- Department of Linguistics and English Language, Lancaster University, Lancaster, United Kingdom

The communication of news relies on semiotic resources besides language, including various audiovisual modes of representation. Owing to the difficulties associated with obtaining televisual data, the vast majority of research addressing multimodality in the news has been targeted at print news media, where various strategies in visual representation and patterns of interaction between verbal and visual modes have been discerned. Where televisual data has been interrogated, this has been based on a very limited number of data points. In this study, I exploit the NewsScape library – a massive multimodal corpus of news communication – to investigate multimodal representations of immigration in television news. Accessible via CQPWeb, the corpus is searched for target utterances refugees/(im)migrants have VERBed and refugees/(im)migrants are VERBing. The co-verbal images accompanying 474 utterances describing motion events are analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively. Among the results discussed are that refugees/migrants are depicted in large rather than small groups, that they are depicted in transit somewhere along the migratory journey rather than in countries of origin or destination countries, that they are depicted on land more than at sea, that they are depicted in security contexts, and that they are erased represented instead through abstract forms such as maps. Differences in the visual representation of people designated as ‘refugee’ versus ‘migrant’ are also observed and discussed.

1 Background

Refugees and migrants are among the most marginalized, maligned and disempowered people on the planet. For example, since the beginning of civil war in Syria in 2011, some 11 million people have been displaced requiring humanitarian assistance. Of these, 6 million have been internally displaced while 5 million have been externally displaced seeking asylum or being housed in refugee camps in countries around the world. In spite of such circumstances, refugees and migrants are overwhelmingly treated by the media as bringing crisis rather than themselves being in a crisis. Verbal and visual representations of migration perpetuate images of refugees and migrants as a dangerous and alien Other (Gabrialetos and Baker, 2008; KhosraviNik, 2009; Batziou, 2011; Bleiker et al., 2013; Chouliaraki and Zaborowski, 2017; Wilmott, 2017) and thus legitimate hostile anti-immigration ideologies and policies (Martin Rojo and van Dijk, 1997; van Leeuwen and Wodak, 1999). Media discourses are particularly effective drivers of public opinion on the topic of migration. For example, negative portrayals of immigrants are shown to increase ingroup favoritism and outgroup hostility (Schemer, 2012; Schemer and Meltzer, 2019; Conzo et al., 2021; Scherman et al., 2022). When linked with crime, a negative framing of immigration in the news influences voting behavior in favor of anti-immigrant parties (Burscher et al., 2015). Conversely, exposure to more positive coverage, including instances of successful intergroup contact, results in more positive attitudes toward refugees and migrants and decreased support for restrictive border and security policies (Joyce and Harwood, 2014; Djourelova, 2023).

Within linguistics, a large number of studies have investigated media discourses of immigration from an explicitly critical perspective to identify and expose the specific semiotic forms implicated in discursive constructions of power, prejudice and discrimination (Reisigl and Wodak, 2001; KhosraviNik, 2010a). The majority of this research has been directed at the print and online content of European and North American newspapers (e.g., Gabrialetos and Baker, 2008; KhosraviNik, 2009, 2010b; Alaazi et al., 2021). While this has traditionally been an area of qualitative research, quantitative methods based in corpus linguistics are increasingly used to interrogate larger, more representative datasets (Baker and McEnery, 2005; Baker et al., 2008; Gabrialetos and Baker, 2008; Taylor, 2014; Omidian Sijani, 2023). Such quantitative methods enable more generalized patterns of representation to be discerned, help to mitigate potential biases in data selection, and facilitate systematic comparative analyses across various dimensions including time, geographic region and media institution (Mautner, 2005, 2009; Baker and Levon, 2015). Gabrialetos and Baker (2008) examined collocates of the terms refugees, asylum seekers, immigrants and migrants (RASIM) that persisted in a 140-million-word corpus of UK news articles published over a ten-year period. Collocates are words which occur within a defined span of a given “node” with marked frequency and thus with a degree of statistical predictability. The collocates of a word contribute to its semantic profile (Stubbs, 1995). Crucially, as a result, the concept lexicalized by a collocate may be primed on occasions when the collocate is not actually present (Stubbs, 1996, 2002). Thus, the concept ILLEGAL may be primed by the word immigrant owing to the frequency with which the words illegal and immigrant co-occur with one another. Collocates observed by Gabrialetos and Baker (2008) fell into a limited number of semantic categories suggesting a small set of topics or themes commonly associated with RASIM, the majority of which are indexical of a negative stance. Common themes included entry, provenance/destination/transit, economic problem, legality and return/repatriation. The most common theme was number with one in five uses of refugees and asylum seekers being accompanied by some form of quantification. Three lemmas that featured as collocates of refugees and asylum seekers to encode quantity information were FLOOD, POUR and STREAM, which in this context provide a metaphorical framing of migrants as an excessive quantity of water. Interestingly, in their corpus, the term migrant did not register any quantity collocates.

Media discourses of migration are found to rely extensively on metaphorical themes to frame refugees and migrants as dangerous, different and undesirable, though it should be noted that the frequency and evaluative functions of metaphors for migration fluctuate over time (Taylor, 2021). Human migration is framed as a natural disaster through water metaphors which describe refugees and migrants in terms of ‘floods’, ‘tidal waves’ and even ‘tsunamis’ (El Refaie, 2001; Santa Ana, 2002; Charteris-Black, 2006; Abid et al., 2017; Dolores Porto, 2022). Refugees and migrants are dehumanized through metaphors which compare them to animals or infectious diseases (Santa Ana, 1999; Cisneros, 2008; Musolff, 2015). And they are constructed as an aggressive enemy through militarizing metaphors which describe them as an ‘invading force’ (El Refaie, 2001; Hart, 2021). Metaphors matter as they achieve cognitive framing effects (Robins and Mayer, 2000). For example, people are more negatively disposed to immigration when it is presented as a ‘flood’ or ‘invasion’ compared to more positive or neutral metaphors (Chkhaidze et al., 2021). Inundation metaphors (in which immigration is described in terms of floods, waves and tides) are shown specifically to increase support for policy measures designed to prevent immigration, such as the construction of a border wall (Jiminez et al., 2021), while dehumanizing metaphors are shown to elicit feelings of disgust and anger and similarly increase support for hostile immigration policies (Marshall and Shapiro, 2018; Utych, 2018).

News texts are inherently multimodal containing visual as well as verbal elements (Caple and Knox, 2015; Cheema et al., 2023) and there is now increasing interest in the visual and multimodal representation of refugees and migrants in online and print news media (Martínez Lirola, 2016, 2022; Martínez Lirola and Zammit, 2017; Wilmott, 2017; Farris and Silber Mohamed, 2018; Catalano and Musolff, 2019; Romano and Dolores Porto, 2021). Many of the themes presented verbally in media discourses of immigration are repeated visually in images such as news photographs. For example, refugees and migrants tend to be shown in large groups rather than small groups (Martínez Lirola, 2016; Wilmott, 2017), in dehumanizing contexts (Martínez Lirola, 2022), or in contexts of crime/security (Martínez Lirola, 2016; Wilmott, 2017; Farris and Silber Mohamed, 2018; Catalano and Musolff, 2019). In connection with provenance/destination/transit, refugees and migrants are typically shown somewhere along the way in their migratory journey (transit or PATH) rather than in destination countries (destination or GOAL) or in the places from which they originate (provenance or SOURCE) (Romano and Dolores Porto, 2021).

Images are particularly important in news communication. Eye-tracking studies show that images are among the first entry-points to a news text and that they receive a disproportionate amount of attention from readers (Bucher and Schumacher, 2006; Quinn et al., 2007; Holsanova and Nord, 2010; Leckner, 2012). When presented in the news, images are shown to enhance recall (Graber, 1990), to affect evaluations of social actions and social actors (Arpan et al., 2006), and to influence behavioral intentions (Powell et al., 2015; Geise et al., 2021). They are particularly important in shaping public attitudes and opinions with respect to immigration (Azevedo et al., 2021; Madrigal and Soroka, 2023). For example, Madrigal and Soroka (2023) show that among people who are high in general threat sensitivity, anti-immigration attitudes are mitigated by images of individual migrants but not images of groups of migrants. Similarly, Azevedo et al. (2021) show that exposure to images depicting refugees in large faceless groups results in increased implicit dehumanization (based on attributions of secondary emotions) compared to images depicting refugees in small groups. Images of large groups also lead to increased support for anti-refugee policies and decreased support for pro-refugee policies (Azevedo et al., 2021). Azevedo et al. (2021) further show the significance of narrative context where images of large groups at sea compared to on land result in even greater dehumanization. Azevedo et al. (2021) (p. 14) conclude that “the decision of what is made visible and how [in news images] has consequences for the ways in which we perceive and relate to other human beings, especially in a culture that is powered by images at unprecedented levels.”

Digital social media platforms might be expected to provide a space in which counter-hegemonic discourses can develop (Fozdar and Pedersen, 2013). However, discourses articulated in social media settings are shown to echo those advanced by traditional media outlets and in fact to present more extreme and polemical versions of already hostile discourses (Musolff, 2015; Ekman, 2019; Walsh, 2023). This suggests that legacy media retain a central role in setting political agendas (Nielsen and Schrøder, 2014; Langer and Gruber, 2021). Among the legacy media, it is television that is the most significant platform (Schrøder and Kobbernagel, 2010; Papathanassopoulos et al., 2013; Nielsen and Schrøder, 2014). For example, based on a survey of ten countries, including the UK and the USA, Nielsen and Schrøder (2014) show that people not only consult television news more often than they do news provided by social and other legacy media but that they consider television to be the most important source of news. Despite the key role of television in news communication, there are very few studies investigating the representation of refugees and migrants in TV news media. This is perhaps owing to the difficulties associated with gathering televisual data (Mistiaen, 2019: 57). Those that are to be found are either focused exclusively on language, where both corpus (Mistiaen, 2019) and content (Jacobs et al., 2016) analyses show that immigration is associated with topics of conflict, crime, security and terrorism, or else are based on a very limited number of data points (e.g., López, 2020). The visual and multimodal representation of refugees and migrants in TV news remains an unaddressed issue, especially based on evidence from large-scale corpora.

Multimodal corpora do now exist and their availability has led to major revisions of linguistic theory, including the notion of multimodal constructions within cognitive linguistics (Steen and Turner, 2013; Kok and Cienki, 2016; Cienki, 2017; Ziem, 2017; Zima, 2017; Zima and Bergs, 2017; Uhrig, 2022; Lehmann, 2024). Goldberg (2006: 5) defines a construction as a “learned pairing of form with semantic or discourse functions” where forms include morphemes or words, idioms, and partially lexically filled as well as fully general phrasal patterns. A multimodal construction is a conventionalized form-meaning pairing whose form consists of representations belonging to more than one semiotic mode. Multimodal constructions are thus distinct from incidental co-occurrences (Lehmann, 2024). Multimodal constructions are abstractions that constitute part of speakers’ linguistic knowledge. They are both derived from and manifested in patterns of co-occurrence between verbal and non-verbal forms repeated across usage events.

Most of the research addressing multimodal constructions has been focused on gesture-speech combinations where a multimodal construction is defined as “a conventionalized pairing of a complex form that consists, at least, of a verbal element combined with a kinetic element” (Ziem, 2017: 5). An example would be imperfective grammatical forms which are shown to be regularly accompanied by gestures that are longer in duration, more complex, and unbounded, thus reflecting the event-internal perspective adopted in the progressive aspect (Duncan, 2002; Parrill et al., 2013; Denisova et al., 2018).

The question of when a multimodal form-meaning pairing achieves constructional status is a largely quantitative one where multimodal forms that co-occur “recurrently” or with “sufficient frequency” can be considered instantiations of a multimodal construction (Zima and Bergs, 2017). However, there is no specific threshold that must be passed in order to count as a construction and we are better thinking in terms of degrees of entrenchment than a binary opposition between constructional and non-constructional status (Uhrig, 2022). For example, Zima (2017) shows that the construction [all the way from X PREP Y] occurs with a specific gestural form in 80% of cases while Uhrig (2022) shows that constructions involving throwing verbs (e.g., fling, lob) occur with a ‘throwing’ gesture on average 54% of the time.

