- 1Infectious Diseases Institute, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda

- 2Local Government, Hoima, Uganda

- 3Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Gulu University, Gulu, Uganda

- 4Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom

Background: The language used in research and health programs is crucial in influencing participation and ensuring the acceptability of programs and the adoption of research outcomes. The use of alienating language may present a barrier for research participants hence the need to identify accurate, respectful, relevant, and acceptable terms for respective study populations. The study explored commonly used terminologies during research involving pregnant and lactating mothers using public engagement and participatory approaches in Uganda.

Methods: A cross-sectional qualitative study was conducted in August 2023 among 5 ethnically diverse communities with different languages and from different regions across Uganda. Data were collected through 18 focus group discussions (FGDs) comprising community members and one comprising the community advisory board (CAB) using a participatory approach. An interview guide exploring perceptions and experiences on research, common and preferred terms for specific terminologies used among pregnant and lactating mothers as well as disliked words guided the discussion. Transcription was done verbatim in English. Nvivo version 14 software was used to organize and manage the data appropriately based on themes and subthemes.

Results: A consensus on the preferred terminologies to communicate about our research studies involving pregnant and lactating mothers was reached. The study revealed that words used in research that did not specify sex were described as disrespectful, inappropriate or confusing. Language defining a person on the basis of anatomical or physiological characteristics was considered ‘embarrassing’ and labelling individuals based on their conditions was construed as stigmatising. Participants recommended that researchers be mindful of any terms that could be perceived as embarrassing or inappropriate within the community, ensure clear communication of research terms to participants, and train healthcare workers on the use of appropriate health language. The importance of providing feedback regarding study findings was emphasised.

Conclusion: The findings highlight the importance of using culturally sensitive language in health research to improve engagement and participation. By adopting community-preferred terms, researchers can avoid confusion and stigma fostering respectful health communication. The findings offer guidance for future research, advocating for community-driven inclusive language in research involving pregnant and breastfeeding women. For healthcare workers, training in empathetic communication and cultural competence is crucial to improve patient interactions and promote dignity in healthcare settings.

Background

Research must be undertaken in the communities that are the intended beneficiaries of the research findings. This requires consideration of equity of access to research. Many aspects of the research process require linguistic understanding: ‘plain language’ and ‘lay’ summaries of research (Stoll et al., 2022), and media communications of research findings must be clearly understood by the public. In 2018, the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI) which focuses on generating impactful research that translates findings into health policy and practice, particularly concerning infectious diseases, established a Community Advisory Board (CAB) in Kampala. The CAB members provide guidance, feedback, and support to researchers conducting studies within the community and ensure that the perspectives, needs, and values of the community are considered throughout the research (Brockman et al., 2021). The CAB consists of community representatives from; religious groups, local council leaders, cultural leaders, representatives from persons with disability, regional division health inspectors, and peer supporters among others. Members of the CAB ensure that community perspectives are considered at every stage of research from conception through to dissemination. Anecdotally, CAB members have often cited the complexity of scientific and medical terminology (August et al., 2022) used in research related to pregnancy and breastfeeding and emphasized the need for fieldworkers involved in the recruitment process to use simple, accessible language and visual aids in explaining the project. Language preferences described in some guidance documents apply primarily to English speakers in high-income regions such as the United States of America and Europe (Chu et al., 2022). However, some of the recommendations may not be appropriate in regions such as Uganda which are culturally and socioeconomically diverse. It is crucial to understand the preferences of participants and their communities in pregnancy and lactation research to ensure that publications use culturally sensitive, accurate, and acceptable terminology. Efforts to be inclusive could unintentionally introduce barriers, such as reducing inclusivity, dehumanizing individuals, or being inaccurate, making it important to use well-justified language (Gribble et al., 2023). For example, the term “pregnant woman” identifies the subject as a person experiencing a physiological state, whereas “gestational carrier” or “birther” marginalizes their humanity (Gribble et al., 2023). Uganda, like many African societies, often maintains rigid gender roles, especially concerning parenting and family structure. In traditional Ugandan communities, men are seen as breadwinners, while women are celebrated for their motherhood and nurturing of children. In such contexts, the use of gender-neutral language (e.g., “pregnant people” instead of “pregnant women”) might be seen as unnecessary or even inappropriate. A poor choice of words may not only lead to inadequate comprehension of research information but also increase stigma among populations recruited in research studies (Healy et al., 2022). Some terms may be distracting or difficult to understand for readers who come from cultures where there are no apparent non-female lactating people, as well as for people who have low literacy, and for people who are not reading in their native language. In these circumstances, when a term such as “lactating parent” is substituted for “mother” or “breastfeeding mother,” it may not be understood easily, and the use of gender-neutral pronouns creates additional confusion (Bartick et al., 2021). Additionally, the use of alienating language on study-related documents such as informed consent forms may present further barriers and risk disengagement of research participants (Gribble et al., 2022). This study explored how participants described terminologies related to pregnant and lactating mothers in Uganda and identified preferred terms for effective research communication. The findings provide a glossary of culturally respectful, relevant, and clear language that will enhance inclusivity and acceptability in future health research and communication across diverse Ugandan communities.

Methods

From August to November 2023, we conducted a cross-sectional qualitative study. We aimed to determine a consensus on the preferred terminologies to communicate our research studies and to describe perceptions about research terminologies for pregnant and lactating mothers in Uganda. The study population included a selection of community representatives that constitute relevant stakeholders including; community members, research participants, a peer mother, and CAB members. The study utilized a participatory research approach, collaborating closely with the research users to ensure their input into the research that may affect their lives (Cook et al., 2017; Freire, 1999). Additionally, the study prioritized the active involvement of community members in all stages, from design to dissemination (Seward et al., 2021). The involvement of a peer mother (JK) in the study design played a crucial role in informing the team about important considerations for the protocol. Her contributions were essential in refining study tools, such as tailoring informed consent forms to better suit the target community. She also helped in organising FGDs and actively participated in the informed consent process, which was vital in fostering participatory research. Whilst the FGDs were led by trained qualitative research assistants, the consent process was done in partnership with a dedicated community member well conversant with the local language.

