- 1Landmark College, Putney, VT, United States

- 2Department of Journalism & Creative Media Industries, College of Media & Communication, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States

Introduction: A rarely studied source of psychological discomfort for mothers is the communication received from medical professionals in the context of pregnancy, childbirth, the postpartum period, and pediatric care. To address this gap, we examined mothers’ recollections of medical communications that influenced their perceived stress levels in the context of good-mother normativity. We also explored how recollections of feedback on mothering in medical settings were associated with internalization of good-mother expectations, maternal burnout, length of motherhood, and feminist self-identification.

Methods: We collected the data through an online survey administered by a company that pre-establishes business relationships with potential survey takers. The survey-takers were 254 self-identified mothers, who answered open-ended questions about their recollections of medical communications related to good-motherhood norms. The participants also completed measures of maternal burnout, internalized good mother expectations, and feminist self-identification, and answered demographic questions such as age, education, number of children, and how long they had been mothers.

Results: Participants who recalled discomfort-inducing medical communications that directly or indirectly referenced motherhood norms reported higher levels of internalized good-mother expectations and maternal burnout. A process model showed that the frequency of recalled medical communications, length of motherhood, and feminist self-identification moderated the relationship between the degree of internalization of good-mother expectations and maternal burnout. A significant association emerged between feminist self-identification and the recalled frequency of interactions with medical professionals that increased mothers’ perceived stress stemming from good-mother normativity.

Discussion: The findings of this study contribute to self-discrepancy theory as it relates to the social construction of mothers’ identities by focusing on whether and how often medical professionals reinforce or challenge good-mother social expectations. Another theoretical contribution of this study is that values and beliefs, such as feminist self-identification, can affect the recall of communications about social norms and are significantly associated with levels of internalized expectations and resulting burnout. In terms of practical implications, our findings suggest that medical professionals should be mindful of how they assess patients through the lens of the good-mother norms and also consider addressing the discomfort stemming from such normativity by asking mothers about their perceptions of social expectations and addressing unrealistic beliefs that aggravate mothers’ sense of self-discrepancy.

Introduction

In 2016, the average US mother spent 25 h a week on paid work, up from 9 h in 1965, and 14 h on childcare, up from 10 h in 1965 (Geiger et al., 2019). These demands on mothers’ time and labor were amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, when the closure of schools and daycares made it more difficult for mothers than fathers to balance their jobs with childcare responsibilities (Igielnik, 2021). As a result, maternal stress levels have risen and, in many cases, remain above pre-pandemic levels (Tchimtchoua Tamo, 2020; Adams et al., 2021).

Many biological and environmental factors contribute to a mother’s stress, defined as an emotional and physiological response to “ascribe[ing] threat-related meaning to experiences that tax or exceed our coping ability” (Gianaros and Wager, 2015, p. 313). However, one overarching source of maternal stress that transcends history and culture is the injunctive norm to be a “good mother.” In recent decades, society has continued to expect mothers to be an untiring source of goodness in a child’s life (Hays, 1996; Johnston and Swanson, 2006; Hendrick, 2016). In this study, we employ self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987) to investigate how disconfirming feedback in the context of the good-mother norm can induce psychological discomfort (i.e., stress). Previous research has linked pressure to conform to social expectations of perfect motherhood to maternal burnout (Meeussen and Van Laar, 2018), which occurs after parenting stress exceeds a certain threshold (Roskam et al., 2017).

What factors exacerbate the pressure to be a good mother? For mothers, psychological discomfort and perceived inadequacy stemming from good-mother normativity can result from interactions with family members, friends, acquaintances, and even strangers (Choi et al., 2005; Gram et al., 2017). A rarely studied (e.g., Amir and Ingram, 2008) source of psychological discomfort in the context of perceived self-discrepancy (Higgins, 1987) is the communication received from medical professionals who interact with mothers during pregnancy, childbirth, the postpartum period, and when providing medical care to children. To address this gap, in this study, we examine mothers’ recollections of medical communications that influenced their perceived stress levels by inducing psychological discomfort related to self-discrepancies in the context of good-mother normativity. We also explore how recollections of receiving confirming or disconfirming feedback in medical settings are associated with several other variables, including internalization of good-mother expectations, maternal burnout, length of motherhood, and feminist self-identification. This knowledge contributes to the growing literature on maternal stress and burnout by considering the role of medical professionals’ interactions with mothers.

