- 1Communication University of China, Beijing, China

- 2South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China

With the growing significance of social media in disseminating destination images, short videos have emerged as the primary channel through which tourists acquire destination information. In China, local governments at all administrative levels have begun to explore how to portray a more accurate and diverse destination image through short video platforms, which has become a pressing issue today. This study utilizes a combination of manual analysis (subject terms classification) and computer-assisted techniques (key-frame extraction and text mining) to examine the short videos posted on the TikTok (Douyin) platform by the integrated media centers of Minhou County, Yongtai County, Minqing County, and Lianjiang County in Fuzhou City, China. The objective is to explore the shared characteristics and variations in the dimensional aspects of destination images. The findings reveal that the short video contents released by the governmental new media accounts in these four counties primarily highlight three dimensions: stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and regional landscapes. These dimensions are evident in both descriptive texts and visual symbols. However, in terms of the presented destination image, a notable degree of homogeneity is observed, and there is a lack of emphasis on uncovering and presenting the cultural dimensions, thus failing to reflect the distinctive local characteristics fully. Consequently, it is essential for local integrated media centers to thoroughly explore the cultural uniqueness of their respective regions and enhance the development of thematic dimensions in creating short video content. This approach will effectively strengthen tourists’ association with and perception of destination images.

Introduction

In recent years, the rapid development of mobile Internet has significantly enhanced the communication impact of social media. Unlike when travelogs and blogs relied on text and photos to present destination images, short videos have now emerged as a crucial channel for both domestic and international audiences to obtain information about destinations (Wang et al., 2020). The destination image plays a pivotal role in influencing the choices and decisions of these audiences (Casali et al., 2021). Recognizing the importance of short videos, numerous local authorities, and tourism marketing agencies have established various governmental new media accounts on platforms such as TikTok (Douyin), WeChat, and Weibo (Zhao, 2022). On one hand, potential audiences can benefit from the immersive video content that enhances their travel experiences. It is mainly attributed to the fact that short videos provide tourists with destination cognition and associations, reinforcing their intention to travel (Han et al., 2022; Gan et al., 2023; Jamshidi et al., 2023). On the other hand, short videos offer a richer information format that can convey destination images with greater depth and dimensions (Tussyadiah and Fesenmaier, 2009). Therefore, through social media platforms, short videos visually convey destination information and assist promotion departments and marketing agencies in building robust destination images.

Short videos are typically less than 1 min in duration, with some even shorter, spanning less than 30 s. The TikTok (DouYin) platform plays a crucial role in shaping destination images, influencing visitor behavior, and regulating the visitor experience (Du et al., 2020). Short videos can articulate the imagery of destinations in a concrete visual form, thereby enhancing tourists’ familiarity with the destinations and stimulating their travel behavior (Tan and Wu, 2016; Lin et al., 2021; Camilleri and Kozak, 2022; Wang et al., 2022). Currently, there have been limited studies on utilizing short videos to shape and disseminate destination images. While many local governments have started recognizing the significance of destination image communication, their lack of communication strategy awareness has led to image homogenization or fragmentation. They often rely on current popular topics, mainstream communication models and key regional resources, resulting in a lack of distinctiveness. Consequently, this study aims to analyze the destination images presented by the four counties’ governments in Fuzhou on TikTok (Douyin)’s new media accounts.

Literature review

Research on social media related to destination image

Destination image encompasses the collective expression of objective knowledge, preconceptions, imaginative ideas, and emotional perceptions held by individuals or groups about a particular place (Lawson and Baud-Bovy, 1977). It represents the summation of beliefs, ideas, and impressions that people associate with a destination (Crompton, 1979). A destination can be described as an area that is larger than a town yet smaller than a country, offering notable tourist attractions, visitor centers, and amenities such as festivals and carnivals (Tosun and Jenkins, 1996). It is essentially a region with a distinct image. Moreover, the destination image can be understood as an interactive system that incorporates ideas, perspectives, emotions, visualizations, and intentions associated with the destination (Tasci et al., 2007).

Currently, destination images are primarily conveyed and projected through social media platforms (Garay, 2019; Rosário and Dias, 2023). In social media, information is multifaceted, interactive, dynamic, and fluid (Zeng and Gerritsen, 2014). The content shared on social media effectively portrays the destination image, including elements such as tagged people, topic tags, web links, photos, and videos (Uşaklı et al., 2017; Bulchand-Gidumal, 2023). Xiao et al. (2020) analyzed photos showcasing tourist attractions in Jiangxi province on Mafemgwo using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling. The study demonstrated that visual content in the photos aids in comprehending the destination image, revealing spatial and temporal heterogeneity in the destination images of Jiangxi based on seasons and geography. Nautiyal et al. (2022) examined the destination image of Rishikesh by analyzing thematic hashtags on Twitter. They found that local governments prefer to project destination images through thematic hashtags such as yoga wellness, Himalayas, adventure tourism, and ecotourism, which in turn assists in the development of social media marketing strategies. Li et al. (2020) analyzed the impact of short food videos on the destination image, using Chengdu as an example. The results indicated that short videos can enhance the attention of potential tourists toward the destination image. In conclusion, destination-related content on social media platforms serves as a significant reference for both internal and external audiences in recognizing the destination image, providing valuable guidance for destination marketing organizations, institutions, and departments engaged in image promotion activities.

Research on short videos related to destination image

Potential tourists’ perceptions play a crucial role in the development of tourism and leisure in a destination. These perceptions encompass various aspects such as the natural environment, infrastructure, and local residents, all of which contribute to the formation of a destination image (Hunt, 1975). Specifically, when it comes to perceptions of destination image, which primarily refer to tourists’ emotional perceptions of destination attributes, positive emotional perceptions can enhance people’s inclination to visit (Baloglu and McCleary, 1999; Molinillo et al., 2018). Short videos serve as a key medium for conveying the destination image, offering effective support for its construction, and establishing perceptual foundations for potential tourists. Therefore, the information conveyed through short videos serves as a valuable reference for studying how tourists perceive the image of a particular place.

Numerous scholars have extensively explored the application of short videos in shaping destination images. Cao et al. (2021) investigated the narrative transfer effect of short videos and discovered that the content of such videos significantly contributes to promoting the destination image. Lim et al. (2012) delved into consumers’ perceptions of user-generated video content versus video content generated by destination marketing organizations. The results revealed that user-generated video content predominantly focused on adult entertainment, overall experience, and video and music reviews, while destination marketing organization-generated video content emphasized aspects such as city nightlife, gaming, adult entertainment, overall experience, food, and clubs. The study also highlighted that consumers perceive these two categories differently. Shao et al. (2019) examined the destination image portrayed in user-generated short videos on the TikTok (Douyin) platform, and their findings demonstrated that short videos offer distinct advantages over travel blogs in revealing the destination image. Short videos tend to showcase physical elements such as architecture, nature, and landscapes, whereas travel blogs are more inclined toward cultural and artistic aspects. Overall, most studies analyzing short videos primarily rely on methods such as questionnaire surveys, in-depth interviews, and discourse analysis. Few studies have focused on specific image feature extraction within short videos to uncover how they present destination images, let alone investigating short videos posted by government new media accounts. Consequently, it is particularly crucial to extract image features from the content of short videos posted by government new media accounts to unveil how government agencies construct destination images.

Based on the above discussion, this study aims to address the following two aspects:

RQ1: What are the trends observed in the destination images portrayed in the short videos posted by the four integrated media centers on their TikTok (Douyin) accounts?

RQ2: What are the variations and distinctions in the destination images depicted in the short videos shared by the four integrated media centers through their TikTok (Douyin) accounts?

Methodology and data

Cases selection

Fuzhou City is situated on the southeastern coast of China and encompasses six municipal districts and six counties within its jurisdiction. Among them, Minhou, Lianjiang, Yongtai, and Minqing are county-level regions that attract significant attention from both local and external visitors. These four counties have been selected as the research subjects due to several reasons. Firstly, the integrated media centers of Minhou, Lianjiang, Yongtai, and Minqing counties have posted a substantial number of short videos on the TikTok (Douyin) platform. Secondly, these regions boast abundant tourism resources, ensuring that visitors, both from the surrounding areas and beyond the province, can have a relatively comprehensive tourism experience. Taking these factors into account, this study will adopt a government agency perspective to examine the content of short videos posted by county-level integrated media centers in the four aforementioned counties of Fuzhou. The aim is to explore the focal points and differences in how local government agencies construct destination images.

Data preparation

The short videos on the TikTok (Douyin) platform were selected as the primary research material for several reasons. Firstly, TikTok (Douyin) enjoys broad influence and boasts a sizable user base, making it an important channel for domestic audiences to familiarize themselves with the destination’s image. Many governmental new media accounts regularly publish local information on TikTok (Douyin), facilitating the collection of short video data for the research. Secondly, TikTok (Douyin) users provide relevant information about the videos during the uploading process, including tags, description text, and topics. This feature provides convenient conditions for conducting the study.

