- Department of Communication Studies, imec-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

To address environmental issues, it is important to strengthen individuals' environmental self-identities. This research explored how environmental non-profit organizations (NPOs) use and perceive communication interventions (social norms, perceived environmental responsibility, and social comparison feedback) that could make the environmental social - and self-identities of their community salient. This is achieved by combining a quantitative content analysis of social media posts (n = 448), with six in depth-interviews with communication professionals working in NPOs. We found that descriptive social norms (25.7%) are the most frequently used intervention by NPOs. However, these norms can reduce personal responsibility for environmental actions, and NPOs rarely combine them with personal responsibility messages or injunctive norms, which could tackle this issue. Secondly, we found that the NPO communication professionals are implicitly focusing on increasing the group identification with the organization by using advocates and personal communication with their members. Furthermore, the included NPOs mainly communicate with individuals who already hold environmental values. Consequently, the study identifies a current mismatch between this environmentally conscious audience and the interventions the NPOs are utilizing. Descriptive social norms, which are widely used by the NPOs, are more appropriate for the general public-an audience with weaker connections to the NPOs but one they aim to reach more in the future. In contrast, injunctive and dynamic social norms, both minimally employed by the NPOs, appear more suitable for their current environmental audience. Last, we found that NPOs emphasize their responsibility in addressing environmental issues (20,8%) but neglect to acknowledge governmental efforts (0,9%), which could enhance citizens' environmental self-identity and promote pro-environmental behaviors. This study provides insight into more effective NPO communication strategies, particularly through better audience segmentation and integrating different types of social norms to enhance pro-environmental identities and behaviors.

1 Introduction

Environmental issues, such as climate change, largely stem from unsustainable individual and collective human behaviors. Promoting more pro-environmental actions to shift these behaviors is crucial in mitigating environmental challenges (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023). Some environmentally sustainable habits have taken root in the past 4 years, as a direct consequence of the COVID-19 sanitary crisis (O'Connor and Assaker, 2021). Examples are reduced air- and car travel (Ho et al., 2023). It will however be important to maintain the promotion of these pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs), hence, optimizing efforts to develop and sustain effective behavior change interventions will be essential.

Environmental self-identity, which is defined as “the extent to which you see yourself as someone that is pro-environmental” (van der Werff et al., 2021), is an important predictor of multiple pro-environmental behaviors (Whitmarsh and O'Neill, 2010; Gatersleben et al., 2014; Udall et al., 2021; Lavuri et al., 2023). Therefore, making environmental self-identities, which are quite robust (Gatersleben and Van Der Werff, 2019) more salient presents a valuable strategy for those aiming to promote pro-environmental behaviors.

The Social Identity Approach (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987), an important theory on the principles shaping self-identity, states that people formulate their self-concepts (including their environmental self-identity) based on their social groups and contexts. Therefore, environmental self-identity and social identity are very closely related. Previous research trying to prime environmental self-identities focused on reminding people of their past pro-environmental behaviors (e.g. Van der Werff et al., 2014). However, more recently, Wang et al. (2022) have shown that a strengthened environmental group identity was also related to an increased environmental self-identity. Prior studies also emphasized the need for more focus on a group-level pathway (Brick and Lai, 2018; Jans et al., 2018; Bouman and Steg, 2019; Bouman et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021) and the usage of identity interventions (Brick and Lai, 2018). Environmental groups like environmental non-profit organizations (NPOs) have environmental values and concerns at their core (Carmin and Bast, 2009). NPOs therefore play an important role in communicating about environmental issues and trying to create more pro-environmental behaviors (Buchs et al., 2012; van Wissen and Wonneberger, 2017; Mermet, 2018; Schäfer, 2022). Drawing on the intergroup processes of the SIA (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987), it can be argued that when individuals identify with the NPO, they align themselves with this environmental group and its social identity. As this environmental social identity becomes more salient, perceived differences between outgroup members are magnified, while the similarities with the ingroup members are emphasized. This leads ingroup members to base their environmental self-identity, attitudes, and behaviors, upon the ingroups' social identity and norms (Fielding and Hornsey, 2016). As environmental NPOs are main actors communicating about environmental issues online, they have the potential to shape and strengthen these environmental social- and self-identities through their communication strategies. Based on the SIA (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987), certain interventions are highlighted that could enable the activation of the environmental social- and self-identities, namely, social norms, social comparison feedback, and perceived environmental responsibility. This study wants to capture both the frequency of communication interventions and the decision-making processes behind them.

This leads to the following research questions for this study:

RQ1: To what extent do environmental non-profit organizations use online communication interventions derived from the Social Identity Approach (social norms, social comparison feedback, and perceived responsibility) that could enable the saliency of environmental self- and social identities?

RQ2: How do environmental non-profit organizations' communication professionals view the online communication interventions derived from the Social Identity Approach (social norms, social comparison feedback, and perceived responsibility) that could enable the saliency of environmental self- and social identities and pro-environmental behavior within existing practices?

In the next section, a more thorough review of the existing literature will follow, with a discussion on environmental self-identity, the theoretical background (the SIA), environmental non-profit organizations and their role in creating salient environmental self- and social identities, and the related interventions; social norms, perceived environmental responsibility, and social comparison feedback.

2 Literature review

2.1 Environmental self-identity

Environmental psychological research, which is the field specialized in maintaining and changing pro-environmental behaviors, highlights that effective behavior change interventions rely on targeting the right environmental behavior change determinants, defined as “psychological variables (for example, perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, norms, and emotions) that motivate people to engage in a particular environmental behavior” (van Valkengoed et al., 2022). This research field has primarily focused on targeting specific behavior determinants like attitudes and intentions of one specific behavior (Steg, 2018). However, to create long-lasting pro-environmental behavioral changes, the field is calling for more interventions that target general determinants that encourage people to consistently engage in many different climate mitigation actions, namely, environmental self-identity, feelings of responsibility to act on climate change, and biospheric values (Steg, 2018). These three determinants will be less predictive for a specific behavior but will potentially lead to more long-term and global behavior change in different pro-environmental behaviors and contexts (Steg, 2018).

When looking into these three general determinants of pro-environmental behavior, it becomes apparent that environmental self-identity is an important mediator between both values and feelings of responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors. Namely, environmental self-identity was found to be a full mediator between biospheric values and environmental preferences, intentions, and behavior (van der Werff et al., 2013; Van der Werff et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2021) and a mediator between perceived governmental and corporate environmental responsibility and sustainable actions (van der Werff et al., 2021). Also, it was shown that environmental self-identity is a significant behavioral determinant over and above the variables of one of the most used behavior change theories, namely the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) for carbon offsetting behavior (Whitmarsh and O'Neill, 2010). This theory stipulates that the main predictor of behavior change is the intention for that behavior. In turn, the intention is predicted by three variables, namely attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991). Furthermore, research has demonstrated the effectiveness of an increased environmental self-identity in changing various pro-environmental behaviors, which include; sustainable consumption, waste reduction, water savings, domestic energy conservation, recycling, buying fair trade products and abstaining from touristic flights (Whitmarsh and O'Neill, 2010; Gatersleben et al., 2014; Udall et al., 2021; Lavuri et al., 2023).

Because of the significance environmental self-identities can have on sustainable outcomes (Wang et al., 2022), recent research on pro-environmental behavior change has increasingly focused on the role of environmental identities (e.g. Udall et al., 2021). However, as environmental self-identity cannot be separated from environmental social and group identities (Mackay et al., 2021), the remainder of the literature will delve deeper into one theory explaining the mechanisms behind environmental self-identity, namely the Social Identity Approach (SIA) (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987; Mackay et al., 2021). It is imperative to look at this theory because people not only behave in line with their self-concepts but also derive a part of their identity from their social context, which leads to their salient social identity. The Social Identity Approach highlights the relationship between both self- and social identity and the influence on individual values and behaviors (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). Interventions derived from the SIA will then be used for the analysis of communication messages by environmental non-profit organizations (NPOs), as NPOs are important actors in creating pro-environmental behaviors (Buchs et al., 2012; Mermet, 2018).

