95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 06 January 2025

Sec. Advertising and Marketing Communication

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1489893

Mass communication in the We Media era has redefined China's rural virtual community and transformed the representation of the female body in the countryside. Using research methods such as literature review, case studies, and content analysis, this study adopts perspectives from the sociology of the body and feminist media studies to explore how female microcelebrities and social media influencers (SMIs) use their bodies to present authentic rural life. The research highlights their significant roles in marketing the countryside, fostering idyllic imaginations for mass audiences, and supporting rural revitalization. Focusing on prominent examples such as Li Ziqi, we argue that female microcelebrities endorsed by both the state and netizens contribute to rural marketing by promoting web traffic, agricultural products, and stronger idyllic imagery, thereby advancing China's rural revitalization efforts.

With the development of mobile internet and the popularization of smartphones, mobile short videos that last < 5 min have been universally regarded as a new trend and significant commercial prospect (LaRose and Eastin, 2024; Livingstone, 2008). The 53rd Statistical Report on Internet Development in China revealed that female mobile Internet users had reached 547 million, with short video users accounting for 95.5%, and rural mobile Internet users reaching 326 million, which contributed to 29.8% of Chinese total netizens by December 2023 (China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2024). The Research Report on the Development of Short Video Frequency in China (2023) revealed that the market scale of China's short video industry had reached nearly 300 billion yuan (RMB) (41,704.8 million US dollars) (China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2023). Social media and e-commerce have impacted the social lives of 47 million young rural women in China, affecting and changing their rural lives and career trajectories (CSM Media Research, 2023). It was also reported that more than 1 billion new TikTok rural videos were uploaded in 2023, with a broadcast volume of 2.4 trillion and over 79 thousand rural creators with million fans. This led to 4 billion yuan (RMB) (561.5 million US dollars) in payment transactions for rural tourism (Chen, 2023). The mobile Internet and digital media have caused significant, intense, and wide-ranging cultural changes in China, resulting in a media spectacle where many emotional structures (Williams, 1961, 1975, 2011) are superimposed and transformed (Zeng, 2024). On account of the idea that “digital media may encourage the young generation to shape their new behavioral patterns and structures of feeling” (Zeng and Wang, 2024: 168), the study focuses on discussing the attributes of mobile short videos and female microcelebrities in the Chinese countryside and their impact on the virtual community, particularly the female celebrities' body exhibition and the mobile netizens' idyllic imagination.

Driven by the rapid development of smartphones, mobile Internet, and 4G technology, mobile short video platforms such as TikTok, Kuaishou, Miaopai, Meipai, and Tencent Micro View have seen a dramatic increase in users in China, akin to the widespread youth engagement with YouTube videos in the West (Alter, 2017). Mobile media technologies have been moving toward a dynamic and video-oriented path from text to “picture + text” and then to audio-visual short videos (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., 2014). Meanwhile, the visual and media cultures have gradually transitioned from the text-centered to image-centered era to the era of short video. Gibbs is considered to be one of the first scholars to study short videos in the world. In his study, Short Form May Be Long-Tail for Mobile Videos, he delved into various functions of short videos and pointed out that mobile short videos would quickly occupy a leading position in the media field (Gibbs, 2007). Different from other cyberspaces, including WeChat, QQ, BBS, blogs, and micro-blogs, mobile short video apps succeed in creating an “underclass carnival” atmosphere with lower gatekeeping thresholds and interactive imitation (Vasterman, 2018) by recording the real lives of the non-professional individuals, with their unique characteristics of low threshold and easy operation. Driven by modern communication technologies, the spectacle society has been reshaped into Spectacle Society 2.0 in the mobile social media environment, such as We Media, in today's digital world (Bowman and Willis, 2003; Willis and Bowman, 2003).

On the whole, mobile short video apps provide a platform where users play the part of the intermediary and cultural debugger of spectacle circulation by collecting, reproducing, re-distributing, and judging the spectacle (Purusottama and Trilaksono, 2024). In Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Continuity and Change in the Cathedrals of Consumption, Ritzer believed that spectacle is a dramatic public display in the disenchanting process of dispelling mystery and attraction, and new means of consumption create the spectacle through implosion, time, and space (Ritzer, 2010). The best enchantment of the spectacle at present performs itself on the mobile short video app platforms, including the body display of skills and entertainment, as well as primitive things of rudeness and violence.

In the wake of the mobile web and the development of We media in China, short videos have entered a period of rapid growth, especially in 2017, often regarded as the “first year of short video.” According to the CSM User Value Research Report on Mobile Short Videos, Wi-Fi-enabled short videos have become the most widely consumed and engaging video format, surpassing traditional television and Internet videos in usage and viewer loyalty (Huang, 2023).

If traditional media, such as official newspapers, television, and radio, represent cultural hegemony, We media can be described as presenting a relatively free and democratic “all citizens carnival.” In recent years, a wave of mobile short video platforms has emerged—such as TikTok, Kuaishou, Pear, Headlines, Volcano, and Watermelon—capturing the attention of users with their shorter duration, accessible content, simple production, and capacity for effortless entertainment.

These features have particularly resonated with Generation Z (born in the late 1990s), making this demographic a lucrative target audience (Alter, 2017).

In today's fragmented society, where spare time is broken into small intervals, short web videos have given rise to a booming market with immense commercial potential and a new online marketing spectacle (Mokhtari et al., 2018). In addition, in the era of mobile We media, the rapid growth of short videos has propelled numerous grassroots creators to Internet fame, fostering a distinctive microcelebrity culture (Senft, 2008).

Among these microcelebrities, female influencers have played a unique and significant role. As practitioners of poverty alleviation, promoters of the KOL (Key Opinion Leader) economy, and spokespeople for rural culture, they exemplify the unique and vital contributions of China's rural society (Lv, 2019).

Due to the digital gap (Rogers, 2001), the urban–rural divide, and cultural differences (Lerner, 1958), the public involvement of countryside inhabitants had never spread rapidly and evenly on a larger scale. In retrospect, the digital inequality and gap underwent two stages of unequal access to differentiated use (DiMaggio et al., 2004). With the popularity of smartphones and the reduction of mobile data usage charges, new technology power is shifting from elite groups to media users (Chaffee and Metzger, 2001), and the communication ability of smartphone users has greatly improved in the countryside. Young rural people combine vernacular and urban cultures, which portray the unique culture transfer strategy and logic in the mobile Internet era. For this reason, the binary opposition between the urban and rural has narrowed, and the power gap between them has been weakened (Ji, 2018). The past silent countryside inhabitants have been endowed with the power of Internet discourse and have become new members of the main force of content production in today's virtual space. Under the empowerment of We media technologies (Odunaiya et al., 2020), the subject of mobile short video presentation acts out the new-type body presence, and body narrative becomes the main means of self-presentation. In mobile short videos, all real everyday life may be imaged and symbolized, and the short video presenters' “back stages” of the private sphere gradually become the “front stages” when they shape their idealized image. For short video selfies and publishers, the separation between the “front and back stages” and “back stages” has diversified, particularly the scene resolution in female short videos, most frequently back into the front, back transparency, and back resolution. The body, especially the female body, has become the most precious, beautiful consumer goods in consumer society and gradually materialized and formed a consumer code.