Setting

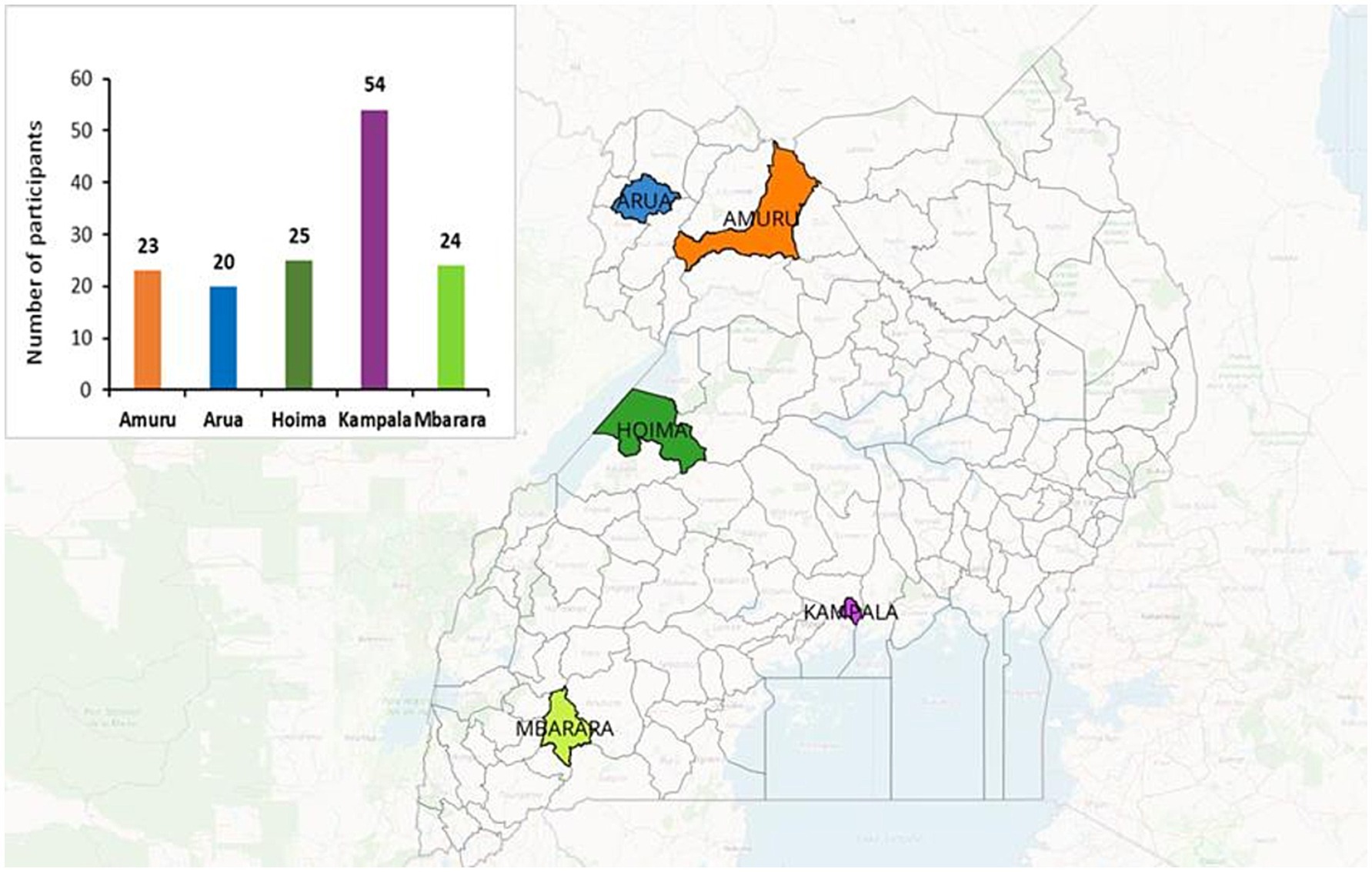

The five communities selected for the qualitative study were based on a selected mixture of both semi-urban and rural communities in Kampala, Mbarara, Hoima, Amuru, and Arua districts, as displayed in Figure 1. This selection was intended to capture a diverse range of perspectives and experiences. These districts were specifically chosen because they had not been heavily involved in prior research and they have more stable populations with less mixing between linguistic groups allowing the study to provide new insights into under-researched areas. This approach ensures a more comprehensive understanding of the linguistic and cultural challenges in health research communication across different community contexts. Also, focusing on districts with stable populations and minimal linguistic mixing helped to capture distinct, culturally specific insights. These areas preserve traditional practices, beliefs, and terminologies related to many aspects of life.

Ethical conduct of the study

We obtained ethical clearance to conduct this study from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI—REC-2023-37) and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (HS2890ES). Also, administrative clearance was sought from the District Health Team, Resident City Commissioners (RDCs), and study participants.

Study team

The study team comprised a peer mother, research assistants, a public engagement officer, a social scientist, research nurses, PhD and postdoctoral research fellows, and a clinical pharmacologist. The peer mother (JK) is a woman with lived experience of being pregnant and breastfeeding whilst receiving medication for a chronic condition and is a core member of the Maternal and Infant Lactation pharmacoKinetics (MILK) study team. The research assistants (RAs) worked closely with the public engagement officer and the peer mother to identify CAB members who were willing to participate in the study. We made inquiries of potential participants by phone and if they showed willingness to participate in the study, we scheduled an appointment with them on the day of the FGD and informed them of the time, place, duration of the FGD, and reimbursement for transportation costs incurred to get to the meeting venue. All participants invited to participate in the study were given adequate information about the study to enable them to make an informed decision about their participation. Participants were identified through engagement with the community networks.

Study design

A comprehensive list of preferred terminologies was generated, incorporating the ideas and experiences of individuals. Specifically, males and females were included to evaluate any differences in the views between the two sexes on these preferred terminologies in research studies involving pregnancy and lactation. The study chose to explore perspectives on desexed language because some international language guides increasingly use this, and we wished to ensure that we employ best practices in our research and explore community perceptions of this language. The study specifically asked how participants would understand phrases such as ‘person with a uterus’, ‘person who menstruates’, ‘birthing parent’, and ‘chest feeding’. Whilst we do not routinely use such terms in Uganda, there has been pressure from journals and some partner organizations to use certain terms in publications, this study was partly motivated by this pressure. We wanted to assess whether language that might be appropriate in specific areas of the world remains appropriate in another area. We believe that at the very least, when reporting research, the language used should reflect the preferences of the communities among whom the research was conducted.

The terminologies were piloted among three focus group discussions conducted in the Hoima district which enabled refinement of the topic guide and showed that the communities were extremely keen to discuss this topic. Furthermore, there was nothing that was considered insensitive about how we were undertaking the study. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were used to gather insights and capture a wide range of participants’ perspectives (Nyumba et al., 2018).

Study procedures

The research was conducted in Uganda in six languages (Luganda, Runyankole, Runyoro, Acholi, Lugbara, and English). All education beyond early years is in English, and many of our research participants prefer English. Moreover, we use English for the majority of our scientific presentations and publications. Luganda was selected since it is the main spoken language in central Uganda where most research is undertaken. Runyoro is a similar Bantu language, but is largely spoken in more rural western Uganda and therefore, has different nuances. The Acholi and Lugbara languages have very different linguistic roots and are more common in rural communities in Northern Uganda, where limited research is conducted. To foster community representation, focus group discussions were held among youth, women, men, former research participants, and CAB members. This paper focuses on the qualitative data collected from this assessment.