2.2 The Social Identity Approach

The Social Identity Approach (SIA), consisting of both the Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) and the Self-Categorization Theory (Turner et al., 1987), can further explain the relationship between environmental self-identity and pro-environmental behaviors. These two theories aim to explain how our attitudes, emotions, and behaviors are influenced by the various groups we belong to. Moreover, as it focuses on the fact that people derive part of their self-concept from the social groups they belong to (Hogg and Reid, 2006), one of its central themes relates to personal (or self-) identity and its relationship with social identity. The Social Identity Theory focuses on intergroup relations while Self-Categorization Theory explores intragroup processes. Because the two theories share important assumptions, they are jointly called the social identity approach. The SIA (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987) puts forward that our self-concept comprises both personal and social identities. Personal identity refers to individual and unique aspects of the self, like environmental self-identity (Udall et al., 2021) while social identities are derived from our group memberships. When an individual identifies with a particular social group, the process of categorization accentuates similarities with other ingroup members and differences with outgroup members. As a result, individuals' attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors tend to align with the norms of their salient social group and distance themselves from relevant outgroup norms (Jans and Fielding, 2015). This perspective is supported by findings that indicate that social norms and group memberships significantly influence individuals' environmental attitudes and behaviors (van Zomeren et al., 2008; Fielding and Hornsey, 2016; Mackay et al., 2021).

2.3 Environmental non-profit organizations as environmental social identities

Building on the SIA and previous research (Van der Werff et al., 2014; Fanghella et al., 2019), one possible approach for practitioners aiming to motivate pro-environmental behaviors is to make people's environmental self-identity more salient. Previous research has focused on priming environmental self-identities by focusing on the individual, for example by providing feedback on their past performances (e.g. Fanghella et al., 2019; Van der Werff et al., 2014). However, more recent research has called for more focus on the group-level pathways (Bouman and Steg, 2019, 2022; Brick and Lai, 2018; Jans et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021). According to the SIA, individuals are social animals and will integrate the social identity of the groups they identify with as a part of their self-concept (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). However, until now, research on priming environmental self-identities has primarily focused on personal pathways (e.g. Van der Werff et al., 2014).

Nevertheless, Wang et al. (2022) researched the group-level pathway and showed that environmental group identity can be strengthened and that consequently environmental self-identity was increased. Environmental self-identities still have a stronger connection to PEBs than group identities (Udall et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). Still, this is an indication that group factors like environmental group identity and group values can have an impact on environmental self-identities (Wang et al., 2022). Furthermore, it is also in line with the reasoning of the SIA that people derive their self-concepts based on their social context (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). This makes it clear that making environmental group identities salient, can also increase people's environmental self-identities if they identify with these groups.

Udall et al. (2021) showed that the associations between identity and PEB are particularly strong when the identity and PEB are matched (for example identifying with a salient ecological group will lead to ecological behavior). Therefore, environmental groups, like environmental non-profit organizations (NPOs) are actors with the possibility to make the environmental social identity of their communities more salient. This is because they have environmental issues at their core (Carmin and Bast, 2009). As the SIA states, identities are context-dependent, so when the context leads people to a salient environmental group identity, this could lead to a more pronounced environmental self-identity (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). This, in turn, could lead to more pro-environmental behaviors (Udall et al., 2020, 2021). This research will therefore focus on the communication by environmental non-profit organizations (NPOs) and is also in line with the recommendations of recent research stating the promotion of environmental group identities to be an opportune avenue toward the promotion of pro-environmental behaviors (Bouman and Steg, 2019, 2022; Brick and Lai, 2018; Jans et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021).

This study will specifically focus on the use of social media by NPOs. First, social media has become one of the primary sources of information today (O'Keeffe and Clarke-Pearson, 2011). Second, social media websites today create an environment where people with similar identities, like people who care about the environment, reinforce each other's views, which results in the shaping of environmental identities (Domalewska, 2021). This way, environmental NPOs have a significant opportunity to shape and strengthen these environmental self-identities through their communication strategies.

2.4 Interventions based on the Social Identity Approach

Given the possible impact of environmental NPOs' communication on creating salient environmental social and self-identities in their community, it is imperative to discover which interventions would be useful for making the environmental social identity salient. Looking at existing literature (e.g. Jans et al., 2018; Hogg and Reid, 2006; van der Werff et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022), certain components of the Social Identity Approach can be considered by NPOs to focus on in their communication, namely the reinforcement of group identification, social norms, perceived environmental responsibility, and social comparison feedback. The remainder of the literature section will delve deeper into these factors and highlight the most important research on these principles.

2.4.1 Social norms and ingroup identification

First, ingroup identification is the prerequisite for people to translate environmental values and norms into their social identity and environmental self-identity (Fritsche et al., 2018; Nigbur et al., 2010; Smith and Louis, 2008; Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). Additionally, according to the SIA, communication from ingroup members is viewed as more credible and trustworthy, thereby having a stronger influence on behavior (Hornsey and Hogg, 2000; Hogg and Reid, 2006; Fielding and Hornsey, 2016). Therefore, the NPOs must reinforce group membership and that way group identification.

As there is already a vast body of literature on the relationship between social norms and pro-environmental behaviors (Farrow et al., 2017), this section will provide an overview of what has been written on social norms and social and self-identities. The SIA clearly states the importance of ingroup norms (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). The provision of social norms information is an intervention that has been wildly studied, included in behavior change theories (e.g. Norm focus theory; Cialdini et al., 1990) and proven in its relationship to PEBs (Farrow et al., 2017).

Overall, there are three different kinds of social norms, namely, the injunctive, descriptive, and dynamic social norms. First, the injunctive social norms tell people which behaviors are approved or disapproved of. Furthermore, descriptive social norms state which behaviors other people are doing (e.g. Cialdini et al., 1990). One effective way to communicate the descriptive social norm is by showcasing community members leading pro-environmental initiatives, as bottom-up approaches foster pro-environmental social identities (Jans, 2021). Last, dynamic social norms are newer in the field of pro-environmental behavior change but have been shown to also have an impact (Sparkman and Walton, 2017, 2019; Carfora et al., 2022). These are used when a behavior is not yet the social norm but is becoming more prevalent and changing (Sparkman and Walton, 2017, 2019). While the overall effectiveness of social norms is established, research has highlighted some inconsistencies, showing that their effectiveness depends on personal and contextual factors (Farrow et al., 2017). The SIA can help uncover these inconsistencies. First, the extent to which social norms influence people's environmental self-views relies on how strongly the individual identifies with that particular group (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Masson et al., 2016; Udall et al., 2021; Chung and Lapinski, 2024). Secondly, the relationship between social norms and behaviors is dependent on how strong the behavioral relevancy of that group is, with environmental behaviors being more in line with environmental groups (Fielding and Hornsey, 2016; Terry et al., 1999). Moreover, Bertoldo and Castro (2016) stress the different effectiveness of injunctive and descriptive norms, based on the extent to which a specific person identifies with the group. Injunctive social norms predict environmental self-identity more when people identify strongly with the group, while descriptive social norms predict environmental identities more directly (Bertoldo and Castro, 2016). This means that when people identify strongly with a group, they find it more important to what extent the members of the group approve or disapprove of certain behaviors. In comparison, people that do not identify that strongly with the group, find it more important to know what other people do (Bertoldo and Castro, 2016). Furthermore, Chung and Lapinski (2024) also found that when people perceive the group as the in-group (strong identification and similarity), dynamic norms messages were more effective than low descriptive norms messages. However, when they perceived the group as the outgroup (low identification and similarity), the opposite was found, and the low descriptive social norms were more effective than dynamic social norms.

