94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 08 February 2024

Sec. Media Governance and the Public Sphere

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1316677

Exemplification, the use of emotionally evocative messages to elicit a response based on impression formation, are frequently present in news messages. The present study examined the use of positive vs. negative exemplars in news stories to determine the role of stigmatization and securitization in these messages and whether this impacts perceptions of the importance and quality of news. This study tested exemplification's effects using three conditions: positive, negative, and non-exemplar news stories—two valences of exemplification and a control condition. Results indicate that as stigmatized impressions increase, securitization decreases, valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on the quality of news, and valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on the general interest of the issues. Implications suggest news message creators should consider positive exemplars in place of negative exemplars to minimize unintended negative effects.

People consume news information daily, whether directly or indirectly. Often times, those messages incorporate exemplars, emotionally evocative representations of a large idea (e.g., Zillmann, 2006). When people process exemplification messages, complex risk conditions are simplified through easily recalled words and images that are both persuasive and emotionally evocative. News media coverage often incorporates exemplars that are intended to grab and maintain audience attention (Spence et al., 2016). These exemplars often provoke a negative emotional response in viewers. These can contribute to negative social factors, such as stigmatization, attributing a socially discrediting identity mark to a certain group or individual (e.g., Wang, 2019, 2020; Li, 2023), or securitization, perceiving an issue as more severe than other oft-politicized issues based on threat to the nation's or public's security broadly (e.g., Hashim, 2023). Exemplification messages used in health campaigns might engage negative exemplars of health effects to deter unhealthy behavior, such as images of former smokers with tracheotomies or other jaw removal to deter others from smoking or encourage current smokers to quit. Political messages can engage negative exemplars to convince publics to support otherwise ethically questionable measures, such as detaining young children in immigration camps to deter illegal immigration.

While exemplars to have the possibility to engage readers more effectively than base rate information, negative social outcomes resulting from the use of negative exemplars in news stories prompts important ethical questions about the way news stories are developed and presented. Specifically, if news stories are written to evoke an emotional response from readers, but in so doing a group of the population is stigmatized as a result, it is important to consider whether increasing readership is more important than the wellbeing of the stigmatized group.

Much of exemplification research in communication focuses on the role of negative exemplars and organizational response (e.g., Westerman et al., 2012; Spence et al., 2015, 2016). Less is known about the role of positive exemplars and audience response. The study at hand posits that, when crafted intentionally, positive exemplars could elicit an emotional and attitudinal response equal to that of negative exemplars, but without the negative social factors. Importantly, positive emotions can “broaden people's attention and thinking, undo lingering negative emotional arousal, fuel psychological resilience, build consequential personal resources, trigger upward spirals toward greater well-being in the future, and seed human flourishing” (Frederickson, 2004, p. 1375). This study suggests that, if effective, positive exemplars could serve as a preferable means of capturing audience attention, but doing so in a way that does not negatively impact a segment of the population or organization.

The purpose of this research is to examine the role of positive vs. negative exemplars in eliciting emotional and attitudinal response to news material from consumers. Specifically, we seek to understand whether positive exemplars elicit an equal response to the news story as negative exemplars, and the extent to which negative exemplars elicit a stigmatizing or securitizing response in readers. We experimentally test the overarching hypothesis that commonly used negative exemplars may effectively elicit engagement with news messages, but carry with them a stigmatizing effect. Then we explore the connections between stigma, securitization, and other perception effects that valences of exemplification could evoke. In this manuscript, we begin by discussing relevant literature on exemplification theory, stigmatization, and securitization. We then offer our hypotheses and research questions, followed by a detailed description of our methodological approach. Next, we present the results of this experiment, and interpret these in the discussion. Finally, we offer practical implications of these findings and concluding remarks.

Exemplification theory is rooted the notion that everyone is familiar with examples and how these can represent large, complex ideas in intelligible ways. Key to exemplification is the “recognition of shared features between an example (a.k.a. exemplar) and the exemplified, as well as between all possible examples of the exemplified” (Zillmann, 1999, p. 72). Exemplars are essentially vivid, emotionally evocative words, phrases, images, or sounds that function as cognitive shortcuts to elicit meaning about more complex situations or ideas. Exemplars are easy to understand with minimal analytic thought.

Exemplification operates in three distinct ways. First, it argues that people evaluate information subjectively, relying on biases in making their own assessment, rather than using a systematic assessment process. It supposes that perception is altered through exposure to exemplars when viewed frequently and recently. Second, an exemplar is representative of similar cases through one instance, and functions by means of a quantification heuristic. The frequency of exemplars is continually monitored and the prevalence of a particular exemplar directly impacts its retrieval from one's memory. Third, exemplars can have a positive or negative valence. However, applications of exemplification theory in extant literature largely emphasize the latter.

Exemplification theory acknowledges the large amounts of information individuals filter daily, and argues that the use of various heuristics serves as cognitive shortcuts to assist with information processing (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993; Zillmann, 2002, 2006). One such heuristic is exemplified properties dispersed through media channels and dispensed to an extensive public. Exemplars are simplistic, abstract depictions that depend on base-rate information that is easy to retrieve. Exemplars are made memorable through the use of “visually vivid and emotionally strong” content (Aust and Zillmann, 1996, p. 788). Still, base-rate information “seems to be influential when it comes to first-order reality judgments,” and should not be discounted altogether (Kramer and Peter, 2020, p. 215). Exemplars can come in the form of “any combination of image and text” that influences perception when viewed frequently and recently (Zillmann, 2006, p. S224). Exemplars also have the potential to elicit persuasive effects (Kramer and Peter, 2020).

Tran (2012) examined the ways in which multimedia additions in the online environment work to further the effects of exemplification. He suggests that, “in online environments, multimedia additions such as pictures, graphics, pull quotes, and testimonials in video or audio are largely used as extra text enhancements” (p. 399). Arguments that could be conveyed through the written word are made more salient through the use of additional media forms. Moreover, due to the ease with which exemplars are retrieved, “multimedia enhancements stick out and avail themselves more readily; therefore, online users rely on them as a basal form of representation when making judgment about issues reported in the accompanying text” (p. 411).

Yu et al. (2010) found that exemplars were effective in promoting perceived efficacy toward fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) and increasing prevention intention, perceived severity, and perceived fear toward FASD. Similarly, Sarge and Knobloch-Westerwick (2013) found that, in health information seeking on the Internet about weight loss, the incorporation of exemplars (as opposed to base-rate information) increased both self-efficacy and satisfaction among website visitors. While the intended outcomes of both of these examples improve the health of the targeted segment of the population, it should be noted that the use of negative exemplars, such as the undesirability of an overweight body, has the potential to further stigmatize overweight individuals in society more broadly. Zillmann (2006) asserts that “exemplars conveying others' emotional experiences and eliciting appreciable affective reactivity exert disproportional influence” over an extended period and produce “overestimates of their prevalence and heightens assessments of risk to personal welfare” (p. S232). While potentially useful in health and risk reduction campaigns, exemplification may paint an impartial and incomplete picture in audience members' minds, which may then both reduce effectiveness and warrant unintended/unwanted reactions. For example, if this results in the (not directly intended) stigmatization of a certain group, the positive effects of exemplification messages may be outweighed by the negative messages toward the stigmatized group. This is an important ethical consideration when deciding to employ exemplification in messages. In the next section, we outline extant research surrounding social stigmatization.

Goffman (1963) conceptualized stigma as any attribute that could be considered discrediting for the individual who possesses it. Stigma functions to set the stigmatized individual apart from others on a social level, but also carries an inherently negative value. Stigma communication works first to distinguish the individual and then to categorize them as a separate social entity. Stigma also carries with it content cues indicating that (a) belonging to this stigmatized group is linked to some degree of physical and/or social peril and (b) the stigmatized individual is in some way responsible or to blame for it (Smith, 2007). In other words, stigma first separates, calls attention to, and categorizes a person based upon a negatively-valenced attribute; it then indicates that this attribute is damaging or threatening, and that the individual is responsible for the stigmatized identity. Stigma is discursively enacted, so the stigmatized individual experiences that stigmatization as a result of social discourse, which can be perpetuated through media channels.

There are two key types of stigmatized identities—those which are easily viewable to others and those that are concealable (Goffman, 1963). Public, discredited stigmas, include things such as body weight, physical disability, disfigurement, or any social stigma that cannot easily be hidden by the stigmatized individual. Discreditable stigmas are those which an individual could hide from others should they wish to. These discreditable stigmas include alcoholism, mental illness, HIV/AIDS, or a criminal history. In exemplification messages, discredited stigmas are easier to represent visually, though as news stories are developed both discredited and discreditable stigmas may be present.