Sampling

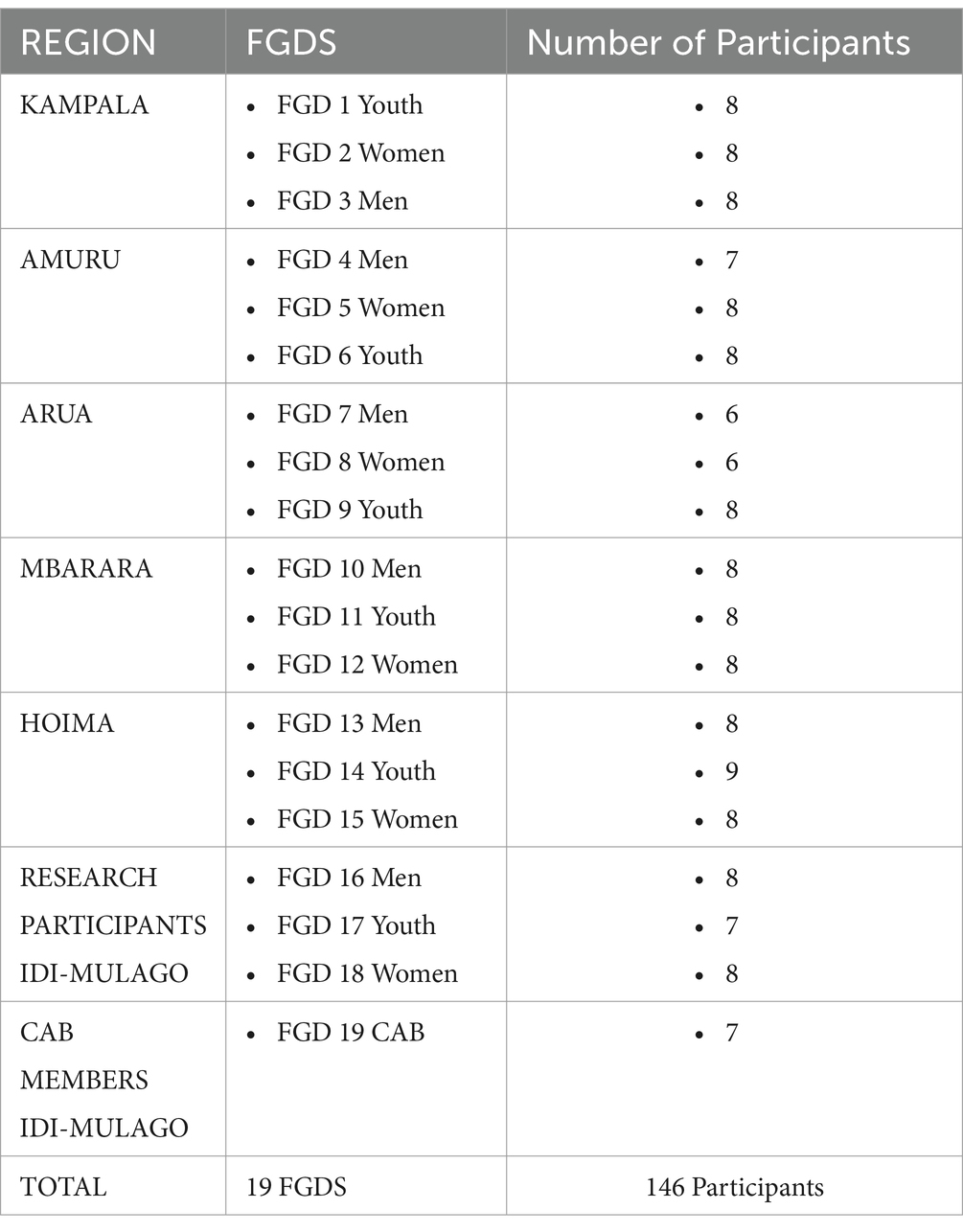

We selected women and men to participate in the 19 FGDs. Participants from the MILK study (Nakijoba et al., 2023) DolPHIN-2 (Malaba et al., 2022) and At The EQUATOR studies who had participated previously in research, but also persons who had never participated were invited to acquire their perspectives. In each region, three separate focus groups were conducted to include; youth (18–24 years), men, and women. The three groups were conducted separately to remove societal hierarchical barriers that may have impeded free participation. The research team identified community locations affiliated with IDI engagements. We selected participants representing at least six languages (Luganda, Acholi, Runyankole, Runyoro, Lugbara, and English). A total of 3 focus group discussions (FGD) at different community sites within each region, comprising between six and nine participants per group who share similar characteristics and experience were selected for inclusion in the study as shown in Table 1. The size of the group was important to ensure that participants had a chance to contribute freely and meaningfully. We purposively selected CAB members who had been involved in the At The EQUATOR and DolPHIN studies. The actual sample size for the qualitative study was determined using the principle of data saturation. Participants were recruited and interviewed until the research team observed that no new information or themes were emerging, suggesting that further interviews were unlikely to yield new insights. This approach ensured that the sample size was sufficient to thoroughly explore all the research questions, capturing the full range of perspectives and experiences relevant to the study topic. Data saturation is a commonly used method in qualitative research to ensure comprehensive and meaningful findings without unnecessary data collection. The process of participant selection was iterative and involved several rounds of selection and interviews to achieve thematic saturation in the first round of the FGDs.

Data collection

Potential participants were invited via a telephone call to participate in this study. Physical meetings were held at their (potential participants’) community locations. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the discussions. Before the start of the focus group, research assistants furnished participants with information on the study to enable them to make an informed decision about whether to continue their participation or not. This included explaining the aims of the study topics that will be covered, confidentiality, benefits, and risks. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured in all the focus groups. This was followed by a signature or thumbprint from each individual who was willing to participate in the study. All FGDs were conducted by at least two researchers, that is, a moderator, and a note-taker. The moderator was the lead person who introduced the research team and explained the research purpose, and objectives of the study. The note-taker ensured that discussions were recorded effectively and that all the paperwork of the focus group was completed with accuracy including the field notes. FGDs lasted approximately 60–90 min. Interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent and later transcribed verbatim from the local language into English for data analysis. Participants sat in a circle to facilitate effective discussion. They were also allocated a unique identification number based on their position in the group circle to ensure that their contribution to the discussion could be identified in the transcripts. The purpose of this study was to single out participants’ contributions to the discussion during the analysis. Demographic information included age, sex, geographic location (in broad terms, whether urban or rural), tribe, mother tongue, additional languages spoken, educational attainment, professional status and income bracket, marital status, number of children (alive or dead) and religion was collected on a questionnaire, administered by the researchers who conducted the focus group discussion. Data collection occurred over 3 months and transcription began as data collection was ongoing.

Data analysis

Quality was ensured throughout the research process and outcomes by adhering to Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) principles of trustworthiness in qualitative research, focusing on credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Data analysis followed an inductive approach, beginning with a thorough review of transcribed focus group discussions (FGDs) to understand the content. A coding framework was developed from 25% of the transcripts, which were manually reviewed and coded by four trained coders. To enhance reliability, coding discrepancies were resolved through discussions aimed at achieving consensus. During discussions, the rationale behind each coding decision was thoroughly examined to reach a consensus. All transcripts were imported into NVivo version 14 for open coding and efficient data management. The revised codes were condensed and labeled, with text segments linked to specific codes. These codes were then grouped into categories, from which themes were identified. Illustrative quotations for each theme were selected to narrate the results.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Among the 146 participants, Kampala had the highest number of participants at (54, 37.0%). The median age of the participants was 31 (with an interquartile range of 24–41). The majority were married (91, 62.3%), 116 (79.4%) had at least one child, and 99 (67.8%) were living in urban areas of Uganda as reflected in Tables 1, 2.

