- Department of Communication Studies and Philosophy, Utah State University, Logan, UT, United States

Loneliness is an urgent public health crisis that is associated with deleterious outcomes such as early mortality and mental health issues. This study investigates how interpersonal communication apprehension is linked to loneliness through the basic psychological human needs. Guided by a theoretical integration of the social skill deficit vulnerability model and basic psychological needs theory, we examined survey reports from 406 participants. The results showed that interpersonal communication apprehension was related to all three basic psychological needs. Moreover, competence significantly mediated the link between apprehension and loneliness. We discuss the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Introduction

In 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General declared an epidemic of loneliness and urged individuals, organizations, and communities to address loneliness as a public health crisis (Office of the Surgeon General (OSG), 2023). According to Hawkley and Cacioppo (2010), loneliness is “a distressing feeling that accompanies the perception that one’s social needs are not being met by the quantity or especially the quality of one’s social relationships” (p. 218). An abundance of research shows the detrimental effects loneliness has on physical, emotional, and mental well-being (see Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Although there are many reasons why individuals are prone to loneliness, including environmental and genetic factors (Schermer and Martin, 2019), social issues such as communication skills are also related to loneliness (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Indeed, multiple social scientific fields have developed theories that highlight the links between psychosocial well-being and mental health. For instance, social determination theory posits that humans are at risk for psychological distress when their basic psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) are not being met (Ryan, 1995). Likewise, the social skill deficit vulnerability model takes a communication approach to understanding mental health and posits that people with low social skills are at risk for psychological distress (Segrin and Flora, 2000). This investigation integrates these two theoretical perspectives on mental health. Specifically, we posit a model that examines a direct link from interpersonal communication apprehension to loneliness, and the mediating role of the basic psychological human needs. In doing so, we highlight how both interpersonal communication factors and psychological factors combine to predict loneliness.

