- Department of German Language and Literature I, Linguistics, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

German has two demonstrative pronoun series: the short form der, die, das, and the long form dieser, diese, dieses. Both forms can be used anaphorically, and they contrast with the personal pronouns er, sie, es in that they refer to an antecedent that is less prominent at that point in the discourse when the discourse provides different potential antecedents. Demonstrative pronouns are typically used in the preverbal position in a German sentence, i.e., the topic position. Thus, they are assumed to be topic shifters (from a non-topical antecedent to the topical argument in the current sentence). However, der can be repeated, yielding topic chains, thus referring back to a topical antecedent, while this is not the case for dieser. In this article, we argue that der and dieser both contribute to topic management, but they do this in different ways: der is a marker of a sentence topic, while dieser is a marker of discourse topic shift. We present the results of two experiments that compare the use of personal pronouns with either demonstrative pronoun manipulating sentence topic or discourse topic. First, both experiments show that the personal pronoun is not sensitive to either type of topichood of its antecedent. Second, Experiment 1 shows that both demonstrative pronouns prefer a context where discourse topic and sentence topic are shifted. Third, Experiment 2 shows that only dieser prefers a context with a shifted discourse topic, but der is not sensitive to discourse topichood alone. We take the results as supporting our claim that the two demonstratives have different discourse functions: der marks a sentence topic, while dieser is a shifter (and marker) of the discourse topic.

1 Introduction

Referential management in discourse is primarily guided by the use of referential expressions, e.g., personal pronouns, definite noun phrases, and proper names. Recent studies also focus on the anaphoric function of demonstrative pronouns, in particular in comparison to personal pronouns. Demonstrative expressions are primarily used as deictic expressions in order to refer to objects in the actual situation. Beyond their deictic function, they have various other functions, including a broad range of functions in discourse structuring (Himmelmann, 1996; Diessel, 1999; Doran and Ward, 2019). Current research compares the anaphoric behavior of demonstrative pronouns with that of personal pronouns. In contexts with two or more potential antecedents, demonstratives refer to the less prominent antecedent, i.e., the non-subject, the non-topical, the non-agent, and often the most recent antecedent, while personal pronouns tend to refer to the subject, the topic and agent argument, and the first-mentioned antecedent (Kaiser and Hiietam, 2004; Kaiser and Trueswell, 2008; Hemforth et al., 2010; Kaiser, 2011; Çokal et al., 2018).

German has two demonstrative pronouns, the short (or unmarked) form der, die, das and the long (or specialized) form dieser, diese, dieses, both of which show very similar behavior in their anaphoric use if compared to the personal pronoun er, sie, es in contexts with more than one antecedent. Demonstrative pronouns access the less prominent antecedent and make it more prominent; thus, they function as topic shifters (Weinrich, 1993/2007; Kaiser, 2011; Schumacher et al., 2015; Bader and Portele, 2019). However, both demonstrative pronouns can also be used in contexts with only one appropriate antecedent, which they promote to a topic (Weinrich, 1993/2007; Abraham, 2002; Ahrenholz, 2007). It is not discussed whether they differ in how they do this. One interesting observation is that the demonstrative der, allows for topic chains consisting of repeated uses of der, while the demonstrative dieser does not allow for such chains. It is felicitously used only once in a referential chain (Abraham, 2002; Ahrenholz, 2007). We think that this behavior follows from the difference between the short demonstrative der and the long demonstrative dieser in their discourse function: der marks a sentence topic, which makes it compatible with a local topic shift. Dieser, on the other hand, is a discourse topic shifter, i.e., it signals that a new or familiar discourse referent becomes the new discourse topic. Since a discourse topic is understood as a topical element for a longer discourse span, a repetition of dieser in adjacent sentences is not felicitous. In order to test these hypotheses, we conducted two experiments: In both experiments, we created small discourses with only one suitable third person singular referent. In Experiment 1, we manipulated both discourse and sentence topic and tested the acceptability of the two demonstrative pronouns. In Experiment 2, we only manipulated the discourse topic and kept the sentence topic stable in order to test the discourse structural function of both demonstratives.

In the following, we initially present more information on demonstrative pronouns in German and their anaphoric semantics as well as their discourse function. We then formulate our hypotheses on the different discourse functions of the two demonstratives based on empirical observations in the recent literature. This is followed by our two experiments, the discussion, and our conclusion.

1.1 Demonstratives in German

German—like every other language—has demonstrative expressions, which generally have the function to direct attention to an object or raise the prominence of a discourse referent (Himmelmann, 1997; Diessel, 1999). We will focus on the two most important demonstratives in German: the unmarked form der, die, das and the long and specialized form dieser, diese, dieses. The unmarked form der is also the source for the definite article, the relative pronoun, and the resumptive pronoun. The specialized form allows first-mentioned uses, i.e., recognitional and indefinite uses of demonstrative noun phrases (Himmelmann, 1997; Deichsel, 2015). Both demonstratives can be used as determiners in demonstrative noun phrases or complex demonstratives (der Junge ‘that boy,’ dieser Junge ‘this boy’) or as pronouns for animate or inanimate referents (unlike English this and that). The demonstrative noun phrase der Junge ‘that boy’ cannot be easily distinguished from the definite noun phrase der Junge ‘the boy,’ as most forms in the gender-case-number paradigm of the definite article and the unmarked demonstrative are identical. The unmarked demonstrative der does not express locational information, and the demonstrative dieser signals proximity only in very well-defined contexts. It is, generally used without locational information (Weinrich, 1993/2007; Zifonun et al., 1997; Weinert, 2007; Wöllstein and Die Dudenredaktion, 2022). Demonstrative determiners in demonstrative noun phrases are assigned the following three functions. First, they select one element from a set of similar entities and thus express an anti-uniqueness condition, as evidenced by the infelicitous *this moon (Bisle-Müller, 1991; King, 2001; Wolter, 2006; Bosch and Umbach, 2007). Second, they are assumed to be topic shifters, i.e., they promote a non-topical referent in the antecedent sentence to a topical one in the current sentence (Weinrich, 1993/2007; Zifonun et al., 1997; Diessel, 1999; Bosch and Umbach, 2007). Third, they signal topic continuity in the sense of Givón (1983), i.e., they signal that a topic is and will be continued along a larger span of discourse. This is best documented by the forward-looking function of indefinite demonstratives, as in Then I met this guy at the bar (Prince, 1981; Gernsbacher and Shroyer, 1989), which is also a function of the German specialized demonstrative dieser (Deichsel, 2015). In this article, we focus on pronominal demonstratives in their anaphoric use. We assume that some of their functions should intersect with the functions of the corresponding determiners.

1.2 Anaphorically used demonstrative pronouns

Demonstrative pronouns are typically investigated in comparison to personal pronouns. They differ from personal pronouns in their anaphoric use in that in ambiguous contexts, i.e., in contexts with more than one antecedent, they access the less prominent antecedent, while personal pronouns prefer the prominent antecedent. We understand prominence (or salience) as a structural property of the discourse that is composed of several sub-scales. A prominent unit is defined such that (i) it stands out with respect to other units of the same type, (ii) it attracts more operations than other elements, and (iii) it might change over time (Himmelmann and Primus, 2015; von Heusinger and Schumacher, 2019).

The demonstrative der has been extensively investigated using offline as well as different online methods; Bosch et al. (2007) and Weinert (2007) provide corpus data. Schumacher et al. (2016) and Bader and Portele (2019) use acceptability judgment tasks, sentence completion experiments, or forced-choice tasks. Bosch and Umbach (2007) provide results from self-paced reading, and Ellert (2013) and Schumacher et al. (2017) from visual world paradigm studies. Schumacher et al. (2015) and Repp and Schumacher (2023) report on ERP studies. The general view from all these different studies is that der refers to less prominent antecedents, and er refers to more prominent antecedents. Personal pronouns tend to refer to the subject/the first/the topical and highly agentive antecedent, while demonstrative pronouns refer to the non-subject, the more recent, the non-topical, and the less agentive antecedent. This preference is strong for demonstrative pronouns, while the personal pronouns are more flexible (Kaiser, 2011; Schumacher et al., 2016; Bader and Portele, 2019).

The demonstrative dieser has been less intensively studied, primarily using offline studies: Abraham (2002), Ahrenholz (2007), Weinert (2007) report on corpus studies, Fuchs and Schumacher (2020) from sentence completion tasks, Patil et al. (2020, 2023) and Patterson and Schumacher (2021) on forced-choice and acceptability judgment tasks. Summing up their findings, dieser behaves very similarly to der: in ambiguous contexts, i.e., in contexts with two or more antecedents, both demonstratives refer to the less prominent antecedent. Prominence parameters include grammatical role (Bosch et al., 2007), linear position of antecedents (Bosch and Hinterwimmer, 2016), topichood (Bosch and Umbach, 2007), and thematic role (Schumacher et al., 2016; Bader et al., 2022). Most studies do not find significant differences between der and dieser. Fuchs and Schumacher (2020, p. 207) report a numerical difference between der and dieser in contexts where they refer to less prominent antecedents: der establishes a slightly longer referential chain than dieser, mirroring the assumption of Weinrich (1993/2007) that dieser functions as a marker for introducing a new discourse topic. Bader et al. (2022, p. 415) do not find any structural or semantic differences between der and dieser, but speculate that der allows for an “evaluative” interpretation, which is not available for dieser. This is experimentally confirmed by Patil et al. (2023), who find that der is acceptable in an evaluative context even when its antecedent is highly prominent (topical), whereas dieser is not affected by evaluation and is always rated low with such an antecedent. Patil et al. (2023) use these findings to build upon a theory (cf. Hinterwimmer and Bosch, 2016, 2018, in turn developing an account by Bosch and Umbach, 2007) that der is sensitive to perspective-taking, and that it avoids the most prominent perspective-taker. Hinterwimmer (2020) generalizes this account by assuming that perspective-takers such as narrators in texts are also discourse referents, and that thus the behavior of der simply falls out from it, avoiding the most prominent discourse referent. Dieser, Patil et al. (2023) argue, is not sensitive to perspective-taking, but also avoids the most prominent discourse referent, which is then the discourse topic. Patterson and Schumacher (2021) found no significant difference between the use of der and dieser in forced-choice and acceptability judgment tasks of ambiguous contexts with three antecedents, but both showed a certain preference for the last mentioned antecedent, supporting the claim of Zifonun et al. (1997) for dieser. Finally, Patil et al. (2020) found register differences between der and dieser, such that dieser tends toward more formal, and der toward more informal, language.

Before we move on to how the German demonstratives interact with discourse structure, we will first discuss the notion of topic itself in some more detail and lay out the idea that it concerns at least a more local and a more global strand of referential management.

1.3 Topics

Topic is one of the central concepts of information structure in linguistics. There are at least two different types of topics in the literature: sentence topic and discourse topic. Following Reinhart (1981), a sentence topic or aboutness topic is defined as the referent that a sentence is about. Recognizing that essentially the same propositional content can be realized via a number of sentences with different topics, Reinhart defines the aboutness relation such that a sentence topic provides instructions about which discourse referent the proposition denoted by a sentence should be stored under in the discourse representation. The constituents denoting topic referents underlie certain restrictions. In line with the aboutness definition requiring a well-defined header, i.e., a discourse referent, under which a proposition is stored, many languages, including English and German (cf. Frey, 2005), only allow definites or specific indefinites as topics. In many accounts, sentence topic referents also have to be given or at least be weakly familiar (Roberts, 2011). Correspondingly, there are also topicless, or thetic (Kuroda, 1972), sentences that are not about any one referent. The notion of aboutness is pragmatic, i.e., a sentence can only be said to have a certain topic within a given context (Reinhart, 1981). However, many linguistic devices have been identified cross-linguistically that correlate with sentence topichood or that have been called topicalizing constructions, even though they do not categorically mark topical constituents in accordance with the context-dependent nature of aboutness. Topicalizing constructions have been shown to have differing, language-specific, felicity conditions (cf. Frey, 2005; Roberts, 2011). The most persistent crosslinguistic tendency seems to be to place topical constituents sentence- or utterance-initially (Roberts, 2011). Syntactically, subjects are often sentence topics, and semantically, agents often are (Givón, 1983). Since topics are often given, they are also often expressed via (zero) pronouns (Givón, 1983; Poesio et al., 2004). Specifically for German, Frey (2005) shows that a constituent in the prefield, i.e., placed before the finite verb in a main clause, is very compatible with a topical interpretation. We therefore assume that German sentences in which an initial constituent (in the prefield) is a subject and an agent and that can plausibly be interpreted as being about the referent denoted by that constituent in a given context will normally be interpreted as having this referent as their sentence topic. Conversely, we assume that referents expressed via non-initial, non-subject constituents will be less likely to be interpreted as sentence topics.

