94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 17 April 2024

Sec. Media Governance and the Public Sphere

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1338587

This article is part of the Research TopicPress Freedom, Journalism Practice, and Professionalization in Times of UncertaintyView all 6 articles

This study delves into public perceptions of media social responsibility within the contemporary Albanian media landscape. Through a comprehensive analysis of various factors, the study identifies the prevailing principles that the public deems crucial for the media’s social responsibility and how these principles can enhance the media’s contribution to society. A structured questionnaire was used to capture a wide range of public perceptions, with 1,321 questionnaires filled out. These questionnaires were distributed using a face-to-face method across five major urban centers in Albania, ensuring a comprehensive and representative sample of public viewpoints. The distribution method employed a stratified sampling approach to ensure diverse representation across different demographic groups. Additionally, employing a mixed-methods approach, the research includes qualitative interviews with 20 influential stakeholders, including media directors, professors, analysts, and media researchers. Purposive sampling was utilized to select stakeholders representing various sectors of the media landscape. Rigorous measures were taken to mitigate data pollution, including thorough interviewer training and constant monitoring of data quality. An overarching thematic analysis was conducted to identify common themes and patterns across the qualitative interviews, complementing the quantitative findings. To gain further insights, we purposefully selected and conducted a focus group with 28 journalists from various media platforms. The sampling method for the focus group involved purposive sampling to ensure representation from diverse media backgrounds and experiences. Data collected from the focus group underwent thematic analysis to identify common themes and patterns, contributing to an overarching qualitative analysis. This mixed-methods approach facilitated a comprehensive understanding of journalists’ perspectives on social responsibility and the challenges they encounter in fulfilling it. The empirical findings reveal that the media’s social responsibility in Albania does not fully adhere to the expected standards encompassing all relevant principles. Internal dynamics within media organizations and external forces from politics, economics, and society collectively influence this shortfall. The study highlights the importance of considering public perceptions and expectations in shaping media’s social responsibility, emphasizing the need for substantial improvements.

The public’s perception of the media’s social responsibility in the contemporary media landscape has evolved into a topic of pronounced concern and scholarly interest. While numerous studies have explored the concept of media social responsibility (Nordenstreng and Varis, 1974; McQuail, 1992; Shoemaker and Reese, 1996; Curran and Seaton, 2003; Wall, 2010), research focusing on the public’s perspective, particularly within developing countries, remains limited. Lippmann’s seminal work serves as a foundational reference, highlighting the significance of comprehending public opinion and its implications for democratic societies (Lippmann, 1922). However, this paper’s primary focus lies in the evaluation of the public’s view on how the media fulfills its social responsibility.

Before delving into the public’s perception of the media’s social responsibility, it is imperative to ascertain how the media itself defines this role. Journalists’ professional identities are shaped by the conditions in their respective countries, influencing their perceptions of responsible journalism (Weaver and Willnat, 2012). The media’s choice of coverage, story placement, and framing significantly impact what readers deem important and relevant. Therefore, it is crucial to comprehend how media organizations conceptualize their responsibilities in this regard (Althaus and Tewksbury, 2002). In addition, it must be realized that journalists’ identities and roles are not static; they are shaped by their values, professional norms, and the evolving media landscape. This implies that journalists often navigate a complex intersection of professional roles and ethical considerations (Deuze, 2005). These ethical considerations permeate their daily routines, encompassing not only the content of news but also the critical aspects of information objectivity. Moreover, they evaluate the media’s effectiveness in fulfilling its pivotal roles as a watchdog, information disseminator, and contributor to informed public discourse.

Understanding public perception of media social responsibility in developing countries is crucial for several compelling reasons. In such countries, media organizations follow government regulations or practice self-regulation, reducing information manipulation risk. However, in countries transitioning to democratic structures, there is a notably higher risk of information manipulation due to direct political and economic influences on the media’s primary product: information dissemination (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). The level of risk associated with information manipulation is closely tied to public awareness and citizen responsiveness. While it may not have been explicitly studied in this precise context, some authors address the importance of an informed and responsive citizenry in democratic societies (Almond and Verba, 1963). Unfortunately, in many developing countries like Albania, public awareness and its capacity for effective reaction often remain underdeveloped (Dervishi, 2023).Secondly, the public’s perception of media social responsibility is intricately linked to broader societal expectations and values. Assessing this perception helps gage how well the media aligns with the principles of democratic societies. In the case of evolving media landscapes, like in Albania, this research becomes particularly relevant. Albania’s unique cultural and political context, marked by historical and contemporary shifts, provides a compelling backdrop for understanding how the public perceives media social responsibility. The country’s complex socio-political history, including periods of communism and subsequent transitions to democracy spanning more than 30 years, coupled with its diverse cultural heritage and geopolitical influences, contribute to the distinctiveness of its media landscape and shape public perceptions of media social responsibility. The study can elucidate the challenges and opportunities that the media faces in fulfilling its social responsibilities within a transitional society. As a result, this paper offers a valuable contribution not only to the understanding of media social responsibility in Albania but also to the broader academic and practical discourse in the field of media studies. By delving into public perceptions of media social responsibility, the research enriches the ongoing dialogue and provides insights that can benefit media practitioners, policymakers, and scholars alike.

A historical perspective on the evolution of social responsibility in the Albanian media unveils a complex journey, especially given the challenging political context. During the communist regime in Albania (1945–1990), journalists often were faced with a dual role, simultaneously serving both the government’s interests and critiquing the general population. This dual function created complexities in upholding media social responsibility, as they operated under government control and had to adhere to the state’s objectives (Reçi, 2023). In the post-1990s era, Albania’s media underwent significant changes. Ownership shifted from media controlled by political parties to journalist-driven outlets and, in the present, privately owned media (Zguri, 2017). The second and third developmental phases emphasized components of social responsibility related to journalistic standards and the media’s role as a watchdog. However, despite the country’s aspirations for European Integration, concerns persist regarding media independence and professionalism (Albania Report 2022, 2023). This ongoing conundrum of media responsibility and journalistic ethics indicates a potential intersection that warrants further exploration in academic discourse.

Understanding the historical context of media development in Albania is essential for appreciating the principles of media social responsibility that have emerged over time. This topic has been a subject of continuous debate and transformation, spanning decades of change within the media landscape. Since its inception in 1947, with the release of the influential Hutchins Commission Report, the debate on media’s social responsibility has been central to discussions on media ethics, freedom, and its role in democratic societies.

Hutchins’s report laid the foundation by emphasizing the media’s ethical duty as a public trustee to promote the public interest, marking a significant milestone in the discourse on media ethics and responsibility (Commission on Freedom of the Press and Hutchins, 1947). Over the years, prominent theories and studies have further refined the concept of social responsibility in media. These theories, including the four theories of the press and agenda-setting, have contributed valuable insights into the media’s role in shaping public opinion, its ethical obligations, and its influence on societal issues (Siebert et al., 1956; McCombs and Shaw, 1972). Each theory offered a unique perspective on how the media should fulfill its social responsibilities within the ever-evolving media landscape.

However, the notion of media social responsibility has evolved substantially over time. It has expanded beyond the realm of journalistic integrity, now encompassing a broader spectrum of considerations such as diversity, ethical reporting, and global engagement. Media is expected to represent a diverse array of voices, perspectives, and communities, promoting inclusivity and preventing discrimination (Carpentier, 2011). Furthermore, the media is obligated to exercise sensitivity when reporting on sensitive subjects, including minors, victims, and marginalized groups, while avoiding any potential harm (Tuchman, 1978).

The principles of impartiality and objectivity remain vital in media, ensuring the fair and unbiased presentation of information, and allowing the audience to form their own opinions (Ward, 2008). In today’s digital transformation and the proliferation of social media, media social responsibility has expanded to encompass accuracy in a world full of misinformation, responsible use of data, and the impact of algorithms on information dissemination (Budini, 2023).

