- 1School of Journalism and Information Communication, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

- 2School of Journalism and Communication, Northwest University, Xi'an, China

Emoticons are non-verbal symbols that are employed during online interactions, and they constitute an integral component of online interpersonal communication. The influence of emoticons on the online interpersonal interactions of young people was investigated through in-depth interviews with 25 young people who utilize emoticons to a moderate or significant extent. The study identified three key aspects through which the impact of emoticons on youth’s online social interactions is manifested. Firstly, this is reflected in the level of emotion and meaning conveyed. The utilization of emoticons by young people has, to a certain extent, rectified the contextual limitation of “embodied absence” in online virtual social interaction. Secondly, this is reflected in young people’s recognition of emoticons. The use of emoticons by young people in online social interactions has led to the formation of a distinct “emoticon community.” This phenomenon not only facilitates the development of a more profound social identity among young people in online social interactions but also contributes to the expansion of the adolescent network, resulting in the emergence of a novel “social divide.” Thirdly, the use of emoticons by young people can be seen to contribute to a sense of alienation. As young people become increasingly reliant on emoticons, their influence is gradually extending from the digital realm to the physical world, impacting the normal social interactions of young people in real life. Emoticons have gradually become a means of facilitating young people’s online socialization, but they have also had the unintended consequence of limiting their normal social interaction. The deterioration of online interpersonal communication among young people is a key factor in the symbolic generalization and alienation of expression in the use of emoticons by this demographic.

Introduction

Interpersonal communication refers to the exchange of information between people, which can occur through direct face-to-face interaction or indirect interaction using media. Both the form and content of communication reflect the characteristics of individuals, as well as their social roles and relationships (Hartley, 1993, p. 19). Interpersonal interaction is important for personal socialization in which individuals engage in social interactions, exchange meanings, and appropriate or use social resources. Interpersonal interactions are a fundamental aspect of human social behaviour, facilitating the formation and maintenance of relationships. These interactions typically entail close communication between individuals (Knapp et al., 1994), and serve as a crucial avenue for assessing both cognitive abilities (IQ) and emotional intelligence (Guo et al., 2024). Non-verbal symbols, such as eye contact, body contact, gesture interaction, and matching clothing, which are based on face-to-face interactions, play an important role in how information is interpreted, meaning is coordinated, and emotions are engaged (Rahmalina and Gunawan, 2024). Information is a fundamental element of human social interaction, and different messages form “information chains” (Mei et al., 2004) that enter social situations through media, while verbal and non-verbal symbols are two forms of information conveyed in interpersonal communication. Although language is the most common and widespread way to communicate with people, interpersonal communication involves not only having to “listen to their words” but also to “observe their actions.” Non-verbal symbols such as facial expressions, eyes, tone of voice, body movements, and physical contact still play an essential role in interpersonal communication.

The verbal and non-verbal components of face-to-face communication are situated within their own contexts and settings. Non-verbal communication is characterized by its capacity to stimulate and orientate the senses (Shokrollahi, 2014). It also fulfils a coordinating role in supporting language for communication, and in facilitating the exchange of meaning and the construction of identity in interpersonal interactions (Chitac et al., 2024). Non-verbal communication can complement the lack of information and meaning caused by verbal signs and facilitate the exchange of meaning in interpersonal interactions (Stevenson, 1999). The spatial and extended nature of non-verbal signs can, however, create tension in the socially charged acts of interpersonal communication. This tension is due in part to the ambiguity of the meaning of non-verbal signs, which convey attitudes and emotions in a variety of ways, in addition to complementing interpersonal communication and making it easy for people to disagree with each other (Frențiu, 2019).

Network interpersonal interaction is a continuation and development of traditional interpersonal interaction that takes place in cyberspace. This form of interaction has, to a certain extent, broken down the barriers of time and space that limited traditional interpersonal interactions (Kornfield et al., 2021). The technological characteristics of cyberspace have imposed new features and required chances in online interpersonal interactions. These features and changes are gradually reconfiguring human interactions through the deep integration of the Internet with human society, which has created the conditions for the presentation of people’s virtual selves (Nadia et al., 2019). Online interaction based on social media reflects, to a certain extent, the mainstream of online interpersonal interactions, and the tendency it shows to return to traditional approaches to interpersonal interaction also expresses people’s desire for authentic communication. People use online communication to access information, engage in mediated information production (Zhen et al., 2015), collaborate, and build relationships. Online interpersonal communication is of great value to people in building social relationships and maintaining relationships (Temel Eginli and Ozmelek Tas, 2018).

Prior to the advent of emoticons, emoji played a significant role in online interpersonal communication. The initial network interpersonal interaction is based solely on textual communication within the virtual space. The absence of non-verbal and verbal symbols results in a significant increase in the uncertainty of information transmission during network interpersonal interaction. The de-contextualized nature of textual communication in network interpersonal communication makes it challenging to achieve meaningful exchange. This predicament of online interpersonal communication also makes emoji, as an important link to compensate for the lack of embodiment in online interpersonal communication, a virtual extension of the value of nonverbal symbols in interpersonal communication, and an important factor in enhancing the depth of online interpersonal interactions and emotions (Lin et al., 2024). Emojis are typically composed of simple characters, graphics, or icons, characterized by a straightforward structure and ingenious design. They are pervasively employed in online human interaction scenarios to convey emotions, attitudes, or specific information. It has been proposed that emoticon messages serve to complement, rather than replace, non-verbal messages in communication (Tandyonomanu, 2018). This addition serves as a significant remedy to the absence of “strong” and “weak relationships” (Granovetter, 1973) in social interactions online. It has been proposed that emojis function as a conduit for meaning exchange, with the significance of the conveyed meaning contingent upon the context of the embedded message (Fischer and Herbert, 2021). Furthermore, emoji have been employed in museum virtual reality (VR) interactions, demonstrating an ability to enhance enjoyment and efficiency (Shen et al., 2024). Nevertheless, some studies have indicated that, despite the usefulness of emoji in clarifying intentions and reducing uncertainty, ambiguity remains with regard to their use and interpretation (de and Bakhshi, 2024). The use of simple emoji allows individuals to express their emotions and attitudes in a more effective manner within digital communication, thereby enhancing the efficiency and enjoyment of communication. However, the inherent ideographic ambiguity of emoji presents a challenge to the effectiveness of communication. This has led to the emergence of a demand for the development of a more sophisticated non-verbal symbol that can overcome the limitations of emoji.

