94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 26 June 2024

Sec. Multimodality of Communication

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1390843

This article is part of the Research TopicMultimodality in Face-to-Face Teaching and Learning: Contemporary Re-Evaluations in Theory, Method, and PedagogyView all 5 articles

This multimodal conversation analytic study draws upon naturally occurring data from formal, formative reading assessments in an elementary school, general education classroom to investigate the interactional practice of documenting feedback. This consists of the ways teachers and students engage in both oral feedback and its written documentation simultaneously during interaction. Such competencies have been underappreciated by educational research on assessment literacies. Moreover, prior interactional research on formal formative assessment has shed light on talk-based practices that enable oral feedback but has nonetheless neglected the embodied and material practices that are necessary for its written documentation. To investigate how talk, embodiment, and materiality enable feedback to be documented within multiactivity, the current study collected instances of the practice from a multimodal corpus of audio-visual recordings and electronic scans of completed assessment materials. Examination of this collection uncovered straightforward, problematic, and complex interactional trajectories as well as their relationships to institutional outcomes. The study concluded that the more participants to formal, formative reading assessment focus on feedback as talk-in-interaction, the less explicitly that talk-in-interaction is represented in the written documents they collaboratively produce. As a result, important details of both teacher interventions and student performances may be rendered opaque in the material record of the assessment events. These findings extend a burgeoning multimodal turn in the interactional analysis of formal formative assessment and aim to provoke subsequent educational research into interactional assessment literacies.

This multimodal conversation analytic (CA) study draws upon audio-visual recordings from the formal, formative assessment (FA) of reading to provide an analytical account for the practice of documenting feedback (Tomasine, 2023). Documenting feedback refers to the interactional procedures by which teachers and students organize, simultaneously, the discursive and material accomplishment of feedback activity. Feedback is pervasive during formal reading FA, an educational activity common in compulsory school settings whereby classroom teachers take time away from literacy instruction to meet one-on-one with students and measure their reading development. Formal reading FA relies on these teachers to locally adapt standardized materials (e.g., leveled reading passages, test prompts, and evaluation rubrics) in order to generate valid assessments of their students’ reading abilities. Such adaptation may involve feedback, or reformatting of a test prompt and encouragement to try again after a student’s incorrect response indicates that she misunderstood the prompt. Not only do teachers and students engage in such oral feedback, but they also create written inscriptions that document these same events. Documenting feedback thus provides procedures whereby teachers and students can engage, here-and-now, in formative feedback while also making that feedback visible and accountable to other stakeholders (e.g., administrators, parents) who might read the documents at a later time. The current study investigates these procedures using multimodal CA, a methodology sensitive to indigenous methods of practical reasoning (Heritage and Atkinson, 1985), and the ways participants deploy language, body, and material objects (Streeck et al., 2011) in order to produce and recognize social action.

Information on the procedures that enable various stakeholders to engage in formal reading FA has the potential to inform research and policy regarding assessment literacies (AL), or the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for purposeful engagement in educational assessment (Brookhart, 2011; DeLuca et al., 2016; Pastore and Andrade, 2019; Michigan Assessment Consortium, 2020). By influencing the development of teacher training materials, the content of certification criteria, or the focus of in-service professional development, AL seeks to improve learning outcomes for K-12 students. As nuanced and comprehensive as the state of the art has become, AL research and policy continue to neglect interactional practices of assessment administration. Left unexplicated as “procedures” (Schmeiser et al., 1995) or deprioritized as “discrete behaviors” (Pastore and Andrade, 2019), the practical skills that are necessary to participate in assessments have been lost between the broad brushstrokes of educational research and policy. Heritage and Heritage (2013) criticize this tendency within the educational sciences to ignore teachers’ and students’ “indigenous practices” in their call for fine-grained analyses of K-12 FA administration as a “real time educational practice” (ibid, 188). Researchers working in this area have begun to criticize normative FA techniques, such as self-assessment, which they show to pose intractable interactional problems that may make it harder, rather than easier, for students to engage purposefully in FA (Skovholt et al., 2019). The current study aims to extend this line of research by shedding light on the interactional affordances, and challenges, of documenting feedback and providing further impetus for attention to interactional practices as an element of AL.

Selecting analytical tools for the multimodal analysis of documenting feedback requires first identifying what is lacking in the CA literature on K-12 FA. Defined loosely, FA may encompass a wide variety of informal interactions that are embedded within ongoing instructional discourse (Mehan, 1979; Can Daşkın and Hatipoğlu, 2019). The current study focuses on a more constrained form of FA: formal FA, or planned and discrete interactional events that result in documentary evidence of student performance. The first subsection introduces a small but cogent body of CA work on talk during K-12 formal FA. Unresolved issues will then be pursued across the remaining subsections, which review research on the multimodal analysis of writing-in-interaction and, later, writing-in-multiactivity.

One thread binding the CA literature on feedback activity is the central role played by practices of question design. Often approached under the rubric of “advice-giving,” feedback has been found to be organized around question-answer sequences in a wide variety of institutional settings. For example, Butler et al. (2010) demonstrate how telephone and computer-based counselors deploy advice-implicate interrogatives and thereby enable or even encourage their clients to reject the proposed course of action. By doing so, these participants collaboratively pursue the client-centered institutional goals, which normatively constrain the counselors from providing advice more overtly. In contrast, Vehviläinen (2012) demonstrates how question prefacing allows participants to construct more overtly corrective feedback during tertiary academic writing supervision. Here, as seen in other institutional settings (cf. healthcare visits, Heritage and Sefi, 1992), stepwise entry into advice-giving is often done through questioning. This allows the participants to explore the relevance of the imminent advice and calibrate their perspectives on the matter. What is more, prefacing advice with questions allows the participants to mitigate possible resistance from the student to the supervisor’s corrective feedback. As seen in these examples, be they tools for encouraging open-ended decision-making or specific remedial action by the recipient, questions are clearly central to feedback activity.

The centrality of questioning in advice-giving more generally extends also to feedback during K-12 formal FA. For example, Heritage and Heritage’s (2013) study of writing conferences in an elementary school, general education classroom provides strong parallels with Butler et al. (2010) above. Heritage and Heritage investigate what they call diagnostic questioning, or open-ended question designs that encourage students to consider alternatives without overtly displaying the teacher’s preference for a specific response. The pedagogical value of such question-based feedback emerges from the teacher’s restraint; didactic correction would end up “short-circuiting” the student’s learning (Heritage and Heritage, 2013, 184). On the other hand, Skovholt’s (2018) study of feedback sessions in secondary school echoes Vehviläinen’s (2012) findings regarding questions during overly corrective feedback. In Skovholt’s data, participants rely upon optimizing questions and upshot formulations to organize feedback activity. The former display a preference for a positive response while incorporating favorable presuppositions regarding the student’s capabilities (see also Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Boyd and Heritage, 2006). The latter selectively reuse parts of the student’s turn to draw conclusions about the state of the talk in ways that prepare for its subsequent development (see also Heritage and Watson, 1979; Raymond, 2004). By advancing feedback sequences toward specific conclusions, such questioning practices embody and promote the teacher’s feedback agenda.

Although CA research on K-12 FA identifies the key role played by question design, it falls short of analyzing the role of embodiment or materiality in feedback activity. For example, both Heritage and Heritage (2013) and Skovholt’s (2018) analyses are based on video data. Both studies are nevertheless logocentric, refraining from transcription or sustained analysis of multimodal phenomena. Similar criticism can be extended to CA work on advice-giving in general; for instance, Vehviläinen’s (2012) study focuses on talk-based interaction during the analysis of video-based data. The absence of multimodal analysis is particularly salient here, considering that the feedback itself focuses on writing activity (see also Heritage and Heritage, 2013). As such, these lines of research would clearly benefit from incorporating the analytical insights provided by a multimodal CA approach.