The other relevant type of topic is that of the discourse topic. As the name indicates, the discourse topic has a broader, more global scope than the sentence topic, which is local to the sentence and its immediate context. The discourse topic plays a role in establishing coherence between larger chunks of discourse; it is what an entire segment of (i.e., a paragraph) a discourse is about (cf. Tomioka, 2021). Roberts (2011) equates the discourse topic with the question under discussion (QUD, Roberts, 1996/2012), i.e., the structuring of discourse along hierarchically ordered implicit questions. The discourse topic aids in maintaining a sense of thematic continuity (Givón, 1983) across several sentences. Unlike sentence topics, discourse topics do not need to correspond to a single constituent in any given sentence and can be more abstract (Reinhart, 1981). A sequence of sentences can have changing sentence topics but maintain a single discourse topic throughout. However, if in such a discourse sequence each individual sentence or utterance has the same sentence topic throughout, it makes sense to take this topical referent as the discourse topic as well (van Dijk, 1977). We operationalize discourse topic in our experiments in two senses. For the continuing condition (see below), we operationalize it in the sequential sense: we assume that participants will interpret short discourses consisting of several sentences as being about a certain discourse topic referent if that referent is consistently realized as sentence topic in these sentences. For the shifting condition, we operationalize it in the more abstract way, so that we initially introduce an event that the paragraph is about, and then subsequently adduce further information about it.

1.4 Demonstrative pronouns and discourse structure

Weinrich (1993/2007), Abraham (2002), Weinert (2007), and Ahrenholz (2007) focus on the discourse function of demonstrative pronouns in German. Here we initially summarize their analyses before then proposing a refinement below.1 Weinrich (1993/2007) observes that personal pronouns are used in order to continue a topical (in his terminology, a “thematic”) antecedent, often the subject of the previous sentence. Demonstrative pronouns, however, are typically linked to a non-topical (or “rhematic”) antecedent, which is then promoted to a prominent, i.e., topical, referent. This is evidenced by the observation that demonstrative pronouns have a much stronger preference than personal pronouns to occur in an initial or preverbal position (cf. Weinert, 2007, p. 8–9), the favorite topic position in a German sentence (but not the only possible position for a topic; see Frey, 2004). In the following example from Weinrich (1993/2007, p. 381), the lake Wannsee is introduced in the first sentence and then picked up by the direct object den in the preverbal position.

(1) A: Wenn Sie in Berlin gewohnt haben, kennen Sie natürlich auch den Wannsee.

B: ja, den kenn ich von den vielen Sonntagsauflügen.

A: If you have lived in Berlin, you’ll of course know the Wannsee.

B: Yes, I know den from my many Sunday outings.

The demonstrative den in the second sentence refers back to the only suitable referent, den Wannsee; according to Weinrich, and it here promotes the referent to the topical one in the current sentence. Abraham (2002) couches this behavior of demonstrative pronouns in terms of Centering Theory (Grosz et al., 1995) and formulates a modified pronoun rule for demonstratives, namely that they must not refer to a topical antecedent, while personal pronouns typically refer to such a topical antecedent. Abraham (2002, p. 461) aims to illustrate this behavior in (2) via sentences with two competing antecedents.

(2) a (S1:) Hans1 traf Alfon2. (S2:) Der2 trug einen Regenmantel. (S3:) Er2 war bleich im Gesicht.

Hans1 met Alfons2. Der2 wore a raincoat. He2 had a pale face.

b Hans1 traf Alfons2. Der2 trug einen Regenmantel. *Der2 fror trotzdem.

Hans1 met Alfons2. Der2 wore a raincoat. *Der2 was freezing nonetheless.

c Hans1 traf Alfons2. Er1 trug einen Regenmantel. Er/*Der1/2 fror trotzdem.

Hans1 met Alfons2. He1 wore a raincoat. He/Der1/2 was freezing nonetheless.

The demonstrative der refers to the non-topical Alfons in the first sentence and is again taken to promote the referent to a topical status. The personal pronoun er in S3 can then refer to this topical antecedent, cf. (2a). The infelicitous use of der in S3 in (2b) is intended to illustrate that a demonstrative (here in particular der) can only access a non-topical element, and the topical chain of Hans—er—er/*der in (2c) is intended to illustrate that the demonstrative cannot stand in a topical chain. Weinrich (1993/2007), Abraham (2002), and Weinert (2007) focused on the behavior of the unmarked demonstrative der, but assumed that the specialized demonstrative dieser behaves similarly.

Abraham (2002) concludes from the topic conditions that demonstrative pronouns always have to refer to a full noun phrase antecedent, but not to personal pronouns as they are part of topical referential chains. However, Weinrich (1993/2007, p. 382) already provided examples of der-topic chains from a short dialogue in a literary text, contradicting Abraham’s claim (Alfred Döblin, Berlin Alexanderplatz, Third Book: 127):

(3) “Kopp ist total ausgeschlossen. Der ist doch Athlet, Schwerarbeiter, der war erstklassiger Möbeltransportör, Klaviere und so, bei dem schlägt es nicht auf den Kopf….”

“Kopp is totally out of the question. Der is an athlete, a hard worker, der was a first-class furniture transporter, pianos and all that, it does not hit dem on the head….”

In (3), the referent Kopp is introduced in subject position in the first sentence as the only referent and then picked up with the demonstrative der in the second sentence, but also in the third and fourth sentences. While this example clearly illustrates that der-topic chains with repeated use of the demonstrative are possible, the alternative use of the demonstrative dieser in such a context is not possible. Repp and Schumacher (2023, p. 05) provide a very similar example (4) from the coming-of-age novel Tschick by Herrndorf (2010, p. 158), which tries to mimic informal language (our italics; see also Hinterwimmer, 2020, p. 547 for this observation):

(4) “Wenn die uns nachläuft, ist megakacke,” sagte Tschick. […].

“Das mit dem Stinken hättest du nicht sagen müssen.”

“Irgendwas musste ich ja sagen. Und Alter, hat die voll gestunken! Die wohnt garantiert auf der Müllkippe da. Assi.”

“Aber schön gesungen hat sie,” sagte ich nach einer Weile. “Und logisch wohnt die nicht auf der Müllkippe.”

“Warum fragt die dann nach Essen?”

“If die follows us, that‘s supercrap,” said Tschick. […].

“You did not have to say the part about (her) stinking.”

“I had to say something. And dude, die really stunk! I’m sure die lives at that garbage dump. Lowlife.”

“But sie sang beautifully,” I said after a while. “And obviously die does not live at the dump.”

“Why did die then ask for food?”

The feminine demonstrative die (‘she’) is used to establish a topical chain across the dialogue contributions, referring to the girl the two boys are talking about. In their corpus of 1,559 referential terms, Repp and Schumacher (2023) found 827 personal pronouns and 43 instances of demonstrative der, of which many occur in a topical der-chain, but no demonstrative dieser pronoun. We think that the earlier example from Weinrich (1), already shows that der is in fact compatible with referents that are discourse topics. The first sentence by A in (1) is a case of a question that introduces a referent as a discourse topic to ask about it. In B’s response, then, den picks up a referent that is already a discourse topic, and together with its position before the verb makes sure that this referent will likely be interpreted also as the topic of the current sentence. We thus offer a reanalysis here of the form that der does not “promote” its referent to topic status (i.e., is not a topic shifter); it just signals that its referent is a likely candidate for a sentence topic, and it does not avoid referents that are discourse topics (see our hypotheses below for a more detailed formulation). A reviewer points out that in B’s response, the first-person pronoun ich might also be the topic since it occurs in the other topic position that Frey (2004) identifies. We agree that the continuation does not allow to definitely resolve this. However, a continuation like Ja, der ist ja sehr beliebt ‘yes, it is quite popular after all’, in which der is unambiguously the sentence topic, seems absolutely fine to us. On the other hand, with dieser instead of der, the sentence becomes infelicitous in this context. Summing up, these observations and corpus studies show that demonstrative pronouns are felicitous in one-antecedent contexts, and they are affected by topical structure. In view of the evidence presented by Hinterwimmer (2020) and Repp and Schumacher (2023), as well as examples like (3) and arguably (1), we observe against Abraham’s (2002) (2b) and (2c), that der, but not dieser, can establish topic chains with repeated use of der. We think it is possible that register/formality plays some role in explaining the discrepancy between (2b)/(2c), on the one hand, and (3)/(4), on the other, since the latter examples clearly showcase a more colloquial style. In our experiments, we aim to neutralize the effect of register (see below). Another potential reason is that as laid out above, several studies have found evidence that both der and dieser avoid structurally prominent antecedents, such as subjects and agents, in contexts with multiple antecedents (e.g., Bosch et al., 2007; Schumacher et al., 2016; Bader et al., 2022). In (2b) and (2c), der is intended to pick up such structurally prominent referents, while in (1) this is not the case. In our experiments, we aim to also disentangle the effect of topichood from that of subjecthood and agentivity. Additional evidence for the use of the demonstrative der linked to a topical referent in a less informal register is provided by (5).

(5) Die Vorstellung der deutschen Nationalmannschaft gegen Japan war desaströs. Beim 1:4 zerfiel das Team zum Schluss in seine Einzelteile. Und Bundestrainer Hansi Flick? Der möchte weitermachen.2

The German national team’s performance against Japan was desastrous. During the 1:4 game the team fell apart toward the end. And national coach Hansi Flick? Der wants to continue.

In (5), the question Und Bundestrainer Hansi Flick? ‘And national coach Hansi Flick?’ serves to turn the referent, Bundestrainer Hansi Flick, into the aboutness or sentence topic of the next sentence, in the sense of Reinhart (1981) (cf. Frey, 2004. See also the results of a judgment task on topic questions, Buchholz and von Heusinger accepted). In this next sentence, it is then referred to via the demonstrative pronoun der in initial subject position. Examples like (5) with der are relatively frequent in German newspaper prose, but nearly non-existent with dieser. In order to test this intuition, we ran a small corpus search in the tagged newspaper archive of the German national reference corpus DeReKo (Institut für Deutsche Sprache, 2019), looking for sentences like Und der Bundestrainer? i.e., instances of Und followed by an article, a noun, and the question mark.3 Of the 2,462 total hits, we analyzed the first 110 that really were instances of our target sentence type, 55 from the Swiss newspaper St. Galler Tagblatt and 55 from the German newspaper Braunschweiger Nachrichten. We looked at the sentence directly following the target sentence and analyzed whether it contained a referential expression whose antecedent is the referent asked about in the target sentence, and the form of this referential expression. The topical referent from the target sentence was anaphorically taken up again in the subsequent sentence in 61% of all cases. In 45% of all cases (50 out of 110), this was done via a pronoun, including zero pronouns. Of those, 19 instances were with a personal pronoun, 15 with zero, 14 with a der-demonstrative pronoun, but only 2 with a dieser-demonstrative pronoun. This seems to confirm our intuitions that der is quite compatible with a topical referent, while dieser clearly seeks to avoid it. Note that the frequent occurrence of zero pronouns here confirms that the referent is indeed topical, since German allows topic drop in restricted contexts but not the omission of pronouns in general (cf. Trutkowski, 2016; Schäfer, 2021).

We have now gathered some evidence that the German demonstratives differ in how sensitive they are to the topichood of their antecedent. The forward-looking potential of the demonstratives with regard to topic structure has been less fully explored. One of the few relevant studies is Fuchs and Schumacher (2020), who compared er, der, and dieser in a story continuation study. Their results regarding whether the choice of pronoun has an effect on the number of referential re-mentions (i.e., referential persistence) further downstream only show a numerical difference and should be seen as inconclusive also because of an imbalance in the dataset due to the nature of the task. Referential persistence is not quite the same as discourse topichood, but it is undoubtedly the case that if a given pronoun had the function of a discourse topic shifter in the sense that its referent remains a discourse topic for a longer stretch of discourse after its use, we should expect to see an increase of re-mentions of its referent. In our experiments, we only look at the backward-looking sensitivity of the demonstratives. Therefore, when we say that a demonstrative is a discourse topic shifter, we can only say this in the sense that its use allows for the potential of remaining a discourse topic further downstream, but we cannot strictly speaking say anything about its further forward-looking behavior. We consider the forward-looking behavior of the demonstratives with regard to this aspect an extremely worthwhile topic of future research, however.

We are now ready to formulate the hypotheses that our experiments are designed to test.

