- School of Humanities, Communication University of China, Beijing, China

Faced with the decline of dialects, the rise of new media platforms has made young dialect enthusiasts an emerging force in maintaining language diversity. By sharing dialect content online, they enhance the dialect visibility and form a new way of communication, thereby highlighting the link between dialect inheritance and youth identity. To explore multilingual and multicultural dynamics in China amidst globalization, this study adopts the method of online ethnography, conducting interviews and participatory observation within dialect communities on platforms of WeChat and Bilibili. By analyzing the formation, register, and significance of the community, the study reveals that enthusiasts not only directly use and experience dialects online, but also create a special variety of “Internet dialect”. With the leading of pioneers and interrelationship among members, they break the identity barriers and negotiate to construct dialect knowledge, actively promoting the dialect culture within the “virtual acquaintances society”. The discussion underscores the necessity of youth engagement and new media in dialect living inheritance, aligning with but extending current understanding of dialect protection strategies, and points to the potential for the construction of a community with a shared future in cyberspace.

1 Introduction

Nowadays, with the popularization of urbanization and globalization, the endangerment of local languages has become an increasingly significant phenomenon worldwide (Bromham et al., 2022). In China, this trend is exemplified by the weakening of regional dialects with promotion of Putonghua (Mandarin Chinese) (Shi, 2015), which has attracted wide attention from the scholars and the public. However, as underscored by UNESCO in the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO, 2003), language constitutes a vital element of intangible cultural heritage. As linguistic variety, dialects are indispensable for linking geographical regions, conveying traditional values, and safeguarding cultural diversity. In the context of the online environment, the preservation of dialects is equally crucial, as the Internet may both be an opportunity and a threat to linguistic diversity. On one hand, the new media platforms offer dialects a channel for living inheritance and have fostered the extensive use of online dialect writing (Li W., 2022; Liu, 2011), representing a form of dialect liberation. On the other hand, while the Internet facilitates the dissemination of mainstream languages, it can simultaneously marginalize speakers of local dialects in developing countries, particularly those that are at the risk of disappearing (Pimienta et al., 2009), thereby exerting significant pressure on the spaces for dialect use and transmission.

Under this context in China, in addition to the dialectology academic community and the official language resource protection team, many young dialect folk enthusiasts have emerged in recent years, using new media platforms to release various dialect videos and establish interest “network dialect community,” which forms a language protection force that cannot be underestimated. The “network dialect community” mentioned here specifically refers to the temporary social group composed of fans who interpret the geography and culture in the virtual cyberspace for exchanging and sharing dialect knowledge and materials in China. These young dialect enthusiasts represent a cultural transformation, bringing the knowledge of the dialect discipline from the “elite culture” to the “folk culture,” and then transforming it into “mass culture” through the power of online communities. They have formed a “dialect circle” on the Internet, with their influence becoming more and more extensive, forming a new way of social communication and identity among young people.

The reason such community is called “young” is primarily because of its “youth identity.” In the context of this study, this refers to as individuals aged 18 to 34. This age range begins at the typical university entry age and extends to the threshold of “middle age” in China, which is around 35. It also aligns with the “post-90s” and “post-00s” generations (as of 2024), who are characterized by their university education and digital-native status. Based on interviews and observations, the author found that the majority of dialect enthusiasts community members fall within this age bracket, with a notable concentration even between 20 and 30 years old. This trend has witnessed a growing number of young people rediscover the value of dialect in regional and traditional culture, and even adopt and spread it as a conscious hobby and pursuit.

This study aims to deeply explore the profound significance of these young dialect enthusiasts communities in linguistics, communication and sociology through an interdisciplinary perspective. In addition, this study aims to explore the development route of online multicultural exchange and sharing platform, and provide new ideas and practice models for promoting the integration and communication of multiple cultures. This not only provides a new way to preserve and promote the language and cultural diversity, but also contributes to the construction of a more harmonious cyberspace.

2 Literature review

Through reviewing the literature, it can be found that scholars have delved into the multicultural and multilingual study about the relevant phenomena. From the multicultural perspective, the research on the youth sub-cultural community includes various “circles” such as fan circles (Wang, 2017), a Hanfu circle (Yang et al., 2022), Animation circle (Chen and Zhou, 2021), Sports subculture tribe (Li C., 2022) and so on, with relatively fewer studies on dialect videos on social media (Zhou, 2018, 2020). From the multilingual perspective, the study on dialect protection can be seen from the angle of dialect ecological protection, such as the dialect file (Yao and Zhuang, 2016; Yao et al., 2019) and language planning (Shi, 2015; Lei, 2012); and from the angle of dialect communication, like new media communication (Li W., 2022) and cultural products (Xiao and Wang, 2020). In addition, in sociolinguistics, community construction and community identity are important research topics (Dong, 2023), but studies focusing on community construction and identification on new media platforms from the perspective of language ideology are relatively few (Heuman, 2020), especially the language management and language practice of the online language community (Song and Feng, 2023). Therefore, the current research situation still has the following limitations. Firstly, the focus of youth subculture has been mainly on rebellious and resistant subculture against the mainstream culture, while the relatively “orthodox” hobby of dialect receives less concern. Secondly, on language protection, more attention has been paid to the top-down official behavior, while the subjectivity of the mass, especially the youth groups who construct and spread dialect culture has not been revealed enough. Thirdly, for circle language, more attention has been paid to the study of it through the social language variation, while less attention has been paid to the network dialect variation generated by the combination of social and regional variations in cyberspace. Based on this, this study tries to raise and answer the following questions: First, what are the characteristics of the formation and operation of the youth dialect enthusiasts community? Second, what kind of register does the youth dialect enthusiasts community create in the interaction? Third, what role does the youth dialect enthusiasts community play in the protection and dissemination of dialect culture?

3 Methodology

With the rapid development of Internet culture, multimedial forms of data and data collection are becoming more and more common. Raised by Kozinets initially in marketing research, online ethnograhy or netnography is currently an important method for investigating sociological and other disciplines such as communications. Evolving from ethnographic research, it is a qualitative research method “specifically designed to study cultures and communities online” (Bowler, 2010), where fieldwork transforms to the online field. It has the strength of cost-effectiveness, sample accessibility and unobtrusiveness, while keeping a naturalistic context (Kozinets, 2010; Murthy, 2013; Scaramuzzino, 2012). Therefore, online ethnography is employed in this study to explore the network dialect community, encompassing Bilibili, a leading video platform among China’s youth, and WeChat, the instant messaging service with the largest user base in China. Bilibili’s video-sharing focus and public commentary features make it ideal for showcasing dialect videos to a wide audience, while WeChat’s private group communications facilitate intimate social interactions and daily community discussions. This approach highlights the dialect community’s engagement with Bilibili for content dissemination and WeChat for ongoing social interaction.

