- School of Foreign Languages, Guangzhou City University of Technology, Guangzhou, China

Among all the English translations of Liaozhai Zhiyi, Giles’ and Minford’s translations received the most reviews from Western readers. Their translations are rich in peritexts, which make up a large proportion of the two translations. Based on Genette’s Paratexts theory and Batchelor’s latest research in this field, this article examines the two translations’ peritext strategy, main functions, and efficacy in the reception of Liaozhai Zhiyi with a view to seeing the roles that two types of peritexts play in the dissemination and reception of the book in English world. Looking closer to the two translations’ peritext strategies, including covers, acknowledgments, prefaces, introductions, notes, illustrations, and appendices, the author summarizes five main functions of the peritexts: to reveal to some extent the translator’s translating aims, to show the commissioner’s peritext strategies, to spread Chinese culture, and to consciously or unconsciously manifest socio-cultural context. In addition, the article, through contrastively analyzing readers’ reviews of two translations’ peritexts, concludes that the efficacy of the peritexts in Minford’s translation is much better than that in Giles’ translation, which means that the former may, to a large degree, help promote the reception of Liaozhai Zhiyi, while the latter may not. It is also anticipated that the research pattern can be used in the study of the roles peritexts and epitexts play in the reception of a wider genre of Chinese works so as to facilitate the going-global of Chinese works and culture.

1 Introduction

“Paratexts,” proposed by Gérard Genette in the late 1980s, include all verbal and non-verbal materials acting as an agent between the reader and the text. Paratextual elements, if they are made up of information that has taken the form of material, are bound to have a location that can be placed in relation to the location of the text itself: surrounding the text and either within the same book or at a more respectful distance. In the same book, such materials as the title or the preface and sometimes materials embedded into the cracks of the text, such as section titles or specific notes, can be regarded as paratexts (Genette, 1992). Genette (1992) gave the name “peritext” to this first spatial category and discussed it in the Introduction to Paratext. The distanced materials are all those information that, at least primarily, are situated outside the book, commonly with the aid of the media or secretly in private communications. This second category was named “epitext” by Genette. According to Genette, peritext is often within the same book and will leave a great impact on readers, whereas epitext is distanced materials and has little impact on readers. Taking Minford’s and Giles’ English translations of Laizohai Zhiyi, a Chinese classic, as an example, the author finds that many readers on Goodreads or Amazon express their love or hate for certain peritexts like introduction, notes, illustrations, and formatting surrounding the two translations, whereas a few readers state that their reading is influenced by epitexts such as publishing houses and online reviews situated outside the two translations. Given that peritetxs play an important role in readers’ reception of translated books, this article will examine the peritexts of the different translations of the same book and their influence on targeted readers.

As one of the best collections of short stories in classical Chinese, Liaohzhai Zhiyi is famous for its strangeness and strange stories written by the Chinese novelist Pu Songling in the late seventeenth century, whose artistic originality made the novel stand out and raised the quality of ancient Chinese literary fiction. There are about 500 stories in the book, consisting of three genres: love stories, stories that attack the imperial examination system, and stories that expose the brutality of the ruling class. Ma (2022), a famous expert on Liaozhai Zhiyi, once pointed out that “Among the classics of Chinese literature, Liaozhai Zhiyi has been translated into the most foreign languages.” Since the Japanese translation in 1784, there have been more than 20 translations in different languages by the end of the twentieth century. Among them, English translations not only make up the largest percentage but also have a profound impact on readers (Sun, 2016). For recent professional readers, Dodd (2013) examination of the monster in this book as a ‘cultural body’ will add to the understanding of Liaozhai within the context of early Qing society and culture. Smith (2019) argues that Pu Songling effectively communicates the notions of beauty and love and especially creates a more complex and nuanced characterization of a beautiful woman using auditory sensory imagery. Tso (2017) compares the source and target texts, revealing that in many of Pu Songling’s stories, spirit-free love and sexual pleasure are celebrated.

For average readers, On Amazon, the largest e-commerce platform in the United States, and Goodreads, a book review website, there are 12 English translations of Liaozhai Zhiyi. Herbert Allen Giles’ version and John Minford’s version are reviewed by 34 and 189 readers, respectively, with a total of 5,396 and 19,160 English words, far more than the other translations’ reviews in total. Giles (1845–1935) was an English scholar of Chinese language and culture who helped to popularize the Wade-Giles system for the romanization of the Chinese languages. His translation, the first abridged translation of Liaozhai Zhiyi in English world, was published by Thos. De la Rue in London in 1880. The translation was reprinted many times, and the latest version was published by Tuttle Publishing House in 2010. Minford (1946–) is a sinologist and literary translator. He is primarily known for his translations of Chinese classics such as The Story of the Stone (《红楼梦》) and The Art of War (《孙子兵法》). He went on to translate for Penguin a selection from Pu Songling’s Strange Tales (《聊斋志异》) in 1999. In 2006, his translation, titled “Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio,” was published by Penguin Books. Minford once said in the introduction of his translation that he appreciated the translation of Giles’, but after careful study, he believed that Giles’ translation was full of the bond of the Victorian era, especially Giles’ adaptation of erotic description in the original text. He decided to translate these erotic descriptions the way they are presented.

In addition, Minford’s and Giles’ versions are rich in types of peritexts among all translations. So far, no researchers have explored the relationship between the peritexts within these two translations and their influence on readers. This article considers it a necessary and worthwhile task to do. Through close reading and comparative study of the peritexts in the two versions, this research will strive to reveal the strategies and main functions of the peritexts in the two versions. What is more, by analyzing the readers’ online reviews that are highly related to the peritexts, this article will also uncover the efficacy of the peritexts in the two translations.

2 Literature review

Since the introduction of paratexts by Genette, some scholars have studied the concept; some examine the paratexts in specific texts through their lens. Kathryn Batchelor, in her book Translation and Paratext, first introduced Genette’s notion of paratexts and its evolution across disciplines, especially in translation studies, digital, media, and communication studies. Afterwards, she discussed authorized translations and paratextual relevance, Chinese paratexts of Western translation theory texts, and Walter Presents and its paratexts in accordance with some specific cases. In the last part of her book, she focused on terminology, typologies, research topics, and methodologies in translation and paratexts. Batchelor has, in her book, expounded on research about translation and paratexts by scholars worldwide since 2017. The following part will be the main research in this field conducted by Chinese scholars after 2016.