The advent of emoticons represents a further evolution of the emoji concept, offering a novel means of non-verbal communication within the context of online interpersonal interactions. In essence, emoticons and traditional emoji symbols are comparable in terms of their capacity to convey emotion and meaning. However, emoticons possess a greater degree of nuance, a lower barrier to creation, and other distinctive characteristics that have facilitated their rapid social and entertainment uptake. The appeal of emoticons is widely observed and sought after by young people. The advent of emoticon packets has enhanced the quality of online interpersonal interactions. Their capacity to entertain, engage, and involve users has also facilitated their rapid adoption among younger demographics (Chen and Siu, 2016). One study (Saramandi et al., 2024) proposes that tactile emoticon pairs can effectively enhance the emotional communication of anxious participants in online interpersonal interactions, thereby further validating the interactive and participatory nature of emoticons and enhancing the use of emoticons in online interpersonal interactions. Emoticons, which are presented visually in virtualized social communication contexts (Mezgár, 2009), serve to enhance the recogniability of interpersonal relationships and facilitate the formation of new relationships. The research suggests that the utilization of emoticons in online interpersonal communication is subject to contextual bias. The use of emoticons is subject to contextual constraints. In public spaces, positive emoticons are employed, whereas negative emoticons are used in private spaces. Furthermore, more intense emoticons are reserved for use in intimate contexts (Cherbonnier et al., 2024). These symbols manifest in the form of images, emoticons, and motion pictures, thereby becoming a significant conduit for conveying meaning, expressing emotions, and fostering and sustaining relationships (Thelwall and Wilkinson, 2009) among young people in the digital realm. The use of non-verbal emoticons serves to compensate for the absence of virtual social situations, thereby influencing the nature of online interaction.

It is worth noting that, as a form of digital self-expression (Blum-Ross and Livingstone, 2017), non-verbal symbols, and notably emoticons, have shifted from a supporting to a leading role in young people’s online interpersonal interactions. Although initially they assisted in communication (Lo, 2008) and contextual construction, current emoticon socialization and interaction has a broader meaning. The trend toward their centralization is also becoming increasingly apparent. News images, film and television characters, and real-life scenes can all be used to create emoticon packs. The fact that “everything can be an emoticon” is part of the “collective memory” (Weedon and Jordan, 2012) of online communication. Emotional attachment has also overtaken auxiliary expression as the primary function of emoticons in online communication. Among young people, emotional expression and cross-cultural exchange are carried through emoticons in a virtually constructed “hyper-real” environment. The chain of emoticon creation, consumption, and interaction through mediated community interaction (Thorns and Eryilmaz, 2014) has also distorted the meaning and value of non-verbal symbols for communication. Fighting with emoticons and symbolic socialization derived from emoticons have rapidly overturned traditional interpersonal interactions. While emotions are conveyed more fully and information is exchanged more conveniently with emoticons, there are also real problems such as cultural compartmentalization and symbolic social dependence that hurt the psychological healthy growth of youth. These new issues have not been addressed in previous studies on online interpersonal interaction and youth socialization, while studies on emoticons have not supported or explained the changes in online interpersonal interaction brought about by emoticons.

In consideration of the previous discussion, several questions emerge regarding the role and function of emoticons in youth’s online interpersonal communication. This study aims to investigate the impact of young people’s reliance on emoticons in online interpersonal communication on their communication and interaction. In order to gain insight into these questions, we analyse the impact of young people’s use of emoticons on their online social interactions. This allows us to further clarify how the use of online non-verbal symbols affects young people’s development and social values.

Methods

Aims

This qualitative study investigates the variable effects of emoticon use and dependence on youth’s’ online and everyday social life, including social behavior, language, relationships, and networks. More specifically, this study sought to determine what effects the use of emoticons has on youth’s’ online social interactions, whether these effects are positive or negative, and how these effects interact with real social interactions.

Participants and procedure

To maximize first-hand information on youth emoticon use, the researcher started collecting data from a core of her friends. As the researcher herself is part of the target study demographic, she has many friends her age who are heavy users of emoticons. The initial participants were therefore drawn as a convenience sample from the researcher’s social circle and friends. This decision was made because it was not possible to ascertain which individuals relied on emoticons for online socialization at the outset of the study. Instead, this could only be determined by observing the use of emoticons in the researcher’s own online social circles. The rationale for this approach was that acquaintance-ships might influence the findings, and therefore the participants were selected on the basis of having only a superficial social relationship and having met only once. Based on in-depth interviews with these participants, the researcher then used a snowball sampling approach to obtain sufficient participants to reach data saturation and eventually settled on a total of 25 participants.