1.5 Hypotheses

With our experiments, we aim to contribute to the discussion about the topichood sensitivity of German demonstrative pronouns, specifically in two points. We want to differentiate between more global and more local topichood effects by comparing the sensitivity to discourse topics vs. sentence topics and comparing this to the discourse function of personal pronouns. We formulate the following three hypotheses that we aim to test: First, for personal pronouns, we hypothesize that personal pronouns are the default anaphoric expressions in unambiguous contexts, where they are not sensitive to discourse or sentence topichood (H1). Second, for dieser, we hypothesize that dieser is a discourse topic shifter. It has a strong preference for contexts where its antecedent is not a discourse topic but where dieser itself refers to a discourse topic in the current sentence (H2). Finally, for der, we hypothesize that its discourse management function is to mark its referent as a sentence topic for the current sentence. It often refers to a local non-topical antecedent, but it is not sensitive to the more global discourse topic (H3).

We assume that the discourse topic shifting function of dieser (H2) is responsible for the fact that it does not occur two times in referential chains. For der, we assume that its function of marking the sentence topic, together with its well-attested avoidance of structurally prominent (subject, proto-agent, first-mentioned) antecedents, leads to it often being involved in local (sentence) topic shifts. At the same time, its insensitivity to more global (discourse) topichood contributes to its aptness for forming topical chains on its own.

From our hypotheses (H1–H3), we derive the following predictions: er should not show any sensitivity to the topichood of its antecedents, i.e., should not prefer or disprefer topical antecedents, whether they are sentence topics or discourse topics. Dieser, on the other hand, should clearly disprefer antecedents that are discourse topics. Since sentence topics always have a potential for being discourse topics, dieser should also disprefer them. Der, on the other hand, should be insensitive to the discourse topichood status of its antecedents. It should, however, also disprefer sentence topics as antecedents as long as their sentence topichood cooccurs with them having structurally prominent roles (first-mentioned entities, subjects, proto-agents). We thus have two variables of interest, with three levels each: type of pronoun (er/der/dieser) and the topichood status of its antecedent (discourse topic/sentence topic/non-topical), with interactions expected. Instead of testing all of them at once in a single experiment, we split our experimental design up into two main experiments (1 and 2) consisting of two sub-experiments (1a and 1b, 2a and 2b) each. The two sub-experiments in both cases were nearly identical and run in parallel, with Experiment 1a and Experiment 2a testing er vs. der and Experiment 1b and Experiment 2b testing er vs. dieser. We decided to test each type of demonstrative pronoun individually against the personal pronoun rather than testing all three together because we were worried that being made aware of the presence of the other demonstrative in the same experiment would affect participants’ judgments. In particular, judgments might be influenced by the fact that the two types of demonstratives have different register preferences (cf. Ahrenholz, 2007; Patil et al., 2020). In each sub-experiment, we manipulated contexts so that the unambiguous antecedent would either be a continued topic from the beginning of the discourse (continuing context) or just newly introduced in the precritical sentence (shifting context). We designed the experiments so that their results in combination would allow us to test the hypotheses we derived from the literature (as described above): Experiment 1 tested for topic structure overall (combining sentence and discourse topichood), Experiment 2 only tested for discourse topichood, with an antecedent in the precritical sentence that is not a sentence topic in the shifting condition (see below for conditions). Thus, our hypothesis H2 about dieser predicts that both in Experiments 1b and 2b, dieser should prefer the shifting condition and is falsified if it does not in one of them. For der, on the other hand, our hypothesis H3 predicts that der should prefer the shifting condition only in Experiment 1a, but not in Experiment 2a.

2 Experiments 1a and 1b

Experiments 1a and 1b were intended to test our predictions about the sensitivity of the German demonstrative pronouns to both the discourse and sentence topic status of their referents. As described above, we operationalized discourse topichood in two ways: for our continuing condition (see below for conditions), this was done via consistent realization of a referent as sentence topic. For our shifting condition, we operationalized it by initially introducing an event, such as a football game, on which subsequent sentences added further information. Sentence topichood was operationalized via realizing a referent as initial subject. We assume that introducing a referent at the beginning of a discourse in subject position via a full (specific indefinite) noun phrase and then using it as subject of the subsequent sentences makes it a discourse topic even across sentences that do not explicitly realize it but also do not introduce competing referents (Givón, 1983). Conversely, when a new referent is later introduced in the discourse and then picked up by a pronoun in a topic position, we take this as an instance of a local or sentence topic shift (Grosz et al., 1995). Our assumption is that the German demonstrative pronouns are (differently) sensitive to this difference in topic continuity, unlike the German personal pronouns, which can take any grammatically possible antecedent. Specifically, we assume that the demonstrative pronouns from both the der and the dieser series prefer shifted topics over established, continuing, topics (cf. Bosch and Umbach, 2007), but that this preference is sensitive to only local or sentence topics for der, but to both local and global (discourse) topics for dieser.

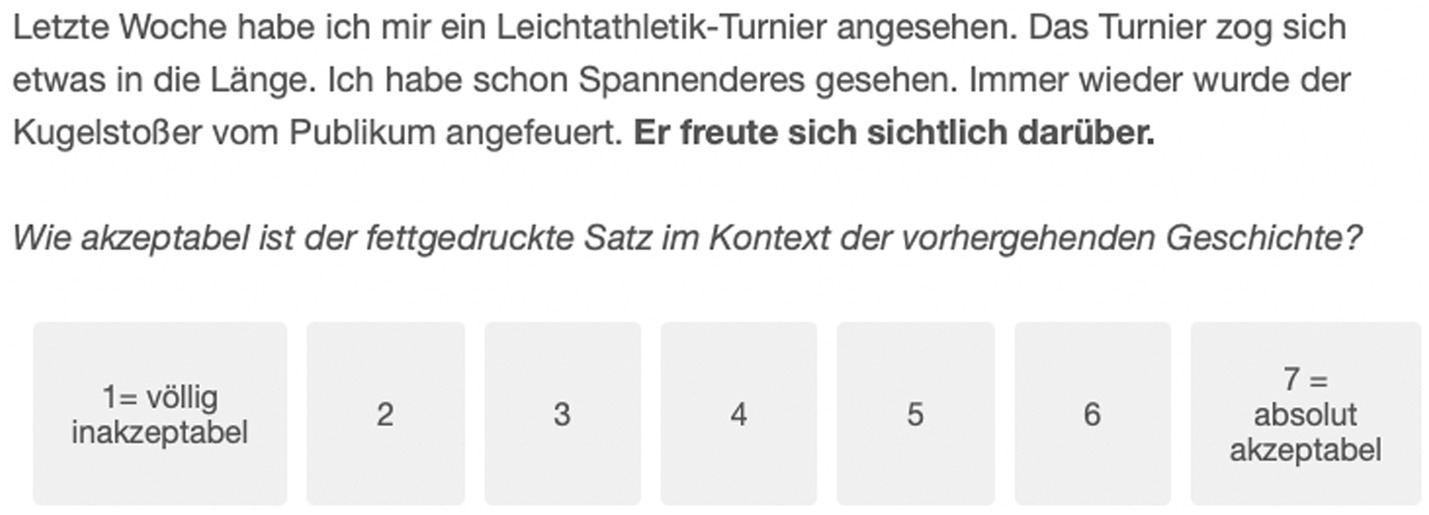

2.1 Materials

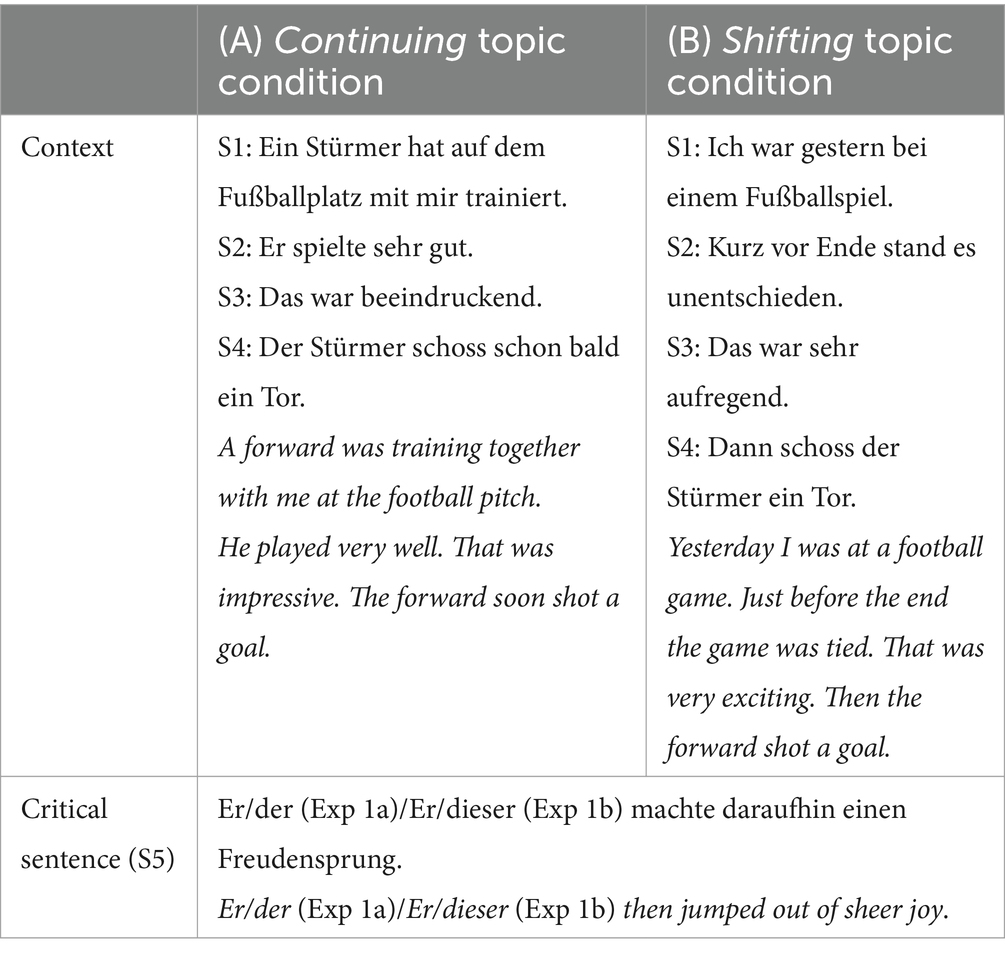

In both sub-experiments (1a and 1b), critical items were short narrations. They consisted of four sentences establishing a context, followed by a fifth critical sentence. Table 1 gives an example of an experimental item in all four conditions.4 In order to avoid confounds created by the effects of perspective-taking (cf. Hinterwimmer and Bosch, 2016, 2018; Hinterwimmer, 2020; Patil et al., 2023), the narrations were all told from the perspective of a first-person narrator who was established as a participant in or immediate observer of the sequence of events and as a source of evaluative judgment, thus being the most prominent perspective-taker.

In the continuing topic context condition (A in Table 1), the context introduced a topical discourse referent in the first sentence by realizing it as a full indefinite noun phrase. This referent was the human target referent and the only discourse topic in the story. It was realized in initial subject position in the first sentence. The second sentence realized the same referent again as subject, this time pronominalized, to fully establish it as the current discourse topic. The third sentence gave a subjective evaluation of the overall situation from the perspective of the first-person narrator without explicitly mentioning the topic again. The third sentence also provided a certain distance that allowed us to use a full definite noun phrase for the target referent in the fourth sentence, rather than a personal pronoun, which would not be a good antecedent for a dieser demonstrative. The fourth sentence was the precritical sentence. In the continuing condition, it again realized the target referent as a full-definite noun phrase in initial subject position.

In the shifting context condition (B in Table 1), the referent introduced in the first sentence was inanimate, referring to an event or a situation as a more abstract discourse topic. The second and third sentences provided further information on this referent, thus establishing it as the discourse topic. In the shifting condition, the fourth and precritical sentence was then the first to introduce the human target referent. This referent was accessible from the bridging context established by the topical event or situation (e.g., football game—forward), so that it was possible to realize it as a definite noun phrase. The precritical sentence in the shifting context realized the target referent as a full definite noun phrase, either as a (non-initial) subject, an (in)direct object, or a prepositional agent in a passive construction.

The fifth and critical sentence was the same in the two context conditions. The pronoun in initial subject (topic) position unambiguously referred to the human target referent (der Stürmer ‘the forward’). The type of pronoun varied across experiments and conditions: in Experiment 1a, it was er (masculine personal pronoun) vs. der (masculine demonstrative pronoun). In Experiment 1b, instead of er vs. der, it was er vs. dieser (a masculine pronoun from the other demonstrative series). We used the masculine forms as they are fully specified for case and number, while feminine or neuter pronouns (die, das) are underspecified for case and number.

2.1.1 Conditions

Both sub-experiments (1a and 1b) had a 2 × 2 design with two conditions: context and pronoun. Context had two levels: continuing topic context and shifting topic context, as described above. Pronoun also had two levels, referring to which type of pronoun was used in the final (critical) sentence: either the personal pronoun er, or a demonstrative pronoun: der in Experiment 1a, or dieser in Experiment 1b.