According to Kozinets (2002, 2010), the method includes six steps, with small adjustments in application: Definition of the research field; Community identification and selection; Community observation and data collection; Data analysis; Research ethics. As mentioned above, we aim to investigate the dialect enthusiasts online community and take it as a mirror of multicultural and multilingual study. Then, to better understand the community, participatory observation and interviews are applied. Prior to doing the research, the author, herself a dialect enthusiast, had immersed herself in several dialect WeChat groups for at least 1.5 years, accumulating fragmented observations and perceptual reflections on the community. She occasionally joined group chats and commented on the Bilibili videos created by the group leaders. The prior engagement facilitated the study by providing insights and access to group chat data for analysis. In this study, the participatory observation was instrumental in designing the interview outline and enriching the qualitative data. It served to complement the interview method, shed light on the respondents’ behaviors, and offered a nuanced understanding of the community dynamics, particularly in the context of the section 4.2.3.

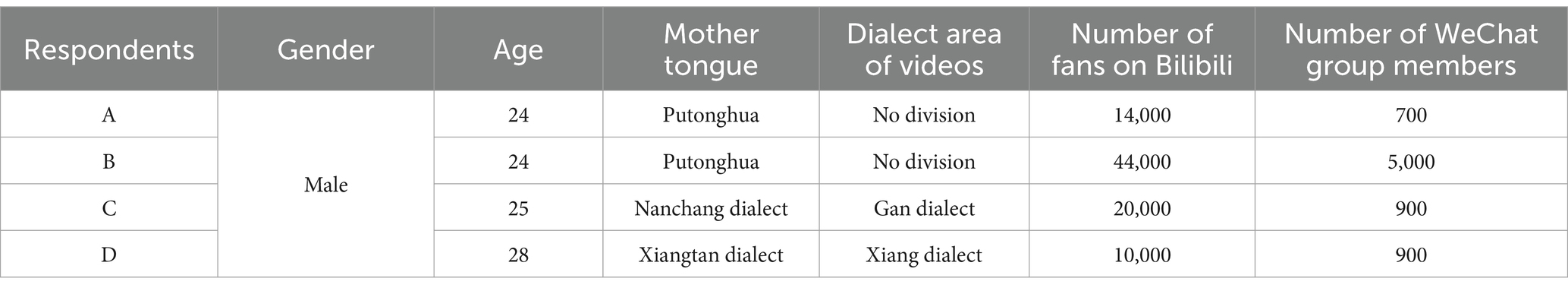

Besides, in-depth interviews were conducted with four representative dialect video creators, who are also WeChat group owners, to gain insights into community formation and management (see Table 1 for interviewee details). Respondents were selected based on opportunities that arose during the research rather than rigid criteria, a common qualitative approach when extensive population access is limited. The selection prioritized their leadership within the dialect community and their willingness to cooperate. All respondents are college-educated, non-linguistics enthusiasts with significant experience in dialect video production, well-versed and influential in shaping community rules, ensuring the study’s typicality and representativeness. Three were acquaintances of the author, who introduced a fourth upon understanding the study’s aims. Despite the small sample size, a micro survey was deemed more revealing for this preliminary research. Data analysis primarily relies on interview content, as it offers direct first-hand experience from community pioneers. Ethical considerations include obtaining consent, ensuring privacy, and guarantee on the anonymity and confidentiality of the community members.

Notably, all four respondents are male, which may accurately reflect the gender dynamics within the dialect community. Typically, males form the majority and exert a more significant influence, thus the study’s sample aligns with this demographic reality, mirroring findings in sociolinguistics. As was revealed by Trudgill (1972), speaking dialect could bring “covert prestige” on males, while females prefer the “overt prestige” associated with standard language. Besides, the dialect interest inherently connects to geographical, historical and political topics, where males are typically more engaged and knowledgeable. Therefore, in the context of online dialect communities, what was once “covert prestige” for males becomes “overt prestige.” Regarding their age, all respondents fall within the 24–28 range, which corresponds to the “young identity” mentioned earlier. They are either college students or recent graduates newly employed in the workforce, possessing the vitality and flexibility typical of emerging adults. This life stage affords them the time and autonomy to pursue and cultivate their passion for dialects, a factor that is crucial for understanding their active engagement within the dialect community.

Based on the concerns outlined above, the author conducted the interviews with the four respondents, respectively, via Tencent Meeting in November 2022. Each interview was recorded for subsequent analysis. The interviews were semi-structured, lasting 1–2 h per person, and mainly focused on three topics: 1. The origin of their dialect interest and the formation of dialect belief; 2. The experiences as the Bilibili video creators and WeChat group owners; 3. The understanding of their personal roles and contribution in the dialect community.

4 Results

Based on the qualitative analysis of the interview data, the findings can be divided into three themes: (1) the formation of community, including the learning of individual dialect knowledge, the transformation of dialect interest and mission, Bilibili video creation and WeChat group formation; (2) the register of community, including the topics of community, community participants, Internet dialect variety of community; (3) the significance and value of community, including dialect knowledge barriers and knowledge negotiation, silent external environment and active internal dialect circle, dialect discourse dispute and common identity construction.

4.1 The formation of the community

The formation of dialect community involves the following processes: the interest of a few individuals in dialect first triggers them to learn dialect knowledge, and gradually transforms into motivation or even mission with the deepening of interest. Then they begin to use the new media platform to spread dialect, thus generating cohesion and truly forming a community.

4.1.1 Learning of individual dialect knowledge

In any sub-cultural community, an understanding of the field is a prerequisite for entering it and becoming a pioneer. It also applies to dialect community, in which dialect knowledge seems to play a threshold or gate-keeping (Lewin, 1943) role, setting an informal standard to filter members and establish an internal hierarchy. After all, dialect is not only the objective form of language existence and the public resources of the mass, but also a professional “knowledge.” Having the knowledge is equivalent to getting the “ticket” into the community, so that one can get the affirmed group identity and carry out communication. Therefore, even the folk enthusiasts will often enrich and define themselves with the help of the academic knowledge system.

A: When I was curious about dialect in junior high school, I began to search for some dialect knowledge on Baidu Tieba, and also added some QQ groups and forums. After going to college, I learned about phonology through the dialect circle. In my sophomore year, I took the traditional phonology online course of Shanghai International Studies University. After studying roughly, I understood some basic concepts of phonology. Now I can speak six dialects.