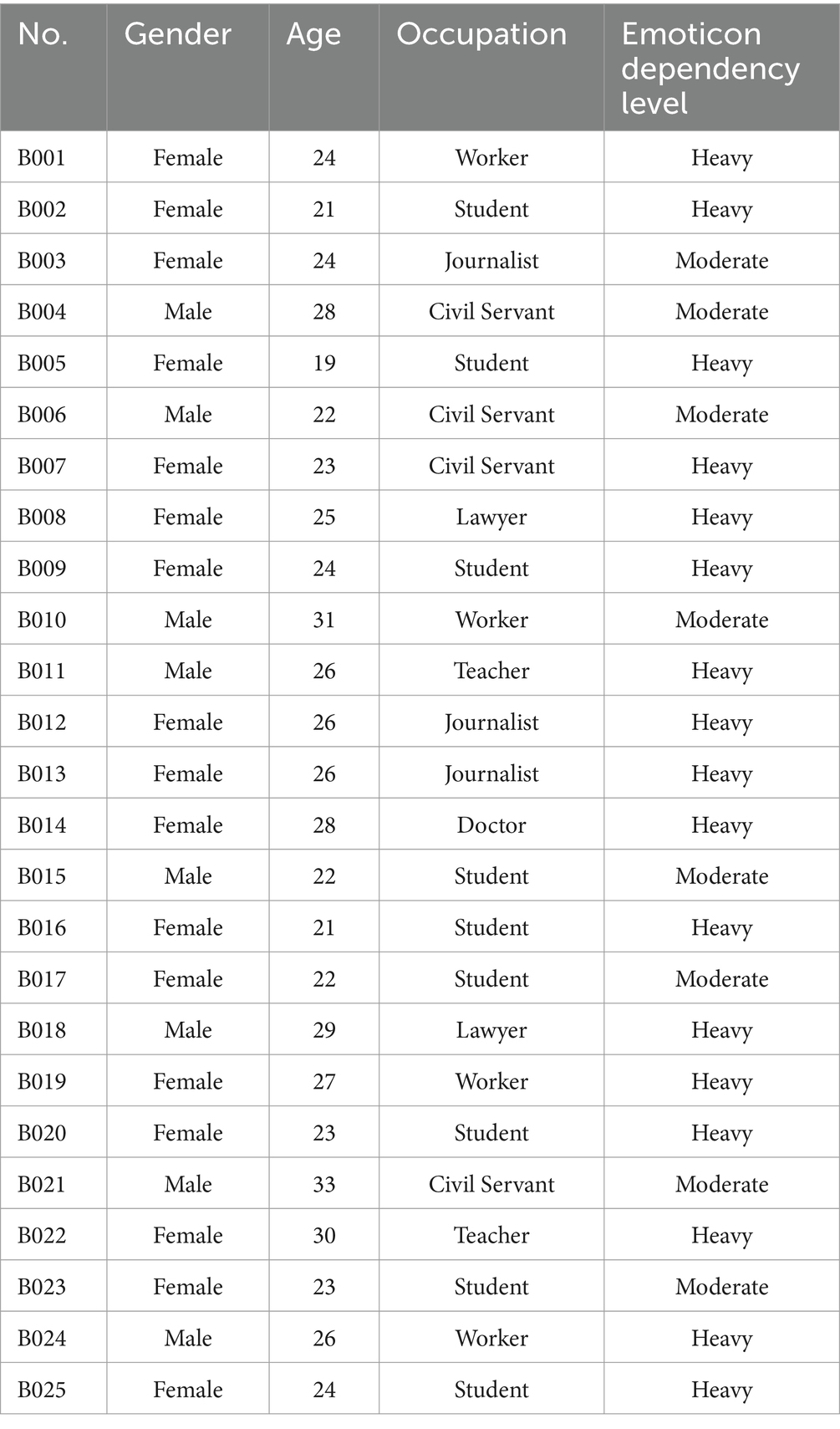

Individuals were informed of the study objectives prior to participation. All participation was voluntary, and students were given sufficient information before the interviews began. After obtaining participants’ consent, data were collected via Internet telephone. The interviewees (Table 1) were under the age of 35, which meets the age classification criteria for youth (35 years old and below) set by the Chinese government in the Medium-and Long-Term Youth Development Plan (2016–2025); there were 17 female and eight male participants. The interviewees involved students, journalists, doctors, teachers, and lawyers, which cover a wider range of occupations and allow for more representative data to be collected for the study. All interviewees frequently used emoticons in daily life and had extensive experience in producing and sharing them. We divided the respondents into medium and heavy emoticon users. Moderate users actively use emoticons while chatting online quite frequently (usually within 10 sentences on average), have a large stock of emoticons but update them less frequently (once a month on average), and a low degree of dependence on emoticons. Heavy users actively use emoticons while chatting online more frequently than moderate users (they add emoticons to every sentence in chat), have a large stock of emoticons and update them more frequently (adding new emoticons every day, once a week at most), and a high degree of dependence on emoticons. To protect the privacy of the participants, they have been referred to using numbers (B001–B025) (Table 1).

Instruments and data analysis

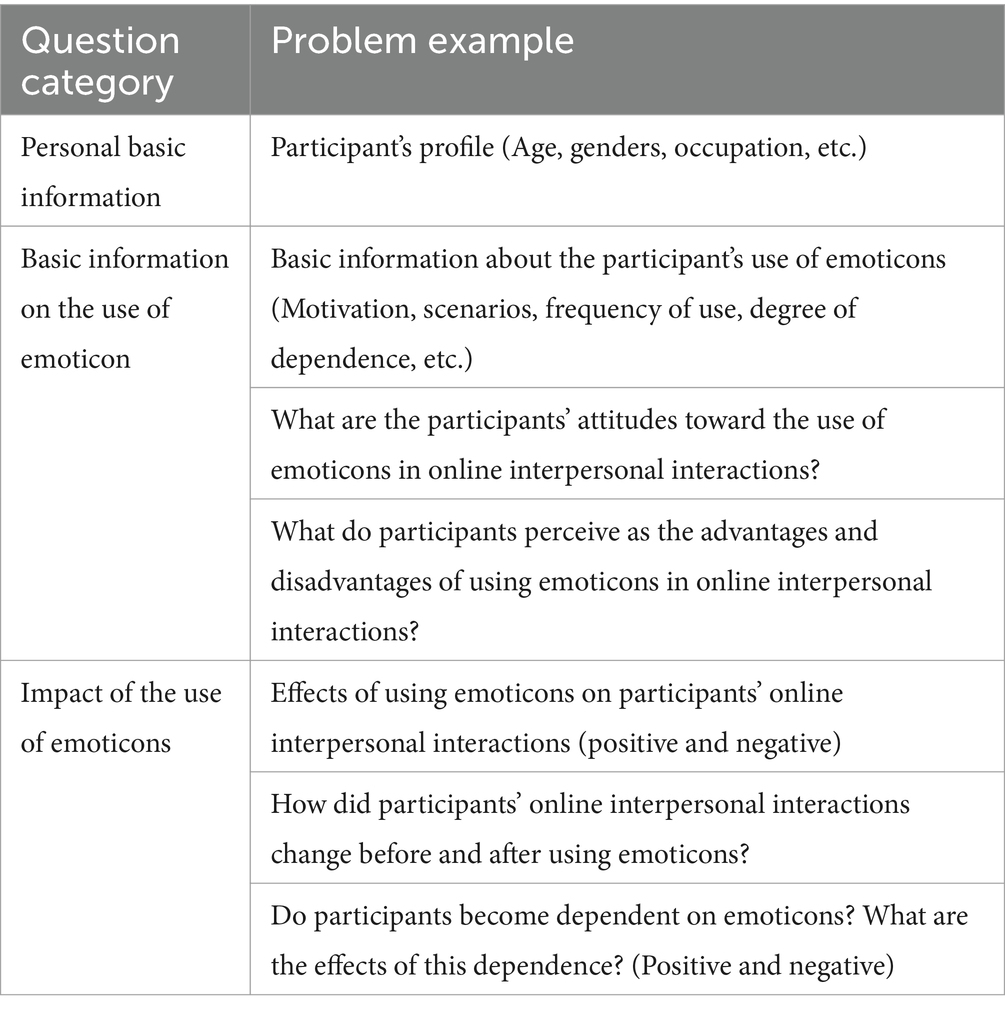

In-depth interviews were the primary research method used in this study. Through the analysis of in-depth interviews with 25 moderate to heavy users of emoticons, we assessed the role and influence of emoticons on youth interactions. We analyzed the dual value of these non-verbal symbols for youth for in-person and online interpersonal interactions. The impact of emoticon use on young people’s online social interaction is a socially relevant issue, and in-depth interviews are the easiest and most useful way to gather detailed, first-hand information. The interviews were conducted following a semi-structured design, either via telephone or in-person, and lasted roughly 30 min to 1 h depending on the participant. In the course of the interviews, participants were asked to share the reasons, methods and scenarios in which they had used emoticons, as well as the impacts and changes that had occurred in their daily lives as a result of using emoticons. The semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with the following questions in mind: how do people obtain emoticons and what are the scenarios in which they are used? What role do emoticons play in online interpersonal interactions? And finally, what is the impact of emoticons on online interpersonal interactions versus real interpersonal interactions? Additional questions were asked based on how far participants developed their answers to the questions, while respecting their subjective wishes, to obtain more comprehensive information. With the consent of the participants and to protect their privacy, the author recorded the interviews and collated and analyzed the interview data on an anonymous basis. The overall analysis of the data lasted for about 3 months. We sought to establish structural relationships between different texts in the vast amount of material through textual analysis, as well as to compare and contrast the texts on different themes to find differences and similarities (see Table 2).

Results

Although online interpersonal communication expands the spatial and temporal scope of traditional communication in terms of the form of interaction, the lack of face-to-face communication limits the inclusion of non-verbal symbols in the content of the interaction and the level of meaning exchange. In the absence of social context, written symbols are not sufficient to express the rich emotional information contained in interpersonal communication. Attempts have therefore been made to remedy this barrier to communication by technical means; emoticons are a typical representative of this attempt.

