95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 09 July 2024

Sec. Culture and Communication

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1413110

This article is part of the Research Topic International Translation Day: A Communication Perspective View all 7 articles

Over the last few decades, the English language has become prevalent throughout the world in the domains of international diplomacy, business, research, and technology and is becoming increasingly important in many other areas. Much research into the use of English as a lingua franca has focused on its role in fostering communication across linguistic and cultural boundaries. Recently, however, concerns have been raised about the additional cognitive load that having to function in a non-native language can place on interlocutors. In an international survey, 883 professional language mediators (i.e., translators, conference interpreters, and community interpreters) provided details about their experiences dealing with the English produced by native vs. non-native speakers and identified features and difficulties associated with processing the respective input as well as their coping strategies. Although they acknowledged that both native and non-native speakers produce English that is difficult to deal with, the language mediators largely agreed that the latter were much more likely to do so, with vocabulary use, word choices, and sentence structures identified as particularly problematic. The main coping strategies for all three groups were to really concentrate on the message being conveyed, try to improve the formulation of it for the target audience, and intervene in the communication situation for clarification if possible. Self-regulation and reliance on information external to the situation were also mentioned as very important. Although almost half of the participants said that they preferred to work with native speaker produced output, many expressed no preference. The study results have important implications for various situations involving non-native speakers of the language being used for communication.

English as a lingua franca (ELF) has been studied since the 1990s within the disciplines of applied linguistics and sociolinguistics, usually from the perspective of conversational communication in international settings. The focus has been on the non-native speaker (NNS) of English, even though ELF, defined as a mode of communication in international settings, does not exclude native speakers (NS) of English (Jenkins, 2007). It has been argued in the ELF literature that it is not possible to delineate and define the notions of NS or NNS and that standard languages are simply codified conventions with no real-life correspondence. However, as detailed in Albl-Mikasa and Gieshoff (2024), it can still be legitimate to use terms such as ‘native’ or ‘non-native speaker’ or ‘non-standard’ input, because of the clear differences in the way NS and NNS learn and store the language. Moreover, as subjective mental constructs, those notions are psychologically real and intuitively appealing. They are therefore still in use in a substantial body of pertinent literature and also used throughout this paper.

With the focus on NNS, ELF research findings highlight successful ELF communication based on “shared communication strategies, a collaborative disposition, and the deployment of linguistic resources shaped by similar Englishing experiences” (Hall, 2018, p. 79). Collaboration and shared strategies include the joint engagement in “interactional and interpretive work in order to sustain the appearance of normality” (Cogo and House, 2018, p. 211), “a remarkable ability and willingness to tolerate anomalous usage and marked linguistic behavior even in the face of what appears to be usage that is at times acutely opaque” (Firth, 1996, p. 247) and joint discourse production via co-construction, meaning negotiation, and other strategies. The deployment of linguistic resources includes “multilingual practices” and the “highly flexible use of resources” (Cogo, 2018, p. 363). Galloway (2018) sums this up with reference to the Routledge Handbook of English as a Lingua Franca (p. 471):

As is evident from various chapters in this handbook, ELF research showcases what ELF users ‘do’ with the English language, how they appropriate it when they communicate and what strategies they use to achieve successful communication, including the use of their plurilingual resources. It highlights how ELF users exploit the language creatively and push the boundaries of native English […].

The common thread running through almost all chapters of the handbook mentioned above as well as other key contributions on ELF is an emphasis on communicative success and efficiency (e.g., Jenkins et al., 2011; House, 2013; Mauranen, 2013). This may hold for NNSs of English in conversational or other dialogical settings who have the possibility of asking for clarification or confirmation, but becomes debatable for most (non-public service) interpreting and translation work, which resembles a monological setting because there is little or no access to the source language producer. As a result, some 35 years into ELF research, the study of English as a lingua franca in relation to interpreting and translation (ITELF) has gained momentum. Researchers posit that, due to deviations from standard form at the pragmatic, syntactic, morphological, and lexico-semantic levels, additional load may be associated with processing ELF input, with a consequent effect on the efficiency of such processes and the quality of the product. An early study found non-standard speech to be a potential problem trigger (Kurz and Basel, 2009), and challenges such as comprehension and processing difficulties have been reported by interpreters and translators in a number of questionnaire surveys (Albl-Mikasa, 2010; Bendazzoli, 2020; Rodríguez Melchor and Walsh, 2020).

Moreover, many interpreters have questioned the assumption of the communicative effectiveness of ELF speakers. In Scardulla’s (2020) survey, covering 25% of the active population of interpreters working for the EU Directorate General for Interpretation (DG SCIC), two questions directly addressed ELF communicative effectiveness. Respondents perceived it as decreasing and judged that fewer than half of the speakers could express themselves effectively when using ELF. This is associated with consequences not only for communication quality, but also for participation and floor-taking in important discussions. When facing ELF-induced challenges, though, language experts such as interpreters would seem uniquely equipped to deal with them. Using comprehension testing as a means of measuring communicative effect, Reithofer (2010, 2013) provides evidence that the understanding of source speeches in conference settings can be significantly higher among conference participants listening to professional interpretation into their first language (L1) than those listening to the ELF original.

Such findings have led to ITELF-related research that calls into question the tenet of (generally) successful ELF communication and addresses the challenges and potential cost involved in mediation involving ELF speakers (for an overview see Albl-Mikasa, 2022). For example, the CLINT (Cognitive Load in Interpreting and Translation1) project looks into possible ways of measuring the cognitive demands of processing ELF input and also the coping strategies targeted at reducing or managing those demands (e.g., Albl-Mikasa et al., 2020; Boos et al., 2022). An assumption underlying such ITELF-based research is that language mediation training can help people cope with various types of English produced by NNSs. As part of the larger CLINT project, an international survey was conducted among the communities of practice to explore whether and how professional translators, conference interpreters, and community interpreters think ELF input influences their work. While the monological-like settings of translators and most conference interpreters do not apply to community interpreters who work in dialogical settings, interpreting under ELF conditions is similar for the latter in that the dialog is not going on between two ELF speakers. Instead, as with translators and conference interpreters, the community interpreter receives ELF input from one of them, which is then conveyed in a standard target language in compliance with fidelity standards.

The study reported in the present paper sets out to address three main research questions concerning those three groups of language mediators:

1. How often do language mediation professionals have to work with English produced by non-native speakers compared with that produced by native speakers of English (NS)?

2. What differences do they identify in terms of the features and difficulties associated with processing NS- and NNS-produced input?

3. What strategies do they use to cope with major difficulties identified in NNS input?

These fundamental questions concerning ELF in language mediation work have been seriously under-researched to date. Bendazzoli (2020), in his survey of (247) Italian interpreters and translators, is among the very few who have addressed any of them. He lists a fair number of strategies reported by interpreters and translators in dealing with ELF, dividing them up into strategies geared toward comprehension, production and professional practices. He does not provide details, however, on the number of mentions for each strategy and remains somewhat vague regarding the difficulties they are meant to counter. Other than that, there have only been cursory presentations of strategies used by interpreters in dealing with ELF, based on 10 interviews each for the Taiwanese (see Chang and Wu, 2014) and German/Swiss context (see Albl-Mikasa, 2013).

In the next section, we explain the methodology deployed for our survey of the communities of practice and describe our sample of respondents. The analyses of the quantitative results presented in the subsequent section were done with a view to answering the first two research questions in depth, and the analyses of the comments the respondents made about their coping strategies address the third research question.

The design of the study was based on a concurrent mixed-method approach, with a survey instrument that allowed both closed and open questions that provided quantitative and qualitative data, respectively. We acknowledge the limitations of quantitative self-report data that can be collected through questionnaire items with a restricted number of pre-formulated options, even if there is the possibility for respondents to individualize their responses as well as the potential of sampling error that can have an impact on the generalizability of the results presented in the next section (cf. Saldanha and O’Brien, 2013).

Our research pragmatic solutions to the various potential threats to validity and reliability have been explained below in the relevant sub-sections. First the development, pilot testing, and final form of the online questionnaire are described in Section 2.1 and, in the interests of transparency and replicability, the survey questionnaire has been published (Albl-Mikasa et al., 2024). The efforts at dissemination of the survey are described in Section 2.2, and detailed information about the sample is provided in Section 2.3.

The survey items were developed and formulated by the project team, consisting of three translation and three interpreting researchers. As inspiration for some of the questions, the team consulted Bendazzoli (2020), Ehrensberger-Dow et al. (2016), and Albl-Mikasa (2010).

The survey items were formulated exclusively in English since the survey was designed specifically for participants who had English as one of their working languages. All items were pilot tested by potential addressees (who did not take part in the final version of the survey), and adjustments were made in an iterative process. The order of the items was organized to reflect an interest in discovering more about the quality of English source texts or talks that the practitioners work with, irrespective of whether they had been produced by NSs or NNSs of English. Mention of ELF was avoided until toward the end of the survey to avoid any bias or confusion associated with the use of that term.

The survey was set up in REDCap2, a licensed version of a secure, browser-based survey tool with all data stored on the university’s own servers. Anonymity of the participants was ensured as their responses could not be linked to their email or IP addresses, and they were not asked to provide any identifying details such as name, company, address or date of birth.

The survey started with a short description and a consent form that needed to be approved before the rest of the survey could be accessed. If consent was not given, then a message appeared thanking the individual for their interest and asking them to close their browser. Once consent was given, the respondent worked through several sections comprising various numbers of items, some of which had sub-questions or response boxes that were triggered by certain responses. The tracks of the survey were customized to address professional translators, conference interpreters, or community interpreters, respectively.

The survey was divided into the following eight sections:

1. General information (demographics and personal language history)

2. Difficulties in processing English input in general and NS- vs. NNS-produced English source texts/talks in particular

3. Impact on the professionals’ work of poor English source texts/talks in general and of NNS-produced English source texts/talks in particular

4. Handling of/coping with certain aspects of NNS-produced English source texts/talks

5. Exposure to NNS English in other contexts

6. Beliefs and attitudes toward English as the global lingua franca in work settings

7. Knowledge about ELF and its integration in translation and interpreting training

8. An invitation to indicate any questions they would have liked to see in the survey

The number of compulsory items was kept to a minimum in order to increase the likelihood of respondents working all the way through the questionnaire. Depending on the branching paths taken after particular answers, respondents were presented with 66 to 128 items.

The call for participation in the study was distributed via professional associations (e.g., to members of FIT, AIIC, etc.) as well as to professional and personal networks using e-mail, Twitter (now X), and LinkedIn. The survey was open from mid-March until the end of June 2022, and reminder calls were issued intermittently.3

The participants who consented to do the survey had to first indicate their current primary occupation as being either translator or interpreter, which led them to a similar but slightly adapted track of items depending on their response. A total of 883 professionals participated in the survey, of whom 558 specified they were translators, 23 posteditors, 185 conference interpreters, and 117 community interpreters. Since one of the translators did not have English as a language, that data was excluded. In the following analyses, the translators and post-editors are subsumed under translators (n = 580). Because most of the items were not compulsory, the percentages reported are based on the actual number of responses to a particular question and not on the total number of participants in each group. The sample is described below with respect to the relevant features of the respondents.4

Three-quarters of both the translators and the conference interpreters were distributed quite evenly among the age ranges of 31–40, 41–50 and 51–60 years (see Table 1). The age distribution was less even among the community interpreters, with fewer respondents being under 40 and the largest group (34%) over 60 years old. With regard to gender, the vast majority of the respondents identified as female (translators: 70.0%, conference interpreters: 72.4%, community interpreters: 81.7%).5

Almost one-third of the translators reported having worked up to 10 years in this profession (see Table 2), followed by those who have worked for 11 to 20 years (30%). Among the conference interpreters, the largest group (30%) has 21 to 30 years of work experience, followed by those with 11 to 20 years of experience (25%). Among the community interpreters, just over half have up to 10 years of work experience, followed by those with 11 to 20 years (27%).

Respondents were also asked to estimate the percentage that they had worked on average per year over the past 5 years (see Table 3). More than half of the respondents in all three groups reported having worked 60% or more (i.e., 65% of the translators, 68% of the conference interpreters and 56% of the community interpreters). This means that most of the responses were provided by very active professionals.

Most respondents reported working only freelance, with the highest percentage among the conference interpreters (83% versus 56% of the translators and 48% of the community interpreters). Staff employment is the second most frequent status for the translators and conference interpreters (34 and 11%, respectively). 17% of the community interpreters are staff employees and more of them combine freelance and staff work than the other groups (36% versus 11% of the translators and 6% of the conference interpreters).

When asked about their professional contexts, many respondents indicated more than one and a small proportion of each group left the question blank. The 556 translators who responded to this question indicated a total of 942 contexts; the 179 conference interpreters a total of 525 contexts; and the 109 community interpreters a total of 362. By far the largest proportion of the translators work in the private sector (62%) followed by international institutions (38%; see Figure 1). For the conference interpreters, it is the private sector and international institutions that are clearly the biggest commissioners (for 80 and 70% of them, respectively). Most of the community interpreters indicated that they work in the healthcare sector (86%) and for government (74%). It must be noted, however, that there is a degree of overlap in the answer choices provided for this item (e.g., government and international institutions), and they might have been understood differently by the various respondents. Nevertheless, the groups seem to have quite different profiles with respect to the contexts they work in.

In both interpreting groups, some participants reported that they also work in settings other than the one they identified as their primary occupation (see Table 4). They also work in other language-related roles, most frequently as translators (i.e., 85% of the conference interpreters and 65% of the community interpreters). This question was not asked of the translators.

With respect to their working languages, more than half of the translators reported that they work into one active language and about one-third into two (see Figure 2). The converse is true for the conference and community interpreters, since most have two active languages and far fewer have only one. The number of languages that translators work out of is higher than the number they work into (i.e., most often two or three), similar to the community interpreters. Respectively more of the conference interpreters reported that they work out of three or even four languages.

The most frequently mentioned active languages by the translators (i.e., by at least 5%) are English, German, French, Spanish and Italian. For the conference interpreters, English is the most frequent, followed by German, Spanish, French, Mandarin Chinese and Italian. The community interpreters had a wider range, although they also mentioned English most often, followed by Arabic, Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, French, German, Italian, and Persian.

The most frequent languages that the translators work out of are similar to their active languages: English, French, German, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese. For the conference interpreters, English is followed by French, Spanish, German, Italian, Portuguese, Dutch, and Russian. The community interpreters mentioned English far more often than the other languages, which included Arabic, Mandarin Chinese, French, German, Italian, and Japanese.

As explained in Section 2.1, respondents were guided through the survey with questions about difficulties in processing (poor) English input in general before those that zeroed in on NNS-produced source texts or talks in particular. In the following, we first present the quantitative findings about the respondents’ exposure to NNS English in order to establish how widespread the use seems to have become in the work of language mediators (Section 3.1). To address the commonly expressed assumption that many NS-produced texts are not necessarily of better quality than NNS-produced texts, the survey included questions directed toward identifying common difficulties encountered in English texts in general, independent of who produced them (Section 3.2) before moving respondents on to questions about common features of poor English texts produced by NSs and NNSs, respectively (Section 3.3). Since some features of poor-quality texts might be easier to deal with than others, we specifically asked respondents to identify (a number of) major difficulties in processing NNS-produced texts and to explain how they coped with those (Section 3.4). Finally, some of the survey items addressed respondents’ preferences for NS- vs. NNS-produced texts, with a view to corroborating or refuting a deficit-oriented view (Section 3.5).

In response to the question about the English source texts or talks they usually have to deal with, 63% of the translators, 86% of the conference interpreters, and 49% of the community interpreters estimated that about half or more of the source texts they translate or interpret are produced by NNSs, which suggests that this phenomenon is very widespread (see Table 5).

The basis for the estimated proportions of NNS source texts in Table 5 is not entirely clear, though, since most of the participants in each group are rarely or never provided with information about whether the English source text was produced by a NNS (see Table 6). However, the large majority of the respondents in each group estimated that they can usually or always recognize whether the source text has been produced by a NNS of English. The high proportions in the groups of interpreters (97% for conference interpreters and 88% for the community interpreters) could be because of their having the additional information of the speaker’s accent, but the translators also seem quite confident about recognizing NNS-produced source texts (i.e., 88%).

This might be attributable to the tacit knowledge these language professionals have acquired through their regular experience of dealing with NNS English, not just working with NNS-produced source texts but also apart from source texts and outside of work (see Table 7), which probably reflects the reality of countless other individuals in modern society. Only a minority of each group are exposed to NNS English other than source texts less than once a week either at work or outside of work.

The respondents were asked to identify the most common difficulties they encounter in English texts or talks in general (i.e., independent of whether they were produced by NSs or NNSs) from a choice of 19 options, including ‘other’ (see Supplementary Appendix 1 for the complete list and the percentages for each group). Although one-third or more of all three groups mentioned vagueness and lack of logic as problems, the other five issues most frequently mentioned by at least 25% of each group varied widely depending on their professional profile. For example, the translators also identified complex sentence structures, non-existent or different concepts in the target culture, technical terminology, no lexical equivalent, and long sentences as difficulties whereas the conference interpreters were more concerned with high delivery speed, unusual accent/spelling/pronunciation, high information density, culture-specificity (i.e., puns, jokes, humor, idioms), and register shifts. The community interpreters shared concerns with both groups as well as identifying many others, with unusual accent/spelling/punctuation, non-existent or different concepts in the target culture, culture-specificity (i.e., puns, jokes, humor, idioms), high delivery speed, and technical topics the most frequent.

When asked about the proportion of source texts/talks produced by English NSs that they would consider poor and, in a later item, the proportion of poor source texts/talks produced by NNSs of English, the groups seemed to be quite sensitive to the difference (see Table 8). A Fisher’s exact test was conducted on the raw counts within each group to test whether the reported proportion of poor source text quality is related to whether it was assumed to be produced by an English NS or NNS.6 The test showed a significant association for all three groups (i.e., translators: two-tailed p < 0.001; conference interpreters: two-tailed p < 0.001; community interpreters: two-tailed p = 0.004) such that the respondents considered a higher proportion of source texts produced by NNSs to be of poor quality. However, it is important to bear in mind that most of the respondents, although they might feel certain about the source, cannot actually be sure whether a given text is produced by a NS or NNS of English since they are rarely provided with this information (see Table 6).

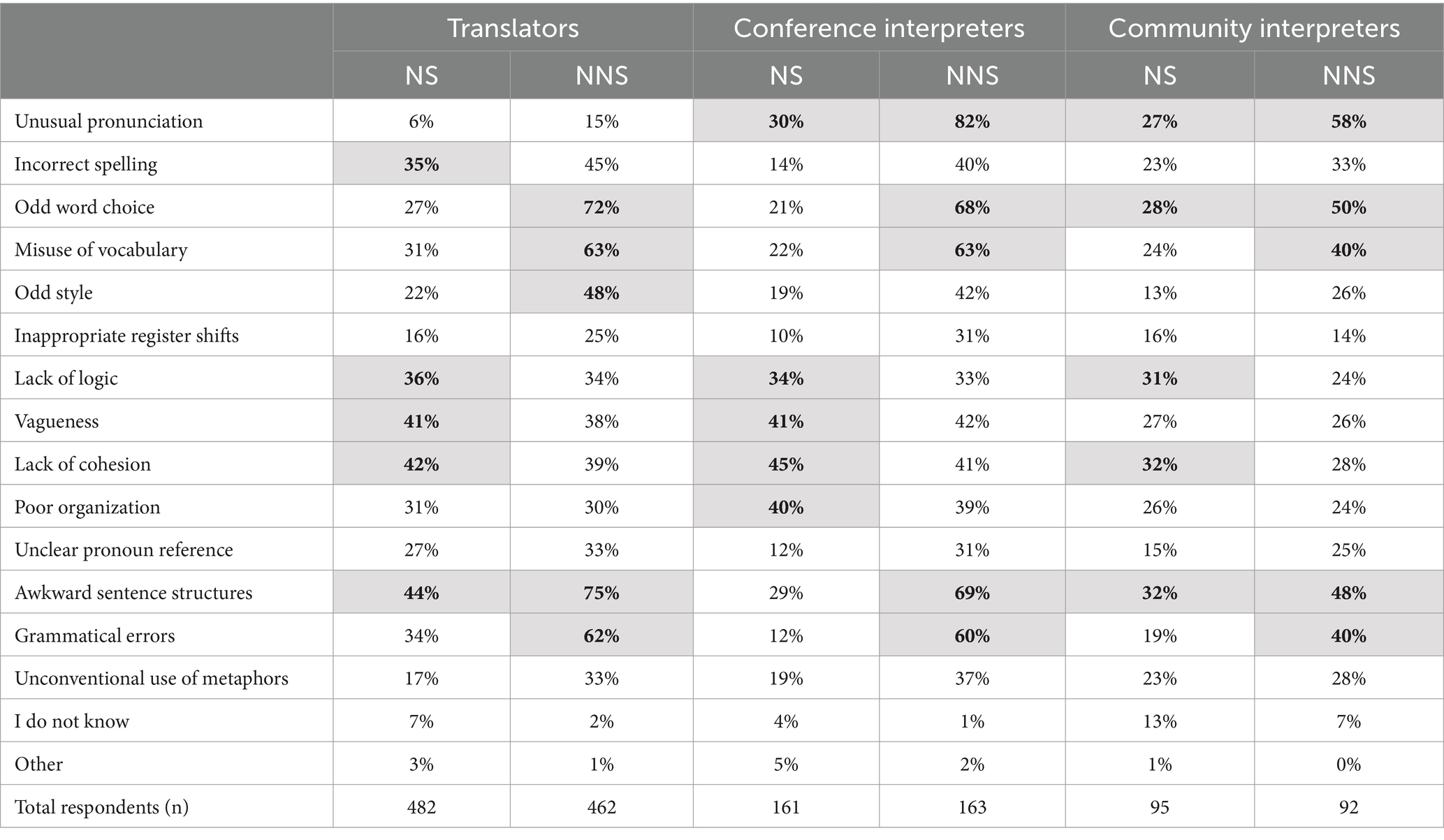

Respondents were then asked in two separate items to identify features of poor source texts produced by (a) native speakers of English and (b) non-native speakers (see Table 9, listed in the same order as in the survey, with the number of respondents to each item in the bottom row). They could indicate multiple features and also had the possibility to choose ‘I do not know’ (67 responses) or add a feature not included in the list in a comment field (31 responses). Similar to the results for difficulties associated with processing English input in general (discussed above and presented in Supplementary Appendix 1), there were differences depending on the professional profile of the group (the five most frequently mentioned are indicated in bold in the shaded cells). In general, the frequencies of mention were higher for poorly produced NNS source texts, whereas there was less consensus and greater spread in the features identified as characteristic of poor NS texts. There are also differences among the groups depending on whether the feature was evaluated with respect to NS or NNS source texts, although some patterns are discernible. For example, lack of logic, vagueness and lack of cohesion were most commonly identified as features of poor NS texts whereas oddness of word choice and/or style and errors in vocabulary and grammar seemed particularly characteristic of poor NNS texts. Unusual pronunciation was high on the list for both groups of interpreters, and awkward sentence structures frequently identified for both poor NS and NNS texts by all three groups. These results show that effective communication cannot simply be attributed to nativeness and that our respondents were very nuanced with respect to their evaluations of NS and NNS texts.

Table 9. Features of poor source texts produced by native or non-native speakers of English (five most frequently mentioned by each group in bold in the shaded cells).

In order to test whether the features of poor source texts were considered significantly different, we compared the response rate for those assumed to be produced by NNSs with the response rate for NS texts (expected success rate) by conducting binomial tests for each feature and group separately (see Supplementary Appendix 2 for all test statistics, including non-significant results). Features that were added in the comment field by the respondents, as well as the ‘I do not know’ answer option were excluded from the analysis since there was an insufficient number of them. The analyses suggest a great deal of overlap between groups for the features of NNS-produced source texts: unusual pronunciation (p < 0.001), incorrect spelling (p = 0.036–0.001), odd word choice (p < 0.001), misuse of vocabulary (p < 0.001), odd style (p < 0.001), unclear pronoun reference (p = 0.011–0.001), awkward sentence structure (p = 0.002–0.001), and grammatical errors (p < 0.001) were selected significantly more often than for source texts produced by English NSs. Moreover, conference interpreters and translators mentioned inappropriate register shifts (p < 0.001) and unconventional use of metaphors significantly more often for source texts assumed to be produced by NNSs than those produced by NSs (p < 0.001).

Features that are identified as typical of texts produced by NNSs may not always be equally problematic, depending on the task demands and context. In order to better understand what language mediation professionals find especially difficult about interpreting or translating NNS-produced texts, respondents were asked to identify five main difficulties from a list of options. They also had the possibility to add further difficulties, but few were mentioned. Other than for pronunciation, which the interpreter groups (and not the translators, for obvious reasons) considered a problem, the groups were quite similar in their identification of the main difficulties they associate with dealing with NNS-produced texts (see Figure 3). Similar to the pattern observed for the most common features of poor NNS-produced texts (see Table 9), misuse of vocabulary, odd words, and sentence structures were identified as particularly problematic, as were cohesion and vagueness to a lesser degree. Aspects such as register shifts, spelling, and unclear reference seemed less difficult to deal with for all the groups, perhaps because they affect source text comprehension less and can be compensated for during target text production or because they are less consciously noticed.

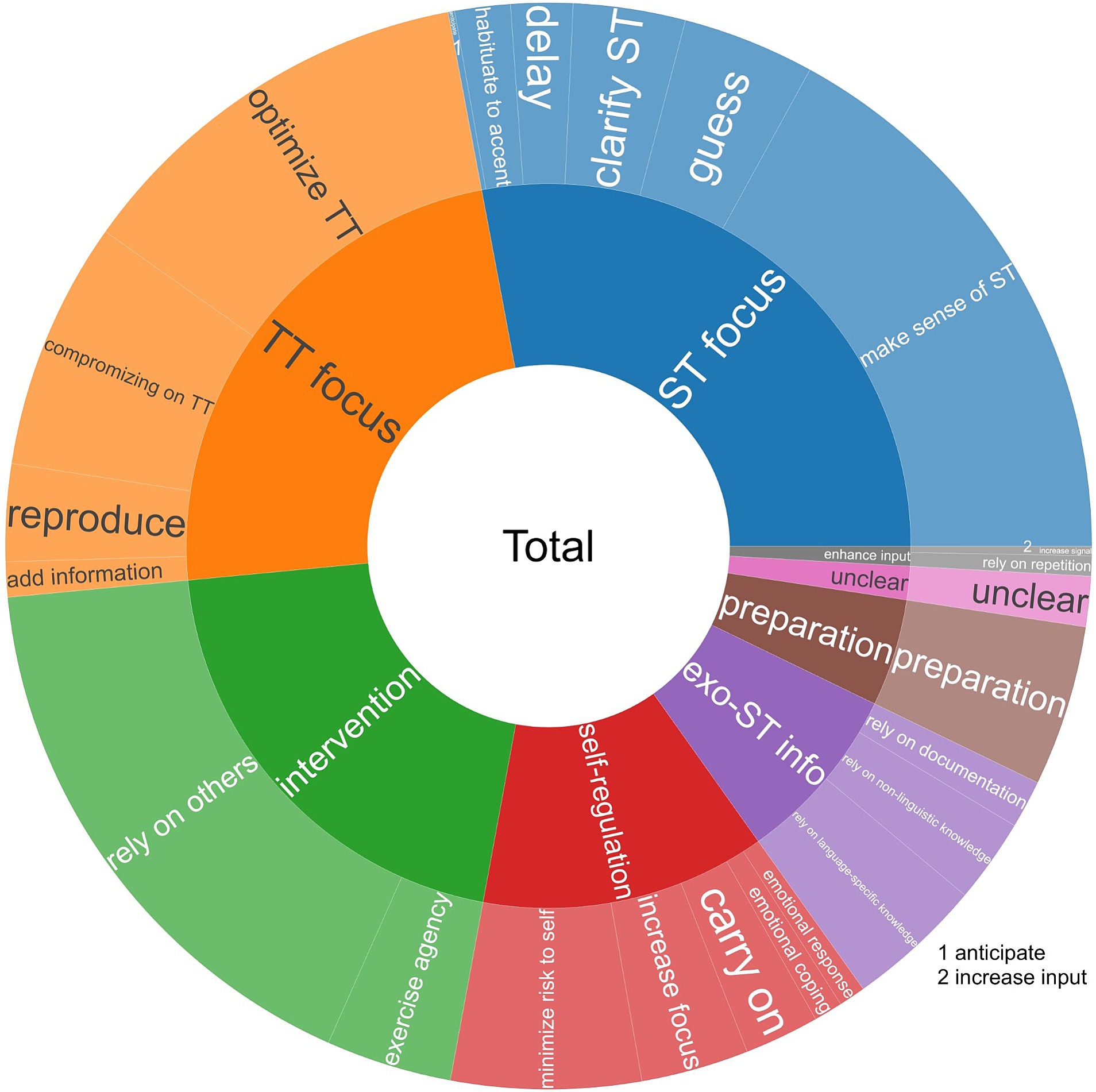

Not all of the respondents who selected a difficulty actually commented on it, and some made more than one comment about how they coped with a particular difficulty. In total, there were 1,974 comments made about coping strategies, which were subjected to a multi-cycle coding process. Every comment, many of which contained several ways of dealing with a difficulty, was labeled with at least one and up to eight codes (so as to capture each mention of a strategy) by two of the team members and unclear cases were resolved with another. Finally, a fourth team member independently coded a random selection of 5% of the comments to test the reliability of the first-level code labels and descriptions. Since the level of agreement was 95.7%, the team proceeded to collaborative second-level coding in which the 163 first-level codes were grouped and rearranged in an iterative process that resulted in 24 s-level codes (i.e., “constituent codes” in the outer circle of Figure 4). The last step was a collaborative process of grouping the second-level codes into 8 third-level codes (themes) to describe how the three groups of participants cope with the main difficulties they associate with NNS-produced texts (see the inner circle of Figure 4).

Figure 4. Themes (inner circle) and constituent codes (outer circle) that describe how participants cope with main difficulties of NNS-produced texts.

As can be inferred from Figure 4, the main strategies7 employed to deal with NNS-produced input are (1) focusing on the source text (trying to make sense of it; at times guessing; clarifying the source text by, for instance, plausibility checks; delaying production to get further information; habituation to the accent), (2) focusing on the target text (optimizing it or making compromises on it or adding information or even reproducing an oddity); and (3) intervening (relying on others, such as clients or boothmates; seeking clarification or exercising agency by asking the client or speaker to, e.g., choose from different options or to slow down). The next most frequent strategies employed are self-regulation (minimizing risk to self, e.g., by informing the audience or declining a job; increasing focus through concentration and additional effort; carrying on by, for instance, disregarding irregularities; or emotional coping and response, ranging from eating chocolate to taking a deep breath and praying) and reliance on exo-source text information (be it language-specific or non-linguistic knowledge or documentation). Finally, less commonly mentioned strategies are preparation and enhanced input (e.g., by turning up the volume).

Not surprisingly, considering the nature of their mediation tasks, the three groups differ in how they cope with difficulties (see Figure 5). The community interpreters report using intervention much more often than the other groups do (i.e., by relying on others or exercising their own agency), whereas focusing on the source text, especially to try to make sense of it, is the number one strategy for conference interpreters and translators. While intervention to seek clarification is hardly an option for conference interpreters, this is resorted to quite frequently by the translators. Also commonly referred to by all three groups is a focus on the target text, with the professionals seeking to optimize it, find compromises, or add information. The self-regulation responses mentioned above are also felt to be necessary by all three groups, while reliance on exo-source text information is clearly more frequently employed by conference interpreters and translators than by community interpreters. Finally, the need for preparation is felt, to a lesser degree, by all three groups.

The focus on difficulties and coping strategies in the survey was followed by questions that opened up the possibility of these language professionals providing a more positive view of NNS-produced English. The results for the question about whether the respondent had a preference to translate or interpret source texts/talks by NS or NNS speakers are presented in Table 10. The majority response for each group was NS-produced source texts but, although very few actually preferred source texts produced by NNSs, a substantial proportion of each group said that they had no preference.

There might be several reasons for why many in each group indicated no preference, including that at least some source texts produced by NNSs might be easier to work with than those by NSs. In answer to the question of how NNS-produced texts/talks might be easier, the most frequent reason chosen by all groups was ‘Simpler sentence structures’ (see Table 11) and even much higher than the option ‘Not easier at all’. About half of each group of interpreters also chose ‘Lower information density’ and ‘Slower delivery’ as advantages of dealing with NNS-produced talks. While this account indicates that these language mediators had a more differentiated view of source texts than a deficit-oriented view would suggest, the preference for NS-produced texts still seems to prevail.

Results from voluntary surveys distributed online always have to be interpreted with caution because the respondents are self-selected and probably quite highly motivated to provide their views on the topic being examined. Nevertheless, the convincing number of responses to our survey shows that non-native speaker English or ELF is a factor that many interpreters and translators (have to) reckon with. On the basis of the age distribution of the respondents (see Table 2), it can be assumed that most of the practitioners have been in the profession long enough to have observed ELF-related changes and developments. They work in a wide range of professional contexts (see Figure 1) and represent a wide range of different language combinations (see Figure 2). ELF plays a substantial role in their work, with respondents of all groups estimating that over half of the source texts they interpret or translate are produced by non-native speakers (see Table 5). This is a particularly important result for the community interpreters since there has been little consideration to date of ELF in the research literature on community interpreting (e.g., Määttä, 2017).

While it should be noted that most participants say they are rarely provided with information about whether the source text/talk is produced by a non-native speaker (see Table 6), it seems safe to assume that at least the interpreters can make rather clear judgments from the actual communicative situation (e.g., on the basis of NNS accents). Despite some caveats, the careful formulation of the questions and their order, the results still suggest that respondents associated a significantly higher proportion of source text/talk produced by NNS with poor quality (see Section 3.3). In unison, the three participant groups also attributed different features to NNS- versus NS-produced text/talk. For instance, certain features, such as odd word choice, misuse of vocabulary, odd style, and unclear pronoun references were significantly more often selected for source texts produced by NNSs than by NSs.

Similarly, agreement was found in the identification of major difficulties associated with dealing with NNS-produced texts (see Figure 3). Although not all features of NNS-produced text/talk were considered equally problematic by these multilingual professionals, there was a strong degree of correspondence between the features most commonly associated with poor NNS-produced texts (Table 9) and the major difficulties experienced in dealing with these texts (Figure 3). These include misuse of vocabulary, odd words, sentence structures, cohesion, and vagueness and are very much in line with findings from earlier ITELF studies (e.g., Albl-Mikasa, 2018). Finally, a non-preference for NNS-produced source texts was shared among all three groups. While a substantial number of participants had no preference at all, almost half of both interpreter groups and more than half of the translators indicated a preference for NS-produced texts (see Table 10).

Of particular interest are the almost 2,000 open comments on how respondents deal with ELF source input. As described in some detail in Section 3.4, second-level codes, derived from the first-level coding process, were subsumed under 8 broader themes. From the wide diversity of strategies mentioned, most fell under the three broader themes of source text focus, target text focus, and intervention. As regards the most frequently mentioned themes of source and target text focus, making sense of the source text/talk was particularly important for all three groups in dealing with ELF input, as was optimizing and, if necessary, making compromises on the target text/talk. The latter points to professionals’ aspiration to improve on deficient source texts in the target version (see Reithofer, 2013). The systematic coding process described in Section 3.4 revealed some overlap but also substantial differences in the strategies used by conference and community interpreters as well as translators. The community interpreters mentioned intervention as a strategy much more than the other groups did, although asking and referring to the client for clarification was also an oft-cited option for translators. For obvious reasons of the temporal and spatial constraints of producing target talk into a microphone, usually in a booth at some distance from the speaker, this was not the case for the conference interpreters. While self-regulation and preparation strategies were common across all three groups, possibly because these are integral parts of their training, reliance on exo-source text information seems much less relevant for community interpreters. This begs the question as to whether community interpreters lack the research skills that are built up as part of most tertiary interpreter and translator training programs and/or whether they simply do not have equally ready access to documentation, which in sensitive hospital or court settings may indeed be more difficult to obtain.

The survey presented in this paper was initially conceived as a way to gain more information from professional language mediators in order to validate results from cognitive load testing in which interpreters, translators, and other multilinguals performed multilingual tasks in a laboratory and in a simulated workplace setting. Taken together, the findings discussed above and those reported in Gieshoff et al. (2023) and Boos et al. (2022) support the assumption that processing ELF input requires more effort for non-native speakers than processing standard English input does. However, professional language mediators seem to have developed useful strategies that help them cope with the challenge of producing high-quality target text output in another language from sometimes rather poor-quality ELF input. Rather than having to acquire such strategies from possibly frustrating and negative experiences, these could be presented to aspiring language professionals in the form of targeted training to work with ELF input (e.g., Albl-Mikasa, 2013; Galloway, 2018), similar to the recognition that language competence includes being able to deal with accented speech and linguistic varieties (e.g., CEFR, 2020). Testing the effectiveness of such educational intervention deserves further study.

The results of the present study also have implications for non- professional language mediators who perform translation and interpreting tasks as part of their main role within an organization (see Piekkari et al., 2020). Preparation, concentrating on the message, and asking for intervention are all useful strategies for anyone interacting with non-native speakers of the language being used for communication. The strategies that the language mediators participating in our survey use for dealing with ELF input are not specific to English so should be able to be extended to any language being used as a lingua franca. This would be another important avenue to explore within sociolinguistic and/or international organizational studies.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

MA-M: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. ME-D: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration. ACG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AHH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The project was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, SNSF, Sinergia grant CRSII5_173694.

We would like to express our appreciation to all the language professionals who took the time to complete our survey. In addition, our thanks go to Maura Calzado, Natalie Dietrich, Romina Schaub-Torsello, and Romy Thommen for testing the survey before its dissemination as well as Raphael Dubler for implementing it in REDCap.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1413110/full#supplementary-material

1. ^https://www.zhaw.ch/en/research/research-database/project-detailview/projektid/2039/

2. ^https://projectredcap.org/about/

3. ^The global COVID-19 pandemic was still raging while the survey was open, which may or may not have affected the reach and response rate.

4. ^No information was gathered about the geographical location of the participants or the location of the markets they are active in, since this was not the focus of the study.

5. ^Additional options were: male, nonbinary, prefer not to specify.

6. ^Chi-square tests were not used for this frequency data because one of the assumptions was violated (i.e., the expected value in some cells was 0).

7. ^The focus of this article is on the quantitative findings, but a publication of the detailed qualitative analyses of the coping strategies is planned.

Albl-Mikasa, M. (2010). Global English and English as a lingua franca (ELF). Implications for the interpreting profession. Trans-kom 3, 126–148. doi: 10.21256/zhaw-4080

Albl-Mikasa, M. (2013). Teaching Globish? The need for an ELF-pedagogy in interpreter training. Int. J. Inter. Educ. 5, 3–16. doi: 10.21256/zhaw-4072

Albl-Mikasa, M. (2018). “ELF and translation/interpreting” in The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua Franca. eds. J. Jenkins, W. Baker, and M. Dewey (London: Routledge), 369–383.

Albl-Mikasa, M. (2022). “Conference interpreting and English as a lingua franca ”, in The Routledge Handbook of Conference Interpreting, eds M. Albl-Mikasa and E. Tiselius (London: Routledge), 546–563.