Crucially, constructions may exist in the language at large or may be particular to specific genres and discourses (Antonopoulou and Nikiforidou, 2011; Groom, 2019). While the majority of research has been directed at verbal + kinetic multimodal constructions, visual and audiovisual correlates of linguistic forms have also been investigated, including specifically in news communication (Steen and Turner, 2013; Hart and Marmol Queralto, 2021). Steen and Turner (2013) show that TV news has standardized visual routines that are deployed as part of specific multimodal constructions. For example, when narrating a news event, the past-tense + proximal deictic construction (as in “was/were + now”) has a tendency to include a zooming in on the entity whose experiences are being recounted. The image in a verbal + visual multimodal construction is thus not a specific image but a schematic one which captures and defines the semiotic properties of its instantiations.

A similar notion developed in corpus linguistics is that of ‘collustrations’, which McGlashan (2021: 227) defines as “repeated co-occurrences between representations in linguistic and visual semiotic resources across numerous texts.” The difference between collustrations and multimodal constructions is that collustration describes a relationship between verbal and visual elements at the level of texts while multimodal construction refers to an entrenched structure in the minds of language users. Collustrations can thus be seen as the predictable outcome of multimodal constructions which, following a usage-based account, are at the same time derived from the collustrational behaviors of language and image. As with collocation, the visual component of a multimodal construction is likely to be evoked by its verbal counterpart even in cases where it is not itself co-instantiated. The images that regularly occur alongside verbal expressions are thus not only important contributors of meaning within the specific communicative events of which they are a part but the mental imagery they embody becomes a meaningful feature of the linguistic expressions themselves, independently of co-verbal images (Hart, 2016). Studying the visual correlates of verbal expressions in media discourses of migration can therefore shed crucial light not only on the visual and multimodal representation of refugees and migrants but on the visually derived connotations of verbal forms employed in their description.

2 Data and method

2.1 The NewsScape library

This study exploits the NewsScape Library,1 a massive multimodal corpus of television news held jointly by the libraries of the University of California at Los Angeles and Case Western Reserve University (Steen and Turner, 2013; Steen et al., 2018; Uhrig, 2018). The database is curated by and informs the research activities of the Distributed Little Red Hen Lab2. NewsScape has been recording major TV news programs broadcast predominantly in the United States since 2011. As of 2018, the database consists of 370,000 h of audiovisual news communication that is time-stamped and co-aligned with 3bn words of closed-caption text. This makes the corpus larger than both the British National Corpus (100 million words) and the Corpus of Contemporary American English (1 billion words). The closed captioning provides a transcription of the audio portion of the video material and is fully searchable via CQPWeb, a web-based corpus analysis system (Hardie, 2012). When searched for target utterances, CQPWeb returns ‘hits’ displayed in concordance lines together with a link to the time-stamped entry in the NewsScape Library. This enables the visual forms accompanying verbal expressions to be easily located, cataloged and counted and thus for relations of co-occurrence between verbal and visual forms to be established. The NewsScape Library has supported research investigating the multimodal representation of time (Valenzuela et al., 2020), grammatical aspect (Hinnell, 2018) and number (Alcarez-Carrión et al., 2022). This study is the first to use the corpus to systematically analyze multimodal communication around a specific social topic.

2.2 Data collection

Since motion is an inherent aspect of the migratory process with motion events having high news value and being especially sensitive to ideological construal in media communication (Hart, 2024), the analysis focused on verbs of motion. It also focused specifically on expressions of self-activated motion rather than caused motion to consider the agentive processes ascribed to refugees/migrants.

The corpus was searched for four constructions in which motion verbs feature: [refugees have VERBed]/[*migrants have VERBed]/[refugees are VERBing]/[*migrants are VERBing].3 The four constructions cross referential nominal (refugees vs. (im)migrants) with grammatical aspect (perfective vs. imperfective). This was motivated by previous research showing that the categories denoted by refugee and (im)migrant are constructed differently in media discourses where they have distinct sets of verbal collocates (Gabrialetos and Baker, 2008). We may therefore expect to find differences in the images associated with refugees versus migrants. Likewise, perfective versus imperfective aspects are shown to encode event-external versus event-internal perspectives, respectively, with correlates in co-verbal forms (Duncan, 2002; Parrill et al., 2013; Denisova et al., 2018) and consequences for legal and political judgments (Fausey and Matlock, 2011; Sherrill et al., 2015).

Frequency lists for the verbs occurring in each construction were generated. Motion verbs featuring in the top twenty of each list were then totaled with the six overall most frequent motion verbs being selected for analysis. The six motion verbs were flee, flood, pour, enter, arrive and cross which returned a total of 729 hits.

The data was then filtered to remove any cases that could be considered noise. 126 clips were excluded for one of the following reasons: they were duplicate clips; they involved a double nominal (e.g., refugees and migrants have VERBed); there was a mismatch between the construction in the closed caption and the one in the actual video clip; the clip belonged to an alternative genre than TV news; there was a misalignment between the closed caption and the time-stamp in the clip resulting in a false hit or the link to the clip was broken; the clip contained a multi-image (more than two) or montage of images or the image in the clip was unclear. Of the remaining 603 clips, 78.6% included images co-timed with the target phrase resulting in a final sample of 474 clips. By images here I mean any embedded visual that is on screen at the moment the target phrase is produced. This includes photographs and graphic illustrations within the TV studio setting (e.g., on a screen behind the news reporter) and video footage of scenes outside of the studio setting which the camera cuts to. In the case of videos, the unit of analysis is the frame coinciding with the verb as the nucleus of the construction and the sequence surrounding it.

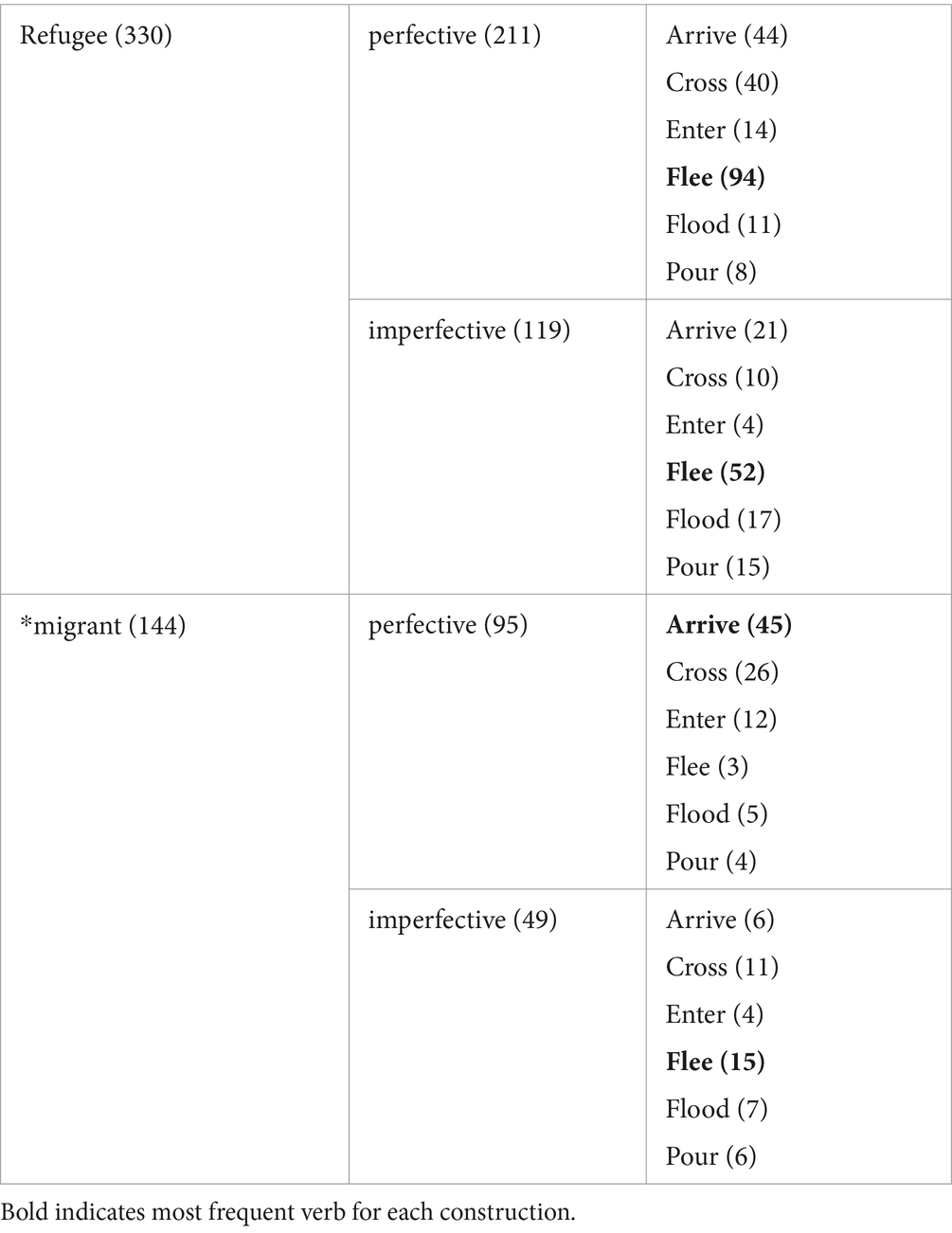

2.3 Data characterization

Table 1 shows a breakdown of the data by referential nominal, grammatical aspect and verb. The most frequent verb in each construction is shown in bold. The term refugee occurs more frequently than (im)migrant accounting for 69.6% of all cases. The most frequent verb in the data is flee (n = 164) which occurs significantly more frequently with refugee than it does with (im)migrant (χ2 = 44.6405, p < 0.001). Arrive is the second most frequent verb (n = 116) followed by cross (n = 87), flood (n = 40), enter (n = 34) and pour (n = 33). There are almost twice as many instances of the perfective construction (n=306) as there are the imperfective (n=168) with no marked difference in frequency of use between referential nominals. Images are categorized as still photographs, videos or graphic illustrations. Videos are the most frequent image-type (n = 323) accounting for 67% of all visuals. Photographs are the second most frequent (n = 105) followed by graphic illustrations (n = 54). Note that eight images were split images and were therefore coded twice.

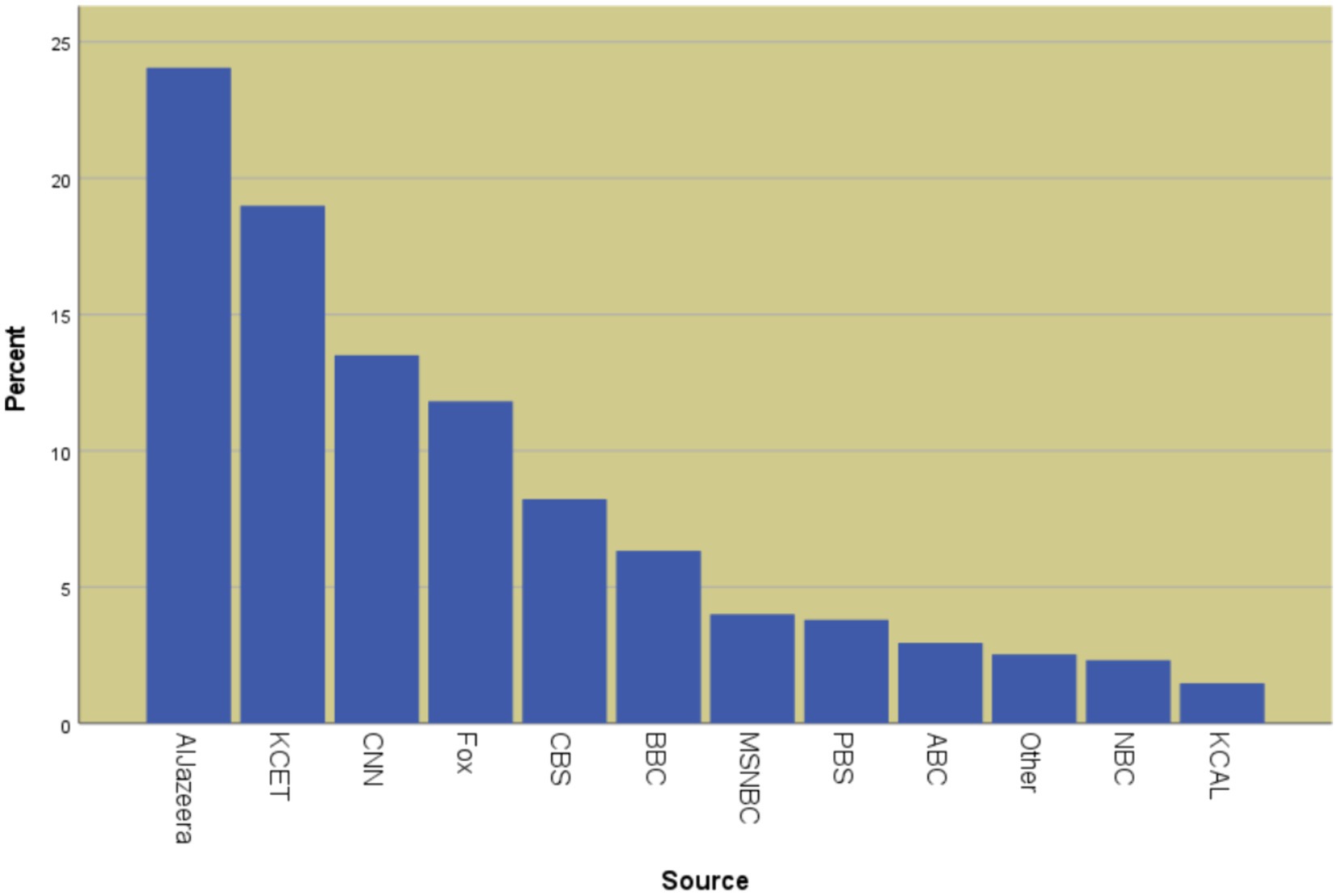

The NewsScape Library ingests material from national and cable television networks in the US as well as international sources including the BBC. Figure 1 shows the distribution of hits by the major media outlets represented in the data. The top half of the most represented sources includes AlJazeera, KCET, CNN, FOX, CBS and BBC which together account for 63.9% of all hits returned.

