- Department of Graphic Design, University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland

The aim of this study is to analyze the effect of an illustrator’s visual style in representing nature. The focus is on the author’s own artistic project in which the personal relationship with nature is reflected. As for theory, the style used in the representation is seen as a combination of semiotic resources. In this case, the style is inspired by historical images: old still life paintings and illustrations from natural encyclopedias and field guides. The stylistic influences work as a connotative semiotic resource. From a wider perspective, how we represent nature creates social discourses of nature and our attitudes toward it. The results indicate that fact-based communication of nature would also benefit from the emotional effect of esthetic imagery.

1 Introduction

The aim of this arts-based study is to analyze the effect of the visual style when representing nature. The focus is on my own art project where my personal relationship with nature is reflected. Theoretically, this article applies the concepts of visual style and cultural connotation used in the field of social semiotics. According to Theo van Leeuwen (2005, 26), the main interests in social semiotic research concern semiotic resources, their history and the ways they are used and developed in certain social and cultural context. As for semiotic resources, they have the potential for meaning making based on connotations with their past uses. Typical for cultural connotations is that they often convey ideas and values, rather than any specific people or places van Leeuwen (2005, 274). In the context of this study and my own works, a visual style is seen as a resource of meaning making, and especially the stylistic connotations as a crucial way of creating an overall atmosphere and meanings.

The works that served as material for this study (Figures 1–3) were created for a group exhibition of graphic designers called The End of the World (2023). My three works form a whole where I reflect my feelings about the end of the world in terms of nature. As a graphic designer, feeling somewhat foreign to the art world, I prefer to identify myself as an illustrator making pictures for everyday use. In other words, in this particular case, I hovered between the fields of applied and fine art for the context and my sources of inspiration. After all, the context of fine art offered me freedom to express my personal lifelong devotion to nature. My own relationship with nature is based on my early childhood experiences of nature as a miracle. This experience has later developed into a mental-visual reserve, combined with the images of the surrounding culture. In my childhood memories, fantastic texts and images of my grandfather’s natural encyclopedias from the early 20th century and illustrations of the old field guides of birds and insects merge with my experiences of wandering and exploring in real nature. During the study, I discovered that past representations of nature that were etched in my mind were just focused on the idea of nature as a miracle.

As a technique of my works, I used scanography, which I have versioned in commissioned illustration works in recent years (Raappana-Luiro, 2021). This technique, which I use by scanning natural objects and then manipulating images in PhotoShop, has potential to a special kind of visual style: The lighting created by a desktop scanner is not similar to what we have used to see in photographs. Also, the depth of field is different, giving the images the almost surreal precision of details. This “magical realism” creates stylistic connotations with my personal favorites: Still lifes from the Dutch Golden age and old natural history illustrations, including those made by biologist and illustrator Ernst Haeckel in the 1800-tale. In this essay, the way in which these stylistic connotations affect the meanings aroused in a contemporary artistic context—a semiotic change (see Aiello and Van Leeuwen, 2023, 41; van Leeuwen, 2005, 26)—is examined.

A social semiotic view of meaning making takes the meanings as unstable, reflecting broader social and cultural changes. Aiello and van Leeuwen (2023, 28) stress the importance of “…an approach which considers history and the historicization of meaning-making as the core components of all social semiotic endeavours.” By studying the history of semiotic resources—the past of contemporary contexts—and the values attached to them, it is possible to understand “how and why these resources came to be the way they are” (Aiello and van Leeuwen, 2023). Cultural connotations—or provenances, which term Kress and van Leeuwen also use –- is a way of creating meanings by reminding the viewer of some previous context in a new context, in which the semiotic resource has not been seen earlier. Provenances affect our interpretations of not only images but also more broadly of surrounding visual-material culture, such as fashion or interior décor (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2021, 250–251; Aiello and Van Leeuwen, 2023). The aforementioned potential of connotations to convey ideas and values is well suited to conveying the spirit of the historical era. When using historical style connotations for meaning making, it is also reasonable to make a short dive into the cultural history of representations of the nature as a miracle.

2 Nature as a miracle—historical sources of theme

Cultural connotations to earlier visual representations are like an infinite series of translucent layers of visual conventions, all of which offer semiotic potential for meaning making. Concerning the communicative use of historical styles, it is hard to use the semiotic potential of styles intentionally because of this layered infinity. Nodelman (1990, 64) notes, that “[b]ecause styles speak so strongly of the values of those who originated them, illustrators who borrow them may even evoke ideas and attitudes of which they are not themselves consciously aware” (see also Raappana-Luiro, 2022). The basis for my works were my personal experiences of nature as a wonder. Via the stylistic connotations to earlier representations of nature, the works convey the history of the ideas of nature as a miracle, thus participating in construing the whole theme of the pictures.

The organic relation of nature and culture in earlier periods grew to change at the threshold of the Early Modern Era. In the Late Medieval culture, nature began to be seen as the materialization of some cosmic power, as a miracle (Olalquiaga, 1988, 210–236; Stein, 2021). At the same time, the objects of nature gained a new, transcendental layer of meaning: Churches began to add miracles of nature—ostrich eggs, narwhal tusks and even man-made creatures constructed of parts of real nature or animals—side-by-side with relics (Olalquiaga, 1988, 210–236; Stein, 2021). The objects of nature became objects of culture with a transcendental aura (Olalquiaga, 1988, 210–236; Stein, 2021).