Theoretical foundations

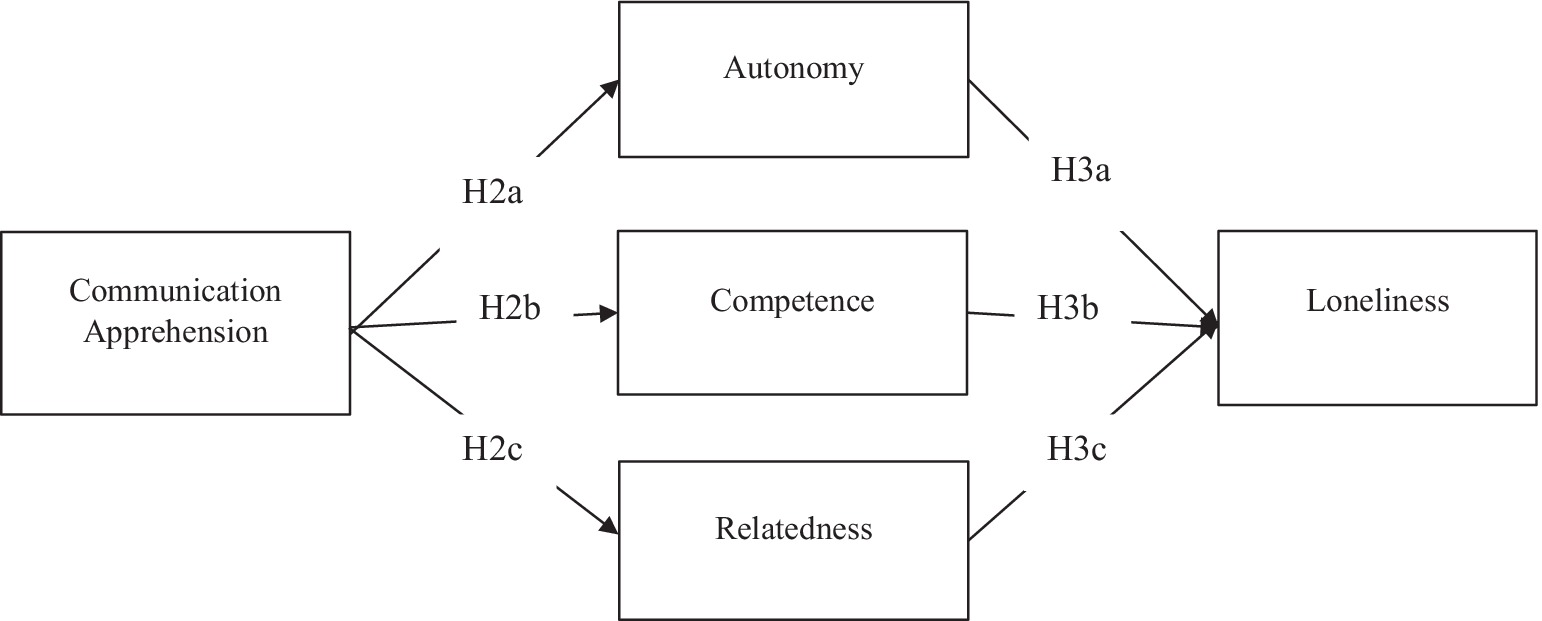

Figure 1 shows the hypothesized mediation model for this study. As mentioned, the model integrates principles from both the social skill deficit vulnerability model and social determination theory. Below, we explain the principles of both theories and how they form the foundation of this model.

Figure 1. The hypothesized model. We hypothesize a direct effect from communication apprehension to loneliness, though it is not visually depicted in the model. H2a-c and H3 a-c show the hypothesized paths to and from each distinct basic psychological need.

First, the social skills deficit vulnerability model is a particularly useful theoretical framework for understanding the links between interpersonal communication factors and mental health. A key tenet from the model is that those with low social skills are at risk for poor psychological health because they are less able to manage stress (Segrin and Flora, 2000; Segrin et al., 2016). In essence, the model posits that people with low social skills have a difficult time with stress, life transitions, and maintaining an overall high quality of life (Segrin et al., 2016). Conversely, people with high social skills are able to buffer themselves from the negative effects of stress because they can engage in prosocial behaviors such as seeking social support (Segrin et al., 2016). Our proposed direct effect in the mediation model (H1), aligns with this theoretical framework. Interpersonal communication apprehension, defined as “an individual’s level of fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” (McCroskey, 1977, p. 78) can be characterized as a deficit in social skills, given that it is linked to lower relational quality with others and lower levels of social adaptation (Blume et al., 2013). Indeed, Allen and Bourhis’ (1996) meta-analysis showed that communication apprehension is consistently linked to lower communication quality and quantity. Thus, apprehensive individuals likely experience difficulties socializing with others, and therefore, in line with the theoretical tenet, we posit a positive direct association between interpersonal communication apprehension and loneliness (H1).

The social skills deficit vulnerability model (Segrin et al., 2016) posits that the inability to garner social support mediates the direct link between low social skills and mental health. Here, we extend this theoretical framework by investigating how psychological factors can mediate the link between social skills and mental health. Specifically, we draw the basic psychological needs theory – a sub theory of social determination theory – and argue that low social skills are linked to mental health issues through lower levels of satisfying one’s basic psychological needs. The basic psychological needs theory postulates that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are essential needs for human development, adjustment, and overall flourishing (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Vansteenkiste et al. (2020) define autonomy as “a sense of integrity as when one’s actions, thoughts, and feelings are self-endorsed and authentic” (p. 3). Individuals who lack autonomy often feel a sense of pressure to do unwanted things (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Competence is defined as a sense of mastery and skill, and having the ability to use one’s skills in everyday life. Those who lack competence often feel helpless and a sense of failure (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Last, relatedness is defined as an “experience of warmth, bonding, and care, and is satisfied by connecting to and feeling significant to others” (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020, p. 3).

According to the basic psychological needs theory, fulfilling these psychological needs are crucial for happiness and thriving (Ryan, 1995; Sheldon and Hilpert, 2012). Indeed, research shows that increased perceptions of basic psychological needs is related to increased mood and physical symptoms (Ryan et al., 2010). In essence, this theory contends that satisfying basic psychological needs is crucial in allowing individuals to grow, thrive, and feel intrinsically motivated toward life goals (Ryan, 1995; Sheldon and Hilpert, 2012). Thus, aligned with this theoretical principle, our model posits three paths: one from each basic psychological need to loneliness (H3).

