- 1School of Sociology, Politics, and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

- 2Department of International Relations, Universitas Hasanuddin, Makassar, Indonesia

Southeast Asian nations are vulnerable to fake news and disinformation due to the lack of digital literacy, growing dependence upon online platforms, and the non-democratic nature of ASEAN member states. ASEAN has agreed in the past years to decide, at the normative level, the importance of countering fake news and disinformation. However, it lacks a collective, regional approach. It is suggested that ASEAN define what fake news and disinformation consist of, elevation to a non-traditional security threat, and establishment of an ASEAN-centered fast-checking network as feasible policy options to counter fake news and disinformation in the region. In countering this sensitive issue, special attention is needed to consider ASEAN’s philosophical foundations of non-interference, non-intervention, and respect for sovereignty, which allows state practices of surveillance, legal prosecutions, firewalls, and censorships to be maintained.

1 Introduction

The agenda to counter fake news and disinformation has started to gain traction among the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN perceives the issue as critical, as it leads to misleading and harmful information that may undermine the domestic stability of Southeast Asian states. However, the normative-level agreements within ASEAN have made a tangible, regional approach far from being realized. This qualitative inquiry utilizes primary and secondary data between 2017 and 2023, focusing on the increasing number of fake news and disinformation in Southeast Asia in this period. It assesses the present ‘outdated’ collective policies taken by ASEAN and individual Southeast Asian states, and provides policy recommendations for the way forward. In 2023, ASEAN released a document affirming UNESCO’s definition that fake news and disinformation are similar, which is “…information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization or country” (ASEAN, 2023a, p.6). For clarity, this policy brief will use the terms ‘fake news’ and ‘disinformation’ interchangeably, following the official terms used under ASEAN in multiple past forums discussing disinformation.