Geng (2016) presented a summary of how paratext evolves in translation and translation studies and proposed two kinds of paratext studies in translation, which are implicit and explicit, respectively. To make this field of study move forward, he argued that scholars should make more attempts at consolidating theoretical research related to paratext in translation, expanding to include extra-linguistic paratext in literary and non-literary texts by using various methods, and looking into to what degree paratext can be customized to advance the going-out of Chinese literature. Yin and Liu (2017) made a scientometric analysis of the research phases, trends, and focuses of paratextual studies by using the CiteSpace system, based on the data of the research papers published between 1986 and 2016, which were retrieved from the CNKI database. They found that the studies extend from literary field to linguistic field and then to the translation field. But as far as the research approach is concerned, speculative research is much more apparent than empirical research. Afterwards, Xin and Tang (2019), Li and Zhu (2021), and Shao and Zhou (2022) analyzed the translator’s subjectivity and translating strategy through the lens of paratexts. Just a few Chinese researchers delve into the strategy and function of paratexts. Shi and Zhou (2020) and Wang and Wei (2022) take the single English version of 《老残游记》(The Travels of Lao Ts’an) and 《聊斋志异》(Liaozhai Zhiyi) as an example to discuss the form and function of the peritexts.

According to Aiello (2013), readers should be attached to the greatest importance in literary research, and their role in the reception of literary works is indisputable. Therefore, this research holds that in order to understand the efficacy of a translation’s peritexts in the context of the target language, it is essential to look into the reaction of real readers toward these peritexts. Furthermore, the article suggests that only by comparing the target language readers’ comments on different translations’ peritexts of the same source language work can researchers more clearly highlight the efficacy of these peritexts in the target language context. Based on the above-mentioned assumption, this article takes the peritexts in Minford’s and Giles’ versions of Liaozhai Zhiyi as the research object and tries to answer the following three questions: (Genette, 1992) What are the peritext strategies of the two translations? (Ma, 2022) What are the main functions of these peritexts? (Sun, 2016) How is the efficacy of the peritexts in two translations?

3 Peritext strategies in two translations

3.1 Cover

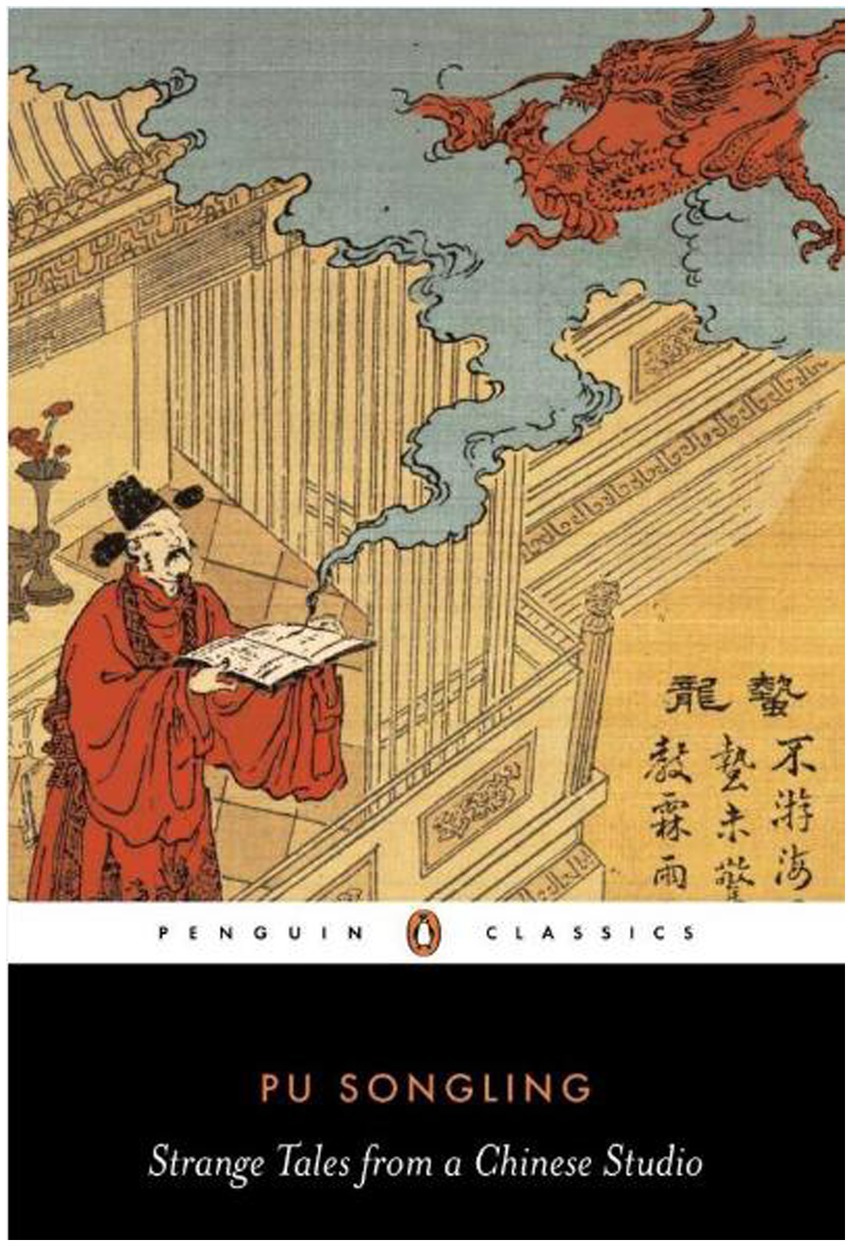

The front cover of Giles’ translation (see Figure 1) is red and dominated by yellow flower-like motifs and a dragon image. On the front cover are the title of the book and the name and title of the translator. The front cover of Minford’s translation (see Figure 2) can be divided into three parts: the top half is yellow, with graphic elements including classical Chinese architecture, traditional Chinese characters, brush strokes, images of ancient Chinese officials, and an eagle catching a bat; the middle is white, with black words indicating that the book is part of the Penguin Classics series; and the bottom half is black, with orange words showing the author’s name and white words revealing the title of the translation.

