- 1School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China

- 2Irish Studies Center, Dalian University of Foreign Languages, Dalian, China

This study conducts a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis guided content analysis of 56 Chinese government-sponsored poverty reduction posters across three historical stages since the founding of the People’s Republic of China to understand visual strategies, represented participants, and thematic shifts. Initially, visual strategies focus on action-oriented, collective agricultural activities. Over time, they shift to highlighting technological advancements and individual achievements, using “offer” images and various perspectives to engage viewers. Early posters predominantly feature peasants and collective groups, later expanding to include individuals and technological symbols, reflecting China’s socio-economic reforms. The thematic shifts move from collective efforts to targeted, locally-tailored strategies and the principle of “teaching people to fish,” mirroring broader socio-political transformations. This evolution underscores the role of visual media in shaping public understanding and garnering support for national policies. By highlighting the dynamic interaction between visual elements and socio-political contexts, the study reveals how government-sponsored media has adapted to effectively communicate the progress and objectives of China’s poverty alleviation efforts.

1 Introduction

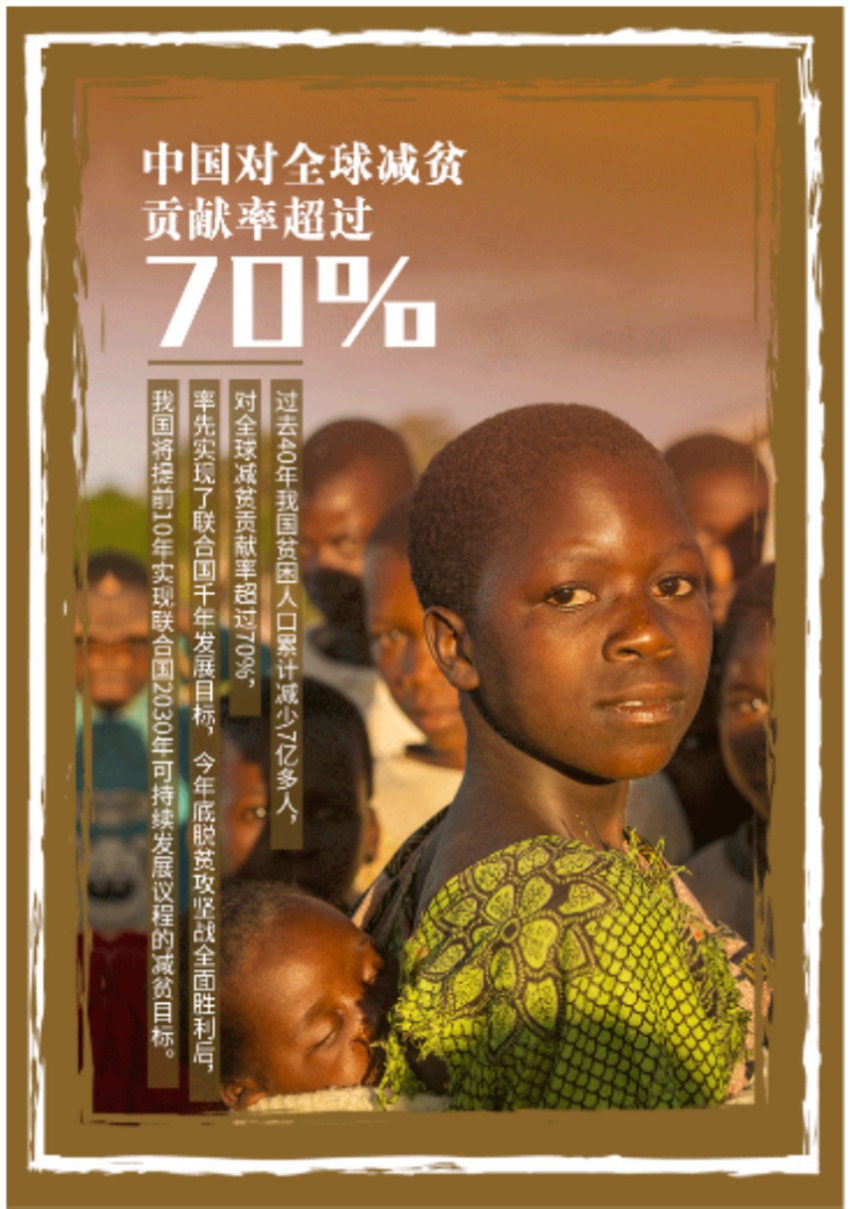

Poverty represents a global challenge, and its eradication is a collective international objective (United Nations, 2015). As the world’s most populous developing nation, China has historically prioritized poverty elimination and made remarkable progress. According to Poverty Alleviation: China’s Experience and Contribution, a white paper released by State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China (2021), China has managed to lift 770 million rural inhabitants out of poverty in the last 40 years, meeting both current domestic and the World Bank international poverty standards. This feat accounts for over 70% of global poverty eradication population during the same period, fulfilling one of the objectives of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development a decade ahead of schedule.

The “poverty alleviation” discourse forms an integral part of China’s political narratives, serving as a testament to its triumph over poverty and as a symbol of its endeavor to build a prosperous society with widespread affluence (Ji, 2020). This discourse is critical for understanding China’s poverty alleviation practices, narrating its efforts against poverty, and shaping the national image. Poverty reduction posters have proliferated across urban and rural landscapes nationwide. These posters convey messages through a synthesis of imagery, text, color, and spatial arrangement, offering a vibrant, intuitive, and graphic mode of information delivery. Therefore, analyzing the multimodal construction and features in these posters can contribute to understanding policy dissemination in contemporary China (Feng, 2023). Additionally, a comparative analysis of poverty alleviation posters from different historical stages reveals the evolving policies and socio-economic landscapes.

Despite their significance, there are few inquiries into the multimodal aspects of Chinese poverty reduction posters and the governmental advocacy they represent. This study seeks to fill this gap by conducting a multimodal critical discourse analysis and content analysis. It offers an in-depth examination of the posters across different historical phases of China’s poverty alleviation initiatives. This research aims to address the following questions:

1. How are visual strategies employed in Chinese poverty reduction posters?

2. What participants are represented in Chinese poverty reduction posters?

3. How does the thematic shift in Chinese poverty reduction posters reflect socio-political transformations in China?

2 Poverty reduction discourse

Poverty reduction discourse is a complex construct, that encompasses the language, narratives, and frameworks essential for conceptualizing and addressing poverty. Cornwall and Brock (2005) describe this discourse as an evolving amalgam of terminologies and concepts shaping development policies and practices. Poverty alleviation discourse reflects not only the strategies and policies aimed at reducing poverty but also the underlying beliefs and values guiding these strategies. It includes discussions on the causes of poverty, the means of addressing it, and the roles of relevant actors in this process.

Research on poverty reduction discourse employs diverse methodologies, predominantly qualitative in nature. Some studies focus on the theoretical and linguistic aspects of this discourse. For example, Wenden (2008) examines the transformative potential of language in addressing poverty and proposes a shift towards a caring economy. Cornwall and Brock (2005) critically assesses international development policy buzzwords such as “participation”, “empowerment”, and “poverty reduction”, exploring how different configurations of words frame and justify particular kinds of development interventions. Using corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis, Smith-Carrier and Lawlor (2016) examine the Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS) launched in Ontario, Canada, exploring the dominant discourses emerging from a genre chain produced by the Government of Ontario. Li (2020) adopts a pragmatics theory approach to analyze China’s poverty alleviation policy texts since the reform and opening up, revealing how the government shape the discourse system of poverty governance through policy documents, thereby achieving the goal of influencing the construction and development of the poverty alleviation. These studies underscore the importance of language and terminology in shaping poverty eradication strategies and public perception.

The media plays a significant role in shaping public understanding of poverty, as evidenced by studies examining its representation in various contexts. These studies delve into the portrayal of poverty in media, focusing on its impact on public perceptions. Kleut and Drašković (2020) examine representations of the poor across three genres, the government’s Bulletin on Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction, online news, and online user comments during the period following the expiration of the first Serbian Poverty Reduction Strategy (2010–2012). Zheng and Hui (2022) analyze the differences between Chinese and Western media in the usage of three discourse strategies in Chinese poverty alleviation discourses and the differences in readers’ perceptions of poverty alleviation discourses with or without discourse strategies of proximization. These works underscore the power of media discourse in influencing public understanding of poverty issues.

3 Government-sponsored posters in China

The comparison of Chinese poverty reduction posters with those from other countries reveals significant differences in their origins and objectives. O’Barr (2007) highlights that posters from other countries often originate from a mix of sponsors, including both government and private organizations, while Chinese poverty reduction posters are created, sponsored, or distributed by government entities. These posters serve to promote government programs, policies, or campaigns, raise public awareness, and encourage participation in government-led efforts. This contrast underscores the unique role of the Chinese government in influencing public discourse through visual media, a role less pronounced in the more decentralized systems of other nations.

Historically, government-sponsored posters in China emerged as potent tools of propaganda long before the Cultural Revolution, as discussed by Shen (2000). These early posters reflected widespread public enthusiasm for government initiatives, effectively disseminating messages that celebrated state achievements and bolstered governmental legitimacy. By 1953, the proliferation of such posters had solidified their role in shaping public perception and consolidating support for government actions, marking a pivotal period in their evolution as instruments of political communication.

Throughout periods of reform, the nature and function of government-sponsored posters in China have adapted to address contemporary social and economic challenges. Landsberger (2010) notes a shift in focus toward educational propaganda tailored to meet evolving societal needs, exemplified by campaigns like the 2003 initiative targeting public hygiene issues. These modern posters integrate elements of public service announcements, effectively conveying practical information while promoting broader governmental agendas aimed at improving citizen welfare.

Furthermore, Landsberger (2004) underscores the dual purpose of contemporary Chinese posters, which concurrently promote patriotism and disseminate public information. This dualism serves as a strategic approach by the government to address societal issues through visually compelling media, leveraging emotive imagery and persuasive messaging to foster national pride and collective responsibility. Such strategies resonate with historical precedents where propaganda art was instrumental in mobilizing public support for governmental objectives.

The ongoing evolution of government-sponsored posters in China reflects a deliberate continuity with past propaganda strategies, as Justice (2012) elucidates. Drawing on visual and ideological elements from historical posters, contemporary campaigns create a sense of historical legitimacy and cultural continuity, thereby reinforcing governmental narratives and objectives.

While previous research has delved into the linguistic and theoretical aspects of poverty reduction discourse and the media’s influence on public perceptions, a significant research gap exists in the specific analysis of Chinese poverty alleviation discourse through government-sponsored posters. Existing scholarship has thoroughly explored the evolution, functions, and impacts of government-sponsored posters in China, particularly in terms of their role in propaganda and public service announcements. However, there is a noticeable absence of focused studies on posters explicitly dedicated to poverty alleviation. These posters serve as tools of government-sponsored publicity, not only disseminating information but also embodying and reflecting the government’s strategies, ideologies, and approaches toward poverty alleviation.

4 Multimodal critical discourse analysis and content analysis

Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) is an interdisciplinary methodology that combines Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) with multimodal analysis to explore how various communicative modes such as text, image, and sound collaboratively create meaning and reflect or influence social power dynamics and ideologies (Hart, 2016). CDA focuses on how language use shapes societal power dynamics and ideologies, critically examining how dominant social classes manipulate social practices to protect their interests and exert ideological control (Fairclough, 1995; Machin, 2013). With the rise of multimedia technology and diverse information exchange methods, CDA has evolved to include a multimodal approach, integrating various forms of communication.

