- The Department of Communication Studies, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, United States

This study examines the ways widely circulated U.S. newspapers have articulated the idea of “speciesism” and its associated idea “animal rights” in relation to “racism” to understand how powerful news media helps to shape the public understanding of the interlocking systems of oppression that cuts across the human and the more-than-human world. The archives (1987 to 2023) of three U.S. newspapers – The New York Times, USA Today, and The Washington Post – were analyzed, using qualitative content analysis. The ideas of articulation, symbolic annihilation, erasure, and discursive closure served as the analytical guides for the analysis. The analysis shows that there is gross underrepresentation of speciesism and even far less representation of the relationship between speciesism and racism and between animal rights and anti-racism. When represented, the articulations showed problematic patterns of erasure of those concepts and relationships. The paper ends with the implications of the findings.

1 Introduction

The term speciesism was first used in 1970 by psychologist Richard Ryder in a leaflet against animal experimentation and hunting he wrote and distributed among a group of intellectuals in Oxford. He called for “the suffering of imprisonment, fear and boredom as well as physical pain” be considered an important moral criterion and argued that mistreatment of other species to benefit our own species “is still just ‘speciesism’, and as such it is a selfish emotional argument rather than a reasoned one” (Ryder, 2011, 61). Philosopher Tom Regan (2004) adopted Ryder’s definition and summarized it as “the kind of prejudice toward animals that are … comparable to the prejudice of racism and sexism” (408). Peter Singer, a philosopher who is generally regarded as the foremost catalyst of the modern animal rights movement, was a graduate student at Oxford at that time and encountered the leaflet and later adopted the term when he published Animal Liberation in 1975 and popularized the term. The singer defined speciesism as “a prejudice or attitude of bias in favor of the interests of members of one’s own species and against those of members of other species” (Singer, 2015, 35). Although this definition could apply to non-human situations (e.g., a dog preferring other dogs over cats) (see Ryder, 2011), as a matter of moral philosophy and practice, speciesism has been discoursed and debated as a human phenomenon.

Growing academic discourses describe speciesism as an integral part of the systems of oppression created by the colonial, industrialized, capitalist world (Nibert, 2015). As part of the intersectional epistemology movement (Crenshaw, 1989), scholars across the disciplines have argued that speciesism is a social justice issue that is intricately related to other injustices such as racism, sexism, homophobia, and ablism (Almiron et al., 2018; Jones, 2015). The idea of speciesism has become a widely shared interdisciplinary concern (Dhont et al., 2019; Nussbaum, 2022; Swartz and Mishler, 2022). Yet, this concern is not widely shared in the public sphere where intersectionality has become a mainstream vocabulary. To understand potential reasons for this gap, this study investigates the ways mainstream commercial newspapers in the United States have represented the idea of “speciesism” – and its associated idea, “animal rights” – and its connection to “racism.”

The role of the media in constructing public opinion cannot be overstated. Media representation matters because it has real psychological, cognitive, and material impacts on the audience. Agenda-setting, perhaps the most widely known theory to capture the impacts, posits that the issues covered in the media frequently and prominently also become the important issues in the mind of the public (McCombs and Shaw, 1972). The audience does not necessarily differentiate between the media outlets, but they tend to “share the media’s composite definition of what is important” (McCombs and Shaw, 1972, 184). That is, collective representations across media outlets matter. Over four decades of robust research has shown that agenda-setting form, prime, and shape public opinions (Kim et al., 2017; Valenzuela and McCombs, 2019). The media’s attention to an issue encourages the public to form opinions about the issue. The media highlighting certain elements of the issue primes the audience’s opinions about the issue as the audience tends not to conduct comprehensive research of their own. Finally, the way the media presents the issue by the attributes included and the tone used for the attributes – the attribute agenda – shape the audience’s opinions about the issue (Valenzuela and McCombs, 2019; Williams et al., 2022). Thus, what and how of the media shape public agenda.

Kim et al.’s (2017) meta-analysis of agenda-setting studies over four decades showed that environmental issues are the third most popular topic. Some agenda-setting research examined animal-related issues (e.g., Fitzgerald et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023), but little research exists on how news media covers speciesism and/or animal rights and their interactions with racism. Today, newspapers continue to play a vital role in democracy, keeping citizens informed, mobilizing people around various issues, and serving as watchdog of power abuse (Tavares, 2019). To better understand the role of print press in the public discourse of the intersection of racial oppression and oppression of non-human animals, this study takes a close look at three U.S. newspapers – The New York Times, USA Today, and The Washington Post – for their articulation of speciesism – and animal rights – in conjunction with racism and the discursive devices they used to achieve the articulation. Specifically, the study examines how the articles represent or fail to represent speciesism and the interlocking nature of speciesism – or animal rights – and racism through articulation.

2 Literature review

2.1 Conceptualizing speciesism

Those who advocate for anti-speciesism have done so on different grounds, though the influence of Jeremy Bentham, a 18th century utilitarian philosopher and one of the first advocates of animal rights, is evident in contemporary work. Bentham argued that the relevant question about the treatment of nonhuman animals is not whether they can reason or talk “But can they suffer?” (Singer, 2015, 36). Following Bentham, Singer (2015) reasoned that, because sentient nonhuman species have an interest in not suffering, humans must give equal consideration for that interest. As a utilitarian ethicist, he called for minimizing suffering and maximizing happiness for the largest number. In contrast to Singer, in The case for animal rights (2004), first published in 1983, Tom Regan took a rights-based approach and suggested that nonhuman animals are subjects-of-life who have desires, preferences, and experiences and are therefore “have a value of their own, logically independently of their utility for others and of their being the object of anyone’s interests” (384). Each individual nonhuman who is a subject-of-life has a right to respectful treatment as a possessor of the inherent value. Reagan objected to the utilitarian theory, noting that appealing to aggregate consequences does not lead to better treatment of animals. Ryder (2011) then introduced painism that combined utilitarianism and rights theory and builds on the tradition of Bentham. Individuals, Ryder argued, have a right not to suffer pain whether it is “sensory, cognitive or emotional” (84). There are thus important philosophical differences among anti-speciesism scholars about the fundamental criterion for their advocacy, but they all agree that species membership is not a morally acceptable reason for oppression.

There are at least two other important commonalties the advocates of anti-speciesism share. The first may be obvious, but those who call out speciesism one way or another are advocates of animal rights. Singer (2015) started the first chapter of Animal Liberation with this passage:

“Animal Liberation” may sound more like a parody of other liberation movements than a serious objective. The idea of “The Rights of Animals” actually was once used to parody the case for women’s rights. When Mary Wollstonecraft, a forerunner of today’s feminists, published her Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, her views were widely regarded as absurd, and before long an anonymous publication appeared entitled A Vindication of the Rights of Brutes.

From here, he developed his argument for equal rights for women and people of color and applies the same logic for nonhuman animals as a matter of morality. Tom Regan (2004) held that individual animals who are subjects-of-life have inherent rights that must be protected. For him, prescription of equality (as Singer argues) does not guarantee the actual protection. Steven Wise, a late animal rights lawyer, was among those who were deeply inspired by the works of moral philosophers such as Singer and Reagan (Wise, n.d.). Wise founded the Nonhuman Rights Project to dedicate his life to tackling speciesism by way of seeking legal rights for some animals. More recently, philosopher and political scientist Nussbaum (2022) called for theoretical and legal reforms to recognize the rights of animals in order to address ecological collapses that resulted from human domination and exploitation of animals. Thus, although definitions may differ, anti-speciesism goes hand in hand with animal rights.

Another important commonality that scholar-advocates share is referencing social maladies within the human world in making a case for anti-speciesism. Ryder (2011) contended that speciesism is a prejudice like sexism or racism. Singer (2015) put the analogy this way:

Racists violate the principle of equality by giving greater weight to the interests of members of their own race when there is a clash between their interests and the interests of those of another race. Sexists violate the principle of equality by favoring the interests of their own sex. Similarly, speciesists allow the interests of their own species to override the greater interests of members of other species. The pattern is identical in each case. (38–39)

Tom Regan (2004), too, referenced racism in advancing his rights theory; both racism and speciesism rely on making another group worse-off, and they violate the inherent value of that group.

