- Department of Media Studies, Lecturer and Postdoctoral Researcher, The University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Instagram influencers of marginalized identities and subjectivities, for example those that are plus sized or people of color, often express that their content is moderated more heavily and will sometimes place blame on the “the algorithm” for their feelings of discrimination. Though biases online are reflective of discrimination in society at large, these biases are co-constituted through algorithmic and human processes and the entanglement of these processes in enacting discriminatory content removals should be taken seriously. These influencers who are more likely to have their content removed, have to learn how to play “the algorithm game” to remain visible, creating a conflicting discussion around agentic flows which dictates not only their Instagram use, but more broadly, how creators might feel about their bodies in relation to societal standards of “acceptability.” In this paper I present the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign as a case study example which contextualizes some of the experiences of marginalized influencers who feel content moderation affects their attachments to their content. Through a lens of algorithmic agency, I think through the contrasting alignments between freedom of expression and normative representation of bodies in public space. The Instagram assemblage of content moderation, presents a lens with which to view this issue and highlights the contrast between content making, user agency, and the ways more-than-human processes can affect human feelings about bodies and where they do and do not belong.

Introduction

Instagram influencers of marginalized identities and subjectivities, for example those that are plus-sized or POC, often express through their social media that their content is moderated more heavily and will sometimes place blame on what they call “the algorithm” as the source of their feelings of discrimination. Marginalized influencers’ claims that “the algorithm” engages in discriminatory practices of content removal should be taken seriously. It is well known that biases in social media content moderation perpetuate discrimination in society at large (Noble, 2018; Gillespie, 2024), but, biases are also co-constituted through an entangled algorithmic and human process. As Gerrard and Thornham (2020) describe:

Machine learning moderation compares content with existing data, which means unique content needs to be already normative, or at least ‘known’ for machine learning moderation to ‘see’ it as a constitutive element to prompt action, such as deletion … When content is flagged, it is often redirected to a human commercial content moderator (CCM) who is given ‘seconds’ (Roberts, 2017b) to decide if it should stay or go. (p. 1269).

The content moderation described here is just one of the ways that content is filtered through Instagram, as sometimes content moderation is outsourced to users to “flag” certain content as inappropriate, and this is fed into moderation algorithms (Crawford and Gillespie, 2016). Whether done by algorithmic processes or by humans, this process of mediating and moderating content is based on existing normative assumptions about bodies and moralities, and reflects current issues and topics which affect everyday life (such as the over policing of fat bodies, queer bodies and people of color in public spaces). This is also the case with generative AI, LLMS (Rogers and Zhang, 2024), and the replication of content, as Gillespie notes “generative AI tools tend to reproduce normative identities and narratives, rarely representing less common arrangements and perspectives. When they do generate variety, it is often narrow, maintaining deeper normative assumptions in what remains absent” (2024, p.1).