In media contexts such as television, film, print magazines, and online platforms, visual elements play a crucial role. These visuals convey messages that language alone cannot express. Texts use linguistic and visual strategies that may seem innocuous but carry ideological underpinnings, influencing the portrayal of events and individuals for specific purposes. MCDA has been developed by linguists such as Machin (2004), Kress and van Leeuwen (2020), O’Halloran (2004), Chouliaraki (2006), and Lemke (2006), who investigate how language, imagery, and other communicative forms converge to generate meaning. They propose that the principles of linguistic analysis, derived from Halliday’s (2004) systemic functional theory, apply equally to visual communication. The work of Kress and van Leeuwen (2020) has significantly shaped MCDA, contextualizing the analysis and interpretation of language within a broader semiotic framework, considering other resources used in meaning-making processes (Ledin and Machin, 2020).

Content Analysis (CA) complements MCDA by providing a systematic approach to analyzing communication content. Defined by Drisko and Maschi (2016) as “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use,” CA has evolved from its quantitative roots, notably advanced by Krippendorff in the 1980s, to incorporate qualitative approaches that interpret underlying meanings. Quantitative CA involves counting and statistically analyzing the frequency of specific words, themes, or patterns within a text, while qualitative CA interprets deeper, latent meanings through an inductive process (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Krippendorff’s contribution to CA has been pivotal, providing a comprehensive analytic framework that integrates both quantitative and qualitative techniques to capture the complexity of communication (Krippendorff, 1980).

The inclusion of visual elements in content analysis (CA) extends its methodological scope, making it crucial for understanding contemporary communication practices. Bell (2004) highlights the unique challenges of analyzing imagery with CA, arguing that visual content analysis is inherently more qualitative than textual content analysis due to the complex and often subjective nature of visual interpretation. According to Bell (2004, p. 13), content analysis is an empirical and objective procedure for quantifying recorded “audio-visual” (including verbal) representations using reliable, explicitly defined categories (“values” on independent “variables”). By systematically labeling the content of a set of texts, researchers can analyze patterns quantitatively using statistical methods, or qualitatively to interpret meanings within texts. This qualitative emphasis is essential for capturing the nuanced meanings conveyed through visual media, which play a pivotal role in fields such as media and cultural studies (Grabe and Bucy, 2009).

By integrating quantitative and qualitative techniques, CA allows researchers to uncover both explicit and implicit meanings in textual and visual data. This integration enhances the reliability and validity of CA, making it a robust tool for exploring complex research questions across various fields. The expansion to include visual analysis further enriches CA, enabling a more comprehensive examination of multimodal texts. The combined application of MCDA and CA provides a powerful framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of communication and its impact on social power dynamics and ideologies.

5 Data collection and analytic procedures

5.1 Data collection

The posters analyzed in this research were selected from an extensive collection issued by central and provincial governmental bodies in China as part of historical poverty alleviation campaigns. According to an announcement by the State Council Information Office of China (Xinhua Net, accessed on 17 March 2024), the nation’s poverty reduction efforts can be categorized into three principal historical stages: the Foundation of Poverty Reduction following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from 1949 to 1977, Rural Reform and Poverty Alleviation through Development spanning 1978 to 2011, and Targeted Poverty Alleviation aiming to Achieve Prosperity for All from 2012 to 2021. Using a stratified sampling method, we selected 56 posters from a total of 112, each representing distinct epochs of China’s poverty alleviation discourse. Specifically, the assortment comprised 15 posters from the foundational stage, 12 from the rural reform stage, and 29 from the targeted alleviation stage.

To apply principles of visual grammar, we employed a manual screening process based on two pivotal criteria. Primarily, the selection favored posters where visual elements took precedence, using textual content as ancillary support. This means the chosen posters predominantly utilize visuals to communicate their central message. Conversely, posters where text was the primary medium conveying the poverty alleviation strategy, capable of delivering the intended message without the need for visual imagery, were not included in this analysis. Following these guidelines led to the final compilation of 56 posters for this study.

5.2 Data analysis procedures

The analysis of Chinese poverty alleviation posters was executed in a structured three-step process to ensure a systematic examination of the visual and textual elements. Initially, posters were organized according to the historical stages of China’s poverty alleviation efforts, providing a chronological framework for a comprehensive analysis.

In the second step, a detailed visual analysis of the 56 posters was conducted, drawing upon the theory of Visual Grammar as proposed by Kress and van Leeuwen (2020). This involved a careful examination of each poster to identify key visual elements that significantly contribute to the conveyed message. According to Kress and Van Leeuwen, the analysis of visual images should encompass their representational, interactive and compositional meanings, echoing Halliday’s (2004) systemic functional grammar.

Representational meaning refers to what is depicted in an image and how it relates to the real world. It focuses on the content and the subjects within the visual representation. Kress and Van Leeuwen identify two key aspects of representational meaning: narrative process and conceptual process. Narrative processes depict actions, events, or processes, typically involving actors and goals, showing dynamic relationships and often using vectors (lines that indicate direction) to represent movement or action. Conceptual processes depict more static and generalized categories, emphasizing classification, analytical structures, or symbolic meanings. They represent relationships in terms of class inclusion, part-whole relationships, and symbolic attributes.

Interactive meaning concerns the relations between the producers and the viewers of images. It deals with how the image engages the viewer and involves Image Act, Social Distance, Perspective, and Modality. Image Act refers to the imaginary relation established between represented participants in images and viewers. Inspired by Halliday, Kress and Van Leeuwen use the term “offer” for images that do not contain human or quasi-human participants looking directly at the viewer, offering the represented participants as items of information or objects of contemplation. Conversely, images where participants gaze directly at the viewer are termed “demand,” as the participant’s gaze demands that the viewer enter into an imaginary relation with them. Social Distance is related to the “size of frame”, including close shot, medium shot, and long shot. Perspective involves the angle and point of view from which the image is presented; high angles can indicate power or superiority of the viewer, while low angles can indicate the opposite. Eye-level angles suggest equality. Modality refers to the perceived truth value or realism of the image, with high modality images appearing more realistic and low modality images appearing more abstract or stylized (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2020: 115–143).

Compositional meaning relates to how elements within an image are arranged and how this arrangement contributes to the overall meaning. Key components of compositional meaning include Information Value, Framing, and Salience. Information Value is related to the placement of elements within the image, denoting their importance. Framing involves the use of boundaries or lines to connect or separate elements within an image. Salience refers to the different degrees of attraction by the elements for the viewer, creating a level of importance for each element.

Lastly, considering the textual elements within poverty alleviation posters are strategically placed to maximize communication effectiveness, the analysis was further enriched by exploring the textual elements including titles and central messages within the posters. This helped to summarize and trace the evolution of Chinese poverty alleviation storylines through different historical stages.

6 Findings

6.1 Representational meaning

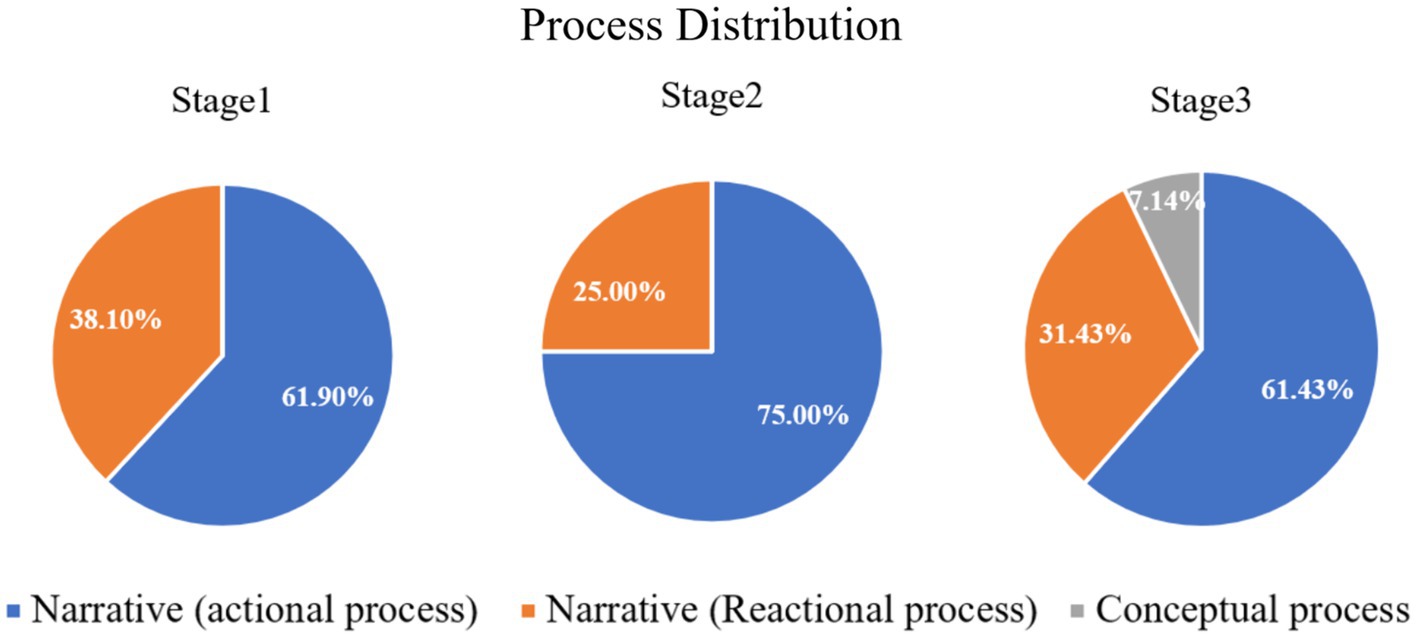

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of representational meaning across three stages of poverty alleviation efforts in China.

Synchronically, the dominant representational meanings in the posters are derived from narrative processes, specifically the actional and reactional processes. The actional process involves actions performed by participants, while the reactional process focuses on the responses of participants to various stimuli. According to Kress and van Leeuwen (2020), narrative processes illustrate dynamic relationships, often using vectors to represent movement or action. In contrast, conceptual processes depict static and generalized categories, emphasizing classification, analytical structures, or symbolic meanings, such as class inclusion and part-whole relationships. These narrative processes effectively depict dynamic activities and interactions, vividly representing the efforts and impacts of poverty alleviation initiatives.