The language we use reveals this parallel logic. Dunayer (2001) concluded that sexism, racism, and speciesism are all forms of “self-aggrandized prejudice” (1). In making the point that generic language strategically erases the individuality of each life, Dunayer connected racism to speciesism: “Just as racists have spoken of blacks as ‘the Negro’ and Jews as ‘the Jew,’ people speak of all members of a nonhuman group as if they were a single animal, implying that they are all the same” (6). This deprivation of individuality erases them as subjects-of-life (Tom Regan, 2004). The language we use not only reflects our thinking but actively organizes our thought-process. The very idea of “species” that we take for granted as a biological fact may contribute to speciesism. In Speciesism in biology and culture, Swartz and Mishler (2022) observed that, just as racism is based on the assumptions that races are biologically real and that one or more of the races are superior to others, speciesism relies on the assumptions that species are real, and one or more species are superior to others. A “species,” they argued, does not have a consistent taxonomy across mammals, plants, and fungi, whereas lineages show biological relationships among living things. Races are social constructs and are not biological categories, but insisting on the latter matters “because how we see ourselves influences how we treat other people (racism) and how we treat other living things (speciesism)” (11).

If those philosophers emphasized the parallel of logic between speciesism and racism, others drew psychological connections between them. Dhont et al. (2019) reviewed a series of research, their own and others, and concluded that “speciesism is a type of prejudice, reliably related to prejudicial attitude towards a range of human outgroups,” including ethnic, racial, and sexual minorities (35). Social Dominance Theory provided a clue. According to the theory, social dominators (those who want to preserve hierarchical social structures and advance the dominant status of the advantaged groups) use discriminatory systems such as racism and sexism to rationalize and support the moral legitimacy of institutionalizing discriminatory policies. Social dominators have been found to hold a strong human supremacy view and defended animal exploitation such as hunting, factory farming, and the use of animals for testing and entertainment (Caviola et al., 2019; Dhont et al., 2019; Dhont et al., 2016). Another study (Costello and Hodson, 2010) found a correlation between sharp human-animal divide and dehumanization of human outgroup (e.g., immigrants). Thus, while social justice movements tend to ignore animal rights concerns (Kymlicka and Donaldson, 2014), psychological research has demonstrated that speciesism and racism (and other discriminatory human systems) not only rely on the same logic but are psychologically related.

2.2 Entanglement of oppression, entanglement of liberation

The correlation between speciesism and racism (and other discriminatory human systems) is not just psychological. Various forms of oppression are systemically and institutionally interconnected. Four decades ago, Audre Lorde, self-described “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” called out the inadequacy of focusing on one form of oppression: “[t]here is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives” (Lorde, 2012, p. 138). A legal scholar, Crenshaw (1989) gave a name to these multi-issued lives – intersectionality – as a tool to account for the double oppression experienced by Black women due to racism and sexism. Since then, intersectionality has become a mainstream vocabulary and lens for making visible multiple forms of discrimination simultaneously experienced by minoritized people due to racism, sexism, sexual orientation, class and more in a wide range of contexts from health to organization to environmental. Climate change studies, for instance, have used intersectionality to examine the ways in which systems of disadvantages and oppression intersect to restrict or worsen people’s climate adaptation capacity (Amorim-Maia et al., 2022).

Intersectionality has been predominantly used to examine human experiences. Yet, if systems of oppression are interlocked, it follows that speciesism and racism also overlap and are entangled with each other. A highly publicized case of a former NFL star Michael Vick, who was convicted of running an unlawful dog fighting operation, illustrates this entanglement (Broad Garrett, 2013; Harper, 2011). Critical race theorist Harper (2011), for example, argued that the public condemnation he received sharply contrasts to the normalization and even heroization of hunting, an overwhelmingly a white male activity. While Vick’s animal cruelty was no doubt vile, his action was also racialized while whiteness masks the violence of hunting. Before Harper, other black woman scholar-writer-activists known for their fierce advocacy for social justice articulated the entanglement of oppression. Alice Walker, for instance, has long written about human exploitation of nonhuman animals and its relationship to racism and sexism at least since the essay, Am I Blue. In the essay, Walker (1987) described her encounter with and learning from a horse named Blue and meditated on the cruelties against nonhuman animals, women, and Blacks and the threads between them. Similarly, Davis (2012) has spoken out about animal suffering caused by capitalist, industrial forms of food production as a critical issue within the interlocking systems of oppression.

To be sure, social justice movements have been largely quiet about nonhuman animal oppression, fearing that including it may weaken or even hurt their causes (Freeman, 2020; Kymlicka and Donaldson, 2014). The literature reviewed in this and earlier sections, however, suggest that systems of oppression, including both humans and non-human animals, are overlapping and interlocked in our multi-issue lives. Moreover, in her examination of three types of social movements (human rights, animal protection, and environmentalism), Freeman (2020) identified core values (e.g., fairness, responsibility, compassion) shared by the social movements that have not historically allied with each other and called for them to work together to protect all life on earth. A path to liberation then begins with articulating the entanglement and commonalities. Here, the media has an unparalleled power in representing and shaping discourse.

2.3 Analytical framework: articulation, symbolic annihilation, erasure, and discursive closure

Articulation, given shape by the concepts of symbolic annihilation, erasure, and discursive closure, serves as a productive lens to examine media discourse. Articulation brings, or sutures (Hall, 1985), two or more elements together to produce social meaning. Those elements are not inherently related to each other but are linked contingently in the given historical moment. It is a unity that is produced by ideological, political, and social forces; certain belief systems, political contingencies, or social imperatives usher articulation (Kinefuchi, 2015). When those elements are brought together, it creates a meaning. Something that was ignored previously, for example, can be articulated as precious or valuable. Conversely, something that was previously valued can be rendered worthless. Thus, articulation has the potential to empower or disempower an identity or a way of imagining and acting in the world (Hall, 1985; Slack, 1996). Articulation may involve specific use of language, imageries, tones, arrangements, and references to produce such empowerment or disempowerment. For example, those who want to give salience to animal suffering may use vivid, concrete, and personalized language to describe the suffering, whereas those with an opposite agenda may use abstraction, generalization, and homogenization to deflate the salience of the problem (Stibbe, 2021).

Articulation is shaped not only by what are linked together but what is excluded. Hall (1996) alerted that every articulation has its excess; that is, an identity relies also on the production of the adjected and marginalized. Thus, the language, the tones, the arrangements, and the references that are excluded from symbolic representation are just as important. Here, symbolic annihilation, discursive closure, and erasure together can provide insights into media’s agenda-setting. Symbolic annihilation originally referred to the lack of representation of groups on the television (Gerbner and Gross, 1976). Gaye Tuchman picked up the concept in her 1978 study of women’s representation in the media and extended it to not only signify absence but also condemnation and trivialization of women (Tuchman, 2000). She argued that few women are represented in the mass media in the first place (absence); and, when they are represented, they are condemned (in the case of working women) or trivialized (as someone who needs protection). All those cases, according to Tuchman, symbolically annihilate women. Since then, the concept has been used to examine the representation of gender, race, sexual orientation, and age (Merskin, 1998; Coleman and Yochim, 2008; Klein and Shiffman, 2009; Gutsche et al., 2022).

Symbolic annihilation thus far has been applied to the media representation of human groups, but it is instructive in understanding the symbolic marginalization of nonhuman animals and the ways oppressions in the human world and the more-than-human world intersect. In fact, ecolinguist Stibbe (2021) used erasure to convey an idea similar to symbolic annihilation. Erasure, he explained, is an appraisal of something as “unimportant or unworthy of consideration,” and erasure becomes a pattern when the appraisal becomes “systematic absence, backgrounding or distortion in texts” (141). Stibbe explains that erasure comes in several types: the void (complete exclusion from a text), the mask (the use of replacement or distortion), and the trace (partial presence). Distortion can be also achieved by discursive closure – a systematic distortion of communication employed to suppress alternative or conflicting discourses (Deetz, 1992). Stanley Deetz proposed this idea to explain communication strategies that are deployed to legitimize certain reasoning while marginalizing other perspectives in service of corporate colonization of the life world. While the strategies were originally discussed in organizational and interpersonal contexts, they can shed light on the ways news media may produce erasure. Some of the strategies– naturalization (removal of social and historical processes), neutralization (pretense of objectivity), and legitimation (appeal to higher order explanatory values) – are particularly relevant to distortion.

