94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 05 March 2024

Sec. Culture and Communication

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1306309

This article is part of the Research TopicExploring the Interdisciplinary Intersection of Communication and Culture in Today's Mediated WorldView all 8 articles

Introduction: In the realm of cross-cultural film dissemination, cultural distance emerges as a pivotal factor influencing the reception of domestic audiences to foreign cinematic productions. Despite Korea's thriving film industry and China's vast film market, the cultural distance experienced by Korean films in China remains largely unexplored. This study focuses on the Korean film Silenced, renowned as a classic that champions justice in Korea.

Method: By employing qualitative survey and thematic analysis, this study investigates the cultural distance perceived by forty-four Chinese audiences when watching Silenced.

Results: The findings revealed that various content elements, such as the film's setting, translation of verbal expression, non-verbal expression of film characters, and visuals/non-diegetic music did not exhibit cultural distance among Chinese audiences. Nevertheless, the plots of morally compromised characters with positive identities, theme exploration of societal darkness and human darkness, and tragic ending introduced a palpable sense of cultural distance perceived by Chinese audiences.

Discussion: This study scrutinizes the outcomes through the lenses of Korean film and Chinese audiences. While certain aspects of Korean cinema and Chinese audience preferences exhibit cultural proximity, mitigating barriers to appreciation in select content domains, Silenced adeptly employs the plots, themes, and ending to delve into the darkness of human nature and societal dynamics. However, under the influence of China's official propaganda and film censorship, Chinese participants evinced a constrained appreciation for cinematic portrayals of human and societal darkness. Concurrently, Chinese participants manifested expectations for films to provide a source of relaxation, a notion incongruent with the oppressive ambiance evoked by Silenced.

Since the 1990s, Korea's film industry has developed rapidly in the past three decades (Jin, 2019). In a brief span, the Korean film industry experienced a noteworthy resurgence, propelled by the consistent release of widely popular and acclaimed films (Klein, 2008). Since the beginning of the 21st century, Korean cinema has become a formidable contender against Hollywood, reshaping the dynamics of the Korean film market (Yecies and Shim, 2015). This substantial achievement of resisting Hollywood's dominance in the domestic market is noteworthy. Klein (2008) contends that Korea has emerged as a guiding force in the global advancement of the film industry. Simultaneously, actively participating in international promotion, the Korean film industry has garnered significant global acclaim, as evidenced by notable recognition highlighted by Jin (2019). A prime illustration of this success is the film Parasite (2019). This cinematic triumph, clinching four Academy Awards, underscored the potency of Korean filmmaking, marking a pivotal moment in the history of Korean cinema.

The exponential economic growth and the nuanced expansion of distribution channels have precipitated a substantial surge in the demand for international films within burgeoning economies, as indicated by Kang et al. (2023). Positioned as the preeminent emerging economy globally, China, boasting a population of 1.4 billion, assumes a pivotal role as an indispensable potential film market (McMahon, 2021). The surge in popularity of Chinese film culture is evidenced by a growing number of individuals in China embracing the role of moviegoers (Song, 2018). This trend underscores the substantial potential for expansive growth within the Chinese film market. The growth trajectory of China's domestic film market has exceeded expectations, leading certain Hollywood enterprises to consider China as a major market with sustained growth prospects (Richeri, 2016). Such judgments are not groundless. In the prelude to the widespread repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, the box office revenue generated by Hollywood films in China exhibited a remarkable 60-fold increase compared to the figure recorded in 2001 (Kang et al., 2023).

Similarly, China is also a potential overseas market valued by the Korean film industry, and it aspires to expand its market share in China (Yecies and Shim, 2011; Yecies, 2016). The transnational circulation of films constitutes a fundamentally cross-cultural phenomenon, with cultural elements emerging as pivotal factors that shape audience responsiveness toward foreign films (Fu, 2013). In essence, the film constitutes a cultural interactive engagement between the cinematic medium and its audience (Eliashberg and Shugan, 1997). Following these elucidated standpoints, it is asserted that the intercultural transmission of Korean films within the Chinese context fundamentally constitutes an intricate cultural interplay between Korean cinema and the Chinese audience.

In examining the cross-cultural interplay between Korean films and Chinese audiences, a crucial consideration lies in addressing the issue of cultural distance. Cultural distance denotes variations in cultural values across countries, assessed at the cultural or country level (Sousa and Bradley, 2006). Numerous scholarly investigations substantiate the notion that pronounced cultural disparities can impede the cross-cultural transmission of films (e.g., Bergfelder, 2005; Lee, 2006; Cheng and Ma, 2014; Chen and Liu, 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Higson, 2021; Kang et al., 2023). Specifically, when introducing a film from a foreign country to the local market, certain aspects of its appeal may diminish as the local audience may not share sufficient cultural capital to fully grasp its subtleties (Lee, 2008). Countries with more different cultures are perceived to have a broader cultural distance, potentially negatively impacting the success of foreign films (Fu and Govindaraju, 2010). As asserted by Jane (2021), the findings suggest a correlation between the growing cultural distance of an imported film and an escalation in box-office losses. This phenomenon is referred to as a cultural discount (Hoskins and Mirus, 1988). It indicates the significance of appreciation differences between the indigenous program and overseas audiences (Kang et al., 2023). To outline briefly, in the realm of cross-cultural communication in film, cultural distance may contribute to the cultural discount, posing challenges in international markets (Wang et al., 2021b).

In light of the burgeoning East Asian film industry and market, it becomes imperative to gain insights into audience appreciation within the framework of cultural distance (Wang et al., 2021b). However, the cultural distance perceived by Chinese audiences in Korean film content is notably overlooked in English-language research. This study asserts the significance of addressing this gap in the literature. Korea has a burgeoning film industry with ambitions for overseas markets, while China has a very large film market. Cultural distance can pose a significant barrier to effective interaction, potentially resulting in a cultural discount within the Chinese film market. Moreover, the evolution of the internet has catalyzed transformative shifts in individuals' viewing habits (Richeri, 2016). A growing number of people now choose to engage in home-based online movie consumption, eschewing traditional cinema attendance (Richeri, 2016). The 3-year prevalence of COVID-19 has restricted people from entering cinemas, further reinforcing their viewing habits on internet-based streaming platforms (Wang et al., 2021a). Chinese audiences have gained increased access to a greater number of Korean films through streaming platforms, amplifying the significance of this study due to heightened cultural interactions.

The preceding discussion on cultural distance sets the perspective for a closer examination of a specific case study: the Korean film Silenced (2011). Silenced depicts the sexual assault and long-term abuse of disabled children by the headmaster and teachers at a school located in a remote area of Korea. Since the headmaster was wealthy and had strong local connections, his crimes were overlooked. The protagonists lead the victimized children in accusing the headmaster. However, the headmaster manages to evade justice by bribing influential individuals and ultimately receives only a lenient sentence. Silenced sparked political and legal upheaval in Korea, culminating in the reopening of the case and the enactment of more stringent legislation to protect minors and the disabled in late 2011 (Lee, 2022). The moral dilemmas and injustices portrayed in the film remain relevant across cultural boundaries. However, due to the cultural distance, Chinese audiences may have a different experience than Korean audiences when watching the film Silenced. This classic Korean film, which caused such a huge response, deserves to be taken as a case study to explore the cultural distance perceived by Chinese audiences, even though it has been years since the film was released.