Both discredited and discreditable stigmatized identities have long been a concern in public messaging. For example, utilizing discredited stigmatized identities in health campaigns, even for positive reasons, has been cautioned against, as goodwill and progressive agendas do not guarantee an absence of exploitation or further stigmatization (Wang, 1992). Wang (1992) describes how campaigns against drunk driving have commonly used imagery such as wheelchairs and handicapped parking access to prevent the behavior, while perpetuating the stigma that accompanies being physically disabled. Such depictions perpetuate negative implications and discourse around a specific group, many of whose members have no experience with the negative behavior.

Discreditable stigma can be equally, if not more, damaging to an individual than discredited stigma. Messages that engage hidden, discreditable stigmatized identities run the risk of reinforcing negative discourse around an already marginalized group. For example, Guttman and Salmon (2004) suggest that HIV/AIDS prevention campaigns are indicative of the problematics associated with discreditable stigmatized identities. These campaigns make specific decisions regarding “who – in terms of race, gender, age and sexual orientation – is depicted in having HIV/AIDS... as victims or as empowered” (p. 547). The hidden nature of certain stigmatizing conditions makes it difficult to determine who portrays these identities. In the context of exemplification in news messages, it becomes an ethical question when considering how news content is presented, whether it is paired with images, and who is portrayed, specifically when the message hinges on negative exemplars with a potential stigmatizing effect. In the next section, we describe the role of securitization in influencing receivers' perceptions of oft-politicized issues.

Securitization (Buzan et al., 1998) describes the type of political discourse that transforms an understanding of an issue as more severe than other typically-politicized issues.

The severity is predicated upon framing the issue as representing a threat to some type of nation's or public's security in a broad sense, such as economic wellbeing, health, sovereignty, or cultural identity. Consequently, a discourse around the securitized issue invites some form of extraordinary measures to address the risk. Therefore, securitization is posed as an impactful persuasive tool. As such, securitization is often embedded in news stories as a negative exemplar, such as stories suggesting that COVID-19 cases in the U.S. are increasing as a result of illegal immigration.

The seminal works on securitization by Buzan et al. were rooted in critical constructivist theory and rendered the concept as a normatively problematic discursive tool that is rather misused to shift a topic from conversation of politics-as-usual to “securitize it”—so essentially to remove democratic constraints against certain measures. As the theory developed over time, both its normative orientation and its paradigmatic rooting have been revisited and revised. Floyd (2011, 2019a,b) argued that there indeed are securitization-worthy issues, where politics-as-usual is not efficient or appropriate enough because a truly existential security threat is encountered by the community, for example climate crisis. In such circumstances, it would be preferable to involve government-sponsored interventions or even use of executive power. A useful illustration of securitization as a normatively preferable concept is encompassed in the calls for decisive, even if repressive, measures toward limiting the spread of infection during the recent COVID-19 pandemic (McCarthy, 2020). In terms of paradigmatic position, Baele and Thomson (2017) argued it is crucial to expand the experimental research into securitization processes into the social-scientific paradigmatic territory to verify the validity of causal claims within the construct. Such studies are still rare but have actually been conducted in the field of communication and media (Vultee, 2010; Vultee et al., 2015). However, the researchers primarily explored the negative interpretations of these securitizing effects. Just in recent scholarly conversations within the field of crisis and risk communication, it has been voiced that securitization should be further explored in terms of its strategic implications (Schraedley et al., 2020).

As mentioned, one of the main tenets of stigma includes the perception of peril and threat to a societal unit. Securitization research shows that the stigmatized were viewed as the carriers or perpetrators of the securitized threat, for instance the negative stereotypical tropes of dangerous immigrants or people with infections such HIV/AIDS (Sjostedt, 2008; Seckinelgin et al., 2010; Galemba et al., 2019). Thus, stigma has been primarily theorized as a companion phenomenon to securitization; particularly, repressive measures that would normally be frowned upon were more likely accepted in retaliation actions against the stigmatized people. It is crucial to further assess the other direction, where extraordinary measures are arguably truly warranted to protect and assist the vulnerable groups (Sjostedt, 2008). Positive exemplification can offer specifically useful lens for such empirical examination.

Our study therefore offers novel exploration into interconnections between exemplars in news coverage and the subsequent reactions that involve perceptions of stigma and securitized views on the issues of focus. Furthermore, this study allows for comparison between the exemplification-to-stigmatization effects on outcome perceptions relevant to exemplification, such as evaluations of the interest of the issue of focus or the news quality. Specifically, exemplars are used to increase and maintain audience engagement, and to encourage audiences to act or think in a particular way based on the credibility and evocativeness of the message. If these exemplars are negative, they may carry with them a stigmatizing and/or securitizing effect. If this is the case, yet the news content was considered of interest and high quality, it is likely that the stigmatizing and/or securitizing effect would be stronger. Alternatively, if the exemplars are positive, and the news content is considered high quality and of interest, it may be possible to use such engaging exemplification in news messages while avoiding the negative securitizing and/or stigmatizing effect. These are valuable proxies that reflect on the formation of a set of attitudes around issues that are articulated through politicized media discourses. In the next section, we outline and justify the research questions and hypotheses that guide this examination.

Literature demonstrates that news stories frequently cover and reflect tendencies and biases on the matters of crisis, risk, and security, such as immigration or health (e.g., Kim et al., 2011; Jarlenski and Barry, 2013; Quinsaat, 2014). The coverage often results in conditional, but nevertheless existing and detectable, effects on audience's perceptions and attitudes (e.g., Puhl et al., 2013; Vultee et al., 2015; Riles et al., 2020), intended behaviors (e.g., Dardis, 2007; Spence et al., 2015), and actual behaviors (e.g., Trumbo, 2012). For instance, effects of negative exemplification were documented (e.g., Spence et al., 2015, 2016), but further empirical research is paramount to specify the dimensions of the effects of positively exemplified news.

Several studies looked at stigmatizing effects, while operationalizing the negative stigma-evoking features of the news content along various theoretical perspectives (Puhl et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2019; Riles et al., 2020). The focus tends to be on what the negative portrayals do in comparison to not-so-negative, neutral, or somewhat-positive portrayals. Ren and Lei (2020) explored destigmatizing effects of positive frames about HIV/AIDS, defining those as optimistic (vs. pessimistic), for example. Positive exemplars are not merely simple positive frames. We pay attention to the particular effects of the distinct and evocative positive constructs as theoretically-soundly constructed through exemplification. Therefore, a consistent effect should be observed with positive exemplars also when varying the context. The reviewed studies tended to focus on just one context such as health-related issues (Gwarjanski and Parrott, 2018; Smith et al., 2019) or minority population integration type of issues (Riles et al., 2020). Thus, with Hypothesis 1 we begin by asserting a directional positive destigmatizing effect across the contexts:

H1: Positive exemplars will decrease the stigmatization of impacted individuals.

The exploration should illuminate whether, as H1 asserts, positive exemplars represent a positive destigmatizing impact in comparison to both the news that carry a negative exemplar and neutral news:

RQ1: How will stigmatizing effects differ as a result of exposure to neutral, positive, and negative exemplars?

The following lineup of hypothesis and research questions explores the additional array of possible positive effects that can be achieved through exemplification, such as securitization, perception of news quality, and perceptions of issue interest. Negative exemplification may be believed to increase a likelihood of such outcomes, while the similar utilitarian potentials of positive exemplification may be underestimated.

Experimental studies of securitization are sparse. Nor has the concept been linked to exemplification through empirical research prior to this study. However, based on the conceptual propositions within the theories, we make a prediction that exemplification has a potential to increase the perception of securitization. Vultee (2010) and Vultee et al. (2015) conducted exploratory experiments that showed evidence that securitization is a form of a framing process. Thus, particular media depictions trigger an effect in audience that corresponds to a sense of securitization. A heuristic type of process that prompts a cognitive shortcut through an intense emotional reaction such as exemplification may contribute to securitization, specifically in securitization's key conceptualization as a threat which endangers a collective unit. For example, health matters such as obesity (Voss et al., 2019) or societal matters such as immigration (e.g., Moreno and Price, 2017) are discussed within the U.S. context in terms of security, implying national security as well as security as the deeper commitments and responsibilities of the nation-state to act in order to protect those who likely are in danger.

H2: Exemplars of both valences (positive and negative) will increase the perception of securitization of the issues.

We also inquire about the possibility of positive exemplars in news inviting different securitized effects than neutral news or negative exemplar news. Vultee et al. (2015) demonstrated that securitizing effects are conditional upon varying frames and features of news stories, so different conditions appear to impact the success of securitization in audience's perception. Valence of exemplification may represent a type of condition that impacts the results. Also, specific contexts can simultaneously be related to several highly relevant aspects of collective identity and security. For example, immigration can be perceived as a core national value that is deserving of securitized protection such as the “American dream” (Sowards and Pineda, 2013), or as a serious criminal or terrorist peril to the physical safety and the freedoms of the citizens (Hameleers, 2019; Riles et al., 2020). Hence:

RQ2: How will the perceptions of securitization differ as a result of exposure to neutral, positive, and negative exemplars?