Emotional attachment and contextual bridging

At the primary level of communication, emoticons symbolically resolve uncertainty by adding meaning. Although online interpersonal communication allows for the exchange of information and the construction of meaning through textual symbols, it is not immune to the problems caused by the absence of context. It may be difficult to convey the complex emotions hidden behind words on both sides of interpersonal communication, and the information conveyed through emotions is, in some cases, more important than the textual information. Communication based on textual information, information encoding, and decoding also does not belong in the same field. Understanding the meaning of the encoder’s information is based on the decoder’s recollection of interpersonal relationships and emotional expressions. This context break may result in a lack of meaning and increased interpretive uncertainty. This uncertainty is further amplified by the dislocation of space and time, and we found young people were eager to create a field of interaction similar to face-to-face communication.

When I do not chat with you face to face, I do not know what kind of look and psychological activity you have. … sometimes chatting without posting a love packet will feel like he is not sharing a certain sense of irony with me. (Interview, B001)

Emoticons allow youth groups to compensate for the deficiencies of the field of online communication and deepen their interactions, reduce uncertainty, and express their presence. Young people express non-verbal information using pictures and symbols to compensate for field disconnection through symbolic constructions. In comparison to words, non-verbal symbols exhibit high flexibility, a low production threshold, a rich capacity to convey information, and rapid dissemination. These attributes can offset the dearth of non-verbal symbols in online communication, thereby facilitating the expression of meaning in online interpersonal interactions. Although they are not an exact substitute for physical presence, emoticons have developed a significant performative capacity, becoming the preferred medium for expressing emotion and conveying meaning in the context of new media. From the very first symbolic emoticons and emoticon expressions to the current picture and animated emoji, emoticon symbols enrich the expression of meaning and emotional exchange in online communication, while greatly reducing uncertainty.

It should be noted that emoticons support impression management in online interpersonal interactions and allow young people to articulate their emotional self-presentation. Impression management is when people attempt to manage and control the impressions others form of them; this control is achieved by influencing the definition of contexts designed by others (Goffman, 1956). Overcoming space–time barriers in online communication comes at the expense of social context, which removes the realistic basis for impression management online. Self-representation is limited by the fragmented expression of information, while personal impression management without feedback from others is trapped in the dilemma of self-construction. The use of emoticons has a self-referential effect, which prompts the user to express him-or herself in the way he or she imagines (Walther and D’Addario, 2001). The two-way nature of this presentation renders the self-presentation increasingly idealized, thereby complicating the distinction between the actual and the virtual self in the online space. This discrepancy and the resulting duality give rise to uncertainty with regard to the self-image.

In the event of interactors being unable to transmit non-verbal signals in social interactions, they will typically take the initiative and make some adjustments. Similarly, online youth groups utilize emoticons to convey emotions such as happiness, worry, anger and fear, thereby modifying the impressions they create in virtual contexts. The use of emoticons in online interpersonal interactions allows young people to construct their self-image. At the same time, social media provides the opportunity for others to evaluate and compare different social images, which, on the one hand, encourages young people to use emoticons more frequently, and on the other hand, strengthens the production of emoticon-based content.

I feel that emoticons allow me to get to know someone, and I can tell what kind of person they are based on the type of emoticons they send. (Interview B008)

During the interviews, we found that not only did emoticon use strengthen the expressive speech behavior of young people (Skovholt et al., 2014) but also that the richness with which young people were able to establish more stable identity markers online supported easier and more sustained online interpersonal interactions, which are accentuated through emoticons. In the interviews, most respondents noted this role of emoticons.

Some people are not in the same of line as when they chat online. Let us say you are a very active person, you are very hot inside, but you are good at hiding that personality in real life. Then you would vent this emotion when chatting online. Maybe this is the time when emoticons can bring out this feeling inside you. … This is the time when emotions are good for you to discover another side ofa person. (Interview, B011)

It is worth noting that while emoticons have weakened the lack of meaning in social interactions and given rise to more idealized self-presentation (Harris and Bardey, 2019), they are still essentially virtual interactions. This virtual state makes the transmission of information more likely to be performative and may cause confusion in self-image.

Emoticons also integrate the exchange of emotions into the interpersonal communication of youth networks by reinforcing relational interaction. Interpersonal interactions reflect the development of self-socialization. Information and emotional exchanges are the two main ways to interact in interpersonal relationships. In traditional interpersonal interactions, the exchange of information and the exchange of meaning are synchronized, and people manage relationships directly through sensory input such as sight, sound, and touch. Online interactions, however, sever the connection between the exchange of information and of meaning; this means that emotional exchange, which relies more on non-verbal symbols, is much less likely online. Emotional exchange is thus more important than information exchange in online communication. Self-disclosure is the main way an individual’s character is expressed in the development of interpersonal relationships. Self-disclosure includes not only verbal behavior and environmental orientation but also non-verbal behavior (Taylor, 1968). The information that individuals disclose to others deepens along with the relationship (Tang and Wang, 2012). Emoticons are a method for self-disclosure through non-verbal behavior: Young people express their emotions and feelings through emoticons in a way that seems authentic and natural. Emoticons are then directly reproduced in the virtual space as a “paralanguage” (Aldunate and González-Ibáñez, 2017). The in-depth interviews revealed that parties who share the same emoticon become closer in their online interpersonal interactions as communication deepens.

Some people may not know what to say after they have just added WeChat, so emoticons can be a good way to “break the ice” and bring the two sides closer together so that the conversation is not awkward. (Interview, B008)

Emoticons are rapidly becoming an integral part of online communication due to their low production threshold, rich content information, rapid dissemination, and adaptability to the fragmentation of online communication. Young people use emoticons to build and maintain intimate social relationships, enrich their inner world, and extend their emotional attachment. Young people insert emoticons that fit the context of their chats, and this kind of symbolic construction of meaning through emoticons can carry more emotional weight than text, as well as restoring the synchronization of in the exchange of information and meaning. This makes self-disclosure and relationship interaction more convenient. Such emotional exchanges through pictures can also produce misinterpretations, and the meanings of many emoticons have evolved through their real-life application, such that their meanings have become far removed from those they originally had when they were created. While emoticons have facilitated interpersonal interactions among young people online, they have also been reinterpreted and reconstructed as interpersonal communication continues to deepen, which has revealed new barriers to understanding relationship management. Determining how to recognize the distortions in emotional exchange created by the changing meanings of the emoticons used by young and how to coordinate the shift in online interaction is a new topic arising in research on online interpersonal communication.

Cultural compartmentalization and communication gaps

Emoticons have opened up a new way to communicate online, but due to human diversity in terms of cultural cognitive attitudes, social life background, values, and media use needs, how people use and understand symbols also differs. This difference is reflected in their communication; young people in subcultural fields rely on symbolic meanings to build an emoticon community to avoid confusion in self-image. Members of this community use symbolic meaning to further deepen their social relationships, which creates a gap in their interactions with other communities.

The significance of non-verbal symbols extends beyond the conveyance of information in meaningful communication. They also serve as crucial identifiers of cultural and group identity. In other words, individuals identify and establish relationships through non-verbal symbols, including clothing, gestures, and social habits. The cultural identity associated with the personal identity of a particular member of society serves to distinguish that individual from others (Littlejohn et al., 2016). As a form of non-verbal communication, emoticons play an integral role in online interpersonal interactions. Emoticons are a convenient and participatory form of non-verbal communication, conveying more information, expressing richer emotions and being more personalized than other non-verbal symbols. When using emoticon for online communication, young people strengthen their identity through the construction of symbols and meaningful interactions. Online communication is an extension of interpersonal communication into cyberspace, and it is naturally impossible to avoid the social compartmentalization that arises from cultural differences in communication. There is, however, a key difference in that the meaning of cultural compartmentalization assumed by non-verbal symbols online is often displayed in the form of emoticons.