Ethical journalism underscores the utmost importance of accuracy and truthfulness in delivering news, with journalists serving as gatekeepers of accurate information (Kovach and Rosenstiel, 2014). Accountability is equally vital, as the media is expected to transparently rectify errors (Singer, 2004). Prioritizing the public interest by providing pertinent and valuable information is a cornerstone of media social responsibility (Curran and Seaton, 2003). To fulfill this role effectively, media should operate independently, free from undue influence or control by political or economic forces (McChesney, 1999). In addition, media organizations are encouraged to engage with communities, understand their needs, and involve them in the news-making process (Harte and Tindall, 2009).

In the era of digital platforms, media should also consider their environmental impact and strive for sustainability, considering their broader ecological footprint (Lester, 2014). These principles guide the modern media landscape, ensuring ethical and socially responsible journalism in a rapidly evolving digital age. Table 1 provides a summarized overview of the primary elements of media social responsibility as delineated by theoretical perspectives and research studies.

In the ever-changing media landscape, adherence to the principles of social responsibility is vital for both media organizations and the public they serve. These principles offer ethical guidelines and standards that media entities must uphold as they fulfill their role as sources of information, educational platforms, and guardians of societal well-being (Bregu, 2023). They are instrumental in upholding trust, credibility, and accountability in the realm of media.

Our study adopts a mixed-method approach, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative data to yield a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. Given our study’s overarching objective of uncovering public perceptions, we predominantly employed open-ended questionnaires for data collection, which were analyzed using thematic analysis to identify recurring themes and patterns in the participants’ responses. Concurrently, qualitative techniques are employed, encompassing in-depth interviews with key stakeholders and focus groups with journalists, enabling a deeper exploration of diverse perspectives and contextual factors that influence media practices (Johnson and Christensen, 2019). Thematic analysis is subsequently applied to qualitative data to discern recurring themes, while statistical analysis of quantitative data identifies trends and correlations (Miles et al., 2019). Emphasis is placed on reflexivity throughout the research process to acknowledge and mitigate biases and perspectives that may influence data collection, analysis, and interpretation (Creswell and Poth, 2016). The study implemented several strategies to mitigate biases and ensure methodological robustness. The use of triangulation, by integrating data from multiple sources such as surveys, interviews, and focus groups, helped validate findings and reduce the impact of individual biases inherent in each method. Additionally, reflexivity was encouraged, prompting us to critically reflect on our own biases and assumptions throughout the research process, thus enhancing transparency and trustworthiness in data interpretation. These proactive measures collectively contributed to mitigating biases and upholding the validity of the study’s findings. Furthermore, discrepancies or contradictions between qualitative and quantitative data are scrutinized to unveil insights into the complex nature of media social responsibility (Patton, 2014). The study ensures methodological robustness by employing strategies to mitigate biases and uphold validity, thereby contributing to the credibility of its findings (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). Through this methodologically integrated framework, the study endeavors to provide an insightful understanding of media responsibility, bolstering the rigor and trustworthiness of its outcomes.

Our study required a deep comprehension of the principles of media responsibility and their fundamental components. This foundational knowledge served as a compass for our research, enabling us to effectively interpret the collected data. Our primary focus was to unveil the diverse perspectives held by the public regarding media social responsibility and to identify the criteria they use to assess the media’s effectiveness in fulfilling this role in society. To accomplish this, we consulted existing literature to gain valuable insights, facilitating the practical implementation of our research tasks.

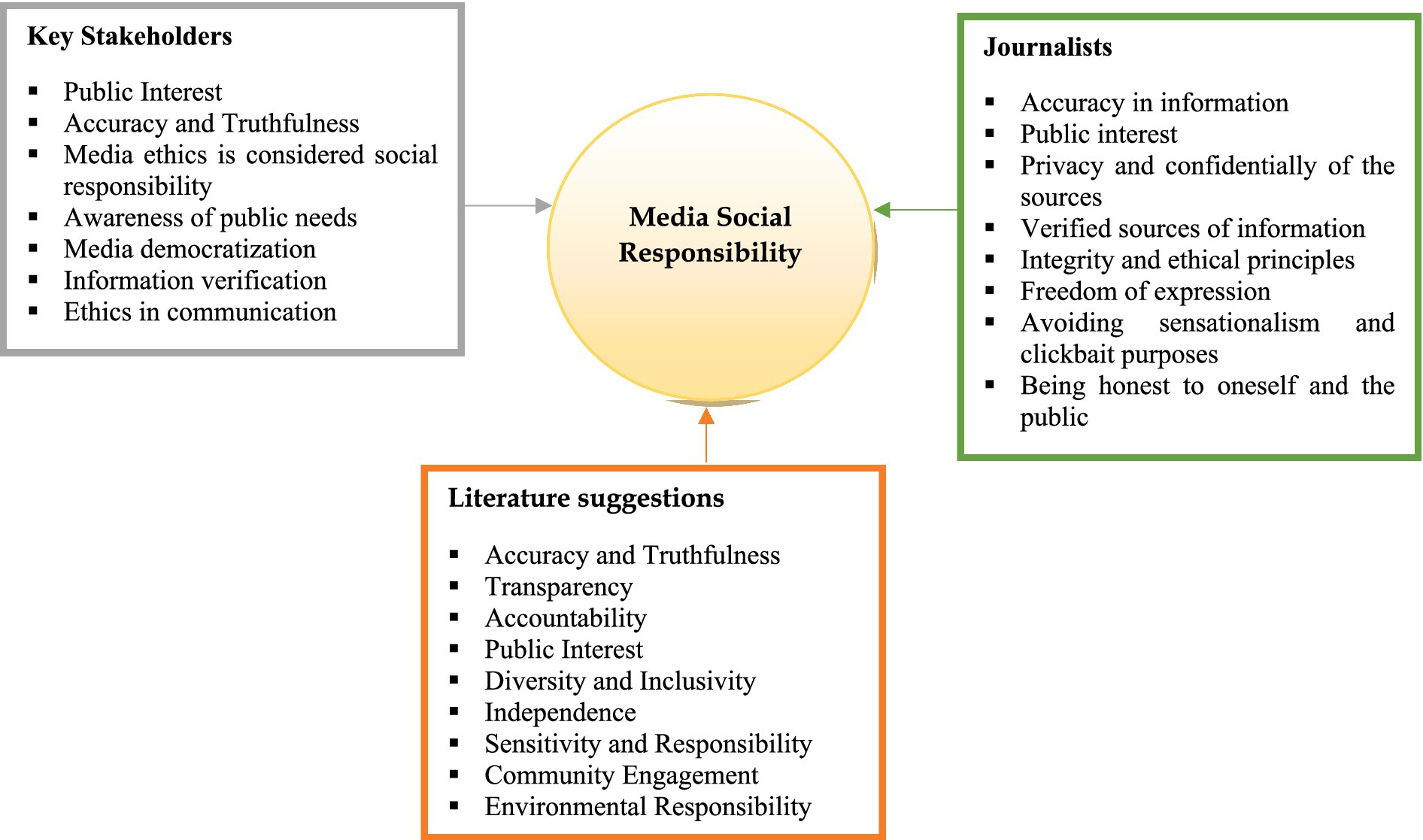

After exhaustively analyzing and synthesizing data from diverse sources, we have achieved a holistic understanding of the significance of media social responsibility. This understanding encompasses perspectives from the general public, key stakeholders, and journalists within the Albanian media milieu. While the forthcoming sections will delve into the public’s viewpoint, it is imperative to scrutinize the comprehension of media social responsibility among key stakeholders and journalists vis-à-vis scholarly literature. The findings highlight a clear distinction and separation of conceptual boundaries among these groups, revealing a diverse understanding that diverges from prevalent academic discourse. Figure 1 summarizes the main findings from qualitative interviews with key stakeholders and focus groups with journalists regarding their views on media social responsibility. These insights are compared with information gleaned from existing literature.

Figure 1. Comparison of media social responsibility concepts among key stakeholders, journalists, and literature.