Those theoretical insights suggest potential articulations. The subject may be substantially present and given salience. It may be partially present and backgrounded. It may be present but distorted by condemnation, trivialization, backgrounding, or through discursive closure strategies such as naturalization, neutralization, and legitimation. It may be completely absent. News media could consciously and unconsciously employ any or all of those strategies to set agenda and shape public opinions. This study thus considers all those possibilities.

2.4 Research goal

As reviewed above, scholars across disciplines have argued that speciesism and racism are interlocking systems of oppression. If they are interlocked, then, it needs to be articulated in public discourse so public deliberation can occur and a path to liberation may be envisioned. Given the influential role that news media plays in the construction of the social world by way of forming, priming, and shaping public opinion, newspapers are a ripe site for the examination of articulation. My original interest was on the appearance of the idea of “speciesism” in newspapers and its co-appearance with “racism.” However, my archival search with this focus yielded remarkably few results – a finding that in itself is noteworthy and will be discussed later. As a result, I expanded the search to also find the co-appearance of “animal rights” and “racism.” As discussed above, those who advocate for anti-speciesism are advocates for animal rights one way or another. “Animal rights,” therefore, serves as a companion keyword or a proxy for anti-speciesism. This expanded search resulted in more data for the study.

To understand news media’s contribution to the public discourse of the intersection between racial oppression and nonhuman animal oppression, this study investigates how newspaper articles represent or fail to represent speciesism and the interlocking nature of speciesism (or animal rights) and racism through articulation. Three national newspapers in the United States were chosen for the study: The New York Times (1923-present), USA Today (1982-present) and The Washington Post (1877-present) (Majid, 2023). They are the largest comprehensive daily national newspapers in the county after business and economic-focused Wall Street Journal.

3 Methods

3.1 Data collection

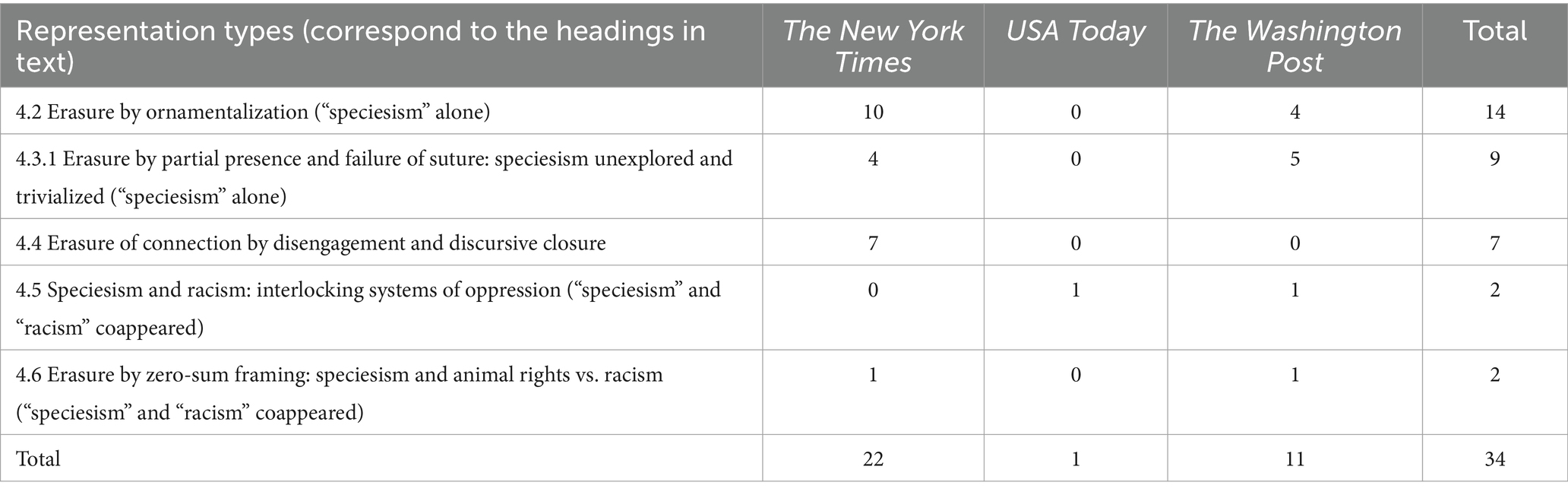

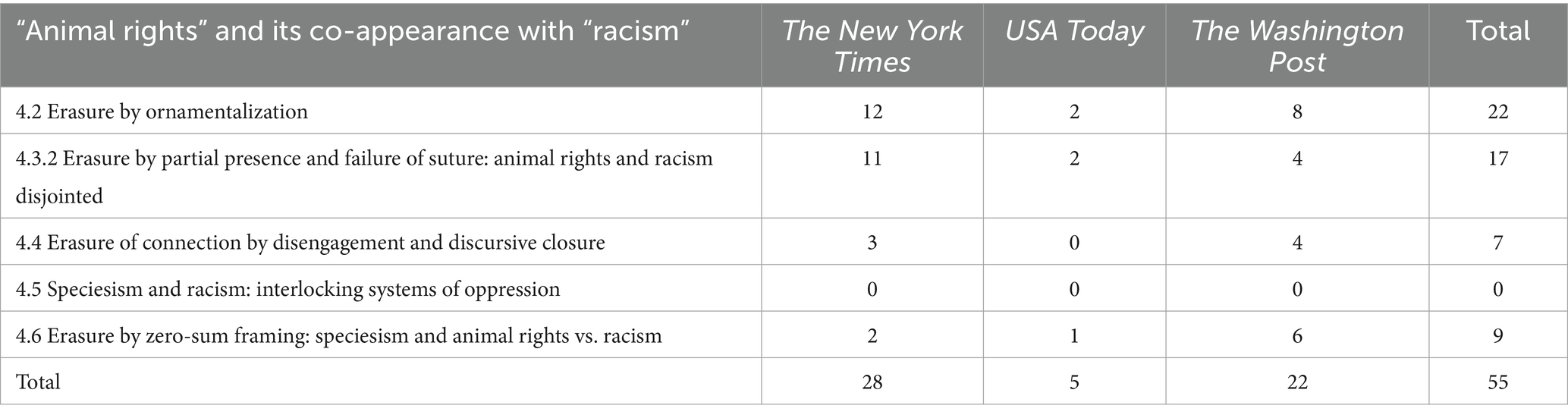

ProQuest was used to search for relevant articles from The New York Times (NYT), USA Today (USA), and The Washington Post (WP). The study covers the years from1987 (when the archives were available for all three papers) to 2023. The data collection proceeded in two phases. The first phase searched the archives for “speciesism” as the core word, which yielded very few results. The second phase looked for the articles in which “animal rights” co-appeared with “racism.” The results of the searches are summarized in Tables 1, 2. Between 1987 and 2023, the three newspapers collectively published 89 articles that included “speciesism” or the combination of “animal rights” with “racism.” The articles ranged in length (3–4 pages to a couple of sentences) and forms (e.g., feature stories, editorials, letters to the editor, book reviews). A few articles appeared in both phases 1 and 2 as they contained both core words (“speciesism” as well as the combination of “animal rights” and “racism”). Those articles were counted for “speciesism” in the tables to avoid duplicate counting.

3.2 Data analysis

Qualitative content analysis (Schreier, 2012) was used to examine the newspaper articles. Each of the 89 articles was first read through and was summarized for the content. Then, a second read-through was performed to begin to examine the articulation or how the articles help or fail to represent speciesism and the interlocking nature of speciesism (or animal rights) and racism. Those initial read-throughs made it apparent that the vitality of the articulation varied widely, and it was in part a function of the degree of centrality of the concept and association (speciesism, speciesism with racism, and animal rights with racism). One article, for example, engaged the idea of speciesism as part of the central message, whereas another article mentioned the word in passing in a story that was entirely about something else. The latter was determined to have little vitality as it is unlikely that the idea was registered in the mind of the reader. Similarly, the representation of animal rights with racism varied from demonstrably linking those ideas to each other to failing to do so.

The tone of an article also affects vitality. Continuing the same examples, one article was sympathetic to represent non-human animals’ plights and outlined the consequences of speciesism for their audience. In contrast, another article dismissed the whole idea of speciesism or its relationship to racism. In other words, the author situated themselves variously in relation to the given concept from affirmation to neutrality to indifference to rejection. Thus, the articles were coded for both the centrality of the core words (“speciesism” and “animal rights”) within the articles and their tone regarding the core words’ relationships with “racism.” The use of linguistic devices such as personalization and concreteness (Stibbe, 2021) and discursive closure strategies (Deetz, 1992) to establish the centrality and tone were also examined.