Figure 2. The front cover of Minford’s version. Reprinted with permission from Penguin Random House.

3.2 Introduction to the author/translator

Both Pu’s and Giles’ biographies are placed in the “introduction” of the Giles’ version (see also Section 2.4). Minford presented the reader first with basic information about Pu Songling and Liaozhai Zhiyi on the fly page of his translation, then introduced his own study experience, translation works, and position to readers. Therefore, readers first introduced to the book will learn about the author and translator and decide whether they are interested in it or not. The introduction of Pu and the source text is put before that of Minford, revealing that the source text is given priority. In addition, Minford’s translation elaborated on the background of the author, including Pu’s family background, academic career, and the writing process of Liaozhai Zhiyi. Minford highly praised Pu’s talent and believed that though confined to the imperial examinations all his life, Pu was able to devote himself to writing, which eventually made Liaozhai Zhiyi the pinnacle of classical Chinese short stories.

3.3 Acknowledgments and preface

Giles’ translation contains no “Acknowledgments.” He translated the “Preface” by Tang Menglai (Qing dynasty) into English and put it in the “Introduction.” Minford spent about 14 years in completing his translation, and this reputable translation can hardly come out without generous external help like the financial support from the Taiwan Cultural Construction and Development Commission, the source text borrowed from friends, and the commitment of Penguin Press. In the “Acknowledgments,” great thanks have been extended to the people and organizations that used to assist Minford in translating the book. What needs to be noticed is that the “Preface” written by Minford is placed in the “Appendix.” The “Preface” consists largely of the translator’s notes and breaks down into two sections. The first one indicates that Liaozhizhiyi is characterized by plenty of incomprehensible allusions. In particular, the Chinese version of Zhu Qikai is exemplified by up to five pages of notes on one page of the original text. In order to make his notes reliable, Minford’s translation also refers to the notes of previous Chinese and English versions. The second section involves the translation of the Author’s (Pu’s) Own Record.

3.4 Introduction

The “Introduction” in Giles’ translation is more than 4,000 words and contains an introduction to the translator, the Author’s own Record, and Tang Menglai’s Preface. In the introduction to the translator, Giles started by describing how he became involved with the translation of Liaozhai Zhiyi. Following this, he tried to convince his readers that he was a qualified translator because he was at home in Chinese and English languages and cultures. Then he started his translation aim. Next, Giles briefly presented the literary status of Liaozhai Zhiyi in China and its author, Pu Songling. He also translated the Author’s Own Record, through which he hoped readers would learn about the profound meaning of Liaozhai Zhiyi and appreciate Pu’s impressive writing style. Finally, Giles translated the “Preface” written by Tang Menglai in the Qing dynasty.

The “Introduction” in Minford’s translation is about 7,000 words, including Pu’s life; two literary traditions of Chinese storytelling, two totally different genres, that of the zhiguai, which can be probably named the Weird Account, and that of the chuanqi, the Strange Story; a Chinese storyteller’s studio: sources and allusion, humor and depression; the erotic; fox spirits; ghosts and the supernatural; how to interpret Strange Tales; note about the text, translation, and woodcut; note about names and pronunciation. By contrast, Minford’s “Introduction” to Liaozhai Zhiyi is more comprehensive and systematic. Particularly, the detailed explanation and supplement to the fox spirits, ghosts, and the erotic can help readers better understand Pu’s writing themes and the cultural elements in his work.

3.5 Notes

Giles paid much attention to notes. There are 61 footnotes for “Introduction” and 731 footnotes for translation, which amounts to more than 31,000 words. In terms of word count, the longest note is in the story of “《何仙》” (Planchette), up to 415 words; in terms of notes quantity, “《罗刹海市》” (The Loch’a Country and the Sea-market) is equipped with up to 16 notes. The content of the notes is all-encompassing, including Chinese festivals and solar terms, explanations of historic figures, utensils and other daily necessities, weights and measures, system etiquette, customs and manners, Chinese personalities and beliefs, and social life.

There are 150 pages of notes in Minford’s translation, for a total of more than 37,000 words. The difference between the notes in the two translations is that Giles explained the difficulties in the translation to readers through lots of footnotes, while Minford explained the characters, geography, customs, culture, and other related information of each story in the appendix. Minford put some highly frequent culture-loaded words or proper nouns, for example, “桃木剑” (The sword as one of the dominating weapons employed by Taoist sorcerers) and “金丹” (golden elixir with magic power), into the “Glossary” and explained them in detail.

3.6 Illustration

As for illustration, Giles’ Translation has none, while a total of 98 illustrations are in Minford’s translation. Minford (2006) wrote in the “Introduction”: “the amazing illustrations come from the late-nineteenth-century Xianġzhu Liaozhai zhiyi tuyong, first printed in Shanghai in 1886. Despite coming over 170 years after Pu Songling’s death, these illustrations remain a well-known example of Late Imperial book illustration. The most important scholar and writer of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) fiction and bibliography, Qian Xingcun (Ah Ying), depicted them as the most prominent Strange Tales illustrations. They serve the need to visualize the environment and are particularly well observed regarding details of interior decoration, furniture, garments, architectural design, and courtyard planning. Because these illustrations were used for a version in 16 chapters, which was short of several items in Pu Songling’s primary collection, there are a few stories with no illustrations.”

3.7 Appendices

Appendix A in Giles’ translation mainly introduces the Ten Courts of Justice in the Yuli chao zhuan. A close reading of that can let readers have a basic grasp of the religious background of some stories and help them understand the description of “reincarnation, ghosts and spirits” in Liaozhai Zhiyi. Appendix B expounds on 11 proper nouns in the book Primitive Culture by Edward Tylor and in the article The Origin of Animal Worship by Herbert Spencer, which makes it easier for readers to have a deeper understanding of the proper nouns in the translation. In addition to the author’s preface, the appendix in Minford’s version first includes an unofficial terminology list, which was offered to help readers know more background about a small amount of the terminologies that recur in the Strange Tales. Moreover, the appendix also contains a finding list, maps, and further reading in Chinese and Western languages.