Research has already stressed that social norms should be included more in research looking at the relationship between identities and pro-environmental behavior changes as there is a clear relationship (Udall et al., 2021). The purpose of this research is not to look into empirical relationships between environmental self- and social identities, but to study to what extent an environmental group like an NPO is communicating the different social norms and their perspectives on them.

2.4.2 Perceived environmental responsibility

van der Werff et al. (2021) based their argument on the SIA and found evidence that when individuals associate themselves with an organization or government, these actors can influence their environmental self-identities and pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) by an increased perceived environmental responsibility. Moreover, this shows that when NPOs highlight the actions of organizations and governments tackling environmental issues, this can enhance individuals' environmental self-identities (van der Werff et al., 2021).

Whereas perceived environmental responsibility (PER) in this context refers to the extent to which actors take up their responsibilities on environmental issues, PER has also been used to describe the ascription of responsibility. This covers the extent to which people ascribe the responsibility to do something about environmental issues toward themselves or external parties (Schwartz, 1977). Moreover, the ascription of responsibility is central in many pro-environmental behavior change theories (e.g. NAM, Schwartz, 1977) and has been shown to have an impact on PEBs (e.g. Soopramanien et al., 2023). Nonetheless, as climate change and environmental issues are a collective problem, many actors can be seen as responsible, namely, citizens, organizations, non-profit organizations, and governments (Hormio, 2023).

The communication of responsibility and social norms has also been linked to each other in for example the model of norm-regulated responsibility (Ai and Rosenthal, 2024). This model states that the communication of descriptive social norms should also be used cautiously, as excessive use of this intervention can lead to people decreasing their ascription of responsibility. However, using injunctive norms can reduce this negative effect of descriptive norms on the ascription of responsibility.

2.4.3 Social comparison feedback

Previous research on priming environmental self-identity at a personal level has shown that providing feedback on individuals' past pro-environmental behaviors can make their environmental self-identity more salient (Van der Werff et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2022).

However, as this research focuses on the group-level pathway, it is interesting to look at other feedback mechanisms. As the SIA focuses on “we” vs. “them” thinking, it has also been highlighted that the social comparison with less environmental groups can prime environmental identities (Rabinovich et al., 2012). Also, Wang et al. (2021) have stressed the importance of using interventions that target the perceived group values and in a later study explicitly mention the relevance of social comparison feedback (Wang et al., 2022).

Until now, research has primarily focused on priming environmental self-identity through a personal pathway (Wang et al., 2022). This research is novel in highlighting components of the social identity approach as a means for NPOs to tap into environmental social – and self-identities. It is crucial to explore how NPO communication professionals perceive and implement these interventions. Their views on the effectiveness of social norms, social comparison feedback, and perceived responsibilities can offer valuable insights into current practices and areas for improvement. Additionally, a mixed-method approach—combining a quantitative content analysis of selected NPOs' social media communication with qualitative in-depth interviews with the communication professionals—will provide a comprehensive understanding of how these interventions are used and their impact on nurturing environmental self-identity among followers. The following sections detail the mixed methods approach used to address the research questions. The results section delves into findings from in-depth interviews with communication professionals at environmental NPOs, followed by a quantitative content analysis. The study concludes with a discussion, conclusion, and limitations section with specific recommendations for practitioners and future research.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Mixed methods approach

This study employed a mixed methods approach to examine how environmental NPOs incorporate interventions related to enhancing environmental social and self-identities in their communication, and to understand the perspectives of their communication professionals regarding the utilization of these communication interventions. Both a quantitative content analysis of environmental NPOs' social media posts on Instagram and in-depth interviews with communication professionals of the NPOs were carried out. A concurrent embedded mixed methods strategy was used, meaning that the content analysis and the interviews were conducted in parallel, and the results of both methods were compared in the data analysis phase. Combining two complementary research strategies creates a broader picture and can balance out the weaknesses of both strategies (Creswell, 2013). The combination of both a quantitative analysis of the online communication channels with qualitative interviews with the communication professionals allows for an in-depth understanding of the current social media practices as well as the strategy and motivations behind these.

3.2 Sampling

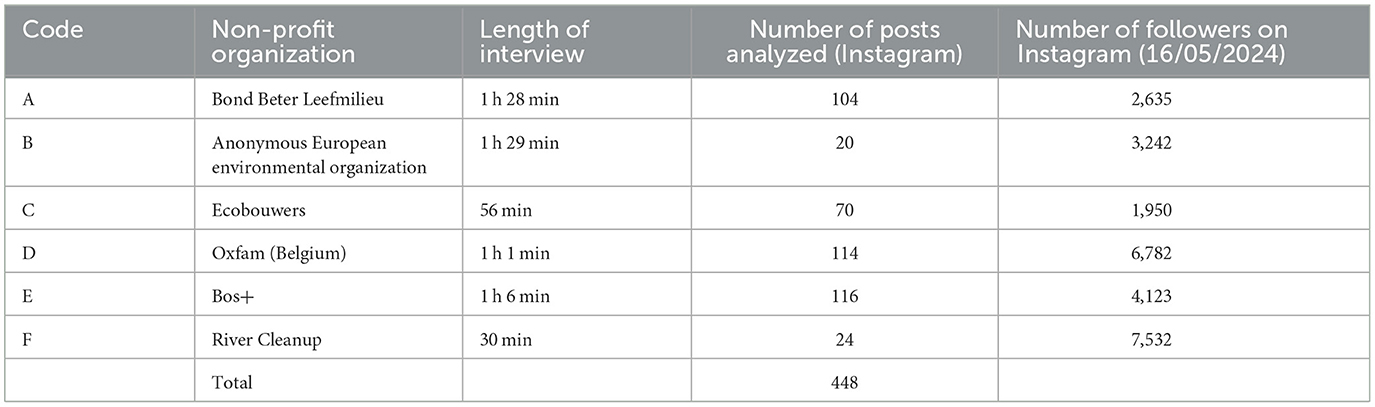

A purposeful sampling strategy (Sandelowski, 1995) was applied to select the relevant environmental NPOs. The selected NPOs had to match the following inclusion criteria; being an environmental non-profit organization (accredited NGOs included), focusing on environmental issues (e.g. waste prevention, energy conservation, bio-diversity conservation), being based in Belgium or being focused on European countries, being focused on reaching citizens, and being active on Instagram. Consequently, sixteen NPOs fitting all criteria were contacted. Six communication professionals of NPOs answered positively and were included in the research. A list of the participating organizations can be found in Table 1, due to privacy reasons, not all the names of the organizations are disclosed.

To understand what interventions these six NPOs use throughout a year, the social media posts were selected by scraping all the Instagram posts of that organization from the last year (4/06/2022–4/06/2023). This included photos and videos, but excluded stories, as it was not possible to collect these of the past year. Instagram was selected because this is one of the most important social media network sites (Digital 2023: Global Overview Report, 2023). A systematic review of studies on social media and climate change revealed a very limited focus on this platform (one study of the 45 included studies) and urged researchers to examine these “newer” platforms more (Sultana et al., 2024). Also, previous research has stressed this channel to be increasingly important for NPOs (Claro Montes et al., 2024). The selection of all posts in the selected timeframe led to a total sample of 448 posts that were included in the analysis. The organization with the fewest posts (B), had 20 posts on Instagram, and the organization with the most posts (E) accounted for 116 posts.