The analysis indicates that key stakeholders and journalists may have a narrower focus on certain aspects of media social responsibility compared to the broader perspectives outlined in the literature. While there is alignment on core principles such as accuracy, truthfulness, and public interest, key stakeholders and journalists may overlook aspects such as transparency, diversity, community engagement, and environmental responsibility. This suggests a potential gap between the theoretical ideals outlined in the literature and the practical considerations of key stakeholders and journalists in the Albanian media landscape. Closing this gap may require further dialogue and collaboration to ensure a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to media social responsibility. Risto (2023) posits that the notion of social responsibility within the Albanian media realm emerges after its primary functions of information dissemination and entertainment provision. Mainstream media outlets, which possess the privilege of scrutinizing the content they disseminate, often apply the concept of social responsibility ambiguously due to the unclear foundational principles underlying this notion. Echoing this sentiment, Bregu (2023) observes that in the Albanian media landscape, engagement continues to adhere to traditional paradigms. Despite the audience’s newfound freedom to comment, these interactions are often superficially acknowledged. Instead of fostering constructive discourse, comments frequently devolve into a cacophony of vitriol, including, but not limited to, derogatory language, hate speech, and sexist rhetoric. Consequently, the purported commitment to the “public interest” by media organizations remains enigmatic, lacking clear delineation or operationalization.

Qualitative data from interviews with key stakeholders and journalists played a pivotal role in refining our research process. These interviews provided deeper insights into themes identified in quantitative data, enabling a better understanding of media social responsibility in the Albanian context. By engaging directly with stakeholders and journalists, we uncovered underlying motivations and complexities within the media landscape, enhancing the validity of our findings.

The integration of qualitative and quantitative data allowed for a comprehensive analysis of media social responsibility. Qualitative insights complemented quantitative findings, offering additional depth and context. For instance, interviews revealed practical challenges faced by stakeholders and journalists, enriching our interpretation of results and providing a holistic perspective.

Distinguishing between qualitative data from stakeholders and journalists was essential. Each provided unique perspectives on media social responsibility, contributing to a comprehensive understanding. By comparing these perspectives, we identified convergence and divergence, informing recommendations and interventions within the media landscape.

Various authors and researchers have identified a range of challenges in implementing social responsibility in the media. These challenges often stem from the tension between profit motives and ethical obligations, the prevalence of sensationalism, and the rise of online platforms that sometimes prioritize engagement over responsible reporting (Curran and Seaton, 2003; Ward, 2008; Kovach and Rosenstiel, 2014).

Altheide (1997) argues that news media can sometimes prioritize sensational and fear-inducing narratives over responsible and balanced reporting, which can lead to a distorted understanding of societal issues, contribute to social anxieties, and potentially result in misguided policy responses.

Randall (2000) outlines 10 ethical dilemmas that media journalists may encounter. Each dilemma is briefly presented in Table 2, which includes a concrete illustrative example for each case, exemplifying the practical manifestations of these challenges within journalism.

The paramount issue of fostering and retaining public trust in media organizations has been a subject of continuous debate. In an era marked by increased scrutiny and skepticism, media entities are under pressure to be accountable for their content (Lewis and Reese, 2009). Within the academic landscape, there is a recurring dilemma for media organizations—the delicate balance between maintaining editorial independence and succumbing to commercial pressure. This enduring struggle is encapsulated in the challenge of reconciling the ethical obligation to disseminate truthful and objective information with the pragmatic necessity of generating advertising revenue and ensuring profitability (McChesney, 1999). Simultaneously, the media struggles with maintaining the integrity and quality of journalistic practices while addressing the growing demand for sensational and entertainment-focused content. Esteemed scholars such as Kovach and Rosenstiel (2014) emphasize the paramount importance of preserving the foundational principles of journalism in the face of the allure of sensational news content.

Another enduring theme in scholarly discourse concerns media ownership and focus. As explained by Bagdikian (2004), conglomerates with control over a multitude of media outlets can exert a profound influence over public discourse. This monopolistic ownership can subsequently limit the diversity of viewpoints accessible to the public, challenging thus the media’s fundamental duty to provide a multiplicity of perspectives, a crucial aspect of its social responsibility.

Furthermore, the omnipresence of political influence and bias within media organizations is a well-documented subject of inquiry. Research conducted by Entman (2012) highlights the complexity of maintaining journalistic impartiality and the obligation to offer a spectrum of perspectives in the face of mounting political pressures.

Contemporary digital transformation has brought forth unique challenges. The proliferation of online platforms and the prevalence of social media have contributed to the rapid spread of misinformation and fabricated news (Wardle and Derakhshan, 2017). This digital landscape presents a significant obstacle to the media’s commitment to the accuracy and authenticity of the information it disseminates. Moreover, emerging technologies like deep fakes and AI-driven content creation introduce novel ethical dilemmas (Hern, 2020).

The media industry is grappling with challenges in diversity and inclusion, with scholars like Nothias (2020) emphasizing the importance of advocating for fair representation and confronting deeply entrenched biases in media content and the workforce.

A longstanding challenge for the media lies in balancing its responsibility to inform the public and its ethical obligation to respect individual privacy. As explained by McQuail (1992), this conundrum necessitates adherence to stringent ethical guidelines, especially when reporting on delicate or sensitive issues (Rakipllari, 2023). The pursuit of audience engagement, a pivotal objective, occasionally leads media organizations to inadvertently foster echo chambers and polarization (Sunstein, 2017). Navigating the fine line between accommodating diverse perspectives and satisfying audience preferences is a considerably complex task. Complying with regulatory frameworks while resisting external censorship remains a delicate issue, particularly in regions with varying legal and political landscapes. The imposition of constraints on media freedom by international bodies and governments complicates its commitment to upholding free expression and independence (Noam, 2017). Ensuring the long-term sustainability and economic viability of media organizations is an enduring and complicated challenge, revolving around the ongoing tension between profitability objectives and the media’s commitment to social responsibility (Picard, 2009).

In the global context, countries such as Albania face unique challenges in implementing social responsibility in their media landscape. Firstly, a significant hurdle is the low level of comprehension and awareness regarding the concept of social responsibility. This lack of understanding is coupled with resistance from media agencies and journalists, reflecting a broader reluctance to embrace this ethos. Journalists in Albania face vulnerability, and the nation undergoes a protracted transition across various aspects (Çela, 2023a). Secondly, the inefficacy of regulatory bodies and self-regulation, limited resources for media education, and concerns about media ownership and political influence have had deleterious effects on the media’s core mission (Meço, 2023). Notably, there is a substantial level of interference in news stories, a practice that substantially tarnishes the image of journalists and undermines the integrity of the profession (Çipuri, 2023). What is perhaps unique to Albania is the informal nature of journalism, along with an absence of legal security in the realm of employer-employee social partnerships. This informality extends to financial matters, including issues related to the accuracy and regularity of monthly and periodic salaries (Çipa, 2023).

Luarasi (2023) emphasizes a perceptible shift in journalism, where traditional professional values have been overshadowed by a growing focus on metrics such as clicks and views. The pursuit of sensationalism, driven by the quest for more clicks, has, in turn, diverted the attention of certain media outlets and journalists away from the principles of social responsibility toward maintaining high viewership and ensuring their economic sustainability. Moreover, concerns related to originality, uniformity, and copyright are prominent in the Albanian media landscape. Online media outlets, in particular, often operate without strict adherence to copyright norms, leading to extensive copying and pasting of content from other sources (Saliu, 2023).