At the nexus of centrality and tone, several categories were created. The results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 and are discussed in the next section. The final categories were generated after three iterations over three weeks to ensure the categories’ stability and fidelity to represent the 89 articles. The emergent flexibility nature of qualitative content analysis (Schreier, 2012) enabled the analysis to be truthful to the data while also allowing the analytical framework to provide organization.

4 Results and discussion

This section discusses the articulation of (1) the idea of “speciesism” alone and in conjunction with “racism” and (2) “animal rights” with “racism” in order to understand how the three widely circulated U.S. newspapers discourse – and thus construct – the intersection of systems that oppress humans and non-human animals. The results will not include a discussion of comparisons across the three newspapers. Although there are quantitative differences between the newspapers (e.g., USA had the least number of articles), the overall numbers of relevant articles, as discussed below, were small across the board. Qualitatively, the articulations (or disarticulations) were characterized by patterns of erasure and discursive strategies across the newspapers.

4.1 Erasure by absence

Before discussing the articulation of “speciesism” and “animal rights” with “racism,” the gross absence of those words is worth the mention. As shown in Table 1, in almost four decades since 1987, “speciesism” made mere 34 appearances in total across the three newspapers: 22 times in NYT, 11 times in WP, and just one time in USA. The co-appearance of “animal rights” with “racism” fared not much better; across the three newspapers, “animal rights” co-appeared 55 times with “racism.” Those numbers are strikingly low when one considers that, over 36 years, the three daily newspapers collectively published roughly 39,420 papers (excluding evening editions). The 34 appearances of “speciesism” (or less than 0.1 percent) and the 55 co-appearances (or 0.1 percent) of “animal rights” with “racism” make those concepts and their associations virtually nonexistent in the eyes of the mainstream media institutions. The number is even lower, as will be discussed later, when the articles without meaningful engagement with the concepts are filtered out.

Representation is consequential because, for anything to not just exist (as things do have material existence) but meaningfully exist in the world, they must be symbolically represented (Hall, 1997). When something is not represented, then it cannot have a meaningful existence for anyone to reflect and act upon. The utter underrepresentation of “speciesism” in the most widely circulated national newspapers is symbolic annihilation (Tuchman, 2000) and the void (Stibbe, 2021) as it obliterates the existence of the phenomenon. A quick search for the word in Google Scholar yielded 21,300 results. Yet, if the word has not been in use in the mainstream media, the public is less likely to know the word in the first place, let alone seek information about the oppression of nonhuman animals. With the void, they are less likely to connect the dots between our daily, normative practices and the suffering of nonhuman animals. Without the word in circulation, the opportunity to imagine the connection between speciesism, racism, sexism, and other forms of systemic oppressions is already excluded. Similarly, the paucity of the co-appearance of “animal rights” with “racism” indicates widespread disinterest of the news giants to entertain the possibility of intersectional discourse between oppressions within the human sphere and those concerning the more-than-human spheres, rendering the oppressions of the two spheres unrelated to each other. It creates a void by symbolically annihilating the possibility. The next section shows that symbolic annihilation continues even when the words are referenced in the newspapers.

4.2 Erasure by ornamentalization

Mere inclusion of a concept does not represent the concept. Out of the 34 articles across the three newspapers that included the word “speciesism,” 14 (ten NYT and four WP) or 41% did so ornamentally (see 4.2 in Table 1). That is, the word’s presence was extraneous to the articles’ main topics. For example, ‘Naomi Schor, Literary Critic and Theorist, Is Dead at 58″ (NYT, December 16, 2001) outlined Schor’s intellectual contributions. The very end of the article mentions “Men and Beast,” a conference that she had helped to plan. It is in this context that “speciesism” was mentioned once. The article explained that the conference would explore the relationship between humans and animals “perhaps under the rubric of speciesism.” For another example, “Can Artificial Intelligence Invent?” (NYT, July 17, 2023) is a 3-page article (in pdf) about whether AIs that invent should be legally recognized as inventors. The article included a comment from a man who created an AI that can invent. He complained that the reluctance of patent authorities to recognize his AI as an inventor as a discrimination and was quoted to say, “It’s speciesism to me.” For the last example, “Unabomber Parable: Overthrow Authority” (WP, August 25, 1999) is a short article informing that Unabomber (Theodore Kaczynski) wrote a short fiction in his prison cell. It included a statement uttered by a character in the fiction: “It’s racism, sexism, speciesism, homophobia and exploitation of the working class! It’s discrimination!” In those 14 articles, “speciesism” was peripherally mentioned once without further engagement.

A similar conclusion applies to “animal rights” and “racism.” There were 55 articles in which “animal rights” and “racism” co-appeared (see 4.2 in Table 2). However, 39 of them (23 NYT, four USA, and 12 WP) or 40% did not connect the two concepts with each other (see 4.2 and 4.3 in Table 2). For 22 of the 39 articles, neither concept was central to the articles but was ornamental. For example, a NYT article reported that universities and colleges are implementing various freshman courses as a retention measure (“Survival Courses for Freshmen,” November 6, 1988), and racism and animal rights were simply mentioned as part of the topics in some of the courses. USA had an article about a man who runs a business to stand in front of the White House and stage protests on others’ behalf (“An Hourly Fee Buys White House Banner,” August 15, 2001). The man has stood there for all kinds of political and social issues – gun control, gun rights, AIDS, gay rights, animal rights, child support, anti-abortion, women’s right to choose and more. According to the man, the only clients he does not accept are those who want to promote violence and racism. Similarly, WP listed a series of social issues in an article about protest costumes; each activist cause has its unique protest costume whether it is about the environment, racism, the global economy, legalizing marijuana, gun control or animal rights (“From Bellbottoms and Beads to Casual Friday Protest Apparel,” April 19, 2002). These and other 19 articles listed “animal rights” and “racism” as part of many social issues, but neither concept was central to the articles; they could have been written without them.

When the presence of a word is simply ornamental, it is not essential to the article. The presence of a serious phenomenon that the word was tasked to represent fails when it is buried among other words and does not receive further attention. Stibbe (2021) observed that animals and plants are erased from discourse when they are simply a faint trace; referencing them for their functions for humans, for example, creates this erasure. News articles’ ornamental use of words such as “speciesism” and the host of other social issues can also erase those issues. Without elaboration, their presence is backgrounded as one of many omnipresent challenges in human society and unlikely to register in the readers’ minds.

4.3 Erasure by partial presence and failure of suture

4.3.1 Speciesism unexplored and trivialized

Nine articles (4 NYT and 5 WP) mentioned “speciesism” without “racism,” but, unlike ornamentalization, it was either the main topic or important to the main topic of the article (see 4.3.1 in Table 1). However, the idea of speciesism remained unexplored with often trivializing or even hostile tones. The articles ranged from six sentences to 3 pages (in pdf) and were diverse in topic. An example from NYT is a 3-page article about Argentine boar hunters feeling threatened by animal rights activists who tried to block a hunting tournament (“Argentine Hunters Feel Besieged by Critics ‘Made of Asphalt’,” August 26, 2016). The article included an animal rights lawyer’s comment that hunting “fosters speciesism – a school of thoughts that emphasizes the moral superiority of humans over animals” but failed to engage this comment and quickly returned to the hunters’ perspective; the hunters were portrayed as defending their heritage, and the article gave the last words to a hunter; “It’s a way of life.” Another NYT example is a 2-page article on Peter Singer receiving the 2021 Berggruen Prize, an award given annually to a thinker who has “profoundly shaped human self-understanding and advancement in a rapidly changing world” (“Directing Philanthropy to Do the Most Good,” September 8, 2021). This article curiously devoted just two sentences to his work on animal rights and his argument against speciesism, while acknowledging that it was Animal Liberation that brought him worldwide fame. WP had an article reported on the international outcry over a road-raged driver killing another driver’s dog by throwing the dog into traffic (“The cuddliness of a Victim Shouldn’t Influence the Severity of Punishment,” June 20, 2001). The author felt that the outcry reflected speciesism, because people would not have cared if the killed pet was a rat. Another WP reported on JetBlue’s dilemma regarding which animals they allow in the main cabin as emotional-support animals. It mockingly referenced speciesism: “the Charybdis of animal advocates who are hypersensitive to speciesism, a.k.a. anti-pet fascism” (“Emotional-Support Snakes on a Plane,” February 8, 2008).