In 2017, to accelerate rural modernization and promote China-style modernization by 2050, the central government of China proposed the national strategy of Rural Revitalization, which aimed to eliminate rural poverty, employ Internet + agriculture and countryside, increase the farmers' income through multiple industries, and inherit and develop Chinese farming civilization. As an important part of the rural Internet application, the mobile short videos on the Chinese countryside have witnessed explosive growth and brought entrepreneurial opportunities to the new generation of farmers represented by returning migrant workers for entrepreneurship, namely rural microcelebrities. China's rural mobile short videos going viral can be regarded as a process of crowning from bottom grassroots to household microcelebrities. Under the lens and gaze of mobile short video producers, the distinctive countryside was diverse with its own characteristics in China (Liu et al., 2022). The mobile short videos on the Chinese countryside record various rural daily activities, including agricultural farming, river or sea fishing, cooking local cuisine, firewood cutting on the mountain, and characteristic marriages or funerals. The farmers, as mobile short video producers, do not need any professional skills to present themselves but in the way they prefer and reflect the authentic life of the photographed villagers, whose touching lifestyles are more likely to resonate with the nostalgic audience in a virtual pastoral community (Deng, 2020).

Furthermore, smartphone apps' inherent function of social intercourse further pushes the countryside to a larger circuses (onlooking) network, and then the farmers win the narrative discourse right by We media. Consequently, rural daily life has gradually entered the production system of new social media (Coelho et al., 2017), and the farmers show their unique life through the body narration. Through dynamic images, the enchanting body has become a unique visual consumption symbol.

Since 2018, with the rapid development of 5G wireless communication technologies and the rise of the Internet-driven Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs) economy, numerous rural female microcelebrities, epitomized by figures such as Li Ziqi, have emerged in significant numbers. Using Python Web Spider to analyze big data from rural short videos on YouTube, we discovered that by the end of 2021, there were over 800 popular farmer creators with more than 10,000 fan subscribers.

A large number of mobile short video creators, such as Housewife Jiumei (Sister Nine), Rural Xiaoqiao, Country Girl, Rural Senior, I'm Xiaoxi, Rural Akei, and My Countryside 365, have produced extensive content showcasing their working lives and local traditions. These videos serve as platforms for rural women's self-expression and We media entrepreneurship, generating revenue through e-commerce sales, advertising sponsorships, fan tips, and other revenue monetization strategies.

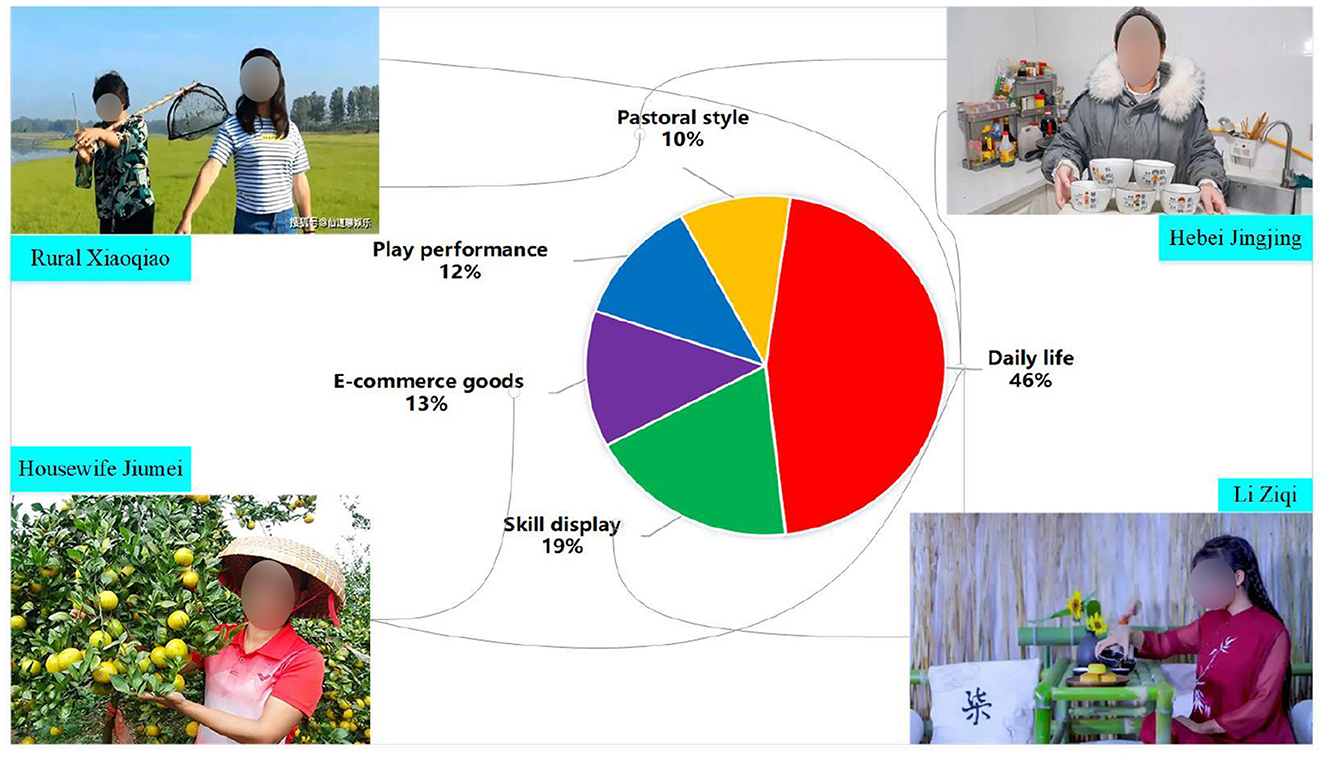

Based on their content orientation, mobile short videos featuring the Chinese countryside can be categorized into four primary types: 1. Rural Family-Oriented Videos: These focus on rural production and everyday life, with the creators' families and personal experiences as the primary inspiration. Rural Xiaoqiao exemplifies this category. 2. Farming Tillage-Oriented Videos: Centered on agricultural labor and farming activities, creators like Hebei Jingjing are notable representatives of this type (see Figure 1). 3. Agricultural E-Commerce-Oriented Videos: These focus on promoting and selling agricultural products online, often incorporating storytelling and demonstrations to attract buyers. Housewife Jiumei (Sister Nine) represents this category. 4. Food-Oriented Videos: Highlighting local culinary traditions and distinctive regional foods, these videos often appeal to a broad audience interested in gastronomy and culture. Li Ziqi is a prime example of this type.

Figure 1. Mobile short videos on the Chinese countryside in three categories (data sources: the screenshots left are from Rural Xiaoqiao's video homepage. 2023-11-18. https://www.ixigua.com/home/73091056211/; the middle screenshots from Hebei Jingjing's video homepage.2023-11-20. https://www.ixigua.com/home/63001086317/; the right screenshots from Housewife Jiumei's video homepage. 2022-08-10. https://space.bilibili.com/1919354157).