Natural history as a science developed in the interaction between renaissance artists, naturalists, and collectors, who shared a prevailing interest in describing, classifying, and collecting natural objects (Ogilvie, 2006, 13; Neri, 2011). Cabinets of nature curiosities were representations of this interest. They were sites of “contemplation, experimentation and study” (Geczy, 2019, 28). At the end of the seventeenth century, the culture of possessing, ordering, and observing objects came to a climax in Holland, and the concurrent genre of still life painting is seen as a parallel to cabinets of curiosities (Honig, 1998; Geczy, 2019, 26). The conventions of visual representation developed hand in hand with the culture of collecting and ordering things. In natural history, encyclopedias, still lifes, and cabinets of curiosities, combined a scientific standpoint with esthetic aims. Nature began to be represented as a collection of classified miraculous objects isolated from their natural surroundings (Neri, 2011, xii–xiii). This kind of “specimen logic” connected the visual style of the images and their purpose of classification (Neri, 2011). A widely influential example of the carefully detailed depiction of a specimen on an empty white background is Albert Dürer’s picture of a stag beetle in 1505 (Neri, 2011).

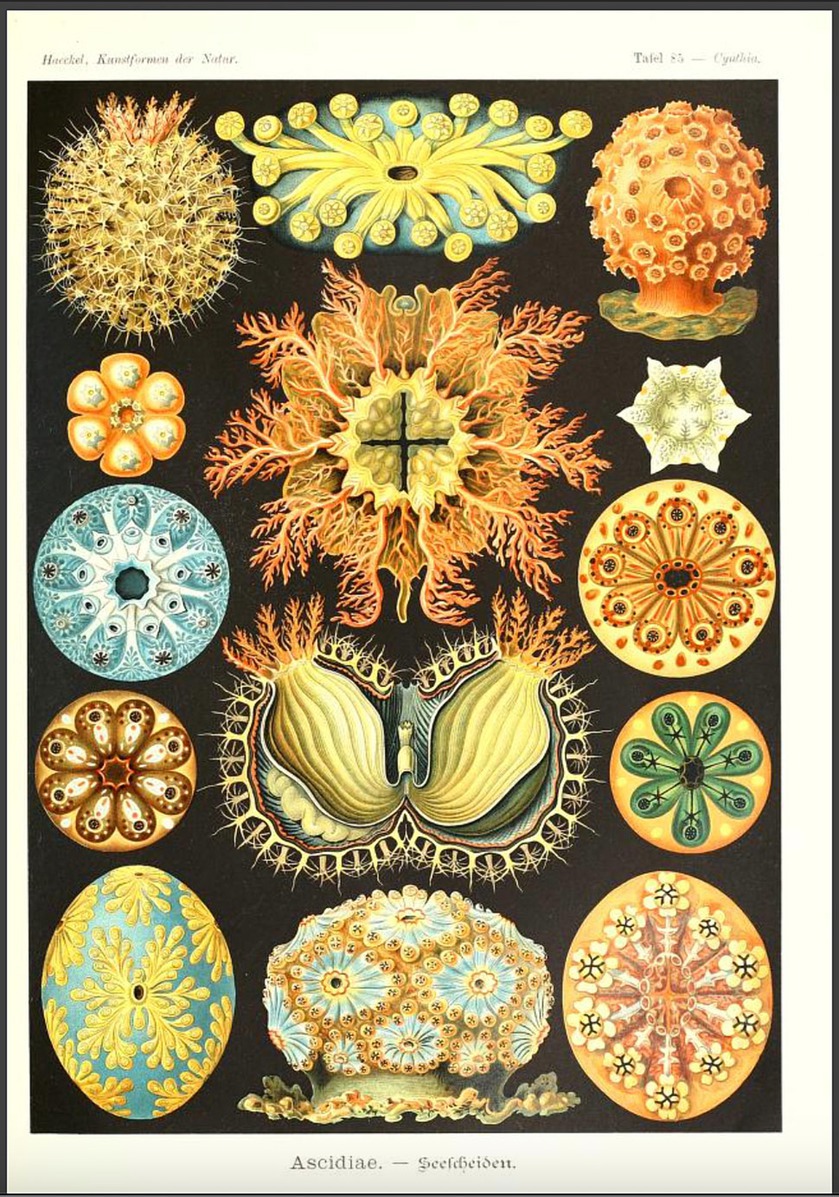

In all the cases mentioned above, objects of nature were seen through layers of cultural meanings. In medieval Christian miracles and Renaissance marvels, representations of nature were loaded with fantasy and esthetics until the earlier miracles were gradually given only an allegoric meaning: the attitude toward nature was shifting from the mystical to the rational (Olalquiaga, 1988, pp. 230–23). After all, there are still many nuances of the miraculous essence of nature even in 19th century nature philosophy and its visual representations. Romantic thinkers and biologists shared the idea of a connection between science and art: esthetic comprehension was considered equal to scientific understanding about the organic whole of nature (Richards, 2002, 12). Darwin (1859), as a committed adversary of any miraculous view of nature, uses words like “wonderful” and “beauty” numerous times in his On the Origins of Species. Using a similar literary style, Haeckel (1904), one of my stylistic sources of inspiration, entitled his book Kunstformen der Natur conveying the zeitgeist of the Romantic Era.

