- Department of Communication, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain

The influence of the zoological park industry on public compassion remains an understudied area that is pivotal to understanding how public relations—specifically persuasive communication—attempts to shape public consent regarding the use of animals in entertainment. This paper addresses this issue by conducting a critical discourse analysis of the main interest groups in Spain’s zoological park industry: AIZA, Grupo Parques Reunidos, and Loro Parque Fundación. The results show that despite these actors’ compassionate self-representations, they use objectifying language, biological hierarchization, and commodification to represent nonhuman animals. In particular, they portray themselves as “advocates” for animal welfare and legitimize their efforts through a process akin to ethics washing. They use thematic elements and emotional engagement to convey the concept of the “modern zoo.” Finally, they strategically acknowledge societal compassion and frame themselves as aligned with current societal values and attitudes. We conclude that the current discursive strategies of the main Spanish zoological park industry lobbies go beyond the typical arguments related to entertainment, science and conservation, instrumentalizing public compassion to justify the captivity, confinement and exhibition of nonhumans.

1 Introduction

For millennia, dating back to Mesopotamia around 2,000 before our era (Croke, 1997, p. 211), capturing animals from nature for human display has been done, and justified, for various purposes. At present, all over the world, hundreds of thousands of nonhuman animals are kept in captivity and exhibited in zoos, aquariums, and animal theme parks, also known as zoological parks—and industry which we refer to here as the zoological park industry (ZPI).1 Due to the entertaining nature at the core of these businesses, these can also be considered a key segment of the animal-based entertainment industry, which is part of the animal-industrial complex (Noske, 1989; Twine, 2012; Almiron, 2024), the complex of industries whose business is based on the use and/or exploitation of other animals. According to the ZPI and its supporters, nonhuman captivity and exhibition are necessary to ensure species’ survival, protect biodiversity, educate the public, and improve welfare standards and practices with so-called wild2 animals in captivity and nature.3 The zoological park industry, therefore, presents itself as committed to the protection and welfare of non-human animals, which is consistent with a compassionate approach. However, a historical analysis of its underlying rationale shows that the ZPI has consistently centered on human benefits, initially focusing on curiosity and entertainment, and later evolving into scientific and conservation motivations—formulated as being in the interest of animals but essentially driven by human interests (Emmerman, 2020).

Unlike what the discourse of the ZPI might promote, it is essential to bear in mind that the majority of animals on exhibit are not endangered,4 and that the industry’s impact on the habitats and species it claims to protect and reintroduce is minimal compared to the magnitude of the problem. This industry is a profit-driven industry5 with a century-long history of destroying wildlife to trade and acquire animals (e.g., Savall, 2016), and a present filled with scandals of animal suffering (e.g., Hargrove, 2016)—with animal resistance to zoos becoming the blatant evidence of this suffering (Hribal, 2010). As Margo De Mello noted, it is difficult to imagine that an industry with such a background should be a social institution responsible for conserving species and guaranteeing animal wellbeing. This is particularly evident as the underlying problems of massive habitat destruction, species extinction, climate change, and pollution continue to flourish (DeMello, 2012, p. 106). In this context, it is worth examining whether the industry’s claim to align itself with society’s compassionate values is consistent with its actual discourse about nonhuman animals. This is the purpose of this paper.

With the emergence of the animal rights movements, the increase in ethical concerns within society, and the introduction of the animal standpoint in academia—which commits to representing the perspectives and viewpoints of nonhuman animals who have historically been marginalized (Horsthemke, 2018; Almiron and Fernández, 2021; Horsthemke, 2024), more researchers have started considering the power imbalance that plays into our relationships with nonhuman beings. In the case of the zoological park industry, this has meant unveiling the political, economic, and social aspects of animal exhibition practices—as a display of the elites’ power until the mid-20th century (Kalof, 2007; Malamud, 1998), as a profitable business (Almiron, 2017; Laidlaw, 2017) and as an expression of the relentless human domination and control over individuals of other species (Acampora, 2010; Malamud, 1998).

The field of communication is not an exception. Communication ethics is concerned with the moral good present in all human communication. We use critical public relations (CPR) as our primary lens for this study. In order to challenge assumptions, alter boundaries to cause paradigm shifts, and produce a critique of conventional theories, policies, and practices, CPR draws on the critical theory of the Frankfurt School (L’Etang, 2005). The task of the critical public relations scholar, according to Motion and Weaver (2005), is to “investigate how public relations practice uses specific discursive strategies to advance the hegemonic power of particular groups and to examine how these groups attempt to gain public consent to pursue their organizational mission” (p. 50). In like manner, Heath and Xifra argue that the goal of the field is to move beyond the simple criticism of public relations and toward “a social critique that leads to human and social emancipation” (p. 200). In like manner, Critical Animal Studies scholars have addressed the exploitation of other animals through various approaches and subfields, such as Critical Animal and Media Studies (Almiron et al., 2018), expanding the circle of ethical concerns in critical media and communication studies. These works include the creation of specific style guidelines for professionals in journalism, entertainment media, advertising and public relations and offer recommendations on the covering and representation of nonhuman animals that comply with the ethical principles of the media professions (Freeman and Merskin, 2015; UPF-Centre for Animal Ethics, 2020).

To this critical understanding, growing scientific evidence contributes to inherently problematizing the ZPI because of captive individuals’ physical and psychological suffering.6 Critical and non-critical approaches to this industry have also yielded some empirical results questioning the positive educational impact on visitors (e.g., Malamud et al., 2010; Balmford et al., 2007), which challenges the literature built around the educational benefits of zoos and aquariums from a human-centered perspective. Indeed, this literature has also been countered by studies showing that: the percentage of learning from visits is relatively low (Jensen, 2014), the overall methodology of the studies lack quantitative evidence (Spooner et al., 2023), and the role of education overall simply lacks robust evidence (Staus, 2020).

More recently, several studies have approached zoos and aquariums as “dark tourism” (Fennell David et al., 2021; Yerbury, 2023), including the use of iconic animals such as pandas (Guo et al., 2023), bullfighting (López-López and Quintero Venegas, 2021; Fennell and Sheppard, 2024) and hunting. The concept of dark tourism is mostly used to describe the tourist sites of (human) suffering and death but, as the literature also points out, nonhuman animals in zoos and aquariums are examples of dark tourism objects. What visitors and tourists contemplate in these facilities are animals who endure pain and suffering, whose flourishing is thwarted, and whose captivity arises from anthropocentric narratives of domination. However, unlike most dark tourism practices, zoological park visitors do not seek to contemplate the suffering, even if they are exposed to it unknowingly.

Finally, animal ethicists have also pinpointed the inconsistencies in the arguments posed by the zoological industry. Oscar Horta (2022), for instance, reminds us that the industries’ claim that the animals living in zoological parks are free from the harm they suffer in nature does not entail they are living well in the enclosures. Moreover, claiming that the harm these places may cause their captives is justified because it helps conservation in nature is a discriminatory approach toward animals since most people could never feel justified harming human beings to protect other species in nature or ecosystems.7

Overall, the need for an ethical examination of the zoological park industry is so unavoidable that even the industry is acknowledging it (Gray, 2017) while the public is increasingly aware of the ethical issues around zoos, aquariums, and animal parks, for example, through the stereotypic8 actions that indicate psychological suffering and are visible to visitors (Mason, 1991). In this context, more compassionate approaches are being promoted by international initiatives opposing the current system of zoos, aquariums, and animal parks. These initiatives call for the transformation of these spaces into sites more focused on animal care (e.g., for instance, for the recovery of injured, abandoned and exploited nonhuman animals), and they are responded to by the industry lobbies.9

Compassionate approaches are not solely confined to the advocacy sphere. Psychologists and philosophers have recognized the significant role of compassion as a moral emotion that promotes prosocial behaviors (Erlandsson et al., 2021; Price and Caouette, 2018; Arteta, 2019; Nussbaum, 2001). Whatever role we ascribe to compassion in morality, it motivates us to act in ways that alleviate the suffering of others, promoting an act of moral good as a result (Persson, 2021). The importance of nurturing and encouraging compassionate attitudes in society has also been part of the debate on moral education for a long time, be it from an anthropocentric, ecocentric, or anti-speciesist outlook (Donovan, 2007; Nussbaum, 2001; Abbate, 2018; Puleo, 2011; Singer and Klimecki, 2014). Consequently, the blocking or neutralization of compassion has been problematized for several reasons, including the fact that it normalizes and naturalizes certain violences that affect society as a whole (Joy, 2011; LaMothe, 2016; Abbate, 2018), as well as the unethical practice of “lobbying against compassion” (Almiron and Aranceta-Reboredo, 2022, p. 411), where actors with vested interests use persuasive strategies to maintain social consent for animal exploitation (Nibert, 2002; Spasser, 2013; Almiron, 2016). The study of compassion, or its cancellation, as a trigger of morality in relation to the persuasive communication of animal-based industries is a significant research gap that is the aim of this paper.