Theoretical framework

This study is grounded in self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987), which numerous previous studies have used to study mothers’ self-perception in contrast to self-imposed or socially prescribed expectations and the effects of potential discrepancies on mothers’ emotional well-being (e.g., Liss et al., 2013; Adams et al., 2021; Roskam et al., 2022). The theory posits that individuals’ self-perceived “actual’ selves may not always match their personal “ideal” or “ought” (i.e., socially prescribed) selves, where “ideal” reflects aspiration and “ought” reflects a sense of obligation (Higgins, 1987). Additionally, Higgins (1987) distinguished between two self-standpoints: being judged either by one’s own standards or by the standards of others. In self-discrepancy theory, the combinations of the three self-domains (actual, ideal, and ought) and two self-standpoints (own, other) yield two self-concepts (actual/own and actual/other) and four self-guides (ideal/own, ought/own, ought/other, and ideal/other). Higgins (1987) further argued that not everyone is equally motivated by all four self-guides: “Some may possess only ought self-guides, whereas others may possess only ideal self-guides” (p. 321).

A self-discrepancy is a “chronic” discrepancy between one’s self-concept and the different self-guides, and different types of self-discrepancies produce different emotions (Higgins, 1987, p. 322). More recently, self-discrepancy theory has also been applied to one-time events, such as hookups (Victor, 2012). Especially relevant to mothers appears to be the type of self-discrepancy between actual/own and ought/own, where one judges one’s actual self as falling short, by one’s own judgment, of the perceived expectations of others. Higgins (1987) posits that this discrepancy leads to “guilt, self-contempt, and uneasiness, because these feelings occur when people believe they have transgressed a personally accepted (i.e., legitimate) moral standard” (p. 322). As the literature reviewed below suggests, mothers are highly susceptible to feelings of guilt and worthlessness (e.g., Liss et al., 2013; Hillier, 2020), which correspond to Higgins’s (1987) proposed consequences of the actual/own and ought/own discrepancy. When certain expectations are internalized and become part of the “ideal” self, mothers may also experience actual/own versus ideal/own discrepancy, which leads to dissatisfaction, disappointment, and frustration (Higgins, 1987).

The convergence of these two different self-discrepancies among mothers has been noted by Roskam et al. (2022), who explain it by noting that mothers “would be all the more sensitive to high standards in the field of parenting, which they would appropriate in their personal ideal” (p. 443). This overlap can be explained by the still common essentialist views of motherhood (Maestripieri, 2001) and the persistent gendered nature of parenting, with mothers as the primary caregivers (Craig, 2006; Dunatchik et al., 2021). Gendered expectations lead to self-discrepancies among women in general, resulting in chronic social self-consciousness, which refers to “viewing the self as a social object” (Calogero and Watson, 2009, p. 642). In the following section, we review motherhood expectations, the effects of their internalization, and the relevance of confirming or disconfirming feedback.

Literature review

The good-mother norm

Good mother normativity is distinctly gendered (Garner, 2015), even though it contains many of the more general good parent beliefs, such as caring for and advocating for one’s children (e.g., Weaver et al., 2020). The good mother as a social construct in Western culture has historically been steeped in essentialism, viewing mothering as instinctive and innate (e.g., Maestripieri, 2001), and in dualism: “the loving and terrible mother” (Jung, 2010, p. 16). While what precisely defines good motherhood can change (Thurer, 1994), Schmidt et al. (2023) have reviewed the most recent two decades of research on the subject and identified the following five qualities: (a) being attentive; (b) securing one’s child’s successful development; (c) smoothly integrating employment into mothering; (d) being in control of public performances of motherhood so as to be socially acceptable; and (e) remaining content and happy at all times.

While the core elements of good-mothering expectations are relatively stable, the details are often debated. Rhetorical battles (the so-called “mommy wars”) have been fought over whether a mother should be working outside the home, whether children should receive vaccines, and how vigilant a mother should be (helicopter as opposed to “free-range.”) (Zimmerman et al., 2008; Abetz and Moore, 2018). Additionally, scholars have noted a tendency for mothers to negotiate, to some degree, what defines good motherhood to fit their behaviors and needs better. For example, Christopher (2012) showed that many working mothers viewed making good decisions about their children as being more central to their good-mother identity than spending long hours caring for children. Marshall et al. (2007) described mothers who felt less successful at breastfeeding as less likely to include breastfeeding in their definitions of good motherhood.