2.4 Data coding

Motivated by previous research investigating the visual representation of migration, co-verbal images in the final sample were coded according to the following scheme:

- Presence: are refugees/migrants depicted in the image or not

- Size: are depicted refugees/migrants shown in small groups (<8 people) or large groups (>8 people)

- Source-path-goal: does the image include a concrete depiction of the country of origin (source), the migratory journey itself (path) or the ultimate destination country (goal)

- Path: if shown on the migratory journey, are refugees/migrants depicted in transit or in situ (e.g., in camps, held at borders, resting)

- Mode: if shown in transit, are refugees/migrants depicted on land or at sea

- Security: does the image present a security context (e.g., presence of security walls or fences, police, or military personnel)

- Number: are numbers displayed visually as part of the image

A randomized 20 % of the data was coded by a second non-expert coder (excluding the variable number which emerged as relevant only later in the analysis). A non-expert coder was used to ensure interpretive alignment between the analyst and a lay audience thus enhancing the ecological validity of the study. An overall kappa score of 0.673 indicates a substantial level of agreement between coders. However, it is worth noting some variation between the six second-coded variables which ranged from moderate to almost perfect levels of agreement: presence (0.825), size (0.743), source-path-goal (0.596), path (0.507), mode (0.807) and security (0.558). Discussion with the second-coder identified some misunderstandings of the coding scheme for lower scoring variables. For example, images of destination countries that did not also feature refugees/migrants were not coded as goal images. All issues were clarified to the satisfaction of the second coder before proceeding to the analysis with the original coding.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Size

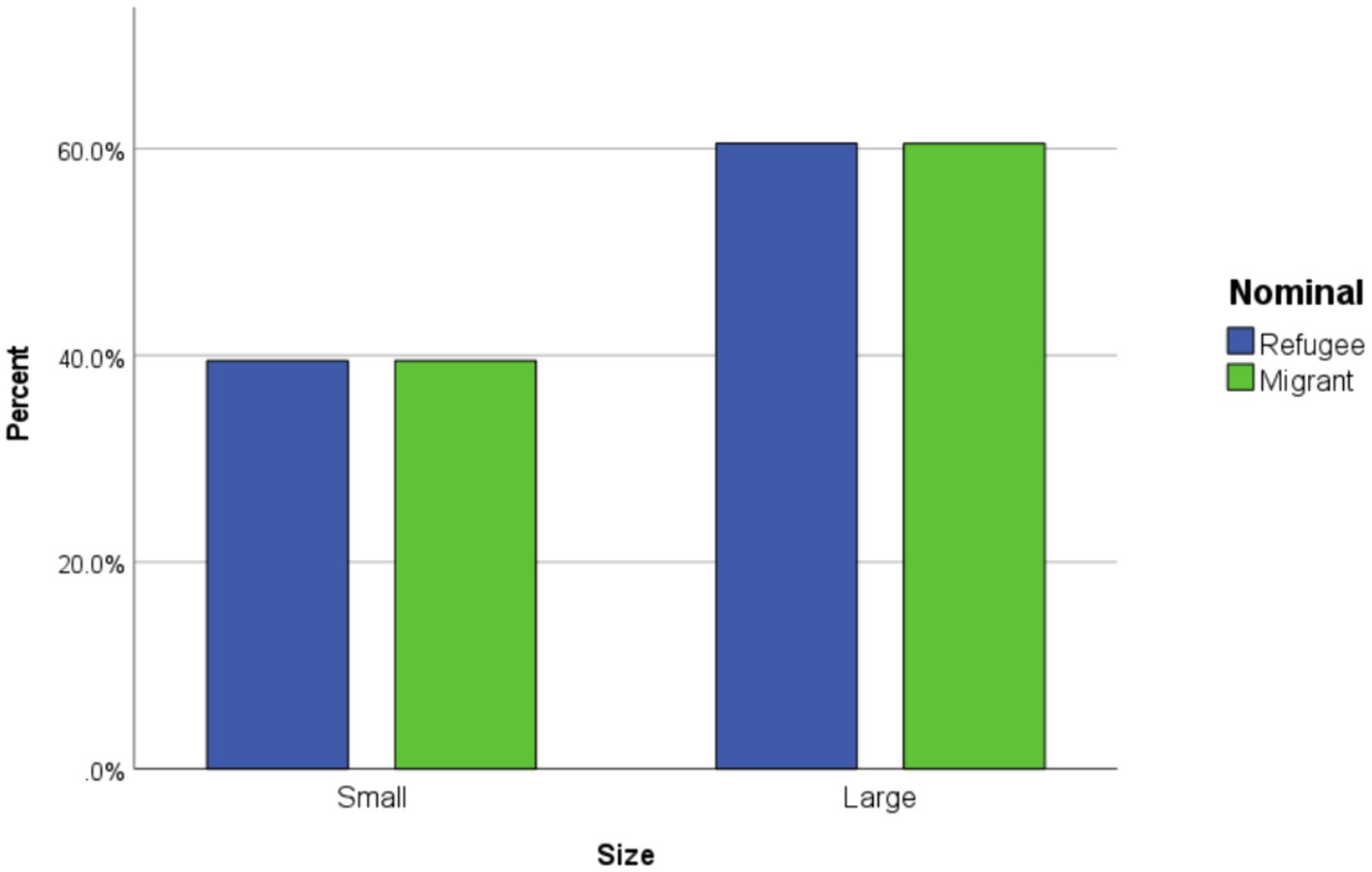

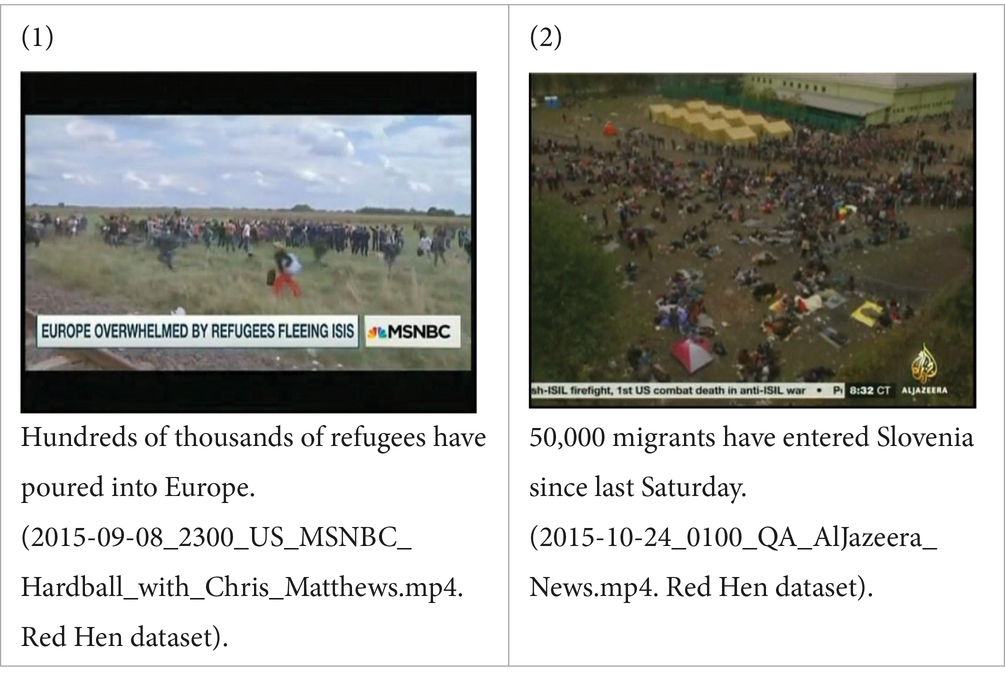

Refugees and migrants receive concrete visual representation in 74.3% of images (n = 352). Images showing refugees and migrants were classified as depicting small versus large groups of people. Following Azevedo et al. (2021), small groups were defined as groups comprising fewer than eight people whose facial features were clearly recognizable. Large groups were defined as those of eight or more people whose facial features could not be easily discerned. Consistent with previous findings for online and print news media (Martínez Lirola, 2016; Wilmott, 2017), refugees and migrants are depicted more often in large groups (60.5%) than small groups (39.5%). An exact binomial test confirms that this difference is statistically significant assuming 0.5 proportions (p < 0.001). As shown in Figure 2, the result applies to both nominal categories. It is also the case regardless of grammatical aspect or verb and goes for all media sources.

Viewpoint was not included as a variable in the initial data coding owing to its complex dimensionality (Hart, 2015) as well as its dynamicity in video images. However, the visual depiction of large groups is often concomitant with a distal viewpoint, which may either be from on the ground as in (1) or aerial as in (2). Van Leeuwen (2005: 138) argues that “in pictures, distance becomes symbolic” where it “indicates the closeness, literally and figuratively, of our relationships.” The long-distance shot presented by examples like (1) and (2), as Wilmott (2017: 74) points out, “creates distance between the refugees and the viewer and highlights their ‘otherness’.” Long-distance shots of large and faceless groups, moreover, serve to de-individualize and anonymize refugees and migrants making it easier to ignore their individual motives for migrating and to accept actions and policies that will be harmful to them.

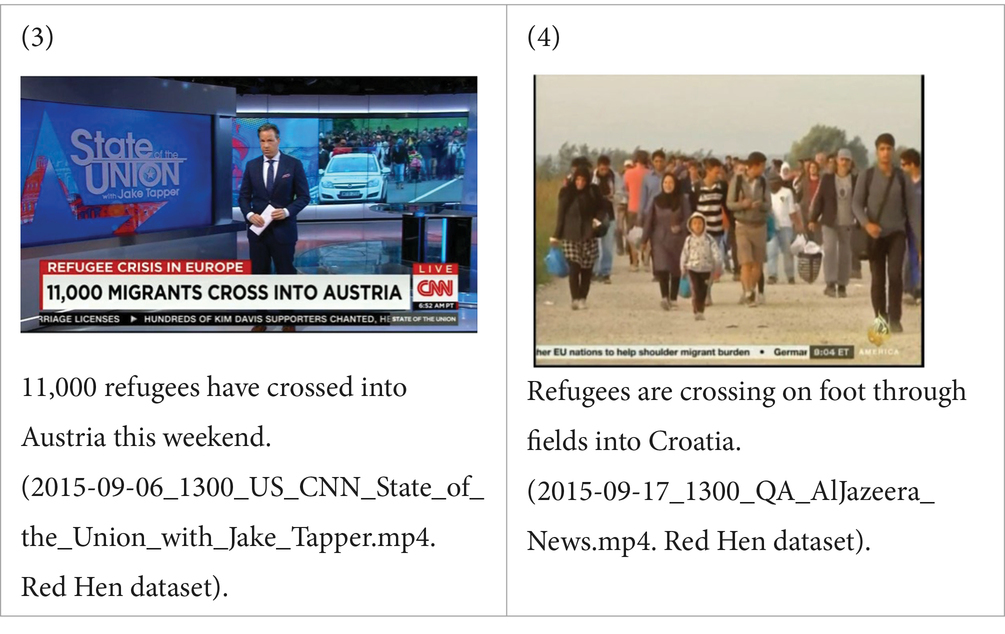

A particularly common pattern of visual representation shows refugees/migrants in large groups moving on foot in line formation as in (3) and (4). In such images, refugees and migrants are unitized as a single moving mass. The image is consistent with imagery evoked by both bovine metaphors, which ascribe herd-like qualities to refugees/migrants, and water metaphors, which liken them to a mass of water such as a river. Angle is another ideologically significant dimension of viewpoint (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006). The frontal angle presented by (3) and (4) realizes a visual proximization strategy (Cap, 2013) as the mass is shown moving toward the viewer thus creating the sense of an impending threat or problem.