For Haeckel, as a Darwinist and adversary to the Christian doctrine of creationism, the wonder appeared in the everyday examination of life, and divinity was manifested in nature itself: in its beauty and order, where there could be found similar repeating structures in all creatures (Halpern and Rogers, 2013; Bauman, 2018). Haeckel’s illustrations, especially those presenting the world of submarine creatures, work as visual arguments about his theoretical thinking (Halpern and Rogers, 2013; Bauman, 2018). At first glance, they seem to be very naturalistic in their style. However, the miraculous in Haeckel’s depictions is in their absolute symmetry, precision, and detail. Additionally, as for the colored plates (Figure 4), the colors are almost unnatural in their deliciousness. It is easy to understand the popularity of Haeckel’s illustrations, especially as marine biology was quite a new field of biology at that time and the submarine world was still unknown both for Haeckel as a biologist and for the wider audience (Halpern and Rogers, 2013; Bauman, 2018).

Figure 4. Ernst Haeckel. 1905. Ascidiae. Kunstformen der Natur, plate 85 (https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/33543656).

In the 19th century, there prevailed a common interest in natural sciences also in the popular field of culture (Jovanovic-Kruspel, 2019). Rising urbanism, industrialization, and a wealthy middle class created a need for natural history museums, their nature dioramas being inherited from earlier cabinets of curiosities. The developments of printing methods made the mass production of images possible and numerous field guides and encyclopedias were published for new markets created by amateur naturalists. Illustrations made by skilled professional artists were reproduced or copied in books, on school wallcharts, and in collectible pictures hung on the walls of bourgeois homes. All these representations of natural history formed a kind of mass media of science, which was produced and consumed for didactic, popular scientific, and esthetic purposes (Jovanovic-Kruspel, 2019). This widely used popular imagery was then etched into the collective visual memory (Jovanovic-Kruspel, 2019). I found the copies of these images, including some Haeckel’s enthralling picture plates, also in my grandfather’s encyclopedias. Consequently, the discourse of the 19th popular natural history became part of my own mental-visual reserve through these books published in the early 20th century.

Nostalgia has become one of the contemporary megatrends. Some time ago I get a sample of printing paper, where there was printed an old watercolor illustration of a beetle on the white background. Luckily also my colleagues got their samples too, and soon they were hanging on our office walls. Many people are nowadays collecting old natural history wall charts and herbaria to decorate their homes. Maybe we long for the past times, where science looked nature with eyes of an skilled artist and nature was full of mystery and wonders – and maybe the whole theme of nature as miracle has its roots exactly in an esthetic experience.