In contrast to early work in CA that is characterized by a focus on talk (Schegloff et al., 1977), multimodal CA (Streeck et al., 2011) recognizes important resources provided by the body (Nevile, 2015), objects (Nevile et al., 2014), and the material surroundings (Goodwin, 2017) to meaning-making practices of social interaction. In particular, multimodal investigations of writing-in-interaction (Mondada and Svinhufvud, 2016) provide analytical tools to study embodiment and materiality that complement the logocentric approach to questioning practices during feedback, which are provided by talk-based CA. Tools for studying embodiment are provided by Jakonen’s (2016) work on individual writing and Mlynář’s (2022) work on collaborative writing, both based upon data from the secondary school classroom. These studies explore the distinction between private and public writing (Mondada and Svinhufvud, ibid). Jakonen (ibid), for example, demonstrates how requests for access to another student’s written work (e.g., as a resource for completing one’s own) regularly takes place after careful monitoring of the other’s writing body-in-interaction, orienting to the observable (and thus transcribable) progression of writing. These findings are complemented by Mlynář’s (ibid) regarding collaborative tasks; here, non-writing peers orient to subtle movements of the writer’s pen or gaze (i.e., away from the document surface) as resources to decide when to provide assistance.

Previous research on K-12 writing-in-interaction also draws attention to the materiality of writing or how the physical nature of written inscriptions provides resources for action. Materiality is particularly central to Tomasine’s (2024) study of private and public writing during formal reading FA in the elementary classroom. There, practices of inscription or “graphic acts and the marks resulting from them” (Streeck and Kallmeyer, 2001, 465) are used to organize a range of feedback tasks, from the documentation of student performance to diagnostic evaluation and instruction. During these latter activities, the materiality of test documents plays a key role in the interaction. For example, the participants navigate the private-public divide when the teacher manipulates test papers to provide the student with visual access. Furthermore, both participants position themselves into an embodied participation framework (Goodwin, 2000) that enables mutual scrutiny of the inscribed objects produced on this document surface. Moreover, the reliable, physical existence of previously made inscriptions also provides for the embodied act of gazing at documents to be recognizable to others as the action of “reading” them. Tomasine’s work demonstrates how this materiality enables participants to read “independently,” to be seen “reading,” and to read “together.”

Although multimodal CA provides analytical tools for studying feedback and writing-in-interaction, this literature has yet to provide for how inscriptions may be accomplished that transcend the feedback event as written records of that event. Case in point are the inscriptions analyzed in Tomasine (2024); despite their central role in accomplishing feedback here-and-now during formal reading FA, they make no explicit reference to that feedback’s occurrence. As such, institutional stakeholders (e.g., administrators, teacher colleagues, parents) would not be prepared later on to read these minimal marks (e.g., circles, underlining, brackets) as records of feedback. How more substantial inscriptions that are informative to stakeholders regarding the process and products of feedback activity might be accomplished, in the midst of feedback activity itself, remains to be investigated. That investigation requires analytical tools for approaching multiple, simultaneous courses of action-in-interaction, or multiactivity (Haddington et al., 2014).

Multiactivity has been defined as the “different ways in which two or more activities can be intertwined and made co-relevant in social interaction” (Haddington et al., 2014, 3). A key point of departure is that activities progress at different paces, and the progression of one activity may be prioritized over, or subordinated to, the progression of another. Moreover, this relationship is not fixed but dynamic and emergent, publicly displayed in the ways participants format their actions. Powerful demonstration of such formatting is provided by Mondada’s (2014) work on the basic temporal orders of multiactivity. According to Mondada, activities may occur in parallel without coordination between the units of each activity or, conversely, the relationship may be exclusive, resulting in postponement or abandonment of one activity in favor of another. Commonly, however, activities are temporally related via an embedded order, where one activity is integrated into the units (e.g., sounds, turns, sequences) of another. Attention to how this embedding respects or disrupts the units of each activity (e.g., cut-offs or restarts in the talk) provides important analytical footholds.

Writing-in-interaction often constitutes “a step into multiactivity” (Mondada and Svinhufvud, 2016, 27); work straddling these research programs provides powerful analytical tools. For example, Mortensen’s (2013) study of group discussion highlights structural aspects that bear on the relative ordering of writing and talk. Two phenomena are distinguished: writing aloud, whereby a speaker “indexes the writing activity” in emerging talk (ibid, 121), and writing and talking, whereby a speaker contributes to ongoing talk while otherwise engaged in writing. The latter is characterized by perturbations (e.g., pauses, sound stretches, fillers), which display the speaker’s prioritization of the writing activity. These observations about writing speakers are complemented by Svinhufvud’s (2016) regarding the embodied note-taking practices of writing listeners at the university. Here, counselors are tasked with doing recipiency to the extended tellings of their clients while, simultaneously, taking detailed notes on those tellings. Here, Svinhufvud demonstrates how nodding practices enable counselors to display heightened participation even as they avert gaze from the speaker (e.g., as they move into writing posture to begin inscribing a “writable”), thus navigating multiactivity.

Few studies have explicitly addressed the intersection of multiactivity and writing-in-interaction during oral feedback in K-12 settings. In the context of language education at the adult or tertiary levels, however, studies by Leyland and associates (Leyland and Riley, 2021; Leyland and Gormaz Walper, n.d., forthcoming) and Ro (2023) address related issues. For example, work by Leyland and Riley and Ro (see also Tomasine, 2024) investigates the creation of inscriptions during ongoing talk as well as how such marks may be subsequently deployed as resources for corrective feedback. These studies corroborate the findings of Svinhufvud (2016), whereby listening writers deploy nods to display their continued engagement as they initiate or continue simultaneous writing activity. On the other hand, Leyland and Gormaz Walper (n.d.) (forthcoming) provide novel insight regarding the phenomenon of writing and talking (Mortensen, 2013); these authors demonstrate how writers may prioritize the progression of talk, slowing or halting their writing, when a co-participant unexpectedly expands upon a previous utterance. Notwithstanding, as was mentioned regarding Tomasine (2024) above, these studies fail to demonstrate how inscriptions may be accomplished as explicit documentary evidence that feedback occurred. It remains to be analyzed how such evidence might be accomplished while participants simultaneously engage in the very interaction they are documenting.

This analytical account for the practice of documenting feedback is guided by the following questions. Firstly, How do the participants achieve a shared understanding of their activity? Secondly, How does the achievement of shared understanding relate to the management of multiactivity? Thirdly, How does the achievement of shared understanding and the management of multiactivity relate to the documents themselves?

The current study draws data from the elementary section of a K-12 school delivering an English-medium, USA-based curriculum to the expatriate, multinational, and internationally oriented local communities of a large city in Japan. At this school site, English language arts curriculum is delivered via a reader’s workshop model. Within this model, students build personal collections of “just right” books, culled from the classroom library, which is leveled according to a scheme based on linguistic and thematic complexity. The determination of a student’s reading level has important implications for various stakeholders. Reading level is visibly marked on the cover of every book, meaning that peers are free to compare themselves with one another. Reading levels are also reported to parents, who keep track of and, in some cases, contest the instructional decisions that influence their child’s reading development. Teachers’ instructional decisions may also be evaluated by administrators (e.g., literacy coach, principal, headmaster), who often use aggregated data on reading levels to decide whether and how teachers need support.

At the school site, students’ reading levels are regularly determined via the administration of formal reading FA using the second edition of a commercially produced assessment tool called the Developmental Reading Assessment (Beaver and Carter, 2006) or, more commonly, the DRA®2. On a theoretical level, the DRA®2 targets the constructs of oral reading fluency and reading comprehension (Pearson Education Inc., 2011) using a sample of the student’s reading performance during test administration. In practice, administering the DRA®2 requires teachers to guide students through a series of performance-based reading tasks using standardized materials (e.g., reading passages, administrator scripts with test prompts, and evaluation rubrics). The quality of these performance tasks varies considerably. All levels of the DRA®2 measure oral reading fluency. Some levels include tasks that target a student’s decoding skills or vocabulary knowledge, require the student to identify major story elements, prompt the student to retell the story from memory, or encourage the student to make personal connections with the story’s moral and its main characters.

The data corpus was compiled over the course of a single school year and consists of roughly 6 h of audio-visual recordings and electronic scans of assessment forms. This corpus contains records of 25 naturally occurring administrations of the DRA®2; the researcher coordinated with classroom teachers in order to capture regularly scheduled test administrations. These administrations took place in various locations, both inside and outside the classroom, and most often were in the vicinity of other students who worked on individual tasks. The corpus documents the assessment work of 20 students and six teachers from kindergarten to grade five. Test administrations ranged in length from roughly 5–20 min and were conducted unobserved; video recordings were made using one or two, unmanned, fixed-angle cameras and high-definition lapel microphones. Written inscriptions were collected via electronic, post-administration scans of the assessment materials and, in some cases, direct visual access to the video record. All participants and guardians provided informed consent or assent, following ethics review at the school site.