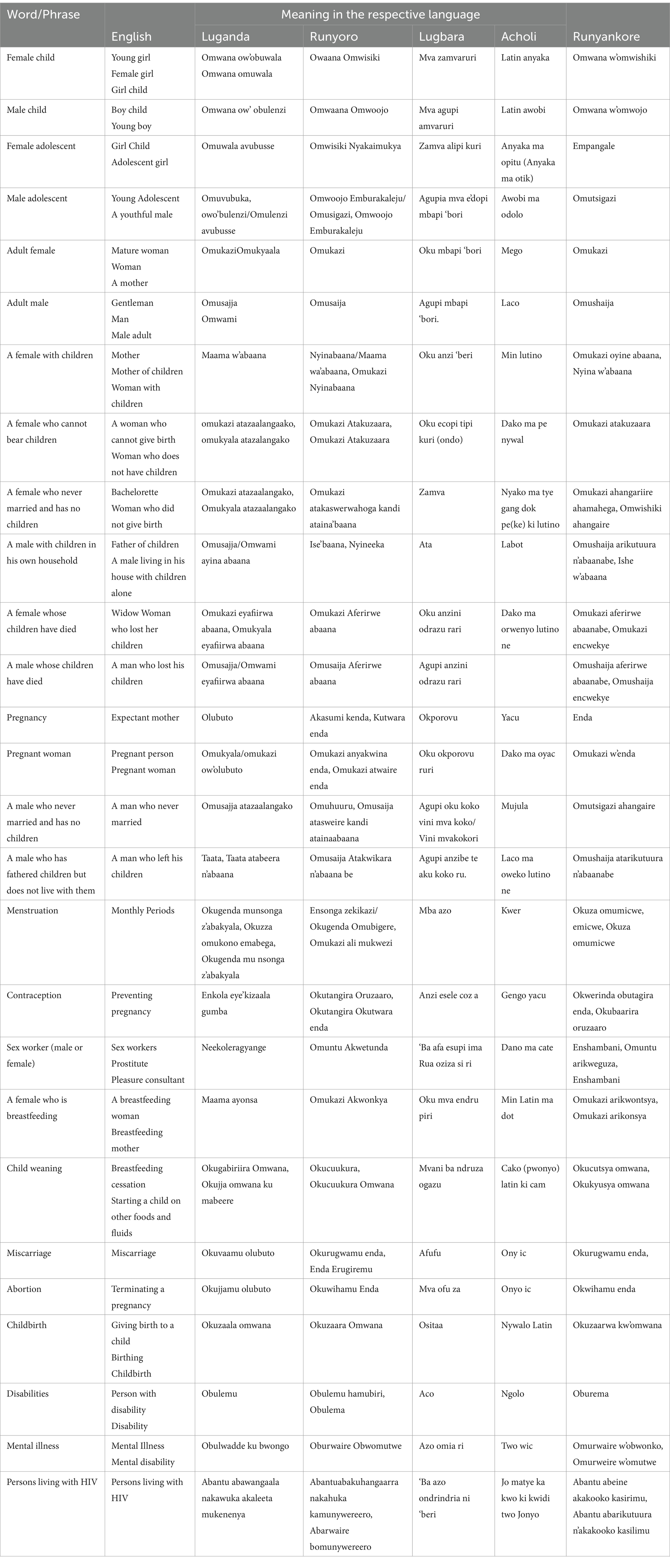

Table 3 shows the preferred terminologies in which to communicate our research studies involving pregnant and lactating women in different six languages.

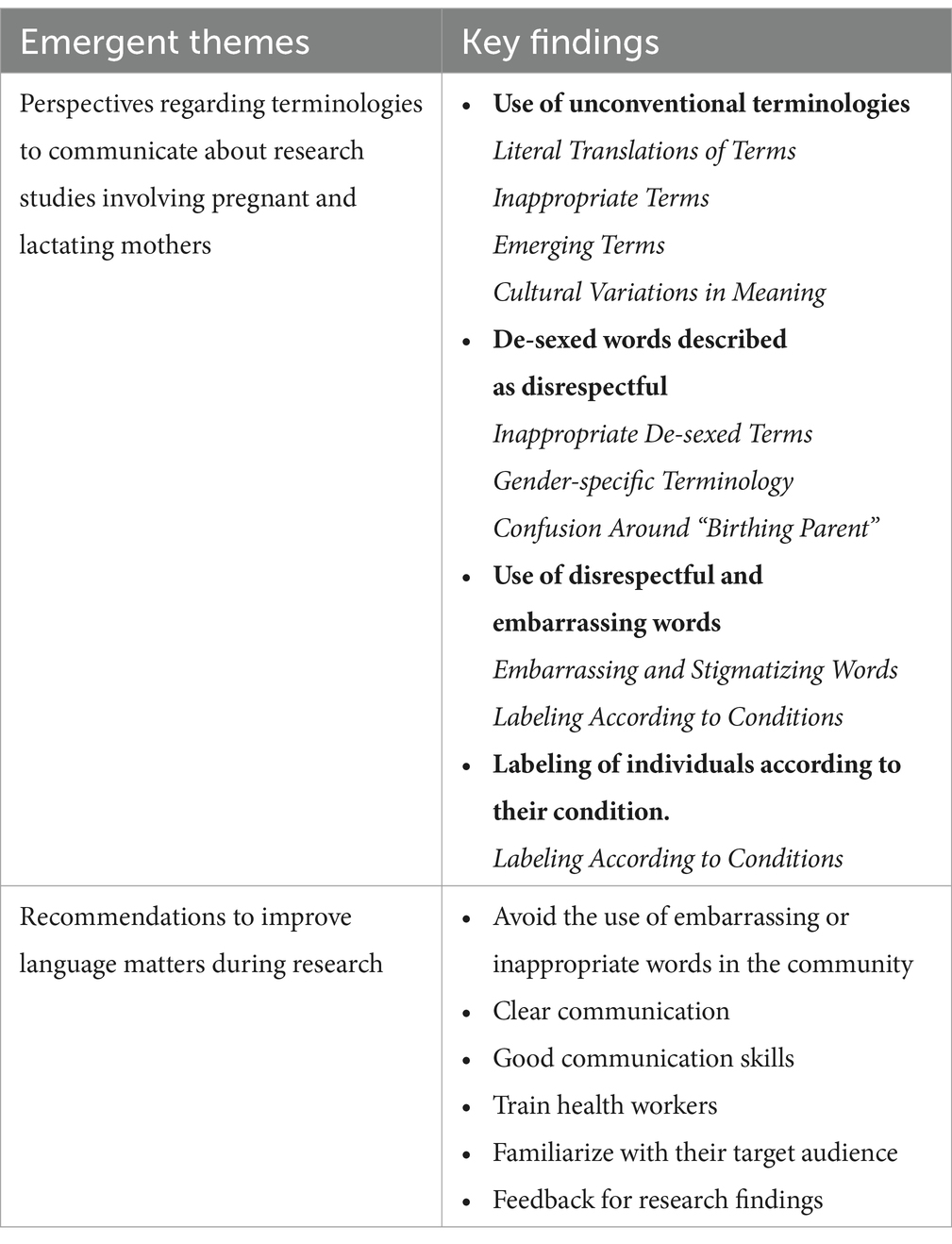

The study generated two themes from the focus group discussion as shown in Table 4.