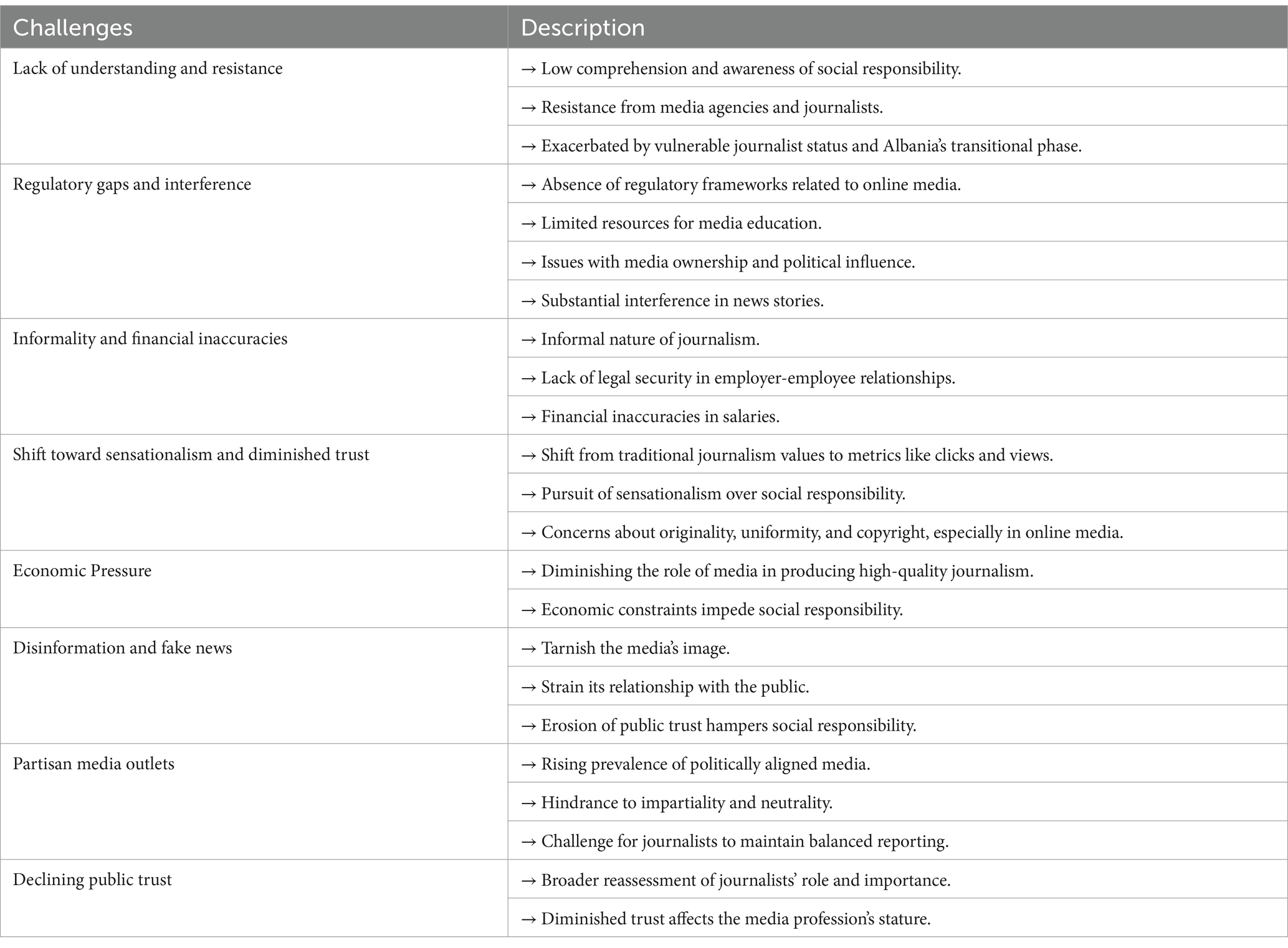

As explained in the upcoming methodology section, a focus group of Albanian journalists from diverse media outlets unveiled for this study four primary challenges that they perceive as having a substantial influence on their endeavors related to social responsibility. The first challenge pertains to economic pressures, which have generated a diminishing role for media organizations in their ability to produce high-quality journalism. Consequently, economic constraints and resource limitations have impeded the capacity to uphold the principles of social responsibility within the media landscape. The second challenge encompasses the proliferation of disinformation and the prevalence of fake news in the contemporary media setting. These issues have emerged as formidable impediments that have not only tarnished the image of the media but have also strained its relationship with the public. The consequential erosion of public trust poses a significant challenge in upholding social responsibility, as it hampers the media’s credibility and its capacity to fulfill its societal role effectively (Bejtja, 2023). The third challenge addresses the rising prevalence of partisan media outlets that align with specific political ideologies. This proliferation of politically aligned media sources has engendered a formidable impediment to the impartiality and neutrality that are fundamental components of social responsibility. Journalists find it increasingly challenging to maintain their commitment to balanced and unbiased reporting in an environment characterized by partisan media (Semini, 2023). The fourth challenge, which may be considered an outcome of the three aforementioned ones, pertains to the declining level of public trust in the media. This diminished trust has instigated a broader reassessment of the role and relevance of journalists within society (Rosen, 1997). The media profession, once regarded as prestigious, has seen its stature and societal importance wane. These intertwined challenges collectively underscore the multifaceted obstacles that journalists encounter in their quest to fulfill the tenets of social responsibility within the evolving media landscape (Table 3).

Table 3. Challenges in media social responsibility implementation in Albania (Qualitative interview findings).

There is an ongoing discussion in the context of comprehending public perceptions regarding media’s social responsibility when it comes to the dichotomy of regulatory bodies vs. self-regulation as mechanisms to ensure accountability in media practices. This debate plays an essential role in understanding how the public evaluates media organizations’ commitment to their ethical standards and social responsibilities. A key element of this is the essential role played by the public in shaping their expectations of the media (Gjoni, 2023). Consequently, the public’s perception of media social responsibility is closely tied to their assessment of regulatory bodies and self-regulation mechanisms’ effectiveness. The assessment of these factors is critical in determining the extent to which the media fulfills its social responsibility in the eyes of its audience. By exploring this discourse within the broader context of public perception, we can offer scholarly insights into the implications of choosing either regulatory bodies or self-regulation.

The “Global Handbook of Media Accountability” by Fengler et al. (2021) highlights the multifaceted nature of media accountability. This authoritative work emphasizes that media accountability is a multi-dimensional concept, with unique challenges in different regions. Factors such as state intervention, the professionalism of journalism, media pluralism, technological advancements, and cultural norms all play significant roles in shaping media accountability structures. Challenges to media self-regulation are encountered in both Western democracies and transitional countries and include issues such as the limited acceptance of self-regulation within the media industry, perceived ineffective sanctions, and the looming potential for government intervention. Notably, some governments may consider establishing statutory councils in response to perceived shortcomings in self-regulation mechanisms, as a means of exerting greater control over the media landscape.

Tettey’s (2006) three-dimensional model of media accountability provides a valuable framework for understanding this debate. This model identifies three distinct dimensions of accountability: assigned, contracted, and self-imposed accountability. Assigned accountability primarily involves government regulation and oversight, allowing for state intervention in media practices. Contracted accountability highlights the roles of the public, advertisers, and media consumers in shaping media behavior and standards, emphasizing the influence of the market and the audience in holding media accountable. Self-imposed accountability pertains to media self-regulation, where media organizations voluntarily establish mechanisms to ensure ethical conduct and adherence to social responsibility principles. This structured framework serves as a valuable tool for assessing the effectiveness of regulatory bodies and self-regulation in promoting media accountability and social responsibility.

However, when examining the practical realities of media landscapes across the world, the issue becomes inherently complex. The challenges faced by journalists and media organizations are influenced not only by internal media dynamics but also by external factors, such as state policies and political climates. In the case of Albania, a combination of assigned and self-imposed accountability mechanisms is at play. Regulatory bodies such as the Audiovisual Media Authority, hold a vital role in enforcing media laws within the audiovisual sector, including ethical violations, which result in sanctions. In 2023, a series of violations of Law no. 97/2013 “On audiovisual media in the Republic of Albania,” as well as the Broadcasting Code established by the decision of the Audiovisual Media Authority (AMA) under number 228, dated 11th of December 2017, were documented and subjected to sanctions. The infractions included the dissemination of anti-Semitic content, and in particular, the broadcast featured discussions between guests and hosts that encouraged intolerance, justified violence, and exhibited elements of racial discrimination, thus contravening established ethical norms and fundamental principles governing the activities of audiovisual broadcasts (Krasniqi, 2023).