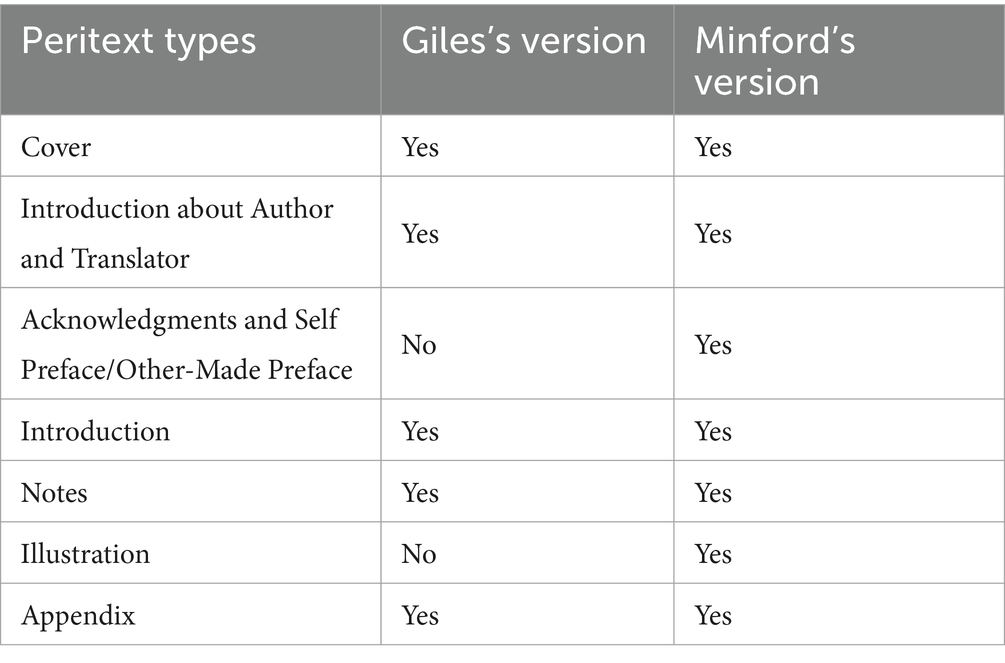

In terms of peritext types, both translators supplement their translated texts by giving more than five (including five) types of peritexts. In order to help readers’ understanding of the whole translated texts, Minford’s translation uses seven types of peritexts, in which acknowledgments, self-preface/other-made preface, and illustrations are not in Giles’ translation. As far as the peritext content is concerned, Minford’s peritext content is more comprehensive and accurate than that of Gile’s.

4 Function of the Peritexts

4.1 Revealing translation aim

The aim of any translational action, and the mode in which it is to be realized, are negotiated with the client who commissions the action. A precise specification of aim and mode is essential for the translator (Vermeer, 1989). Paratexts can make known an intention or an interpretation by the author and/or the publisher; this is the chief function of most prefaces and also of the genre indications on some covers or title pages.

According to the “Introduction” in Giles’ version, in the early time of 1877, while he was acting as Vice-Consul at Canton, he began translating the works (including Liaozhai Zhiyi) offered to English readers. It is implied that there is indeed a client who commissioned the action but did not make a specific request for translation, the peritexts; therefore, show Giles’ translation aim. Vermeer (1990) pointed out that people are able to discern three possible purposes in the translation field: the overall purpose aimed at by the translator in the translation process (maybe “make a living”), the communicative purpose aimed at by the target text in the target culture (maybe “enlighten the reader’), and the purpose aimed at by a special translation strategy or procedure (for instance, ‘to translate literally so as to display the structural characteristics of the source language’). Giles wrote in the “Introduction” that undoubtedly, Chinese culture is mocked at and hated again and again, only because the agent by whom the culture has been disseminated has developed a distorted and fake image. What the Chinese really practice and believe in their life will be recorded in the book.” Giles’ peritexts explicitly tell readers his translation aim—to question and criticize part of the media spreading Chinese culture and present a more real Chinese image to Westerners with detailed notes and stimulating translation. This exactly fits into the second purpose mentioned above.

Minford mentioned in the “Acknowledgments” that his translation was edited by Caroline Pretty and was selected for the Classics series at Penguin. It can be inferred that Penguin is the client whose translation aim, to some extent, is Minford’s aim. Penguin’s efforts in exploring the universality and local characteristics of Chinese literature should be valued because they may foster in Western readers an appreciation for the depth and diversity of Chinese literary works and make it easier for more Chinese books to enter into the global book market in the future (Qian, 2017). In addition, Giles’s version definitely exposes the limitations of the taste of his age; Minford points out these defects and gives readers a chance to taste Liaozhai Zhiyi precisely.