For this study, the research material consists of short video content released by the social media accounts of “Minhou Culture and Tourism, Meet Minhou, Great Beauty Yongtai, Yongtai Nature, New Minqing, and Lianjiang County Integrated Media Center.” The collection of short videos spans from the first video released by these accounts up until December 31, 2022, covering the years 2020, 2021, and 2022. A total of 988 videos were collected from Minhou Cultural Tourism and Meet Minhou, 210 videos from Great Beauty Yongtai and Yongtai Nature, 883 videos from New Minqing, and 328 videos from Lianjiang County Integrated Media Center. After the data underwent effective screening and cleaning, a total of 1767 videos were ultimately obtained.

Research processes

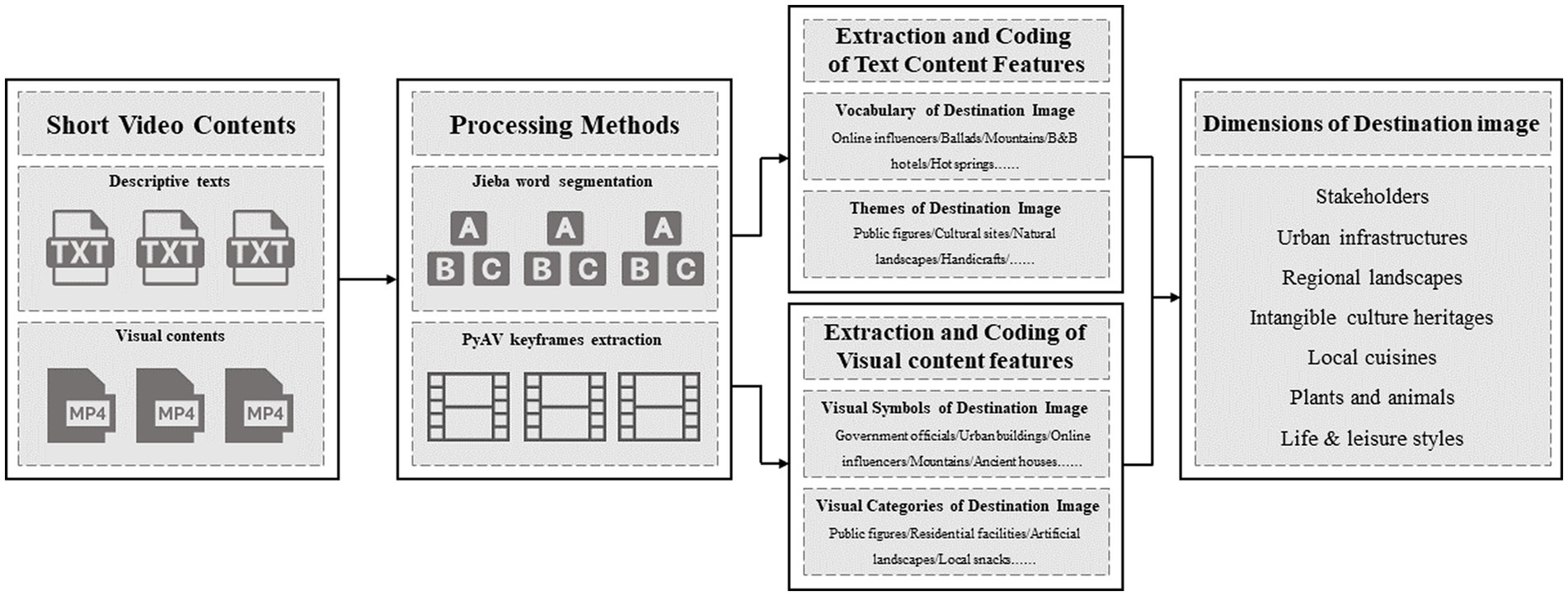

This study is divided into three main stages. Firstly, an analysis of the descriptive texts of the short videos is conducted, focusing on the themes and dimensions of the images conveyed through the textual vocabulary. This analysis aims to uncover the communication trends of county-level governmental new media accounts in terms of textual content. Secondly, the primary visual symbols depicted in the short videos are manually coded through judgment-based categorization and clustering. This process involves extracting the key dimensions of the destination image based on the classification and clustering of visual symbols. Lastly, a comparison is made between the descriptive texts of the short videos and the visual symbols to examine how destination images are projected. This comparison allows for the identification of similarities and differences between the textual and visual contents (Figure 1).

Technical means

Considering that this study involves the analysis of both visual content and textual material in short videos, a content analysis method will be utilized for correlation analysis. The descriptive text of the short videos will primarily undergo pre-processing using Jieba Chinese text segmentation, a technique in the field of computer natural language processing. In addition, the visual content analysis of the short videos is complemented by computer-assisted keyframe extraction. The extracted keyframe images will then be manually assessed and labeled to determine the main dimensions of the destination image.

Descriptive text analysis of short videos

Content analysis is a widely employed research method for providing objective, systematic, and quantitative descriptions of information (Zhang et al., 2020). It is particularly useful for analyzing explicitly obtained content, such as words, to determine the viewpoints expressed in the text. In this study, the Jieba Chinese text segmentation, commonly used in the field of natural language processing, is utilized to disambiguate the descriptive text of short videos. This process involves stemming extraction and word frequency statistics, which contribute to extracting keywords related to the destination image. This step aims to explore how the descriptive text influences the formation of the destination image.

Content analysis of short videos

Video content analysis is a commonly used method for examining video content. In this study, the focus is on extracting keyframes from short videos and identifying visual symbols related to destination images based on these keyframes. The aim is to compare the symbolic representations in the content published by the four local governmental new media accounts. The FFmpeg wrapper library PyAV, which is a video decoding tool, will be employed to extract the main keyframes. This process converts the dynamic keyframes of the short videos into pseudo-static images, enabling the statistical analysis of visual symbols in the main content. To ensure accuracy, redundant keyframes will be eliminated from the 1767 short videos analyzed using the aforementioned approach. From Meet Minhou and Minhou Cultural Tourism, a total of 12,841 keyframes were extracted, while 3,097 keyframes were obtained from Great Beauty Yongtai and Yongtai Nature. Additionally, 8,619 keyframes were extracted from the short videos released by New Minqing, and 3,038 keyframes were obtained from those released by Lianjiang County Integrated Media Center. Furthermore, the main visual symbols appearing in the keyframes are counted in a manual count without repetition, which means that the same visual symbol is counted only once for repeated occurrences in the keyframes extracted from the short video.

Analysis and finding

Dimensional division of destination image

In destination image research, it is important to note that there is no single framework that can encompass all dimensions of a destination image, nor is there a clear delineation that can accurately categorize its attributes. When considering the dimensional division of a destination image, it is crucial for a region that seeks to establish a strong brand to be perceived by both internal and external audiences. Researchers such as Hanna and Rowley (2011) argue that constructing an image requires the development of local infrastructure and the active involvement of various stakeholders. Hankinson (2004) proposes three potential attributes for regional image perception: functional attributes, which include museums, art galleries, sports facilities, and public transportation; symbolic attributes, which involve local residents, tourists, and service workers; and experiential attributes, which encompass visitor experiences, the destination’s atmosphere, and environmental characteristics. Stepchenkova and Zhan (2013) suggest that destination image attributes can be categorized into areas such as the natural environment, people, architecture, cityscape, and cuisine. Mak (2017) conducted a content analysis by analyzing official and unofficial photographic data, classifying destination image attributes into categories such as the natural environment, infrastructure, culture, and art. Therefore, by combining the existing destination image classification with the textual vocabulary and visual symbols presented in short videos, this study aims to classify and cluster destination images characterized by the content shared by governmental new media in the four counties of Fuzhou.

Among the classification criteria for descriptive text and visual content, the following principles are primarily followed: (1) Grouping the same or similar text words and visual symbols into one category. For instance, under the theme of public figures, textual information may include artists, athletes, singers, stars, and masters, while visual symbols may encompass actors, stars, netizens, etc., all falling under the category of public figures. (2) Eliminating text words and visual symbols that are unrelated to the destination image. This includes removing adverbs, adjectives, and other related words in the text information, as well as symbols that are clearly not directly associated with the construction of the destination image, such as lanterns and umbrellas appearing in the short video. Based on the aforementioned classification principles, a total of seven destination image dimensions were identified: stakeholders, urban infrastructures, regional landscapes, intangible cultural heritages, local cuisines, plants & animals, and life & leisure styles.

Destination image in descriptive text

When users upload short videos to the TikTok (Douyin) platform, they typically need to perform operations such as providing work descriptions, tagging topics, mentioning friends (@friends), and selecting locations. Work descriptions often contain valuable destination information, including word preferences and topic choices that describe the content of the short videos. Therefore, to analyze the descriptive text of the short videos, Jieba Chinese text segmentation is used to generate an output in the format of “words + word frequency.” After eliminating words that are not relevant to the destination image, such as adverbs, verbs, and verbal nouns, a total of 203 keywords were identified for Minhou County, 56 keywords for Yongtai County, 180 keywords for Minqing County, and 111 keywords for Lianjiang County.

