- 1Atlas Institute for Veterans and Families, Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 2Institute of Mental Health Research, Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 3Afghan Network for Social Services, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 4Former language and cultural advisor to Canadian Armed Forces

- 5Faculty of Education, Institute for Veterans Education and Transition, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Though much research has been conducted on the potential well-being effects of deployment on armed forces members, a significant gap seems to exist in the literature when it comes to its effect on conflict-zone interpreters. Drawing on the experiences of six former Afghan-Canadian Language and Cultural Advisors (LCAs), this paper aims to contribute to expanding the nascent literature on conflict-zone interpreters by exploring how former LCAs perceive their experiences before, during, and after their deployment and the resulting impacts on their well-being. Interested in an in-depth exploration of the experiences of former LCAs, this study employed an interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach. Through the analysis, four superordinate themes emerged in participants’ narratives including: (1) the right opportunity, referring to the reasons for becoming an LCA; (2) overcoming challenges, when it comes to the work itself; (3) deserving better, relating to the experience returning to post-service life; and (4) moving forward, speaking to the current reality of participants. The results reveal key insights into the unique experiences and support needs of former Afghan-Canadian LCAs included in the study, offering an in-depth account of their experience before, during and after their service. The findings also offer important considerations regarding the support available not just to interpreters but to all contractors deployed in conflict-zones.

1 Introduction

As long as there has been human conflict, there has been a need for language brokering (Ruiz Rosendo and Persaud, 2016). Without a way to communicate, “conflict would still be possible, but not its resolution, because no one would know what the other is aiming at” (Tălpaș, 2016, pp. 242). Described by some as “oral translation of a spoken text” (Giles, 1998, p.40), interpretation can extend far beyond this definition when it comes to conflict-related contexts where interpreters have always played a vital yet often overlooked role (Hoedemaekers and Soeters, 2009; Ruiz Rosendo and Persaud, 2016; Tălpaș, 2016). During conflicts, interpreters have been asked to hold many roles such cultural mediators providing advice on local culture and customs, intelligence-gatherers, and sometimes even soldiers (Guidère, 2008; Hoedemaekers and Soeters, 2009).

Frequently coming from unrelated jobs, many conflict-zone interpreters can be considered “accidental linguists” (Baigorri-Jalon, 2010, p.21); they became interpreters simply due to their functional knowledge of a relevant language, often times with minimal or no training (Baigorri-Jalon, 2010; Ruiz Rosendo and Persaud, 2016; Ruiz Rosendo and Todorova, 2022). Despite limited research on conflict-zone interpreters, various categories have emerged including military linguists, humanitarian interpreters, and contract interpreters (Allen, 2012). Military linguists, called military interpreters by others (Snellman, 2014, 2016; Méndez Sánchez, 2021), are trained military personnel who also act as interpreters (Ruiz Rosendo and Todorova, 2022). For these individuals, it is not uncommon for them to see themselves as soldiers first and interpreters second (Kelly and Baker, 2013; Snellman, 2014). Humanitarian interpreters, on the other hand, are those who work with news and international aid organizations (Allen, 2012). Lastly, contract interpreters provide most of the interpretation services in conflict-related contexts (Allen, 2012). Contract interpreters include two separate groups: locally recruited individuals who reside near the base - called local interpreters - and national interpreters who have been living in the country from which armed forces deployed but have a knowledge of the local language (Hoedemaekers and Soeters, 2009; Allen, 2012; Ruiz Rosendo and Persaud, 2016). While national interpreters is the term used by some countries such as the Netherlands (Hoedemaekers and Soeters, 2009), other countries have different titles to represent this same group – such as Language and Cultural Advisors (LCAs) in Canada (Lick, 2019).

A great deal of research has been conducted exploring the potential well-being impacts of deployment to conflict-zones for members of armed forces (Rebeira et al., 2017; Simkus et al., 2017; VanTil et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2019), however literature on the impacts for interpreters remains scarce (Ruiz Rosendo and Todorova, 2022). Studies examining interpreters across different settings (such as in healthcare, legal, and humanitarian contexts) discuss the association between exposure to vicarious trauma – described by the British Medical Association (2022) as “a process of change resulting from empathetic engagement with trauma survivors” – and the potential effects on interpreter well-being (Geiling et al., 2021, 2022). Given that interpreters channel potentially traumatic content, this empathetic engagement with the content has been linked to consequences such as increased psychological strain, burnout, and compassion fatigue (Lai and Heydon, 2015; Daly and Chovaz, 2020; Geiling et al., 2021; Ruiz Rosendo and Todorova, 2022). In the case of war and conflict-zones, considered “the epitome of trauma” (Barnardi, 2022, p.199) by some scholars, the interpretation of potentially traumatizing content is merely one of the many possible sources of trauma (Tălpaș, 2016).

Through interviews with former interpreters who worked in either Croatia or Bosnia-Herzegovina, Barnardi (2022) categorized potential trauma-related sources of interpreting in a conflict zone into three categories: factors related to the context of the work, those related to the job itself, and those related with the content of the work. Further to the potential for vicarious trauma described above, factors related to the content translated have been associated with long-term health effects such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Barnardi, 2022). Job-related trauma factors include the working conditions interpreters live through while carrying out their duties (e.g., weather, job security, available supports etc.) (Barnardi, 2022). Lastly, context-related trauma factors relate to the fact that interpreters are not solely translating the conflict but also experiencing it (Barnardi, 2022). It has been suggested that some context-related factors may be unique to interpreters, and especially traumatic, in situations where they are considered and/or consider themselves to be working for the “other” side (Bos and Soeters, 2006; Barnardi, 2022). In these cases, some researchers suggest that having ties to two separate groups while trying to balance both – the military they work with and the locals they are in contact with – leads to their group ties being “tortured” (Bos and Soeters, 2006; Hoedemaekers and Soeters, 2009). This has been mentioned, among others, in relation to contract Afghan interpreters during the mission in Afghanistan, (Bos and Soeters, 2006) in which Canada was involved.