Film content elements exacerbate the adverse effects of cultural heterogeneity (Wang et al., 2021b). Numerous scholarly investigations have presented analyses pertaining to the content elements inherent in foreign cinematography, which potentially engender a perception of cultural distance among local audiences. As posited by McKee (1997), the cinematic setting functions akin to a governing “law.” It delineates the parameters and limitations within which the narrative evolves, exerting a substantial influence on the rationale and progression of the story. Consequently, the audience's understanding of the setting emerges as a crucial factor in evaluating the story's plausibility, thereby shaping their holistic perception of the film (McKee, 1997). This argument emphasizes that the unfamiliarity of local audiences with the setting of a foreign film can impact their interpretation. Xue (2009) posits that superficial dimensions within foreign cinematic settings, exemplified by elements like cuisine and attire, are unlikely to engender substantial confusion among Chinese audiences. In contrast, the exploration of profound layers, notably concerning religious convictions and moral principles in foreign cinematic productions, has the potential to evoke a conspicuous perception of cultural distance within Chinese viewership.

The film serves as a medium that communicates through both verbal and non-verbal symbols (Ramière, 2010). Film characters are the key elements in making verbal expressions and non-verbal expressions. The expression of characters is in line with the aesthetic tradition of their culture (Baron and Carnicke, 2010), and the films of every country have their own expressions belonging to the culture of that country (Qiong Yu, 2014), which means that the verbal expression and non-verbal expression in foreign countries may be difficult for local audiences to understand (Berghahn, 2019).

The translational intricacies associated with verbal expressions manifest prominently in the domain of foreign films when encountered by local audiences. For indigenous audiences, the comprehension of dialogic elements within cinematic narratives is deemed a fundamental prerequisite for the acquisition of an enriched viewing experience in the context of international cinema (Fu, 2013). Consequently, proficiency in the recontextualization of verbal expressions emerges as a central tenet in the translational discourse surrounding foreign cinematic productions (Ramière, 2010). Nevertheless, whether executed through dubbing or subtitles, the translational interventions applied to foreign films serve only to mitigate, rather than eradicate, the entirety of linguistic frictions encountered by local viewers (Fu, 2013). The inherent essence of a cinematic work is often subject to a discernible degree of loss during the intricate process of translation (Wildman, 1995). Scholarly investigations indicate that Hollywood comedy and drama films heavily rely on verbal expressions deeply rooted in Western cultural contexts, thereby resulting in diminished appreciation among the Chinese audience (Kang et al., 2023). For example, the American Disney film Mulan, which was adapted from Chinese folklore, encountered challenges in its verbal expression translation. Some renditions felt awkward to Chinese audiences, diminishing their affinity for the film (Chen et al., 2021). Jones (2017) highlights that films from the European Union often face a cultural discount in the UK market due to different languages, whereas American films, being in English, enjoy greater popularity in the UK. This is fundamentally rooted in the translation of verbal expression across different languages.

Nonverbal expressions in foreign films can be presented directly to local audiences without being translated. However, it also may lead to cultural distance. The human body serves as a significant location for the expression of culture and cultural identity (Wang and Wang, 2023). In high-context culture, Oriental films often use non-verbal expressions, such as silence, subtle facial expressions, and body language (Qiong Yu, 2014). The manifestation of non-verbal expressions of this nature may present a challenge for audiences hailing from low-context cultural backgrounds (Hall, 1973). The research of Chen and Liu (2021) also shows that the non-verbal expressions of Chinese film characters often convey wrong meanings to Western audiences. Similarly, scholarly inquiries propose that nuanced non-verbal expressions depicted in Hollywood comedy and drama films may give rise to a large cultural distance for Chinese audiences; In contrast, non-verbal expressions in Hollywood action films tend to be more straightforward and typically do not result in misunderstandings among Chinese viewers (Kang et al., 2023).

The visual components present in specific foreign cinematic productions have the potential to impede the comprehension of indigenous audiences. Berghahn (2019)'s research demonstrates that while some obscure visuals in Chinese films convey distinct messages to Chinese audiences, these messages can be challenging for Western audiences to discern. As for non-diegetic music, while some studies have indicated that film music can affect audiences' understanding and attitude toward films (e.g., Boltz, 2001; Hoeckner et al., 2011), there is a dearth of literature explicitly addressing the potential cultural distance it may constitute for local audiences. This represents a promising avenue for further investigation.

Cinematic productions function as conduits for the transmission of culture (John, 2017) and exemplify the artistic manifestation of storytelling (McKee, 1997). Within the cinematic domain, the meticulous construction of the storyline assumes paramount importance (Chen and Liu, 2023), given that the storyline stands as the pivotal element and the ultimate determinant of a film's triumph (Eliashberg et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2021). Film narratives also encapsulate filmmakers' diverse cultural dimensions, including beliefs, attitudes, values, and behavioral patterns (Wang and Yeh, 2005; Wang et al., 2021b). However, local audiences' comprehension of the plots in foreign films is significantly shaped by their cultural context (Lee, 2009). The American Disney film Mulan is an illustrative example, as it draws from classic tales rooted in traditional Chinese culture but has been adapted to align with American values. Consequently, some plot elements may diverge from Chinese cultural norms, which leads to dissatisfaction among Chinese audiences (Tang, 2008). Due to cultural differences, certain plot elements in Chinese films may be perplexing to Western audiences as well. For instance, practices like corporal punishment of children, a preference for sons over daughters, and the emphasis on the ethical order within the family may be difficult for Western audiences to fully grasp (Chen and Liu, 2021). The plots of Sino-American co-productions exhibit diminished appeal for Chinese audiences (Richeri, 2016). This observation underscores that despite the participation of Chinese filmmakers and the incorporation of both Chinese and American cultural elements into the film's storyline, there remains the potential for cultural distance among Chinese viewers.

Themes, integral to the underlying message of a film, can also contribute to cultural distance. In the pursuit of endearing Eastern audiences, certain Western films integrate elements of Eastern culture. Nonetheless, scholarly inquiry, as evidenced by the work of Chen and Liu (2023), reveals that certain films in this category exploit Eastern facial representations as mere conduits for the expression of Western values, thereby hindering the cultural identification of Chinese viewers. This investigation aptly elucidates that such films predominantly leverage superficial incorporation of Eastern cultural symbols to articulate Western cultural themes in cinema, neglecting the establishment of film themes grounded in the rich tapestry of Eastern culture. Consequently, a palpable sense of cultural distance is discernible among Chinese audiences. For example, Chen et al. (2021) identify the changes in Disney's reimagining of Mulan's themes from traditional Chinese values, which caused discomfort among Chinese audiences. Similarly, Chen (2015) points out that themes related to marriage and traditional morality in Chinese comedy films may confuse foreign audiences.

Above all, the existing literature extensively looked into various content elements contributing to the cultural distance in cross-cultural communication within films, such as setting, translation of verbal expression, characters' non-verbal expression, visuals/non-diegetic music, plot, and theme. This article extends the analysis to the Korean film Silenced, examining the cultural distance perceived by Chinese audiences across these content elements.

To investigate the cultural distance experienced by Chinese audiences when engaging with the film Silenced, this article employs a qualitative survey method that consists of open-ended questions. Qualitative surveys are well-suitable for investigating people's thoughts, attitudes, and cognition toward a phenomenon (Terry and Braun, 2017; Johnson and Christensen, 2019). Given the intricate nature of the subject matter, a qualitative survey approach is chosen to capture the nuanced understanding and comprehension of Chinese audiences.

Qualitative surveys use open-ended questions and participants respond to the questions in their own words (Züll, 2016). The qualitative survey questionnaire crafted for this study comprised seven distinct items. The first six items revolved around the cultural distance perceived by Chinese participants through the film content elements, including setting, translation of verbal expression, characters' non-verbal expression, visuals/non-diegetic music, plot, and theme. For the seventh question, participants were asked to identify any additional content elements that might contribute to confusion or unappreciation, in addition to those mentioned.

The authors of the present study posted the recruitment notice on the Chinese social media platform Weibo. Purposeful sampling was employed in this study and the criteria were: (a) Participants should be of Chinese nationality and have grown up in China to ensure they have a sufficient Chinese cultural background; (b) Participants should be at least 18 years old to avoid potential harm from the film to minors. The study was granted ethical approval by the University of Malaya. The privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality of the qualitative survey participants would be protected.