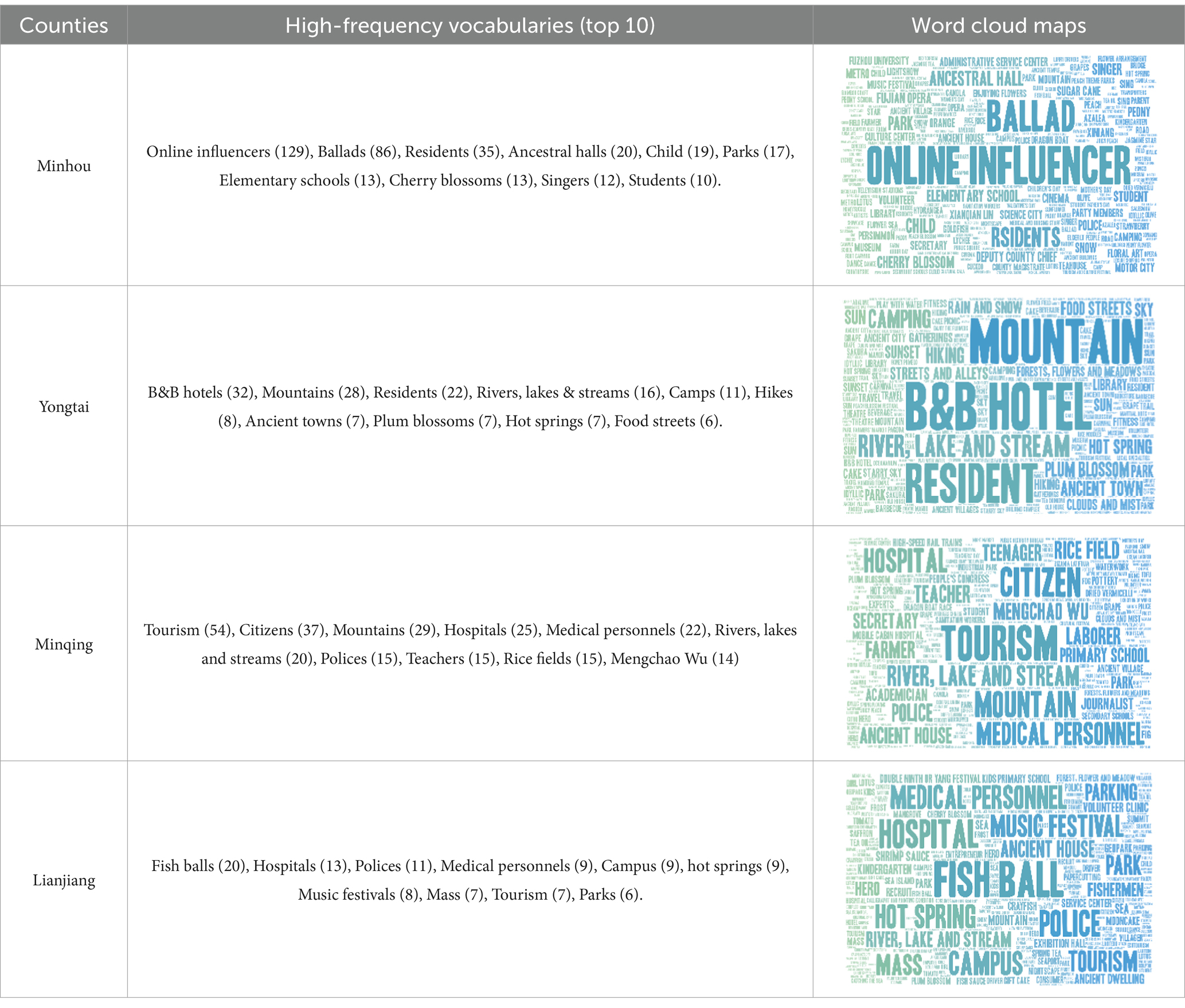

High-frequency words in descriptive texts

Through summarization, the top 10 high-frequency words appearing in the descriptive texts of Minhou County’s governmental new media are as follows: online influencers (129 times), ballads (86 times), residents (35 times), ancestral halls (20 times), child (19 times), parks (17 times), elementary schools (13 times), cherry blossoms (13 times), singers (12 times), and students (10 times). According to the seven dimensions organized above, the top 10 high-frequency words are corresponded one by one, and it can be observed that the dimensions involved in the high-frequency words are stakeholders, intangible cultural heritages, urban infrastructures, and plants and animals. For Yongtai County, the top 10 high-frequency words in the descriptive texts are B&B hotels (32 times), mountains (28 times), residents (22 times), rivers, lakes and streams (16 times), camps (11 times), hikes (8 times), ancient towns (7 times), plum blossoms (7 times), hot springs (7 times), and food streets (6 times). These words mainly pertain to the four dimensions of urban infrastructures, regional landscapes, stakeholders, and life and leisure styles. For Minqing County, the top 10 high-frequency words in the descriptive texts are tourism (54 times), citizens (37 times), mountains (29 times), hospitals (25 times), medical personnel (9 times), rivers, lakes & streams (20 times), polices (15 times), teachers (15 times), rice fields (15 times), and Mengchao Wu (14 times). These words primarily relate to the four dimensions of life and leisure, stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and regional landscapes. For Lianjiang County, the top 10 high-frequency words in the descriptive texts are fish balls (20 times), hospitals (13 times), polices (11 times), medical personnel (9 times), campus (9 times), hot springs (9 times), music festivals (8 times), mass (7 times), tourism (7 times), and parks (6 times). These words mainly pertain to the four dimensions of local cuisines, urban infrastructures, stakeholders, and life & leisure styles (Table 1).

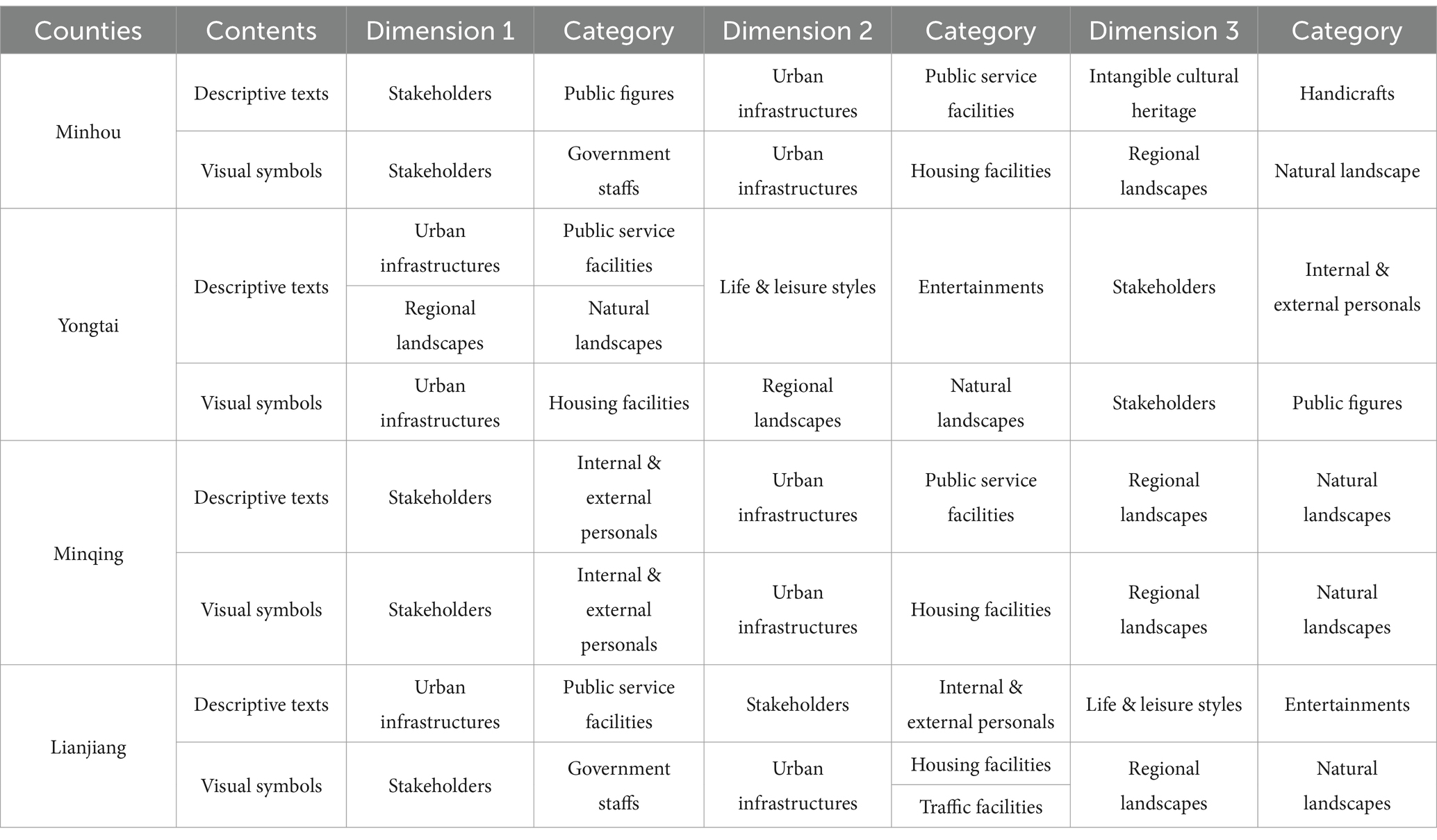

The subject words are presented in the contents released by the four local governmental new media accounts

Regarding the dimensions to which the subject words in the descriptive text of the short videos belong, the top three situations are as follows: For Minhou County, the dimensions include stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and intangible cultural heritages. For Yongtai County, the dimensions include urban infrastructures, regional landscapes, and life & leisure styles, as well as stakeholders. For Minqing County, the dimensions include stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and regional landscapes. Lastly, for Lianjiang County, the dimensions include urban infrastructures, stakeholders, and life & leisure styles.