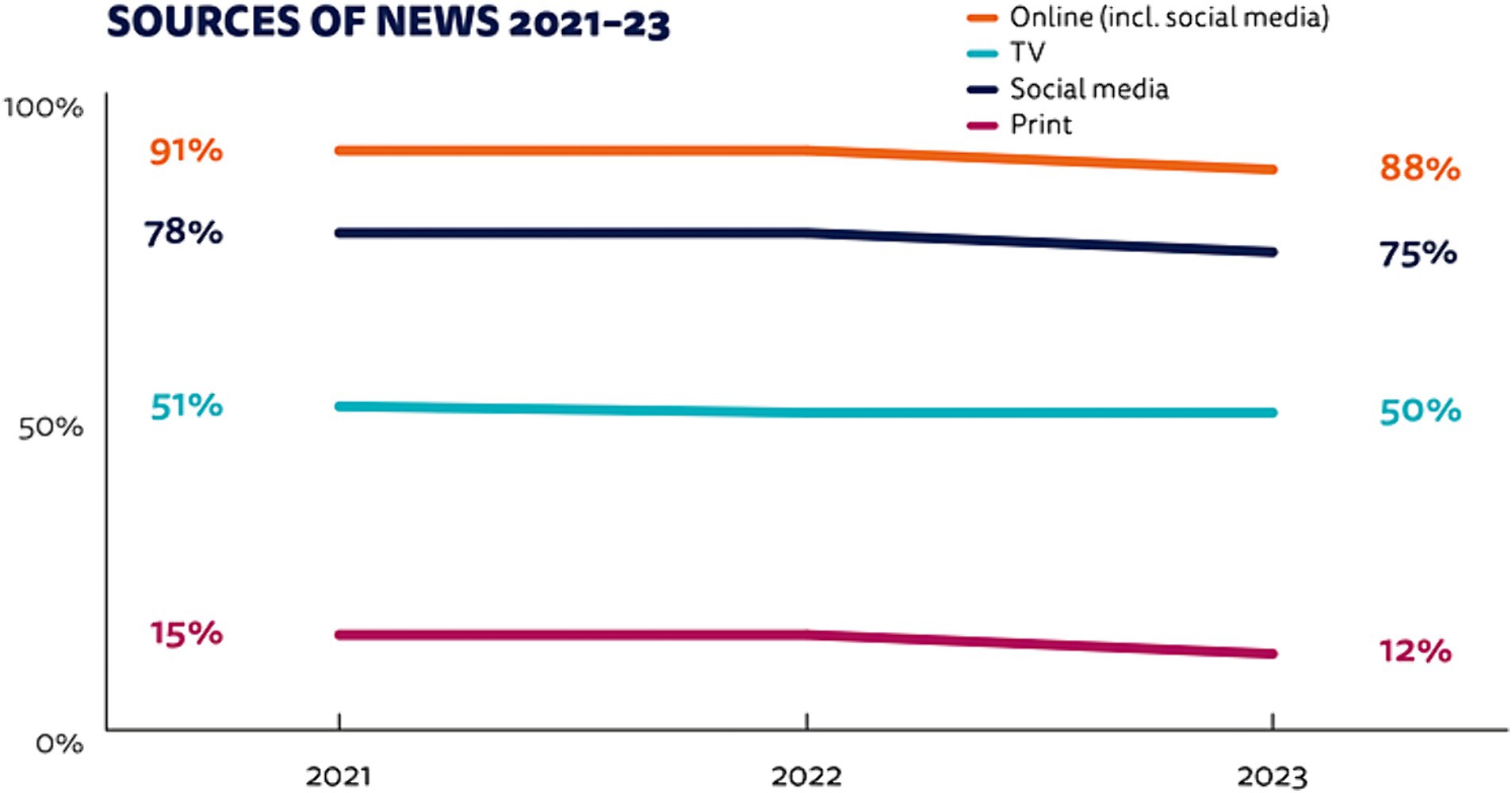

Advancement in digitalization in Southeast Asia has led to rising concerns over disinformation. Among the advancements is the use of social media, defined in this policy brief as “…the set of interactive internet applications that facilitate (collaborative or individual) creation, curation, and sharing of user-generated content” (Davis, 2015). Figures show that 68% of the region is a social media user, and most citizens now rely on the use of such platforms as sources of news (Smith and Perry, 2022; Newman et al., 2023). In a recent study assessing Internet use in Southeast Asia, Kemp concluded that 16 to 24-year-olds spend an average of 10 h per day on the Web (Kemp, 2021). This causes the risk of fake news to be prominent within the region.

The additional risk of a rising dependence upon the internet corresponds to the unique Southeast Asian disinformation landscape. Several concerns include the lack of digital literacy, non-democratic governance (several of the Southeast Asian states), lack of inter-government coordination in responding to global tech giants, and diverse sets of media outlets available (Martinus, 2023). Sombatpoonsiri argued the problem of legislative opportunism, in which the non-democratic governments in the region (Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam) have hijacked information to control the digital environment, further eliminating public trust over news (Sombatpoonsiri and Luong, 2022). For Myanmar, it was argued that such fake news was spread to advance government efforts in kindling ethnic divisions, furthering hatred and divisions among the society (Guardian, 2018). In Malaysia, anti-Chinese racism slurs were rampant during the early months of COVID-19, creating confusion among the communities (Tham and Omar, 2020). In Singapore, disinformation has led to rising scams, reaching 14,349 in mid-2022 (Chua, 2022), which significantly impacted the lower and middle classes within the nation. Despite the differences Southeast Asian states share, fake news leads to adverse outcomes for the region.

2 The status quo of Southeast Asian and ASEAN responses

Southeast Asian states have adopted different measures to respond to fake news and disinformation, albeit actively pursuing active solutions. This dynamic is linked to the vast global regulatory moves questioning the status of self-regulated Big Tech companies, especially in the West (Luong, 2022). Consequently, Southeast Asian states have introduced different legislative measures to curtail such practices. Unfortunately, perhaps connected to the lack of democratic practices in many parts of the region, such measures have been perceived to accelerate state controls toward what the public can access (Martinus, 2023).

Policy manifestations aimed to minimize the spread of disinformation by the media have diverged. For Indonesia, a criminal code introduced in December 2022 paved the way to criminally charge individuals spreading hatred and misinformation about the president, vice president, and state ideology (Newman et al., 2023). To regulate internet services, Indonesia’s Ministry of Information and Communication reinforced a law obliging foreign internet services to register with the authorities to counter information that undermines public order (Luong, 2022). Similarly, Thailand launched the ‘Anti-Fake News Centre’ to suppress fake news, which led to the focus on censoring harmful COVID-related news between 2020 and 2022 (Chongkittavorn, 2023). For Singapore, the measures have been strict. By the 2019 Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), disseminators of false information can be penalized and face prosecution (Chongkittavorn, 2023). The vast and divergent measures taken by individual Southeast Asian states represent the differences in disinformation landscapes and context-specific vulnerabilities of the states. Thus, they embark on countering efforts on a non-equal footing.