2.1.2 Fillers

The experiment used three types of filler items. They all consisted of short narrations of similar length as the critical items but contained more referents and no pronominalizations. One group of fillers was intended to receive a good but not perfect rating. They introduced two competing referents, and in the final critical sentence, one of those was realized with a full definite noun phrase after the prefinal sentence had been about the other referent (cf. (6)). Another group of fillers was intended to receive a slight rating penalty because of a name repetition: both the prefinal and the final sentence realized the same referent as a full definite noun phrase (cf. (7)). The final group of fillers was intended to receive a decidedly bad rating due to contextual inadequacy without being outright ungrammatical. In them, the final sentence had the same subject and topic referent as the prefinal sentence but did not realize it overtly, which is possible under some circumstances in German (topic drop, cf. Trutkowski, 2016; Schäfer, 2021). However, the final sentence was introduced with a contrastive connector (aber ‘but’ in (8)). That was at odds with the content of the sentence, which did not stand in a contrastive relation to the preceding context and thus made the topic omission highly unusual.5

(6) [fillers: ok] Vor der Schließung der Gerichte aufgrund der Pandemie sollte die letzte öffentliche Gerichtsverhandlung stattfinden. Der Richter saß bereits im Gerichtssaal. Der Anwalt betrat den Raum. Der Deckenventilator drehte sich langsam. Der Richter fokussierte gewissenhaft seine Gedanken.

Before courts of law were to be closed due to the pandemic, the final public hearing was to take place. The judge was already sitting in the courtroom. The lawyer entered the room. The ceiling fan was turning slowly. The judge conscientiously focused his thoughts.

(7) [fillers: name penalty] Es war wieder erlaubt, Live-Musik zu spielen. Der Dirigent des Symphonieorchesters betrat den Saal. Der Solist erhob sich. Der Dirigent schaute das Orchester an. Der Dirigent begann das Konzert.

It was permitted to play live music again. The symphony orchestra’s conductor entered the concert hall. The soloist rose. The conductor looked at the orchestra. The conductor began the concert.

(8) [fillers: bad] Es gab eine Pressekonferenz zu dem Mordfall. Der Kommissar erschien in dem Raum. Der Fotograf begann Fotos zu schießen. Der Kommissar schaute in seine Unterlagen. Aber begann von den Ereignissen zu berichten.

A press conference was held about the murder case. The inspector appeared in the room. The photographer began to take pictures. The inspector looked into his files. But began to report on the events.

2.2 Method

We created 24 critical items in 2 × 2 = 4 different versions corresponding to the experimental conditions, with only the choice of the demonstrative pronoun (Experiment 1a: der, Experiment 1b: dieser) different between the two experiments. For each experiment, the critical items were distributed across four lists via Latin-square design, such that each item only appeared once per list and all conditions were distributed equally across the lists. Twenty-four filler items (12 ok, 6 with name penalty, and 6 bad) were also added to each list. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four resulting lists, and the items were presented in a randomized order. Participants were shown each item individually. The final sentence was set in bold. At the beginning of the experiment, participants were told to read through each item carefully and then to judge the acceptability of the final sentence in its preceding context. They were told that this meant judging how well the final sentence fitted as a continuation of the preceding story. At the end of each item, participants were asked, Wie akzeptabel ist der fettgedruckte Satz im Kontext der vorhergehenden Geschichte? (‘How acceptable is the sentence in bold in the context of the preceding story?’). They then had to judge the critical sentence on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 being völlig inakzeptabel (‘totally inacceptable’) and 7 being absolut akzeptabel (‘fully acceptable’). Only after rating the current item could they proceed to the next. The experiment was conducted in German and implemented via Qualtrics. Figure 1 provides an image of an example item as it was presented to the participants.

2.2.1 Participants

We recruited 89 and 94 students from the University of Cologne for Experiment 1a and Experiment 1b, respectively. They participated for course credit. We made sure that no participant who participated in Experiment 1a also participated in Experiment 1b, and vice versa. Participants who did not speak German natively or did not complete the experiment were excluded. This left 80 (67 female, 12 male, 1 non-binary, mean age = 20.5, SD = 4.01, range 18–52 years) and 86 (73 female, 16 male, mean age = 20.71, SD = 2.54, range = 18–34 years) participants for Experiment 1a and Experiment 1b, respectively, for the final analysis.

2.2.2 Predictions and hypotheses

As lined out above, we hypothesize that the demonstrative pronouns from the dieser series are clearly sensitive to the topichood of a referent, such that they disprefer antecedents that are established discourse topics (H2), while the personal pronoun er readily takes any antecedent regardless of its topichood status (H1). For the der-demonstrative pronouns, our hypothesis H3 predicts that they should be insensitive to the discourse topichood status of their antecedents. They should, however, also disprefer sentence topics as antecedents as long as their sentence topichood cooccurs with them having structurally prominent roles (first-mentioned entities, subjects, proto-agents), which is the case in our continuing condition. In terms of predictions, we predict that er should be rated highest and show no difference between the two context conditions (derived from H1). Both der and dieser are expected to be rated lower overall because they are more marked (effect of pronoun predicted). Dieser in Experiment 1b is also expected to show a difference between the conditions (derived from H2), such that it is rated higher in the shifting context condition than in the continuing condition. We therefore expect an interaction between pronoun and context. For der in Experiment 1a, in line with hypothesis H3, we also predict a difference between the levels of context and thus an interaction effect, likely smaller than the one for dieser, since the discourse topichood of the antecedent in the continuing context should play no role for der.

2.2.3 Data analysis

Data were analyzed in R (R Core Team, 2023) using tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019) and ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016) for visualization. We used Bayesian statistics because this allows to fit complex models with relative ease and because they provide us with a quantification of the uncertainty about our effects of interest via credible intervals (CrIs). In Bayesian statistics, the 95% CrI indicates the interval within which values for the estimated parameter drawn from the posterior distribution lie with 95% certainty, given the model and the data. When the CrI does not include zero, we take that as evidence that the effect in question is reliable, again given the model and the data. In addition, we conducted one-sided hypothesis tests based on the posterior distribution. The hypothesis tests indicate the probability that the effect is either negative or positive, depending on the sign of the estimated parameter, based on the proportion of the posterior distribution that is negative or positive. Data and R scripts for all four experiments are openly available via OSF.6