It is worthwhile to consider a moderating relationship that stigma could play for the consequent outcome toward securitization. There can be multiple simultaneous definitions of the collective identity, for instance a nation as a state vs. a nation as a sociocultural unit. Also, multiple threats can simultaneously represent danger. So at different times, different concerns are prioritized which leads to a more or less intense securitization (Stoycheff et al., 2017). Stigma, which is likely evoked by negative exemplification, can be examined as the possible key predictor of decreased securitization. It is conceivable that if an issue is framed in such way that summons stigma, a normatively preferable securitization is not likely to happen in the perceptions of the public. For example, when those who are victimized within the context are stigmatized, they are deprived of not just sympathy or compassion but also stripped of consideration that perhaps it is a broader public interest to mitigate the situation and assist the impacted individuals. Furthermore, stigmatization is in many cases linked to perceiving the stigmatized as the actual peril in terms of physical or sociocultural threat to a collective unit (Riles et al., 2020), so stigmatization would then be antithetical to the normatively preferable securitization as examined here. Thus, with the next research question, we explore whether stigmatization functions as a potential negative predictor of securitizing effect.

RQ3: Is there an evidence of stigmatizing effect being a negatively-related predictor of securitizing effect?

News quality has been considered within a plethora of mass communication studies, and is generally treated as independent variable (e.g., Van der Wurff et al., 2018) or as a perceived dependent variable (e.g., Mothes, 2017). Urban and Schweiger (2014) point out that audiences experience some difficulties in making judgements about the level of news quality as related to objectivity and ethics-related dimensions. Then in order to make such judgements, audiences use heuristics such as the brand of the source. Possibly, then, exemplification may serve as a heuristic which, by evoking a sense of familiarity, invites certain judgements about news quality. We suspect positive exemplification may perform better:

H3: Valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on the quality of news.

Agenda-setting and framing capacities of news have been documented by a robust body of relevant effects literature (Scheufele, 2000; Graber, 2010; Luo et al., 2019). The sense of familiarity, which is emphasized by exemplification, is likely to contribute to an enhanced agenda setting effect, while valence might invite further impact on the perceived interest that the story can generate according to the audience members. Here, both valences of exemplification are likely to outperform neutral news, but positive exemplification has a potential to outperform negative exemplification as an indicator of an issue that ought to matter to a collective unit:

H4: Valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on the general interest of the covered issue.

Next, we exploratorily investigate a possibility of a stigmatizing effect as well as a securitizing effect functioning as confounding variables toward forming further perceptions as explored in the H3 and H4:

RQ4a: Is there an evidence of stigmatizing effect and/or securitizing effect being related to perceptions on the quality of news?

RQ4b: Is there an evidence of stigmatizing effect and/or securitizing effect being related to perceptions on the general interest of the covered issue?

Lastly, we address the impacts of the other possible independent and/or confounding variables that may play a role in the way the above hypothesized dependent attitudes and perceptions form. For instance, Puhl et al. (2013) found that certain intersectional contextual factors of a news story have an impact on the stigmatizing effects. Furthermore, Vultee (2010) found that the political attitude has a connection to securitization-related attitudes. We ask:

RQ5a: Are there any interaction and/or main effects of the context of the story on the stigmatizing and/or securitizing effects?

RQ5b: Are there any interaction and/or main effects of the political leanings of the research subjects on the stigmatizing and/or securitizing effects?

We tested exemplification's effects using three conditions: positive, negative, and non-exemplar news stories—two valences of exemplification and a control condition. We designed three stories per condition, each with a different context. One focused on artificial limbs, one focused on immigrant stories, and one focused on obesity. Story focus was selected for its potential to represent, through the use of exemplars, content that could have a stigmatizing or securitizing effect. For example, previous research has demonstrated that characteristics of immigrant groups are often strongly linked to national debates about unauthorized immigration (e.g., Timberlake and Williams, 2012), people who use prosthetics may be seen as less competent than able-bodied individuals (e.g., Coleman et al., 2015), or that, from childhood through adulthood, people often negatively stereotype obese individuals (e.g., Klaczynski et al., 2009). In order to account for ecological validity, all stories were closely inspired by existing news stories. Stories were selected for their emotionally evocative narratives for the positive and negative exemplar condition (e.g., Zillmann, 2006; Sellnow and Sellnow, 2014; Spence et al., 2016; Sellnow-Richmond et al., 2018), and the absence of this, with an emphasis on base rate information, for the neutral condition (e.g., Zillmann, 2006; Spence et al., 2016). Each story was accompanied by a representative photo or graph. Each story features a unique narrative that hinges on the use of positive exemplification, negative exemplification, or that omits prominent features of exemplification. We provide the headline and first sentence for each story in Table 1 in order to demonstrate the ways in which each story was designed to replicate the exemplification found in real world news stories. In order to ensure that the stimuli accurately represented exemplification and the intended valence, we utilized two manipulation checks—we first solicited feedback from exemplification and media effects expert scholars, and subsequently exposed a small sample of participants to the entire stimulus across all conditions, and asked closed-ended Likert scale questions after each story to ensure the presence or absence of exemplification as well as the valence in each story. The results of the latter manipulation check are reported in the results.

To achieve an initial manipulation check, we contacted two strategic communication researchers who have previously worked on exemplification theory to review the stimulus material. We revised it according to their feedback. We want to mention that exposing subjects to three different contexts allows us to do both between-the-subjects and within-the-subjects tests. In contemporary news media studies, it is customary to utilize various contexts to mitigate impact of extraneous variables, such as one particular context which may reflect a particular bias among study subjects. Furthermore, to assess this possible broader-scale confounding variable effect of the context as inquired in the RQ5, we employed the story context as an independent nominal variable.

The RQ5 also inquiries about a possible confounding effect of political leaning. Our post-experiment questionnaire asks a question on political preference, with the possible responses on 7-point scale with 1 corresponding to very conservative, 4-neutral, and 7-very liberal. When later examining these data, we have noticed a relatively equivalent size groups along conservative scale values (1–3), neutral (value 4), and liberal values (5–7). So the independent variable of political leaning has been recoded into the four corresponding nominal groups of liberal, neutral, conservative, and not-reporting.

We developed an instrument to compose measures for all following outcome variables. The items were each measured as closed-ended statements with the options of 7-point Likert-type scale for a response. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to verify correlation between the items that were envisioned as corresponding to particular variables. The intended items that did not correlate as measures of one concept were excluded from the aggregate quantities toward the outcome variables. The SPSS software was employed to perform PCA with the collected data, with the analysis (Varimax with Kaiser Normalization) yielding specifically four component factors that reflected the core constructs of the envisioned target variables (with a significant KMO & Bartlett's test at the value of 0.801, p < 0.001). This variable-building method was appropriate in this study because, while the stigma-related items were derived from previously established stigma scales (Kassam et al., 2012), the limited quantitative research on securitization means we could not simply appropriate the items from Vultee (2010) and Vultee et al. (2015), as these researchers primarily operationalized urgency and neutral-to-negative incarnation of securitization (by juxtaposing it to liberty). However, we operationalized the items of normatively neutral-to-preferable articulation of securitization (Floyd, 2011, 2019a,b; Austin and Beaulieu-Brossard, 2017; Sahu, 2019) to convey a sense of collective unit (items 3 and 5 as listed in the paragraph below), a sense of threat (item 4), and employment of mitigation measures through the nation-state authority and resources (items 1 and 2). Lastly, on perceived quality of news and perceived evaluation of the general interest of the story, we were interested in conscious perceptions, not the particularly latent or subconscious attitudes. Hence, the last two sets of items were based on the research-team's agreement upon the face validity of the captured concepts.

Based on the PCA, stigmatization variable is composed of following items;

(1) I struggle to/do not feel compassion for a person… (0.780).

(2) More than half of people with… did not try hard enough to avoid their outcome (0.840).

(3) I have negative reactions toward people with… (0.794).

(4) People who rely on government funds for … lack the self-discipline to take care of themselves (0.859).

Securitization variable is composed of:

(1) The best way to address need for … is through government sponsored intervention (0.626).

(2) Public funding should be used to support development of… (0.613).

(3) Supporting advances in… is good for the country (0.605).

(4) Wrong policy on… represents a serious danger to the citizens of the US (0.596).

(5) It is a part of core values of the US to help and assist people with… (0.588).

Perception of news quality variable is composed of:

(1) The news article is fair (0.882).

(2) The news article is reasonable (0.900).

(3) The news article is informative (0.696).

Perception of general interest of the issue variable is composed by adding these items:

(1) The news article is interesting for general and broad audience (−0.783).

(2) The news article is only interesting for a narrow and specific audience (0.872).

