- Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja, Loja, Ecuador

Disinformation generates political polarization and affects the quality of democracy, so understanding attitudes towards the regulation of disinformation will help society and its leaders to develop effective and inclusive approaches to combat this phenomenon. The purpose of the research is to determine the perceptions and propensities of Andean Community citizens regarding the regulation of disinformation. Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru have formed a political and economic bloc since 1969, and are subscribers to the Inter-American legal framework. The methodology is quantitative and qualitative, with exploratory and descriptive approaches. The instruments used are a survey, focus groups and expert interviews with experts, which were applied between July 2022 and May 2024, to establish trends and to avoid biases. It was found that 80% of respondents and participants in the focus groups agreed that misinformation alienates people from democratic representation and there was evidence of distrust in elections. A vision of regulation by states persists, through laws, rather than self- or co-regulation. The discussion revolves around the need for a multifaceted approach to combat disinformation, between regulation, media literacy and the responsibility of digital platforms, without compromising freedom of expression.

1 Introduction

Disinformation, according to UNESCO (Brant et al., 2020), is “false, manipulated or misleading content, whether intentionally created and disseminated or not, that may cause potential harm to peace, human rights and sustainable development.” In similar terms, the UN Special Rapporteur notes that it is “information intentionally distributed or intentionally created with the objective of undermining the public’s right to know and affecting the public’s ability to discern between (...) fact and fiction” (Kaye, 2016).

Disinformation is intentionally fallacious (Jack, 2017), denaturalizes facts to mislead audiences (Fraguas de Pablo, 2016; Sartori, 2016; Rodríguez, 2018), and it multiplies thanks to the opacity of technological infrastructures and legal loopholes (Persily, 2017),

Among the risks of disinformation are “the use of platforms for disinformation and the propagation of hate speech or discrimination [...] these are two threats to communication in democracy for multiple reasons” (Becerra and Waisbord, 2021, p. 305). Disinformation requires states to safeguard their institutions without restricting citizens’ freedoms and rights (Marcos et al., 2017; Pauner, 2018; Walker, 2018). For the European Union, disinformation is a latent threat to democracies (Bayer et al., 2019; Galarza, 2022).

Disinformation is also described as a type of belligerence whose “objective is to influence the opinions and actions of citizens” (Hanley, 2020, p. 74), “seeks to undermine public trust, distort facts, convey a certain way of perceiving reality” (Olmo-y-Romero, 2019, p. 4), but what is more delicate is “that citizens shun facts to replace them with content that instead fits their emotions or political beliefs” (UNESCO, 2021, p. 14).

Disinformation “is part of our daily lives and questions objective facts in journalistic and political discourses and replaces them with emotions and personal beliefs” (Masip and Ferrer, 2021, p. 3). The sustained presence of false data calls into question the credibility of contemporary journalism (Rodrigo-Alsina and Cerqueira, 2019), and affects the economic profitability of the media (Del-Fresno-García, 2019). It emerges in a scenario where both traditional and digital media are losing the trust of citizens, among other reasons, due to polarization and clientelistic arrangements (Newman, 2019; Salazar, 2022), in addition to traditional media being replaced by social networks as information channels that focus attention on stories rather than sources (Espaliú-Berdud, 2023).

Although it is not a recent phenomenon, today disinformation has a greater impact because it is easy for anyone to publish and share news or information online, through social media, and they are exposed to falsehoods for immediate dissemination (European Commission, 2018a; Vosoughi et al., 2018). Everyone can generate content with global impact, in the last century this capacity resided in media outlets characterized by deontological practices (Newman et al., 2020).

It is clear that “lies spread faster than facts. For some strange reason, facts are very boring. Lies, especially when they are accompanied by fear, anger, hatred, tribalism, spread” (Ressa, 2023). The future of journalism depends, in large part, on how the media fights disinformation (APM, 2019). Unfortunately, the digital ecosystem does not yet have a concrete model to make the public interest and freedom of expression prevail against disinformation (Mihailidis and Viotty, 2017; González, 2022).

To reduce the possible alterations of misinformation in public opinion and the quality of democracies, regulation models are proposed. The supervision of digital platforms is under debate in several countries, but there is a warning against legislation that violates the right to freedom of expression, due to the possible misuse of laws against the dissemination of misleading information, because the “judicialization of disinformation It should not be the only viable path. And this is because the right to freedom of expression protects even those who spread false information” (Slipczuk, 2023). “Behind projects that are presented with the laudable purpose of avoiding this danger, other objectives are often hidden, which tend only to censorship or self-censorship” (Jornet, 2020).

In 1976, the European Court of Human Rights concluded that freedom of expression applies not only to “information” or “ideas” that are favorably received, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any section of the population, without which there is no democratic society (European Court of Human Rights, 1976). From the Inter-American perspective, prohibiting the transmission of inaccurate information solely because of its lack of truthfulness is considered inconsistent with freedom of expression. Prohibiting misinformation is “structurally incompatible with the very functioning of democracy. In a true democracy, it has been said, the best remedy for lies is free democratic debate” (Botero, 2017, p. 82).

Regulating disinformation should not mean restricting the opinions of citizens, and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights noted that States were not allowed to place restrictions on freedom of expression in order to protect the principle of truthfulness or for the purpose of protecting the public from “deception” (IACHR, 1985). “The right to information encompasses all information, including what we call “erroneous,” “untimely” or “incomplete” information [...] By requiring truth [...] in information, one starts from the premise that there is a single, unquestionable truth” (OAS, 2000).

In Latin America, the Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued the “Joint Declaration on Freedom of Expression and Fake News, disinformation and propaganda” which clarifies that restrictions on the right to freedom of expression will only be justified “when provided by law and necessary to protect a human right or other legitimate public interest, including that it is proportionate, that there are no less invasive alternative measures that could preserve that interest, and that it respects minimum guarantees” (OAS, 2027).

An alternative to avoid the dangers outlined above is the self-regulation of platforms with clear guidelines for content moderation, aligned with freedom of expression. Self-regulatory mechanisms, particularly in developing countries and emerging democracies, allow media to voluntarily self-regulate through codes of conduct, and can be more effective than government regulation, which can be seen as censorship (Lim and Bradshaw, 2023).

A third path or convergent route is co-regulation, where the involved parts, companies, state and citizens, set performance standards for communicative practices and interactions. Co-regulation, also called regulated self-regulation, would be equivalent to self-regulation supervised by public authorities, such as codes of conduct developed by the companies themselves, but with compliance review mechanisms by state agencies (Sánchez, 2020).

The discussion should not be about allowing or prohibiting moderation by platforms, but under what public parameters they should act. The response to disinformation in democracies will be multilevel, combining international and national measures, addressing technical and legal aspects and integrating regulations with self-regulation (Sánchez, 2020). “A possible path for the regulation of disinformation is that nation states could establish general legal parameters for the moderation of disinformation, especially when it affects collective rights such as the protection of democracy” (Brant, 2022).

Proportionate and necessary measures would guide platforms’ actions and require states to stop being spectators to the erosion of democracy. The dilemma should not be whether to allow or prohibit content moderation on platforms to prevent disinformation, but rather under what public standards they should operate. Co-regulation would avoid arbitrary action by state control bodies, such as prior censorship, overloading justice systems, and would not leave all the power to the platforms to establish their own criteria over national legislation and international standards.

