- 1Human Augmentation Research Center, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Kashiwa, Chiba, Japan

- 2Institute of Technology, Shimizu Corporation, Koto-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Introduction: While informal communication is essential for employee performance and wellbeing, it is difficult to maintain in telework settings. This issue has recently been becoming more prominent worldwide, especially because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Nevertheless, how employees managed their informal communication in the sudden shift to teleworking is still understudied. This study fills this research gap by clarifying how an organization's employees improvised informal communication during the urgent shift to teleworking.

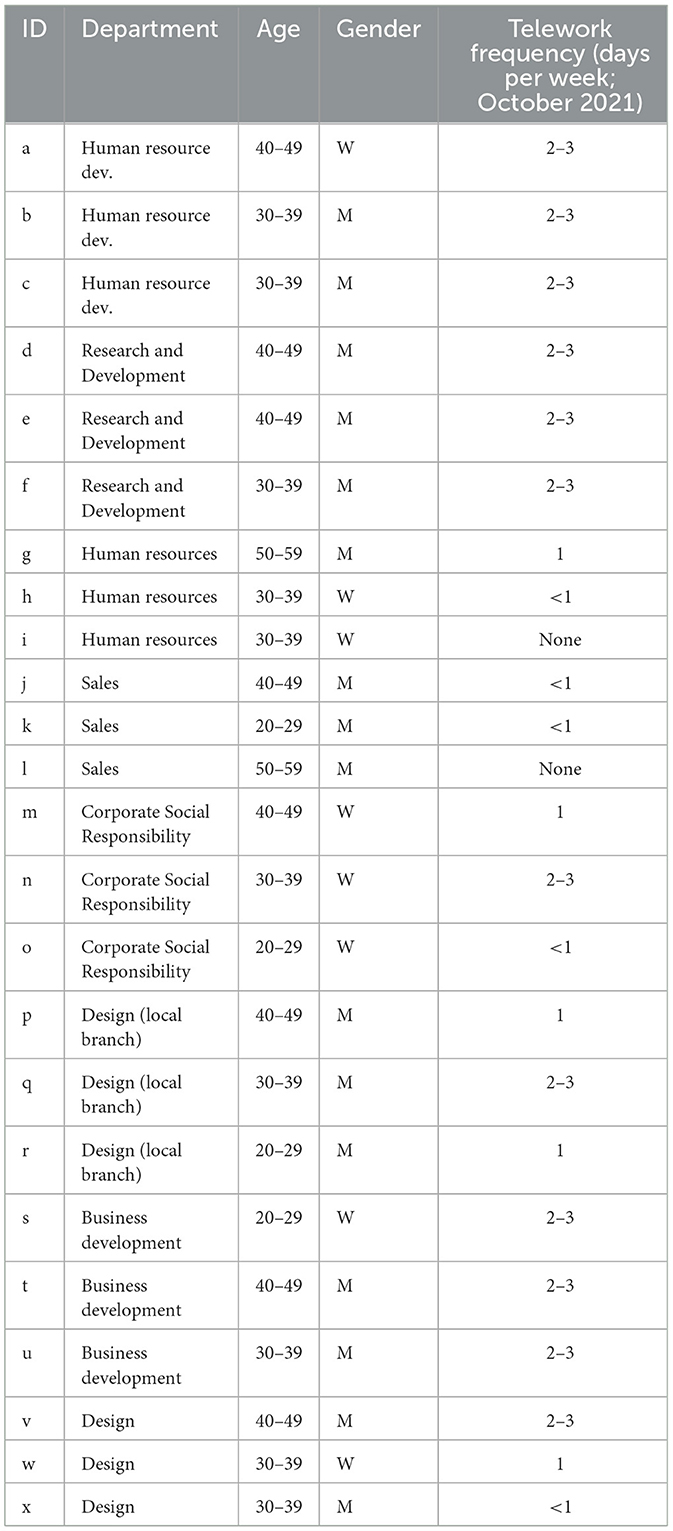

Methods: An exploratory case study of a large construction firm in Japan was conducted, focusing on how employees improvised informal communication during teleworking in response to COVID-19. The authors conducted semi-structured interviews with 24 employees and applied a qualitative thematic analysis to the collected data.

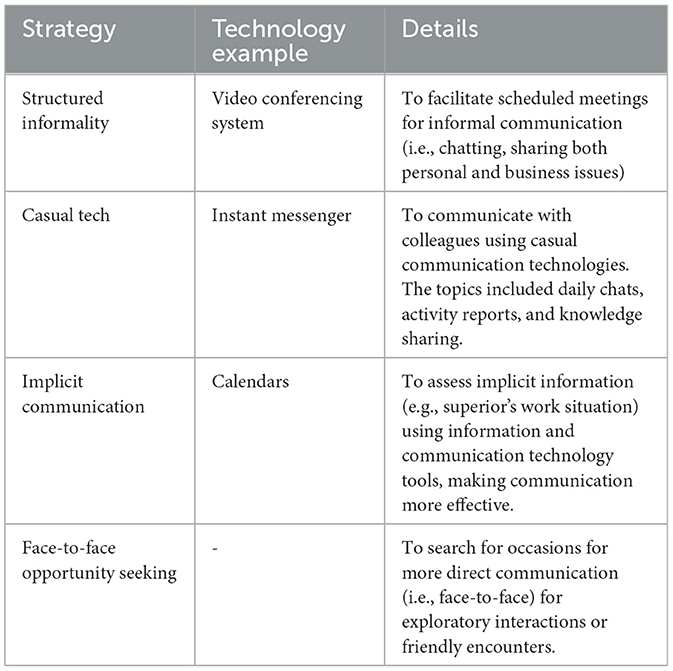

Results: Four informal communication strategies (structured informality, casual tech, implicit communication, and face-to-face opportunity seeking) that were improvised amid the sudden shift to teleworking caused by COVID-19 were identified.

Discussion: The findings can inform concrete means for the effective and dynamic transition of informal communication to teleworking settings during emergencies, thus contributing to informal communication studies as well as the promotion of resilient business operations and employee wellbeing in response to future crises.

1 Introduction

Informal communication in organizations is essential to foster efficient and effective business operations, as well as employee performance and wellbeing. Researchers have addressed its diverse roles in organizations, such as nurturing interpersonal relationships and trust among employees, establishing work culture as a common ground for workplace behavior and relationships, and de-stressing employees through small talk as part of short breaks (Kraut et al., 1990; Fay, 2011; Fay and Kline, 2011).