But how has ASEAN responded collectively? At the normative level, progress has been visible. In 2023, under the leadership of Indonesia, ASEAN disseminated the ‘ASEAN guideline on the management of government information in combating fake news and disinformation in the media.’ The guideline is a conclusion of the past efforts of ASEAN members in determining the harm of such disinformation to the domestic population. In doing so, it considers past regulations aimed to minimize harm, advance digital literacy, promote the peaceful use of social media, and counter the harmful effects of COVID-19-related news (ASEAN, 2023a). ASEAN’s normative stance can be attributed to Annex 5, agreed upon by Southeast Asian states in 2018, which discusses the nexus between fake news and the monetary benefits of disseminating such information (ASEAN, 2018). At present, ASEAN Ministers Responsible for Information (AMRI) have continuously discussed measures to advance ASEAN members’ resilience in countering the problem (ASEAN, 2023b). However, this has not exceeded the level of normative agreements. The following section provides several policy options that can act as technical guidelines to counter fake news and media disinformation, along with the impediments to such tangible collaborative efforts in Southeast Asia.

3 Countering fake news and disinformation through ASEAN: policy options and potential implications

3.1 Substantively determine what are fake news and disinformation

The normative agreements shared within ASEAN have provided the legal grounds for regional collaboration in countering disinformation. However, ASEAN states need to agree substantively on what fake news and disinformation consist of in the region. This can be done by identifying intersecting concerns and vulnerabilities that Southeast Asian states share and the possible clashes of approaches. In doing so, ASEAN can strategically position how the organization can resolve common problems related to the issue and initiate tangible steps to respond. An example is the EU’s common threat perception of Russian disinformation campaigns within Europe. Vis-à-vis the rising number of fake news and disinformation, the EU responded by establishing the East StratCom Task Force in 2015, which focuses on identifying related campaigns and undergoing collaborative efforts to counter them.

However, this policy option is only feasible once a common threat perception is agreed upon. Considering the diverse political and demographic landscape of Southeast Asian states, this may be a difficult task. Thus, a policy implication is the possible disunity of opinions in identifying the vulnerabilities and challenges member states face regarding fake news. This policy brief identifies external disinformation as the significant challenge in adopting this policy. The Yusof Ishak Institute’s ISEAS recently identified the growing number of Russian cyber actors spreading stories to justify the Ukrainian attacks in 2022, with the propaganda mostly present in Singapore and the Philippines (Cheong, 2022). In such cases, adopting a unified policy to respond would be difficult. ASEAN countries are dominated by states adopting non-alignment foreign policies and have been polarized by different ideologies. It struggles to balance major power influences infiltrating the region, and externally constructed disinformation will cause greater polarization among ASEAN members.

To be practicable, the best course of action is to define fake news and disinformation moderately. ASEAN should focus on matters that have proven to be of concern among member states. Small-scale engagements that are focused on specific issues, such as terrorism and COVID-related hoaxes, to name a few, have been a common theme of disinformation shared among the states. Starting with a moderate level of determination of what fake news consists of, it cultivates the needed atmosphere of cooperation that allows for greater collaboration.