A closely related pattern, seen in (5) and (6), involves a large unbounded line of refugees/migrants moving continuously past the viewer so that at every stage in the sequence the viewing frame is occupied by new people. The images in (5) and (6) thus present an event-internal perspective with neither the beginning nor the endpoint of the line included in the sequence. In such examples, perspective and state of boundedness work together to imply a current, enduring and indefinite situation.

Large groups are also shown in scenes of chaos as in (7) and (8) with the extreme close-up shot in (8) placing the viewer in the midst of the chaos. By contrast, when small groups are depicted, they are shown in calmer situations, including medical contexts as in (9) or just waiting/resting as in (10). Small group depictions identify refugees and migrants as individuals and thus recognize their personal plight. Where women and children are underrepresented in visual discourses of migration with the default image being of large male groups (Banks, 2012; Martínez Lirola and Zammit, 2017; Olier and Spadavecchia, 2022), small groups are often specifically identifiable as a family that includes women and young children as in (10). Small group depictions tend to coincide with a more close-up shot which in this context connotes familiarity as opposed to otherness.

Size matters because people express greater empathy and willingness to help in situations involving specific individuals than those involving larger, vaguer groups, a phenomenon known as the identifiable victim effect (Jenni and Lowenstein, 1997; Lee and Hugh Feeley, 2016). By contrast, it is argued that images showing people in large groups lead to decreased perceptions of vulnerability (Bleiker et al., 2013) and psychic numbing effects (Slovic, 2007). Azevedo et al. (2021) show that large group depictions produce dehumanizing effects where refugees/migrants shown in large groups are judged as less capable of experiencing human emotions like tenderness, guilt and compassion.

3.2 Source-path-goal

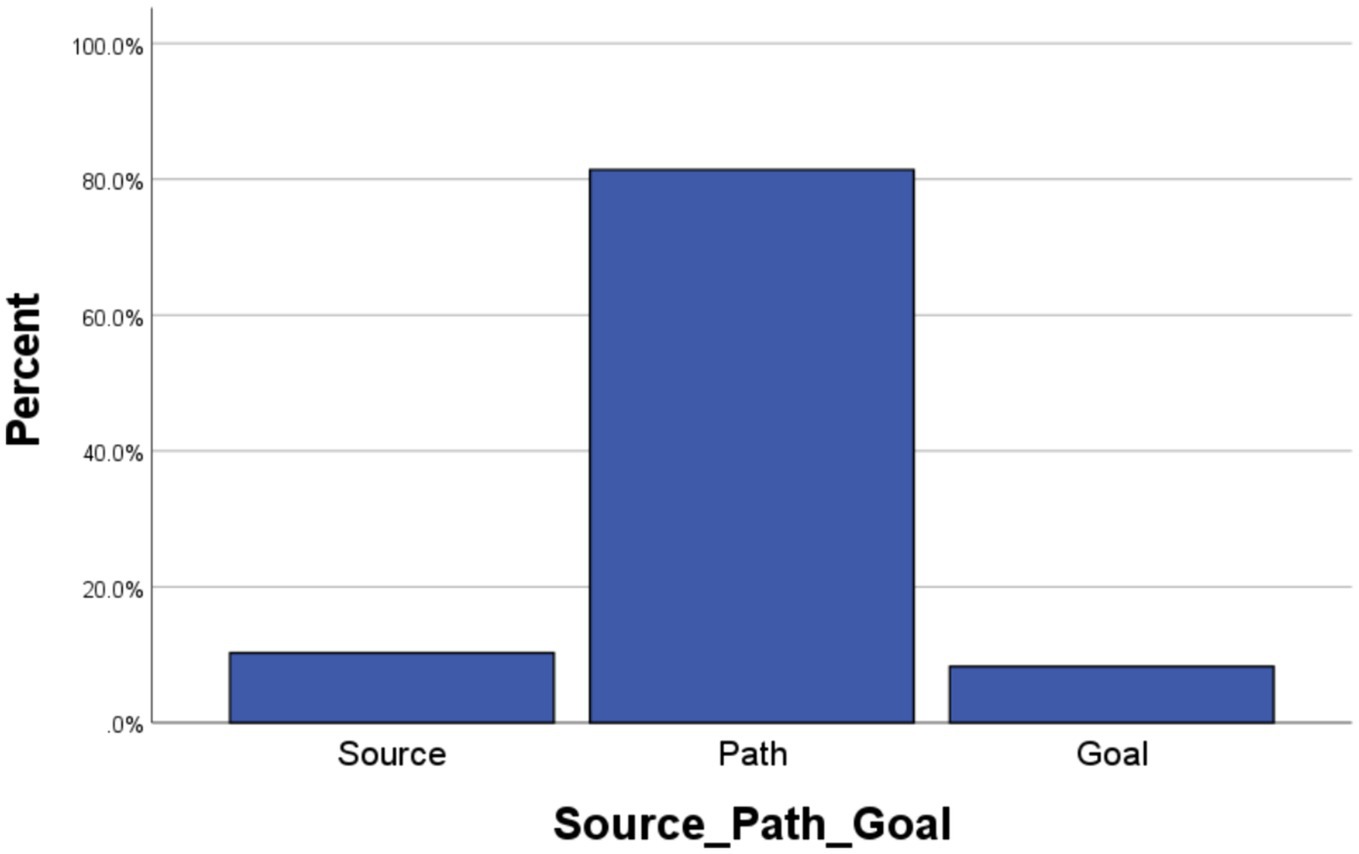

The translocational process of migration involves three conceptual locations: (i) a source as the country of origin; (ii) a path as the series of locations along the migratory journey including camps, borders and resting places; and (iii) a goal as the ultimate destination country. Images window attention on particular stages of this process (Hart and Marmol Queralto, 2021; Romano and Dolores Porto, 2021). As shown in Figure 3, in images where a concrete physical location is clearly represented and identifiable (n = 398) this is more frequently a path location (81.4%) than it is a source (10.3%) or goal (8.3%) location. The result is statistically significant based on an exact binomial test assuming equal distributions (p < 0.001). These results mirror findings for online newspapers (Romano and Dolores Porto, 2021) and confirm the media’s interest in the middle stage of the migration process. The focus on path locations as in examples (1) to (10) fails to draw attention to the circumstances that lead to displacement, such as poverty, violence and war.

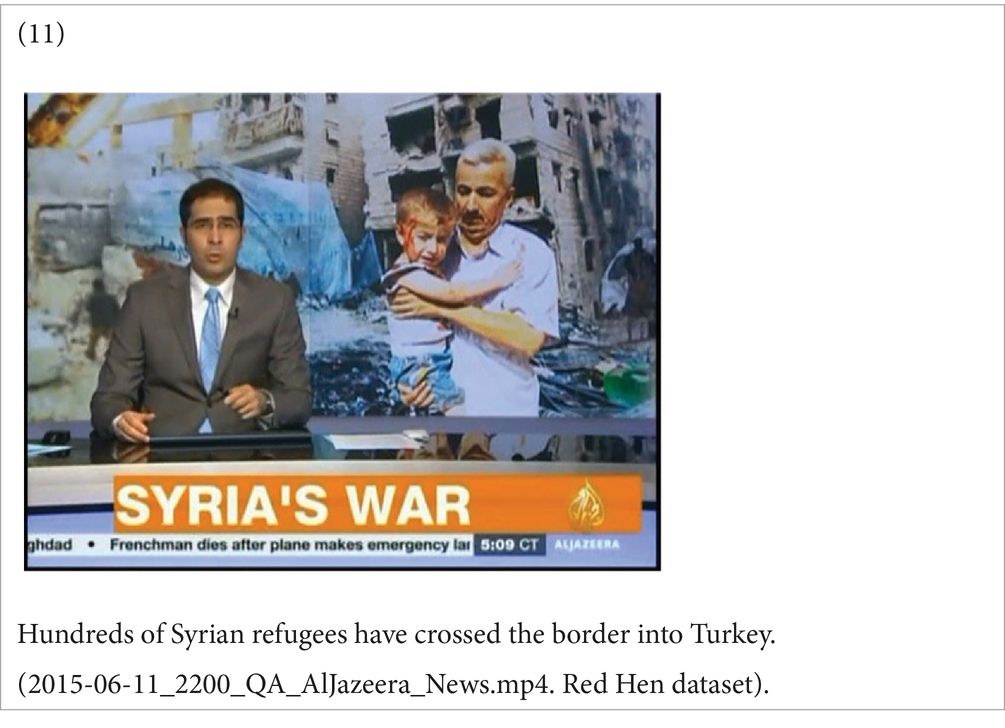

An example depicting a source location is provided by (11) which in the background shows the destruction to buildings caused by the war in Syria. Worth noting is that in 95.1% of cases where a source location is shown, this is in connection with the nominal ‘refugee’ rather than ‘(im)migrant’ (χ2 = 16.087, p < 0.001). Similarly, and expectedly given the association between refugee and flee, source depiction also occurs significantly more frequently with ‘flee’ (70.7%) than it does with any other verb (χ2 = 34.847, p < 0.001). Since flee inherently implies an unsafe or dangerous situation from which someone removes themselves, this indicates a slightly greater willingness to tell the backstory, in multimodal form, of people designated as ‘refugees’ compared to those designated as ‘(im)migrants’.

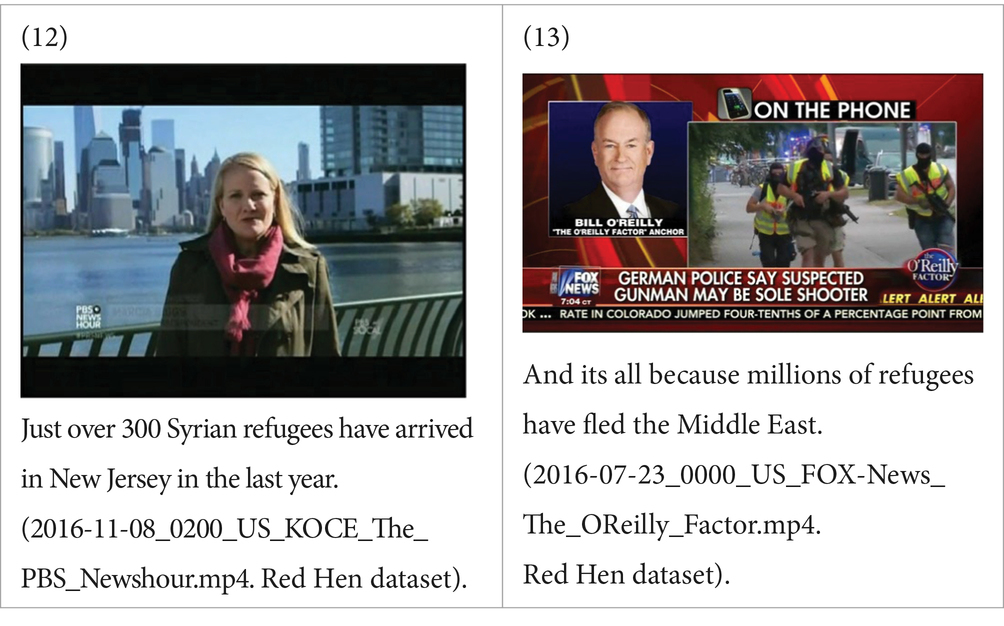

The focus on path locations equally fails to show refugees and migrants settled into a new life in the destination country, which would present a positive immigration story. Indeed, when the destination country is shown (n = 33), refugees and migrants are not part of the picture in 48.5% of cases. Images instead show either a cityscape or landscape in an anchored news report (36.4%) as in (12) or the aftermath of terrorism (12.1%) as in (13) where it is implied that immigration is to blame for terrorist attacks.

Where the perfective construction describes an event as having completed and the imperfective construction describes an event as ongoing, perfective and imperfective aspect might have been expected to correlate with goal and path images respectively. However, this was not the case (χ2 = 2.420, p = 0.298 ns). This could be owing to the low number of goal images failing to reliably show any correlations. However, another possible explanation is that the two semiotic modes are functioning differently. While perfective aspect in the verbal mode presents a specific event as having completed, the visual mode serves to frame the event as part of a more general situation that continues to endure.