Analysis began by examining an initial account of documenting feedback that was reported in Tomasine (2023). Within CA, demonstrating the orderliness of single cases constitutes a distinct mode of investigation (Schegloff, 1987); as a single-case analysis, the initial account did not draw systematic conclusions about the practice and focused mainly on the sequential organization of talk-based action. In the single case, the teacher’s intervention resulted in the expansion of a test-item sequence (Marlaire and Maynard, 1990), normatively consisting of the contiguous production of a testing prompt, response, and acknowledgment. This expansion took place after the student responded. The intervention consisted not only of talk but also of embodied and material action; the teacher moved to inscribe the student’s initial response before launching her intervention. Once the student modified his response, the teacher articulated her initial inscription to reflect this modification. These elements guided a search through the 6 h corpus for test-item sequences in which (a) the teacher’s intervention resulted in the expansion of the sequence after the student’s response, and in which (b) the teacher made an initial inscription, which was then revised. Twenty-five potential instances of the practice were located in the corpus.

All of the instances were transcribed using Jefferson’s (2004) conventions for talk in order to foreground the production features that are known to contribute to its turn-taking and sequential organization. Mondada’s (2018) conventions for transcribing multimodality were applied, using the computer program ELAN (Wittenburg et al., 2006) as an aid. These conventions foreground the temporal trajectories of embodied and material actions, which may be coordinated to but which may not coincide with the units of talk (Mondada, 2016). Subsequent analysis using these transcripts resulted in a core collection of five cases. Three cases were selected to illustrate the interactional contingencies that result in both straightforward and problematic trajectories for the feedback sequences and their relation to the resulting written documents. In order to provide the reader with the necessary resources to engage with the analysis, data transcripts are presented at a high level of technical detail. Talk is bolded for clarity in the transcripts and provides a baseline against which multimodal action is temporally coordinated, using a lighter font. The preparation (…), continuation (---) and retraction (,,) of these multimodal actions are indicated and delimited using dedicated symbols (e.g., %, ø, +). These light-colored symbols are inserted into the bolded text and are vertically aligned with short verbal descriptions on lower tiers, each labeled for a specific participant (e.g., t = teacher). Tutorials for all transcription conventions, as well as signposts to more in-depth theoretical resources, are provided in the Appendices 1, 2. Careful attention to these details is necessary to engage with the analysis.

The use of symbols to transcribe the temporal development of embodied and material conduct provides a necessary analytic perspective on such multimodal action. This perspective is complemented by inserting into the transcripts still images, exported from the video-recording, that provide a “synthetic view of the multimodal gestalt” (Mondada, 2018, 90; italics in original). For this reason, the transcript images (abbreviated “TI” in the transcript and analytic text) and the multimodal annotations must be read together; both are derived from the same data and are therefore inseparable elements of a single transcription. Another reason these elements are complementary is that gaze direction is not completely recoverable from the still images alone. In order to protect the anonymity of study participants, the images presented in the transcripts have been edited using filters. In these cases, referencing the multimodal annotation may increase the legibility of the darkened images. A final note is necessary regarding the written documents that are presented in Figures 1–3 These are not still images extracted from video data but, rather, are electronic scans that were made immediately after the data was recorded. The written inscriptions that are visible in these scans are not analyzed as they were being constructed, or transcribed, because camera angles throughout the core collection did not provide necessary, direct visual access to the document surfaces. An alternative method of recovering inscriptions from visible and audible traces, called reconstruction, was also avoided because of the complexity of the inscriptions in question (see Mondada and Svinhufvud, 2016, for methodological issues). For these reasons, the electronic scans, which were collected after administration and are referred to as “Figures,” are separated from the transcripts in the following analysis.

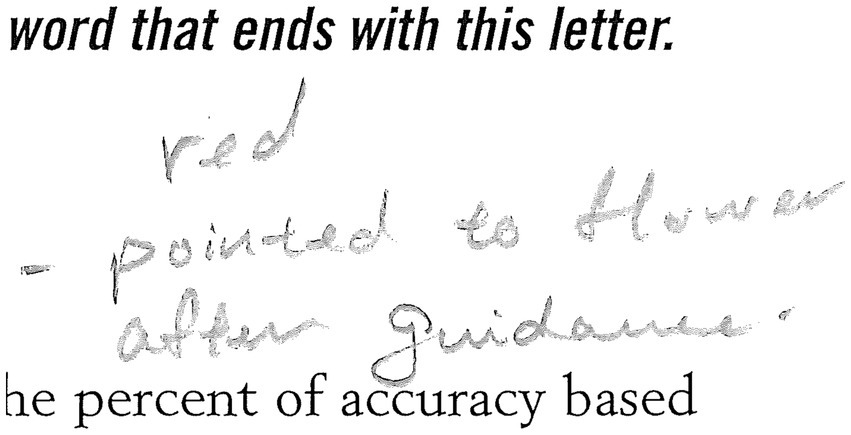

Figure 1. Inscriptions produced during Excerpt 1: from top to bottom: “red”, “—pointed to flower after guidance.”

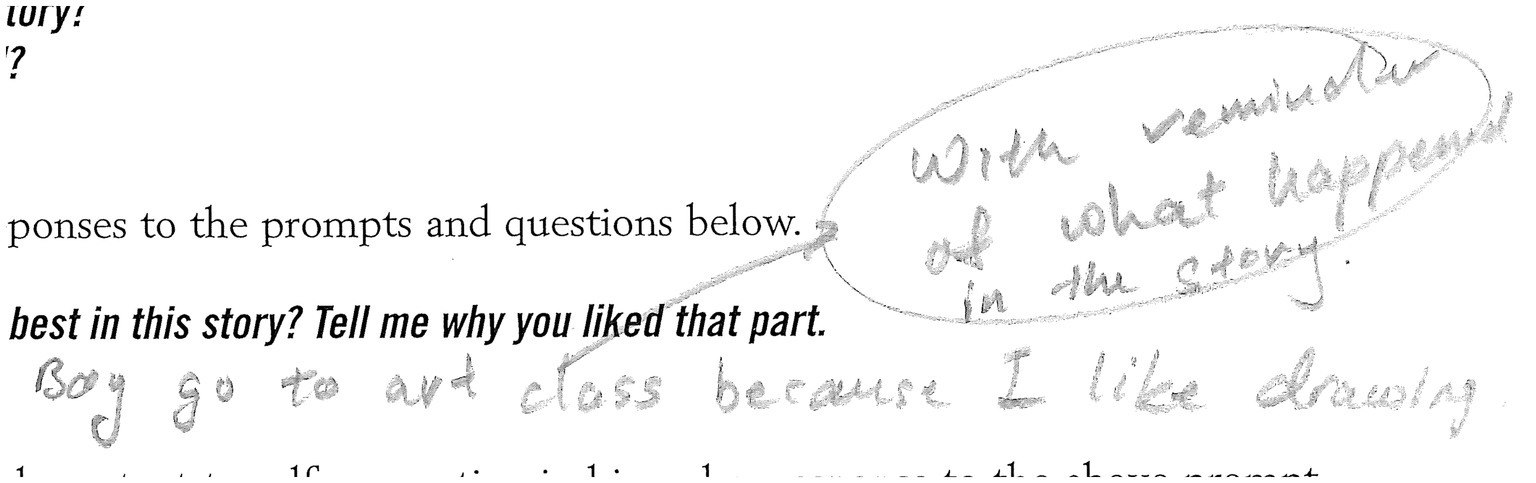

Figure 2. Inscriptions produced during Excerpt 2: from bottom-left to top-right: “Boy go to art class because I like drawing”; “With reminder of what happened in the story.”