The regulation of disinformation is not “a solution of the problem, but to disseminate the principles of good and excellent journalistic and informative practice [...]. It is the new reality to which we must adapt, without trying to apply state coercion” (Zelaya, 2022). In digital environments.

it is often said that no legislation is better than bad legislation. However, [...] not debating possible regulation may mean the inclusion of laws that have little to do with the new forms of disinformation and much to do with the traditional use of propaganda (internal and external) to restrict our freedoms (Magallón-Rosa, 2019, p. 345).

Despite opinions against public regulations, “in 2018, laws were approved or entered into force in countries such as Germany, Canada, Ireland, France or Egypt [but] other countries, decided to go for digital literacy and the creation of action groups against possible external attacks” (Haciyakupoglu et al., 2018), while the European Union promotes transparency and responsibility of platforms, respect for privacy and freedom of expression in the form of codes of good practice on disinformation, independent networks of information verifiers, and strengthening media literacy, among other mechanisms (European Commission, 2018b).

In the European Union, a lack of cohesion in the regulation of disinformation is highlighted, there are challenges to guarantee transparency and the empowerment of users, and because there are different technological, political and cultural approaches. Anti-disinformation laws enacted in Germany, Greece and France were criticized for possible impacts on freedom of expression and the need for nuanced approaches. The same occurred in Turkey and the Philippines, where the implementation of anti-disinformation regulations caused journalists and organizations to allege threats against freedom of expression (Perelló, 2024). Around these reforms, it is appreciated that digital platforms took steps to combat disinformation (Roberts, 2022).

In Latin America, efforts to regulate platforms and against disinformation focused on verification agencies, legislation to penalize fake news and dialogues to establish ethical principles (Rauls, 2021). For its part, the European Union added awareness raising through citizen literacy to detect and counter disinformation (European Commission, 2018c). These experiences point out that one way to decrease disinformation is to promote media and information literacy (MIL) to increase citizen participation (Wilson et al., 2011).

At the beginning of 2024, the World Economic Forum indicated that disinformation and extreme weather events are two of the most important risks for that year (World Economic Forum, 2024), so it is still urgent to evaluate whether, despite regulations, society is facing a process of new forms of censorship and social control (Magallón-Rosa, 2023). There are two advanced experiences with respect to the democratic regulation of disinformation, on the one hand, the European Union’s Digital Service Act and the United Kingdom’s Online Safety Bill, which includes a security by design framework that requires companies to invest part of the systemic incentives of disinformation, which are inherent to the business design of the attention economy, to assess how to address the problems emanating from the architecture of the platforms.

In line with the above, there is an interest in studying people’s perceptions of the regulation of disinformation, a situation that has been investigated in Latin America, but not specifically among the alternatives between hetero-, self- and co-regulation. This study is limited to the four countries that make up the Andean Community: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, because they share a common culture, history and have formed a political and economic bloc since 1969 (CAN, 2024), as well as experiencing similar moments in the discussion on the regulation of Internet platforms (Dinegro, 2022).

The countries of the Andean Community participate in the Inter-American legal framework that considers guarantees for freedom of expression and subsequent responsibilities of the media and journalists in cases of disinformation. The legal framework of the Inter-American system for the protection of human rights surrounds guarantees for freedom of thought and expression.

Thus, the American Convention, in Article 13, the American Declaration, in Article IV, and the Inter-American Democratic Charter, in Article 4, offer a set of reinforced guarantees. This fact has been interpreted by the Inter-American Court as a clear indication of the importance attached to free expression within the societies of the continent. The Inter-American legal framework places a high value on freedom of expression because it is based on a broad concept of the autonomy and dignity of individuals, and takes into account the instrumental value of freedom of expression for the exercise of other fundamental rights, and its essential role in democratic regimes (OAS, 2009).

According to the Internet Society (2024), individuals who use the Internet as a percentage of the total population, on average in the Andean countries, is 71%, which points to an open environment that allows people and organizations to mix and match technologies with minimal barriers. And it contributes to stimulate innovation, therefore, there are conditions to use social networks with media skills to avoid the spread of misinformation.

The purpose of the research is to determine the perceptions and propensities of Andean Community citizens regarding the regulation of disinformation. The objectives of the research are (1) To establish Andean Community citizens’ preferences on models of disinformation regulation, between hetero-, self- and co-regulation; (2) To identify citizens’ knowledge and understanding of national policies to counter disinformation; and (3) To know communication experts’ impressions of platforms’ and states’ commitments to disinformation regulation.

2 Methodology

The methodology used is quantitative and qualitative, with exploratory and descriptive approaches, because variables are measured, describing them as they are manifested in reality (Hernández-Sampieri et al., 2014). The instruments used are a survey, focus groups and interviews with experts, which were applied between July 2022 and May 2024, in order to establish trends and avoid political junctures. The survey allows achieving the first objective of the research, the focus groups lead to the achievement of the second objective, and the interviews with experts contribute to the third objective.

Methodological triangulation is sought because it helps to examine different facets of a phenomenon using relevant instruments in a sequential manner (Creswell, 2014). The research instruments complement each other and together contribute to the fulfilment of the research objectives. Descriptive research produces data in “people’s own words spoken or written” (Taylor and Bodgan, 1984, p. 20), “it aims to define, classify, catalogue or characterize the object of study” (Chorro, 2020).

It worked on the basis of non-probabilistic convenience sampling because of the availability of the participants, and because it optimizes time “in accordance with the specific circumstances surrounding both the researcher and the subjects or groups under investigation” (Sandoval, 2002, p. 124). Respondents answered objective questions on a Likert scale and an open-ended question: Do you think that laws and control bodies should be created to combat misinformation, or is it a commitment of each media and social networking platform? The questionnaire is based on two previous research studies by Mosto et al. (2020) and Cerdà-Navarro et al. (2021).

A Google form was used to collect the data, between 14 and 28 May 2024, which were processed in SPSS statistical software, version 22. The reliability coefficient presents a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.94. A total of 120 people who reside in various cities in the Andean countries participated. According to gender, respondents are divided into 51 men and 69 women. The average age is 27 years. According to occupation, 46 were employed; 49 were self-employed or entrepreneurs; and 25 were studying or doing unpaid work at home or as volunteers.

Three online focus groups were conducted between 2 and 7 July 2022, due to mobility restrictions to avoid COVID-19 contagion, and to include participants from several Latin American cities, although the proportion of Ecuadorians and Colombians is higher. The participants were 18 people of legal age who agreed to participate in this academic research through informed consent, of which 8 are men and 10 are women. The average age was 41 years.

The first focus group was held on 2 July 2022 with residents of Colombia, their professions are sports coach, reporter, school teacher, doctor, sports journalist and graphic entertainer. The second, on 3 July 2022, with citizens living in Ecuador, their professions are two school teachers, a journalist, a provincial prefect, a sales manager and a news coordinator. The third virtual focus group took place on 7 July 2022 among citizens from Russia, Chile, Peru, Mexico, Venezuela and El Salvador who work as lawyers, sports journalists, psychologists, university teachers, audiovisual writers and TV producers. The coding of the testimonies is PC-#, PE-# and PO-# to identify the participants of the focus groups from Colombia, Ecuador and other countries, respectively.