Although an abundance of research employing this theory shows links between each need and outcomes related to well-being and thriving, relatively less research has examined what Vansteenkiste et al. (2020) characterize as need relevant conditions for attaining the basic psychological needs. Vansteenkiste et al. (2020) argue that one of the critical ways to expand the basic psychological needs theory is to more fully investigate factors that might promote, or disrupt, feeling competent, autonomous, and related to others. We answer Vansteenkiste et al.’s (2020) call in part by postulating that interpersonal communication could be a relevant characteristic that impedes one’s ability to attain competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Overall, our hypothesized model integrates the theoretical principles of the social skill deficit vulnerability model and the basic psychological needs theory to show how interpersonal communication apprehension is linked to loneliness through basic psychological needs. The section below elaborates on the specific arguments for the associations between interpersonal communication apprehension and each basic psychological need.

Interpersonal communication apprehension and basic psychological needs

We postulate that interpersonal communication apprehension will be negatively associated with each basic psychological need (H2 in the model). Communication apprehension is characterized by behaviors such as avoidance and communication disruption. Apprehensive individuals often regret and ruminate about their behaviors in social interactions (McCroskey, 1984). Moreover, apprehensive individuals are also perceived as less competent by others (McCroskey, 1982). Thus, it seems that communication apprehension should be related to lower levels of competence and autonomy. As mentioned earlier, autonomous people typically feel in control and confident with their own thoughts and actions. Given that communication apprehension is related to self-doubt and rumination over social behaviors, we argue that there will be a negative association between these variables. Principles from the looking glass self (Tice, 1992) suggest that when people perceive apprehensive people as less competent, they are more likely to perceive incompetence in themselves. Tice (1992) showed that people are more likely to internalize and magnify public interpersonal behaviors compared to private behavior. Additionally, Deci and Ryan (2000) argue that competence occurs when people feel comfortable and content in their social lives. Conversely, apprehensive people are more likely to find themselves in adverse and difficult social roles, because the nature of communication apprehension is fear and anxiety for social situations. Finally, we also expect apprehension to be negatively associated with relatedness. Past research shows that communication apprehension is related to deleterious relational factors such as a lack of family cohesion, expressiveness, and lower parental acceptance (Hsu, 1998). Moreover, communication apprehension is linked to lower levels of both communication quality and quantity (Allen and Bourhis, 1996). As Emmers-Sommer (2004) explains, communication quality and quantity are both critical to close relationships because they are positively associated with relational closeness, intimacy, and satisfaction. Thus, we posit that communication apprehension will be linked to lower levels of relatedness.

Methods

Procedures

The data for this study were part of a larger study on the links between interpersonal communication and psychosocial health. Participants were recruited from introductory psychology courses at a large university in the Mountain West. Potential participants signed into a research participation portal and could read the purpose of the study before deciding to participate. There was a link to an online survey where participants could complete the survey at their own convenience. The survey included measures on basic psychological needs, loneliness, and communication apprehension, as well as measures of humorous communication, cognitive flexibility and others. People had to be 18 years or older to participate. Participants received course credit for completing the survey. The survey took roughly 15 min to complete and all procedures were IRB approved.

Participants

In total, 406 participants completed the survey. Most participants identified as female (N = 297), whereas 108 participants identified as male, and 1 participant identified as gender non-conforming. Participants ranged in age from 18–58 years old (M = 20.34, SD = 4.53). The ethnicity reports were as follows: 380 reported White/Caucasian, 3 reported Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 5 reported Native American, 4 reported Black/African American, and 10 reported other.

Measures

Interpersonal communication apprehension

We employed the interpersonal communication apprehension subscale of the Personal Report of Communication Apprehension scale (McCroskey, 2005). These 6 items (e.g., “Ordinarily I am very tense and nervous in conversations.”) were rated using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Higher reports indicate higher levels of interpersonal communication apprehension (α = 0.88, M = 2.78, SD = 0.81).