It is well known that interest groups and public relations play an important role in shaping public opinion and policymaking in contemporary democracies (Holyoke, 2020; Mullins and Mullins, 2024; Bitonti and Harris, 2017). Corporate lobbies (lobbying by individual companies) and industry lobbies (associations working on behalf of an entire industry) primarily aim to shape regulatory frameworks or prevent regulation from harming their interests, ensuring that their business conditions do not worsen but rather improve (Harris et al., 2022). They do this primarily by directly influencing policy-makers and by disseminating information, which includes messaging and creating discourse to shape public opinion. This approach creates a favorable atmosphere for policymakers to act by the industries’ interests and agendas (Rash, 2018).

The persuasive communications of the animal-industrial complex are no exception to this influential role (Almiron, 2024). We have defined the animal industrial complex elsewhere, based on Noske (1989) and Twine (2012), as:

a partly opaque and multiple set of networks and relationship between the economic, political, media, academic, and social elites to produce, promote, and perpetuate a systematic and institutionalized exploitation of nonhuman animals in all areas of business—mainly food, experimentation, entertainment, and nature—, with the result of nonhuman animals turned into forced laborers or participants, mere units of the productive system” (Almiron, 2024, p. 8).

Interest groups are particularly understudied for the animal industrial complex, and this is especially true for the zoological park industry. To the best of our knowledge, the study of the zoological park industry’s public relations practices through their lobbies, including corporate social responsibility, language, and ethics, has few direct and recent research precedents (Odinsky-Zec, 2010; Almiron, 2017; Almiron and Fernández, 2021; Aranceta-Reboredo and Almiron, 2024; Casal and Montes Franceschini, 2024).

A more general overview is provided by some other studies, including the discussion of the discourse of the zoo and about the displayed animals (Montford, 2016; Desmond, 1999), the examination of the dominant ideological discursive formations in zoo signage (Fogelberg, 2014), the shifting discourse of legitimation of zoos (Scollen and Mason, 2020), the Disneyization of zoos (Beardsworth and Bryman, 2001) and the speciesist discourse of animal-based entertainment in English (Dunayer, 2001). However, these studies do not consider or study interest groups.

Finally, although not specifically studying the zoological industry, Arran Stibbe’s work (Stibbe, 2001, 2005, 2012) can be seen as an inspiring precedent for this research. This work addresses the power and role of language in the social construction of animals, sheds light on the coercive power exerted by organizations that use animals, unveils the power of discourse in human dominance over nonhumans, and reflects on the fundamental assumptions that animal rights counter-discourses share with the oppressive discourses they criticize. The problematized issues include: using human-needs centered discourse of economics to counter the understanding of nonhuman animals as components or resources of ecosystems; de-centering the relevance and responsibility of humans in the relational dimension of valuing nonhuman lives; replicating speciesist hierarchies by associating species value to rarity, cuteness, power or majesty; not acknowledging agency in describing the oppression that nonhuman animals face; and associating the value of specific species to their abilities to perform arbitrary tasks while overlooking the importance of emotions (Stibbe, 2005).

Despite the increasing attention given to this issue, there is a lack of research focused on analyzing interest groups’ discourse on the matter. To this day, there is a need for more research on public relations in the animal-based entertainment industry, particularly on the ethics of their communicative practices and how these might affect the compassionate responses of the public. Our paper builds upon a body of research on the political economy of the oppression of other animals and the manufacturing of consent (Almiron, 2015), the ethics of persuasion in the Animal Industrial Complex (Almiron, 2024), the rhetoric of denial of the animal agriculture industry (Hannan, 2020), the connections between blocking the compassion toward animals and climate obstruction (Moreno and Almiron, 2024), and the negotiation of compassion in the discourse of the animal experimentation industry (Almiron and Khazaal, 2016; Almiron et al., 2024). We have previously argued that the lobbying activities that aim to influence policy-making and society to further business interests based on animal explotation revent compassion toward other animals (Aranceta-Reboredo and Almiron, 2024), and this article adopts a critical stance toward the activity of lobbying against compassion. Simultaneously, the paper sides with the following understanding of strategic communication practices that endorse activities involving animal suffering: it is not possible for them to contribute to ethical forms of public relations (Almiron and Fernández, 2021).

In order to understand the influential power these groups hold on societal attitudes, we have studied the public discourse of three of the key interest groups in Spain that support and promote the use of animals in captivity and exhibition for entertainment purposes. This paper explores how their strategies might relate to compassion and maintaining public consent for the industry’s practices, especially the commodification of consumers’ compassion.

This study answers a series of research questions that address the dominant representations, themes and power relations in the discourse of a selection of Spanish interest groups: What are the dominant representations of animals in the discourse of zoological park IGs in Spain? How do these IGs represent themselves, the industry and their actions? How do these IG’s represent consumers and the general public? Our hypothesis is that these interest groups often use strategic communication and public relations tactics to justify and defend their practices while attacking and discrediting animal rights activism. The results contribute to a better understanding of the political economy of interest groups and the communication strategies of one of the largest businesses within the animal-based entertainment industry, at a time of increasing awareness and concern for animal well-being.

2 Method

Our research examined three prominent organizations lobbying for zoological parks in Spain, two of which represent the interests of two of the most prominent companies in the sector in the country (Grupo Parques Reunidos and Loro Parque Fundación) and the third of which is a trade association (AIZA). Together, they account for the bulk of the country’s business in this industry. Their importance was determined by their activity as representatives of the industry in press, conferences, and the ownership or relationship with the most known and visited zoological parks in the country.

The most representative of them is the trade association AIZA (Asociación Ibérica de Zoos y Acuarios, or the Iberian Society for Zoos and Aquariums), founded in 1988 and with 50 members by 2024, according to its website, most of which are zoos, aquariums, or animal parks. AIZA belongs to and follows the guidelines of the EAZA (European Association of Zoos and Aquaria) and the WAZA (World Association of Zoos and Aquariums), the two largest international trade associations for the zoological industry. AIZA defines itself as a professional association representing the best zoos and aquariums in Spain and Portugal.

The two corporate lobbies are Grupo Parques Reunidos and its associated foundation (Fundación Parques Reunidos) and Loro Parque Fundación. Grupo Parques Reunidos was founded in 1967, while its foundation was born in 2011. Its website describes it as the largest operator of animal parks in Europe and “one of the world’s top animal collections by number and diversity.” In turn, Loro Parque Fundación (LPF) was founded in Tenerife in 1994 and is associated with the Loro Parque zoological park, born in 1972.