3 Visual style as a semiotic resource

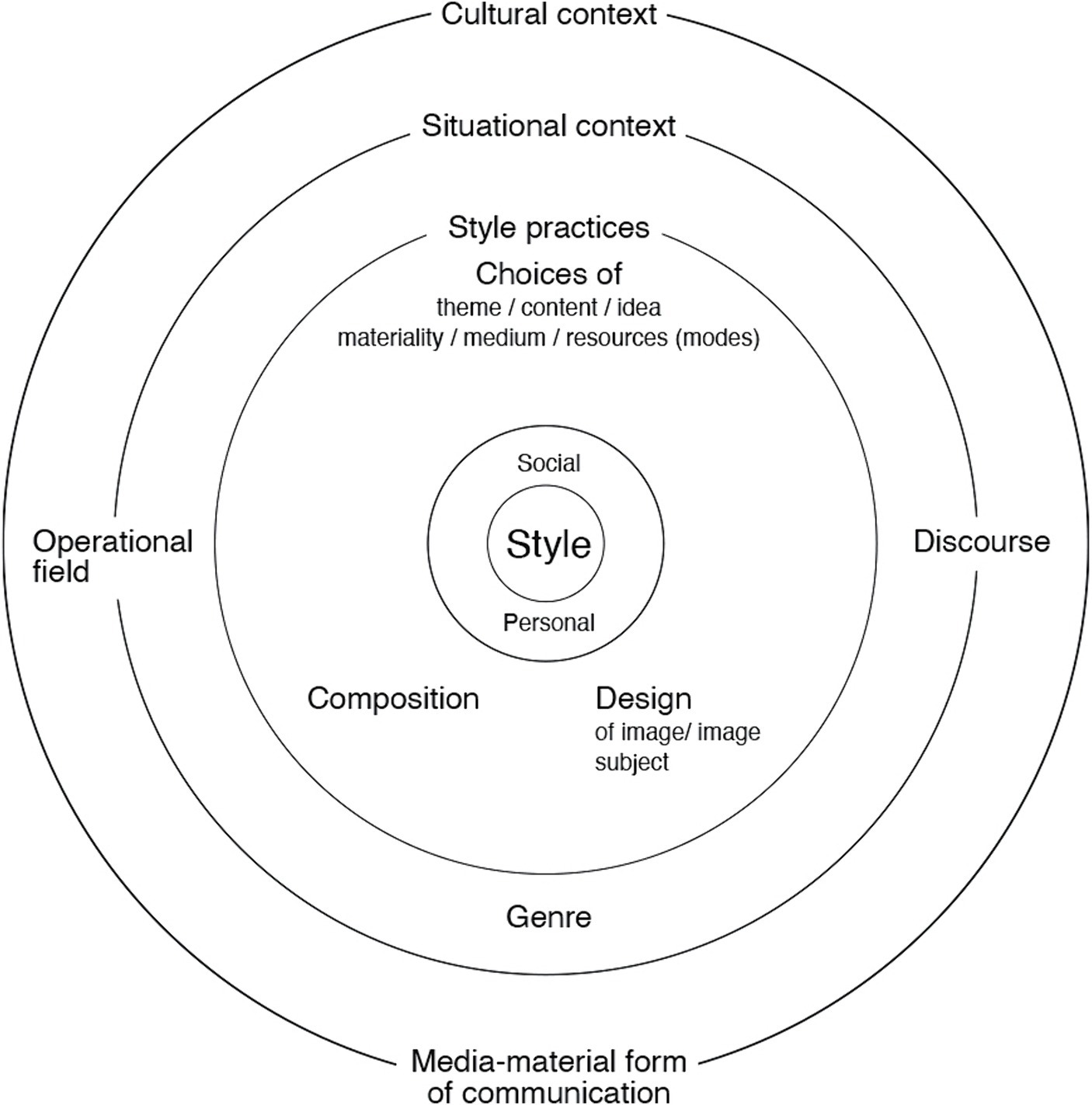

There are not so many descriptions concerning the concept of style in social semiotic research focused on visual communication. The one reason for this is, that social semiotics has concentrated more on the concepts of discourse and genre. The idea of style as an umbrella concept, including the genre and discourse, offers a holistic view of style as a semiotic resource with a symbolic power (van Leeuwen, 2005, 139). Of particular interest is Meier’s (2014) visual model, which, as it were, brings together all the processes and factors that influence the formation of a visual style (Figure 5). The visual style used in representation can be seen as a combination of resources (like colors, composition, materials used, and objects presented) in a certain field of operation (Meier, 2014, 22): for instance the science, marketing, or fine art. Thus, in the semiotic practice, the stylistic choices of made by the image maker are based on the discursive conventions of the context, function, and genre of the image (Meier, 2014, 21–27). As for the audience, the viewers make their interpretation of a picture on the grounds of similar presumptions.

Figure 5. Stefan Meier’s (2014) model of visual style. Translation and modification by the author.

The holistic view of style makes possible to see a style as the wholeness of a single representation. This is reasonable when thinking about multimodal representations, where all the semiotic resources interact in creating intertwined meanings (Siefkes and Arielli, 2018; 163, 28–29). Multimodal presentations often refer to a film or a comic book, for example, but even a single image is multimodal when combining resources such as materiality, technique, color and composition. In my own works, also a resource of language proved to be a way, that limits the sphere of interpretation of the whole. Perry Nodelman (1990, 37) characterizes style as the overall quality or atmosphere that is immediately interpreted by the viewers. We can also interpret some representations as historical or modern almost in the blink of an eye, as we experience some pictures as melancholic or joyful, in a visual minor or a visual major. Style as overall quality is clearly illustrated in the way the still life paintings of Dutch realism manifest their meaning as vanitases, representations of “nature morte.” A certain sense of melancholy can be immediately felt in them, even in the paintings without explicit symbols such as human skulls and hourglasses.

In the concrete process of the image making, which Meier (2014) calls a style practice, the designer or artist makes the choices of a theme, content, materials and technique. Then, by using resources of design and composition—the way, how something is depicted—the representation itself is concretized into an image, expressing the personal fingerprint of the image maker. In the context of my own works, the personal style become manifested especially in the way I use the technique of scanography in design. Concerning the connotative resource of style, it seems that the holistic idea of style as multimodal, and meanings as intertwined, is relevant. In my memories of my grandfather’s nature encyclopedias, the overall stylistic effect originates both by a text and images, probably including the whole media of the old book with its materials like leathered spin with golden titles and decorations and transparent tissue guards on the pages with pictures. This multisensory nature of experience of style is likely to create atmospheric connotations. For that reason, I did not want to present my works on screen, or on a synthetic, ‘plastic’ paper, but used the resources of materiality of ink and matte art paper as medium. Since the field of operation was the art world, it was natural to frame the images and add passepartout and name the works.

Style is described in terms of personal and social (Meier, 2014). As for the individual style, the personality and the temperament of an artist certainly affect the style of the image. Concerning my own personal style, it shows a persistent tendency to melancholy, a fascination to put things in minor. Perhaps that is why I am also inclined to find a response to the historical imagery that naturally carries with it the nostalgic melancholy of historical experience. After all, it is hard to imagine a personal style separated from the social process of creating representations. Representation is a process in which the way the sign-maker depicts an object is dependent on their psychological, cultural, and sociological background (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2021, 8). On this source of style, the fusion of the personal and cultural, I use the term mental-visual reserve (Raappana-Luiro, 2021, 110). This covers personal and cultural factors: one’s personal traits, experiences, memories, and esthetic taste affected by surrounding culture. In the case of this study, the style of my works is inspired by historical images: old still life paintings, and illustrations from natural encyclopedias and field guides. These stylistic similarities work as a connotative semiotic resource with a symbolic power. Concerning the social element of my mental-visual reserve, it is evident that people of a similar age, gender, and cultural background have shared experiences and memories that call forth some shared moods or mental images.