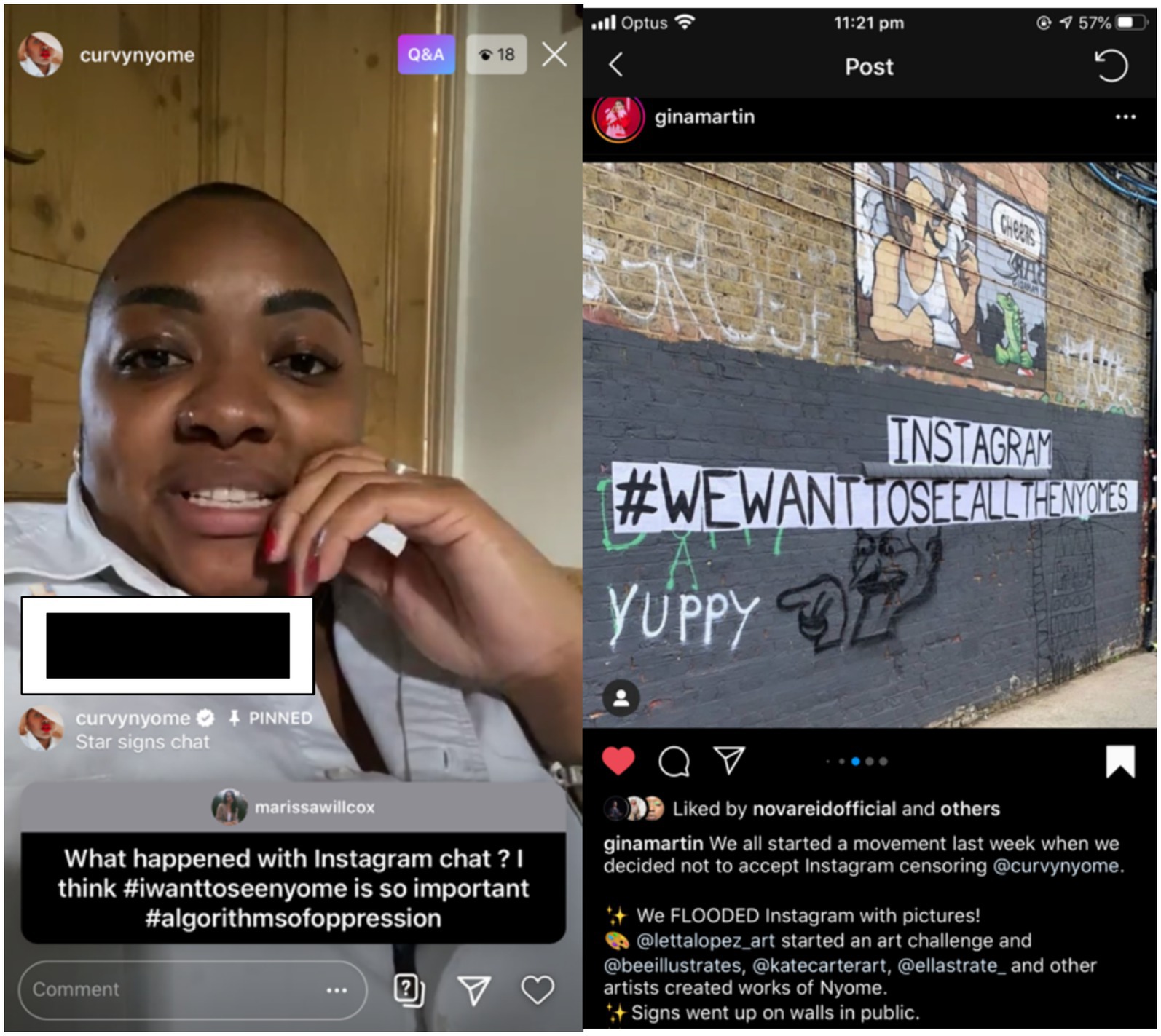

The two images below (Figure 1) are examples of this over policing and expressed discontent by influencers about discriminatory content removals. The image on the left is of Nyome Nicholas-Williams (@curvynyome) doing an AMA.1 Nicholas-Williams is a public figure and the face of a social media campaign called #IWantToSeeNyome, which focuses on body positivity and the policing of plus-sized, Black women on Instagram through content moderation. The campaign was started in London by model Nicholas-Williams, activist campaigner Gina Martin and photographer Alexandra (Alex) Cameron. The image on the right posted by Martin (@ginamartin) showcases the cultural significance of the movement for local Londoners through the graffiti art spotted around London at the time. In this paper I present the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign as a pop cultural example that contextualizes some of the experiences of marginalized influencers who express discontent at their social media content being flagged or removed, specifically content of their own bodies.

Figure 1. @curvynyome and @ginamartin posting about the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign. Reproduced from Instagram with permission of @curvynyome and @ginamartin.

Though part of Instagram’s community guidelines outline what seems to be a reasonable way of deciphering what can and cannot be posted to Instagram’s public platform, the moderation of creative works in response to what Instagram deems as appropriate or not can, in practice, sometimes reinforce existing racist (Noble, 2018; Haimson et al., 2021; Siapera and Viejo-Otero, 2021) and sexist (Gerrard and Thornham’s, 2020; Are’s, 2022; Paasonen et al., 2024) stereotypes around which bodies are allowed to be naked in public space and which are not. The case study of the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign serves as a connector in this paper of three disparate focuses of the research; the theoretical exploration of algorithmic agency, how content moderation practices on Instagram reflect cultural biases, and a discussion of the emotional and affective attachments creators can have to their Instagram content. I have drawn this case study from a larger ethnographic project, in which I use digital ethnographic methods, including interviews and Instagram Live interviews (Willcox, 2023) to understand how feminist and queer content creators make spaces of belonging online. Nicholas-Williams was not a participant of the larger study, and I did not conduct an interview with them, but instead used content analysis and digital ethnography to understand and trace the ways this social media campaign reflected current cultural narratives around felt experiences of content moderation for marginalized influencers.2

#IWantToSeeNyome and “fighting back”

