- 1Department of Communication Sciences and Public Relations, Faculty of Philosophy and Socio-Political Sciences, “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iași, Iași, Romania

- 2Department of Management, Marketing and Business Administration, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iași, Iași, Romania

Our article aims to investigate the factors, precisely motives for TikTok use, perceived ad intrusiveness, attitude toward advertising, ad credibility, ad value, and online flow experience, driving buying impulsiveness among Generation Z users on TikTok. We developed and analyzed a theoretical model using SmartPLS. We used a quantitative-based approach to collect data by surveying a convenience sample of 2406 online questionnaires. The results indicate that motives for TikTok use negatively affect perceived ad intrusiveness while positively affecting the online flow experience and ad credibility. Attitude towards advertising negatively impacts perceived ad intrusiveness, while attitude towards advertising positively influences ad credibility and value. Furthermore, ad credibility has a positive impact on ad value, which, in turn, positively influences online impulse buying. As such, adapted ad content leads to a positive attitude toward advertising, creating an optimal experience on the platform and a positive perception of ads regarding credibility and value.

1 Introduction

TikTok, a popular platform among Generation Z (also called Zoomers) users today, has become a significant social media player with a major increase in global advertising income. Our paper aims to investigate factors that drive buying impulsiveness among Generation Z users on TikTok. The research objectives are the following: (1) elucidate the circumstances in which flow experience culminates in impulse buying; (2) determine the most efficacious advertising tactics to elicit impulse purchases; and (3) comprehend how various motivations for utilizing TikTok impact advertising efficacy and flow experience. The research problem involves understanding which factors influence the online impulsive buying of Generation Z users on TikTok. Given the popularity of TikTok (Shi et al., 2022), especially among Generation Z users (Quintas-Froufe et al., 2024), researchers have shown increasing interest in this platform and this cohort (Ngo et al., 2024). Simultaneously, the complex interplay of factors influencing online impulse buying has captured the attention of both academics and practitioners (Han, 2023; Zhu et al., 2023; Gallin and Portes, 2024; Ngo et al., 2024; Nyrhinen et al., 2024). As new external and internal variables shape consumer behavior, including impulsive purchases, a need for updated theoretical frameworks has emerged (Feng et al., 2024).

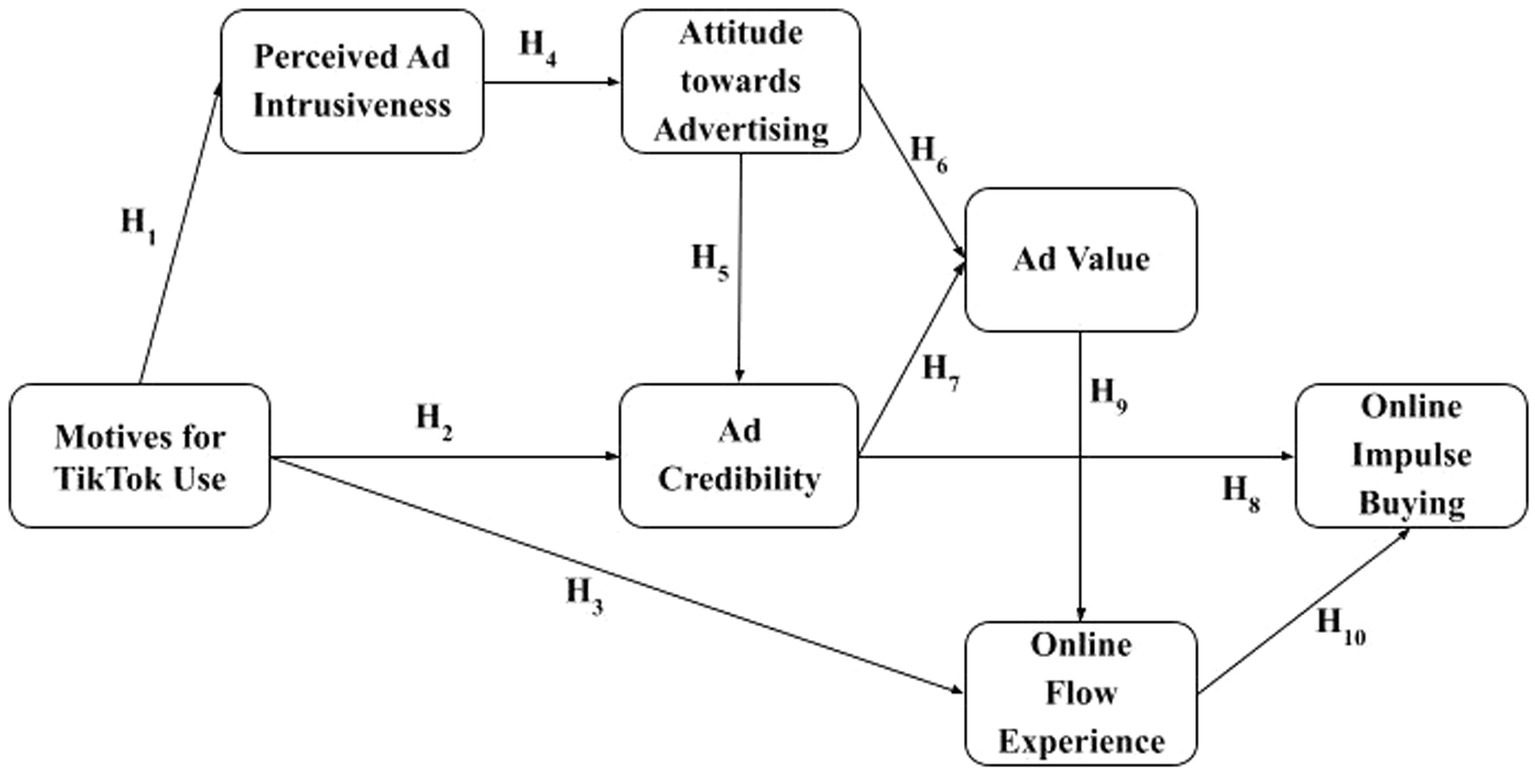

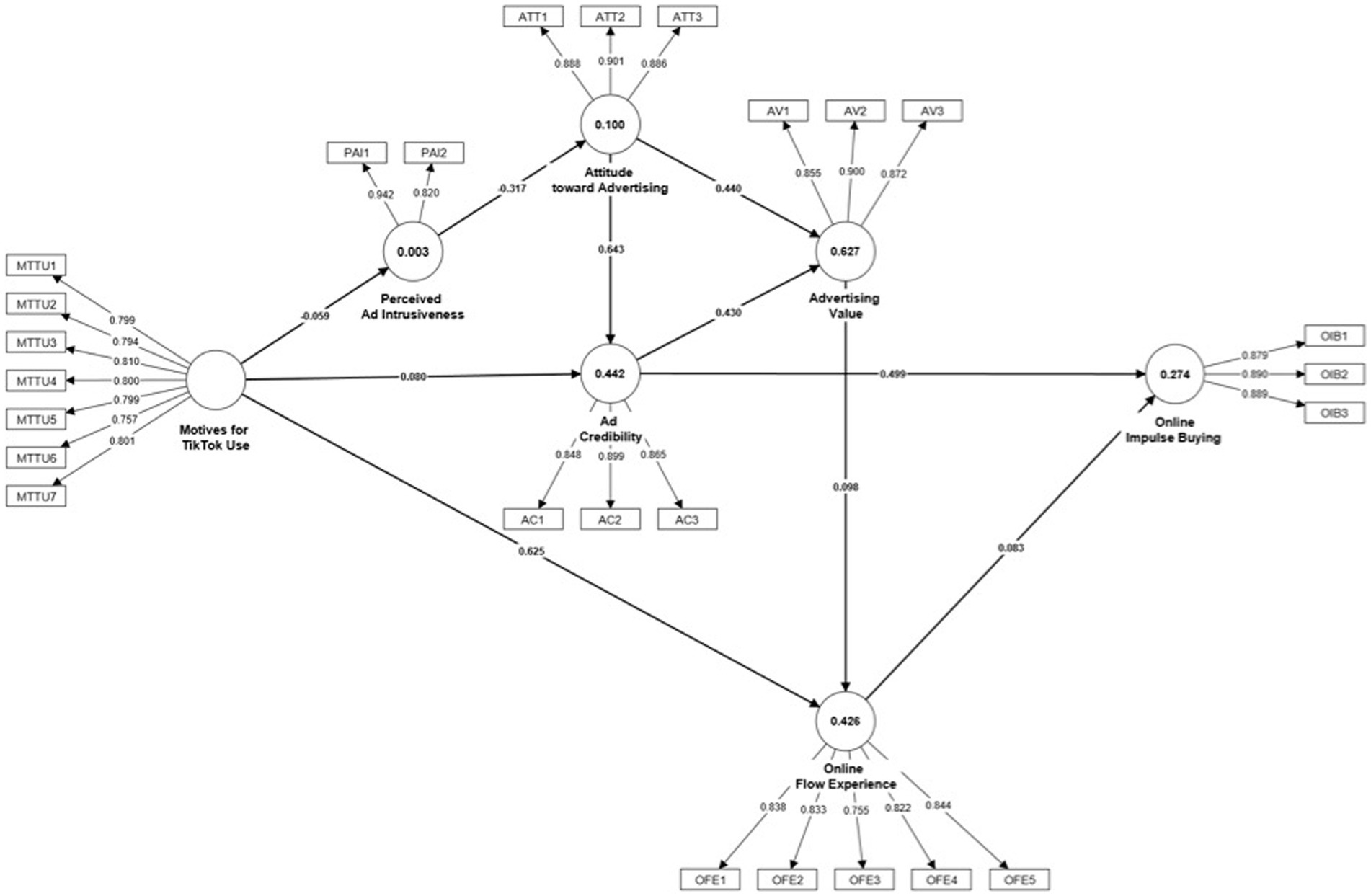

The initial assumptions of our study were that Motives for TikTok Use negatively influence Perceived Ad Intrusiveness and positively influence Ad Credibility and Online Flow Experience. Moreover, Perceived Ad Intrusiveness might have a negative influence on Attitude toward Advertising which we anticipate to be positively associated with Ad Credibility and to positively influence Ad Value. Ad Credibility is expected to positively influence Ad Value and Online Impulse Buying. We also anticipate Ad Value to exert a positive influence on Online Flow Experience and Online Flow Experience to exert a positive influence on Online Impulse Buying.