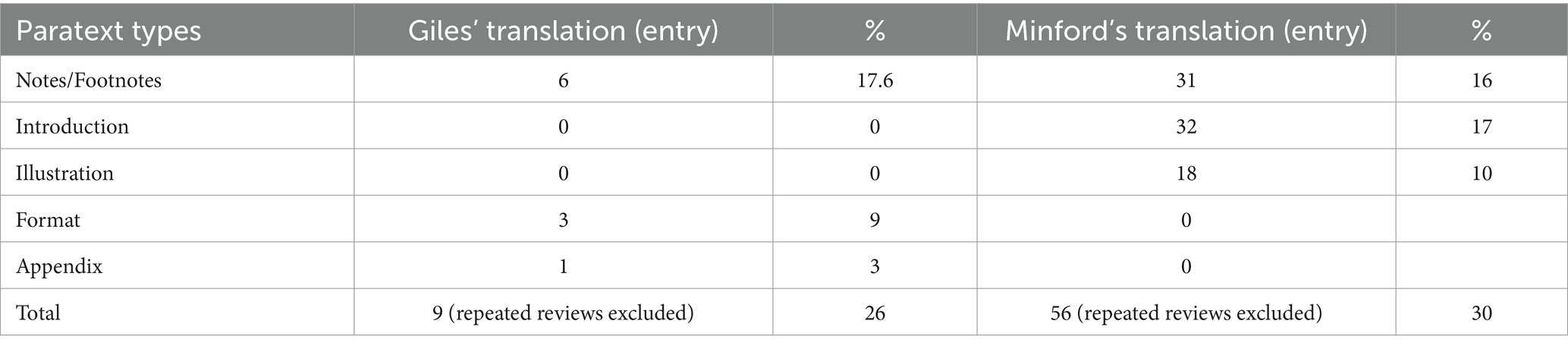

4.2 Showing peritext strategy

Giles’ translation was published by Thomas de la Rue & Co. in London in 1880. Historic China and Other Sketches, written by Giles, was also published by the same company in 1882. In contrast, the peritexts in the two books vary greatly. A conclusion may be drawn that the publishing house exerted no influence on Giles’s peritext strategy. A close reading of Minford’s work shows that his peritext strategy strictly abides by the Penguin norm. Apart from prefaces, introductions, and afterwards, Penguin Classics translations are characterized by the massive use of notes and appendices, which offer a wide range of information by providing chronology, maps, tables of weights and measures, further reading lists, glossaries of personal and place names, Chinese names and pronunciation, discussions of the works’ themes, key terms, basic concepts, and so on. By comparison, it is obvious that Minford’s translation has more diverse peritexts. The two translators’ peritext strategies are shown in Table 1.

4.3 Disseminating Chinese culture

The notion of culture as a sum of knowledge, proficiency, and perception is fundamental in our approach to translation. If language is an essential part of culture, the translator requires not only conservancy in two languages; he/she has to be adept at two cultures, too. To put it another way, he/she is sure to be a bilingual and bicultural individual (Vermeer, 1986). Giles started the study of Chinese at Her Britannic Majesty’s diplomatic mission, Peking, in a delegation from the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in 1867. In the beginning of 1877, while working as Vice-Consul at Canton, he set out to do the translation of the literature provided for the English readers. With regard to the task, he held the view that he owned two critical qualifications: one was accurate and comprehensive knowledge of English. The other is the deep and broad understanding of Chinese and the culture of this civilization. After his return to Britain, Giles lived in Aberdeen, Scotland. In 1897, he was appointed professor of Chinese at the University of Cambridge, following Sir Thomas Francis Wade; Giles remained in the chair until 1932. In his lifetime, he published a great number of books about Chinese and Chinese culture, which were prevalent during the latter half of the twentieth century, including Chinese Without a Teacher, Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, and so on. Giles had a deep study of classical Chinese and classical Chinese literature and had an insight into Chinese literature. Giles was definitely a bilingual and bicultural translator.

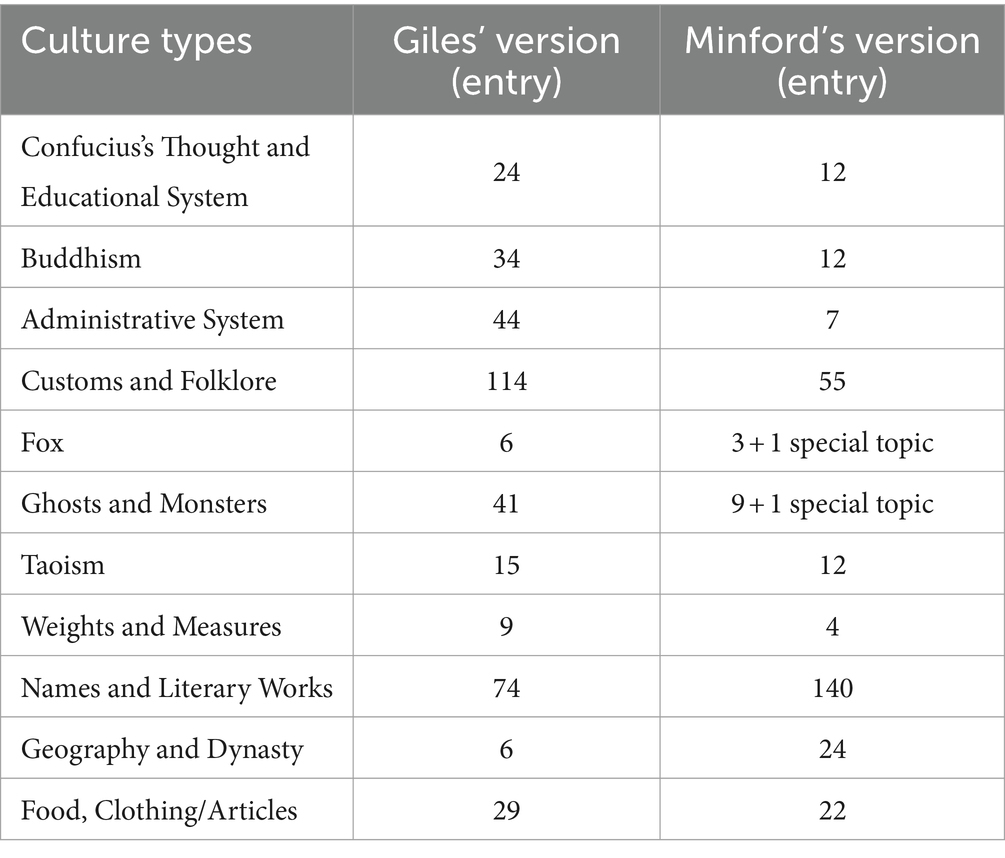

Minford is a productive literary translator, especially translating Chinese literary works into English. He earns his reputation for translating Chinese classics like Sunzi Bingfa (The Art of War) and Hongloumeng (The Story of the Stone). Minford studied at Winchester College and Balliol College, Oxford, where he graduated in Chinese studies in 1968. After graduation, he cooperated with David Hawkes on the Penguin Classics version of the eighteenth-century novel Hongloumeng for over 15 years. He was responsible for translating the last 40 chapters of the novel. In 1977, he traveled to Australia and strived for PhD degree under the guidance of Liu Ts’unyan. At the same time, Minford kept translating for Penguin part of Pu Songling’s collected short stories, Liaozhai Zhiyi and Sunzi’s Sunzi Bingfa. From 2006 to 2016, he acted as a Professor of Chinese at the School of Culture, History and Language at the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, where, after his retirement, he is now an Emeritus Professor. Minford’s professional knowledge and extensive translations make him a true China hand. The two translators’ introduction of Chinese culture in peritexts is shown in Table 2.

