participants’ treatment of the Teaching Space as the place from which instruction talk is to be delivered shows their orientation to the coupling of Activity Spaces with specific activities. This in turn reveals that a simplistic notion of individuals’ roles in the dance company as, for example, dancer or choreographer, does not sufficiently explain their actions within it. Instead, participants are found to verbally and physically establish themselves in locally negotiated spaces first before they perform the activities that are normatively coupled with those spaces. In contrast to Reed and Szczepek Reed’s (2013) finding that in music masterclasses, masters initiate and end instruction by moving into and retreating from a single engagement space which they occupy jointly with the learner, this data set has shown that a ballet rehearsal room is co-constructed into separate Activity Spaces for instruction (Teaching Space) and performance (Dancing Space). This separation is reminiscent of Veronesi’s (2007) and Batlle Rodríguez and Evnitskaya’s (2024) observations that teachers can step back to give students space for joint learning activities that do not directly involve the teacher. For example, in Extract 2, Tamara actively walks backwards, away from the dancers, which provides them with a larger Dancing Space.

During rehearsals-in-progress, instructors and dancers can extend the Teaching Space into other Activity Spaces if local requirements make this necessary. In doing so, they treat the boundaries of the Teaching Space as flexible and emergent. For example, instructors can move the whole group into (what would normatively be considered) the Peripheries, thereby extending both Teaching and Dancing Space beyond their previous boundaries; they may also construct a micro-arrangement of Teaching and Dancing Spaces in line with the particular goals of an activity. Newly emerging spaces are co-constructed not only via physical relocation but also through turn design, such as the decreased loudness with which newly emerging groups of ratified participants are addressed. In each case, a general orientation of instructors in front and dancers behind is maintained, as dancers orient to instructors multimodally and vice versa. This shows that physical space as such does not determine the activities that take place within it, but that spaces for activities are co-constructed locally, emergently, and collaboratively.

The above analysis has shown the relevance of jointly constructed space for embodied activities, and vice versa. This means that there are implications not only for space as an activity-related concept, but also for embodied activity as a spatial one (see also Mondada, 2013). It appears that in ballet rehearsals, some instructional activities require certain configurations and positionings in space to allow for, for example, visibility, demonstration, imitation, and group synchronisation; and that actions that happen outside of those configurations are constructed as liminal or transitional. In another context, Lundesjö Kvart (2020) has shown that instructional space relies on proximity, which is co-created when horse-rider pairs pass by riding instructors during the limited time window that their speed and overall mobility allows. Similarly, Jakonen (2020) shows teachers’ in-classroom mobility to be a resource for co-creating local instruction sequences as teachers make their rounds from desk to desk. It is this interactional exploitation of mobile positioning, aligned temporally with the performance of instructional actions, that makes the analysis above relevant to learning contexts beyond dance. Across different embodied instruction settings, learners and teachers are likely to carve out designated but inherently flexible spaces for instruction-relevant activities, and to do so verbally, prosodically, and through embodied actions. From such a perspective, the matter of instructional space has much potential for future research.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because participant consent is limited to researchers involved in the study viewing the data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bmFvbWkuc21hcnRAa2NsLmFjLnVr.

The studies involving humans were approved by the King’s College London Research Ethics Office. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

NS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BSR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the London Interdisciplinary Social Science DTP [grant number ES/P000703/1].

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Auer, P., and Stukenbrock, A. (2022). “Deictic reference in space” in Pragmatics of space. eds. A. H. Jucker and H. Hausendorf (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 23–61.

Bangerter, A., and Clark, H. H. (2003). Navigating joint projects with dialogue. Cogn. Sci. 27, 195–225. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog2702_3

Batlle Rodríguez, J., and Evnitskaya, N. (2024). Teachers’ multimodal resources for delegated peer repair: maximizing interactional space in whole-class interaction in the foreign language classroom. Mod. Lang. J. 108, 297–321. doi: 10.1111/modl.12910

Beach, W. A. (1993). Transitional regularities for ‘casual’ “okay” usages. J. Pragmat. 19, 325–352. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(93)90092-4

Best, K., and Hindmarsh, J. (2019). Embodied spatial practices and everyday organization: the work of tour guides and their audiences. Hum. Relat. 72, 248–271. doi: 10.1177/0018726718769712

Bolden, G. B. (2009). Implementing incipient actions: the discourse marker “so” in English conversation. J. Pragmat. 41, 974–998. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2008.10.004

Broth, M., and Mondada, L. (2013). Walking away: the embodied achievement of activity closings in mobile interaction. J. Pragmat. 47, 41–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2012.11.016

Dausendschön-Gay, U., and Krafft, U. (2009). Preparing next actions in routine activities. Discourse Process. 46, 247–268. doi: 10.1080/01638530902728900

Douglah, J. (2020). “Use the mirror now” – demonstrating through a mirror in show dance classes. Multimodal Commun. 9:20200002. doi: 10.1515/mc-2020-0002

Douglah, J. (2021). “BOOM, so it will be like an attack”: demonstrating in a dance class through verbal, sound and body imagery. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 29:100488. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100488

Ehmer, O. (2021). Synchronization in demonstrations: multimodal practices for instructing body knowledge. Ling. Vanguard 7:20200038. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2020-0038

Ehmer, O. (2023). Recycling turns in multimodal dance instructions. Paper presented at the 18th international pragmatics conference, Brussels, 9–14 July 2023.