In those and other five articles, “speciesism” was mentioned and was relevant to the main topic of the article, but none of them dedicated further space to engage the concept. Rather, the concept was brushed off or mocked. Although newspapers have limited spaces, there were opportunities for engagement. For example, Peter Singer’s story could have explained speciesism and its connection to racism, which is central to Singer’s argument. Or the article about the emotional support animals had an opportunity to explore implications of this industry rather than equating the objection to speciesism with fascism. As the opportunities for deeper and serious engagement were missed, the idea of speciesism remained trivialized (Tuchman, 2000).

4.3.2 Animal rights and racism disjointed

Of the 55 articles in which “animal rights” and “racism” co-appeared, 17 (11 NYT, 2 USA, and 4 WP) did not link the two concepts with each other, but their main topics were relevant to either animal rights or racism (see 4.3.2 in Table 2). Those articles could have potentially brought the two concepts into a productive conversation but did not do so. A letter to the editor in USA (“Do not let it happen again,” May 5, 1993) chastised the newspaper for putting Rush Limbaugh on its front page. The letter writer described him as someone who denigrates all groups, calling women as “feminazis” and animal-rights and environmental advocates as “wackos,” and mocking speech of African Americans under the guise of humor. Another example is a WP article about Benjamin Zephaniah, a British writer and poet who passed away (“British Poet and Activist Known as the ‘People’s Laureate’,” December 22, 2023). The article described his work as reflections on “racism and injustices faced by Black communities in Britain” and issues of “the environment and animal rights.” Thus, a recurrent pattern in this group of articles is to list “animal rights” and “(anti-)racism” as belonging together to something or someone, but the connection between the two concepts were unarticulated.

A more telling example of this pattern is a NYT op-ed, “State of Shame” (June 9, 2009). The article shed light on the harsh condition in which farmworkers in New York work. Early on, it referenced animal rights as a way to introduce the main topic:

Animal-rights advocates have made a big deal about the way the ducks are force-fed to produce the enormously swollen livers from which the foie gras is made. But I’ve been looking at the plight of the underpaid, overworked and often gruesomely exploited farmworkers who feed and otherwise care for the ducks. Their lives are hard.

Each feeder, for example, is responsible for feeding 200 to 300 (or more) ducks – individually – three times a day. The feeder holds a duck between his or her knees, inserts a tube down the duck’s throat, and uses a motorized funnel to force the feed into the bird. Then on to the next duck, hour after hour, day after day, week after week.

This description was given to call attention to the brutal, non-stop work of farmworkers, most of whom are people of color. The op-ed went on to educate its readers about why farmworkers do not receive labor protections (racism and agriculture lobby). In another NYT article, “What Goes In, What Comes Out” (November 23, 2014), the author framed the problem of the Spam meatpacking industry in terms of human rights and racism while discounting concerns for animal rights. In both articles, the authors had options to solely focus on the human rights of the workers or to link the oppression of the workers to the cruelty against ducks or pigs. And the authors chose the former.

In sum, for the articles in this group, there were opportunities for articulating that animal rights and (anti-)racism belong to the same larger umbrella of justice and that they are linked systems. These opportunities unfortunately did not materialize. In some of the articles – like the cases of farmworkers and meatpacking workers – animal rights and human rights were presented as though they are either/or matters. Those missed opportunities and zero-sum representations symbolically annihilate (Tuchman, 2000) the link between systems of oppression that affect both humans and nonhuman animals.

4.4 Erasure of connection by disengagement and discursive closure

There were 11 articles (8 NYT, 1 USA, and 2 WP) that brought up “speciesism” in connection to “racism” (See 4.4 and 4.5 in Table 1). Seven of them, all from NYT, did so without exploring the connection. For example, an NYT article, “What to Put in the Pot: Cooks Face Challenge Over Animal Rights” (August 8, 1990), reported that animal rights campaigns are targeting restaurants and introduces the idea of speciesism, referencing Peter Singer, and noted how it is at odd with the norm:

Those who believe in the sanctity of animal life say speciesism is tantamount to racism or sexism. To a traditional meat-and-potatoes person, such thinking is almost anti-American. “The vegetarian agenda is at odds with our way of life,” said Kendal Frazier, a spokesman for the American Cattleman’s Association in Englewood, Colo.

The comparison of speciesism to racism and sexism was thrown in without any further explanation and immediately countered by the “tradition” logic. And the logic was further fortified by derision from the beloved celebrity chef, Julia Child: “Should I stop swatting flies? Should I invite mice into my kitchen and serve them lunch? This speciesism is specious.” And the author spent the rest of the article, building a case for restaurants, including a quote from a Manhattan chef saying “I am human. I eat meat.”

Another example is a review of David Grimm’s book, Citizen Canine: Our Evolving Relationship with Cats and Dogs (“Cats and Dogs Reigning,” April 18, 2014). Michiko Kakutani, one of the most eminent literary critics in the country, wrote that the book is “often fetching but highly uneven.” Kakutani felt that Grimm could have done a better job of covering animal rights and their changing status. She observed: “For instance, in discussing the controversial analogies that Mr. Francione and others have drawn between ‘speciesism,’ and human slavery, Mr. Grimm skims over the history of such arguments and the anger that such comparisons can understandably provoke.” She followed this assessment with a quote from the book where Grimm references enslavement of Africans, but she did not clarify why people may get angry. This anger is presumed to be shared by readers and forecloses a possibility of the comparisons to open a different path for justice advocacy.

Similar to the above cases for “speciesism,” seven articles (three NYT and four WP) linked “animal rights” with “racism” but failed to explain the link (see 4.4 in Table 2). A NYT article, “A Tangle in Sweden as Wolves, Now protected, Prey on Farmers’ Flocks” (August 15, 2015), is illustrative. The article discussed a conflict in Sweden between those who want to protect wolves (environmentalists and European officials) and those who are in favor of hunting them (farmers and hunters). The article gave fair space to both sides to represent the complexity of the conflict. Included was a comment from a spokesperson for the Wolf Association Sweden: “The hate against an animal, against a species such as the wolf, is like racism in people – it is absolutely the same process in the mind.” His declaration, however, hung in the air without a further explanation. For another example, a WP article, “Pit Bull Debate on Local Stage” (October 7, 2019), reported that pit bulls have been illegal in Prince George’s County since 1997, but animal rights activists are trying to overturn the law. The supporters of the ban emphasize the danger posed by the dogs whereas the opponents link the ban to racism and classism. The article, however, did not explain this link.

The articles in this group thus made connections between speciesism and racism (and sexism) or between animal rights and (anti-)racism, but they fell short of explaining how they are connected and what the connection means. This articulation without engagement could be more problematic than the absence of such in a culture where the idea of speciesism, as discussed earlier, is grossly absent from mainstream newspapers, and, as some articles above indicated, its comparison to human injustices is considered offensive. Furthermore, discursive closure strategies (Deetz, 1992) such as appealing to naturalization (inclusion of the quote, “I am human, I eat meat”), legitimization (a quote from a celebrity chef), and neutralization (anger being understandable) were employed to close further conversation about how speciesism and animal rights may intersect with racism, sexism, and human rights. Incomplete linking, coupled with discursive closure, can ultimately annihilate productive discourse about how various issues of oppression and justice overlap and intersect with each other.

4.5 Speciesism and racism: interlocking systems of oppression

So far, none of the articles across the three newspapers made a meaningful connection between speciesism and racism or between animal rights and racism. It is noteworthy that no newspaper made such a connection between animal rights and (anti-)racism (see 4.5 in Table 2). For speciesism, there were just two articles, one WP and one USA, that discussed and affirmed to some substantive extent the interlocking nature of speciesism and racism (see 4.5 in Table 1). The WP article (“Philosopher of Animal Rights,” June 9, 1990) is a 2-page (in pdf) op-ed about the contributions of Peter Singer to animal rights movements. The writer, Coleman McCarthy, wrote:

What Singer had done singularly is to give a name – speciesism – to the flawed intellectual reasoning that sanctions the slaughter of an estimated 10 million animals a day for food and several million a year by experimenters. Speciesism joins two other scourge ‘isms’ of the 20th century – racism and sexism – as unresolved torments imposed by the powerful on the weak. “Racists,” Singer writes, “violate the principle of equality by giving greater weight to the interests of members of their own race when there is a clash between their interests and the interests of those of another race. Sexists violate the principle of equality by favoring the interests of their own sex. Similarly, speciesists allow the interests of their own species to override the greater interests of members of other species. The pattern is identical in each case.”