Informal communication often occurs spontaneously in workplaces. However, unlike office environments, telework settings tend to provide limited opportunities for informal communication (Fay, 2011). The negative impact of such limited opportunities has been discussed, for example, in the context of social and professional isolation (Kurland and Cooper, 2002; Allen et al., 2015). The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has made the negative impact of working in telework settings a common challenge for companies worldwide (Lee et al., 2020; Milasi et al., 2020; Romero-Rodríguez and Castillo-Abdul, 2023). Many companies were forced to move to remote business operations in response to the outbreak and corresponding government containment policies (i.e., lockdowns; Beno and Hvorecky, 2021). Given the speed of these changes, it was difficult to prepare new, comprehensive, and effective communication infrastructure or a company-wide communication policy for telework (Heide and Simonsson, 2021). Employees had to manage their informal communication by themselves, utilizing existing information and communication technologies (ICTs). Their reactions to the changing work situations were ad hoc and situation-dependent (Ruck and Men, 2021). Some scholars have addressed the characteristics of informal communication in teleworking settings in general (Fay, 2011; Viererbl et al., 2022) and the importance of communication in organizational change (Schulz-Knappe et al., 2019). Notwithstanding, few studies have focused on how employees managed their informal communication styles in the sudden shift to teleworking in an emergency such as COVID-19. Considering potential future crises (e.g., another pandemic and other types of disasters), it is essential to crystalize the learning from the latest societal challenge (Lee et al., 2020; Ruck and Men, 2021; Su and Junge, 2023).

This study aimed to address this gap by clarifying effective communication strategies and corresponding challenges for maintaining and even upgrading informal communication in response to the urgent shift to teleworking. The research questions are: how can employees manage and update their informal communication in an urgent shift to teleworking? Are there any effective approaches to maintain informal communication with existing ICT resources? To answer these questions, we conducted a case study of a large construction company in Japan and interviewed employees in a variety of departments. We asked them about how they maintained informal communication and then analyzed the interview data to identify effective informal communication strategies through improvisation using the theoretical lens of informal communication studies as well as media richness theory, which explains the rational process of media selection for communication tasks (Kraut et al., 1990; Webster and Trevino, 1995; Koo et al., 2011).

This study contributes to the research on informal communication, focusing particularly on how informal communication in telework settings can be redeveloped and transformed during the crisis. The dynamics of employee-led informal communication have rarely been discussed in existing studies. This study also offers practical implications for business operations in terms of business continuity and resilience in response to future pandemic-related risks.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the following sections, we first introduce the theoretical background regarding informal communication, ICT use, and teleworking. Then, we introduce the research methodology and case company. After explaining the research findings, we discuss their theoretical and practical implications. Finally, we provide some concluding remarks.

2 Research background

2.1 Informal communication and its characteristics

Informal communication is an ambiguous concept by nature, although its importance has been acknowledged in both research and practice. The role of informal communication in organizational activities is broad. First, informal communication nurtures interpersonal relationships among employees (Kraut et al., 1990; Holmes and Marra, 2004; Fay, 2011). Employees become familiarized and develop trust by getting to know each other through informal communication, which facilitates smooth and effective collaboration. Second, employees can share and stabilize the work culture by discussing ways of thinking and working through informal communication (Kraut et al., 1990; Potter, 2003; Fay, 2011). This increases commitment to the organization and job satisfaction (Fay and Kline, 2011). Third, informal communication delivers information beyond employees' roles and the organizational structure (Nielsen et al., 2000; Koch and Denner, 2022). The perception of being informed increases job satisfaction and productivity (Koch and Denner, 2022). Fourth, informal communication de-stresses employees, contributing to their wellbeing (Lilius, 2012; Viererbl et al., 2022). Informal communication channels can even work as protection in organizational culture of harassment (Johnson, 2023).

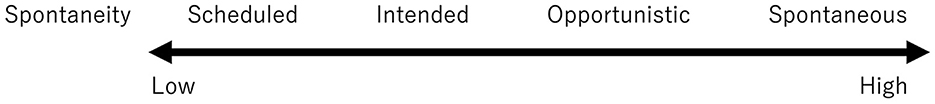

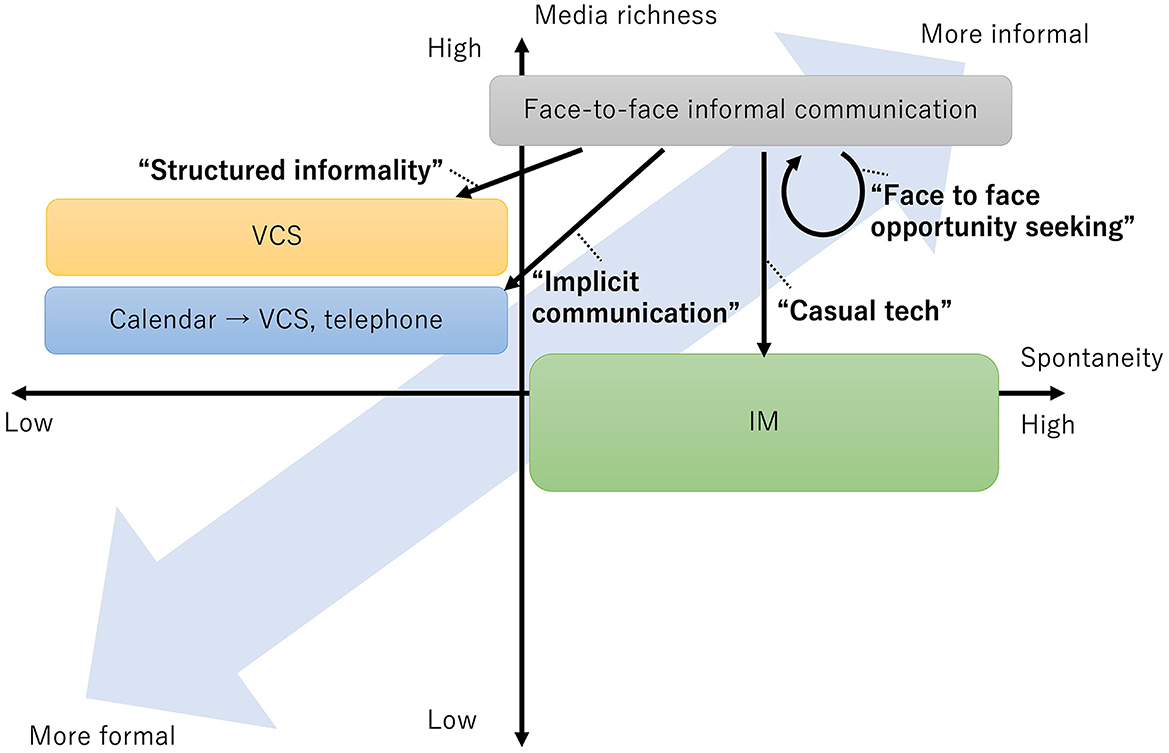

Scholars commonly address the characteristics of informal communication from two perspectives: occasions (i.e., spontaneity) and contents (i.e., work-relatedness; Kraut et al., 1990; Koch and Denner, 2022). The occasions of informal communication are in many cases spontaneous. Kraut et al. (1990) mention that informal communication occurs among employees in an ad hoc manner in comparison to formal communication (i.e., scheduled meetings). According to Kraut et al. (1990), the communication in organizations can be categorized into four types: (1) “scheduled,” as “previously planned,” (2) “intended,” in which “the initiator set out specifically to visit (or access) another party,” (3) “opportunistic,” in which “the initiator had planned to talk (or communicate) with other participants some time and took advantage of a chance encounter to have the conversation,” and (4) “spontaneous,” in which “the initiator had not planned to talk (or communicate) with other participants.” In these categories, spontaneous and opportunistic communications tend to be more informal than the other two (see Figure 1).