From a theoretical perspective, a focus group is an interactive practice of social research (Callejo, 2001; Galeno, 2004). A focus group allows for the expression of different positions and attitudes of the participants, the exchange of information and the orientation of the discourse on the reality to be investigated (Canales and Peinado, 1995), on the other hand, “conducting focus groups online is logistically feasible. Social researchers currently have a series of technological and communicative resources that we can manage and configure to shape the group dynamics” (Parada, 2012, p. 112).

Six semi-structured interviews with experts were also conducted in November 2023 via email. The profiles of the experts correspond to three male and three female academics, specialists in digital communication, journalism and public opinion, working in Ibero-American universities. Interviews are recommended to obtain direct information from key people, and when we want to inquire about a subjective personal experience (Pedraz et al., 2014), “they will allow the qualitative and nuanced expression of the information obtained, serving both as a contrast, confirmation and triangulation of the information” (Sancho and Giró, 2013, p. 128). This technique is also used in studies that examine Russia’s strategic interests, objectives and tactics in Latin America (Farah and Ortiz, 2023).

3 Results

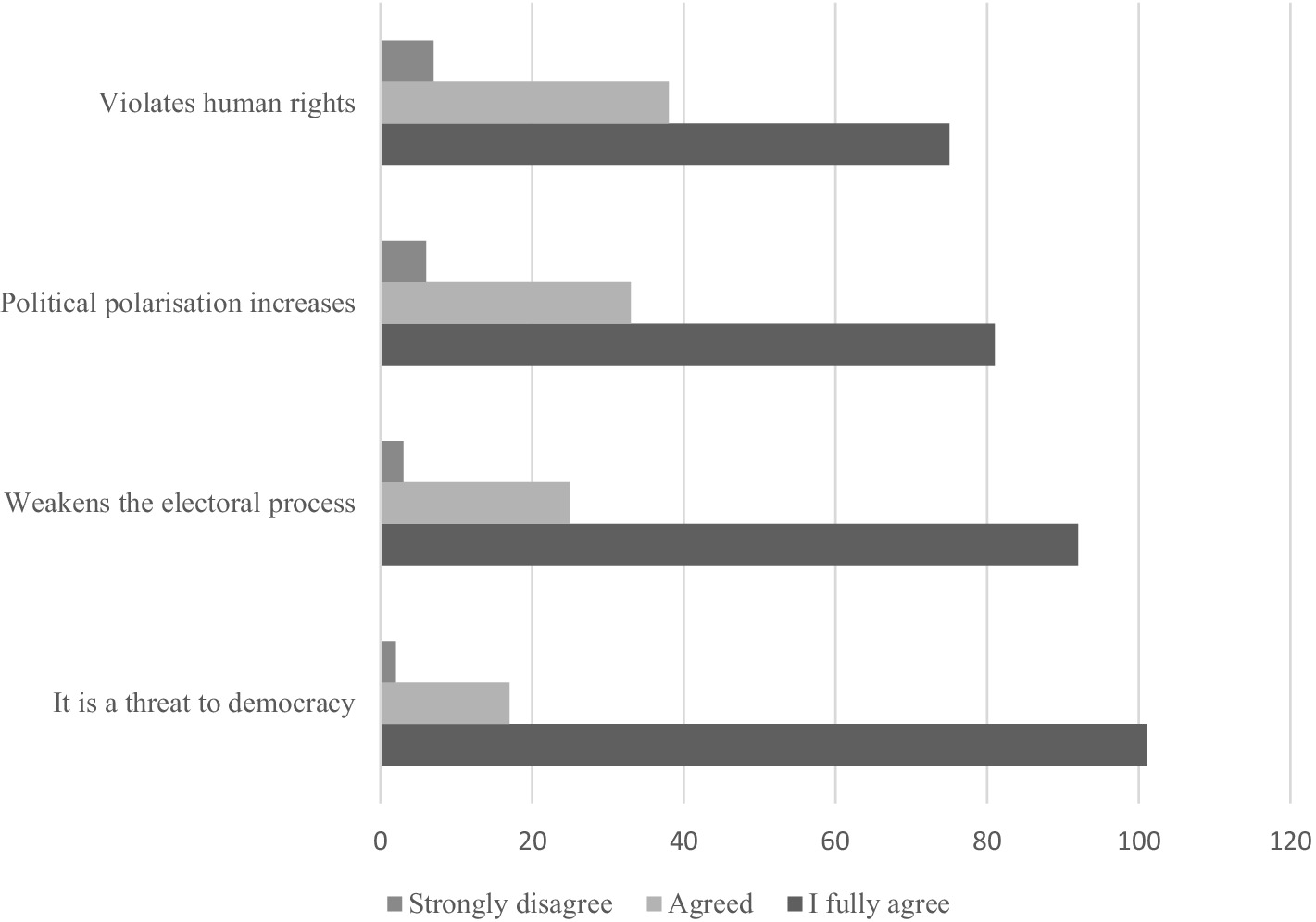

The results of the survey on the perception of disinformation among the citizens of the Andean Community, in quantitative and relevant part, are shown in Figures 1, 2. The greatest impact is seen in the effects on democracy and the obstruction of the electoral processes. 80% of those surveyed agree and recognize that disinformation distances people from adequate processes of representation and management through the system of political organization in democracy, and there is evidence of mistrust in elections, a mechanism for direct participation in democracy, which implies a warning for the governability of nations.