The author read carefully all the notes and annotations in two translations, classified them into 11 categories, and counted up the number of notes and annotations each category included. As is shown in Table 2, so much Chinese culture are translated into English world, with customs, folklore, names, and literary works making the largest proportion. Liaozhai Zhiyi is filled with various Chinese culture that are completely different from Western culture. Some simple stories often imply a deep meaning, which possibly makes it hard for Westerners to understand (Zhang and Wang, 2016). The two translators’ notes and annotations about Chinese culture will, to some extent, help readers to understand what these stories really mean, appreciate Chinese culture, and disseminate Chinese culture.

4.4 Unfolding socio-cultural contexts of translation

Context-oriented research makes up a vast part of the existing studies about translation peritexts. While the spectrum of studies in this aspect is very broad and does not lead itself to simple summaries, one way of categorizing the study is in accordance with the interreaction between ideology and society. Hence, it is feasible to discern between research into societies where there is a ruling ideology imposed by people in power, on the one hand, and research into societies in which a variety of ideologies openly contend, on the other. Research in the first aspect is aimed to investigate the ways that the ruling ideology is embedded in paratexts and is interwoven with the wider motif of translation and censorship (Qian, 2017). Giles lived in the Vitoria age (1837–1901), which started with First Opium War (also known as Britain’s invasion of China from 1840 to 1842) and ended with Eight-Power Allied Forces’ suppression of the anti-imperialist Yihetuan Movement of the Chinese people from 1900 to 1901. During this period, Chinese were regarded by the West as “drug addicts” and “the inferior,” China was seen as “backward” and “poor.” In the face of the distorted portrayal of “otherness,” Giles said in the “introduction” that he would make full use of his understanding of Chinese culture to convey a more accurate image of China to the West.

It cost Minford about 14 years to translate Liaozhai Zhiyi into English. His translation was accomplished in 2005 and published in 2006. At this point, China has been implementing the reform and opening-up policy for about 20 years. The return of Hong Kong and Macau to China, China’s successful bid for the Olympics, and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization denote a continuous growth of China’s “hard power” and “soft power.” China is about to play an important role on the world stage. In such a socio-cultural context, the West is eager to learn more about China and Chinese culture. Classical Chinese literature is the cultural treasure of the Chinese nation. Liaozhai Zhiyi, as the pinnacle of short fiction written in Chinese stories, is full of Chinese cultural elements. It is included in Penguin’s “Great Thoughts” series, aiming to open a window for English-speaking readers to understand China.

Minford once wrote in the “Introduction” that a close look at Giles’s version really reveals the limitations of the taste of Giles’ time, which dominates what he considered he could possibly do. Giles had primarily decided to publish a full translation of the entire volumes of Liaozhai Zhiyi; after a detailed reading of a great number of the tales, however, he found that a lot of stories proved to be extremely improper for the time where he lives, unavoidably recollecting the roughness of their own writers of novels in the 1800s. According to the discussion above, it is not hard to see that peritexts in two translations unfold the respective socio-cultural contexts of translation.

4.5 Helping readers understand the past

Research that concentrates on paratexts as products falls broadly into two different categories. The first looks at paratexts as purposes in themselves, and efforts are made to map the paratextual practices that are highly linked with translated texts. This is usually done with regard to a particular period of time or cultural backdrop and is often confined to the text genre or paratextual material. The second kind of research examines paratexts as the means to some other purposes; paratexts are thus regarded as documents or materials that are interesting because they tell people about something else (Batchelor, 2018). At a very basic level, paratexts can be used to find raw materials for historical studies. The information written in a translation’s paratexts, for example, can be critical for tracking the publication history of a particular text, developing a database of translations published by a particular publishing house or in a particular country, or providing the fundamental knowledge of translator biographies (Batchelor, 2018). The appendix in Giles’ translation provides readers with other books written and translated by him, through which readers will become familiar with the translator and appreciate Liaozhai Zhiyi with the help of his other works. Giles’ translation was published again in 2010 with new additions. The appendix includes translator’s biography and suggested readings covering different English translations of Liaozhai Zhiyi, as well as some articles and books about Liaozhai Zhiyi. All these additions will help readers know more about Giles and other scholars’ views on Liaozhai Zhiyi, which in turn will make the translation more understandable. Similarly, Minford also offers similar peritexts in his translation.

At a deeper level, paratexts can be useful for understanding the past in two ways. First, it can serve as documents telling people about the past by means of having been shaped by the past; and second, as documents having impacted the past (Batchelor, 2018). The peritexts in Giles’ and Minford’s translations introduced much about the history and culture of the Qing dynasty (as shown in Table 2), which, to some degree, can not only equip readers with much knowledge of food, clothing, housing, transportation, customs, beliefs, and administrative mechanism in that period but also furnish Western experts studying the history and culture of the Qing dynasty with rich research data. In addition, these peritexts also influence the past. The peritexts in Giles’ translation would give the chance for readers in the Victorian age to get a whole picture of China and reverse the distorted Chinese image produced by some Western medium. Giles’ translation would also influence later translators. Minford in the “Introduction” of his translation, wrote that in naming the selection Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, he was intentionally paying a tribute to Giles and his translation Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, which he has always admired, and he has unhesitatingly adopted certain appropriate phrases in Giles’ version.