The following sanctions were imposed:

• The subject was fined for a serious breach of the aforementioned law and code. These violations pertained to the ethical conduct exhibited during a panel discussion where the show’s moderator initially provoked the severity of the situation. The situation escalated into a state of verbal and even physical violence, culminating with one participant physically assaulting another. This incident constituted a repetition of ethical violations that encompassed insults, stigmatization, discrimination, vulgarity, and the utilization of uncontrolled and offensive language.

• The subject faced fines due to severe ethical violations committed during a live broadcast when the moderator relayed to a mother the tragic news of her daughter’s passing. This information was initially conveyed via a message from a concerned citizen who had informed the show’s editorial team about the fatal accident.

• The subject was penalized for a violation of the amended Law no. 97/2013 regarding the publication of graphic content depicting a murder without prior warning to the audience and the absence of appropriate technology to shield viewers from disturbing images. Furthermore, the video of the murder was described in detail and sensationalized by the journalist. Although it was deemed to be in the public interest to broadcast the material, it was incumbent upon the broadcaster to provide an explicit warning to the audience due to the distressing nature of the content.

• A fine was imposed on the company for instigating offensive gestures on a broadcast during a time slot when minors were likely to be watching, rendering the gesture inappropriate and unacceptable.

• A fine was levied on the audiovisual subject for an additional violation of the amended Law no. 97/2013, concerning inappropriate communication exhibited between participants on a show aired during a time when individuals of varying age groups could be watching. The recorded format of the broadcast allowed for a greater degree of control over such interactions, making the inappropriate communication more concerning, particularly given its potential to influence the mental, spiritual, and social development of children.

The National Council of Radio and Television, another regulatory body, is comprised of seven members who are supposed to represent independent intellectual perspectives, emphasizing their autonomy from political influence. However, the lack of transparent information available to the public regarding the council’s functions and activities contradicts the initial notion of fostering media democratization and heightened responsibility toward the public.

Regulatory bodies primarily oversee audiovisual media, while the media landscape, with the rise of online platforms, has become significantly more diverse and challenging to control. This shift emphasizes the need for a comprehensive media accountability framework.

The second approach of self-imposed accountability garners support from Albanian researchers (Bregu, 2023; Çipuri, 2023; Dervishi, 2023; Luarasi, 2023; Çela, 2023b), who support its integration into the Albanian context. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE, 2008) defines media self-regulation as an “endeavor to foster a democratic political culture independent of political interests, facilitating the transition from state-controlled media to media owned and regulated by civil society. The advantages of media self-regulation encompass preserving editorial freedom, reducing state intervention, promoting media quality, demonstrating media responsibility, and enabling public access to media.” Albania has established three codes of ethics, developed through extensive consultations with local and international stakeholders, indicating notable progress. However, the practical implementation of these ethics is influenced by various factors such as competition, remuneration, journalistic tradition, and professionalism. Ethical considerations tend to be invoked primarily in response to significant controversial events, which raise questions about consistent adherence to ethical standards. Dervishi (2023) highlights numerous factors conditioning the application of ethics, including intense media competition for audience share that often inclines journalists toward sensationalism. The battle for audience attention, particularly when media outlets proliferate while the audience remains constant, often favors sensational content over-responsible or constructive journalism.

To foster self-regulation, 19 Albanian media organizations established the “Alliance for Ethical Media” and instituted an Ethics Board characterized by professional integrity. This board serves as a platform for citizens to voice concerns regarding ethical breaches. The Alliance’s logo is displayed on their platforms, signifying their commitment to ethical standards, and allowing citizens to report ethical violations and seek resolution (Albanian Media Council, 2020). This initiative represents a significant step toward self-regulation in Albanian media, but the road ahead remains challenging and dynamic, emphasizing the ongoing evolution of media accountability in the Albanian context. The relationship between regulatory bodies, self-regulation, and journalistic practices within this context warrants further exploration and analysis.

The methodology employed in this study outlines the systematic approach used to conduct an empirical analysis of the public’s perception of media social responsibility. The study aims to integrate theoretical foundations derived from existing scholarly literature with empirical data. This comprehensive approach includes qualitative interviews, a focus group centered on journalists, and the distribution of questionnaires to the general population. This combination of existing academic literature on media social responsibility strengthens the research by providing a solid theoretical foundation, placing the empirical investigation within the broader academic discourse, and offering valuable context.

To ensure comprehensive data collection, we distributed questionnaires to the public, covering five major urban centers in Albania.1 Throughout this 6-month study, conducted from October 2022 to March 2023, we gathered a total of 1,321 responses. Administering questionnaires to the public ensures a holistic data collection process, capturing diverse perspectives and enriching the empirical body of work with a wide array of viewpoints (Clark and Johnson, 2017; Wilson, 2022).

A pivotal component of this methodological framework involves conducting 20 in-depth qualitative interviews with media executives, academic experts, and industry analysts. These qualitative interviews were conducted from mid-June 2023 to mid-July 2023, significantly enhancing the empirical dimension of the research by facilitating a profound exploration of expert perspectives and nuanced viewpoints regarding media social responsibility. These interviews reveal invaluable insights into the media’s roles, challenges, and societal responsibilities (Smith, 2018; Brown and Johnson, 2020).

Furthermore, this research employs a focus group of 28 journalists representing diverse media platforms. Incorporating a focus group of active journalists provides a practitioner-centric perspective, diversifying the sources of empirical data. The focus group with journalists was deliberately scheduled for September 2023 and strategically positioned as the final phase in the methodological approach. This sequencing allowed for an accumulation of insights from the public via questionnaires and in-depth interviews with key stakeholders before engaging with the practitioners’ perspective. This facilitated a more informed and contextualized discussion during the focus group sessions, as the prior phases provided a foundation for understanding public and key stakeholders’ perceptions of media social responsibility. This approach ensured that the journalist-focused discussions were enriched with the broader context of public and expert viewpoints. The perspectives and experiences shared by journalists actively involved in media production substantially contribute to a nuanced understanding of media social responsibility from the standpoint of practitioners (Williams, 2021).

Starting with questionnaires administered to the public, followed by in-depth interviews with key stakeholders, and concluding with a focus group of journalists, we strategically designed the sequential methodology in this study to maximize the depth and breadth of insights into media social responsibility. By initiating data collection with the public, we aimed to establish a foundational understanding of general perceptions and attitudes toward media ethics and accountability. This initial phase provided a broad overview of public expectations and concerns related to media responsibility. Subsequently, engaging in in-depth interviews with key stakeholders allowed for a deeper exploration of specific themes and issues identified in the questionnaire phase. These interviews provided subsequent insights into the complexities of media social responsibility within the Albanian media landscape, shedding light on the underlying dynamics and contextual factors influencing media practices. Finally, the focus group with journalists served as the culmination of the research process, providing a practitioner-centric perspective that synthesized and contextualized the findings from earlier phases. By strategically positioning the journalist-focused discussions as the final phase, we were able to leverage the insights gained from prior data collection efforts to inform and enrich the discussions with practitioners, ensuring a comprehensive and holistic understanding of media social responsibility from multiple perspectives. This funneling approach facilitated a progressive and iterative exploration of the research topic, enabling us to triangulate data from diverse sources and uncover issues that may not have been apparent through a single methodological approach. Given the intermediary role of journalists between the media and the public, they serve as conduits of information and opinion dissemination. Therefore, it was deemed crucial that they are fully informed about the perspectives of both the public and key stakeholders regarding media social responsibility. This comprehensive understanding ensures that the discussions in the focus group are not only informed but also focused, relevant, and based on factual insights. While work of Creswell and Clark (2017) may not directly replicate this sequential methodology, it serves as a prominent guide on incorporating mixed-methods approaches to enhance methodological rigor (Mishra et al., 2009; Williams, 2021).