B: I liked to watch TVB movies (in Hong Kong) and TV dramas in junior high school, so I became interested in Cantonese. By imitation, I could gradually speak it in high school. Then I began to learn other dialects and came into contact with formal dialectology. I could use International Phonetic Alphabet, though not very professional. I learn dialect knowledge mainly by pronunciation, some of which are seen in the dialect annals, and some through learning specific dialects. Now I can speak about 20 to 30 dialects (to the level that can be shot).

C: I started with my interest in Chinese characters in junior high school, from glyph and pronunciation to dialect. At that time, I often read Xinhua Dictionary and Nanchang Dialect, and found that Nanchang dialect could be written down. After getting a mobile phone, I always surfed the Baidu Tieba about discussions on dialect; I even found the entry of Gan dialect on Wikipedia, feeling that there is much to ponder about it. As for learning, I have taken the Chinese character and phonology online class of Wuhan University, and learned the International Phonetic Alphabet. These are basically enough for me. Now I can speak three accents in Nanchang dialect.

D: I’m fond of dialect because of my father’s influence, who always went business trips to and imitated accents from many places. During the university, I added the QQ group of Hunan Dialect, in which I was initially a green hand, but later became particularly interested due to the Hunan Dialect Dictation Conference. My dialect knowledge mainly includes International Phonetic Alphabet and phonology, which on the whole is learned by the group. I think it is not very difficult. Now I can speak Xiangtan dialect well, Xiangxiang dialect, Yiyang dialect and Changsha dialect.

From the above discourse, it can be seen that when it comes to the methods of learning dialect knowledge, respondents mentioned ways of actively searching Internet resources (A, B, C, D), reading books and dictionaries (B, C), and learning dialectology (B) and phonology (A, C, D) to deepen their understanding of the related knowledge. In addition, it is found that they generally have strong dialect ability, ranging from several accents of their own dialects to 10 or 20 dialects (which may not be as natural as L1 speaker, but can reach the level of free speech in video shooting), showing the positive interaction between their dialect knowledge and dialect ability. It is noted that, although dialect knowledge is a learning, it is not exclusive to anyone. Viewing from the learning channels, the respondents mainly learn through network interaction and media experiences, which indicates that the convenience of technology is breaking down the knowledge barriers and promoting the popularization of dialect knowledge. For example, three respondents said that college was a critical period for their interest blooming, which is mainly due to the opportunity of accessing mobile phones and computers that they could benefit from online learning. In the digital age, information literacy has become the cornerstone of key capabilities and pioneer influence in a community. According to Bourdieu’s theory of Cultural Capital (Goldthorpe, 2007), cultural capital comes not only from education but also the acquisition of various information in the environment, which is the prerequisite for aesthetic activities, and also brings taste division. Therefore, it can be considered that, as amateur members of the dialect community, they acquire dialect knowledge through public resources, bring the accumulation of early cultural capital through self-investment, and also enhance their recognition of their own legitimacy.

4.1.2 Dialect interest and mission transformation

In the process of personal growth of the core members of the dialect community, the deepening of their dialect interest has gradually evolved into the motivation and sense of mission of action.

A: At first, I just regarded it purely as an interest, without thinking too much. Later, I sent several videos to introduce our Xinjiang dialect through Bilibili, and achieved some results, so I have been doing it. After the rise of TikTok, I saw that there were a lot of incorrect remarks about dialects, so I wanted to do dialect science popularization to eliminate misunderstandings, thus I set a high goal and wanted to work hard for the revival and inheritance of Chinese culture. Then again practical, it is not for the grand goal, and it is impossible to achieve that goal.

B: I mainly take it as an interest. It is too big to speak of it as a mission. I position myself as a learner, with the direct idea of learning various dialects. In my initial stage of making video, I attracted some like-minded friends and gradually formed a circle. Our folk language protection group is a place to send and receive corpus. Now the dialect is changing rapidly, so we need to record it quickly. If it dies out one day, the corpus can still play a role. It is not only to supplement the official language protection, but also good for enthusiasts.

C: I may be opposite to others, and I want to take it as a mission. Without characters, Chinese civilization cannot inherit and unite so many people. Moreover, the existence of written characters definitely has a positive impact on the spread and dynamism of dialects, such as Cantonese. When in high school, I noticed some Nanchang dialect expressions and Emojis online, which were written with homophones in Putonghua. I viewed them very strange. Why not use the original forms of characters? So I want to tell others whenever possible the original form of characters in dialect.

D: I took it as my interest first, but later a mission when I found that our Xiang dialect community was too backward compared with numerous other dialect groups, and I was very angry. Why could not we have a strong organization? In addition, WeChat has been popular for some years, so in 2019, I built a Xiang dialect WeChat group out of a sense of responsibility. I told my members there is no distinction between dialects in status, and they would also spread the idea out, which is conducive to the development of the whole Xiang dialect community.

The interview found that the four respondents all had a sense of mission to protect and spread dialects, though for different purposes: eliminating misunderstanding of dialects (A), recording the dialect corpus (B), maintaining the dialect orthography (C), and promoting the development of the mother language community (D). What they have in common is that they transcend the level of individual learning and appreciation of dialects, and desire to influence more people around them, reflecting the practicality of their beliefs. Although they may feel too heavy to regard it as “mission,” rather as “mere interest” (B), or think they are “not for the grand goal” (A), objective speaking, their behaviors such as creating and spreading dialect videos, and building WeChat dialect groups are the practical contribution in the dialect culture inheritance. Some respondents are even unhappy at seeing their dialect being abused (C), or angry at finding their dialect community backward (D). Such emotional expressions undoubtedly reflect love and responsibility for dialect culture.

According to Collins (2009) theory of the Interactive Ritual Chains, emotion is the key premise for the interactive ceremony. The emotion generated through the ceremony communication can regenerate a common focus of attention, making the emotional energy among individuals become the energy of larger group, forming the inherent emotional symbols of and the norms within the group. As a cultural symbol, dialect carries the memory of regional culture and local society. It can stimulate the long-term emotional energy in the community interaction in a concentrated form, providing the inexhaustible power for the subject to construct and participate in the community. Although individuals’ feelings toward dialect may be diverse, with passion or ration, the respondents transform their individual motive into collective identity by striving to encourage the community members to learn dialect, speak dialect, properly use dialect, and reasonably view dialect, which realizes the connection of relationships and the flow of emotion. This not only provides a positive experience for them to keep creating dialect videos, but also provides an innovative impetus to continue running the community.