Depicted on the migratory journey, refugees and migrants are represented more frequently in transit (70.7%) than they are in situ (20.3%) (p < 0.001). That is, they are shown on the move more than they are shown resting, in camps or being held at borders.

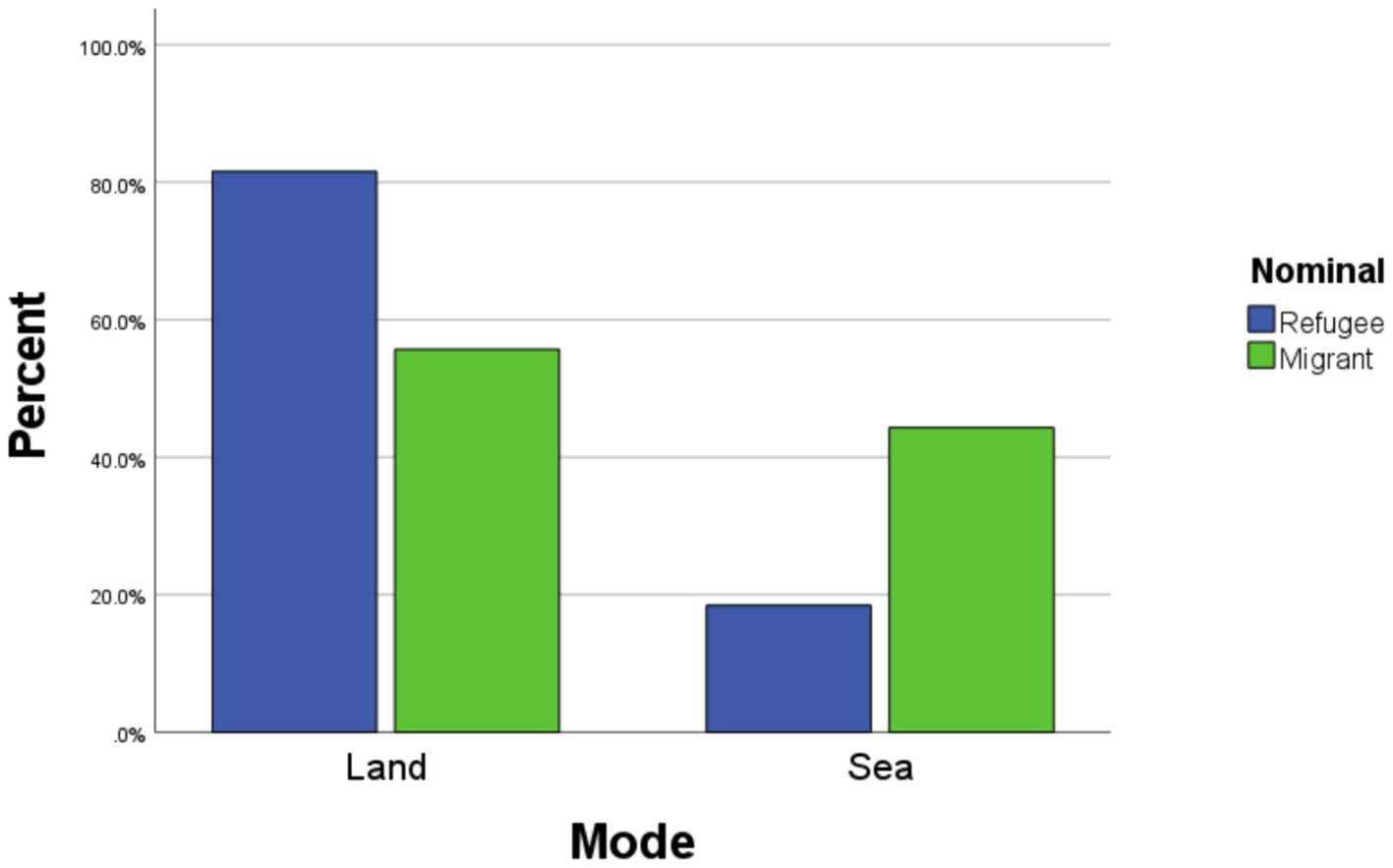

As shown in Figure 4, they are depicted in land-based transit (i.e., on foot, on buses or on trains) (71.6%) more frequently than sea-based transit with ‘refugees’ being particularly strongly associated with land-based modes (χ2 = 18.503, p < 0.001). The main result is significant based on an exact binomial test (p < 0.001). Nevertheless, images of refugees and migrants at sea as in (14) and (15) account for 28.4% of path images.

Azevedo et al. (2021) show that seeing large groups in a sea context further amplifies dehumanization effects. Sea-based images also increase perceptions of realistic threat (i.e., threat to the in-group’s economic or political power or physical well-being) while land-based images increase perceptions of symbolic threat (i.e., threat to the in-group’s norms, values and culture) (Azevedo et al., 2021). Images of refugees and migrants arriving by sea at night as in (15) in particular contribute a sense of clandestinity and illegality (Martínez Lirola, 2022: 488).

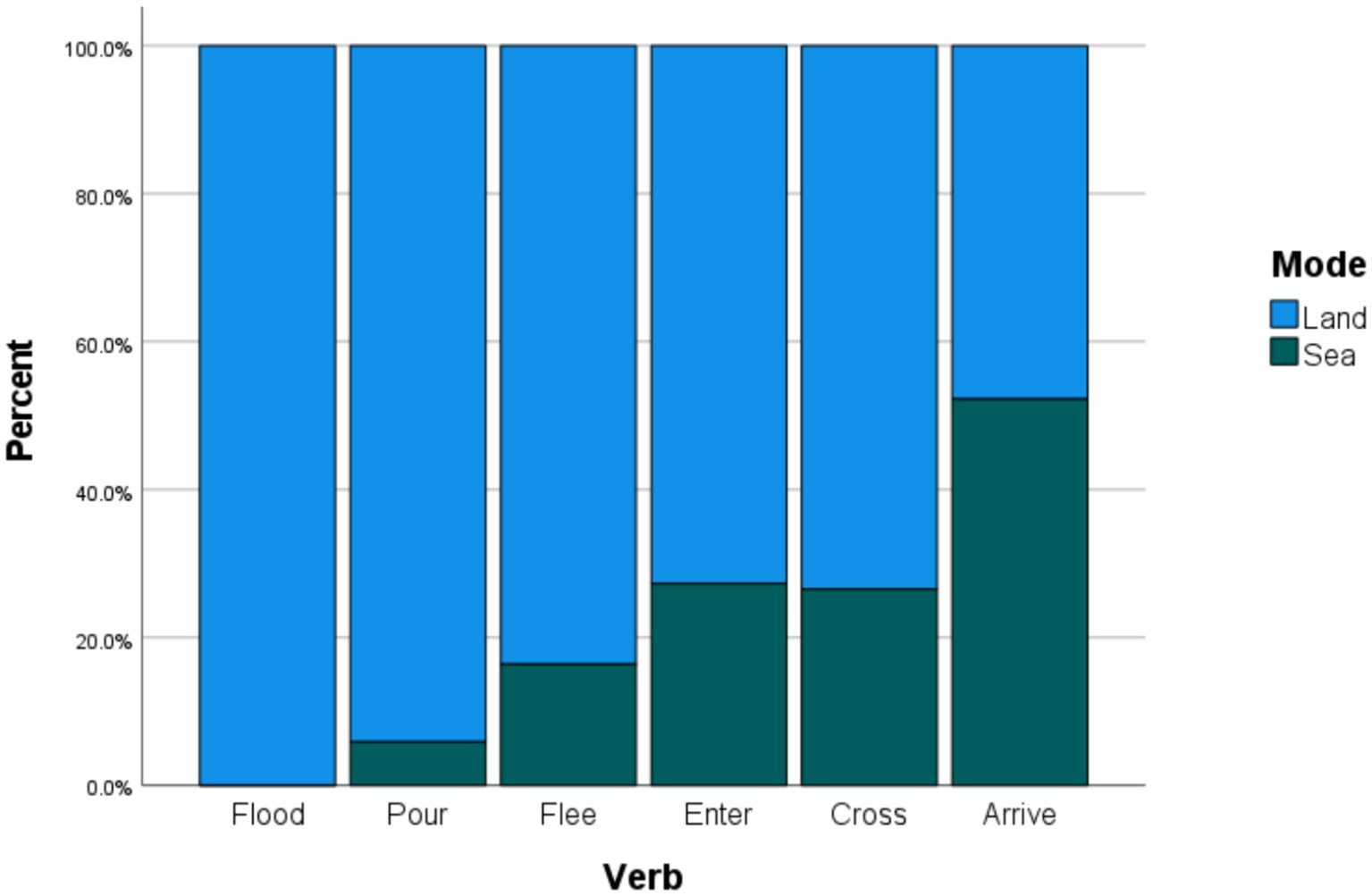

Sea images might be expected to occur most frequently with verbs flood and pour which provide a water-based metaphorical framing of migration (El Refaie, 2001; Santa Ana, 2002; Charteris-Black, 2006; Abid et al., 2017; Dolores Porto, 2022). Language and image would then be intersemiotically convergent (Hart and Marmol Queralto, 2021) in indexing the semantic element of water in each mode. In fact, however, water-related verbs flood and pour are the least associated with sea images, with flood (n = 13) occurring exclusively with land images and pour (n = 17) occurring with land images in 94% of cases (see Figure 5). It is in the context of arrive (n = 67) where sea images occur most frequently (52.3%) (χ2 = 32.553, p < 0.001). One explanation for this is in terms of functional redundancy. Since land and sea images connote different types of threat, there is a rhetorical payoff in evoking water and land-based imagery simultaneously in distinct modes but a redundancy in providing the same information twice. An alternative reason why water verb + sea image combinations are not found may be that the presence of literal water in sea images, rather than strengthening the water-based framing presented in the verbal mode, would in fact defeat the figurative evocation of the frame. In either case, the result shows that in multimodal texts representations in different modes are not just reduplications of one another but rather modes contribute distinct information and interact with one another in various ways to create meanings that are complex and multi-layered (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006).

When shown in situ, refugees and migrants are depicted as passive and devoid of agency as in (9) and (16) and (17) below where the high camera angle in (16) and (17) further contributes to a sense of disempowerment (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006).

In (16), the refugees/migrants are subjugated suggesting the right of more powerful actors to determine their freedom and autonomy. The images in (9) and (17) invite pity and thus contribute to what Chouliaraki (2006) calls a spectatorship of suffering where “simply watching the scene of suffering objectifies the distant misfortune and, as a consequence, may lead to dehumanizing the sufferer” (p.92). This occurs where the suffering is aestheticized and presented as itself a spectacle to behold. As Chouliaraki states, aestheticized suffering “seems to rest on the spectator’s indulgent contemplation of the spectacularity of the scene of human pain” (Chouliaraki, 2006).

3.3 Securitization

One fifth of all images in the corpus (n = 92) depict security contexts, defined by the presence of border walls or fences, police, or military personnel. In such contexts, refugees and migrants are shown either subjugated as in (18) or breaching security measures as in (19).

Images like (19) instantiate a force-dynamic conceptualization in which refugees/migrants are an agonist attempting to overcome a protective barrier in the form of a wall or fence (Dancygier and Vandelanotte, 2017; Hart and Marmol Queralto, 2021). Images of walls and fences are a recurrent visual trope in media discourses of migration (Martínez Lirola, 2016, 2022) where they reinforce a view of refugees and migrants as a dangerous and alien other that exists beyond the wall and who are engaged permanently in an effort to overcome the protective barrier that it provides. As Jones (2012: 25) states, walls and fences entail “a sharpening of discursive distinctions between the people and places on the inside and the evil, dehumanized, and disorderly others who are kept out. They materially and symbolically mark the margins of the exceptional, civilized world and protect it from the perceived anomie on the outside.”

An alternative representation is one where refugees and migrants are absent from the image as in (20) which shows only security officials awaiting their arrival and (13) above which claims to show the aftermath of their arrival.