The concept of periodical style or a recognizable personal style of an artist contains the idea of repetition of certain visual features across several representations (Skaggs, 2017, 213). The semiotic power of this kind of style is strongly connected with conventions to use certain visual features. Our interpretation of the meanings conveyed by a visual style is based on where we saw a similar style earlier. According to van Leeuwen (2005, 274–276), cultural connotations arise when a sign is transferred from its original environment—time, culture, and social group—to another context. The sign in its new context is also associated with its earlier environment, thus, conveying to the zeitgeist of the past into the present (van Leeuwen, 2005). Periodical styles, isms, are not only a collection of design objects or pictures: they are always manifestations of the values and ideologies of society, of something ‘in the air’ in a certain historical era and place (see also van Leeuwen, 2005, 69). Via cultural connotations, I transferred the ideas of nature of the Dutch golden age and the Romantic era into today’s context, inspired by the visual style of nature imagery of those times. In the case of my works, the stylistic influences are not obvious, but more like intuitive impressions of the imagery from my memory. Nevertheless, the connotations carry with them a stupendous historical legacy of ideas.

In addition to cultural connotations, based on meaning aroused by the similarity to earlier presentations, there is another way, in which semiotic resources make meanings: experiential metaphors. They make use of more universal human experience (van Leeuwen, 2005; van Leeuwen, 2020): for example, we tend to interpret some colors as warm and some visual forms as heavy. In artistic practice, cultural connotations and experiential metaphors work together. In the case of my own works, the pictures make meaning through their cultural connotations with earlier visual styles used in representations of nature. Simultaneously, semiotic resources work metaphorically: for example, we interpret the black background of pictures as darkness, and because of being a diurnal species—and because colors have special potential for affective meanings—we view that blackness as mysterious and unknown (see Pastoureau, 2008; Raappana-Luiro, 2021, 127–128; Raappana-Luiro, 2022). At the same time, we may associate black with the cultural elements of death and mourning (Raappana-Luiro, 2021). Thus, many cultural conventions of meaning making are originally based on experiential metaphors. The little dead body of the bird in my picture would arouse quite different effect on a light (sky)blue background than on the black background.

In Meier’s (2014) model, the operational field of an image is connected to discourse. They, in turn, affect the choice of the genre of the images: we tend to associate certain types of content and stylistic features with a certain genre of the image. In the same way that I vacillated between the identities of an illustrator and artist, I also vacillated between genres: as works of art, my images approach popular illustrations. Admiration for the past natural history illustrations also brought connotations to the stylistic conventions of the genre. In this way, also the genre expectations can be mixed, connoting both with natural history (the style of images) and fine art (as the operational field).

4 Discussions with nature—mental-visual reserve

When you use your own works as research material, it is impossible not to reveal your own experiences and history. For this reason, I am starting with a story from my childhood: I am four or five years old, drifting in the forest and along the banks of the river near my family’s wilderness cottage, picking up the most colorful little river-ground stones and putting them in my pocket. I am an explorer on unknown ground, the first to see an emerald-glamoured damselfly over the stream. I also know that at some points in the forest, chickweed wintergreens get a delicate pink tinge in their leaves and flowers. Every little plant, insect and cone is a new miracle for me. I do not care about the mosquitos around me or the clothes that get wet when I immerse myself in a conversation with nature.

This memory is from early 1970s in Finnish Lapland. At home, in our tiny city apartment, there were some books inherited from my grandfather: old nature encyclopedias from the beginning of the 1900s and some field guides on birds and insects. There are still my pencil marks in the bird guide as I have tried to reproduce the pictures with the help of carbon paper. In the encyclopedia, there were reproductions of illustrations from earlier decades made by famous illustrators, including Ernst Haeckel’s magical works of bats and sea creatures. Magical were also the texts of these books: descriptions of gigantic whales and small deep-sea creatures shining like lamps offered an enchanting blend of scientific and esthetic pleasure. My affective, experiential relationship with nature was combined with the surrounding cultural discourse found in old natural history books, and I became a kind of esthetic hunter-gatherer, interested in both the esthetic and biological qualities of nature. As got a bit older I even made a small insect collection and set beautiful small stones, cones, and other pieces of nature on my shelf, intuitively making a kind of cabinet of curiosities. I learned to identify different animal and plant species, and when raising caterpillars, I began to understand that butterfly species needed a particular food plants. That way I learned experientially to understand the fragility of biodiversity. My relationship with nature has offered me both a scientific, esthetic, and emotional-affective experience, and has led to the creation of the works that serve as material for this article.

Although the artist in me led me to study literature and art history and finally to training as a graphic designer and illustrator, my relationship with nature has remained close. I am a volunteer species surveyor and still looking for the topics of my creative work in nature. As this study shows, my childhood experiences in nature, as well as the old nature imagery I encountered in my grandfather’s books, had a strong impact on my personal style of depicting nature. Later in my life, when studying art history, the style of still life paintings from the Dutch Golden Age also touched me deeply: I was aware of their role as vanitases even before it was told to me. What is essential, however, is that the process of drawing stylistic inspiration from the mental-visual reserve is anything but straightforward, but much more multilayered and filtered by personal traits, memories, and nostalgia. After all, the childhood experience of nature as a miracle has become a regular theme in my depictions of nature.

5 Stylistic influences in a new context: The end of the world-exhibition

Scanography as a technique has special semiotic potential. When I started—quite accidentally—to make tests with a flatbed scanner some years ago, the first thing I scanned was the wing feather of a whooper swan. In the past few years, I have been using a mixed technique of scanography, collage, and digital painting to make the fictive illustrations of scanned natural objects (Raappana-Luiro, 2021; Raappana-Luiro, 2022). What was astonishing in this technique, was the somehow unnatural precision of details also in the darkest parts of the picture (see also Buchmann, 2011). This is visually remarkably similar to the historical illustrations, where the technique of skilful hand painting offered the extreme ‘bokeh’ for objects. The dramatic lightning, where the light source is below the object, created an even illumination which was different from photographic images (Buchmann, 2011). Pretty soon I realized that by using a black background I could intensify the dramatic effect: the colors and the lightning looked more intensive, as if the objects were highlighted from the darkness surrounding them.