Perspectives regarding terminologies to communicate about research studies involving pregnant and lactating mothers

Use of unconventional terminologies

Literal Translations of Terms: Participants sometimes used unconventional translations in their local languages, such as terms for parents who have lost children or fathers who biologically father children but do not live with them. For example, adolescence was translated as “the girl who has matured into an adolescent,” reflecting local perceptions of evolving changes.

“The girl who has matured into an adolescent’ because when a girl reaches that age of adolescence, she goes through certain biological stages that differ from the changes that the boy child experiences. She may go into her menstrual periods whereas the boy may develop beards. We fit them all in one bracket as long as you state that the girl has matured into an adolescent and the boy has matured into an adolescent.” (FGD_03_Men_IDI Mulago).

Inappropriate Terms: Certain words were considered inappropriate, such as “Malaya” (a term for prostitute), individuals with disabilities, mental illness, and the term “barren,” despite their widespread usage.

“Researchers use the word disabled people a lot and it is not polite, you would rather say, “Persons with disabilities’” (FGD_14_Young Adults_Busiisi subcounty_Hoima).

Emerging Terms: Participants mentioned a new preferred term for sex workers as pleasure consultants.

“Uh, I hear some people call them pleasure consultants nowadays. They even have advocates. That is what I hear. Some introduce themselves and say, “My name is… and I am a sex worker from Nateete.” They feel very comfortable about it.” (FGD_19_CAB Members_IDI Mulago).

Cultural Variations in Meaning: Some similar words differ in meaning across Bantu tribes. For example, the word ‘woman’ in the Luganda language is ‘omukyala’ yet in Runyankole and Runyoro they call her “omukazi” (woman) which might be offensive to the Buganda (Luganda-speaking) region.

De-sexed words described a disrespectful, inappropriate, or confusing

Inappropriate De-sexed Terms: Participants across most FGDs reported a discrepancy between words used by some international research communities and what was considered acceptable among local communities. They described the words as inappropriate for the local context. Participants noted that words that did not specify sex for instance, “pregnant person,” “a person with a uterus,” a “body with a vagina” or “chest feeding” caused mixed feelings of giggles, laughter, dismay, anger, or irritation as they sounded funny, too straight forward, but ultimately, in the communities represented, obscene and shameful.

Gender-specific Terminology: There was a strongly held belief that people were male or female. The majority of participants described a “person who menstruates” as a “woman who menstruates.” They insisted that it is girls or women who experience menstruation, and one emphasized that the term could mean that that person is continually menstruating. The term “person who menstruates” was deemed inappropriate due to its implication that only individuals who identify as women experience menstruation, thereby connecting the monthly menstrual cycle solely to female fertility.

“Person who menstruates” This language is disrespectful; you can think it's a person who is always menstruating.” This language is very disrespectful. It sounds like it is always happening without stopping” --FGD_04_Men_ Amuru District.

Confusion Around “Birthing Parent”: Participants summarized a “birthing parent” as a “mother” and it was commonly associated with being a new mother. However, some participants interpreted it as referring to females who had children or a Mukyala “omuzadde” [mother]. Others described a “birthing parent” as a “lady who gives birth” or a female parent whereas in other FGDs it was taken to refer to both male and female parents. It was clear that the term also introduced some confusion.

“When you say, birthing parents, it implies both male and female parents. Yet logically, only a woman can give birth…Birthing parents include both spouses. It shows that we both can give birth to a child. We think that a man cannot give birth because there is a misconception about the word birth to mean delivering a child. Birthing parents simply translates to the capacity of birth parents to give birth to a child. I think it combines both spouses” FGD_19_CAB Members_IDI Mulago.

Use of embarrassing words among healthcare workers

Embarrassing and Stigmatizing Words: Some participants said the researchers did not use the best language during informed consent. Some words included the following among others; “Malaya” [prostitute], young adult, the underprivileged, people with HIV, and “Omugumba” [barren]. Participants reported that some words used sounded very stigmatizing and disrespectful.

“For me, I like staying in the hospital, I sometimes go there to observe what is happening, like if the doctors would use English it’s better. Those people are using languages we do not understand. So, they should at least put the medical terms in lay language, right?” --FGD_09_Young Adults 18–24_Mvara subcounty_Arua.

Labeling of individuals according to their condition by healthcare workers caused stigma

Labeling According to Conditions: Some participants found labeling of individuals according to their condition by health workers, for example, “HIV patients” or “sickle cell patients” offensive.

“There are some words which are not pleasant to my ears. For example, this HIV AIDs sounds very disrespectful to me. When we were here on 1st December, they called ‘HIV AIDs patients’ and I did not feel good about it. So, I would like them to package it better without exposing that the person is HIV positive. You can try to cover it up and package it in a way that it does not expose the patient’s disease. There are some health workers whom we find at the health facility saying, “HIV patients come here! Cancer patients come here!” Yet, she could simply come to the patients and tell them quietly without having to shout. You can quietly talk to them as a doctor and tell them, “We are going to attend to you at this time as a group.” You do not have to shout in public, “HIV patient” --FGD_17_Young Adults Research Participants-Mulago.