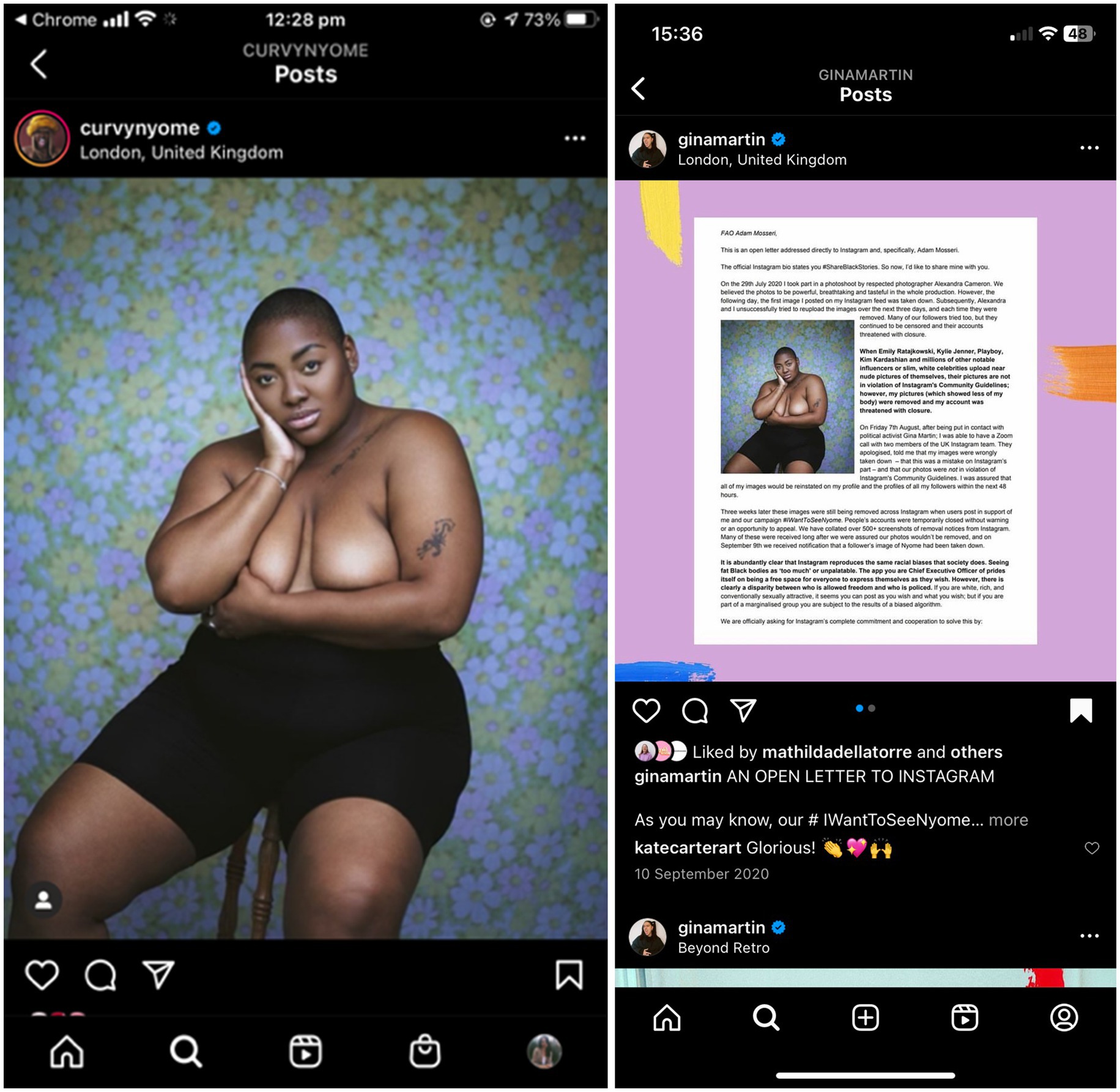

The #IWantToSeeNyome campaign arose in response to Nicholas-Williams posting this photo (Figure 2) to her Instagram feed, a self portrait taken by Alexandra Cameron, and it almost instantaneously being removed due to Instagram’s policy around breast exposure.

Figure 2. Nicholas-Williams’ post and letter to Instagram. Reproduced from Instagram with permission of @ginamartin.

Nicholas-Williams, Martin, Cameron and their followers argued that Instagram was censoring Black, plus-sized bodies more often than white, thin bodies in similar photographic poses. To illuminate this, they urged their Instagram followers to post this same photo (Figure 2) to their feeds with the hashtag #IWantToSeeNyome and then to send them screenshots if it was taken down (which happened often). About 1,000 instances of the image being removed from different people’s pages was recorded.3 Later, a letter was sent to Instagram by the creators and activists about this incident, asking Instagram to review their policy so as not to engage in discriminatory content removals. To prove this as a discriminatory practice, Nicholas-William’s images, the screenshots of the removals and other images of white and thin women posing in the same way was sent to Instagram (Figure 3).