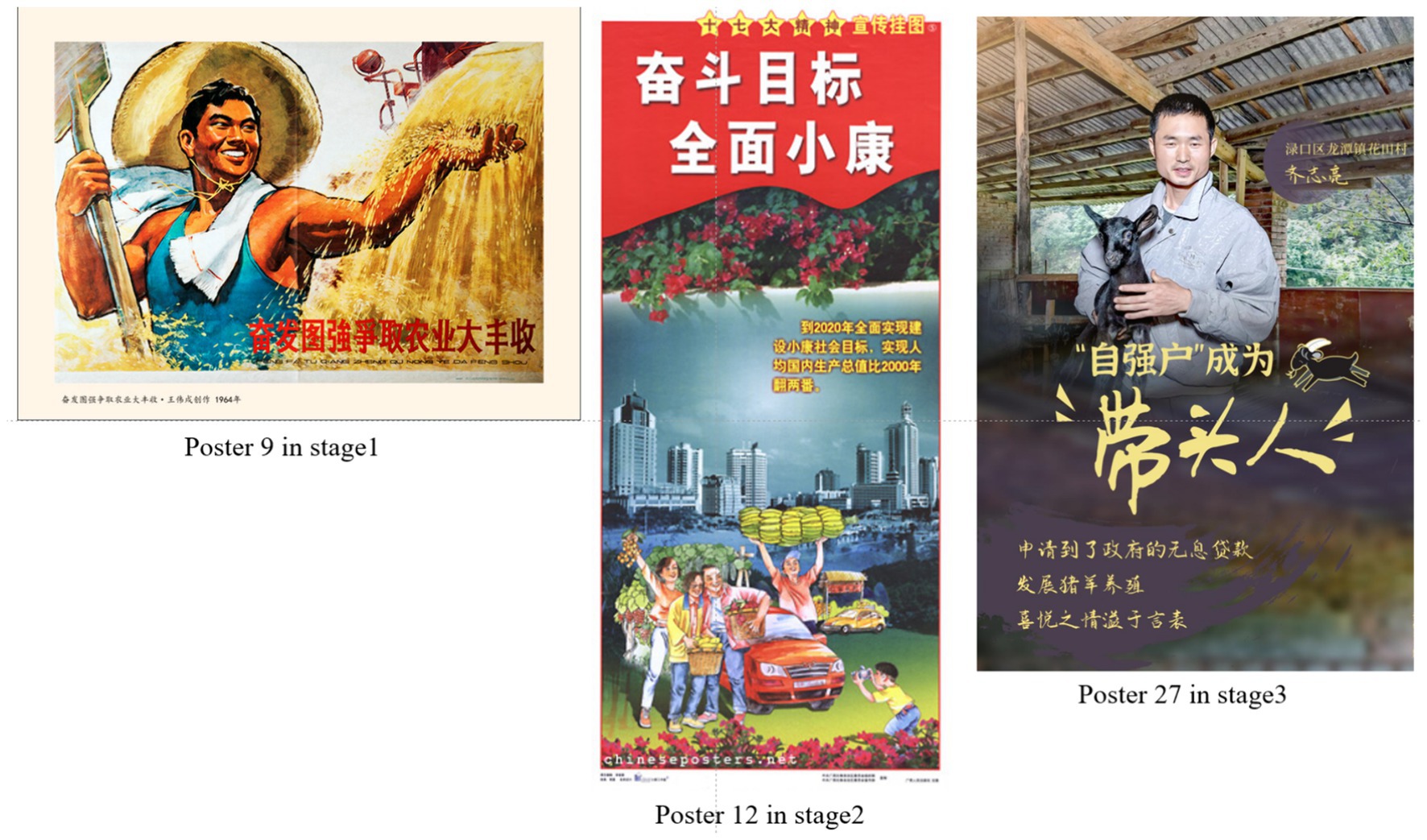

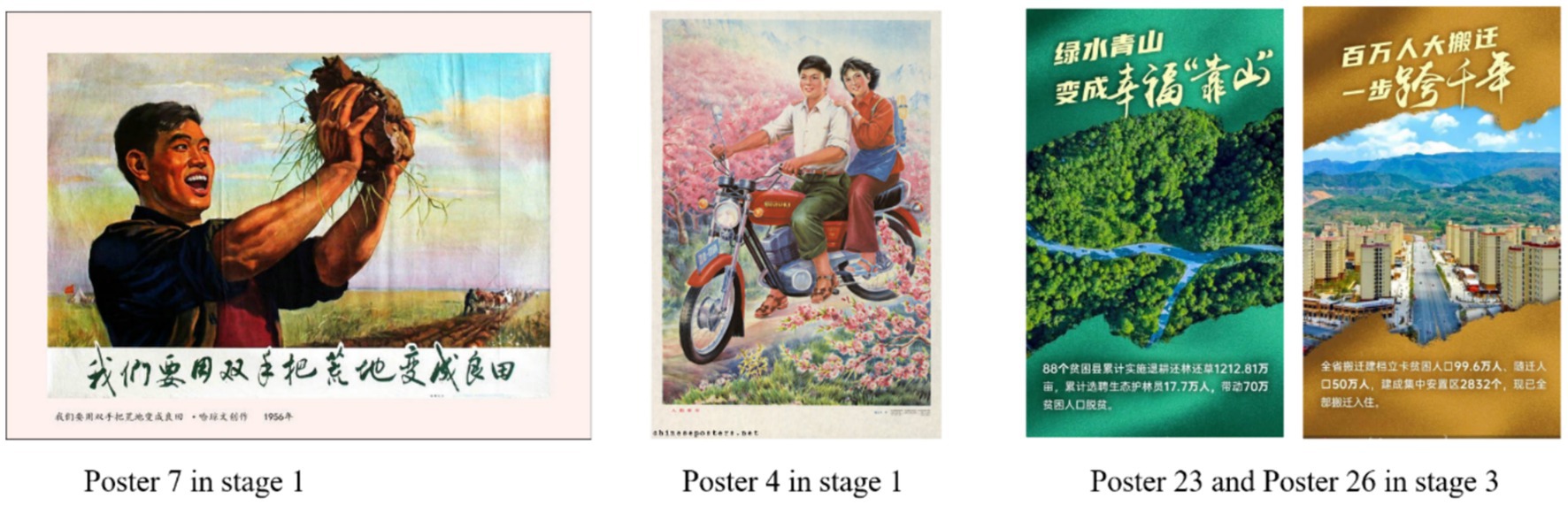

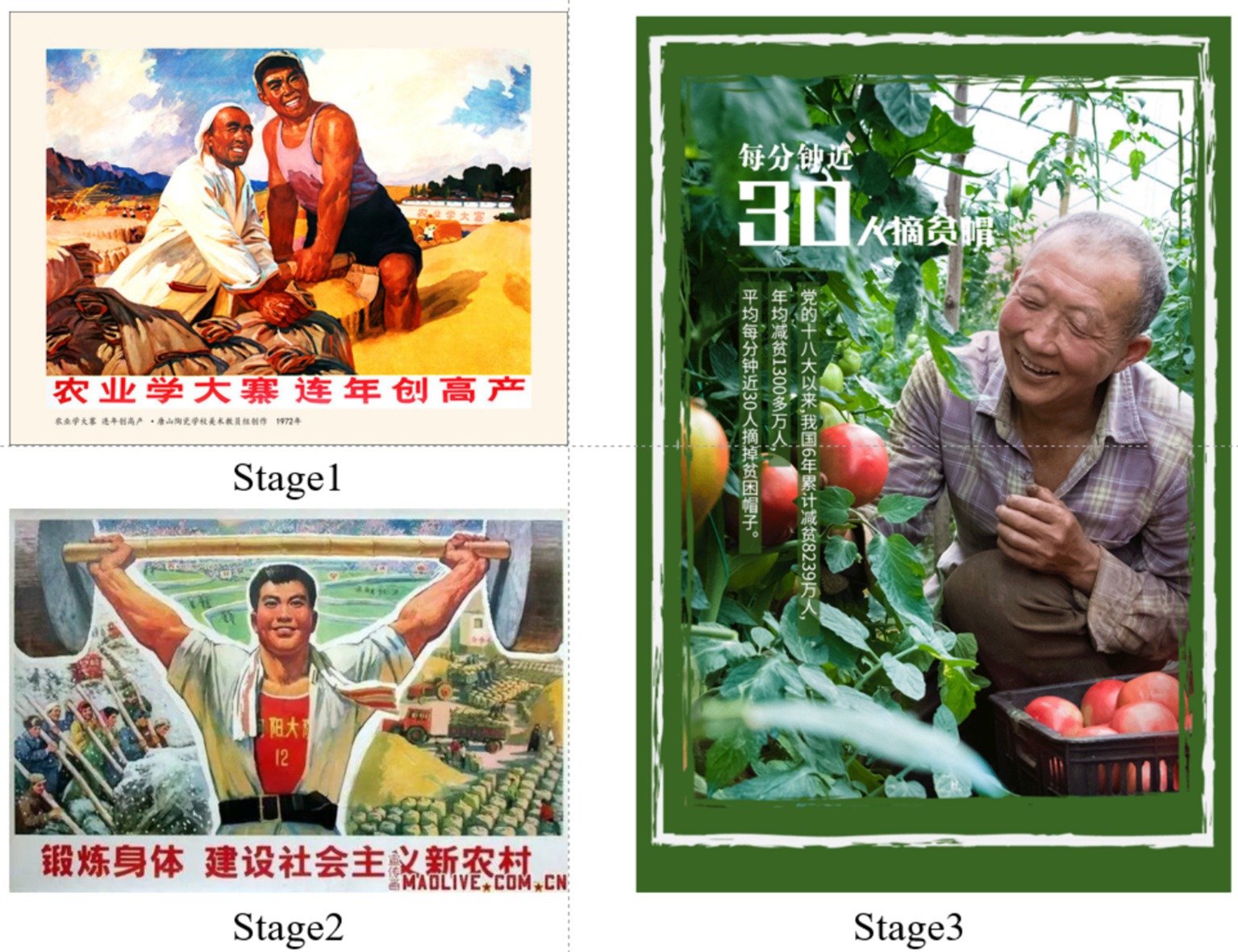

Diachronically, the distinction between the three stages shows the evolution of visual strategies over time. During the first stage, spanning from 1949 to 1977, a majority of the posters (61.9%) utilized actional processes. This stage is characterized by imagery focused on dynamic activities, emphasizing the collective efforts and physical labor involved in early poverty reduction initiatives. In the second stage, from 1978 to 2011, there is a noticeable increase in the use of actional process imagery, with 75% of the posters depicting dynamic activities. This period shows a significant boost in agricultural productivity and rural economic activities, with imagery highlighting the rapid development and transformative changes occurring in rural China. By the third stage, starting in 2012, there is a slight decline in actional process imagery to 61.43%. Additionally, the conceptual process is introduced in this stage, accounting for 7.14% of the visual resources. This stage includes imagery depicting abstract social and economic themes, such as sustainable development and technological advancements.

6.2 Interactive meaning

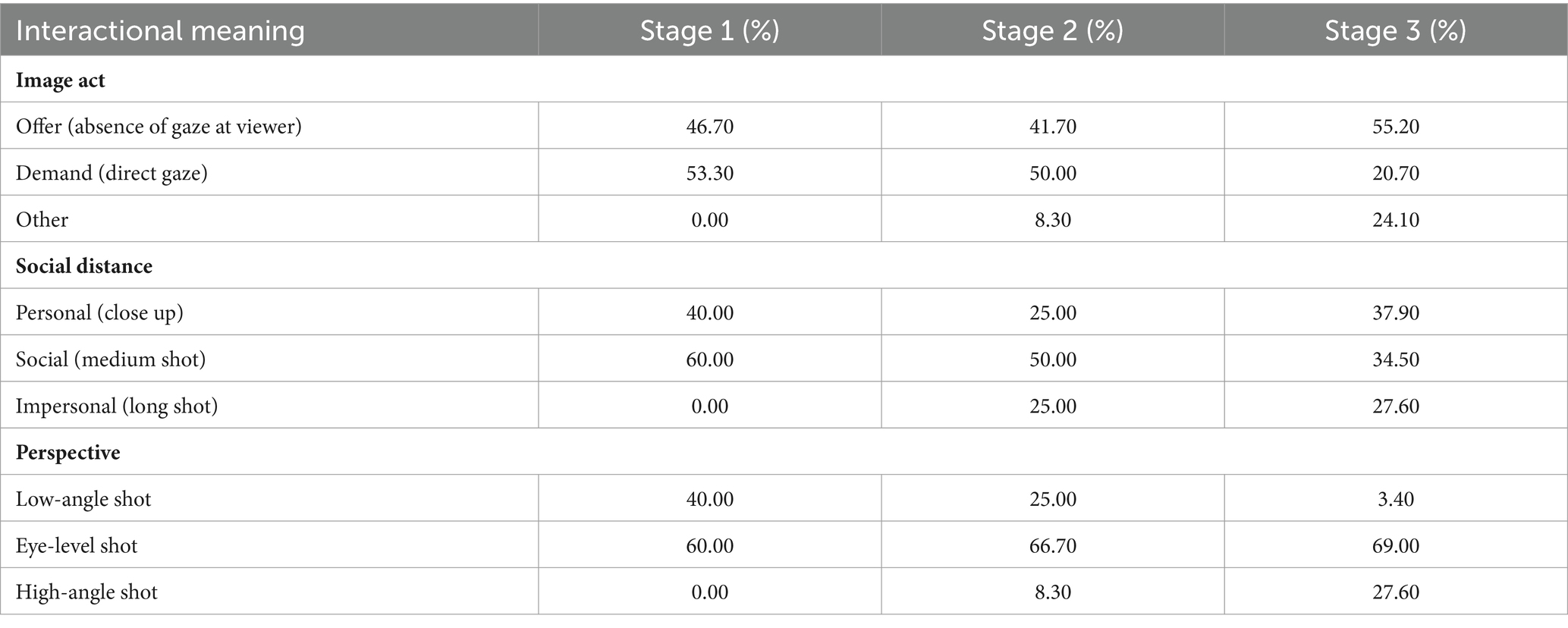

As shown by Table 1, the interactive meaning in Chinese poverty reduction posters reveals distinct visual strategies used across three stages.