In response to the events of September 11, 2001, Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) joined other countries in conducting operations in Afghanistan, sending around 40,000 members over more than 12 years in the country (Government of Canada, 2018). Although Canada’s combat role in Afghanistan ended in 2011, members of the CAF remained in the country training Afghanistan’s army and police force until March 2014 (Veterans Affairs Canada, 2019). During this time, the CAF relied on Afghan contract interpreters, including approximately sixty-five Afghan-Canadian citizens who deployed and accompanied soldiers outside the wire working as LCAs (Brewster, 2019) where they were exposed to potentially traumatic events (Lick, 2019). Considered civilian contractors, LCAs did not have the same access to supports and services upon their return as soldiers with whom they were deployed (Veterans Affairs Canada, 2015).

The literature on conflict zone interpreters is still nascent with only few studies exploring their experiences. There are even fewer publications exploring interpreters’ experiences transitioning back to civilian life after the conflict, and the lasting well-being impacts of their work. This is especially true of LCAs who worked with the CAF in Afghanistan. Drawing on the experiences of six former Afghan-Canadian LCAs, this paper aims to contribute to expanding this nascent literature by exploring how former LCAs perceive their experiences before, during, and after their deployment and the resulting impacts, using a qualitative research approach.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

Interested in an in-depth exploration of the experiences of former LCAs, this study employed an interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach (Smith, 1996; Smith and Shinebourne, 2012). With theoretical links to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and idiography, IPA as an analytical process is concerned with how individuals make sense of their individual experiences (Smith and Shinebourne, 2012; Pietkiewicz and Smith, 2014). With IPA, the researcher is attempting to interpret the participant’s experience while they themselves are making sense of it (Smith and Shinebourne, 2012); leading Smith and Osborn (2003) to describe the process as a “double hermeneutic” (Smith and Osborn, 2003). Beyond the scope of this paper, further information on the origins and history of IPA is available in Smith (1996) and Smith and Shinebourne (2012).

The researchers assembled an advisory committee as part of the project, to provide insight and guidance on the study and its procedures. The advisory committee included individuals with lived and living experience related to the topic of this research. Advisory members were involved as partners across multiple aspects of the study including building the protocol, reviewing the interview guide, assisting with recruitment of participants, and informing dissemination of findings.

2.2 Participants and data collection

Participants in this study included a purposive sample of six former LCAs who worked with the CAF in Afghanistan. In-line with the IPA approach, the authors aimed to get accounts from enough former LCAs to be able to identify differences and similarities in experiences, while still being able to fully appreciate each account through an in-depth case-by-case analysis (Smith and Shinebourne, 2012; Pietkiewicz and Smith, 2014). Members of the study’s advisory committee and others with existing connections to the LCA and Afghan community initially approached potential participants and invited them to connect with the researchers. Participants were eligible to participate if they were capable of conversing in English, were 18 years of age or older, and self-identified as having formerly worked as an LCA with the CAF in Afghanistan. Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Board at the University of Ottawa Institute for Mental Health Research (IMHR-REB #2021029). All participants provided informed consent.

Participants completed a brief online demographic survey with questions about themselves, their work as an LCA, and their self-rated health. Following the survey, participants were invited to participate in one-on-one, semi-structured interviews (interview guide available in Appendix A). Two of the authors (GD and JMM) conducted the interviews. Participants were asked about their life prior to working as LCAs, reasons for becoming LCAs, and their experiences during and after their work with the CAF in Afghanistan. Due to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted either through a professional Zoom account or over the phone, with participants having the flexibility to participate in the interview from an environment of their choosing. With participant consent, interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for future analysis.

Interviews lasted between 26 and 62 min and were conducted between November 2021 and July 2022. Due to technical issues with audio, one interview had to be done a second time, which may have affected the experiences shared by this participant. In order to protect their identity, generic labels are used in this manuscript when referring to participants.

2.3 Data analysis

Analysis of the data, completed in NVivo analysis software, followed a similar process as that described by Smith and Osborn (2004). Immersing themselves in the data, two of the authors (JMM and VC) read and re-read the first transcript independently, making notes of their observations and reflections (Smith and Osborn, 2004;Smith and Shinebourne, 2012; Pietkiewicz and Smith, 2014). Emergent themes were then identified, clustered, and discussed between the two authors. The themes from the first transcript were then used to help orient the analysis of the second transcript. The themes were updated as necessary, respecting the divergences and convergences in the data (Smith and Osborn, 2004). This process continued until all transcripts were analyzed, and a final table of superordinate themes was created (Smith and Osborn, 2004). One last analysis of each transcript was completed using the final table of themes (Smith and Osborn, 2004).

3 Results

The study procedures resulted in a total of six in-depth interviews with former LCAs. This sample size is consistent with the IPA approach and its aim to give a full appreciation to each individual participant’s account (Smith and Shinebourne, 2012; Pietkiewicz and Smith, 2014). All participants were males who had immigrated to Canada before 2002.