Identity is a person’s perception of which group he or she belongs to; it is an important aspect of self-concept (Deaux, 1993). The use of emoticons creates a perception of emotional belonging based on meaningful interaction. The large user base and the wide range of online interactions make it easier for people to find others with the same or a similar symbolic identity in cyberspace. During the interviews, it appeared that a sense of community created by emoticon use was growing, while interaction with emoticons strengthened a sense of identity and psychologically reinforced the “perception of self-presence” (Miller and Madianou, 2012). The use of emoticons by youth groups serves to present their identity and values to others. The act of identification with the same or similar emoticons serves to deepen their social identity, thereby influencing their social relationships and social network construction.

The different types of emoticon are used more by people in their social circles, so it’s more of a compartmentalization, I guess, as people have different interests. (Interview, B010)

The use of emoticons among young people is not only a “community of discourse” (Mannay et al., 2018) but also a “community of identity.” The community formed by emoticon use is reflected not only in the difference in generational identity between use of emoticons by middle-aged and young people, but also the differences in group identity between different youth subculture groups—such as cute pets and MAG (manga, anime, and games)—due to differences in values, culture, and aesthetics. Different groups’ interpretations of symbols based on their own culture inevitably differ, and such differences are the root cause of the diversity in the identity of symbolic interaction. A common body of knowledge developed by the youth group using emoticons lies behind this difference (Garrison et al., 2011). For example, young people interpret the smile emoticon as a helpless, embarrassed fake smile, while the middle-aged and elderly groups understand it as a smile. Interpersonal interactions based on different symbolic interpretations thus inevitably produce cognitive barriers, which in turn reinforce identity.

The use of emoticons by young people to communicate selectively and further strengthen their psychological identity has given rise to circle segmentation. In spontaneously formed social circles, members of a circle identify with each other based on having the same or similar social backgrounds and value experiences, which can form a more obvious division from those outside the circle. This offline social stratification is further reinforced by online communication. Online interactions characterized by off-site virtual socialization are stimulated by both an objective information lag and inauthentic emotional expressions, and the social circles formed through emoticons are attentive to these differences in expression. Young people choose their social relationships through emoticon. The use or non-use of emoticons, the kind of emoticons used, and how they are used have become one of the main reasons for the creation of circles for online communication. The interviews revealed that people who share the same emotions are more likely to establish social relationships, and while these social expressions deepen, they strengthen psychological identity and intensify intimate relationships. Such emoticon-based socialization has expanded social relationships while furthering the individualized collectiveness (Soon and Kluver, 2014) in the identity of the youth group and deepening the separation of the different social circles.

They may have shared their favorite emoticons with others at first, but there would be many people who did not understand. So, over time, they would only share them with people who could like their emoticons. They have common interests and can understand them. (Interview B005)

As compartmentalization deepens, emoticons also become a language for interpersonal interaction that evokes and perpetuates a sense of individual group presence, while at the same time separating the group from other groups. Habitual differences in lifestyle and consumption lie behind this segregation and selective communication. Emoticons as such do not lead to segmentation, but the difference in the expressions and other habits of young people and the artificial differentiation of emoticon lead to the stratification of online social networks. It is worth noting that, compared to traditional forms of communication, the social circles generated by emoticons are more selective and casual, less stable, and more susceptible to multiple factors such as network environment, network usage behavior, personal factors, and cultural influences (Zhao et al., 2013). Young people can quickly establish social relationships through the use of the same emoticons, or they can leave a certain circle and join a new one at any time based on changes in their interests and aesthetics. This more casual choice of social circles and the ability to switch between such circles has not only deepened the divisions between social circles but also made social relationships more of a performance and a formality.

Young people reshape the space of shared meanings through symbolic contagion an emotional constructions when using emoticon for online social interaction. Face-to-face interactions rely on embodied contact and presence; as the frequency of interaction increases and the level of contact deepens, this communal space of meaning expands and the relationships become more intimate. Online interactions break the embodied presence of the shared meaning space, but the interactive exchange window built on textual symbols is abstract and does not fully reflect the rich emotions and psychological personalities of any of the parties to the interaction. It is also prone to subjective distortions and objective misalignments, which makes it difficult to ground online interactions and realize a common space of meaning. Non-verbal symbols, mainly emoticons, have become an important way to compensate and expand the space of shared meaning online, as well as acting as an icebreaker for establishing, maintaining, and developing social relationships. The interviews revealed that young people either use emoticon to open up new social relationships and break awkward conversations or share, collect, and produce emoticons to deepen existing social relationships. The same emoticons are also used to create closer relationships between people who share the same emoticon (Wang, 2015), and this closeness spreads along with the sharing of emoticons to create a symbolic infection.

If I’m chatting with someone I’ve just met and I find that they use the same type ofemoticons that Ido, then I’ll be more impressed with them too, and I’ll even want to go ask them for some emoticons. You’ll want to exchange emoticons with them so that the two of you will have a lot of emoticons together. (Interview, B012)

Symbolic contagion not only involves the deepening of intimacy but also the establishment of new social relationships. Individual production and use are based on individual expressions of emotion when socializing with emoticons, but when all members of a community produce and use them, they form the basis for communal interaction (Prada et al., 2018). The interviews revealed that emoticons have gradually shifted from conveying emotions to constructing emotions; they not only reshape social relationships but also reshape the value base of the shared meaning space.

Once I saw someone sending me emoticons that I really liked in an online community, then I tried to add her social account, we talked a lot together, and she introduced me to a lot of friends, and it felt like we had something in common. We are now very close friends, you can say we met through emoticons. (Interview, B005)

The use of emoticons by young people has gradually led to a blurring of the role of emoticons in conveying emotions. Instead, they have become immersed in the virtual social space constructed by emoticons, establishing social relationships between individuals through emoticons, maintaining social relationships through emoticons, and emoticons have become an indispensable part of network socialization. This process has resulted in a further strengthening of the dependence of young people on emoticons. Such non-verbal symbols have gradually transcended objective factors such as life experiences and cultural backgrounds to become primary values that constitute the space of shared meaning. This new way of constructing a communal meaning space makes establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships among young people faster and easier, while the social impressions formed based on emoticons are more emotional than life experiences and cultural backgrounds. The communal meaning space built on this foundation is also more susceptible to emotional tearing, which can lead to dysfunctional impression management. The contexts established through the use of emoticons in online interpersonal interactions and the personal images shaped by young people based on these emoticons can be disrupted by discrepancies in understanding between the two parties utilizing them. This can result in the deterioration of social relationships established and maintained by young people, leading to a reliance on self-imagined realities. It remains to be seen whether this reconstruction of emoticons can support the value base of a communal meaning space for online communication among young people in the long run, and balancing the relationship between verbal and non-verbal symbols remains a topic for youth using emoticons to ponder.