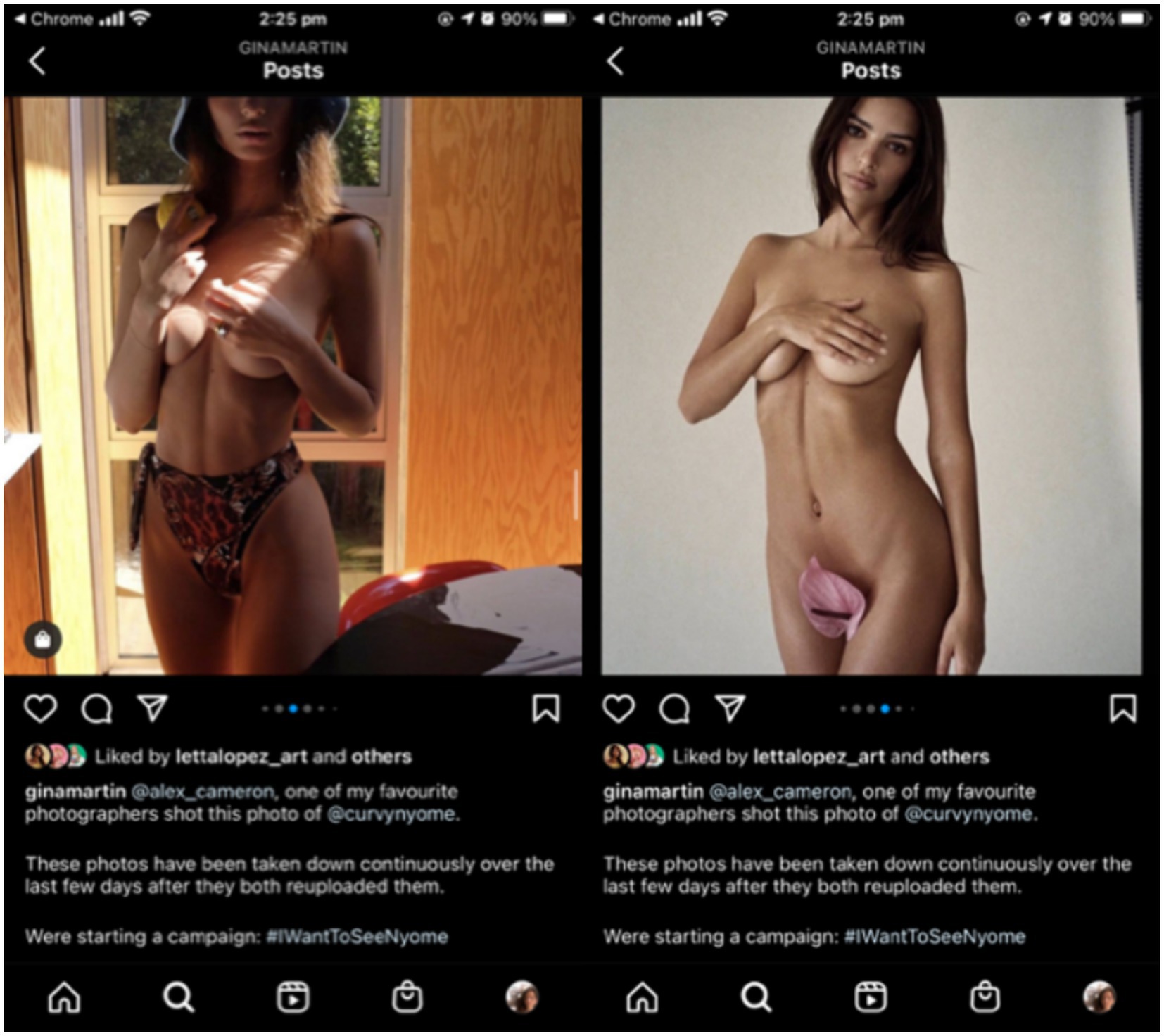

Figure 3. Examples of what does not get deleted, posted by Gina Martin. Reproduced from Instagram with permission of @ginamartin.

In their campaign, Nicholas-Williams, Martin, and Cameron suggested this removal practice presents a racist and patriarchal double-standard in content moderation due to the evidence of white thin women in the same pose not having their content removed. This claim is difficult to prove, from the perspective of the Instagram user, because much of the content that gets moderated is inconsistent with the guidelines. From their study on underweight, mid-range and overweight women and their removal of images on Instagram, Witt et al. (2019) note that “concerns around the risk of arbitrariness and, indeed, ongoing distrust of the platform among users, are not unfounded. The empirical results are statistically significant” (p. 3). Their analysis of image removal found there was a large number of false positives, or images, which were removed even though they “matched” the community guidelines. This speaks to some of the confusion associated with the process of content moderation, which is arguably a practice made to be intentionally confusing by platforms to keep users from having control, even of their own content (Pasquale, 2015; Gillespie, 2018). An article by Gillespie (2022) notes that rather than fully moderate or remove content, many platforms now use machine learning algorithms to reduce the visibility of content deemed as “risky enough” in order to evade critique for their policies on moderation. One of these content reduction practices is popularly known as “shadowbanning.” According to Middlebrook (2020) shadowbanning is a way of subversively hiding accounts through making them not visible through the explore page, hashtags or certain search terms. This leads to reduced visibility for people who create content that is non-normative (Waldman, 2022). Gillespie, in his discussion of the politics of visibility using generative AI, stresses that by “examining how generative AI tools respond to unmarked prompts…when cultural categories and identities went unmarked in the prompt, non-normative alternatives rarely appeared in responses” (2024, p. 9). This shows a problematic consensus across content moderation and content generation, where reproducing and moderating is based on a societal norm which is often biased, privileging the content of the dominant and oppressive cultural and social groups.

Content moderation at Instagram is designed to be difficult for users to understand. It is precisely because this process lacks transparency, that Nicholas-Williams, Martin and Cameron wrote a letter to Instagram about its policy around moderation. The influencers noted this was a way of “fighting back” against discriminatory content removal practices. Nicholas-William’s edited Instagram caption about the letter that was sent to Instagram says:

Who knew these images @alex_cameron captured of me would start such a movement, I will not call them a problem as they are far from it. They have however opened up a much bigger conversation that must be had regardless of discomfort, and it is even more of an issue now as @mosseri pledged to amplify Black voices back in June when speaking to Cosmo about the shadowbanning ‘accusations’… As we can see nothing about that pledge has come to fruition … if anything it has gotten worse. This is only the beginning @instagram has a lot to answer for.