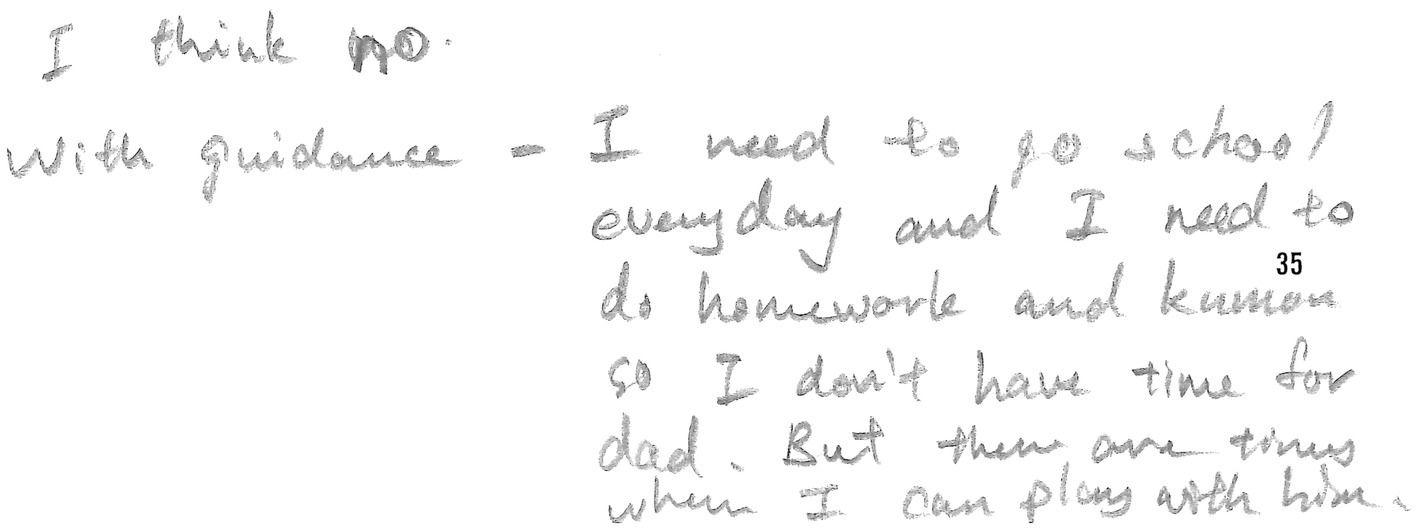

Figure 3. Inscriptions produced during Excerpt 3: from top-left to bottom-right: “I think no.” “With guidance” “—I need to go school every day and I need to do homework and kumon so I don’t have time for dad. But there are times when I can play with him.”

It will be illustrative to begin the analysis with a straightforward example. Here, the participants readily achieve a shared understanding of their activity, smoothly manage the relationship between talk and writing-in-interaction and produce documents that explicitly represent the sequential organization of that interaction. The analysis will focus on how these achievements are enabled by mutual monitoring of embodied and material activity. In Excerpt 1, teacher (T) and student (S) are seated on the floor, side by side. Between them is a book, open to a page with the words, “I can see a red flower.” T holds his administrator script, partly reproduced as Figure 1, in his left hand and a pencil in his right. We join the action as T prompts S (line 01). S’s embodied conduct is annotated as follows: % (gaze); & (manual action). T’s embodied conduct is annotated using the following symbols: ø (gaze); + (manual action).

Here, the participants achieve a shared understanding of their activity by carefully monitoring the progression of one another’s verbal and embodied actions. Notice how their embodied conduct emerges in relation to their verbal turns. For example, S responds to T’s prompt by pointing to the open page (line 02, TI 1), retracting (line 04) only after T has verbally receipted it (line 03). Before receipting, however, T prepares for writing activity and eye gaze (line 02), indicating that he interprets S’s point to be her response. These embodied actions by T are carefully monitored by S. First, she follows T’s gaze movement toward the administrator script by gazing there herself (line 04). Then, as T finishes writing and shifts his gaze back toward the book page, S follows (line 05). With both participants gazing together, T questions the accuracy of S’s previous response, pointing to the book page and holding that point as he shifts his gaze toward her (line 06). T’s gaze arrives at S as his turn comes to a grammatical point of completion; S orients to this convergence by initiating a point toward a different location on the page (line 06). She pauses that initiation, however, when T continues his turn with an increment (line 06, TI 2). S then vacillates between preparing the point and pausing it (line 07, TI 3), finally reaching the page as T completes yet another increment (line 08, TI 4). Only then does T retract (line 09) the point he has been holding. S again monitors T, beginning to retract her point after T has begun to retract his (TI 5), and shifting her gaze in synch with T’s acknowledgment (line 10).

The participants’ mutual monitoring of one another’s ongoing multimodal actions results in a prioritization of the writing activity over the talk. Importantly, the material production of the writable is immediate. T begins to move his writing hand and shift his gaze (line 02), thereby configuring writing, before receipting S’s response (line 03). Furthermore, T begins to retract his writing hand before shifting his gaze to the book page (line 04); completing the writing takes precedent over configuring the intervention. Prioritization of writing over talk is also observable in S’s monitoring of T’s writing activity. During a test-item sequence that transpired immediately before this excerpt, T swiftly and overtly receipted S’s correct answer, positively evaluated it, and engaged in writing; S did not monitor that writing and instead stared out into space. In contrast, here, the potentially problematic nature of S’s response (line 02), adumbrated by T’s minimal receipt (line 03) and immediate engagement in writing (line 04), occasion S’s monitoring of T’s embodied activity. That monitoring continues and is evident in S’s sensitivity to T’s deconfiguring of the writing (line 04); she carefully attends to T’s work with the administrator script and times her gaze shift, in synch with him, toward the book page (line 05).

The straightforward progression of documenting feedback, embodied by the participants’ mutual monitoring and their prioritization of writing over talk, has implications for the material record. Specifically, the serial progression of the feedback is explicitly represented in Figure 1, the document that was produced during Excerpt 1.

This document represents not only the response (“red”), the intervention (“guidance”), and the modified response (“pointed to flower”) but also their serial relationship (“after”). It should also be noted that these are, of course, formulations. For example, the inscription “red” is a rather loose gloss for action that occurred in sequence (i.e., that on line 02, TI 1) and which has been discussed here as pointing. Compare this with the next inscription, which also formulates the student’s embodied action (i.e., “pointed to”) in addition to the graphic object that is its material referent (i.e., “flower”). More or less detailed, both of these formulations are rather specific compared with the formulation of the teacher’s action (“guidance”). Surely, the manner of the student’s pointing gestures could be formulated in (perhaps infinitely) more detail. Nevertheless, the gloss for the teacher’s action is much more general. The reader is not privy to whether such guidance was provided using embodied resources (e.g., T’s manual gesture on line 06, TI 2–4) nor how the talk-based components (e.g., T’s polar interrogative on line 06; its transformation into a choice between “end” and “beginning” at line 08) were designed. As such, these inscriptions are less documents of the feedback, per se, than they are documents of the feedback’s sequential organization. That is, by explicitly serializing S’s response (“red”), T’s intervention (“guidance”), and S’s modified response (“pointed to flower”), the documents are made accountable to the reader as a record of normative feedback activity but are, nevertheless, considerably selective and asymmetrical.

It will be fruitful to continue the analysis with a problematic case. Here, the participants struggle to achieve a shared understanding of their activity, recalibrate the relationship between talk and writing-in-interaction and produce documents that implicitly represent the sequential organization of that interaction. The analysis will focus on how the participants’ lack of mutual attention to the emergence and progression of one another’s multimodal actions precipitates negotiation of the activity. In Excerpt 2, teacher (T) and student (S) are seated in a similar configuration as in Excerpt 1. In addition, similarly, T holds his administrator script, partly reproduced in Figure 2, and a pencil. One important difference is, here, the book that is discussed has been removed from the scene. We join the action as T prompts S (line 01). S’s embodied conduct is annotated as follows: % (gaze); & (manual action). T’s embodied conduct is annotated using the following symbols: ø (gaze); + (manual action).