Each variable was crafted by adding the corresponding items and dividing the value by the number of added items, yielding 1 through 7 scales, where 1 corresponds to the lowest possible value of the variable and 7 to the highest, so the final composite measure reflects the original Likert-inspired approach and represents user-friendliness in interpretation. We concluded that sum-scoring is appropriate as the items represent initial construct face validity. The items reflect theoretical articulations of the constructs of interest; furthermore, just the items with high correlation coefficient in relationship to other items were considered and other tested items were rejected. We believe the sum score approach retains fidelity to the conceptual essence of the variables of interest (McNeish and Wolf, 2020).

Story content was selected to reflect the contexts and stories that are often presented with exemplars and that can have a securitizing or stigmatizing effect. A sample of a first-year student population was used because they are often passive news consumers (Meyer et al., 2016). The relative homogeneity of the student sample with respect to characteristics such as age and related frame of reference allows us to narrow the focus down on the bivariate relationships between the tested variables (Basil et al., 2002). We focused on relationships between conditions—the goal of the study—rather than across all population targets, as “packing so many sources of variation into a single experimental study is rarely practical and will almost certainly conflict with the goals of the study” (Shadish et al., 2002). It was also important to account for threats to internal validity. History was controlled in this study by selecting a group from the same general location and scheduling their testing in the same 1-month time period. We reduced maturation threats by selecting participants of roughly the same age and, again, from the same location so that local secular trends did not affect them.

The sample is comprised of ~46% women, 44% men, and 9% other or unidentified. Sixty-one percentage of respondents identified as White/Caucasian, 17% as Black, African-American, 9% as Hispanic/Latinx, and 3% as Mixed Race, while ~10%.did not disclose their race/ethnic background. The average age is 19, with range 18–30. Among those who disclosed political preferences, 36.3% identify as moderate or neither liberal nor conservative. 30.2% identify along the conservative spectrum. 33.5% identify along the liberal spectrum. An important behavioral tendency that the subjects reported is that ~9% consume news more than 1 h per day, ~49% consume news between 15 min and 1 h, and 41% consume < 15 min per day, and as the mode is under an hour of consumption this tendency reflects to a degree some trends reported for average Americans who consume news ~57 min per day (Pew Research Center, 2010).

With experimental design, larger sample sizes than few hundred participants are difficult to achieve due to many practical confines. In order to keep transparency that stems from limitations of sample size in experiments, it is paramount to report effect size (Yigit and Mendes, 2018), so we include partial eta squared with our analyses. Furthermore, our sample size and repeated measures allowed for robust n per each of the groups as determined by analyzed combination of variables in ANOVA. The only specific group that had a number lower than recommended 15–20 corresponded to participants reporting as having conservative political leanings in neutral exemplification condition per story context, specifically n = 14. We could not address this limitation as this is naturally occurring variable, so there simply was not more participants with this reported characterization. Such underrepresentation may lead to type II error or “false negative.” While political leaning is a variable that was examined in our tests, and that showed significance in some tests, there is a possibility that significant difference was not detected in other instances while it may play a role in actuality.

The Institutional Review Board approval was granted August 2019. The experimental data collection took place between September 2019 and December 2019. The students in the university's general education requirement course were awarded a small amount of extra credit as an incentive for participation. Students were first presented with informed consent. Then, the consenting research subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three possible conditions. Each condition represented one of the possible valences of exemplification, so each subject was exposed to three different stories with the particular valence. The stories presented to participants in each condition began with a story about artificial limbs, followed by a story about immigration, and ended with a story about obesity. Because we were looking at differences across exemplification valence, we ensured that each participant was only presented with one valence. The unique contexts for each condition should not have impacted participant perspectives on the others. This approach allowed to control for a possible bias due to a particular story or a particular context through within-the-subject comparison. Between-the-subjects comparison further enables testing of the impacts of manipulation of the central independent variable of exemplification. While an experiment of this nature is inherently contrived, news stories in this study were taken from existing news publications and edited minimally to maintain as much authenticity as possible. After reading each of the stories, the subjects filled out the questionnaire monitoring outcome variables. After completing the experimental part, the subjects filled out the questionnaire regarding demographics and political leaning. Lastly, they were thanked and invited to follow up at any point they wish to inquire about the study (see Table 3).

As the initial manipulation check was performed based on expert input to manipulate the independent variable of exemplification and adding a variety of contexts, additional manipulations check was later performed with a separate group of undergraduate students (n = 25) to avoid a threat of manipulation check questions acting as a confounding variable and thus swaying results of the experimental sample (Hauser et al., 2018). The manipulation check specific subjects were exposed to the entire stimulus across all conditions featuring all nine stories and asked a set of closed-ended questions after each story with a set of 7-point Likert scale responses. The manipulation of achieving exemplification in the particular stories was measured by the item “This story clearly shows me an example of a person who is…(options were depending on the context of the story: obese; an immigrant; an amputee)”, and as the results of correlated samples t-test statistic show, the subjects considered both positively exemplified [t(74) = 8.73, p < 0.0001 one-tailed] and negatively exemplified stories [t(74) = 7.41, p < 0.0001 one-tailed] as featuring exemplification as opposed to neutral stories which did not. To test the achievement of positive valence of exemplification, the item stated “This article is a good example of a positive story about…”, and it resulted in a highly significant difference [t(74) = 10.10, p < 0.0001 one-tailed]. The negative valence of exemplification was tested by the item stating “This article shows problems with people who are…”, and it also resulted in a significant difference further confirming successful manipulation [t(74) = −6.44, p < 0.0001 one-tailed].

Randomization of the condition assignment should also lead to a rather normal variance in collected data across conditions. Homogeneity of variance was checked by performing Levene's test prior to each analysis of variance, and as these have yielded heteroscedasticity for stigmatization (F = 2.74, p < 0.00) and homoscedasticity for securitization (F = 1.26, p = 0.15), perception on the quality of the news (F = 1.28, p = 0.13), and general interest variables (F = 1.12, p = 0.29), the fitting statistical tests were pursued to explore hypotheses. In addition, the tendencies and distributions of demographic characteristics of subjects across conditions were verified across the three experimental groups and as the tests revealed, the groups did not reflect any significant differences in terms of age [F(2) = 0.08, p = 0.92], gender [ = 3.94, p = 0.13], nor political preference [F(2) = 0.65, p = 0.52]. The tests revealed that there was an inequivalence of the demographic characteristic of race [ = 19.15, p < 0.0001] and the behavioral tendency of amount of news consumption [F(2) = 5.16, p = 0.006] distributions across the conditions. The possible intervening or confounding effects of these two variables were thus closely monitored and in case of race show to have no significant main or interaction effects on any of the tested outcome variables. In case of amount of news consumption, main and interaction effects were only detected with the outcome variable of stigmatization, but no other outcome variables, and hence the specific role of the amount of news consumption in connection to stigmatization is reflected on further in this section.

The Hypothesis 1 presupposes positive exemplars will decrease the stigmatization of impacted individuals. Analysis of Variance, ANOVA, was performed on SPSS software to test the hypothesis, showing support for it F(2, 709) = 16.118, p < 0.001. The previously addressed heteroscedasticity of the variance of the variable requires running additional robust tests of equality of means, which yielded statistically significant results, particularly Welch's [F(2, 463) = 13.789, p < 0.001] and Brown-Forsythe's [F(2, 689) = 14.990, p < 0.001] statistics. Hence, we accept the H1 according to our data. The Research Question 1 aims to specify how stigmatizing effects differs as a result of exposure to neutral, positive, and negative exemplars. The examination of means shows that positive exemplars are leading to lesser stigmatization in comparison to both the negative exemplar condition and the control condition with a neutral story (see Table 2 for additional results such as Means, Standard Deviations, and Partial Eta Squared measures of effect sizes).

Table 3. Main and interaction effects of independent variables on the outcomes of stigmatization and securitization.

The H2 proposes exemplars of both valences (positive and negative) will increase the perception of securitization of the issues. Further, the RQ2 asks how will the perceptions of securitization differ as a result of exposure to neutral, positive, and negative exemplars. The results of ANOVA point out, not a mere presence of exemplification but the valence of exemplification matters. Particularly, positive exemplification is associated with significantly higher securitization; F(2, 702) = 4.616, p = 0.010, so the H2 is only supported about positive exemplars and rejected about negative exemplars, which are associated with lower degree of securitization than the neutral stories (see Table 2).

The Research Question 3 inquires whether stigmatizing effect of exemplification might function also as a negative predictor of securitizing effect. Pearson's r correlation test was performed using SPSS software to explore the possible relationship between the variables. Highly significant negative correlation of moderate strength was detected; r = −0.392, p < 0.000. This shows an evidence that as stigmatized impressions increase, securitization decreases and vice-versa. The correlation presence is an evidence there is some linkage, however we cannot irrefutably determine time-order at this point, while the logic that was informing the RQ3 is based on speculation that stigmatization is more emotionally-driven subconscious process, while securitization requires more deliberate contemplation such as investment of public resources and thus it possibly more delayed.