Synchronically, across all three stages, there is a notable use of both “offer” and “demand” images, with varying emphasis on personal, social, and impersonal shots. Low-angle, eye-level, and high-angle shots are used to convey different perspectives, with a general trend towards maintaining viewer engagement through direct gaze and neutral perspectives.

Diachronically, the distinction between the three stages reveals changes in visual strategies over time:

In Stage 1, 53.30% of the posters are “demand” images, where participants gaze directly at the viewer, fostering an interactive relationship that invites the viewer into the scene. The “offer” images account for 46.70%, depicting participants looking away from the viewer, presenting the subjects as objects of contemplation. Personal (close-up) shots are used in 40.00% of the posters, emphasizing individual stories and personal connections, while social (medium) shots are the most common at 60.00%, offering a broad view of the participants within their environment. There are no impersonal (long) shots in this stage. Low-angle shots, used 40.00% of the time, often convey empowerment, while eye-level shots dominate at 60.00%, providing a neutral perspective.

In Stage 2, there is a slight shift with a decrease in both offer images (41.70%) and demand images (50.00%). Additionally, 8.30% of the posters do not feature human participants. The use of close-up shots drops to 25.00%, indicating a reduced focus on individual stories, while medium shots decrease to 50.00%. The introduction of long shots at 25.00% suggests an effort to provide more context by showing wider scenes and the environment. Low-angle shots decrease to 25.00%, while eye-level shots increase to 66.70%, maintaining a neutral perspective. High-angle shots appear for the first time at 8.30%, possibly introducing perspectives that emphasize the larger setting and context.

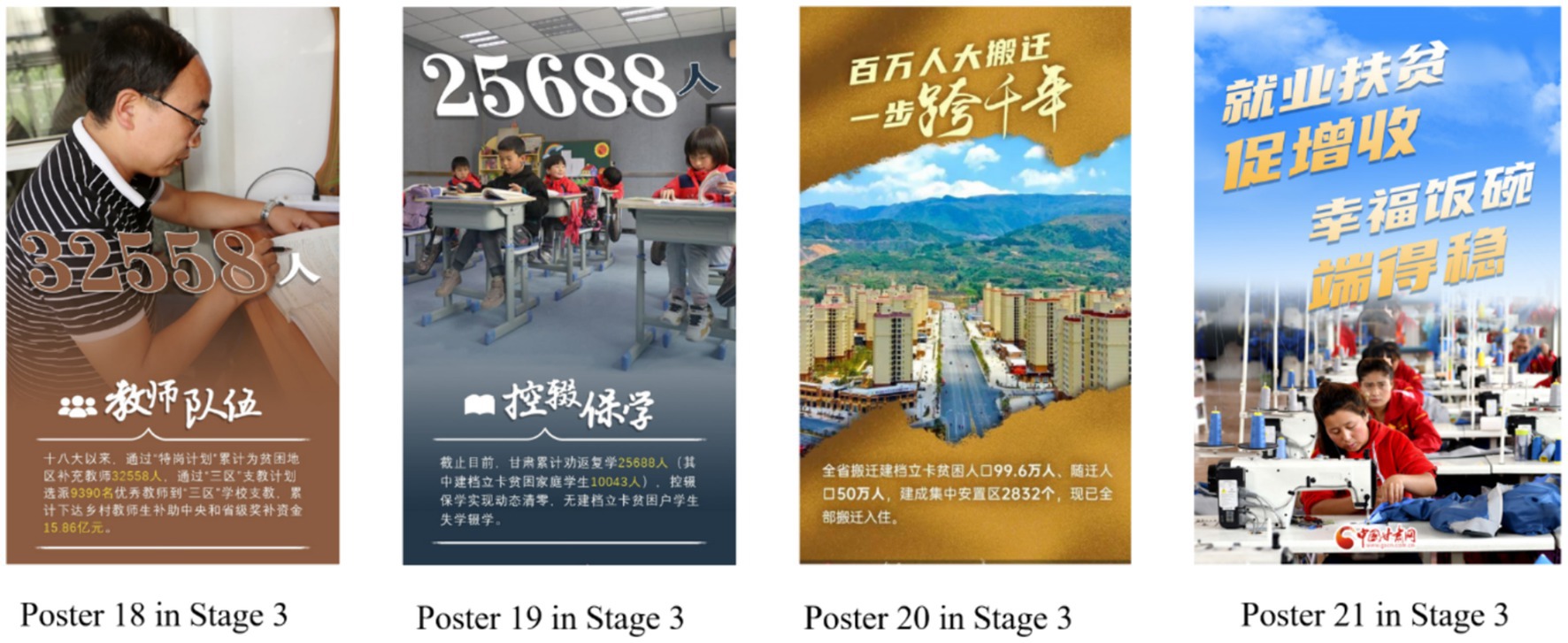

In Stage 3, there is a marked shift towards “offer” images, which increase to 55.20%, suggesting a greater emphasis on depicting scenes and actions over direct viewer engagement. “Demand” images drop significantly to 20.70%, and posters without human participants rise to 24.10%, reflecting diverse visual strategies. The use of close-up shots rises again to 37.90%, reflecting a renewed focus on personal stories, while medium shots decline to 34.50%. Long shots slightly increase to 27.60%, showing a continued emphasis on providing a wider view of the environment and socio-economic context. Low-angle shots drop sharply to 3.40%, representing a decreased focus on empowerment. Eye-level shots remain relatively stable at 69.00%, continuing the trend of neutral engagement. High-angle shots increase significantly to 27.60%, suggesting a greater emphasis on perspectives that highlight broader socio-economic contexts or the challenges faced by individuals.

6.3 Compositional meaning

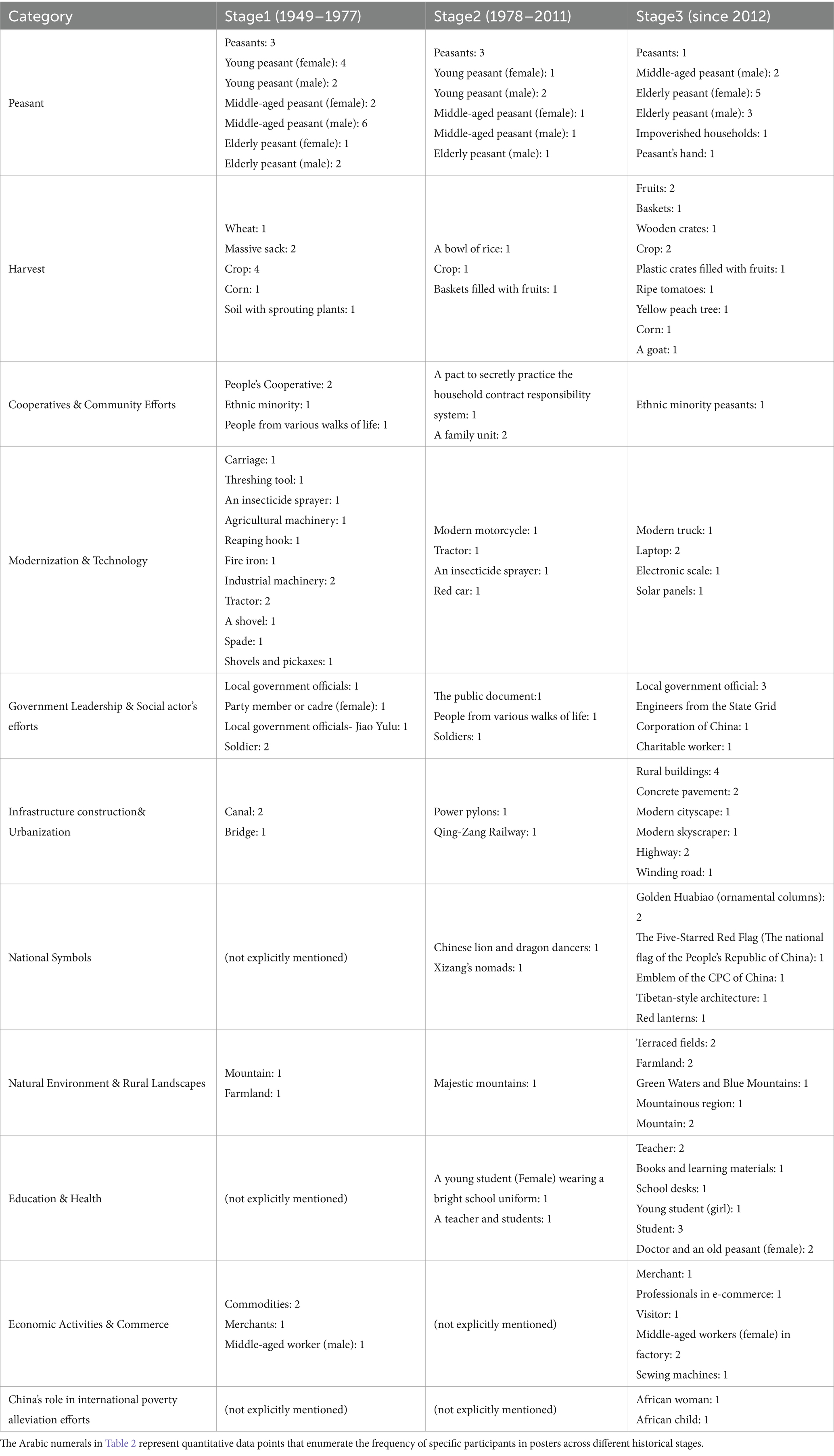

Salience is a crucial dimension of compositional meaning, classified into maximum salience and minimum salience. After analyzing 56 posters from the perspective of salience, the main participants in the images are identified (see Table 2).

The main participants in Chinese poverty reduction posters can be categorized into ten primary groups: Peasants, Harvest, Cooperatives & Community Efforts, Modernization & Technology, Government Leadership & Social Actors’ Efforts, Infrastructure Construction & Urbanization, Cultural & National Symbols, Natural Environment & Rural Landscapes, Education & Health, and Economic Activities & Commerce.

In Stage 1 (1949–1977), the posters predominantly feature young and middle-aged peasants, with a notable number of male participants. The harvest category focuses on crops like wheat and massive sacks, highlighting agricultural productivity. Cooperatives and community efforts emphasize People’s Cooperatives and ethnic minorities. Modernization and technology are depicted through agricultural and industrial machinery. Government leadership and social actors’ efforts prominently include local government officials and soldiers. Infrastructure construction and urbanization are represented by canals and bridges. The natural environment and rural landscapes include mountains and farmland. Economic activities and commerce involve commodities and merchants.

In Stage 2 (1978–2011), the posters show a mix of young and middle-aged peasants, with fewer female participants. The harvest category includes crops and a bowl of rice. Cooperatives and community efforts depict family units and the household contract responsibility system. Modernization and technology feature insecticide sprayer, modern motorcycles and tractors. Government leadership and social actors’ efforts include public documents and soldiers. Infrastructure construction and urbanization are represented by power pylons and the Qing-Zang Railway. National symbols include Chinese lion and dragon dancers and Xizang’s nomads. The natural environment and rural landscapes include majestic mountains. Education and health feature a young student in a bright school uniform.