Here, shared understanding of the activity is not initially achieved but, rather, must be negotiated, due to a lack of mutual attention by the participants for one another’s multimodal actions. Notice how their embodied orientation and attention are problematically dispersed. This begins as T pursues (line 03) S’s absent response (line 02) by quickly producing an increment; S, on the other hand, diverts his gaze away (line 03). T further pursues the response, shifting gaze toward S (line 04). T maintains that gaze, pursuing S’s response across a long gap (line 04, TI 7). When S finally responds, he does so quietly and while gazing up and away from T (line 05). T immediately shifts his gaze toward his administrator script (line 06) and begins reading off his notes from S’s previous retelling of the story, gesturing with each unit (lines 06–08). S does not display recipiency to T’s gestures or his reading, however, only shifting eye gaze toward T as he produces a new response between two units of T’s ongoing turn (line 09, TI 8). This shift does not occasion mutual gaze, however, as T continues gazing at his script and produces two more units in his ongoing turn (lines 10–12). Again, S does not display recipiency to these units; he shifts his gaze away (line 10, TI 9) and maintains it. It is this lack of embodied attention that is held accountable by T, who interrupts his ongoing turn to look at (line 13), touch, and verbally summon (line 14) S. T’s subsequent touch (lines 15–16, TI 10) and talk (line 16) recruit S’s gaze direction (TI 11) and, incidentally, verbal participation (line 17); the latter is, like before (line 09), ignored by T, who continues his turn (line 19).

The participants’ lack of mutual monitoring for one another’s ongoing multimodal actions and the negotiation it precipitates result in a prioritization of the talk over the writing activity. Importantly, the material production of the writable is delayed. S initially responds by claiming insufficient understanding (line 05). T does not receipt this response, nor does he initiate writing it down; instead, he immediately begins to read aloud from his administrator script (line 06). S modifies his previous response by replacing the claim with reference to a scene from the story (line 09). This attempt is unsuccessful because, although T gazes at his administrator script (the location of a potential inscription), his writing hand is deployed in a gesture which he continues (line 09, TI 8), despite S’s production of the potential writable. The design of S’s next attempt displays an orientation to T’s lack of receipt for his previous response; similar topical content is now produced tentatively, with slightly rising intonation (line 17). This too fails to get receipted or ratified as writable; T returns his attention instead to the administrator script (line 18) and continues talking (line 19). S’s unsuccessful attempts to modify his response only come to fruition once T has reformatted the test prompt (lines 21–22). T prefaces this turn with “so” (line 21), orienting to the prompt as emerging from incipiency (Bolden, 2009) and, thus, as having been displaced by the intervening feedback talk.

The problematic progression of documenting feedback, embodied by the participants’ negotiation and their prioritization of talk over writing, has implications for the material record. Specifically, the serial progression of the feedback is implicitly represented in Figure 2, the document that was produced during Excerpt 2.

This document represents only the modified response (“Boy go to art class because I like drawing”) and the intervention (“With reminder of what happened in the story”). What is not represented includes the student’s response that preceded the teacher’s intervention (line 05), those that interrupted it (lines 09, 17), and the teacher’s intervention that succeeded the first part of student’s modified response (line 24). Consequently, the sequential organization of these elements also fails to be explicated; e.g., it must be inferred by the reader when the intervention took place. Notwithstanding, as in the previous example, such inference is both necessary and possible because of the normative organization of the feedback sequence. That is, the reader can (or must) infer that the student produced some “non-response” that precipitated the teacher’s intervention (“…reminder of what…”) which was, itself, succeeded by the modified response that is recorded here (“Boy go to…”). In this way, the feedback agenda and its documentation reflexively constitute one another. Furthermore, some parts of the interaction are curiously absent from the document. Case in point are S’s repeatedly ignored attempts at producing a modified response (lines 09, 17). Surely, these actions were delicately timed by S so as to fit between the units of T’s ongoing intervention. They do not, however, fit neatly into the normative, serial ordering of a feedback’s sequential organization. Furthermore, their exclusion results in documents that not only selectively and asymmetrically represent the interaction’s topical content but also its sequencing.

It will be illuminating to conclude the analysis with a complex example. Here, the participants’ shared understanding, management of multiactivity, and documentation of the interaction’s sequential organization are at times straightforward and at other times problematic. The analysis will focus on how the straightforward progression of documenting feedback is contingent upon the successful management of multimodal resources. Here, in Excerpt 3a the physical scene and props resemble those from Excerpt 1, except that the book is closed. We join the action as T returns to the prompt after checking that S comprehends the task (line 1). S’s embodied conduct is annotated as follows: % (gaze); & (manual action); ∂ (neck and head movement). T’s embodied conduct is annotated using the following symbols: ø (gaze); + (right hand); ≠ (left hand); ∫ (neck and head movement); Ω (lip movement).

At the start, this excerpt is characterized by the participants’ mutual monitoring of one another’s multimodal actions. Notice how they display their waxing and waning engagements in writing and in talk. First, S and T shift their gaze toward one another as T’s prompt comes to completion, orienting to the relevance of turn transition (line 04). T further displays his orientation to S’s upcoming response by moving his gaze and hand, entering into writing position (line 05). A silence ensues when S produces no verbal response; this is not a gap, however, because S fills it with her embodied action. By looking up (line 05) and tilting her head (line 06, TI 13), S displays her participation in the sequence and her problems in producing a response. S’s troubles do not go unnoticed. First, T orients to her embodied conduct by shifting his gaze toward her (line 06). Next, he does encouraging by nodding when perturbations emerge in S’s incipient verbal response (line 07). Finally, T determines that S has finished her response by attending not only to the grammatical and prosodic completion of her verbal turn but also to its embodied elements. That is, T begins configuring writing only after S begins retracting her posture and shifting gaze toward his administrator script (line 08, TI 14).

The participants’ mutual monitoring of one another’s multimodal actions enables them to prioritize the writing over the talk. Importantly, the material production of the writable is immediate. That production is configured even before S begins to produce her verbal response; T moves his gaze and hand toward the script soon after he completes his prompt (line 05). Surely, T does nod his head during S’s incipient response (07), but this cannot be analyzed as doing receipting. Its sequential emergence after a long silence, after perturbations have begun to emerge and simultaneous with the verb, but before its complement, mean that this nod should be analyzed, rather, as doing encouraging to continue. After S continues, however, and produces the verb complement, T does not do verbal receipt of it. Instead, he writes. In fact, before T says anything out loud (see Excerpt 3b, below), he shifts his gaze and moves his pencil to the document surface, writes and brings that writing to completion (line 08). The emerging relevance of T’s writing activity is projected by S, who shifts her gaze to the administrator script even before T does (line 08, TI 14). Further evidence for the prioritization of writing can be found nearly 2 s after T’s pencil makes contact with the administrator script. Here, T silently mouths the word “kay” (line 08), recognizable on the visual record as a form of the receipt token “okay.” Here, T’s orientation to the fact that talk is being put on hold for writing approaches, but does not break, the interactional surface.

We return to the action as the writing activity comes to a close; in Excerpt 3b T has brought his hand to rest on the administrator script at his lap. Now he receipts (“Okay,” line 09) S’s response and, simultaneously, moves his gaze and extends his left hand toward the book “I Can Play.”

Here, shared understanding of the activity is achieved by carefully negotiating the necessary elements of an appropriate response. This can be observed in how the questions are tilted toward the answers they tentatively receive. First, T immediately begins to answer his own question with a designedly incomplete utterance (lines 11–12), looking at S (line 13) as he points to the book (lines 11–12, TI 15). S produces an aligning response, but after a gap (line 13) and with strongly rising intonation (line 14). T reformats their collaborative utterance as agreeable with a tag question (line 15), to which S aligns with a nod, after another gap (line 16). This pattern of question-answer-agreement is repeated. T prefaces the next question with “however” and gestures while punching up “always” (line 17, TI 16), displaying preference for a negative answer. S produces one, although very quietly and after a gap, with rising intonation (line 19). T then produces an agreeable with another tag question (line 20), and S aligns, again quietly, again after a gap (line 22). T prefaces the next question with “but” and punches up “sometimes” (line 23); S aligns to his displayed preference for an affirmative answer, nodding after a gap (line 24). This last sequence bucks the trend. Rather than seeking agreement, here, T does acknowledgment (line 25) and then upshots the entire series of “think(ing) together” (line 09) as relevant to S’s upcoming telling (line 26).