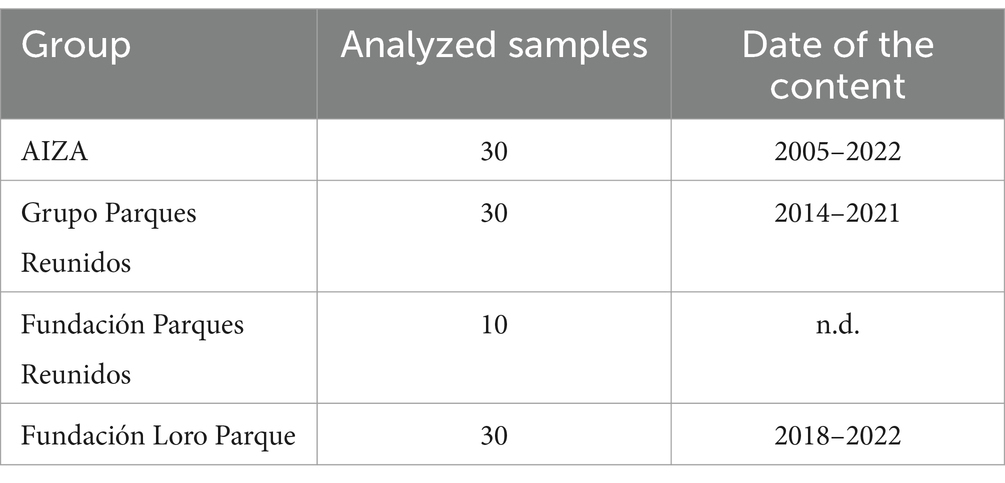

The study’s corpus comprises 100 texts from the association’s websites, spanning 2005 to 2022 (Table 1). While websites are not the primary tool for lobbying, zoological industry websites provide a resource with great potential for analyzing the discourse of these interest groups. This is because lobbying by organizations is mostly a hidden, undisclosed activity—most lobbying is done through direct communication, coalition building, policy briefing, public relations, media campaigns, or grassroots mobilization, among others. The website plays an important complementary role by providing a platform for information dissemination and public engagement, serving as the primary repository for these groups’ key messages and thus the most accessible source for understanding their public communications and advocacy efforts. Moreover, the fact that these sites are designed for public viewership is significant in itself; from a critical public relations perspective, interest groups’ websites can be considered industry promotional content.

As a result, its analysis helps illuminate the strategies and priorities of these organizations in the absence of more transparent reporting of their activities.

The collection and analysis of the texts were carried out simultaneously, and both processes were stopped when saturation was reached, i.e., no new data were obtained from the analysis. A discourse analysis within the perspective of critical discourse analysis was applied to the texts (van Dijk, 2001). The sampled texts were analyzed by a researcher with previous experience in qualitative text analysis, including critical discourse analysis, and random samples were reviewed by a second researcher. Both researchers have worked in the making and refinement of the coding sheet used for the analysis. The methodology we used to analyze the IGs’ texts is a combination of content analysis and critical discourse analysis (van Dijk, 2001; Zengin, 2019; Almiron et al., 2024), allowing us to identify frames. We developed a template of analysis that distinguished between three discourse levels: the representation and actions attributed to nonhuman animals, industries, and consumers. We looked at the explicit (literal) and implicit (implied) arguments for each group, with particular attention on how compassion is negotiated; that is, whether it is supported or discouraged, and if it presents a real or manufactured story. This analysis involved examining the most common rhetorical devices and categorizing the ideas under themes across the three levels.

The analysis was complemented by NVivo, which was used to identify the contexts of the appearance of identified ideas and themes in texts that exceeded an appropriate length for the manual coding. The sample of texts consisted mainly of introductory statements, news, educational content (teacher’s books, handbooks, manuals), specific reports (on the association’s strategy, sustainability, and guidelines), and the journal of Loro Parque Fundación (Revista Cyanopsitta). We show discourse patterns in the three dimensions mentioned before that shed light on how lobbies appeal to the public’s compassion for captive animals.

3 Results

3.1 The representation of nonhuman animals in captivity and exhibition

This first section examines the discourse employed by the Spanish lobbies to represent the nonhuman animals used by the ZPI lobbies within the contexts of captivity and public exhibition. This representation includes objectifying language, the establishment of biological hierarchies, and transforming animals into iconic and commodified entities.

3.1.1 Objectifying language

The lobbies’ discourse promotes species-thinking, that is, thinking of nonhuman animals collectively within their own species rather than as individual beings. It is not only that nonhuman animals are collectively thought of as a “stock” through objectifying language; each species, by itself, is also understood collectively and composed of specimens that only matter insofar as they meet the desired or ideal characteristics as representatives of the species to which they belong to. An exemplifying case is the museum rhetoric that the lobbies employ.10 These individuals are not just “zoo animals” but “zoological collections,” “our collections,” and “animals of a collection” kept “in display.” As “specimens,” the same number of individuals can be part of the “required” quota or a “surplus.”11

Our sample also depicts nonhuman animals in mass nouns. The symbolic action of pointing and naming is a common and basic communication practice used to discern nature and other animals. However, not all naming processes have the same implications for identification practices that result in individualization. “Charismatic megafauna” is differentiated as “especially unique and separate from a natural environment” with a hierarchical and binary discourse of individuality (Milstein, 2011, p. 19) found in the discourse of the group. Other less “charismatic” individuals are given less consideration or intrinsic value, with a tendency to identify animals by mass or species instead of plural nouns, which frames some animals as a unit that stands in for a larger homogeneous category (Stibbe, 2001). Within this group, their reproductive control and lives are objectified and relativized. For instance, to “regulate the size of their stock” they are sent to other institutions or killed, with euthanasia considered as “another method of population control” and a “quick death, in a ‘pleasant’ environment.”

This treatment and discourse surrounding nonhuman animals confirms Chrulew’s reflection on individuals in zoos only being perceived as “a token of its inexhaustible taxonomic type”; each nonhuman animal is “in principle replaceable” by another “specimen” to be viewed (Chrulew, 2011, pp. 141–142). Explicitly in the discourse, the individual in captivity is positioned as a symbol standing in for their entire species, which makes an independent subject stand for the whole. This implies that they are objectified and that “the knowledge of the species is predicated on getting to know this archetypal individual” (Scollen and Mason, 2020, p. 5). These lobbies employ the zoo rhetoric, used to justify the existence of zoos by emphasizing education, conservation and care, thus continues rendering nonhuman animals as objects to be viewed, used, and dominated by humans, as specimens in display (Malamud, 1998) in Spain. Marking certain bodies as suitable captives to be viewed—normalizing spectacle—the industry presents such captivity as a necessary epistemological educational condition (Montford, 2016). Moreover, the requirements to belong to an association like AIZA include the following ownership and use of animals: “To have a collection of wild animals for conservation, reproduction and exhibition for public viewing.” On the other hand, classification of nonhuman animals as tools for science and conservation mirrors the objectification and management that museums are denounced for in conversations about Indigenous repatriation of artifacts and remains: “academic and scientific opinion that educational interest and scientific significance hold greater substance than do cultural claims” (Tredan, 2018, p. 101).

3.1.2 Biologic hierarchization

The lobbies’ discourse also creates a binary narrative of Us vs. Them when talking about (i) humans vs. nonhumans, (ii) human vs. nonhuman interests, and (iii) endangered vs. non-endangered animals. A division is created between each pair, and the latter is represented as inferior. This hierarchical language is set by speciesism and human exceptionalism, binarist language is one of the tools that reflect this hierarchization of species and promote it; by turning dualism into value dualisms, this language provides “the conceptual bases for exploitative and oppressive practices” (Gruen, 2014, p. 45).

First of all, the use of the terms “wild animals” or “wildlife” reaffirms the “wild” origin of these individuals. In opposition to civilization, reason and culture, this categorization has been historically used by zoological parks and other entertainments that use nonhuman animals to justify “wildlife management,” that is, handling these nonhumans as mere business assets and placing them in a moral relevance of other wild non-animal life to be managed like any other museum exposition. Even when these biological hierarchies may simply follow the objectifying scientific discourse of the larger conservation movement, these concepts have already been linked to the industry’s interests by Joan Dunayer in her pioneering work (Dunayer, 2001). Dominant scientific discourses and practices have previously been questioned (Stibbe, 2001; Stibbe, 2012) by adopting an ecofeminist insight into the problematics of binarist human vs. nature language (Donovan, 2007; Puleo, 2011) and communication studies, which provides a tool for encouraging critical-relational consciousness on the questioning of the use of language, discourses, identities and representations and its power-relations (Houde and Bullis, 1999). Aiming for an absolute scientific “objectivity” does not weigh all the necessary information and perceptions (Nussbaum, 1996, p. 56). As the pioneering essay by Cronon (1996) on wilderness pointed out, wild is but a dualistic construct, romantizised and exploited, where the boundaries between humans and nonhumans have been built and are now commercially exploited and tamed.