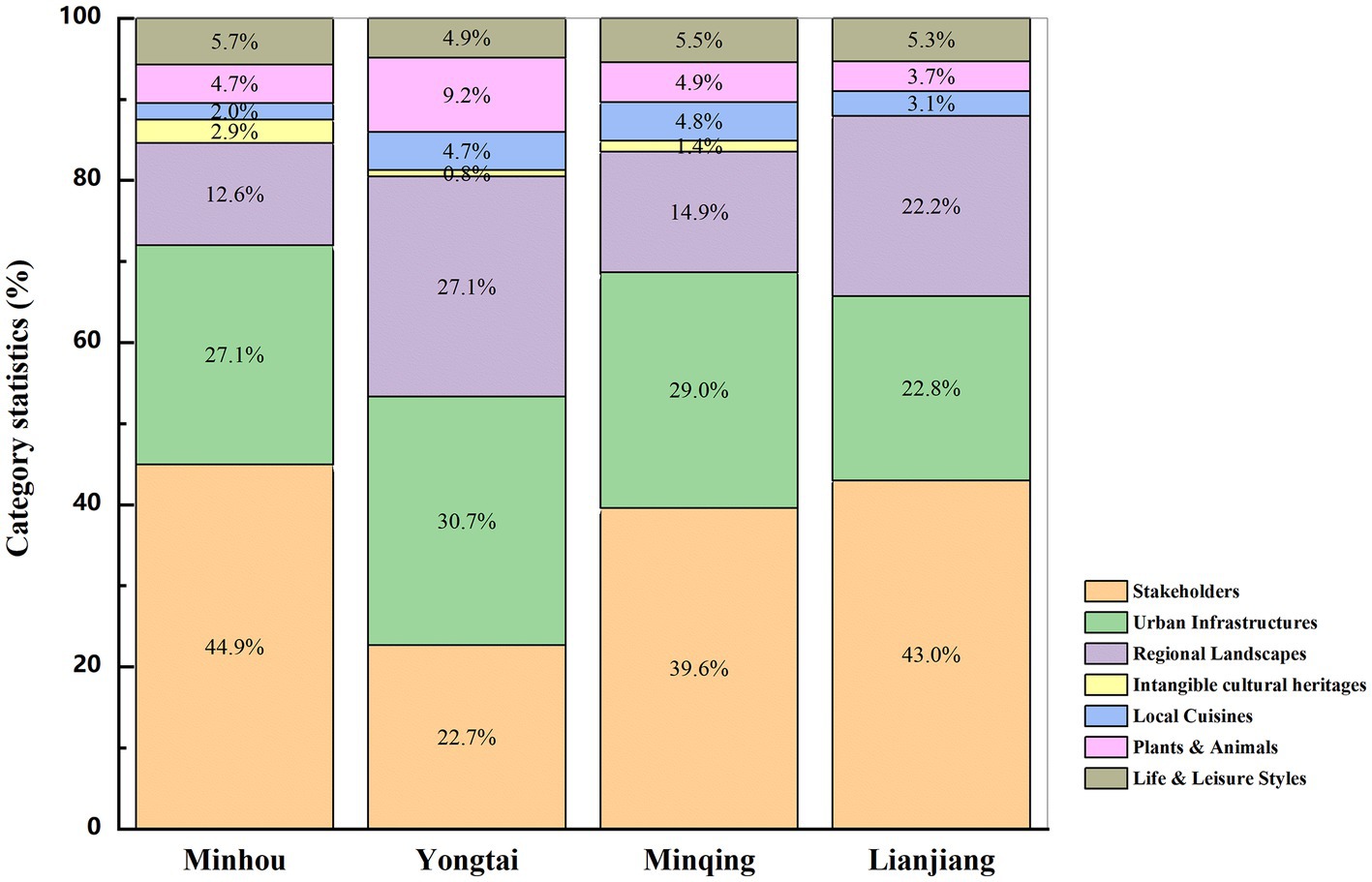

Sort 1: As shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. Minhou County and Minqing County primarily focus on projecting the image of stakeholders. In Minhou County, there is a significant emphasis on public figures (18.1%), while in Minqing County, the projection is mainly directed toward internal & external personal (12.7%), which includes residents, children, and students. Yongtai and Lianjiang counties, on the other hand, prioritize the image projection of urban infrastructures. Both counties predominantly project the image of public service facilities (6.9 and 10.4%), encompassing terms such as B&B hotels, hospitals, and theaters. Moreover, Yongtai County also pays attention to the image projection of regional landscapes, with a major focus on the natural landscapes (29.9%). This thematic category is characterized by mountains, rivers, lakes and streams, forests, flowers & meadows.

Table 2. Comparison of descriptive text in short videos of Minhou, Yongtai, Minqing, and Lianjiang counties.

Sort 2: As shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. Minhou County and Minqing County place their focus on projecting the image of urban infrastructures, with an emphasis on public service facilities (6.9 and 10.7%) in both counties. This projection includes terms such as hospitals, parks, square pods, administrative service centers, and science cities. In contrast, Yongtai County’s image projection revolves around the theme of life & leisure styles, particularly emphasizing entertainment (17.4%). This thematic category encompasses terms such as camps, hikes, and hot springs. In Lianjiang County, the image projection of stakeholders centers around the theme of internal & external personals (10.8%). This theme primarily involves words such as people, fishermen, and consumers.

Sort 3: As shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. The image projection of intangible cultural heritages in Minhou County is primarily focused on the theme of handicrafts (10.7%). This projection includes terms such as ballads, bamboo crafts, and root carvings. In Yongtai County, the image projection of stakeholders is centered around the theme of internal & external personals (9.1%). The term resident is the primary focus in this category. In Minqing County, the image projection of regional landscapes predominantly revolves around the theme of natural landscapes (9.6%). This projection encompasses terms such as mountains, rivers, lakes and streams, clouds, and fog. Finally, in Lianjiang County, the image projection of life & leisure styles mainly centers around the theme of entertainment (10.8%). The terms hot springs, tourism, and catching the sea are the primary elements in this category.

General communication trends are reflected in descriptive texts

In summary, the dimensions derived from the descriptive texts of the short videos can be ranked as follows: (1) stakeholders, (2) urban infrastructures, (3) life & leisure styles, (4) regional landscapes, (5) local cuisines, (6) plants & animals, and (7) intangible cultural heritages. The analysis yields the following conclusions: Firstly, there is a clear communication preference among the governmental new media in the four regions for the dimensions of stakeholders and urban infrastructures in their descriptive texts. In terms of stakeholders, the focus lies on terms such as netizens, online influencers, local celebrities, government officials, and residents. As for urban infrastructures, terms such as campus, parking lots, parks, ancient towns, ancestral halls, and ancient residences take center stage. Secondly, the governmental new media in the four regions emphasize the dimensions of life & leisure styles and regional landscapes. Descriptive texts highlight local entertainment such as hot springs, tourism, camps, as well as natural landscapes including rivers, lakes & streams, mountains, flowers, and meadows. Lastly, local cuisines, plants and animals, and intangible cultural heritages are also considered important dimensions by the governmental new media in the four regions. These dimensions are represented in the descriptive texts of short videos through various categories of vocabulary (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Destination image in visual symbols