4.6 Efficacy of the peritexts

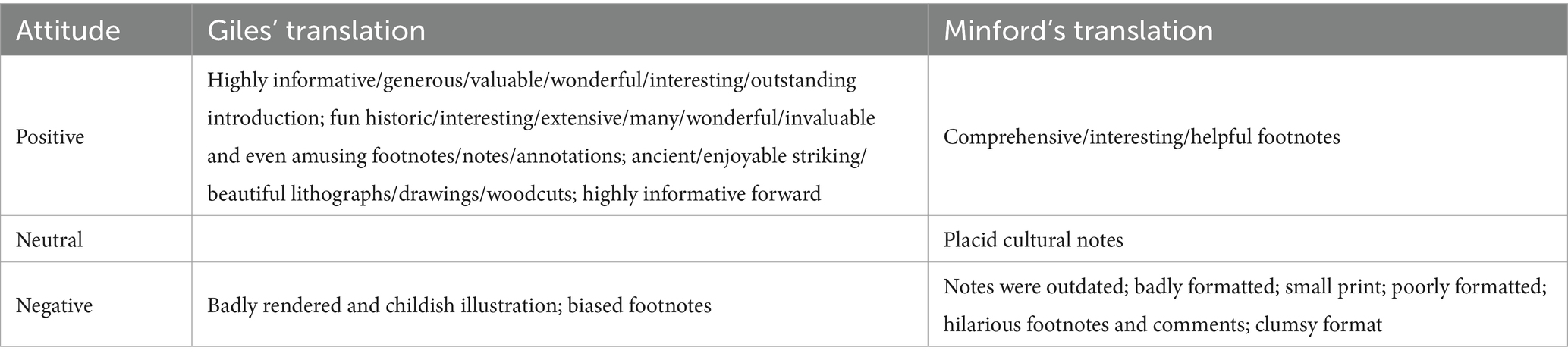

The author believes that if people want to know the efficacy of peritexts, most importantly, they should figure out to what extent readers are influenced by peritexts and how many are influenced. In order to learn about the efficacy of the peritexts in Gile’s and Minford’s translations, readers’ reviews on Goodreads and Amazon were collected in March 2022. With “introduction,” “footnotes,” “annotations,” “illustration,” “forward,” and “notes” as lexical items, the KWIC (key-word-in-context) tool in AntConc was used to retrieve the five collocations on the left and right sides of lexical items, and the key collocations were collected and sorted out, as shown in Table 3.

As is shown in Table 3, readers make positive, neutral, and negative reviews of Giles’ translation while making positive and negative reviews of Minford’s translation. It is clear that some readers are influenced by peritexts in two translations. The “introduction,” “footnotes/notes/annotations,” and “illustration” have the greatest impact on readers. Reader Nigel Jackson (Amazon customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.), Alwynne (Goodreads customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.), and Laurie (Goodreads customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.) said that illustrations, an excellent introduction written by the translator Minford, a terminology list, references, and huge background notes on most stories add to completeness of the reading experience. Bucky K (Amazon customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.) wrote, “Minford’s version is a very enjoyable and readable English translation with wonderful background notes and annotations. The background information alone in this book is worth the purchase.” Ming Yen Phan (Goodreads customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.) said, “the annotation, scholarship and notes in Minford’s translation certainly enrich the reading experience and provides a historical and literary context to the stories.” Gabrielle (Goodreads customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.) reviewed, “John Minford, as translator and editor was up to the job of placing these short stories of the Supernatural and Strange their proper context, no small feat. His explanation of later commentaries and thoughtful translation of the author’s prolog poem were very useful in understanding the world these tales emerged from. The reproductions of late 19th Cen. woodcuts for each of over a hundred stories was a real bonus, making this edition truly enjoyable.” Based on the above reviews, a conclusion can be drawn that peritexts in Minford’s translation have a more positive impact on readers. In contrast, only a few readers believe that the footnotes in Giles’ translation are comprehensive, interesting, and helpful. Elizabeth Bennet (Goodreads customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.) commented, “Keep in mind that Giles’ notes are a bit outdated as regards to political correctness though.” HK (Amazon customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.) pointed out, “Giles provides a short bio of himself as an introduction before his biography of Pu Singling. The intro and the stories are poorly formatted. Mult-page tales are one continuous paragraph. There are also no page numbers. If the reader can endure these inconveniences this print edition is acceptable.

On Amazon and Goodreads, for Giles’ translation and Minford’s translation, the author collected 34 and 189 reviews, respectively, among which 9 and 56 reviews are for peritexts (Amazon customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.; Goodreads customers’ reviews from 2008–2022, n.d.). According to the data, it is apparent that peritexts affect only some readers. This is also in line with Genette’s description that just as the presence of paratextual elements is not uniformly obligatory, so, too, the public and the reader are not unvaryingly and uniformly obligated: no one is required to read a preface (even if such freedom is not always opportune for the author), and as we will see, many notes are addressed only to certain readers. The number of readers’ reviews on different types of peritexts in the two translations is shown in Table 4.

5 Conclusion

Guided by the Genette’s “Paratexts,” this article first examines the peritexts’ strategy in two translations, including the cover, Introduction to the Author/Translator, acknowledgments and preface, introduction, notes, illustrations, and appendices. Then the main functions of the peritexts in Giles’ and Minford’s translations of Liaozhai Zhiyi can be summarized as follows: revealing translator’s or (and) client’s translation aim(s), showing translator’s or (and) client’s peritext strategy, disseminating Chinese culture, unfolding socio-cultural contexts of translation, and helping readers understand the past. Finally, after analyzing readers’ reviews, the efficacy of the peritexts in two translations can be found: Genette (1992). The peritexts in Minford’s version are diversified, more interesting, and readable. The illustrations are favored by some readers. Minford’s and his client’s peritext strategies attract readers to some extent (Ma, 2022). The peritexts in Minford’s translation spread Chinese culture more effectively than those in Giles’ translation (Sun, 2016). The peritexts in Minford’s translation promote the reception of Liaozhai Zhiyi to a large degree, while the peritexts in Giles’ version may deter potential buyers (Dodd, 2013). Some terminologies or culture-loaded words are translated more accurately in the peritexts of Minford’s translation and can be used as second-hand data for Western scholars to study the history and customs of the Qing dynasty. Conversely, limited by the historical background, some expressions in the peritexts of Giles’ translation are outdated and less reliable.