Focusing on their status as “genetic reservoirs” or species/specimen representatives, the lobbies’ discourse biologizes the complexity of wild nonhuman animals. Reduced to their biological characteristics, their individuality, complexity and emotional lives are erased. This is done according to the species, degree of endangerment, and the “genetic value” assigned to the individuals and their potential to attract visitors as “charismatic” species. Biology is also used to justify the control of their populations since they “regulate the size of their stock” by sending them to other institutions or killing them. The fact that species are prioritized for their reproductive capacity and associated biodiversity value has long been a common criticism of the environmentalist approach by animal ethicists (Horta, 2018; Faria and Paez, 2019). The hierarchization that places endangered and “iconic” species over others has also been critizised because it might “may supersede discursive channels that inform narratives of complex interdependence and reciprocity, narratives that are imperative if entire ecosystems, their interrelated parts and processes, are to flourish” (Milstein, 2011); in making them the symbols of a vulnerable biological diversity and surrogates for wilderness, other individuals are left vulnerable in the debate of their management and use (Cronon, 1996).

The discourse of the lobbies shows that species are prioritized for their reproductive ability and associated biodiversity worth. This is illustrated by the fact that a lobby presents culling as a “quick death” in a “pleasant” environment that is motivated by “objective welfare reasons.” The interest group presents a situation where the death of individuals for stock management is considered desirable while objections to such practices would only be “raised on anthropocentric ethical grounds.” The omissions of suffering and different accounts of the knowledge show the “un-said” of the discourse, an assertion of power on the authority to determine decisions considered scientific matter (Biron, 1998).

Moreover, in a document by Loro Parque Fundación on “false arguments against keeping marine mammals in human care,” our sample explicitly mentions this hierarchization and links it to cultural relativism. Answering criticism that considers animal-based spectacles non-educational because of the taught human supremacy, the interest group states that: “Human superiority over animals may not be educational, but it is not immoral. It is only presented as immoral in some contemporary cultural trends” (Loro Parque Fundación, 2022, p. 49). This concern is answered rationalizing and relativizing human-animal hierarchic relationships. By reflecting the supposed superiority of humans, this exceptionalism is used to justify the dominion and exploitation of other animals for human benefit (Hall, 2011, p. 378); even when acknowledged as non-educational, the exploitation of nonhuman animals is shown as moral.

3.1.3 Iconic and commodified animals

A common trait highlighted for the zoos of the past was the “charismatic megafauna” species that are the visitors’ favorites and, therefore, tend to be prioritized for display by zoos (Holtorf and Ortman, 2008, p. 9), named and described with more significant and distinctive details to the public.

Individuals of these “iconic” species remain highlighted as “stars” in our sample news sections, newsletters, and educational content. These individuals are also more subjected to anthropomorphizing, often depicted in cartoonish images, connected to merchandising (e.g., stuffed toys, t-shirts), or as ambassadors of their species.12 In encounters of children with “zoo tigers,” a text of our sample mentions that the caretakers gifted them “tiger stuffed animals and the family continued their stroll through the Zoo.” Claire Parkinson has written extensively on the problematics of how all nonhuman animals, but particularly those labelled as wild, are anthropomorphized in communication directed to children (2021). In this context, anthropomorphizing can be seen as a tool for commodifying, one of the most common marketing tactics used by zoos.

The Spanish lobbies further commodify nonhuman animals by ascribing to them a position of labor, be it in breeding programs, genetic value, or as representatives (“true ambassadors of nature,” “true ambassadors for their conspecifics in nature” and “perfect ambassadors to raise awareness”). Our findings exemplify the utility narrative that has driven the commodification of animals (Muhammad et al., 2022, pp. 7–8). Nonhuman animals are agents of production without agency, not doers.

When inner experiences like thought, emotion and perception are mentioned, the material realities of nonhuman animals are portrayed in positive ways. Appealing to the emotional dimension, there is content that motivates visitors to find animals and highlight family bonds and playing: “do you find them? They are with their moms or playing with the family!” (Loro Parque Fundación). Similar to the findings in Turkish media (Zengin, 2019), even if there is a concession of agency these portrayals are fun and exciting for humans; there is no pain, boredom or negative emotion, and they provide joy to humans with these actions.

The ZPI lobbies present animals as products that target different interests depending on the context in their portrayal of nonhuman animals as objects and icons, specimens and ambassadors, anthropomorphized and biologized. The disproportionate amount, emotional and depth of the content focused on specific individuals shows a direction of compassion and empathy toward the endangered iconic individuals; however, in the process, the ZPI simultaneously collectivizes and biologizes most individuals by attaching their value to their genetics, endangerment of species and interest for visitors. While the icons move between anthromorphization and biologization, they are mostly presented as ambassadors. In contrast, most individuals are kept within the commodified shadow without the visibility of the iconic status and are mostly biologized as specimens.

3.2 Self-representation of the Spanish zoological park industry

The values and meanings of institutions are expressed through their discourse. This discourse defines, describes and delimits the way in which certain topics and processes can be talked about; institutions provide, apart from descriptions, rules, permissions and prohibitions of social and individual actions (Kress, 1985, p. 7). This section focuses on the strategies of self-representation adopted by the studied Spanish ZPI lobbies. We have identified the following: the rhetoric of the modern zoo, presenting themselves as advocates, ethical and expert actors; legitimization through ethics washing; and thematizing themselves.

3.2.1 The modern zoo

The Spanish lobbies’ discourse adheres to the “modern zoos” rhetoric to define the zoological park industry activity—a concept discussed, for instance, by Odinsky-Zec (2010). The modern zoo is presented as a professional institution—a regulated and conservation-focused model that prioritizes conservation and “natural” enclosures for entertainment and as a selfless institution. When a lobby describes a zoo as such, it is because it “stood out as a modern zoo of the highest order for science and species conservation”—as Loro Parque Fundación describes.

With a reiterative use of improvement rhetoric and self-distancing from the origins of the zoos, our sample makes an effort to set themselves apart from the entertainment purpose of zoos, often covering it with the educational aspects of the activity. Other than describing a journey or transformation, this rhetoric emphasizes the value of the changes to convince that the transformation is happening, that it is necessary and positive. Loro Parque Fundación, for example, presents its sea lion spectacles as “educational presentations,” allowing visitors to learn about the animals’ “great intelligence” (Presentaciones de Los Animales Loro Parque, n.d.). AIZA, in turn, gives the green light to “Toca-Toca” tanks in their aquariums (with animals for visitors to touch) as practices that can contribute to visitors’ education and species conservation (Posicionamiento de AIZA sobre el mantenimiento de tanques de contacto toca toca, 2021).13 Grupo Parques Reunidos does not shy away from the entertainment implications but shares the altruistic claims tied to species extinction and scientific research, which contradicts its guidelines recommending “protective systems that prevent physical contact between the public and the animals.”

Another common characteristic of the modern zoo rhetoric is the inclusion of altruistic claims, thus portraying nonhuman animals as the primary beneficiaries of welfare and conservation programs. Such rhetoric of advocacy in communication implies the use of language effectively and persuasively; however, institutions often fail to advocate their own policies and philosophies, failing to engage in open critical conversations regardless of the rhetoric of progressiveness (Pickering, 2020, pp. 919–924). The public relations strategies that portray zoological parks as altruistic and non-interested have been critisized for not withstanding scrutiny when contrasting the discourse with their practices and for being considered unqualified to teach ethics on captivity, mostly because of their conflicts of interest and economic power to persuade and mislead people on the industry (Casal and Montes Franceschini, 2024). Through the caregiver figures (e.g., “A day in the life of a caregiver” in the educational material of Loro Parque) they convey an idealized and relationship-based version of the captivity, often relating it to the positive experience of a specific individual (e.g., Morgan, an orca at Loro Parque). Moreover, by collaborating with groups working on in-situ projects, animal-centered work and animal activists (e.g., the Jane Goodall Institute and Fundación Parques Reunidos in the news section of the latest), they extend that as part of their own work—even if it is donation-based, or part of a one-time collaboration. Such a strategy has been identified as part of the efforts by zoos in the past, such as SeaWorld after Blackfish (2013) came out, to reframe their role in the controversy by aligning with an animal rights group (Maynard, 2017, p. 2).