Communication in organizations covers a variety of topics—from business to personal issues. Koch and Denner (2022) characterize informal communication by the work-relatedness of contents, referring to it as “any communication in an organization between two or more people who are not interacting in their professional roles but rather in their private roles (e.g., as friends or acquaintances) and who do not intend to solve a work-related task by communicating with each other” (p. 496). They also stress that there is no clear distinction between informal communication and formal communication for “professional roles to achieve work-related goals” (p. 496). Actually, many studies do not explicitly differentiate formal and informal communication based on the contents only (Kraut et al., 1990; Fay, 2011). In this study, we focus on the change of communication with higher spontaneity, for both professional and private roles at workplaces.

2.2 ICT for informal communication

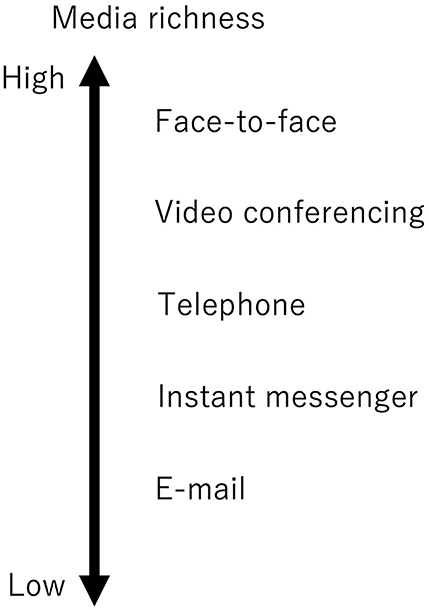

Informal communication is also characterized by its richness (Kraut et al., 1990). While on-site informal communication is mediated by physical proximity (Kraut et al., 1990; Whittaker et al., 1994), the advancement of ICT has driven research into promoting informal communication in remote settings (Fish et al., 1992; Zhao and Rosson, 2009). ICT tools have been investigated for their contribution to internal communication, and workers utilize different types of ICTs depending on their purposes and characteristics (Charoensuk et al., 2014; Romero-Rodríguez and Castillo-Abdul, 2023). According to the media richness theory, one of the most influential theories of media use for communication (Daft and Lengel, 1986; Dennis et al., 2008), rich communication channels contribute to “overcome(ing) different frames of reference or clarify(ing) ambiguous issues to change understanding in a timely manner” (Daft and Lengel, 1986, p. 560), which is generally suitable for informal communication (Kraut et al., 1990). Koo et al. (2011) summarize the characteristics of ICTs (including video conferencing, telephone, instant messenger, and e-mail) using the criteria representing media richness: synchronicity, multiplicity of cues, and language variety. While face-to-face communication is positioned as the highest in media richness (Daft and Lengel, 1986; Koo et al., 2011), video conferencing is characterized by high synchronicity, high multiplicity of cues, and rich language variety (Dennis et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2022). Telephone is limited to verbal communication but is synchronous and rich in cues and language variety (Daft et al., 1987). Instant messenger (IM) aims for synchronous communication but the information to be sent is limited. It is used for intense work-related discussion and coordination as well as socializing (Isaacs et al., 2002). E-mail is asynchronous and has limited cues; however, it is acknowledged as a more formal communication tool (Isaacs et al., 2002; Dennis et al., 2008). As these communication media are listed in the same order for each criterion (Koo et al., 2011), they can be positioned on the axis of media richness integrating these criteria (see Figure 2).

2.3 Transformation of informal communication in teleworking

As workers have increasingly adopted teleworking as a common business practice, the need for informal communication among these distributed workplaces has grown (Fay, 2011; Allen et al., 2015; Charalampous et al., 2019). Teleworking research reports several negative impacts related to the loss of informal communication with coworkers and superiors, such as social and professional isolation and reduced job satisfaction (Dambrin, 2004; Golden and Veiga, 2008; Sardeshmukh et al., 2012). Informal communication satisfaction in teleworking environments has been shown to be positively related to organizational commitment (Fay and Kline, 2011).

As the COVID-19 pandemic forced many companies to shift to teleworking settings, these challenges of remote work settings attracted even more attention (Fana et al., 2020). For example, Yang et al. (2022) analyzed large-scale data relating to internal communication at a large ICT firm and clarified that communication and collaboration became more siloed; opportunities to communicate and collaborate with unfamiliar colleagues decreased. This can be the result of the lack of informal communication with diverse workers at workplaces (Zhao and Rosson, 2009). Maillot et al. (2022) conducted a study with employees under the lockdown policy and reported the negative impact of the lack of informal social relationships on professional exchange. Blanchard (2021) also pointed out that COVID-19 limited informal communication among employees, which especially affected new employees who did not have a strong social relationship with other employees. Okubo (2022) surveyed demographic and occupational factors affecting the use of telework in Japan after the COVID-19 pandemic. The author showed that workers with less teamwork and routine tasks and in telework-friendly work environments (e.g., with rich ICT tools and flextime working systems) used telework more frequently. Other studies have implied the importance of organizational and even governmental support for the smooth transition to remote work (Kurland and Cooper, 2002; Prodanova and Kocarev, 2021).

While research on informal communication during teleworking remains limited, some studies have addressed typical types of informal communication in teleworking settings. Fay (2011) highlights five key topics in informal communication during teleworking, namely personal disclosure, sociality, support-giving and support-getting, commiserating/complaining, and business updates and exchanges. Viererbl et al. (2022) depicted five typical situations where informal communication occurs as follows: (1) pre- and post-meeting talk, (2) parallel chats, (3) follow-up communication, (4) informal talks, and (5) informal meetings. In addition, Heide and Simonsson (2021) highlighted the importance of communicative coworkers in internal crisis communications during the COVID-19 pandemic, although they mainly focused on crisis control communication.

However, these studies do not address how employees can change their informal communication in the urgent shift to teleworking under a disastrous situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In such situations, organizational support and available resources tend to be limited, and workers need to improvise their work practices in adapting to the emerging situation (Weick, 1993; Wiedner et al., 2020). Specifically, available ICTs would become an important resource for informal communication in teleworking (Viererbl et al., 2022). By analyzing the case of communication change in an organization, especially with diverse needs in informal communication, meaningful insights on the transformation of informal communication in response to the emergent shift to teleworking could be obtained.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Case description

To investigate the transformation of informal communication in the process of a sudden shift to teleworking, we conducted a case study of a large construction company in Japan, Shimizu Corporation (Yin, 2002). We adopted an exploratory case study approach for understanding the change in informal communication under COVID-19 (Turnbull et al., 2021).