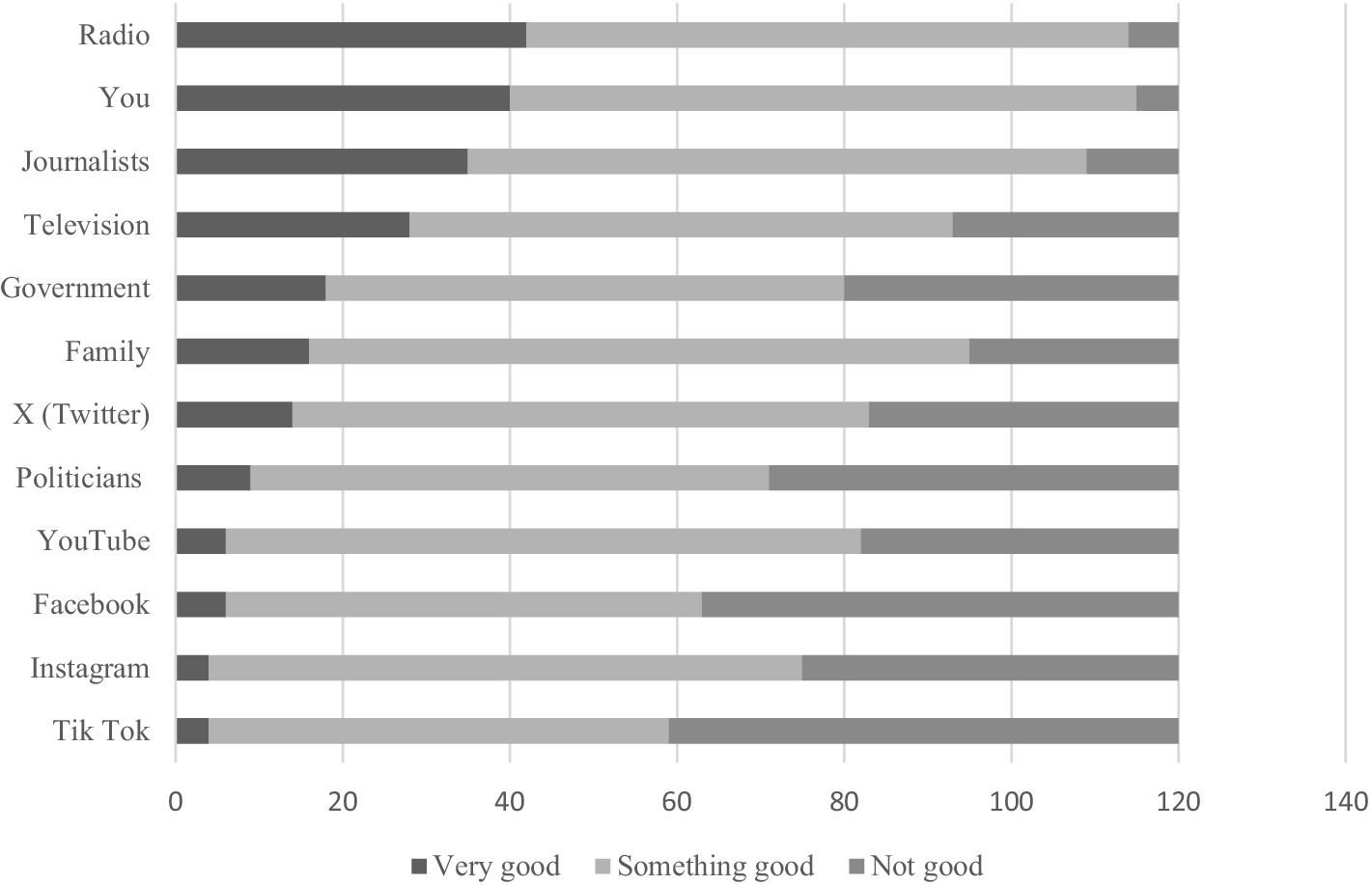

On the other hand, it is stands out that citizens trust the messages of the traditional media, qualifying them as issuers of authentic data, reports and coverage, far removed from disinformation. This categorization is valued as an expression of validation of the deontological practices of the media, and they also recognize social networks as generators of data and information that is not true or created to confuse, but this trust is opposed to the way of supplying information, where social networks are the biggest providers of news. Responses to the question “In the last week, what has been your main source of news? The concentration is on social networks 48% (X, Facebook, TikTok, Instagram); then traditional media with 38% (TV and news websites); and other 14%.

To the question “How often do you encounter news or information that you believe distorts reality or are false? 80% of the participants indicated that they encounter misinformation every day or at least once a week. The options “at least once a month,” and “rarely or never” accounted for 20% of responses.

Respondents’ answers to the consultation on the model of regulation that should govern disinformation indicate that a vision of state regulation persists. Of 120 responses, more than half, 53%, suggest that disinformation should be regulated by law, 28% by self-regulation and 19% by a co-regulatory model.

Regulation through laws is the model most accepted by respondents because they believe that the creation of a body, and therefore laws, is necessary to combat misinformation, as some media and social media platforms have spread incorrect news and misinformation that cause panic among citizens. That is why it is essential, for good communication to be regulated. States and governments have a responsibility to create laws that prevent misinformation. In addition, it is important to consider that there are people who do not have internet access or do not have the means access social networks, which is why they cannot verify or confirm the information they may receive.

Regulation would help to ensure that information reaches people correctly so that they can make informed decisions. Unfortunately, not all media assume this responsibility or misinformation is used for other purposes. It is pointed out that control and regulation of the media is necessary to ensure that they are complying with their obligations under the law and to protect them from groups that wish to impose their interests.

Regulating by law and imposing penalties on those who spread malicious content would make people think before misinforming the citizens. However, existing laws are not enforced. New constitutional alternatives must be explored to achieve good information. Regulations designed to combat disinformation should avoid affecting the quality of democracies and public safety. The purpose of regulating disinformation will be to ensure the exercise of the rights to communication, information and freedom of expression, and thus strengthen citizen participation.

In favor of self-regulation, it was mentioned that each media outlet must assume the committed to disseminate verified information in order to respond to and maintain the trust of its public. It is important for the media to have deontological codes that guide their work towards the search for truth, and indicate commitments and responsibilities that encourage them to be attentive in the face of eventualities.

For respondents, self-regulation also means that citizens must to be better informed and have the skills to recognize misinformation, make good use of social media so as not to confuse people with bad information. They also agree that platforms should stipulate news verification rules.

Ethical self-regulation of the industry is essential, but it must be well thought-out regulations designed to combat disinformation without undermining fundamental rights. This commitment would be assumed by every media and social media platform in a sensible and ethical manner, ensuring measures of truthfulness and quality of information.

Few respondents from the Andean Community mentioned their comfort with co-regulation because the regulation of misinformation is a complex challenge that requires a balance between freedom of expression and protection of the public. A hybrid approach is needed that combines the creation of laws and control bodies with the engagement of the media and social networks. A combination of regulation and individual engagement is needed. Laws and control bodies must be established, but it is also important that media and platforms take responsibility.

The combination of approaches involves, first of all, self-regulation and personal responsibility. Media and platforms must verify information. Journalists and content creators must meet ethical and professional standards to ensure accuracy and truthfulness. In addition, government regulations set minimum standards and penalties for disseminating false or misleading information. Independent control bodies can support in monitoring the quality of information.

It was stated that the laws guarantee substantiated information, both from companies and from the state. On the other hand, the regulation of social networks is being carried out by the platforms themselves, but there should be rules that regulate and sanction the broadcast of disinformation, that there should be filters so that publication is verified.

Self-regulation with regulatory measures could protect the integrity of information and support the right to truth and informed public participation. In addition to this, a strong commitment from the media and social networks is needed. Both aspects are important to effectively combat disinformation.

In the focus groups, several perspectives were identified on the knowledge and application of communication policies to combat disinformation and on their implementation and effectiveness. Firstly, it was mentioned that there are laws and regulations that seek to control and regulate information, and the proposals of international organizations such as UNESCO, which play a fundamental role in counteracting disinformation, were highlighted (PE-3; PC-3). Local initiatives are also mentioned, such as efforts by universities and ministries to educate children and adolescents, who are the main consumers of digital content, (PE-2). Despite these efforts, it is recognized that the level of media literacy is low and there is a need to promote media skills to discern and counteract false information (PE-1).

It was highlighted that globalization and the rise of social media exacerbate the spread of false information, and while there are laws and sanctions for formal media, little is done to control disinformation on digital platforms (PC-6). There are laws and codes that include sanctions for media outlets that disseminate false information (PE-5), but they are not sufficient to establish effective media literacy.

It is said that there are other countries, such as Venezuela, where the situation of disinformation is more critical, since the editorial line of the media is dictated by the government, which limits the exposure of the country’s realities and promotes disinformation (PO-5). In contrast, in El Salvador, other laws can be applied to control information, but the responsibility falls mainly on the professional ethics of journalists and media outlets (PO-6).

With regard to opinions on the relationship between education policies and the promotion of freedom of expression, the testimonies collected in the focus groups show conformity, with the majority of responses being in favor. It is argued that these freedoms are essential for a democratic society and should be promoted in education. For example, one response indicates that “when educating, the responsibility of using social networks should be pointed out” (PO-6). Another participant mentioned that it is fundamental to “educate people who can give their opinion with a criterion and not by repeating what they hear” (PO-1). Furthermore, it is suggested that these policies should be autonomous from governments to avoid the imposition of specific agendas or ideologies.