In the present paper, flow is known also as the optimal experience (Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre, 1989), while motivation is defined as a wish, a goal, a drive, or a desire (Maslow, 1943). Ad credibility refers to the “extent to which the consumer perceives claims made about the brand in the ad to be truthful and believable” (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989, p. 51). According to Redondo and Aznar (2018, p. 1609), “attitude toward advertising is a learned predisposition that individuals slowly develop as they perceive the advantages and disadvantages that advertising accrues to themselves and/or others in society,” inducing a favorable or an unfavorable predisposition. Intrusiveness leads to irritation and ad avoidance (Cortés and Vela, 2013; Redondo and Aznar, 2018; Frade et al., 2021; Niu et al., 2021; Lütjens et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023), while ad value is “a subjective evaluation of the relative worth or utility of advertising to consumers” (Ducoffe, 1995, p. 1). Finally, impulse buying is “a consumer’s tendency to buy spontaneously, unreflectively, immediately, and kinetically” (Rook and Fisher, 1995, p. 306).

This study aims to fill the theoretical gaps in the literature by evaluating the relationship between flow experience and impulse buying, the effect of advertising variables on impulse buying, and the influence of motives to use TikTok on advertising variables and online flow experience. This research is novel because the literature on business communication has not previously explored all of these associations. Also, the study provides for the first-time empirical evidence from an emerging market on the drivers of online flow experience and impulse buying on TikTok, highlighting the need to consider the key features of this phenomenon for different generational cohorts.

Previous research found a positive relation between the flow state and online impulse buying (Wu et al., 2020; Qu et al., 2023), motivation being an antecedent of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975). Also, researchers revealed a positive influence of ad value on purchase intention (Sharma et al., 2021) and a link between e-impulse buying and purchase intention (Goel et al., 2022). In wider contexts, researchers highlighted a positive relationship between ad value and credibility in advertising variables (Ducoffe, 1995; Kim and Han, 2014; Lin and Bautista, 2018; Abbasi et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021), while they found that irritation negatively impacts ad attitudes (Tran, 2017; Redondo and Aznar, 2018; Lütjens et al., 2022).

In particular, researchers suggest testing the relationship between the flow state and online impulse buying in specific online contexts (Wu et al., 2020; Qu et al., 2023). Despite its importance for Generation Z users, the relationship between Motives for TikTok Use and Ad Intrusiveness on TikTok remains unexplored. In this context, further in-depth investigation is necessary to understand the relationship between Motives for TikTok Use and Ad Credibility, as well as the relationship between Ad Value and Attitudes towards Advertising.

The manuscript is organized as follows: Section 1 introduces the current research’s contextual foundation. Section 2 presents the Frame of Reference and Theoretical and Conceptual Framework, the hypotheses, and conceptual model development based on a critical literature review. Section 3 details the data collection methodology and the procedure used to test the research hypothesis. Section 4 reports the analytical strategies and the study results. Section 5 contains a discussion of the main findings, relating them to previous work, presenting theoretical, research, and practical implications, further research directions, and limitations. Section 6 presents the study conclusions.

1.1 Background study

Due to their growth background (Liu, 2023) individuals in Generation Z are technology-savvy people (Dania et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023), using technology information systems in every aspect of their lives (Liu et al., 2023; Sillero Sillero et al., 2023). Therefore, capturing the attention of Generation Z, a promising consumer target (Amatulli et al., 2023), could yield substantial benefits, as they are active online users (Alves de Castro, 2023) and engage in online shopping (Alshohaib, 2024), comprising 30% of the world’s population (Liu, 2023). However, achieving these objectives presents multifaceted challenges, demanding innovative and nuanced marketing approaches.

Previous research either investigated how flow affects behavior intention (Chang and Zhu, 2012; Kim and Han, 2014; Pelet et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021; Hyun et al., 2022; Kim, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023) or how advertising variables relate to each other (Jung, 2017; Tran, 2017; Zarouali et al., 2017; Redondo and Aznar, 2018; Abbasi et al., 2021; Niu et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021; Alzaidi and Agag, 2022; Lütjens et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023). Online shopping is more prone to impulse purchases compared to traditional shopping (Wu et al., 2020; Dimara and Parahiyanti, 2024). Existing literature indicates that there is a link between perceived enjoyment and online impulse buying (Wu et al., 2020). In this context, Generation Z users’ perceived entertainment from social media usage (Wijaya et al., 2020) may influence online impulse buying.

TikTok had 1.5 billion monthly active users in 2023 (BusinessofApps, 2024). This platform has become deeply entrenched in the fabric of individuals’ experiences, as an ad on TikTok today could target about 13.6% of all human beings (DataReportal, 2023). In Romania, an important emerging market for the EU, TikTok recorded an advertising sales peak of $1.29 million in March 2023 (Statista, 2023). Almost 65% of Romanian TikTok users are aged between 18 and 24 (Start.io, 2023), corresponding to Generation Z users.

2 Frame of reference and theoretical and conceptual framework, research model

Studies from the literature have used various theories regarding factors driving impulsive buying among Generation Z users on TikTok. For example, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) explains the users’ adoption and utilization of technology, while the Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT) explores why people use media to fulfill their needs. The Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model posits that external stimuli, such as ads on TikTok, impact an individual’s internal state, such as emotions and attitudes, subsequently influencing their responses, such as impulsive buying. As a result, on TikTok, there is a complex interplay of factors driving buying impulsiveness among Generation Z users. This paper proposes a new model focused on Flow Theory, as the feeling individuals have when being totally engaged in the online environment enhances online impulse buying (Wu et al., 2020).

2.1 Flow theory

Flow, also known as “optimal experience” (Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre, 1989; Pelet et al., 2017), was first introduced and approached as a theoretical concept by Csikszentmihalyi (1975), defining it as a “holistic sensation that people feel when they act with total engagement” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, p. 36).

Many current studies view flow as a one-dimensional concept (Lavoie and Zheng, 2022; Obadă and Dabija, 2022). Researchers measure it with scales that have three, four, or eight items (Xu et al., 2021; Hyun et al., 2022; Kim, 2022; Zheng, 2023). As flow theory suggests, there is one underlying construct (Lemmens and von Münchhausen, 2023), and this paper’s authors also adopted the unidimensional measurement scale.

Defined by their seamless integration into daily life, social media platforms have become ubiquitous communication tools within the digital landscape. Staying connected is an important aim and benefit of social media use (Miranda et al., 2023). Research confirms that social media is a source of pleasure, also expressed as enjoyment (Pelet et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2022; Miranda et al., 2023; Roberts and David, 2023; Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2024). Thus, following Csikszentmihalyi’s (1975) study, researchers also adapted the flow concept for the social media context (Pelet et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021; Kim, 2022; Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2024).

Chang and Zhu (2012) argue that enhancing the flow users experience is crucial, as it significantly impacts their satisfaction on social networking sites. Several other authors (Kim and Han, 2014; Pelet et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2021; Hyun et al., 2022) supported the same idea, showing that flow, as part of the online experience, has significant positive effects and is a predictor of consumer purchase intention, suggesting that technological knowledge should be combined with flow aspects (Hyun et al., 2022); and flow also enhances social media regular use (Pelet et al., 2017) and online impulse buying (Wu et al., 2020).

Researchers delved into a diverse array of online environments and social media platforms. For example, Roberts and David (2023) conducted an examination and comparison of flow experiences reported on various social media platforms, highlighting that TikTok users experience higher levels of overall flow compared to Instagram users.

2.2 Hypotheses and conceptual model development

2.2.1 The motives for TikTok use and perceived ad intrusiveness

Motivation, a prerequisite of flow (Obadă, 2015; Obadă and Dabija, 2022), is defined as a wish, a goal, a drive, or a desire (Maslow, 1943; Obadă and Dabija, 2022). Social networking sites have undergone a continuous evolution since their inception (Shorter et al., 2022), driven by the creation and dynamic exchange of user-generated content (Pop et al., 2022). A common thread among social media platforms is the constant interaction and information exchange among users (Ren et al., 2023), including sharing about brands and products (Zhao and Chen, 2022), providing a dynamic means of socialization (Shorter et al., 2022). Social media platforms provide an ideal environment for creating, sharing, and consuming information, motivating people to share information for both informational and social reasons (Sharabati et al., 2022; Ren et al., 2023; Obadă and Dabija, 2022).

Online networking sites mirror the complex nature of social interaction through two distinct modes of engagement: active participation, which involves commenting, sharing, and messaging, and passive participation, which revolves solely around observing others (Khan, 2017; Obadă and Dabija, 2022). Thus, we anticipate witnessing an evolution in socialization patterns and communication styles as a result of the dynamic interplay between the complex nature of online participation and the continuous emergence of innovative technologies and trends (Shorter et al., 2022). Cultural differences also play a significant role, with some users from specific cultural spaces (e.g., Chinese and Malawian youth) prioritizing social motivations over others (e.g., UK users) and the motive of entertainment reflecting the globalized digital culture (Ndasauka and Ndasauka, 2024).

TikTok, a relatively new social media platform, has captivated a diverse spectrum of users, determined by a multitude of motives that drive engagement (Gu et al., 2022). Researchers are interested in understanding the motives for using TikTok, due to its success all over the world (Scherr and Wang, 2021). While passive participation on TikTok, which is very common, often involves simply consuming content, active participation is fueled by the desire to experience emotions of affect or amusement (Gu et al., 2022).

Particularly for TikTok, Omar and Dequan (2020) identified social interaction, self-expression, archiving, and escapism as motives and usage behavior predictors for the use of this platform. Scherr and Wang (2021) identified four categories of motives to use TikTok: trendiness, socially rewarding self-presentation, escapist addiction, and novelty. According to Han (2020), users have a positive attitude toward advertising on TikTok, preferring to watch ads on this platform, being influenced by the following latent variables: reliability and authenticity, user interaction, customer-build, user-friendliness, and entertainment emotion. TikTok ad content is easy to understand and transparent (Han, 2020). People have control over the displayed content thanks to personalized advertising. Generation Z users engage with adapted types of ad content (Wang et al., 2023) on TikTok. On this platform, users can ask and comment about the promoted products. As a result, one motive for using TikTok could be to find information about certain products, including ads.