3.3 Content analysis

A quantitative textual content analysis was conducted on the selected social media posts of those organizations that were included in the research sample (n = 5, see Table 1). A quantitative content analysis is used to analyse documents or texts to quantify content in terms of predetermined categories, always in a systematic manner (Bryman, 2012). To guide this process, a codebook was constructed to be able to code the posts systematically. The codebook was constructed based on the definitions from literature per intervention (Supplementary Appendix 1); social comparison feedback provision (Abrahamse and Matthies, 2019; van Valkengoed et al., 2022), social norms (van Valkengoed et al., 2022), and endorsing governmental and corporate environmental responsibility (van der Werff et al., 2021). To test the validity of the codebook, a first close reading took place of a small subsample of posts (n = 50). In this close reading, multiple posts were found referring to whose responsibility it is to minimize environmental issues. Therefore, three layers of responsibility (Hormio, 2023) were included after the first round of intercoder reliability testing. Namely, whether it is the responsibility of citizens, corporations, or governments, to tackle environmental issues.

The two authors went through two rounds of intercoder reliability of a test sample (n = 50) and calculated Cohen's Kappa for every principle. After two coder rounds, the codebook was finalized and resulted in all variables in the final codebook scoring substantial to almost perfect (Gisev et al., 2013). The individual scores per variable can be found in Supplementary Appendix 2. Next, all 448 posts were coded, using the final codebook. After all the posts were coded, they were analyzed using SPSS to calculate frequencies and correlations (by using simple Chi-square tests).

3.4 Qualitative interviews

For the in-depth interviews, a semi-structured topic list was constructed. A semi-structured topic list allows for a more open conversation between the researcher and the participant, allowing additional topics and follow-up questions to emerge during the interview (Bryman, 2012; Mortelmans, 2007). The topic list covered questions regarding the main target groups and channels of the organization, their online and social media strategies and messaging, and lastly, their perspectives on the different interventions from the literature. All interviews were conducted and recorded via Microsoft Teams and lasted ~1 h. Afterwards, they were fully transcribed for analysis, for which the software tool MAXQDA was used. A Grounded Theory approach (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) was used to analyse the interviews. Grounded theory is an inductive approach, based on a thematic analysis of the qualitative research data. Concretely, three levels of coding were applied: open coding, axial coding and selective coding. The coding was applied inductively, starting from the raw data (interview transcripts) and applying a constant comparative method, meaning that for each new fragment, the researcher checked whether it fitted under an existing code, or whether a new code needed to be developed. The concepts from literature, such as selected interventions; were used as sensitizing concepts (Bowen, 2006), meaning that they provided the researchers guidance, without limiting the analysis to only these concepts.

4 Results

This section will delve deeper into the main findings of the study, focusing both on the findings of the qualitative in-depth interviews and the quantitative content analysis. First, the professionalism of the field and the reached target audiences will be discussed, followed by an elaboration on the studied interventions. Per intervention, both the frequency (based on the content analysis), as well as the communication professionals' perspectives (based on the interviews) will be detailed. Last, based on the content analysis an elaboration will follow on which interventions are significantly used together on Instagram by NPOs.

4.1 Professionalism of the field

The extent to which the communication efforts are streamlined by a broader communication strategy depends on the organization. Some organizations already have very elaborate strategies in place [for example D (Oxfam Belgium) and B (the European NPO)], whereas other organizations are still creating their communication strategies. Furthermore, in their day-to-day tasks, almost none of the communication professionals indicated they were actively thinking about using the different interventions that were identified in the literature and discussed during the interviews. Overall, the communication professionals also lack some knowledge about the existence of these interventions in general and some of them use more of a gut feeling when it comes to their communication strategy;

“It's a bit too much gut feeling at times. But I do keep it somewhere in the back of my mind, for example, okay I've now put something on policy with that tone of voice, then now I'll go for something else. I'm not going to do three policy posts in a row, for example, or not three of the same kind. We do try to do a bit of everything and something light-hearted there and something funny to a bit of a wider audience and then something a bit more specific and then one time a bit worse news. In that sense, I do try that a bit.” [E (Bos+)]

Nevertheless, all interviewed communication professionals have some strategies in place and are also eager to learn more about the interventions discussed in the literature, which can further improve the usage of evidence-based communication strategies.

4.2 Target groups: the environmentalists vs. “regular” people

Talking about the different target groups of the NPOs, first, it became apparent that they have multiple stakeholders on which they focus with different social media channels. They focus on a variety of groups including policy makers, media outlets, other third sector organizations (including grassroots organizations), corporations, and citizens (including members and donors). When digging deeper into the reaching of different citizens, it became quite clear that most of the interviewed NPOs predominantly reach people who are already environmentally oriented. For example, when asking the communication professional of NPO A (BBL) whether they are having difficulties reaching any target audience; “Yes, yes many audiences actually, right? I think that we are still in a bit of a niche audience though.” Overall, the communication professionals are trying to create events and campaigns to reach a wider public, and that way also reach people that are not that environmentally conscious yet. What was also clear is that intersectionality is high on the agenda for many of the NPOs; “We've been trying to improve our intersectionality approach as well. Of course, there are people within that spectrum that follow us, but we think we think we could be more representative” (B, Anonymous European environmental organization).