According to Statistics and Prediction of the Economic Scale of Chinese Internet Celebrities by Frost and Sullivan, the total scale of the Internet KOLs economy in China had reached 340 billion yuan (RMB) (47.7 billion US dollars) (China Commerce Industry Research Institute, 2020). In the Research Report 2016 on China's microcelebrities released by iResearch, microcelebrities were defined as individuals with personal charisma who go viral on the Internet by attracting numerous fans' attention on web media platforms, typically self-made microcelebrities (Gamson, 2011). TikTok and Kwai, typical representatives of mobile short video apps in China, have created numerous microcelebrities that are the public rather than the elite class, such as pop stars, government VIPs, or media reporters. In the above social context, the microcelebrities with distinctive symbol images have conspired with the mass consumption society (Gilardi et al., 2020), where microcelebrities have become a consumptive symbol (Abidin, 2018) for mobile short video spectators' psychological comfort and imagination. In this process, the microcelebrities also encourage spectators to consume mobile short videos by catering to their aesthetic taste and shaping their aesthetic ideals.

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy onto the female form, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role, women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness” (Mulvey, 1975, p. 9).

Women may build their self-awareness and achieve psychological empowerment through self-presentation on social media, which enhances their self-efficacy and a sense of control over their lives. Chinese rural women in the modern society of the spectacle have been striving to enter the public space with a new social identity. According to the statistics of iiMedia Research, female users in China used TikTok and Kwai more than males in 2020, accounting for 54.7%female and 22.6%male, 50.2%female and 22.2%male, respectively (iiMedia Research, 2021). Young women have become the backbone of producing rural short videos. On behalf of the general public at the bottom, rural women reconstruct the media image under the empowerment of mobile Internet technology and develop the cultural assets of the countryside from the female perspective. Through their body performance in short videos, they realized the new social identity of interactive social media. No longer the conventional body, according to Mulvey's male gaze and Butler's (1990) performative gender, the female body in the mobile short video has become a functional, commercialized, and symbolic body and a tool endowed with sexual desire and carnal desire.

With the prevalence of body consumption, more and more mobile Internet users are engaged in viewing and being viewed in mobile short videos. The male spectators increase the carnal consumption of female bodies while the female spectators indulge in imitating the same-gendered bodies. The aesthetic dreams created by the female microcelebrities in mobile short videos aggravate the alienation of the female body and promote the body to become the best-selling consumer goods. We have lived in a somatic society (Livingstone, 2003), where the body becomes a significant carrier and channel for conveying the individual's intentions. The body is unconsciously consumed and reproduced in the cultural field set by microcelebrities, which is viewed essentially as a kind of symbolic consumption (Fusar-Poli and Stanghellini, 2009). The performing body and expressing speech of microcelebrities have become the cultural capital by which the microcelebrities gain the media attention of the spectators on the mobile web. In Baudrillard's opinion, in post-modern society, the fully displayed beautiful body greatly satisfies the visual desire for the body and the social construction of the female body (Baudrillard, 2009). The mobile short videos in China today are a case in point, from the female microcelebrities treating ugliness as beauty to the top microcelebrity shopkeepers to PAPI Jiang, who became an Internet sensation for both her beauty and talent (Li et al., 2018). Summarizing and classifying the topics of female body performance in rural short videos, the study divided the research samples into the following five types of daily life: skill display, play performance, pastoral style, and e-commerce goods. Among them, the daily life videos that can reproduce rural lifestyles and pastoral images are the most popular, accounting for 46% of the total sample (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sample content types of rural female short videos (data sources: the upper left screenshots from Rural Xiaoqiao's video homepage. 2023-10-28. https://www.ixigua.com/home/73091056211/; the upper right screenshots from Hebei Jingjing's video homepage.2023-09-21. https://www.ixigua.com/home/63001086317/; the bottom left screenshots from Housewife Jiumei's video homepage. 2023-09-22. https://space.bilibili.com/1919354157; the bottom right screenshots from Li Ziqi's video homepage.2018-09-23. https://space.bilibili.com/19577966/).

Fundamentally, We media have changed how people express and communicate (Natale et al., 2019), and the body has been highlighted in information transmission. The body has gradually rid itself of the suppressed and obscured status in the traditional concepts and changed from the physical body's absence to the virtual body's re-presence. In mobile short videos, female microcelebrities present their private sphere on the front stage, becoming a visual spectacle of recreating the body symbol narrative (Song and Kim, 2019). The top female microcelebrity, Li Ziqi, had 14 million YouTube subscriptions and broke the Guinness World Record for “Maximum Subscriptions of YouTube Chinese Channel” on Feb. 2, 2021. On Nov. 17, 2024, China's two major central media, People's Daily Online and Xinhua Net, announced that Li Ziqi had been appointed as the honorary director of the Baidu Baike AI Intangible Cultural Heritage Museum.

On the one hand, she has created idealized selves in short mobile videos to conform to the aesthetic fashion of the public and to build some self-identity (Jung, 2019). On the other hand, the state and government departments exhibit cultural nationalism. They identify and recruit her as “a role model to bridge the urban-rural divide” in the commercialized cultural field (Liang, 2021).

As a rural female superstar of We media, Li Ziqi has successfully shaped the pastoral spectacle in rural China and told the world the fascinating stories of idyllic life and traditional Chinese culture. According to the YouTube platform data on 13th April 2022, Li Ziqi had 26.98 million microblog followers and 16.8 million subscribers on YouTube, far exceeding the leading Chinese official media audience of China Global Television Network (CGTN) and People's Daily. Her short videos take the ancient countryside in China as the theme and establish a kind of idyllic life with both a sense of reality and aesthetic imagination by showing authentic villages, traditional food, and folk crafts. Li Ziqi artistically reconstructs and recreates an idyllic pastoral life through mobile short videos on the Chinese countryside, which can activate and awaken the mass audience's feelings for the past idyllic pastoral life and reconstruct their new emotional structure of the imaginary pastoral life in the We media context (Zeng and Shi, 2020). On the one hand, Li Ziqi's short videos vividly depict the rural Shangri-la of the poetic pastoral life, natural paradise, and dreamy ancient culture, so the countryside in short videos may become a virtual utopia to escape worldly troubles (Li, 2022). On the other hand, the body has broken free from being bound and belittled. It is increasingly presented in short videos, live broadcasts, and other virtual social media, so the body in short videos may be visualized as the main subject of We media communication. Li Ziqi's rural labor presented in the short videos has become a consumption signification with strong personal enchantment to provide the sense of the reality of rural daily life and a cultural product to meet the aesthetic needs of the spectators (Bauman, 2000).