In response to the acute increase in COVID-19 infections from 2020 to 2021, many Japanese companies (including the case company) shifted to company-wide teleworking (Okubo, 2022). Most employees in the company engaged in teleworking, especially when infection rates remained high. The case company had over 10,000 employees; annual sales are over 1 trillion Japanese yen. Although its main focus is construction, it owns several businesses in other domains.

After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and in response to related government policies, the management of the case company first required all employees to stop working from the office, except those working outside (e.g., sales workers). The case company later stipulated that physical workplaces would be allowed to have a maximum of 30% employee attendance at any time. The company has a diverse range of jobs, and its employees have a range of teleworking experiences, enabling us to capture with richness the dynamics of informal communication under the COVID-19 pandemic. This became a major reason for the case selection of this study. Interviews were conducted just after the fourth state of emergency (July to September 2021) ended and the governmental regulations were relaxed (Okubo, 2022).

To prepare for the shift to teleworking, the case company deployed resources in the form of technology and guidelines. With respect to technology, in addition to basic ICT tools, including e-mail, calendars, and groupware, a video conferencing system (VCS) and IM for business had already been introduced before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, they were not widely used. As for teleworking guidelines, the company had also adopted internal rules for working from home and at third workplaces, such as rental offices, before COVID-19. The rules for working from home were initially aimed to support employees who needed to take care of infants or older parents, and the available dates for teleworking were limited. However, the COVID-19 pandemic led the restrictions to be relaxed and all employees were encouraged to work from home. Concerning internal communication while teleworking, the company provided a general recommendation that there should be sufficient communication among employees.

3.2 Data collection and analysis

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 24 company employees. Table 1 summarizes their profiles. The study was conducted based on the internal regulations according to the determination of non-applicability by the Committee on Ergonomic Experiments of National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (H2021-1161, September 9, 2021). The company includes a variety of departments and we assumed that they would adopt different approaches to improvisation. Hence, we adopted non-proportional quota sampling (Campbell et al., 2020) and asked eight departments to select three interviewees each. Furthermore, as perceptions of teleworking are affected by life stage (Ashforth et al., 2000), we selected participants of varied ages and genders.

This interview study focused on informal communication and how it changed during teleworking. The interviews were related to daily work contents and environments, both at the office and during teleworking; methods and contents of informal communication; changes in communication quality and quantity; and challenges related to communication and collaboration. The interviews were conducted between October 2021 and March 2022. Each interview session lasted ~1.5 h. The interviews were held remotely via a VCS (Microsoft Teams), and all sessions were recorded. The recorded voice data were transcribed and used for analysis. We collected information on interviewees' age, gender, department, and telework frequency through questionnaires (Table 1). Our sample includes some workers with a low frequency of teleworking, which aims at addressing the diverse needs for informal communication among workers who do not utilize teleworking to the same degree. Theoretical saturation, which is commonly described as “the point in data collection and analysis when new incoming data produces little or no new information to address the research question” (Guest et al., 2020, p. 2), was reached with 24 participants. This sample size is within “an organization and workplace research norm of 15–60 participants” (Saunders and Townsend, 2016, p. 836).

We adopted qualitative thematic analysis to analyze the interview data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Qualitative thematic analysis is “a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 79), which is a widely adopted methodology in organizational and communication studies (e.g., Smollan and Morrison, 2019; Jamsen et al., 2022). After getting familiarized with the data, text coding was conducted. We adopted the inductive coding strategy, which is conducted without a prepared coding frame, for exploring diverse factors affecting effective informal communication (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Saldaña, 2009). The coding process, including categorization and theme extraction, was mostly performed by the first author, and the other authors reviewed and confirmed the results (Saldaña, 2009). For text coding, MAXQDA2020 was used. The coding process intended to cover a wide range of topics (Braun and Clarke, 2006), including not only the change in informal communication (e.g., means, objectives, styles, capabilities, and occasions) but also underlying elements such as workstyle (e.g., teamwork), work culture, organizational management, and private life. Based on these codes, we identified key themes that corresponded to the research questions in the form of communication strategies presented in the next section. After careful revision, the final themes and sub-themes were determined.

4 Results

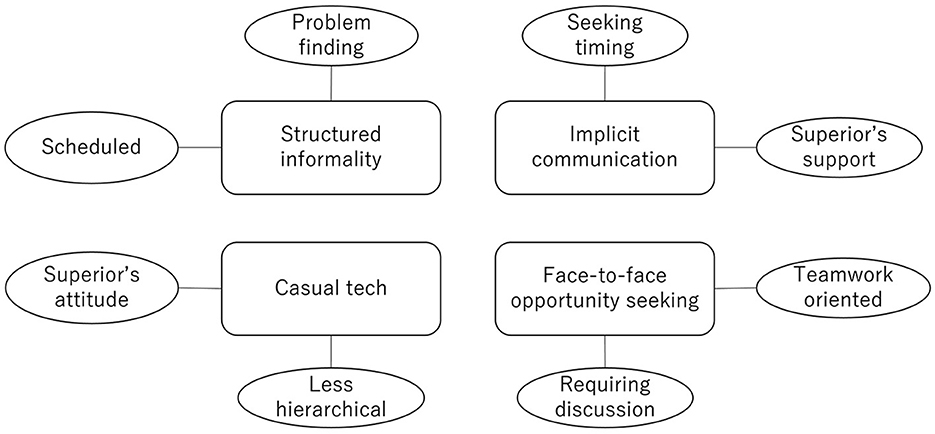

In response to the company-wide shift to teleworking, employees in the case company changed their approach to informal communication, combining different communication channels. We categorized their informal communication strategies as shown in Table 2 and Figure 3.

4.1 “Structured informality” strategy

The “structured informality” (SI) strategy facilitates scheduled meetings for informal communication. The VCS was mainly used for this purpose, being not only a major channel for formal communications (e.g., meetings with colleagues and customers during teleworking) but also informal communications, with team members setting up a specific time for chatting. For example, an interviewee reported that the department had a weekly meeting for informal chats to overcome the lack of communication opportunities. Several other interviewees reported similar types of meetings, which had positive impacts on work, such as allowing workers to identify the need to provide support for coworkers' problems. New employees also communicated using the VCS during their training period to get to know each other.

Nevertheless, another interviewee stated that the practice of holding these routine meetings did not continue for very long, without mentioning a specific reason.