4.3 Frequency per intervention

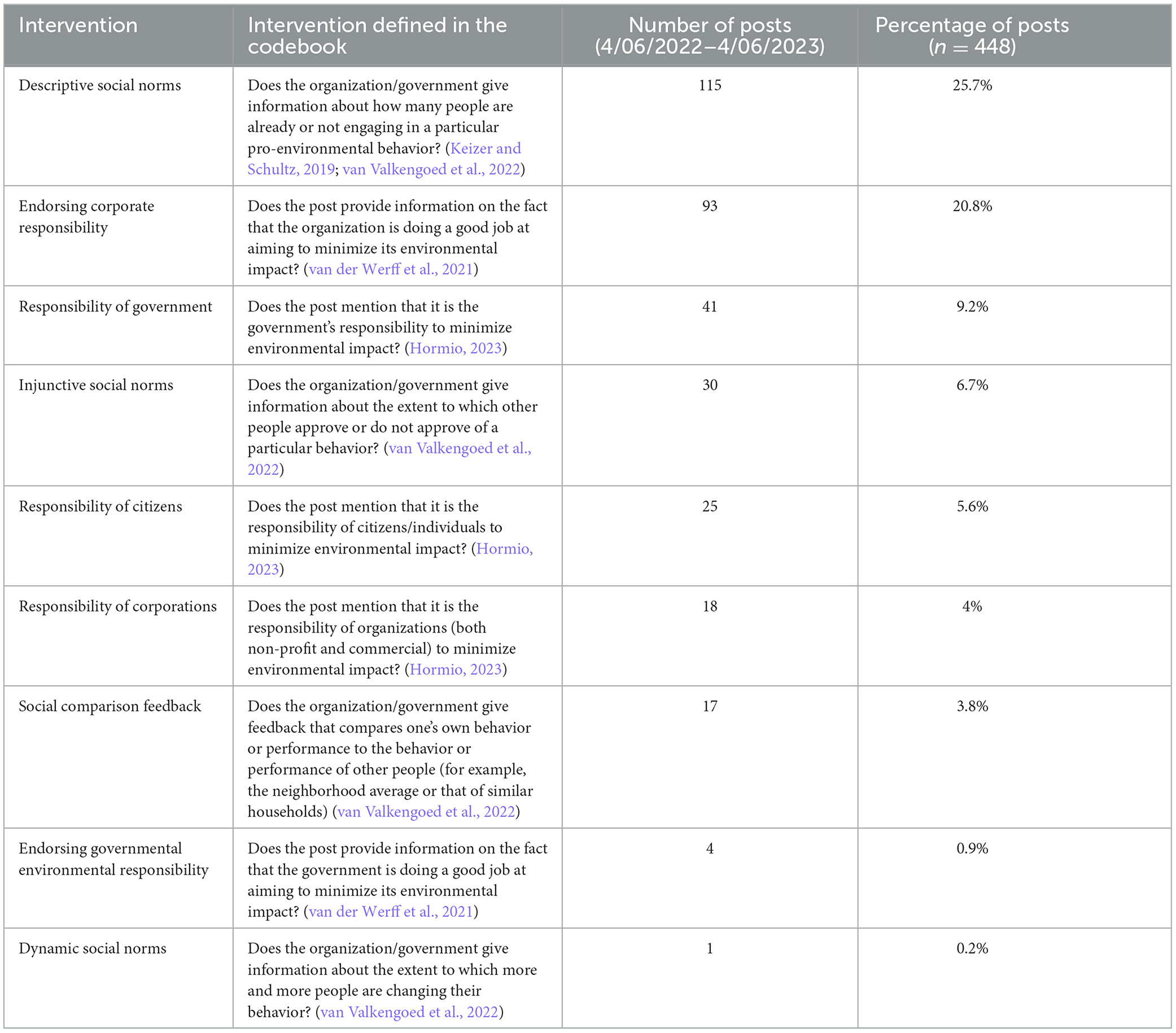

First, a frequency analysis per intervention shows big differences in the presence of the interventions from the literature (Table 2). First, the interventions that are used the most consist of descriptive social norms (n = 115, 25.7%) and endorsing corporate responsibility (n = 93, 20.8%). Then, interventions that are used to a smaller extent, namely, government responsibility (n = 41, 9.2%), injunctive social norms (n = 30, 6.7%), citizen responsibility (n = 25, 5.6%), corporate responsibility (n = 18, 4%), and social comparison feedback (n = 17, 3.8%). Finally, interventions that are only used in a small number of posts; endorsing governmental environmental responsibility (n = 4, 0.9 %) and dynamic social norms (n = 1, 0.2%). Different posts also combine more than one intervention. In the following sections, we will discuss the identified interventions in more detail. In the discussion, we will also elaborate on the meaning of these frequencies.

4.4 Usage of descriptive social norms and community building

The use of descriptive social norms is the most-used intervention by the NPOs on Instagram (n = 115, 25.7%; Table 2). Furthermore, this intervention is mostly used in isolation, as there is no significant correlation with any of the other interventions in the study. The provision of descriptive social norms is also very top-of-mind in the interviews with the communication professional, as they can immediately recall multiple examples of instances in which they have used this intervention in the past. For example, the communication professional of B, a European organization: “Because, for example, all the implementation part of our work and all the membership promotion is about showing what people are doing already to change norms and try to bring that up so that we you know, scale it up at European level.” The examples that the practitioners give are related to how many people attended an event, but also the usage of influencers which is something that more and more organizations are thinking about. Some of the organizations only have plans to do this more in the future, whereas others like D, Oxfam Belgium already use influencers to a great extent:

“Umm, we also collaborate with some influencers like. We have a big campaign in September called a second-hand September. And so, during that month in 2022, we contacted, not a lot, but a few influencers and asked them to reshare as opposed to talk about our campaign. So yeah, we try to, have that kind of relationship with some of them so they can share and share again in the future all content.”

Other communication professionals go one step further from using descriptive norms, as they think it is important to share what other people are doing, but to also use their own community to let them talk about the events and organization:

“We are increasingly working on that. First, of course, that was the Ecobouwers' open door. That's a huge audience. 130 people are opening their homes who advertise renovating themselves. Who invite their friends and family and who let that be known, who hang a poster on the door, ... so those are kind of our advocates. But that wasn't super visible actually outside their own circles, so that was then a bit of word-of-mouth and a bit of Facebook, but not super hard, but now with Instagram, we've had that since August. The open days take place in November, and we do see that being picked up tremendously there. So, people who share photos of their own homes who are also going to encourage others to maybe participate in the open houses, they really like the Ecobouwers-story and are definitely going to encourage others to also build sustainably and possibly open up their homes as well.” (C, Ecobouwers)

This shows the importance to the communication manager to create a community of people as advocates of both the organization but also of the behavior they are promoting, in this instance, building sustainably. To support these advocates, the communication managers also highlight the importance of personal communication with these people, for example, the communication manager of C, Ecobouwers:

“Yes, we do have a very loyal constituency anyway. We also have good contacts with them, so certainly the people who have participated in the open houses, who are also a manageable number of 130 people. We can contact all those people and we actually have good communication with them throughout the year, mainly in August through December. But yes, we do keep close contact with those and usually when visitors come to the open house. Who also ends up opening up themselves when they have renovated their homes.”

Also, the practitioner at F, River Cleanup mentions the importance of the community, but also the identification with the broader mission that the organization incorporates:

“That is very important for us. We have the people, the real regular people who participate a lot. The regular volunteers who participate, they mainly participate because they feel part of a bigger picture, feel part of a mission to which everyone who attends the events, contributes. So that is very nice, and we do notice that that is also the reason why people come again and again and again, so for us, it is extremely important that also in social media the word “We,” we use the word very much and also very conscious. For example, “We are not up to that.” It is ‘we' as a community that all those million and kilograms achieve, it is ‘we' that together organise events. That is very important to us, that everyone feels part of the broad mission.”

From these quotes, it is evident how important the aspect of community building and identification of the members with the goals of the NPOs is and how it is related to the descriptive norms as well.

4.5 Importance of telling a positive story

In contrast to descriptive social norms, the communication managers are quite hesitant to use injunctive norms in their social media communication. This is in the sense that they do not want to disapprove of certain behaviors toward citizens. On the contrary, almost all communication professionals stress the importance of bringing a positive story and never pointing fingers toward individuals. This becomes clear in the words of the communication manager of C, Ecobouwers “We try not to do that. Yes, no, we don't make judgements. We do try to of course to show what we think are good renovations, we do communicate about that a lot, but we're not going to make judgements…” Or by the practitioner at F, River Cleanup “Yes, I think we use that, but again, not in the negative.” The quantitative content analysis shows that 6.7% (n = 30) of the analyzed posts (n = 448) used injunctive norms. Looking at the included posts, the organizations utilize the injunctive norm more when it comes to celebrating and stressing the importance of doing good things for the climate. The injunctive norms are rarely found in the disapproving of certain behaviors of citizens. So, concerning citizens, the organizations find it very important to remain positive.

4.6 Thought leadership

Moreover, a simple chi-squared test also reveals a statistically significant correlation between injunctive norms and endorsing corporate responsibility (χ2 = 4.946, p < 0.05). This means that the organizations communicate about both the fact that something is important and that they approve of that, together with stressing that the organization is taking up their responsibility and doing its best to minimize environmental problems. Overall, endorsing corporate responsibility was used in 93 posts (20.8%). This is also in line with the communication professionals during the interviews stressing the importance of showing the non-profit organization as being an expert on the topics communicated about. For example, the communication manager of NPO B (European organization) says “It's one of our communication objectives. We want to be seen as the authority in circularity, in circular economy.” Both the interviews and the content analysis show the importance and focus on thought leadership within the organizations.

4.7 Different actors, different responsibilities

In contrast to the focus on being positive toward citizens and also about the organization itself (endorsing corporate responsibility), the NPOs have a more nuanced relationship with governments. This becomes clear when first looking at the extent to which the NPOs communicate about the fact that governments must take up their responsibility when it comes to environmental issues (n = 41, 9.1%) and comparing it to the extent that the NPOs communicate about the fact that the government is doing a good job at trying to minimize environmental problems (endorsing governmental environmental responsibility; n = 4, 0.9%). This discrepancy is also apparent in the interviews with some of the communication managers focusing on their role as an environmental non-profit organization to be critical toward the government. For example, the communication professional of A, Bond Beter Leefmilieu:

“Yes well, it's funny, because now that's not about disapproving of people's behavior or anything. But our policy experts have made a state of affairs of what the Flemish government, what has been promised and what has been achieved so far. And so they have written articles about this In the insight (the newsletter).”