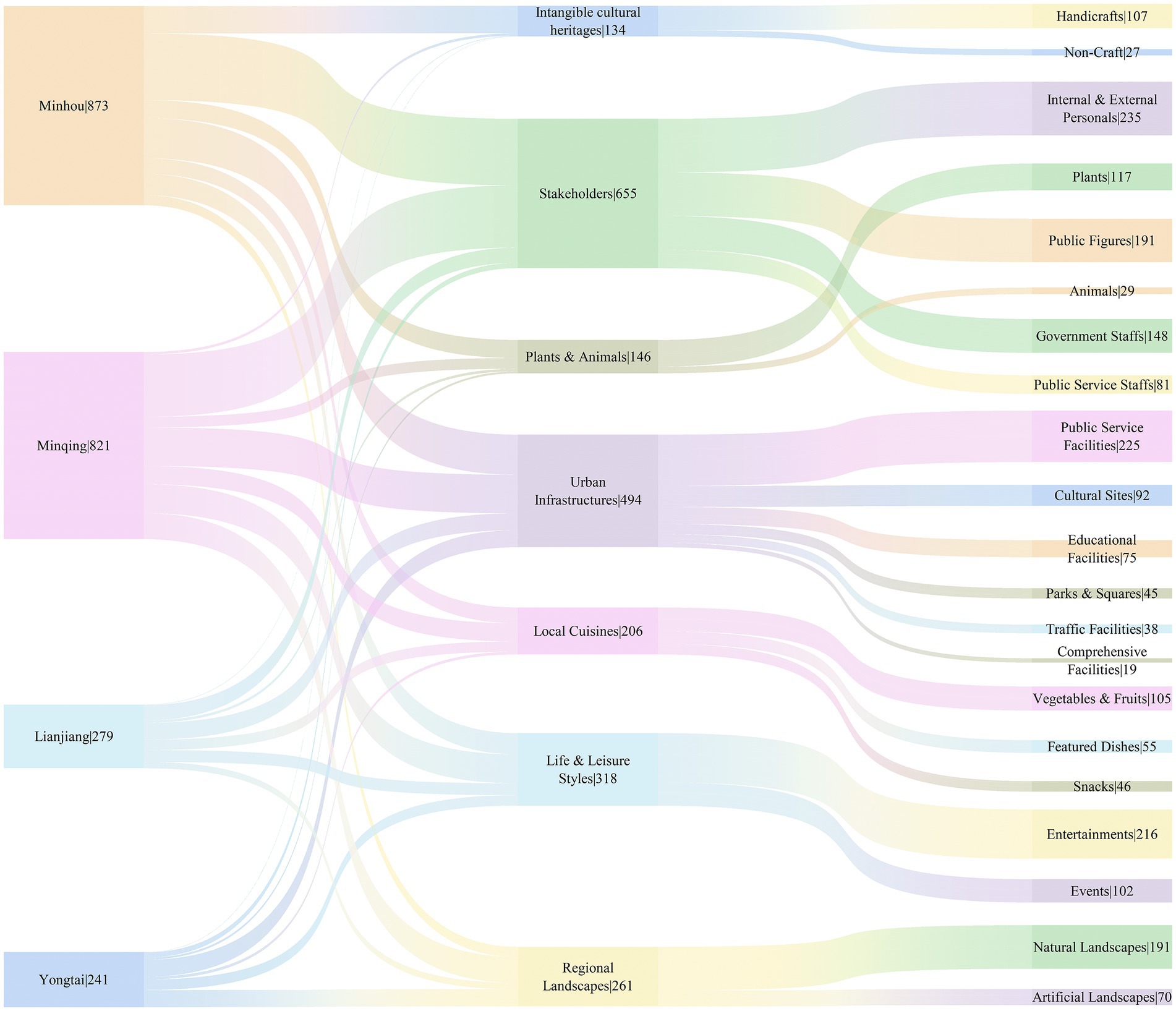

The visual symbol information presented in the short videos is more extensive than the textual information. By sorting through the visual symbols that appear in 12,841 keyframes, a total of 222 main visual symbols were identified. Similar visual symbols with equivalent meanings were grouped together, resulting in 188 visual symbols.

High-frequency visual symbols in short videos

From the analysis of high-frequency visual symbols, the top 10 visual symbols appearing in short videos of Minhou County’s governmental new media are as follows: government officials (105 times), residents (104 times), local celebrities (98 times), online influencers (86 times), urban buildings (62 times), rivers, lakes & streams (59 times), students (52 times), cultural performances (51 times), flowers (48 times), and ancient houses (42 times). These visual symbols mainly correspond to five dimensions: stakeholders, urban infrastructures, regional landscapes, life & leisure styles, plants and animals. In the short videos of Yongtai County’s governmental new media, the top 10 visual symbols are: rivers, lakes & streams (65 times), Online influencers (62 times), mountains (48 times), villages (35 times), ancient houses (34 times), flowers (23 times), B&B hotels (22 times), residents (21 times), tourists (18 times), and trees (15 times). These visual symbols primarily relate to the dimensions of regional landscapes, stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and plants and animals. In the short videos of Minqing County’s government new media, the top 10 visual symbols are: residents (81 times), government officials (51 times), students (45 times), mountains (40 times), ancient houses (39 times), highways (39 times), epidemic prevention personnel (37 times), villages (34 times), farmlands (31 times), and police (28 times). These visual symbols primarily represent stakeholders, regional landscapes, and urban infrastructures, highlighting the importance of these dimensions. In the short videos of Lianjiang County’s governmental new media, the top 10 visual symbols appearing in short videos are: residents (35 times), government officials (27 times), sea (23 times), epidemic prevention personnels (15 times), online influencers (14 times), ancient houses (14 times), coast (13 times), students (12 times), tourists (12 times), and police (11 times). These visual symbols mainly correspond to the dimensions of stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and regional landscapes (Table 3).