The Hypothesis 3 claims that valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on the quality of news. Significant difference was detected through ANOVA, F(2, 712) = 14.522, p < 0.001. Hence, H3 is supported by the present data. Positive exemplars are interpreted as possessing higher news quality than neutral stories. Negative exemplars were perceived as having lower news quality than other two conditions (see Table 1).

The Hypothesis 4 claims that valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on the general interest of the issue. ANOVA was applied to test the possible significance of the difference. Significant difference was detected, F(2, 711) = 10.310, p < 0.001. Therefore, H4 is also supported by the data. As the means show, the perceptions on general interest of the issues are highest when exposed to positive exemplars, and lowest in control condition with no pronounced exemplar (see Table 1).

The Research Question 4a inquires whether stigmatizing effect and/or securitizing effect of exemplification relates to perceptions on the quality of news. There is not an evidence of substantial correlation, as the Pearson's r correlation test shows very low coefficients of relationship; stigmatization r = −0.169, p < 0.001; securitization r = 0.267, p < 0.001. The RQ4b asks if stigmatizing effect and/or securitizing effect of exemplification relates to perceptions on the general interest of the issue. Similarly, Pearson's r correlation test shows very low coefficients of relationship, which does not warrant the notion of robust relationships; stigmatization r = −0.211, p < 0.001; securitization r = 0.126, p = 0.001. This result would also suggest that perceived interest of the issue is not a particularly promising predictor of normatively preferable securitization as we have initially speculated based on the theory. So the impact of exemplification on perceived quality of news and perceived importance of the issue is possibly only very minimally moderated by intervening presence (or lack there) of stigmatizing and securitizing effects.