The participant’s negotiation of the sequence’s progression results in their prioritization of the talk over the writing. Critically, no writables emerge, while the writing implements are instead repurposed for gestural action. Throughout the wider corpus, writables that represent a student’s reading performance are regularly produced during test-item sequences but here, from the start, T prospectively formulates the ensuing interaction to be something different (line 09). By doing so, T temporarily suspends the relevance of producing writables. This explains why S cannot be seen orienting to her contribution to the collaborative utterance (“Pla:y?,” line 14), her embodied display of agreement (“nods,” line 16), her negative response token (“°No¿°,” line 19), her verbal agreement (“°°(Right/Yeah)°°,” line 22), her embodied alignment (“nods,” line 24) or, finally, to her provision of information (“No:¿,” line 30) as being potentially writable. This is evident because S maintains her gaze on the book, rather than upon the administrator script (TI 15–16), from the first sequence (line 11) until after T has brought the intervention to a close and prompts S to start her modified response (line 33). That is, she does not orient to the script as a document surface upon which T’s writing activity is projectable or relevant. T’s efforts suspend that relevancy in three ways: (1) prospectively by his action projection (line 09); (2) continually each time he uses his writing hand to make contact with the book (lines 11–12, TI 15; line 15) or to gesture in the air (lines 17, TI 16; lines 20, 23, 26, 28), and (3) retrospectively when he formulates the talk-based intervention as having displaced the production of writable answers when he restarts the prompt from incipiency (Bolden, 2009) by prefacing it with “so” (line 32).

Now T’s intervention is coming to a close; in Excerpt 3c T has moved his hand into writing position above the paper, and S has shifted her gaze toward him. Now she begins to respond (“Be(.)cau:s:e …,” line 36) to T’s guiding question, and T begins writing (line 36).

Here, the participants are able to achieve a shared understanding of the sequence’s progression because they carefully monitor one another’s verbal and embodied actions. This is evidenced by how their conduct concentrates not only between, but also within, the boundaries of S’s emerging units. For example, T produces continuers in the turn space with no gap and no substantial overlap after S produces the first unit of her telling (line 39), after a first list item (line 41), and after each of the remaining items in that list (lines 43, 46). T thereby returns speakership to S and displays alignment to her ongoing telling. When the progressivity of that telling becomes problematic, however, T’s conduct occurs within S’s units. Surely, the formats of T’s actions when S has finally gotten underway (“Mhm¿,” lines 37; “°°Mhm¿°°,” line 54), or when perturbations emerge (“nod,” line 48; “°Mhm¿°,” line 55) may do continuing in other sequential contexts. It would be more appropriate, however, to analyze them as doing encouraging. A vivid example happens as S struggles to close her telling. First, T orients to S’s trouble when he gazes at her (line 57). S then completes her unit with a slightly rising intonation (line 57) and seeks T out with her gaze (line 58). T does encouraging verbally (line 58) and then curls his wrist forward repeatedly (line 59, TI 18) in a symbolic gesture interpretable as imperative to “hurry up” or “keep going.”

It is the participants’ careful monitoring of one another’s multimodal actions that enables them to prioritize writing or talking contingently, moment-to-moment. Crucially, each participant temporarily disengages from their own activity in order to monitor the progression of the other’s. First, S disengages from her talk in order to focus on T’s writing. One example is when she shifts gaze toward the administrator script to monitor it (lines 36–38, TI 17); here, S restarts her turn by repeating the verb “need,” orienting to the perturbation occasioned by her change in focus. Another example occurs when S has just finished producing the list. Here, S’s changing attention occasions a restart of the entire unit as she repeats both the sequential connector “And” as well as the pronoun “I” (line 47). This is another case where S prioritizes the progression of the writing over the production of her ongoing talk. T, on the other hand, does the opposite: temporarily disengaging from his writing in order to focus on problems in S’s talk. For example, returning to her repetition of “And I” (line 47), T pauses his writing to attend to S. As her turn becomes perturbed, T lifts his pencil off the writing surface (line 47). Then, when a longer pause emerges, T shifts his gaze toward S (line 48), only to nod (line 48) and return to writing (line 49) as soon as S’s turn gets on its way.

Returning to the data, in Excerpt 3d S’s response is now winding down; both participants have retracted from mutual gaze and S completes the upshot of her telling and brings her turn to a close. Now, as she begins to shift her gaze (line 61) toward T, he initiates repair (line 62).

Here, the participants rely on multimodal resources to negotiate the progression of the sequence. This is observable in the ways talk and gaze are deployed in order to organize shared attention. First, S orients to T’s writing activity when she shifts her gaze to his administrator script (line 61–62). This shared focus of attention is temporarily deconfigured as T shifts his gazes toward S and initiates repair (line 62–63). S orients to the relevancy of T’s gaze when she completes the repair with a nod (line 63, TI 19), thus deploying an embodied resource that can be seen by T. Having seen the nod, T receipts it (line 64) and gazes again at the script (line 65). T then evaluates S’s response in parallel with his writing (line 66), an engagement S continues to monitor with her gaze. She relinquishes that monitoring, however, when T produces a negative sequential connector and pauses (line 68); S gazes at T and finds him writing while he initiates a follow-up question (lines 68, TI 20). T then pauses this question, retracts his writing hand and begins to shift his gaze (line 68), reaching S just as his turn comes to completion (line 69). S responds affirmatively, and T begins to configure subsequent writing (line 71) before producing a minimal receipt token (lines 72).

The participants’ negotiation of the sequence’s progression results in their prioritization of the talk over the writing. This is evidenced by the fact that postponement and resumption of writing recurrently prioritize the units of the talk. This can be seen first when T interrupts his writing to initiate repair (line 62). Here, T first produces talk in parallel with writing. Furthermore, even his embodied shift of attention (manual retraction, gaze preparation, line 62), does not perturb the ongoing talk. Furthermore, T begins to receipt S’s subsequent response (line 64) before his gaze has shifted back to the writing surface (line 65). As such, T can be seen to prioritize the repair talk over his writing. Such orientation can also be found in the expansion sequence that follows. Here, as before, T begins by talking and writing (line 68, TI 20). And again, T makes an embodied shift of attention, retracting his hand from writing while preparing to gaze at S. One difference is that, in the former, T’s turn comes to completion without perturbation. Here, T pauses for nearly half a second (line 68) before completing the unit (line 69). Two remarks can be made about this perturbance. First, while progressivity slows, the grammatical parsing is congruent and nothing is repeated; contrast this with the cases discussed above (lines 36–38, line 47, Excerpt 3c). Second, pausing here allows T to coordinate the arrival of his gaze upon S with the completion of his unit; compare this with another case discussed above (line 06, Excerpt 1). It would thus be inappropriate to analyze the perturbance here as a lingering prioritization of the writing over the talk.

The participants’ contingent accomplishment of shared understanding and the concomitant shifts in how they manage multiactivity throughout Excerpts 3a–3d has implications for the material record. Specifically, both the sequential organization and the content of the feedback are variably represented in Figure 3 below, the document that was produced during Excerpt 3.

This document represents the response (“I think no.”), the intervention (“With guidance”), and the modified response (“I need to go school every day and I need to do homework and kumon, so I do not have time for dad. But there are times when I can play with him”). The interactional sequencing of these elements is also represented, although not verbally as in Excerpt 1 (see Figure 1) but, rather, graphically. In the writing system employed here, top-to-bottom and left-to-right conventions contribute to the readability of this document as a serial organization of its elements: a response, followed by an intervention, followed by a modified response. With access to the transcripts, it is also possible to identify what is not represented here. This includes the teacher’s intervention that succeeded the first part of the student’s modified response. Recall that the student produced her telling to conclude with an upshot (lines 59–60, Excerpt 3c). This upshot occasioned T’s initiation of repair (lines 62–66, Excerpt 3d) to confirm its details. That interaction is represented in T’s inscriptions here not as confirmation but, rather, as a seamless part of S’s modified response. It may also be noted that T followed up the repair sequence with a question (lines 68–72, Excerpt 3d), during which he suggested an understanding that was, unlike the repair sequence, not based on anything S had said. Although S aligned tentatively to that suggestion (line 70, Excerpt 3d), it is represented in T’s inscriptions here as a part of her modified response (it is, however, separated with a period). In summary, this document resembles both of the documents in Figures 1, 2. Like the former, here, a serial ordering is explicitly represented between (some) parts of the feedback sequence. Like the latter, here, elements of the interaction that fall outside of that normative sequencing fail to be rendered in the documentation. Like both, here, the content is thus selective and asymmetrical.