Alienated communication and virtual symbiosis

To a certain extent, emoticons can compensate for the lack of embodiment in online interactions, but they have also created additional problems. Emoticons permeate the whole online interaction process and even shape its emotional expression and meaningful exchange. The flexibility, openness, and ideation of emoticons fit the trend of fragmentation and emotionality of online interaction, which has given rise to an interactive chain of social symbols that are produced, interacted with, shared, and reprocessed. During the interviews, we found that for young people, although the exchange relationship based on emoticons is superficially a human relationship, it is essentially an extension of the symbiotic relationship between people and symbols that the youth group relies on emoticons to generate. The use and exchange of emoticons establish, maintain, and terminate social relationships and social capital, and this relationship between people and symbols has become equivalent to the symbiotic relationship between people. The social capital gained through this symbiotic relationship is even higher than traditional symbiotic relationships between people. Emoticon are not only an aid to expression but also a normalized social language. The majority of respondents said that they could no longer communicate with others online without emoticons, and in this sense, emoticons have become an essential part of online human interaction.

If I have a unique emoticon and send it to my friends during internet chats, they will be so envious of me that they want me to share it with them. Of course, I would not share it for free, they would have to take their best looking emoticon and exchange it with me. (Interview, B025)

I’m majoring in art, and sometimes I draw funny things in my life and make emoticons out of them. When my friends see them, they will share with me some material that they think is interesting and ask me to draw for them too. Although the process of creation is very tiring, I feel very accomplished and happy. Now my friends cannot live without me. (Interview, B023)

Emoticons are a bit more relaxed and light-hearted, and if you use text all the time, it can seem very formal, serious, and strange. Unless he’s talking to me seriously, if it’s just a more official greeting, I feel like I’m going to go “crazy” if I do not use emoticons for more than three sentences. (Interview, B004)

For online interpersonal interactions, the generalization of emoticons has been completely transformed from expressing to building emotions, and social symbolization has replaced symbolic socialization as the new norm for online interaction. During this transformation, emoticons gradually changed from a social mode to a social purpose, and socializing for the sake of emoticons and interacting for the sake of symbolic interaction has overshadowed the valued core of interpersonal interaction in terms of meaning exchange. As young people increasingly rely on emoticons, they have become an ice breaker as well as a wall builder. The more skilled young people are at using emoticon online, the more likely they are to be overwhelmed by offline social interaction, and the more likely they are to suffer from social phobia. It remains to be determined whether emoticons have facilitated or hijacked young people’s online interactions.

From the earliest days of emoji icons to emoji pictures and then emoticon motion pictures, the range of emoticons has grown in direct proportion to the demand for emotional expression. The compilation and analysis of interview data revealed that the main role of emoticons in young people’s online social interaction has been the transformation of ideation to the transmission of emotions, which then led to the building of emotions. Emoticon-sharing groups and communities have also emerged. Emoticons are not just a symbol but also a form of social capital, with young people producing personalized emoticon cards based on selfies, cute pets, and scenes, or using sketches, cartoons, and film characters as prototypes for secondary processing. Young people have been creating interactive in the form of free expression and independent creation; whether this is an awakening of their autonomy of expression or purposeless and irrational socialization remains an open question. However, the social software emoticon stores represented by WeChat, which provide a convenient consumption window for emoticon production, reflect the penetration of capital and consumerism into online interpersonal interactions. Furthermore, emoticons have given rise to a chain of symbolic production in which communicators produce, share, and consume on their own. The process of “purchase-use” renders emoticons as online interpersonal interactions vulnerable to the influence of consumerism. The concepts of “materialization,” “personalization,” and “privatization” have become instrumental in the appropriation of the emoticon as a means of occupying the spiritual domain of young people. The indulgence in the fabrication of lies through consumerist means, reinforced through the purchase and use of emoticons, is gradually alienating young people from their use of emoticons in an irreversible manner, under the manipulation of capital.

I cannot wait to buy it every time I see a new update to the emoticon store in my phone, wanting to be the first of my friends to have it and then send it to others. (Interview, B021)

Some of the emoticons I find while chatting on the internet, I have to modify it according to the needs of the scenario I am using it for and add some of my favorite elements to him so that I am satisfied. Sometimes I also take pictures of our cat and then make emoticons, it’s very cute and my friends love it. (Interview, B023)

As non-verbal symbols for online communication, emoticons cannot generally be replaced by verbal ideograms. The combined use of emoticons and text allows for the activation of a more intimate relationship (Hsieh and Tseng, 2017). Unlike traditional interpersonal interactions, online interactions lack physical presence and context. With the aid of emoticons, however, the psychological and emotional interactions are both more frequent and closer. When talking about the role of emoticons in online social networking in the interviews, participants all said that “you cannot talk without emoticons.” This seems to have become an online social consensus. From social opening to social closing, from ordinary relationships to intimate relationships, from deepening feelings to breaking awkwardness, emoticons have infiltrated every corner of young people’s online interactions, becoming a kind of language—a necessity for online interactions that transcend textual language. Indeed, emoticon language has become a necessity for online interpersonal interaction that is above and beyond textual language. The relationship between text language and emoticon thus seems to be alienating, as interactors can chat with others by competing to see who has more emoticons, while the use of text without emoticons seems completely unable to convey accurate emotional information. The role of text in online communication among young people has been eroded to some extent by the use of emoticons. Young people establish and maintain social relationships through the use of emoticons. Initially, this was done to compensate for the limitations of the absence of non-verbal symbols in network interpersonal interactions. Additionally, the use and production of emoticons has become a defining characteristic of young people’s network interpersonal interactions. Over time, emoticons have evolved from being auxiliary to being dominant in these interactions. They have become a central aspect of young people’s network interpersonal interactions. In network interpersonal interactions involving emoticons, the function of information communication gradually shifts toward entertainment interactions. Emoticons have become a social game, employed for their intrinsic value, while the meaning and value of interpersonal interactions are diminished in this context. It is worth noting that, as online behavior facilitates offline supportive relationships (Wang et al., 2018), this alienation is not only reflected in cyberspace but also shows a tendency to spread to real space.

Sometimes I find myself starting to mimic the emoticons, imitating the actions in them—even if it’s just some micro-expressions. This imitation is kind of subconscious, and then I feel like, oh my god, it’s like I’ve been alienated by the emoticons. (Interview, B010)

Most of the interview participants revealed that after using emoticons to communicate with others frequently on the Internet, they suddenly seemed not to know how to speak to others in person. Emoticons have become a subconscious form of self-expression. When the scene changes and emoticons are removed from their social interactions, they experience intense discomfort and, in severe cases, even expression dissonance. The use of emoticons by youth groups serves to reinforce their collective identity, a phenomenon that is further amplified by the pervasiveness of social media. In social interactions, young people demonstrate a reliance on emoticons, becoming immersed in the social environment shaped by emoticons in both virtual and real-world contexts. This promotes mutual identification between interpersonal interactions and shifts the use of emoticons from the virtual to the real world, further blurring the boundaries between the virtual and the real. The distinction between the virtual and the real is increasingly difficult to discern. The identification of young people with emoticons is more profound, and their interpersonal interactions with the real world are increasingly severed. In this process, emoticons have gradually ceased to serve the function of compensating for the uncertainty of information and lack of context in online interpersonal interactions. Instead, they have become an obstacle that affects normal interpersonal interactions.