4.1.3 Bilibili video creation and WeChat group formation

As a leading video and cultural community in China, Bilibili is an important website for young people’s entertainment and learning, as well as a gathering place for niche enthusiasts. The dialect community on WeChat largely overlaps with the communication network formed by the video creators of the Bilibili, which means that the network leaders and their videos play a key role in member cohesion and community transformation.

A: In 2019, I started to do Bilibili to introduced Xinjiang dialect, and then gradually expanded. As for content, there are academic type, transformative type, chatting, etc. For technology, I explored it in the early stage myself, but now with the help of a friend and more learning, I can complete functions of adding subtitles and editing. The “B Cut” software can automatically add subtitles to Putonghua, but it is very troublesome to add subtitles to dialect. Also I want to do the dialect atlas introduction, but the production is difficult and so has not been realized.

B: In 2020, I made the first original video, in which I imitated Taiyuan dialect. Someone left a message below saying that he wanted to add my WeChat. Later, in order to facilitate the communication with the speakers and collected the corpus, I formed a folk language protection group. My video making skills are very simple, mainly PPT plus screen recording. My early most viewed videos were almost all voice files of comparison between dialects in a region. I think the reason may be that it is difficult to find similar works on the Internet, so it is easy to attract some people.

C: In 2018, I started to participate in the activity of “Bilibili Good Local Accent,” and found that it could get traffic. In the early days, my content was mainly text reading, including Nanchang dialect recitation, ballads, tongue twister, etc., and my technology was just screen recording. Later, I transformed content from Jiangxi Dialect Conference; then I did dialect popularization but had low traffic; now, entertaining dubbing is my focus which I found has a bit of traffic, and I also do some interesting popular science type. On technology, I am gradually exploring it and usually do it myself. Recently, I have cooperated on history and culture videos.

D: In 2020, I posted the first video on Bilibili, but some people said that they could not understand the standard Xiangtan dialect. So I changed my mind and wanted to start with popular science, but also wanted to be interesting. Now I mainly do the dialect related popularization, hoping to have a wider scope. I do not want people to think dialects are just funny, so I tried to use soothing tone and high-definition picture quality to avoid funny effect. Technically I would seek help at first, later with more practice I can use editing and animation software myself.

From the interview and observation, it can be found that as for type of videos, there are specialized dialect voice files and dialect comparison (B), academic content (A), popular science related to dialect (C, D) and entertaining dubbing (C). From academic to entertainment oriented, these different content and styles not only reveal the identity of video creators between professional expertise and non-professional enthusiasts, namely “amateur experts,” but also reflect the phenomenon of content competition in the context of internet “marketization.” Generally speaking, the young “consumers” (audiences) may prefer a relaxing and humorous style, but the videos produced by respondent B, which has the highest number of fans, tend to be more serious and slightly monotonous. This seemingly cognitive conflict shows that Bilibili is not only a pan entertainment and social platform, but also a powerful channel of spreading knowledge, presenting the complementarity and integration of subcultures and mainstream cultural styles. With the increase of video views and the audience interaction, dialect enthusiasts gradually gather in the comment area of video creators’ account, the latter of which then provides a stronger social interaction space for the former by establishing WeChat groups and other ways.

Besides the content and style of video creation, technical capabilities also constitute important cultural capital and social capital of the creators on Bilibili. In terms of production, most of the four respondents completed the videos independently, and despite their skills varying, their videos are generally visually appealing. In the new media era, the technology affordance (Bloomfield et al., 2010) enpowers mass creators, and technology capital has become an indispensable quality for content creators. For example, the free editing tool “B Cut” provided by Bilibili simplifies the video editing process, and the reward mechanism of it also encourages users to create. However, technical barriers still pose challenges, such as some respondents mentioned “wanting to do the dialect atlas introduction, but the production is difficult” (A). It can be seen that the realization of high-quality technology not only requires a lot of time and even economic costs, but also encourages creators to continuously improve their skills and find the balance between expressing personal creativity and meeting the needs of the audience.

4.2 The register of the community

According to Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), language occurs in and is explained by context, and differences in context can lead to language variation. “Register” is a powerful conceptual tool to uncover the general principles governing variation in dynamic social change, and therefore well applicable to the study of speech community. In Halliday’s theoretical framework, the three variables of “field,” “tenor” and “mode” are the components realizing the features of the context, determining the three components of meaning system--“ideational,” “interpersonal” and “textual” meanings. In this section, we attempt to analyze the context of dialect community from Halliday’s register theory in the three contextual variables: field, tenor and mode (Halliday, 1978).

4.2.1 Field: what the community talks about

The “field” of a community mainly refers to the content of the topic. In the context of the dialect community, the topics between the members mainly revolve around the dialect or are discussed in dialect, forming a real dialect field and speech community. Through observation and interview, the researcher has found that the topics can be roughly divided into three categories: dialect knowledge, regional culture, and traditional culture.

A: When talking about the popular science of dialects, it is quite objective. But in addition to the dialect itself, some political, historical and other topics will also be involved. My own group positioning is based on my own (interest).

B: The group I built is a folk language protection group, which is essentially a place for sending and receiving corpus. (The group announcement states that messages unrelated to the language resources should not exceed 50.)

C: We mainly talk about dialect words. On dialect topics, I always want to tell some dialect etymological characters. Sometimes we talk randomly also, such as asking and recommending delicious restaurants, just like the fellow townsman group. The group announcement states that other than dialects, there could be local folk ballads and so on, and it is increasingly turning into a hobby group.

D: It is just casual chatting, not necessarily related to dialect, as long as it’s not against the rules. Unlike folk language protection group, my group has all kinds of people and cannot be too strict, so it is relatively relaxing. I try to let the group members accept the orthodox pronunciations, but it needs a process. At the same time, I told my members there is no distinction between dialects in status, and they would also spread the idea out. There are also members who learn knowledge they want through the papers and reports sent by others in the group.

First, taking dialect knowledge as an example, it includes professional knowledge of dialect itself and concept and understanding of dialects. In terms of dialect knowledge, which mainly include the theoretical basis of dialectology and phonology, the group owners and members are often eager to share papers, reports and other resources (D); meanwhile, the “obscure knowledge” of orthodox pronunciation and etymological characters of dialect are important contents (C, D) for group owners to spread. As for the concept and understanding of dialect, the group owners will strive to break the stereotype of dialect and advocate rational dialect attitude. For example, “I told my members there is no distinction between dialects in status, and they would also spread the idea out” (D). Besides, due to the natural connection between regional culture and traditional culture with dialects, group sometimes discuss regional cultural topics such as folk ballads, opera singing pieces, festival customs; as well as traditional cultural knowledge such as poetry creation, rhyme and lyrics writing, and historical changes of administrative divisions also. It is worth noting that the development and innovation of traditional culture is of great concern to the community.