This section will consider the study’s findings in light of previously discussed literature on feedback, writing-in-interaction, and multiactivity, as well as from the perspective of educational research on AL. The current account of documenting feedback was guided by interest in participants’ methods for achieving shared understanding, managing multiactivity, and producing written records of their feedback event. Emerging from collection-based analysis and illustrated using three instances above, these methods consisted of mutual orientation to emerging units of talk and embodied action that allowed for the discursive and material accomplishment of a feedback sequence consisting of a response, followed by an intervention, and then followed by a modified response. How these orientations allowed for the straightforward operation of the practice was demonstrated in Excerpt 1 above. Here, the interactional accomplishment of the feedback’s sequential organization had both serial and simultaneous elements. Regarding the former, feedback itself emerged within a testing sequence where the teacher’s test prompt was followed by the student’s response, and this occasioned an expansion sequence that displaced explicit, third-turn acknowledgment and allowed the teacher to launch an intervention. The teacher deployed a polar interrogative to encourage his student to modify her initial response independently (cf. Butler et al., 2010; Heritage and Heritage, 2013); when that modification was not forthcoming, the teacher modified his turn incrementally toward a tilted question design (cf. Vehviläinen, 2012; Skovholt, 2018). This entire intervention was also serially organized because the teacher engaged in written inscription of the student’s response before launching verbal remediation of it. Upon the student’s production of an appropriately modified response to this remediation, the teacher then closed the expansion sequence. This serial ordering of the elements in the feedback sequence was achieved through the participants’ mutual monitoring of one another’s incipient, ongoing, and diminishing engagements. This was observable in the student’s method for determining when to prepare and retract her embodied responses: she monitored the emerging units of her teacher’s verbal turn as well as his embodied movements into and out of writing. Thus, the serial ordering of the feedback sequence was accomplished by the simultaneous deployment of both linguistic and corporeal resources. At the same time, such mutual orientation by the participants resulted in a multiactivity configuration that prioritized writing over talk and produced documents that explicitly represented the feedback’s sequential organization.

These findings are significant from the perspective of AL because they highlight how assessment administration is an event organized through shared interactional practices. On a surface level, this would appear harmonious with policy developments (e.g., Michigan Assessment Consortium, 2020) that articulate AL not only for teachers but also for students and other stakeholders to educational assessment. In fact, vivid demonstration of shared interactional competencies which are necessary to participate in formal reading FA administration may be found in Excerpts 2, 3 above. In Excerpt 3a, prioritization of writing over talk was achieved collaboratively (cf. Excerpt 1) when the teacher forwent acknowledgment of the student’s response in order to write while his student silently observed him do so. In contrast, shared practices of mutual monitoring were deployed collaboratively, if toward complementary ends, in Excerpt 3c; here, the student interrupted her talk (cf. Mondada, 2014) to focus on the progression of the teacher’s writing and the teacher vice versa. The latter, in particular, illustrates careful monitoring of another’s ongoing action; the teacher used a variety of nodding practices to support the ongoing telling of his student (cf. Svinhufvud, 2016; Leyland and Riley, 2021; Ro, 2023; Tomasine, 2024). Perhaps the most powerful illustration of how formal reading FA administration relies on shared monitoring practices is provided by Excerpt 2. Here, mutual orientation to embodied and material engagements (e.g., being seen to read from the administrator script; cf. Tomasine, 2024) was critical for managing multiactivity (e.g., prioritizing talk over writing) so that the teacher could launch a feedback intervention; lack of orientation on the part of the student was treated as problematic and made accountable. This accountability underscores the shared nature of declarative and imperative turn formats as a practice for initiating feedback, alongside the question formats analyzed by Heritage and Heritage (2013) and Skovholt (2018). The support such analyses might appear, at first glance, to offer recent, comprehensive AL policy must be tempered; observe what is and who shares in these instances. Here, AL is not shared between abstract structural categories of educational agents (i.e., teacher, student) as a notion of what assessment means but, rather, between human beings as a shared method for producing multimodal actions that are mutually recognizably, in situ, as assessment.

The current study contributes to recent multimodal EMCA research that investigates how practices of inscription reflexively organize the accomplishment of K-12 student performance by explicating the interactional procedures underpinning the practice of documenting feedback. Those procedures consisted of carefully articulating the parameters of appropriate student performance so as to fit within an accountable feedback sequence consisting of a response, followed by an intervention, and then followed by a modified response. How this articulation is reflexively organized by the accountability of the feedback’s sequential organization was demonstrated in Excerpt 2 above. Here, the participants’ conduct deviates in orderly ways from the normative operation of the practice. Namely, neither does the teacher make an inscription of the student’s initial response, nor does the student orient to the teacher’s ongoing engagement in a talk-based intervention. This exemplifies, in absentia, the close monitoring of a co-participant’s embodied and material engagements that Jakonen (2016) demonstrated to be a key resource for participating in writing-in-interaction. It should not be implied that the student was unresponsive to the teacher’s articulation of parameters for an appropriate response, specifically its moral grounds: the student’s having previously recalled specifics of the story from which the selection of a favorite “part” should be possible. On the contrary, the student twice produced responses which clearly fit those parameters. The fact that these modified responses were both ignored by the teacher, only for substantially similar modifications to be accepted moments later, points to a key normative requirement for accomplishing documenting feedback. That is, a modified response can only become such a thing if it is produced serially subsequent to a (completed) remedial intervention. In the same vein, the written inscriptions that were produced as a result of this interaction also demonstrate how the status of the student’s modified response relies upon the accountability of the feedback’s sequential organization. Here, the inscribed student’s response is implicitly readable as having occurred after the inscribed intervention which, itself, is implicitly readable as having occurred after an initial response which is, in fact, not inscribed here at all. This analysis updates the account of documenting feedback (Tomasine, 2023) by showing the practice to be essentially multimodal, achieved through reflexive organization of talk and writing.

These contributions are significant from the perspective of AL because they position the social interactional organization of educational assessment as a praxeological concern. At face value, this would seem to support recent theoretical developments (e.g., Pastore and Andrade, 2019) that identify social-emotional and praxeological competencies as overlapping core elements of AL. In fact, evidence that social relationships are inextricably related to practical administration may be found in Excerpts 1, 3 above. In Excerpt 1, the teacher receipts, rather than ignores, his student’s initial, problematic response before launching a remedial intervention. Furthermore, this intervention is underbuilt, coming to possible completion several times; its incremental nature provides multiple opportunities for the student to fix the problem herself (cf. Heritage and Heritage, 2013). In Excerpt 3, receipt of a problematic response is similarly followed by incremental explication of the parameters for an appropriate modification. The teacher launches his intervention with “Okay” and announces that he and the student will “think together.” The subsequent intervention is designed for the student to be successful, using questions that are tilted toward specific answers (cf. Skovholt, 2018). Moreover, the student’s subsequent modified response is, in turn, sensitive to its interactional environment; the student interrupts her ongoing telling to focus on the progress of the teacher’s writing. This resembles the sensitivity observed by Mlynář’s (2022) and confirms his observation that the minute details of embodied writing activity provide resources for non-writing participants to design their own actions. The student in Excerpt 1 is also sensitive to her co-participant when she organizes her deictic points in relation to the teacher’s verbal and embodied actions. The apparent support provided here to AL theory at the intersection of socio-emotional and praxeological competencies must be qualified by considering where and for whom this intersection occurs. The social and praxeological competencies investigated here do not intersect at the single teacher or student who is, thereby, connected with their respective community of teaching or learning but, rather, these competencies intersect at moments of practical assessment administration and, thereby, connect specific teachers with specific students as they collaboratively organize those moments.