One way a discursive subject may acquire salience is concreteness (Stibbe, 2021). McCarthy gives a concrete face (“the slaughter of 10 million a day for food and several million a year by experimenters”) to “speciesism” and places this phenomenon squarely with racism and sexism. By quoting Singer in length, he declared all three as operating under the same logic of oppressive power. He further advanced the case for anti-speciesism as a moral imperative and closed the article with the following note:

Speciesists can argue from custom: What’s Thanksgiving without a turkey? Or economics: Slaughterhouses provide jobs. Or the Bible: Jesus cast out devils by drowning swine. But habits, profits and scripture aren’t ethics. If there’s a book to answer Peter Singer- “Animal Enslavement”-it has yet to be written.

McCarthy maintained the connection between speciesism and racial injustice when he called the opposite of Animal Liberation as “animal enslavement.” If legitimization, or an appeal to dominant values, closes discourse (Deetz, 1992), he named those values to suggest their inadequacies from a moral and justice standpoint.

Interestingly, the USA article was also about Peter Singer (“He wrote the bible of animal rights,” March 7, 1990). The writer, Christopher John Farley, wrote about a new edition of Animal Liberation and how the book catalyzed animal rights activism since its original publication in 1975. As the title suggests, the article’s tone was affirmative of Singer’s contributions and animal rights activism. It connected speciesism to racism in the following passage: “Animal activists have also taken heat for comparing bias against animals—which they call “speciesism”—to racism and sexism. Some activists have even compared animal experimentation to the Holocaust.” Instead of dropping this provocative statement and moving on as other articles did, Farley stayed with it. He explained that Singer, too, referenced the Holocaust in Animal Liberation when he wrote that roughly 200 doctors experimented on Jewish, Russian, and Polish prisoners under the Nazi government. Singer then observed that this attitude has a striking parallel to that of animal experimenters. Based on his interview with Singer, Farley clarified that “Singer, who lost three of his grandparents during the Holocaust,” is comparing the attitude not the value of life. The point Farley wanted to get across about Singer’s view is revealed in another passage:

Singer wants to keep the pressure on. “(people) should be able to see that animals are creatures capable of suffering, capable of feeling pain,” he says. “And they should try to consider that pain as they would consider the pain of a human.” “Put yourself in the position of the animal that’s caught by the leg in a steel-jawed leg-hold trap. And then put yourself in the position of the woman that wants a fur coat and ask yourself if that’s really a fair balance—if the gain is enough to justify the pain and loss inflicted on the animal.”

Like McCarthy, Farley used concrete, vivid imageries (a steel-jawed leg-hold trap vs. a fur coat) to make the issue salient (Stibbe, 2021). Instead of leaving the potentially volatile reference to the Holocaust unexplained, he took care to explain the difference between a direct comparison and a similarity in logic – an important distinction that can lead to a productive conversation.

The readers of McCarthy and Farley may agree or disagree with them, but they were given materials for reflecting on the taken-for-granted human superiority and the overlapping injustices rather than simply given the word – “speciesism” – without an explanation as most other articles did. Still, from the point of view of representation and agenda-setting, two decent articles about speciesism and racism in almost four decades (1987–2023) is a drop in a tub. Moreover, it is remarkable that Farley was the sole USA article that included the word “speciesism” in all those decades. It is also significant that the only two articles that provided some substantive discussions about speciesism and its connection to racism were both about Peter Singer, and they were written within three months of each other in the same year – 1990. Over the last three decades, NYT, USA, and WP did not publish any article that discussed speciesism in any meaningful extent, let alone its relationship with racism. There have been opportunities for newspapers to take up this topic to advance public discourse. For example, returning to Michael Vick’s story, public responses were either clustered around animal cruelty and animal slavery or unfair punishment of a Black man, failing to address the intersection of speciesism and racism (Broad Garrett, 2013). Articulating the intersection could have led to conversations about interlocking systems of oppression. This was a lost opportunity for newspapers.

4.6 Erasure by zero-sum framing: speciesism and animal rights vs. racism

Finally, there were some articles that disarticulated the link between speciesism, animal rights, and racism. Three articles (two NYT and one WP) dismissed the relationship between speciesism and racism, and nine articles (two NYT, one USA, and six WP) rejected the relationship between animal rights and (anti-)racism (see 4.6 in Tables 1, 2). It is useful to discuss the two groups together as there are overlapping patterns across them. They all presented speciesism and animal rights on the one hand and racism on the other as a zero-sum game and employed a variety of discursive strategies to accomplish the antagonism. A few examples illustrate the strategies. A letter to the editor in WP (“Human Rights,” June 16, 1990) was an objection to McCarthy’s op-ed discussed above. The letter writer argued that speciesism is natural:

McCarthy agreed with Singer’s equation of speciesism, the belief in the primacy of one’s own species, with racism and sexism. But according to Darwin, the primary motivation of all life is the perpetuation of one’s species. Whether one species is “better” than another in abstract moral terms is irrelevant. The natural predilection toward speciesism is not evil, but the supreme law of nature.

He concludes his letter by declaring the anti-speciesist position absurd:

Humans cannot be both superior to animals and beholden to a “higher” standard of conduct than animals and be essentially the same as animals and therefore deserving of only the same rights as animals. This logical flaw in the core of the arguments of the anti-speciesists confirms the absurdity of their position. Of course there are real differences among species, and of course they matter.

A number of erasure strategies are at work in this letter. First, the writer naturalized and legitimized (Deetz, 1992) speciesism by appealing to a higher authority on life (Darwin), thereby declaring the matter closed. The writer exploited Darwin to advance speciesism, but it is worth noting that, according to a historical study (Vedantam, 2006), Darwin observed a parallel between speciesism and racism. In his trip to South America, Darwin, a devoted Christian, was enraged when he saw Catholic traders torturing slaves in manacles and realized that the slave trade relied on the logic that slaves are inferior species – an idea that he later extended to humans’ treatment of animals (Vedantam, 2006). Darwin would have disagreed with the letter writer’s appropriation of his work. Notwithstanding, the writer explained away as a matter of biology, for which humans owe no responsibility (but the same argument has been made for racism and sexism). The writer also condemned and trivialized (Tuchman, 2000) the idea of speciesism and the advocates of anti-speciesism by misrepresenting their arguments. Neither Singer nor McCarthy argued that there is no difference among species; in fact, Singer has been quite clear that there are meaningful differences between different animals that should be reflected in rights discourse and practices.

Erasure by condemnation and trivialization is thematic across the zero-sum game articles. Another letter to the editor in NYT (“Who Says a Lobster Outranks Broccoli?” August 23, 1990) responded to the aforementioned August 8 article, “What to Put in The Pot.” The letter writer was outraged by the article chosing to talk about animal rights when there were pressing injustices such as homelessness, medical care, children dying of bullets, and AIDS and had this to say about speciesism:

They even had the nerve to equate “speciesism” – “the presumption that humans are superior to other sentient creatures and therefore entitled to eat them”—with sexism and racism, thereby joining the ranks of racists and sexists themselves… Plant lovers could as well confront vegetarians at the produce counter as vegetarians confront fish and crustacean eaters at the seafood counter. Perhaps we should stop eating altogether, to protest the brutal rule of nature that requires living things to eat other living things to stay alive.

The writer went on to suggest that animal rights campaigners should confront nonhuman carnivores (lions, tigers, boa constrictors, etc.) about “their deplorable eating habits.” She disarticulated the relationship between speciesism and racism (and sexism) by condemning the very act of drawing the connection racist – naturalization based on a presupposition of a higher value (injustices in the human world being of the supreme order) incongruent with the oppression in the more-than-human world. The letter also derided the very idea of speciesism by using the slippery slope fallacy (suggesting that plant lovers confront vegetarians and that the animal rights advocates confront nonhuman animal carnivores) to naturalizes and mock speciesism, thereby foreclosing serious conversations about speciesism and intersecting systems of oppression.

This theme of condemnation and trivialization was also evident in an USA article, “But What About Human Suffering?” (April 25, 1991). The writer criticized the animal rights movement for not prioritizing humans:

Granted, it is possible to be an animal rights activist and still care about human issues, but I get no sense of human priorities in the movement’s rhetoric. I often wonder how many homeless and hungry people animal-rights activists climb over when they stage their public protests. How many of them are wearing textiles woven by women making minimum wage or less, or sporting polyesters stitched by women in Thailand who earn less than $1 an hour?