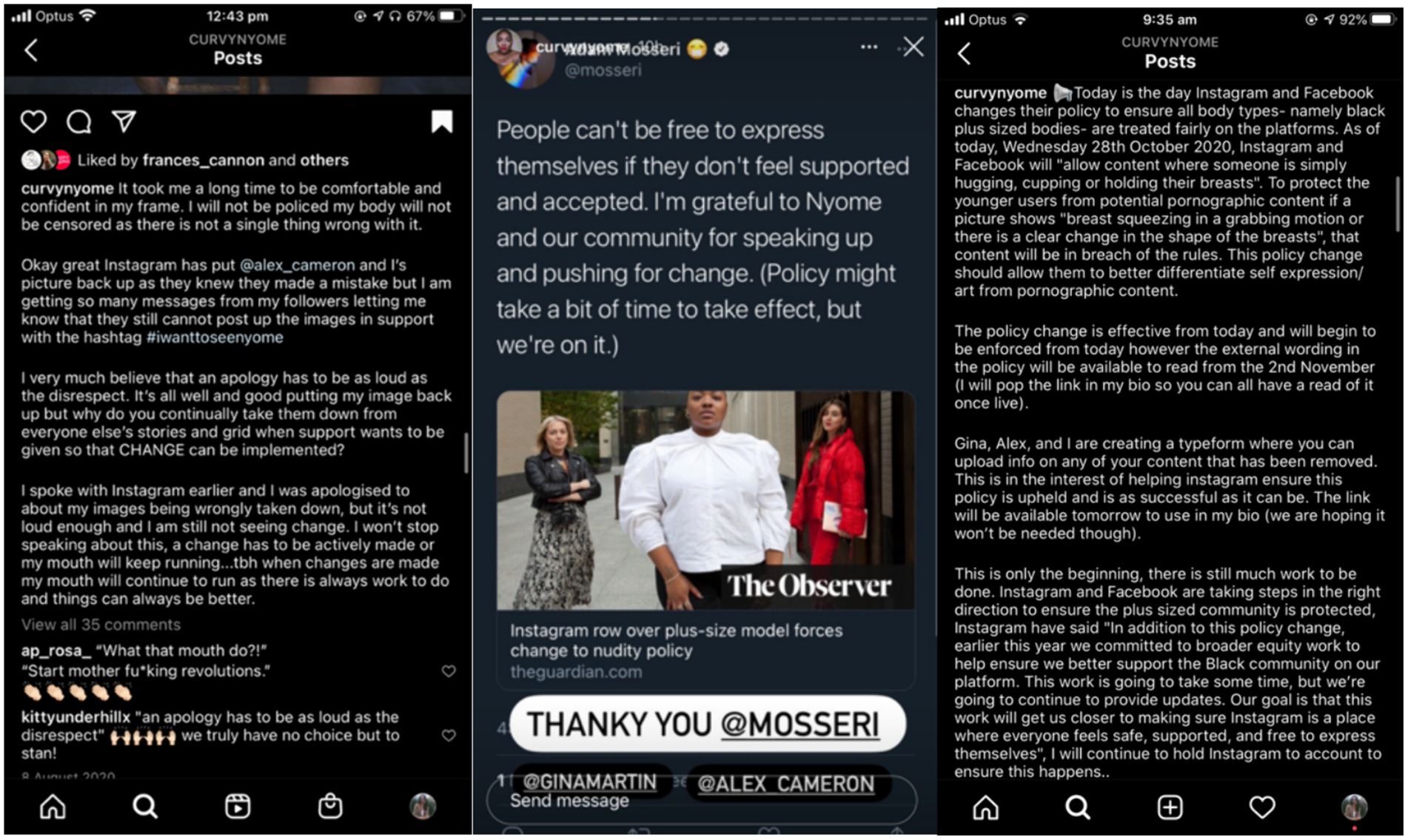

As Nicholas-Williams, Martin and Cameron argued throughout the campaign, removing images of plus-sized, Black women but not those of thin, white, women demonstrates the ways patriarchal and racist biases can be built into moderation algorithms (which Instagram often claims are objective or unbiased) (Bonini and Treré, 2024). Gerrard and Thornham’s (2020) study highlights that there is a “pervasive platform policing of the female body in particular” and that there is a “call within platforms’ community guidelines for users to surveil and problematize each other’s bodies by flagging content they think glorifies eating disorders” (p. 1278). This is part of a much bigger issue, which Nicholas-Williams calls attention to. Whether bodies are moderated by other humans and/or by moderation algorithms, there is a need to focus on how some Black, plus-sized women feel their bodies are being policed more heavily than others’ bodies in public online spaces (Faust, 2017; Nash, 2019; Middlebrook, 2020; Hattery and Smith, 2021; Elkin-Koren et al., 2022; Bonini and Treré, 2024). The tension in this argument is highlighted in recent posts from Nicholas-Williams responding to the lack of advancement in the movement, which I discuss in a latter section (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Nicholas-Williams’ responses to Instagram. Reproduced from Instagram with permission of @curvynyome.