Predominantly driven by user-generated contributions, social media is distinctive to traditional media, meaning that users tend to consider it their private space, leading to a sense of being invaded by advertising (Niu et al., 2021) as it interrupts a motivated, goal-directed behavior (Li et al., 2002; Niu et al., 2021). Lim et al. (2023) also revealed that perception of ad intrusiveness increases with high product involvement, which may be associated with motives to get involved.

Perceived ad intrusiveness was defined as the “psychological reaction to ads that interfere with a consumer’s ongoing cognitive processes” (Li et al., 2002, p. 39). As such, one of the advertising complaints is intrusiveness, as it interrupts consumers’ goals (Li et al., 2002). Researchers initially studied ad intrusiveness in traditional media, but they also explored it in mobile and online environments (Cortés and Vela, 2013; Lim et al., 2023). For example, perceived ad intrusiveness on mobile phones produces irritation, negatively affecting attitudes toward advertising (Cortés and Vela, 2013).

Unlike YouTube, TikTok users can easily skip ads. Ads on TikTok are short-form videos that prove to have the ability to be more sensory-rich and more vivid, capturing interest with what may be considered more valuable content (Li et al., 2023). This is a very convenient feature for TikTok users in Generation Z, consisting of tech-savvy (Dania et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023) adolescents and young adults with short attention spans (Qin et al., 2022). Users may accept the content as integrated with their goals and motives for visiting the platform, particularly considering their occasional inability to stop using it (Gu et al., 2022). Lütjens et al. (2022), on the other hand, noticed that the irritation effect may have lessened over time. This could mean that consumers are less sensitive to both positive and negative touchpoint stimuli. They think this is because users are becoming more used to new technologies in today’s digital world.

Despite the importance of understanding the relationship between motives for TikTok Use and Ad Intrusiveness on TikTok, as far as the authors are aware, this relationship has never been investigated. Moreover, there is a special need to investigate this relationship specifically for Generation Z users, the core target of TikTok (Qin et al., 2022; Miranda et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Given the aforementioned information, we can propose the following hypothesis:

H1: The motives for TikTok use exert a negative influence on perceived Ad Intrusiveness.

2.2.2 The motives for TikTok use and ad credibility

Marketers face a challenge, as intrusive ads can turn off consumers. Ads need to be believable to be effective. Ad credibility is defined as the “extent to which the consumer perceives claims made about the brand in the ad to be truthful and believable” (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989, p. 51). Trust in online advertising, which is also associated with the perception of a message’s reliability or credibility, is frequently considered a driver for decision-making (Diez-Arroyo, 2023). Also, ad credibility “captures a positive view of an ad” (Tran, 2017, p. 231), as a credible ad is a believable, truthful, and reliable one (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989; Tran, 2017). Alzaidi and Agag (2022) developed a model that highlights the role of certain variables, including trust, in consumer purchase behavior, showing that information concerns are one important driver of trust. On the other hand, as stated before, people have informational motives for sharing information on social media (Ren et al., 2023). In the age of AI-enabled technology, users encounter adapted ad content based on preferences (Wang et al., 2023). Generation Z users prefer to use social networks for accessing information (Sujanska and Nadanyiova, 2022), while, as previously stated, the information concern variable is an important driver of trust (Alzaidi and Agag, 2022). Given that the majority of TikTok users are adolescents and young adults from Generation Z, who are both tech-savvy and vulnerable (Qin et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023), we can assume the following:

H2: The motives for TikTok use positively influence Ad Credibility.

2.2.3 The motives for TikTok use and online flow experience

Two main motivations can drive people’s actions: achieving external goals, known as extrinsic motivation, or internal satisfaction, i.e., doing something for its own sake, known as intrinsic motivation (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Pop et al., 2022). Intrinsic motivation is a fundamental dimension of the flow experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975), which happens when people do things that are fun for them instead of things that are useful (Hoffman and Novak, 2009; Kwak et al., 2014; Obadă and Dabija, 2022). The task’s enjoyable, interesting, and challenging aspects, as well as the immediate feedback, embrace users and motivate them to continue (Obadă and Dabija, 2022). Yet, in some cases, extrinsic motivation may be an antecedent of flow, such as rewards or punishments when first engaging in a task (Chantal et al., 1995; Obadă, 2015; Teo et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017; Obadă and Dabija, 2022). Thus, users’ motivations, both intrinsic and extrinsic, drive the flow experience (Kwak et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2017). Both goal-directed and non-directed motives drive users’ behavior in computer-mediated environments (Hoffman and Novak, 2009). In the realm of digitally mediated environments, motivation serves as a precursor to focused engagement and a stepping stone toward achieving a state of flow (Obadă and Dabija, 2022). Therefore, motivation is an important driver for flow experience.

A distinctive, specific goal in mind determines social media engagement (Obadă and Dabija, 2022). As revealed by Leung and Bai (2013), motivation has a positive relationship with involvement on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. One motive for using TikTok, as stated before, is escapism (Omar and Dequan, 2020; Scherr and Wang, 2021; Gu et al., 2022). Most TikTok users are from the Generation Z cohort; as a result, authors expect that Generation Z users might use TikTok for escapism reasons, among other motives. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis for TikTok users in general and Generation Z users specifically:

H3: Motives for TikTok use have a positive influence on users’ online flow experience.

2.2.4 Attitude toward advertising, perceived ad intrusiveness, Ad Credibility and Ad Value

In the online environment, attitude toward online advertising, derived from the general definition of attitude toward advertising (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989), is the user’s learned predisposition to respond to online ads, encompassing both favorable and unfavorable attitudes (Redondo and Aznar, 2018).

The feature of intrusiveness associated with advertising (Li et al., 2002), analyzed for traditional or modern media, such as mobile and online environments (Cortés and Vela, 2013; Lim et al., 2023), generated research on ad intrusiveness and its impact on ad attitude. Cortés and Vela (2013) approached the mobile environment and revealed a negative relationship between perceived ad intrusiveness and attitude toward advertising. Intrusiveness can irritate (Cortés and Vela, 2013), which naturally leads to ad avoidance, with antecedents referring to perceptions or attitudes (Chinchanachokchai and de Gregorio, 2020). According to Tran (2017), avoidance negatively influences ad attitudes on a social networking site such as Facebook. The Lütjens et al. (2022) study aligns with Tran’s (2017) findings, demonstrating that irritation negatively impacts ad attitudes, while Redondo and Aznar (2018) emphasize that the perception of intrusiveness in the online environment shapes attitudes towards advertising in a negative relationship.

Given that TikTok users, who belong to Generation Z, prioritize speed and immediate gratification (Liu et al., 2023), we can postulate the following hypothesis:

H4: Perceived Ad Intrusiveness has a negative influence on Attitude toward advertising.

As stated before, a credible ad is a reliable, believable, and truthful one (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989; Tran, 2017). Intrusiveness may irritate (Cortés and Vela, 2013; Redondo and Aznar, 2018; Frade et al., 2021; Lütjens et al., 2022) and lead to ad avoidance (Frade et al., 2021; Goldfarb and Tucker, 2011; Niu et al., 2021; Lim et al., 2023), with the expectation of negatively influencing attitudes towards advertising. Given the prevalence of personalized ads (Wang et al., 2023), the attitude of Generation Z users towards advertising may shape their information-seeking preferences on social media, including TikTok (Sujanska and Nadanyiova, 2022). As a result, Generation Z users’ attitudes towards advertising influence information-seeking preferences (Sujanska and Nadanyiova, 2022), while the information concern variable is an important driver of trust (Alzaidi and Agag, 2022). If we assume that information concerns are linked to information-seeking preferences, we can formulate the following hypothesis:

H5: Attitude towards Advertising (ATT) displayed on TikTok will be positively associated with Ad Credibility (AC).

Attitude reflects a combination of both cognitive and affective associations (Trendel and Werle, 2016). Furthermore, Kim and Han’s (2014) research reveals a positive link between ad value and incentives, entertainment, and credibility. Ducoffe (1995, p. 1) defined ad value as “a subjective evaluation of the relative worth or utility of advertising to consumers.” As such, Kim and Han (2014) show that ad value is a measure of how effective the ad may be, also referring to Ducoffe’s (1995) model, which highlights that predictors of ad value are cognitive (informativeness) and affective (credibility) factors. There is limited research on the relationship between ad value and attitudes towards advertising. Previous studies have revealed that undervalued, irrelevant advertising may generate negative reactions from customers, while highly valued ads generate positive reactions (Pintado et al., 2017; Lin and Bautista, 2018; Martins et al., 2019; Van den Broeck et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2021).

Sharma et al.’s (2021) study on SMS advertising found that ad perception has a positive effect on ad value. According to MacKenzie and Lutz (1989), ad perception is a predictor of ad attitude. Perception and attitude influence behavioral intentions (Yen et al., 2023). As users, specifically Generation Z users, are heavily exposed to social media apps nowadays, it is expected that their attitude towards advertising is already shaped before logging into social media, including TikTok. This assumption is also based on the fact that Generation Z users find and engage with an adapted type of ad content (Wang et al., 2023) on TikTok. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H6: Attitude toward advertising displayed on TikTok has a positive influence on Ad Value.

Ducoffe’s model (1995), cited by Kim and Han (2014), revealed that one predictor of ad value is credibility. Subsequent research by multiple scholars has provided further evidence for this relationship, extending its applicability to wider contexts. For example, Sharma et al.’s (2021) research on the effect of SMS advertising perception on purchase intention underlined the significant positive effect of perception on advertising value, while one construct measuring perception is credibility. Kim and Han’s (2014) results highlighted a positive relationship between ad value and credibility for mobile advertising. Lin and Bautista (2018) found that credibility has a significant effect on the perceived value of location-based mobile advertising, whereas Pintado et al. (2017) reveal that brand trust limits the irritation effect on ad value. Abbasi et al. (2021) demonstrated a similar positive correlation between these two variables for in-game pop-up ads in a study that included nearly 75% of Generation Z users. Thus, we can assume that ad credibility positively influences ad value on TikTok when investigating Generation Z users who have extensive Internet usage (Blocksidge and Primeau, 2023). Therefore, we can posit the following hypothesis:

H7: Ad Credibility positively influences Ad Value.