In addition to the above, the topic is also related to group positioning, such as whether it is a personal fan group (A, C, D) or a folk language protection group (B). If the former is centered around the region, it is easy to form a group of fellow townsmen, and the chat content is mainly based on the local dialect, while also discussing local culture and even life topics (C); if it is a large group that does not distinguish regions, then history, language, culture, etc. can be discussed in detail (A). At the same time, the topic may also be influenced by the personal style of the group owners (A, C), or by the identity of the group members. If the group members have a wide range of sources, the chat topic in the group is relatively loose (D). Relatively speaking, although the folk language protection group (B) has a clearer purpose of limiting the topic range with group announcements, it usually does not impose too much pressure. In general, the dialect community provides a free communication platform for the members, which not only promotes the sharing of the dialect knowledge, but also stimulates the members’ new understanding of the regional culture and the traditional culture.

4.2.2 Tenor: participants in the community

The “tenor” of a community refers to the identity of the participants and their relationship. In the dialect group, although the social identities of the members are diverse, their relationship are generally harmonious. What is worth noting is their differences in activity levels, forming the distinction of identity. In the process of community development, there are constantly “green hands” coming in and gradually growing under the influence of the “big guys” in the circle.

A: Actually, there are two kinds of people in our group, one is recruited as speakers, who may not be very interested in dialect themselves, and another is introduced as dialect enthusiasts. Usually in a group, only a few professional members drive the atmosphere, leaving most of the others to provide corpus. But there is no problem to consider we have the common identity, that is dialect lovers. As for the feedback of building the group, I hope that the group friends can support me.

B: It’s okay to think that the group members are dialect enthusiasts. Entering the group means being willing to provide corpus and observe the group announcement. Furthermore, I believe that liking dialects does not necessarily mean liking dialectology, nor using more dialects in life. They should be viewed separately. I hope to get feedback from the group, especially to let others comment on my dialect pronunciation, because as a learner, it is an important way to improve my oral level.

C: Some group members are not enthusiasts, just those who are interested, and the silent followers are the majority. This is the same in any hobby group. Whether it’s a group of 100 or 500 people, there are only a dozen or twenty people who often chat.

D: Sometimes I will send my own video clips to the group, and members will discuss them and reply.

In WeChat groups, although group members can generally be considered dialect enthusiasts (A, B), there are also differences in status (A, C). Based on the Kozinets (1999, 2010) classification of the online community members, the dialect group members can be divided into core administrators, active communicators, and most peripheral observers according to their behavior and connection in the community. The core administrator, usually composed of group owners (also video creators) themselves and their assistants, plays the role of topic guidance and order maintenance; the active communicators actively participate in the discussion and often introduce new topics, enjoying high familiarity with each other in the interaction; the peripheral observers, who occasionally speak and usually maintain distance, are in weak relationship in the circle, but they provide a broad environment and foundation for the community. It can be considered that the activity of members may be related to their enthusiasm and knowledge depth of dialect. For example, group owners generally has the deepest interest and a considerable level of dialect knowledge, and they are often the key opinion leaders of the community; some members have academic backgrounds, while others are dialect users or enthusiasts. They either have the ability, time, or enthusiasm to participate in or promote dialect group discussions.

Although the power status within the group is unequal to some extent, there is also interdependence between group owners and ordinary group members. In terms of the return, the group owners also hope to develop themselves on the basis of group members, such as they expect to get support and feedback from group members (A), comments on dialect pronunciation (B), or feedback on video content (D). In this case, the opinions and feedback of group members have become an important driving force for the improvement of group owners, so they are endowed with higher expectations and status. Therefore, the interrelationship among community members promotes group consolidation and intimacy.

4.2.3 Mode: language variety of the community

The “mode” of a community refers to the medium or channel through which language is used. As a burgeoning offshoot of Internet language, “Internet dialect” has the characteristics of economy, innovation and informality. In the community, the language mode of “Internet dialect” can be regarded as a hybrid that integrates modern Chinese dialect with elements from ancient Chinese, foreign languages, and a variety of symbolic code resources, reflecting the phenomenon of translanguaging (Li and Shen, 2021). Participatory observation has led to the following findings.

Firstly, this characteristic can be seen from the group name, for example, the group name of respondent A is “食母均馆”(“Si4 Mu3 Yun4 Guan3,” literally meaning “feeding mother rhyme pavilion”), which is in the ancient Chinese usage and can be explained as “a place to cultivate the root,” namely a community to protect the Chinese dialect and phonology; the group name of respondent C is “鸿也屋里” (“Hong2ye3 Wu1li3,” literally meaning “Hongye house”), adopting the integration of personal brand (C’s net name “Hongye”) and Nanchang dialect (“wuli” meaning “house”); C’s another related dialect group takes “Kɔm ŋiɛ kaʊ liu” as the name, which is the pronunciation of “Gan dialect communication” in International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), showing the mastering of IPA. Secondly, the dialect video on Bilibili can also show the translanguaging characteristic. For example, in the video of respondent C, there is a series of short teaching dramas “New Concept Nanchang Dialect” imitating “New Concept English.” With the interweaving of Nanchang accent English and Nanchang dialect, foreign language is skillfully integrated into local dialect teaching. Thirdly, in group chat, dialect words, Chinese pinyin and dialect pronunciation spelled in IPA appear quite often; there are also a combination of dialect and Putonghua, such as using dialect accent Putonghua to send voice messages, or using dialect homophonic characters to play jokes; besides typing, chatting in dialect voice messages is frequent in this community, and multi-modal elements such as dialect songs and dialect emojis are also welcomed by group members.

It can be argued that the Internet dialect variety in dialect community show the diversity of language patterns, and can be used in various media such as text, voice and video. At the same time, such variety reflects the adaptability to the specific social context, as it integrates dialect into other codes in the network social context, forming new characteristics. Dialect enthusiasts often interact with each other in specific ways of expression, and the evolution of their Internet dialect variety has led to more language innovation and integration, which is consistent with Halliday’s dynamics view of language. Language speakers are constantly creating new language patterns to express meaning, and Internet dialect variety is a good example of this innovation. Moreover, the Internet dialect variety is diverse and adaptive, often characterized by a sense of humor. This light-heartedness is a distinctive feature that enhances its engagement and accessibility, contributing to its widespread adoption in the online community. The sharing and communication of the network dialect community not only enrich the field of dialect culture, but also provide a new perspective for understanding the evolution and variation of dialect use.

4.3 The significance and value of the community

The dialect community provides a platform for members to discuss and use dialect through exchanges, which not only helps to break the barrier of dialect cognition, generate new knowledge sparks, but also promotes the knowledge negotiation and the identification of the community through the collision of different views.