Recommendations from participants to improve language matters during research

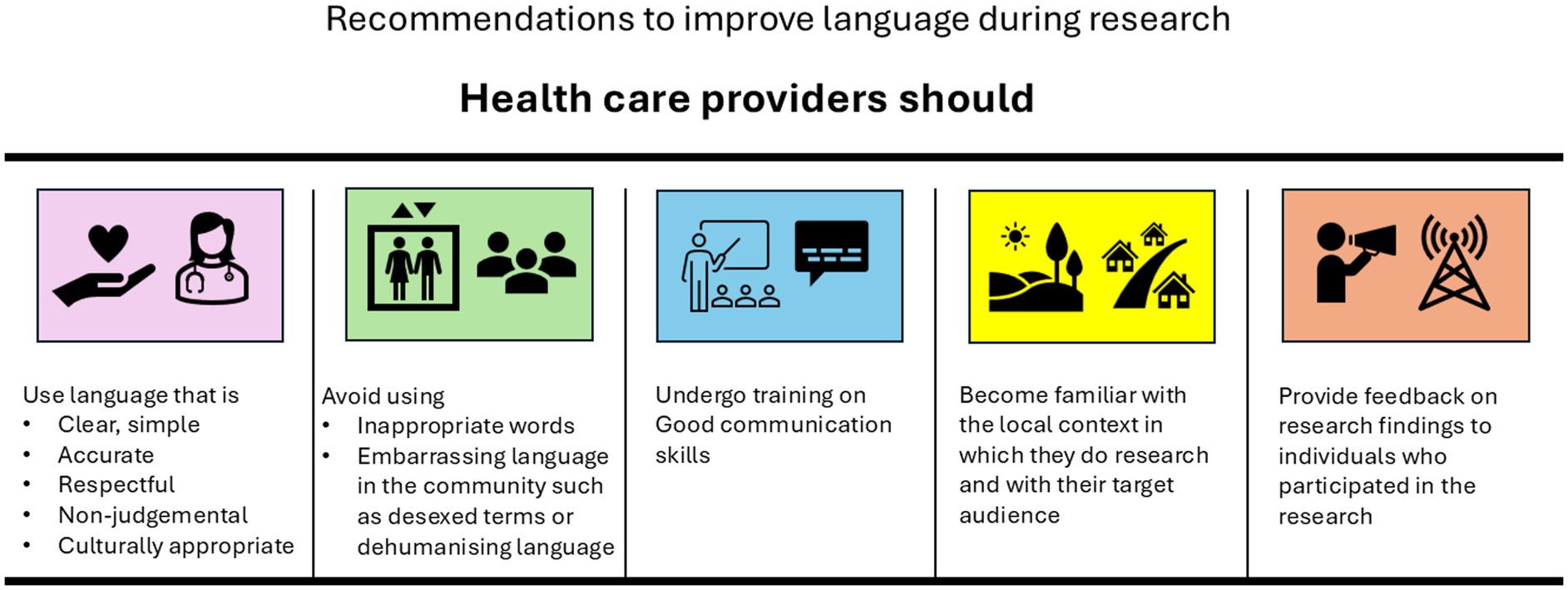

Participants provided recommendations for healthcare providers to enhance their language use during research, as outlined in Figure 2.

Avoid the use of embarrassing or inappropriate words in the community

Culturally Sensitive Terminology: To promote a respectful environment within the community, it is advisable to refrain from using embarrassing or inappropriate language. Utilizing culturally sensitive terminology that is neither shameful nor obscene can improve research outcomes. It is important to recognize that certain words may be deemed unacceptable in some communities while acceptable in others. Some participants noted that although words like “prostitute” and “barren” may be familiar to certain communities, they are still considered inappropriate.

“When the researchers come to the community, it would not sound appropriate to address a female adult as, “That woman.” Or say “Woman, we usually use words like; “Greetings Madam. How has been your day Madam?” (FGD_03_Men_IDI Mulago).

Clear communication about research words to participants

Respectful Word Choices: The majority of participants recommended presenting words in a highly courteous and non-judgmental manner. A participant suggested that researchers should opt for terminology such as “a woman unable to give birth” instead of “barren,” as it avoids causing distress to the woman, even though it conveys the same truth.

“The word ‘a woman unable to give birth’ would be better because in our societies ‘barren’ is even used as an insult. Now from my society, if you call a female ‘barren’ she cannot remain the same because it makes her feel very bad and even if it is the truth, she does not want to hear it.” (FGD_01_Young Adults 18–24_IDI Mulago).

Adoption of good communication skills among healthcare workers

Polite and Discreet Communication: Some participants expressed bitterness regarding words healthcare providers use when describing conditions or providing services in the community; persons with disabilities, HIV/AIDS.

“…some health workers whom we find at the health facility saying, “HIV patients come here! Cancer patients come here!” Yet, they could simply come to the patients and tell them quietly without having to shout. You can quietly talk to them as a doctor and tell them, “We are going to attend to you at this time as a group.” You do not have to shout in the public, “HIV patient” (FGD_17_Young Adults Research Participants-Mulago).

Train health workers on the use of appropriate health language

Empathy and Public Speaking: Participants expressed the need for health workers’ training in public speaking with an emphasis on empathy and the use of polite language to refer to vulnerable groups of people.

“…, most researchers come to the community, they are first trained am not talking about training from colleges or universities but they are first trained on what they are going to do….” FGD_16_Men_Research Participants, Mulago.

Researchers to familiarize themselves with their target audience and select appropriate terminology

Understanding the Local Context: During one focus group discussion, a participant recommended that researchers familiarize themselves with their target audience and select appropriate terminology for conducting research. It was suggested that researchers should study the language, dress code, and community environment before conducting their research.

“…before the researchers reach out to the community, they should first research about it…So, I recommend that you do prior inquiries about our communities before you reach out to us such that you come here and adapt to our language and social life” (FGD_19_CAB Members_IDI Mulago).

Feedback regarding study findings

Returning Results to Participants: Participants expressed concern that researchers infrequently return to disseminate research findings.

“You make us participate in research studies yet you do not return the findings from our blood or urine samples.” So, we request that whenever you involve us as participants, you return the results to us. We want to know the findings; the outcomes” (FGD_19_CAB Members_IDI Mulago).

Discussion

In this study of understanding of commonly used terminologies for pregnant and lactating mothers, two themes were identified and classified as follows: perceptions about specific terminologies used in research, and recommendations for improving language.

Participants reached a consensus on preferred words used in their respective languages. However, similar words differ in meaning across ‘Bantu’ tribes in Uganda. Some new terms were identified such as “pleasure consultants” referring to sex workers. In a few situations, study groups failed to reach a consensus on certain words such as female and male child. Some phrases like “adolescence” were difficult to directly translate but rather described as a process.

Language plays a crucial role in shaping self-perception and influencing how individuals are treated in healthcare settings. In this study, participants identified terms like “barren,” “disabled person,” and “HIV patient” as stigmatizing, which contributed to feelings of shame and social exclusion. Such language reinforces negative stereotypes, marginalizing individuals based on their health conditions. Adopting neutral or person-first language, such as “person living with HIV” or “person with a disability,” shifts the focus to the individual rather than the condition, promoting respect and dignity. Participants recommended using phrases like “a woman unable to give birth” instead of “barren” to avoid harmful connotations, aligning with global health guidelines that advocate for respectful and inclusive language. Burgess et al. emphasize the importance of language in shaping health outcomes and reducing stigma through appropriate communication strategies (Burgess et al., 2021), similar to Goffman’s work on the stigma that discusses how language and labeling can contribute to social exclusion and reinforce stereotypes (Goffman, 2009) and the WHO strategy for ending AIDS that recommends the use of person-first language to reduce stigma and empower individuals in healthcare settings (WHO, 2022). This is also comparable to prior studies that have documented the use of persistent exposure to language that disempowers persons and encourages stigmatizing language to persist in healthcare and community settings (Swaffer, 2014; Martinelli et al., 2020; Blankenship et al., 2010). On the contrary, the right words can encourage persons to access care and empower people (Lawson, 2005). There is thus, a need to discourage the use of stigmatizing language and encourage the use of inclusive language during research communication (Watson, 2019). The study underscores the importance of participatory methods in ensuring that research language is respectful, inclusive, and culturally appropriate. By involving community members, researchers can adapt their terminology to better align with local norms and values, fostering trust and improving engagement. This approach is especially crucial in diverse multicultural multilingual settings, where communication challenges are common. Engaging stakeholders such as CABs and peer mothers helps identify and avoid potentially stigmatizing terms, reflecting the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR) for greater cultural sensitivity and community benefit (Israel et al., 2019; Wallerstein and Duran, 2017).