More specifically, Li Ziqi's short videos are a kind of post-emotional manipulation for the spectators. In the first place, Li Ziqi has captured the general anxiety of modern society and provided an emotional message serving as a medicine to relieve modern mental exhaustion; in the second place, Li Ziqi has established a new emotional structure for the spectators by showing Chinese traditional countryside and met the needs of modern nostalgia and curiosity for the past idyllic imagination. With exquisite composition and a leisurely pace of life, Li Ziqi's short videos are more similar to a pastoral documentary of production guides such as bread kilns, bamboo furniture, the four precious articles of the writing table, clothes making, whole sheep roasting, wine brewing, and soy sauce brewing, which gives the audience a pleasant visual massage. The research selects Li Ziqi's top five short videos on YouTube with the video themes of special preparations for the Spring Festival, river snail rice noodles, wine, hanging dried persimmons, and bamboo sofa (see Table 1). Full of poetic natural landscapes, carefree rural life, and the pure and warm world of Grandmother and Granddaughter, after facing the beautification of clips, close-ups, scene scheduling, and color rendering, Li Ziqi's short videos have successfully created a poetic idyllic scenery and aroused the scopophilia (a proclivity to view) of the mobile short video users in the social acceleration time. The poetic idyllic scenery constructed by Li Ziqi's short videos may release the urbanites' pressure and tension; meanwhile, the collective memory brought by Li Ziqi's short videos may awaken the spectators' individual memories (Assmann, 2015) and imaginative satisfaction.

The simple, natural, slow-paced, beautiful, and poetic rural life presented in rural short videos creates a strong contrast with the stressful and fast-paced urban lifestyle. For those living in the countryside, such short videos may evoke memories and nostalgia, fostering emotional connections and reinforcing cultural identity. For individuals people who have never experienced rural life, these short videos may fulfil their imagination and expectations of the countryside, sparking their curiosity and a desire for rural living and vernacular culture.

In terms of body performance in short videos, the spectacle of the body serves as a key mechanism through which these videos capture audience attention and preference, subsequently generating microcelebrity effects (Fusar-Poli and Stanghellini, 2009). The viral success of Li Ziqi's videos, for example, can be attributed to their ability to satisfy the audience's visual desires, alleviate mental stress, and provide cultural and emotional comfort. This phenomenon can be described as media massage and emotional communication.

The integration of body aesthetics with consumerism has evolved into a form of body narrative and consumption. American scholar John Fiske, who studied body media, argued that public satisfaction is experienced and expressed through the human body (Fiske, 2001). In McLuhan's perspective, media functions similarly to a physical massage, transmitting information to the brain and offering a sensory experience akin to muscle relaxation by a masseuse. This suggests that media influence is pervasive and penetrative, impacting individual, psychological, aesthetic, moral, ethical, political, economic, and social dimensions (Peters, 2017).

McLuhan's concept of “the medium is the massage” highlights the profound effect of media use on the physical and emotional states of mass audiences. Media consumption becomes a form of emotional enjoyment, akin to a soothing and refreshing experience, aligning in some ways with ideas of Infotopia (Information Utopia) (Sunstein, 2006) and Cyberutopia (Leggatt, 2017).

The emotional experience elicited by media operates on three interconnected levels: biological, cognitive, and cultural. From a biological perspective, emotions involve physiological changes in body systems, such as the autonomic nervous system, neurotransmitters, and hormones, which stimulate neural activation. Cognitively, emotion represents a conscious awareness of self and environmental stimuli. Culturally, emotion functions as a symbolic discourse, where individuals assign meaning and labels to specific physiological states (Turner, 2007).

Compared to emotional visual massage, mobile short videos focus on visual expression in the era of visual communication, so discourse massage is also indispensable. For discourse massage, Rimmon-Kenan distinguished two discourse paths of showing and telling: showing is considered as a direct representation of events and dialogues, wherein the narrator seems to disappear, and the reader is left to conclude what he/she sees and hears; on the contrary, telling is a representation mediated by the narrator (Rimmon-Kenan, 2002). While Li Ziqi's short videos focus on visual performance and visual message, they often need to cooperate with the necessary narrative discourse to enrich and improve the content displayed and construct the idyllic meaning in storytelling. What constitutes Li Ziqi's spontaneous appeal to the global virtual community? Her short videos not only show the exquisite and wonderful idyllic scenery but also tell the Chinese traditional lifestyles that modern urbanites have long been unfamiliar with, the Chinese traditional farming life in which man and nature, individuals and communities live harmoniously. For this reason, Li Ziqi's short videos perfectly present the aesthetic conception jointly created by the creators and audiences, as well as diversified communication, so that the spectators may acquire the relaxed artistic experience of ancient farming society in terms of senses and psychology.

At a deep cultural and identity level, Raymond Williams' concept of the structure of feeling offers a theoretical foundation for understanding the significance of Li Ziqi's short videos. The emergence and popularity of these videos are both timely and precise, as they address the widespread anxiety associated with modernity. By advocating for ancient lifestyles and preserving traditional values, Li Ziqi's work establishes a new cultural trend and emotional structure to alleviate modernity-induced discontent.