Basic psychological needs

Each of the three basic psychological needs were measured with the Basic Psychological Needs Scale (Deci and Ryan, 2000). The 7 items for autonomy (e.g., “I feel like I am free to decide for myself how to live my life.”), the 6 items for competence (e.g., “People I know tell me I am good at what I do.”), and the 8 items for relatedness (e.g., “I consider the people I regularly interact with to be my friends) were all rated using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The univariate statistics for each subscale are as follows; autonomy: (α = 0.78, M = 3.51, SD = 0.69), competence: (0.83, M = 3.53, SD = 0.77), relatedness: (0.89, M = 3.88, SD = 0.78).

Loneliness

We measured loneliness with the three item version of the UCLA loneliness scale (Russell et al., 1980). The items (e.g., “How often do you feel you lack companionship?”) were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always) (α = 0.88, M = 2.32, SD = 0.96).

Results

Table 1 shows the zero-order correlations among the variables in this study. We tested our hypothesized model with Hayes’ (2022) PROCESS 4.2 Macro for SPSS. We employed model 4 of the macro for this analysis in order to test simultaneous parallel mediating effects from interpersonal communication apprehension to loneliness. The output produced coefficients from communication apprehension (X) to loneliness (Y; c’ path) while controlling for the three mediating variables. The macro also produced associations from interpersonal communication apprehension (X) to all three mediators: autonomy (M1; a1 path), competence (M2; a2 path), and relatedness (M3; a3 path). Next, this analysis showed effects from each mediator: autonomy (M1; b1 path), competence (M2; b2 path), and relatedness (M3; b3 path), to loneliness (Y). Finally, the analysis tested for indirect effects from fear of interpersonal communication apprehension (X) to loneliness (Y) each basic psychological need (ab paths). The mediating variables act as control variables for each other in the analysis. The macro generated 95% bias corrected and adjusted confidence intervals (CI). CIs that do not include zero denote significant indirect effects.

We first tested the direct effect from interpersonal communication apprehension to loneliness (H1). In support of our first hypothesis, the results showed a significant positive relationship between interpersonal communication apprehension and loneliness (B = 0.43, SE = 0.05, t = 8.06, p < 0.001). Next, we proposed that interpersonal communication apprehension would negatively associate with each basic psychological need (H2). The results showed a significant negative association from interpersonal communication apprehension to autonomy (β = −0.31, SE = 0.04, t = −6.50, p < 0.001), competence (β = −0.31, SE = 0.04, t = −6.63, p < 0.001), and relatedness (β = −0.28, SE = 0.05, t = −5.76, p < 0.001). Thus, H2 was fully supported. Hypothesis three posed that there would be negative associations between each psychological need and loneliness. The results showed that autonomy (β = −0.12, SE = 0.11, t = −1.55, p = 0.12) and relatedness (β = −0.001, SE = 0.10, t = −0.03, p = 0.97) were not significantly linked to loneliness. However, there was a significant negative association between competence (β = −0.17, SE = 0.09, t = −2.52, p = 0.012) and loneliness. Thus, H3 was partially supported. Last, we tested the indirect associations between interpersonal communication apprehension and loneliness through each basic psychological need. Below we report the completely standardized indirect effect of each mediation path, and the standardized errors and confidence intervals. There was a significant positive indirect effect from interpersonal communication apprehension to loneliness through competence (β = 0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI: 0.006, 0.11). The indirect effects from interpersonal communication apprehension to loneliness through autonomy (β = 0.04, SE = 0.03, 95% CI: −0.01, 0.10) and relatedness (β = 0.001, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: −0.04, 0.05) were not significant. Thus, H4 was partially supported.

Discussion

Guided by a theoretical integration of the social skill deficit vulnerability model and the basic psychological needs theory, the goal of this study was to investigate how autonomy, competence, and relatedness mediate the link between interpersonal communication apprehension and loneliness. Our results showed that interpersonal communication apprehension was linked to each basic psychological need. However, only competence significantly related to loneliness in the mediation model, and it was the only significant mediating variable. Given that each mediator was run simultaneously in order for them to act as control variables for each other, our results point to the significance of competence in the link between interpersonal communication apprehension and loneliness. Below we discuss the results from our model and the practical and theoretical implications of our findings.