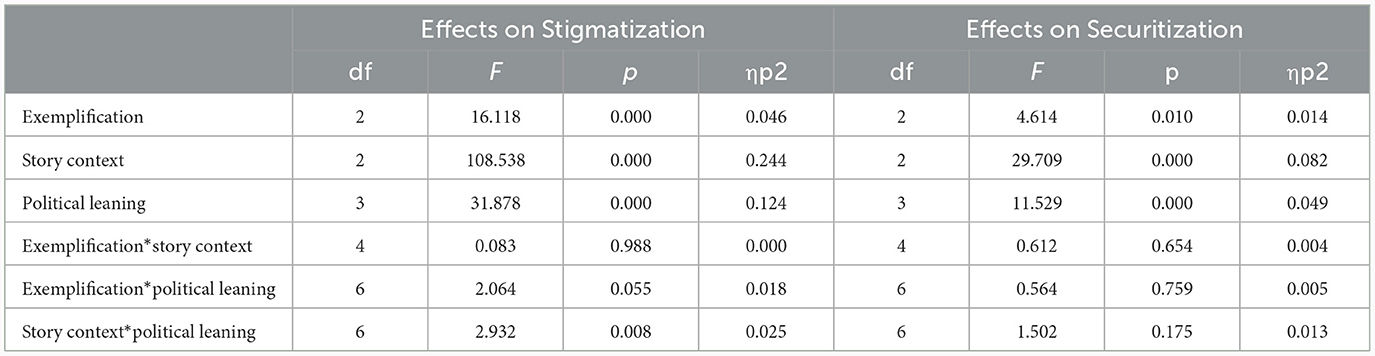

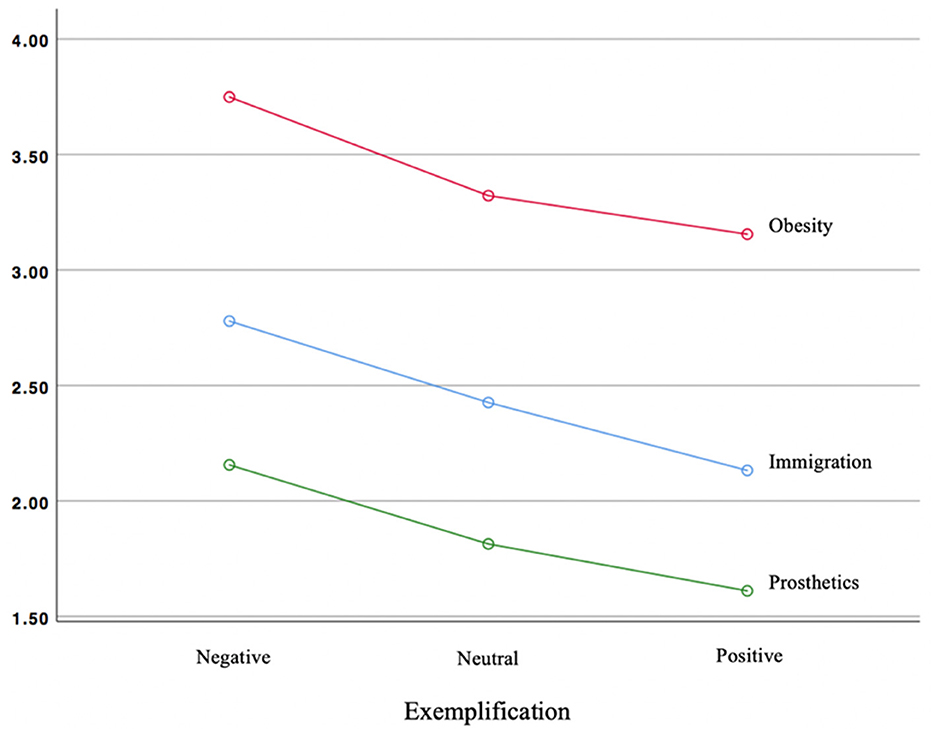

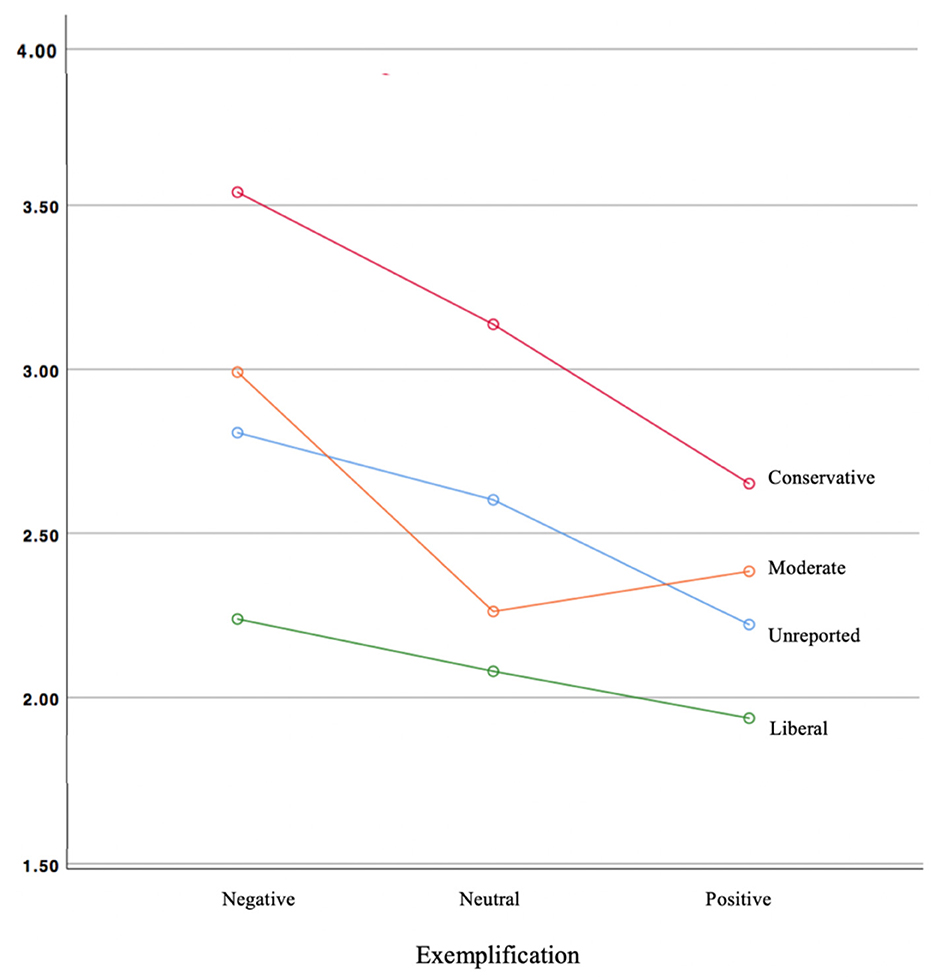

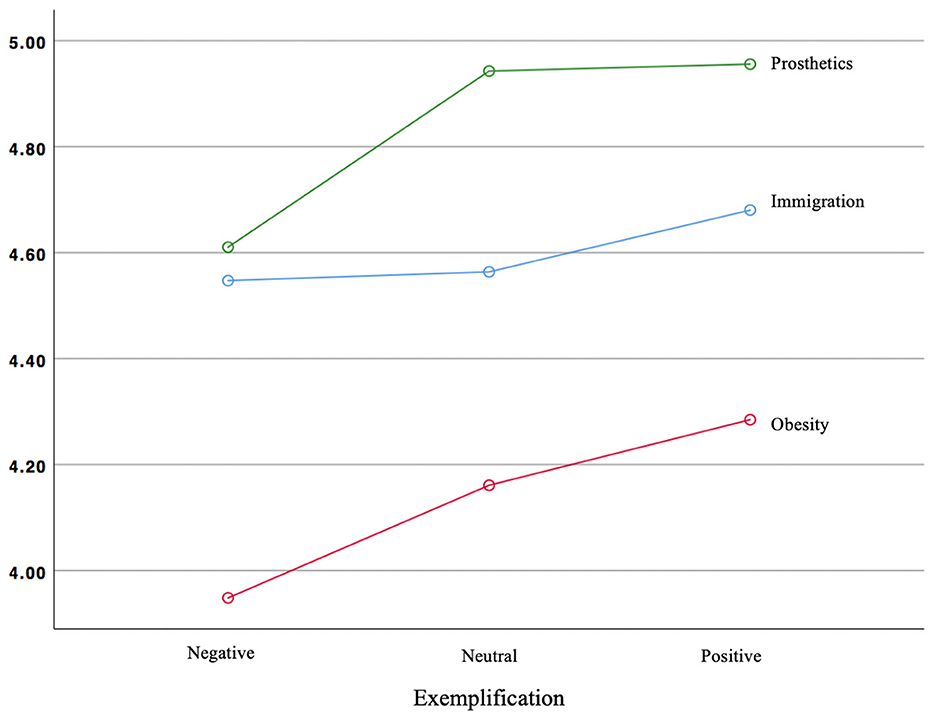

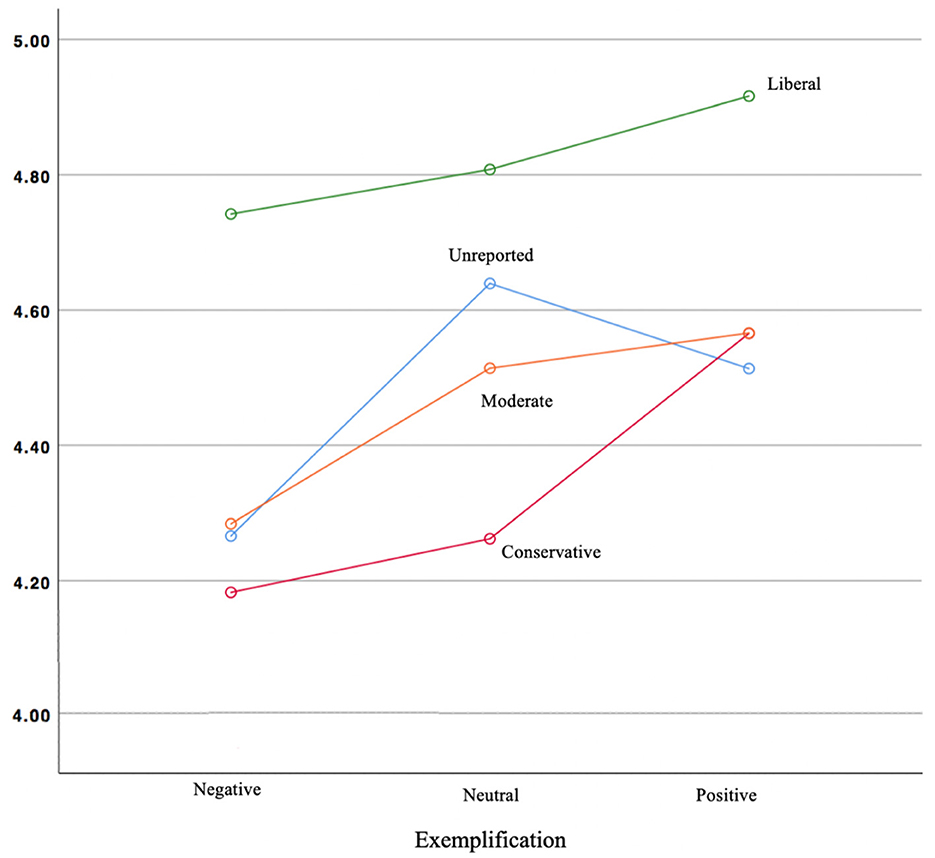

Lastly, the set of Research Questions 5 inquire: RQ5a: Are there any interaction and/or main effects of the context of the story on the stigmatizing and/or securitizing effects?; RQ5b: Are there any interaction and/or main effects of the political leanings of the research subjects on the stigmatizing and/or securitizing effects? While a clear statistical impact was demonstrated linking the key constructs of interest, according to Partial Eta Squared measure, the main effect of exemplification accounts for ~5% of variation for stigmatization effect and ~1% of variation for securitization. This is not a dismissible effect size, granted is has been detected after an exposure to just one exemplified news story on a particular topic. When further exploring the effects of the context of the story, there was a clear main effect on all the key explored variables; for stigmatization it explains ~24% of variation [F(2, 709) = 108.538, p < 0.001]; and ~8% of variation for securitization [F(2, 702) = 29.709, p < 0.001]. Further, political leaning of the research subjects also shows main effect on all key outcome variables; explaining ~12% of variation for stigmatization [F(3, 709) = 31.878, p < 0.001]; and ~5% of variation for securitization [F(3, 702) = 11.529, p < 0.001]. See Table 2 for additional details of the main effects and interaction effects report.

Even after an exposure to just one exemplified news story on the topic, both stigmatization and securitization get activated to a degree. It shows the phenomena are importantly connected if the impact is demonstrated even without any, let alone substantial, accumulation. The context of the story and political leaning are explaining a larger portion of the variation. This is understandable as political leaning represents a long-term accumulation of understandings and tendencies. Similarly, the context of the story represents a somewhat substantial layer of previously accumulated assumptions. As for instance, the context of obesity and immigration are likely to be more salient for the majority of the American public than amputation and prosthetic limbs. Thus, as our results show, the effects are more intense for the context of prosthetics which is very possibly due to this topic being more of a “tabula rasa” and thus susceptible to be impacted by media messages without preconceptions (see Figures 1–4). So, these results are showing an importance of confounding variables, which is very pronounced in context that is selected for empirical analyses, so if only one case is utilized as the experimental context, it may render too limited or too exaggerated outcomes and thus skew the research findings and impair external validity and broader generalizability.

Figure 1. Effects of exemplification and story context on stigmatization. The utilized scale ranges from 1 to 7.

Figure 2. Effects of exemplification and political leaning on stigmatization. The utilized scale ranges from 1 to 7.

Figure 3. Effects of exemplification and story context on securitization. The utilized scale ranges from 1 to 7.

Figure 4. Effects of exemplification and political leaning on securitization. The utilized scale ranges from 1 to 7.

The results of this study indicate that as stigmatized impressions increase, securitization decreases. This indicates that the more stigmatizing the content presented, the less likely individuals are to report securitizing beliefs. Still, we cannot definitively make claims about time-order based on these results but the demonstrated connection serves as an evidence worth of further exploration.

Results of this study supported the hypothesis that valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on the quality of news. Specifically, positive exemplars were perceived by study respondents as being of higher news quality than neutral stories. This suggests that the positive emotional response might contribute to participant engagement with the story. This is consistent with previous research that suggests that the ability to elicit an emotional response in audiences prolongs their engagement (e.g., Spence et al., 2016). The finding also aligns with Frederickson's (2001, 2004) notion that positive emotions have the capacity to broaden attention and thinking and undo some negative emotional impacts. Moreover, the stories with negative exemplars were perceived be study participants as being of lower news quality than the other two conditions. This is an interesting finding in the context of sensationalized journalism, which often highlights negative exemplars as a means of capturing reader attention.

Results of this study also supported claims that valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on the general interest of the issue. However, perceptions of general interest were highest in the positive exemplar condition and lowest in the control condition where no exemplar was present. This indicates that the use of exemplars in news stories does increase readers' perception that the content is important. Again, it is interesting that the positive exemplar condition demonstrated the highest effectiveness in this regard.