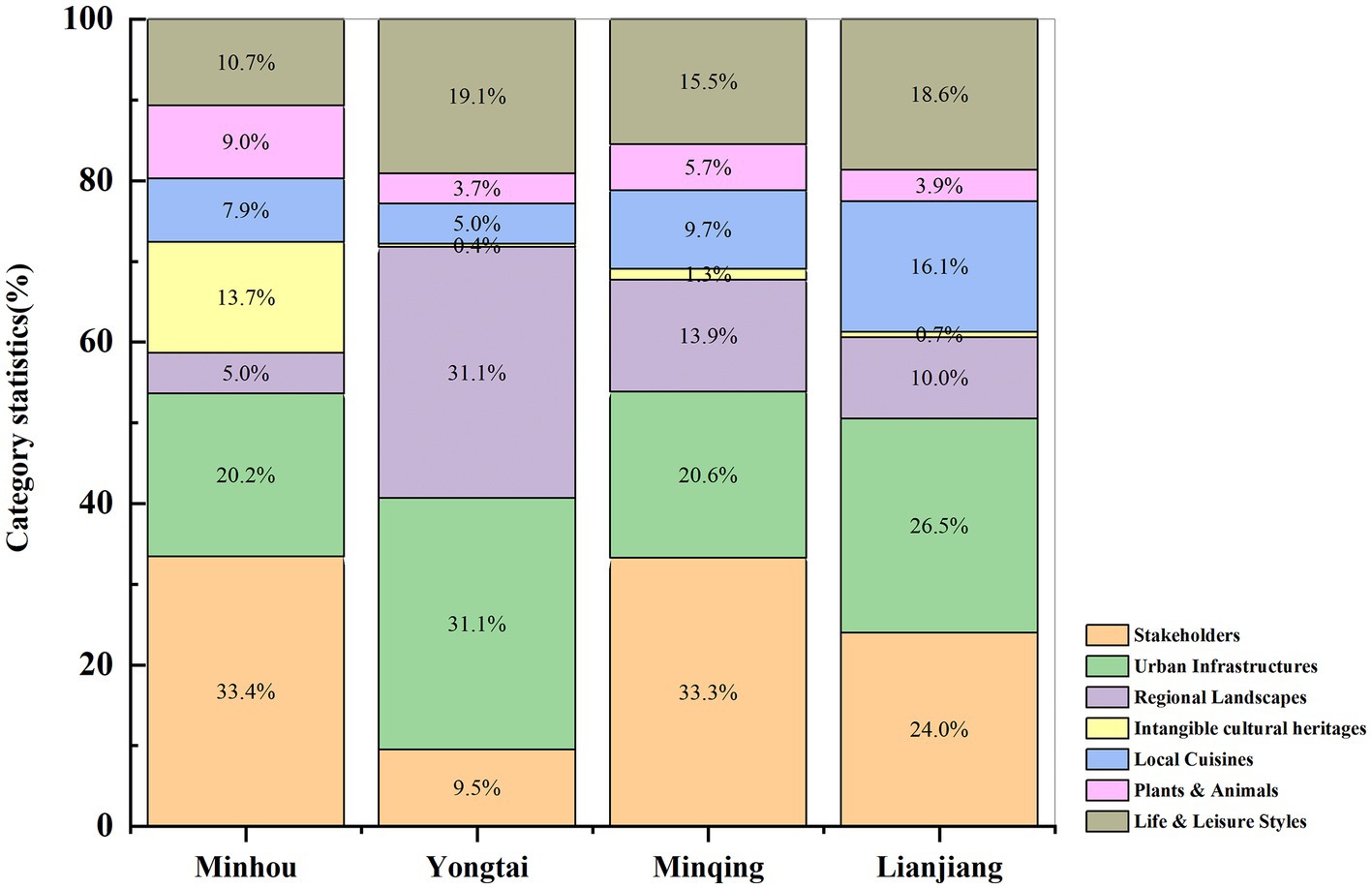

Visual category presentation in the new media of government affairs in counties

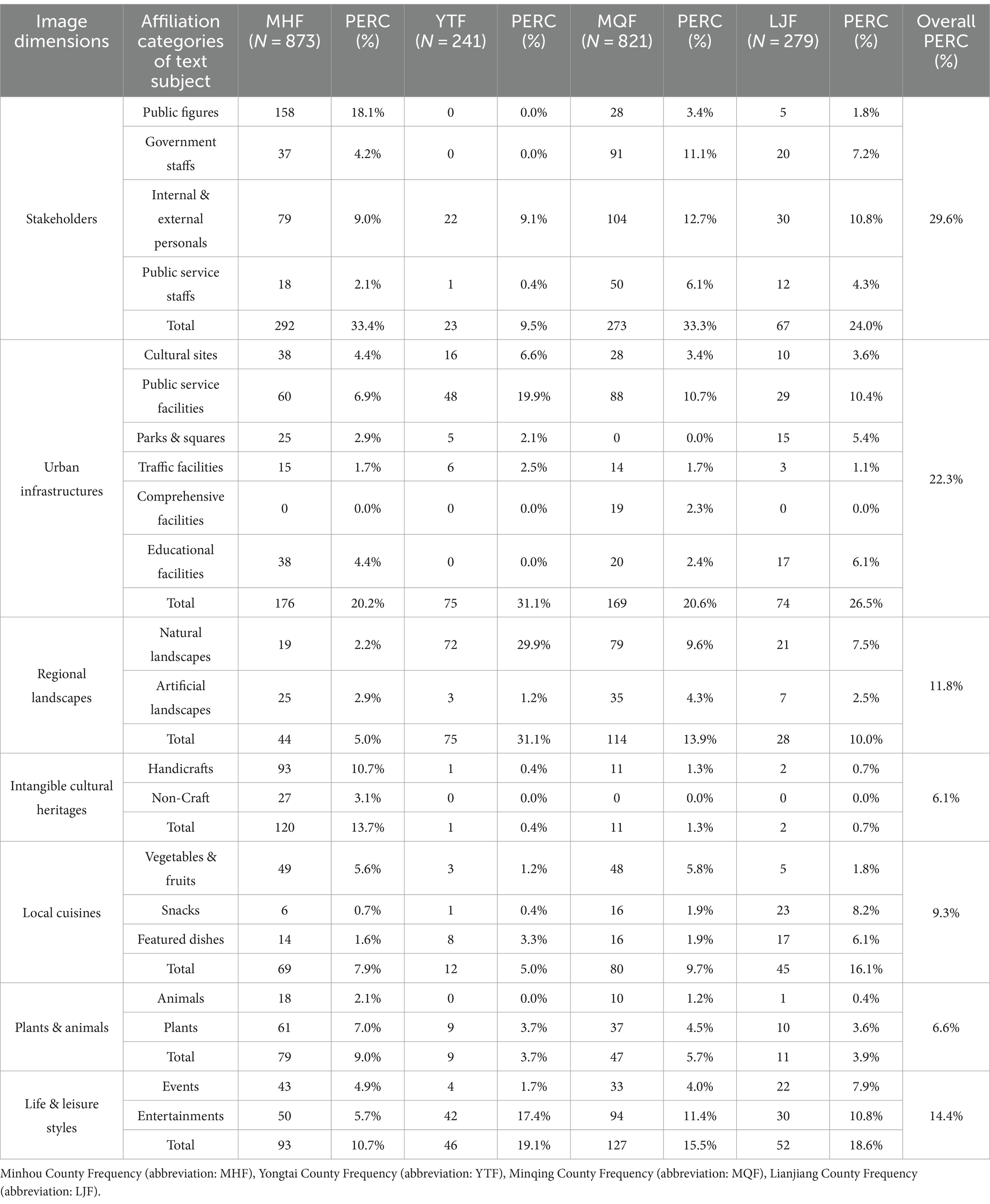

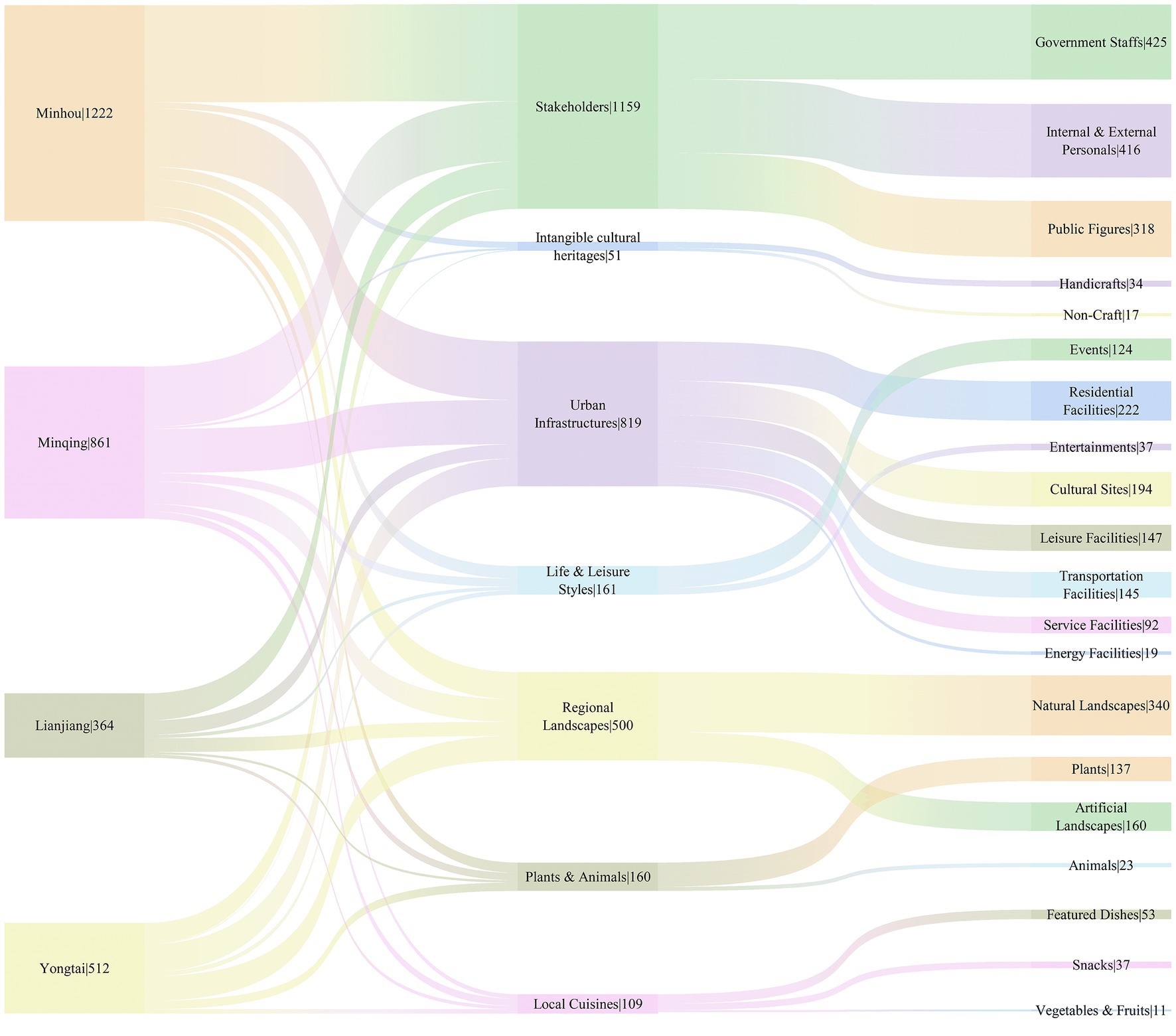

Regarding the top three dimensions of communication preferences, there is a consistently ranking among Minhou County, Minqing County, and Lianjiang County, with stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and regional landscapes being the primary dimensions. Yongtai County is ranked as follows: urban infrastructures, regional landscapes, and stakeholders.

Sort 1: As shown in Figure 4 and Table 4. The image projection of stakeholders in Minhou and Lianjiang counties is primarily represented by the category of government staffs (16.6 and 21.1%), prominently featuring visual symbols such as government officials, hosts, and police officers. In Minqing County, the image projection of stakeholders mainly revolves around internal & external personals (18.2%), encompassing residents, students, and tourists. In Yongtai County, the image projection of urban infrastructures is predominantly depicted through the category of residential facilities (9.0%), showcasing visual symbols of villages and urban buildings.

Table 4. Comparative analysis of video contents in Minhou, Yongtai, Minqing, and Lianjiang counties.

Sort 2: As shown in Figure 4 and Table 4. Minhou, Minqing, and Lianjiang counties all predominantly depict the image of urban infrastructures with a focus on the categories of residential facilities (7.3, 7.7, and 5.9%). This portrayal primarily encompasses visual symbols of villages, residential houses, and urban buildings. Furthermore, Lianjiang County highlights the projection of transportation facilities (5.9%), which prominently features visual symbols such as highways, parking lots, and bridges. In Yongtai County, the image projection primarily centers around the category of natural landscapes (23.4%) within the dimension of regional landscapes. This category predominantly includes visual symbols of rivers, lakes & streams, mountains, and lawns.

Sort 3: As shown in Figure 4 and Table 4. The image projection of regional landscapes in Minhou, Minqing, and Lianjiang counties is primarily focused on the category of natural landscapes (7.5, 8.7, and 14.9%). This category includes visual symbols depicting rivers, lakes & streams, mountains, and seas, showcasing the natural beauty of these areas. In Yongtai County, the image projection of stakeholders primarily falls under the category of public figures (12.9%). This category involves visual symbols representing netizens, actors, and celebrities, emphasizing the importance of influential individuals in shaping the county’s image.