The presence of security elements serves to criminalize refugees and migrants (Martínez Lirola, 2016) and to construct immigration as a national threat. Images that depict security contexts therefore contribute to a securitization of immigration (Lazaridis and Wadia, 2015; Vezonik, 2018; Kataba and Jacobs, 2023). Immigration is not inherently a security issue but rather, as with other socio-political issues, it becomes a security issue when it is labeled that way by a securitizing actor and when it is accepted as a security issue by a relevant audience (Buzan et al., 1998). Securitization is defined as a process where “through a speech act, the securitising actor labels something as an existential threat to the referent object and argues for the use of extraordinary measures to counter the threat” (Kataba and Jacobs, 2023: 1224). It is not only words that provide securitizing labels, however; images also have a securitizing capacity (Williams, 2003; Hansen, 2011). In immigration discourse, a securitization function is fulfilled by images that include a security presence. Such images are self-prophesying in so far as they serve to further justify the militarization of borders (Catalano and Musolff, 2019). Worth noting is that visual securitization occurs more when the nominal in the construction is migrants (30.6%) than when it is refugees (14.6%) (χ2 = 16.428, p < 0.001), which suggests that when people are designated as refugees they are less likely to be considered a security threat than when they are designated as migrants. Also worth noting in the present data is that visual securitization varies significantly by source (χ2 = 22.008, p < 0.05). For example, Fox News and KCAL images include a security element 35.7 and 42.9% of the time, respectively, while AlJazeera and BBC images include a security element in 13.2 and 3.3% of instances, respectively.

3.4 Erasure

The term “erasure” is used widely in social science contexts to describe the way texts systematically ignore, sideline or otherwise direct attention away from certain groups of people to deny their existence and/or their lived experiences (Namaste, 2000; Stibbe, 2015). In approximately one quarter of images (n = 122), refugees and migrants are omitted from the picture. That is, they are not themselves visually depicted. This erasure occurs through various patterns of representation that include anchored news reports showing locations only as in (12), images showing politicians talking about refugees and migrants as in (21) and visual metonymies (Catalano and Waugh, 2013) in which a vehicle, such as a bus or train, stands in for the people it is transporting as in (22).

The most striking form of representation which serves to erase refugees and migrants, however, is the use of maps as in (23) and (24). In (23), the arrows represent the movement of people through different countries. However, the image is highly reminiscent of media illustrations of battle plans in which similar arrows represent troop movements (Machin, 2007: 60). The image in (23) therefore draws intertextual and interdiscursive links with images in another domain to imply that immigration is like an invasion. This is consistent with verbal metaphors that regularly describe immigration in terms associated with war (Hart, 2021). A recurrent type of map, exemplified in (24), is a heat map. In heat maps, the color red is conventionally used to indicate high intensity and represent the ‘danger zone’. Thus, where specific areas are identified as hotspots, as in (24), it is implied that migration coming from those areas presents a danger.

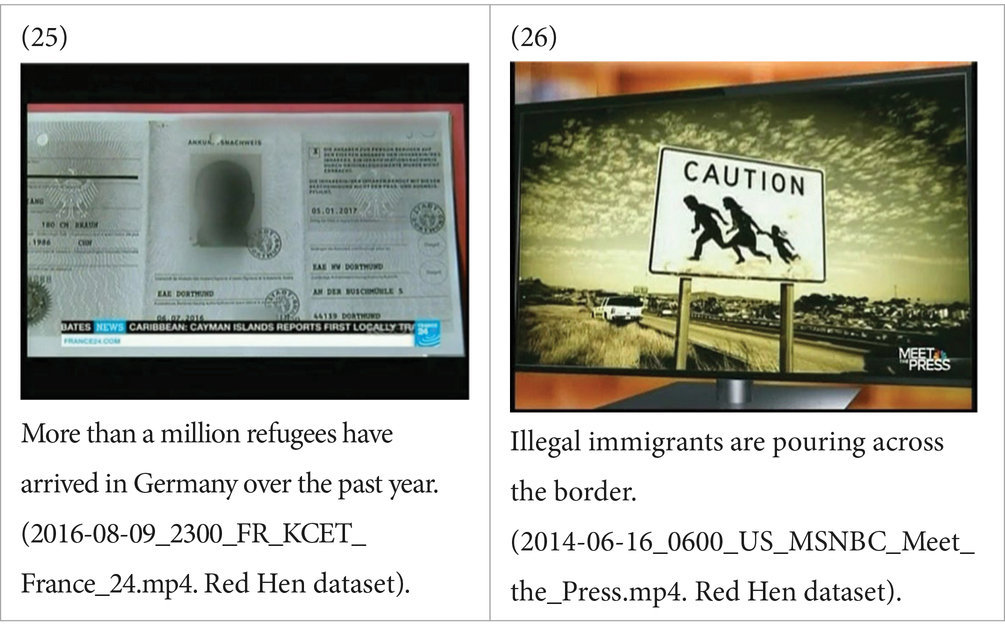

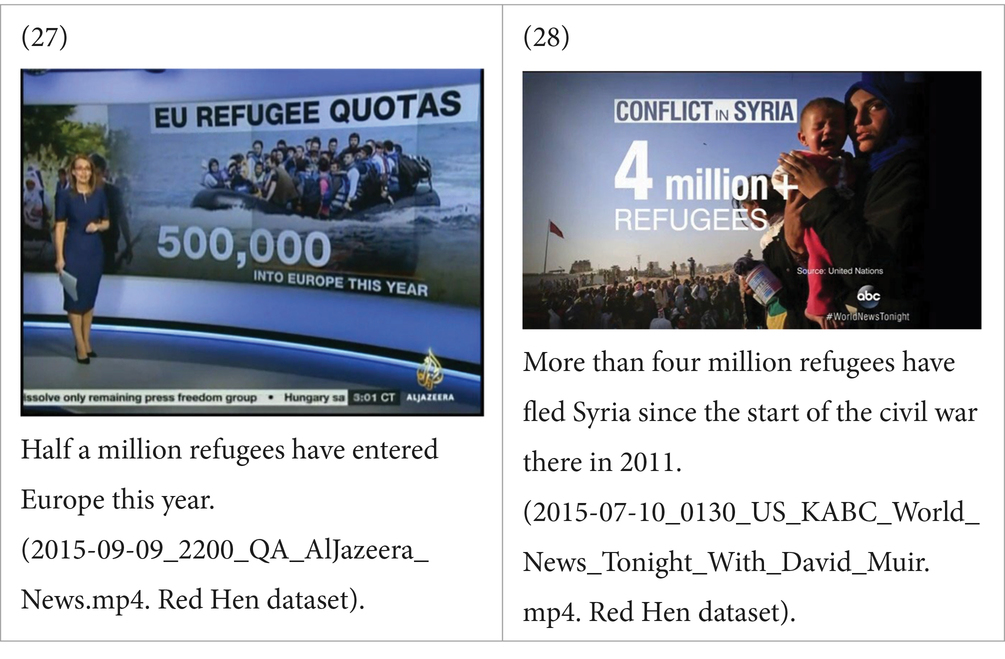

A final form of erasure occurs in images which serve to maintain fear of a mysterious other as in (25) and (26). (25) Presents a further example of visual metonymy where refugees and migrants are represented metonymically through the image of a passport. The passport photo, however, rather than being identifying of a person through human facial features, presents an anonymous and shadowy figure. In (26), refugees and migrants are similarly stripped of human features and represented in silhouette form where they are explicitly constructed as a danger by being framed within a road sign expressing warning. Unlike a conventional road sign, however, where it is the reader of the sign who presents a danger to others and is instructed to take precautions to ensure their safety, the road sign in (26) warns of the danger presented by others and instructs the reader to take precautions to ensure their own safety.

Van Leeuwen (2005: 110) notes that exclusion can have a “distorting effect.” For example, in all instances of erasure discussed above, the image overlooks human suffering and therefore makes it easier to accept or support inhumane circumstances or treatments. Stibbe (2015: 145) argues that the systematic absence of participants communicates that those participants are unimportant, irrelevant or marginal. Chouliaraki (2006: 89) goes further to suggest that such semiotic choices annihilate the sufferers by depriving them of their corporeal and psychological qualities and removing them from the existential order to which the spectator belongs.

Visual erasure occurs significantly more often with the nominal refugee (29.7%) than it does with (im)migrant (16.7%) (χ2 = 8.906, p < 0.01). One explanation for this is that refugees are generally associated more with suffering than migrants. In a hostile media environment, there is therefore a greater need to erase refugees in order to avoid the depiction of suffering and the potential elicitation of sympathy. Conversely, since migrants are generally more associated with crime and economic opportunity there is less cause for their experiences to be erased.

3.5 Number

The final variable to consider is number. Media discourses of migration are pre-occupied with quantification (Gabrialetos and Baker, 2008). This is partly so that refugees and migrants can be presented as coming in numbers which appear large and are therefore alarming and partly because numbers and statistics are a conventional way of emphasizing objectivity and thus enhancing credibility (van Dijk, 2000; Koetsenruijter, 2011). There are different ways of reporting numbers, however. For example, Woodin et al. (2024) show that large numbers tend to get rounded more than small numbers, an observation supported by the present data where numbers are displayed in 7.4% of images (n = 34) and in 82.4% of cases those numbers are expressed as round numbers. The representational format of numbers is also consistent with previous findings which show that numbers in the range 10–999,999 tend to be denoted by numerals while numbers 1 million and above get represented more often in mixed format. In the present data, numbers under 1 million (n = 28) are exclusively presented as numerals as in (27) while numbers of 1 million or above (n = 6), as in (28), are presented in mixed format 83.3% of the time. A Fisher’s exact test confirms that this difference is significant (p < 0.001).

In all cases the same numerical information is co-expressed verbally supporting Winter and Marghetis’ (2023: 2) claim that “for numerical communication, multimodality is the norm rather than the exception.” There are various ways in which semiotic modes may interact with one another in numerical communication but one is “amplification” whereby the same core idea is expressed in multiple modes simultaneously (Winter and Marghetis, 2023). There are several reasons why news producers may choose to amplify a numerical message. For example, as outlined by Winter and Marghetis (2023: 9), it enhances memorability where encoding information into memory via multiple formats leads to better recall, it appeals to the modality-specific attention and retention preferences of individual audience members so that the information is more likely to stick with more people, and it increases the chance that the information will be received by audiences via one mode or another.

4 Conclusion

TV news remains highly influential in the modern media landscape but constitutes an under-investigated area of communication research. This study is the first to conduct a systematic, large-scale investigation of multimodal meaning-making in TV news communication about migration. Such an investigation is made possible by innovations in multimodal corpus design and specifically the NewsScape corpus developed by the Distributed Little Red Hen Lab which this study exploits. The study investigated the co-verbal images that occur alongside the constructions [refugees/(im)migrants have VERBed] and [refugees/(im)migrants are VERBing] where the designation of the verb is a motion event. TV news is found to rely on some of the same patterns of visual representation that are relied on by online and print newspapers and which construct refugees and migrants as a problematic other or else realize a spectatorship of suffering.

The study extends the notion of multimodal constructions, which are defined as conventionalized form-meaning pairings involving complex forms belonging to more than one mode, to verbal + visual combinations rather than verbal + gestural combinations. No threshold for constructionhood was set. However, 78.6% of linguistic constructions in the initial search co-occurred with images suggesting the potential for these units to exist as genre-or discourse-specific multimodal constructions. Repeated patterns of visual representation in co-occurring images further support the multimodal constructional status of these units. The most common pattern of visual representation observed is one in which large groups of refugees or migrants are shown moving on foot over land. The visual component of these multimodal constructions can therefore be taken as comprising imagery abstracted minimally along these lines. Although viewpoint was not coded in the analysis, it nevertheless provides additional layers of meaning and is likely to figure as a semiotic element in the visual components of multimodal constructions. The role of viewpoint in verbal + visual multimodal constructions is therefore an interesting avenue for further research. Besides the default imagery encoded at a constructional level, other multimodal instantiations were also observed which construct immigration as a security issue or which serve to erase the experiences of refugees and migrants. Quantification was also shown to be realized multimodally.

Grammatical aspect did not correlate with any particular distinctions in visual representation suggesting similarities in the visual forms of each multimodal construction. There were, however, some subtle differences between constructions where the referential nominal is refugee compared to (im)migrant. While people designated as refugees and migrants were both depicted significantly more frequently in path locations than source or goal locations, those designated as refugees were more likely to be shown in source locations than those designated as migrants. Similarly, while both categories of people were shown on land more than at sea, those designated as migrants were depicted at sea more often than those designated as refugees. People designated as migrants were also more likely to be shown in security contexts than people designated as refugees while people labeled as refugees were more likely to be erased than people labeled as migrants. While the categories refugee and migrant are largely treated the same way, subtle differences such as these suggest that the two denominations have slightly different frames or semantic profiles which are built by and manifested in co-occurring visual as well as verbal forms.