From augmented expression to “no emoticon, no joy,” from virtualization to lifestyle, young people are artificially constructing emoticons in their use of these symbols, which seem gradually to be becoming an online ritual (Jacobs, 2007), pointing.

The way to a new form of online human interaction. This tension between the constructed and the constructed calls for further reflection on the emoticon-based online interactions of young people.

Conclusion

This study focused on the impact of the use of emoticons on the online interactions of teenagers and how this use affects their normal social activities. Findings from the interviews suggest that the use of emoticons among youth’s is very high and that this use has largely transcended ordinary communication to become an important part of youth online social interaction. The interview data further revealed that the influence of emoticons on teenagers’ online social interaction is apparent in three aspects: (1) emoticons compensate for the lack of context created by virtual socialization on the Internet and correct the social dissonance caused by embodied absence; (2) through the use of emoticons, young people have established an emoticon community online, which strengthens their online social interaction and forms a deeper social identity, thereby deepening the stratification of teenagers’ online social interactions to form a new social divide; (3) emoticons have infiltrated into young people’s online social interactions, which has gradually extended from the Internet to reality and now affects their normal, in-person social interactions. The present study suggests that the non-verbal symbols, initially designed to facilitate social interaction, have gradually begun to hijack the normal social interaction of teenagers. Further research is necessary to answer the question of how the relationship between youth groups and emoticons will develop in the future. The findings of the present study demonstrate that the infiltration and alienation of emoticons into teenagers’ social interactions is worthy of attention.

Discussion

Non-verbal symbols have always played a crucial role in interpersonal interactions—from gestures, expressions, and clothing to emoticons. While online interactions can blur the influence of space–time social interactions, they can hardly replace the role of non-verbal symbols. Emoticons have become an important addition to social bonding and emotional communication for teenagers. Emoticons amplify the significance of emotional interactions in communicating while compensating for physical absence. We should also note that current research has begun to focus on age and gender differences in using emoticons (Fullwood et al., 2013; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017; Tossell et al., 2012); use, perceived motivation, and the impact of social context on emoticon use (Derks et al., 2007a, 2007b); the use of emoticons in online marketing communications (Ma and Wang, 2021); and the impact of the nature of emoticons on online social interaction (Brito et al., 2020). These studies have examined the relationship between the use of emoticons and interpersonal communication in different dimensions and built a framework for understanding these nonverbal signs and the resulting social topics.

Our study is primarily concerned with the positive aspects of emoticons in young people’s online interpersonal interactions. However, it also addresses the potential for alienation and the dependence on emoticons that may accompany this phenomenon. The study aims to provide insights into the implications of emoticons for online interpersonal interactions. Nevertheless, the study is not without limitations. Firstly, the initial participant in the study was selected from a pool of individuals with whom the authors were already acquainted. While efforts were made to minimize the impact of this choice on the research process, including the use of empirical information in the paper to support the argument and the infrequent selection of the first participant’s interviews, the influence of this decision is nevertheless objective. The aggregation of this singular study afforded us a lucid understanding of the demographic utilizing emoticons and facilitated the acquisition of a considerable number of youthful emoticon users. These individuals do not have a social relationship with us, and the information they provide will be more objective. They may therefore be considered potential participants for our next study. Secondly, as the use of emoticons in online interpersonal interactions becomes increasingly prevalent, it is imperative to consider the limitations of these interactions. In addition to classifying and categorizing emoticons, it is essential to conduct a thorough semantic analysis of their usage. This process requires a significant investment of time and the participation of a larger number of individuals. However, it is a crucial step in recognizing the role of emoticons in online interpersonal communication. At the same time, we should think about when emoticons become a kind of language and a social capital, as well as when their rational meaning gives way to emotional meaning: do they “build a wall” or “open a door” for online communication among youths? What are the implications of the growing social divide based on the emoticon communities for the socialization of young people? What role should emoticons play in the tensions of online communication?

Our analysis of the impact of emoticons on online human interaction was based on young people who are heavy and moderate users of emoticons. For those who never or rarely use emoticons, the analysis of some of the phenomena may be overstated. These phenomena do exist, however, and while the emoticon-based alienation of online interpersonal communication may only be reflected in some young people at this stage, it is still worth thinking about and subjecting to further research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GJ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. RZ: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aldunate, N., and González-Ibáñez, R. (2017). An integrated review of emoticons in computer-mediated communication. Front. Psychol. 7:2061. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02061

Blum-Ross and Livingstone (2017). “Sharenting,” parent blogging, and the boundaries of the digital self. Pop. Commun. 15, 110–125. doi: 10.1080/15405702.2016.1223300

Brito, P. Q., Torres, S., and Fernandes, J. (2020). What kind of emotions do emoticons communicate? Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 32, 1495–1517. doi: 10.1108/APJML-03-2019-0136

Chen, X., and Siu, K. W. M. (2016). Exploring user behaviour of emoticon use among Chinese youth. Behav. Inform. Technol. 36, 637–649. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2016.1269199

Cherbonnier, A., Brown, G., and Michinov, N. (2024). People follow emotion display rules when choosing emoticons on social media. Commun. Res. Rep. 41, 36–48. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2024.2318040

Chitac, I. M., Knowles, D., and Dhaliwal, S. (2024). What is not said in organisational methodology: how to measure non-verbal communication. Manag. Decis. 62, 1216–1237. doi: 10.1108/MD-05-2022-0618

De, P., and Bakhshi, M. (2024). Managing uncertainties in technology-mediated communication: a qualitative study of business students’ perception of emoji/emoticon usage in a business context. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 67, 211–228. doi: 10.1109/TPC.2024.3382788

Derks, D., Bos, A. E. R., and von Grumbkow, J. (2007a). Emoticons and online message interpretation. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 26, 379–388. doi: 10.1177/0894439307311611

Derks, D., Bos, A. E. R., and Von Grumbkow, J. (2007b). Emoticons and social interaction on the internet: the importance of social context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 23, 842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2004.11.013

Fischer, B., and Herbert, C. (2021). Emoji as affective symbols: affective judgments of emoji, emoticons, and human faces varying in emotional content. Front. Psychol. 12:645173. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645173

Frențiu, L. (2019). The Management of non-verbal Signs in disagreements. Rom. J. Eng. Stu. 16, 119–122. doi: 10.1515/rjes-2019-0014

Fullwood, C., Orchard, L. J., and Floyd, S. A. (2013). Emoticon convergence in internet chat rooms. Soc. Semiot. 23, 648–662. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2012.739000

Garrison, A., Remley, D., Thomas, P., and Wierszewski, E. (2011). Conventional faces: emoticons in instant messaging discourse. Comput. Compos. 28, 112–125. doi: 10.1016/j.compcom.2011.04.001

Goffman, E. (1956). The presentation of self in everyday life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press.