One of the main goals of this study was to examine how interpersonal communication apprehension could impede one’s ability to attain each basic psychological need. The results showed that interpersonal communication apprehension was negatively related to all three basic psychological needs. Vansteenkiste et al. (2020) argue that individuals who lack competence often feel frustrated and ineffective when their skills are lacking. We argue that people experiencing interpersonal communication apprehension might feel unskilled socially and thus perceive that they have lower levels of general competence in their everyday lives. Moreover, people who lack autonomy often feel pressure to do and act in ways that feel unnatural or unwanted (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Thus, it is reasonable to argue that apprehensive individuals may feel pressure to perform in social settings in ways that are incongruent to their wants and needs. Interpersonal communication apprehension may be linked to lower basic psychological needs because apprehensive individuals have more difficulties managing positive and high quality social relationships (Hsu, 1998). Thus, apprehensive people could perceive lower levels of general relatedness because apprehension inhibits their ability to initiate and maintain quality relationships (i.e., relationships characterized by cohesion, self-disclosure, and intimacy). Moreover, as Segrin et al. (2016) argue, people with low social skills are more vulnerable to distress. Thus, it is logical to reason that lower social skills would also relate to difficulties attaining key psychological needs. Thus, it seems that low social skills not only relate to increased distress, but also associate with lower levels of positive psychological factors. Our results here also extend the research on communication apprehension more specifically. As McCroskey (1982) explains, communication apprehension is associated with negative perceptions from others such as lower levels of general competence and credibility. Our study adds to this research and shows that communication apprehensions is also related to less positive self-perceptions (i.e., lower levels of credibility autonomy, and relatedness). It is possible that apprehensive individuals experience internalized stigma from their social apprehension and thus report lower levels of the basic psychological needs.

Furthermore, our results showed that competence was negatively linked to loneliness, and it also mediated the link between interpersonal communication apprehension and loneliness. Vansteenkiste and Ryan (2013) explain that competence is feeling effective when interacting in one’s environment. People who feel competent engage with their environment in prosocial ways. They experience increased intrinsic motivation for their behavior, and a sense of joy and astonishment (Vansteenkiste and Ryan, 2013). Moreover, when competence is higher, people feel high levels of overall well-being and higher self-esteem (Vansteenkiste and Ryan, 2013). As such, people who feel higher levels of competence are likely to relate to their external environment with positive and prosocial tendencies that could buffer them from increased loneliness. Hawkley and Cacioppo (2010) explain that loneliness is related to perceiving social threat when interacting with one’s environment (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Relatedly, loneliness is also associated with decreased self-regulation wherein people have difficulties meeting their personal and social goals (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). In other words, loneliness could potentially decrease social effectiveness because lonelier people might not regulate their thoughts and emotions to meet social norms as well as non-lonely people. Competence could help buffer people from loneliness because it helps to foster prosocial expectations for interacting with one’s environment. Rather than expecting increased social threat – a precursor for loneliness – competent individuals tend to feel effective and have a sense of overall well-being (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010; Vansteenkiste and Ryan, 2013). As such, one potential way to improve loneliness is to target people’s sense of general competence in their everyday lives.

Theoretically, our results extend the social skill deficit vulnerability model. As mentioned above, the social skill deficit vulnerability model claims that people with lower social skills are at risk for mental health distress because may have a more difficult time buffering themselves from stress. In other words, the model posits that socially unskilled people are unlikely to acquire social support and thus are at risk for mental health problems. The underlying assumption in the model is that low social skills are related to behaviors – or a lack thereof – that put people in socially vulnerable positions. Our results add to the theory to show that low social skills could also make people psychologically vulnerable to mental health issues. Feeling generally incompetent and ineffective in one’s social environment could reasonably relate to increased loneliness because loneliness is often brought on by expectations of difficult and negative interactions (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Given that competence was a significant mediator in the link between interpersonal communication apprehension and loneliness, it stands to reason that apprehensive people may also have cognitive tendencies that make them vulnerable to mental health distress.