The algorithm

Influencers across platforms often state in their content that they are unhappy with their content removals, and many make “back up accounts” to ensure that if they are shadowbanned or their account access gets removed that they have a space to continue creating. Glatt (2022) writes about this with YouTube influencers where “the algorithm” is often positioned as a “powerful character” in the professional lives of content creators (p. 2). The conflation of many algorithmic systems into considering the algorithm as one oppressive tool is likely derived from a myriad of factors, one of which can be linked to the “imagined affordances” (Nagy and Neff, 2015) of the platform as there are certain “expectations for technology that are not fully realized in conscious, rational knowledge” (p. 1). Influencers targeting “the algorithm” as the source of blame for their content being moderated is an oversimplified notion, as there are many algorithms at Instagram which sort, rank and filter content and many influencers are aware of this. However, the emotive posts about content removal by those in the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign demonstrate the emotional and affective attachments that Instagram influencers can have to the ways their Instagram content is moderated by more-than-human processes.

There are conflicting elements of agency and control associated with making creative content for a platform like Instagram; these rely on algorithmic processes to sort and rank which content gets seen and which does not. This points to the discursive and sometimes unsaid knowledge and experience that Nicholas-Williams highlights when they are angry at the algorithm for removing their images about Black, plus-sized bodies. It becomes less about focusing on algorithmic processes themselves and more about the power that social media platforms have (through algorithms) to mediate, and indeed, moderate human (perceptions of) bodies that I unpack here.

I discuss this experience of moderation through a lens of agency by looking at Nicholas-Williams’ campaign, and the ways the more-than-human process of content moderation creates a sense of discontent about which bodies belong in Instagram and which do not. This critical analysis speaks more broadly to my discussion of the ways the more-than-human elements of Instagram can shape human perception and experience of bodies and belongings (Willcox, 2023).

Algorithmic agency

Algorithms, which are a series of numbers and characters (code) that work as programs within machines to learn and make decisions, do have material agency, but their agency is reliant upon human intervention and interaction. They operate through logic systems modeled on human forms of reasoning (Wilson, 2017, p. 141; see also Bryson, 2020). Bucher (2018) suggests that “we conceive of government and governmentality as particularly helpful concepts in understanding the power of algorithms. Algorithms do not simply have power in the possessive sense; they constitute ‘technologies of government’” (p. 37). Operating as instruments, algorithms become tools through which prediction can create certain outcomes. One way that Bucher describes this is through a broad lens of “distributed agency.” For Nicholas-Williams this distributed agency can be seen in how they ask their followers to post the same image (which was originally deleted from their profile) to their own profile grids to see if it is deleted as quickly. This distribution of the moderation to other users also relates to the question Bucher asks: “If algorithms are multiple and part of hybrid assemblages … then where is agency located? Who or what is acting when we say algorithms do this or that?” (2018, p. 51). Here, with #IWantToSeeNyome we see a mediated process of “distributed agency” which shows how human intervention in algorithmic content moderation can alter subjective experiences of some Instagram users. Bucher quotes Barad in stating that “agency is not an attribute that someone or something may possess, but rather, a name for the process of the ongoing reconfiguration of the world” (2018, p. 51). Agency in algorithmic systems and cultures is, therefore, distributed among and within human and non-human entanglements; it flows and changes with time and place. Barad (2007) describes how “agency is ‘doing’ or ‘being’ in its intra-activity. It is the enactment of iterative changes to particular practices … Agency is about changing possibilities of change entailed in reconfiguring material discursive apparatuses of bodily production” (p. 178).

Both Bucher’s and Barad’s accounts of agency offer the possibility of reconfiguring the concept of agency from that which is situated in one thing or another to the act of doing, being or becoming in between, with and through different actors. “The space of agency is not restricted to the possibilities for human action. But neither is it simply the case that agency should be granted to non-humans as well as humans” (Barad, 2007, p. 178). This is particularly relevant when considering the structure of agency and control as a process of push and pull between the Instagram users in this research and the algorithmic processes which affect their feelings of agency. Through analyzing the dynamics between the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign and the reactions from Instagram’s head Adam Mosseri, it becomes clear how this process affects certain user’s perceptions of content moderation as racially biased and fatphobic. Additionally, by Nicholas-Williams, Martin and Cameron asking their followers to also post the removed image to their own pages and screenshot the removal, they engage a broader community in the algorithmic process, documenting the discriminatory removal for a campaign and proposed policy revision.

Layers of agency in content (over) moderation

Caroline Are (2022) studies the Instagram shadowban in relation to sexy or spicy content through an autoethnographic approach, documenting her experiences both as a pole dancer and an Instagram creator. She finds that,

Instagram’s governance of bodies has been found to rely on old-fashioned and non-inclusive depictions of bodies… using standards more akin to sexist advertising (Sparks and Lang, 2015) than to the progressive sexual practices showcased by the platforms’ own users. Shadowbans are a key technique through which these standards are implemented. (p. 2003).