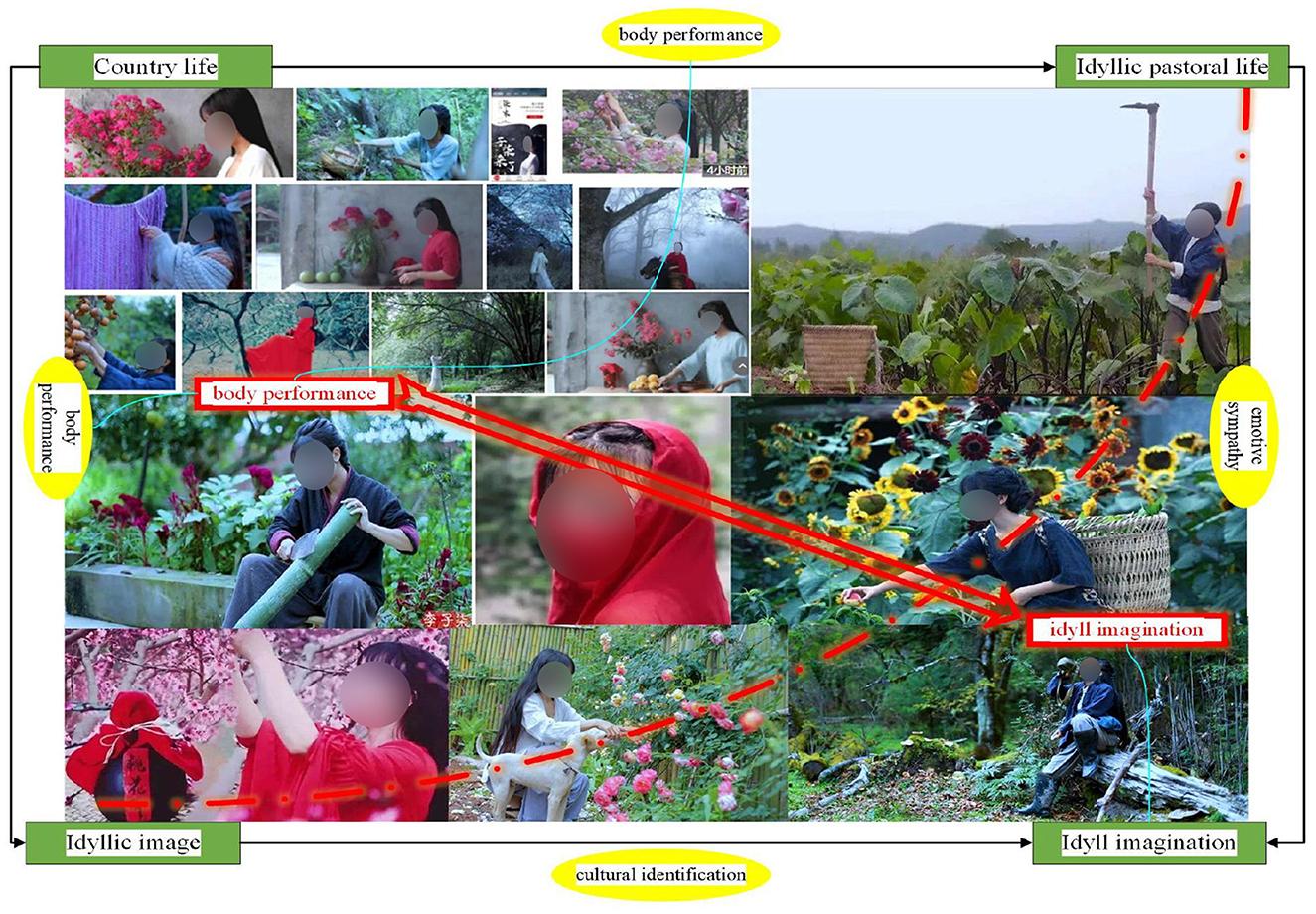

In Williams' view, every society has three cultural forms: the dominant culture, residual culture, and emergent culture. Among them, the emergent culture possessed the most vitality and revolutionary potential (Williams, 1977). To gain a more detailed understanding of pre-emergence, we need to explore the structure of feeling in literary and artistic works (Stasi, 2021). In the era of rapid development of We media, mobile short videos are not only the main media means of daily information dissemination and entertainment but also the emergent culture to display and activate traditional culture and arouse modern people's collective memories. Li Ziqi creatively combines the short videos with traditional Chinese culture to make an elaborate visual display of traditional rural spectacle and daily life in China, which may meet the double needs of accelerating contemporary audiences' cultural recall of traditional life and cultural criticism of modern society (see Figure 3). After being filtered by the We media, the simulative pastoral life becomes a super-reality and surreal existence and then becomes a visual spectacle or hyper-reality illusion in the consumer society. Its fundamental purpose is to meet the idyllic imagination of contemporary urbanites, although real rural life is not as beautiful as the pastoral life in the camera lens. At the same time, Chinese rural short videos provide audiences with multiple virtual identities, offering numerous opportunities to transcend their singular, real-world identities. Digital communication and virtual spaces fostered by these videos become sites for consuming rural culture as imagined by the public. These representations document rural life through meta-narratives, constructing a virtual social space centered on rural cultural identity. This space acts as a metaphor, reflecting the unique aesthetic values and lifestyles of rural society while reimagining them within a virtual framework.

Figure 3. Body performance and idyllic imagination of Li Ziqi's short videos (data sources: the screenshots are from Li Ziqi's video homepage. https://space.bilibili.com/19577966/).

Fundamentally speaking, whether it is the past pastoral literature or any rhetoric that views the countryside from a rural perspective, it has shifted people's attention to the fundamental issue of the division between the urban and rural and their institutional gap (Nadia, 2021). From the perspective of the structure of feeling, the rural short videos may be exploited as a cultural expression to scan the matrix relationship between culture and society (Sharma and Tygstrup, 2015). Rural short videos are not only associated with aesthetics or ideology but also a constantly changing social and cultural system with mobile communication and social networks (Subijanto, 2023). In Williams' viewpoint, the rise of a cultural trend is not unprovoked; it is the product of some common emotions in society, and this feeling structure is the culture of an era: it is the special and living result of all factors in the general organization (Williams, 1961; Higgins, 2001; Williams and Milner, 2010). Such virtual empowerment of We media has created a new discourse space for Chinese women and enabled them to achieve technological empowerment (Wei and Huang, 2023) and virtual visibility (Roux and Peck, 2019).

The rural life presented in Li Ziqi's short videos may be called Shangri-la, the empty or anxious netizens suffering from the spiritual crisis hanker after. Li Ziqi's short videos vividly show an ecological village that has not been contaminated by modern industry: pure sky, beautiful mountains, and rivers, clear streams, quiet villages, and even the traditional lifestyle and cultural forms preserved in modern society, all of which have become the boundless nostalgia that summons the short video viewers. Unlike the city's crowded and noisy living environment, the fresh air, slow rhythm, open fields, and simple atmosphere in the countryside may give people great relaxation and become an ideal place to relieve pressure (Chen et al., 2021). For many people living in the city, the Shangri-La life presented to them in short videos is also a longing for the countryside. In this way, some rural elements have been hyped by We media, coupled with some labels of “green ecology” and “pure nature.” Under the collusion of We media and the middle class, the realities of rural hardship are ignored. In the mobile short videos, the Chinese countryside has been built into a media utopia to meet the imagination of the middle class escaping from the city (Tian, 2017). “The fundamental point of electronic media is not to influence us through its content but to influence us by changing the spectacle geography of social life.” (Merovitz, 2002, p. 4). The rural motif on each short video platform is to arouse the spectators' yearning and longing by constructing an ideal rural spectacle to attract more short video users. However, this kind of rural spectacle oriented by the short video users' needs is bound to deviate from the real countryside.

However, Carey constantly warned that the extension of media technologies and the cultural rearrangement only remained ritual and narrative in the sense of anthropology, and the rural culture was no longer complete (Carey, 1992). The idyllic pastoral life in ancient styles constructed by Li Ziqi's short videos is not so much a reality as a sense of reality and a fantasy space (Li, 2020). The idyllic imagination, the audience's social imagination of the traditional rural world and rural life, originates from the inaccessibility of their reality and is induced by the mass media's aesthetic portrayal of the rural cultural atmosphere. The idyllic imagination with a clustering function may bring together the masses with common social attributes, cultural identities, and cultural memories and provide them with emotional solace and nostalgic imagination.

By exhibiting the daily life in the Chinese countryside, Li Ziqi's short videos create an idealized pastoral life that fulfils the audience's idyllic imagination of an antique and leisurely lifestyle. These videos allow viewers to project themselves into a pursuit of natural countryside living and an escape from the fast-paced demands of urban life, effectively showcasing their desires within an illusory space.

Therefore, the pastoral life portrayed in Li Ziqi's short videos is not a reflection of reality but rather a reaction to reality. This reaction reveals the inner longing of the audience. As Li Ziqi's agent said in an interview with China News Weekly: “Chinese people have a dream of idyllic spectacle, which is also her dream. Li Ziqi succeeds because she presents such a dream to everyone” (Mao, 2020).

The countryside depicted in these short videos does not represent the authentic rural experience but instead embodies a crafted rural illusion in an ancient style. This illusion satisfies the audience's yearning for idyllic landscapes and pastoral beauty, offering a dreamlike escape that resonates deeply with their imaginations.