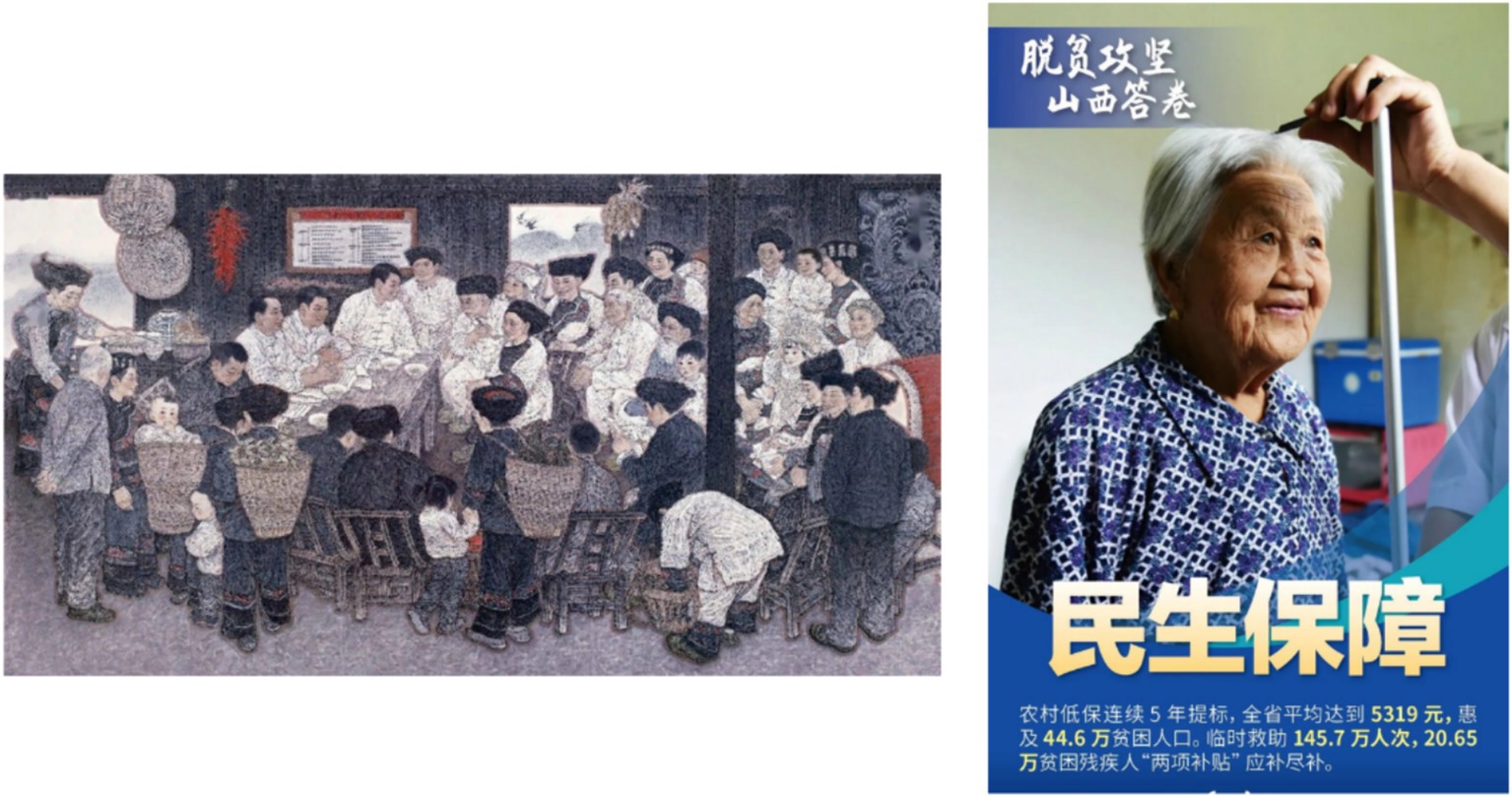

In Stage 3 (since 2012), there is an emphasis on elderly peasants and impoverished households. The harvest category shows diverse agricultural outputs, including fruits and crates. Cooperatives and community efforts depict ethnic minority peasants. Modernization and technology include modern trucks, laptops, electronic scale, and solar panels. Government leadership and social actors’ efforts feature local government officials, engineers and a charitable worker. Infrastructure construction and urbanization are represented by modern cityscapes, highway and rural buildings. National symbols include Golden Huabiao, the Five-Starred Red Flag, and Tibetan-style architecture. The natural environment and rural landscapes show terraced fields and green waters and blue mountains. Education and health include teachers and students, books, and learning materials. Economic activities and commerce feature merchants and professionals in e-commerce. China’s role in international poverty alleviation efforts is depicted through images of an African woman and child.

6.4 Poster title and central message

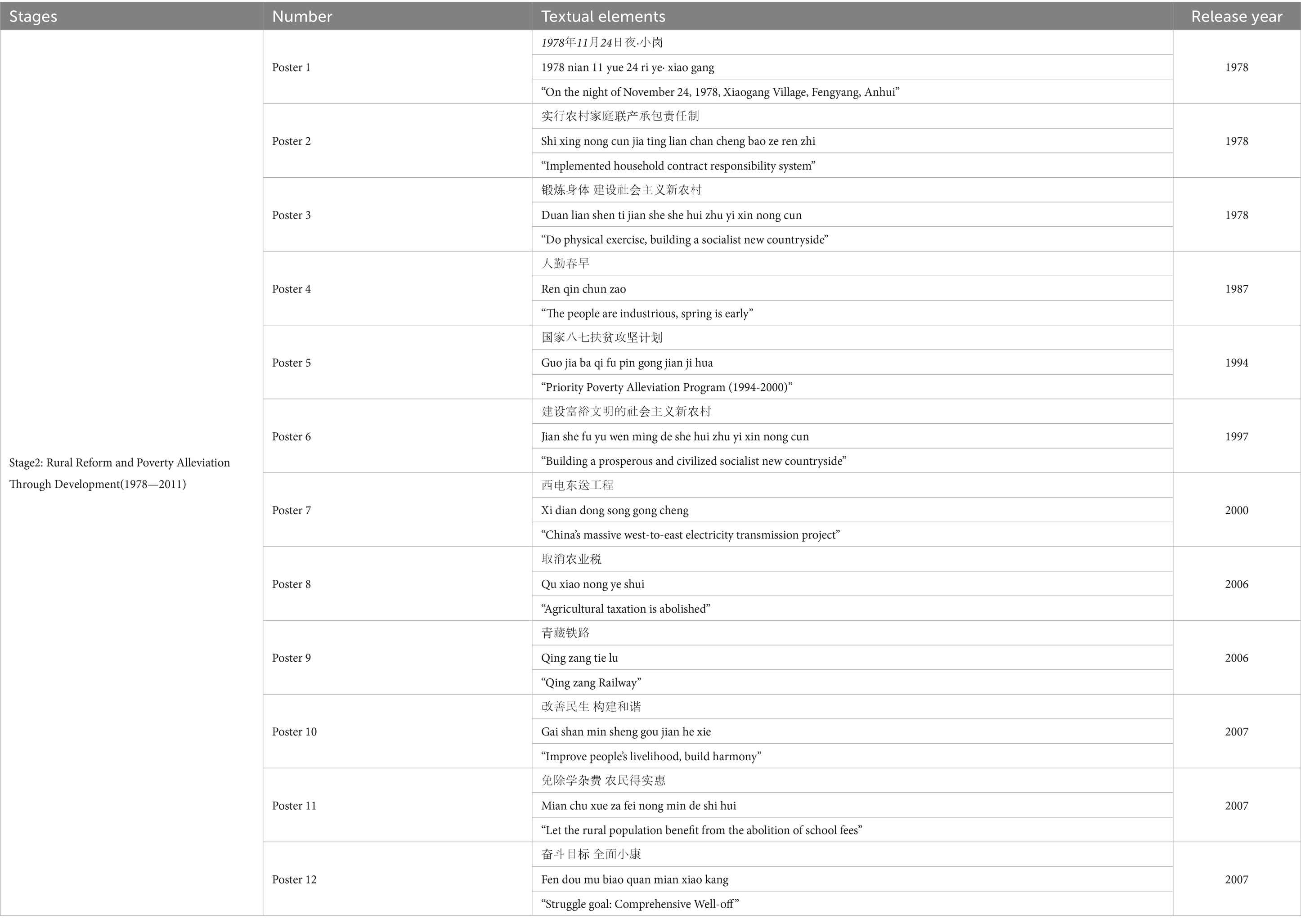

As illustrated by Tables 3–5, the titles and central messages of Chinese poverty reduction posters highlight the evolving themes and strategies in addressing poverty across three historical stages.

During Stage 1 (1949–1977), the posters prominently featured themes of cooperation, collectivization, and agricultural development. Central messages emphasized mutual aid, collective effort, and socialist principles in achieving prosperity and modernization. For instance, titles like “群众合作社” (“People’s Cooperative”) from 1950 and “参与互助合作是走向共同富裕的道路” (“Joining the mutual aid teams is walking the road to common prosperity”) from 1954 highlight the significance of cooperative farming. The emphasis on agricultural productivity and modernization is evident in titles such as “奋发图强争取农业大丰收” (“Strive with determination to achieve a bountiful agricultural harvest”) from 1964 and “为实现农业现代化贡献力量” (“Contribute to the modernization of agriculture”) from 1965. These posters collectively stress the socialist path to prosperity through cooperation and hard work.

In Stage 2 (1978–2011), the focus shifts towards rural transformation and advancement. Textual elements reflect the implementation of the household contract responsibility system, economic reforms, and major infrastructure projects. For example, titles like “实行农村家庭联产承包责任制” (“Implemented household contract responsibility system”) from 1978 and “建设富裕文明的社会主义新农村” (“building a prosperous and civilized socialist new countryside”) from 1997 underscore the importance of these reforms. Significant projects like the “西电东送工程” (“China’s massive west-to-east electricity transmission project”) from 2000 and the abolition of agricultural taxes in 2006 are also highlighted, showing the government’s efforts to improve living standards and economic conditions in rural regions.