4.2 “Casual tech” strategy

The “casual tech” (CT) strategy applies to the use of casual communication technologies for informal communication. For this purpose, employees mostly used the IM, which was accessible via personal computers and smartphones and had been installed around 2018. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not popular among employees, according to some interviewees. Nonetheless, it became a major tool for informal communication after the pandemic because it could be used casually. It was mostly used for communicating with team members or those with similar interests. Topics discussed over the IM were broad, ranging from daily chatting to activity reporting. Some interviewees mentioned that the read icon was useful to check if members had received the messages. Another interviewee reported using the IM for pre- or post-meeting chats to prepare for or confirm understanding of discussions during the meeting, respectively. Still, not all interviewees said they chatted with other employees outside their team or department. In fact, while some stated that such communication had increased, others disagreed.

Casual communication tools such as the IM were also used to check availability for short meetings. Some interviewees reported that when they wanted to talk on the telephone or VCS, they used the IM beforehand. This applied to both people in the same team and those in other departments.

Yes, when I really want to call, I send a message to ask whether I can call you now. (Corporate social responsibility, hereafter CSR)

I directly call somebody who I always call, like every day. But to people in the same department, who I rarely call, I first ask for their availability. (Human resources)

Some interviewees reported that older employees had also started to use the IM. On the contrary, other interviewees mentioned that the attitudes of their superiors affected their use of the IM. This influence could come from not only explicitly stated notions or attitudes but also unintended and unconscious expressions. Courtesy is another dimension that affected informal communication styles within and beyond the organization. One interviewee said that in departments with a hierarchical culture, employees should refrain from communicating with the superior through the IM.

To be honest, earlier, older employees did not use ICT tools much. However, in such an urgent situation, the older employees also started utilizing these tools out of necessity. (Sales)

[T]he superiors, including me, need to reflect on their belief or bias that face-to-face communication is superior to online communication. They should be aware about how statements such as “face-to-face is good, right?” or “I prefer a face-to-face meeting” stress subordinates… The number of employees mainly working remotely will increase, I think. Hence, it should be communicated that there is no difference between online and face-to-face communication to avoid creating disadvantages for online workers. (Human resource dev.)

4.3 “Implicit communication” strategy

The “implicit communication” (IC) strategy involves utilizing implicit information from existing ICT tools, primarily calendars. Checking the calendar of the person one would like to talk to become a common procedure according to several interviewees. For instance, some said they checked their superior's schedule to find an appropriate time slot to contact them. Other interviewees went further and used it to estimate their superior's work situation based on the topics of their meetings or events, which allowed them to determine the ideal time for communication.

I often check the schedule of the person I want to talk to in advance. Today, this person has this meeting, so it might put them in a bad mood. (Human resources)

Now that our office has become address-free, I have to put more detailed information in my calendar. And I have begun checking my boss' schedule and accordingly decide that “this is the right time.” My boss is working from home and seems to be doing a complicated task, so I should not try to communicate with my boss. Or, the boss seems to be preparing for the report to their superior, so today is not an ideal day to reach out to them. I have become able to speculate about the feelings of the person through their calendar. (Design)

One interviewee in a superior position understood this tactic and made their own schedule available for subordinates to check.

I always input almost all my schedule into my calendar to inform people about my availability, so that [my subordinates] can contact me. (CSR)

4.4 “Face-to-face opportunity seeking” strategy

The “face-to-face opportunity seeking” (OS) strategy involves trying to identify possible opportunities for traditional forms of communication, including face-to-face meetings. Many interviewees considered face-to-face communication important for certain occasions and attempted to make it happen (e.g., at the office or at customer sites). Interviewees from the sales department utilized a rental office as a gathering spot to meet other colleagues and communicate about ongoing business cases. While they utilized the IM for team communication, they highlighted how teamwork was sustained by face-to-face informal communication.

This may be really old-fashioned, but we salespeople have been emphasizing face-to-face meetings. We feel and understand the sentiments during meetings and share them with bosses and subordinates. (Sales)

[I]n the department, three members work as a “line” [team], so everything should be shared for cooperation…. So, rather than acting individually, we cooperate and share information, which takes time and effort…. whether written messages communicate the intended meaning depends on its reader's feeling and comprehension ability. To fill this gap, we suggest face-to-face meetings within the company and with customers. (Sales)

Another preferable occasion for face-to-face meetings is when the meeting topic is unstructured and equivocal, and discussion is expected. An interviewee in the design department reported that face-to-face meetings were required, especially when discussion was needed with reference to proposed designs.

I make drawings of the building, thinking about how the details and facilities should be allocated. Once I have drawn it, I present it to the boss but they always redraw it. “This is not like this, but that,” something like this. This type of interaction cannot occur via e-mail and needs to be face-to-face…. This type of communication comprises 90% of my work communication. (Design)

5 Discussion

5.1 Advantages and disadvantages of improvised informal communication strategies

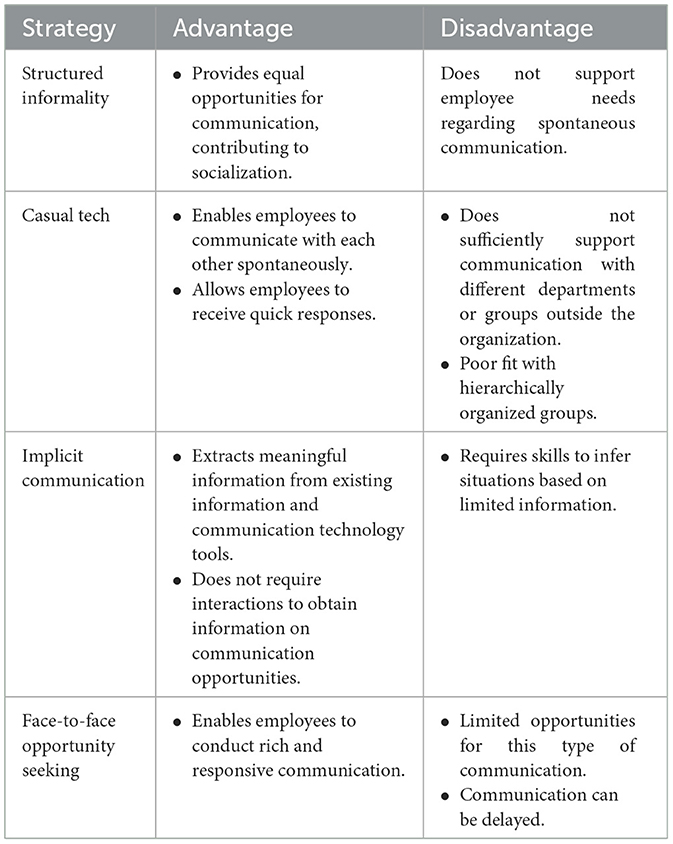

In the case organization, there were no specific organization-wide management policies regarding informal communication and it was redesigned spontaneously in each department. Informal communication strategies were improvised using the available resources to adapt to the urgent shift to teleworking. Common themes relating to employees' communication strategies emerged and were categorized into four types with different advantages and disadvantages (Table 3).