Empowering users in technologies through continuous learning and understanding of media functions is considered decisive. One response highlights that, while voluntary efforts currently exist, a comprehensive government program involving the media is needed to effectively educate the population and combat fake news. In addition, it is suggested that “information is power” (PC-2) and that understanding and controlling that power is essential for contemporary society.

On the other hand, some participants expressed that new policies are not required because laws already exist to support these freedoms, although they recognize the need for regulation to ensure that freedom of expression is not used irresponsibly. Others insist that it is imperative to modify current policies to ensure that everyone has access to media literacy, regardless of their level of education, and that the government should establish regulations that sanction the dissemination of false information. The opinions reflect a consensus on the importance of promoting freedom of expression and media literacy through education, with a focus on responsibility and appropriate regulation to prevent abuse of freedom.

The identification of regulatory authorities or organizations that combat disinformation is in the majority 15 out of 18 focus group participants indicated the correct names of the regulatory authorities in their respective countries. Although they did not give details of the functions they perform, they are clear about their purpose in promoting freedom of expression and related rights. Additionally, relationships with similar institutions in third countries were also outlined, such as “the National Literacy Trust which is an independent organization that focuses on working with schools and communities to deliver media and information literacy skills” (PC-6).

After carrying out the interviews, it is known that experts consider that social media platforms have the potential to take measures to prevent the spread of fake news by implementing mechanisms such as the use of artificial intelligence to detect and neutralize false information (Interviewee 2). Despite efforts to combat misinformation, the huge volume of fake content circulating online poses challenges to its timely identification and removal (Interviewee-1, Interviewee-2).

Platforms have a moral obligation to address fake news once detected, in addition to the legal responsibilities imposed by national and international frameworks. The implementation of warning campaigns and raising user awareness could help mitigate the impact of fake news on social media (Interviewee-2). However, platforms also face challenges due to the overwhelming amount of user-generated content, which can make the process of detection and removal difficult.

It was mentioned that “it is unacceptable for a platform to detect fake news and not intervene because it is interested in the traffic it generates” (Interviewee-2), in response to which “transparency in the algorithms used and the use of alternative recommendation and search criteria to avoid repressing the veracity and diversity of sources” (Interviewee-4) is recommended, as well as “detecting suspicious content and reducing its visibility or eliminating it from its platforms” (Interviewee-6).

It was expressed that some social networks already fight against disinformation “through financing verification platforms and media and information literacy programs. However, it is necessary to guarantee that these supports/measures are sufficiently independent” (Interviewee-5).

Other actions are the “(diligent) action to remove content in response to complaints, but also is ante monitoring of content with indications that may arouse suspicion, within the framework of co-regulation” (Interviewee-4) and the “integration of verifiers in content decision-making by platform moderators” (Interviewee-4). “I also consider that platforms could carry out warning and awareness-raising campaigns” (Interviewee-2) and “they can follow the example of many verification companies, which carry out media literacy work through their websites” (Interviewee-3). There are other measures such as “transparency in political advertising, promotion of reliable sources” (Interviewee-6).

Regarding state regulation and legislative measures to control disinformation, experts indicated that legislation to restrict the spread of disinformation should be considered because of its detrimental effects on democracies (Interviewee-6). While self-regulation can be effective in some cases, comprehensive solutions require government regulations and collaborative efforts to address the spread of fake news online while safeguarding freedom of expression and access to information. Cooperation between the media, content distribution platforms and the communications industry is seen as essential to combat disinformation.

Without neglecting the balance between freedom of expression and the fight against disinformation, care must be taken to enforce media codes of conduct and to uphold the vital role of journalists as reliable sources of information in society.

States “must pass laws that limit the spread of disinformation because of the damage it causes to democracies” (Interviewee-1) and because “it erodes everyone’s right to information” (Interviewee-2), and although difficulties persist in passing legislation and self-regulation “it is a global phenomenon that may require global measures” (Interviewee-5).

The concern remains to know “who would decide what is fake news, at least a debate should be started because the main problem is the impunity with which some media and journalists act, without respect for the truth” (Interviewee-2). “Laws should be established that make platforms more responsible when disseminating information” (Interviewee-3).

It was also specified that “it is difficult to respond to the legislative and legal issue because it depends on what form the disinformation takes (honor, privacy, moral integrity). In this sense, international institutions have insisted that there cannot be crimes of opinion” (Interviewee-2), which is why it is emphasized that

any new rules must ensure a balance between addressing disinformation and protecting freedom of expression and access to information. Effective solutions generally involve a multi-faceted approach involving governments, online platforms, media and civil society. Strategies must be adapted to country-specific circumstances and to the constant evolution of technology and online information. (Interviewee-6)

4 Discussion and conclusion

The article investigates how citizens in the Andean Community perceive the regulation of disinformation, based on hetero-, self- and co-regulation models. It presents the perspectives of communication system actors who agree that the regulation of disinformation is important to defend communication rights and democracy.

Recognizing the challenges and complexities associated with misinformation will allow governments and organizations to respond to the concerns expressed by audiences. Likewise, policymakers can use the knowledge provided in this study to design comprehensive regulatory frameworks that take into account the diverse views and preferences of people in the Andean region.

The research achieved its objectives by analyzing the problem of misinformation and the need for adequate regulation. It found that combating disinformation is a contemporary and urgent issue that requires a balance between the promotion of human rights and freedom of expression.

Respondents were in favor of state regulation to combat misinformation, emphasizing the need for governments to enact laws to prevent the spread of false information, and they consider that the application of legislative measures is necessary to stop the harmful effects of misinformation in democracies. 80% indicated that they received misinformation daily or at least once a week, highlighting the pervasive nature of misinformation in society. It was also revealed that 48% of people relied primarily on social media for news, followed by traditional media at 38% and other sources at 14%.

Combating disinformation is a contemporary and urgent issue. Any regulatory model that is implemented must promote human rights and respect freedom of expression. Human rights must be protected, guaranteeing the right to disseminate information and ideas, even those that may be shocking or disturbing. Regulation must respect human rights (UNESCO, 2023) and must not restrict expressions of irony, satire, parody or humor on the grounds of disinformation because “it implies the risk of suppressing artistic, scientific and journalistic work and public debate in general” (UN, 2022).

The human right to “disseminate information and ideas is not limited to “correct” statements, but the right also protects information and ideas that may shock, offend and disturb” (United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Representative on Freedom of the Media, The Organization of American States Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information, 2017). In this sense, Latin American states “should not establish new criminal offences to punish the dissemination of disinformation [...] which, due to the nature of the phenomenon, would be vague or ambiguous, and could take the region back to a logic of criminalizing expressions” (OAS, 2019).

Regarding self-regulation, the importance of media compliance with ethical codes and responsibilities to guarantee the dissemination of accurate information and maintain public trust was noted. The research highlights that co-regulation, involving governments, social media platforms and civil society, is a viable option. It is considered as a middle way between state regulation and media self-regulation, mitigating risks derived from corporate wills and political conjunctures.