2.3 Results

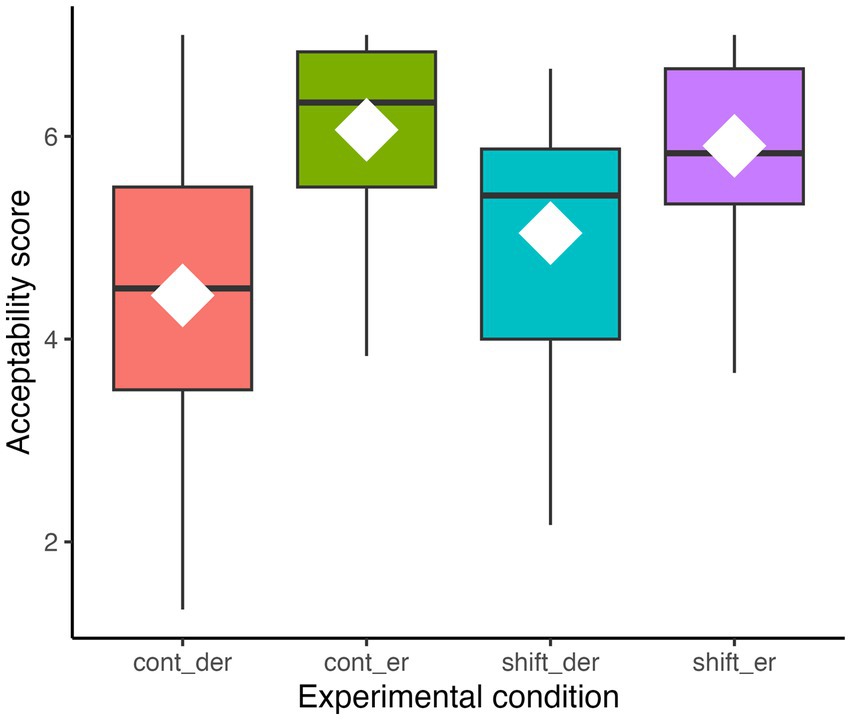

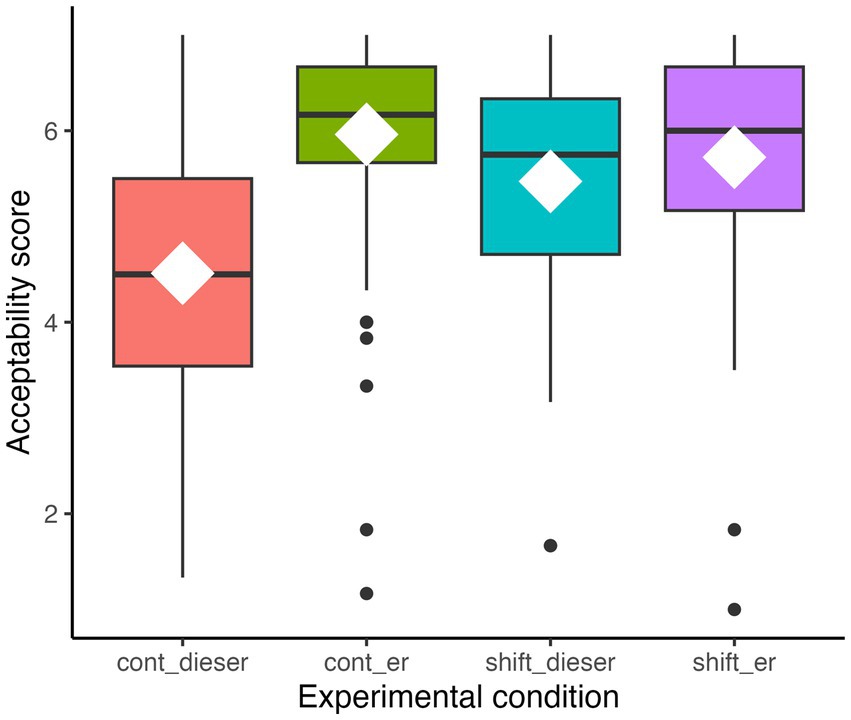

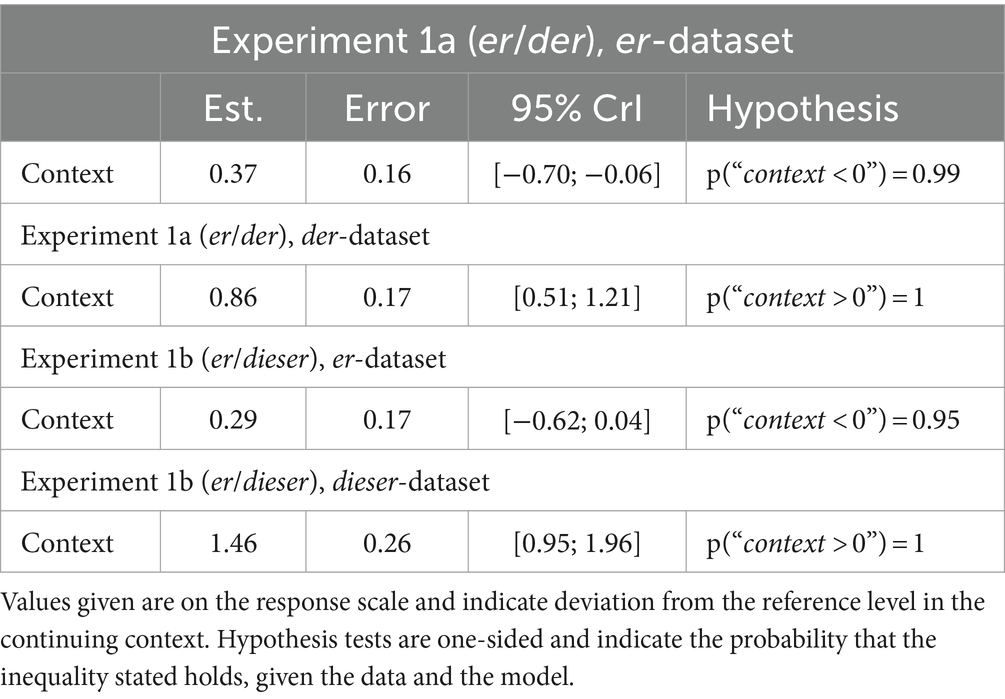

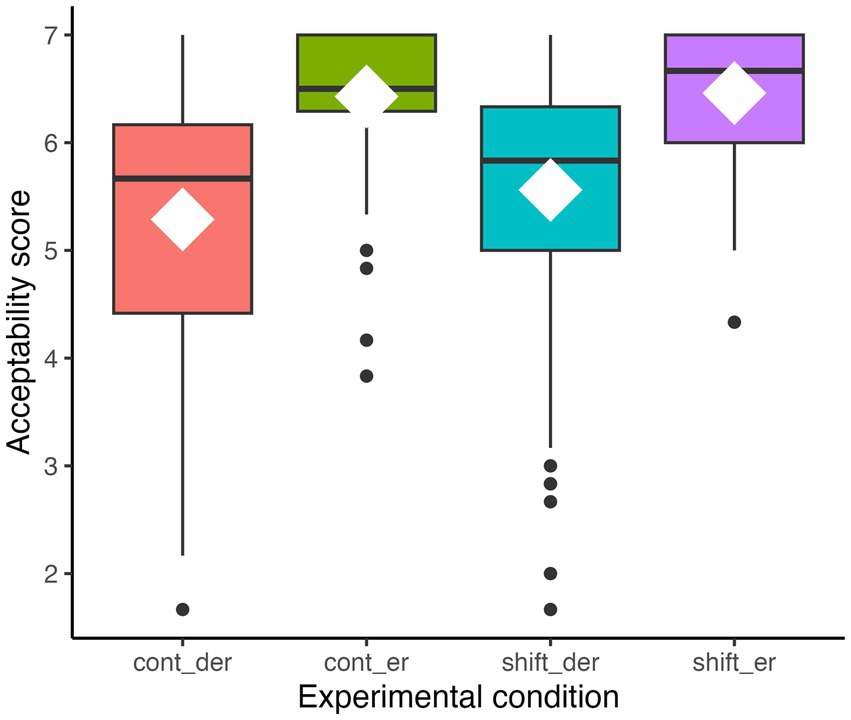

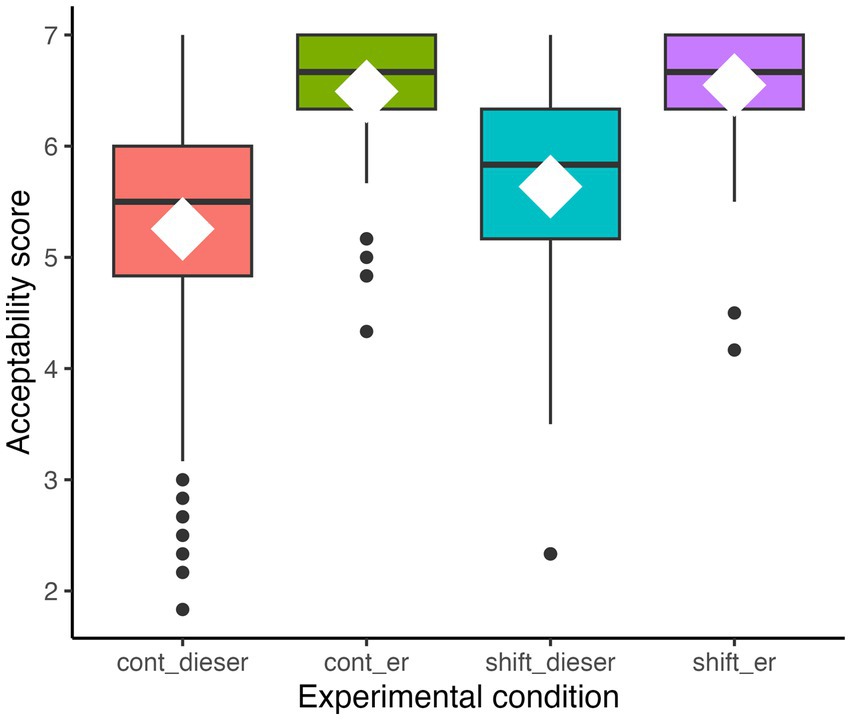

Boxplots with raw median and mean values for the four crossed conditions of Experiment 1a (er/der) and 1b (er/dieser) are given in Figures 2, 3, respectively. The values indicate that for er, the average ratings are very high and do not differ much due to the context condition. The ratings for the demonstratives, on the other hand, do seem to differ due to context, with the shifting context rated higher than the continuing context. To confirm that these are real differences, we conducted inferential statistics.

Figure 2. Boxplots with raw median (black lines) and mean (diamonds) per crossed condition for Experiment 1a (er/der).

Figure 3. Boxplots with raw median (black lines) and mean (diamonds) per crossed condition for Experiment 1b (er/dieser).

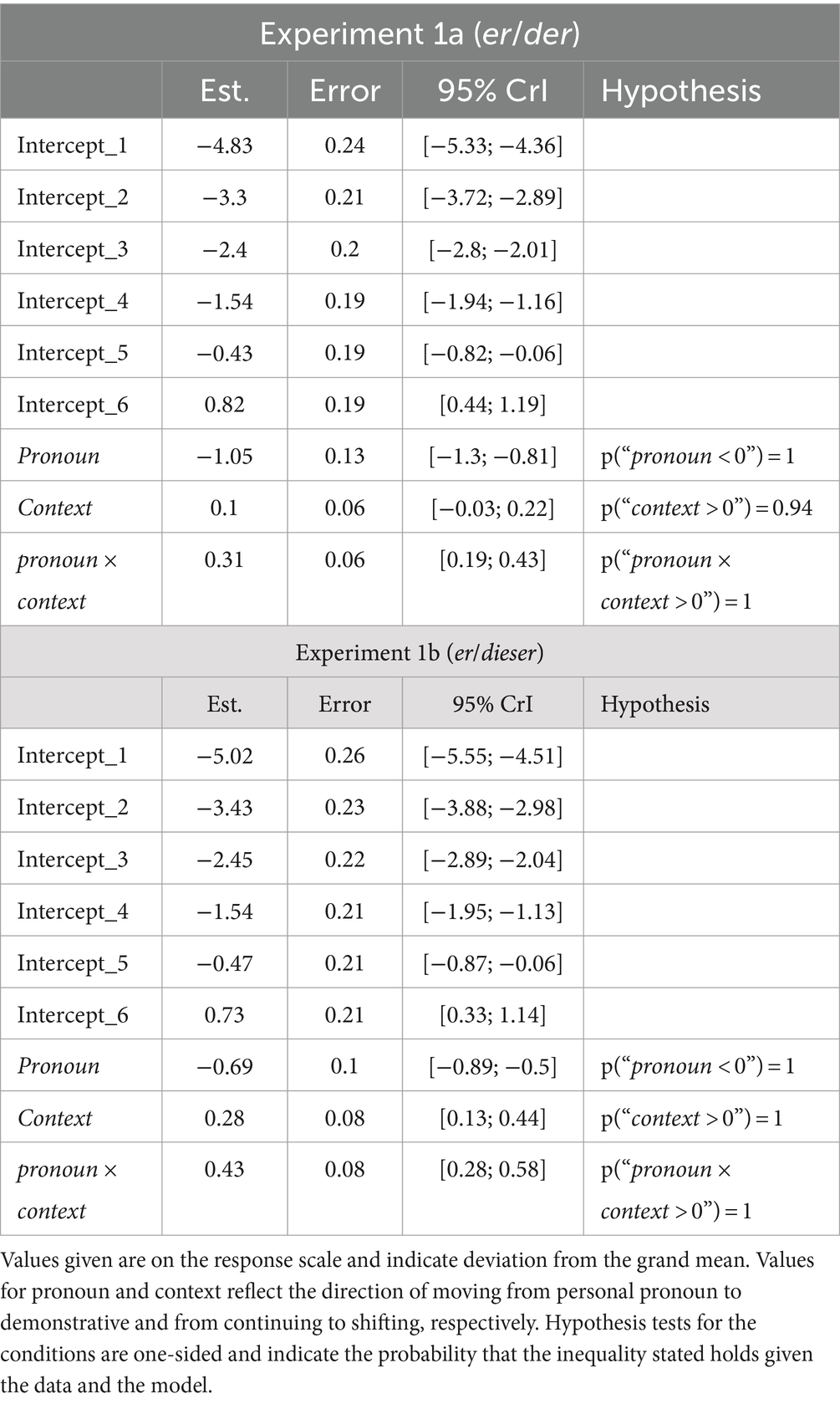

We fitted one Bayesian generalized mixed-effects model with cumulative link function (because of the ordinal nature of the data) to the data from Experiments 1a and 1b each, using brms (Bürkner, 2017, 2018, 2021) and cmdstanr (Gabry and Češnovar, 2022). The models used weakly informative priors.7 They included context (continuing [coded as −1] vs. shifting [coded as 1]) and pronoun (er [coded as −1] vs. der—Exp. 1a/dieser—Exp. 1b [coded as 1]) as fixed-effects and random intercepts, slopes, and their correlations for participant and item. The models were sum-coded. The fixed-effects model results for both experiments, together with the results of relevant one-sided hypothesis tests, are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Model results for the Bayesian mixed-effects models with cumulative link function for Experiments 1a (er/der) and 1b (er/dieser).

According to the model results, there is a reliable effect due to pronoun for both experiments. It is negative in both cases, indicating that the demonstratives were consistently rated lower than the personal pronoun. For both experiments, the entire posterior distribution due to the pronoun effect lies to the left of zero, so that given the model and the data, it can be taken as certain (p = 1) that the effect exists and is negative.

In Experiment 1b (er/dieser), there is also a reliable effect due to context on its own. It is positive, indicating that the shifting condition is rated somewhat higher than the continuing condition. Its posterior distribution is positioned so far to the right from zero that it can be taken as certain (p = 1), given the model and the data, that the effect is positive. For Experiment 1a (er/der), the estimated parameter is also positive, but its CrI straddles zero and only 94% of its posterior distribution is positive, making it less than certain that the effect exists, given this model and the data. Most interestingly, there is also a reliable interaction effect between the two conditions in both experiments. In both cases, the posterior distributions are fully to the right of zero, so given the model and the data, it is certain that the effect is positive.