4.3.1 Dialect knowledge barrier and knowledge consultation

As mentioned above, the level of dialect knowledge is the threshold to define the “insiders” and “outsiders,” but this boundary has become vague or broken in the communication and even consultation of the group members.

B: (Besides treating dialect as a hobby) I also read the papers of the official science. I and my group will reject the statement that is obviously inconsistent with the official science. When group members have different views on an issue, I sometimes participate in their discussion, mainly based on the views of the official science.

D: (For the debate in the dialect group) This may be because someone starts from the perspective of the official science and have conflicts with the folk science. Sometimes when one cites viewpoints from academic papers, it may not be quite accurate. It is possible that what was investigated at that time in the papers was inaccurate, and not the pronunciation or real use of ordinary speakers. However, sometimes folk scientists could be more accurate in starting from their own point.

Even though both most of the group members and group owners are not professional learners, as they are accustomed to calling themselves “folk scientists” and call the formal language researchers “official scientists” as a reference benchmark, they will conduct “censorship” under the “official science” system (B). However, the interview found that “folk scientists” sometimes “examine” the “official science” too, and even question and criticize their certain views (D). They believe that their own language experience can offer valuable insights that may be overlooked by the orthodox perspective. This critical reflection of dialect enthusiasts on the official research results actually reveals the competition of intellectual authority and folk power, and these controversies reflect the deeper complementary relationship between the two. As the respondent D said, as the “folk scientists” are closer to the actual use of the language, they can sometimes find the language status ignored by the “official scientists.”

Therefore, it can be considered that the dialect dispute in this background is essentially a negotiation of dialect knowledge. This negotiation not only constructs the current situation of dialect knowledge, but also let the ordinary enthusiasts of dialect community transcend the role of learners and corpus providers, while serving as the creators, experiencers and evaluators of dialect knowledge in this process. This promotes the development and dissemination of dialect knowledge and understanding.

4.3.2 Silent external environment and active internal dialect circle

In contemporary society, there is sharp decline in the use of dialect in real life, and dialect communication atmosphere among many young peers in the geographical relationship is very weak (C). Some elderly people even gradually give up using or teaching the next generation their dialect out of the concept of “dialect backwardness,” without realizing that this is a cultural abandonment and sadness (D). The objective contraction of dialect environment and the subjective lack of dialect identity both prove that the ecological crisis of dialect does exist (Qian, 2010; Lei, 2012). However, the active degree of the dialect community is in sharp contrast to it, with constant stream of messages and an overall high level of popularity in the group (A, B). Even some group owner suggested that the examinees temporarily withdraw from the group to avoid distraction (B), which fully reflects the humanistic care.

A: Now there are more than 300 people in my group, but in fact, there were 500 last year, and since the WeChat group was limited on the number of members, I cleaned up some who did not talk. So basically the group can stay active from morning to night without me to lead at that time, and now it always needs me to bring the topic.

B:(Group regulations) It is suggested that the examinees temporarily quit the group, which is also borrowed from other circles, because there are too many group messages that may not be conducive to their review.

C: According to my observation, peers in Nanchang rarely speak dialect, so I want to create an atmosphere of speaking dialect and listen to what others say, and then I can secretly write down and ask them… This group at least let members know that they can speak dialect here and have the awareness of speaking it. In other groups, they may have embarrassment speaking dialect, but here, it is no problem at all.

D: The small group is more welcomed within fellow townsmen, and the big group is more popular within big guys. I think the group members may be either interested in or familiar with dialect, or they are people who study or work in non-local places and so are unfamiliar with their dialect, but want to learn their standard dialect from the group, or find a spiritual sustenance. Now even many elderly people are ashamed of their dialect, mainly because the local social and economic development is not good. They may find the reasons from the individuals, and eventually find on dialect, feeling inferior when speaking dialect and superior when speaking Putonghua.

In big groups with more members, the message volume is usually large (A), while small regional groups with fewer members (C, D) are easier to locate fellow townsmen, deepening the sense of place through discussion of local language, culture and history. According to the Carnival Theory of Bakhtin (1984), the interaction in the dialect community can be viewed to have the characteristics of subverting the real world order and the self-liberation, which can also be regarded as the performance of “virtual carnival era” (Zhao, 2017). The ecological crisis of dialects, coupled with the intensification of regional mobility in modern society, makes it easier for young people to alienate their mother tongue, and the dialect community just provides spiritual comfort for this vacancy in culture and identity. As respondent C says: “In other groups, they may have embarrassment speaking dialect, but here, it is no problem at all.” This can be further explained through Goffman’s (2008) self-presentation theory, which states that people tend to hide their true self and act according to the expectations of others. However, the dialect community exactly provides a stage to eliminate the false and preserve the true, allowing members to show their true aspect and rebuild the confidence in their dialect and culture. To sum up, dialect community not only provides a new way to rebuild cultural connection for enthusiasts during the gradual disintegration of traditional interpersonal relationship from the “acquaintance society,” but also fight against the dialect decline in the real world, and reshape the “virtual acquaintances society.” By sharing dialect knowledge and fun through virtual presence in online media, a social unity has been consolidated. These findings provide new insights into our understanding of the role of dialects in modern society and how to protect and promote such cultural practices.

4.3.3 Dialect discourse dispute and common identity belonging

In the community of dialect enthusiasts, the atmosphere is harmonious most of the time, but occasionally there will be discourse disputes too.

A: Since I entered the community, I have found that the debate about which dialect is more ancient has not stopped until today. For example, everyone can find out the sounds in their own dialect that are not in other dialects, and then say their dialect is more ancient. In essence, it is still the Chinese attitude of worshiping the ancient that is causing the trouble, that is, the more ancient, the more orthodox, and the more noble. But it is not beneficial for either Putonghua or other dialects. I think what you should know more is how your dialect evolved from ancient times to present, but this is too difficult for ordinary people to pursue… But there is no problem to consider we have the common identity, that is dialect lovers.

B: The contradiction among the group members can be divided into antagonistic and non-antagonistic. The antagonistic one is against group rules, such as regional discrimination and personal attacks; the non-antagonistic is inconsistency on a certain issue. When group members have different views on an issue, I sometimes participate in their discussion, mainly based on the views of the official science. (For the identity of the group friends) It’s okay to think that the group members are dialect enthusiasts. Entering the group means being willing to provide the corpus and observe the group announcement.