Ehmer, O., and Brône, G. (2021). Instructing embodied knowledge: multimodal approaches to interactive practices for knowledge constitution. Ling. Vanguard 7:20210012. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2021-0012

Goodwin, C. (1979). “The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation” in Everyday language: studies in ethnomethodology. ed. G. Psathas (New York: Irvington Publishers), 97–121.

Goodwin, C. (2003). “Situated activity” in The handbook of discourse analysis. eds. D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, and H. E. Hamilton (Malden, MA: Blackwell), 107–121.

Hammersley, M., and Atkinson, P. (2019). Ethnography: principles in practice. Fourth Edn. Oxford: Routledge.

Harjunpää, K., Mondada, L., and Svinhufvud, K. (2018). The coordinated entry into service encounters in food shops: managing interactional space, availability, and service during openings. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 51, 271–291. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2018.1485231

Hausendorf, H. (2010). “Interaktion im Raum: Interaktionstheoretische Bemerkungen zu einem vernachlässigten Aspekt von Anwesenheit” in Sprache intermedial: Stimme und Schrift. eds. A. Deppermann and A. Linke (Bild und Ton, Berlin: De Gruyter), 163–197.

Hausendorf, H. (2013). “On the interactive achievement of space – and its possible meanings” in Space in language and linguistics: geographical, interactional, and cognitive perspectives. eds. P. Auer, M. Hilpert, A. Stukenbrock, and B. Szmrecsanyi (Berlin: De Gruyter), 276–303.

Hausendorf, H., and Jucker, A. H. (2022). “Doing space: the pragmatics of language and space” in PRagamtics of space. eds. A. H. Jucker and H. Hausendorf (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 1–20.

Hausendorf, H., and Schmitt, R. (2022). “Architecture-for-interaction: built, designed and furnished space for communicative purposes” in Pragmatics of space. eds. A. H. Jucker and H. Hausendorf (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 431–472.

Heritage, J., and Sorjonen, M.-L. (1994). Constituting and maintaining activities across sequences: and-prefacing as a feature of question design. Lang. Soc. 23, 1–29. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500017656

Hofstetter, E., and Keevallik, L. (2023). Prosody is used for real-time exercising of other bodies. Lang. Commun. 88, 52–72. doi: 10.1016/j.langcom.2022.11.002

Ivaldi, A., Sanderson, A., Hall, G., and Forrester, M. (2021). Learning to perform: a conversation analytic systematic review of learning and teaching practices in performing arts lesson interactions. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 28:100459. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100459

Jakonen, T. (2020). Professional embodiment: walking, re-engagement of desk interactions, and provision of instruction during classroom rounds. Appl. Linguis. 41, 161–184. doi: 10.1093/applin/amy034

Keevallik, L. (2010). Bodily quoting in dance correction. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 43, 401–426. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2010.518065

Keevallik, L. (2013). “Here in time and space: decomposing movement in dance instruction” in Interaction and mobility: Language and the body in motion. eds. P. Haddington, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Berlin: De Gruyter), 345–370.

Kelly, R. (1999). One step forward and two steps back: Woolgar, reflexivity, qualitative research and a line dancing class. Ethnogr. Stud. 4, 1–13.

Keevallik, L. (2015). “Coordinating the temporalities of talk and dance” in Temporality in interaction. eds. A. Deppermann and S. Günthner (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 309–336.

Keevallik, L. (2020). “Linguistic structures emerging in the synchronization of a Pilates class” in Mobilizing others: grammar and lexis within larger activities. eds. C. Taleghani-Nikazm, E. Betz, and P. Golato (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 147–173.

Keevallik, L. (2021). Vocalizations in dance classes teach body knowledge. Ling. Vanguard 7:20200098. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2020-0098

Kendon, A. (1990). Conducting interaction: Patterns of behavior in focused encounters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krug, M. (2022). Temporal procedures of mutual alignment and synchronization in collaborative meaning-making activities in a dance rehearsal. Front. Commun. 7:957894. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.957894

Lundesjö Kvart, S. (2020). Instructions in horseback riding: the collaborative achievement of an instructional space. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 25:100253. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.10.002

Macbeth, D. (1992). Classroom “floors”: material organizations as a course of affairs. Qual. Sociol. 15, 123–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00989491

Mazeland, H. (2019). “Activities as discrete organizational domains” in Embodied activities in face-to-face and mediated settings: social encounters in time and space. eds. E. Reber and C. Gerhardt (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan), 29–61.