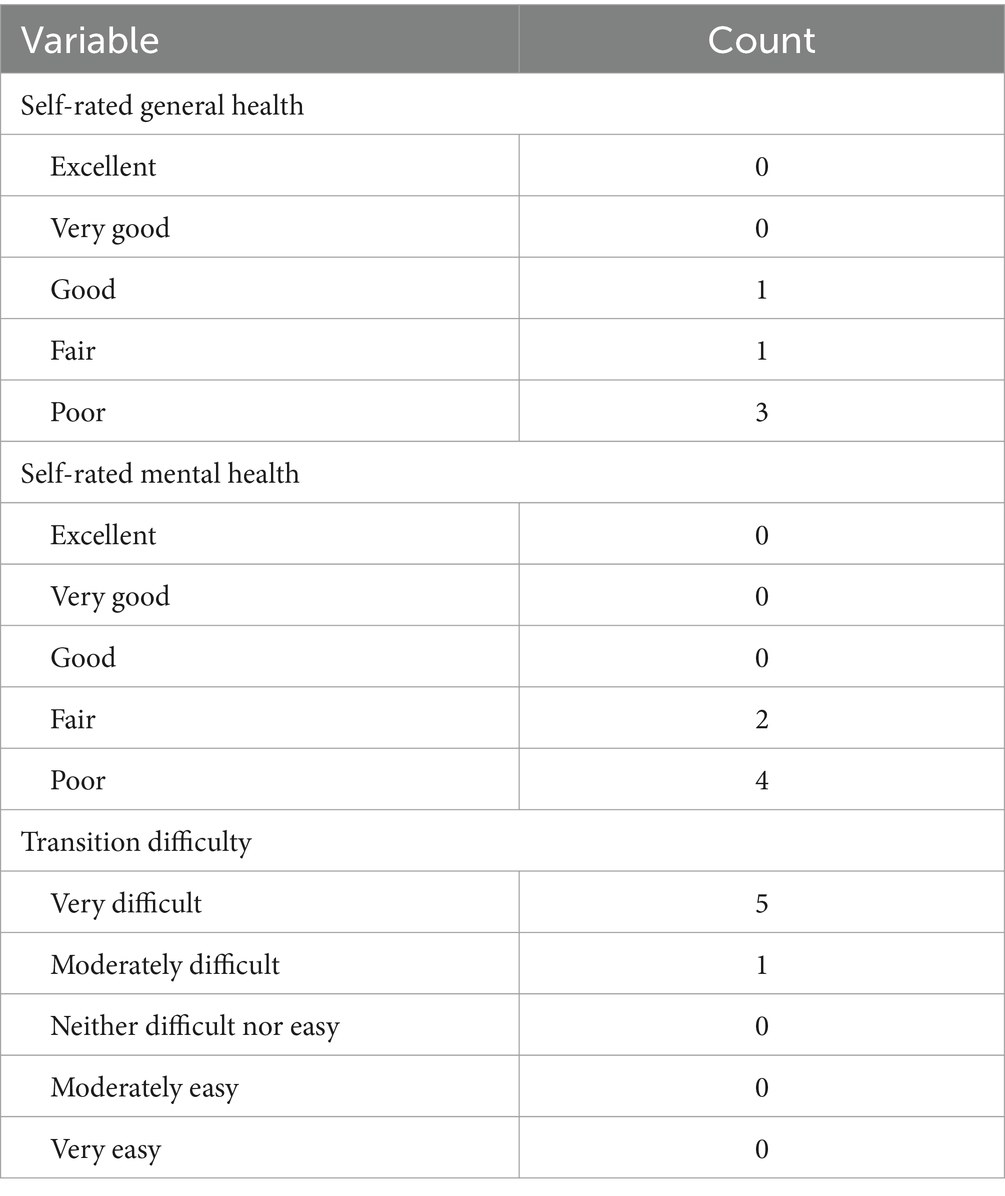

Concerning their work as LCAs, participants started working for the CAF between 2006 and 2009 and left Afghanistan between 2010 and 2011. They worked an average of 6.2 deployments (range 3–9) over an average of 3.8 years (range 1–5). Further participant demographics are not presented to protect participant identity. Participants’ self-rated mental health varied between Fair and Poor (Table 1).

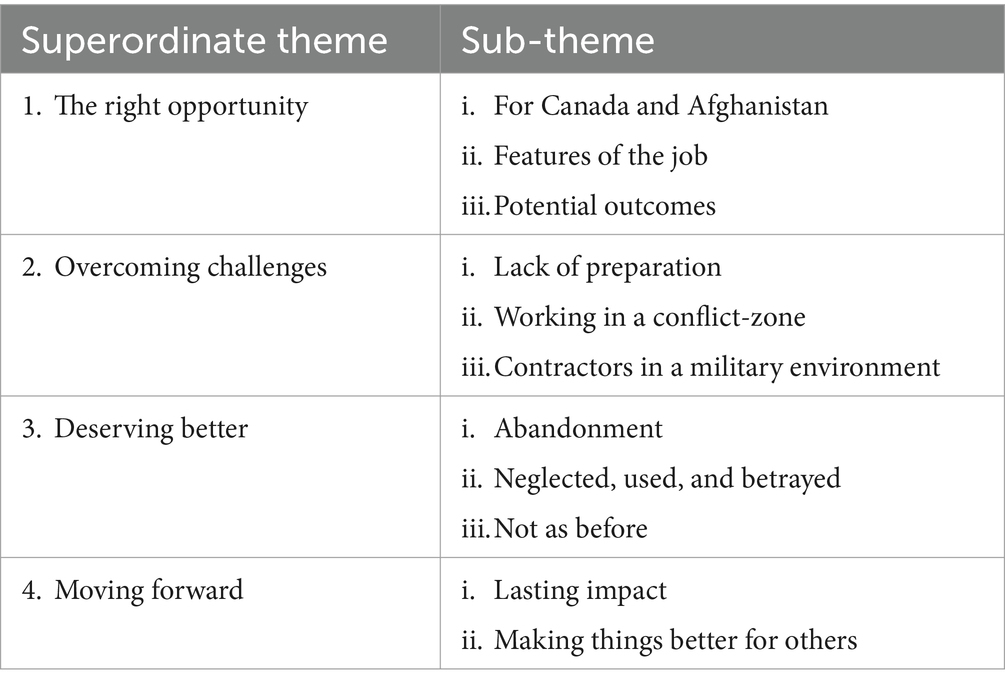

Through the analysis, four superordinate themes emerged, corresponding to different phases of their experience: (1) the right opportunity, (2) overcoming challenges, (3) deserving better, and (4) moving forward (Table 2).

3.1 The right opportunity

Participants were asked to share the reasons behind their decision to become an LCA. Their pre-LCA narratives tended to focus on their backgrounds as immigrants to Canada, motivations, and descriptions of the job itself, which together offered the right opportunity. Three distinct sub-themes emerged from these narratives: (i) for Canada and for Afghanistan, (ii) features of the job, and (iii) potential outcomes.