2.2.5 Ad credibility, ad value, online flow experience and online impulse buying

As already stated, a credible ad is a believable, truthful, and reliable one (MacKenzie and Lutz, 1989; Tran, 2017), and the value of an ad is a measure of how effective it may be (Ducoffe, 1995). Kim and Han’s (2014) study on smartphone advertisements revealed that trust (associated with credibility) is a strong determinant of ad value, while ad value is an antecedent of flow experience. Alzaidi and Agag (2022) demonstrated similar results, concluding that trust plays a significant role in purchase intention on social media, while Sharma et al. (2021) underscored the positive influence of ad value on purchase intention. In their future research directions, Kim and Han (2014) suggest further testing the influence of ad value on flow experience.

Impulse buying was defined by Rook and Fisher (1995, p. 306) as “a consumer’s tendency to buy spontaneously, unreflectively, immediately, and kinetically.” Impulse buying is widespread in online shopping (Danish Habib and Qayyum, 2014; Wu et al., 2020), including shopping through social media platforms (Kimiagari and Asadi Malafe, 2021). Prior research indicates that impulse buying influences purchase decisions (Lee and Chen, 2021). Generation Z, in particular, is constantly searching for instant satisfaction and immediate response (Liu et al., 2023), so it may be prone to online buying impulsiveness.

Goel et al. (2022) results reveal the link between e-impulse buying and purchase intention, highlighting that online impulse buying is an indicator of online shopping continuance. The increased ease of access to information facilitated by the internet has led researchers to assume that online impulse buying behavior is a factor in a large amount of online shopping (Wu et al., 2020). Analyzing Generation Z users on TikTok, Zhou et al. (2023) found that perceived trust is an important driver of users’ behavior. Based on the analysis of Generation Z’s e-lifestyle users on TikTok (Wijaya et al., 2020), we can propose the following two hypotheses:

H8: Ad Credibility is positively associated with online impulse buying.

H9: Ad Value exerts a positive influence on online flow experience.

Kim and Han (2014) highlight the importance of both value perception and flow experience in driving purchase intentions, with flow exerting a notable impact on purchase intention. The two researchers explain that if users absorb and focus on ads, they are more likely to understand and enjoy the message (Kim and Han, 2014). Xu et al. (2021), Hyun et al. (2022), and Kim (2022) also explained the positive, significant effect of flow experience on behavioral intention in studies investigating the application of social media platforms for diverse aims, while Wu et al. (2020) particularly found a positive relation between flow state and online shopping impulse buying. Kim and Han’s (2014) future research direction suggested testing the impact of flow on purchase intention, specifically with online impulse buying. Meanwhile, Wu et al. (2020) advocate for future research endeavors that delve into the phenomenon of online impulse buying from diverse perspectives, including a specific type of media communication (i.e., TikTok). Also, Qu et al. (2023) recommended, as a future direction, exploring the role of flow in studies examining impulse buying tendencies in scarcity-induced purchases. Considering the needs of Generation Z TikTok users, who prioritize instant satisfaction and prompt responses (Liu et al., 2023), we can propose the following hypothesis:

H10: Online flow experience exerts a positive influence on online impulse buying.

Figure 1 depicts the proposed research model.

3 Method

3.1 Research design

This study employed a quantitative methodology to collect data from primary sources, Generation Z TikTok users, through an online survey based on a questionnaire. The overall research design approach involved conducting a correlational study in a single country. Because we analyzed the variables using only one sample of subjects, the study was cross-sectional. The decision was based on our research goal and objectives, which aimed to understand the relationship between the variables in the proposed research model. The authors’ choice to focus their inquiry on the emerging market in Romania is well-founded, given that at the beginning of 2023, TikTok had 7.58 million users aged 18 and older in Romania, and its advertisements reached 46.8 percent of all adults aged 18 and older in this country (DataReportal, 2023). Moreover, in the last three years, TikTok’s advertising sales have increased considerably, reaching its highest point of $1.29 million in March 2023 (Statista, 2023). Hence, Romania serves as a significant global benchmark for testing the proposed model, offering a valuable research context for both theoretical insights and practical applications.

3.2 Participants

The study participants were Generation Z TikTok users from Romania. We established an age criterion in our online screening questionnaire with the explicit intention of identifying individuals from Generation Z, since this was our research population. We also used filter questions to gather pertinent information, such as age, TikTok usage time, and exposure to TikTok ads.

3.3 Questionnaire design

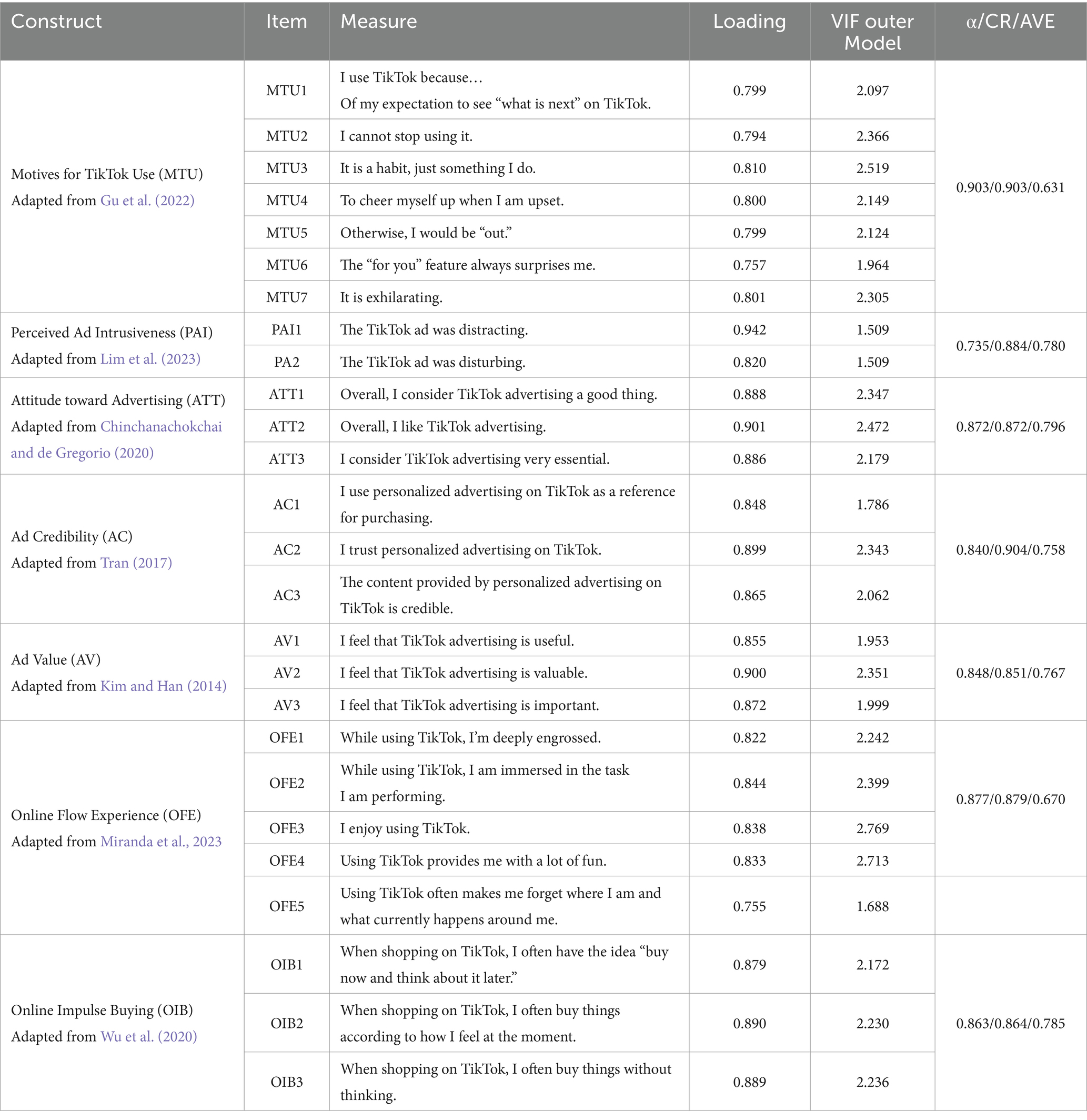

We developed the online questionnaire by adapting and modifying the unidimensional scales from the literature, which demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in terms of prior reliability and validity (see Table 1). The scales for Motives for TikTok Use (MTU) (construct comprising 7 items), Perceived Ad Intrusiveness (PAI) (construct comprising 2 items), Attitude towards Advertising (ATT) (construct comprising 3 items), Ad Credibility (AC) (construct comprising 3 items), Ad Value (AV) (construct comprising 3 items), Online Flow Experience (OFE) (construct comprising 5 items), and Online Impulse Buying (OIB) (construct comprising 3 items) were all reflective. To evaluate each construct, participants were requested to indicate their degree of agreement with a range of statements via 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Before administering the questionnaire, we ensured that the items were readily understood by the participants and ran a pilot test involving 120 respondents who were TikTok users from Generation Z. We provided the participants with a draft of the online questionnaire containing all the items, asking them to carefully read them. They highlighted any unclear word or sentence and provided an alternative. The purpose of pre-testing was to evaluate their language comprehension and identify any potential instrumental errors. We made minor modifications to the initial questionnaire design based on the findings of the pilot study.

3.4 Data collection procedure

In December 2023, the researchers collected data from Romanian TikTok users from Generation Z who agreed to participate in the study by clicking the anonymous link in the online questionnaire, using a snowball sampling technique. The first section of the questionnaire described the study and included an online consent form, emphasizing the confidentiality and anonymity of the responses and stating that participation was voluntary. In addition, we employed filter questions to gather pertinent information, including age, time of TikTok usage, and exposure to TikTok ads. We also implemented control questions to ensure response quality and mitigate the drawbacks of online surveys. Sharing the study’s hyperlink with TikTok users gathered a total of 2,928 responses. After an initial assessment of the data quality, we retained 2,406 valid responses for further analysis. We excluded incomplete questionnaires, more specifically those that failed to satisfy the study’s criteria or lacked control questions.