Recent years have witnessed the going-global of Chinese literary works. Chinese and international researchers have also started to pay attention to the reception of these works in targeted culture. However, most researchers just focus on the reception of translated texts of Chinese classics or hit literary works like The Three-Body Problem in targeted culture. Rarely do they fully examine the role peritexts and epithets play in the reception of these works. As Genette stated, peritexts often leave a great impact on readers, whereas epitexts have little impact on readers. This article, after giving a detailed description of peritext strategy and function, experimentally discusses peritexts’ influence on readers’ reception of Chinese classics by Liaozhai Zhiyi. The research confirms that the peritexts adopted by different translators have a huge impact on the readers’ reception of the novel. Thus, it is suggested that the combination of paratext theory and reader response theory can be used to reveal the efficacy of the paratexts of different translations of the same Chinese literary work or other genres of work in targeted culture, find out the law of reception in this aspect, and finally help the smooth and fast going-global of Chinese culture. Deep though it delves into peritexts’ influence on readers, this article does not deal with the role of epitexts play in the reception of selected work, which cannot fully unroll the whole paratexts’ role in the reception of Liaozhai Zhiyi. Readers’ reviews of Giles’ and Minford’s translations show that epitexts like publishing houses and other readers’ reviews also influence their reading. The author will try to figure out the role of epitexts plays in the reception of the two translations of Liaozhai Zhiyi in the later research, striving to give a panorama of the reception of Liaozhai Zhiyi in English world.

Author’s note

ZL is a lecturer at the English Department, School of Foreign Languages, Guangzhou City University of Technology, China. He completed his master’s program at Xi’an International Studies University, China. His research interests are translation studies of Chinese literary classics and corpus-based translation studies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author declares that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study is funded by the Guangdong Provincial Private Education Association. The project “The English Translation Strategy and Function Realization of Story Titles in Liaozhai Zhiyi—A Translator Behavior Criticism Approach” (GMG2024074).

Acknowledgments

Sincere gratitude is extended to Wu Chuanling, Zeng Lvdan, and Lai Lishan for collecting data and to Zhang Yuanmeng for her language editing services.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aiello, L. (2013). After reception theory: Fedor Dostoevskii in Britain, 1869–1935. London: Modern Humanities Research Association and Routledge.

Amazon customers’ reviews from 2008–2022. (n.d.) Available at: https://www.amazon.com.au/Strange-Chinese-Studio-Penguin-Classics-ebook/product-reviews/B002RI9JPA/ref=cm_cr_dp_d_show_all_btm?ie=UTF8&reviewerType=all_reviews [Accessed 31st March, 2022].

Dodd, SL. (2013). Monsters and monstrosity in Liaozhai zhiyi [dissertation]. Leeds: The University of Leeds.

Geng, Q. (2016). Paratext in translation and translation studies: perspectives, methods, issues and criticism. J. Foreign Lang. 5:104.

Goodreads customers’ reviews from 2008–2022. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/155054.Strange_Tales_from_a_Chinese_Studio?ac=1&from_search=true&qid=5KRnMe0TwY&rank=1#other_reviews [Accessed 31st March, 2022].

Li, Z. S., and Zhu, H. M. (2021). A study on the functions of Paratext: taking five English versions of translation of poems of Mao Zedong as examples. J. Nanjing Institute of Technol. (Soc. Sci. Edition). 1, 1–6.

Ma, RF (2022). Liaozhai Zhiyi a classical Chinese novel that has been translated into the most foreign languages. Available at: http://new.sohu.com/06/01/news144910106shtml [Accessed 31st March].

Qian, M. H. (2017). Penguin classics and the canonization of Chinese literature in English translation. Transl. Lit. 26, 295–316. doi: 10.3366/tal.2017.0302

Shao, L., and Zhou, Y. (2022). Paratext strategies and reader reception in translation: exemplified by dissemination of Yu Hua’s works in America. Foreign Lang. Literature (bimonthly). 1, 10–19.

Shi, C. R., and Zhou, Z. H. (2020). A study on the multimodal Paratext and its functions in Harold Shadick’s English version of the travels of Lao Ts’an. Lang. Educ. 3, 63–67.

Smith, C. J. (2019). The sound of a beautiful woman [dissertation]. Austin (TEX): The University of Texas at Austin.

Sun, X. Y. (2016). A study on translation of Liaozhai Zhiyi from the perspective of hermeneutics. Shanghai: SDX Joint Publishing Company.

Tso, W. B. A. (2017). Repressed sexual modernity: a case study of Herbert Giles’ (1845 - 1935) rendition of Pu Songling’s strange stories from a Chinese studio (1880) in the late Qing. Acta Linguistica Asiatica. 7, 9–18. doi: 10.4312/ala.7.2.9-18

Vermeer, H. J. (1986). “Übersetzen als kultureller Transfer” in Übersetzungswissenschaft — Eine Neuorientierung: Zur Integrierung von Theorie und Praxis. ed. M. Snell-Hornby (Tübingen: Narr), 30–53.

Vermeer, H. J. (1989). “Skopos and commission in translational action” in Readings in translation. ed. A. Chesterman (Helsinki: Oy Finn Lectura Ab), 173–187.

Vermeer, H. J. (1990). Skopos und Translationsauftrag: Aufsätze. Institut für Übersetzen und Dolmetschen: Heidelberg, Selbstverlag.

Wang, S. H., and Wei, Y. Q. (2022). The formation, function and formation mechanism of Peritexts in Minford’s translation of Liaozhaozhiyi. Foreign Lang. Res. 1, 85–89.

Xin, H. J., and Tang, H. M. (2019). An interpretation of Gladys Yang’s views on translation from the perspective of Paratext: a case study of the English translation of leaden wings. Foreign Lang. Cultures. 2, 126–125.

Yin, Y., and Liu, J. P. (2017). Paratextual studies in China (1986—2016): a Scientometric analysis by using CiteSpace. Shanghai J. Translators. 4:22.

Keywords: Liaozhai Zhiyi, strategy, function and efficacy, Herbert Giles, John Minford

Citation: Liang Z (2024) The strategy, function, and efficacy of the peritexts in Giles’ and Minford’s English translations of Liaozhai Zhiyi. Front. Commun. 9:1419455. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1419455

Edited by:

Changsong Wang, Xiamen University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Lucyann Snyder Kerry, Canadian University of Dubai, United Arab EmiratesFlorin RADU, Valahia University of Târgoviște, Romania

Sang Kun, Xiamen University, Malaysia

Copyright © 2024 Liang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhao Liang, emhhb2xAZ2N1LmVkdS5jbg==

Zhao Liang

Zhao Liang