D: Those who join the group can be assumed definitely dialect enthusiasts. The group members are relatively harmonious, and even if there are different views, they will not curse others. Moreover, almost all members are well educated (with bachelor degree or above). But if someone speaks in extreme or ignorant ways, I will directly kick him. In my group, there was once a heated argument about how to pronounce a certain sound, and at that time I would maintain order and let them speak well without arguing.

According to the interviews, the disputes can roughly be divided into two types: sporadic “antagonistic contradictions,” namely regional discrimination, personal attacks (which will often be stopped and warned when happening); and more common “non-antagonistic contradictions,” namely constructive discussions of specific dialect details, such as the pronunciation of certain words (B, D). In the online interest communities, technology tastes and personal cultural capital often form the basis of status differences (Liang and Song, 2022; Sun, 2018); however, in dialect communities, members often engage in active discussions on ordinary linguistic phenomena, even involved in cognitive disagreements and sharp criticism. As mentioned by respondent A, the controversies over “which dialect is more ancient” and so on are long-term hot topics in the circle. These topics have also given rise to a deeper understanding of various language outlooks, such as language equality, language development and language variation.

From the above we can see that common concerns blur each other’s online identity, and group members only need to decide whether to participate in the discussions according to the topic content, level of interest and chat methods, without worrying about the status differences, such as the gap between “big guy” and “green hand” in the group. In this case, the eager discussion and controversy on some topics have become a display of the love and maintenance of dialect culture. The diversity of views in the dialect community has activated the atmosphere, and also highlights the initiative of the group members as dialect enthusiasts, showing the compatibility with each other. Therefore, the discussion of dialect community can be said to be a game of connecting feelings and exchanging ideas, with its internal debate a positive expression of identity. It gives members emotional support in the community and strengthens mutual identification.

5 Discussion

Dialect is not only an objective language existence, but also a cultural force to consolidate consensus. Against the globalization, dialect still functions in protecting the local memory and culture, maintaining the collective identity and national spirit. Using and learning dialect are not only a form of respect and preservation for traditional and intangible cultural heritage, but also promotion for social tolerance and mutual understanding. It is under such social demand and cultural background that the formation and development of youth dialect community become particularly important. In line with previous research (Li W., 2022; Liu, 2011), this study shares the common understanding that new media is positive for the dialect dissemination, and dialect protection is a kind of living inheritance through the media. Under a omnimedia perspective, dialect dissemination presents diverse and intricate characteristics, requiring innovative paradigms for the protection and inheritance of dialects (Zhou, 2020). Our study is an example and a support for such proposals. The most obvious finding to emerge from the analysis is that, the youth protects and disseminates dialect, which in turn helps to construct the youth identity, with new media serving as both the context and propulsion.

Through the investigation, at least two key points worth mention. One is the interdependence of the two new media platforms: Bilibili acts as a video circle spreading popular culture of dialect, forming a new type of social relationship, and WeChat acts as an acquaintance social circle, extending the interest from the virtual to real world culture. Another is the youth identity roles in the community. While the video creators and WeChat group owners play the roles of key opinion leaders and media elites, active group members as information contributors and dialect enthusiasts help to sustain the dynamic of the group. Through actively spreading dialects with their media literacy, the young generation strengthened their cultural consciousness in social development and ethnic integration, exemplifying cultural exchange in cyberspace. Therefore, unlike the traditional top-down approaches to dialect protection, media literacy and youth interest are defining features of the bottom-up dialect dissemination. This both echos with the national language planning and strategic utilization of new media, and aligns with the national goal for youth culture development and active youth participation in social activities.

According to the German sociologist Tönnies (2001), “community” (Gemeinschaft) refers to social groupings characterized by close, personal relationships and a sense of togetherness. The dialect community is such a community, bound by shared interests, beliefs and values. Studying these communities offers a window into youth culture, and their roles in inheriting traditional culture and telling Chinese stories. Therefore, this paper calls for further attention of academia research on youth dialect community, which can better guide the youth culture development, the protection of language resources--especially endangered languages--and the communication of excellent traditional culture. This approach can provide new ideas for online ethnographic study and enhance understanding on the construction of community identification in the cyberspace. Although this study offers valuable insights into dialect communities, it is not without limitations, notably the limited scope of the respondents and interview data, which may not fully capture the complexity of the subject. There is also a need for deeper theoretical exploration in linguistics, communication and sociology. Future studies should seek to diversify their data sources, and benefit from a more comprehensive interdisciplinary theories to enrich the theoretical underpinnings of the research.

6 Conclusion

With the online ethnography, this study is the first thick description so far on the youth dialect community on new media platforms, especially focusing on performance of youth pioneers. Analysis of their activities reveals the subculture and characteristics of the community, leading to the following answers toward research questions. First, the formation and operation of the community are a response to the decline of dialects and the rise of new media. It is an interaction between individual interests and collective attention, a combination of popular culture and traditional culture, and a product of orthodox niche hobby seeking to integrate into the revival and development of Chinese culture amidst modernization and globalization. Second, the community’s register showcases diversity and hybridity. In terms of field, discussions mainly center on dialects and related regional and traditional cultures; regarding tenor, members form an egalitarian and interdependent community of dialect enthusiasts, despite variations in the individual identities; as for mode, the integration of multiple symbolic code resources within dialect has given rise to a new variety of Internet dialect. Third, the dialect community indeed plays a constructive role in awakening the responsibility of youth and leading a new dialect culture. Through knowledge sharing, negotiation, reconstruction and even dispute, it enables members to liberate themselves, forge a unique identity as dialect enthusiasts, and establish a fashionable ideology of dialect pride.

Overall, this study underscores the potential for research on youth dialect community as a bridge for multilingual and multicultural studies. It contributes to sociolinguistics by enhancing our understanding of language variation, language attitude and dialect use among certain social groups. For communication studies, it illuminates how new media could shape the community ecology and identity. Additionally, it offers culture studies a lens through which to view the protection of language and culture heritage between the tensions of globalization and localization. This would be a fruitful area for further work. Moreover, the findings of the study have some practical insights: the preservation of dialects requires the joint efforts of the entire society that embraces diversity while forging a common ground. It is crucial to nurture and encourage the enthusiasm of younger generation and the general public as a positive social force in the protection of dialect and other legacies alike. In the digital era, new media is also essential for enhancing cultural exchange and fostering a sense of online community, contributing to a more interconnected cyberspace future.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Humanities, Communication University of China. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ZM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all the respondents in the interview for their helpful discussions on the topic related to this work, and Daqin Li in Communication University of China for his support; besides, appreciation goes to Xuekun Liu in Central China Normal University for his help. Special gratitude is extended to the AI assistant Kimi (version: October 10, 2023; model: Kimi Chat), developed by Moonshot AI, for its valuable assistance during the linguistic refinement of this manuscript. (Source: https://kimi.moonshot.cn).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bakhtin, M. (1984). Rabelais and his world. H. Iswolsky, Trans. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bloomfield, B. P., Latham, Y., and Vurdubakis, T. (2010). Bodies, technologies and action possibilities: when is an affordance? Sociology 44, 415–433. doi: 10.1177/0038038510362469

Bowler, G. M. (2010). Netnography: a method specifically designed to study cultures and communities online. Qual. Rep. 44, 415–433.