Results of this study did not indicate that a stigmatizing effect of exemplification is related to perceptions of the quality of news. Similarly, there was no relationship between the stigmatizing effect of exemplification and perceptions of the general interest of the issue. Therefore, when stigmatization is present in media messages, it does not necessarily increase the perceived interest of the issue to readers, nor does it impact their perception of news quality. However, previous research does indicate that stigmatization in media messages can be harmful for individuals who share those stigmatized identities (e.g., names removed to protect the integrity of the review process, 2020; Wang, 1992; Guttman and Salmon, 2004). This finding indicates that stigmatization should be actively avoided in media messages, as there is no positive outcome of these messages, but certain negative outcomes. Moreover, when using exemplification in messages, it is important to consider the ethics of negative exemplars broadly to assess them for any unintended stigmatization that would result.

The results of this study offer several practical implications. First, early results indicate that negative exemplars can have a stigmatizing effect on messages' receivers. While negative exemplars may be effective persuasive tools, the stigmatizing effect may pose additional social issues, specifically in the area of mental health. As such, it is important to think comprehensively about the end result of media messages and avoid communication that can be harmful. For example, coverage of individuals with long term, physically visible effects of a COVID-19 infection (e.g., tracheotomy) should minimize fault on the individual for avoiding mitigation such as masking and vaccination, which could promote stigmatization toward individuals with such physical markers.

Second, in news messages, positive exemplars were more likely than negative exemplars and the control group to be perceived as higher news quality. This indicates that it may be worthwhile for messages creators to consider positive exemplars in place of the more problematic negative exemplars in efforts to elicit interest in their content. For example, in the illustration from the previous paragraph, stories might instead emphasize the more positive role of recovery and advancements in medicine and the heroic efforts of healthcare workers. Still, more work should be done to determine the extent to which these do hold the attention of audiences to the same degree as negative exemplars, as news quality cannot be equated with engagement. Surely, the rapid spread of mis- and disinformation articles is demonstrative of this.

Third, in news messages, perceptions of general interest were highest in the positive exemplar condition and lowest in the control condition where no exemplar was present. This may be more indicative of the role of positive and negative exemplars in capturing audience attention. This further supports the notion that positive exemplars ought to be utilized in place of negative exemplars as a means of capturing audience attention without carrying with them the stigmatizing effects of negative exemplars. Again, general interest is not a direct measure of audience engagement, but does indicate that audience found the content to be of note. Practically, news stories often cover climate change using negative exemplars. This finding suggests that this could be more engaging than covering the topic without exemplars, but suggests that perhaps including more optimistic exemplars, such as organizations that have dramatically reduced carbon emissions and the projected positive impacts of policies to support this for the long-term health of the planet could be equally engaging and less likely to lose interest from readers who find negative climate change coverage fear-inducing and dreadful. Rather, positively illustrating what individuals may be able to contribute to minimize negative effects through the use of positive exemplars may cultivate a sense of agency, similar to findings presented in Sellnow-Richmond et al.'s (2018) work.

This study was not without its limitations. First, this study sampled a select segment of the population, utilizing a homogeneous sample of first-year university students. This decision was made intentionally, to avoid variance in life experience that would serve as an unintentional mediating factor in the results. However, expanding the sample in future studies would help distinguish exemplification effects across more varied publics. Also, replications of the study with samples including more age diversity will allow for establishing how generalizable those results are for a wider population. We acknowledge that the subject sample is not absolutely representative of the broader U.S. population. However, a student sample was used as an appropriate starting point to determine possible relationships between variables (Basil et al., 2002). Additional variable combinations would shed additional light into impacts of factors such as perceived news credibility or specific characteristics of news stories.

Second, while the stories used in this study were all based upon existing news content, there are limits in terms of the extent to which exposing respondents to hand-selected news content can effectively mirror real world news consumption. Future studies should work to triangulate these findings through additional means of assessing positive vs. negative exemplars in news messages. Third, while these results do indicate that positive exemplars improve perceptions of news quality and interest, they do not directly contribute to our understandings of how long-lasting these effects will be. Research on the use of negative exemplars has indicated that these are emotionally evocative and persuasive message that are also easily retrieved by receivers after exposure. These findings do not inform about how long these messages will remain accessible in readers' minds. This is an additional empirical question that future research can seek to address.

The aim of this study was to further test exemplification theory and to expand the understanding of exemplification messages in news stories. Specifically, this study examined the role of positive vs. negative exemplars and the extent to which stigmatization, which is associated with negative exemplars interacts with other outcome variables. Results of the study supported the propositions that valence of exemplification predicts perceptions on both the general interest of the issue and news quality. Positive exemplars were perceived most positively by respondents on both. Coupled with previously reported strongly significant evidence that negative exemplification leads to a stigmatizing effect and that positive exemplification significantly predicts a higher securitizing effect, news message creators ought to consider replacing negative exemplars with positive ones in their news content.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

DS-R: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS-R: Conceptualization, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aust, C. F., and Zillmann, D. (1996). Effects of victim exemplification in television news on viewer perception of social issues. J. Mass Commun. Q. 73, 787–803. doi: 10.1177/107769909607300403

Austin, J. L., and Beaulieu-Brossard, P. (2017). (De)securitization dilemmas: theorizing the simultaneous enaction of securitization and desecuritization. Rev. Int. Stud. 44, 301–323. doi: 10.1017/S0260210517000511

Baele, S. J., and Thomson, C. O. (2017). An experimental agenda for securitization theory. Int. Stud. Rev. 19, 646–666. doi: 10.1093/isr/vix014

Basil, M. D., Brown, W. J., and Bocarnea, M. C. (2002). Differences in univariate values versus multivariate relationships. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 501–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00820.x

Buzan, B., Waever, O., and de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Pub.

Coleman, J. M., Brunnell, A. B., and Haugen, I. M. (2015). Multiple forms of prejudice: how gender and disability stereotypes influence judgments of disabled women and men. Curr. Psychol. 24, 177–189. doi: 10.1007/s12144-014-9250-5

Dardis, F. (2007). The role of issue-framing functions in affecting beliefs and opinions about a sociopolitical issue. Commun. Q. 55, 247–265. doi: 10.1080/01463370701290525

Eagly, A. E., and Chaiken, S. (1993). “Chapter seven: process theories of attitude formation and change: the elaboration likelihood and heuristic-systematic models,” in The Psychology of Attitudes, eds A. E. Eagly, and S. Chaiken (Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers), 305–349.

Floyd, R. (2011). Can securitization theory be used in normative analysis? Towards a just securitization theory. Sec. Dialog. 42, 427–439. doi: 10.1177/0967010611418712

Floyd, R. (2019a). States, last resort, and the obligation to securitize. Polity 51, 378–394. doi: 10.1086/701886

Floyd, R. (2019b). Collective securitization in the EU: normative dimensions. West. Eur. Polit. 42, 391–412. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1510200

Frederickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Frederickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Transact. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 359, 1367–1377. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Galemba, R., Dingeman, K., DeVries, K., and Servin, Y. (2019). Paradoxes of protection: compassionate repression at the mexico-guatemala border. J. Migr. Hum. Sec. 7, 62–78. doi: 10.1177/2331502419862239

Guttman, N., and Salmon, C. T. (2004). Guilt, fear, stigma and knowledge gaps: ethical issues in public health communication interventions. Bioethics 18, 531–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2004.00415.x

Gwarjanski, A. R., and Parrott, S. (2018). Schizophrenia in the news: the role of news frames in shaping online reader dialogue about mental illness. Health Commun. 33, 954–961. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1323320

Hameleers, M. (2019). Putting our own people first: the content and effects of online right-wing populist discourse surrounding the European refugee crisis. Mass Commun. Soc. 22, 804–826. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2019.1655768

Hashim, I. (2023). Analyzing crisis communication in media and research: exploring approaches of agenda setting, framing, and exemplification. J. Res. Administr. 5, 3853–3861.

Hauser, D. J., Ellsworth, P. C., and Gonzales, R. (2018). Are manipulation checks necessary? Front. Psychol. 9:998. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00998

Jarlenski, M., and Barry, C. (2013). News media coverage of trans fat: health risks and policy responses. Health Commun. 28, 209–216. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.669670

Kassam, A., Papish, A., Modgill, G., and Patten, S. (2012). The development and psychometric properties of a new scale to measure mental illness related stigma by health care providers: the opening minds scale for health care providers. BMC Psychol. 12:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-62

Kim, S., Carvalho, J. P., Davis, A. G., and Mullins, A. M. (2011). The view of the border: news framing of the definition, causes, and solutions to illegal immigration. Mass Commun. Soc. 14, 292–314. doi: 10.1080/15205431003743679

Klaczynski, P., Daniel, D. B., and Keller, P. S. (2009). Appearance idealization, body esteem, causal attributions, and ethnic variations in the development of obesity stereotypes. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 30, 537–551. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.031

Kramer, B., and Peter, C. (2020). Exemplification effects: a meta-analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 46, 192–221. doi: 10.1093/hcr/hqz024

Li, M. (2023). Exemplifying power matters: the impact of power exemplification of transgender people in the news on issue attribution, dehumanization, and aggression tendencies. J. Pract. 17, 525–553. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2021.1930104

Luo, Y., Burley, H., Moe, A., and Sui, M. (2019). A meta-analysis of news media's public agenda-setting effects, 1972 – 2015. J. Mass Commun. Q. 96, 150–172. doi: 10.1177/1077699018804500

McCarthy, A. (2020). Covid-19 and the Limits of Law. National Review. Available online at: https://www.nationalreview.com/2020/03/coronavirus-response-executive-power-limits-of-law/ (accessed January 30, 2024).