McIlvenny, P., Broth, M., and Haddington, P. (2009). Communicating place, space and mobility. J. Pragmat. 41, 1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.014

McIlvenny, P., Broth, M., and Haddington, P. (2014). Moving together: mobile formations in interaction. Space Cult. 17, 104–106. doi: 10.1177/1206331213508679

Mondada, L. (2009). Emergent focused interactions in public places: a systematic analysis of the multimodal achievement of a common interactional space. J. Pragmat. 41, 1977–1997. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.019

Mondada, L. (2013). “Interactional space and the study of embodied talk-in-interaction” in Space in language and linguistics: geographical, interactional, and cognitive perspectives. eds. P. Auer, M. Hilpert, A. Stukenbrock, and B. Szmrecsanyi (Berlin: De Gruyter), 247–275.

Mondada, L. (2019a). Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. J. Pragmat. 145, 47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2019.01.016

Mondada, L. (2019b). Conventions for multimodal transcriptions. Version 5.0.1. Available at: https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription (Accessed September 30, 2024).

Mondada, L., and Sorjonen, M.-L. (2021). “OKAY in closings and transitions” in OKAY across languages: toward a comparative approach to its use in talk-in-interaction. eds. E. Betz, A. Deppermann, L. Mondada, and M. L. Sorjonen (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 94–127.

Noy, C. (2012). Inhabiting the family-car: children-passengers and parents-drivers on the school run. Semiotica 2012, 309–333. doi: 10.1515/sem-2012-0065

Reed, D. J. (2025). “Ethnomethodology of dance: the achievement of rhythm in the waltz and Vals” in Ethnomethodological studies of music. eds. P. Tolmie, A. Crabtree, D. Randall, and M. Rouncefield (London: Routledge).

Reed, D., and Szczepek Reed, B. (2013). “Building an instructional project: actions as components of music masterclasses” in Units of talk – Units of action. eds. B. Szczepek Reed and G. Raymond (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 313–341.

Reed, D., Young, J., and Wooffitt, R. (2024). Walking with Gail: the local achievement of interactional rhythm and synchrony through footwork. Soc. Interact. Video Based Stud. Hum. Social. 7. doi: 10.7146/si.v7i1.134103

Robinson, J. D. (2012). “Overall structural organization” in The handbook of conversation analysis. eds. J. Sidnell and T. Stivers (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), 257–280.

Schegloff, E. A. (1972). “Notes on a conversational practice: formulating place” in Studies in social interaction. ed. D. Sudnow (New York: The Free Press), 75–119.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmidt, A. (2018). “Prefiguring the future: projections and preparations within theatrical rehearsal” in Time in embodied interaction. synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources. eds. A. Deppermann and J. Streeck (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 231–260.

Selting, M., Auer, P., Barth-Weingarten, D., Bergmann, J., Bergmann, P., Birkner, K., et al. (2009). Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2). Gesprächsforschung 10, 353–402. Translated and adapted for English by Couper-Kuhlen, E. and Barth-Weingarten, D. (2011). Gesprächsforschung, 12, pp. 1–51. Available at: http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2011/px-gat2-englisch.pdf

Smart, N. (2025). Choreographing community: a multi-scalar exploration of an amateur dance company as a community of practice ', (PhD thesis): King’s College London.

Smith, R. J. (2017). The practical organisation of space, interaction, and communication in and as the work of crossing a shared space intersection. Sociologica 11.

Streeck, J., Goodwin, C., and LeBaron, C. (Eds.) (2011). Embodied interaction: language and body in the material world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Szczepek Reed, B., Reed, D., and Haddon, E. (2013). NOW or NOT NOW: coordinating restarts in the pursuit of learnables in vocal master classes. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 46, 22–46. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2013.753714

Tuma, F. (2022). “Okay, so, moving on to question two”: achieving transitions from one item to another in paired EFL speaking tasks. Slovo a Slovesnost 83, 163–187.

Tuncer, S. (2018). Non-participants joining in an interaction in shared work spaces: multimodal practices to enter the floor and account for it. J. Pragmat. 132, 76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2018.05.013

Veronesi, D. (2007). Movimento nello spazio, prossemica e risorse interazionali_ Un’analisi preliminare del rapporto tra modalità in contesti didattici [movement in space, proxemics and interactional resources: a preliminary analysis of the relationship between modalities in educational contexts]. Bulletin Suisse de Linguistique Appliquée 85, 107–129.

Keywords: conversation analysis, multimodality, ballet, rehearsal, choreography

Citation: Smart N and Szczepek Reed B (2025) Co-creation of Activity Spaces in an amateur dance group: interactional construction of the Teaching Space. Front. Commun. 9:1517858. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1517858

Received: 27 October 2024; Accepted: 23 December 2024;

Published: 16 January 2025.

Edited by:

Cordula Schwarze, University of Marburg, GermanyReviewed by: