- Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

Promoting the construction of Internet democratic politics in China requires an understanding of how multimodal connectedness can enhance citizens’ political participation. This study introduces the Orientations-Stimuli-Reasoning-Orientations-Responses (O-S-R-O-R) model, explaining the pathway from multimodal connectedness to political participation through “multimodal connectedness—political news attention/political news use—interpersonal political discussion—political trust—political participation.” Analyzing data from 2,379 participants in the context of Internet democratic politics, the study finds that the mediating variables fully mediate the relationship between multimodal connectedness and political participation. While political news attention promotes political participation, political trust has a significant negative impact. The study also compares the model across three age groups: young (18–29 years), middle-aged (30–39 years), and elderly (40–60 years). For the young and middle-aged groups, political news attention negatively impacts political participation, likely due to the fragmentation and distraction caused by real-time messages. Among the elderly, political trust negatively affects political participation, indicating a complex scenario where they are passionate about politics but lack adequate participation channels.

Introduction

The prosperity of the Internet has changed the citizens’ political participation habits. How to use new media to encourage citizens’ political participation to establish an efficient communication mechanism between the government and the people and how to promote the construction of Internet democratic politics in China have always been the focus of academic research. The formation of such research focus is due to the rapid development of multimodal media technology, which enables citizens to use media selectively to understand political knowledge, observe political activities, internalize political beliefs (Zhang, 2014), then participate in political activities, and engage in political discussions and expressions. Political participation was mainly mobilized participation in China and then gradually showed more diverse political participation (Zeng, 2014). This process has shaped new forms of citizens’ political participation, making research in this field an important cornerstone for guiding media integration and publicity in the Internet era.

However, the present research studies follow the traditional dualistic research perspective, which lacks consideration of the Chinese characteristic of democratic political participation and does not establish a coherent frame between multimodal connectedness and political participation. The study utilizes the O-S-R-O-R model, which was developed to explain the mediating role of political discussion and political attitudes (Shah et al., 2007), a well-established integrative framework that details the process of multimodal connectedness effect.

In addition to the application of the O-S-R-O-R model, this study also pays attention to the characteristics of populations. In many research studies on the factors influencing political participation, the sample populations are subjected to additional restrictions, such as age, sex, and urban or rural area (Xiao and Wang, 2012; Qiu et al., 2014; Jin and Nie, 2017; Huang, 2018). Based on this classification, researchers conduct descriptions of certain groups or make comparisons. These studies reveal the differences due to various combinations of classification restrictions. For example, a study of the factors influencing the political trust of the young middle class in China found that the political trust of the young middle class is no longer influenced by factors of material level, such as performance evaluation; it is more likely to be dominated by multiple social interests and government’s action on the related heated issue (Peng, 2016). Therefore, it is necessary to study different groups such as groups of different ages and explore the relationship between the technical background of multimodal connectedness and their political participation behavior.

In today’s digital society, communication has added many new forms, such as social media, online platforms, and live streaming. These diversified platforms present political messages through diverse multimedia formats, enhancing the information to be more engaging and easily consumable (Wolfsfeld, 2022), significantly influencing citizen’s political participation. Although it is generally accepted that the use of multimodal connectedness has some influence on users’ daily lives, how does the chain reaction happen between media and behavior? What are the specific mechanisms through which it is formed? Studies focusing on the specific behavior of civic political participation are worth exploring in China. This study combined the previous literature and related research and integrated it into a cohesive model, from the perspective of communication to make up for some of the gaps in the previous research.

Therefore, based on the life span perspective, this study aims to compare and explore the possible mediating factors between multimodal connectedness and political participation in the O-S-R-O-R model among different age groups. This study also tries to integrate the research tradition ignored in the two previous models: the influence of multimodal connectedness habits on behavior and the individual reaction difference due to their internalization process related to multimodal connectedness. In addition, this study can also test the applicability of the O-S-R-O-R model in the context of Chinese culture.

Literature review

Multimodal connectedness and political participation

Media use has been regarded as an important variable influencing political participation in many studies of different cultural backgrounds. The research on the relationship between media use and political participation focused on measuring media use for diverse political participation (Bimber et al., 2015; Halim et al., 2021) and the impact of online (Waeterloos et al., 2021) and offline channels (Pinkleton et al., 1998) on political participation. The use of multimodal media use or multimodal connectedness is based on the definition by Schroeder (2010): “the various modalities through which people maintain their connections with each other,” manifesting the fact that individual actors have a repertoire of communication channels (i.e., text, voice, and images) for social interaction. Since the invention of the Internet, multimodal connectedness has become an integral part of our daily lives, with exponential increases in speed and connectivity (Rainie and Wellman, 2012). At the same time, multimodal connectedness offers different interests and gratifications to the audience (Blumler and Katz, 1974). For example, in the comparison between text-based long messages and short messages, researchers found that long messages sent by e-mail and short messages sent by chat software were the most popular ones (Church and De Oliveira, 2013). In the study of human–computer interaction (Norman, 1999), these “operability” concepts are also attributed to “affordances” (Gibson, 1977), such as visually adding the users’ content generation interface and application interface. We can find that to convey intended messages, multiple forms have become daily parts of citizens’ lives. Therefore, the reality of citizens’ media use habits includes multimodal connectedness, allowing them to meet their common political participation needs through various media channels.

However, despite this social reality, the current research on media use and political participation has not paid systematic attention to multimodal media use or multimodal connectedness. Most media use studies of political participation have focused on specific apps (Lu, 2016), comparison of new media versus traditional media (Zhang, 2017), and social media (Nabi et al., 2013; Wang, 2017), such as the online social platform: Twitter and Facebook (Valenzuela et al., 2020) and even particularly mobile phones (Hall and Baym, 2012). Although these studies provide ideas and paradigms for the study of multimodal connectedness, they still ignore the influence of the integrity of the communication system and the comprehensiveness of media use on political participation. Only a small number of researchers mentioned the importance of multimodal media. For example, a study based on the selection of multiple online news platforms measured the online political expression of youth on customized media platforms, official media, and social media and pointed out that in such a new Internet environment, the diversification of media platform selection will interact with users’ media practice, thus shaping a new overall picture of online political expression (Yan, 2020). Moreover, a study has found that multimodal connectedness affects political participation directly and indirectly through interpersonal discussion, political knowledge, and political efficacy (Chen, 2021). Thus, the use of multimodal connectedness cannot only objectively construct the picture of political participation in the new media landscape but also shape the practical relationship between individuals, media, and political participation under the new media ecological environment. Multimodal connectedness, based on this media ecology and media use patterns, should be considered when we study media and political participation.

O-S-R-O-R model (orientations-stimuli-reasoning-orientations-responses model)

Research on multimodal connectedness has examined the influence on political participation from many aspects, but the possible mechanism to explain the key variables is still lacking. At present, social capital is used as an intermediary variable (Zeng, 2014; Chan, 2018) to study the influence of media use on political participation, and the following research added variables, such as political knowledge (Alami, 2017), political discussion (Chan et al., 2017), political learning (Ida et al., 2020), and political efficacy (Bruce, 2018). These key variables are important for exploring possible internal mechanisms. However, how to understand the relationships between these key variables and how to test the mediating effect of these key variables with a robust mediation model are still an urgent issue. Therefore, this study integrates these key variables into political news uses, political news attention, interpersonal political discussion, and political trust. By applying the O-S-R-O-R model and introducing mediating variables, this study attempts to explain the influence of multimodal connectedness on political participation from a more systematic perspective.

The O-S-R-O-R model was first established in the framework of the O-S-O-R model (Markus and Zajonc, 1985). In this paradigm, several truncated models emerged. These models included the Campaign Communication Mediation Model (McLeod et al., 2001), Cognitive Mediated Model (Eveland et al., 2003), and Citizen Communication Mediation Model (Shah et al., 2005), demonstrating and examining different social structures, cultures, and motivational factors (McLeod et al., 1999) that influence political participation by influencing communication (Shah et al., 2005). In the basic O-S-O-R model, the first “O” refers to the set of characteristics that the audience gives to the social structure, culture, cognition, and motivation inherent in the given situation; the “S” refers to the influence of these characteristics on the reception of information or stimuli; the second “O” refers to what is likely to happen between the reception of the information and the subsequent reaction; and “R” refers to reaction and action (McLeod et al., 1994). The initial orientations (O) is an important variable selection framework, which can stimulate (S) and affect other subsequent orientations (O) and reaction behavior (R), but it does not show a coherent chain of cause and effect. It does not adequately capture the mediation process of the mutual concepts presented in these models (Shah et al., 2007). For example, in the cognitive mediation model, the researchers identified two pathways for individual knowledge acquisition: (1) the direct path from motivation to attention and then to knowledge and (2) the indirect path mediated by elaboration of the news (Eveland, 2001). The importance of motivation toward individual cognition and the audience’s motivation in the process of knowledge acquisition is emphasized (Ho et al., 2017). The cognition and attitudes generated in the basic process of S-O do not represent the comprehensive sense of stimulation in nowadays media environment but tend to relate the result with the contact with mass media, which should be further explored. These perceptions and attitudes are intermediate between stimuli and oriented results, forming the subsequent understanding and reasoning (R) through the ideas encountered in the information stimuli. Therefore, the researchers add an important variable, “Reasoning,” to this basis, and a new O-S-R-O-R model is constructed to emphasize cognitive and reasoning processes. This process is defined as generalized mental elaboration and collective reasoning (Shah et al., 2007).

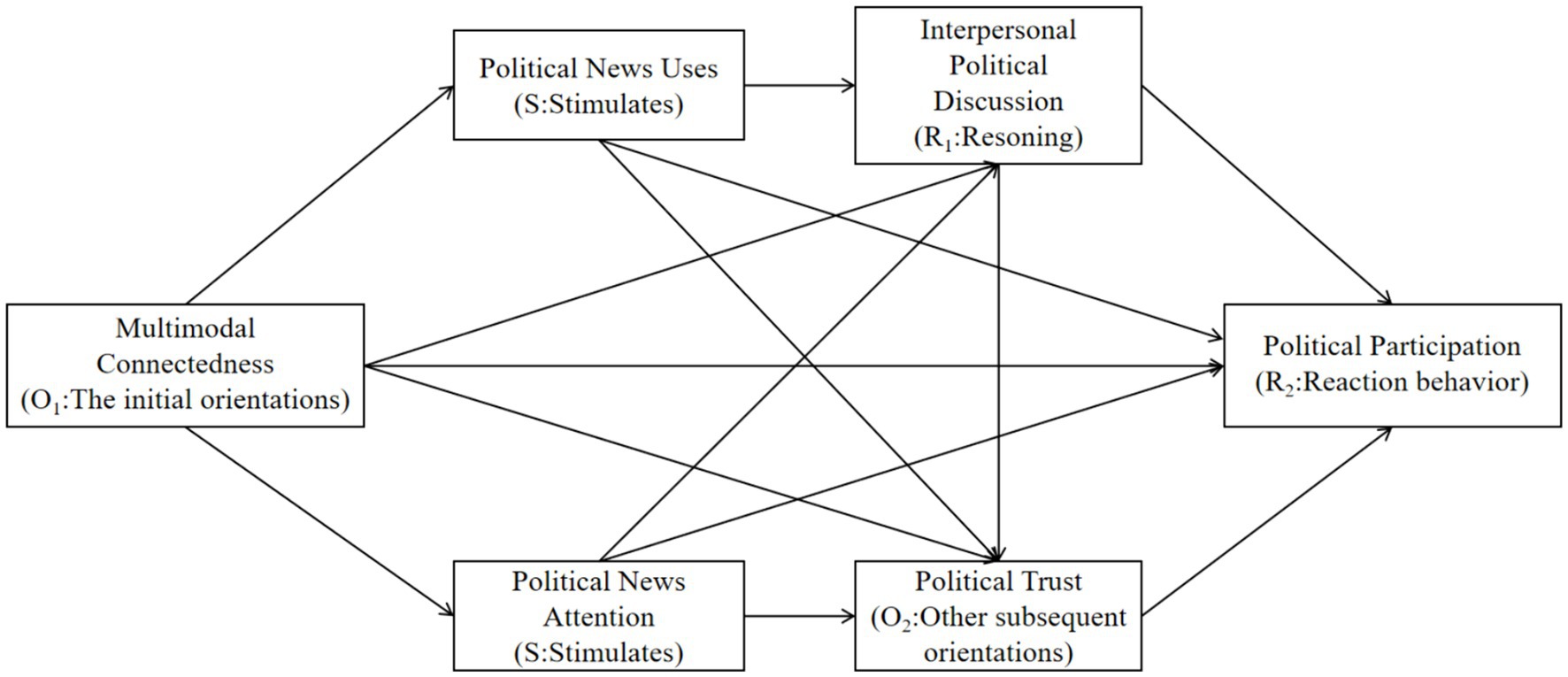

Based on previous studies and the definition of the O-S-R-O-R model, this study defines O1 as multimodal connectedness (multimodal media use, Chan, 2018), O2 as political trust, S as political news uses and political news attention, R1 as interpersonal political discussion, and R2 as political participation, as shown in Figure 1.

Each component of the model is structured as follows:

Multimodal connectedness (O1): The initial orientation of citizens is based on cultural traditions within the framework of society as a whole. It appears in many studies as an existing, persistent, long-term phenomenon or inherent characteristic. For example, McLeod et al. (1999) used demographic variables, community integration, and political interest as the first O to examine the relationship between television news use and local political participation and found no direct link between the two variables, even though interpersonal communication was found to indicate an indirect link in mediating these two variables (McLeod et al., 1999). Based on McLeod’s research, researchers began to pay attention to the important role of media use and took the Internet, especially online news based on this platform, as a research variable, exploring the role of political messages shaped by this platform in the field of public expression and finding that online media can complement the messages of traditional media, thus facilitating political discussion, offering citizens more information, and influencing citizens’ political participation (Shah et al., 2005). The rise of emerging Internet-based social platforms, especially TikTok, not only has the production and consumption of multimodal content been transformed but also has user interactions and cultural practices on the platform (Zulli and Zulli, 2022). The powerful short video and live streaming capabilities of the platform enable political figures and institutions to connect more directly with younger audiences, leveraging the platform’s algorithmic advantages for targeted dissemination. For instance, Cervi (2023) highlights TikTok’s significant role in local elections. It allows candidates to become political influencers, interact directly with voters, and showcase their personalities and policy positions, transforming traditional election communication models. This shift alters the dissemination of political information and impacts public political engagement and perception. In addition, the selective use of multimodal media also reflects the characteristics of citizens’ media literacy (Jiang and Gu, 2022), and the level of media literacy has a positive relationship with political participation; the more media literacy citizens gain, the more they can understand the political, cultural, and social contexts behind media messages, recognize the values and meanings that these messages guide, and thus are more willing and able to practice political participation (Wang, 2017). As a result, not only all citizens are interested in politics or have the literacy to recognize and understand the messages’ information but also everyone will have their own unique multimodal media use pattern and multimodal connectedness because of their inherent culture, value, and meaning orientations.

Political news attention, political news uses (S), and interpersonal political discussion (R1): S is generally regarded as a media variable and R as a behavioral variable in the model (Chan, 2016). This media stimulus can involve a series of dynamic processes: exposure, attention, and priming (Shah et al., 2007), culminating in clarity of thought and individual inner expression, reflection on media content (Mutz, 2006), anticipation of conversation (Eveland et al., 2005), and expression of ideas (Pingree, 2007). Previously, attention-related stimuli were mainly applied to the cognitive mediator model (CMM), influencing the direct path from motivation to knowledge acquisition (Eveland, 2001). A branch of studies has applied it to different media channels and media platforms. For example, some studies have shown a correlation between audiences’ attention to traditional and new media platforms and reflection on their media content, and all media platforms showed a positive correlation with interpersonal discussion as a media channel (Yang et al., 2017). This effect can be extended in the study of the audiences’ attention and the content of different media platforms (Kim, 2016). The investigation of news attention on this basis will increase the sense of political participation and encourage participation in general (Zhou, 2011). At the same time, some psychology effect research indicated that it does not matter whether a person tries to learn, it matters how he or she searches for material in the process of learning, which suggests the transition from cognition to action. In addition to the motivation for the behavior, the process of searching for information is ultimately dominant. The use of political news, including receiving channels and frequency of use, will naturally more or less give the public incentives for political participation. Therefore, in addition to news attention, the real use of political news can also be regarded as an “S” variable. This study emphasizes two mediating variables for the “S” process: political news attention and political news uses. In the selection of the “R1” variable, this study subdivides political discussion into interpersonal political discussion. First of all, interpersonal discussion is the process of evaluating media information and understanding, through which the audience can better understand information and disseminate information (Robinson and Levy, 1986). Katz (1940) also argued in his two-step flow of communication that information flows from the broadcast and print media to opinion leaders and then from opinion leaders to less active groups. Second, in several recent empirical studies, the relationship between media attention and interpersonal discussion is positively correlated (Lee et al., 2016; Kwon et al., 2021) and strongly correlated in individual social networks (Morgan, 2009; Zou et al., 2021). From the perspective of interpersonal discussion, it can be better explained that political discussion is an important part of interpersonal communication. In this process, people can learn about the knowledge and ideas of others and think collectively (Cho et al., 2009), and via engaging in this dialogue, individuals are provided with an opportunity to organize and articulate ideas coherently (Eveland, 2004).

Political trust (O2) and political participation (R2): The second O and R both extend the meaning of the previous O-S-O-R model: what is likely to happen between the receiving of information and subsequent behavior (Responses) (McLeod et al., 1994). Political trust, unlike variables such as political knowledge, political interest, and political efficacy having positive impacts on media use that is consistent with civic political participation (Bimber et al., 2015), includes different forms of trust, such as media trust and interpersonal trust (Wang, 2013). Political trust is a mixed term showing diverse effects: On the one hand, it represents the influence of political socialization on citizens; on the other hand, it is the guarantee of the establishment of government institutions and the legitimacy of governance (Mishler and Rose, 2001). Thus, the direct impact of political trust on political participation is widely debated. Some studies initially suggested that reduced voter turn as a result of trust loss (Verba et al., 1971), while other studies found that political distrust motivated people to engage in political activities, such as demonstrations, marches, and petitions (Levi and Stoker, 2000). According to the current research in Chinese literature, citizens have high political trust; meanwhile, there is only a weak correlation with political participation (Hu, 2010).

Therefore, to study political trust, we must put it in the whole social environment and explore the paths systematically with other relevant variables. For example, Zhang (2014) found that media use has a positive effect on political trust and through social capital as mediation. Based on the above model, political trust can be connected with political participation in many ways, such as multimodal connectedness—political trust—political participation and interpersonal political discussion—political trust—political participation, which reveals a more comprehensive form of connection exceeding a single connected path. In this study, political participation includes online political participation and offline political participation.

To sum up, this study proposes a systematic approach to the research question, including assumptions about each group of direct and indirect relationships.

Research Question 1: In the relationship between multimodal connectedness (O1) and political participation (R2), what effect do political news attention (S), political news uses (S), interpersonal political discussion (R1) and political trust (O2) have?

Multimodal connectedness and political participation from the perspective of lifespan

To test the relationship between multimodal connectedness (multimodal media use) and political participation and ensure the results are more empirical, this study aims to introduce the life span perspective and divide the population into different age groups. Therefore, the common and different paths and coefficients of connection among different age groups could be studied in detail. Life span theory has been used to study how “Social Change Changes People’s lives” (Elder, 1994) using longitudinal data to study the impact of decisions and actions people made at different points in life on their subsequent lives. Examples include whether to take safety precautions after having sex for the first time, whether to become pregnant, whether to have children, and whether to get married as a result of a series of life-changing events (Elder, 1998). For citizens who have gone through different social stages, the use of various media will inevitably be affected by a series of factors, such as the young, middle, and old stages of life, and this tendency will also affect the way and frequency of political participation more or less. As Paul Learfield found in a large field study of Erie County, there were more older citizens showing a higher level of interest in the election than younger citizens with the same educational background, and this interest and tendency to vote can then spread based on the intimate context of the family, thus influencing young generations who were not interested in the election. In addition, researchers have found that Internet media use declines with age, while teenagers form the majority of active users of social networking sites (Lenhart et al., 2010). Moreover, this age-based use pattern and repertoire have a significant impact on citizens’ political reception and political interest, and thus on political participation (Holt et al., 2013). As observed, age is an important variable that shapes citizens’ multimodal connectedness and has an indirect impact on political participation. Based on the above research, this study raises the following question:

Research Question 2: How does the hypothetical model in Research Question 1 differ among different age groups?

Method

Sampling

The data are from an open-source national survey in China targeted at Internet users. The survey started in 2012, and to date, more than 10 large-scale surveys have been conducted. In the 2017 survey, a total of 2,379 samples were collected, mainly from users of a Chinese website that offers a questionnaire distribution service and has a national sampling database. Among the whole sample, there were 51.2% males and 48.8% females. Moreover, the effective percentage by age group was 18–24 years (24.2%), 25–29 years old (19.8%), 30–34 years old (14.7%), 35–39 years (13.5%), 40–44 years (12.6%), 45–49 years (8.4%), 50–54 years (3.7%), 55–59 years (1.5%), and older than 60 years (1.7%). <It includes mainly young people and middle-aged respondents due to the landscape of Internet users. Based on the data, the sample can be divided by age into three groups: 18–29 years old (N = 1,046), 30–39 years old (N = 669), and over 40 years old and above (N = 664).

Measures

Independent variables

Tables 1–3 summarize the independent and intermediate variables and their descriptive data. In response to the question about media uses, respondents selected the media they were using. When they choose one particular medium, the score of multimodal connectedness would count “1”; otherwise, it will count “0.” The sum of this score indicates different levels of multimodal connectedness. Among the media channels, there are platforms such as “Sina, Tencent, and other business portals,” and “WeChat Circle of friends, QQ groups, and other circles of acquaintances.” It indicates that today no matter whether young or old, citizens are increasingly using online platforms to find information and integrate real-world social networks with the Internet.

Dependent variables

For political participation as a dependent variable, this study used the 1–4 Likert scale: “1” = never participated and “4” = frequently participated. Participation activities included (1) chatting with friends or holding seminars offline; (2) posting comments on the Internet; (3) writing articles and submitting them to the media; (4) speaking on one’s own micro-blog, WeChat, or blog; (5) participating in the discussion of Internet QQ group and WeChat group; (6) communicating privately through e-mail and chat tools; (7) expressing oneself through taking part in practical actions such as parades, demonstrations, letters and visits, petitioning, and voting (M = 2.13, SD = 0.66, alpha = 0.86). The answers were summed up and then divided by 7.

Intermediate variables

Political news use (S) was measured by the average score of the frequency of citizens’ use of different channels to get political news and comments. Political news attention (S) was measured by the scaled answers to the question “In general, are you interested in current political information?” Interpersonal political discussion (R1) was measured by the question “Do you often discuss domestic and foreign political, economic, and social issues with others?” The measurement of political trust (O2) listed several political organizations and groups to test citizen’s trust toward them and finally get an average score.

Results

Descriptive statistics

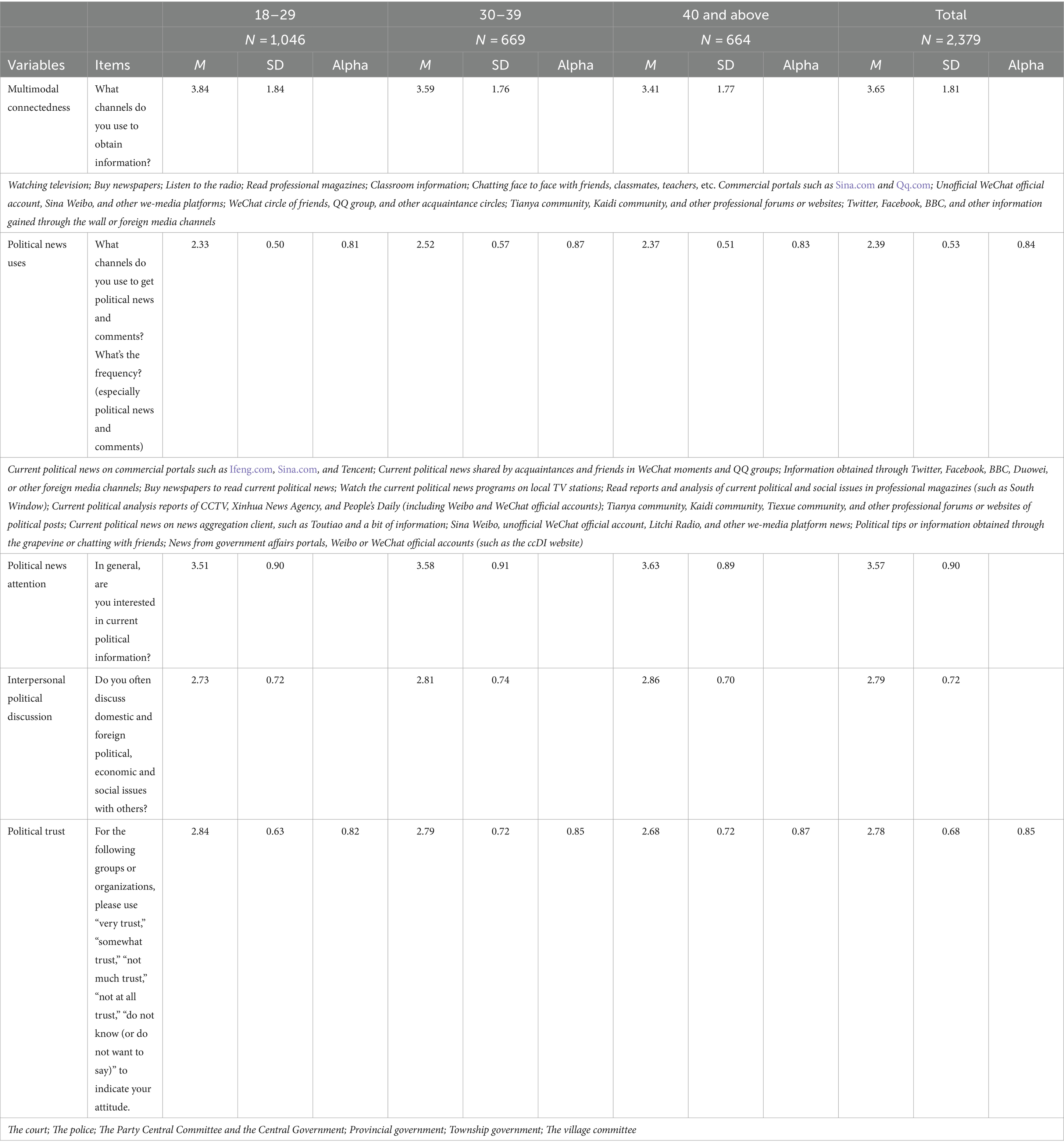

As shown in Table 1, both the capacity and the demand for multimodal connectedness decline with age. The 18- to 29-year-old groups are more pronounced than the remaining two age groups. It is consistent with the age and technical acceptability perspectives. In the use of political news, there is almost no difference between the age groups of 18- to 29-year-old and older than 40 years, while the use of political news of the 30- to 39-year-old group is obviously higher. Moreover, the attention of political news is the highest for the group of 40-year-old and above. One possible explanation is that age may be negatively correlated with information-searching ability under certain circumstances. The result of interpersonal political discussions is consistent with political news attention: It increases as people get older, and there may be a significant positive link between the two variables. In the case of political trust, the result is opposite to interpersonal political discussion and political news attention. The younger the group is, the higher the political trust is; on the contrary, the older the group, the more they are likely to follow the political news and have interpersonal political discussions, with lower political trust.

According to the observation of the whole sample, the total score of multimodal connectedness is 11 and the average is 3.65, which indicates that the media use of the respondents’ group is extremely biased, and they tend to vary by age group. Combined with observation of other variables: political news uses with a mean score of 2.39 out of 4, political news attention with a mean score of 3.57 out of 5, and interpersonal political discussion with a mean score of 2.79 out of 4, in general, the respondents are more concerned about the current political information. Overall, the political trust of the whole sample is on considerate high level.

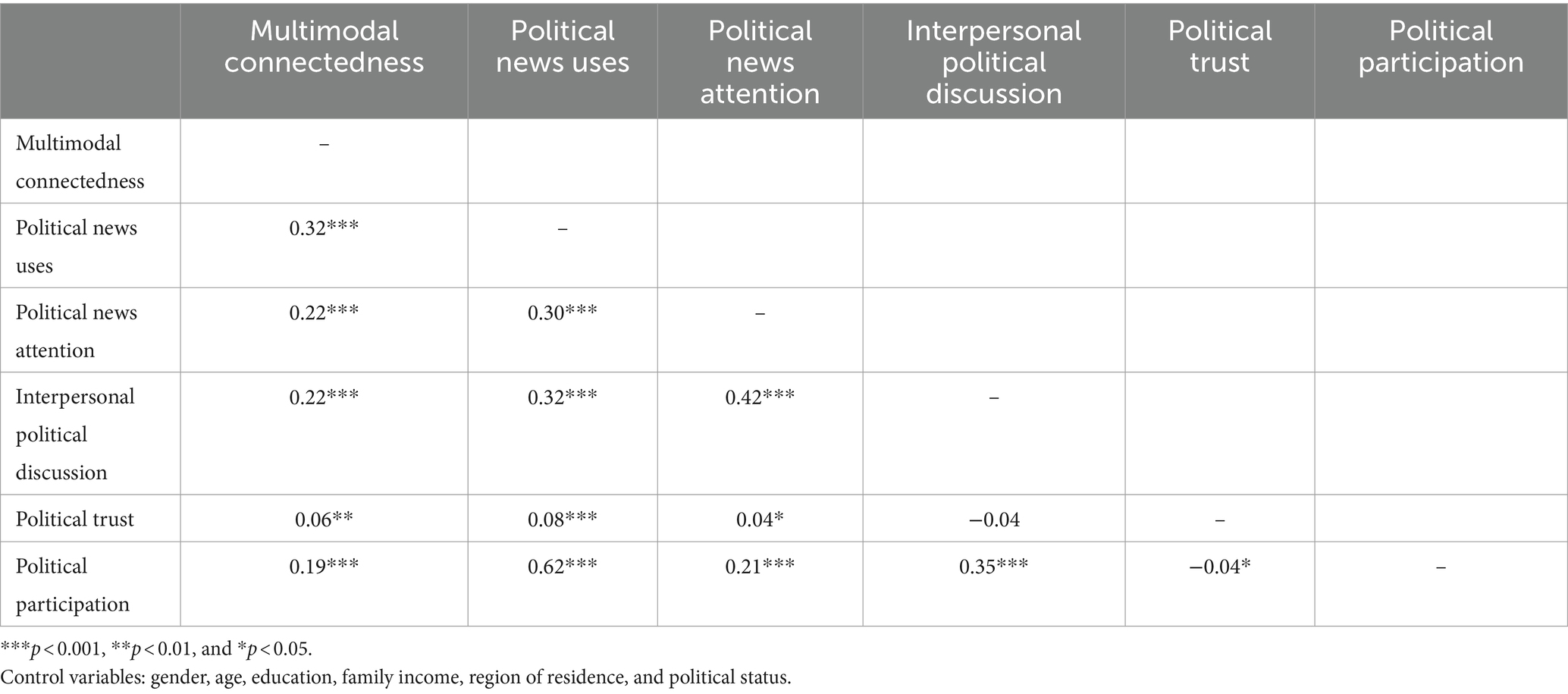

Model testing and revision

To examine the various variables and many paths in this study, structural equation modeling software (AMOS) is used to establish the overall model, and the PROCESS (Model 6) in SPSS is used to evaluate the data to double check the fitness with the proposed theoretical model, especially the direct and indirect influencing paths. To test the above questions, the partial correlation analysis between the key variables was conducted first while controlling the demographic factors, and the results are shown in Table 2. While the relationship between political trust and interpersonal political discussion is not significant, the relationship between political trust and political participation is significantly negative; other variables show significantly positive relationships. Thus, the overall model setting was approximately supported and can be further tested.

The full sample model is then drawn according to the specified path, as shown in Figure 1. Because the model was saturated, the data are presented as X2(0) = 0, p < 0.001, NFI\CFI\IFI = 1, RMSEA = 0.267, and RMR = 0. To further optimize the model fitting, all the non-significant paths (p > 0.05) were removed: multimodal connectedness → political participation; political news attention → political trust. The final revised model is shown in Figure 2 with excellent fitness: X2(2) = 0.761, p < 0.001, CFI/TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, RMR = 0.004.

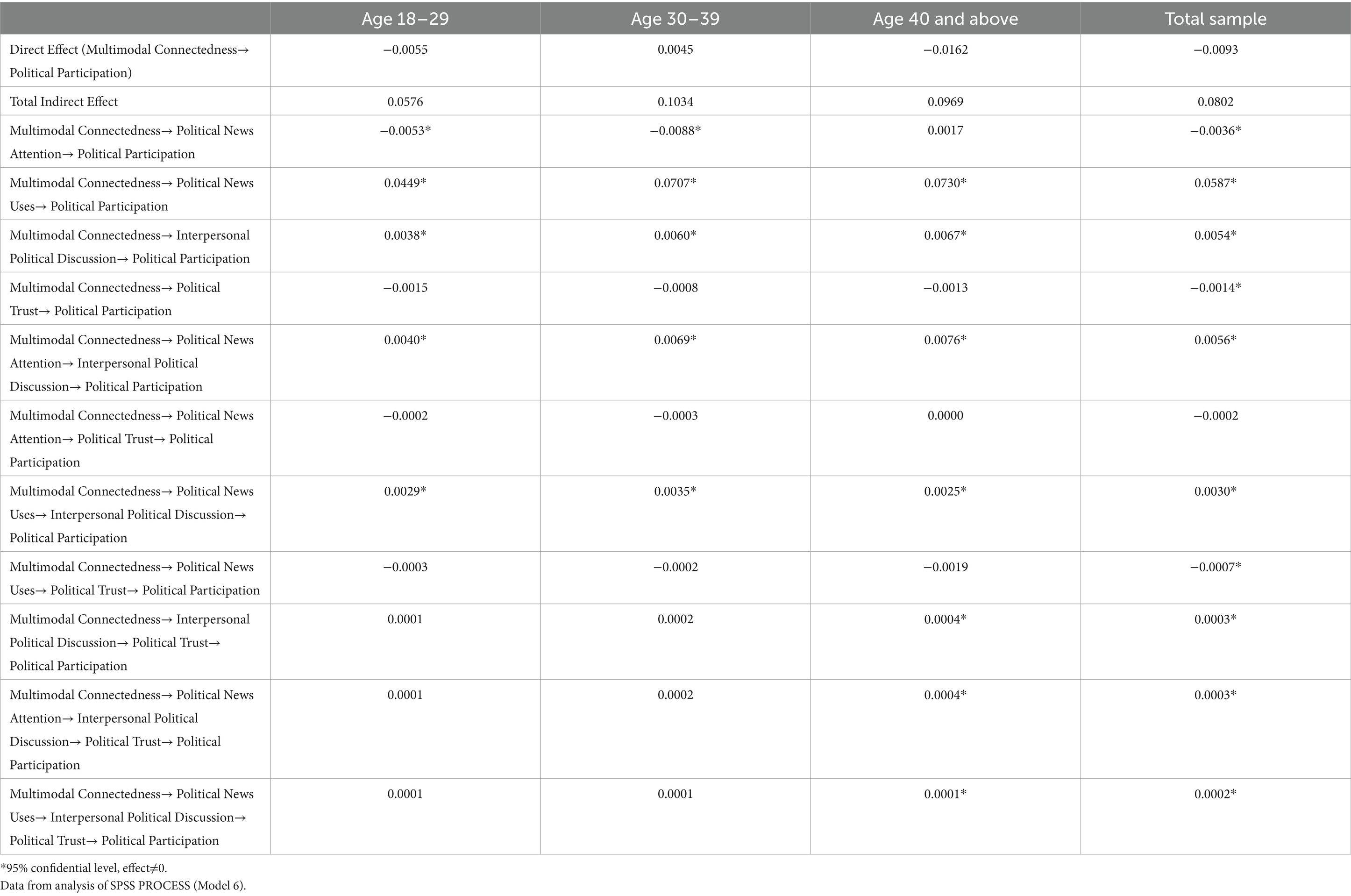

Figure 2 shows all 2,379 samples using a two-side confidence interval and a 95% confidence level, controlling for gender, age, education, family income, region of residence, and political status. As shown in Figure 2, the partial correlation results are similar to those in Table 2, except that the path coefficients of multimodal connectedness toward political participation and political news attention toward political trust are not significant. It shows that all the variables selected by the model have a mediating effect, and the relationship between multimodal connectedness and political participation can indeed be completely mediated by the four sets of mediating variables proposed by the model. As observed from the direct effect in the graph, political news attention is negatively correlated with political participation, and political trust is negatively correlated with political participation, that is, in the use of multimodal media, the more attention to political news, the higher the degree of political trust, the less political participation behavior, which is consistent with the above-mentioned part of the literature. There seems no need to draw extra effort to participate. The indirect effect test of Table 3 shows that except for the sequent path of multimodal connectedness → political news attention → political Trust → political participation, other paths in the model are significant.

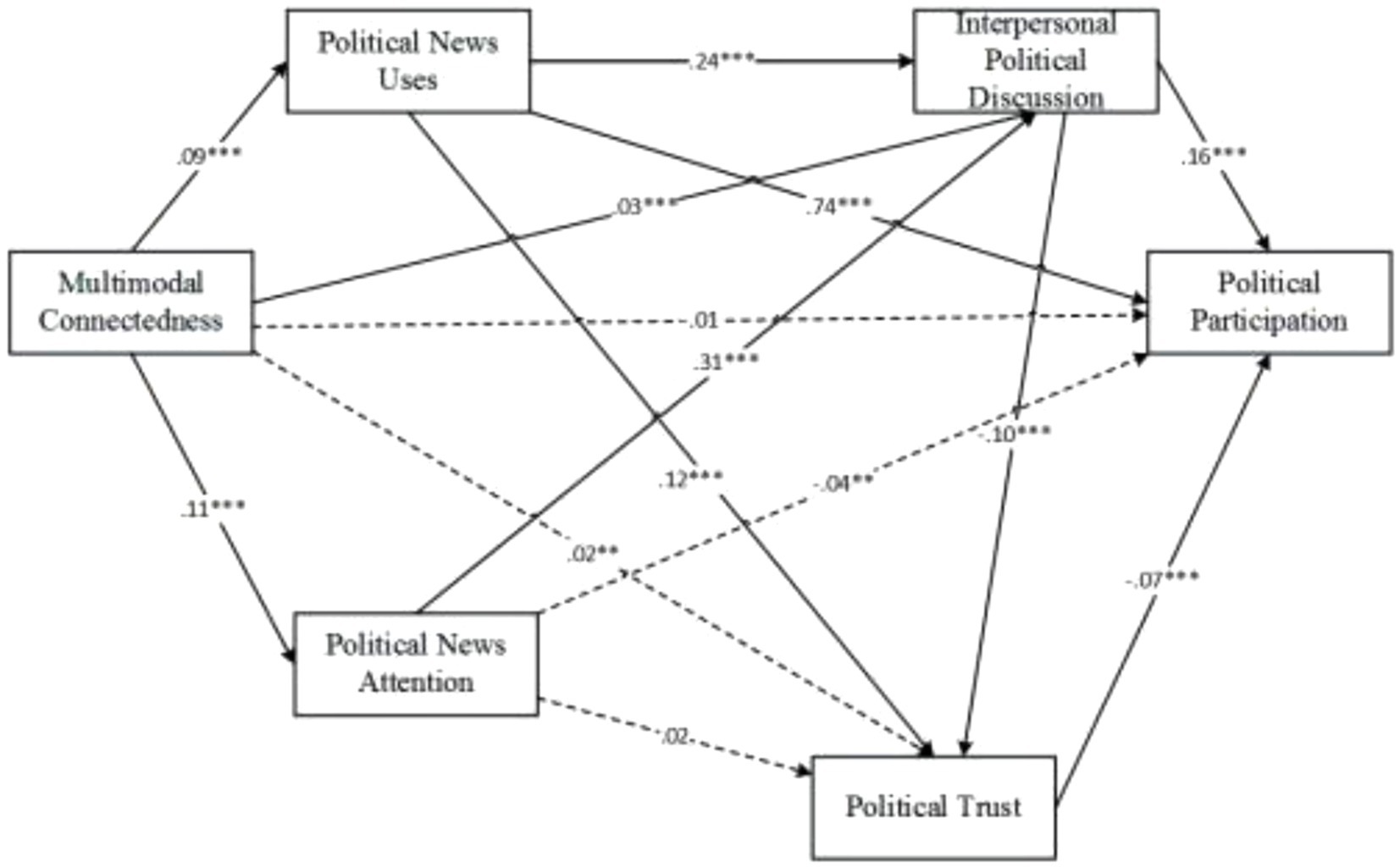

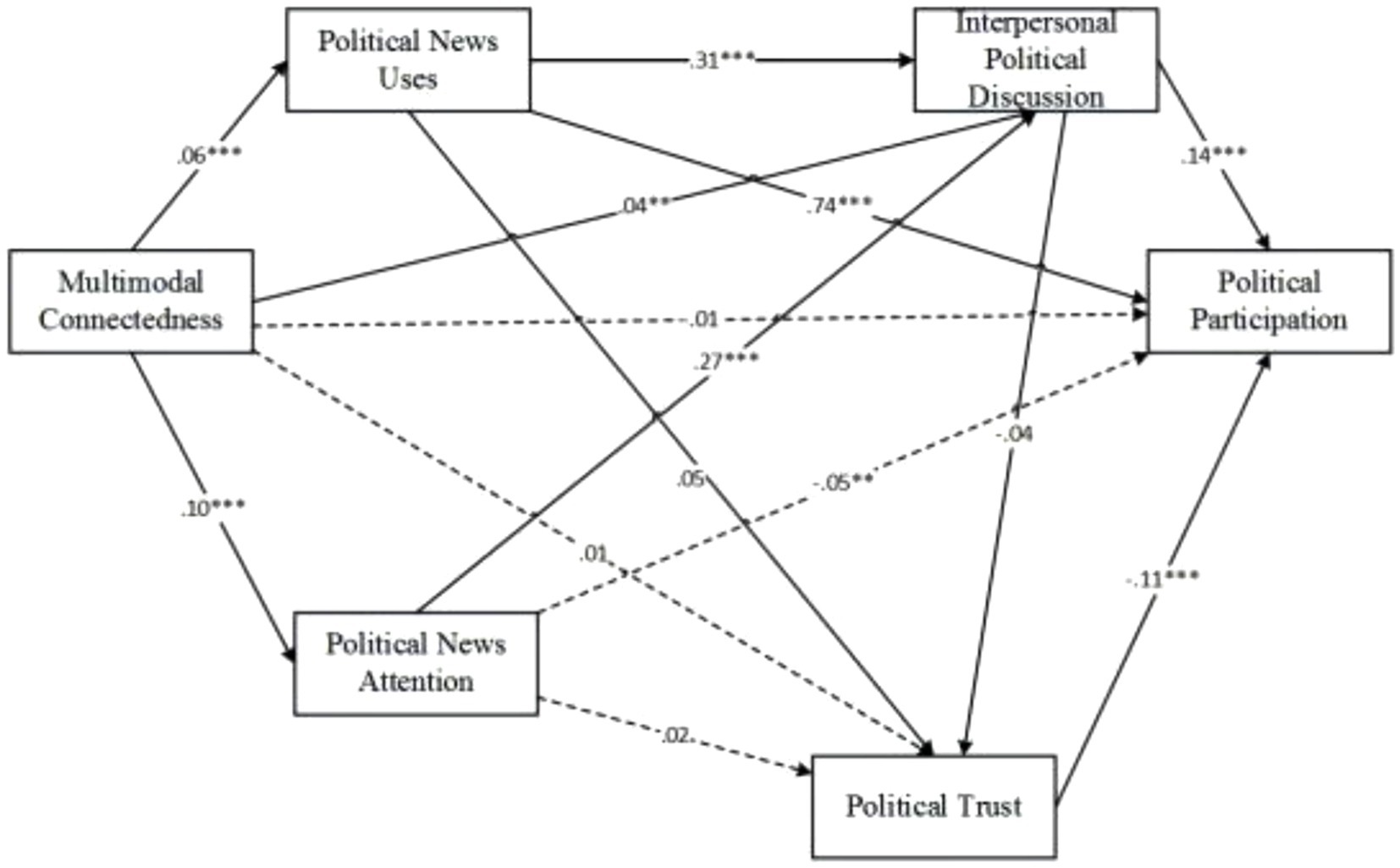

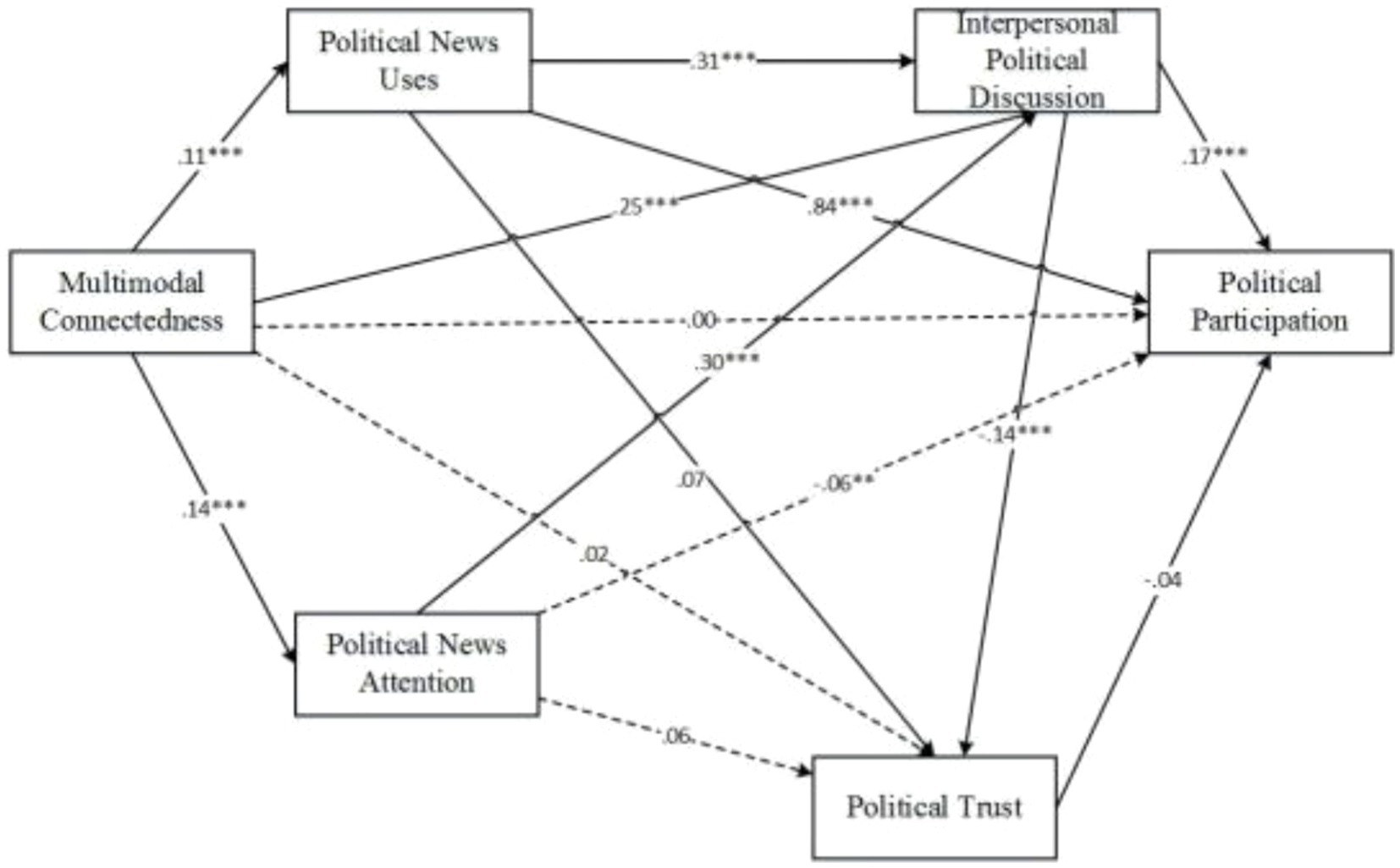

Comparison among age groups

The model testing was carried out for each of the three age groups as for the full sample above. The results are shown in Figures 3–5. Table 3 summarizes the paths and coefficients of the four models from multimodal connectedness to political participation from the PROCCESS analysis. The results show that among 18- to 29-year-old and 30- to 39-year-old groups, five indirect effects are significant: There are three variables mediating the relationship between multimodal connectedness and political participation: political news uses, political news attention, and interpersonal political discussion; other two paths were through political news uses →interpersonal political discussion and through political news attention →interpersonal political discussion. Moreover, the largest indirect effect path is through the political news uses to political participation. In addition, through the political news attention, the path shows a significant negative effect. Among people aged 40 years and above, seven indirect effects are significant, two of which are the relationship between the multimodal connectedness and political participation through political news uses and interpersonal political discussion; two indirect paths are through political news uses or political news attention playing a significant role through interpersonal political discussion; and the remaining three are through political trust. Meanwhile, the path with the largest indirect effect is the same as the above two groups; and the path with the smallest indirect effect is through political news uses →interpersonal political discussion→ political trust. The two paths from interpersonal political discussion to political trust and political trust to political participation are negatively correlated.

On the whole, we can find that political news use is the most significant positive mediation path between multimodal connectedness and political participation. The attention of political news shows the negative influence of multimodal connectedness on political participation in the groups of young people and middle-aged people. In the middle-aged group, the negative effect appears in the two paths of interpersonal political discussion and political trust, which are interpersonal political discussion →political trust, and political trust→political participation. Moreover, political trust became the node with the most significant impact for the age 40 and above group.

Conclusion and discussion

By exploring and extending the relationships between multimodal connectedness and political participation, this study also focuses on the mediation mechanism: political news attention, political news use, interpersonal political discussion, and political trust. This multimodal communication not only has a clear impact on the political practice of citizens but also has a certain advanced impact on the intermediary variables (Research Question 1). The results show that the direct relationship between multimodal connectedness and political participation is not significant when the above-mentioned mediating variables are added; it is further shown that the above-mentioned intermediate variables have important theoretical and practical significance and should be included in future model construction.

This study also discusses the different embodiment of the O-S-R-O-R model in different age ranges from the perspective of the life course; many nuances were observed in the multi-channel political participation of different age groups (Research Question 2). One particular concern is the significant negative impact of political news attention on the political participation of the young and middle-aged (18–39 years old) groups. This suggests that real-time, short-lived, graphic messages are distracting young people from political participation and influencing the formation of political values, a variable that is less pronounced in the older age group (40–60 years and above). In combination with other variables, it is likely to be attributed to the fact that older people are more likely to have sustained, long-term implications for the willingness and manner in which they accepted political participation in a social culture based on kinship and grass-root organization. For example, senior citizens’ associations play an important role in organizing senior citizens to participate in the discussion of important issues in the community and resolving conflicts in villages. In addition, the traditional sense of “nation” still affects the political participation enthusiasm of the elderly. The elderly are supposed to be more willing to participate in a limited time with limited media use platform to gain a national identity or political identity. The “national” identity emphasizes the individual’s identification, maintenance, and love of the community and can function as a process of communication and conflict resolution. Consanguineous identification is the natural foundation of the national identity, and this identification of the nation maintains the tension between private feelings and public values (Zhang, 2018). Moreover, the traditional sense of kinship and political identity with the nation has a profound impact on the willingness of political participation for elder citizens. It is also found that the political trust of the middle-aged and the elderly is an important node in multimodal connectedness and political participation. This could be complemented by the above-mentioned willingness to engage politically. Based on the disconnection of traditional consanguineous culture and the discomfort and spatial displacement brought by the multimedia network era, political trust remains in the traditional family discussion in the offline space but rarely translates into political participation on the network. In addition, self-reinforcement of national identity transforms political trust into a sense of political security, entrusting political participation to trustworthy grass-root authorities.

Influenced by the life span factors in the study, the motivations of individual or group’s multimodal connectedness are differentiated, and different motivations drive individuals or groups to form different political participation practices in the further process of transformation. Evolution, the intersection of knowledge and technology, is the driving force of human existence (Levinson, 2003). If technology is the subject of the times, evolution is the direction of knowledge, and man is the yardstick of media development, with the progress and development of science and technology.

Based on the above research, the technological environment for the use of multimedia does provide a broader channel and platform for citizens’ political participation through the path of “multimodal connectedness—political news attention/political news uses—interpersonal political discussion—political trust—political participation,” a social action network covering the public and private sphere, and connecting online and offline domains was established. The use of multimodal media promotes the change of the identity of political participants, and the people’s expression through the use of multimodal media also promotes the whole process efficiency. It enhances the openness and knowability of democratic political activities. It also makes the construction of network democracy more transparent and convenient. By extending information getting on the Internet, citizens can enjoy the right to know about politics, contributing to the foundation for the following democratic elections, democratic decision-making, democratic management, and democratic supervision of the government and the whole society.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The data are from an open-source national survey in China targeted at Internet users and can be found here: http://www.cnsda.org/index.php?r=projects/view&id=69084413.

Author contributions

LM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LX: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by 2024 Shenzhen Social Sciences Academy Special Research Project “Research on the Practice of Common Prosperity in Spiritual Life Led by Xi Jinping’s Cultural Thought in Shenzhen”. Project Number: 2024AB005.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alami, A. (2017). Social media use and political behavior of Iranian university students as mediated by political knowledge and attitude (Doctoral dissertation, University of Malaya (Malaysia)). Available at: http://studentsrepo.um.edu.my/7512.

Bimber, B., Cunill, M. C., Copeland, L., and Gibson, R. (2015). Digital media and political participation: The moderating role of political interest across acts and overtime. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 33, 21–42. doi: 10.1177/0894439314526559

Blumler, J. G., and Katz, E. (1974). The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research (Vol. 1974): Sage Publications, Inc.

Bruce, J. (2018). College Students’ Dual-Screening, Political Habits and Attitudes: A Survey Analysis. (Master’s thesis, University of the Pacific).

Cervi, L. (2023). TikTok use in municipal elections: from candidate-majors to influencer-politicians. Más Poder Local 53, 8–29. doi: 10.56151/maspoderlocal.175

Chan, M. (2016). Social network sites and political engagement: Exploring the impact of Facebook connections and uses on political protest and participation. Mass Commun Soc. 19, 430–451.

Chan, M. (2018). Digital communications and psychological well-being across the life span: Examining the intervening roles of social capital and civic engagement. Telematics Inform. 35, 1744–1754. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.05.003

Chan, M., Chen, H. T., and Lee, F. L. (2017). Examining the roles of mobile and social media in political participation: A cross-national analysis of three Asian societies using a communication mediation approach. New Media Soc. 19, 2003–2021. doi: 10.1177/1461444816653190

Chen, H.-T. (2021). Second screening and the engaged Publaic: the role of second screening for news and political expression in an O-S-R-O-R model. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 98, 526–546. doi: 10.1177/1077699019866432

Cho, J., Shah, D. V., McLeod, J. M., McLeod, D. M., Scholl, R. M., and Gotlieb, M. R. (2009). Campaigns, reflection, and deliberation: Advancing an OSROR model of communication effects. Commun. Theory 19, 66–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.01333.x

Church, K., and De Oliveira, R. (2013). What’s up with WhatsApp? Comparing mobile instant messaging behaviors with traditional SMS. In Proceedings of the 15th international conference on Human-computer interaction with mobile devices and services (pp. 352–361).

Elder, G. H. Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Soc. Psychol. Q. 57, 4–15. doi: 10.2307/2786971

Elder, G. H. Jr. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Dev. 69, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x

Eveland, W. P. Jr. (2001). The cognitive mediation model of learning from the news: Evidence from nonelection, off-year election, and presidential election contexts. Commun. Res. 28, 571–601. doi: 10.1177/009365001028005001

Eveland, W. P. Jr. (2004). The effect of political discussion in producing informed citizens: The roles of information, motivation, and elaboration. Polit. Commun. 21, 177–193. doi: 10.1080/10584600490443877

Eveland, W. P. Jr., Hayes, A. F., Shah, D. V., and Kwak, N. (2005). Observations on estimation of communication effects on political knowledge and a test of intracommunication mediation. Polit. Commun. 22, 505–509. doi: 10.1080/10584600500311428

Eveland, W. P. Jr., Shah, D. V., and Kwak, N. (2003). Assessing causality in the cognitive mediation model: A panel study of motivations, information processing, and learning during campaign 2000. Commun. Res. 30, 359–386. doi: 10.1177/0093650203253369

Gibson, J. J. (1977). “The theory of affordances” in Perceiving, acting, and knowing. eds. R. Shaw and J. Bransford (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 67–82.

Halim, H., Mohamad, B., Dauda, S. A., Azizan, F. L., and Akanmu, M. D. (2021). Association of online political participation with social media usage, perceived information quality, political interest and political knowledge among Malaysian youth: structural equation model analysis. Cogent Soc. Sci. 7:1964186. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2021.1964186

Hall, J. A., and Baym, N. K. (2012). Calling and texting (too much): Mobile maintenance expectations, (over) dependence, entrapment, and friendship satisfaction. New Media Soc. 14, 316–331. doi: 10.1177/1461444811415047

Ho, S. S., Yang, X., Thanwarani, A., and Chan, J. M. (2017). Examining public acquisition of science knowledge from social media in Singapore: An extension of the cognitive mediation model. Asian J Commun. 27, 193–212.