3.5 Ethical considerations

We avoided gathering any data that may potentially reveal the identity of the participants, including their ID number, physical attributes, physiological traits, psychological characteristics, economic status, cultural background, or social qualities (i.e., any personal data). Furthermore, we required parental consent for respondents under the age of 18; therefore, we included an initial section in the online questionnaire to obtain their permission. Overall, we adhered to national laws, specifically Law 677/2001 and Law 206/2004, which govern ethical standards in scientific research in Romania, ensuring the protection of the participants’ rights.

3.6 Data analysis

We analyzed the data collected in the study using both descriptive and inferential statistics. We obtained the descriptive statistics for the measured variables, including means and standard deviations, using the SPSS software, version 23. We performed the inferential phase of our study by employing structural equation modelling (SEM) with Smart PLS 4 to test the hypotheses. Considering that our objective was theory-building, the SmartPLS software is appropriate for this type of investigation (Ringle et al., 2015). Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) is a valuable analytical method that allows for the simultaneous execution of factor analysis and path analysis. Following Kline’s (2016) recommended two-step modelling technique, we initially assessed the outer model (i.e., measurement model), followed by testing the direct relationships in the inner model (i.e., structural model).

4 Results

4.1 Sample characteristics and descriptive statistics

In terms of relevant demographic information, participant ages ranged from 15 to 27 years (M = 21.23; SD = 2.31). Most respondents were between 20 and 22 years old (55.37%; n = 1,086). In terms of gender, 63.30% (n = 961) identified as female, while 36.70% (n = 562) identified as male. A majority (52.54%; n = 1,264) graduated from high school and resided in an urban area (64.30%; n = 1,547). Over half of the respondents (55.10%; n = 1,325) reported low income, and the majority (51.70%; n = 1,204) were students. About half of them (49.80%; n = 1,198) claimed to spend 2 to 3 h a day on TikTok.

4.2 Evaluating the measurement model

We evaluated the measurement models in the initial phase using SmartPLS 4.0’s structural equation modelling capability. We tested every reflective construct from the conceptual model for internal consistency and validity. Table 2 provides the item loadings, reliability indicators, average variance extracted (AVE), and VIF values. The loadings exceed the minimum threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010), indicating the presence of convergent validity in all the measured items. The minimum and maximum values lie within the range of 0.755 (OFE5 item) and 0.942 (PAI2 item), thereby satisfying the minimum criteria. We evaluated reliability using Cronbach’s α, with a threshold of 0.7 or greater considered satisfactory for confirmatory analysis (Henseler and Sarstedt, 2013). All reliability scores exceed 0.7, thereby confirming the internal consistency of the model. All AVE values surpassing 0.5 signify a sui model and support the convergent validity of the constructs (Chin, 1998). When the composite values exceed 0.7, the composite reliability (CR) indicates adequate reliability of the constructs (Hair et al., 2010). Additionally, we assessed the level of collinearity between the items in the measurement model. The dataset does not demonstrate multicollinearity, as the highest VIF value among all items is 2.769 (OFE3 item), which is lower than the collinearity analysis threshold of 3.3 as established by Hair et al. (2017). Consequently, the existence of common method bias (CMB) was not an issue.

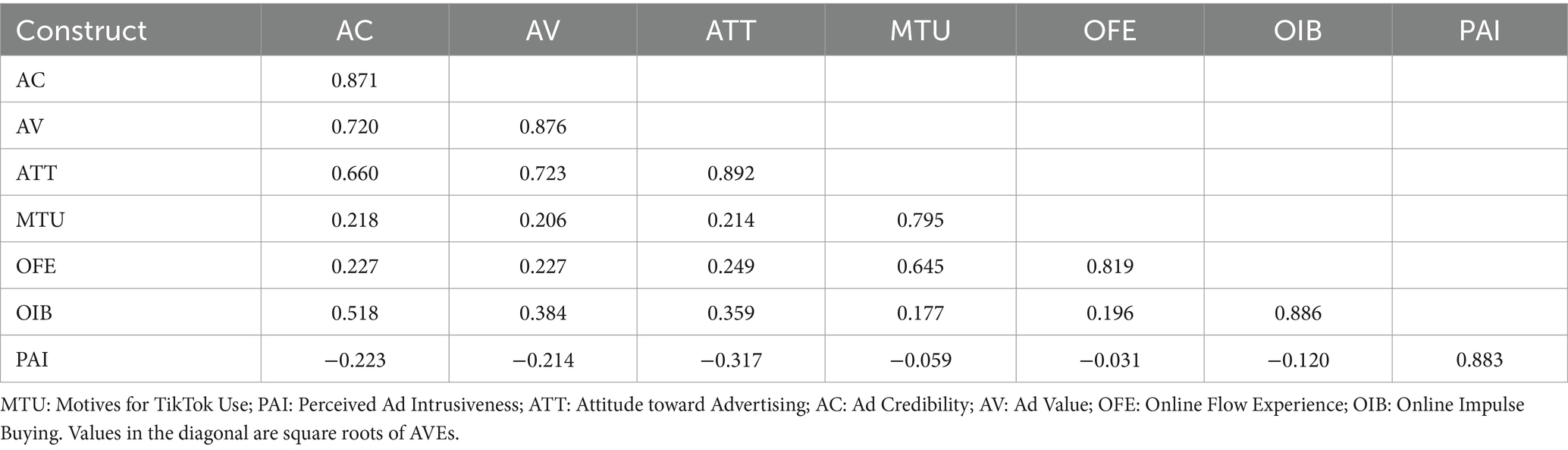

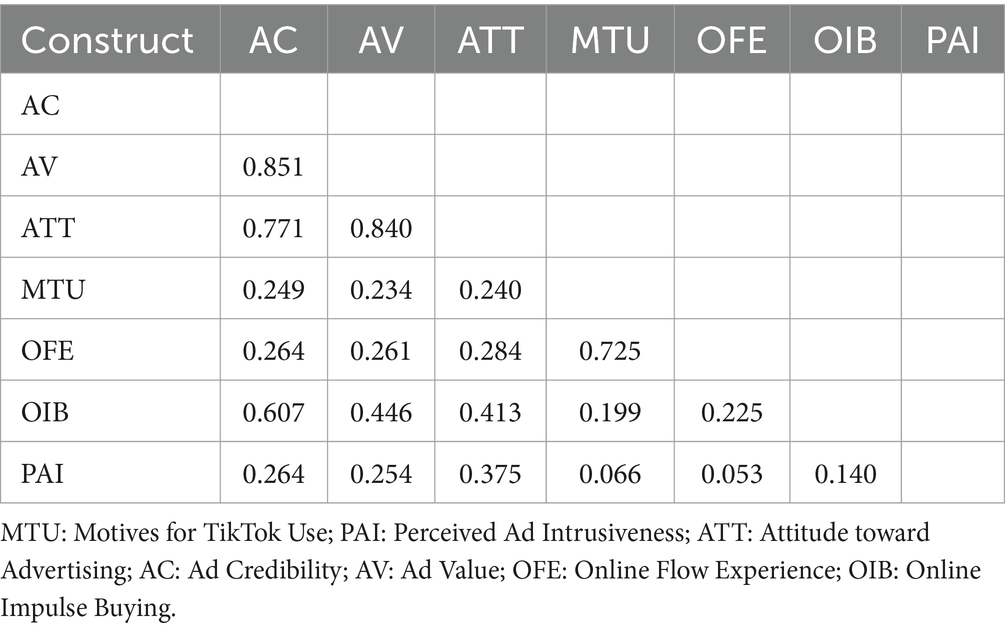

We have assessed discriminant validity for each concept using the Fornell-Larcker (Table 2) and Heterotrait-Monotrait (Table 3) criteria. Following the Fornell-Larcker standards (Hair et al., 2010; Henseler and Sarstedt, 2013), the AVE value for each latent variable should be greater than the correlation coefficient between that variable and all of the other variables.

To ensure that the concepts are not conceptually identical, we applied the Heterotrait–Monotrait criterion. All construct values in the present study are found to be lower than the critical value of 0.9 (Henseler et al., 2015), which provides evidence for the constructs’ discriminant validity.

After evaluating the measurement model, in the next phase, we employed the bootstrap method to test the hypotheses and determine relationships between the latent variables. To properly assess the structural model, it was important to examine the constructs’ collinearity. The inner model’s highest VIF values are 1.744 (AC → AV and ATT → AV), which is below the critical value of 3.3 (Hair et al., 2017). This suggests that there is no multicollinearity among the constructs. The square root mean residual (SRMR) was 0.046, which meets the minimum threshold of 0.08 and indicates that the saturated model’s fit quality is acceptable. As highlighted in Figure 2, Motives for TikTok Use explain 0.3% (R2 = 0.003) of the variance of Perceived Ad Intrusiveness. Furthermore, 44.2% (R2 = 0.442) of the variance of Ad Credibility is explained by Attitude toward Advertising and Motives for TikTok Use, while Perceived Advertising Intrusiveness explains 10% (R2 = 0.100) of the Attitude toward Advertising. Furthermore, Attitude toward Advertising and Ad Credibility account for 62.7% (R2 = 0.627) of the variance of Ad Value. Motives for TikTok Use and Ad Value explain 42.6% (R2 = 0.426) of the variance of Online Flow Experience. Finally, 27.4% (R2 = 0.274) of the variance of Online Impulse Buying is explained by the Online Flow Experience and Ad Credibility. Also, the model has good predictive power for the endogenous latent variable since the Q2 values of the exogenous variables are >0 (PAI = 0.002, ATT = 0.008, AV = 0.017, OIB = 0.025, AC = 0.031, and OFE = 0.415) (Hair et al., 2017).