The interest groups studied employ educational materials, news, open letters, campaigns, and slogans to align the industry’s interests with those of nonhuman animals and biodiversity. For instance, in their efforts to “improve the effectiveness of the educational message,” they present “having a collection” of nonhuman animals as a requirement for the “maintenance of biodiversity” (AIZA, on the criteria to be a member). Interestingly, regardless of the distancing of the modern zoos from their past, the lobbies also acknowledge that “in many countries, the historical and social perception of zoos as merely beast menageries for entertainment still persists” which, they defend, “in some cases, it may be justified” (AIZA, in a translated WAZA document available on their webpage). These conflicting discourses reveal, as pointed out by Milstein (2009), the tension between multiple ideologies occurring together in the symbolic and material space of zoos: “As dominant ideologies assert and reproduce themselves, so, too, do alternative ideologies resist and challenge dominant ways of thinking and doing” (pp. 26–27).

3.2.2 Advocates for animal welfare in research

The lobbies persistently position the zoological industry as the foremost advocate for animal welfare in research: animal well-being is presented as a pivotal aspect of research, as it is in the industry’s best interest to enhance the visitor experience by showcasing more “natural” and less “stereotypic” behaviors.

Research is highlighted as relevant for training workers and the potential impact on captive and free-living individuals. For example, it is appropriate “to improve cetacean care and welfare practices” and to “guide future animal welfare research” so that zoos and aquariums can continually improve knowledge and tools for assessing the welfare of “species in their care.” Measuring factors of nonhuman well-being and research success include the ability to “maintain a high level of breeding” in captive environments.

In our sample, welfare is directly tied to their reproductive capabilities and the outcome of conservation programs: nonhuman animals are portrayed as “enjoying” the enrichment provided to them, which is associated with having a “high level of breeding.” Research also includes the development of “comprehensive programs that certify that animals are harvested [sic] using environmentally appropriate methods,” which is relevant because “nearly all tropical marine fish and invertebrates in aquariums are captured” (AIZA). The lobbies admit that this increases “conservation problems [...] which has long generated a debate on the positive and negative aspects of trade” (AIZA).

3.2.3 Legitimization through ethics washing

The lobbies’ discourse also attempts to build ethical credibility to gain legitimacy. They legitimize their own ideas and work while deslegitimizing other perspectives. This is done in several ways: with a conservationist rhetoric, the discrediting of activists, and the employment of ethics washing strategies.

The conservationist rhetoric legitimizes the actions of the industry by portraying their actions as going beyond legal requirements. They claim they do “more than what is required by law” mainly referring to Spanish Law 31/2003, of 27 October, Conservation of Wild Animals in Zoos,14 which calls for the conservation and protection of ecosystems and endangered species. Grupo Parques Reunidos, for example, asserts that they adhered to these principles before the enactment of this regulation, and claim that their “animal parks and marine parks ensure that all of our animals’ needs are met and even exceed government laws and professional standards.” At the same time, AIZA states that their “control and requirement is even greater since an extra verification is carried out using peer inspection,” which further places them as necessary and unreplaceable actors in conservation while emphazising the quality of their experts. Moreover, they ensure that.

“The fact that a zoo or aquarium is accredited as a member of AIZA is a public recognition of its management and professional ethics, a guarantee that it provides proper animal care and maintains a commitment to conservation, education and research.”

This is aligned with the ethics-washing strategies of industries (Breakey, 2023) in that it is used to mislead the government and the community into believing that the industry is more well-supported—and that it takes its social duties more seriously—than it constitutes. As Odinsky-Zec (2010) pointed out, the corporate social responsibility that modern zoos and aquariums are committed to is “a decidedly reactive rather than proactive stance and insinuates that necessity rather than genuine intention be the trigger” (p. 192).

Concerning the legitimization efforts, these also include confrontational rhetoric that neutralizes criticism or lawsuits. The IGs discredit activists by placing them in a polarized discourse of expertise, accused of “misrepresentation,” often dismissing opposing views as lacking “a scientific basis” or “journalistic ethics.” The critique received is “nothing more than a compilation of conclusory philosophical statements,” “legal actions based on vagueness” and “a false allegation” with the exclusive interest of “obtaining media coverage” that “does not respond to a real concern for animal welfare.” Overall, the actors use these responses to reaffirm themselves as the ones really “working for” the captive animals and place themselves as the victims of activist actions.

Ethics washing is the practice of superficially adopting environmental, social, or humane concerns in order to improve public perception and gain corporate benefits, while failing to implement meaningful or sustained ethical changes in the organization’s core operations (Ethics washing, n.d., Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs). While this concept is usually associated with diversity, equity, and inclusion, for this paper the strategy includes greenwashing (to exaggerate or falsely claim environmental responsibility), humane washing (to exaggerate or falsely claim compassion toward other animals), and social washing (to co-opt social justice or human rights for marketing without substantive change). On the one hand, the discourse of the lobbies AIZA and Parques Reunidos presents sustainability as a necessary condition for belonging to their groups and something they strive for. Greenwashing is tied to the altruistic ideal of being the “protectors” of habitats and species, something they claim to contribute to “with all available means, for the respect and protection of nature.” All the lobbies participate in key events and mention specific strategies that are applied in the parks (e.g., forest cleanups, eco-friendly cleaning products, plastic-free meals). They emphasize the zoological industry’s role in “maintaining biodiversity” and their engagement in “ethical” activities like donations or limited-time initiatives often linked to reducing pollution. The lobbies mention, for instance, a “first single-use plastic-free aquarium,” the “use of substances that do not harm the environment,” and even describe a center as “Eco Friendly.”

This environmentalist rhetoric, which is usually employed to advocate for environmental protection, however, only on a few occasions acknowledges the harms that captive environments inherently entail for animal wellbeing and does not address the ecological footprint of running these parks. It is mostly employed to present zoos as “Noah’s arks,” and has been identified as “underlying dominant in contemporary zoo design” (Mäekivi, 2016, p. 206). When such a footprint is addressed, it is often approached as part of their business plans as businesses that seek visitors. This is an argument that occurs within a frame of business and revenue as identified by Maynard (2017). This one is most common in Parques Reunidos. The environmental rhetoric, as a result, is mostly employed to present zoos as “Noah’s arks,” benefitting the public perception of zoological parks, and has been identified as “underlying dominant in contemporary zoo design” (Mäekivi, 2016, p. 206).

On the other hand, the legitimizing and polarized narrative is further pushed with humane washing and through the use of euphemisms (referring to enclosures as “ecosystems” and “habitats” where they are “housed”), positive portrayals associated with comfort (“all their needs are covered,” they have standards for “accommodation and care,” they are “housed” and “looked after” so that they can “enjoy” and “benefit from” what the installations provide), misleading descriptions (especially on “naturalized” enclosures that cater to the visitor), selective and constant reporting of successful actions and similar techniques. Their actions are part of a “professional and ethical management, the guarantee that it provides correct animal care and stays committed to conservation, education and research,” while criticizing the zoological park industry is presented as a “great harm to the fields of comparative psychology and behavioral science as a whole.” By doing so, the ZPI redirects the compassion and concerns of the public into aligning with the interests and work of the industry. Finally, the altruistic idea is present in the social washing of their institutions as well; all the IGs include news about specific activities with disabled, injured, sick or in-risk children. The lobbies market their installations as a source of joy for vulnerabilized groups in especific and special events —or paid activities that can be booked.