In addressing potential practitioner bias in the final phase with journalists, we implemented several strategies to mitigate its influence on the research findings. Firstly, we ensured transparency and neutrality throughout the data collection process, emphasizing the importance of unbiased reporting and open dialogue during the focus group sessions. Additionally, we employed reflexive methodologies, drawing on Alvesson and Sköldberg’s (2017) concept of “triple hermeneutics” to encourage critical self-reflection among researchers, participants alike, and societal discourses. This approach allowed us to acknowledge and account for any inherent biases or preconceptions that may have influenced the interpretation of data. By embracing this framework, we aimed to navigate the power dynamics inherent in the interview situation and promote reflexivity among all involved parties. This approach allowed us to minimize the risks of expert respondent data contamination and bias.

To examine the public’s perception of social media responsibility, a meticulously designed questionnaire was used. The questionnaire featured “a-d” alternatives. The design process included pilot testing with students and staff at “Aleksander Moisiu” University in Durrës (Albania), ensuring an effective calibration of the questions. This rigorous method aimed to reduce ambiguity, enhance question relevance, and bolster the reliability of the data collected.

This questionnaire was structured into five main sections:

1. The first section collected general information from the respondents, including demographic data, their primary media consumption, and the media sources they trust the most.

2. The second section focused on the public’s perception of media responsibility. Respondents were asked to select the main principle that best represents social media responsibility. Additionally, they were asked to identify which of these principles they did not perceive to be reflected in media social responsibility. The section also sought their opinion on the primary role of media organizations in society and which theoretical perspective best described the essence of media responsibility today. The main principles of media social responsibility were derived from a literature review, summarized in Table 1.

3. The third section of the questionnaire aimed to collect data on how the public perceives the media’s social responsibility evolution. Respondents were asked to identify events that have influenced the evolution of media responsibility in recent years.

4. The fourth section collected data on the public’s perceptions of the challenges faced by the media in maintaining social responsibility, the impact of disinformation and fake news on public trust in the media, and potential solutions to address these challenges.

5. The fifth section aimed to understand the strategies or initiatives that the public believes media organizations should pursue to enhance their social responsibility in the digital age.

The qualitative interviews were conducted to gather insights from experts and media management levels. They aimed to explore the trends in social responsibility developments in Albania, how these trends have influenced the relationship between the media and the public, the fundamental principles of implementing standards in the media landscape, the challenges associated with fulfilling this social obligation, and the role of regulatory bodies in enhancing media social responsibility. Additionally, the interviews delved into the stages and developments related to media regulation.

The focus group with journalists was intentionally positioned as the final phase in the methodological approach, serving as an open forum to deeply analyze social responsibility from the perspective of practitioners. This strategic placement facilitated the sharing and contrasting of perspectives between journalists and the public, aiming to increase journalists’ awareness of public expectations. The focus group analysis centered on the challenges faced by journalists today in fulfilling their social responsibility toward the public and society as a whole.

By cross-referencing data derived from interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires, this comprehensive approach, guided by methodological insights of Fink (2015), enhanced the methodological validity, leading to a more profound understanding of public perceptions concerning media social responsibility.

We employed specialized statistical tools, specifically IBM SPSS-type software, to analyze the data derived from public questionnaires. In addition, we utilized Pearson’s correlation analysis to explore potential relationships among responses from the public. A positive correlation indicates agreement between two questions, while a negative one reflects disagreement. The goal was to gain a deeper understanding of the public’s perceptions regarding the fundamental principles of media social responsibility. Pearson’s correlation is a well-established statistical method for assessing the strength and direction of relationships between variables (Pallant, 2016). It provides a numerical value ranging from −1 to 1, indicating the strength and nature of the relationship between the two variables. A positive correlation nearing 1 implies that these two variables change in the same direction. This approach aligns with the methodological rigor advocated by Fink (2015) in survey-based research and contributes to a deeper understanding of complex media-related phenomena (Deuze, 2011; Fink, 2015).

Throughout the research process, we rigorously adhered to ethical obligations, ensuring informed consent from all participants involved in the study. This included maintaining strict confidentiality and upholding the highest ethical standards, as guided by established protocols and exemplified in scholarly work of Smith (2019).

The analysis of public perceptions concerning media responsibility involves three distinct dimensions. First, it explores the expectations of the public regarding how the media should act responsibly. Second, it scrutinizes their evaluations, focusing on what they discern as consumers of information. Lastly, it explores their beliefs regarding the responsibilities of media organizations.

The analysis of data regarding the public’s expectations of the media’s social responsibility reveals a discernible divergence of perspectives within the Albanian public. This divergence becomes more apparent when scrutinizing their anticipations and assessment of the key responsibilities attributed to the media. The insights from this analysis illustrate that the Albanian public holds varied and occasionally conflicting expectations of the media, indicating the intricate nature of the media’s social responsibilities. It is evident that a substantial segment of the public, constituting nearly 27% of respondents, identifies “Accuracy and Truthfulness” as the principal obligation of the media. This perspective underscores the strong demand for accurate and truthful reporting, underscoring the conventional role of the media as providers of reliable information. It highlights the significance the public places on media organizations prioritizing rigorous fact-checking and objectivity. This expectation not only reflects the public’s desire to be well-informed but also indicates their reliance on the media as a credible and reliable source of information.

Approximately 16% of respondents emphasize “Transparency” as a pivotal responsibility of the media. This implies that the public expects media organizations to maintain openness and clarity regarding their operations, including the disclosure of sources, transparency in decision-making processes, and addressing potential conflicts of interest. The emphasis on transparency reflects a growing concern among the public about the credibility of news and the need to comprehend the rationale behind the selection and coverage of specific stories. It also indicates that the public values media organizations that exhibit accountability and transparency in their practices (Basha, 2023).

The fact that 13% of respondents prioritize “Accountability” as a primary responsibility suggests that the public anticipates the media to function as a vigilant watchdog, holding influential institutions and individuals accountable for their actions. This accentuates the media’s role in ensuring that individuals in positions of authority remain answerable to the public. It mirrors the public’s aspiration for media organizations to actively contribute to safeguarding democratic principles and guaranteeing checks and balances within society.

Approximately 12% of respondents believe that the primary responsibility of the media lies in serving the “Public Interest.” This underscores the expectation that media organizations should prioritize stories and content that contribute to broader societal welfare. The public desires the media to be driven by a sense of duty in terms of informing and enlightening the public, ultimately contributing to the amelioration of society (Risto, 2023).

The allocation of 15% of respondents to “Independence” accentuates the public’s inclination toward media organizations that remain uninfluenced by external pressures, particularly those of a political or commercial nature. Independence ensures that the media can engage in impartial reporting and present a diverse array of viewpoints, characteristics that are quintessential for the functioning of a democratic system (Çela, 2023a).

The choice of “Sensitivity and Responsibility” by 14% of respondents suggests the public’s expectation that the media approaches sensitive topics and issues with care and responsibility. This implies that the media should exercise caution in presenting content, considering the potential impact on their audience, especially in case of tragic events, where sensitivity is a prerequisite (Nole, 2023).

While only 2% of the respondents chose “Community Engagement,” it signifies a smaller yet substantial segment of the public that envisions the media actively participating within the community. This participation can manifest itself in the form of reporting on local issues and engaging in community events and initiatives.

The lack of responses for “Environmental Responsibility” may suggest that the public does not consider environmental concerns as the media’s primary responsibility, indicating that they may attribute greater significance to other entities or actors in addressing environmental issues (Table 4).

The data collectively indicate the high expectations of the Albanian public concerning the media, specifically in terms of accuracy, transparency, accountability, and serving the public interest. These expectations align with the foundational principles of journalism and the media’s pivotal role as a cornerstone of democracy. Prioritizing these responsibilities ensures that the media organizations are better positioned to cultivate and sustain the trust of their audience. Comprehending and acknowledging these expectations is of paramount importance for media entities striving to effectively fulfill their societal role.