It is not surprising, that scanography as a technique is often used somewhere between art and science. In fact, many artists are using scanography especially in presenting objects of nature. An illustrative example of this “work in the middle ground” is the artist Joseph Sheer, who is described by Biologist Buchmann (2011) in an article in the journal Nature. The artist Sheer collected microlepidoptera for his scanography works because of their esthetic characteristics. At the same time, he developed his entomologist skills and even observed new species (Simpson and Barnes, 2008; Buchmann, 2011). The technique makes possible the accurate depiction of natural objects and at the same time offers a “more than real” look for the objects (see also Kress and van Leeuwen, 2021, 156–159). This kind of accuracy in terms of the details and shadows creates a sense of dreamlike stagnation (see also Nodelman, 1990, 117–118). In my three pictures, this stillness is heightened by placing the objects—an elk’s jawbone, a bird and a cone—in the center of square picture areas thus inducing the viewer to stop and contemplate. By following the convention of natural history illustration, where the objects are depicted on a plain background, separated from their natural surroundings, I came to a visual solution that created a miraculous aura for the natural objects. Like in their historical predecessors, they are not just objects, but objects of contemplation.

The atmosphere of the pictures which inspired me is then a result of the artist’s attitude to nature as a wonder, where all the specimens, large and small, are treasures worthy of admiration. The visual style of images which—despite of their seeming realism—express an atmosphere of some profound, magical meaning below the surface of their everydayness has a lot in common with the literary style in narrative fiction called magical realism (Bowers, 2004, 1–29; Vanhaelen, 2012, 1,009; Raappana-Luiro, 2021, 113). When considering the Dutch paintings of seventeenth-century, Angela Vanhaelen (2012, 1009) notes, that it “…suspends a shimmering moment in time, holding up the materiality of life itself for the viewer’s attentive contemplation.”

Working with scanography is a combination of digital and very material practices. In my case, it needs a lot of time roving in nature and exploring interesting things for material. After the scanning of the elements, there is a digital process of image making. My aim in digital manipulation was to further dispel the associations with photography and raise the effect of a hand painted picture. My works are usually made for print, which means that I need to think about the semiotic resources of the materiality of printing, too. In the case of The End of the World exhibition, I chose to use ink-jet printing. This technology offered a sense of deepness—the effect of objects emerging from the surrounding dark space—which was intensified further by the matte art paper I used. In this way, an atmosphere of dreamlike stillness and a temptation for an attentive and contemplative way of looking were emphasized by the chosen materials. To get even more space around the works I used passepartouts—one of the conventions of fine art. I chose to use slightly creamy white passepartouts, aiming to create an effect of yellowed patina—like in old natural history prints—to my works. All these material solutions descended from my sources of inspiration: a “more than real” atmosphere and the nostalgia of the historical experience.

The meanings I—mostly intuitively, partly intentionally—wanted to express in my three works in The End of the World -exhibition, were not of science but of esthetics and emotion. During my life, I have personally experienced the way the human society has changed the nature in my surroundings. There are fewer and fewer forests left around our ‘wilderness’ cottage. It is not so easy to catch a trout for a meal from the river and not so common to see the beautiful damselflies fluttering over the creek. Nature as a source of wonder as it was in my childhood memories is gradually disappearing. There is no doubt that the feeling of nostalgia and melancholy has contributed my choices of stylistic resources. In illustrating the phenomenon of modern nostalgia, Antto Vihma (2021) notes, too, that the pace of change in modern society is so fast, that today’s world seems to be foreign land for many of us. Stylistic connotations to past representations suit the ‘emigrant’s nostalgia’ in which we find a solace in our fragmentary memories (Boym, 2007; Vihma, 2021).

When turning toward history and memories, an artist always carries a melancholic undertone. Historical representations as such are experienced as a reminder of the “unattainability of all the world and of the past” (Ankersmit, 2005, 178; Raappana-Luiro, 2022). By using historical images as a form of stylistic inspiration, I inevitably conveyed a sense of melancholy in my artistic works. This melancholy of historical experience is made even more intensive by the stylistic references to vanitases of the Dutch Golden Age with their dark backgrounds and dramatic lightning.

Before the invention of photography, the illustrators of natural history, striving for realistic depictions of specimens for classification, used collected, dead animals as their models. When writing this essay, I found an image of a painting made by the well-known Finnish nature artist Wilhelm von Wright (Figure 6). The still life, made in the first half of 19th century, depicts a small bird, a linnet. It was probably killed by the painter, and hung on the wall, tied by its leg. Von Wright’s painting has an amazing likeness to my picture titled Exitus (Spinus spinus) (Figure 2). However, the story behind Exitus is different. I found the bird, a siskin, in my backyard. It had flown into the window and died. I constructed a net of beard moss and placed the tiny, still warm, dead body onto the scanner glass. The moment was almost spiritual, and for me, the death of the bird grew to represent universal suffering and mourning.