The writer then asked if those animal rights activists have the same view of all animals as she has never heard anyone calling for freeing the roaches. Next, she compared the public and governmental responses to save Humphrey the whale (several federal agencies coordinated the effort) to the lack of responsiveness of social services in improving housing projects. The article ended with a jeer of the animal rights movement:

Do those who allege that animals have souls want to give those souls the right to vote? Will they next suggest we are torturing carrots when we pull their roots from the earth?

From where I sit, a chicken has the right to jump into a sack of flour, be seasoned and fried to a crispy brown. And animal-rights activists need to take a hard look at human suffering.

The writer made some valid points. It is true that animal rights activists do not fight for all animal lives equally. Animal rights as a legal movement has focused on the animals that humans consider intelligent (e.g., great apes, elephants, dolphins) or typical family pets (dogs and cats). The writer also reminded us that the things we use every day and take for granted (e.g., clothing and computers) are often made available to us because of exploitive human labor – mostly people of color – elsewhere. These valid points are, however, overshadowed by the writer’s own rhetoric to denounce animal rights. Like the USA’s letter writer, she used the slippery slope fallacy (the right to vote; torturing carrots) and caricatures (torturing carrots; a chicken jumping into flour and fried) to not only mock but grossly writes off animal suffering. Even more harmful is the assumption of the work toward justice being a zero-sum game. The writer mentions the possibility of animal rights activists also caring about human issues only to hurriedly reject the possibility. But why cannot the animal rights movement collaborate with the fight for better wages, better housing, or better labor conditions? Why cannot someone be an advocate of anti-racism, anti-sexism, and animal rights simultaneously? Those questions fell outside the writer’s consciousness, though they are what intersectional activism that connects social justice and animal rights has been calling for (Freeman 2020; Kymlicka and Donaldson 2014). When one considers the fact that there have been remarkably few articles that brought up “animal rights” and “racism” in the same article to begin with, this type of “either/or” rhetoric forecloses the possibility of “both/and.”

5 Conclusion: patterns of erasure, missing conversations, and missed opportunities

What do we learn from the collective discourse about “speciesism,” “animal rights,” and “racism” in some of the largest newspapers in the United States? By way of conclusion, this last section reviews the main findings and discusses their implications. First and foremost, the idea of “speciesism” has been virtually non-existent in the mainstream U.S. newspapers in the last four decades. While speciesism has increasingly become a topic of interest in scholarly discourse across disciplines, it has not been taken up by the major news media. This erasure by non-representation makes it particularly difficult for the public to even begin to conceptualize the hierarchies and oppression of life so normalized in society. Even when articles mention “speciesism,” the majority of them did not bother to explain the concept. Within the articles that did engage the idea, only few discussed the connection between speciesism and racism, regardless of whether the authors affirmed or rejected the connection. This was also the case when “animal rights” was used as a proxy for “(anti-)speciesism” to look for more articles that potentially articulated the interlocking systems of oppression. The majority of articles ornamentally used “speciesism,” “animal rights,” and “racism.” Both exclusion and ornamentalization erase speciesism and foreclose conversations about its association to racism. If the media’s collective representations set agendas about what is important and how (McCombs and Shaw, 1972; Valenzuela and McCombs, 2019), one can argue that the overwhelming lack of representation also helps to set an agenda by erasing the issue from public consciousness.

Second, when connections were made between speciesism and racism or between animal rights and (anti-)racism, the connections were often left unexplained. This incomplete articulation also contributes to erasure. In a culture where a public discussion of speciesism is missing and racism and sexism continue to be wicked problems, leaving the connection unexplained has a consequence. The link remains unregistered for the public or worse the void will be filled with the dominant voice of zero-sum game. In fact, and thirdly, the articles that outwardly rejected the connection served to fill this void by tapping into the taken-for-granted normative practices and thinking, using mockeries, and framing anti-speciesism as racism. Various discursive closure strategies such as naturalization, legitimization, and neutralization were used to defend speciesism and to articulate incongruence between racism and sexism on the one side and speciesism and animal rights on the other. This dualism is not just a declaration of difference ontologically naturalizes the difference and assigns power to the difference. Dualism, according to ecofeminist Plumwood (1993, 48), is a relation of separation and domination inscribed and naturalised in culture and characterised by radical exclusion, distancing and opposition between orders constructed as systematically higher and lower, as inferior and superior, as ruler and ruled, which treats the division as part of the nature of beings construed not merely as different but as belonging to radically different orders or kinds, and hence as not open to change.

This hierarchical dualism characterizes the articulation that denied the systemic connection between racism and speciesism. Plumwood (2002) argued that dualism is a central feature of colonization as it naturalizes the master subject’s privilege and domination of the inferiorized. It is with this logic that the subjugation of people of color was justified, and it is with this logic that exploitation of women and sexual others was explained away. Speciesism does the same by using the difference between humans and nonhuman animals as given and as the basis for domination.

The mainstream media has an unparalleled power to influence the public agenda. That power comes with the responsibility to usher in the conversations that elevate the wellbeing of the public. In an entangled world, such conversations must include the interlocking systems of oppression, within humans and between humans and the more-than-human world. The incredible lack of articulation connecting speciesism and racism must be rectified. But it is not just the quantity; this study showed that mere appearance of the concepts does not make them salient. Here, a few directions should be considered.

First, animal rights movements, just as the larger environmental movements are undergoing, must tackle racism and privilege within the movements that are overwhelmingly White. The dominant news media can and should play a role in addressing this challenge just as the non-profit news organization, Sentient, did. One of the contributors to Sentient, Eubanks (2021), a Black vegan animal rights advocate, gave an example of diet to illustrate White centeredness of the animal rights movement. He observed that veganism campaigns mainly cater to Whites and ignores the limitations, needs and perspectives of people of color. He elucidated the cost of racism in the movement this way:

Non-human animals are systematically killed by the trillions every year, making them statistically the largest group of oppressed beings on the planet. But as humans who are advocating for them, we have to be aware of how human-based social issues impact the animal protection movement. Ignoring social justice allows inequity to thrive, leading to turmoil and internal conflict within the movement. Ultimately, ignoring social justice deters the progress we can make for the animals.

Similarly, Rojas-Soto (2020) who served as the managing director of an animal advocacy nonprofit, Encompass, pointed out that racism permeates the animal protection movement in the forms of campaign rhetoric, marketing images, recommended diets, and mostly white leadership. Within the movement, she has witnessed many White animal advocates deny racism and its impacts and preferred to set aside antiracism as a separate issue. As a “Black Latinx woman” farm animal advocate, she sees danger in this denial and single-issue tendency:

… speciesism is made stronger by racism, which is made stronger by sexism, which is made stronger by heterosexism, ableism, and on and on. But instead of being ordered in sequence, each node of oppression is connected to every other node, creating a very strong and resilient system.

Those words give a useful context for understanding the dismissiveness of anti-speciesism expressed by some articles reviewed in this study and its limits. Rather than continuing the discourse that prioritizes either anti-speciesism or racism or pits those against each other, we need a public discourse about how those systems reinforce each other. The dominant news media has a critical role to play in creating such a space.

Second and relatedly, language is of paramount import. As we learned, subjects can be present and annihilated simultaneously. Backgrounding through partial presence, distortion through condemnation and trivialization, and foreclosing conversations by such discursive strategies as naturalization, neutralization, and legitimization and overall zero-sum framing all contribute to divisiveness. Instead, what conversations may be born if there are articles in major newspapers that give salience to the interlocking systems of oppression and to the possibilities of multispecies justice (Celermajer et al., 2021; Kirksey and Chao, 2022)? What if there are stories that recognize and respect different and often conflicting values and standpoints that historicize instead of naturalize difference? According to psychologist Melanie Joy (2023), all expressions of injustice from interpersonal to societal (e.g., racism, patriarchy, poverty, war, animal exploitation, domestic abuse) are characterized by relational dysfunction where integrity and respect for dignity are lacking. What if there is more public discourse, including the news media, that focuses on relationality? And, what if the discourse exercises language that embodies integrity and respect for both humans and nonhuman animals? We know too well how divisive and demeaning language quickly leads to relational dysfunctions in the human world. In the Animals and Media website, Communication scholars Carrie Freeman and Debra Merskin stress the importance of applying the same sensibility to nonhuman animals and provide style guides for media professionals in covering and representing nonhuman animals in a fair and respectful way (Animas & Media - Giving Voices to the Voiceless, n.d.). As powerful agenda setters, newspapers do well to adopt those guides.