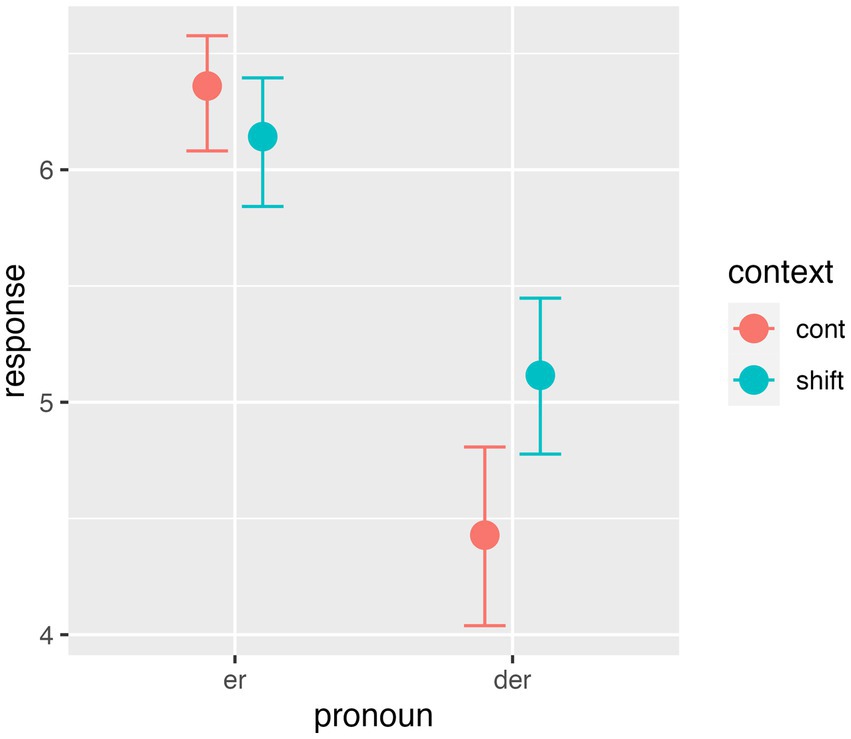

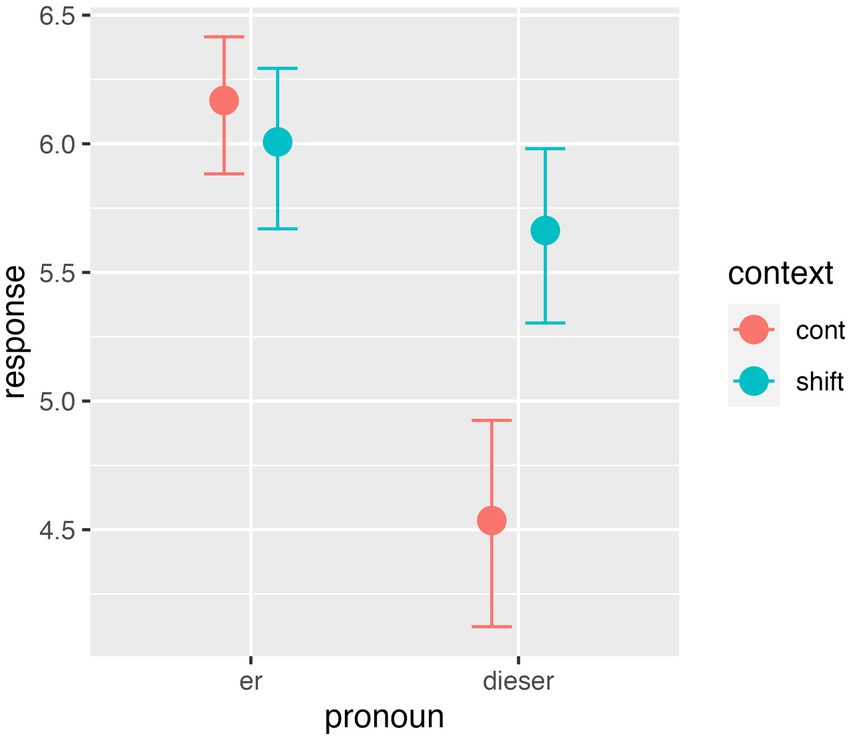

We use conditional effects to translate the model results to the response scale and thus quantify the effects. This treats the 7-point Likert response scale as continuous rather than ordinal, but eases interpretation. For visualization, Figures 4, 5 give estimated averaged responses per condition combination for the two experiments. The plots indicate how the interaction effect plays out: for er, the difference due to context is very small (at approximately 0.2 points for both experiments) and negative, with the shifting condition minimally lower than the continuing condition. However, for the demonstratives, it is much larger and going in the other direction, so that the shifting condition is rated higher than the continuing condition: for der in Experiment 1a, it is at approximately 0.69 points (continuing: 4.43, CrI = [4.04; 4.81]; shifting: 5.12, CrI = [4.78, 5.45]), and for dieser in Experiment 1b, it is even larger, at approximately 1.13 points (continuing: 4.53, CrI = [4.12, 4.93]; shifting: 5.66, CrI = [5.29, 5.98]).

Figure 4. Model-estimated average responses per condition combination for Experiment 1a (er/der), treating the 7-point Likert response scale like a continuous scale. Error bars indicate 95% credible intervals.

Figure 5. Model-estimated average responses per condition combination for Experiment 1b (er/dieser), treating the 7-point Likert response scale like a continuous scale. Error bars indicate 95% credible intervals.

2.4 Discussion

The results partially confirm our predictions: in both experiments, sentences with the personal pronoun er were rated very high, and with only small differences regarding whether their referent is an established discourse and sentence topic or not. Sentences with the demonstratives from both the der and the dieser series were reliably rated lower overall. However, they were rated reliably higher in the shifting condition, i.e., when their referent was a topic that had just been shifted to, than in the continuing condition, when it was a continuing, established discourse topic and sentence topic. In addition, this rating difference due to context for the demonstratives was numerically higher for dieser than for der. It seems likely that the fact that this effect is so large for dieser is what is responsible for the overall effect due to context in Experiment 1b. We can see this when we look only at er: in both experiments, the context effect for er is very small and even numerically going in the other direction than the overall effect, with shifting contexts rated marginally lower than continuing ones.

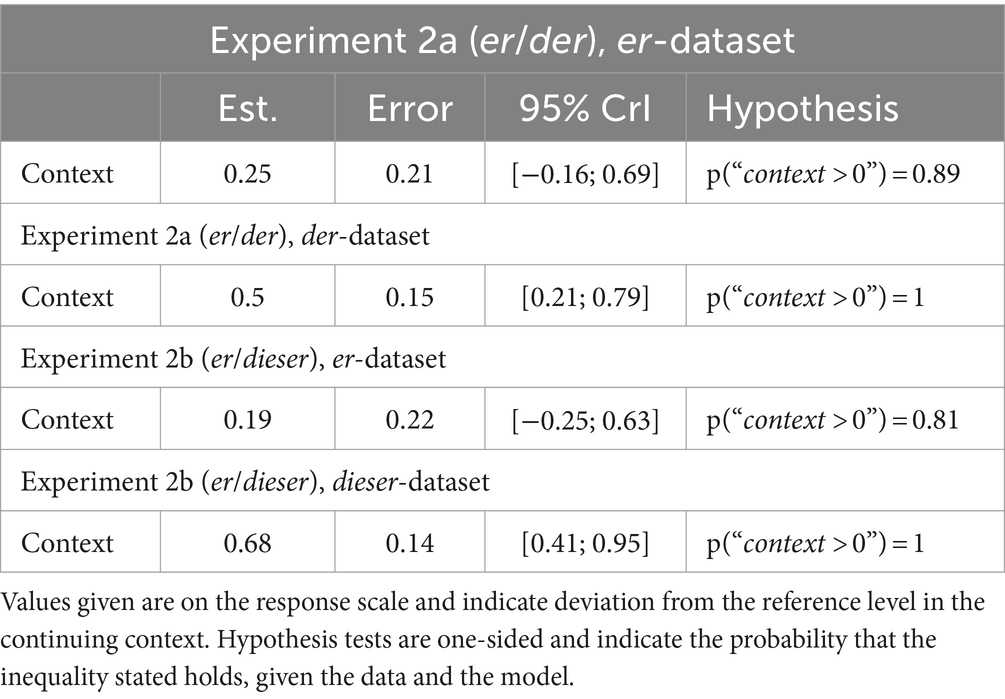

In order to investigate the context effects for each of the pronouns separately, we split up the datasets for both experiments along the pronoun condition to run Bayesian mixed-effects models with only context as a fixed effect (as well as random intercepts, slopes, and correlations) on them. The models were treatment-coded, with continuing as the intercept. The results are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Estimated context parameters and one-sided hypothesis tests based on results from Bayesian models run on the datasets from Experiments 1a (er/der) and 1b (er/dieser) split along the pronoun condition.

The results in Table 3 are somewhat surprising in one regard, namely that the numerically small preference for the continuing over the shifting condition turns out to be quite reliable for the er datasets of both experiments, which goes against our hypothesis H1. This is actually in line with previous studies that have described a potential subject or first-position preference for personal pronouns (cf. Kaiser and Trueswell, 2008; Kaiser, 2011; Fuchs and Schumacher, 2020; Patterson and Schumacher, 2021). We reserve some doubt about these results since the same effect did not emerge in our second pair of experiments (2a and 2b; see below). If anything, it is clearly very small.

In any case, the results from splitting the datasets confirm the explanation given above as to why there is a reliable effect due to context in Experiment 1b (er/dieser): this seems entirely due to the strength of the effect in the dieser dataset because the er dataset actually shows a slight trend in the other direction.

We thus take the results so far as evidence for our hypotheses: the personal pronouns in German are not or only very slightly sensitive to topichood (H1), while the demonstrative pronouns from the dieser series clearly disprefer topical antecedents (H2). The demonstrative pronouns from the der series also show a dispreference for topical antecedents, in line with the predictions derived from our H3. However, as indicated above, the results cannot yet support our H3 on der on its own because we manipulated both discourse and sentence topichood. It is still an open question where our observed effect comes from: as they are, the items used in Experiments 1a and 1b create a difference between the continuing and the shifting condition not only in the preceding global context but also in the sentence immediately coming before the critical sentence and thus manipulate both discourse and sentence topichood. The difference in interaction effect sizes between Experiment 1a (der) and 1b (dieser) allows for the possibility that some or even all of the observed effect for der is actually due to the very local difference in the preceding sentence. We address this issue via the second pair of experiments, in which only discourse topichood is manipulated.

3 Experiments 2a and 2b

Experiments 2a and 2b are quite similar to Experiments 1a and 1b. They address the question of how sensitive German personal and demonstrative pronouns are to discourse topichood, with Experiment 2a comparing the personal pronoun er to the demonstrative pronoun der, and Experiment 2b doing the same with the demonstrative pronoun dieser. However, unlike in the previous experiments, here we only manipulate the preceding context but leave the precritical sentence the same across conditions. This means that we can more precisely attribute the source of any resulting effects to the global context, i.e., discourse topichood, rather than the more local one of the previous sentence (sentence topichood).

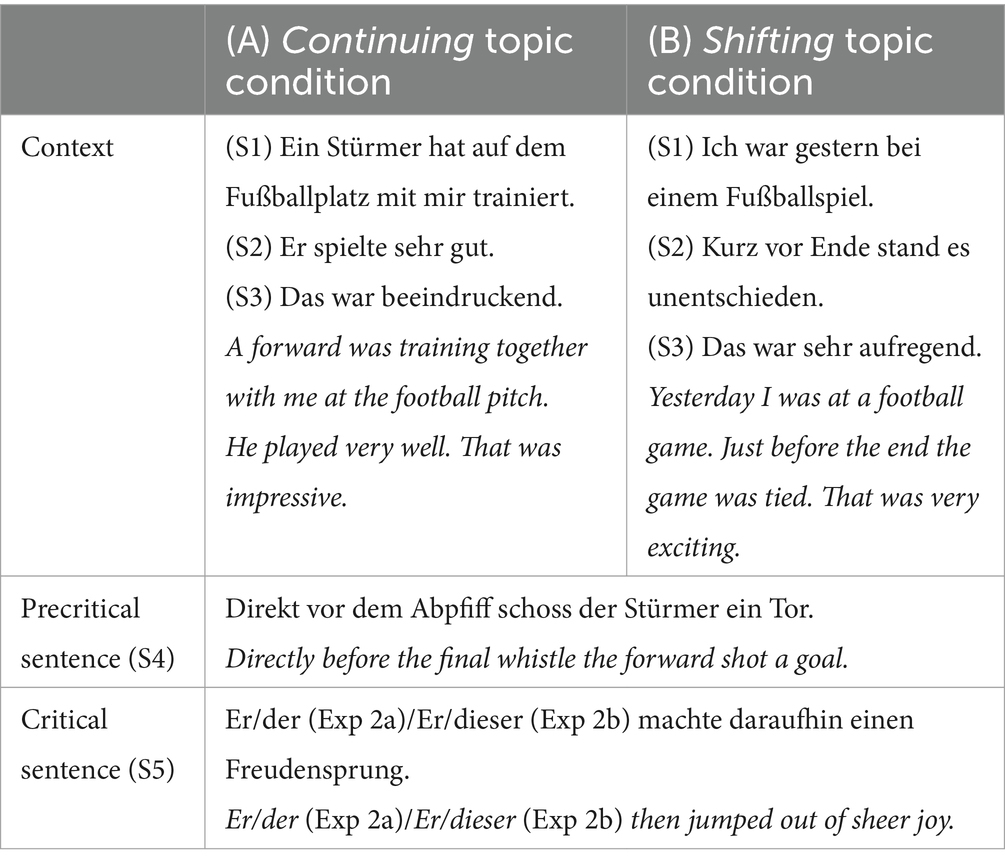

3.1 Materials

We used nearly the same critical items as in Experiments 1a and 1b, with the difference that we changed the sentence preceding the critical sentence so that it was the same in all conditions. The precritical sentence now always began with an (temporal or manner) adverb or adverbial phrase, followed by the verb, and then the target referent realized as a full definite noun phrase in sentence-medial subject position. We assume that such a construction does not strongly cue the target referent as sentence topic since it is not realized in initial position. The realization of the antecedent in non-initial position should also make the sentences with demonstratives more acceptable since they seem to favor non-initial antecedents (cf. Fuchs and Schumacher, 2020; Patterson and Schumacher, 2021). An example experimental item for all conditions is given in Table 4. The two levels of the context condition, continuing and shifting discourse topic, were thus now only different with regards to the discourse before the precritical sentence, but otherwise the same as in Experiments 1a and 1b (cf. A and B in Table 4). The critical sentences were also the same as in the previous experiments. Equally, we used the same fillers as before.

3.1.1 Conditions

The experimental conditions were the same as in Experiments 1a and 1b.

3.2 Method

The method was the same as in Experiments 1a and 1b.

3.2.1 Participants

We recruited 85 German native speaking participants via Prolific for each experiment, respectively. They were paid 2.55 GBP for their participation; in a study, we estimated that it would take 17 min to complete. On average, participants completed the study in 16 min. We made sure that no participant who had taken part in Experiment 2a also took part in Experiment 2b, and vice versa. Participants had to have at least a high school diploma, speak German natively, and have lived in Germany for the last 5 years. We excluded incomplete data from four participants so that data from 84 (26 female, 55 male, 2 non-binary, 1 other; mean age = 30.69, SD = 6.62, range = 21–45 years) and 82 (30 female, 49 male, 3 non-binary; mean age = 29.26, SD = 6.98, range = 20–47 years) participants was included in the final analysis for Experiment 2a and 2b, respectively.