There was consensus on the need to adopt a hybrid approach to combat disinformation, combining regulatory measures with individual engagement and media responsibility. Collaboration between the media, online platforms and communication industries is essential in the fight against disinformation. An effective approach to combating disinformation involves a multi-faceted strategy adapted to each country’s circumstances and the evolving technological landscape.

Another relevant aspect that was shown from the focus groups is the urgency of making social media screening algorithms transparent, diligent content moderation and the integration of fact-checkers into platforms’ content decisions about content are recommended measures to combat misinformation. Legislation should be considered to make platforms more accountable for the information they disseminate, striking a balance between addressing disinformation and protecting freedom of expression. Digital platforms must assume responsibility for the dissemination of information. There should be rules that regulate and sanction the dissemination of disinformation, with filters to verify publications before they are disseminated.

Faced with legislation, it is striking that some governments are turning to social and educational strategies (Media Defense, 2023). In this direction, in the focus groups, participants stressed the importance of equipping people with the necessary skills to discern and counter misinformation, advocating for greater media literacy and responsible use of social networks. Empowering people with media literacy skills and promoting responsible use of social media is vital to counter the spread of false information.

Campaigns to raise awareness among users and quickly remove fake news on platforms can help mitigate the impact of misinformation on social media. Media literacy was identified as key to countering disinformation. Educational efforts should be strengthened to enable the population to discern and counter false information. It is suggested that both the government and the media work together in this task. A constructive and well-informed dialogue is called for to defend democratic values and the integrity of information (Souza and Andrade, 2023). In the face of misinformation, the democratic conversation must be empowered (Andersen and Søe, 2020).

Co-regulation is an option through measures that involve the main actors in media systems; governments, social media platforms and civil society, to consider their perspectives with a preventive approach. In the results of the research show that co-regulation is seen as a middle way between state regulation and self-regulation of the media, where there are still risks derived from the will of the companies and political situations.

International bodies, such as the European Commission, have opted to continue with co-regulation “through a voluntary mechanism, instead of approving new binding rules that could lead to an excessive elimination of content” (Colomina and Pérez-Soler, 2022, p. 151). But the role of states is also recalled, as they “cannot be inert spectators in the face of the erosion of democracy” (Brant, 2022). States “are primarily responsible for countering disinformation by respecting, protecting and fulfilling the rights to freedom of opinion and expression, privacy and public participation” (UN, 2022, p. 20).

To strengthen the fight against disinformation, both regulatory and civic participation initiatives must be articulated across countries, otherwise “they are doomed to fail. Information disruption is by definition a global problem, so our reflections must take place at a global level” (Azoulay, 2023), one option is to promote a global forum to guarantee that new regulations and standards go hand in hand, between countries (Colomina et al., 2021).

Future lines of research are to evaluate the effectiveness of legislative measures and co-regulatory initiatives to combat misinformation, identifying areas for improvement. Another way is to study the impact of media literacy programs aimed at the general population to identify and mitigate the spread of misinformation. Or extend this study to other Latin American countries, and compare with nations in other continents, and qualitative analysis. Another option is sociological interpretations of the preferences of hetero-regulation in Andean countries, why do they need third parties or an external instance to respect the integrity and veracity of messages? When it is assumed the highest ideal of communication is the promotion of people and the defense of the human right to freedom of expression.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research on Human Beings—Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (CEISH399 UTPL), dated 16th September 2021. The study was conducted in accordance with all institutional and national legislation and requirements. The participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study and for the publication of any identifying information included in the article. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The author declares to have received financial support from the Vicerrectorado de Investigación de la Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja, Ecuador, for the research and publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andersen, J., and Søe, O. (2020). Communicative actions we live by: the problem with factchecking, tagging or flagging fake news - the case of Facebook. Eur. J. Commun. 35, 126–139. doi: 10.1177/0267323119894489

APM (2019). Informe anual de la profesión periodística [annual report on the journalistic profesión]. Madrid, Spain: Asociación de prensa de Madrid.

Azoulay, A. (2023). Para evitar la desinformación, se necesita regular las plataformas digitales [To avoid misinformation, digital platforms need to be regulated]. Available at: https://news.un.org/es/story/2023/02/1518832 (Accessed May 31, 2024)

Bayer, J., Bitiukova, N., Bárd, P., Szakács, J., Alemanno, A., and Uszkiewic, E. (2019). Disinformation and propaganda – Impact on the functioning of the rule of law in the EU and its member states. Brussels: European Union.

Becerra, M., and Waisbord, S. (2021). La necesidad de repensar la ortodoxia de la Libertad de expresión en la comunicación digital [the need to rethink the orthodoxy of freedom of expression in digital communication]. Revist Ciencias Soc. 60, 295–313.

Botero, C. (2017). La regulación estatal de las llamadas “noticias falsas” desde la perspectiva del derecho a la libertad de expresión[State regulation of so-called “fake news” from the perspective of the right to freedom of expresión]. En Varios. Libertad de expresión: A 30 años de la opinión consultiva sobre la colegiación obligatoria de periodistas. Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos.

Brant, J. (2022). Regulación para combatir la desinformación [Regulation to combat disinformation]. Ciclos de Actualización para Periodistas (CAP). Available at: https://cicloscap.com/regulacion-democratica-contra-la-desinformacion/ (Accessed May 31, 2024).

Brant, J., Bastos, J., Dourad, T., and Pita, M. (2020). Regulación para combatir la desinformación. Estudio de ocho casos internacionales y recomendaciones para un enfoque democrático [Regulation to combat disinformation. Study of eight international cases and recommendations for a democratic approach]. Bogotá, Colombia: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Callejo, J. (2001). El grupo de discusión: Introducción a una práctica de investigación [The focus group: Introduction to a research practice]. Ariel.

CAN (2024). Who are we?. Available at: https://www.comunidadandina.org/quienes-somos/ (Accessed June 17, 2024).

Canales, M., and Peinado, A. (1995). “Grupos de discusión. Métodos y técnicas cualitativas de investigación en ciencias sociales [Focus groups. Qualitative social science research methods and techniques.]” in Métodos y técnicas cualitativas de investigación en ciencias sociales [Qualitative social science research methods and techniques.]. eds. J. Y. Delgado and J. Gutiérrez (Madrid, Spain: Síntesis), 288–311.

Cerdà-Navarro, A., Abril-Hervás, D., Mut Amengual, B., and ComasForgas, R. (2021). Fake o no fake, esa es la cuestión: reconocimiento de la desinformación entre alumnado universitario [fake or not fake, that is the question: recognition of misinformation among university students]. Revista Prisma Soc. 34, 298–320.

Chorro, L. (2020) Estadística aplicada a la psicología [statistics applied to psychology]. Available at: https://www.uv.es/webgid/Descriptiva/331_mtodos.html (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Colomina, C., and Pérez-Soler, S. (2022). Desorden informativo en la UE: construyendo una respuesta normativa [information disorder in the EU: building a regulatory response]. Revista CIDOB Afers Internacionals 13, 141–161. doi: 10.24241/rcai.2022.131.2.141

Colomina, C., Sánchez, H., and Youngs, R. (2021). The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights in the world. Policy Department for External Relations Directorate General for external policies of the union PE 653.635. European Parliament

Creswell, J. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. California, United States of America: Sage.