Figure 6. Wilhelm von Wright. Hemppo. 1830–1839. Gouache on paper. Finnish National Gallery (©https://www.kansallisgalleria.fi/fi/object/480986).

As for the other two works, Ark and Seed (Figures 1, 3), their meanings are more ambivalent. As a triptych, the meanings of all three pictures are formed by their mutual relation. My ‘cabinet of curiosities’ comprises quite common species: an ordinary little bird, an elk’s jawbone and a cone of a Swiss pine from the city park. The elk’s jawbone in Ark I was picked up from a little sandbar in the middle of a river in the Oulanka national park in North Eastern Lapland. I made an experiment and put a small piece of moss on the bone before scanning. There were some bilberry twigs growing through the moss, and after the scanning process, I realized the contrast between dead and living nature. In my imagination, the jawbone became a surrealistic ship, carrying life within. In a similar way, the ordinary cone in Seed took on a miraculous value as a source of new life. Finally, to limit the sphere of interpretation, I named the pictures Exitus (Spinus spinus), Ark and Seed. The word ‘exitus’ is commonly used of the moment of human death. In the context of an animal, the name gives rise to anthropomorphism, representing the death of the bird and human as equal. By adding the scientific name of the bird to the title of the picture I intentionally mixed the contexts: the genres of specimen illustration and a work of fine art. The use of scientific names works as a metonymy of the whole species, expanding to represent all the living creatures that are at risk of extinction. As a whole, the series of images could be represented as neutralized taxonomic illustrations, but intertwined with a semiotic resource of language—the titles of the works—their meanings are focused on mourning for the loss of nature. My aim in this mixing of genre expectations was to hint for the scientific relation to nature.

By connoting the works to the cultural history of representations of nature as a miracle—past cabinets of curiosities, natural history illustrations and still lifes—my works convey an atmosphere of nostalgia and melancholy. In the new context the stylistic choices, without question, are related to my personal nostalgic memories, but possibly also to some shared nostalgia in a world that changes too fast around us. In a world, where all the everyday miracles of nature are going to be rarer, day by day.

6 Conclusion

In this essay, I have reflected on the stylistic choices in the practice of semiotic meaning making. In my works, the cultural connotations to past representations of nature are made use of to create an atmosphere of seeing nature as a wonder, combined with the nostalgia and melancholy of historical experience. The melancholic atmosphere is developed further by connoting the work to the stylistic conventions of vanitases. Even though the works I have focused on are exhibited in the context of the art world, my personal interests are in popular imagery. This interest is echoed also in the representations that have inspired me: cabinets of curiosities, still lifes, and past natural history illustrations all have a kind of popular origin in the field of art and natural sciences. Still life pictures were hung on the walls of bourgeois homes, while cabinets of curiosities were collected by passionate enthusiasts and later used as part of exhibitions in popular museums. The work of early natural history taxonomists was continued among enthusiasts willing to observe the different specimens of animals and plants.

All of the aforementioned genres of representation of nature use the convention of realistic depiction, which has its roots in Renaissance’s ideal of the immediate observation of nature. However, the styles of representation were developed in close interaction with other images. As Brian Ogilvie (2006, 141) notes, “[t]he sixteenth-century naturalist was constantly in motion— motion between the library, the cabinet, the salon (or dinner table and printers’ shop), the garden, the wharf, and the countryside—.” According to Kress and van Leeuwen (2021,154) we still judge the realism of images on the basis of the old technology of 35 mm photography. In my works, there are some elements which are ‘more than real’: especially the extreme precision and detail and the manipulation of the size of the objects. One element that make the images look ‘less than real’ is the elimination of the background, an early formed convention in natural history illustration.

In the works in The End of the World -exhibition, the elimination of the background was used to emphasize attentive viewing. Via the effect of stillness, which is characteristic to the precision of depiction, the images create a way of looking that is simultaneously attentive and contemplative (Vanhaelen, 2012). It seems, that a similar way of looking is typical for nature enthusiasts, too. Thomas Fleischner argues that the field experience of a naturalist is based on a special state of mind and a special kind of looking, where “a seamless merging of attentiveness outward and inward, toward the interwoven realms of nature and psyche” takes place (Fleischner 2011, 7). As for the concept of biophilia (Wilson, 1984), it deals with our innate tendency to focus on the living nature surrounding us. The attitude of an explorer, searching for novelty and diversity in nature, is typical for biophilia. According to Edward O. Wilson (1984, 1), biophilia is also the key to understanding the value of nature and protecting it. Fleiscner’s and Wilson’s writings put into words my own experiences underlying the works analyzed in this study.

Today – as opposed to my historical sources of inspiration – the discourses of natural science seem to differentiate from discourses of art. My personal relationship with nature has been biophilic and, by implication, colored by empathy toward all living creatures. This empathy is more by concretely living with nature than from pictures of it, so I am a bit skeptical about the power of images as such to create biophilia. According to Whitley et al. (2021), the anthropomorphism of nonhuman animals in portraits of endangered species evoked greater empathy among the survey participants than a traditional wildlife photographs of a species. As for my own works, I hung Exitus (Spinus spinus) in the middle of the series of the three because of my emotional identification with the bird. Compared to it, the two other works seem more conceptual. Undoubtedly, in the purpose of popularizing the nature discourse, these kinds of animal portraitures are more effective at creating empathy and a conservative attitude toward nature than, say, visualized statistics of the extinction of species.