Guo, J., Asmawi, A., and Fan, L. (2024). The mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between social anxiety and communication skills among middle school students in China. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 29:315. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2024.2389315

Harris, E., and Bardey, A. C. (2019). Do Instagram profiles accurately portray personality? An investigation into idealized online self-presentation. Front. Psychol. 10:871. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00871

Hsieh, S. H., and Tseng, T. H. (2017). Playfulness in mobile instant messaging: examining the influence of emoticons and text messaging on social interaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 69, 405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.052

Jacobs, S. (2007). Virtually sacred: the performance of asynchronous cyber-rituals in online spaces. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 12, 1103–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00365.x

Knapp, M., et al. (1994). “Background and current trends in the study of interpersonal communication” in Handbook of interpersonal communication. eds. M. Knapp and G. R. Miller. 2nd ed (Thousand Oaks: Sage), 3–14.

Kornfield, R., Rae, I., and Mutlu, B. (2021). So close and yet so far: how embodiment shapes the effects of distance in remote collaboration. Commun. Stud. 72, 967–993. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2021.2011362

Lin, K., Kan, X., and Liu, M. (2024). Knowledge extraction by integrating emojis with text from online reviews. J. Knowl. Manag. 28, 2712–2728. doi: 10.1108/JKM-01-2024-0104

Littlejohn, S. W., Foss, K. A., and Oetze, J. G. (2016). Theories of human communication. Long Grove: Waveland Press, Inc.

Lo, S.-K. (2008). The nonverbal communication functions of emoticons in computer-mediated communication. Cyber Psychol. Behav. 11, 595–597. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0132

Ma, R., and Wang, W. (2021). Smile or pity? Examine the impact of emoticon valence on customer satisfaction and purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 134, 443–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.057

Mannay, D., Creaghan, J., Gallagher, D., Marzella, R., Mason, S., Morgan, M., et al. (2018). Negotiating closed doors and constraining deadlines: the potential of visual ethnography to effectually explore private and public spaces of motherhood and parenting. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 47, 758–781. doi: 10.1177/0891241617744858

Mei, A. T., Wang, X., and Ge, Y. (2004). Intelligent sensor and information acquisition. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 5439, 241–248. doi: 10.1117/12.549470

Mezgár, I. (2009). “Trust building in virtual communities” in Leveraging knowledge for innovation in collaborative networks. PRO-VE 2009. IFIP advances in information and communication technology, Vol. 7. eds. L. M. Camarinha-Matos, I. Paraskakis, and H. Afsarmanesh (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer).

Miller, D., and Madianou, M. (2012). Should you accept a friends request from your mother? And other Filipino dilemmas. Int. Rev. Soc. Res. 2, 9–28. doi: 10.1515/irsr-2012-0002

Nadia, A. J. D., de Vaate, B., Veldhuis, J., and Konijn, E. A. (2019). How online self-presentation affects well-being and body image: a systematic review. Telemat. Inform 47:10316. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.101316

Oleszkiewicz, A., Karwowski, M., Pisanski, K., Sorokowski, P., Sobrado, B., and Sorokowska, A. (2017). Who uses emoticons? Data from 86 702 Facebook users. Personal. Individ. Differ. 119, 289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.034

Prada, M., Rodrigues, D. L., Garrido, M. V., Lopes, D., Cavalheiro, B., and Gaspar, R. (2018). Motives, frequency and attitudes toward emoji and emoticon use telematics and informatics. Telematic. Inf. 35, 1925–1934. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.06.005

Rahmalina, R., and Gunawan, W. (2024). What multimodal components, tools, dataset and focus of emotion are used in the current research of multimodal emotion: a systematic literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 10:6309. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2024.2376309

Saramandi, A., Au, Y. K., Koukoutsakis, A., Zheng, C. Y., Godwin, A., Bianchi-Berthouze, N., et al. (2024). Tactile emoticons: conveying social emotions and intentions with manual and robotic tactile feedback during social media communications. PLoS One 19:e0304417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0304417

Shen, L., Wang, X., Li, S., Lee, L. H., Fan, M., and Hui, P. (2024). Emoji chat: toward designing emoji-driven social interaction in VR museums. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Int. 15, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2024.2387902

Shokrollahi, A. (2014). The theoretical perspectives in verbal & non-verbal Communication. Asian J. Dev. Matters 8, 214–220.

Skovholt, K., Grønning, A., and Kankaanranta, A. (2014). The communicative functions of emoticons in workplace E-mails. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 19, 780–797. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12063

Soon, C., and Kluver, R. (2014). Uniting political bloggers in diversity: collective identity and web activism. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 19, 500–515. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12079

Stevenson, C. L. (1999). The influence of nonverbal symbols on the meaning of motive talk. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 28, 364–388. doi: 10.1177/089124199129023488

Tandyonomanu, D. (2018). Emoticon: representations of nonverbal symbols in communication technology. IOP Conf. Series Mat. Sci. Eng. 288:012052. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/288/1/012052

Tang, J.-H., and Wang, C.-C. (2012). Self-disclosure among bloggers: re-examination of social penetration theory. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 15, 245–250. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2011.0403

Taylor, D. A. (1968). The development of interpersonal relationships: social penetration processes. J. Soc. Psychol. 75, 79–90. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1968.9712476

Temel Eginli, A., and Ozmelek Tas, N. (2018). Interpersonal communication in social networking sites: an investigation in the framework of uses and gratification theory. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 8, 81–104. doi: 10.12973/ojcmt/2355

Thelwall, M., and Wilkinson, D. (2009). Public dialogs in social network sites: what is their purpose? J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 61, 392–404. doi: 10.1002/asi.21241

Thorns, B., and Eryilmaz, E. (2014). How media choice affects learner interactions in distance learning classes. Comput. Educ. 75, 112–126. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.02.002

Tossell, C. C., Kortum, P., Shepard, C., Barg-Walkow, L. H., Rahmati, A., and Zhong, L. (2012). A longitudinal study of emoticon use in text messaging from smartphones. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28, 659–663. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.11.012

Walther, J. B., and D’Addario, K. P. (2001). The impacts of emoticons on message interpretation in computer-mediated communication. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 19, 324–347. doi: 10.1177/089443930101900307

Wang, S. S. (2015). More than words? The effect of line character sticker use on intimacy in the Mobile communication environment. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 34, 456–478. doi: 10.1177/0894439315590209

Wang, G., Zhang, W., and Zeng, R. (2018). WeChat use intensity and social support: the moderating effect of motivators for WeChat use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 91, 244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.010

Weedon, C., and Jordan, G. (2012). Collective memory: theory and politics. Soc. Semiot. 22, 143–153. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2012.6649

Zhao, J., Sun, X., Zhou, Z., Wei, H., and Niu, G. (2013). Interpersonal trust in online communication. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 21, 1493–1501. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2013.01493

Keywords: value construction, alienated communication, online interpersonal communication, emoticons, social media interaction

Citation: Ju G and Zhao R (2024) How do emoticons affect youth social interaction? The impact of emoticon use on youths online interpersonal interactions. Front. Commun. 9:1452633. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1452633

Edited by:

Maria Grazia Sindoni, University of Messina, ItalyReviewed by:

Stephan Packard, University of Cologne, GermanyAnthony Cherbonnier, Université de Lille, France

Copyright © 2024 Ju and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ru Zhao, emhhb3J1QG53dS5lZHUuY24=

Gaofei Ju1

Gaofei Ju1 Ru Zhao

Ru Zhao