4.3 Hypothesis testing

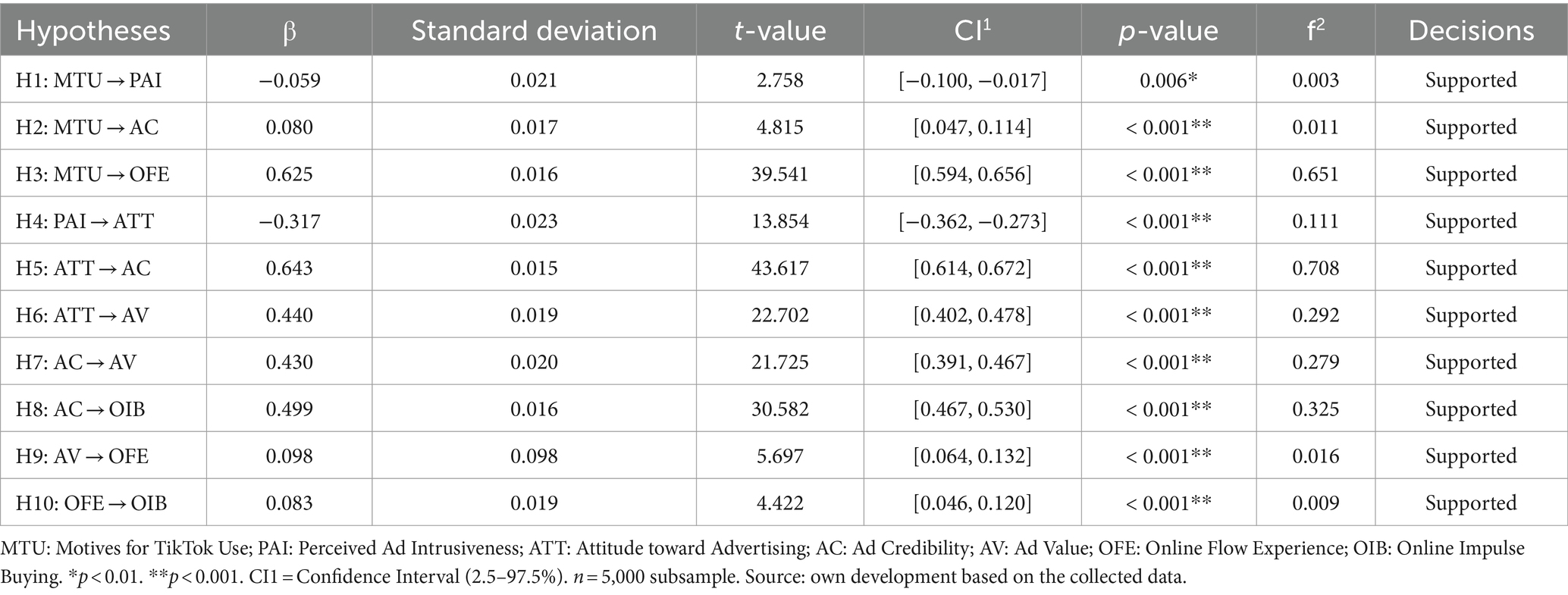

As shown in Table 4, all ten hypotheses (H1–H10) were empirically validated. The Cohen f2 effect magnitude represents the influence of exogenous variables on endogenous variables. According to Cohen (2013), effect size values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are categorized as small, medium, and large, respectively.

Hypothesis 1 posited that Motives for TikTok Use (MTU) have a negative impact on Perceived Ad Intrusiveness (PAI). The findings (β = −0.059; t-value = 2.758; p < 0.006) indicate a weak yet statistically significant negative effect; therefore, H1 is supported.

As deduced from Hypothesis 2, Ad Credibility (AC) was presumed to be positively impacted by the Motives for TikTok Use (MTU). The findings indicate a small but statistically significant relationship (β = 0.080; t-value = 4.815; p < 0.001); thus, H2 is validated.

Hypothesis 3 postulated that there is a positive effect of Motives for TikTok Use (MTU) on the Online Flow Experience (OFE). The results (β = 0.625; t-value = 39.541; p < 0.001) indicate a positive, large effect, leading to support H3.

Hypothesis 4 asserted that there is a negative relationship between Attitude towards Advertising (ATT) and Perceived Ad Intrusiveness (PAI). The outcomes (β = −0.317; t-value = 13.854; p < 0.001) indicate a small yet statistically significant negative impact; thus, hypothesis H4 is validated.

Hypothesis 5 assumed that Attitude toward Advertising (ATT) would be positively associated with Ad Credibility (AC). The results (β = 0.643; t-value = 43.617; p < 0.001) suggest the existence of a positive, large effect; thus, hypothesis H5 is supported.

Hypothesis 6 stipulated that Attitude toward Advertising (ATT) has a positive influence on Ad Value (AV). The findings (β = 0.440; t-value = 22.702; p < 0.001) confirm the presence of a positive, moderate effect, providing support for hypothesis H6.

Hypothesis 7 presumed that Ad Value (AV) is positively impacted by Ad Credibility (AC). The outcomes (β = 0.430; t-value = 21.725; p < 0.001) demonstrate the existence of a moderately positive impact that provides support for hypothesis H7.

Hypothesis 8 proposed that Ad Credibility (AC) will be positively associated with Online Impulse Buying (OIB). The study insights (β = 0.499; t-value = 30.582; p < 0.001) indicate the presence of a moderately positive impact that provides support for hypothesis H8.

According to Hypothesis 9, Online Flow Experience (OFE) will be positively impacted by Advertising Value (AV). The results (β = 0.098; t-value = 5.697; p < 0.001) pinpoint the existence of a small yet statistically significant effect; thus, hypothesis H9 is validated.

Finally, Hypothesis 10 assumed that Online Flow Experience (OFE) exerts a positive influence on Online Impulse Buying (OIB). The findings of the study (β = 0.083; t-value = 4.422; p < 0.001) highlight the presence of a small yet statistically significant impact; therefore, the H10 hypothesis is confirmed.

Based on the research assumptions, the results indicate:

• there is a negative impact of Motives for TikTok Use on Perceived Ad Intrusiveness;

• motivation to use TikTok increases perception of ad credibility and enhances the overall user optimal experience;

• perceiving an ad as intrusive would have a detrimental impact on ad attitudes on TikTok;

• a positive ad attitude positively influences the perception of Ad Credibility and Ad Value;

• an ad perceived to be valuable will also be perceived as trustworthy;

• a credible ad is more likely to increase online buying impulsiveness;

• perceived valuable ads raise the online flow experience, which in turn positively influences online impulse buying.

5 Discussion

This study aimed to understand the factors that drive the buying impulsiveness of Generation Z users on TikTok in an emerging market. To explain this phenomenon, the proposed conceptual model, based on flow theory, included relevant variables from the literature. The study findings aligned with our research objectives: (1) the motivations for using TikTok and the perceived value of the ads influence the flow experience, which leads to impulse buying; (2) enhancing the perceived credibility of ads is an effective strategy, as it positively influences online impulse buying. Since the attitude towards advertising influences ad credibility, which in turn influences the perceived intrusiveness of ads, we can conclude that enhancing ad credibility is the most effective advertising tactic to elicit impulse purchases. Additionally, different motivations for using TikTok influence the perception of intrusiveness and credibility of ads, as well as the flow experience, since motivations are the antecedents of flow. Therefore, the study validated the initial assumptions.

5.1 Relating the findings to earlier work

As we already argued, previous research focused on the effects of flow on behavioral intention (Chang and Zhu, 2012; Kim and Han, 2014; Pelet et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021; Hyun et al., 2022; Kim, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023) or advertising latent variable relations (Jung, 2017; Tran, 2017; Zarouali et al., 2017; Redondo and Aznar, 2018; Abbasi et al., 2021; Niu et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021; Alzaidi and Agag, 2022; Lütjens et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023), without identifying specific outcomes of these relations shaped by Generation Z users. Therefore, our study is the first to investigate these relationships, thus having an important theoretical and practical contribution.

The study reveals that motives for TikTok use negatively impact perceived ad intrusiveness. Contrary to previous research suggesting intrusiveness interrupts consumers’ goals (Li et al., 2002), the study suggests that people prefer TikTok ads due to their unique features, such as non-interrupted content, adaptability, user-friendliness, and the ability to swipe away unappealing advertisements (Han, 2020). People perceive advertising as transparent, making it easy for them to learn about the features and effects of the products from other comments (Han, 2020). The study confirms Lütjens et al.’s (2022) finding that the irritation effect decreases over time, likely due to consumers’ habituation to emerging technologies and their evolving sensitivity to diverse touchpoints, a novel relationship in the current research. Users like ads on TikTok (Han, 2020). TikTok’s vertical video ads, which effortlessly integrate with Generation Z’s usage habits and require minimal effort, may be the reason for this (Mulier et al., 2021). Lütjens et al.’s (2022) conclusions are in line with our results, revealing that, as the authors assumed, young users are already accustomed to new technologies and, as a result, users’ attitudes towards ads are already formed before engaging on the social media platform. All these might explain the positive relationships between attitude towards advertising and both Ad Credibility and Ad Value, two relations representing novelties of the current study. This finding also suggests that users’ motivation to use TikTok positively impacts ad credibility and online flow experience, as adapted ads increase credibility and users appreciate these ads, enhancing the overall user optimal experience. Moreover, this study identified a negative relationship between individuals’ attitudes towards advertising and perceived ad intrusiveness. These results are in line with the research conducted by Cortés and Vela (2013), which demonstrates a negative correlation between perceived ad intrusiveness and attitude towards advertising. Tran (2017) and Lütjens et al. (2022) further emphasize that avoidance or irritation, which are linked to intrusiveness, have a detrimental impact on ad attitudes. Additionally, Redondo and Aznar (2018) identify a negative relationship between attitude towards advertising in the online environment and perception of intrusiveness.

According to the research’s findings, ad credibility positively influences ad value, which is consistent with earlier studies on SMS advertising perception by Sharma et al. (2021), mobile advertising by Kim and Han (2014), and in-game pop-up ads by Abbasi et al. (2021). This study provides an important insight into the fact that ad credibility is positively associated with online impulse buying. This study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to examine this specific relationship. The Alzaidi and Agag (2022) paper, for example, studied the relationship between ad value and purchase intention. From this point of view, this relationship is one of the novelties of the current study.

In the proposed and validated model, the authors found that ad value positively impacts the online flow experience, which in turn positively influences online impulse buying. Following the research directions proposed by Kim and Han (2014) to examine the impact of ad value on flow and the relationship between flow and purchase intention, the study focused on investigating the relationship between online flow experience, ad value, and online impulse buying for the first time. This is another novelty in our study.