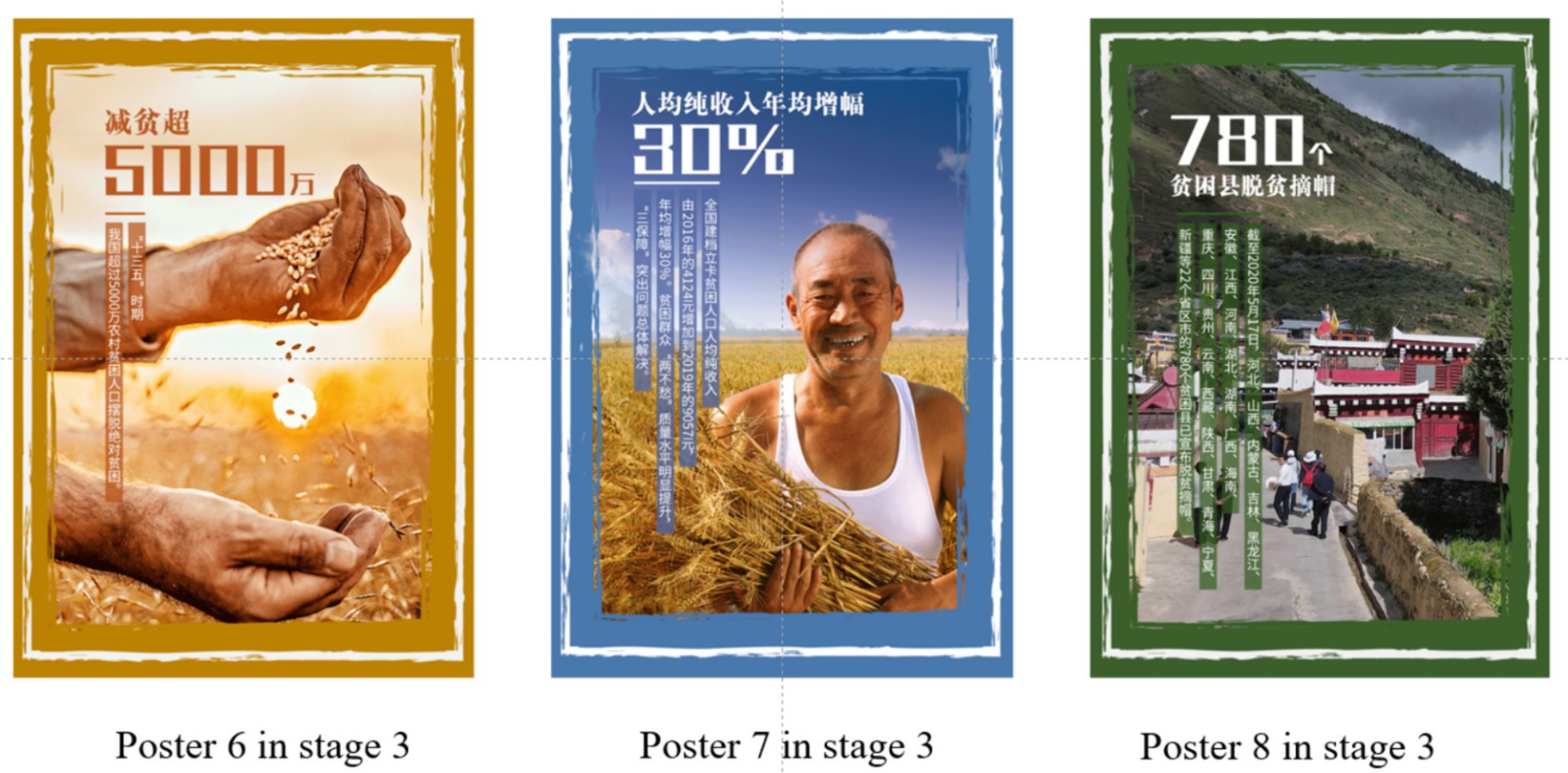

In Stage 3 (since 2012), posters focus on targeted poverty alleviation and the realization of prosperity, emphasizing precision in efforts and China’s contribution to global poverty alleviation. Titles such as “精准扶贫, 实施精准扶贫方略” (“Carry out a strategy of targeted poverty alleviation”) from 2013 and “减贫超 5000万” (“During the “13th Five-Year Plan” period, 50 million rural impoverished people were lifted out of absolute poverty”) from 2020 highlight the precision and impact of these efforts. The emphasis on China’s significant contribution to global poverty alleviation is captured in titles like “中国对全球减贫贡献率超过 70%” (“China’s contribution rate to global poverty reduction is 70%”) from 2020. These posters illustrate the comprehensive and targeted strategies employed to eradicate poverty and achieve nationwide prosperity.

7 Discussion

7.1 Visual narratives in Chinese poverty reduction posters

Chinese poverty reduction posters predominantly use narrative processes, as illustrated in Figure 1. Narrative processes, which depict actions, events, or processes involving actors and goals, significantly outnumber conceptual processes.

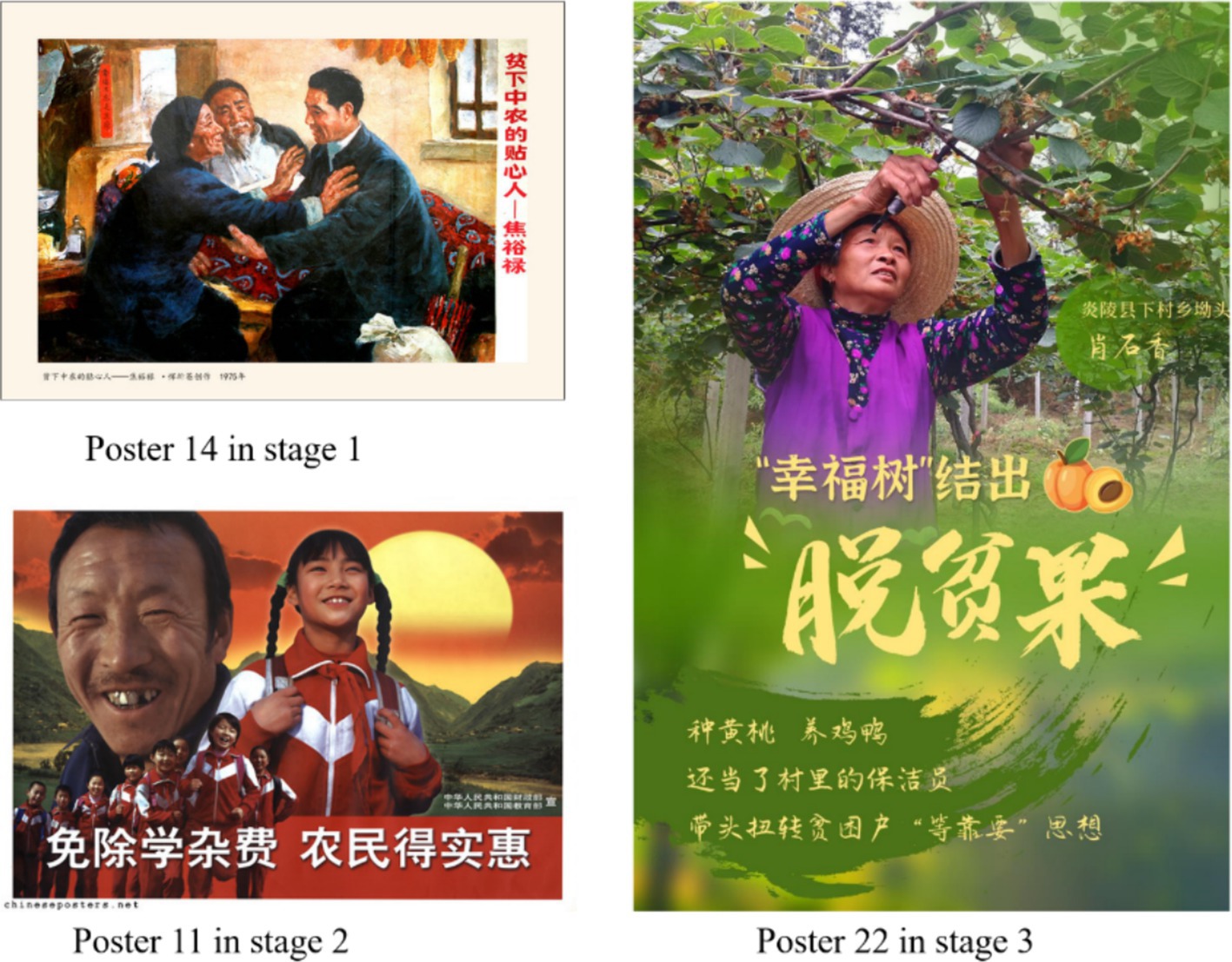

The preference for narrative processes in these posters can be attributed to the need for engaging storytelling and emotional connection. Narrative processes create dynamic interactions and actions that form storylines, making the message more engaging and emotionally compelling. For example, posters depict a family receiving aid, children attending school, or farmers harvesting fruits, showcasing the progress and impact of various initiatives through relatable stories of change and improvement (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Examples of narrative processes in Chinese poverty reduction posters. Reproduced from https://mbq.kongfz.com/detail_229486_1_2/, https://chineseposters.net/artists/prc-education-ministry and https://hn.rednet.cn/content/2020/12/10/8694223.html in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Narrative representations effectively evoke strong emotional responses by depicting real-life scenarios and interactions. These images highlight the struggles, efforts, and successes of individuals and communities affected by poverty, fostering empathy and a deeper emotional connection. By presenting relatable characters and situations, these posters motivate viewers to support poverty reduction efforts.

Within narrative processes, actional processes, which involve participants engaged in activities or movements, outnumber reactional processes, which focus on participants’ reactions to events or stimuli. Collected posters predominantly feature people, showcasing impoverished individuals and poverty alleviators as key social actors in the fight against poverty. Through these processes, narrative processes effectively illustrate the cause-and-effect relationships in poverty reduction, such as improved infrastructure leading to better living conditions or ensuring that children from impoverished families have access to education (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Examples of the cause-and-effect relationships. Reproduced from https://www.sohu.com/a/453213991_738124 and https://www.meipian.cn/2suxzoia in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Narrative processes often centre around people and their experiences, humanizing abstract concepts like poverty. By focusing on individual stories and journeys, these posters highlight the personal aspects of poverty elimination, making the issue more relatable and easier to understand for a broad audience. In contrast, conceptual processes, which classify and symbolize elements, present information in a more static and abstract manner, lacking the emotional engagement of narrative processes.

The three stages experienced distinctive differences in the deployment of visual strategies by posters. The first stage predominantly utilized actional processes to depict individuals actively participating in productive activities, reflecting the socio-economic themes of that era. The second stage saw an increase in actional process imagery, correlating with a focus on rural reform and development, emphasizing dynamic depictions of daily life and economic activities. In the third stage, there was a noticeable shift towards incorporating conceptual images that represent abstract ideas or symbols associated with poverty alleviation, linking concrete actions with broader themes of development and progress. This evolution in visual strategy suggests a more comprehensive approach to portraying poverty alleviation, combining vivid narratives with symbolic representations.

The primary goal of poverty reduction posters is to raise awareness, inspire action, and garner public support. Narrative processes are more effective in achieving these goals by creating compelling stories that resonate emotionally with viewers, making poverty alleviation efforts more immediate and urgent. In the Chinese cultural context, storytelling and the depiction of collective efforts align with cultural values and norms, making the message of poverty eradication more relatable and impactful. The Chinese government’s people-oriented development approach emphasizes human stories, fostering empathy and understanding among the public, and increasing support for poverty alleviation initiatives.

7.2 Producer-viewer interaction in Chinese poverty reduction posters

As illustrated in Table 1, the changes in visual strategies reflect shifting communication goals to engage viewers on multiple levels, from personal empathy to a broader understanding of socio-economic dynamics. The analysis of Chinese poverty reduction posters reveals distinct multimodal features that shape producer-viewer interaction. One prominent feature is the categorization of images into “offer” and “demand” types, each influencing viewer perception differently.

Among the 48 analyzed posters featuring “human” participants, 28 posters fall into the “offer” category, where the actors are depicted without direct eye contact with the viewers. “Offer” images provide a greater amount of information and appear more natural and spontaneous compared to “demand” images. In these posters, individuals are portrayed within a scene or narrative, focusing on their daily lives or work. Through the scenery, status, and content depicted in these images, viewers gain insights into the current way of life of individuals who were formerly impoverished and living in impoverished areas. Although there is no direct interaction between the viewers and the individuals in the image, viewers can genuinely sense their efforts to change their destiny from the perspective of bystanders. Furthermore, the weathered faces, rough hands, focused expressions, and heartfelt smiles of these individuals have a contagious effect on viewers, conveying their confidence in self-reliance and the happiness they have achieved (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Example of a human figure without direct eye contact with the viewers. Reproduced from https://kknews.cc/zh-hk/agriculture/e4gxxnn.html in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

In contrast, “demand” images directly engage with the viewer through eye contact, creating a connection that draws the viewer into an interactive relationship with the image. Such images serve to convey optimism and hope, as seen in the smiling faces of the participants who look towards a hopeful future. This depiction allows viewers to connect with the emotions of the characters. This direct engagement is powerful for evoking emotional responses and inspiring the viewer (see Figure 5).