3.1.1 For Canada and for Afghanistan

Traversing all interviews was a shared sense of dual loyalty, both to Canada and to Afghanistan. Aptly captured by Participant 11 in describing their decision to become an LCA: “one is my birthplace and one is the place who helped me to live.” This dual loyalty was an important factor, with many viewing the role as an opportunity “to go out and help both nations” (Participant 6). For example, Participant 10 expressed similar notions when explaining his decision:

Think about it, I was born in Afghanistan and my family still lived in Afghanistan and then I was a citizen of Canada. My children were born in Canada. So, now, you know, we were against beating up on Afghan people, and they were beating us […] for me it was brother killing brother, you know? And it was very important for me to be there and to do my part to save both sides. (Participant 10)

For some, there was an added desire to ‘give back’ to Canada for bringing them into the country. Participant 11, for example, explained: “I left Afghanistan and I went to Pakistan, Iran, India and so many countries. And finally, I came to Canada and Canada accepted me as her citizen and I wanted to pay back.” Another participant detailed similar sentiments following community encouragement:

We had, in our community, at that time we had like everyday announcement. It was announcing that Canadian, the Canadian government, the Canadian Armed Forces desperately needed help […] community members were encouraging people to go and help out the Canadian Armed Forces in Afghanistan. And then, I decided that, okay, you know, that everything that Canada had done to me, this was the time to pay back. So, let’s get up and go and do that. (Participant 4)

3.1.2 Features of the job

Participants highlighted additional factors related to the job itself, which made becoming an LCA the ‘right opportunity’ for them. While there was diversity in their professional and educational backgrounds, none had worked as an interpreter prior to becoming an LCA. Their unique knowledge and backgrounds as Afghan-Canadians, however, made them feel qualified for the work and, for some, motivated them to apply. In describing their decision-making process, Participant 4 reflected on how “[…] not a lot of people were entitled or were able to go do that, you know, language skills, you know. Have the language skills, and go to the war zone […].” Another participant highlighted their cultural knowledge of both nations and how this influenced their decision:

Based on those, you know, experiences that we had, the knowledge we had, I totally understood that it was one of the most important things to do for both Afghans and Canadians…You know, we understood the language, we understood the culture and the political systems and the history […] There’s a language that anybody can learn to speak but there’s a culture. You know, when you speak a sentence in English, there is a culture behind it. You speak a sentence in French, there is a whole culture behind it. So, that intricacies, cultural intricacies were very important for us. And that’s really why I joined to go back to Afghanistan. (Participant 10)

For others, like Participant 11, the primary motivator was that working as an LCA was “a job” and could help pay their bills. Although participants were not directly asked about their immigration experience, some highlighted struggles such as learning English and affording the cost of living. Participant 3, for instance, highlighted financial motivations for himself and others, speculating, “[…] everyone, when they went down there, there was no other […] option or, they had made the decision because of the financial situation.”

3.1.3 Potential outcomes

When reflecting on their decision and the opportunity presented to them, a number of participants touched upon the broader outcomes and wider meaning of the work of an LCA. For them, the opportunity presented was one to make a difference in the lives of others. These outcomes included safety and security of CAF members, connection between the CAF and Afghan people, shared cultural awareness, and peace for Afghanistan.

Participant 11 captured some of these sentiments in recounting and reflecting upon their decision to “work side by side with the Canadian military soldier.” In particular, he described how he wanted “…To save [CAF members’] lives; to show—to tell them about the culture, […] of Afghan; what they should do; what they should not do, and where is the danger and how they prevent that danger…” as well as “to bring some change to Afghanistan.” Another participant expressed similar sentiments:

…when I heard that the Canadian Forces, they needed the support of some people, Canadians, Afghan-Canadians, who could help them with the communication with Afghans while they had the mission in Afghanistan. So for me, it was like a double-positive opportunity, like, to help Canadian Forces or Canada on the one side and also to help Afghanistan […] to reach a point that there will be peace and prosperity over there. (Participant 2)

3.2 Overcoming challenges

Participants were asked to describe their experiences of working as an LCA, including any positives or negatives from that experience. While describing the situation they experienced as LCAs for the Canadian Armed Forces in Afghanistan, three sub-themes emerged as they spoke about the challenges they overcame: (i) lack of preparation, (ii) working in a conflict-zone, (iii) civilian contractors in a military environment.

3.2.1 Lack of preparation

Among participants, there was a shared feeling that they had not been adequately prepared for what they had stepped into: “[…] they put me in a vehicle and we went towards the front line. […] I was kind of scared that day, you know. I thought we would go inside the base and stay there.” (Participant 4).

From lack of training before deployment, to lack of understanding of what was going to be expected of them, participants felt more could have been done before being sent to Afghanistan with CAF members. Despite this lack of preparation, participants rose to the challenge and adapted to fulfill the many tasks expected of them. Participants described fulfilling many roles while deployed, some of which were outside of the scope of a traditional interpreter. These included advising on the mission, advising on local culture, being a voice of reason in heated and difficult situations, communicating with the local population, and also being an advocate for Canada. Participant 3 highlighted the importance of their presence explaining: “We were their eyes; we were their ears; we were their tongue. Without us, they could not, you know, could not go one step forward.”

3.2.2 Working in a conflict-zone

As their work required them to follow CAF members outside the wire – or outside of the base - participants were exposed to and witnessed many difficult situations associated with conflict-zones first hand. Seeing dead bodies, including some of their friends, living through suicide bombings, rocket attacks, ambushes and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), participants described many potentially traumatic situations usually only thought of when thinking of serving military members.

And you are a witness. Witness somebody kill [in] front of you, your friend, your colleague is killed by a known enemy inside Afghan garrison, in the Afghan military base […]. (Participant 11)

As difficult and potentially traumatic as the situation they were put in was, participants were still able to see the positive of their experience as they had found something that gave them purpose. When asked if there were any positives from their experience, most mentioned knowing that regardless of what they lived through, they felt like they had made a difference through their work. This sentiment is summarized aptly by Participant 10: “[…] imagine if we were not there.”

3.2.3 Civilian contractors in a military environment

The last sub-theme identified relating to overcoming challenges was the experience of being a civilian contractor, especially one who goes outside the wire in a military environment. All participants described some unique situations they experienced because of being civilians, however, some had more positive outlooks on these experiences than others. While some felt respected and valued for their contributions, others like Participant 2 felt like they were never quite accepted: “So, the major thing is that despite providing all the information and the intelligence and working with them, I never felt I had been trusted.”

Although many comparisons can be made between the experiences of armed forces members and LCAs outside the wire, the uniqueness of the situation for conflict zone interpreters cannot be ignored. When describing being attacked and asking armed forces members for a weapon to defend himself, Participant 3 recounts his experience of having to sit and wait to find out what fate was awaiting him:

Everybody had a weapon to defend themselves, but I didn’t have anything. […] [I said:] “I don’t want to get captured by Taliban”. They didn’t, they didn’t give me that. They were not allowed to give me [a weapon]. They told me just, “you stay in this tent and lay down. We go fight. What happens, happens”. And you are waiting for when Taliban comes and gets you and torture you and kill you. So, what kind of experience is that going to be?