Finally, mainstream newspapers need far more diverse representations of people and sources who advocate for intersectional approaches to justice. The two articles that affirmatively discussed the connection between speciesism and racism in some lengths were both about Peter Singer, and they were both published in 1990. This is a sad discovery. In the last three decades, multidisciplinary scholarships grew, including intersectionality, indigenous epistemologies, ecofeminism, critical animal studies, critical media studies, multispecies justice, and integrative biology just to name a few. These scholarships are diverse in approaches and perspectives, but they all have something to say about racism and speciesism and interlocking systems of oppression. Newspapers have myriad opportunities to feature what those scholarships can offer to animate more productive and perhaps more relational conversations not only about how injustices are interrelated but more importantly how liberation and empowerment may be ushered in the entangled world in which we live.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

EK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the reviewers for their constructive feedback and UNC Greensboro’s library for open access publishing support.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Almiron, N., Cole, M., and Freeman, C. P. (2018). Critical animal and media studies: expanding the understanding of oppression in communication research. Eur. J. Commun. 33, 367–380. doi: 10.1177/0267323118763937

Amorim-Maia, A. T., Anguelovski, I., Chu, E., and Connolly, J. (2022). Intersectional climate justice: a conceptual pathway for bridging adaptation planning, transformative action, and social equity. Urban Clim. 41:101053. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2021.101053

Animals & Media–Giving Voice to the Voiceless. (n.d.) Available at: https://animalsandmedia.org/ (Accessed September 17, 2024).

Broad Garrett, M. (2013). “Vegans for Vick: Dogfighting, Intersectional Politics, and the Limits of Mainstream Discourse.” Int. J. Commun. 7, 780–800. doi: 10.51644/9781771122115-013

Caviola, L., Everett, J. A. C., and Faber, N. S. (2019). The moral standing of animals: towards a psychology of speciesism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 116, 1011–1029. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000182

Celermajer, D., Schlosberg, D., Rickards, L., Stewart-Harawira, M., Thaler, M., Tschakert, P., et al. (2021). Multispecies justice: theories, challenges, and a research agenda for environmental politics. Environ. Politics 30, 119–140. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2020.1827608

Coleman, R. R., and Yochim, E. C. (2008). The symbolic annihilation of race: a review of the ‘blackness’ literature. Afr. Am. Res. Perspect. 12, 1–10.

Costello, K., and Hodson, G. (2010). Exploring the roots of dehumanization: the role of animal—human similarity in promoting immigrant humanization. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 13, 3–22. doi: 10.1177/1368430209347725

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist policies. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1, 139–167.

Davis, A. (2012). “Grace lee Boggs in conversation with Angela Davis.” Making Contact: Radio Stories and Voices to Take Action. Available at: https://www.radioproject.org/2012/02/grace-lee-boggs-berkeley/

Deetz, S. A. (1992). Democracy in an age of corporate colonization. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Dhont, K., Hodson, G., and Leite, A. C. (2016). Common ideological roots of speciesism and generalized ethnic prejudice: the social dominance human–animal relations model (SD-HARM). Eur. J. Personal. 30, 507–522. doi: 10.1002/per.2069

Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Leite, A. C., and Salmen, A. (2019). “The psychology of speciesism” in Why we love and exploit animals. eds. K. Dhont and G. Hodson. 1st ed (Routledge), 29–49.

Eubanks, C. (2021). “As a black man, I felt uncomfortable becoming an animal activist.” Sentient Media. March 1, 2021. Available at: https://sentientmedia.org/as-a-black-man-i-felt-uncomfortable-becoming-an-animal-activist/

Fitzgerald, A., Halliday, J., and Heath, D. (2021). Environmental DNA as novel technology: lessons in agenda setting and framing in news media. Animals 11:2874. doi: 10.3390/ani11102874

Freeman, C. P. (2020). The human animal earthling identity: Shared values unifying human rights, animal rights, and environmental movements. Athens, UNITED STATES: University of Georgia Press Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uncg/detail.action?docID=6421879.

Gerbner, G., and Gross, L. (1976). Living with television: the violence profile. J. Commun. 26, 172–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1976.tb01397.x

Gutsche, R. E., Cong, X., Pan, F., Sun, Y., and DeLoach, L. T. (2022). #DiminishingDiscrimination: the symbolic annihilation of race and racism in news hashtags of ‘calling 911 on black people.’. Journalism 23, 259–277. doi: 10.1177/1464884920919279

Hall, S. (1985). Signification, representation, ideology: Althusser and the post-structuralist debates. Critic. Stud. Mass Commun. 2, 91–114. doi: 10.1080/15295038509360070

Hall, S. (1996). “Introduction: why needs identity?” in Questions of cultural identity. eds. S. Hall and P. DuGay (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.), 1–17.

Hall, S. (1997). “The work of representation” in Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. ed. S. Hall (London: SAGE Publications, Inc.), 15–64.

Harper, A. B. (2011). “Connections: speciesism, racism, and whiteness as the norm” in Sister species: women, animals and social justice. ed. L. Kemmerer (Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press), 72–78.

Jones, R. C. (2015). “Animal Rights Is a Social Justice Issue” Contemporary Justice Review 18, 467–82. doi: 10.1080/10282580.2015.1093689

Kim, Y., Kim, Y., and Zhou, S. (2017). Theoretical and methodological trends of agenda-setting theory: a thematic analysis of the last four decades of research. Agenda Setting J. 1, 5–22. doi: 10.1075/asj.1.1.03kim

Kinefuchi, E. (2015). Nuclear power for good: articulations in Japan’s nuclear power hegemony. Commun. Cult. Critique 8, 448–465. doi: 10.1111/cccr.12092

Kirksey, E., and Chao, S. (2022). “Who benefits from multispecies justice?” in The promise of multispecies justice. eds. S. Chao, K. Bolender, and E. Kirksey (Duke University Press), 1–21.

Klein, H., and Shiffman, K. S. (2009). Underrepresentation and symbolic annihilation of socially disenfranchised groups (‘out groups’) in animated cartoons. Howard J. Commun. 20, 55–72. doi: 10.1080/10646170802665208

Kymlicka, W., and Donaldson, S. (2014). Animal rights, multiculturalism, and the left. J. Soc. Philos. 45, 116–135. doi: 10.1111/josp.12047

Lorde, A. (2012). Sister outsider: essays and speeches. New York, United States: Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale.

Majid, A. (2023). “Top 25 US newspaper circulations: largest print titles fall 14% in year to march 2023.” Press Gazette, June 26, 2023. Available at: https://pressgazette.co.uk/media-audience-and-business-data/media_metrics/top-25-us-newspaper-circulations-down-march-2023/

McCombs, M. E., and Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 36, 176–187. doi: 10.1086/267990

Merskin, D. (1998). Sending up signals: a survey of native American1 media use and representation in the mass media. Howard J. Commun. 9, 333–345. doi: 10.1080/106461798246943

Nibert, D. A. (2015). “Origins of oppression, Speciesist ideology, and the mass media” in Critical animal and media studies: Communication for nonhuman animal advocacy. eds. N. Almiron, M. Cole, and C. P. Freeman (Routledge).

Regan, T. (2004). The case for animal rights. The case for animal rights: University of California Press.

Rojas-Soto, M. (2020). “Oppression without hierarchy: racial justice and animal advocacy.” Sentient Media. October 15, 2020. Available at: https://sentientmedia.org/oppression-without-hierarchy-racial-justice-and-animal-advocacy/

Ryder, R. D. (2011). Speciesism, Painism and happiness: A morality for the twenty-first century. Luton, Bedfordshire, UK: Andrews UK Ltd.

Singer, P. (2015). Animal liberation: The definitive classic of the animal movement. The fortieth. Anniversary Edn. New York: Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

Slack, J. D. (1996). “The theory and method of articulation in cultural studies” in Stuart Hall: Critical dialogues in cultural studies. eds. D. Morley and K.-H. Chen (London: Routledge), 112–127.

Stibbe, A. (2021). Ecolinguistics: Language, ecology and the stories we live by. Second Edn. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.