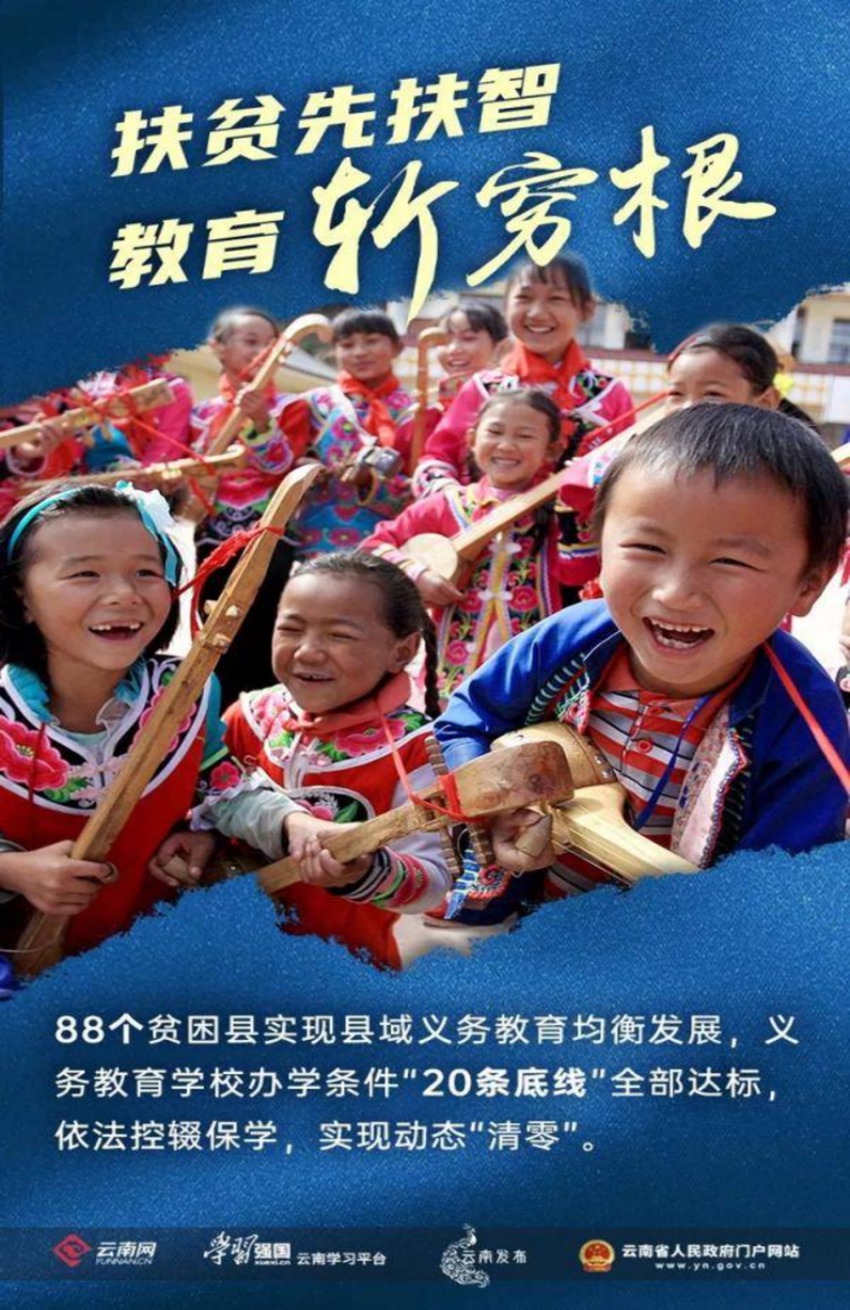

Figure 5. Example of smiling faces. Reproduced from https://ynfprx.yunnan.cn/system/2020/12/09/031167904.shtml in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

The prevalence of “offer” images in contemporary poverty alleviation posters signifies a strategic evolution in visual communication. This shift from earlier “demand” images towards “offer” images suggests a deliberate move towards storytelling. By focusing on depicting everyday scenarios and individual stories, these posters invite viewers to witness the tangible outcomes of poverty alleviation efforts. This approach not only underscores the effectiveness of governmental policies but also emphasizes the active role of poverty-stricken people in their own development journey. It portrays them not as passive recipients but as empowered agents of change, contributing to community and social progress.

From a diachronic perspective, an observable trend in the evolution of poverty alleviation posters is the increasing emphasis on constructing images characterized by an “impersonal (long shot).” The absence of “impersonal (long shot)” in Stage 1 suggests a direct and intimate approach to the viewer, perhaps to establish an immediate emotional connection with the subject matter, indicative of the initial phase of poverty alleviation where creating a personal connection and empathy was crucial. In the early stages, poverty alleviation efforts were more focused on individual stories to raise awareness.

Stage 2 demonstrates an equal distribution between “personal (close up)” and “impersonal (long shot)” at 25% each, with “social (medium shot)” making up 50%. This prevalence of medium shots indicates a visual strategic shift to depict communal efforts and social support systems, requiring fewer close-up shots. The use of medium shots balances the portrayal of individual narratives with broader community contexts, highlighting the role of social structures in poverty alleviation.

In Stage 3, compared to Stage 2, there is a notable increase in close-up shots, suggesting a renewed focus on individual narratives within the poverty alleviation posters, aligning with targeted poverty alleviation efforts. By zooming in on individuals through close-up shots, the posters aim to evoke empathy and highlight the personal challenges and triumphs in overcoming poverty. Meanwhile, the increase in long shots serves to contextualize these personal stories within larger community and societal frameworks, emphasizing the collective efforts towards social progress and development (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Examples of social distance at different stages. Reproduced from https://www.sohu.com/a/509607035_482071, https://chineseposters.net/posters/e15-926 and https://hn.rednet.cn/content/2020/12/10/8694223.html in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

The low-angle shot is predominantly used in the first two historical stages to objectively depict the peasants during the early years of the People’s Republic of China and reform and opening up (see Figure 7). This perspective makes the farmers appear taller and invokes a sense of awe in the viewer. The majority of the posters utilize an eye-level shot to depict scenes of labor or learning, placing the viewer on equal footing with participants and facilitating a sense of participation in the depicted scenes.

Figure 7. Examples of perspective at different stages. Reproduced from https://kknews.cc/zh-hk/agriculture/e4gxxnn.html, https://chineseposters.net/gallery/e15-518, https://www.163.com/dy/article/FTBRBG2L0514R9NO.html and https://www.163.com/dy/article/FTBHJ9890545AYLN.html in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

There has been a notable increase in the use of high-angle shots in the latest stage, as depicted in Table 1. Eight posters use a high-angle shot to showcase the impact of achievements. Although the complete picture is not shown, it allows room for the viewer’s imagination and conveys the accomplishments of precision poverty alleviation, environmental preservation, and relocation of people from inhospitable areas. This strategic choice aims to provide a broader perspective, allowing viewers to grasp the collective achievements and broad social changes, reflecting a community progressing toward unified goals and shared prosperity (see Figure 7). This visual strategy enhances the viewer’s engagement and underscores the narrative of collective effort and success in poverty alleviation.

7.3 Major represented participants in Chinese poverty reduction posters

The table serves as a tool to highlight the central themes and trace the evolution of representational participants across these varying historical stages, offering insights into how different elements have been emphasized or altered in the poverty alleviation posters over time (see Table 2).

In terms of Compositional Meaning, the maximum salience of the 56 analyzed posters predominantly features peasants, agriculture, and rural areas, reflecting the high importance of the san-nong (three-farm) problem, issues related to agriculture, farmers, and rural areas, for the country’s economic and social development (Ravi and Xiaobo, 2009) (see Figure 8). This emphasis underscores the central role of rural development in China’s poverty alleviation efforts across different historical stages.

Figure 8. Examples of san-nong related participants in Chinese posters on poverty alleviation. Reproduced from https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1741106523241915105&wfr=spider&for=pc, https://kknews.cc/news/3x64qbg.html and https://k.sina.cn/article_2332808060_8b0bd37c02000rytv.html?from=news&subch=onews in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

The evolution of Chinese poverty alleviation efforts is vividly depicted in government posters, showcasing a dynamic transition in the nation’s socio-economic landscape. In the first stage, the portrayal of peasants primarily features young and middle-aged rural workers, who were crucial for early poverty reduction initiatives. However, China’s rural society is transitioning from traditional to modern development, highlighting the large-scale transfer of rural young labor, the nucleation of rural families, and the impact on traditional rural family pension modes. The rural elderly, due to their vulnerable position compared to their urban counterparts, were more likely to fall into poverty, making their inclusion in poverty alleviation efforts particularly significant. In the later stages, posters increasingly depict elderly peasants, emphasizing support for vulnerable community members amid urban migration trends (see Figure 8).

This shift also includes highlighting the role of ethnic minorities and women in development efforts, recognizing their particular vulnerabilities due to geographical, historical, and cultural factors, and traditional gender roles (see Figure 9). These posters underscore the government’s commitment to inclusive development, addressing the needs of diverse groups within the rural population.

Figure 9. Examples of ethnic minority, the elderly and women peasants in stage 3. Reproduced from http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrbhwb/html/2020-09/17/content_2009441.htm and https://www.sohu.com/a/453213991_738124 in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

The agricultural category in Chinese government poverty reduction posters has evolved significantly over time. Initially focused on staple crops, it later expanded to include diverse outputs such as rice, fruits, and livestock, reflecting policy changes aimed at enhancing food security and diversifying the rural economy. This agricultural transformation was driven by replacing People’s Cooperatives farming with the household contract responsibility system, which tied farmers’ interests directly to their labor outcomes, significantly boosting their motivation and productivity (Zhaoxu and Liming, 2016).

Technological modernization has been another central theme, progressing from basic machinery to modern vehicles, high-tech devices, and renewable energy solutions. This progression illustrates China’s journey towards industrialization, economic growth, and innovation adoption. The poverty alleviation through science and technology model has played a crucial role in this journey, effectively improving the scientific and cultural quality of the population in poor areas and promoting the development of the rural economy and social undertakings (Yan, 2016).

Government leadership, initially portrayed through local officials and soldiers, has evolved to include a variety of social roles while maintaining a centralized governance approach. This evolution reflects the integration and expansion of resources and forces from all sectors of society in anti-poverty work, enhancing the level of anti-poverty initiatives. The emphasis on government leadership underscores its pivotal role in directing poverty alleviation and facilitating substantial infrastructural developments, from basic rural constructions to sophisticated urban infrastructure.

Recent poverty alleviation posters have increased the prominence of national symbols and richly depicted the natural environment, integrating poverty alleviation with national pride and ecological consciousness. The education and health sectors have received growing attention, recognized as vital for equipping the population with necessary skills and promoting sustainable economic growth. This shift highlights the holistic approach of China’s poverty alleviation strategies, which include significant investments in human capital development.

The portrayal of the economic landscape has evolved from manual labor to highlighting e-commerce and advanced industries, indicating China’s strategic pivot towards a digital economy and higher value-added sectors. This comprehensive portrayal underscores China’s multifaceted approach to poverty alleviation, from its agricultural roots through technological advancement to embracing a modern, inclusive, and sustainable development model.

In addition, the latest stage includes a poverty reduction poster featuring an African woman and child, highlighting China’s contributions to the international poverty alleviation cause and presenting China as a leader in addressing global poverty (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Example of China’s contribution to international poverty alleviation efforts. Reproduced from https://k.sina.cn/article_2332808060_8b0bd37c02000rytv.html?from=news&subch=onews in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

7.4 Poverty alleviation story lines in different history stages

Based on textual components extracted from poverty alleviation posters, poverty alleviation story lines in different history stages can be categorized. In the first historical stage, the storyline is characterized by “resolute and united efforts and sacrifice.” Posters from this period emphasize the advancement of productive forces, agricultural transformation, the development of individual craft industries, commerce, collective economy, agricultural cooperation, and improvements in irrigation and water conservation. The narrative centers on hard work and sacrifice as essential means to overcome poverty. This period also reflects the real conditions of China’s initial efforts to address widespread poverty, focusing on mobilizing the masses for collective agricultural productivity and infrastructure development.