However, there was a big difference between the communication professionals' perspectives on this role as “watchdogs.” While some of the practitioners did see it as their role to sometimes even shame the government, others saw their relationship with the government as very constructive and wanted to applaud the things the government does. For example, the professional at E (Bos+):

“We also have to cooperate with her (the minister of environmental issues). If she goes to her third year of her legislature, so now to be almost in the fourth year of legislature. And they are not yet in a fourth, now at 600 hectares realised planted trees of the 4000 promised. You could use that and do all kinds of communication, but we don't. That is not the intention. We continue to be constructive, and we continue to work together.”

However, looking at the results of the content analysis, it does become clear that overall, none of the NPOs communicate that much about the things the government is doing well when it comes to minimizing environmental problems (n = 4, 0.9%).

Looking at the interventions focused on stating whose responsibility it is to act on environmental issues (citizens, corporations, or government responsibility), it becomes clear that there is a big difference between the emphasis on the actors. Whereas only 25 posts (5.6%) and 18 posts (4%) were focused on the fact that it's the responsibility of citizens and corporations, the government was focused on a lot more and is being stressed as responsible for doing something about these problems in 41 posts (9.2%; an example in Figure 1).

4.8 Feedback and dynamic social norms underutilized

Social comparison feedback is used in 17 posts (3.8%). The posts where this principle is used, for example, cover the fact that the Airport in Brussels is not tackling CO2-neutral planes in comparison to other airports in the world, or about the imbalance between some of the wealthiest people having a higher impact on environmental issues but paying less taxes in comparison to less wealthy people. The principle of feedback was also not top-of-mind during the interviews with the communication professionals. However, some of them are open to using them in the future, for example, the professional of E, Bos+ about social comparison feedback:

“I do want to. Like the best municipality, the most taxing municipality would get the golden label or something like that, you know. Putting competition into it, we don't do that enough yet. But I would like to go for that in the long run.”

Other communication professionals also state to use the feedback intervention quite often, however when giving examples, it becomes clear that it is more connected to the provision of descriptive social norms, by for example communicating about the number of people that attended an event, or the amount of waste being collected during an event. Last, during the interviews the communication professionals highlighted their use of the dynamic norms. However, looking at the results of the content analysis, dynamic norms are only provided in one post (0.2%). As you can see in the post (Figure 2) which translates as

“  Waauw, more and more people are coming up with a sporty or creative action to do their bit for a Flanders rich in woods.

Waauw, more and more people are coming up with a sporty or creative action to do their bit for a Flanders rich in woods.  Do you want to take action yourself? Then your commitment will get its own spot on our action platform. Take action, be supported and together we will go for more and better forests!

Do you want to take action yourself? Then your commitment will get its own spot on our action platform. Take action, be supported and together we will go for more and better forests!  link in bio

link in bio ”

”

The post states that more and more people are changing their behavior by coming up with actions to increase woods in the region. This low number of posts with dynamic social norms shows that in contrast to the beliefs of the professionals, this principle is not at all used often yet. This shows that it is possible to have a discrepancy between what the practitioners think they use, and what they post about on Instagram.

5 Discussion

The main aim of this paper is to discover in what ways environmental NPOs use and perceive interventions from the literature that could make the environmental identities of the community around the NPO more salient. As The SIA states, ingroup identification is crucial for individuals to derive their self-identities based on salient group norms, values, and social identities (Fritsche et al., 2018; Nigbur et al., 2010; Smith and Louis, 2008; Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). Therefore, it is imperative for NPOs to further increase group identification with the organization. From the interviews, it became evident that the NPO communication professionals are implicitly focusing on this by using advocates and personal communication with their members. Furthermore, showing advocates in their communication is a way of bottom-up approach that previous literature has applauded for enabling further pro-environmental social identities (Jans, 2021).

Descriptive social norms are by far the most used and top-of-mind intervention by the included NPOs, which also translates into them being the dominant intervention being studied in the literature. Although the provision of descriptive social norms has been shown to have a positive impact on PEBs (Farrow et al., 2017), it should be used with caution. More specifically, according to the model of norm regulated responsibility (Ai and Rosenthal, 2024), providing descriptive social norms can result in individuals evading their responsibility, which results in fewer PEBs. This relationship could be countered by different strategies. First, as the model predicts individuals to decrease their ascription of responsibility (Ai and Rosenthal, 2024), NPOs could combine the provision of descriptive social norms with a message on personal responsibility. Second, the model states that the use of injunctive norms can also decrease the negative impact of the descriptive norms on the ascription of responsibility (Ai and Rosenthal, 2024), so combining these two could also be an effective strategy. However, in this research, we found that these interventions were not yet significantly used together.

From the literature, it was assumed that the community around NPOs already have quite robust environmental values and self-identities (Buchs et al., 2012). This was further highlighted by the NPOs' communication professionals, as they have difficulties reaching the general public with their communication. Their primary audience is therefore consisting of people with environmental values and identities. Therefore, the activation of the environmental social identity of the NPO can result in strengthening the already existing environmental self-identities and making them salient (Wang et al., 2022). People with environmental values predominantly follow the NPOs' communication, which means that these individuals are likely to view the NPOs as part of their ingroup. Furthermore, the NPOs' communication would also be seen as behaviorally relevant (environmental problems and pro-environmental behavior). Bertoldo and Castro (2016) found that when individuals strongly identify with a group, they place greater importance on the extent to which group members approve or disapprove of certain behaviors, relying on injunctive norms rather than descriptive norms. Since the NPOs now reach mainly environmentalists, it could be interesting for them to use injunctive norms more. Based on the quantitative content analysis, we did find injunctive social norms used to some extent. However, from the interviews, it became evident that the communication professionals are quite hesitant to use injunctive norms. This while they immediately unify this with disapproving certain behaviors. Therefore, more dialogue between practice and theory is needed.

For individuals who don't strongly identify with the group, such as the general public, research shows they prioritize knowing what others do, making the provision of descriptive norms more important to them (Bertoldo and Castro, 2016). As the quantitative content analysis showed that NPOs use descriptive social norms a lot more than injunctive norms, it becomes clear that the current strategies are more focused on engaging with the general public. In contrast, according to the professionals, this is not the audience they are currently reaching, but according to the content analysis, it is the one they are targeting with their messages. This discrepancy between the current messages and the target audience can be improved by better segmentation. Furthermore, Chung and Lapinski (2024) also found that when people perceive the group as the in-group (strong identification and similarity), messages on dynamic social norms are more effective than messages on low descriptive norms. So, for reaching the current community around the NPO it could be interesting to use dynamic social norms more. However, the results showed that this is not the case yet, as this intervention was rarely used. Here we found another discrepancy between what the communication professionals perceive and do, as during the interviews they highlighted the use of dynamic social norms. Following Chung and Lapinski (2024) further, for individuals that are currently not within the community of the NPO, low descriptive social norms would be more effective than dynamic social norms. Reaching this general public without particular environmental values is the current goal of the NPOs.