“As I pick chrysanthemums beneath the eastern fence, my eyes fall leisurely on the Southern Mountain.” [Drinking Liquor·The Fifth by Tao Yuanming (365–427)] Through Li Ziqi's short videos, the idyllic life described by Tao Yuanming, China's first pastoral poet, may resonate with the audience for her body performance on rural romance, making the modern spectators feel leisurely and content in such a fast-paced life (Chen et al., 2021). In rural China, which has a long history of 5,000 years, most Chinese possess the rural hermit complex, allowing them to live a leisurely and contented rural life in the peaceful countryside. With a bamboo basket on her back, Li Ziqi picked vegetables in her own vegetable garden, followed by two garden dogs, and then lit the fire on the stove to cook with the smoke curling up and birds singing outside. The artistic conception has become a symbol of pastoral life and has been inherited by the Chinese vernacular culture in constructing the romantic pastoral life. However, “from disenchantment to reenchantment” of the rural life scape (Li, 2020), the rural life presented in Li Ziqi's short videos is a pseudo environment after make-up mode and the embodiment of aesthetic utopia (Jiao et al., 2022).

The New York Times positioned Li Ziqi as an “idyllic princess” during the isolation period of the COVID-19 epidemic. For audiences confined around the world, she became a reliable source of escape and comfort, embodying an idyllic fantasy of self-sufficiency and serenity (Tejal, 2020). Watching Li Ziqi's videos of rural landscapes often evokes a sense of nostalgia in viewers. Through the emotive connection and cultural identification forged between Li Ziqi and her audience (Quan, 2020), her body performance transforms into a vessel for the audience's idyllic imagination (see Figure 3).

In addition, acting as a new farmer rooted in the countryside and an enthusiastic practitioner of rural mass communication, Li Ziqi has successfully shaped a new image of rural women and become a prominent representative of rural We media bloggers. Social media, such as YouTube and TikTok, are giant and all-inclusive stages for reality show performance (Rodney, 2024), and body performance on the social media is a notable way for social media influencers (SMIs) endorsements (Zhang et al., 2024) and self-presentations (Dayan, 2013). People express themselves to society through body symbols (Lopez, 2020), express their experiences and feelings with information text anytime and anywhere, and present themselves with some images. As far as the female short videos themselves are concerned, the video production modes of Professional User Generated Content (PUGC) and User Generated Content (UGC) have endowed the female roles with multi-dimensional media images (Liao et al., 2019). With the help of the short video platforms, the female images have transformed from the construction of the other on the traditional media to the construction of the self on the We media, from the single image construction to multiple constructions, from flat written description to vivid audio-visual languages. Undeniably, for the female images of traditional Chinese media, such as the Chinese movie The Story of Qiu Ju, directed by Zhang Yimou in 1992, rural women were often constructed as the victims of being hurt, being loved, and fighting through the media, and marginal people in social groups, who were reduced to the objects of sympathy and scrutiny in mainstream media. From the perspective of gender inequality and an urban-rural binary gap in social power, rural female microcelebrities have received comprehensive discipline from the audience on their body, posture, and behavior while actively choosing their own visible dimensions and content to utilize and dissolve the mass gaze (Lonergan and Weber, 2019). In 1990, British sociologist Urry extended Foucault's “medical gaze” to the social phenomena of modern tourism, constructing the concept of “tourist gaze” (Urry, 1992) with reverse aspects of life, dominance, change, symbolism, and inequality (Urry, 1990, 2002; Urry and Larsen, 2011).

For the farmers and countryside under the “gaze” of modern audiences, rural female microcelebrities have initiated an “inward gaze” (Kahana, 2024) within the operational logic of We Media. By gaining sustained attention through short videos, they cater to the “modern gaze” of others, constructing a rural imagination that resonates with mobile Internet users. In the context of We Media communication, the personalized performances of female Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs) create diverse representations of femininity, contributing to the deconstruction of traditional female stereotypes (Lane, 2022).

Li Ziqi's short videos exemplify this dynamic by challenging male-dominated cultural narratives and stereotypes, particularly those surrounding rural women. Her content has inspired rural women to present themselves as independent and equal individuals, breaking free from conventional expectations and showcasing their agency in an evolving cultural landscape.

Today's mainstream scholars often interpret the bodies presented by female microcelebrities as self-orientalist bodies shaped by commercial discourse (Liang, 2022), disciplined bodies subjected to the gaze of others (Kahana, 2024), and spectacle-seeking bodies designed to generate economic flows in the attention economy (Li, 2020). In contrast to these perspectives, our research found that the bodies displayed by Chinese rural female microcelebrities, such as Li Ziqi, are authentic and living bodies deeply embedded in Chinese rural aesthetics and the practices of daily farming labor.

However, it is undeniable that Li Ziqi's short videos also represent an imaginary production of the oriental countryside. Furthermore, under the framework of national political affirmation and the mainstream discourse construction of We media identity, Li Ziqi's image has evolved from that of a commercial microcelebrity to a national cultural ambassador. The phenomenon of rural microcelebrities in China ushers in an era where “everyone can become a star” in the countryside.

Through the depiction of their daily physical presence and practices, rural female microcelebrities create short videos that not only showcase their bodies but also contribute to enhancing discourse power and improving the image of rural areas.

However, the rural idyllic life portrayed in these videos is a mediated construct shaped by We Media. Over time, rural short video content has transformed—from the earlier local vulgarity and exaggerated depictions to more refined portrayals of authentic rural life (Lu, 2019). Today, rural short videos increasingly feature high-quality, positive content. Many female microcelebrities, often referred to as new farmers, have even established e-commerce marketing channels, aligning with the goals of China's Rural Revitalization initiative.

Li Ziqi's viral success demonstrates not only the appeal of traditional Chinese culture but also reflects the new generation's conscious efforts to preserve and innovate within these traditions. Moreover, her success inspires new farmers to explore ways to build intellectual property (IP) brands by integrating traditional culture with the mobile Internet, paving the way for a unique blend of cultural heritage and modern digital commerce.

In conclusion, with the rapid development of the information industry and steady advancements in mobile Internet technology, rural China is no longer an isolated “information island” overlooked by the information age. The expansion of mobile Internet access into rural areas has been complemented by the Rural Revitalization Strategy, which introduced the policy of “Internet + agriculture, countryside, and farmers.” This initiative has played a crucial role in reducing information asymmetry between urban and rural areas, fostering agricultural and rural development.

In the era of mobile Internet, an increasing number of media carriers and expression channels facilitate cultural exchanges and emotional communication. Platforms such as mobile short videos provide mass audiences across diverse periods and regions the opportunity to overcome cultural barriers and bridge the information gap. Rural We Media has reshaped perceptions of authenticity and “otherness” in rural destinations, fostering a reverse flow of urban residents toward the countryside and creating a growing trend of rural tourism. This phenomenon has led to urbanites becoming new immigrants in rural areas, embracing rural living as a lifestyle.

Empowered by the Internet + e-commerce strategy and short video technology, rural women have found platforms to share their daily lives, showcase their talents, and build strong connections with their audiences. By leveraging live broadcasts and short videos, they promote and sell agricultural products, turning mobile Internet tools into reliable sources of economic empowerment. Live streaming, online shopping, and community recommendations reflect the evolution of cyber relationships and network communities (Romo et al., 2017) that increasingly occupy the private and leisure spaces of rural residents. These digital interactions have transformed traditional rural labor into modern income streams through online e-commerce and business ventures.