The SI strategy can intentionally create opportunities for communication among employees, including personal issues, which usually occurred in spontaneous or opportunistic manners before COVID-19. This strategy regards such communication as important (Maillot et al., 2022; Viererbl et al., 2022). This strategy was effective for maintaining social relationships among team members and detecting potential problems among coworkers, using VCS with rich communication cues. However, the interviews also indicated that these attempts did not necessarily persist for a long time. This could stem from the spontaneous nature of informal communication, which is not effectively facilitated (at least over the long term) by routine meetings (Fay, 2011; Blanchard, 2021; Viererbl et al., 2022).

By contrast, the CT strategy supports spontaneous communication among employees. This communication style is quick and casual and is especially effective for communication among teams or groups who already have a common understanding and experience (commonly referred to as strong ties; Granovetter, 1983). The IM played a major role in facilitating such informal communication in the organization (Isaacs et al., 2002; Koo et al., 2011). An interesting point was that the IM was already available pre-COVID-19, but was not widely utilized in the case organization. This implies that the sudden move to teleworking drove employees to utilize available resources to facilitate necessary informal communication. Moreover, employees' improvisation against the background of the public health crisis dynamically changed the communication culture (Wiedner et al., 2020). The IM was an instant and easy means of communication and was used for various forms of informal communication, including its wide use to check availability for and organize communication through more “formal” tools (i.e., the VCS and phones).

However, the CT strategy was not effective in extending communication across weak ties, such as those outside of close teams and groups. A previous report provides evidence that corresponds exactly to the situation in this study, highlighting enhanced strong ties and diminished weak ties through communication during teleworking (Yang et al., 2022). The IM was also seen as too “informal” to be used to contact superiors in some departments. This strategy was thus unsuitable for communication between superiors and subordinates, especially in more hierarchically organized departments. These departments required different communication strategies.

The IC strategy tackles this issue by enabling people to estimate the situation and feelings of their counterparts from information in ICT tools before attempting actual communication. In face-to-face settings, employees receive a lot of cues about the situation and the mood of their communication counterpart from aspects of non-verbal communication such as motions (e.g., typing on a computer) and gestures (e.g., looking at the ceiling), which cannot be obtained in remote settings (Fish et al., 1992; Fay, 2011; Maillot et al., 2022). Hence, the subordinates in this case used the calendar to estimate their superiors' work situation and mood. This is interesting in two aspects. First, this is a typical improvisational action in the context of limited resources. Instead of using novel emotion detection or behavior monitoring technologies (Mantello et al., 2023), which were unavailable given the urgent shift to teleworking, the calendar was used to seek communication cues. Second, the calendar was being used beyond its original purpose and communicated different meanings, making it what is often noted as a boundary object (Star and Griesemer, 1989; Star, 2010). The interviewees estimated not only the person's availability but also their situation, which was not explicitly described in the calendar. They speculated about implicit relationships between certain schedules and their influences, and the calendar conveyed such information unintentionally. More interestingly, some superiors even noticed their subordinates' actions in this regard and made their schedules easier to access. Such an improvisation smoothened informal communication among teams and sustained trust among their members (Abrantes et al., 2022).

Nevertheless, implicit intentions or feelings cannot necessarily be understood using such techniques, and current ICT is limited in enabling the communication of non-verbal information. As the findings indicated, the communication of equivocal and implicit information requires face-to-face or similar types of communication, which the media richness theory supports (Daft et al., 1987). The OS strategy covers exactly this. However, the timing of such communication tended to be delayed as it was necessary to find a suitable time for all parties involved. This can become more difficult when many of the workers are out of the office.

Overall, the results imply that none of the extracted strategies covers all aspects of communication. In Figure 4, the identified communication strategies are positioned in the axes of spontaneity and media richness. Figure 4 depicts that when the face-to-face informal communication became mostly unavailable, the identified strategies were adopted as available options during teleworking. Interestingly, highly media-rich tools such as VCS and telephone were used in less spontaneous settings, even with the supplemented communication cue from the calendar in the implicit communication strategy case. This is related to the issue that collecting communication cues may be connected to the surveillance of employees (Manokha, 2020). Instead, the IM, with less media richness, was utilized in more spontaneous situations or less professional communications. Face-to-face communication is not easily replaceable by existing ICTs (Fish et al., 1992; Fay, 2011); hence, the employees selected and combined these strategies with different spontaneity and media richness according to organizational characteristics and communication needs. This rational shift of informal communication through improvisation under the emergent situation is a unique insight from this study.

5.2 Challenges in and support required for adopting informal communication strategies

The findings also indicated that each department adopted slightly divergent communication types that differed by departmental characteristics. Departments emphasizing teamwork rather than individual work preferred more direct and frequent communication strategies such as CT. This finding resonates with that of an existing study in Japan (Okubo, 2022). Meanwhile, hierarchical departments that emphasize showing courtesy to superiors hinder the possibility of employees engaging in informal communication using the CT strategy. These hierarchical departments preferred using the IC and OS strategies.

Moreover, some attitudes of superiors concerning communication styles could negatively impact the shift to informal communication required in this new and distributed working environment. Although interdepartmental differences were not necessarily a problem, they must be considered in order for changes in informal communication to be productive. Furthermore, the results of this improvisation practice may not be necessarily optimal. Its shortcomings should be addressed by organizational support (e.g., leadership education) to increase innovative behaviors according to each department's needs (Vera and Crossan, 2005).

It is also noteworthy that the available communication resources, including technologies and guidelines, had already been implemented in this organization before the COVID-19 pandemic. This meant that there were multiple communication resources available to support informal communication during teleworking. This supports a previous study highlighting the importance of the available resources for coping with disastrous situations through improvisation (Wiedner et al., 2020) and the positive impact of a rich ICT environment for teleworking (Okubo, 2022). Meanwhile, the study also cautions against the over-reliance on ICT and its potential to cause vulnerability in communication and distrust. As described by Swart et al. (2022), a hybrid form of communication combining face-to-face and virtual communications is recommended.

Overall, it is important to reflect on the informal communication practices in each department and improve informal communication within the whole organization (Lee et al., 2020).

6 Conclusion

We investigated changes in informal communication under the impact of COVID-19. The study revealed that four types of informal communication strategies (i.e., SI, CT, IC, and OS) were improvised and selectively combined for the needs of each department. As there was no explicit top-down strategy for informal communication, employees in the case organization used the existing resources and technologies—both previously underused (i.e., the IM) and commonly used (i.e., calendars)—to improvise informal communication.

This study theoretically contributes to existing research on informal communication by identifying four informal communication strategies characterized by different communication occasions and means, based on the existing informal communication studies and media richness theory. Although existing studies have addressed the typical informal communication in teleworking (Fay, 2011; Viererbl et al., 2022), concrete approaches to change informal communication in the urgent shift to teleworking have not been clarified. This study addresses this issue in the form of communication strategies. Moreover, these strategies with different spontaneity and media richness were collectively applied to fill the communication gap caused by the lack of face-to-face communication through improvisation, which would be a meaningful insight from the perspective of media richness theory. This rational process is theoretically meaningful when carefully planned actions cannot be taken in urgent situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. We further specify the advantages and disadvantages of the communication strategies, such that IC through existing technologies can supplement in-person non-verbal communication at offices. These are unique insights that have not been addressed in existing informal communication studies.