When conducting a qualitative survey, the selection of an appropriate sample size should take into account the richness of the information obtained from the samples (Kuzel, 1999; Staller, 2021). The principle of saturation is commonly employed in qualitative research to assess the information richness of samples (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022). Saturation refers to the stage in qualitative data collection where no new issues or insights emerge, and the collected data start to repeat themselves (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022). This indicates that further data collection would be redundant and unnecessary, signaling that the richness cannot be increased any further and the sample size is sufficient (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022). In this research, data collection and data analysis by the researchers took place simultaneously. When the data was collected for participant forty, no new information or opinions emerged. The researchers collected data from an additional four participants (10%) and again no new data emerged. At this point, it was decided that the data richness had reached saturation and no further data collection was undertaken. A total of forty-four participants joined this qualitative survey.

Qualitative research data can be analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Terry and Braun, 2017). Thematic analysis is a useful method for summarizing qualitative data in a theoretical and conceptual way by identifying and studying hidden themes that are present in participants' responses, moving beyond mere descriptive expressions (Terry and Braun, 2017). The researchers adopted strategies of reflexivity, investigator triangulation, and participant feedback to improve the validity of the study.

Within the framework of a qualitative survey delving into the perceived cultural distance experienced by forty-four Chinese viewers during their engagement with the Korean film Silenced, it is noteworthy that the sample consisted of twenty-seven female (61.4%) and seventeen male (38.6%) participants, all within the age bracket of 18 to 28. Within this cohort, a concentration of 32 individuals (72.7%) was observed within the age bracket spanning from 18 to 23 years.

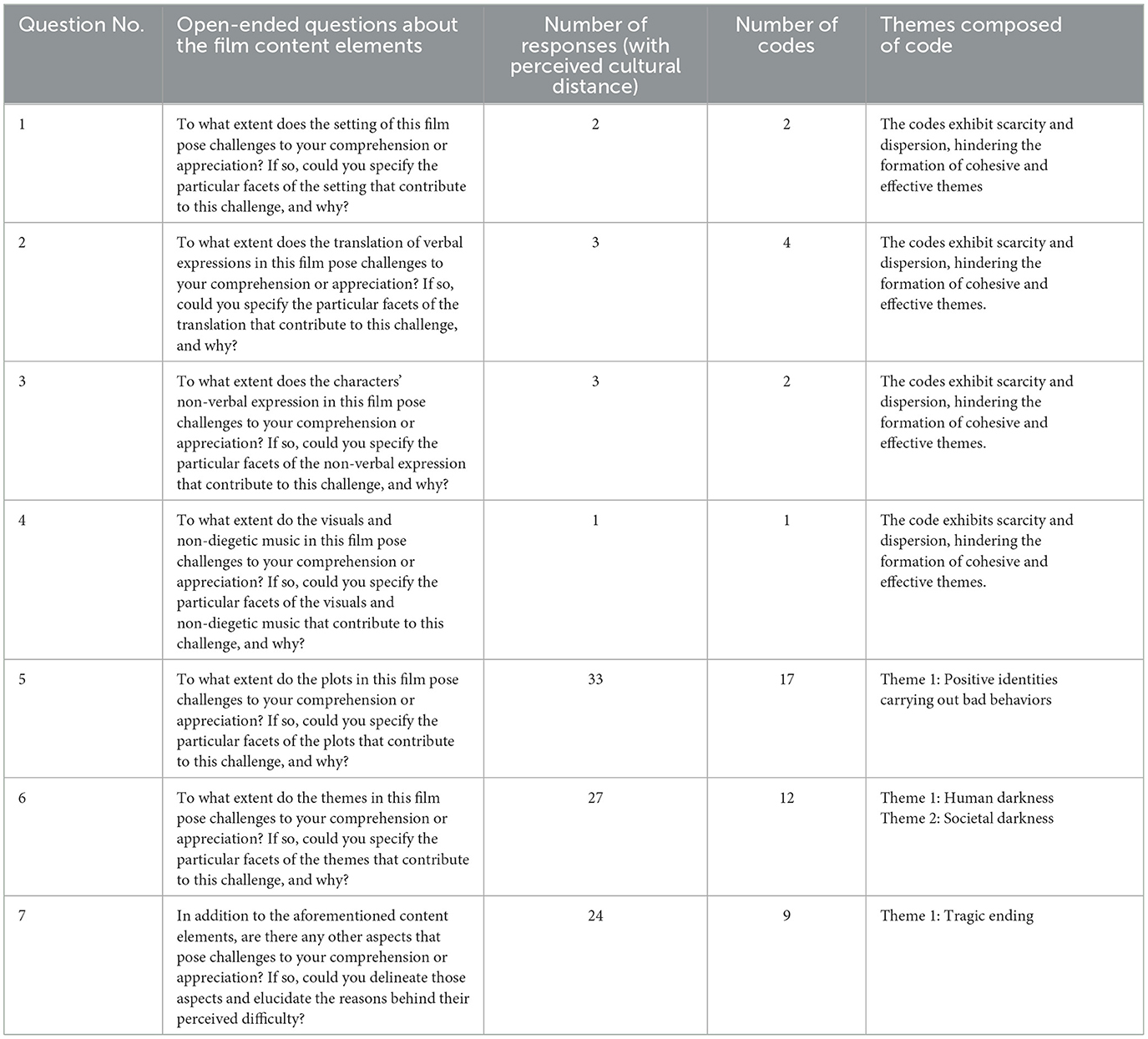

This study discerned that content elements, including setting, translation of verbal expression, characters' non-verbal expression, and visuals/non-diegetic music, did not exert a significantly adverse influence on the comprehension of this film among Chinese viewers. Nevertheless, the plots and themes of this film failed to elicit appreciation from Chinese participants, thereby making them experience cultural distance. Moreover, beyond these specific film elements, Chinese viewers also exhibited a reluctance to embrace the ending of Silenced. The results can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. The thematic analysis results of cultural distance perceived by Chinese participants through film content elements.

Within the plot elements of this film, the prevalent lack of appreciation among Chinese participants was predominantly focused on plots portraying the perpetration of deleterious actions by characters embodying positive identities. Chinese audience participants expressed that the film portrays numerous plot elements depicting positive identities in society, such as teachers, police officers, judges, lawyers, and doctors, engaging in reprehensible behaviors, and even severe crimes. For example, teaching was regarded as an esteemed profession by Chinese participants, yet the headmaster and teacher in Silenced collectively subjected the children to rape; The police, entrusted with upholding justice in the Chinese context, intentionally shielded the rapists in this film, even when fully aware of the crime. This stark contradiction posed a challenge for Chinese viewers, who struggled to reconcile how such valued members of society could commit such egregious acts, especially when committed in groups. These plots caused confusion and skepticism because Chinese audience participants thought these plots were farfetched. As one Chinese participant stated in the response, “In this film, almost every societal elite involved in this case is portrayed as a villain. Moreover, so many societal elites collaborate closely to help the criminals escape justice, completely disregarding their professional integrity. I find it difficult to believe that such a thing could happen, and it makes me feel like these professions are being smeared.”

The results also showed that the film Silenced explores themes concerning human darkness and societal darkness, which contribute to the sense of cultural distance experienced by Chinese participants. The loss of appreciation manifested in two distinct ways for the Chinese participants. Firstly, they felt that the presentation of the themes surpassed their initial expectations. More specifically, the themes of human darkness and societal darkness evoked a profound sense of oppression among some Chinese participants, a reaction they did not anticipate before watching the film. The somber thematic elements within the film unexpectedly elicited negative emotions, thereby appearing to attenuate the perceived value of the film among specific Chinese participants. One Chinese participant wrote in the response, “The themes of this movie are too dark, and it makes me feel oppressed. I originally intended to relax by watching a movie, but unexpectedly, the movie worsened my mood, making me somewhat regret watching it.”