Overall, the industry’s small gestures may appear meaningful but have minimal impact at a systemic level while showcasing over-compliance—as evidence of moral rectitude may delay or deflect calls for more rigorous oversight or profound regulatory changes.

3.2.4 Scientific expertise, education and conservation

The lobbies under study also emphasize the zoological park industry’s purportedly superior knowledge of nonhuman animal care and welfare over that of activists and other social actors. The industry presents itself as “heroes of conservation,” “experts,” “educators,” and “protectors of the natural world,” in their capacity as “professionals” and “researchers.” This language coincides with the global phenomenon of, as Chrulew (2011) put it, zoos having “carved out their own moral niche as protectors (and exhibitors) of threatened creatures” within a regime of scientific “management” (p. 146). There is a persistent effort by the ZPI lobbies to define the sector’s activities as rational, objective, and scientific, which counters the portrayal of activists’ actions as lacking understanding of the complexity of the issues they denounce. For example, Fundación Loro Parque, in response to Blackfish (Cowperthwaite, 2013) and lawsuits, states that “criticisms were completely unfounded and not based on science,” while AIZA accuses the activists of lacking empirical evidence and not “even having visited the denounced zoo.”15 The opponents are presented as unscientific, only seeking “media repercussion” and harming “prestigious zoos,” while the industry reproduces scientific literature and claims to avoid “‘mascotism’ (i.e., the simple accumulation of animal species for mere display and commercial exploitation).” A particular example of this is the Encyclopedia of false arguments against keeping marine mammals in human care. Debunking common myths used against modern zoological institutions and dolphinaria of Loro Parque Fundación (2022).

To reinforce this appearance of scientific validity, the narrative also underscores the industry’s affiliations with universities, research programs, respected foundations, and its contributions to education and conservation, which entails “offering the experience to the visitors, by preparing facilities and species to provide an adequate conservation message.” By doing so, the lobbies portray zoos as crucial for “wildlife management,” conservation, and education.16 Within the idea of the “modern zoo,” they employ a discourse similar to the “milestone rhetoric” of the animal experimentation industry (Almiron et al., 2024): their work is “is framed as directly related with scientific progress and it is suggested that greater knowledge and understanding of the practice leads to greater support” of the industry (p. 9). Most importantly, they ascribe unscientific, even hidden agendas, to their critics while concealing the economic and anthropocentric motivations of the industry.

Critics of the zoo have long argued that the focus of zoos on “captive animal-based conservation efforts, in fact, sustains zoos as industries far more than it sustains wild animals, and may serve to funnel well-meaning but limited public conservation concern away from reversing the ongoing rapid destruction of wild animals and their habitats” (Milstein, 2009, p. 30). The ZPI misdirects the concerns and compassion of the public by only validating their position and presenting confinement and domination as necessary for learning about animals, which furthers the social reliance on zoos rather than allowing them to challenge it (Montford, 2016). Moreover, by reinforcing their legitimacy with objectifying, relativizing, rationalizing and conservationist discourses—previously highlighted on the biologic hierarchization section of nonhuman representations—they discredit any moral or other forms of knowledge that challenge this zoo reasoning, such as poscolonial theories and ecofeminist works.

3.2.5 Theme park-ization of the industry

The lobbies of our sample also present the ZPI as sincerely dedicated to providing a natural and environmentally friendly habitat for their animals as part of the thematization of their facilities as places of harmonious connection with nature. This practice has been a corporate trend in the zoological park industry for the last few decades, with Breadsworth and Bryman linking it to a “Disneyization of zoos” two decades ago (2001, pp. 91–92), and is still used to attract visitors in our sample. For instance, Grupo Parques Reunidos promotes one of its areas, Paradise Creek, as:

an extension of the existing dolphin lagoon, which will be decorated as a tropical island, with a white sand beach and an interactive dolphin pool for 300 people, creating a unique experience in the world. An all-inclusive package will offer visitors the chance to enjoy the lagoon, swim with the dolphins (a unique experience in Europe) and indulge in a variety of quality gastronomic offerings.

The promotional content of Atlantis Aquarium, owned and operated by Grupo Parques Reunidos and a member of AIZA, is a perfect example of the theming strategy. When describing their installations and “collections” of nonhumans, they employ storytelling: “From this moment on, a journey begins to the most important aquatic ecosystems of the planet, home to nearly 10,000 specimens of more than 150 different species, some as representative as the turtle (Caretta caretta).” The name itself evokes a romantic perception through the mythical legend of the lost city of Atlantis. They focus on the consumer experience and present the aquarium as “an educational leisure and awareness center of reference.” The spaces are “ecosystems”—on the first floor of a shopping mall in Madrid—which are “complemented by various interactive tests that allow you [visitor] to appreciate the power of a wave, follow tips for sustainable fishing or even recycle plastics to prevent the death of marine animals.” The dramatization of the visit and the experience reinforces the understanding of zoological parks as entertainment theme parks, which are mostly focused on the paying human customer instead of centered on the enrichment and experience of the nonhuman animals living there.

3.3 Representation of the public

This final section examines the ways in which ZPI lobbies portray the public. The lobbies’ discourse portrays the public as active participants whose visitation ostensibly results in collective benefits. The discourse also promotes an emotional engagement and “feel-good” factor that is directed toward their activities, and it dually perceives visitors as either customers or ambassadors.

3.3.1 Customers as active participants for the benefit of all

It has long been known that animal theme parks, zoos, and aquariums attract visitors by emphasizing the entertainment, educational, and scientific aspects of captive animal viewing while downplaying its implications for the animals themselves (Malamud, 1998). Our analysis adds to this the portrayal of the public as the beneficiary of the zoological park industry’s conservation, education, and scientific efforts. For this reason, people who visit their spaces—potential customers—play a pivotal role in the discourse of these groups. Also referred to as “the public” or “society,” customers are depicted as active participants in local activities and charity contributions, and their involvement or visitation leads to collective benefits.

For instance, Grupo Parques Reunidos manages “a business model based on safety and operational excellence, customer satisfaction, strict cost control and attention to detail”; while “providing vulnerable and special needs groups with access to an educational and leisure experience.” Their discourse includes their wish to “contribute to the development of a more caring and sustainable society through all its fields of action” and, simultaneously, the promotion of experiences all over Europe, including dolphin lagoons like the aforementioned Paradise Creek.

In this way, the ZPI activities are presented as benefiting humans through inclusivity, education and leisure while simultaneously compensating for humanity’s collective damage to the planet. For instance, when asking for donations, they claim that “any amount of money becomes an active form of combating against the sixth mass extinction of species, triggered by human activity.”

3.3.2 Emotional engagement and feel-good-factor

The public is also central to the rhetoric of compassion, empathy and altruism used by the ZPI lobbies. Directed toward consumers, the promotion of emotional engagement amongst the visitors involves the use of nonhuman animals performing or in entertainment settings for the purpose of evoking joy and fascination, and downplaying the ethical concerns associated with using captive animals that way through the feel-good factor.

On the one hand, the lobbies simulate emotional responses from the audience through animal behavior displays, something already pointed out by Beardsworth and Bryman (2001, pp. 97-98) in their predictions on the Disnetization of zoos two decades ago. Parques Reunidos presents themselves as “leaders in emotions,” offering “authentic emotions and sensations to the visitors and contribution to the conservation of different species.” In this context, the spectacles are presented as efficient in creating a connection with people who are “enthusiastic and compassionate and are well-informed,” and favoring an “essential collective solidarity” that zoos rely on to keep functioning. According to Loro Parque Fundación, nonhuman animals in shows are “not intended to display a catalog of behaviors of the species in nature; [...] they simply seek to create empathy toward the animals in the visitors.”

On the other hand, the promotional content of Atlantis Aquarium offers an excellent example of the feel-good factor prompted by environmental harm, as Grupo Parques Reunidos uses environmentalist thematic settings and storytelling to engage visitors emotionally:

Atlantis Aquarium invites visitors to immerse themselves in a journey that begins when a meteorite hits Madrid with a message of the future of a submerged civilization that warns of the consequences of climate change if action is not taken immediately. [...] the end of the tour to obtain the official accreditation as an ambassador of Atlantis.