Bromham, L., Dinnage, R., Skirgård, H., Ritchie, A., Cardillo, M., Meakins, F., et al. (2022). Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 163–173. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01604-y

Chen, Y., and Zhou, Y. (2021). The construction of cultural confidence in the ACG culture of National Style: taking the domestic animation “Spirit cage” as an example. China. Youth. Study. 10:5-13 + 38. doi: 10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2021.0143

Dong, J. (2023). Language of the new media community and identity construction: an online ethnography study on Bilibili bullet screen interaction. J. Lang. Policy Plann. 1:1–13 + 177.

Goffman, E. (2008). The presentation of self in everyday life. Feng G. Trans. Beijing: Peking University Press.

Goldthorpe, J. H. (2007). “Cultural capital”: some critical observations. Sociologica 1, 1–23. doi: 10.2383/24755

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: the social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Heuman, A. (2020). Negotiations of language ideology on the Jodel app: language policy in everyday online interaction. Discourse Cont. Media 33, 100353–100311. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100353

Kozinets, R. V. (1999). E-Tribalized marketing? The strategic implications of virtual communities of consumption. EMJ 17, 252–264. doi: 10.1016/S0263-2373(99)00004-3

Kozinets, R. V. (2002). The field behind the screen – using netnography for marketing research in online communities. J. Mark. Res. 1, 61–72. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.39.1.61.1893

Lewin, K. (1943). “Forces behind food habits and methods of change” in Reader in public opinion and communication. eds. B. Berelson and M. Janowitz (New York: Free Press), 235–265.

Li, C. (2022). Consumption practice and formation mechanism of emerging sports subculture and tribal communities. China Youth Study 10, 5–12. doi: 10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2022.0134

Li, W. (2022). Living inheritance: reflections on the short video practice and value of dialect transmission. China Radio Telev. J. 9, 65–67.

Li, W., and Shen, Q. (2021). Translanguaging: origins, developments and future directions. J. Foreign Lang. 4, 2–14.

Liang, J., and Song, Z. (2022). Knowledge, taste and identity: a study on the Technology Community in Short Video Platforms. News Writ. 6, 27–40.

Liu, J. (2011). Deviant writing and youth identity: representation of dialects with Chinese characters on the internet. Chin. Lang. Discour. 2, 58–79. doi: 10.1075/cld.2.1.03liu

Murthy, D. (2013). Ethnographic research 2.0: the potentialities of emergent digital technologies for qualitative organizational research. JOE 2, 23–36. doi: 10.1108/JOE-01-2012-0008

Pimienta, D., Prado, D., and Blanco, Álvaro. (2009). Twelve years of measuring linguistic diversity in the internet: Balance and perspectives. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187016 (Accessed September 11, 2024).

Qian, N. (2010). Shanghai dialect Drama and Shanghai culture. Shanghai Theatre 4:8-9 + 19. doi: 10.14179/j.cnki.shxj.2010.04.015

Scaramuzzino, G. (2012). “Ethnography on the internet – an overview” in Pondering on methods. eds. K. Jacobsson and K. Sjöberg (Lund: Faculty of Social Sciences Lund University), 41–54.

Shi, S. (2015). Reflections on the dialect protection from the perspective of language planning. J. Lang. Plann. 1, 72–78.

Song, Y., and Feng, Y. (2023). How does a new media linguistic community come into being: taking the language practices of the BYM community on Sina Weibo as an example. Lang. Policy Plann. 1, 26–38. doi: 10.19689/j.cnki.cn10-1361/h.20230102

Sun, L. (2018). Operating mechanism and power relations of youth subcultural group: based on the study of 13 Fansub groups in China. J. Chongqing Univ. Posts Telecommun. 4, 102–108.

Tönnies, F. (2001). Commun. Civ. Soc. J. Harris and M. Hollis Trans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 17, 19.

Trudgill, P. (1972). Sex, covert prestige and linguistic change in the urban British English of Norwich. Lang. Soc. 1, 179–195. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500000488

UNESCO. (2003). Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/convention-safeguarding-intangible-cultural-heritage (Accessed September 11, 2024).

Wang, Y. (2017). The formation mechanism of fan Community in the internet era: taking Lu Han’s fan Group as an example. Acad. Ther. 3:91-103 + 324-325.

Xiao, Y., and Wang, H. (2020). Application of local cultural elements in the Design of Creative and Cultural Tourism Products. Packag. Eng. 20, 228–233. doi: 10.19554/j.cnki.1001-3563.2020.20.037

Yang, X., Zhang, R., and Kong, L. (2022). Reinvention and popularity of “tradition”: the development of contemporary youth Hanfu culture in China. Contemp. Youth Res. 2, 40–47.

Yao, Q., and Zhuang, X. (2016). Investigation and filing work about Dongguan dialect. Cult. Heritage 2:126–132 + 158.

Yao, S., Jia, X., and Chen, R. (2019). The problems and suggestions of dialect archival preservation in China: based on the survey of Zhejiang and Shaanxi provinces. Zhejiang Arch. 8, 26–28. doi: 10.16033/j.cnki.33-1055/g2.2019.08.010

Zhao, X. (2017). The era of WeChat ethnography is coming soon: anthropologists’ awareness of cultural transformation. Explor. Free Views. 5, 4–14.

Zhou, Y. (2018). Exploration of dialect dissemination innovation based on Micro platforms. China Publ. J. 22, 30–32.

Keywords: dialect inheritance, youth identity, online ethnography study, new media platforms, dialect enthusiasts community, a community with a shared future in cyberspace

Citation: Mei Z (2024) Dialect inheritance and youth identity: an online ethnography study on dialect enthusiasts community on the new media platforms. Front. Commun. 9:1464284. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1464284

Edited by:

Bala A. Musa, Azusa Pacific University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kehbuma Langmia, Howard University, United StatesEddah Mutua, St. Cloud State University, United States

Nelson Kiamu, ABC University, Liberia

Copyright © 2024 Mei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhixing Mei, bWVpemhpeGluZ0BjdWMuZWR1LmNu

Zhixing Mei

Zhixing Mei