Secondly, participants exhibited some resistance to the themes presented in Silenced because they were primarily accustomed to films that emphasize the positive aspects of society and human nature. They questioned its authenticity as a representation of society and human nature, as it deviated from their usual exposure to more optimistic portrayals from those local productions. One Chinese participant wrote, “The theme of this film is completely different from the Chinese films I usually watch. Chinese films typically praise teachers, but this Korean film is entirely the opposite.” Another participant expressed, “The theme of this film is unfounded. How could human nature and society be so dark?”

Apart from the above film content elements, the Chinese participants were prompted in the last question to highlight other elements in the film Silenced contributing to the sense of cultural distance. Many of their responses centered on the film's tragic ending. In the ending of Silenced, the rapist is given a light sentence, while other bad peoples, such as the policeman who covers up for criminals, and the judge who fails to deliver fair verdicts, receive no punishment. The bad people escaping the punishment of the law and the children not getting justice added up to a tragic ending in the eyes of the Chinese participants, and they were not satisfied with it. They believed that such an ending was not suitable for the final ending of the film—the film story should have continued to develop until all the bad people were punished. A Chinese participant responded, “The wrongdoers did not receive appropriate punishment, and such an ending is infuriating and disappointing. Why let the wrongdoers off so easily? I can't agree with such an ending.” In addition, some participants mentioned being perplexed by aspects such as character costumes, while others admitted to feeling befuddled by certain props. Nevertheless, these elements were viewed as isolated fragments and did not coalesce into a distinct overarching theme.

The study's findings revealed that the film's various elements, including its setting, the translation of verbal expressions, non-verbal expressions from characters, and visuals/non-diegetic music, contributed only minimally to cultural distance among Chinese audiences. This implies that these mentioned content elements in the Korean film Silenced did not pose substantial barriers to the comprehension and enjoyment of Chinese viewers.

This study contends that this phenomenon can be ascribed to the deliberate enhancement of cultural proximity in these content elements of the film, thereby mitigating comprehension barriers for the Chinese audience. Cultural proximity is defined as the audience's proclivity to favor and select media content originating from cultures akin to their own (Straubhaar, 1991). The concept of cultural proximity is articulated as arising from a favorable identification with foreign media texts that depict alternative ideas, values, and ways of life perceived as desirable and attainable (Iwabuchi, 2002). Additionally, it implies that audiences can more effectively comprehend and assimilate content that resonates with their cultural milieu (Fu, 2013).

In its narrative construction, Silenced strategically integrates elements characterized by broad appeal and subdued strong cultural characteristics in select content elements, augmenting the Chinese audience's cultural proximity to the film and attenuating the perceived cultural distance. More specifically, the cinematographic setting and visuals are meticulously tailored to the backdrop of Korean contemporary life, enhancing its intimacy and universal comprehensibility. It serves to alleviate potential confusion arising from cultural disparities among Chinese audiences in modern life. Language stands out as a paramount factor influencing cultural proximity (Iwabuchi, 2002). The success of translating foreign films is contingent upon the adept execution of recontextualization (Ramière, 2010). A proficient translation of foreign films entails the nuanced recontextualization in the audience's native language, thereby augmenting cultural proximity. In the case of the Chinese subtitle translation for Silenced, its seamless integration with the film's narrative suggests a successful recontextualization, effectively conveying the cinematic expression to the Chinese audience without inducing significant distress. Moreover, according to Iwabuchi (2002), the pivotal role of music and non-verbal codes in shaping cultural proximity is evident. Given the extensive history of cultural interaction between neighboring nations, Chinese audiences find the music and non-verbal cues in Korean cinema familiar, fostering a sense of cultural proximity. This familiarity ensures that these expressions do not impede their understanding or engender adverse effects.

Overall, this study asserts that the limited impact of the setting, translation of verbal expressions, non-verbal expressions from characters, and visuals/non-diegetic music in the Korean film Silenced on the acceptance and appreciation of Chinese audiences can be predominantly ascribed to the nuanced enhancement of cultural proximity within these content elements. This enhancement, to varying extents, contributes to heightened audience comprehension and appreciation.

The cultural distance perceived by Chinese participants in the film Silenced primarily revolved around its plots, theme, and ending. These three elements collectively generated a relatively high level of confusion and doubt among the Chinese participants. Films constitute an experiential cultural product emphasizing the interplay between content and the audience (Eliashberg and Shugan, 1997). Consequently, this study endeavors to analyze the cultural distance experienced by Chinese audiences due to this film, considering the perspectives of both Korean cinema and Chinese viewers.

Throughout much of the 20th century, Korea endured Japanese colonization, the Korean War, and nearly 40 years of military dictatorship, leaving profound psychological scars on the national psyche (Lee, 2019a). A trend in Korean cinema involves serving as a cultural channel for articulating the societal ramifications of these traumas. Consequently, Korean cinema tends to portray social issues, particularly adept at portraying societal darkness and people's hardships (Min et al., 2003; Jin, 2019). Various themes and genres in Korean cinema adhere to this pattern. For instance, certain zombie narrative genres in Korea attribute social disorder as the cause of zombie disasters (Lee, 2019a); Korean films with social-ecological themes always “share an aspiration to critique and sometimes satirize the common Korean social traits of self-interest and lack of empathy with others” (Lee, 2019b, p. 188); Korean science fiction films interweave symbolic themes, dark philosophies, postmodern motifs, and non-linear narrative structures, juxtaposing traditional values with contemporary societal issues while blending mystery, suspense, and social critique (Chattopadhyay, 2023). Similarly, the Korean film Silenced, under discussion in this study, is notably intertwined with pertinent societal concerns. As Lee (2022, p. 154) comments on this film, “the physical, psychological, and sexual abuse of children in a live-in school for deaf children functions as a metaphor for society's deficiencies and failings.” The film critically addresses corruption within educational institutions, alongside its broader critique of corruption within community structures and legal frameworks (Lee, 2022).

The cinematic portrayal of a profoundly corrupt and diasporic society emerges as a deliberate narrative strategy. This analysis contends that through its plots, theme, and ending, the film incrementally heightens the depiction of societal darkness, evoking within viewers suppressed anger, perceptions of injustice, and deep-seated resentment.

In terms of plot, the film Silenced highlights positive figures engaging in morally reprehensible behaviors. This narrative approach holds a greater impact on the audiences compared to a negative character engaging in similar misconduct. In essence, the bad actions by the headmaster, teacher, police officer, and judge are likely to show the darkness of human nature more effectively than thieves, ruffians, and hooligans.

In terms of the theme, Silenced transcends the confines of dark human nature and extends its focus to encompass the darkness inherent in society. Narrowing its thematic focus solely on the darker aspects of human behavior would confine its scope to the characters portrayed in the narrative, thereby limiting its capacity to contribute to societal advancement. To avert this limitation, Korean films strategically shift their thematic emphasis to the broader canvas of a dark society (Min et al., 2003). In essence, the film theme undergoes an expansion from individuals to society at large. Consequently, the film prompts audiences to recognize that it is the prevailing social darkness that begets human darkness. In Silenced, the portrayal of the fragility of legal institutions when confronted with power and wealth is illustrated. This depiction serves to enlighten the audience that the root cause behind the unjust resolution of the case lies not merely in the collusion of social elites but, more significantly, in the societal systemic issues related to the weakness of the law, abuse of power, and victimization of vulnerable groups.