This approach that seeks the feel-good-factor is shared by the lobbies’ discourse, and it usually offers either a futuristic or primitive exoticized cultural theming. The thematization of the industry is connected to the understanding of the consumer as well; it intends to inspire connection by simulating specific scenarios, ways of life or offering experiences. As Milstein (2009) argued, zoo-goers might be given partial and simplified views of causes behind human-caused harms but not given tools to “collectively resist or advocate for large-scale structural and systemic alternatives” (p. 40).

3.3.3 Visitors as both clients and ambassadors

Visitors are portrayed not only as customers but also as ambassadors. They are given the “opportunity” to collaborate through their visits and donations to the site while enjoying direct contact with the nonhuman animals they hope to help. Beyond this economic contribution by visitors, no other options for helping endangered species or other animals are presented. While the lobbies’ discourse mentions certain campaigns and NGOs to which they donate, they do not offer visitors the opportunity to collaborate directly with them.

This ambassadorial role is specifically prompted by promotional and educational materials that evoke human guilt over environmental degradation and species loss. However, as mentioned, the solution to the current problems that the environment and the individuals from the affected species suffer is mostly centered around visiting zoological parks or donating money directly to them. By limiting proactive responses to economic efforts that benefit the institution and creating achievements that are more symbolic than effective (e.g., becoming “ambassadors” by participating in tours at Atlantis Aquarium), the industry redirects moral emotions that could potentially lead to constructive criticism of captivity and zoos. This “zoo rhetoric” proposes emotion to influence in conservation ethics (Smith et al., 2010); however, the lack of frecuency of zoo visits without other experiences is “highly unlikely” to trigger such ethics (p. 63) in a proactive way.

It is necessary to point out that AIZA and Loro Parque Fundación approach consumer representation differently than Grupo Parques Reunidos. The three of them connect entertainment with the educational value of animal-centered captivity, highlighting animal “care” and the “conservation of threatened species.” AIZA and Loro Parque Fundación portray consummers as visitors and embassadors, highlighting that, through the visit, humans will help the environment and endangered animal species. However, Grupo Parques Reunidos’ goals are focused on the “satisfaction of [the client’s] expectations.” Even if the idea of the embassador is present in the experience of the clients as part of the theme park-ization of the installations, the group mostly emphasizes client satisfaction over animal welfare. Thus, their blog content is primarily promotional and focused on the fact that customers will find the “facilities and species” prepared for them if they go.

4 Conclusion

In an attempt to keep up with the times, the zoological park industry’s recent public relations efforts have, at least for the past few decades, synchronized to rebrand the industry as the modern zoo (e.g., Odinsky-Zec, 2010). That is to say, zoos as scientific experts, educational, sustainably-conservation-focused institutions and caretakers of other animals. This paper contributes to the critical analysis of the “modern zoo” concept by building upon previous literature through the lens of communication ethics. Additionally, our research exposes how Spain’s zoological park industry employs ethics washing strategies and commodifies consumer compassion through their discourse. The ZPI continues rebranding captivity-based businesses as conservation and animal care, ultimately maintaining the Statu quo while addressing social concerns and stifling ethical scrutiny.

This is achieved, first, through the way that the lobbies represent nonhumans in captivity and exhibition: through language, they are objectified, biologically hierarchized, and mercantilized as “iconic” animals. At the same time, the ZPI lobbies present the industry as an advocate for animal welfare in research, legitimize its work through ethics washing strategies that include greenwashing, humane washing and social washing, and the mentioned scientific expertise, education and conservation combination. Ethics washing undermines genuine efforts for sustainability and social justice by masking unethical practices behind a facade of corporate responsibility, and the unquestioned scientific discourse on conservation further contributes to the public potentially not questioning ethical issues of captivity that go beyond welfare.

They also employ theming in their installations and promotional content. Finally, the Spanish ZPI lobbies strategically employ emotional engagement, particularly compassion, in a repurposed manner when representing and addressing consumers. While compassion and altruism typically serve as the moral basis for animal advocacy, feminist and postcolonial theories’ efforts to end exploitation and captivity, the public relations discourse of the industry in Spain reappropriates these values to defend captivity, exhibition, and forced performance. The old scientific and conservationist discourses, together with new discoursive strategies and narratives that the zoological park industry employs still promote dominant ideologies that block resistance and change—all while the social and moral concerns evolve.

Compassion is thus commodified in the service of business, creating a hyperbolic contradiction. A moral emotion is used to perpetuate the confinement, exploitation, imprisonment and even killing in the name of science, conservation, and entertainment. This paper has explored such contradiction in the discourse of the Spanish zoological park industry lobbies that leave the Statu Quo unchallenged and unchallengeable.

In short, it can be argued that the Loro Parque Fundación, AIZA and Grupo Parques Reunidos, as main representatives of the zoological park industry in Spain, lobby against compassion for their economic interests. Spain’s ZPI strategically employs compassion to build a facade of responsible animal and environmental care at the service of humanity and other animals, misdirecting it toward the industry. The conservationist rhetoric and scientific reason-based discourse allow to keep treating some specific individuals as objects and biological tokens while not questioning how the zoological park industry should improve and transform; after all, the lobbies’ welfarist and progressive discourse especially highlights that the ZPI is doing it by itself, even if it is by commodifying it.

Future studies on the discourse of zoological park interest groups could potentially address some of the following questions: What ethical guidelines should the zoo organizations follow for more honest and transparent communication? What impact does the discourse promoted by zoological park interest groups in social media have on public opinion on zoos? What presence do these actors have in the Spanish news coverage? And how does discourse shift when addressing a reputational crisis? Does the experience of workers in the industry correspond with their representation by zoological park interest groups’ discourses? Although this list is by no means exhaustive, it provides some basis for improving the understanding of the communication and discourse of the animal-based entertainment industry, as well as their potential impact on society.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

OA-R: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and State Research Agency (Agencia Estatal de Investigación, AEI) under grant PID2020-118926RB-100/MICIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and the associated grant for hiring a predoctoral researcher (PRE2021-099988) that one of the authors benefits from, as well as from funding from the UNIC Research group (2021 SGR 00921).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the reviewers of this paper for their constructive and insightful feedback. For their comments and suggestions, we are grateful to Leire Morrás Aranoa and Júlia Castellano Llordella.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^A single association such as the American Association of Zoos and Aquariums reported 780,000 animals in its accredited facilities in 2024 (AZA, 2024).

2. ^In this paper we use the term wild or compound termswith wild in italics to highlight the implications of using that word in a categorical way by the industry.

3. ^These and similar arguments can be found, for example, in the communications of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (https://www.waza.org), the world’s largest zoological industry association.

4. ^For example, only 9.3% of the species reported by the American Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) in its accredited facilities are classified as vulnerable, endangered, critically endangered, or extinct in the wild according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (AZA, 2024).

5. ^Only the global aquarium market size was valued at USD 4.99 billion in 2020 (Worldmetrics, 2024).

6. ^Captive animals in zoos suffer from loneliness and noise (Davey, 2007), stereotypes related to suffering (Mason, 1991; Mason and Rushen, 2006), self-harm as a result of captive condition (Jacobs and Marino, 2020), chronic emotional, psychological and physical problems (Jacobs et al., 2021; Casal and Marino, 2022) that may end up causing premature death (Braitman, 2014). Cases of captive nonhumans needing antidepressants and antipsychotics have also been documented (Braitman, 2014).

7. ^It is important to remember that the industrial prison system is widely accepted in society and not often problematized. Usually, the exclusion of imprisoned humans from receiving a compassionate response from others is a result of the idea that they deserve punishment for their actions (Nussbaum, 2016; Gruen, 2014). However, in the case of other captive species, even when the captivity is problematized, compassionate responses are reduced because of its construction as something necessary for scientific and educational purposes.