The present study also focused on the effect of ad value on online flow and the relationship between ad credibility and online flow experience on online impulse buying. This approach is consistent with Wu et al.’s (2020) suggestions for future research, which outline the need to learn more about online impulse buying through the lens of a certain type of media communication (TikTok), and Qu et al.’s (2023) advice to investigate the role of online flow in influencing impulse buying in scarcity-induced purchases. Therefore, the confirmation of these relationships represents another novelty of the current study.

In conclusion, understanding the factors that drive online impulse buying among Generation Z on TikTok in an emerging market depends on factors such as individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, and motivations. This research is unique as it examines the drivers of online impulse buying from two perspectives: the advertising dimensions, which originate from the communication field, and the motives and flow experience, which stem from the positive psychology field.

5.2 Theoretical and research implications

Theoretically, this article explores the factors driving online impulse buying on TikTok, particularly from Generation Z’s perspective, including motives for TikTok use, perceptions, and attitudes towards advertising on TikTok and online flow experience. According to the research, when users engage with ads, the motivation to use TikTok does not create intrusiveness, possibly due to the ability to swipe out ads as soon as they appear. Our investigation reveals that attitude towards advertising positively influences Ad Credibility and Ad Value, suggesting that Generation Z users already have an ad attitude due to their experience with social media platforms. The current study revealed, as a new insight, that attitude towards advertising has a positive influence on Ad Credibility and Ad Value. Another novelty of the study is that the authors approached online impulse buying, keeping in mind that prior research focused more on purchase intentions. This approach led to the discovery of a positive relationship between ad credibility and online impulse buying, as well as a positive relationship between online flow experience and online impulse buying. This study provides new insights for future research on the topic.

5.3 Practical implications

The study has important practical implications. Communication and marketing managers can gain important insights from our investigation, which reveals that users are curious about the next TikTok video and use the platform as a habit, bringing joy, adaptation, and social integration. Furthermore, the motives to use TikTok impact the perception of ads, with highly-rated motives not being considered distracting or disturbing. Practitioners, particularly those targeting Generation Z, can benefit from this insight, as they perceive ads as neither intrusive nor irritating. However, we should conduct studies to identify the motives and scores of other generational cohorts, as higher scores tend to indicate less intrusive ads. High scores on motives to use TikTok also increase the perception of ads as credible and improve the online flow experience, making platform engagement enjoyable, funny, and immersive. The results of our research suggest that companies should focus on content-driven advertising that provides solutions and insights tailored to users’ needs and wants. If users are constantly exposed to content-driven advertising providing solutions and insights adapted to their needs and wants, then a positive attitude is created, leading to the assessment of ads as trustworthy, valuable, and important. This positive attitude contrasts with intrusiveness and enhances the perceived ad value, leading to an enjoyable, immersive experience on the platform (i.e., an online flow experience). Therefore, adapted ad content over time shapes a positive attitude toward advertising, which, in turn, creates a positive perception of ads in terms of credibility and value and an optimal experience on the platform. The positive effect of ad credibility perception on impulsive buying suggests that, if an ad on TikTok is trustworthy, Generation Z users may easily “buy now and think about it later” without giving it much thought, as this aligns with their current mindset. This insight has profound managerial implications, especially in the case of impulsive buying of products (e.g., clothes, perfumes, etc.). Moreover, this consequence is easier to attain on TikTok, supported by the positive effect of the online flow experience over online impulse buying. Finally, we argue that communication and marketing managers need to focus on building the credibility of their communication efforts over time to avoid losing their audience due to users’ tendency to buy online impulsively, even though the TikTok platform has proven to be an enjoyable, funny, and immersive one that encourages impulsive buying.

5.4 Further research and limitations

Future research might employ objective measuring techniques, such as the experience sampling method (ESM), for online flow experience. Also, our research focused only on Generation Z of TikTok users, but future research could explore the perspectives of different audience cohorts, comparing Xers and Baby Boomers of this social media platform with others (e.g., Facebook, X, YouTube, etc.). Other empirical studies could pinpoint if user experience and education have or do not have a relevant role in explaining how individuals respond to perceived invasiveness. Moreover, the negative impact of motives for TikTok use exerted on perceived ad intrusiveness partially approaches a future research direction suggested by Niu et al. (2021), specifically examining factors that influence perceived invasiveness. Furthermore, given the dynamic nature of social media platforms, we contend that further investigation is necessary to comprehend the formation and evolution of attitudes towards advertising. Comprehensive qualitative and quantitative research could potentially provide valuable insights into enhancing the perceived credibility and value of advertisements. Subsequent research provided a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between the findings of this study and the unique cultural and behavioral characteristics of Romanian Generation Z individuals, which could be a useful insight for practitioners operating in emerging markets.

This study contains inherent limitations that could potentially be addressed in future research. We restricted our investigation to Romania, a burgeoning EU market; consequently, the findings are not universally applicable to other social contexts and necessitate interpretation within their specific cultural context. Future studies should take a comparative approach, either by including more countries from Central and Eastern Europe or by comparing developed and emerging countries using probability sampling. Another limitation of the study is the use of a self-administered questionnaire as a method of measuring the variables, which is a form of retroactive assessment.

Finally, this study used cross-sectional data, analyzed by regression, which means these results could be based on spurious correlations. For example, the flow of causality in Figure 1 may in fact be in the reverse direction (impulse buyers justify their behavior by bolstering their attitude toward advertising).

6 Conclusion

This study aimed to understand the factors that drive the buying impulsiveness of Generation Z users on TikTok in an emerging market. The paper specifically reveals that the motivation to use TikTok does not create intrusiveness and that an attitude towards advertising positively influences Ad Credibility and Ad Value. This suggests that Generation Z users already possess an ad attitude due to their experience with social media platforms. Moreover, the study indicates a positive relationship between ad credibility, flow experience, and online impulse buying. As such, companies should focus on content-driven advertising tailored to users’ specificities to create a positive attitude toward advertising, a perception of ad value, and an optimal experience on the platform. Increasing ad credibility perception is especially important to prevent losing the audience due to users’ tendency to buy online impulsively. Further research could provide valuable insights into enhancing the perceived credibility and value of advertisements.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants legal guardian/next of kin was obtained at the start of the questionnaire.

Author contributions

D-RO: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. OȚ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The APC was funded by the “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iasi through the Fund for Financing Scientific Research in Universities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasi, A. Z., Rehman, U., Hussain, A., Ting, D. H., and Islam, J. U. (2021). The impact of advertising value of in-game pop-up ads in online gaming on gamers’ inspiration: an empirical investigation. Telematics Inform. 62:101630. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2021.101630

Alshohaib, K. A. (2024). From screens to carts: the role of emotional advertising appeals in shaping consumer intention to repurchase in the era of online shopping in post-pandemic. Front. Commun. 9:1370545. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1370545

Alves de Castro, C. (2023). Thematic analysis in social media influencers: who are they following and why? Front. Commun. 8:1217684. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1217684

Alzaidi, M. S., and Agag, G. (2022). The role of trust and privacy concerns in using social media for e-retail services: the moderating role of COVID-19. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 68:103042. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103042

Amatulli, C., Peluso, A. M., Sestino, A., Guido, G., and Belk, R. (2023). The influence of a lockdown on consumption: an exploratory study on generation Z's consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 73:103358. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103358

Blocksidge, K., and Primeau, H. (2023). Adapting and evolving: generation Z's information beliefs. J. Acad. Librariansh. 49:102686. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2023.102686

Brailovskaia, J., and Margraf, J. (2024). From fear of missing out (FoMO) to addictive social media use: the role of social media flow and mindfulness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 150:107984. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2023.107984

BusinessofApps . (2024). TikTok Revenue and Usage Statistics (2024). Retrieved January 12, 2024, from: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/ (Accessed January 12, 2024).

Chang, Y. P., and Zhu, D. H. (2012). The role of perceived social capital and flow experience in building users’continuance intention to social networking sites in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28, 995–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.01.001

Chantal, Y., Vallerand, R. J., and Vallières, E. F. (1995). Motivation and gambling involvement. J. Soc. Psychol. 135, 755–763. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1995.9713978

Chin, W. W. (1998). “The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling” in Methodology for business and management: modern methods for business research. ed. G. A. Marcoulides (London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 295–336.

Chinchanachokchai, S., and de Gregorio, F. (2020). A consumer socialization approach to understanding advertising avoidance on social media. J. Bus. Res. 110, 474–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.062

Cortés, L. G., and Vela, R. M. (2013). The antecedents of consumers’ negative attitudes toward SMS advertising: a theoretical framework and empirical study. J. Interact. Advert. 13, 109–117. doi: 10.1080/15252019.2013.826553

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., and LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 815–822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.815

Dania, T., Chládková, H., Duda, J., Kožíšek, R., and Hrdličková, A. (2023). The motivation of generation Z: a prototype of the Mendel university student. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 21:100891. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100891

Danish Habib, M., and Qayyum, A. (2014). Cognitive emotion theory and emotion-action tendency in online impulsive buying behavior. J. Manag. Sci. 5, 86–99. doi: 10.20547/jms.2014.1805105

DataReportal . (2023). Essential TikTok statistics and trends for 2023. Available at: https://datareportal.com/essential-tiktok-stats?utm_source=DataReportal&utm_medium=Country_Article_Hyperlink&utm_campaign=Digital_2023&utm_term=Romania&utm_content=Facebook_Stats_Link (Accessed January 10, 2024).

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation, and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY, USA: Plenum.