The current study asked How participants to documenting feedback achieve a shared understanding of their activity, how the achievement relates to the management of multiactivity, and how achieving shared understanding and managing multiactivity relate to the documents themselves? The study found that mutual orientation to emerging units of talk and embodied action allowed the participants to prioritize writing over talk en route to accomplishing feedback sequences consisting of a response, followed by an intervention and then followed by a modified response. The study also found that negotiating the progression of that sequence led to the prioritization of talk over writing, and that this led to material documentation which less explicitly rendered the sequential organization of the feedback activity. These findings draw implications for multimodal, EMCA research into K-12 educational assessment because they identify the configuration of writing vis-à-vis talk to be an important point of divergence between interactional and institutional sequences of feedback. Specifically, whether and how a teacher and his student orient to the relevance and potential prioritization of writing after the student produces a response portends smooth or troublesome progression for the subsequent accomplishment of feedback-in-multiactivity. Demonstration of this divergence can be found in the analysis of Excerpt 3 above. Here, after the student produced her initial response, the participants accomplished documenting feedback by mutually orienting to the multiactivity configuration as one that prioritized writing-in-interaction over talk-in-interaction (see Excerpt 3a above). It was here that they displaced the teacher’s acknowledgment, which normatively succeeds the student’s response within a test-item sequence and mitigated the necessity of any additional talk by the student in the face of such displacement. This is an example of multiactivity in which one activity is embedded within another at the level of the sequence (cf. Mondada, 2014). This embedding was achieved through the participants’ mutual visual orientation to the document surface as the location of the teacher’s embodied and material engagement. Furthermore, prioritization of writing here resulted in written inscriptions that explicitly (albeit graphically) represented the interactional sequencing or the normative, serial ordering of a student’s response, her teacher’s intervention, and the student’s modified response. Notwithstanding, later on during the same interaction, a shift in the multiactivity configuration resulted in prioritization of talk over writing. Interestingly, in a way that corroborates Leyland and Gormaz Walper (n.d.) (forthcoming), this prioritization of talk was accomplished through writing and talking, observed elsewhere (cf. Mortensen, 2013) as a practice for prioritizing writing over talk. One difference between them is that in the current data, perturbations only included grammatically congruent parsing via pausing (cf. Mondada, 2014) and not the fillers or sound stretches observed by Mortensen (ibid). As a result of prioritizing talk over writing, the inscriptions that emerged implicitly represented the student’s reading performance in a way that made it inextricable from the teacher’s intervention (see Excerpt 3d above). Thus, it appears that the more participants prioritize feedback as a talk-based, discursive accomplishment (i.e., talk first, write later), the less transparent are the material inscriptions that emerge as written documentation of it. Moving forward, subsequent research must explore the consequences that obtain when teachers write earlier, or later, during formal FA and other assessments, for reading as well as other skills.

These implications are significant from the perspective of AL because they direct attention to administration interaction as a perspicuous site for inquiry into competencies for educational assessment. Without being able to effectively organize or participate in the multimodal, social interactional practices that underpin formal reading FA administration, teachers and students such as those who participated in the current study could not, arguably, leverage whatever AL competencies they might otherwise possess. Such competencies might provide for the effective planning and alignment of assessments with curriculum, for self-monitoring, metacognition, and goal setting or the effective reorganization of subsequent teaching and learning that capitalizes on shared understanding between teachers and students. It is these very competencies, however, that take for granted not only that student performance can be generated and documented during assessment administration but, and critically, how. The current study sheds light on one way in which these accomplishments may be undertaken; by organizing instances of talk and writing-in-interaction during assessment administration into accountable trajectories of feedback consisting of initial responses, interventions, and modified responses. This method emerged in the present data as a powerful and pervasive way of doing feedback during formal reading FA, both in talking and in writing. To inquire about these accomplishments is to inquire about competencies without which educational assessment activities before and after each administration event could not and would not function. Surely, there are limitations to generalizing the current account of documenting feedback, one rather specific interactional practice that has been observed in one, rather specific context. How this practice might function outside of formal assessment, FA or reading assessment are key questions for future research. These questions cannot be addressed within the confines of this article. Instead, they are earmarked as programmatic concerns for what constitutes interactional AL more generally, an inquiry toward which the current study has but attempted an initial step.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Review Board at the School Site. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

JT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (23K02088).

The author thanks Misao Okada for feedback on early analysis, as well as two reviewers and the editor for their critical comments.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1390843/full#supplementary-material

Beaver, J., and Carter, M. (2006). The developmental reading assessment-second edition (DRA2). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Bolden, G. B. (2009). Implementing incipient actions: the discourse marker ‘so’ in English conversation. J. Pragmat. 41, 974–998. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2008.10.004

Boyd, E., and Heritage, J. (2006). “Taking the history: questioning during comprehensive history-taking” in Communication in medical care: interaction between primary care physicians and patients. eds. J. Heritage and D. W. Maynard (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 151–184.

Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Educational assessment knowledge and skills for teachers. Educ. Meas.: Issues Pract. 30, 3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2010.00195.x

Butler, C. W., Potter, J., Danby, S., Emmison, M., and Hepburn, A. (2010). Advice-implicative interrogatives: building “client-centered” support in a children’s helpline. Soc. Psychol. Q. 73, 265–287. doi: 10.1177/0190272510379838

Can Daşkın, N., and Hatipoğlu, Ç. (2019). Reference to a past learning event as a practice of informal formative assessment in L2 classroom interaction. Lang. Test. 36, 527–551. doi: 10.1177/0265532219857066

DeLuca, C., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Luhanga, U. (2016). Teacher assessment literacy: a review of international standards and measures. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 28, 251–272. doi: 10.1007/s11092-015-9233-6

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. J. Pragmat. 32, 1489–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., and Nevile, M. (2014). “Towards multiactivity as a social and interactional phenomenon” in Multiactivity in social interaction: beyond multitasking. eds. P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 3–32.

Heritage, J., and Atkinson, J. M. (1985). “Introduction” in Structures of social action, studies in conversation analysis. eds. J. M. Atkinson and J. Heritage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–16. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511665868.003

Heritage, M., and Heritage, J. (2013). Teacher questioning: the epicenter of instruction and assessment. Appl. Meas. Educ. 26, 176–190. doi: 10.1080/08957347.2013.793190

Heritage, J., and Sefi, S. (1992). “Dilemmas of advice: aspects of the delivery and reception of advice in interactions between health visitors and first-time mothers” in Talk at work: interaction in institutional settings. eds. P. Drew and J. Heritage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 359–417.

Heritage, J., and Watson, D. R. (1979). “Formulations as conversational objects” in Everyday language: studies in ethnomethodology. ed. G. Psathas (New York: Irvington Publishers), 123–162.

Jakonen, T. (2016). Gaining access to another participant’s writing in the classroom. Lang. Dialogue 6, 179–204. doi: 10.1075/ld.6.1.06jak

Jefferson, G. (2004). “Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction” in Conversation analysis: studies from the first generation. ed. G. H. Lerner (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 13–31.

Leyland, C., and Riley, J. (2021). Enhanced English conversations-for-learning: constructing and using notes for deferred correction sequences. Linguist. Educ. 66:100976. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2021.100976

Marlaire, C. L., and Maynard, D. W. (1990). Standardized testing as an interactional phenomenon. Sociol. Educ. 63, 83–101. doi: 10.2307/2112856

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning lessons: social Organization in the Classroom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Michigan Assessment Consortium. (2020). Assessment literacy standards: a national imperative. Available at: https://www.michiganassessmentconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/MAC_AssessLitStds_2017_9.19.17.pdf. (Accessed May 7, 2024)

Mlynář, J. (2022). Lifting the pen and the gaze: embodied recruitment in collaborative writing. Text Talk 43, 69–91. doi: 10.1515/text-2020-0148

Mondada, L. (2014). “The temporal orders of multiactivity” in Multiactivity in social interaction: beyond multitasking. eds. P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 33–76.

Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: language and the body in social interaction. J. Sociolinguist. 20, 336–366. doi: 10.1111/josl.1_12177

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: challenges for transcribing multimodality. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 51, 85–106. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Mondada, L., and Svinhufvud, K. (2016). Writing-in-interaction: studying writing as a multimodal phenomenon in social interaction. Lang. Dialogue 6, 1–53. doi: 10.1075/ld.6.1.01mon

Mortensen, K. (2013). Writing aloud: some interactional functions of the public display of emergent writing. 2013 Proceedings of the Participatory Innovation Conference PIN-C. 119–125.

Nevile, M. (2015). The embodied turn in research on language and social interaction. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 48, 121–151. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2015.1025499