3.2.2 Predictions and hypotheses

Predictions and hypotheses for the personal pronouns and for the dieser demonstratives are broadly the same as for the previous pair of experiments, except for der. Thus, we hypothesize that the demonstrative pronouns from the dieser series are sensitive to the discourse topichood of a referent (H2), such that they disprefer antecedents that are established discourse topics, while the personal pronouns like er readily take any antecedent regardless of its topichood status (H1). For the der demonstratives, our prediction, derived from our H3, is that they are not sensitive to the discourse topichood of antecedents and thus can pick up antecedents that are discourse topics. Only when this is the case, together with the results from Experiment 1a, can we say that we found support for our H3. Crucially, we can test these predictions with the current sub-experiments since the precritical sentences are the same across all conditions. Thus, any differences due to context would have to be attributed to the differences in the preceding, more global, discourse context. If we do not find effects due to context for der (i.e., an interaction), we can conclude, given the results from Experiment 1a, that der is sensitive to local (i.e., sentence) topichood, but not global (i.e., discourse) topichood. To recap the most important points: er should show no difference due to context and be rated higher overall, while der should be rated lower overall but also show no difference due to context. Dieser is expected to be rated higher in the shifting condition than in the continuing condition, leading to an interaction.

3.3 Results

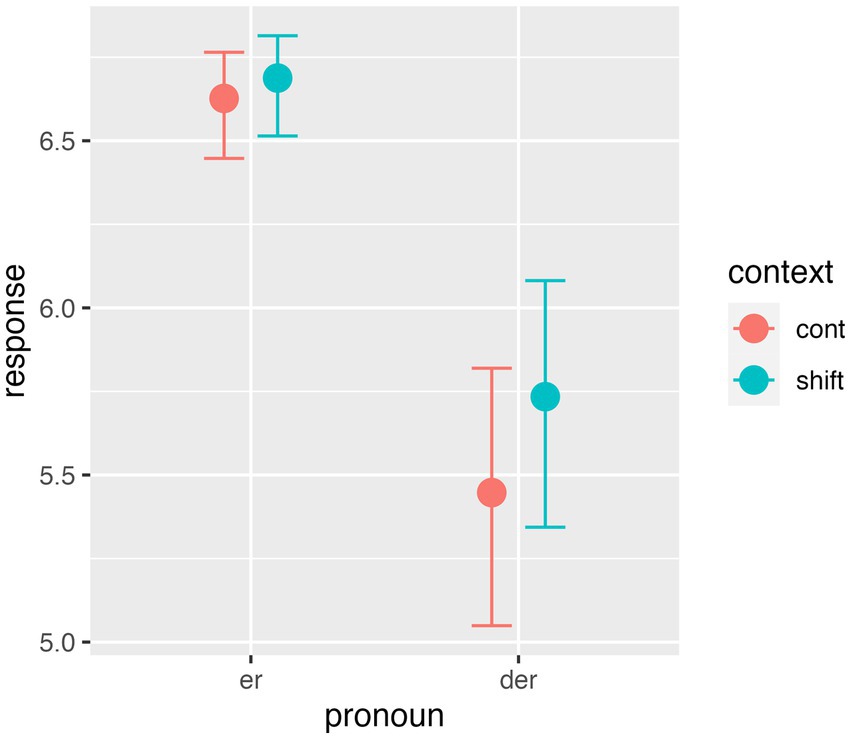

Boxplots with raw median and mean values for the four crossed conditions of Experiment 2a (er/der) and 2b (er/dieser) are given in Figures 6, 7, respectively. Values for er again are very high and do not seem to differ due to context. For the demonstratives, the ratings are slightly higher overall than before. This is expected since we now used precritical sentences that provide a somewhat better context for demonstrative pronouns (non-initial antecedents). The difference due to context now seems very small for der (Exp. 2a, Figure 6), but still somewhat larger for dieser (Exp. 2b, Figure 7), with the shifting context rated higher. To probe these observations, we again use inferential statistics.

Figure 6. Boxplots with raw median (black lines) and mean (diamonds) per crossed condition for Experiment 2a (er/der).

Figure 7. Boxplots with raw median (black lines) and mean (diamonds) per crossed condition for Experiment 2b (er/dieser).

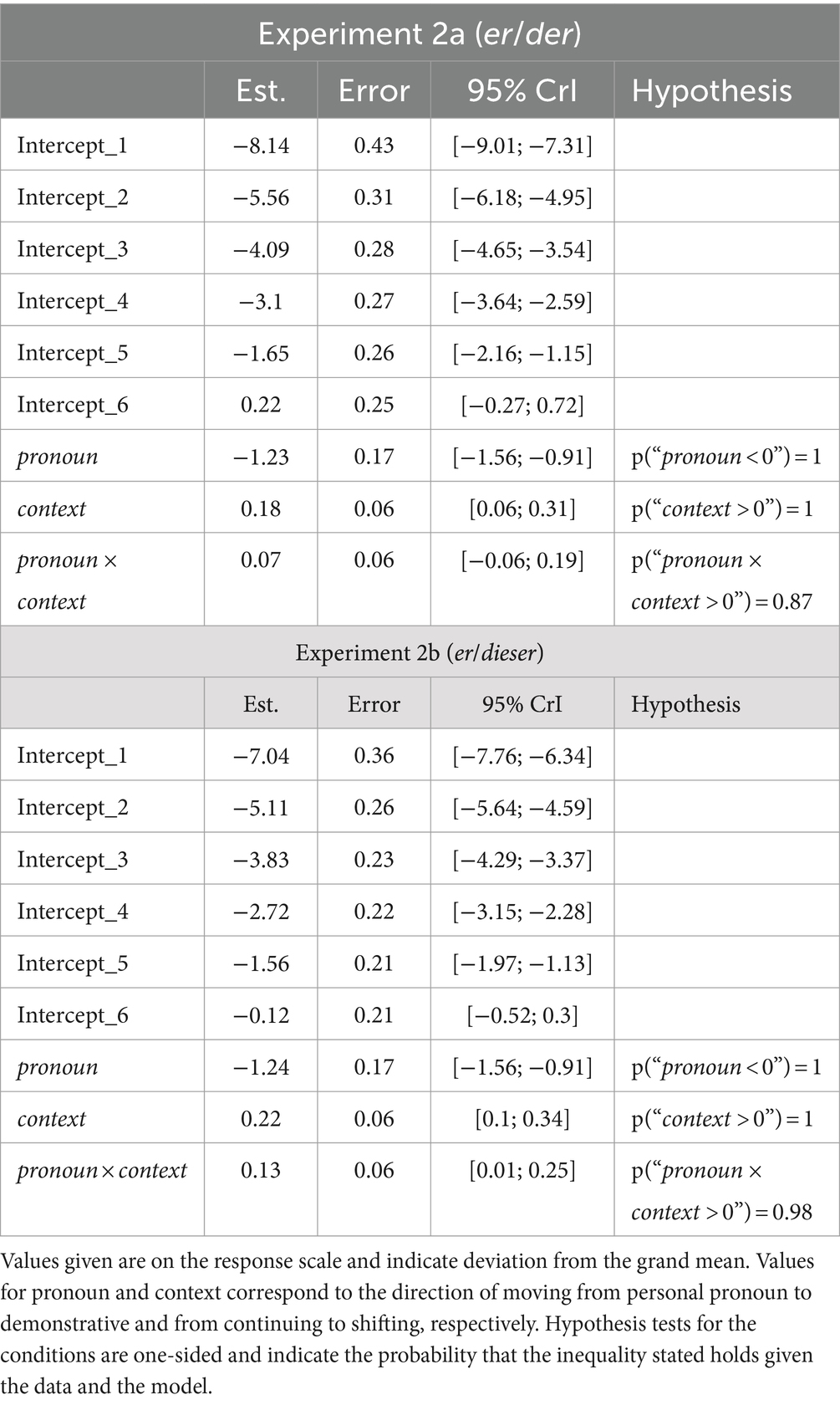

We again fixed one Bayesian generalized mixed-effects model with a cumulative link function to the data from Experiments 2a and 2b each, with the same weakly informative priors as before. The models included context (continuing vs. shifting) and pronoun [er vs. der (Exp. 2a)/dieser (Exp. 2b)] as fixed-effects and random intercepts, slopes, and their correlations for participant and item. The models were sum-coded in the same way as before. Model results for both experiments, together with the results of relevant one-sided hypothesis tests, are given in Table 5.

Table 5. Model results for the Bayesian mixed-effects models with cumulative link function for Experiments 2a (er/der) and 2b (er/dieser).

According to the results from both models, there is again a reliable negative effect due to pronoun for both experiments, so that the personal pronoun is rated higher than the demonstratives.

This time, the data from both experiments also show a reliable, albeit quite small, effect due to context overall. The posterior distributions are located quite close to zero, but for both experiments, it is still certain (p = 1), given the model and the data, that the effect is positive and non-zero.

Only for Experiment 2b (er/dieser) is the interaction effect (context × pronoun) reliable this time, in comparison to Experiments 1a and 1b. It lies at 0.13 (CrI = [0.01; 0.25]). The probability that it is positive and non-zero based on the posterior distribution for this model and data lies at 0.98.

For Experiment 2a (er/der), on the other hand, the effect is smaller, at 0.07 (CrI = [−0.06; 0.19]), and the posterior distribution includes zero. The probability that the effect is actually positive and non-zero only lies at 0.87, indicating that it is not a reliable effect.

Thus, we assume that the interaction effect is real for dieser, preferring shifting over continuing contexts, but not for der.

Figures 8, 9 visualize the interaction for both experiments, again using conditional effects to translate the model results to the response scale and quantify effects. For er, the difference due to context this time is minimal (at <0.1 for both experiments and positive). For the demonstratives, it is larger, with the shifting condition rated higher than the continuing condition. However, for der in Experiment 2a, it is at approximately only 0.29 points (continuing: 5.44, CrI = [5.05; 5.82]; shifting: 5.73, CrI = [5.34; 6.08]). For dieser, in Experiment 2b, it is still at approximately 0.46 points on average (continuing: 5.31, CrI = [4.93; 5.66]; shifting: 5.77, CrI = [5.41; 6.08]). Thus, the model results predict that on average for dieser, antecedents that are discourse topics but not sentence topics will reliably be rated about half a point lower on the 7-point Likert scale than non-topical antecedents. For der, on the other hand, the effect is about half the size and not reliable.

Figure 8. Model-estimated average responses per condition combination for Experiment 2a (er/der), treating the 7-point Likert response scale like a continuous scale. Error bars indicate 95% credible intervals.

Figure 9. Model-estimated average responses per condition combination for Experiment 2b (er/dieser), treating the 7-point Likert response scale like a continuous scale. Error bars indicate 95% credible intervals.

3.4 Discussion

The results of the second pair of experiments do confirm our predictions overall. In particular, while the results for dieser (Experiment 2b) show an interaction effect that confirms our hypothesis H2 that dieser avoids discourse topical antecedents, the results for der (Experiment 2a) do not show such an interaction, providing evidence for our hypothesis H3 that der is not sensitive to global (discourse) topichood effects. However, some of the details need further inspection. It is unexpected that for both experiments, the context condition has a reliable effect overall, rather than an interaction effect where only the demonstrative pronoun shows an effect due to context. To investigate this further, we split up the datasets for both experiments along the pronoun condition and ran Bayesian mixed-effects models with only context as fixed effect (as well as random intercepts, slopes, and correlations) on them, as with the previous experiments. The results are given in Table 6.

Table 6. Estimated context parameters and one-sided hypothesis tests based on results from Bayesian models run on the datasets from Experiments 2a (er/der) and 2b (er/dieser) split along the pronoun condition.