Del-Fresno-García, M. (2019). Desórdenes informativos: Sobreexpuestos e infrainformados en la era de la posverdad [information disorder: overexposed and underinformed in the post-truth era]. El Profesional Inform. 28, 1–11. doi: 10.3145/epi.2019.may.02

Dinegro, A. (2022). El desafío de regular las plataformas en Perú [the challenge of regulating platforms in Peru]. Lima, Perú: Fundación Friedrich Ebert-Perú.

Espaliú-Berdud, C. (2023). Use of disinformation as a weapon in contemporary international relations: accountability for Russian actions against states and international organizations. Profesional Inform. 32:e320402. doi: 10.3145/epi.2023.jul.02

European Commission (2018a). Fake news and disinformation online, publications Office of the European Union. Available at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759/559993 (Accessed June 5, 2024).

European Commission (2018b). Combatir la desinformación en línea: La Comisión propone un Código de Buenas Prácticas para toda la UE. IP/18/3370. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-3370_es.htm (Accessed June 5, 2024).

European Commission (2018c). Action plan against disinformation. EEAS. European External Action Service. European Union.

European Court of Human Rights (1976). Case of Handyside vs. The United Kingdom. Judgment. Strasbourg. Available at: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-57499 (Accessed June 5, 2024).

Farah, D., and Ortiz, R. (2023). Russian influence campaigns in Latin America. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

Fraguas de Pablo, M. (2016). La desinformación en la sociedad actual [Disinformation in today's society]. Cuadernos Info 3, 23–32. doi: 10.7764/cdi.3.887

Galarza, R. (2022). Impacto de la desafección política de la ciudadanía en México [The impact of political disaffection of citizens in Mexico]. Sphera Publica 1, 56–80.

Galeno, M. (2004). Estrategias de investigación social cualitativa: el giro en la mirada [qualitative social research strategies: The turn in the gaze]. 1st Edn. Medellín, Colombia: La Carreta.

González, R. (2022). “Ciudadanía y alfabetización digital en tiempos de desinformación – desafíos más allá de la pandemia [Citizenship and digital literacy in times of disinformation - challenges beyond the pandemic]” in Navegando en la Infodemnia con AMI. eds. F. En Chibás and S. Novomisky (Paris, France: UNESCO).

Haciyakupoglu, G., Hui, J., Suguna, V., Leong, D., and Rahman, M. (2018). Countering fake news. A survey of recent global initiatives. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University.

Hanley, M. (2020). Salvaguardar el espacio informativo: las políticas de la UE y Ucrania ante la desinformación [safeguarding the information space: EU and Ukraine policies in the face of disinformation]. Revista CIDOB Afers Internacionals 124, 73–98. doi: 10.24241/rcai.2020.124.1.73

Hernández-Sampieri, R., Fernández-Collado, C., and Baptista-Lucio, P. (2014). Metodología de la Investigación [Investigation methodology]. México: McGraw-Hill.

IACHR (1985). Opinión consultiva oc-5/85 del 13 de noviembre de 1985 [advisory opinion oc-5/85 of November 13, 1985]. Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Available online at: https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/opiniones/seriea_05_esp.pdf (Accessed June 4, 2024).

Internet Society (2024). Informes nacionales [national reports]. Available at: https://pulse.internetsociety.org/es/reports (Accessed June 17, 2024).

Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of lies. Data & Society Research Institute. Available at: https://datasociety.net/library/lexicon-of-lies/ (Accessed April 10, 2024).

Jornet, C. (2020). Once leyes y proyectos de ley contra la desinformación en América Latina implican multas, cárcel y censura [eleven laws and bills against disinformation in Latin America involve fines, jail and censorship]. LatAm Journalism Review. Available at: https://latamjournalismreview.org/es/articles/leyes-contra-desinformacion-america-latina/ (Accessed April 10, 2024).

Kaye, D. (2016). Promoción y protección del derecho a la libertad de opinión y de expresión [Promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expresión]. Nota del Secretario General. Naciones Unidas. Available at: https://www.acnur.org/fileadmin/Documentos/BDL/2017/10876.pdf (Accessed April 10, 2024).

Lim, G., and Bradshaw, S. (2023). Legislación escalofriante: seguimiento del impacto de las leyes sobre “noticias falsas” en la Libertad de prensa a nivel internacional [chilling legislation: tracking the impact of “fake news” laws on international press freedom]. Center for International Media Assistance National Endowment for Democracy. Available at: https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/chilling-legislation/ (Accessed April 10, 2024).

Magallón-Rosa, R. (2019). La (no) regulación de la desinformación en la Unión Europea. Una perspectiva comparada [The (non)regulation of disinformation in the European Union. A comparative perspective]. UNED. Revista Derecho Político 106, 319–347.

Magallón-Rosa, R. (2023). Desinformación y democracia [Disinformation and democracy]. Telos Available at: https://telos.fundaciontelefonica.com/desinformacion-y-democracia/ (Accessed April 12, 2024).

Marcos, J., Sánchez, J., and Olivera, M. (2017). La enorme mentira y la gran verdad de la información en tiempos de la postverdad [the big lie and the big truth of information in the post-truth era]. Scire 23, 13–23. doi: 10.54886/scire.v1i2.4446

Masip, P., and Ferrer, A. (2021). Más allá de las fake news. Anatomía de la desinformación [Beyond fake news. Anatomy of misinformation]. BiD: textos universitaris de biblioteconomia i documentació 46, 1–6. doi: 10.1344/BiD2020.46.08

Media Defense (2023). ¿son las leyes sobre noticias falsas la mejor manera de enfrentar la desinformación? [are fake news laws the best way to tackle misinformation?]. Available at: https://www.mediadefence.org/news/noticias-falsas/ (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Mihailidis, P., and Viotty, S. (2017). Spreadable spectacle in digital culture: civic expression, fake news, and the role of Media literacies in “post-fact” society. Am. Behav. Sci. 61, 441–454. doi: 10.1177/0002764217701217

Mosto, C., Corrallini, F., and Mosto, A. (2020). ¿Cómo se informan los argentinos? [how do argentines get informed?]. FOPEA y Thomson Media. Available at: https://fopea.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/FOPEA-Guias-Como-se-informan-los-argentinos.pdf (Accessed April 12, 2024).

Newman, N. (2019). Resumen ejecutivo y hallazgos clave del informe de 2019. Informe de noticias digitales [executive summary and key findings from the 2019 report]. Digital news Report

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Schulz, A., Andi, S., and Nielsen, R. K. (2020). Reuters institute digital news report 2020. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism

OAS (2000). Antecedentes e interpretación de la declaración de principios [Background and interpretation of the declaration of principles]. Relatoría Especial para la Libertad de expresión de la CIDH. Available at: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/expresion/showarticle.asp?artID=132&lID=2 (Accessed April 20, 2024).

OAS (2009). Marco jurídico interamericano sobre el derecho a la Libertad de expresión [inter-american legal framework on the right to freedom of expression]. Washington, United States of America: CIDH/RELE/INF.

OAS (2027). Declaración conjunta sobre Libertad de expresión y "noticias falsas" ("fake news"), desinformación y propaganda [joint declaration on freedom of expression and "fake news", disinformation and propaganda]. Relatoría Especial para la libertad de expresión de la OEA. Available at: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/expresion/showarticle.asp?artID=1056&lID=2 (Accessed April 20, 2024).