3.2 Elevating the issue of fake news and disinformation into a non-traditional security issue.

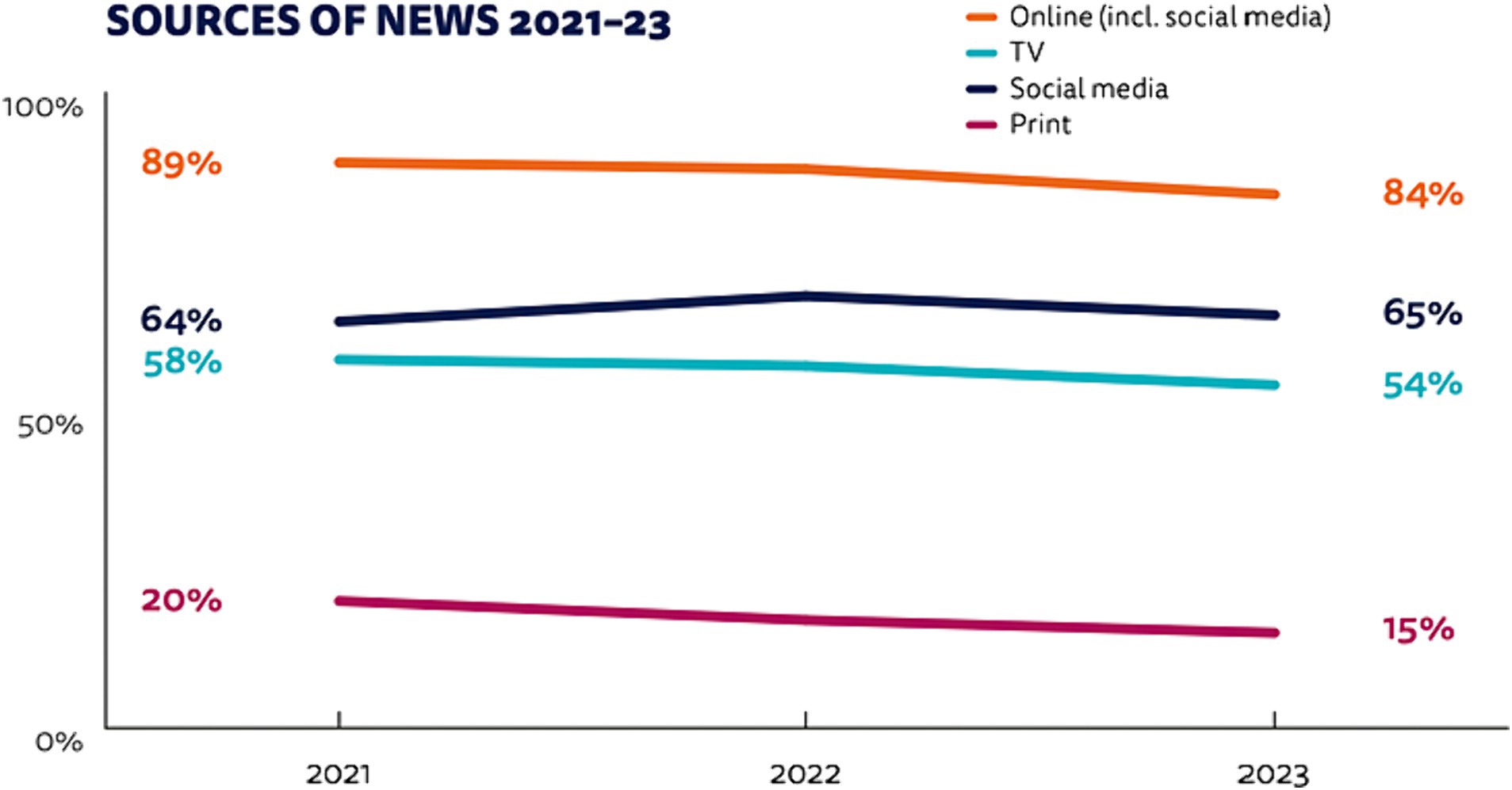

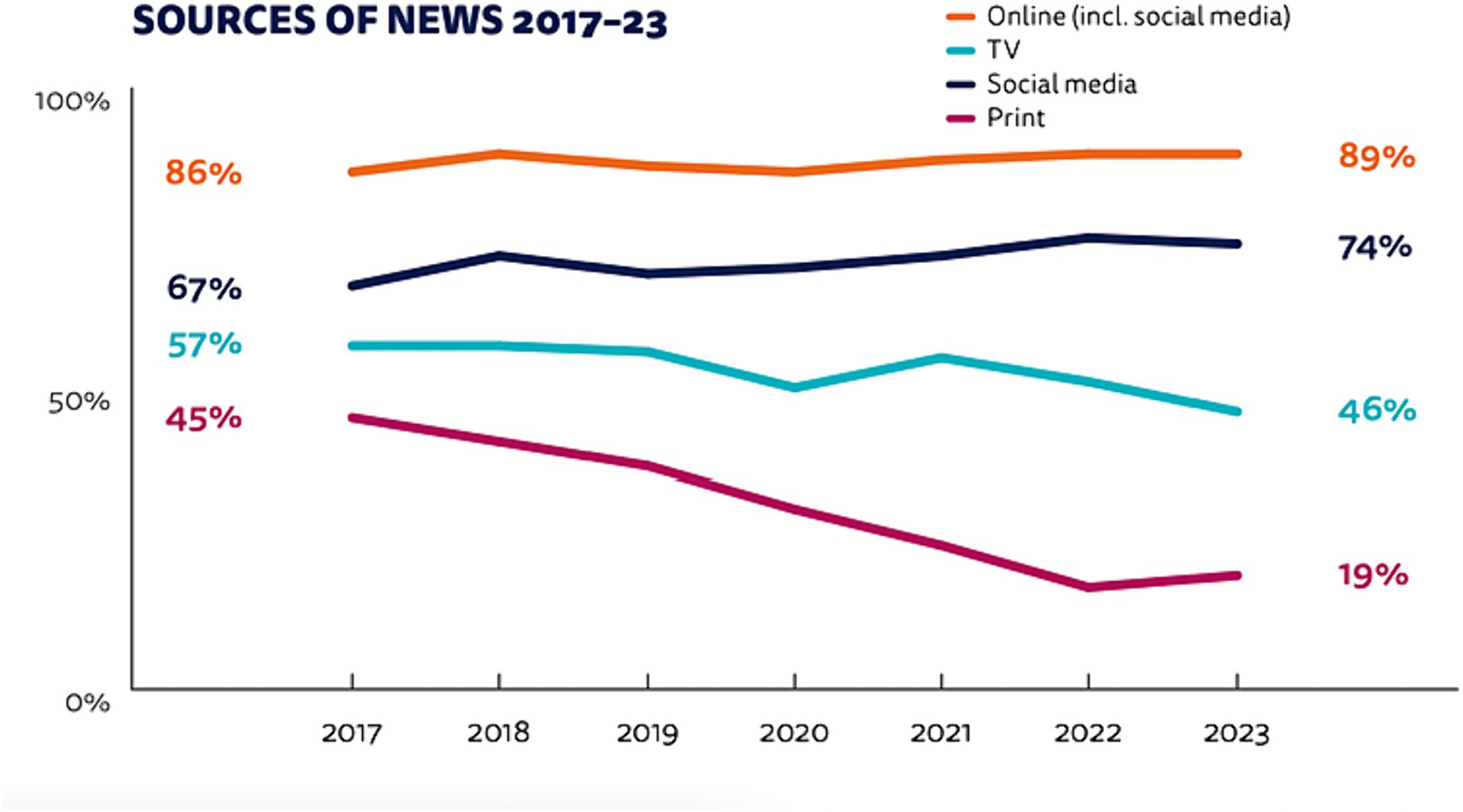

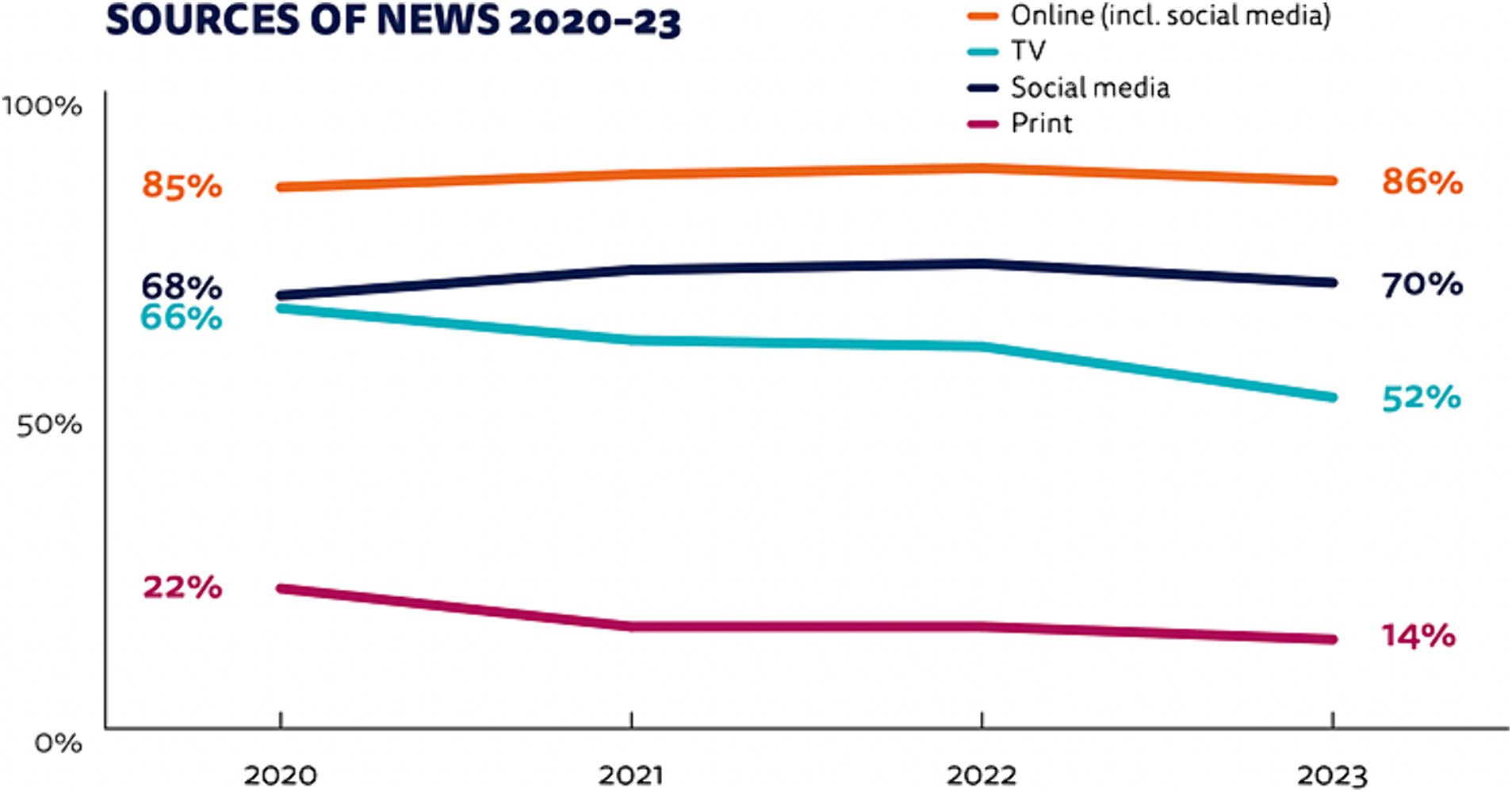

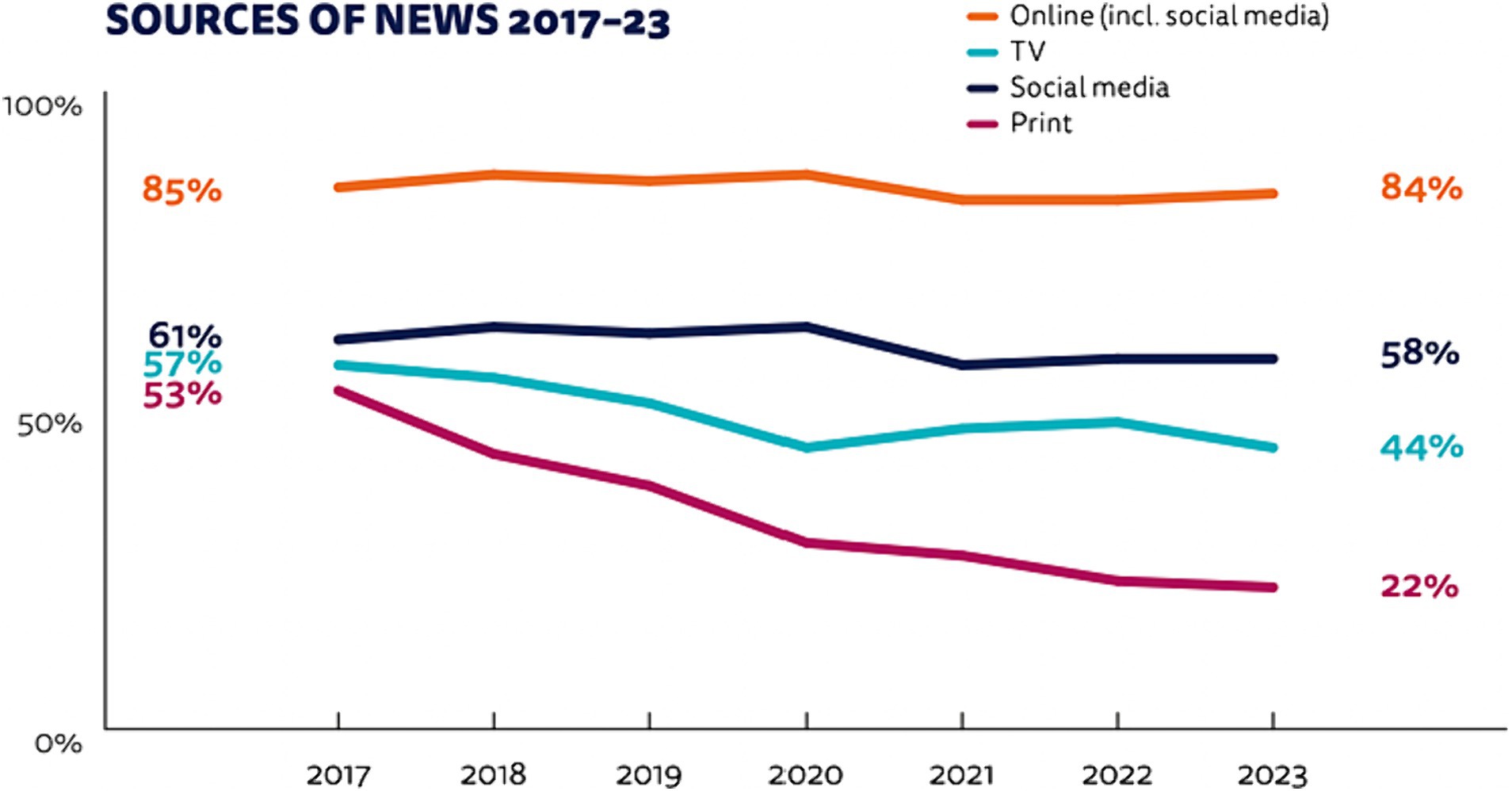

One of ASEAN’s advantages is its ability to foster dialogue and cooperative relations through its vast number of forums. Not only do all ministries within ASEAN have their own ministerial meetings in fields such as security, but cooperation is also promoted with ASEAN’s Plus partners, the ASEAN Regional Forum, and the East Asian Summit. A growing recognition of fake news and disinformation can only be adequately addressed once the issue is elevated to a non-traditional security threat. As for the current status quo, this matter is mainly discussed among AMRI. Redefining fake news and disinformation as a non-traditional security threat would allow several of ASEAN’s flagship external forums to help Southeast Asian states find common ground in countering the growing issue. As cases in Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, and Indonesia have shown, the issue falls under this category due to the deepening of social divisions it establishes (Figures 1–5).