3.3 Deserving better

While most participants took away some positives from their experience working as LCAs, the same cannot be said about their experience transitioning back into post-service life. When asked to speak about this period, three sub-themes emerged in the narratives speaking to the feeling of deserving better than what they experienced: (i) abandonment, (ii) neglected, used, and betrayed, and (iii) not as before.

3.3.1 Abandonment

Putting themselves in harm’s way as LCAs, participants expected their country to be there for them upon their return, as it had been once before. Once they came back however, they were met with “nothing, nothing, nothing. Not even a telephone call. Not one single telephone call” (Participant 2). This led participants to experience a difficult transition back to post-service life, with a feeling of having nowhere to turn to for support:

When I came back from Afghanistan after the deployment, it was very difficult to adjust to civilian life, plus the PTSD kicked in and there was absolutely nowhere for us to turn, nowhere to go and no how. (Participant 10)

Having worked side-by-side with CAF members while in Afghanistan, participants considered they too served their country and could not help but to compare the situation they were faced with, and what they lived through, to their former colleagues. Knowing about the supports and services available to CAF members and CAF Veterans, participants failed to understand why these same services were not available to them.

They had the facilities. They had safeties for the soldiers. For the soldiers and officers, but we were in the same situation, in the same condition, but they didn’t have those facilities. They didn’t give us any advice. They didn’t give us any, any, any kind of things. They just forgot about us when we came back. (Participant 3)

While participants mentioned eventually consulting a healthcare professional, sometimes many years after their return, the results were mixed and in some cases, no follow up was provided.

Despite they realized that I had PTSD, and despite they realized that I had depression and I was suffering from extreme anxiety, there is nothing. Like, nothing comes up. It’s just about—it’s all about talks. (Participant 2)

They were faced with the reality that the devotion they had toward the country they were calling home was not reciprocated, leaving them feeling neglected, used, and betrayed.

3.3.2 Neglected, used, and betrayed

In some way, all participants shared a feeling of betrayal or abandonment. Reflecting on their overall experiences, the abandonment they experienced led to a perceived betrayal, which was more significant in terms of impact on participants than anything they experienced while working in the conflict-zone. This sentiment is illustrated by Participant 10: “The hardest part was not so much the war but the neglect, the absolute neglect […] That was really hurtful.”

Transition to post-service life and the repercussions of their experiences was uncharted territory for participants and they were once again faced with a situation for which they felt unprepared. As had occurred when they joined the Canadian Armed Forces as LCAs, participants had an expectation that they would, at least initially, be guided through this new situation by an authority who knew, or should have known, the potential repercussions of their experiences. As illustrated by Participant 2, part of the feeling of betrayal originates from a sense that those who sent them into a conflict-zone knew of the potential consequences and still chose to provide no support: “And there was no help, no support, nothing, while they knew that I would have been affected by what I went through.”

Another part of the betrayal felt by participants is related to the lack of follow up or acknowledgement, even privately, for their contribution to the mission in Afghanistan. Most participants felt abandoned and used, with no one seeing how they were coping after their return:

Forget about the other thing, even we were not deserve for a call, or a telephone call, “How are you?” It’s very simple. […] They didn’t! They didn’t. […] We were dropped like a garbage. We were garbage, and garbage, and the garbage that cannot be recycled. (Participant 11)

This experience led some participants to question how this betrayal was even possible: “What is going on? Are we, are we human beings or not? Are we Canadian or not?” (Participant 3). The combination of participants’ experiences outside the wire and transitioning back to post-service life had repercussions on all aspects of their lives and well-being.

3.3.3 Not as before

Speaking to the impacts, participants linked the sum of their experiences described above to repercussions on many different domains of their lives. If not explicitly, all participants expressed living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or related symptoms such as sleep disturbances: “It’s always, I mean, for the past couple of years, like, I have almost no sleep at night. Maybe I have, like, a few hours, you know, at the beginning of the night and then I am up always until, like, 4 or 5 am” (Participant 4). Other direct repercussions mentioned by participants included depression or anxiety, chronic pain, irritability, loss of life enjoyment, and financial issues due to inability to find and keep a job. For some participants, these impacts were exacerbated by the fact that their ties to their community and families had also been broken as a result of their work.

I realized that, basically, the community that I was basically involved in actively before I went for the mission, before the deployment, they didn’t take me in as a member because most of the people here, they believed that I betrayed the—basically, my country, helping the invaders. They are many who think like that. (Participant 2)

When I came home, I found out that, still, after two years, I don’t feel I am part of this family, and part of this house. I’m in a small room, sitting alone. Cooking for myself. Going in, uh, just, just, go every, in the morning, even in the morning, I’m not going anywhere. […] I think they turn against me. They think I turned against them. And, and this situation, they destroyed my life, destroyed my family life. (Participant 3)

Even for participants whose ties were still intact, they spoke to how their experiences reverberated across their connections in some way. For some, this meant not being able to communicate with them anymore:

[…] I didn’t know like, what should I say it’s not confidential, what should I say is confidential. […] I couldn’t say anything about my experiences up there, and I was just inside of me… I think that was the main cause of my problems. (Participant 6)

For others, this was seeing their loved one living with the consequences of their experiences:

The truth is that they are naturally affected when they see their father or their partner, you know, can’t sleep or can’t take a shower by himself […] And I would have panic attacks so I would call my partner and say, “Leave your job. Come to me because I am dying.” I mean, that affects my family, that affected everybody. (Participant 10)

The combination of these impacts led some participants to feel as though everything they knew before working as LCAs, including themselves, had been broken.

3.4 Moving forward

Faced with the challenge of adjusting to a new reality while trying to manage their experiences as best they could, participants needed to pick up the pieces of what was their pre-service life and try to move forward. Speaking to their current reality, participants discussed how their experiences still affected them today and how things could be improved moving forward. While all participants were at a different point in their journey to recovery, two sub-themes emerged from the narratives: (i) lasting impact and (ii) making things better for others.

3.4.1 Lasting impact

Most participants who were interviewed were still early in their recovery journey, living with the lasting impacts of their experiences, waiting for the support they feel they need and deserve. This ranged from being unable to work for some “unfortunately, I cannot work. I cannot do anything. It’s very, you know, a very bad situation” (Participant 4), to feeling like “there is a burden, like I carry on my shoulder. The life is a burden I carry on my shoulder” (Participant 3) for others.