The study focused on motion events in TV news communication about migration, often identifying parallels with print and online news. Future research could look beyond motion events to explore other important dimensions of migration or beyond migration to investigate in TV news multimodal meaning-making with respect to other topical issues such as political protests. A limitation of the study is that it did not fully account for the affordances of the televisual medium to consider ways in which TV news differs from print and online news. Future research could account for the dynamic nature of TV news to consider, for example, the functions of shifting viewpoints in video images and how they interact with verbal forms or the way images such as graphs provide material anchors in the studio setting which presenters interact with verbally and gesturally in tri-modal acts of meaning-making. Similarly, sound is known to function ideologically (Machin, 2014) and may figure as a further, auditory component of multimodal constructions. Future research could therefore include sound as an ideologically significant semiotic mode. What is clear is that the NewsScape corpus and other TV news corpora now in existence offer rich and exciting opportunities for the systematic, multimodal analysis of TV news communication and there is much research in this area yet to be done.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available and data cannot be shared publicly because the author does not own the copyright of the news clips, which belongs to the Broadcasting corporations that own the shows. In compliance with US Copyright laws, access to these data can be provided to researchers who meet the appropriate criteria. Access can be applied for through the Red Hen Lab which administers the NewsScape corpus from where the data have been extracted. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to https://www.redhenlab.org/.

Author contributions

CH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^http://newsscape.library.ucla.edu/

2. ^https://www.redhenlab.org/

3. ^In the search query syntax of CQPWeb, an asterisk allows optional tokens which in this case will return hits for both migrants and im + migrants. Throughout the paper, I use the less technical form (im)migrants when referring to the search query. When referring to the people designated by these forms, I use the more generic term migrants. Although technically migrants can refer to both emigrants and immigrants, the term migrants was included in the search because it is frequently and conventionally used in reference to immigrants rather than emigrants, for whom other terms like expats are used instead. Other potential terms like aliens, invaders etc. were not included because of their already inherently pejorative status.

References

Abid, R. Z., Manan, S. A., and Rahman, Z. A. A. A. (2017). ‘A flood of Syrians has slowed to a trickle’: the use of metaphors in the representation of Syrian refugees in the online media news reports of host and non-host countries. Discourse Commun. 11, 121–140. doi: 10.1177/1750481317691857

Alaazi, D. A., Ndem Ahola, A., Okeke-lhejirika, P., Yohani, S., Vallianatos, H., and Salami, B. (2021). Immigrants and the Western media: A critical discourse analysis of newspaper framings of African immigrant parenting in Canada. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 47, 4478–4496. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1798746

Alcarez-Carrión, D., Alibali, M. W., and Valenzeula, J. (2022). Adding and subtracting by hand: metaphorical representations of arithmetic in spontaneous co-speech gestures. Acta Psychol. 228:103624. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103624

Antonopoulou, E., and Nikiforidou, K. (2011). Construction grammar and conventional discourse: A construction-based approach to discoursal incongruity. J. Pragmat. 43, 2594–2609. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2011.01.013

Arpan, L. M., Baker, K., Lee, Y., Jung, T., Lorusso, L., and Smith, J. (2006). News coverage of social protests and the effects of phtographs and prior attitudes. Mass Commun. 9, 1–20. doi: 10.1207/s15327825mcs0901_1

Azevedo, R. T., De Beukelaer, S., Jones, I. L., Safra, L., and Tsakiris, M. (2021). When the lens is too wide: the political consequences of the visual dehumanization of refugees. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8:115. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00786-x

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., KhosraviNik, M., Krzyżanowski, M., McEnery, T., and Wodak, R. (2008). A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse Soc. 19, 273–306. doi: 10.1177/0957926508088962

Baker, P., and Levon, E. (2015). Picking the right cherries? A comparison of corpus-based and qualitative analyses of news articles about masculinity. Discourse Commun. 9, 221–236. doi: 10.1177/1750481314568542

Baker, P., and McEnery, A. (2005). A corpus-based approach to discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in UN and newspaper texts. J. Lang. Polit. 4, 197–226. doi: 10.1075/jlp.4.2.04bak

Banks, J. (2012). Unmasking deviance: the visual construction of asylum seekers and refugees in English national newspapers. Crit. Criminol. 20, 293–310. doi: 10.1007/s10612-011-9144-x

Batziou, A. (2011). Framing ‘otherness’ in press photographs: the case of immigrants in Greece and Spain. J. Media Pract. 12, 41–60. doi: 10.1386/jmpr.12.1.41_1

Bleiker, R., Campbell, D., Hutchison, E., and Nicholson, X. (2013). The visual dehumanisation of refugees. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 48, 398–416. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2013.840769

Bucher, H.-J., and Schumacher, P. (2006). The relevance of attention for selecting news content: an eye-tracking study on attention patterns in the reception of print and online media. Communications 31, 347–368. doi: 10.1515/COMMUN.2006.022

Burscher, B., van Spanje, J., and De Vreese, C. H. (2015). Owning the issues of crime and immigration: the relation between immigration and crime news and anti-immigrant voting in 11 countries. Elect. Stud. 38, 59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2015.03.001

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., and de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Cap, P. (2013). Proximization: The pragmatics of symbolic distance crossing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Caple, H., and Knox, J. S. (2015). A framework for the multimodal analysis of online news galleries: what makes a “good” picture gallery. Soc. Semiot. 25, 292–321. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2014.1002174

Catalano, T., and Musolff, M. (2019). “Taking the shackles off”: metaphor and metonymy of migrant children and border officials in the U.S. Metaphorik.de 29, 11–46.

Catalano, T., and Waugh, L. R. (2013). The language of money: how verbal and visual metonymy shapes public opinion about financial events. Int. J. Lang. Stud. 7, 31–60. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2013.813774

Charteris-Black, J. (2006). Britain as a container: immigration metaphors in the 2005 election campaign. Discourse Soc. 17, 563–581. doi: 10.1177/0957926506066345

Cheema, G. S., Hakimov, S., Müller, E., Otto, C., Bateman, J. A., and Ewerth, R. (2023). Understanding image-text relations and news value for multimodal news analysis. Front. Artif. Intell. 6:1125533. doi: 10.3389/frai.2023.1125533

Chkhaidze, A., Buyruk, P., and Boroditsky, L. (2021). Linguistic metaphors shape attitudes towards immigration. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 43.

Chouliaraki, L., and Zaborowski, R. (2017). Voice and community in the 2015 refugee crisis: A content analysis of news coverage in eight European countries. Int. Commun. Gaz. 79, 613–635. doi: 10.1177/1748048517727173

Cienki, A. (2017). Utterance construction grammar (UCxG) and the variable multimodality of constructions. Linguistics Vanguard 3:20160048. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2016-0048

Cisneros, D. J. (2008). Contaminated communities: the metaphor of “immigrant as pollutant” in media representations of immigration. Rhetoric Public Affairs 11, 569–601. doi: 10.1353/rap.0.0068

Conzo, P., Fuochi, G., Anfossi, L., Spaccatini, F., and Onesta Mosso, C. (2021). Negative media portrayals of immigrantss increase ingroup favoritism and hostile physiological and emotional reactions. Sci. Rep. 11:16407. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95800-2

Dancygier, B., and Vandelanotte, L. (2017). Image-schematic scaffolding in textual and verbal artefacts. J. Pragmat. 122, 91–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2017.07.013

Denisova, V. A., Cienki, A., and Iriskhanova, O. K. (2018). Boundary expression in verbs and gesture: differences between L1 and L2 speakers. Computational linguistics and intellectual technologies: papers from the annual international conference “dialogue”. Pp. 163–171. (Komp'juternaja Lingvistika i Intellektual'nye Tehnologii 17 (4)).

Djourelova, M. (2023). Persuasion through slanted language: evidence from the media coverage of immigration. Am. Econ. Rev. 113, 800–835. doi: 10.1257/aer.20211537

Dolores Porto, M. (2022). Water metaphors and evaluation of Syrian migration: the flow of refugees in the Spanish press. Metaphor. Symb. 37, 252–267. doi: 10.1080/10926488.2021.1973871

Duncan, S. (2002). Gesture, verb aspect, and the nature of iconic imagery in natural discourse. Gesture 2, 183–206. doi: 10.1075/gest.2.2.04dun

Ekman, M. (2019). Anti-immigration and racist discourse in social media. Eur. J. Commun. 34, 606–618. doi: 10.1177/0267323119886151

El Refaie, E. (2001). Metaphors we discriminate by: naturalized themes in Austrian newspaper articles about asylum seekers. J. Socioling. 5, 352–371. doi: 10.1111/1467-9481.00154

Farris, E. M., and Silber Mohamed, H. (2018). Picturing immigration: how the media criminalizes immigrants. Politics, Groups Identities 6, 814–824. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2018.1484375

Fausey, C. M., and Matlock, T. (2011). Can grammar win elections? Polit. Psychol. 32, 563–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00802.x

Fozdar, F., and Pedersen, A. (2013). Diablogging about asylum seekers: building a counterhegemonic discourse. Discourse Commun. 7, 1–18. doi: 10.1177/1750481313494497

Gabrialetos, C., and Baker, P. (2008). Felling, sneaking, flooding: A corpus analysis of discursive constructions of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press 1996-2005. J. English Linguist. 36, 5–38. doi: 10.1177/0075424207311247

Geise, S., Panke, D., and Heck, A. (2021). Still images-moving people? How media images of protest issues and movements influence participatory intentions. Int. J. Press 26, 92–118. doi: 10.1177/1940161220968534

Goldberg, A. (2006). Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Graber, D. A. (1990). Seeing is remembering: how visual contribute to learning from television news. J. Commun. 40, 134–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02275.x

Groom, N. (2019). Construction grammar and the corpus-based analysis of discourses: the case of the WAY IN WHICH construction. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 24, 335–367.

Hansen, L. (2011). Theorizing the image for security studies: visual securitization and the Muhammad cartoon crisis. Eur. J. Int. Rel. 17, 51–74. doi: 10.1177/1354066110388593

Hardie, A. (2012). CQPweb – combining power, flexibility and usability in a corpus analysis tool. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 17, 380–409. doi: 10.1075/ijcl.17.3.04har

Hart, C. (2015). Viewpoint in linguistic discourse: space, and evaluation in news reports of political protests. Crit. Discourse Stud. 12, 238–260. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2015.1013479

Hart, C. (2016). The visual basis of linguistic meaning and its implications for CDS: integrating cognitive linguistic and multimodal methods. Discourse Soc. 27, 335–350. doi: 10.1177/0957926516630896

Hart, C. (2021). Animals vs. armies: resistance to extreme metaphors in anti-immigration discourse. J. Lang. Polit. 20, 226–253. doi: 10.1075/jlp.20032.har

Hart, C. (2024). Language, Image, Gesture: The Cognitive Semiotics of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hart, C., and Marmol Queralto, J. (2021). What can cognitive linguistics tell us about language-image relations? A multidimensional approach to intersemiotic convergence in multimodal texts. Cogn. Linguist. 32, 529–562. doi: 10.1515/cog-2021-0039

Hinnell, J. (2018). The multimodal marking of aspect: the case of five periphrastic auxiliary constructions in North American English. Cogn. Linguist. 29, 773–806. doi: 10.1515/cog-2017-0009

Holsanova, J., and Nord, A. (2010). “Multimodal design: media structures, media principles and users’ meaning-making in printed and digital media” in Neue Medie – neue Formate. Ausdifferenzierung und Konvergenz in der Medienkommunikation. eds. H.-J. Bucher, T. Gloning, and K. Lehnen (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag), 81–103.

Jacobs, L., Meeusen, C., and d’Haenens, L. (2016). News coverage and attitudes on immigration: public and commercial television news compared. Eur. J. Commun. 31, 642–660. doi: 10.1177/0267323116669456

Jenni, K. E., and Lowenstein, G. (1997). Explaining the “identifiable victim effect”. J. Risk Uncertain. 14, 235–257. doi: 10.1023/A:1007740225484

Jiminez, T., Arndt, J., and Landau, M. J. (2021). Walls block waves: using an inundation metaphor of immigration predicts support for a border wall. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 9, 159–171. doi: 10.5964/jspp.6383

Jones, R. (2012). Border walls: Security and the war on terror in the United States, India, and Israel. London: Zed Books.