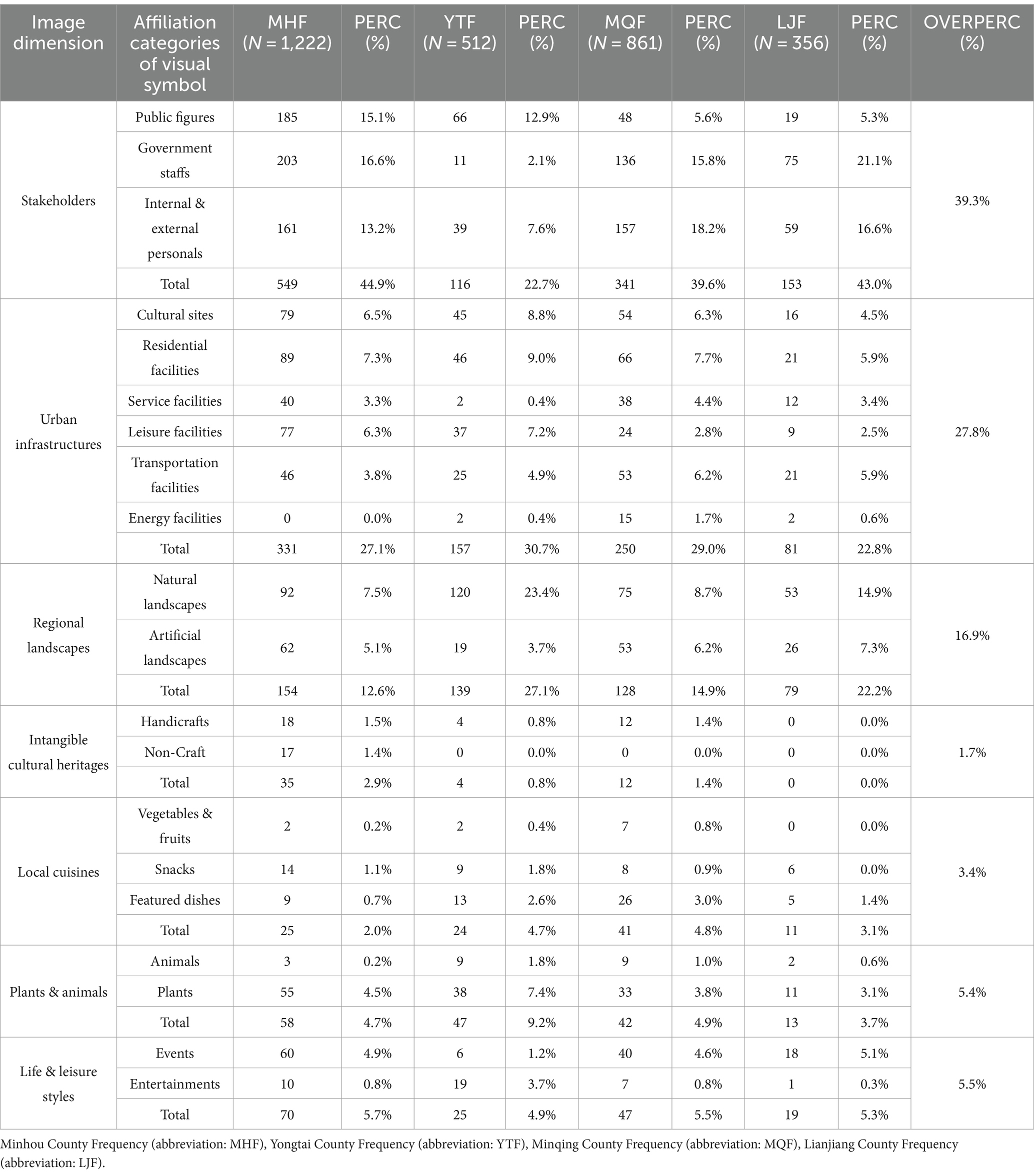

The general communication trends are presented in the visual content

Overall, stakeholders (39.3%), urban infrastructures (27.8%), and regional landscapes (16.9%) are the main preferences for projecting destination images in the four government new media. They are followed by life & leisure styles (5.5%), Plants & animals (5.4%), local cuisines (3.4%), and intangible cultural heritages (1.7%), which represent a smaller share of the overall visual communication. The dimensions presented in the short videos were ranked as follows: (1) stakeholders, (2) urban infrastructures, (3) regional landscapes, (4) life & leisure styles, (5) Plans and Animals, (6) local cuisines, and (7) intangible cultural heritages.

The above analysis and comparison lead to the following conclusions: Firstly, the four local governmental new media show clear communication preferences for the dimensions of stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and regional landscapes in terms of visual content presentation. In the stakeholder dimensions, the focus is on visual symbols such as government officials, online influencers, residents, local celebrities, and epidemic prevention personnel. The urban infrastructure dimensions emphasize visual symbols like urban buildings, old houses, roads, villages, and parks. The regional landscape dimensions present visual symbols such as rivers, lakes and streams, mountains, farmlands, and coasts. Secondly, the dimensions of life & leisure styles, plants & animals, and local cuisines receive less attention in short video communication. Although visual symbols related to life & leisure styles, such as hot springs, tourism, camps, etc., are present, and visual symbols representing plants and animals, such as plum blossoms, peach blossoms, egrets, flower-faced civets, etc., as well as visual symbols depicting local cuisines, such as fish balls, guobian, rice dumpling, oil cakes, etc., are included, their proportion is relatively lower compared to the aforementioned three dimensions. Finally, it is worth noting that intangible cultural heritage has the lowest proportion among the dimensions. Despite being a direct manifestation of regional culture, it is not considered an important dimension to be prominently presented in short videos with various visual symbols (Table 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 5. Main trends in dimensional presentation of visual symbols in short videos of Minhou, Yongtai, Minqing, and Lianjiang counties.

Comparison of destination images in the content of government new media releases

It was found that the descriptive texts and visual contents exhibited a high level of consistency in presenting the dimensions of stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and regional landscapes. The stakeholder dimension in the descriptive texts mainly focused on two categories: internal & external personals and public figures. Similarly, the stakeholder dimension in the visual symbols primarily encompassed government staff, internal & external personal, and public figures. The urban infrastructure dimension in the descriptive texts predominantly revolved around the theme of public service facilities, while the visual symbols, it centered on housing facilities and transportation facilities. Both the textual vocabularies and visual symbols related to the regional landscape dimension emphasized the natural landscapes. Although there is a strong consistency between the descriptive texts and visual contents of the aforementioned four new media, there are some variations in the vocabulary used under the subject words and the symbols categorized under visual content.

Main textual themes

The main subject words identified in the descriptive text of Minhou County are “public figures + public service facilities + handicrafts.” In Yongtai County, the main subject words are “public service facilities + natural landscapes + entertainments + internal & external personals.” Similarly, in Minqing County, the main subject words are “internal & external personals + public service facilities + natural landscapes.” In Lianjiang County, the main subject words are “public service facilities + internal & external personals + entertainments.” Meanwhile, the same type of subject words are deduplicated, without regard to ranking. Minhou County stands out from Yongtai, Minqing, and Lianjiang counties in terms of public figures and “handicrafts. Regarding public figures, Minhou County effectively utilized the popular term online influencers to promote public agendas, such as the county mayor’s live streaming of goods to assist the underprivileged and farmers, and local anchors disguising themselves as online influencers to advocate for epidemic prevention policies. In terms of handicrafts, Minhou County capitalized on its regional cultural characteristics by incorporating vocabularies related to intangible cultural heritage, such as stripped lacquerware, bamboo crafts, and Fujian operas, to shape a cultural destination image for Minhou County. As shown in Table 5.

Main visual categories

The main visual categories identified in Minhou County are “government staffs + residential facilities + natural landscapes.” In Yongtai County, the main visual categories are “residential facilities + natural landscape + public figures.” In Minqing County, the main visual categories are “internal & external personals + residential facilities + natural landscapes.” In Lianjiang County, the main visual categories are “government staffs + residential facilities + transportation facilities + natural landscapes.” Without prioritizing visual categories of the same type, Yongtai County distinguishes itself from the other three counties with its focus on public figures. Minhou County utilizes online influencers as a powerful strategy for destination marketing. Due to the abundance of mountain ranges, streams, and tourism resources in Yongtai County, local government agencies promote the destination through the marketing of online influences. In contrast, Minqing County stands out by focusing on local residents and micro-stories of urban life. Examples include the inspiring grandmother who sets up a stall late at night, villagers cleaning rural roads for free, and local enterprise employees spending New Year’s Eve on-site. Lianjiang County differentiates itself from the other three counties with its emphasis on transportation facilities. Located on the coast and boasting rich marine tourism resources and a well-developed transportation network, Lianjiang County provides touchpoints for both internal and external audiences to perceive the destination’s image. As shown in Table 5.

Conclusion

High homogeneity of content, lack of image differentiation

In the aforementioned statistics, it is evident that the descriptive texts and visual contents of the governmental new media in the four regions predominantly focus on the dimensions of stakeholders, urban infrastructures, and regional landscapes, while receiving relatively less emphasis on intangible cultural heritages, local cuisines, plants & animals, and life & leisure styles. As a result, the governmental new media of Minhou, Yongtai, Minqing, and Lianjiang counties tend to exhibit homogeneity in their short video dissemination and present a relatively monotonous portrayal of destination image dimensions. Unlike limited textual descriptions, short videos are regarded as a rich form of expression, whereas text merely serves as a concise means of expression. Short videos can employ symbolic systems to construct logical relationships and convey activities, events, and intended meanings of the publishing subject (Lim and Benbasat, 2000). Decision-makers involved in information distribution must possess a comprehensive and extensive understanding of the information contained within short videos (Daft and Lengel, 1986). By doing so, rich visual representations can facilitate comprehension and enable individuals to form a holistic understanding of the information, thereby enhancing the diversity of the destination image dimensions. For instance, in the plants and animals dimension, a substantial number of visual symbols portray flowers and trees, while animal depictions are comparatively scarce. In the life & leisure styles dimension, a significant proportion of visual symbols focus on cultural performances, with less attention given to the leisure and entertainment aspects of citizens’ lives. Regarding intangible cultural heritages, Yongtai County, Minqing County, and Lianjiang County generally lack corresponding visual symbols in their presentations. In terms of descriptive texts, the vocabulary employed for each dimension tends to be more limited. This is partly due to platform restrictions on text length and partly because textual elements have a weaker impact than images in terms of meaningful associations and semantic references.