8. ^According to the Zoo Animal Welfare Education Centre, stereotypes, “most commonly used indicators of poor welfare in zoo animals,” are “repetitive, invariant behavior without apparent immediate function [...] caused by the animal’s repeated attempts to adapt to its environment or by a dysfunction of the central nervous system” (Manteca and Salas, 2015).

9. ^Exemplified by initiatives like ZOOXXI: http://zooxxi.org. In 2018 the citizen initiative of ZOOXXI triggered the modification of the ordinance for the protection of animals in Barcelona, approved in May 2019, which involved a reconversion of the zoo. As part of the response, the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) moved its executive office from Switzerland to Barcelona to lobby against it (WAZA Executive Office Relocation–WAZA, n.d.). Loro Parque also sent a dossier to the Parliament to push against animal rights activists’ arguments.

10. ^We understand rhetoric as Greenwalt (2017) proposes: “as issuing from a set of specific and identifiable behaviors with the relevant audience limited to a specific space” (p. 114) that, through rhetorical ethology, has the potential to emphasize affect and emotion, challenge animals’ explotation, and “draw attention to the affective power of bodies rather than the biological qualities and comparisons of faculties so often used to justify the uniqueness of homo sapiens” (p. 123).

11. ^All translations from the original Spanish are by the authors.

12. ^For more on animals as ambassadors in the context of zoos, nonhuman animal work and animal diplomacy see Rickly and Kline (2021) and Aranceta-Reboredo (2022). For information on the limitations or negative effects of the ambassador role for nonhuman animals, see Acaralp-Rehnberg (2019), Lloro-Bidart (2014), and Spooner et al. (2021).

13. ^The statement was published on their website (AIZA, 2021). This statement, in fact, contradicts AIZA’s own guidelines on “Standards for the maintenance of species and their facilities,” the section on prevention of stress or harm to animals, points 23 and 24 (AIZA, 2009).

14. ^Ley 31/2003, de 27 de octubre, de conservación de la fauna silvestre en los parques zoológicos, Boletín Oficial del Estado, no. 258, 28 October 2003. https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2003-19800

15. ^In response to Free Morgan Foundation and Great Ape Projects lawsuits, respectively.

16. ^However, most zoological parks in Spain are not accredited members of the groups that speak for the industry. See Anexo: Zoológicos y acuarios de España (2022) for a list of Spanish zoological parks and their belonging to AIZA and EAZA.

References

Abbate, C. (2018). “Compassion and animals: how to foster respect for other animals in a world without justice” in The Moral Psychology of Compassion. eds. C. Price and J. Caouette (Rowman & Littlefield International), 33–48.

Acaralp-Rehnberg, L. (2019) Human-animal interaction in the modern zoo: live animal encounter programs and associated effects on animal welfare. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia.

AIZA . (2009) Estándares para el mantenimiento de especies y sus instalaciones [Blog] Asociación Ibérica de Zoos y Acuarios. Available at: (https://www.aiza.org.es/assets/documentos/paginas/Est%C3%A1ndares-Generales-AIZA_07_2009.pdf)

AIZA . (2021) Posicionamiento de AIZA sobre el contacto de visitantes con animales mantenidos en tanques ‘toca-toca’[Blog] Asociación Ibérica de Zoos y Acuarios. Available at: https://www.aiza.org.es/posicionamiento-de-aiza-sobre-el-mangtenimiento-de-tanques-de-contacto-toca-toca (Accessed May 27, 2022)

Almiron, N. (2015). “The political economy behind the oppression of other animals: interest and influence” in Critical animal and media studies: communication for nonhuman animal advocacy. eds. N. Almiron, M. Cole, and C. P. Freeman (New York: Routledge).

Almiron, N. (2016). Beyond anthropocentrism: critical animal studies and the political economy of communication. Polit. Econ. Commun. 4, 54–72.

Almiron, N. (2017). “Slaves to entertainment: manufacturing consent for orcas in captivity” in Animal oppression and capitalism. ed. D. Nibert , The oppressive and destructive role of capitalism, vol. 2 (Santa Barbara: Praeger), 50–70.

Almiron, N. (2024). Animal suffering and public relations. The ethics of persuasion in the animal industrial complex. London: Routledge.

Almiron, N., and Aranceta-Reboredo, O. (2022). Lobbying against compassion: A review of the ethics of persuasion when nonhuman animal suffering is involved. Methaodos 10, 410–418. doi: 10.17502/mrcs.v10i2.575

Almiron, N., Cole, M., and Freeman, C. P. (2018). Critical animal and media studies: Expanding the understanding of oppression in communication research. Eur. J. Commun. 33, 367–380. doi: 10.1177/0267323118763937

Almiron, N., and Fernández, L. (2021). Including the animal standpoint in critical public relations research. Public Relations Inquiry 10, 253–270. doi: 10.1177/2046147X211005368

Almiron, N., Fernández, L., and Rodrigo-Alsina, M. (2024). Illusory authenticity: Negotiating compassion in animal experimentation discourse. Discourse Stud. 26, 153–172. doi: 10.1177/14614456231219633

Almiron, N., and Khazaal, N. (2016). Lobbying against compassion: Speciesist discourse in the vivisection industrial complex. Am. Behav. Sci. 60, 256–275. doi: 10.1177/0002764215613402

Anexo: Zoológicos y acuarios de España . (2022). Available at: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anexo:Zool%C3%B3gicos_y_acuarios_de_Espa%C3%B1a#cite_note-1 (Accessed November 10, 2022)

Aranceta-Reboredo, O. (2022). And what about the animals? A case study comparison between China’s Panda diplomacy and Australia’s Koala diplomacy. Anim. Ethics Rev. 2, 78–93.

Aranceta-Reboredo, O., and Almiron, N. (2024). “On compassion, influence, and animal suffering” in Animal Suffering and Public Relations. The Ethics of Persuasion in the Animal Industrial Complex. ed. N. Almiron (London: Routledge).

AZA . (2024) ‘Zoo and Aquarium Statistics’ [Blog]. Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Available at: https://www.aza.org/zoo-and-aquarium-statistics (Accessed June 20, 2024)

Balmford, A., Leader-Williams, N., Mace, G. M., Manica, A., Walter, O., West, C., et al. (2007). “Message received? Quantifying the impact of informal conservation education on adults visiting UK zoos” in Zoos in the 21st century: catalysts for conservation? Conservation Biology. eds. A. Zimmermann, M. Hatchwell, L. Dickie, and C. West (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 120–136.

Beardsworth, A., and Bryman, A. (2001). The wild animal in late modernity: The case of the Disneyization of zoos. Tour. Stud. 1, 83–104. doi: 10.1177/146879760100100105

Biron, T. A. (1998) Our ancestors talk among us: indigenous knowledge in international repatriation. Masters thesis, University of Michigan

Bitonti, A., and Harris, P. (Eds.) (2017). Lobbying in Europe: Public Affairs and the Lobbying Industry in 28 EU Countries. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Blackfish, (2013). Directed by Gabriela Cowperthwaite. United States: CNN Films and Manny O. Productions. Film.

Breakey, H. (2023). “The social licence to operate: activist weapon, industry shield, empty buzzword, or vital ethical tool?” in Research in ethical issues in organizations. ed. H. Breakey , 1–10. doi: 10.1108/s1529-209620230000027001

Casal, P., and Marino, L. (2022). Entrevista a Lori Marino. La cautividad perjudica seriamente el cerebro de los mamíferos inteligentes. Mètode 113, 8–13.

Casal, P., and Montes Franceschini, M. (2024). “Fatal attractions: the ethics of persuasion in the animal-based entertainment industry” in Animal suffering and public relations. ed. N. Almiron (London: Routledge), 2–87.

Chrulew, M. (2011). Managing love and death at the zoo: The biopolitics of endangered species preservation. Aust. Humanit. Rev. 50, 127–142. doi: 10.22459/AHR.50.2011.08

Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness: or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environ. Hist. 1, 7–28. doi: 10.2307/3985059