As the narrative of the film concludes, Silenced opts for a tragic ending. In a legal framework that perpetuates injustice against the stigmatized, marginalized, and economically disadvantaged, where collusion among social elites leads to lenient and suspended sentences, perpetrators prevail over the child victims (Lee, 2022). The tragic ending serves to intensify the audience's societal scrutiny (Zhao, 2017). It delivers a clear message to the audience: the struggle against a dark society, no matter how fervent, is bound to end in futility. Serving as the film's ultimate expression, this message reaches the pinnacle of suppressed anger and deep-seated resentment for the audience, acting as a potent catalyst for social progress. If Silenced had concluded with a more uplifting ending—perhaps depicting the perpetrators receiving severe punishment like death—the audience might have experienced immediate satisfaction. However, such a happy ending would have provided an outlet for the audience's anger, potentially diminishing the impetus for demanding legal reform.

Hence, it is justifiable to contend that the strategic crafting of plots, themes, and ending in Silenced constructs a coherent narrative designed to portray the social darkness. Korean audiences were evoked by a strong sense of social responsibility. They vehemently criticized societal darkness, particularly the neglect of vulnerable groups. Eventually, amid a resounding outcry, Korea enacted new legislation focused on protecting minors.

Silenced utilizes its plots, themes, and ending to illustrate the profound societal corruption and diasporic challenges. Nevertheless, as revealed in the study findings, these cinematic content elements elicited a palpable sense of cultural distance among Chinese audience participants. Simply put, from the plot perspective, Chinese participants found the plots too implausible and forced, depicting the teachers, police officers, judges, lawyers, and doctors as conspirators engaging in heinous acts against disabled children. From a thematic standpoint, Chinese audiences felt distanced from the theme that “society is dark.” Regarding the ending, Chinese audiences also rejected the tragic ending where wrongdoers go unpunished. Overall, Chinese participants generally held positive views of human nature and society, demonstrating a lack of understanding and acceptance of the portrayal of human darkness and societal bleakness in the film. This article will analyze these findings from three perspectives: the Chinese propaganda system, the film censorship system in China, and the demands of Chinese audiences.

This article contends that the Chinese audience's partial reservation toward embracing the depiction of human darkness and societal darkness in Korean films is intricately linked to the influence exerted by the Chinese propaganda system. Chinese official propaganda system constitutes a significant component of Chinese political and cultural spheres, encompassing various channels of information dissemination (Shambaugh, 2017). In China, the term “propaganda” carries no pejorative undertones and is viewed by the Chinese Communist Party as a constructive and authorized instrument for enlightening the populace and advancing societal improvement (Shambaugh, 2017).

Chinese propaganda system encompasses various facets, including media content censorship, a topic of considerable significance (Shambaugh, 2017). The media environment in China is considered one of the most strictly regulated and restricted in the world, consistently ranking at the bottom in terms of international media freedom (Chen and Yang, 2019). The extent and intricacy of media censorship implemented by the Chinese government are unparalleled globally (King et al., 2013). In the Chinese context, the stringent censorship system is perceived as a vital strategy aimed at averting disorder while upholding societal stability and national cohesion (Sun, 2010). The core objective of media content censorship in China is to avert or mitigate the possibility and repercussions of unforeseen collective actions that could lead to social upheaval (King et al., 2013; Creemers, 2017). Thus, this censorship primarily targets news items with the potential to foment social unrest (Xu and Albert, 2014). Confronted with censorship, Chinese media outlets, including self-media platforms, exercise meticulous discretion. Should their content be perceived as threatening or offensive, they confront substantial commercial burdens and political repercussions (Chen and Yang, 2019). Consequently, within the Chinese media landscape, content highlighting the darker aspects of human nature and society is subject to rigorous censorship and intervention, aimed at forestalling collective public responses such as protests or demonstrations. While instances of teachers inflicting sexual assault on students also occur in China, comprehensive news coverage of such incidents is notably scarce on Chinese internet platforms due to media censorship.

Proactive propaganda constitutes another noteworthy dimension of the Chinese propaganda system (Shambaugh, 2017). It revolves around the promotion of predetermined notions of civility and public morality, chiefly encapsulated in the concept of “positive energy” (Zhengnengliang) (Creemers, 2017). “Positive energy” is a relatively recent addition to the Chinese lexicon, emerging in 2012 and subsequently elevated to the status of a national ideology over the past 10 years (Pang and Wang, 2022). Encouraged by the Chinese government, the dissemination of positive energy entails the media's responsibility to convey affirmative messages, attitudes, and values (Pang and Wang, 2022). This propagation has evolved into a guiding principle for Chinese media, necessitating the portrayal of constructive emotions, attitudes, and behaviors, the sharing of joyful experiences, the communication of kindness and care, and the propagation of justice, fairness, honesty, kindness, and moral values, along with the dissemination of positive exemplars and narratives (Pang and Wang, 2022). In essence, proactive propaganda in China pursues the redirection of attention away from societal negatives, instead accentuating optimistic and inspiring accounts of societal role models (Creemers, 2017). Therefore, Chinese media platforms are inclined to spotlight narratives featuring individuals with positive identities engaged in benevolent actions that illustrate the inherent goodness of humanity and society. These narratives often revolve around news such as police officers making sacrifices to protect civilians, doctors waiving medical fees for patients, and teachers steadfastly educating students, even in the face of illness. By selectively highlighting these examples, Chinese media outlets aim to present a brighter perspective of human nature and societal virtues.

In the realm shaped by the Chinese propaganda system, particularly through media content censorship and the proactive propaganda of “positive energy,” there exists a limitation on the exposure of the Chinese audience to news narratives featuring individuals with positive identities engaged in detrimental actions, as well as narratives portraying societal darkness. Conversely, there is an amplification of their access to news stories highlighting individuals with positive identities involved in benevolent activities, thereby emphasizing positive aspects of society. This social context has contributed to the solidification of favorable portrayals of individuals in roles such as police officers, judges, doctors, and teachers within the collective perception of the Chinese audience. Consequently, this collective exposure fosters a perception among the Chinese audience that their society is characterized by brightness and beauty, discouraging the development of a negative societal perception. In light of this, Chinese audiences posit that plots portraying the collective immoral activities of positive figures, such as teachers and police, contradict their steadfast comprehension. Similarly, the depiction of the theme related to societal darkness in the film diverges from their enduring understanding, making them feel a cultural distance as well.

The theory of just world beliefs provides an insightful perspective for discussion. This theory posits that individuals inherently require the belief that they inhabit a world where individuals generally receive outcomes commensurate with their actions (Lerner and Miller, 1978). Belief in a just world contributes to the promotion of societal order and stability (Lerner, 1980), since individuals who perceive the world as just are less likely to engage in political activism compared to those who perceive it as unjust (Furnham, 2003).

Among Chinese viewers, the familiarity with just world beliefs is evident. The proverbial expression that good deeds merit good outcomes and evil deeds lead to retribution resonates deeply within Chinese culture. China's propaganda system, dedicated to upholding social order and stability, actively disseminates narratives emphasizing social justice while selectively screening information pertaining to societal challenges. This deliberate approach significantly contributes to the reinforcement of just world beliefs among the Chinese populace.

Nevertheless, the portrayal of a corrupt and dark world in Silenced challenges the just world beliefs held by Chinese audiences. For those unwavering in their commitment to these beliefs, the disturbance arises when their convictions are confronted with evidence suggesting that the world may not be inherently just (Lerner and Miller, 1978; Lerner, 1980). This disturbance is reflected in Chinese audiences through the cultural distance they perceive in the plots and themes of the film. Moreover, in their endeavor to uphold just world beliefs, individuals seek to take action to eliminate threats to justice, with compensatory rationalization emerging as a crucial coping mechanism (Hafer and Rubel, 2015). This helps elucidate the discontent of Chinese audiences with the mild punishment of criminals at the end of Silenced. They asserted that the criminals in the film, particularly the individuals who inflicted severe harm on underage children, should face severe punishment, potentially even the death penalty. From the vantage point of just world beliefs, the stringent legal treatment of criminal suspects acts as compensation for innocent minors. When wrongdoers face retribution, the belief in a just world is restored (Kaiser et al., 2004).