There are several relevant limitations to this study when deducing implications from the results and designing future studies. First, this study is a cross-sectional design with a convenience sample. Thus, understanding causality among the variables is limited and longitudinal data are needed to parse out the temporal order of the variables. Moreover, this sample is largely White. As Taylor and Nguyen (2020) found, race is a significant moderator in the experience of loneliness and depression. Thus, a more representative sample is needed to increase the generalizability of our findings. Future research should also examine other psychological and cognitive variables that might mediate the links between communication skills and mental health outcomes. Another avenue of future research could examine how other communication constructs, such as conflict skills and self-disclosure, relate to the three basic psychological needs. Overall, research in this area can further build upon the links between interpersonal communication and human psychological needs.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are confidential for this study per the IRB protocol. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to dGltLmN1cnJhbkB1c3UuZWR1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board – Utah State University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. RE: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, M., and Bourhis, J. (1996). The relationship of communication apprehension to communication behavior: a meta-analysis. Commun. Q. 44, 214–226. doi: 10.1080/01463379609370011

Blume, B. D., Baldwin, T. T., and Ryan, K. C. (2013). Communication apprehension: a barrier to students’ leadership, adaptability, and multicultural appreciation. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 12, 158–172. doi: 10.5465/amle.2011.0127

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The" what" and" why" of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Emmers-Sommer, T. M. (2004). The effect of communication quality and quantity indicators on intimacy and relational satisfaction. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 21, 399–411. doi: 10.1177/0265407504042839

Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 40, 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional Process analysis: A regression-based approach, vol. 3. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hsu, C.-F. (1998). Relationships between family characteristics and communication apprehension. Commun. Res. Rep. 15, 91–98. doi: 10.1080/08824099809362101

McCroskey, J. C. (1977). Oral communication apprehension: a summary of recent theory and research. Hum. Commun. Res. 4, 78–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00599.x

McCroskey, J. (1982). Oral communication apprehension: A reconceptualization. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 6, 136–170. doi: 10.1080/23808985.1982.11678497

McCroskey, J. C. (1984). “The communication apprehension perspective” in Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension. eds. J. A. Daly and J. C. McCroskey (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage), 13–38.

McCroskey, J. C. (2005). An introduction to rhetorical communication. 9th Edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Office of the Surgeon General (OSG) (2023). Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: The U.S. surgeon General’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., and Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA loneliness scale: concurrent and discriminate validity evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 39, 472–480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. J. Pers. 63, 397–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x

Ryan, R. M., Bernstein, J. H., and Brown, K. W. (2010). Weekends, work, and well-being: psychological need satisfactions and day of the week effects on mood, vitality, and physical symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 29, 95–122. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.1.95

Schermer, J. A., and Martin, N. G. (2019). A behavior genetic analysis of personality and loneliness. J. Res. Pers. 78, 133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2018.11.011

Segrin, C., and Flora, J. (2000). Poor social skills are a vulnerability factor in the development of psychosocial problems. Hum. Commun. Res. 26, 489–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00766.x

Segrin, C., McNelis, M., and Swiatkowski, P. (2016). Social skills, social support, and psychological distress: a test of the social skills deficit vulnerability model. Hum. Commun. Res. 42, 122–137. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12070

Sheldon, K. M., and Hilpert, J. C. (2012). The balanced measure of psychological needs (BMPN) scale: an alternative domain general measure of need satisfaction. Motiv. Emot. 36, 439–451. doi: 10.1007/s11031-012-9279-4

Taylor, H. O., and Nguyen, A. W. (2020). Depressive symptoms and loneliness among black and white older adults: the moderating effects of race. Innov. Aging 4:igaa048. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igaa048

Tice, D. M. (1992). Self-concept change and self-presentation: the looking glass self is also a magnifying glass. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 435–451. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.435

Vansteenkiste, M., and Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 23, 263–280. doi: 10.1037/a0032359

Keywords: communication apprehension, basic psychological needs, loneliness, social skills, mental health

Citation: Curran T and Elwood RE (2024) A theoretical integration of the social skill deficit vulnerability model and social determination theory to examine young adult loneliness. Front. Commun. 9:1491806. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1491806

Edited by:

Sean J. Upshaw, The University of Texas at Austin, United StatesReviewed by:

Bryan Abendschein, Western Michigan University, United StatesGrzeorz Pajestka, University of Opole, Poland

Copyright © 2024 Curran and Elwood. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Timothy Curran, dGltLmN1cnJhbkB1c3UuZWR1

Timothy Curran

Timothy Curran Rebecca E. Elwood

Rebecca E. Elwood