The policy implication of mainstreaming fake news and disinformation into ASEAN meetings and mechanisms allows better collaboration between defense and intelligence agencies. It is predicted that Southeast Asian states would echo their current approaches to collectively be considered within ASEAN, including firewalls, surveillance, and censorship measures. What is unique about this policy option is that it does not aim to impose a single framework to respond to the emerging crisis. As a non-traditional security threat, countering disinformation will lead to states having different approaches to counter the threat. As in the case of Illegal, Unregulated, Unreported Fishing, illicit drug smuggling, and terrorism in Southeast Asia, there is a growing acceptance among ASEAN members and partnering states that the importance of state sovereignty and state-determined solutions take center-stage in how ASEAN will respond to the non-traditional threats.

Consequently, this allows the divergent solutions adopted by Southeast Asian states to be maintained, with better exchanges of information and best practices intra-ASEAN and with ASEAN’s dialog partners. This policy option considers that enforcing a single approach leads to unwanted accusations and may negatively impact diplomatic relations. Southeast Asian states need a policy option in tune with ASEAN’s core philosophies of non-interference, non-interventions, and respect for state sovereignty.

3.3 Establish an ASEAN-centered fast-checking network

With the growing use of social media and how the platform has been the primary news source for Southeast Asian society, ASEAN can contribute to establishing a regional ASEAN-centered fast-checking network. As seen in the following figures, there is a growing dependency on social media; thus, government stakeholders need to be wary of this trend and counter the possible disinformation that may arise on such platforms. A fast-checking network would consist of an organization responsible for determining the accuracy of news disseminated on various online platforms within a state’s borders. This policy option also considers the unique political landscape of Southeast Asian states and the importance of respecting the different approaches (surveillance, firewalls, censorship, legal action) chosen by ASEAN members for its domestic border. Aligned to the recently published ASEAN guidelines on countering disinformation, this policy brief echoes the following steps to guide ASEAN’s fast-checking network: (1) cross-reference to research, (2) consult experts, (3) check sources, (4) cross-checking of online information (ASEAN, 2023a). This policy option also allows the introduction of specialized tools to identify false news and disinformation.

A possible policy implication is the principles held among ASEAN members. Therefore, a solution is to adopt common goals of promoting accuracy, transparency, and impartiality. Doing this further considers the disparity of resources between Southeast Asian states. It allows state policymakers to apply measures corresponding to their available resources if they align with the pre-defined principles. Referencing the International Fact-Checking Network, it is also pivotal to consider the following principles: (1) impartial information without bias and political influences, (2) disclosure of information sources in fact-checking, (3) transparency over the sources of funding, and (4) transparency over the methods of fast-checking.

4 Actionable recommendation: moderate level changes

This policy brief recommends adopting all three policy options at a moderate level. A commonly observed strength (some argue weakness) of ASEAN is the principles of non-interference that its members hold. Consequently, rapid changes are not expected to occur, especially on matters that could cause greater polarization among its members.

In adopting what fake news and disinformation consist of, elevating to a non-traditional security threat, and establishing an ASEAN-centered fast-checking network, this policy brief perceives that all measures are feasible to be adopted. However, flexibility in the timeframe of adoption is needed. Unlike authoritative regional organizations with common threat perceptions, ASEAN consists of highly divergent Southeast Asian states that do not even share a common ideology among its members. Consequently, all measures that aim to establish a new network or elevate the threat status of an issue need to be introduced, discussed, and implemented without a strict timetable to allow greater flexibility for ASEAN members to decide the best course of action. As mentioned previously, there is a great disparity of resources between ASEAN members, and the adoption of threat perceptions is carefully constructed in order to maintain non-alignment foreign policies. Therefore, the following steps are recommended:

1. More discussions on the dangers of fake news and disinformation are to be held within ASEAN forums. Considering the past experiences that Southeast Asian states have faced, it should not be difficult for ASEAN members to collectively agree on the importance of tackling such growing concerns.

2. With the convergence of interests to counter disinformation, the next step is to elevate the issue into a non-traditional security threat. Unlike traditional security threats, countering non-traditional threats allows for different government approaches to be maintained without the enforcement of a single approach, making it feasible for Southeast Asian states to adopt surveillance, legal prosecutions, firewalls, and censorship measures,

3. The formal establishment of an ASEAN-centered fast-checking network is the policy manifestation of the converged interest to counter fake news and disinformation.