This article contends that the relatively limited familiarity of Chinese audiences with the depiction of human and societal darkness in the film Silenced can be ascribed to the impact of film censorship in China. The film censorship system operates as a cultural regulatory framework, wherein the thematic elements, narrative content, and specific scenes of a film undergo scrutiny, regulation, and potential rejection if they deviate from the expectations set by the ruling class concerning this influential mass art form (Ruan, 2023). There exists a significant divergence in film censorship practices between China and Korea. While Korea abolished film censorship in the 1990s, allowing greater creative freedom, China maintains a rigorous censorship system.

In the Chinese context, films are officially recognized as a pivotal instrument for national propaganda (Cai, 2016). The strategic objective is to employ films as a means to foster social cohesion, cultivate collective identity, and propagate shared values, harmonizing China's cultural and traditional elements with the distinct features of a socialist society bearing Chinese characteristics (Richeri, 2016). Functioning as a form of soft propaganda, films wield the capability to magnify persuasive and captivating messages, subtly imparting ideology to Chinese audiences, and proficiently shaping their perceptions (Huang, 2015, 2018; Mattingly and Yao, 2022). Consequently, the Chinese Communist Party assigns considerable significance to the content showcased in films for Chinese audiences and the specific messages they intend to convey (McMahon, 2021). In this context, the Chinese government deems film censorship as indispensable (Grimm, 2015). For the Chinese government, film censorship serves as a vital mechanism to uphold societal moral standards, safeguard the mental welfare of its citizens, and project a positive image of the nation (Ruan, 2023). Despite objections from certain nations, including the United States, regarding China's film censorship system, there is no indication of China relaxing its film policy (McMahon, 2021).

The regulations governing film censorship in China were disseminated to the public via official legislative documents, including the “Regulations on the Filing System of Movie Scripts and the Management Regulations of Finished Movies,” enacted in 2006, and the “Film Industry Promotion Law,” enacted in 2017 (Ruan, 2023). The “eight types of prohibitions and nine rules of revisions” based on the regulations constitute the primary criteria upon which China's film censorship system is predicated (Ruan, 2023). This extensive regulatory framework explicitly emphasizes that films should abstain from disseminating negative values and should refrain from exaggerating the darker aspects of society. However, the delineation of censorship standards by the government, while ostensibly structured, remains mired in ambiguity (Feng, 2017; Ruan, 2023), thereby engendering challenges for cinematic practitioners and signaling broader complexities within cultural governance. For example, regulatory directives proscribe the exaggeration of societal malaise; however, the absence of operational definitions pertaining to exaggeration and societal malaise engenders interpretative subjectivity. This strong subjectivity vests considerable discretionary power in individual censors (Feng, 2017; Ruan, 2023).

This inherent subjectivity engenders uncertainty within the filmmaking community, as creators grapple with the unpredictability of censorial interpretations and strive to navigate a landscape characterized by shifting regulatory sands. To mitigate the risk of non-compliance with regulatory edicts, Chinese filmmakers find themselves compelled to augment self-censorship to preempt the inclusion of content that may run afoul of prevailing censorship doctrines. Regrettably, this paradigm of self-censorship exacts a toll on the creative latitude of cinematic auteurs (Ruan, 2023). Consequently, Chinese filmmakers often adopt a risk-averse stance, prioritizing caution over innovation in their creative endeavors. They must eschew narrative elements that might invite scrutiny or challenge from regulatory bodies, notably curbing the exploration of the darker recesses of societal dynamics. Hence, within the Chinese film milieu, productions that endeavor to illuminate the nuanced facets of societal discord are conspicuously scarce. As a result, the Chinese film market orientation tends to favor commercially viable productions, leaving limited space for films that authentically address social issues (Su, 2016).

Consequently, Chinese audiences have limited exposure to films that vividly portray societal darkness, rendering them relatively unfamiliar with such intense expressions. This lack of familiarity might impede Chinese audiences' ability to interpret Korean films depicting societal darkness effectively, consequently leading to a perceived cultural distance. The qualitative survey responses from Chinese audience participants in this study serve as compelling evidence of their limited interpretative capacities concerning Silenced. Notably, several Chinese viewers misinterpret the film's narrative elements, construing the negative behaviors attributed to teachers, judges, and law enforcement officials as deliberate vilification of these professions. Moreover, certain segments of the Chinese audience perceive the film as a disparagement of Korean society, a thematic misinterpretation that diverges significantly from the intended message of the cinematic narrative. This evident discrepancy in comprehension underscores the deficiency in decoding proficiency among Chinese audiences regarding films of this genre, leading to the conflation of “exposing darkness” with “malicious vilification.”

Due to the different social and film market environments, the diminished value perceived by Chinese audiences can also be explained by the uses and gratifications theory. This theory suggests that the communication behavior of audiences, including media selection, use, interpretation, and sharing, can be influenced by their needs (Haridakis and Rubin, 2005). In other words, in order to fulfill their needs, audiences actively engage in the selection and utilization of media.

Several Chinese audience participants, as revealed through qualitative responses, expressed discontent with their movie-watching experience. Initially anticipating relaxation, they were instead met with a sense of despondency following the film's conclusion. It shows that many Chinese audience predominantly seeks entertainment through films (Wei, 2018), aligning with Lin (1999) classification of audience media needs. For Chinese viewers, the act of watching films is primarily seen as a leisure and recreational activity, rather than an educational one. However, Korean films portraying social darkness and human darkness tend to evoke feelings of melancholy and contemplation. As a result, this departure from the conventional expectations of Chinese audiences regarding film consumption, which often prioritizes relaxation and entertainment, proves inadequate in meeting their recreational needs, thereby diminishing its perceived value.

This article has explored the cultural distances perceived by forty-four Chinese audiences while viewing the renowned Korean film Silenced. The survey results revealed that there was no significant cultural distance perceived by Chinese audiences in Silenced concerning its setting, translation of verbal expressions, non-verbal expressions of film characters, and visuals/non-diegetic music. The diminished value is mainly reflected in the plots, themes, and ending. Specifically, this film presents a multitude of instances where ostensibly positive characters engage in morally reprehensible behavior, leading to confusion, and skepticism among Chinese viewers. They also demonstrated the perception pattern which is their lack of adaptation to and acceptance of the film's dark society theme and tragic ending. The cultural emphasis on societal positivity and human virtue by the Chinese propaganda system, coupled with the restrictive nature of Chinese film censorship policies limiting the depiction of societal darkness, alongside the audience's preference for pleasurable and relaxing cinematic experiences, collectively contribute to a cultural distance experienced by Chinese viewers when exposed to the Korean film Silenced, which prominently feature the social and human darkness. As a result, the intricacies of the plots, themes, and ending in Silenced may face challenges in resonating with and being fully appreciated by Chinese audiences.

Western and Korean audiences are routinely exposed to copious news reports showcasing individuals with ostensibly positive identities engaging in morally reprehensible behavior, alongside a multitude of films that vividly depict societal darkness. Consequently, they may perceive Chinese audiences as possessing somewhat naive and idealistic viewpoints. However, contextualizing this perception within the influence of China's media and film landscape on ideological frameworks, such perspectives of naivety and idealism among Chinese audiences become more comprehensible. Notably, the participants in this study from China were exclusively young adults aged between 18 and 28, with a significant concentration falling between 18 and 23 years old. Many individuals within this demographic cohort have yet to fully transition from academia or have only recently entered the workforce, thus lacking comprehensive exposure to societal complexities and firsthand encounters with its darker facets. Deprived of personal experiences, their understanding of society is markedly shaped by media channels steeped in ideological propaganda. According to Rubin and Peplau (1975), the longer the lifespan of elderly individuals, the more social injustices they may experience. Therefore, compared to younger individuals, older people tend to have weaker beliefs in a just world. Thus, if an older age group is chosen, the cultural distance they perceive from the film may differ from the current research results.