Lack of cultural dimension, need for enhanced sense of identity

Among the seven dimensions of destination image presented in the governmental new media of Yongtai, Minqing, and Lianjiang counties, intangible cultural heritage occupies the smallest share in both descriptive texts and visual content presentations. However, culture and destination are inherently interconnected, representing local characteristics and serving as a distinguishing factor between different regions (Scott, 2000). Therefore, local culture plays a crucial cognitive role in short video communication and contributes to fostering a positive destination image (Guo and Feng, 2021). Regarding the actual regional culture, Yongtai County boasts intangible cultural heritage such as the “Traditional Dance of Chuanbanlong (椽板龙传统舞蹈),” the “Traditional Music of Shifanchi (十番伬传统音乐).” In Minqing County, there are notable practices such as “Dragon Kiln Wood-firing Technique (龙窑柴烧技艺),” “Qiuzhuzai Craftsmanship of Woven Bamboo Hats (秋竹仔斗笠编织技艺).” Lianjiang County showcases cultural events such as the “Fudou Nanhai Shrine Festival (福斗海南神坛祭),” “Dragon Boat Racing on the Sea (海上龙舟竞赛).” It is important to note that the governmental new media differs from unofficial self-media platforms, which employ short videos to disseminate intangible cultural heritage with the aim of gaining traffic and subsequent commercial benefits. Conversely, the primary objective of local governmental new media is to amplify the communication power and visibility of local intangible cultural heritage, serving as a means to promote and preserve cultural richness.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HW: Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. ZM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baloglu, S., and McCleary, K. W. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 26, 868–897. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00030-4

Bulchand-Gidumal, J. (2023). The case of BeReal and spontaneous online social networks and their impact on tourism: research agenda. Curr. Issue Tour. 27, 7–11. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2023.2191174

Camilleri, M. A., and Kozak, M. (2022). Interactive engagement through travel and tourism social media groups: a social facilitation theory perspective. Technol. Soc. 71:102098. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.102098

Cao, X., Qu, Z., Liu, Y., and Hu, J. (2021). How the destination short video affects the customers’ attitude: the role of narrative transportation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 62:102672. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102672

Casali, G. L., Liu, Y., Presenza, A., and Moyle, C.-L. (2021). How does familiarity shape destination image and loyalty for visitors and residents? J. Vacat. Mark. 27, 151–167. doi: 10.1177/1356766720969747

Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 6, 408–424. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(79)90004-5

Daft, R. L., and Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manag. Sci. 32, 554–571. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.32.5.554

Du, X., Liechty, T., Santos, C., and Park, J. (2020). ‘I want to record and share my wonderful journey’: Chinese millennials’ production and sharing of short-form travel videos on TikTok or Douyin. Curr. Issue Tour. 25, 3412–3424. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1810212

Gan, J., Shi, S., Filieri, R., and Leung, W. K. (2023). Short video marketing and travel intentions: the interplay between visual perspective, visual content, and narration appeal. Tour. Manag. 99:104795. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104795

Garay, L. (2019). # Visitspain. Breaking down affective and cognitive attributes in the social media construction of the tourist destination image. Tourism Manag. Perspect. 32:100560. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100560

Guo, X., and Feng, J. (2021). Traditional cultural short video publicity system based on data mining and digital image technology. Adv. Multimedia 2021, 1–8. doi: 10.1155/2021/6335966

Han, J., Zhang, G., Xu, S., Law, R., and Zhang, M. (2022). Seeing destinations through short-form videos: implications for leveraging audience involvement to increase travel intention. Front. Psychol. 13:1024286. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1024286

Hankinson, G. (2004). Relational network brands: towards a conceptual model of place brands. J. Vacat. Mark. 10, 109–121. doi: 10.1177/135676670401000202

Hanna, S., and Rowley, J. (2011). Towards a strategic place brand-management model. J. Mark. Manag. 27, 458–476. doi: 10.1080/02672571003683797

Hunt, J. D. (1975). Image as a factor in tourism development. J. Travel Res. 13, 1–7. doi: 10.1177/004728757501300301

Jamshidi, D., Rousta, A., and Shafei, R. (2023). Social media destination information features and destination loyalty: does perceived coolness and memorable tourism experiences matter? Curr. Issue Tour. 26, 407–428. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2021.2019204

Lawson, F., and Baud-Bovy, M. (1977). Tourism and recreation development, a handbook of physical planning. London: Architectural Press.

Li, Y., Xu, X., Song, B., and He, H. (2020). Impact of short food videos on the tourist destination image—take Chengdu as an example. Sustain. For. 12:6739. doi: 10.3390/su12176739

Lim, K. H., and Benbasat, I. (2000). The effect of multimedia on perceived equivocality and perceived usefulness of information systems. MIS Q. 24:449. doi: 10.2307/3250969

Lim, Y., Chung, Y., and Weaver, P. A. (2012). The impact of social media on destination branding: consumer-generated videos versus destination marketer-generated videos. J. Vacat. Mark. 18, 197–206. doi: 10.1177/1356766712449366

Lin, M. S., Liang, Y., Xue, J. X., Pan, B., and Schroeder, A. (2021). Destination image through social media analytics and survey method. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 33, 2219–2238. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-08-2020-0861

Mak, A. H. (2017). Online destination image: comparing national tourism organisation’s and tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Manag. 60, 280–297. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.012

Molinillo, S., Liébana-Cabanillas, F., Anaya-Sánchez, R., and Buhalis, D. (2018). DMO online platforms: image and intention to visit. Tour. Manag. 65, 116–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.09.021

Nautiyal, R., Albrecht, J. N., and Carr, A. (2022). Can destination image be ascertained from social media? An examination of twitter hashtags. Tour. Hosp. Res. 23, 578–593. doi: 10.1177/14673584221119380

Rosário, A. T., and Dias, J. C. (2023). Marketing strategies on social media platforms. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 19, 1–25. doi: 10.4018/IJEBR.316969

Scott, A. J. (2000). The cultural economy of cities: essays on the geography of image-producing industries. Cult. Econ. Cities, London: SAGE Publications Ltd. 1–256.

Shao, T., Wang, R., and Hao, J. X. (2019). Visual destination images in user-generated short videos: an exploratory study on Douyin. Proceedings of the 2019 16th international conference on service systems and service management (ICSSSM) (IEEE), Shenzhen, China. 1–5.

Stepchenkova, S., and Zhan, F. (2013). Visual destination images of Peru: comparative content analysis of DMO and user-generated photography. Tour. Manag. 36, 590–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.08.006

Tan, W. K., and Wu, C. E. (2016). An investigation of the relationships among destination familiarity, destination image and future visit intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 5, 214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.008

Tasci, A. D. A., Gartner, W. C., and Tamer Cavusgil, S. (2007). Conceptualization and operationalization of destination image. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 31, 194–223. doi: 10.1177/1096348006297290

Tosun, C., and Jenkins, C. L. (1996). Regional planning approaches to tourism development: the case of Turkey. Tour. Manag. 17, 519–531. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(96)00069-6

Tussyadiah, I. P., and Fesenmaier, D. R. (2009). Mediating tourist experiences: access to places via shared videos. Ann. Tour. Res. 36, 24–40. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.001

Uşaklı, A., Koç, B., and Sönmez, S. (2017). How “social” are destinations? Examining European DMO social media usage. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 6, 136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.02.001

Wang, C., Cui, W., Zhang, Y., and Shen, H. (2022). Exploring short video apps users’ travel behavior intention: empirical analysis based on SVA-TAM model. Front. Psychol. 13:912177. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.912177

Wang, R., Luo, J., and Huang, S. S. (2020). Developing an artificial intelligence framework for online destination image photos identification. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 18:100512. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100512

Xiao, X., Fang, C., and Lin, H. (2020). Characterizing tourism destination image using photos’ visual content. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 9:730. doi: 10.3390/ijgi9120730

Zeng, B., and Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 10, 27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2014.01.001

Zhang, G., Yang, S., Ke, J., and Zhang, M. (2020). Differentiation and similarity of destination images in OGC and TGC photos: outline of the online communication chain of destination image. Tour. Tribune. 35, 52–62. doi: 10.19765/j.cnki.1002-5006.2020.12.010

Keywords: short videos, destination images, TikTok platform, governmental new media, visual symbol

Citation: Lin H, Wen H and Ma Z (2024) A study on the construction of destination image for China’s county-level integrated media centers: a case study of four counties in Fuzhou. Front. Commun. 9:1346212. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1346212

Edited by:

Marina Lourenção, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Paula Rosa Lopes, Lusofona University, PortugalElena Kossmann, Independent Researcher, Duisburg, Germany

Copyright © 2024 Lin, Wen and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanzheng Lin, bGluLmhhbnpoZW5nQG91dGxvb2suY29t

Hanzheng Lin

Hanzheng Lin Hongyan Wen

Hongyan Wen Zhuokai Ma1

Zhuokai Ma1