Many years later, the fact that still, “there is no help facility available […] there is no financial availability. There is nothing.” (Participant 11) has led to a lasting sense of resentment in most participants. On the other hand, those participants who seemed to be further along in their recovery felt that to get there, they had to take their recovery into their own hands. They could not, however, have done it without the support of those around them: “I have a good partner […] she was the greatest asset to me” (Participant 10).

3.4.2 Making things better for others

When asked to provide recommendations based on their experiences, all participants indicated that one of the most important aspects would be to provide any sort of support or follow up, but specifically the same types of well-being supports received by the CAF members with whom they served and their families:

Number one, it would have been very important, like, if they had a resource available or had access the same resources. Okay, look, let me give you an example. When a soldier is killed in Afghanistan or anywhere else in the world, his family has access to psychiatrists and psychologists in the army or in the Canadian Forces. […] But to me, when we lost our comrades, our people who we served with day and night, and then we saw the same thing, we saw—we were shot at, we were blown up, we were suicide bombing and everything like that. We repatriated those people, but we come to Canada and there is absolutely nothing? (Participant 10)

The importance of including families in the supports could not be understated by participants and for some, having someone talk to their families was mentioned as what would have been the most important thing upon their return. Expanding on the resources and supports that participants believed would have been helpful, they mentioned that access should be available immediately after their return, including support for financial and work-related impacts, and be provided by trained healthcare professionals with the proper clearance. The level of clearance was the only potential barrier to accessing supports mentioned by any of the participants, and especially important for Participant 6:

The only thing was, all that was stopping me from anything, to come up is the level of secrets that go around that our job requires us to do, so. And, there was some medical officer who I could not even tell him anything, because he didn’t have the clearance level that we had.

Despite the fact that all participants were former LCAs, they did not limit their recommendations to LCAs only. Rather, some made recommendations that extended to all civilian contractors: “when somebody is sent to the battlefield and he work in the battlefield, does not matter—he’s LCA, language, cultural advisor or he has other job like intelligence and so and so, he must receive the same benefit as a soldier […].” (Participant 11) Overall, the main sentiment included in all participants’ narratives was summarized by Participant 6 in that: “as a Canadian, as a human being that returned back, you are sending, if you are sending people away, when they come back, you should take care of them.”

4 Discussion

This study explored the experiences of former LCAs who served with the CAF in Afghanistan from their pre-service background to current day impacts. Hired as civilian contractors, these LCAs were not members of the CAF. In line with the available literature on conflict-zone interpreters, participants in this study had no previous experience with interpreting and became LCAs with limited training, due to their functional knowledge of Pashto and Dari languages (Baigorri-Jalon, 2010; Ruiz Rosendo and Persaud, 2016; Ruiz Rosendo and Todorova, 2022). Mostly shared when referencing pre-service reasons to become LCAs, many participants in the current study mentioned having ties to both Canada and Afghanistan. This situation has been discussed in the literature as having the potential to lead to especially traumatic situations over the course of interpreters’ work (Bos and Soeters, 2006; Barnardi, 2022). Contrary to what could be expected based on the limited literature, however, these multiple ties were not mentioned by participants as a cause for potentially traumatic experiences; only as a reason for agreeing to become an LCA.

As mentioned in a 2013 RAND Corporation report, although contractors are not supposed to engage in any offensive combat, this does not preclude them from being exposed to many of the same situations as serving military members (Dunigan et al., 2013). In terms of experiences while in the conflict zone, as previously mentioned, a recent study on interpreters categorized potentially traumatic experiences as relating to the context of the work, the content of the work, and the job itself (Barnardi, 2022). Experiences described by participants in this study while in Afghanistan can be considered using these same categories. Context-related factors mentioned in the literature, such as constantly fearing for their own lives and living in besieged cities, were also discussed by participants in the current study corroborating existing literature (Barnardi, 2022). Similarly, job-related factors mentioned by participants such as adverse temperature conditions, working long hours without pause, and traveling in hostile areas also align with experiences of conflict-zone interpreters in the literature (Barnardi, 2022). Of note, there are important divergences in terms of content-related factors for this present study compared to other literature.

Although much of the available literature on interpreters focuses on the potential for vicarious trauma through the content of what is interpreted and the resulting consequences (Lai and Heydon, 2015; Daly and Chovaz, 2020; Geiling et al., 2021; Ruiz Rosendo and Todorova, 2022), the actual interpretation of content was not mentioned by present study participants as being traumatic. Instead, the majority of described potentially traumatic situations related to more “traditional combat stressors” (Watkins, 2014, p.9). These traditional combat stressors, such as death and violence, have been linked to mental health problems in CAF and other military members (Sareen et al., 2007; Bouchard et al., 2010; Thompson et al., 2019). Other potentially traumatic experiences shared by participants included feeling unprepared and uncertain, and feeling “othered” and isolated. Lack of unit cohesion and mission uncertainty has also been highlighted in studies on serving military members, including CAF members (Watkins, 2014). The uniqueness of the potentially traumatic experiences mentioned by the participants in this present study, which contains both similarities and differences to experiences of traditional interpreters, as well as experiences of serving military members, suggest that national conflict-zone interpreters, like LCAs, are in a unique situation where they cannot only be considered one or the other. Rather, future research is needed to develop tailored supports and services for this group.

A significant gap identified in the literature related to national interpreters’ experiences upon their return. Few studies, if any, seem to exist on the transition period from service to post-service life for national interpreters – especially LCAs. Studied in military members, this transition period has been highlighted by scholars as a period where the need for services and support is the highest (Thompson et al., 2017). As highlighted by participants in the present study, very little support seemed to be available for LCAs during this crucial transition time. The absence of services and supports led to further consequences, creating feelings of abandonment and betrayal that was, and are still, felt by participants. Of note, this feeling of betrayal from an authority has been previously linked to the concept of moral injury (Shay, 1991; Shay, 2014). Described in the military and Veteran population as a “betrayal of what is right, by someone who holds legitimate authority, […] in a high stakes situation” (Shay, 2014, p.183), the concept of moral injury may also be relevant to the LCA population upon their return from deployment. Based on participants’ narratives, this feeling of betrayal may be even more impactful on their well-being than their experiences while deployed. Future research should specifically explore moral injury in former LCAs, to better understand this nuanced experience.