Korean cinema boasts a rich array of genres, with films delving into societal darkness constituting just one facet. Nonetheless, exploring this thematic subset remains of paramount importance. The perceived cultural distance among Chinese audiences consuming the Korean film Silenced hints at potential cultural discounts within the Chinese film market for such thematic offerings. Building upon the insights of this study, it is plausible that Korean films centered on societal darkness may encounter obstacles of cultural distance and discount in foreign markets where media and film landscapes are more constrained. When seeking resonance with audiences in these markets, Korean filmmakers can, as suggested by the findings of this research, adapt the plots, themes, and endings to mitigate cultural distance. For instance, employing dual endings could prove effective, with versions featuring tragic endings tailored for countries with liberal media landscapes to authentically depict societal darkness, while opting for more optimistic endings in markets characterized by controlled media environments to reduce cultural distance and mitigate cultural discounts.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committee (Non-Medical). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

XG: Writing – original draft. MH: Writing – review & editing. CW: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who took part in the survey for their valuable contributions to this research. Without their willingness and time, this study would not have been possible. Their thoughtful responses and insights provided crucial data for our analysis and findings.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Baron, C., and Carnicke, S. M. (2010). Reframing Screen Performance. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Bergfelder, T. (2005). National, transnational or supranational cinema? Rethinking European film studies. Media Cult. Soc. 27, 315–331. doi: 10.1177/0163443705051746

Berghahn, D. (2019). ‘The past is a foreign country': exoticism and nostalgia in contemporary transnational cinema. Transnl. Screens 10, 34–52. doi: 10.1080/25785273.2019.1599581

Boltz, M. G. (2001). Musical soundtracks as a schematic influence on the cognitive processing of filmed events. Music Percept. 18, 427–454. doi: 10.1525/mp.2001.18.4.427

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cai, S. (2016). State Propaganda in China's Entertainment Industry. Oxon and New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315637082

Chattopadhyay, S. (2023). The rise of Korean Sci-Fi: a critique of the development of films and web series in South Korea and America. Int. J. English Compar. Literary Stud. 4, 32–50. doi: 10.47631/ijecls.v4i2.619

Chen, L. X. (2015). Analysis of Cultural discounts in North American market and current Chinese films. J. Shanghai Univ. 4, 37–49.

Chen, R., Chen, Z., and Yang, Y. (2021). The creation and operation strategy of disney's Mulan: cultural appropriation and cultural discount. Sustainability 13:2751. doi: 10.3390/su13052751

Chen, R., and Liu, Y. (2023). A study on Chinese audience's receptive behavior towards Chinese and western cultural hybridity films based on grounded theory—taking disney's animated film Turning Red as an example. Behav. Sci. 13:135. doi: 10.3390/bs13020135

Chen, X., and Liu, S. L. (2021). Genre advantage, cultural discount and cultural premium of Chinese films in the western perspective: an empirical study based on IMDb and douban data. Contemp. Cinema 3, 91–98.

Chen, Y., and Yang, D. Y. (2019). The impact of media censorship: 1984 or brave new world? Am. Econ. Rev. 109, 2294–2332. doi: 10.1257/aer.20171765

Cheng, J. W., and Ma, Y. X. (2014). Research on cultural discount of American movies in China: based on box office data from 2009 to 2013. Chongqing Soc. Sci. 7, 69–75.

Creemers, R. (2017). Cyber China: upgrading propaganda, public opinion work and social management for the twenty-first century. J. Contemp. China 26, 85–100. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2016.1206281

Eliashberg, J., Hui, S. K., and Zhang, Z. J. (2007). From storyline to box office: a new approach for green-lighting movie scripts. Manage. Sci. 53, 881–893. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1060.0668

Eliashberg, J., and Shugan, S. M. (1997). Film critics: influencers or predictors? J. Market. 61, 68–78. doi: 10.1177/002224299706100205

Feng, L. (2017). Online video sharing: an alternative channel for film distribution? Copyright enforcement, censorship, and Chinese independent cinema. Chin. J. Commun. 10, 279–294. doi: 10.1080/17544750.2016.1247736

Fu, W. W. (2013). National audience tastes in Hollywood film genres: cultural distance and linguistic affinity. Commun. Res. 40, 789–817. doi: 10.1177/0093650212442085

Fu, W. W., and Govindaraju, A. (2010). Explaining global box-office tastes in Hollywood films: homogenization of national audiences' movie selections. Commun. Res. 37, 215–238. doi: 10.1177/0093650209356396

Furnham, A. (2003). Belief in a just world: Research progress over the past decade. Person. Indiv. Differ. 34, 795–817. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00072-7

Grimm, J. (2015). The import of Hollywood films in China: censorship and quotas. Syracuse J. Int. Law Commer. 43, 156–187.

Hafer, C. L., and Rubel, A. N. (2015). “The why and how of defending belief in a just world,” in Advances in experimental social psychology, eds. J. M. Olson and M. P. Zanna (London: Academic Press). doi: 10.1016/bs.aesp.2014.09.001

Haridakis, P. M., and Rubin, A. M. (2005). Third-person effects in the aftermath of terrorism. Mass Commun. Soc. 8, 39–59. doi: 10.1207/s15327825mcs0801_4

Hennink, M., and Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Higson, A. (2021). The resilience of popular national cinemas in Europe (Part one). Transn. Screens 12, 199–219. doi: 10.1080/25785273.2021.1989165

Hoeckner, B., Wyatt, E. W., Decety, J., and Nusbaum, H. (2011). Film music influences how viewers relate to film characters. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 5, 146–153. doi: 10.1037/a0021544

Hoskins, C., and Mirus, R. (1988). Reasons for the US dominance of the international trade in television programmes. Media, Cult. Soc. 10, 499–515. doi: 10.1177/016344388010004006

Huang, H. (2015). Propaganda as signalling. Compar. Polit. 47, 419–444. doi: 10.5129/001041515816103220

Iwabuchi, K. (2002). Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780822384083

Jane, W. J. (2021). Cultural distance in international films: an empirical investigation of a sample selection model. J. Econ. Bus. 113:105945. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconbus.2020.105945

Jin, D. Y. (2019). Transnational Korean Cinema: Cultural Politics, Film Genres, and Digital Technologies. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv14t4837

John, M. P. (2017). Film as Cultural Artifact: Religious Criticism of World Cinema. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt1kgqtvf

Johnson, R. B., and Christensen, L. (2019). Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches. New York: Sage publications.

Jones, H. D. (2017). The box office performance of European films in the UK market. Stud. Eur. Cinema 14, 153–171. doi: 10.1080/17411548.2016.1268804

Kaiser, C. R., Vick, S. B., and Major, B. (2004). A prospective investigation of the relationship between just-world beliefs and the desire for revenge after September 11, 2001. Psychol. Sci. 15, 503–506. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00709.x

Kang, L., Peng, F., and Anwar, S. (2023). Review disagreements, cultural capital, and cultural discount on imported Hollywood movies in China. Heliyon 9:e22157. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22157

King, G., Pan, J., and Roberts, M. E. (2013). How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 107, 326–343. doi: 10.1017/S0003055413000014

Klein, C. (2008). Why American studies needs to think about Korean cinema, or, transnational genres in the films of Bong Joon-ho. Am. Quart. 60, 871–898. doi: 10.1353/aq.0.0041

Kuzel, A. (1999). “Sampling in qualitative inquiry,” in Doing Qualitative Research, eds. B. F. Crabtree and W. L. Miller (New York: Sage), 33–45.