From the perspective of post-colonialist and posthumanist thinking, my sources of inspiration could be seen as questionable. Past depictions of nature date back to the time of the expeditions to new colonies and taxidermies of exotic specimens. Nevertheless, without the history of classifying, describing, and collecting we were unaware of biodiversity—with whom we live on this planet and who we have to protect from extinction (Flannery, 2023, 7). I hope that the cultural connotations I have created by using historical images as a stylistic resource are those of wondering, contemplating, and experiencing the miracle of nature.

Author contributions

LR-L: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1440368/full#supplementary-material

References

Aiello, G., and Van Leeuwen, T. (2023). Michel Pastoureau and the history of visual communication. Vis. Commun. 22, 27–45. doi: 10.1177/14703572221126517

Ankersmit, F. R. (2005). Sublime historical experience. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bauman, W. (2018). “Wonder and Ernst Haeckel’s aesthetics of nature” in Arts, religion, and the environment: Exploring Nature's texture. eds. S. Bergmann and F. J. Clingerman (Boston: BRILL), 61–83.

Boym, S. (2007). “Nostalgia and Its Discontents.” The Hedgehog Review. Critical Reflections on Contemporary Culture (Summer). Available at: https://hedgehogreview.com/

Buchmann, S. L. (2011). Moths on the flatbed scanner: the art of Joseph Scheer. Insects 2, 564–583. doi: 10.3390/insects2040564

Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. 1st Edn. London: Murray.

Flannery, M. C. (2023). The road to herbaria: teaching and learning about biology, aesthetics, and the history of botany. J. Biosci. 48:58. doi: 10.1007/s12038-023-00401-y

Fleischner, T. L. (ed.) (2011) “The mindfulness of natural history.” in The way of natural history. (San Antonio: Trinity University Press), 3–15.

Geczy, A. (2019). “Curating curiosity: imperialism, materialism, humanism, and the Wunderkammer” in A companion to curation. eds. B. Buckley and J. Conomos (Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated), 23–42.

Haeckel, E. (1904). Kunstformen der Natur. Leipzig: Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, 1899–1904.

Halpern, M. K., and Rogers, H. S. (2013). Inseparable impulses: the science and aesthetics of Ernst Haeckel and Charley Harper. Leonardo (Oxford) 46, 465–470. doi: 10.1162/LEON_a_00642

Honig, E. A. (1998). Making sense of things: on the motives of Dutch still life. RES Anthropol. Aesthetics 34, 166–183.

Jovanovic-Kruspel, S. (2019). ‘Visual histories’ science visualization in nineteenth-century natural history museums. Museum Soc. 17, 404–421. doi: 10.29311/mas.v17i3.3234

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2021). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: University College London.

Meier, S. (2014). Visuelle Stile: Zur Sozialsemiotik visueller Medienkultur und konvergenter Design-Praxis. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Neri, J. (2011). The insect and the image: Visualizing nature in early modern Europe, 1500–1700. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Nodelman, P. (1990). Words about pictures: Narrative art of Children's picture books. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Ogilvie, B. W. (2006). The science of describing: Natural history in renaissance Europe. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Olalquiaga, C. (1988). The artificial kingdom: A Treasury of the kitsch experience. New York: Pantheon Books.

Raappana-Luiro, L. (2021). Kuvan Henki: Fiktiivisen Kuvan Visuaalinen Tyyli Multimodaalisuuden Kehyksessä. DA diss. Rovaniemi: University of Lapland.

Raappana-Luiro, L. (2022). Happy hearts do not hang down: the design process for the 2018 Valentine’s day postage stamps of Finland. Visual Commun. 21, 507–517. doi: 10.1177/1470357220917435

Richards, R. J. (2002). The romantic conception of life: Science and philosophy in the age of Goethe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Siefkes, M., and Arielli, E. (2018). The aesthetics and multimodality of style: Experimental research on the edge of theory. Berlin: Peter Lang.

Simpson, N., and Barnes, P. G. (2008). Photography and contemporary botanical illustration. Curtis's Botanical Magazine 25, 258–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8748.2008.00628.x

Stein, C. (2021). Medieval Naturalia: identification, iconography, and iconology of natural objects in the late middle ages. Medievalista 29, 211–241. doi: 10.4000/medievalista.3902

van Leeuwen, T. (2020). “Multimodality and multimodal research” in SAGE handbook of visual research methods. ed. L. P. D. Mannay (London: SAGE Publications, Limited), 465–483.

Vanhaelen, A. (2012). Boredom's threshold: Dutch realism. Art History 35, 1004–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8365.2012.00934.x

Whitley, C. T., Kalof, L., and Flach, T. (2021). Using animal portraiture to activate emotional affect. Environ. Behav. 53, 837–863. doi: 10.1177/0013916520928429

Keywords: cultural connotation, illustration, personal style, visual style, stylistic conventions, social semiotics, nature, natural history

Citation: Raappana-Luiro L (2024) Miracle of nature—dialog with nature through artistic creation. Front. Commun. 9:1440368. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1440368

Edited by:

Melanie Sarantou, Kyushu University, JapanReviewed by:

Marija Griniuk, Sami Center for Contemporary Art, NorwayAndrea Karpati, Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary

Copyright © 2024 Raappana-Luiro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leena Raappana-Luiro, bHJhYXBwYW5AdWxhcGxhbmQuZmk=

Leena Raappana-Luiro

Leena Raappana-Luiro