In her experiences of her pole dancing content being removed from her @bloggeronpole Instagram account, Are expresses that there is a “sense of powerlessness arising from content posted into a void, particularly after the aforementioned digital labor of crafting posts in the hope to reach old and new audiences” (2022, p. 2014). This power imbalance, where users are not given the agency to post images of their own bodies, or know about their content being secretly censored via a shadow ban, shows

a lack of clarity and overall sense of discrimination [which] raises questions about the platforms’ role in policing the visibility of different bodies, professions, backgrounds, and actions, and their role in creating norms of acceptability that have a tangible effect on users’ offline lives and livelihoods, as well as on general perception on what should and should not be seen (Are’s, 2022, p. 2016).

Are’s (2022) analysis of “the shadowban cycle” from personal experience points also to the sense of powerlessness which Nicholas-Williams feels when posting her self-portrait and having it removed. This, and the statement that “It took me a long time to be comfortable and confident in my frame. I will not be policed; my body will not be censored” (Nicholas-Williams, Figure 4) highlights the multiple ways personal feelings of bodily and sexual expression are negatively impacted by content removals and shadow banning. More-than-human algorithmic processes are shown here, to affect human experiences of agency when engaging especially in posting images about user’s own bodies.

In the image on the left, Nicholas-Williams says, “It’s all well and good putting my image back up but why do you continually take them down from everyone else’s stories and grid when support wants to be given so that CHANGE can be implemented?” In the image in the center, the CEO of Instagram, Mosseri, responds to the news coverage around the campaign by saying that “people cannot be free to express themselves if they do not feel supported”; Nicholas-Williams posted this response to her story. In the image on the right, Nicholas-Williams describes her interaction with Instagram around policy change and how she intends to combat the discrimination faced by the plus-sized and Black community. The language she uses in these posts around protecting and expressing demonstrates the emotional and embedded ways Instagram content is, for some people, an expression of self, and that policies around algorithmic content moderation need to be careful to protect minoritized groups from being further marginalized or excluded. The quote also points to the ways algorithmic processes and policies feed back into user interpretation of the platform.

This series of interactions between the user (Nicholas-Williams) and the platform (Instagram) shows how the layers of control and agency are negotiated differently for marginalized people entangled in algorithmic systems (Duguay et al., 2020). Bucher and Helmond (2017) describe this relationship as a “feedback loop” which builds a protocol for interacting through the “generative role of users in shaping the algorithmically entangled social media environment” (p. 28). The notion of feedback loops conceptually highlights the complex, non-linear structure of automated content moderation. “While algorithms certainly do things to people, people also do things to algorithms” (Bucher, 2019, p. 42). As I point out through my analysis of the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign, “the social power of algorithms—particularly, in the context of machine learning—stems from the recursive ‘force-relations’ between people and algorithms” (Bucher, 2019, p. 42). Therefore, the ways that users like Nicholas-Williams approach platform usage is affected by how they engage with algorithmic processes. In turn, since social media environments are also affected by algorithmic processes, such as content moderation, everyday platform usage is reflective of normative assumptions made by users. Put simply, it is not a matter of placing blame on the user or the platform for issues of racialized or sexualized content moderation, but rather, seeing this type of moderation as part of an iterative and entangled relationship which is based on (often racist and sexist) societal norms. My analysis of the #IWantToSeeNyome social media campaign, and the ways Nicholas-Williams and Mosseri discuss the process of content moderation and its socio-technical elements of inclusion/exclusion, shows the nuanced ways we need to think through, as a collective community of scholars and social media users, the impacts and the affective responses that over moderating content has on certain marginalized bodies. Rather than look at content moderation through a lens of risk and safety, platforms might also take up the call to allow for more user agency in content creation. As creator expression is what drives platform profit and engagement, their needs and discontents should be taken seriously.

Conclusion

Content moderation at Instagram is both a human and automated process. Moderation and machine-learning algorithms, users that flag content, and people who work as content moderators have agency in deciding what content gets flagged or deleted from people’s pages. This process is reflective of normative biases around bodies. In response to this action of content moderation of certain bodies over others and this feeling of “powerlessness” (Are, 2022) over “my body being censored” (Nicholas-Williams), influencers learn how to do what Cotter (2019) calls “playing the algorithm game” (Cotter, 2019) where they make content that fits within the content moderation rules in order to remain visible and keep their account access. Through my case study analysis, I present an example of how this creates a conflicting discussion around agentic flows which dictates not only creator’s Instagram use, but more broadly, how creators might feel about their bodies. I make this point through drawing on the work of Bucher (2018) and Barad (2007). While the contrasting alignments between freedom of expression and normative representation around bodies is not a new one—the Instagram assemblage of content moderation presents a new lens with which to view this issue as a broader societal issue which needs to be addressed both by platforms and through user agency and engagement.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platforms’ terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations. RMIT Ethics committee Project number: CHEAN A&B 21229-11/17 Risk classification: Low Risk.

Author contributions

MW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^AMA means “ask me anything” and is a function on Instagram Live.

2. ^Due to the limitations of this paper format and length, the content of the case study rather than the methodological explorations from the project are discussed here.