Looking ahead, mobile short videos are poised to further highlight the unique features of the countryside, spread vernacular culture, boost rural tourism, and drive economic growth in rural areas. However, achieving comprehensive rural revitalization requires addressing deeper challenges. The emergent “long revolution” includes ensuring the social identity, subjectivity, and equal status of rural women. Bridging the gap between the authenticity of rural life and its media spectacle will remain a critical research topic that warrants continued attention and in-depth exploration.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

MC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Resources, Visualization. YD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GQ: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. ZS: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YJ: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GH: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Anhui Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project [grant number AHSKY2023D041], Sichuan Provincial Key Research Base for Sichuan Cuisine Development Research Center Project [grant number CC24W06], Anhui Province Higher Education Quality Engineering “Excellent Course Project” [grant number 2022jpkc169], and Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China [grant number 21YJCZH252].

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abidin, C. (2018). Microcelebrity: Understanding Fame Online. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. doi: 10.1108/9781787560765

Alter, A. (2017). Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Alcazar-Corcoles, M. A., González-Blanch, C., Bendall, S., McGorry, P. D., and Gleeson, J. F. (2014). Online, social media and mobile technologies for psychosis treatment: a systematic review on novel user-led interventions. Schizophrenia Res. 156, 1, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.03.021

Assmann, J. (2015). Cultural Memory: Characters, Recollections, and Political Identity in early Advanced Culture. Beijing: Peking University Press.

Bowman, S., and Willis, C. (2003). We media:How Audiences Are Shaping the Future of News and Information.Reston. Reston, VA: The Media Center at the American Press Institute.

Chaffee, S., and Metzger, M. (2001).The end of mass communication? Mass Commun. Society 4, 365–379. doi: 10.1207/S15327825MCS0404_3

Chen, M., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., Wu, K., and Yang, Y. (2021). Rural soundscape: acoustic rurality? Evidence from Chinese countryside. Profes. Geograph. 73, 521–534. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2021.1880943

Chen, Q. (2023). How to Digest Massive Short Video Usage Among Rural Netizens? https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1786496542244790331&wfr=spider&for=pc. doi: 10.4236/chnstd.2023.121003 (accessed 28 December, 2023).

China Commerce Industry Research Institute (2020). Statistics and Prediction of the Economic Scale of Chinese Internet Celebrities. Available at: https://www.askci.com/news/chanye/20200319/1559091158236.shtml (accessed 19 March, 2020).

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) (2023). The 52nd Statistical Report on the Development of China's Internet. Available at: https://www.chinairn.com/news/20230828/160940597.shtml (accessed August 18, 2023).

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) (2024). The 53rd Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. Available at: www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2024/0322/c8810964.html (accessed 22 May, 2024).

Coelho, P. M. F., Correia, P. A. P., and Garcia Medina, I. (2017). Social media: a new way of public and political communication in digital media. Int. J. Interact. Mobile Technol. 11, 150–157. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v11i6.6876

CSM Media Research (2023). Huang Jingmei: Reshaping IPTV Value Perception in the Digital Age - Insights into IPTV Viewing Patterns in 2023. Available at: https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv27880887/ (accessed 22 November, 2022).

Dayan, D. (2013). Conquering visibility, conferring visibility: visibility seekers and media performance. Int. J. Commun. 7, 137–153.

Deng, J. (2020). Pastoral Nostalgia and Digital Media: A Case Study Exploring Nostalgia Communication in Li Ziqi's Online Short Videos. Upsar: Upsar University.

DiMaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Celeste, C., and Shafer, S. (2004). “From unequal access to differentiated use: a literature review and agenda for research on digital inequality,” in The Inequality Reader: Contemporary and Foundational Readings in Race, Class and Gender, eds. D. B. Grusky, and S. Szelényi (Boulder, CO: Westview Press), 355–400.

Fusar-Poli, P., and Stanghellini, G. (2009).Maurice Merleau-Ponty and the embodied subjectivity (1908-61). Med. Anthropol. Quart. 23, 91–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2009.01048.x

Gamson, J. (2011). The unwatched life is not worth living: the elevation of the ordinary in celebrity culture. PMLA 126, 1061–1069. doi: 10.1632/pmla.2011.126.4.1061

Gilardi, F., White, A., Cheng, S., Sheng, J., Song, J., and Zhao, Y. (2020). How online video platforms could support China's independent microfilm (short film) makers and enhance the Chinese film industry. Cultural Trends 29, 35–49. doi: 10.1080/09548963.2019.1697852

Huang, W. (2023). Reconstruction of rural social spectacle by new farmers' short videos from the perspective of media context. Radio TV J. 9, 106–109. doi: 10.19395/j.cnki.1674-246x.2023.09.029

iiMedia Research (2021). Data Analysis of the Short Video Industry: 54.7% of Chinese Female Users Will Use the Tiktok Short Video Platform in 2021. Available at: https://www.iimedia.cn/c1061/78440.html (accessed May 8, 2021).

Ji, G. (2018). Kwai in the sight of the combination of urban and rural cultures: an investigation based on the practice of the mobile Internet of Tu nationality youth in Qinghai. Ethno-National Stud. 45, 81–88.

Jiao, Y., Meng, M. Z., and Zhang, Y. (2022). Constructing a virtual destination: Li Ziqi's Chinese rural idyll on YouTube. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 22, 279–294. doi: 10.1080/15313220.2022.2096178

Jung, C. (2019). Why Does LiZiqi Outperform Most Chinese Vloggers on YouTube? Pandaily. Available at: https://pandaily.com/why-does-li-ziqi-outperform-most-chinese-vloggers-on-youtube/ (accessed 17 December, 2019).

Kahana, N. (2024). Providing a platform for self-transformation: existential authentication and the inward gaze. Ann. Tour. Res. 108:103815. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2024.103815

Lane, L. (2022). Strategic femininity on Facebook: women's experiences negotiating gendered discourses on social media. Feminist Media Stud. 22, 1–15.

LaRose, R., and Eastin, M. (2024). A social cognitive theory of Internet uses and gratifications: Toward a new model of media attendance. J. Broadcast. Elect. Media 48, 358–377. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4803_2

Leggatt, M. (2017). Cultural and Political Nostalgia in the Age of Terror: The Melancholic Sublime. London: Routledge.

Lerner, D. (1958). The Passing of Traditional Society: Modernizing the Middle East. Fredericksburg, VA: Free Press.

Li, H. (2020). From disenchantment to reenchantment: rural microcelebrities, short video, and the spectacle-ization of the rural lifescape on Chinese social media. Int. J. Commun. 14, 3769–3787.

Li, J., Zou, S., and Yang, H. (2018). How does “storytelling” influence consumer trust in we media advertorials? An Investigation in China. J. Global Mark. 32, 319–334. doi: 10.1080/08911762.2018.1562592

Li, X. (2022). How far is “daily life” from “reality”? The rural illusion in Li Ziqi's short videos. New Horizons from Tianfu 15,134–141.