OAS (2019). Guía para garantizar la libertad de expresión frente a la desinformación deliberada en contextos electorales [guidance on ensuring freedom of expression in the face of deliberate disinformation in electoral contexts]. OEA, CIDH, RELE. Available at: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/expresion/publicaciones/Guia_Desinformacion_VF.pdf (Accessed April 30, 2024).

Olmo-y-Romero, J. (2019). Desinformación: concepto y perspectivas [Disinformation: concept and perspectives]. Real Instituto Elcano, ARI 41/2019.

Parada, F. (2012). Premisas y experiencias: análisis de la ejecución de los grupos de discusión online [Premises and experiences: analysis of the implementation of online focus groups]. Encrucijadas 4, 95–114.

Pauner, C. (2018). Noticias falsas y Libertad de expresión e información: el control de los contenidos informativos en la red [fake news and freedom of expression and information: the control of news content on the web]. Teoría Realidad Constitucional 41, 297–318. doi: 10.5944/trc.41.2018.22123

Pedraz, A., Zarco, J., Ramasco, M., and Palmar, A. (2014). Investigación cualitativa [Qualitative research]. 1st Edn. Madrid, Spain: Elsevier.

Perelló, B. (2024). Desde Francia hasta Turquía: así se ha legislado contra los bulos y la desinformación en otros países [from France to Türkiye: this is how other countries have legislated against hoaxes and misinformation]. Newtral. Available at: https://www.newtral.es/legislacion-desinformacion/20240501/ (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Persily, N. (2017). Can democracy survive the internet? J. Democr. 28, 63–76. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0025

Rauls, L. (2021). How Latin American governments are fighting fake news. Americas Quaterly. Available at: https://americasquarterly.org/article/how-latin-american-governments-are-fighting-fake-news/ (Accessed April 1, 2024).

Ressa, M. (2023). Para evitar la desinformación, se necesita regular las plataformas digitales [to avoid misinformation, digital platforms need to be regulated]. Noticias ONU. Available at: https://news.un.org/es/story/2023/02/1518832 (Accessed April 1, 2024).

Roberts, R. (2022). Regulación de las "fake news" en el derecho comparado. Asesoría técnica parlamentaria [regulation of "fake news" in comparative law. Parliamentary technical advice]. Informe N° SUP: 128414. Santiago, Chile: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile.

Rodrigo-Alsina, M., and Cerqueira, L. (2019). Periodismo, ética y posverdad [journalism, ethics and post-truth]. Cuadernos. Info 44, 225–239. doi: 10.7764/cdi.44.1418

Rodríguez, R. (2018). Fundamentos del concepto de desinformación Como práctica manipuladora de la comunicación política y las relaciones internacionales [basics of the concept of disinformation as a manipulative practice in political communication and international relations]. Historia Comunicación Social 23, 231–244. doi: 10.5209/HICS.59843

Salazar, G. (2022). Más allá de la violencia: alianzas y resistencias de la prensa local mexicana [Beyond violence: alliances and resistance in Mexico's local press]. Ciudad de México, México CIDE.

Sánchez, O. (2020). La regulación de las campañas electorales en la era digital. Desinformación y microsegmentación en las redes sociales con fines electorales [The regulation of electoral campaigns in the digital age. Disinformation and microsegmentation on social networks for electoral purposes]. Valladolid, Spain: Universidad de Valladolid. Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales.

Sancho, M., and Giró, X. (2013). Creando redes, estableciendo sinergias: la contribución de la investigación a la educación [creating networks, establishing synergies: The contribution of research to education]. I Simposio internacional REUNI+D. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona.

Sandoval, C. (2002). Investigación Cualitativa. Programa de especialización en teoría, métodos y técnicas de investigación social [qualitative research. Specialization program in theory, methods and techniques of social research]. Bogotá, Colombia: Arfo Editores.

Sartori, G. (2016). Homo videns. La sociedad teledirigida [Homo videns. The remote-controlled society]. Debolsillo.

Slipczuk, M. (2023) Desinformación: los riesgos de las leyes anti “fake news” [disinformation: the risks of anti-fake news laws]. Available at: https://chequeado.com/nota/desinformacion-los-riesgos-de-las-leyes-anti-fake-news/ (Accessed March 19, 2024).

Souza, S., and Andrade, M. (2023). Regulación y libertad de expresión en la era de las noticias falsas: desafíos democráticos [Regulation and freedom of expression in the era of fake news: democratic challenges]. Revista Foco. 16, 01–25. doi: 10.54751/revistafoco.v16n10-185

Taylor, J., and Bodgan, R. (1984). Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación. La búsqueda de significados [Introduction to qualitative research methods. The search for meanings]. Barcelona, Spain: Paidos Ibérica S.A.

UN (2022). Contrarrestar la desinformación para promover y proteger los derechos humanos y las libertades fundamentales [Countering misinformation to promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms]. Informe del Secretario General Septuagésimo séptimo período de sesiones. ONU.

UNESCO . (2021). Aspectos destacados de “el periodismo es un bien común: Tendencias mundiales en Libertad de expresión y desarrollo de los medios. Informe mundial 2021/2022” [highlights from "journalism is a common good: global trends in freedom of expression and Media development. World report 2021/2022"]. UNESCO

UNESCO . (2023). Salvaguardar la libertad de expresión y el acceso a la información: directrices para un enfoque de múltiples partes interesadas en el contexto de la regulación de las plataformas digitales [Safeguarding freedom of expression and access to information: guidelines for a multi-stakeholder approach in the context of digital platform regulation]. UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000384031_spa (Accessed March 19, 2024).

United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Representative on Freedom of the Media, The Organization of American States Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information . (2017). Joint declaration on freedom of expression and fake news, disinformation and propaganda [joint declaration on freedom of expression and fake news, disinformation and propaganda]. Available online at: https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/6/8/302796.pdf (Accessed March 25, 2024).

Vosoughi, T., Deb, R., and Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science 359, 1146–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.aap9559

Wilson, C., Grizzle, A., Tauzon, R., Akyempong, K., and Cheung, C. K. (2011). Media and information literacy curriculum for teachers. París, France: UNESCO.

World Economic Forum (2024): Global risks 2024: disinformation tops global risks 2024 as environmental threats intensify. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/press/2024/01/global-risks-report-2024-press-release/ (Accessed March 2, 2024).

Zelaya, M. (2022). Los Tiempos, Bolivia. In S. Levoyer and P Escandón. (2023). Informe de investigación. “Desinformación y políticas públicas en la región Andina” y “Desinformación y transmedia: el rol de los medialabs universitarios en la región” [Investigation report. “Disinformation and public policies in the Andean region” and “Disinformation and transmedia: the role of university medialabs in the region”]. Quito, Ecuador: Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar sede Ecuador, Comité de Investigaciones.

Keywords: disinformation, news, media consumption, media literacy, media competition, regulation, self-regulation

Citation: Suing A (2024) Perceptions of disinformation regulation in the Andean community. Front. Commun. 9:1457480. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1457480

Edited by:

José Sixto-García, University of Santiago de Compostela, SpainReviewed by:

Mariano Mancuso, University of Buenos Aires, ArgentinaPablo Escandón, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Ecuador

Copyright © 2024 Suing. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abel Suing, YXJzdWluZ0B1dHBsLmVkdS5lYw==

Abel Suing

Abel Suing