Joyce, N., and Harwood, J. (2014). Improving intergroup attitudes through televised vicarious intergroup contact: social cognitive processing of ingroup and outgroup information. Commun. Res. 41, 627–643. doi: 10.1177/0093650212447944

Kataba, M., and Jacobs, A. (2023). The ‘migrant other’ as a security threat: the ‘migration crisis’ and the securitising move of the polish ruling party in response to the EU relocation scheme. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 31, 1223–1239. doi: 10.1080/14782804.2022.2146072

KhosraviNik, M. (2009). The representation of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in British newspapers during the Balkan conflict (1999) and the British general election (2005). Discourse Soc. 20, 477–498. doi: 10.1177/0957926509104024

KhosraviNik, M. (2010a). Actor descriptions, action attributions, and argumentation: towards a systematization of CDA analytical categories in the representation of social groups. Crit. Discourse Stud. 7, 55–72. doi: 10.1080/17405900903453948

KhosraviNik, M. (2010b). The representation of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in British newspapers: a critical discourse analysis. J. Lang. Polit. 9, 1–28. doi: 10.1075/jlp.9.1.01kho

Koetsenruijter, A. W. M. (2011). Using numbers in news increases story credibility. Newsp. Res. J. 32, 74–82. doi: 10.1177/073953291103200207

Kok, K., and Cienki, A. (2016). Cognitive grammar and gesture: points of convergence, advances and challenges. Cogn. Linguist. 27, 67–100. doi: 10.1515/cog-2015-0087

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Langer, A. I., and Gruber, J. B. (2021). Political agenda setting in the hybrid media system: why legacy media still matter a great deal. Int. J. Press 26, 313–340. doi: 10.1177/1940161220925023

Lazaridis, G., and Wadia, K. (2015). The securitisation of migration in the EU: Debates since 9/11. London: Palgrave.

Leckner, S. (2012). Presentation factors affecting reading behaviour in readers of newspaper media: an eye-tracking perspective. Vis. Commun. 11, 163–184. doi: 10.1177/1470357211434029

Lee, S., and Hugh Feeley, T. (2016). The identifiable victim effect: A meta-analytic review. Soc. Influ. 11, 199–215. doi: 10.1080/15534510.2016.1216891

Lehmann, C. (2024). What makes a multimodal construction? Evidence for a prosodic mode in spoken English. Front. Commun. 9:1338844. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1338844

López, R. M. (2020). Discursive de/humanizing: A multimodal critical discourse analysis of television news representations of undocumented youth. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 28:4972. doi: 10.14507/epaa.28.4972

Machin, D. (2014). “Sound and discourse: A multimodal approach to war film music” in Contemporary critical discourse studies. eds. C. Hart and P. Cap (London: Bloomsbury), 297–320.

Madrigal, G., and Soroka, S. (2023). Migrants, caravans, and the impact of news photos on immigration attitudes. Int. J. Press 28, 49–69. doi: 10.1177/19401612211008430

Marshall, S. R., and Shapiro, J. R. (2018). When “scurry” vs. “hurry” makes the difference: vermin metaphors, disgust and anti-immigrant attitudes. J. Soc. Issues 74, 774–789. doi: 10.1111/josi.12298

Martin Rojo, L., and van Dijk, T. A. (1997). There was a problem, and it was solved! Legitimating the expulsion of ‘illegal’ immigrants in Spanish parliamentary discourse. Discourse Soc. 8, 523–566. doi: 10.1177/0957926597008004005

Martínez Lirola, M. (2016). Linguistic and visual strategies for portraying immigrants as people deprived of human rights. Soc. Semiot. 27, 21–38. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2015.1137164

Martínez Lirola, M. (2022). Critical analysis of dehumanizing news photographs on immigrants: Examples of the portrayal of non-citizenship. Discour. Soc. 33, 478–500. doi: 10.1177/09579265221088121

Martínez Lirola, M., and Zammit, K. (2017). Disempowerment and inspiration: A multimodal discourse analysis of immigrant women in the Spanish and Australian online press. Crit. Approach. Discour. Anal. Across Discipl. 8, 58–79.

Mautner, G. (2005). Time to get wired: using web-based corpora in critical discourse analysis. Discourse Soc. 16, 809–828. doi: 10.1177/0957926505056661

Mautner, G. (2009). “Corpora and critical discourse analysis” in Contemporary Corpus linguistics. ed. P. Baker (London: Continuum), 32–46.

McGlashan, M. (2021). “Linguistic and visual trends in the representation of two-mum and two-dad couples in children’s picture books” in A multimodal approach to challenging gender stereotypes in Children’s picture books. eds. A. J. Moya-Guijarro and E. Ventola (London: Routledge), 268–305.

Mistiaen, V. (2019). “Depiction of immigration in television news: public and commercial broadcasters – A comparison” in Images of immigrants and refugees in Western Europe: Media representations, public opinion and refugees’ experiences. eds. L. d’Haenens, W. Joris, and F. Heindryckx (Leuven: Leuven University Press), 57–82.

Musolff, A. (2015). Dehumanizing metaphors in UK immigrant debates in press and online media. J. Lang. Aggres. Conflict 3, 41–56. doi: 10.1075/jlac.3.1.02mus

Namaste, V. (2000). Invisible lives: The erasure of transsexual and transgendered people. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Nielsen, R. K., and Schrøder, K. C. (2014). The relative importance of social media for accessing, finding, and engaging with news. Digit. Journal. 2, 472–489. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2013.872420

Olier, J. S., and Spadavecchia, C. (2022). Stereotypes, disproportions, and power asymmetries in the visual portrayal of migrants in ten countries: an interdisciplinary AI-based approach. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 9:410. doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01430-y

Omidian Sijani, N. (2023). A corpus-assisted discourse analysis of the representation of Syrian refugees in Canadian newspapers. Discourse Commun. 17, 415–440. doi: 10.1177/17504813231156748

Papathanassopoulos, S., Coen, S., Curran, J., Aalberg, T., Rowe, D., Jones, P., et al. (2013). Online threat, but television is still dominant: A comparative study of 11 nations' news consumption. Journal. Pract. 7, 690–704. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2012.761324

Parrill, F., Bergen, B. K., and Lichtenstein, P. V. (2013). Grammatical aspect, gesture, and conceptualization: using co-speech gesture to reveal event representations. Cogn. Linguist. 24, 135–158. doi: 10.1515/cog-2013-0005

Powell, T. E., De Boomgaarden, H. G., Swert, K., and de Vreese, C. H. (2015). A clearer picture: the contribution of visuals and text to framing effects. J. Commun. 65, 997–1017. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12184

Quinn, S., Stark, P., and Edmonds, R. (2007). Eyetracking the news: A study of print and online Reading. St. Petersburg, FL: The Poynter Institute.

Reisigl, M., and Wodak, R. (2001). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and anti-Semitism. London: Routledge.

Robins, S., and Mayer, R. E. (2000). The metaphor framing effect: metaphorical reasoning about text-based dilemmas. Discourse Process 30, 57–86. doi: 10.1207/S15326950dp3001_03

Romano, M., and Dolores Porto, M. (2021). “Framing CONFLICT in the Syrian refugee crisis: multimodal representations in the Spanish and British press” in Discursive approaches to sociopolitical polarization and conflict. eds. L. Filardo-Llamas, E. Morales-López, and A. Floyd (London: Routledge), 153–173.

Santa Ana, O. (1999). ‘Like an animal I was treated’: anti-immigrant metaphor in US public discourse. Discourse Soc. 10, 191–224.

Santa Ana, O. (2002). Brown tide rising: Metaphors of Latinos in contemporary American public discourse. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Schemer, C. (2012). The influence of news media on stereotypic attitudes toward immigrants in a political campaign. J. Commun. 62, 739–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01672.x

Schemer, C., and Meltzer, C. E. (2019). The impact of negative parasocial and vicarious contact with refugees in the media on attitudes toward refugees. Mass Commun. Soc. 23, 230–248. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2019.1692037

Scherman, A., Etchegaray, N., Pavez, I., and Grassau, D. (2022). The influence of media coverage on the negative perception of migrants in Chile. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:8219. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19138219

Schrøder, K. C., and Kobbernagel, C. (2010). Towards a typology of cross-media news consumption: A qualitative-quantitative synthesis. Nordic J. Media Stud. 8, 115–137. doi: 10.1386/nl.8.115_1

Sherrill, A. M., Eerland, A., Zwaan, R. A., and Magliano, J. P. (2015). Understanding how grammatical aspect influences legal judgment. PLoS One 10:e0141181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141181

Slovic, P. (2007). If I look at the mass I will never act: psychic numbing and genocide. Judg. Decis. Making 2, 79–95. doi: 10.1017/S1930297500000061

Steen, F. F., Hougaard, A., Joo, J., Olza, I., Cánovas, C. P., Pleshakova, A., et al. (2018). Toward an infrastructure for data-driven multimodal communication research. Linguistics Vanguard 4:20170041. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2017-0041

Steen, F., and Turner, M. (2013). “Multimodal construction grammar” in Language and the creative mind. eds. M. Borkent, B. Dancygier, and J. Hinnell (St. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications), 255–274.

Stubbs, M. (1995). Collocations and semantic profiles: on the cause of the trouble with quantitative studies. Funct. Lang. 2, 23–55. doi: 10.1075/fol.2.1.03stu

Taylor, C. (2014). Investigating the representation of migrants in the UK and Italian press: A cross-linguistic corpus-assisted discourse analysis. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 19, 368–400. doi: 10.1075/ijcl.19.3.03tay

Taylor, C. (2021). Metaphors of migration over time. Discourse Soc. 32, 463–481. doi: 10.1177/0957926521992156

Uhrig, P. (2018). NewsScape and the distributed little red hen lab – A digital infrastructure for the large-scale analysis of TV broadcasts. In Zwierlein A-Julia, J. Petzold, K. Böhm, and M. Decker (eds.), Anglistentag 2017 in Regensburg: Proceedings. Proceedings of the Conference of the German Association of University Teachers of English. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

Uhrig, P. (2022). “Hand gestures with verbs of throwing: collostructions, style and metaphor” in Yearbook of the German Cognitive Linguistics Association, vol. 10, 99–120.

Utych, S. M. (2018). How dehumanization influences attitudes toward immigrants. Polit. Res. Q. 7, 440–452. doi: 10.1177/1065912917744897

Valenzuela, J., Cánovas, C. P., Olza, I., and Alcarez-Carrión, D. (2020). Gesturing in the wild: evidence for a flexible mental timeline. Rev. Cogn. Linguist. 18, 289–315. doi: 10.1075/rcl.00061.val

van Dijk, T. A. (2000). “The reality of racism: on analysing parliamentary debates on immigration” in Festschrift für die Wirklichkeit. ed. G. Zurstiege (Dusseldorf: Westdeutscher Verlag).

Van Leeuwen, T., and Wodak, R. (1999). Legitimizing immigration control: A discourse-historical analysis. Discourse Stud. 10, 83–118.

Vezonik, A. (2018). Securitising migration in Slovenia: A discourse analysis of the Slovenian refugee situation. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 16, 39–56. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2017.1282576

Walsh, J. P. (2023). Digital nativism: twitter, migration discourse and the 2019 election. New Media Soc. 25, 2618–2643. doi: 10.1177/14614448211032980

Williams, M. C. (2003). Words, images, enemies: securitization and international politics. Int. Stud. Q. 47, 511–531. doi: 10.1046/j.0020-8833.2003.00277.x

Wilmott, A. C. (2017). The politics of photography: visual depictions of Syrian refugees in U.K. online media. Vis. Commun. Q. 24, 67–82. doi: 10.1080/15551393.2017.1307113

Winter, B., and Marghetis, T. (2023). Multimodality matters in numerical communication. Front. Psychol. 14:1130777. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1130777

Woodin, G., Winter, B., Littlemore, J., Perlman, M., and Grieve, J. (2024). Large-scale patterns of number use in spoken and written English. Corpus Linguist. Linguist. Theory 20, 123–152. doi: 10.1515/cllt-2022-0082

Ziem, A. (2017). Do we really need a multimodal construction grammar? Linguistics Vanguard 3:20160095. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2016-0095

Zima, E. (2017). On the multimodality of [all the way from X PREP Y]. Linguistics Vanguard 3:20160055. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2016-0055

Keywords: multimodality, multimodal constructions, TV News, NewsScape corpus, immigration

Citation: Hart C (2024) Multimodal meaning making in news communication about immigration: using the NewsScape corpus to explore co-verbal images in TV news. Front. Commun. 9:1451105. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1451105

Edited by:

Elena Negrea-Busuioc, National School of Political Studies and Public Administration, RomaniaReviewed by:

Gisela Redeker, University of Groningen, NetherlandsHelton Levy, John Cabot University, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Hart. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christopher Hart, Yy5oYXJ0QGxhbmNhc3Rlci5hYy51aw==

Christopher Hart

Christopher Hart