Diez-Arroyo, M. (2023). Epistemic vigilance and persuasion: the construction of trust in online marketing. J. Pragmat. 215, 101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2023.07.007

Dimara, N. I., and Parahiyanti, C. R. (2024). Impulsive buying in TikTok livestreaming: enhancing the role of telepresence, Brand Trust, and flow state. Innov. Technol. Entrep. J. 1, 42–54. doi: 10.31603/itej.10926

Ducoffe, R. H. (1995). How consumers assess the value of advertising. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 17, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/10641734.1995.10505022

Feng, Z., Al Mamun, A., Masukujjaman, M., Wu, M., and Yang, Q. (2024). Impulse buying behavior during livestreaming: moderating effects of scarcity persuasion and price perception. Heliyon 10:e28347. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28347

Frade, J. L., Oliveira, J. H., and Giraldi, J. D. (2021). Advertising in streaming video: an integrative literature review and research agenda. Telecommun. Policy 45:102186. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102186

Gallin, S., and Portes, A. (2024). Online shopping: how can algorithm performance expectancy enhance impulse buying? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 81:103988. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.103988

Goel, P., Parayitam, S., Sharma, A., Rana, N. P., and Dwivedi, Y. K. (2022). A moderated mediation model for e-impulse buying tendency, customer satisfaction and intention to continue e-shopping. J. Bus. Res. 142, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.041

Goldfarb, A., and Tucker, C. (2011). Online display advertising: targeting and obtrusiveness. Mark. Sci. 30, 389–404. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1100.0583

Gu, L., Gao, X., and Li, Y. (2022). What drives me to use TikTok: a latent profile analysis of users' motives. Front. Psychol. 13:992824. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992824

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., and Babin, B. J. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective. London, UK: Pearson.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 2nd Edn. USA: Sage Publications.

Han, Y. (2020). Advertisement on Tik Tok as a pioneer in new advertising era: exploring its persuasive elements in the development of positive attitudes in consumers. Front Soc Sci Technol 2, 81–92. doi: 10.25236/FSST.2020.021113

Han, M. C. (2023). Checkout button and online consumer impulse-buying behavior in social commerce: a trust transfer perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 74:103431. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103431

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Henseler, J., and Sarstedt, M. (2013). Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Comput. Stat. 28, 565–580. doi: 10.1007/s00180-012-0317-1

Hoffman, D. L., and Novak, T. P. (2009). Flow online: lessons learned and future prospects. J. Interact. Mark. 23, 23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2008.10.003

Hyun, H., Thavisay, T., and Lee, S. H. (2022). Enhancing the role of flow experience in social media usage and its impact on shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 65:102492. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102492

Jung, A. R. (2017). The influence of perceived ad relevance on social media advertising: an empirical examination of a mediating role of privacy concern. Comput. Hum. Behav. 70, 303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.008

Khan, M. L. (2017). Social media engagement: what motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Comput. Hum. Behav. 66, 236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.024

Kim, M. (2022). How can I be as attractive as a fitness YouTuber in the era of COVID-19? The impact of digital attributes on flow experience, satisfaction, and behavioral intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 64:102778. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102778

Kim, Y., and Han, J. (2014). Why smartphone advertising attracts customers: a model of web advertising, flow, and personalization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 33, 256–269. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.015

Kim, M. J., Lee, C.-K., and Bonn, M. (2017). Obtaining a better understanding about travel-related purchase intentions among senior users of mobile social network sites. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 37, 484–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.04.006

Kimiagari, S., and Asadi Malafe, N. S. (2021). The role of cognitive and affective responses in the relationship between internal and external stimuli on online impulse buying behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 61:102567. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102567

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th Edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Kwak, K. T., Choi, S. K., and Lee, B. G. (2014). SNS flow, SNS self-disclosure and post hoc interpersonal relations change: focused on Korean Facebook user. Comput. Hum. Behav. 31, 294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.046

Lavoie, R., and Zheng, Y. (2022). Smartphone use, flow and wellbeing: a case of Jekyll and Hyde. Comput. Hum. Behav. 138:107442. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107442

Lee, C. H., and Chen, C. W. (2021). Impulse buying behaviors in live streaming commerce based on the stimulus-organism-response framework. Information 12:241. doi: 10.3390/info12060241

Lemmens, J. S., and von Münchhausen, C. F. (2023). Let the beat flow: how game difficulty in virtual reality affects flow. Acta Psychol. 232:103812. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103812

Leung, X. Y., and Bai, B. (2013). How motivation, opportunity, and ability impact travelers’ social media involvement and revisit intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 30, 58–77. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2013.751211

Li, B., Chen, S., and Zhou, Q. (2023). Empathy with influencers? The impact of the sensory advertising experience on user behavioral responses. J. Retail.Consum. Serv. 72, 103286. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103286

Li, H., Edwards, S. M., and Lee, J.-H. (2002). Measuring the intrusiveness of advertisements: scale development and validation. J. Advert. 31, 37–47. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2002.10673665

Lim, R. E., Sung, Y. H., and Hong, J. M. (2023). Online targeted ads: effects of persuasion knowledge, coping self-efficacy, and product involvement on privacy concerns and ad intrusiveness. Telematics Inform. 76:101920. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2022.101920

Lin, T. T., and Bautista, J. R. (2018). Content-related factors influence perceived value of location-based mobile advertising. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 60, 184–193. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2018.1432995

Liu, R. (2023). WeChat online visual language among Chinese gen Z: virtual gift, aesthetic identity, and affection language. Front. Commun. 8:1172115. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1172115

Liu, Y., Sun, X., Zhang, P., Han, P., Shao, H., Duan, X., et al. (2023). Generation Z nursing students' online learning experiences during COVID-19 epidemic: a qualitative study. Heliyon 9:e14755. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14755

Lütjens, H., Eisenbeiss, M., Fiedler, M., and Bijmolt, T. (2022). Determinants of consumers’ attitudes towards digital advertising – a meta-analytic comparison across time and touchpoints. J. Bus. Res. 153, 445–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.07.039

MacKenzie, S. B., and Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. J. Mark. 53, 48–65. doi: 10.2307/1251413

Martins, J., Costa, C., Oliveira, T., Gonçalves, R., and Branco, F. (2019). How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 94, 378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.047

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 50, 370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346

Miranda, S., Trigo, I., Rodrigues, R., and Duarte, M. (2023). Addiction to social networking sites: motivations, flow, and sense of belonging at the root of addiction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 188:122280. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122280

Mulier, L., Hendrik, S., and Vermeir, I. (2021). This way up: the effectiveness of mobile vertical video marketing. J. Interact. Mark. 55, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2020.12.002

Ndasauka, Y., and Ndasauka, F. (2024). Cultural persistence and change in university students’ social networking motives and problematic use. Heliyon 10:e24830. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24830

Ngo, T. T. A., Nguyen, H. L. T., Nguyen, H. P., Mai, H. T. A., Mai, T. H. T., and Hoang, P. L. (2024). A comprehensive study on factors influencing online impulse buying behavior: evidence from Shopee video platform. Heliyon 10:e35743. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35743

Niu, X., Wang, X., and Liu, Z. (2021). When I feel invaded, I will avoid it: the effect of advertising invasiveness on consumers’ avoidance of social media advertising. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 58:102320. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102320

Nyrhinen, J., Sirola, A., Koskelainen, T., Munnukka, J., and Wilska, T.-A. (2024). Online antecedents for young consumers’ impulse buying behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 153:108129. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2023.108129

Obadă, D. R. (2015). Impactul stării de flux din mediul online asupra calității percepute a unui site web de brand. Bucharest, Romania: Pro Universitaria.

Obadă, D. R., and Dabija, D. C. (2022). “In flow”! Why do users share fake news about environmentally friendly brands on social media? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:4861. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084861

Omar, B., and Dequan, W. (2020). Watch, share or create: the influence of personality traits and user motivation on TikTok mobile video usage. Int. J. Interact. Mobile Technol. 14, 121–137. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v14i04.12429

Pelet, J. É., Ettis, S., and Cowart, K. (2017). Optimal experience of flow enhanced by telepresence: evidence from social media use. Inf. Manag. 54, 115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2016.05.001

Pintado, T., Sanchez, J., Carcelén, S., and Alameda, D. (2017). The effects of digital media advertising content on message acceptance or rejection: brand trust as a moderating factor. J. Internet Commer. 16, 364–384. doi: 10.1080/15332861.2017.1396079

Pop, R., Săplăcan, Z., Dabija, D. C., and Alt, M. A. (2022). The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: the role of Trust in Consumer Decision Journey. Curr. Issue Tour. 25, 823–843. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2021.1895729

Qin, Y., Omar, B., and Musetti, A. (2022). The addiction behavior of short-form video app TikTok: the information quality and system quality perspective. Front. Psychol. 13:932805. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.932805

Qu, Y., Khan, J., Su, Y., Tong, J., and Zhao, S. (2023). Impulse buying tendency in live-stream commerce: the role of viewing frequency and anticipated emotions influencing scarcity-induced purchase decision. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 75:103534. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103534

Quintas-Froufe, N., González-Neira, A., and Fiaño-Salinas, C. (2024). Corporate policies to protect against disinformation for young audiences: the case of TikTok. Front. Commun. 9:1410100. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1410100

Redondo, I., and Aznar, G. (2018). To use or not to use ad blockers? The roles of knowledge of ad blockers and attitude toward online advertising. Telemat. Inform. 35, 1607–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.04.008

Ren, Z. B., Dimant, E., and Schweitzer, M. (2023). Beyond belief: how social engagement motives influence the spread of conspiracy theories. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 104:104421. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104421

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., and Becker, J. M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. Available at https://www.smartpls.com/

Roberts, J. A., and David, M. E. (2023). Instagram and TikTok flow states and their association with psychological well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 26, 80–89. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2022.0117

Rook, D. W., and Fisher, R. J. (1995). Normative influences on impulsive buying behavior. J. Consum. Res. 22, 305–313. doi: 10.1086/209452

Scherr, S., and Wang, K. (2021). Explaining the success of social media with gratification niches: motivations behind daytime, nighttime, and active use of TikTok in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 124:106893. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106893

Sharabati, A.-A. A., Al-Haddad, S., Al-Khasawneh, M., Nababteh, N., Mohammad, M., and Abu Ghoush, Q. (2022). The impact of TikTok user satisfaction on continuous intention to use the application. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex 8:125. doi: 10.3390/joitmc8030125

Sharma, A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Arya, V., and Siddiqui, M. Q. (2021). Does SMS advertising still have relevance to increase consumer purchase intention? A hybrid PLS-SEM-neural network modelling approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 124:106919. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106919

Shi, J., Li, G., Zhao, Y., Nie, Q., Xue, S., Lv, Y., et al. (2022). Communication mechanism and optimization strategies of short fitness-based videos on TikTok during COVID-19 epidemic period in China. Front. Commun. 7:778782. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.778782