McNeish, D., and Wolf, M. G. (2020). Thinking twice about sum scores. Behav. Res. Methods 52, 2287–2305. doi: 10.3758/s13428-020-01398-0

Meyer, H. K., Speakman, B., and Garud, N. (2016). Exploring news media consumption habits among college students and their influence on traditional student media. J. Coll. Media Assoc. 54, 1–24.

Moreno, K., and Price, B. E. (2017). The social and political impact of the new (private) National Security: private actors in the securitization of immigration in the U.S. post 9/11. Crime Law Soc. Change 67, 353–376. doi: 10.1007/s10611-016-9655-1

Mothes, C. (2017). Biased objectivity: an experiment on information preferences of journalists and citizens. J. Mass Commun. Q. 94, 1073–1095. doi: 10.1177/1077699016669106

Pew Research Center (2010). Americans Spending More Time Following the News. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2010/09/12/americans-spending-more-time-following-the-news/ (accessed January 30, 2024).

Puhl, R., Luedicke, J., and Heuer, C. (2013). The stigmatizing effect of visual media portrayals of obese persons on public attitudes: does race or gender matter? J. Health Commun. 18, 805–826. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.757393

Quinsaat, S. (2014). Competing news frames and hegemonic discourses in the construction of contemporary immigration and immigrants in the United States. Mass Commun. Soc. 17, 573–596. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2013.816742

Ren, C., and Lei, M. (2020). Positive portrayals of ‘living with HIV' to reduce HIV stigma: do they work in reality? J. Appl. Commun. Res. 48, 496–514. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2020.1789688

Riles, J. M., Behm-Morawitz, E., Shin, H., and Funk, M. (2020). The effect of news peril-type on social inclinations: a social group comparison. J. Mass Commun. Q. 97, 721–742. doi: 10.1177/1077699019855633

Sahu, A. K. (2019). The democratic securitization of climate change in India. Asian Polit. Policy 11, 438–460. doi: 10.1111/aspp.12481

Sarge, M. A., and Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2013). Impacts of efficacy and exemplification in an online message about weight loss on weight management self-efficacy, satisfaction, and personal importance. J. Health Commun. Int. Perspect. 18, 827–844. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.757392

Scheufele, D. A. (2000). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing revisited: another look at cognitive effects of political communication. Mass Commun. Soc. 3, 27–316. doi: 10.1207/S15327825MCS0323_07

Schraedley, M. K., Bean, H., Dempsey, S. E., Dutta, M. J., Hunt, K. P., Ivancic, S. R., et al. (2020). Food (in)security communication: a Journal of Applied Communication Research forum addressing current challenges and future possibilities. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 48, 166–185. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2020.1735648

Seckinelgin, H., Bigirumwami, J., and Morris, J. (2010). Securitization of HIV/AIDS in context: gendered vulnerability in Burundi. Sec. Dialog. 41, 515–535. doi: 10.1177/0967010610382110

Sellnow, D. D., and Sellnow, T. L. (2014). The challenge of exemplification in organizational crisis communication. J. Appl. Commun. 98, 53–64. doi: 10.4148/1051-0834.1077

Sellnow-Richmond, D. D., George, A., and Sellnow, D. D. (2018). An IDEA model analysis of instructional risk communication messages in the time of Ebola. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. 1, 135–166. doi: 10.30658/jicrcr.1.1.7

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., and Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Sjostedt, R. (2008). Exploring the construction of threats: the securitization of HIV/AIDS in Russia. Sec. Dialog. 39, 7–29. doi: 10.1177/0967010607086821

Smith, R. A. (2007). Language of the lost: an explication of stigma communication. Commun. Theory 17, 462–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00307.x

Smith, R. A., Zhu, X., and Fink, E. L. (2019). Understanding the effects of stigma messages: danger appraisal and message judgments. Health Commun. 34, 424–436. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1405487

Sowards, S., and Pineda, R. (2013). Immigrant narratives and popular culture in the United States: border spectacle, unmotivated sympathies, and individualized responsibilities. West. J. Commun. 77, 72–91. doi: 10.1080/10570314.2012.693648

Spence, P. R., Lachlan, K. A., Lin, X., Sellnow-Richmond, D. D., and Sellnow, T. L. (2015). The problem with remaining silent: exemplification effects and public image. Commun. Stud. 66, 341–357. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2015.1018445

Spence, P. R., Sellnow-Richmond, D. D., Sellnow, T. L., and Lachlan, K. A. (2016). Social media and corporate reputation during crises: the viability of video-sharing websites for providing counter-messages to traditional broadcast news. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 44, 199–215. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2016.1192289

Stoycheff, E., Wibowo, K. A., Liu, J., and Xu, K. (2017). Online surveillance's effect on support for other extraordinary measures to prevent terrorism. Mass Commun. Soc. 20, 784–799. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2017.1350278

Timberlake, J. M., and Williams, R. H. (2012). Stereotypes of U.S. immigrants from four global regions. Soc. Sci. Q. 93, 867–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00860.x

Tran, H. (2012). Exemplification effects of multimedia enhancements. Media Psychol. 15, 396–419. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2012.723119

Trumbo, C. (2012). The effect of newspaper coverage of influenza on the rate of physician visits for influenza 2002-2008. Mass Commun. Soc. 15, 718–738. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2011.616277

Urban, J., and Schweiger, W. (2014). News quality from the recipients' perspective. J. Stud. 15, 821–840. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2013.856670

Van der Wurff, R., De Swert, K., and Lecheler, S. (2018). New quality and public opinion: the impact of deliberative quality of news media on citizens' argument repertoire. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 30, 233–256. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edw024

Voss, J. D., Pavela, G., and Stanford, F. C. (2019). Obesity as a threat to national security: the need for precision engagement. Int. J. Obes. 43, 437–439. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0060-y

Vultee, F. (2010). “Securitization as a media frame,” in Securitization Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve, ed T. Balzacq (New York, NY: Routledge), 77–93.

Vultee, F., Lukacovic, M., and Stouffer, R. (2015). Eyes 1, brain 0: securitization in text, image and news topic. Int. Commun. Res. J. 50, 111–138. Available online at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A444141395/AONE?u=anon~9818a588&sid=googleScholar&xid=4fd4bbd0

Wang, C. (1992). Culture, meaning and disability: injury prevention campaigns and the production of stigma. Soc. Sci. Med. 35, 1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90221-B

Wang, W. (2019). Stigma and counter-stigma frames, cues, and exemplification: comparing news coverage of depression in the English-and Spanish-language media in the US. Health Commun. 34, 172–179. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1399505

Wang, W. (2020). Exemplification and stigmatization of the depressed: depression as the main topic versus an incidental topic in national US news coverage. Health Commun. 35, 1033–1041. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2019.1606874

Westerman, D. K., Spence, P. R., and Lachlan, K. A. (2012). Telepresence and the exemplification effects of disaster news. Commun. Stud. 60, 542–557. doi: 10.1080/10510970903260376

Yigit, S., and Mendes, M. (2018). Which effect size measure is appropriate for one-way and two-way ANOVA models? A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Rev. Stat. J. 16, 295–313.

Yu, N., Ahern, L. A., Connolly-Ahern, C., and Shen, F. (2010). Communicating the risks of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: effects of message framing and exemplification. Health Commun. 25, 692–699. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.521910

Zillmann, D. (1999). Exemplification theory: judging the whole by the some of its parts. Media Psychol. 1, 69–94. doi: 10.1207/s1532785xmep0101_5

Zillmann, D. (2002). “Exemplification theory of media influence,” in Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 2nd Edn, ed J. Bryant (Mahwah, NJ: LEA), 213–245.

Keywords: exemplification theory, securitization, stigmatization, experiment, news quality

Citation: Sellnow-Richmond DD, Lukacovic MN and Sellnow-Richmond SA (2024) Exemplification in news narratives: stigmatizing and securitizing effects. Front. Commun. 9:1316677. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1316677

Received: 10 October 2023; Accepted: 19 January 2024;

Published: 08 February 2024.

Edited by:

Mihai Coman, University of Bucharest, RomaniaReviewed by:

Sergey Samoylenko, George Mason University, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Sellnow-Richmond, Lukacovic and Sellnow-Richmond. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Deborah D. Sellnow-Richmond, ZHNlbGxub0BzaXVlLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.