While there is a growing trend towards adopting gender-inclusive terminology, particularly in international research communities, these terms are not always received positively or understood in the same way within local communities. Participants expressed a range of reactions to de-sexed language, including feelings of amusement, discomfort, and even anger. Terms such as “pregnant person,” “person with a uterus,” or “chestfeeding” were perceived as awkward, overly blunt, and ultimately disrespectful or shameful within the represented communities. This suggests a strong attachment to traditional gender norms and a belief that certain experiences, such as menstruation, are inherently linked to biological sex. As reflected in broader research, language that challenges entrenched gender norms can provoke resistance, especially in more conservative or traditional societies (Kitzinger, 2005). Similarly, the term “birthing parent” sparked confusion and differing interpretations among participants. While some saw it as inclusive of both male and female parents, others argued that it negated the biological reality that only women can give birth. This reflects a broader trend in which language intended to be inclusive in certain contexts can sometimes obscure understandings of biological realities in other settings as observed by Smith et al. (2010). It also highlights the importance of clear communication and contextual understanding when introducing new terminology, as well as the need to navigate cultural and societal norms sensitively (Guerra Garcia et al., 2020; Toledo-Sandoval, 2020). While de-sexed language may have its merits in promoting inclusivity and challenging traditional gender stereotypes, its adoption must be approached with caution and consideration for local perspectives and sensitivities. As observed in other communities, the shift towards de-sexed language may be seen as an imposition of foreign values rather than a progressive step toward inclusivity (Cameron, 2012).

Effective communication strategies and community engagement are crucial in ensuring that terminology aligns with cultural beliefs and values while promoting respectful and inclusive language use. As highlighted by Gribble it is crucial to openly discuss and carefully consider the significant implications of using de-sexed language when referring to processes and states inherently linked to biological sex (Gribble et al., 2022). This approach is essential to prevent confusion and ensure respectful communication within respective communities. Research on the use of respectful and inclusive language in health, especially in low-middle and income countries (LMICs), highlights the importance of culturally sensitive communication, using non-stigmatizing, respectful language improves patient trust and reduces stigma, particularly in communities affected by HIV (Dernaika, 2022). Wallerstein et al. emphasize that involving communities in creating culturally appropriate language tools through participatory research is key to enhancing engagement and inclusivity. These findings show that respectful communication is essential for building trust and improving health outcomes (Wallerstein and Duran, 2017).

Also, participants preferred simplified words for terminologies used in research. Prior studies also noted that preference for English in research increases with rising levels of education (Muzanyi et al., 2020; Karbwang et al., 2018). The use of appropriate words in respective communities was found to be crucial in this study; researchers should adopt culturally sensitive and acceptable words that are not shameful or obscene to the local community. Although some words used in research may seem inappropriate, studies could use phrases to describe such terms. Communities and patients are likely to have a helpful and beneficial relationship with healthcare providers if culturally sensitive language is used (Brooks et al., 2019).

In this study, recommendations to improve language matters during research were suggested; use of appropriate language during the consent process, communication about specific words through packaging of words in a very polite and non-judgmental manner, researchers should adopt good communication skills, training health workers on use of appropriate health language, involve communities in developing study tools in appropriate languages, and provide feedback regarding study findings. This aligns with findings on effective communication that highlighted that terms related to pregnancy and lactation can carry emotional and cultural weight, and inappropriate language can lead to misunderstanding or emotional distress (Gribble et al., 2023). Researchers have an ethical obligation to at best attempt to disseminate their research findings (Edwards, 2015). Several approaches could be used for the dissemination of research findings to communities including; community advisory board meetings, use of social media platforms, and local radio and television stations (Stewart et al., 2023; Mikesell et al., 2013). Also, conferences can be used although they are attended by leaders in the field (Douglas et al., 2019), who are more likely to be early adopters of research into practice. Researchers can explain their study results in detail and receive feedback that may be helpful for additional studies.

Healthcare workers should be trained in effective communication, focusing on non-judgmental, empathetic language, especially when discussing sensitive topics like pregnancy, lactation, disabilities, or chronic illnesses. Cultural competence and health literacy workshops can enhance patient interactions, particularly in diverse settings. Future research should focus on developing a deeper understanding of local languages and cultures to better navigate sensitive issues in health research. Researching how language affects access to care, particularly in LMICs, will help refine communication strategies to improve health outcomes and community participation.

Strengths

The study conducted focus group discussions in six languages of Uganda. We prioritized this diversity to inform local research communication efforts of commonly used terminologies for pregnant and lactating mothers. The use of a purposive sampling approach ensured that the study was able to capture individual views from different districts and local communities represented in the focus group discussions, and reached thematic saturation. To attain genuine equity of access to research, and equity of access to research findings it is essential that the correct language is used in referring to community members and participants. The study explored community members’ perspectives on the necessary terms, preferred terms, and phrases that are clear and inclusive within their communities. In addition to increasing diverse research participation, the findings from this study streamlined the development and translation of community-facing documents and also used the glossary for translations within the research department. Finally, the results from this work will inform and justify the correct terminology for use in scientific presentations and publications.

Limitations

Study participants were recruited from five regions of Uganda. Different findings may have been elicited from multiple tribal and linguistic groups in the country.

Conclusion

In summary, the use of appropriate language has been challenging for researchers in Uganda and requires improvement. The use of appropriate language enhances informed consent, research participation, and related facilitators, though language barriers need to be resolved. It is also imperative that these lessons and recommendations on language terminologies be integrated into informed consent forms and considered for long-term planning of research communication. The experiences and insights shared by our FGD participants provide invaluable guidance for simplifying terminologies to accommodate the diverse languages in a multicultural society for health research. Further studies are needed to establish language attitudes or differences between dialects or languages, background to different languages, description of dialect variations across different locations (rural versus urban) in Uganda, and how it affects research communication.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Infectious Diseases Institute research ethics committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RN: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AT: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JB: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JK: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft. SN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CW: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study was funded by a Participatory Research Grant from the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences at the University of Liverpool. CW is funded by Wellcome Clinical Research Career Development Fellowship 222075_Z_20_Z.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the MILK Study team members and study participants. In addition, special thanks go to members of the MILK Community Advisory Board and members of the IDI research office for their insightful feedback during the development of this protocol.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

August, T, Reinecke, K, and Smith, NA, editors. (2022). Generating scientific definitions with controllable complexity. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers).