Further consequences mentioned by participants stemming from the entirety of their experiences as an LCA included PTSD, chronic pain, and depression. This supports other literature on the impacts of deployment on contractors, which indicate that deployments to combat theatres have implications for both physical and mental health (Dunigan et al., 2013). Further, the results of this study support the finding that many contractors are not getting the support they need to cope with their experiences (Dunigan et al., 2013). Although the referred literature did not include contract interpreters, the results of the current study suggest that the findings from that report could also reflect the LCAs who deployed with the CAF in Afghanistan.

The authors of this paper acknowledge several limitations. The first relates to the sample of participants. Individuals with existing connections to the Afghan-Canadian community recruited all participants for this study. The authors recognize that this method of recruitment may have led to a sampling bias based on the individuals who conducted the outreach however, the authors attempted to minimize this bias by connecting with as many different individuals possible for this recruitment strategy.

A second limitation is the language of the interviews. Although all participants worked as interpreters and could converse in English, English may not have been their first language. Potential language barriers may have influenced the responses shared during the interview.

A final limitation of the study is the small sample size (n = 6). Nonetheless, the population of interest (Afghan-Canadian LCAs) includes approximately sixty-five individuals (Lick, 2019) in total, meaning that approximately 9% of the total population of interest was represented in this study. Even if the experiences reflected in this paper are limited to a small sample and cannot be considered representative of all former LCAs, they still raise important implications for the availability of supports available for Canadian LCAs, and all Canadian civilian contractors moving forward. Further research with larger samples may be necessary to access the full perspectives of former LCAs, especially to guide future program or policy development, which may lead to other themes and perspectives.

5 Conclusion

This paper expands on the nascent literature on national contract interpreters by presenting an analysis of the experiences of six former Afghan-Canadian LCAs. The results reveal key insights into the experiences and support needs of former Afghan-Canadian LCAs included in the study, offering an in-depth account of their experience before, during and after their service. The results also suggest that the experience of working as an LCA with the Canadian Forces had a considerable impact on participants.

Although the findings may not be representative of all former LCAs, the findings offer important considerations regarding the support available not just to interpreters but to all contractors deployed in conflict-zones more broadly. Given the inevitability of future conflicts and the unique experiences shared by participants, further research is needed on national interpreters from all conflict zones, especially LCAs, in order to identify the optimal resources required to support them throughout their work and their transition back to post-service life.

Data availability statement

The raw data from this study will not be made available as this is a qualitative study based on interviews. The full interview transcripts contain identifiable information and sharing the transcripts would threaten participants’ anonymity.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Ottawa Institute for Mental Health Research. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

J-MM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. VC: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. GD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YF: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. TL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. FH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The Atlas Institute for Veterans and Families is funded by the Veterans Affairs Canada. Views and opinions expressed are solely those of the Atlas Institute and may not reflect the views and opinions of the Government of Canada.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the study’s participants who shared their experiences and made this manuscript possible. As well, the authors wish to thank all members of the advisory group, who dedicated their time and provided their invaluable insights to this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1279906/full#supplementary-material

References

Allen, K., (2012). Interpreting in conflict zones. National Association of judiciary interpreters and translators. Available at: https://najit.org/interpreting-in-conflict-zones/ (Accessed 3 April 2023).

Baigorri-Jalon, J. (2010). “Wars, languages and the role (s) of interpreters” in Les liaisons dangereuses: Langues, traduction, interprétation. eds. H. Awaiss and J. Hardane (Beyrouth: Université Saint-Joseph, Ecole de Traducteurs et d'Interprètes de Beyrouth), 173–204.

Barnardi, E. (2022). “The psychological implications of interpreting in conflict zones. Elements for potential mental-health and self-care training for interpreters” in Interpreter training in conflict and post-conflict scenarios. eds. L. Ruiz Rosendo and M. Todorova (London: Routledge), 197–209.

Bos, G., and Soeters, J. (2006). Interpreters at work: experiences from Dutch and Belgian peace operations. Int Peacekeep 13, 261–268. doi: 10.1080/13533310500437662

Bouchard, S., Baus, O., Bernier, F., and McCreary, D. R. (2010). Selection of key stressors to develop virtual environments for practicing stress management skills with military personnel prior to deployment. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 13, 83–94. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0336

Brewster, M., (2019). The Forgotten: Afghan-Canadian combat advisers seek help and recognition. CBC News. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/afghan-advisers-benefits-1.5347612 (Accessed April 3, 2023).

British Medical Association, (2022). Vicarious trauma: signs and strategies for coping. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/your-wellbeing/vicarious-trauma/vicarious-trauma-signs-and-strategies-for-coping (Accessed 3 April 2023).

Daly, B., and Chovaz, C. J. (2020). Secondary traumatic stress. Am. Ann. Deaf 165, 353–367. doi: 10.1353/aad.2020.0023

Dunigan, M., Farmer, C. M., Burns, R. M., Hawks, A., and Steodji, C. M. (2013). Out of the shadows: The health and wellbeing of private contractors working in conflict environments : Rand Corporation.

Geiling, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Böttche, M., and Stammel, N. (2021). Mental health and work experiences of interpreters in the mental health care of refugees: a systematic review. Front. Psych. 12:710789. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.710789

Geiling, A., Knaevelsrud, C., Böttche, M., and Stammel, N. (2022). Psychological distress, exhaustion, and work-related correlates among interpreters working in refugee care: results of a nationwide online survey in Germany. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 13:2046954. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2022.2046954

Giles, D. (1998). “Conference and simultaneous interpreting” in Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies. ed. M. Baker (New York: Routledge), 40–45.

Government of Canada. (2018). The Canadian Armed Forces legacy in Afghanistan. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/operations/military-operations/recently-completed/canadian-armed-forces-legacy-afghanistan.html (Accessed April 3, 2023).

Guidère, M. (2008). Irak in translation: de l'art de perdre une guerre sans connaître la langue de son adversaire. Paris, France: Éditions Jacob-Duvernet Edn.

Hoedemaekers, I., and Soeters, J. (2009). “Interaction rituals and language mediation during peace missions: experiences from Afghanistan” in Advances in military sociology: Essays in honor of Charles C. Moskos-contributions to conflict management, peace economics and development. ed. G. Caforio, vol. 12 (Bringley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 329–352.