The data regarding what the public perceives as the main feature not reflected by the media provides valuable insights into areas where the media may fall short in meeting public expectations of social responsibility. The responses indicate a diverse set of concerns and expectations. The most substantial 33% of respondents believe that the media does not adequately reflect the public interest. This finding underscores the public’s expectation that media organizations should prioritize stories and content that serve the broader societal good.

A considerable 14% of respondents identified diversity and inclusivity as not fully reflected by the media. This suggests that the public expects the media to enhance the representation of diverse voices and perspectives, fostering inclusivity and avoiding bias or exclusion. An equal 14% of respondents expressed concern about the absence of sensitivity and responsibility in media content. This highlights the expectation that the media should handle sensitive topics and issues with care, especially in situations requiring sensitivity, such as tragic events (Xhokaxhiu, 2023).

13% of respondents identified independence as lacking in the media. This indicates the expectation that media organizations should strive for greater independence, free from external influences, particularly political or commercial pressures. A significant 12% of respondents believe that accountability is a main feature lacking in media content. This emphasizes the public’s desire for the media to hold powerful institutions and individuals responsible for their actions, ensuring transparency in accountability. A notable 7% of respondents highlighted transparency as an aspect that the media does not adequately reflect. This implies that media outlets should be more open about their operations, sources, and decision-making processes.

While a smaller percentage of 5%, explicitly mentioned accuracy and truthfulness, it is important to note that some members of the public still find this aspect lacking in media content. This suggests a need for improvement in ensuring consistently accurate and truthful information.

Only a small 2% of respondents identified community engagement as a feature not reflected by the media. Although it is considered less of a concern, some members of the public still expect media organizations to be more actively involved in community-related issues and initiatives.

Notably, no respondents indicated environmental responsibility as a feature lacking in media content. This implies and may reinforce the perception that the Albanian public may not perceive environmental issues as a primary responsibility of the media (Table 5).

In summary, the data expose a complex landscape of public perceptions. The media responsibility is perceived as lacking in various aspects, with the most significant concerns being the representation of public interest and diversity, accountability, and independence.

The data on public beliefs about the primary duty of media organizations in the context of social responsibility reveal a diversity of perspectives, shedding light on the multifaceted role that media is expected to play in society. The highest percentage of respondents, 42%, believe that the primary duty of media organizations is “providing accurate and unbiased information to the public.” This finding underscores the fundamental role of the media as a reliable source of information and the importance of journalistic integrity. The public expects media organizations to prioritize the dissemination of facts and unbiased reporting, aligning with the traditional understanding of journalism as the Fourth Estate-a crucial source of information and accountability in a democratic society. Following closely, 36% of respondents perceive the primary responsibility of media organizations as “holding those in power accountable and acting as a watchdog.” This indicates a strong desire for the media to act as a check on power, ensuring transparency and accountability among government officials, institutions, and other influential actors. It reflects the public’s expectations for the media to play a vital role in upholding democratic values by acting as a watchdog.

Approximately 16% view “prioritizing moral and ethical standards aiming at public education” as the primary duty of media organizations. This perspective highlights the role of media in shaping public discourse, values, and education. It suggests that a segment of the public believes that media organizations should not only inform but also contribute to the moral and ethical development of society. A smaller percentage, 6%, perceives media responsibility as subjective and varying among organizations. This response acknowledges the diversity of media outlets and their distinct missions and values. It implies that different media organizations may have different approaches to social responsibility based on their unique goals and audiences (Table 6).

Analysis of the data regarding theoretical perspectives on media responsibility reveals that 44% of the Albanian public aligns with the “Social Responsibility Theory.” This indicates a prevailing belief that media should prioritize serving the public interest and providing diverse viewpoints. This perspective highlights the public’s desire for media to function as a cornerstone of a democratic society, offering information and perspectives that are essential for an informed citizenry.

The “Economic model” and the “Libertarian perspective” each garnered significant support at 28 and 24%, respectively. This implies that a substantial portion of the public recognizes the commercial nature of media and values media freedom with minimal government intervention. The strong representation of these perspectives signifies a recognition of the media’s role as a business entity driven by profit while still advocating for a degree of media freedom.

Conversely, the “Authoritarian model” received the least support at only 4%. This suggests that a very small portion of the public endorses strong government control and censorship of media. Such low support for the Authoritarian model is a clear indication that people prefer media independence and limited government involvement in regulating media content (Table 7).

These data reflect diverse perspectives regarding the evolution of the media’s role today. Approximately 45% of the respondents believe that the media’s role has evolved significantly, embracing new technologies and engaging more interactively with the audience. This means that the public is aware of the transformative impact of digital platforms and the media’s adaptation to its changing landscape, making clear the need to shift toward more interactive and engaging content delivery. Around 36% of respondents express a contrasting view, suggesting that media has lost its traditional role as a reliable source, and sensationalism has taken over, implying a degree of skepticism regarding media practices and their influence on public discourse. It may reflect concerns about sensationalism and a perceived decline in journalistic standards.

A smaller but notable group, approximately 12%, believes that the media’s role has remained somewhat consistent but has become faster and more accessible with digital platforms. This perspective recognizes the continued importance of traditional media functions but acknowledges the impact of technology on the speed and accessibility of information. A minority of respondents, approximately 7%, maintain that the media’s role has not changed much and still primarily serves to inform and entertain. This view reflects a more traditional understanding of media roles, emphasizing their enduring functions (Table 8).

The data concerning the impact of various factors on media responsibility reveal that the public recognizes multiple factors influencing it. Most of the respondents, approximately 43%, believe that events like the spread of fake news and misinformation have negatively impacted media responsibility. This view underscores the growing concern over disinformation and how it influences the trust of media. It suggests that media organizations are expected to take proactive measures to counteract the spread of false information and maintain ethical journalistic standards. Around 24% of respondents consider the rise of social media and user-generated content as a significant factor affecting media responsibility. This perspective acknowledges the transformative role of social media in shaping the dissemination of information and highlights the need for media to adapt to new platforms and audience behaviors. Approximately 23% of respondents attribute the decline in responsible journalism to economic pressures. This view underscores the challenges faced by media organizations in balancing financial sustainability with ethical journalism, implying that economic factors have a substantial impact on media responsibility and may require strategies to address potential conflicts of interest. A smaller portion of respondents, approximately 10%, perceive media ethics as somewhat constant, with new technologies merely offering different means of storytelling. This perspective suggests a more stable view of media responsibility, emphasizing enduring ethical principles irrespective of technological changes.

A substantial majority of respondents, around 43%, identify misinformation and fake news as the most pressing challenges for media organizations, highlighting again the critical role of media in countering disinformation and maintaining trust. Addressing misinformation is a top priority for media organizations in fulfilling their societal responsibilities. Approximately 23% of respondents point to economic pressures as a significant challenge causing a decline in media’s ability to maintain quality journalism. This view highlights the financial constraints and economic factors that media organizations contend with in delivering responsible journalism. Addressing economic challenges while upholding quality journalism is a complex issue that needs to be tackled.

About 20% of respondents express concerns about the rise of partisan media outlets and echo chambers, making unbiased reporting difficult, reflecting thus the challenges associated with media polarization and the potential consequences for balanced and impartial journalism. Media organizations need to navigate this landscape to maintain their responsibility in providing diverse perspectives. A minority of respondents, constituting about 14%, consider public distrust in media as the most significant challenge. This implies that rebuilding and sustaining public trust emerge as central issues for media organizations. It underscores the importance of transparent and accountable journalism to overcome public skepticism (Table 9).