Albl-Mikasa, M., Ehrensberger-Dow, M., Hunziker Heeb, A., Lehr, C., Boos, M., Kobi, M., et al. (2020). Cognitive load in relation to non-standard language input: insights from translation, interpreting and neuropsychology. Trans. Cog. Behav. 3, 263–286. doi: 10.1075/tcb.00044.alb

Albl-Mikasa, M., and Gieshoff, A. C. (2024). “Non-standard input in interpreting (research)” in The Routledge handbook of interpreting and cognition. ed. C. D. Mellinger (New York: Routledge), 204–223. doi: 10.4324/9780429297533-16

Albl-Mikasa, M., Gieshoff, A. C., Ehrensberger-Dow, M., Hunziker Heeb, A., Dietrich, N., Thommen, R., et al. (2024). Survey questionnaire on “English as a lingua franca in interpreting and translation” for the project “cognitive load in interpreting and translation (CLINT)” (v1.0). Zenodo. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.11796196

Bendazzoli, C. (2020). Translators and interpreters’ voice on the spread of English as a lingua franca in Italy. JELF 9, 239–264. doi: 10.1515/jelf-2020-2040

Boos, M., Kobi, M., Elmer, S., and Jäncke, L. (2022). The influence of experience on cognitive load during simultaneous interpretation. Brain Lang. 234:105185. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2022.105185

CEFR (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Chang, C., and Wu, M. (2014). Non-native English at international conferences: perspectives from Chinese–English conference interpreters in Taiwan. Interpreting 16, 169–190. doi: 10.1075/intp.16.2.02cha

Cogo, A. (2018). “ELF and multilingualism” in The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua Franca. eds. J. Jenkins, W. Baker, and M. Dewey (London: Routledge), 357–368.

Cogo, A., and House, J. (2018). “The pragmatics of ELF” in The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua Franca. eds. J. Jenkins, W. Baker, and M. Dewey (London: Routledge), 210–223.

Ehrensberger-Dow, M., Hunziker Heeb, A., Massey, G., Meidert, U., Neumann, S., and Becker, H. (2016). An international survey of the ergonomics of professional translation. ILCEA Revue de l’Institut Des Langues et Cultures d’Europe, Amérique, Afrique, Asie et Australie 27. doi: 10.4000/ilcea.4004

Firth, A. (1996). The discursive accomplishment of normality: on ‘lingua franca’ English and conversation analysis. J. Pragmat. 26, 237–259. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(96)00014-8

Galloway, N. (2018). “ELF and ELF teaching materials” in The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua Franca. eds. J. Jenkins, W. Baker, and M. Dewey (London: Routledge), 468–480.

Gieshoff, A.C., Albl-Mikasa, M., and Hunziker Heeb, A. (2023). “Effects of non-native text input on performance and perceived comprehensibility in translation, interpreting and other language processing tasks”, in ICTIC 4 Abstract Book. Fourth International Conference on Translation, Interpreting, and Cognition (ICTIC 4), Santiago de Chile, Chile, 5–9 September 2023.

Hall, C. J. (2018). “Cognitive perspectives on English as a lingua franca” in The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua Franca. eds. J. Jenkins, W. Baker, and M. Dewey (London: Routledge), 74–84.

House, J. (2013). English as a lingua franca and translation. Interpret. Transl. Train. 7, 279–298. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2013.10798855

Jenkins, J. (2007). English as a lingua Franca: Attitude and identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, J., Cogo, A., and Dewey, M. (2011). Review of developments in research into English as a lingua franca. Language teaching. Surv. Stud. 44, 281–315. doi: 10.1017/S0261444811000115

Kurz, I., and Basel, E. (2009). The impact of non-native English on information transfer in SI. Int.J. Interp. Trans. 7, 187–212. doi: 10.1075/forum.7.2.08kur

Määttä, S. (2017). English as a lingua Franca in telephone interpreting: representations and linguistic justice. Interp. Newsletter 22, 39–56. doi: 10.13137/2421-714X/20737

Mauranen, A. (2013) in “Lingua franca discourse in academic contexts: Shaped by complexity”, discourse in context: Contemporary applied linguistics. ed. J. Flowerdew, vol. 3 (London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic), 225–245.

Piekkari, R., Tietze, S., and Koskinen, K. (2020). Metaphorical and interlingual translation in moving organisational practices across languages. Organ. Stud. 41, 1311–1332. doi: 10.1177/0170840619885415

Reithofer, K. (2010). English as a lingua franca vs. interpreting – battleground or peaceful co-existence. Interp. Newsletter 15, 143–157.

Reithofer, K. (2013). Comparing modes of communication: the effect of English as a lingua franca vs. interpreting. Interpreting 15, 48–73. doi: 10.1075/intp.15.1.03rei

Rodríguez Melchor, M.D., and Walsh, A.S. (2020). What does ELF mean for the simultaneous interpreter? An overview of current situation of the Spanish interpreting market. In English as a lingua Franca and Translation & interpreting. Special issue of JELF 9, eds M. Albl-Mikasa and J. House, 265–286. doi: 10.1515/jelf-2020-2041

Saldanha, G., and O’Brien, S. (2013). Research methodologies in translation studies. Abingdon: Routledge.

Keywords: ELF, English as a lingua franca, conference interpreters, community interpreters, translators, language mediation, strategies

Citation: Albl-Mikasa M, Ehrensberger-Dow M, Gieshoff AC and Hunziker Heeb A (2024) English as a lingua franca in interpreting and translation: a survey of practitioners. Front. Commun. 9:1413110. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1413110

Received: 06 April 2024; Accepted: 26 June 2024;

Published: 09 July 2024.

Edited by:

Soumia Bardhan, University of Colorado, United StatesReviewed by:

Xiangdong Li, Xi’an International Studies University, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Albl-Mikasa, Ehrensberger-Dow, Gieshoff and Hunziker Heeb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michaela Albl-Mikasa, bWljaGFlbGEuYWxibC1taWthc2FAemhhdy5jaA==; YWxibC1taWthc2FAdC1vbmxpbmUuZGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.