Liang, D. (2022). The Imprint of Self Orientalization: Chinese Culture and Image Communication from Li Ziqi's Perspective. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University.

Liang, L. (2021). Consuming the pastoral desire Li Ziqi, food vlogging, and the structure of feeling in the era of microcelebrity. Global Storytell. J. Digit. Moving Imag. 1:2. doi: 10.3998/gs.1020

Liao, M., Zhang, J., and Wang, R. (2019). A dynamic evolutionary game model of microcelebrity brand eWOM marketing control strategy. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 33, 205–230. doi: 10.1108/APJML-11-2019-0682

Liu, M., Zhao, R., and Feng, J. (2022). Gender performances on social media: A comparative study of three top key opinion leaders in China. Front. Psychol. 13:1046887. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1046887

Livingstone, S. (2003). The Changing Nature of Audience: From the Mass Audience to the Interactive Media User. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/417/1/Chapter_in_ValdiviaBlackwell_volume_2003.pdf

Livingstone, S. (2008). Engaging with media –a matter of literacy? Commun. Culture Critique 1, 51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-9137.2007.00006.x

Lonergan, C., and Weber, R. (2019).Reconceptualizing physical sex as a continuum: are there sex differences in video game preference? Mass Commun. Soc. 23, 421–451. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2019.1654518

Lopez, L. (2020). Filmic gendered discourses in rural contexts: the Camino de Santiago (Spain) case. Sustainability 12:5080. doi: 10.3390/su12125080

Lu, W. (2019). Made in Taiwan: paratexts of Life of Pi and a dynamic sense of place. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 36,1–14. doi: 10.1080/15295036.2019.1566630

Lv, P. (2019). Path and value of “going viral” on rural We- media. Rural Econ. Technol. 30, 228–232.

Mao, Y. (2020). “Li Ziqi: My ideal life is to be carefree and self-sufficient,” in China News Weekly. Available at: http://www.inewsweek.cn/people/2019-12-30/8203.shtml (accessed 20 June, 2020).

Merovitz, J. (2002). Vanishing Regions: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press.

Mokhtari, M., Abdulrazak, B, and Aloulou, H. (2018). Smart Homes and Health Telematics, Designing a Better Future: Urban Assisted Living. Cham: Springer.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen 16, 6–18. doi: 10.1093/screen/16.3.6

Nadia, H. (2021). Feeling the structures of Québec's 2012 student strike at Concordia University: the place of emotions, emotional styles, and emotional reflexivity. Emot. Space Soc. 40:100809, doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100809

Natale, S., Bory, P., and Balbi, G. (2019). The rise of corporational determinism: digital media corporations and narratives of media change. Critical Stud. Media Commun. 36, 323–338. doi: 10.1080/15295036.2019.1632469

Odunaiya, O., Agoyi, M., and Osemeahon, O. S. (2020). Social TV engagement for increasing and sustaining social TV viewers. Sustainability 12:4906. doi: 10.3390/su12124906

Peters, J. D. (2017). “You mean my whole fallacy is wrong”: On technological determinism. Representations 140, 10–26. doi: 10.1525/rep.2017.140.1.10

Purusottama, A., and Trilaksono, T. (2024). Intermediary business models: using blockchain technology for intermediary businesses. Busin. Proc. Managem. J. doi: 10.1108/BPMJ-03-2024-0141. [Epub ahead of print].

Quan, D. (2020). From consumption of goods to consumption of symbols—analysis and views on Baudrillard's theory. J. Sociol. Ethnol. 2:1.

Rimmon-Kenan, S. (2002). Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics, Second Edition. London: Routledge.

Ritzer, G. (2010). Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Continuity and Change in the Cathedrals of Consumption, Third Edition. Newbury Park, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Rodney, D. (2024). The YouTube marketing communication effect on cognitive, affective and behavioral attitudes among generation Z consumers. Sustainability 12:5075. doi: 10.3390/su12125075

Rogers, E. (2001). The digital divide. Converg. Int. J. Res. We Media Technol. 7, 69–111. doi: 10.1177/135485650100700406

Romo, G., Medina, I. G., and Romero, N. P. (2017). Storytelling and social networking as tools for digital and mobile marketing of luxury fashion brands. Int. J. Interact. Mobile Technol. 11, 136–149. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v11i6.7511

Roux, S., and Peck, A. (2019). The commodification of women's empowerment: the case of vagina varsity. Discourse, Cont. Media 32:100343. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100343

Senft, T. M. (2008). Camgirls: Celebrity & community in the age of social networks. Int. J. Perf. Arts & Digital Media 8:21.

Sharma, D., and Tygstrup, F. (2015). Structures of Feeling: Affectivity and the Study of Culture. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Song, Y., and Kim, H. (2019). Brief analysis of body narrative and symbol symbolism in we media art. TECHART: J. Arts Imag. Sci. 6, 5–8. doi: 10.15323/techart.2019.2.6.1.5

Subijanto, R. (2023). From London to Bali: raymond Williams and communication as transport and social networks. Eur. J. Cultural Stud. 27:2. doi: 10.1177/13675494231152886

Tejal, R. (2020). The Reclusive Rood Celebrity Li Ziqi is my Quarantine Queen. New York: The New York Times.

Urry, J. (1990). The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage Publications.

Urry, J. (1992). The tourist gaze “revisited”. Am. Beha. Sci. 36, 172–186. doi: 10.1177/0002764292036002005

Vasterman, P. (2018). From Media Hype to Twitter Storm: News Explosions and Their Impact on Issues, Crises and Public Opinion. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Wei, X., and Huang, Y. (2023). Visible invisibility: empowering rural women through online We media. J. Chin. Women's Stud. 5, 73−84.

Williams, R., and Milner, A. (2010). Tenses of Imagination: Raymond Williams on Science Fiction, Utopia and Dystopia. Oxford: Peter Lang.

Zeng, L. (2024). The superposition of emotional structure: the dual empowerment of technology affordance and society visibility. J. Northwest Normal Univer. 6:1.

Zeng, Y., and Shi, J. (2020). From emotional massage to emotional structure: rural imagination under modern anxiety. J. Fujian Normal Univer. 37, 122–130.

Zeng, Y., and Wang, M. (2024). Reflection on the issue of emotional structure in the digital media era. Explorat. Free Views 1, 165−176.

Keywords: mobile short videos, Chinese countryside, We media, female microcelebrities, Li Ziqi, body performance, idyllic imagination

Citation: Chen MM, Dong Y, Zhang J, Qu G, Sun Z, Jiang Y and Hu G (2025) Body exhibition or idyllic imagination? Female microcelebrities in mobile short videos depicting the Chinese countryside. Front. Commun. 9:1489893. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1489893

Received: 04 September 2024; Accepted: 28 November 2024;

Published: 06 January 2025.

Edited by:

Naser Valaei, Liverpool John Moores University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Graham Murdock, Loughborough University, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Chen, Dong, Zhang, Qu, Sun, Jiang and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maichi Match Chen, Y2htYXRjaDIwMDBAeWVhaC5uZXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.