The NPOs frequently emphasize their own responsibility in their communications, as well as their taking up their responsibility. According to the research by van der Werff et al. (2021), this communication could lead to an increased environmental self-identity for people identifying with the NPO. Moreover, this could also be the case for endorsing government environmental responsibility but the results of this study show that this intervention is only used in a few instances. Non-profit communication professionals heavily emphasize that the government should address environmental issues, but they seldom acknowledge the government's efforts to minimize them. However, according to the literature, endorsing governmental environmental responsibility could influence citizens' environmental self-identity, thus encouraging PEBs (van der Werff et al., 2021). This represents a missed opportunity for NPOs. While it is part of their role to hold governments accountable, they should also sometimes highlight the positive actions governments are taking. This could then positively affect citizens' environmental self-identity.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we examined how NPOs are using and perceiving interventions derived from the Social Identity Approach (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987) to help create salient environmental social identities, and in turn, strengthen environmental self-identities. This study answers the plea of prior researchers to look into identities-based interventions and focus more on the group-level pathway (Bouman and Steg, 2019; Jans et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021). By using a mixed-methods approach of both a quantitative content analysis and in-depth interviews, it was possible to capture both the frequency of communication interventions and the decision-making processes behind them. First, we found that descriptive social norms are the most frequently used intervention by NPOs. However, according to previous studies (Ai and Rosenthal, 2024), this could result in reduced personal responsibility, decreasing PEBs. Therefore, it would be beneficial to use descriptive social norms together with injunctive social norms or individual responsibility claims, which the study found is not the case today. Secondly, NPOs primarily engage with individuals who hold environmental values. Which is beneficial when looking at the opportunities for NPOs to make their communities' environmental self-identities salient. However, the current communication strategies (focused on descriptive social norms), are more suited for the general public with no particular environmental values (Bertoldo and Castro, 2016). Injunctive and dynamic norms, which were both found to be used minimally by the NPOs, would be more effective for the environmental community (Bertoldo and Castro, 2016; Chung and Lapinski, 2024). This leads to a current mismatch between audience and messaging, whereas effective segmentation is needed. Last, the NPOs communicate about their own activities in tackling environmental issues and therefore trying to create a perceived organizational environmental responsibility. When communicating about governments, NPOs emphasize government responsibilities related to environmental issues, but only minimally applaud them for doing a good job at taking up their responsibility. However, according to van der Werff et al. (2021), perceived governmental environmental responsibility is associated with an increased environmental self-identity and PEBs. In conclusion, to be able to tackle environmental issues, NPOs need to use their relationship with their communities of like-minded people to the fullest and make their environmental social- and self-identities salient. This study has focused on which interventions to use and what improvements NPOs could make, which could result in more environmental self-identities, and that way PEBs.

Based on this research, the following concrete recommendations for practitioners can be formulated. First, knowledge about interventions is crucial for communication professionals of NPOs to successfully implement them in their communication strategy. Providing best practice examples and training on the importance of interventions could be beneficial, particularly for smaller NPOs. Social norms interventions should be tailored toward the right target audiences, namely for people who identify strongly with NPO and have environmental values, injunctive social norms and dynamic norms should work best. Whereas, for people who do not identify strongly with NPO, descriptive social norms would be better (Bertoldo and Castro, 2016; Chung and Lapinski, 2024). Based on these insights they can refine their communication strategies by better tailoring their messages to target specific groups effectively. Moreover, posts with the use of descriptive social norms should integrate personal responsibility claims (Ai and Rosenthal, 2024). Next, positive governmental action should be acknowledged in the communication, besides the own NPOs' actions. Endorsing governmental environmental responsibility could influence citizens' environmental self-identity, thus encouraging PEBs. Last, community building and personalized communication are important for self-identification of the community. We highly encourage NPOs' communication professionals to keep focusing on this close relationship with participants of their events and followers of their social media.

7 Contributions, limitations, and future research

This research has made some important contributions to the field of environmental communication and pro-environmental behavior research. Until now, research on priming environmental self-identity has primarily focused on the personal pathway by providing information on individuals' past behavior. This research applies the Social Identity Approach (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987) to incorporate a broader range of identity interventions while considering both personal and group pathways that focus on environmental social identities, which in turn influence individuals' environmental self-identities and pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs). Methodologically this research made contributions by exploring how NPOs use and perceive these interventions from literature. The discrepancies we found between the NPO communication professionals' perspectives on interventions and their actual usage, highlight the suitability of the mixed-methods design, which ultimately provided the most valuable insights.

Even though this explorative study has made some valuable contributions, there are some limitations to the study. First, further empirical research is recommended to look into the relationships between the chosen interventions based on the SIA and their impact on social- and self-identities, as well as PEBs. Furthermore, empirical studies should also look into which specific interventions can increase the likelihood of people identifying with NPOs, as this will lead to further possibilities for NPOs communication. In addition, this study was based on textual analysis of Instagram posts, future research could explore the possibility of visual content analysis as a complementary approach. This research centered on the strategies used by communication managers on social media and their perspectives. However, future studies should consider the perspectives of readers of the post, for example by conducting reception studies. Such research could delve deeper into how much these readers identify with the communication and how the interventions explored in this study, enhance their environmental social- and self-identity.

Data availability statement

The dataset of the quantitative content analysis is also posted on the online repository: https://zenodo.org/records/14268304.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform's terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

ID: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the communication professionals of the environmental non-profit organizations for their willingness to cooperate with this research, as well as their very valuable input during the interviews. Furthermore, two bachelor paper students conducted preliminary interviews with two of the practitioners, which helped the authors with contacting them. We would also really like to thank them for this introduction and contribution. The LLM ChatGPT was used to assist in the writing process of this article. Specifically, the tool was asked several times for grammar and sentence structure improvement.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1445118/full#supplementary-material

References

Abrahamse, W., and Matthies, E. (2019). “Informational strategies to promote pro-environmental behaviour,” in Environmental Psychology: An Introduction, 2nd Edn, eds. L. Steg, and J. I. M. de Groot (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 418. doi: 10.1002/9781119241072.ch26

Ai, P., and Rosenthal, S. (2024). The model of norm-regulated responsibility for proenvironmental behavior in the context of littering prevention. Sci. Rep. 14:9289. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-60047-0

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Bertoldo, R., and Castro, P. (2016). The outer influence inside us: exploring the relation between social and personal norms. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 112, 45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.03.020

Bouman, T., and Steg, L. (2019). Motivating society-wide pro-environmental change. One Earth 1, 27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.08.002

Bouman, T., and Steg, L. (2022). Engaging city residents in climate action: addressing the personal and group value-base behind residents' climate actions. Urbanisation 7(1_suppl), S26–S41. doi: 10.1177/2455747120965197

Bouman, T., Steg, L., and Zawadzki, S. J. (2020). The value of what others value: when perceived biospheric group values influence individuals' pro-environmental engagement. J. Environ. Psychol. 71:101470. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101470

Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. Int. J. Qual. Methods 5, 12–23. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500304

Brick, C., and Lai, C. K. (2018). Explicit (but not implicit) environmentalist identity predicts pro-environmental behavior and policy preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 58, 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.07.003

Buchs, M., Edwards, R., and Smith, G. (2012). Third Sector Organisations' Role in Pro-environmental Behaviour Change—A Review of the Literature and Evidence. University of Birmingham.

Carfora, V., Zeiske, N., van der Werff, E., and Steg, L. (2022). Adding dynamic norm to environmental information in messages promoting the reduction of meat consumption. Environ. Commun. 16, 900–919. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2022.2062019

Carmin, J., and Bast, E. (2009). Cross-movement activism: a cognitive perspective on the global justice activities of US environmental NGOs. Env. Polit. 18, 351–370. doi: 10.1080/09644010902823550

Chung, M., and Lapinski, M. K. (2024). The effect of dynamic norms messages and group identity on pro-environmental behaviors. Communic. Res. 51, 439–462. doi: 10.1177/00936502231176670

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., and Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 1015–1026. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015

Claro Montes, C., Aránzazu Ferruz González, S., and Catenacci Martín, J. I. (2024). Social networks and the Third Sector: analysis of the use of Facebook and Instagram in 50 ngo in Spain and Chile. Rev. Latin. Comun. Soc. 2024:13. doi: 10.4185/rlcs-2024-2197

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th Edn. London: SAGE Publications.

Digital 2023: Global Overview Report (2023). Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-report (accessed May 15, 2024).