The data regarding the public’s perspectives on strategies for addressing challenges and improving media responsibility provide potential approaches. A significant portion of respondents, about 39%, suggest that media organizations should invest in fact-checking teams and promote transparency in their reporting. This viewpoint highlights the importance of internal measures to ensure accuracy and transparency. It implies that these organizations should take active steps to verify information and openly communicate their reporting processes to the public. Approximately 24% of respondents emphasize that collaboration with tech companies is essential in combating misinformation and improving content distribution, highlighting the importance of partnering with technology companies to address challenges posed by misinformation, especially in the digital age, to develop tools and solutions for identifying and addressing misinformation. 22% of respondents stress the importance of media remaining independent from external influences and its role in upholding media responsibility. Media should resist external pressures, particularly political or commercial, to ensure responsible journalism.

Around 15% of respondents believe that journalists should follow ethical standards and educate the public. This viewpoint places the responsibility of upholding ethical principles and engaging in public education on journalists themselves. Ethical journalism practices and public outreach by journalists can play a crucial role in addressing media responsibility challenges (Table 10).

While analyzing public perceptions of media responsibility and the challenges it faces, several correlations were observed shedding light on the intricate relationships within these domains.

• Public expectations vs. public evaluation: We found a positive correlation between public expectations (PE) and the importance of “Accuracy and Truthfulness” (AT) (r = 0.385), indicating an increase in their expectation of accuracy and truthfulness and a positive evaluation of the media.

• Conversely, a negative correlation emerged between public expectations (PE) and “Transparency” (TR) (r = −0.216), suggesting that higher expectations for transparency are associated with a more critical evaluation.

• Public beliefs vs. understanding the evolution of media social responsibility: A positive correlation was observed between public beliefs (PB) and the belief that “the role of media has evolved significantly” (UR) (r = 0.429), indicating that those who believe in a significant evolution of media roles tend to align with certain public beliefs about media responsibility.

• In contrast, a negative correlation was found between public beliefs (PB) and the belief that “media has lost its traditional role” (UR) (r = −0.363), implying that individuals who believe in the loss of traditional media roles are less likely to share certain public beliefs about media responsibility.

• Challenges vs. strategies: A positive correlation was identified between perceived challenges (CH) and suggested strategies (ST) to enhance media social responsibility (r = 0.231), signifying that those who perceive media challenges are more inclined to propose strategies aimed at addressing these challenges.

• Impact of issues vs. the role of media literacy and tech collaborations: A positive correlation was noted between the perceived impact of issues (II) and the role of media literacy and tech collaborations (RT) in mitigating these issues (r = 0.141). This suggests that individuals who recognize the impact of issues such as fake news and misinformation are more likely to support the role of media literacy programs and technology collaborations in addressing these challenges.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the complex landscape of public perceptions regarding media social responsibility in Albania. The Albanian public holds diverse perspectives and, at times, conflicting expectations concerning the roles of the media and where they perceive it falls short in meeting these expectations. One prominent observation from the data pertains to the strong emphasis placed on accuracy and truthfulness. This highlights the public’s strong demand for precise and reliable reporting. Furthermore, the emphasis placed on transparency represents another substantial expectation. It reflects the increasing public concern about the credibility of news and the necessity to comprehend the processes underlying media coverage. Transparency in media operations and the disclosure of information sources are deemed essential for maintaining public trust.

The public’s call for accountability highlights the media’s role as a vigilant watchdog, ensuring that influential institutions and individuals are held responsible for their actions. The media should actively contribute to safeguarding democratic principles and maintaining checks and balances within society. Additionally, the respondents’ preferences for “Public Interest” underscores their expectation that media organizations must prioritize content beneficial to the broader societal welfare. This accentuates the public’s desire for the media to be a source of enlightenment and information that ultimately contributes to societal betterment.

The selection of independence signifies the public’s inclination toward media organizations that remain uninfluenced by external pressures, particularly of a political or commercial nature. Independence ensures impartial reporting and diverse perspectives, both of which are integral to a democratic system. On the other hand, the choice of sensitivity and responsibility that the media must handle sensitive topics with care, exercising caution with content, particularly in situations where sensitivity is paramount, such as the coverage of tragic events.

In contrast, the data also shed light on aspects that the media inadequately reflects. The most significant concern revolves around the perceived neglect of the public interest. This underscores the public’s expectation that media organizations prioritize content serving the greater societal good.

The concern for diversity and inclusivity is evident, implying that the media needs to provide better representation of diverse voices and perspectives, highlighting the desire for inclusivity and the avoidance of bias or exclusion.

Regarding the most pressing challenges for media organizations, the data highlights a clear concern about misinformation and fake news, identifying it as the most pressing. This underscores the critical role of the media in countering disinformation and maintaining public trust.

The qualitative data from key stakeholders and journalists reveal several crucial insights into media social responsibility within the Albanian context. Firstly, key stakeholders stress the importance of media democratization and information verification as integral aspects of media responsibility. They emphasize the necessity for media organizations to prioritize transparency and accountability to the public, aligning with broader societal expectations for ethical and responsible journalism. Moreover, journalists highlight the challenges associated with maintaining accuracy in information and safeguarding the privacy and confidentiality of sources in their reporting endeavors. They also emphasize the paramount importance of upholding integrity and ethical principles, particularly in the face of external pressures such as sensationalism and clickbait tactics. Importantly, the qualitative data underscore a notable gap in the understanding and implementation of media social responsibility, as principles such as diversity and inclusivity, community engagement, and environmental responsibility are often sidelined in practice. This discrepancy reveals a potential disconnect between theoretical ideals and practical application within the Albanian media landscape, highlighting areas for improvement and further exploration in fostering a more comprehensive approach to media responsibility.

The findings of this study offer crucial insights into the complex relationship between the media and the public in Albania. Understanding the expectations, concerns, and beliefs of the Albanian public regarding media social responsibility is pivotal for media organizations seeking to effectively fulfill their societal role.

The data emphasizes the public’s strong demand for accurate, truthful, and accountable journalism. It also highlights the need for media transparency, independence, and responsibility, while respecting sensitivity and diversity. These expectations align with the fundamental principles of journalism and the media’s central role as a cornerstone of democracy. Media organizations that prioritize these responsibilities are better positioned to cultivate and sustain the trust of their audience. The identified challenges, including misinformation, economic pressures, partisan media, and public distrust, require careful consideration by media organizations. Addressing these challenges through measures such as fact-checking, transparency, collaboration, independence, and adherence to ethical standards is crucial to enhancing media social responsibility.

The application of Pearson’s correlation provides insights into the complex web of relationships between public expectations, beliefs, evaluations, challenges, and suggested solutions in the context of media responsibility. It is important to acknowledge that these correlations are derived from the data collected in our survey and should be interpreted within the specific scope of this study.

In conclusion, the study’s findings provide valuable insights into public perceptions of media responsibility in Albania, providing a roadmap for media organizations to navigate the evolving media landscape and fulfill their vital role in society. The prominence of upholding the highest ethical and journalistic standards is underscored, emphasizing the maintenance of public trust and contribution to societal betterment. The multifaceted nature of these findings highlights the need for continuous research and collaboration between media, academia, and the public, ensuring that media remains a reliable source of information and a guardian of democracy.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals for participation in the study and for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in the article.

PS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This work is dedicated to our students. We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the bachelor students of Aleksandër Moisiu University in Durrës, specializing in Public Relations. Their valuable contribution and unwavering commitment to assisting with the distribution and collection of questionnaires across various cities in Albania were instrumental in the success of this research. Their enthusiasm and hard work exemplify the spirit of collaboration and academic excellence. We deeply appreciate their efforts in advancing the field of media studies. Thank you for being an integral part of this endeavor. Also, we extend our gratitude to all the media directors, professors, and journalists who supported us without hesitation and significantly contributed to improving the findings of this study. We acknowledge the invaluable contribution of the reviewers to elevating the quality of this research. Their constructive comments and suggestions have played a pivotal role in refining the methodology, strengthening the analysis, and ensuring the credibility of the findings. Their expertise and thoughtful critiques have been instrumental in enhancing the robustness and rigor of our study, and we are grateful for their valuable contributions to the scholarly discourse in this field.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.