The second stage, marked by the theme “rural reform and poverty alleviation through development,” reflects a new epoch of Chinese modernization, reform, and opening up. This period’s rapid economic and social development substantially boosted poverty alleviation efforts, significantly reducing poverty levels. The narrative focuses on the implementation of the household contract responsibility system, which tied remuneration directly to output, and reform agendas that liberated rural productivity and mobilized farmers’ labor motivation. Real conditions during this stage saw significant economic reforms that improved rural incomes and living standards, reducing poverty through increased agricultural output and market participation.

In the third stage, poverty elimination efforts are characterized by targeted poverty alleviation measures addressing the unique challenges of different regions or communities. The narrative branches into three storylines. The first storyline, “Harmonious and Beautiful Life,” showcases the improved quality of life of individuals who have successfully overcome poverty in rural areas. These posters feature village settings as the backdrop, highlighting rural architecture, agricultural tools, the natural environment, and unique geographical landscapes, emphasizing the social reality of underdeveloped rural regions. The second storyline, “Solid and Fulfilling Work,” highlights the efforts and dedication of rural residents in their journey out of poverty. This includes initiatives such as improving education in impoverished areas, infrastructure development, fostering specialty industries, relocating individuals from inhospitable regions, compensating for economic losses related to ecological conservation, and creating more employment opportunities. The third storyline, “Outstanding Accomplishments,” focuses on showcasing the achievements of poverty alleviation efforts. This stage employs titles reflecting targeted approaches, emphasizing specific numerical goals and measurable improvements, underscoring a shift towards precision in poverty alleviation efforts.

Posters in this phase of the poverty alleviation campaign feature images and text that emphasize precision and focus, utilizing specific numbers and percentages to convey the campaign’s targeted objectives. This strategic use of quantifiable data signifies a shift towards a more structured approach where specific goals and metrics are employed to gauge progress and direct efforts efficiently. The representational meaning of these posters underscores themes of accountability, progress, and tangible achievements in the ongoing fight against poverty.

Several posters highlight educational advancements, exemplified by Poster 18 and Poster 19, which focus on enhancing teaching staff, controlling dropout rates, and ensuring consistent schooling. This emphasis indicates a strong investment in future generations as a strategy to sustainably overcome poverty. Additionally, Poster 20 showcases significant improvements in rural community life with its striking imagery and compelling narrative of “Millions relocate in a grand exodus, bridging millennia in a single step.” This portrayal reflects the Chinese government’s efforts to relocate rural populations from areas with barren lands and underdeveloped infrastructure to regions more conducive to agricultural production and living, or to accelerate urbanization to improve living conditions (see Figure 11). Poster 21 highlights efforts to increase income for poor households, suggesting a broader strategy to bolster economic opportunities and foster entrepreneurship. This approach implies that the campaign includes comprehensive measures to stimulate local economies, thereby enhancing the overall economic landscape of impoverished regions.

Figure 11. Cases of education, rural community and economic growth in poverty reduction posters. Reproduced from https://gansu.gscn.com.cn/system/2020/11/13/012493138.shtml?from=timeline&isappinstalled=0, https://gansu.gscn.com.cn/system/2020/11/13/012493138.shtml?from=timeline&isappinstalled=0, https://www.163.com/dy/article/FTBRBG2L0514R9NO.html and https://www.163.com/dy/article/FRAUAMK705149T3G.html in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

The use of specific data points and success stories is pivotal in communicating the scope and ongoing impact of poverty alleviation efforts. By showcasing concrete examples of progress and success, the campaign not only informs but also inspires continued support and engagement from the broader public. This precise and detail-oriented approach, as depicted in the imagery and narratives of the posters (see Figure 12), serves to highlight the structured and methodical nature of China’s poverty alleviation efforts, reflecting a mature and strategic response to the challenges of poverty. It is important to highlight that the term “targeted anti-poverty policies” in phase three refers to a range of initiatives aimed at removing impediments and augmenting opportunities for impoverished individuals to extricate themselves from poverty and to strengthen their capacity for sustained poverty alleviation. This stage experienced significant government investment in education, health, and infrastructure, which facilitated measurable improvements in living standards and economic opportunities.

Figure 12. Cases of quantifying progress in poverty reduction campaign. Reproduced from https://k.sina.cn/article_2332808060_8b0bd37c02000rytv.html?from=news&subch=onews, https://k.sina.cn/article_2332808060_8b0bd37c02000rytv.html?from=news&subch=onews and https://k.sina.cn/article_2332808060_8b0bd37c02000rytv.html?from=news&subch=onews in accordance with Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

The Chinese approach to eradicating extreme poverty is deeply rooted in the venerable Chinese adage: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” The implementation of these policies recognizes that merely dispensing assistance, while occasionally indispensable, does not address the fundamental causes of poverty and may foster dependency. Consequently, the nation underwent a paradigm shift from a reliance on triage to proactive solutions—transitioning from mere aid to the empowerment of individuals. The provision of an enhanced environment conducive to self-sufficiency, enables the impoverished to become self-reliant and thus elevate themselves out of poverty (Zhang and Zuo, 2019).

8 Conclusion

Guided by Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis, this research conducts a content analysis of 56 Chinese government sponsored poverty reduction posters across three historical stages since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The study elucidates how visual and textual elements interact to convey messages of poverty alleviation.

Initially, the representations were heavily action-oriented, emphasizing collective agricultural activities and the central role of peasants, reflecting the collective spirit of early socialist China. Over time, the focus transitioned towards showcasing technological advancements and individual achievements, mirroring broader socio-economic reforms and the transition towards a market-oriented economy. This shift is not merely aesthetic but signifies a deeper ideological transformation, highlighting individual agency and technological innovation as drivers of progress. In the most recent phase, the introduction of conceptual images marks a sophisticated evolution in the government’s communication strategy, suggesting a shift towards more abstract and symbolic representations of poverty alleviation.

The analysis of producer-viewer interactions further underscores a strategic use of visual perspectives to foster a sense of connection and empowerment among viewers. The increasing use of “offer” images, long distances, and high angles positions the audience as both observers and participants in the narrative of poverty alleviation, reinforcing the message of collective progress and individual empowerment.

Moreover, the thematic exploration in the posters illustrates a concerted effort to align visual strategy with the national agenda of poverty alleviation. The portrayal of peasants and rural life remains consistent, yet the context in which they are depicted evolves. The depiction of environmental sustainability, education, and technological integration points to a holistic approach to development.

This thematic progression underscores the evolution of the four predominant poverty reduction strategies in China: government-led participation of all citizens, modernization through reform and opening up, targeted poverty alleviation with measures tailored to local conditions, and the principle of “teaching people to fish” rather than merely providing aid.

The content analysis of China’s poverty alleviation posters provides insights into the complex interplay between visual representation, policy evolution, and societal change. It reveals how government-sponsored media serves not just as a tool for information dissemination but as a potent mechanism for shaping public understanding and garnering support for national policies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

WL: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CD: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the reviewers for their insightful suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bell, P. (2004). “Content analysis of visual images” in Handbook of visual analysis. eds. T. Van Leeuwen and C. Jewitt (London: SAGE), 10–34.

Chouliaraki, L. (2006) The spectatorship of suffering. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781446220658

Cornwall, A., and Brock, K. (2005). What do buzzwords do for development policy? A critical look at ‘participation’, ‘empowerment’ and ‘poverty reduction. Third World Q. 26, 1043–1060. doi: 10.1080/01436590500235603

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. London: Longman.

Feng, D. (2023). Multimodal Chinese discourse: Understanding communication and Society in Contemporary China. 1st Edn. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Grabe, M. E., and Bucy, E. P. (2009). Image bite politics: News and the visual framing of elections. New York: Oxford University Press.

Halliday, M. A. K. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar, 3rd ed. Revised by Christian M.I.M. Matthiessen. London: Edward Arnold. doi: 10.4324/9780203431269

Hart, C. (2016). The visual basis of linguistic meaning and its implications for critical discourse studies: integrating cognitive linguistic and multimodal methods. Discourse Soc. 27, 335–350. doi: 10.1177/0957926516630896

Hsieh, H.-F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Ji, D. (2020). ‘中国扶贫对外传播的话语、媒介与策略’ (The narrative, media, and strategies of China’s poverty alleviation in international communication). Int. Commun. 282, 8–10.

Kleut, J., and Drašković, B. (2020). Discourses of poverty across genres: competing representations of the poor in the transitional context of Serbia. Discourse Soc. 32, 42–63. doi: 10.1177/0957926520961629

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2020). Reading images: the grammar of visual design. 3rd Edn. New York: Routledge.

Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 1st Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Landsberger, S. R. (2004). Propaganda posters in the reform era: promoting patriotism or providing public information? in: Frank Columbus (ed.), Asian Econ. Polit. Issues. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc., 10, 27–57.

Landsberger, S. R. (2010). “To spit or not to spit–health and hygiene communication through propaganda posters in the PRC–A historical overview” in Health communication: Challenge and evolution. (Beijing: Asia Media Research Center, Communication University of China), 7–32. Available at: https://chineseposters.net/sites/default/files/resources/landsberger-to-spit-or-not-to-spit.pdf

Ledin, P., and Machin, D. (2020). Introduction to multimodal analysis. Second Edn. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Lemke, Jay . (2006) Toward Critical Multimedia Literacy. International Handbook of Literacy and Technology, n.d. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203929131.ch1

Li, X. (2020). ‘改革开放以来我国扶贫政策话语研究——基于语用学理论的分析视角’ (Research on policy discourse of poverty alleviation in China since the reform and opening-up—a pragmatics analytical approach). Public Adm. Policy Rev. 9, 32–46.

Machin, D . (2004). Building the Worlds Visual Language: The Increasing Global Importance of Image Banks in Corporate Media. Visual Communication, 3, 316–336. doi: 10.1177/1470357204045785

Machin, D. (2013). What is multimodal critical discourse studies? Crit. Discourse Stud. 10, 347–355. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2013.813770

Ravi, K., and Xiaobo, Z. (2009). Governing rapid growth in China: Equity and institutions. 1st Edn. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Shen, K. (2000). Publishing posters before the cultural revolution. Modern Chin. Lit. Cult. 12, 177–202. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41490832

Smith-Carrier, T., and Lawlor, A. (2016). Realising our (neoliberal) potential? A critical discourse analysis of the poverty reduction strategy in Ontario, Canada. Critic. Soc. Policy 37, 105–127. doi: 10.1177/0261018316666251

State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China (2021) Poverty Alleviation: China’s Experience and Contribution. Available at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-04/06/content_5597952.htm (accessed 10 May 2024).

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development (a/RES/70/1). New York, NY: UN General Assembly Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

Wenden, A. L. (2008). Discourses on poverty: emerging perspectives on a caring economy. Third World Q. 29, 1051–1067. doi: 10.1080/01436590802201030

Zhang, Z., and Zuo, C. (2019) in The evolution of China’s poverty alleviation and development policy (2001–2015). ed. C. Zuo (Singapore: Springer).

Zhaoxu, L., and Liming, L. (2016). Characteristics and driving factors of rural livelihood transition in the east coastal region of China: a case study of suburban Shanghai. J. Rural. Stud. 43, 145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.12.008

Keywords: poverty reduction, government poster, multimodal critical discourse analysis, content analysis, visual grammar, China

Citation: Liu W, Du C and Liu F (2024) Communicating change: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of China’s poverty reduction posters. Front. Commun. 9:1444032. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1444032

Edited by:

Gemma San Cornelio, Fundació per a la Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, SpainReviewed by:

Raymond Drainville, University of Waterloo, CanadaAhlam Alharbi, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2024 Liu, Du and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chengcheng Du, Y2hlbmdjaGVuZy0xOTIzQG91dGxvb2suY29t

Wenyu Liu

Wenyu Liu Chengcheng Du1*

Chengcheng Du1*