Domalewska, D. (2021). A longitudinal analysis of the creation of environmental identity and attitudes towards energy sustainability using the framework of identity theory and big data analysis. Energies 14:647. doi: 10.3390/en14030647

Fanghella, V., d'Adda, G., and Tavoni, M. (2019). On the use of nudges to affect spillovers in environmental behaviors. Front. Psychol. 10:61. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00061

Farrow, K., Grolleau, G., and Ibanez, L. (2017). Social norms and pro-environmental behavior: a review of the evidence. Ecol. Econ. 140, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.04.017

Fielding, K. S., and Hornsey, M. J. (2016). A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: insights and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 7:21. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121

Fritsche, I., Barth, M., Jugert, P., Masson, T., and Reese, G. (2018). A Social Identity Model of Pro-Environmental Action (SIMPEA). Psychol. Rev. 125, 245–269. doi: 10.1037/rev0000090

Gatersleben, B., Murtagh, N., and Abrahamse, W. (2014). Values, identity and pro-environmental behaviour. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 9, 374–392. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2012.682086

Gatersleben, B., and Van Der Werff, E. (2019). “Symbolic aspects of environmental behaviour,” in Environmental Psychology: An Introduction. The British Psychological Society, eds. L. Steg, and J. I. M. de Groot (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 198–206. doi: 10.1002/9781119241072.ch20

Gisev, N., Bell, J. S., and Chen, T. F. (2013). Interrater agreement and interrater reliability: key concepts, approaches, and applications. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 9, 330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.04.004

Glaser, B., and Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. doi: 10.1097/00006199-196807000-00014

Ho, S. S., Singer, N. R., Yang, J. Z., Post, S., Shih, T.-S., Chen, L., et al. (2023). Environmental debates in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: media, communication, and the public. Environ. Commun. 17, 209–217. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2023.2193025

Hogg, M. A., and Reid, S. A. (2006). Social identity, self-categorization, and the communication of group norms. Commun. Theory 16, 7–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00003.x

Hormio, S. (2023). Collective responsibility for climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 14:e830. doi: 10.1002/wcc.830

Hornsey M. J. Hogg M. A. (2000) Assimilation diversity: an integrative model of subgroup relations. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 4, 143–156. 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_03

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2023). Synthesis report of the IPCC sixt assessment report (AR6). Available at: https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6syr/pdf/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf (accessed May 15, 2024).

Jans, L. (2021). Changing environmental behaviour from the bottom up: The formation of pro-environmental social identities. J. Environ. Psychol. 73:101531. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101531

Jans, L., Bouman, T., and Fielding, K. (2018). A part of the energy ïn crowd: changing people's energy behavior via group-based approaches. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 16, 35–41. doi: 10.1109/MPE.2017.2759883

Jans, L., and Fielding, K. (2015). Group Processes in Environmental Issues, Attitudes, and Behaviours. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 239.

Keizer, K., and Schultz, P. W. (2019). “Social norms and pro-environmental behaviour,” in Environmental Psychology: An Introduction, 4th Edn, eds. L. Steg, and J. I. M. de Groot (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 179–188. doi: 10.1002/9781119241072.ch18

Lavuri, R., Roubaud, D., and Grebinevych, O. (2023). Sustainable consumption behaviour: Mediating role of pro-environment self-identity, attitude, and moderation role of environmental protection emotion. J. Environ. Manage. 347:119106. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119106

Mackay, C. M. L., Schmitt, M. T., Lutz, A. E., and Mendel, J. (2021). Recent developments in the social identity approach to the psychology of climate change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 42, 95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.04.009

Masson, T., Jugert, P., and Fritsche, I. (2016). Collective self-fulfilling prophecies: group identification biases perceptions of environmental group norms among high identifiers. Soc. Influ. 11, 185–198. doi: 10.1080/15534510.2016.1216890

Mermet, L. (2018). Pro-environmental strategies in search of an actor: a strategic environmental management perspective on environmental NGOs. Env. Polit. 27, 1146–1165. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2018.1482841

Nigbur, D., Lyons, E., and Uzzell, D. (2010). Attitudes, norms, identity and environmental behaviour: using an expanded theory of planned behaviour to predict participation in a kerbside recycling programme. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 49, 259–284. doi: 10.1348/014466609X449395

O'Connor, P., and Assaker, G. (2021). COVID-19's effects on future pro-environmental traveler behavior: an empirical examination using norm activation, economic sacrifices, and risk perception theories. J. Sustain. Tour. 30, 89–107. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2021.1879821

O'Keeffe, G. S., and Clarke-Pearson, K. (2011). The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 127, 800–804. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0054

Rabinovich, A., Morton, T. A., Postmes, T., and Verplanken, B. (2012). Collective self and individual choice: the effects of inter-group comparative context on environmental values and behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 51, 551–569. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02022.x

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Res. Nurs. Health 18, 179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211

Schäfer, M. S. (2022). The Internet of Natural Things, in The Handboek of International Trends in Environmental Communication, 1st Edn. New York, NY: Routledge, 514.

Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 10, 221–279. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60358-5

Smith, J. R., and Louis, W. R. (2008). Do as we say and as we do: the interplay of descriptive and injunctive group norms in the attitude-behaviour relationship. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 647–666. doi: 10.1348/014466607X269748

Soopramanien, D., Daryanto, A., and Song, Z. (2023). Urban residents' environmental citizenship behaviour: The roles of place attachment, social norms and perceived environmental responsibility. Cities 132:104097. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2022.104097

Sparkman, G., and Walton, G. M. (2017). Dynamic norms promote sustainable behavior, even if it is counternormative. Psychol. Sci.,28, 1663–1674. doi: 10.1177/0956797617719950

Sparkman, G., and Walton, G. M. (2019). Witnessing change: dynamic norms help resolve diverse barriers to personal change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 82, 238–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.01.007

Steg, L. (2018). Limiting climate change requires research on climate action. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 759–761. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0269-8

Sultana, B. C., Prodhan, M. T. R., Alam, E., Sohel, M. S., Bari, A. B. M. M., Pal, S. C., et al. (2024). A systematic review of the nexus between climate change and social media: present status, trends, and future challenges. Front. Commun. 9:1301400. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1301400

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/An-integrative-theory-of-intergroup-conflict.-Tajfel-Turner/3f6e573a6c1128a0b0495ff6ebb9ca6d82b4929d (accessed June 2, 2024).

Terry, D. J., Hogg, M. A., and White, K. M. (1999). The theory of planned behaviour: self-identity, social identity and group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 225–244.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell, 239.

Udall, A. M., de Groot, J. I. M., de Jong, S. B., and Shankar, A. (2020). How do I see myself? A systematic review of identities in pro-environmental behaviour research. J. Consum. Behav. 19, 108–141. doi: 10.1002/cb.1798

Udall, A. M., de Groot, J. I. M., De Jong, S. B., and Shankar, A. (2021). How I see me – a meta-analysis investigating the association between identities and pro-environmental behaviour. Front. Psychol. 12:582421. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.582421

van der Werff, E., Steg, L., and Keizer, K. (2013). The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 34, 55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.12.006

Van der Werff, E., Steg, L., and Keizer, K. (2014). I am what I am, by looking past the present: the influence of biospheric values and past behavior on environmental self-identity. Environ. Behav. 46, 626–657. doi: 10.1177/0013916512475209

van der Werff, E., Steg, L., and Ruepert, A. (2021). My company is green, so am I: the relationship between perceived environmental responsibility of organisations and government, environmental self-identity, and pro-environmental behaviours. Energy Effic. 14:50. doi: 10.1007/s12053-021-09958-9

van Valkengoed, A. M., Abrahamse, W., and Steg, L. (2022). To select effective interventions for pro-environmental behaviour change, we need to consider determinants of behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1482–1492. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01473-w

van Wissen, N. A., and Wonneberger, A. (2017). Building Stakeholder Relations Online: How Nonprofit Organizations Use Dialogic and Relational Maintenance Strategies on Facebook. doi: 10.22522/cmr20170119

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., and Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 134, 504–535. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

Wang, X., Bouman, T., Van der Werff, E., Wang, Y., and Hardder, M. K. (2022). The Influence of Two Identities: How Environmental Self- and Group-Identities Predict Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Intentions in China. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.