Kelly, M., and Baker, C. (2013). “The multiple roles of military interpreters” in Interpreting the peace: Peace operations, conflict and language in Bosnia-Herzegovina (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 42–61.

Lai, M., and Heydon, G. (2015). Vicarious trauma among interpreters. Int. J. Interpreter Educ. 7, 3–22.

Lick, G., (2019). Letter to DM: findings regarding a civilian injured in Afghanistan. Statement, 18 June 2019. Available at: http://ombudsman.forces.gc.ca/en/ombudsman-news-events-media-letters/letter-to-dm-civilian-afghanistan-june-2019.page (Accessed April 3, 2023).

Méndez Sánchez, V. (2021). “The Spanish “military interpreter”: a practical application in international operations arising from armed conflicts” in Interpreting conflict: a comparative framework. ed. M. Todorova (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 135–154.

Pietkiewicz, I., and Smith, J. A. (2014). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychol. J. 20, 7–14. doi: 10.14691/CPPJ.20.1.7

Rebeira, M., Grootendorst, P., and Coyte, P. (2017). Factors associated with mental health in Canadian veterans. J. Mil. Veteran Fam. Health 3, 41–51. doi: 10.3138/jmvfh.4098

Ruiz Rosendo, L., and Persaud, C. (2016). Interpreters and interpreting in conflict zones and scenarios: a historical perspective. Linguistica Antverp New Series–Themes Transl. Stud. 15, 1–35. doi: 10.52034/lanstts.v15i.428

Ruiz Rosendo, L., and Todorova, M. (Eds.) (2022). Interpreter training in conflict and post-conflict scenarios. London, England: Taylor & Francis.

Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., Afifi, T. O., Stein, M. B., Belik, S. L., Meadows, G., et al. (2007). Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care: findings from a large representative sample of military personnel. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64, 843–852. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.843

Shay, J. (1991). Learning about combat stress from Homer's Iliad. J. Trauma. Stress. 4, 561–579. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490040409

Simkus, K., VanTil, L., and Pedlar, D. (2017). 2017 veteran suicide mortality study. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Government of Canada.

Smith, J. A. (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychol. Health 11, 261–271. doi: 10.1080/08870449608400256

Smith, J. A., and Osborn, M. (2003). “Interpretive phenomenological analysis” in Qualitative psychology: a practical guide to research methods. ed. J. A. Smith (London: Sage), 51–80.

Smith, J. A., and Osborn, M. (2004). “Interpretive phenomenological analysis” in Doing social psychology research. ed. G. M. Blackwell (Blackwell Publishing; British Psychological Society), 229–254.

Smith, J. A., and Shinebourne, P. (2012). “Interpretive phenomenological analysis” in APA handbook of research methods in psychology. eds. H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher, vol. 2. Research designs ed (Washington: American Psychological Association), 73–82.

Snellman, P., (2014). The agency of military interpreters in Finnish crisis management operations, MA, University of Tampere. Available at: https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/95025/GRADU-1394089679.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed April 3, 2023).

Snellman, P. (2016). Constraints on and dimensions of military interpreter neutrality. Linguistica Antverp, New Series–Themes Transl Stud 15, 260–281. doi: 10.52034/lanstts.v15i.391

Tălpaș, M. (2016). Words cut two ways: an overview of the situation of afghan interpreters at the beginning of the 21st century. Linguistica Antverp, New Series–Themes Transl Stud 15, 241–259. doi: 10.52034/lanstts.v0i15.401

Thompson, J. M., Dursun, S., VanTil, L., Heber, A., Kitchen, P., de Boer, C., et al. (2019). Group identity, difficult adjustment to civilian life, and suicidal ideation in Canadian Armed Forces veterans: life after service studies 2016. J Mil Veteran Fam Health 5, 100–114. doi: 10.3138/jmvfh.2018-0038

Thompson, J. M., Lockhart, W., Roach, M. B., Atuel, H., Bélanger, S., Black, T., et al. (2017). Veterans' identities and well-being in transition to civilian life-a resource for policy analysts, program designers, service providers and researchers: Report of the Veterans' identities research theme working group. Charlottetown, PE: Veterans Affairs Canada.

VanTil, L. D., Simkus, K., Rolland-Harris, E., and Pedlar, D. J. (2018). Veteran suicide mortality in Canada from 1976 to 2012. J Mil Veteran Fam Health 4, 110–116. doi: 10.3138/jmvfh.2017-0045

Veterans Affairs Canada (2015). Eligibility for health care programs – canada service veteran. government of canada - director general, policy & research. Available at: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/about-vac/reports-policies-and-legislation/policies/eligibility-health-care-programs-canada-service-veteran (Accessed April 4, 2023).

Veterans Affairs Canada, (2019). Canada remembers: The Canadian Armed Forces in Afghanistan. Available at: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/pdf/cr/pi-sheets/afghanistan-eng.pdf (Accessed April 3, 2023).

Watkins, K., (2014). Deployment stressors: a review of the literature and implications for members of the Canadian Armed Forces. Available at: https://cradpdf.drdc-rddc.gc.ca/PDFS/unc194/p800856_A1b.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2023).

Keywords: Interpreters, veterans, conflict-zone, Afghanistan, language and cultural advisors, LCA

Citation: Mercier J-M, Carmichael V, Dupuis G, Mazhari SAZ, Fatimi Y, Laidler T and Hosseiny F (2024) Experiences of Afghan-Canadian language and cultural advisors who served with Canadian forces abroad: an interpretive phenomenological analysis. Front. Commun. 9:1279906. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1279906

Edited by:

Gülseren Keskin, Ege University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Nesrin Çunkuş Köktaş, Pamukkale University, TürkiyeGülay Taşdemir Yiğitoğlu, Pamukkale University, Türkiye

Barton Buechner, Adler School of Professional Psychology, United States

Copyright © 2024 Mercier, Carmichael, Dupuis, Mazhari, Fatimi, Laidler and Hosseiny. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jean-Michel Mercier, amVhbi1taWNoZWwubWVyY2llckB0aGVyb3lhbC5jYQ==

Jean-Michel Mercier

Jean-Michel Mercier Victoria Carmichael1,2

Victoria Carmichael1,2 Gabrielle Dupuis

Gabrielle Dupuis Tim Laidler

Tim Laidler