Holt, K., Shehata, A., Strömbäck, J., and Ljungberg, E. (2013). Age and the effects of news media attention and social media use on political interest and participation: do social media function as leveller? Eur. J. Commun. 28, 19–34. doi: 10.1177/0267323112465369

Hu, D. F. (2010). Villagers’ political trust and its impact on village-level election participation: an empirical study based on a survey of P village in Huizhou city, Guangdong Province, Jinan. J. Philos. Soc. Sci. 3, 156–162. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-5072.2010.03.024

Huang, S. H. (2018). The impact of social capital on online political participation: a survey of residents in Tianjin, Changsha, Xi ’an and Lanzhou. Sociol. Rev. 6, 19–32. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-5154.2018.02.002

Ida, R., Saud, M., and Mashud, M. I. (2020). An empirical analysis of social media usage, political learning and participation among youth: a comparative study of Indonesia and Pakistan. Qual. Quant. 54, 1285–1297. doi: 10.1007/s11135-020-00985-9

Jiang, L., and Gu, M. M. (2022). Understanding youths’ civic participation online: a digital multimodal composing perspective. Learn. Media Technol. 47, 537–556. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2022.2044849

Jin, H. J., and Nie, J. H. (2017). The Influence of Media Use on Chinese Women’s Political Trust: An empirical study of Chinese Netizens. J. Wuhan Univ. (Humanities) 2, 101–112. doi: 10.14086/j.cnki.wujhs.2017.02.012

Katz, E. L. I. H. U. (1940). The Two-Step Flow of Communication: An Up-to-Date Report. Public Opinion Quarterly. 21.

Kim, S. J. (2016). A repertoire approach to cross-platform media use behavior. New Media Soc. 18, 353-372.

Kwon, K. H., Shao, C., and Nah, S. (2021). Localized social media and civic life: motivations, trust, and civic participation in local community contexts. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 18, 55–69. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2020.1805086

Lee, E. W., Shin, M., Kawaja, A., and Ho, S. S. (2016). The augmented cognitive mediation model: Examining antecedents of factual and structural breast cancer knowledge among Singaporean women. J. Health Commun. 21, 583–592. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1114053

Lenhart, A., Purcell, K., Smith, A., and Zickuhr, K. (2010). Social media & mobile internet use among teens and young adults. Millennials: Pew Internet & American Life Project.

Levi, M., and Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 3, 475–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475

Levinson, P. (2003). Unbound thought: epistemology in the age of technology [M]. Nanjing University Press.

Lu, J. Y. (2016). The influence of social media and mobile APP news use on youth political protest. Xiandai Chuanbo 5, 48–54.

Markus, H., and Zajonc, R. B. (1985). “The cognitive perspective in social psychology” in Handbook of social psychology. eds. G. Lindzey and E. Aronson (New York: Random House), 137–230.

McLeod, J. M., Kosicki, G. M., and McLeod, D. M. (1994). The expanding boundaries of political communication effects. In J. Bryant & D. Zillman (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research 123–162. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

McLeod, J. M., Scheufele, D. A., and Moy, P. (1999). Community, communication, and participation: The role of mass media and interpersonal discussion in local political participation. Polit. Commun. 16, 315–336. doi: 10.1080/105846099198659

McLeod, J. M., Zubric, J., Keum, H., Deshpande, S., Cho, J., Stein, S., et al. (2001). Reflecting and connecting: Testing a communication mediation model of civic participation. In Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Washington, DC.

Mishler, W., and Rose, R. (2001). What are the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comp. Pol. Stud. 34, 30–62. doi: 10.1177/0010414001034001002

Morgan, S. E. (2009). The intersection of conversation, cognitions, and campaigns: The social representation of organ donation. Commun. Theory 19, 29–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.01331.x

Mutz, D. C. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nabi, R. L., Prestin, A., and So, J. (2013). Facebook friends with (health) benefits? Exploring social network site use and perceptions of social support, stress, and well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 16, 721–727. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0521

Norman, D. A. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions 6, 38–43. doi: 10.1145/301153.301168

Peng, M. G. (2016). A comparative analysis of the political trust of the middle class of youth and its influencing factors – based on an empirical survey in Guangzhou. Youth Explore 5, 15–24. doi: 10.13583/j.cnki.issn1004-3780.2016.05.002

Pingree, R. J. (2007). How messages affect their senders: A more general model of message effects and implications for deliberation. Commun. Theory 17, 439–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00306.x

Pinkleton, B. E., Austin, E. W., and Fortman, K. K. (1998). Relationships of media use and political disaffection to political efficacy and voting behavior. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 42, 34–49. doi: 10.1080/08838159809364433

Qiu, J., Zhang, R., and Zuo, X. Z. (2014). Research on political identity education of college students. Shehuikexuejia 7, 114–117.

Rainie, H., and Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system (vol. 10). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Robinson, J. P., and Levy, M. R. (1986). Interpersonal communication and news comprehension. Public Opin. Q. 50, 160–175. doi: 10.1086/268972

Schroeder, R. (2010). Mobile phones and the inexorable advance of multimodal connectedness. New Media Soc. 12, 75–90. doi: 10.1177/1461444809355114

Shah, D. V., Cho, J., Eveland, W. P. Jr., and Kwak, N. (2005). Information and expression in a digital age: modeling internet effects on civic participation. Commun. Res. 32, 531–565. doi: 10.1177/0093650205279209

Shah, D. V., Cho, J., Nah, S., Gotlieb, M. R., Hwang, H., Lee, N. J., et al. (2007). Campaign ads, online messaging, and participation: Extending the communication mediation model. J. Commun. 57, 676–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00363.x

Valenzuela, S., Correa, T., and de Zúñiga, H. G. (2020). “Ties, likes, and tweets: using strong and weak ties to explain differences in protest participation across Facebook and Twitter use” in Studying politics across media. Eds. L. Bode and E. K. Vraga (Routledge), 117–134. doi: 10.4324/9780429202483

Verba, S., Nie, N. H., and Kim, J. O. (1971). The modes of democratic participation: a cross-national comparison (vol. 2). Beverly Hills, California: Sage Publications.

Waeterloos, C., Walrave, M., and Ponnet, K. (2021). Designing and validating the Social Media Political Participation Scale: An instrument to measure political participation on social media Technol Soc. 64:101493.

Wang, S. Q. (2013). Political trust, interpersonal trust and non-traditional political participation. Public Adm. Rev. 2:22-51+178-179.

Wang, J. (2017). How media use influence political participation on micro-blog among the undergraduates in china: an empirical measure of political psychology as an intermediary variable. J Journal Commun Res. 50–74.

Wolfsfeld, G. (2022). Making sense of media and politics: five principles in political communication. London: Routledge.

Xiao, T. Z., and Wang, X. (2012). Analysis on the political effect of farmers’ political trust change: a follow-up study of 60 villages in five provinces and cities (1999-2008). Soc. Sci. Res. 3, 43–49.

Yan, Q. H. (2020). Duality: the influence of selective exposure on the differences of political opinion expression among young netizens. Journal. Res. 9:56-78+121.

Yang, X., Chuah, A. S., Lee, E. W., and Ho, S. S. (2017). Extending the cognitive mediation model: Examining factors associated with perceived familiarity and factual knowledge of nanotechnology. Mass Commun. Soc. 20, 403–426. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2016.1271436

Zeng, F. B. (2014). Social capital, media use and political participation of urban residents: based on urban data from 2005 China General Social Survey (CGSS). Xiandai Chuanbo 10, 33–40.

Zhang, P. (2014). Media use and urban residents’ political participation: based on the Chinese General Social Survey. Xuehai 5, 56–62.

Zhang, B. (2017). The relationship between media use and rural residents’ participation in public affairs: an empirical analysis based on CGSS2012 data. Jianghai J. 3, 102–109. doi: 10.16091/j.cnki.cn32-1308/c.2014.05.044

Zhang, Q. (2018). The traditional construction and contemporary inheritance of the feelings of family and country – a cultural investigation based on consanguinity, geography, career and interest. Learn. Pract. 10, 129–130. doi: 10.19624/j.cnki.cn42-1005/c.2018.10.016

Zhou, B. H. (2011). Media contact, public participation and political effectiveness in public emergencies: a case study of Xiamen PX incident. Open Era 5, 123–140.

Zou, W., Hu, X., Pan, Z., Li, C., Cai, Y., and Liu, M. (2021). Exploring the relationship between social presence and learners’ prestige in MOOC discussion forums using automated content analysis and social network analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 115:106582. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106582

Keywords: multimodal connectedness, political participation, O-S-R-O-R model, life span, political trust

Citation: Li M and Li X (2024) The influence of multimodal connectedness on political participation in China: an empirical study of the O-S-R-O-R model based on the life span perspective. Front. Commun. 9:1399722. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1399722

Edited by:

Laura Cervi, Autonomous University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Veronica Yepez-Reyes, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, EcuadorViet Tho Le, Edith Cowan University, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Li and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaobing Li, bGl4aWFvYmluZzAwMjhAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Mengyu Li

Mengyu Li Xiaobing Li*

Xiaobing Li*