As for practical implications, the communication strategies this study suggested, at least some of them would be effective means to sustain informal communication in a future crisis, especially for large firms including diverse jobs and workplace cultures. It is important for organizations to prepare sufficient communication resources (i.e., ICT tools) to ensure that emergency changes to teleworking become effective. The employees in the case organization utilized such resources to respond to and confront the challenges they faced. In addition, personal attitude toward teleworking and organizational culture may affect or even hinder the transition to informal communication in remote work. Accordingly, to facilitate effective communication changes, it may be important to consider the provision of organizational support for individuals and departments, such as education on internal communication for employees and the management as a part of the business continuity plan.

Regarding limitations, this study offers limited generalizability because of aspects related to the organization examined and cultural context. Specifically, the results are based on a single case study in Japan, and the insights we present are affected by the organization's specific characteristics and work culture in Japan (e.g., reliance on informal communication and implicit consensus; Okubo, 2022). Further data from other case studies with different organizational and cultural backgrounds could provide useful additional evidence in this area. Our findings are also attached to the ICTs that were available in the organization at the time of the study. Still, employees may use different communication strategies if new technologies appear and become available in organizations in the future. Hence, the application of emerging technologies, such as virtual offices, needs to be considered by future academicians.

We hope that this study contributes to making business operations resilient when responding to future challenges, such as new disasters or pandemics.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by the Committee on Ergonomic Experiments of National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology for the studies involving humans because of the committee's determination of non-applicability (H2021-1161, September 9, 2021). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board also waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because the institutional requirements allow both oral and written informed consents regarding the interview study with the non-applicability of ethical approval.

Author contributions

KW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. HU: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. IM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SA: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. YY: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Shimizu Corporation and Council for Science, Technology and Innovation, Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP), Development of foundational technologies and rules for expansion of the virtual economy (funding agency: NEDO).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the sincere support of the interview participants.

Conflict of interest

SA and YY are employees of Shimizu Corporation.

The authors declare that this study received funding from Shimizu Corporation. The funder had the following involvement with the study: general approval for conducting the case study and submitting the paper for publication.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abrantes, A., Cunha, M., and Miner, A. (2022). “Overview of the Elgar introduction to organizational improvisation theory,” in Elgar Introduction to Organizational Improvisation Theory, eds. A. Abrantes, M. Cunha, and A. Miner (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 1–17.

Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., and Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psych. Sci. Pub. Interest 16, 40–68. doi: 10.1177/1529100615593273

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., and Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day's work: boundaries and micro role transitions. Academ. Man. Rev. 25, 472–491. doi: 10.2307/259305

Beno, M., and Hvorecky, J. (2021). Data on an Austrian company's productivity in the pre-covid-19 era, during the lockdown and after its easing: to work remotely or not? Front. Commun. 6:641199. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.641199

Blanchard, A. L. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 on virtual working within online groups. Group Proc. Intergroup Rel. 24, 290–296. doi: 10.1177/1368430220983446

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psych. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., et al. (2020). Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 25, 652–661. doi: 10.1177/1744987120927206

Charalampous, M., Grant, C. A., Tramontano, C., and Michailidis, E. (2019). Systematically reviewing remote e-workers' well-being at work: a multidimensional approach. Euro. J. Work Organ. Psych. 28, 51–73. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2018.1541886

Charoensuk, S., Wongsurawat, W., and Khang, D. B. (2014). Business-IT alignment: a practical research approach. J. High Tech. Man. Res. 25, 132–147. doi: 10.1016/j.hitech.2014.07.002

Daft, R. L., and Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Man. Sci. 32, 554–571. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.32.5.554

Daft, R. L., Lengel, R. H., and Trevino, L. K. (1987). Message equivocality. Media selection, and manager performance: implications for information systems. MIS Quart. 11, 355–366. doi: 10.2307/248682

Dambrin, C. (2004). How does telework influence the manager-employee relationship? Int. J. Human Res. Dev. Man. 4, 358–374. doi: 10.1504/IJHRDM.2004.005044

Dennis, A. R., Fuller, R. M., and Valacich, J. S. (2008). Media, tasks, and communication processes: a theory of media synchronicity. MIS Quart. 32, 575–600. doi: 10.2307/25148857

Fana, M., Milasi, S., Napierala, J., Fernández-Macías, E., and Vázquez, I. G. (2020). Telework, Work Organisation and Job Quality During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Qualitative Study. Seville: Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Commission.

Fay, M. J. (2011). Informal communication of co-workers: a thematic analysis of messages. Qual. Res. Organ. Man. 6, 212–229. doi: 10.1108/17465641111188394

Fay, M. J., and Kline, S. L. (2011). Coworker relationships and informal communication in high-intensity telecommuting. J. Appl. Comm. Res. 39, 144–163. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2011.556136

Fish, R. S., Kraut, R. E., Root, R. W., and Rice, R. E. (1992). “Evaluating video as a technology for informal communication,” in SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 3-7 May (Monterey, CA), 37–48.

Golden, T. D., and Veiga, J. F. (2008). The impact of superior-subordinate relationships on the commitment, job satisfaction, and performance of virtual workers. Leader. Quart. 19, 77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.12.009

Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited. Sociol. Theory. 1, 201–233. doi: 10.2307/202051

Guest, G., Namey, E., and Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 15:e0232076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

Heide, M., and Simonsson, C. (2021). What was that all about? On internal crisis communication and communicative coworkership during a pandemic. J. Comm. Man. 25, 256–275. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-09-2020-0105

Holmes, J., and Marra, M. (2004). Relational practice in the workplace: women's talk or gendered discourse? Lang. Soc. 33, 377–398. doi: 10.1017/S0047404504043039

Isaacs, E., Walendowski, A., Whittaker, S., Schiano, D. J., and Kamm, C. (2002). “The character, functions, and styles of instant messaging in the workplace,” in CSCW'02. November 16–20, 2002 (New Orleans, LA), 11–20.

Jamsen, R., Sivunen, A., and Blomqvist, K. (2022). Employees' perceptions of relational communication in full-time remote work in the public sector. Comp. Human Behav. 132:107240. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107240

Johnson, C. A. (2023). The purpose of whisper networks: a new lens for studying informal communication channels in organizations. Front. Commun. 8:1089335. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1089335

Koch, T., and Denner, N. (2022). Informal communication in organizations: work time wasted at the water-cooler or crucial exchange among co-workers? Corp. Comm. Intern. J. 27, 494–508. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-08-2021-0087

Koo, C., Wati, Y., and Jung, J. J. (2011). Examination of how social aspects moderate the relationship between task characteristics and usage of social communication technologies (SCTs) in organizations. Int. J. Info. Man. 31, 445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2011.01.003

Kraut, R. E., Fish, R. S., Root, R. W., and Chalfonte, B. L. (1990). “Informal communication in organizations: form, function, and technology,” in People's Reactions to Technology: in Factories, Offices, and Aerospace, eds. S. Oskamp and S. Spacapan (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications), 145–199.