5 Conclusion

The growing number of fake news and disinformation is concerning for ASEAN. Southeast Asia, consisting of demographic differences with rising social media and online platform dependence to access information, is highly vulnerable to disinformation. This serves as a critical problem that may deepen social divisions in an already highly vulnerable group of societies. In the past, governments across different Southeast Asian states adopted strict measures by implementing censorships, legal prosecutions, and surveillance. This policy brief suggests several steps that ASEAN could conduct as Southeast Asia’s regional organization to collectively tackle the issue.

It argues for adopting a common understanding of fake news and disinformation actions, elevation to a non-traditional security threat, and establishment of an ASEAN-centered fast-checking network. Adopting these measures ensures that states can continue adopting measures that suit member states’ political systems and concerns. Further, it allows a multi-pronged approach that does not impose a single approach to counter the issue, as has been the concern of ASEAN in the past several decades.

Author contributions

BP: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ASEAN. (2023a). ASEAN guideline on management of government information in combating fake news and disinformation in the media. Jakarta: Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

ASEAN. (2023b). Joint media statement 16th conference of the ASEAN ministers responsible for information & 7th conference of the ASEAN plus three ministers responsible for information. Jakarta: Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

ASEAN (2018). Framework and joint declaration to minimise the harmful effects of fake news. Jakarta: Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Cheong, Darren. (2022). ‘Unpacking Russia’s twitter disinformation narratives in Southeast Asia’. FULCRUM: Analysis on Southeast Asia. Available at: https://fulcrum.sg/unpacking-russias-twitter-disinformation-narratives-in-southeast-asia/

Chongkittavorn, Kavi. (2023). ‘Combatting fake news the ASEAN way’. Economic research institute for ASEAN and East Asia. Available at: https://www.eria.org/news-and-views/combatting-fake-news-the-asean-way/.

Chua, Nadine. (2022). ‘$227.8m lost to top 10 scams in first half of 2022, as overall crime rises by 36%’. The straits times. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/2278m-lost-to-top-10-scams-in-first-half-of-2022-as-overall-crime-rises-by-36.

Davis, J. L. (2015). “Social Media” in The international Encyclopedia of political communication. ed. G. Mazzoleni (New York: Wiley Publisher), 1.

Guardian. (2018). ‘Myanmar Army fakes photos and history in sinister rewrite of Rohingya crisis’. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/31/myanmar-army-fakes-photos-and-history-in-sinister-rewrite-of-rohingya-crisis.

Kemp, Simon. (2021). ‘The digital habits of SE Asia’s young adults’. DataReportal – Global digital insights. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-youth-in-south-east-asia-2021.

Luong, Dien. (2022). ‘Internet blocks Won’t solve Southeast Asia’s fake-news problem’. Nikkei Asia. Available at: https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Internet-blocks-won-t-solve-Southeast-Asia-s-fake-news-problem.

Martinus, Melinda. (2023). ‘Can ASEAN mitigate fake news in Southeast Asia?’. Fulcrum: Analysis on Southeast Asia. Available at: https://fulcrum.sg/aseanfocus/af-can-asean-mitigate-fake-news-in-southeast-asia/.

Newman, Nic, Fletcher, Richard, Eddy, Kirsten, Robertson, Craig T., and Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis. (2023). ‘Reuters institute digital news report 2023 ’. London: Reuters.

Smith, R. B., and Perry, M. (2022). Fake news and the pandemic in Southeast Asia. Austr. J. Asian Law. 22, 131–154.

Sombatpoonsiri, Janjira, and Luong, Dien Nguyen An. (2022). Justifying digital repression via “fighting fake news”: A study of four southeast Asian autocracies. Eds. Choi Shing Kwok and Ooi Kee Beng (Singapore: ISEAS: Yusof Ishak Institute).

Tham, Jia Vern, and Omar, Nelleita. (2020). ‘Like a virus: how racial hate speech looks like in Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic’. The Centre Malaysia. Available at: https://www.centre.my/post/how-covid-19-influencing-racial-hate-speech-malaysia

Keywords: fake news, disinformation, ASEAN, Southeast Asia, news

Citation: Putra BA (2024) Fake news and disinformation in Southeast Asia: how should ASEAN respond? Front. Commun. 9:1380944. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1380944

Edited by:

Pradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaReviewed by:

Deepak Vaishnav, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaMiren Gutierrez, University of Deusto, Spain

Copyright © 2024 Putra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bama Andika Putra, bama.putra@bristol.ac.uk; bama@unhas.ac.id

Bama Andika Putra

Bama Andika Putra