As can be seen from Table 6, the posterior distributions for the context effect for the er-datasets from both experiments straddle zero, so that it is less than certain that the effect of shifting being better than continuing actually obtains (is non-zero) given the models and the data. For both experiments, it is also clearly smaller than the effect due to context in the demonstrative datasets, for which it can be said to be certain that the effect is non-zero given the data and the models, based on the CrIs and the one-sided hypothesis tests. This is some evidence that the overall context effect found in the models fitted on the complete datasets is mainly due to the fact that it is present for the demonstrative data, while the er-data merely shows a weak trend in the same direction. Note that we thus do not replicate the marginal effect found in Experiment 1 of a preference for the continuing context by er. This is why we are skeptical about this effect also for Experiment 1, but see below for a possible explanation. That we find a reliable effect of context also for der, not just dieser, in the split datasets might be used to argue in favor of an interaction effect actually existing for both sub-experiments and not just Experiment 2b (er/dieser). However, the main results indicate that any interaction effect is clearly smaller for Experiment 2a (er/der) than for Experiment 2b (er/dieser), potentially so much smaller that it is (nearly) non-existent. That there is still possibly some effect could be due to the construction we chose for our precritical sentences: while the target referent in them was not placed initially, it was still realized as a subject and often was an agent. This allows for some leeway to still being interpreted as sentence topic, and such an interpretation is presumably more likely when the same referent has also recently been a sentence topic in a preceding sentence, as is the case in the continuing condition, but not in the shifting condition (since also sentence topichood is context-dependent, cf. Reinhart, 1981). We thus should consider the possibility of mutual influence between sentence and discourse topichood.

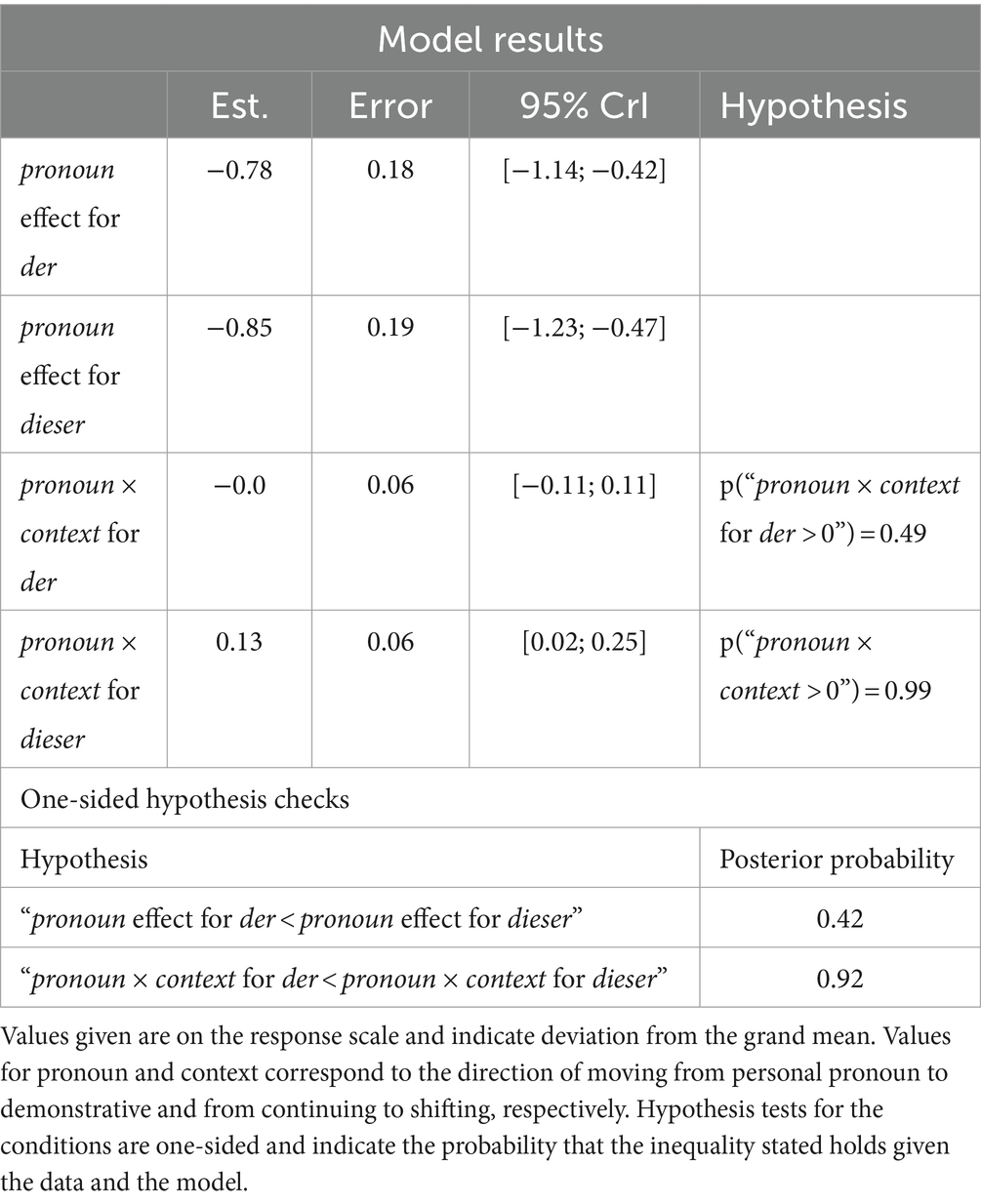

A final point of discussion concerns formality or register. A reviewer suggested that we should run a single analysis on the pooled data from Experiments 2a (er/der) and 2b (er/dieser) together because of doubts that our results might simply be due to the difference in register or formality between der and dieser established in the literature (e.g., Ahrenholz, 2007; Patil et al., 2020). We followed the reviewer’s suggestion and ran a Bayesian mixed-effects model of the same type as the ones used for the individual experiments on the pooled datasets of Experiments 2a and 2b. The model had two fixed effects: Context, with the two levels continuing and shifting, as before, and Pronoun, now with three levels: er, der, and dieser. For details of the model, see the accompanying repository on OSF.8

Since this dataset now includes data for all three pronouns, the results allow us to distinguish between an effect of register/formality and one that goes beyond it: a difference in formality as established in the literature between der and dieser would lead us to expect a main effect of pronoun in the model results, and a reliable difference in the pronoun estimates for der and dieser, in particular.

Such a difference in formality, however, would not lead us to expect to see a difference in the interaction effects pronoun × context for der and dieser, since the continuing and shifting contexts do not differ in their degree of formality. If we therefore find such a difference in the interaction effects, this would mean that there is a difference between der and dieser contingent upon the experimental manipulation—conceivably one along the lines of our proposal in terms of differential sensitivity to more local (sentence) and more global (discourse) topic structure, since that is what the experiments were designed to manipulate.

The relevant model results are summarized in Table 7. They allow us to favor the second scenario: there are reliable effects of pronoun for both der and dieser, but they are clearly very similar. Comparing them directly with one-sided hypothesis checks (with pronoun effect of der < pronoun effect of dieser as the hypothesis) confirms this: the difference is small (estimate = 0.07, CrI = [−0.49; 0.63]), and the probability that the effect of der is actually smaller than that of dieser is only at 0.42, given the data and the model. This gives us very little confidence to claim that der is actually rated better (or worse) than dieser overall, making an explanation along the lines of an overall formality difference less likely since the materials did not differ between the experiments.

Table 7. Model results for the Bayesian mixed-effects model with cumulative link function for the pooled data from Experiments 2a (er/der) and 2b (er/dieser) taken together.

On the other hand, the model does show a reliable effect of interaction for dieser (estimate = 0.13, CrI = [0.02; 0.25]) but not for der (estimate = 0.0, CrI = [−0.11; 0.11]): While the effect for dieser is not huge, the probability that it is larger than zero, given the model and the data, is 0.99. For der, on the other hand, the posterior distribution for the interaction is almost exactly centered on zero. Moreover, comparing the two effects directly confirms this: the probability that the interaction effect for der is smaller than that for dieser, given the data and the model, is at 0.92, according to the one-sided hypothesis check.

This additional direct comparison between der and dieser thus does not lend any support to the idea that the effect we report on is merely due to a difference in register or formality. Rather, it seems to be due to a differential sensitivity to our experimental manipulation and is thus in line with our proposed analysis.

4 General discussion

In this study, we investigated the discourse function of anaphorically used demonstrative pronouns in German. Most studies of the discourse function of demonstrative pronouns compare them with personal pronouns in locally defined ambiguous contexts, i.e., contexts with more than one potential antecedent. These studies find that demonstrative pronouns tend to refer to the less prominent antecedent and to promote the referent to a topical referent in the current sentence, thus signalizing a topic shift. Personal pronouns are more flexible, showing a slight preference for the prominent antecedent, but do not signal topical status in the current sentence (Kaiser and Hiietam, 2004; Kaiser and Trueswell, 2008; Hemforth et al., 2010; Kaiser, 2011; Schumacher et al., 2016; Çokal et al., 2018; Bader and Portele, 2019). In our study, we have extended the research on demonstrative pronouns into two directions: first, we differentiated between global and local discourse structure by assuming that the introduction, the continuation (maintenance), and the shifting of topical referents have to be accounted for both at the global level of discourse topic and the local level of sentence topic. Second, we focused on the contribution of the two demonstrative pronouns der and dieser in German to the topical structure of the discourse in unambiguous contexts, i.e., in discourses with only one appropriate antecedent for the anaphoric pronoun.

This allowed us to formulate three hypotheses, which then guided our experimental task. First, we assumed that personal pronouns are not sensitive to topical structure, either local or global; second, we hypothesized that dieser acts on the global discourse structure as a discourse topic shifter; and third, we assumed that der interacts with the local discourse structure as a marker for a sentence topic. The predictions from these hypotheses are that, first of all, personal pronouns do not show a significant difference in acceptability if we manipulate global and local topic structure, while both demonstratives do. Second, we should find a significant contrast between the use of dieser in a context where only the discourse topic shifts vs. one in which it is continued. And third, we expect that der does not show an effect with respect to the global discourse structure. In order to test these predictions, we designed two acceptability task experiments, consisting of two sub-experiments each (one with der, one with dieser). In each of the sub-experiments, we compared the acceptability of the demonstrative with that of the personal pronoun in order to test the predictions from our hypotheses. In Experiment 1, we manipulated sentence and discourse topic at the same time, creating either contexts where the topic is continued or ones where it is shifted. We predicted that we would not find differences in acceptability for the personal pronoun, but that we would find them for both demonstrative pronouns. In Experiment 2, we only manipulated the discourse topic in order to address the predicted difference between the function of the demonstrative dieser and the demonstrative der. We expected to see context effects with dieser, but not with der and the personal pronoun er.

In both experiments, personal pronouns were judged clearly better than demonstrative pronouns. This was expected, as in unambiguous contexts, the more flexible personal pronoun is preferred. Furthermore, the frequency of personal pronouns is much higher than that of demonstrative pronouns, so a personal pronoun is much more expected. However, we also found an interesting contrast between the two experiments for the personal pronoun. In Experiment 1, where we manipulated both discourse and sentence topic continuation vs. shift, we found a marginal preference for the continuation context. We think that this marginal effect might be a pragmatic effect of the experiments creating a paradigm consisting of a personal pronoun and a demonstrative pronoun. If the demonstrative pronoun has the function of marking topic shift, not using a demonstrative, i.e., using a personal pronoun, implicates continuation. In Experiment 2, this marginal effect was not replicated. Instead, the personal pronoun showed only a numerical preference for the shifting context, i.e., in the same direction as the demonstratives. We take this as support for our view that the effect in Experiment 1 is possibly pragmatic due to the setup. Demonstrative pronouns were found to be less acceptable than personal pronouns in both experiments. They were, however, more acceptable overall in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1. Experiment 2 manipulated only the discourse topic, with the unambiguous antecedent of the anaphoric pronoun in the precritical sentence being in a non-topical position, yielding a local topic shift to the demonstrative in a topical position in the critical sentence. Since we take both demonstratives to prefer such non-topical (non-initial) antecedents, we expected the demonstratives overall to be slightly more acceptable in Experiment 2, especially in the continuing condition. This might make the setup less likely to suggest that the demonstratives are used exclusively for shifts, in turn making it also less likely than in Experiment 1 to implicate a continuation function for the personal pronoun in the experimental paradigm. We therefore think that on balance, both experiments clearly support our H1 that personal pronouns do not depend on the global or local topic structure of a discourse.

With respect to the function of der and dieser, Experiment 1 shows that both demonstratives are reliably better in the shifting condition than in the continuing condition. From this, we can conclude that one function of demonstrative pronouns is that they signal (dieser) or at least contribute to (der) a shift from a non-topical to a topical referent. This also squares well with the finding that they are preferred in ambiguous contexts, i.e., in contexts with two or more potential antecedents, for the less prominent antecedent, as documented in many studies (Kaiser and Hiietam, 2004; Kaiser and Trueswell, 2008; Hemforth et al., 2010; Kaiser, 2011; Schumacher et al., 2016; Çokal et al., 2018; Bader and Portele, 2019). Experiment 2 shows that dieser prefers the (discourse topic) shifting condition, while der does not show this preference. This supports our hypotheses H2 and H3 that dieser marks a global discourse topic shift, while der marks a local topical element (note that in Experiment 1, global and local shifts were manipulated in tandem).