Kurland, N. B., and Cooper, C. D. (2002). Manager control and employee isolation in telecommuting environments. J. High Tech. Man. Res. 13, 107–126. doi: 10.1016/S1047-8310(01)00051-7

Lee, G. K., Lampel, J., and Shapira, Z. (2020). After the storm has passed: translating crisis experience into useful knowledge. Organ. Sci. 31, 1037–1051. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2020.1366

Lilius, J. M. (2012). Recovery at work: understanding the restorative side of “depleting” client interactions. Acad. Man. Rev. 37, 569–588. doi: 10.5465/amr.2010.0458

Maillot, A.-S., Meyer, T., Prunier-Poulmaire, S., and Vayre, E. (2022). A qualitative and longitudinal study on the impact of telework in times of COVID-19. Sustainability 14:8731. doi: 10.3390/su14148731

Manokha, I. (2020). COVID-19: teleworking, surveillance and 24/7 work. Some reflexions on the expected growth of remote work after the pandemic. Polit. Anthropol. Res. Int. Soc. Sci. 1, 273–287. doi: 10.1163/25903276-BJA10009

Mantello, P., Ho, M. T., Nguyen, M. H., and Vuong, Q. H. (2023). Bosses without a heart: socio-demographic and cross-cultural determinants of attitude toward emotional AI in the workplace. AI. Soc. 38, 97–119. doi: 10.1007/s00146-021-01290-1

Milasi, S., González-Vázquez, I., and Fernández-Macías, E. (2020). Telework in the EU Before and After the COVID-19: Where We Were, Where We Head To. European Institute for Gender Equality. Available online at: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/jrc120945_policy_brief_-_covid_and_telework_final.pdf (accessed December 4, 2023).

Nielsen, I. K., Jex, S. M., and Adams, G. A. (2000). Development and validation of scores on a two-dimensional Workplace Friendship Scale. Educ. Psycho. Measur. 60, 628–643. doi: 10.1177/00131640021970655

Okubo, T. (2022). Telework in the spread of COVID-19. Info. Econ. Policy 60:100987. doi: 10.1016/j.infoecopol.2022.100987

Potter, E. E. (2003). Telecommuting: the future of work, corporate culture, and American society. J. Labor Res. 24, 73–84. doi: 10.1007/s12122-003-1030-1

Prodanova, J., and Kocarev, L. (2021). Is job performance conditioned by work-from-home demands and resources? Tech. Soc. 66:101672. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101672

Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., and Castillo-Abdul, B. (2023). Guest editorial: digitalization of corporate communications: a multi-stakeholder approach. Corp. Com. Intern. J. 28, 176–179. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-03-2023-173

Ruck, K., and Men, L. R. (2021). Guest editorial: internal communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Comm. Man. 25, 185–195. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-08-2021-163

Sardeshmukh, S. R., Sharma, D., and Golden, T. D. (2012). Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: a job demands and job resources model. New Tech. Work. Employ. 27, 193–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00284.x

Saunders, M. N. K., and Townsend, K. (2016). Reporting and justifying the number of interview participants in organization and workplace research. Br. J. Man. 27, 836–852. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12182

Schulz-Knappe, C., Koch, T., and Beckert, J. (2019). The importance of communicating change: identifying predictors for support and resistance toward organizational change processes. Corp. Comm. Intern. J. 24, 670–685. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-04-2019-0039

Smollan, R. K., and Morrison, R. L. (2019). Office design and organizational change. J. Organ. Change Man. 32, 426–440. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-03-2018-0076

Star, L. S. (2010). This is not a boundary object: reflections on the origin of a concept. Sci. Tech. Human Val. 35, 601–617. doi: 10.1177/0162243910377624

Star, S. L., and Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, 'translations' and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Soc. Stud. Sci. 19, 387–420. doi: 10.1177/030631289019003001

Su, W., and Junge, S. (2023). Unlocking the recipe for organizational resilience: a review and future research directions. Eur. Man. J. 41, 1086–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2023.03.002

Swart, K., Bond-Barnard, T., and Chugh, R. (2022). Challenges and critical success factors of digital communication, collaboration and knowledge sharing in project management virtual teams: a review. Intern. J. Info. Sys. Proj. Man. 10, 59–75. doi: 10.12821/ijispm100404

Turnbull, D., Chugh, R., and Luck, J. (2021). The use of case study design in learning management system research: a label of convenience? Intern. J. Qual. Methods 20:148. doi: 10.1177/16094069211004148

Vera, D., and Crossan, M. (2005). Improvisation and innovative performance in teams. Organ. Sci. 16, 203–224. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0126

Viererbl, B., Denner, N., and Koch, T. (2022). “You don't meet anybody when walking from the living room to the kitchen”: informal communication during remote work. J. Comm. Man. 26, 331–348. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-10-2021-0117

Webster, J., and Trevino, L. K. (1995). Rational and social theories as complementary explanations of communication media choices: two policy-capturing studies. Acad. Man. J. 38, 1544–1572. doi: 10.2307/256843

Weick, K. E. (1993). The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: the Mann Gulch Disaster. Admin. Sci. Quarterly 38, 628–652. doi: 10.2307/2393339

Whittaker, S., Frohlich, D., and Daly-Jones, O. (1994). “Informal workplace communication: what is it like and how might we support it?,” in CHI94: ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computer Systems. April 1994 (Boston, MA), 131–137.

Wiedner, R., Croft, C., and McGivern, G. (2020). Improvisation during a crisis: hidden innovation in healthcare systems. Br. Med. J. Lead 4, 185–188. doi: 10.1136/leader-2020-000259

Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S., Suri, S., Sinha, S., Weston, J., et al. (2022). The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 43–54. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4

Keywords: informal communication, teleworking, improvisation, media richness theory, information and communication technology

Citation: Watanabe K, Umemura H, Mori I, Amemiya S and Yamamoto Y (2024) Transforming informal communication in the urgent shift to teleworking: a case study in Japan. Front. Commun. 9:1361426. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1361426

Received: 26 December 2023; Accepted: 18 March 2024;

Published: 05 April 2024.

Edited by:

Komal Khandelwal, Symbiosis International University, IndiaCopyright © 2024 Watanabe, Umemura, Mori, Amemiya and Yamamoto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kentaro Watanabe, a2VudGFyby53YXRhbmFiZUBhaXN0LmdvLmpw

Kentaro Watanabe

Kentaro Watanabe Hiroyuki Umemura

Hiroyuki Umemura Ikue Mori

Ikue Mori Saya Amemiya

Saya Amemiya Yuji Yamamoto

Yuji Yamamoto