Lee, F. L. (2006). Cultural discount and cross-culture predictability: examining the box office performance of American films in Hong Kong. J. Media Econ. 19, 259–278. doi: 10.1207/s15327736me1904_3

Lee, F. L. (2008). Hollywood movies in East Asia: examining cultural discount and performance predictability at the box office. Asian J. Commun. 18, 117–136. doi: 10.1080/01292980802021855

Lee, F. L. (2009). Cultural discount of cinematic achievement: The academy awards and US films' East Asian box office. J. Cult. Econ. 33, 239–263. doi: 10.1007/s10824-009-9101-7

Lee, S. A. (2019a). The new zombie apocalypse and social crisis in South Korean cinema. Coolabah. 27, 150–166. doi: 10.1344/co201927150-166

Lee, S. A. (2019b). Social ecology and ecological knowledge in South Korean ecocinema. Asian Cinema 30, 187–203. doi: 10.1386/ac_00003_1

Lee, S. A. (2022). “Socio-political contexts for the representation of deaf youth in contemporary South Korean film,” in Children, deafness and Deaf culture in literature and multimodal representation, eds. J. Stephens, and V. Yenika-Agbaw (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi). doi: 10.14325/mississippi/9781496842046.003.0011

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The Belief in a Just World: A Fundamental Delusion. New York: Plenum Press. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5

Lerner, M. J., and Miller, D. T. (1978). Just world research and the attribution process: looking back and ahead. Psychol. Bull. 85, 1030–1051. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.85.5.1030

Lin, C. A. (1999). “Uses and gratifications,” in Clarifying communication theories, eds. G. Stone, M. Singletary, and V. P. Richmond (Ames: Iowa State University Press), 199–208.

Mattingly, D. C., and Yao, E. (2022). How soft propaganda persuades. Compar. Polit. Stud. 55, 1569–1594. doi: 10.1177/00104140211047403

McKee, R. (1997). Story: Style, Structure, Substance, and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: Harper Collins.

McMahon, J. (2021). Selling hollywood to China. Forum Soc. Econ. 50, 414–431. doi: 10.1080/07360932.2020.1800500

Min, E., Joo, J., and Kwak, H. J. (2003). Korean Film: History, Resistance, and Democratic Imagination. Westport: Praeger.

Pang, Z. L., and Wang, Z. W. (2022). “Positive energy”: an examination based on the history of the concept. Media Forum. 11, 32–35.

Qiong Yu, S. (2014). Film acting as cultural practice and transnational vehicle: Tang Wei's minimalist performance in Late Autumn (2011). Transnl. Cinemas 5, 141–155. doi: 10.1080/20403526.2014.955669

Ramière, N. (2010). Are you lost in translation (when watching a foreign film)? Towards an alternative approach to judging audiovisual translation. Austr. J. French Stud. 47, 100–115. doi: 10.3828/AJFS.47.1.100

Richeri, G. (2016). Global film market, regional problems. Global Media China 1, 312–330. doi: 10.1177/2059436416681576

Ruan, J. (2023). The eyes of power: intellectual vision in contemporary Chinese local film censorship. Histor. J. Film, Radio Telev. 43, 1115–1134. doi: 10.1080/01439685.2023.2218184

Rubin, Z., and Peplau, L. A. (1975). Who believes in a just world? J. Soc. Issues 31, 65–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1975.tb00997.x

Shambaugh, D. (2017). “China's propaganda system: Institutions, processes and efficacy,” in Critical readings on the communist party of China, ed. K. E. Brodsgaard (Leiden: Brill), 713–751. doi: 10.1163/9789004302488_026

Song, X. (2018). Hollywood movies and China: Analysis of Hollywood globalization and relationship management in China's cinema market. Global Media China 3, 177–194. doi: 10.1177/2059436418805538

Sousa, C., and Bradley, F. (2006). Cultural distance and psychic distance: two peas in a pod? J. Int. Market. 14, 49–70. doi: 10.1509/jimk.14.1.49

Staller, K. M. (2021). Big enough? Sampling in qualitative inquiry. Qualit. Soc. Work 20, 897–904. doi: 10.1177/14733250211024516

Straubhaar, J. D. (1991). Beyond media imperialism: assymetrical interdependence and cultural proximity. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 8, 39–59. doi: 10.1080/15295039109366779

Su, W. (2016). China's Encounter with Global Hollywood: Cultural Policy and the Film Industry, 1994-2013. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. doi: 10.5810/kentucky/9780813167060.001.0001

Sun, W. (2010). Mission impossible? Soft power, communication capacity, and the globalization of Chinese media. Int. J. Commun. 4, 54–72.

Tang, J. (2008). A cross-cultural perspective on production and reception of Disney's Mulan through its Chinese subtitles. Eur. J. English Stud. 12, 149–162. doi: 10.1080/13825570802151413

Terry, G., and Braun, V. (2017). “Short but often sweet: the surprising potential of qualitative survey methods,” in Collecting qualitative data: A practical guide to textual, media and virtual techniques, eds. V. Braun, V. Clarke, and D. Gray (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 15–44.

Wang, C. S., Lucyann., K, and Rustono, F. M. (2021a). Film distribution by video streaming platforms across Southeast Asia during COVID-19. Media Cult. Soc. 43, 1542–1552. doi: 10.1177/01634437211045350

Wang, G., and Yeh, E. Y. Y. (2005). Globalization and hybridization in cultural products: the cases of Mulan and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 8, 175–193. doi: 10.1177/1367877905052416

Wang, J. X., and Wang, C. S. (2023). Representation of anti-racism and reconstruction of black identity in black panther. Media Watch 14, 77–99. doi: 10.1177/09760911221131654

Wang, X., Pan, H. R., Zhu, N., and Cai, S. (2021b). East Asian films in the European market: the roles of cultural distance and cultural specificity. Int. Market. Rev. 38, 717–735. doi: 10.1108/IMR-01-2019-0045

Wei, Y. (2018). The narrative mode in east Asian anti- sexual abuse films, the context and the gender culture: why is not Angels Wear White the Chinese version of Silenced? J. Chinese Women's Studs. 3, 54–66.

Wildman, S. S. (1995). Trade liberalization and policy for media industries: a theoretical examination of media flows. Canad. J. Commun. 20, 367–388. doi: 10.22230/cjc.1995v20n3a884

Xue, H. (2009). A Study on Cultural Discount in Film Trade Between China and the United States. Beijing: China Media University.

Yecies, B. (2016). “Chinese transnational cinema and the collaborative tilt toward South Korea,” in The Handbook of Cultural and Creative Industries in China, ed. M. Keane (London: Edward Elgar), 226–244. doi: 10.4337/9781782549864.00028

Yecies, B., and Shim, A. (2015). The Changing Face of Korean Cinema: 1960 to 2015. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315886640

Yecies, B., and Shim, A. G. (2011). Contemporary Korean cinema: challenges and the transformation of ‘Planet Hallyuwood'. Acta Koreana 14, 1–15. doi: 10.18399/acta.2011.14.1.001

Zhao, B. Y. (2017). South Korean crime films and their realistic expression from the perspective of Culture. Contemp. Cinema 6, 48–52.

Keywords: cultural distance, Korean film, Chinese audience, social darkness, cultural discount

Citation: Gao X, Hamedi MA and Wang C (2024) Cultural distance perceived by Chinese audiences in the Korean film Silenced: a study of cross-cultural receptions in film content elements. Front. Commun. 9:1306309. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1306309

Received: 03 October 2023; Accepted: 13 February 2024;

Published: 05 March 2024.

Edited by:

Anastassia Zabrodskaja, Tallinn University, EstoniaReviewed by:

Matthew Chew, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Gao, Hamedi and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohd Adnan Hamedi, aGFtZWRpQHVtLmVkdS5teQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.