3. ^See letter posted to Gina Martin’s page and sent to Instagram (Figure 2) noting the amount of times the image was removed on follower’s pages.

References

Are, C. (2022). The Shadowban cycle: an autoethnography of pole dancing, nudity and censorship on Instagram. Fem. Media Stud. 22, 2002–2019. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2021.1928259

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe Halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning : Duke University Press. Available at: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_books.html

Bonini, T., and Treré, E. (2024). Algorithms of resistance: the everyday fight against platform power : MIT Press. Available at: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_books.html

Bryson, J. J. (2020). “The artificial intelligence of the ethics of artificial intelligence” in The Oxford Handbook of Ethics of AI. eds. M. D. Dubber, F. Pasquale, and S. Das Oxford University Press, 1–25.

Bucher, T. (2019). The algorithmic imaginary: exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. In The social power of algorithms, Routledge. 30–44.

Bucher, T. (2018). If… then: algorithmic power and politics : Oxford University Press. Available at: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_books.html

Bucher, T., and Helmond, A. (2017). “The affordances of social media platforms” in The SAGE handbook of social media. eds. J. Burgess, T. Poell, and A. Marwick (London: SAGE Publications Ltd).

Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: how digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media Soc. 21, 895–913. doi: 10.1177/1461444818815684

Crawford, K., and Gillespie, T. (2016). What is a flag for? Social media reporting tools and the vocabulary of complaint. New Media Soc. 18, 410–428. doi: 10.1177/14614448145431

Duguay, S., Burgess, J., and Suzor, N. (2020). Queer women’s experiences of patchwork platform governance on tinder, Instagram, and vine. Convergence 26, 237–252. doi: 10.1177/1354856518781530

Elkin-Koren, N., De Gregorio, G., and Perel, M. (2022). Social media as contractual networks: bottom up check on content moderation. Iowa Law Review. 107, 987–1050.

Faust, G. (2017). Hair, blood and the nipple. Instagram censorship and the female body : Gender Open Repositorium.

Gerrard, Y., and Thornham, H. (2020). Content moderation: social media’s sexist assemblages. New Media Soc. 22, 1266–1286. doi: 10.1177/1461444820912540

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet : Yale University Press. Available at: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_books.html

Gillespie, T. (2022). Do not recommend? Reduction as a form of content moderation. Soc. Media Soc. 8:205630512211175. doi: 10.1177/20563051221117552

Gillespie, T. (2024). Generative AI and the politics of visibility. Big Data Soc. 11:20539517241252131. doi: 10.1177/20539517241252131

Glatt, Z. (2022). “Precarity, discrimination and (in)visibility: an ethnography of “the algorithm” in the YouTube influencer industry” in The Routledge companion to media anthropology. eds. E. Costa, P. Lange, N. Haynes, and J. Sinanan (New York: Routledge), 546–559.

Haimson, O. L., Delmonaco, D., Nie, P., and Wegner, A. (2021). Disproportionate removals and differing content moderation experiences for conservative, transgender, and black social media users: marginalization and moderation gray areas. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 5, 1–35. doi: 10.1145/3479610

Hattery, A. J., and Smith, E. (2021). Policing black bodies: how black lives are surveilled and how to work for change : Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Middlebrook, C. (2020). The Grey area: Instagram, Shadowbanning, and the erasure of marginalized communities. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3539721

Nagy, P., and Neff, G. (2015). Imagined affordance: reconstructing a keyword for communication theory. Soc. Media Soc. 1. doi: 10.1177/2056305115603385

Nash, C. A. (2019). Fuck Zucc. We will not be silent: Sex workers’ fight for visibility and against censorship on Instagram : Carleton University Available at: https://curve.carleton.ca/7790dd71-1caa-4f08-b95a-70c720f32dfe

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: how search engines reinforce racism : NYU Press. Available at: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_books.html

Paasonen, S., Jarrett, K., and Light, B. (2024). NSFW: sex, humor, and risk in social media : MIT Press. Available at: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_books.html

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society : Harvard University Press. Available at: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_books.html

Rogers, R., and Zhang, X. (2024). The russia–ukraine war in chinese social media: llm analysis yields a bias toward neutrality. Soc. Media Soc. Chicago. 1:20563051241254379.

Siapera, E., and Viejo-Otero, P. (2021). Governing hate: Facebook and digital racism. Television New Media 22, 112–130. doi: 10.1177/1527476420982232

Willcox, M. (2023). Bodies, belongings and becomings: an ethnography of feminist and queer Instagram artists. PhD Dissertation. Available at: https://researchrepository.rmit.edu.au/esploro/outputs/9922211513201341

Keywords: content moderation, feminism, gender, algorithms, agency, Instagram, social media, race

Citation: Willcox M (2025) Algorithmic agency and “fighting back” against discriminatory Instagram content moderation: #IWantToSeeNyome. Front. Commun. 9:1385869. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1385869

Edited by:

Izzy Fox, Maynooth University, IrelandReviewed by:

Sarah Laiola, Coastal Carolina University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Willcox. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marissa Willcox, bS5nLndpbGxjb3hAdXZhLm5s

Marissa Willcox

Marissa Willcox