Bartick, M., Stehel, E. K., Calhoun, S. L., Feldman-Winter, L., Zimmerman, D., Noble, L., et al. (2021). Academy of breastfeeding medicine position statement and guideline: infant feeding and lactation-related language and gender. Breastfeed. Med. 16, 587–590. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2021.29188.abm

Blankenship, K. M., Biradavolu, M. R., Jena, A., and George, A. (2010). Challenging the stigmatization of female sex workers through a community-led structural intervention: learning from a case study of a female sex worker intervention in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS Care 22, 1629–1636. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.516342

Brockman, T. A., Balls-Berry, J. E., West, I. W., Valdez-Soto, M., Albertie, M. L., Stephenson, N. A., et al. (2021). Researchers’ experiences working with community advisory boards: how community member feedback impacted the research. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 5:e117. doi: 10.1017/cts.2021.22

Brooks, L. A., Manias, E., and Bloomer, M. J. (2019). Culturally sensitive communication in healthcare: a concept analysis. Collegian 26, 383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2018.09.007

Burgess, A., Bauer, E., Gallagher, S., Karstens, B., Lavoie, L., Ahrens, K., et al. (2021). Experiences of stigma among individuals in recovery from opioid use disorder in a rural setting: a qualitative analysis. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 130:108488. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108488

Chu, J. N., Sarkar, U., Rivadeneira, N. A., Hiatt, R. A., and Khoong, E. C. (2022). Impact of language preference and health literacy on health information-seeking experiences among a low-income, multilingual cohort. Patient Educ. Couns. 105, 1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.08.028

Cook, T., Boote, J., Buckley, N., Vougioukalou, S., and Wright, M. (2017). Accessing participatory research impact and legacy: developing the evidence base for participatory approaches in health research. Eur. Radiol. 25, 473–488. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2017.1326964

Dernaika, M. (2022). Oklahoma City University. Reducing stigmatization related to sexual health screenings. [dissertation].

Douglas, L., Jackson, D., Woods, C., and Usher, K. (2019). Innovations in research dissemination: research participants sharing stories at a conference. Nurs. Res. 27, 8–12. doi: 10.7748/nr.2019.e1685

Edwards, D. J. (2015). Dissemination of research results: on the path to practice change. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 68, 465–469. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v68i6.1503

Goffman, E. (2009). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Gribble, K. D., Bewley, S., Bartick, M. C., Mathisen, R., Walker, S., Gamble, J., et al. (2022). Effective communication about pregnancy, birth, lactation, breastfeeding and newborn care: the importance of sexed language. Front. Glob. Womens Health 3:818856. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2022.818856

Gribble, K. D., Smith, J. P., Gammeltoft, T., Ulep, V., Van Esterik, P., Craig, L., et al. (2023). Breastfeeding and infant care as ‘sexed’ care work: reconsideration of the three Rs to enable women’s rights, economic empowerment, nutrition and health. Front. Public Health 11:1181229. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1181229

Guerra Garcia, E., Sandoval Forero, E., and Lopez De Haro, P. A. (2020). Socio-intercultural analysis of the displacement of the Yoremnokki in Jahuara II. Sinaloa: El Fuerte.

Healy, M., Richard, A., and Kidia, K. J. (2022). How to reduce stigma and bias in clinical communication: a narrative review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 37, 2533–2540. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07609-y

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Coombe, C. M., Parker, E. A., Reyes, A. G., Rowe, Z., et al. (2019). Community-based participatory research. Urban Health 272, 272–282. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190915858.003.0029

Karbwang, J., Koonrungsesomboon, N., Torres, C. E., Jimenez, E. B., Kaur, G., Mathur, R., et al. (2018). What information and the extent of information research participants need in informed consent forms: a multi-country survey. BMC Med. Ethics 19, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12910-018-0318-x

Kitzinger, C. (2005). Heteronormativity in action: reproducing the heterosexual nuclear family in after-hours medical calls. JSTOR 52, 477–498. doi: 10.1525/sp.2005.52.4.477

Lawson, H. (2005). Empowering people, facilitating community development, and contributing to sustainable development: The social work of sport, exercise, and physical education programs. Sport Educ. Soc. 10, 135–160. doi: 10.1080/1357332052000308800

Lincoln, Y. S., and Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Malaba, T. R., Nakatudde, I., Kintu, K., Colbers, A., Chen, T., Reynolds, H., et al. (2022). 72 weeks post-partum follow-up of dolutegravir versus efavirenz initiated in late pregnancy (DolPHIN-2): an open-label, randomised controlled study. Lancet HIV 9, e534–e543. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00173-4

Martinelli, T. F., Meerkerk, G. J., Nagelhout, G. E., Brouwers, E. P., van Weeghel, J., Rabbers, G., et al. (2020). Language and stigmatization of individuals with mental health problems or substance addiction in the Netherlands: an experimental vignette study. Health Soc. Care Commun. 28, 1504–1513. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12973

Mikesell, L., Bromley, E., and Khodyakov, D. (2013). Ethical community-engaged research: A literature review. Am. J. Public Health 103, e7–e14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301605

Muzanyi, G., Sekitoleko, I., Johnson, J. L., Lunkuse, J., Nalugwa, G., Nassali, J., et al. (2020). Level of education and preferred language of informed consent for clinical research in a multi-lingual community. Afr. Health Sci. 20, 955–959. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v20i2.51

Nakijoba, R., Kawuma, A. N., Ojara, F. W., Tabwenda, J. C., Kyeyune, J., Turyahabwe, C., et al. (2023). pharmacokinetics of drugs used to treat uncomplicated malaria in breastfeeding mother-infant pairs: an observational pharmacokinetic study. Wellcome Open Res. 8:12. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.18512.1

Nyumba, T., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., and Mukherjee, N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 20–32. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12860

WHO. (2022). Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030 : World Health Organization.

Seward, N., Hanlon, C., Hinrichs-Kraples, S., Lund, C., Murdoch, J., Salisbury, T. T., et al. (2021). A guide to systems-level, participatory, theory-informed implementation research in global health 6:e005365. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005365

Smith, C. A., Johnston-Robledo, I., McHugh, M. C., and Chrisler, J. (2010). Handbook of gender research in psychology. New York, NY: Springer New York, 361–377.

Stewart, E. C., Davis, J. S., Walters, T. S., Chen, Z., Miller, S. T., Duke, J. M., et al. (2023). Development of strategies for community engaged research dissemination by basic scientists: a case study. Transl. Res. 252, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2022.09.001

Stoll, M., Kerwer, M., Lieb, K., and Chasiotis, A. J. P. O. (2022). Plain language summaries: a systematic review of theory, guidelines and empirical research. PLoS One 17:e0268789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268789

Swaffer, K. (2014). Dementia: Stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. Dementia 13, 709–716. doi: 10.1177/1471301214548143

Toledo-Sandoval, F. (2020). Local culture and locally produced ELT textbooks: how do teachers bridge the gap? System 95:102362. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102362

Keywords: participatory research, preferred terminologies, pregnant and lactating mothers, focus group discussion, community advisory board

Citation: Nakijoba R, Twimukye A, Bayigga J, Kawuma AN, Asiimwe SP, Byenume F, Kyeyune J, Nabukenya S, Ojara FW and Waitt C (2025) Culturally appropriate terminologies in health research: a participatory study with pregnant and breastfeeding mothers in Uganda. Front. Commun. 9:1450569. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1450569

Edited by:

Rukhsana Ahmed, University at Albany, United StatesReviewed by:

Kayi Ntinda, University of Eswatini, EswatiniRavi Philip Rajkumar, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), India

Copyright © 2025 Nakijoba, Twimukye, Bayigga, Kawuma, Asiimwe, Byenume, Kyeyune, Nabukenya, Ojara and Waitt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Catriona Waitt, Y3dhaXR0QGxpdmVycG9vbC5hYy51aw==

Ritah Nakijoba

Ritah Nakijoba Adelline Twimukye

Adelline Twimukye Josephine Bayigga1

Josephine Bayigga1 Catriona Waitt

Catriona Waitt