The good-mother normativity is at the core of notions such as the “mommy myth,” which refers to idealized motherhood centered around unachievable expectations (Douglas and Michaels, 2005), and “intensive” (Hays, 1996) or “extensive” mothering (Christopher, 2012), which refer to spending unreasonable amounts of time, money, and mental effort on children’s development, extracurricular activities, and education. These notions often lead to internalized and oppressive guilt (O'Reilly, 2021). Although many mothers work for pay, they still must fulfill their mothering duties to perfection, often without community support (O'Reilly, 2021). Intensive mothering is especially difficult for racially marginalized and poor mothers who face discrimination and poverty (Elliott et al., 2015). Thurer (1994) notes: “Our contemporary myth heaps upon the mother so many duties and expectations that to take it seriously would be hazardous to her mental health” (p. xvi). These standards are, nonetheless, used to judge mothers, leading many mothers to judge themselves (Goodwin and Huppatz, 2010) based on their internalization of the good-mother norm (Meeussen and Van Laar, 2018).

Mothers and medical communication

In the context of self-discrepancy theory, Higgins (1987) posits that “disconfirming feedback” will induce discomfort, even when the feedback is intended to disconfirm an attribute perceived as harmful or socially undesirable. Medical communication (and how it is framed) is significant in relation to mothers’ perceived self-discrepancy because medical professionals can deliver confirming or disconfirming feedback. It is important to note that, based on Higgins’s (1987) self-discrepancy framework, disconfirming feedback could be reasonably positive but still result in negative affect. For instance, if mothers believe themselves to be bad or not good enough mothers, a doctor’s attempt to convince them otherwise would be distressing and a source of discomfort.

Mothers communicate with medical professionals not only about their health but also about the health of their children, as mothers have much higher involvement in pediatric appointments than fathers (Cheng et al., 2018). While early well-child visits focus on the infant’s health, many pediatricians interact with the mother to attend to her wellness, for example, by screening for postpartum depression (Gjerdingen and Yawn, 2007). Research on the effects of communication between medical providers and mothers has more often than not focused on the impact of such communication on the children’s rather than the mother’s well-being (e.g., Tates and Meeuwesen, 2001). For example, effective pediatrician-parent communication has been linked to greater adherence to medication regimes and greater patient recall of information from appointments (Nobile and Drotar, 2003).

Although unattainable in the context of most lived realities, the good-mother norm is socially enforced, and “institutional mediators serve a critical role in validating and reinforcing the dominant ideological expectations” of motherhood (Newman and Henderson, 2014, p. 475). One such institutional mediator is the medical establishment, whose discourses reinforce and protect the social status quo (Foucault, 1973). The medical establishment has routinely reinforced good-mother norms by, for example, “translating women’s desperation and rebellion against the constraints of motherhood into the symptoms of disease” (Taylor, 1995, p. 24). Highlighting medical communication’s role in maintaining the good-mother norm, Waitzkin (1989) argued that doctors “increasingly have regulated family life” (p. 223). The recent shift in medical communication styles from being mostly directive and “paternalistic” (Byrne and Long, 1976) toward being more “patient-centered” (Swenson et al., 2004; Taylor, 2009) has not eliminated medical professionals’ potential power to provide disconfirming (and, therefore, distressing) feedback, as posited by self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987). Even patient-centered communication has been found to encourage patients to adapt to, rather than challenge or circumvent, “troubling social conditions” (Waitzkin, 1989, p. 220), indicating a potential for creating or reinforcing actual/own-vs.-ought/other self-discrepancies. Furthermore, many contemporary mothers, especially those who parent alone and have special-needs children, receive little or no support from medical professionals (Beattie, 2009). Low social support, in turn, can interact with mothers’ self-discrepancy to produce dysphoria (Pierce et al., 1999).

Yet, medical professionals’ communication at children’s appointments can also sometimes benefit mothers. For example, a study in north England showed that when mothers were taught technical skills (e.g., measuring the quantity of breastmilk), they were less likely to feel inferior because they had quantifiable explanations for a potentially distressing outcome (Marshall et al., 2007). Furthermore, “supportive [medical] professionals were reported to be a great source of comfort to” the mothers of sons with ADHD in New South Wales, Australia (Wallace, 2005, p. 198). There is no literature, however, about the prevalence of medical communications that addresses the good-mother social construct and the emotional consequences of physicians’ confirming or disconfirming feedback regarding mothers’ perceived self-discrepancies. Distressing (i.e., disconfirming) feedback was described in the questions used in this study as medical communications that increased “stress,” a layperson’s term to refer to experiences of tension or psychological discomfort.

Stress and burnout

One negative occurrence associated with perceived self-discrepancy is parental (maternal) burnout (Roskam et al., 2022), which is mediated by parental (maternal) stress. This term describes the feelings of tension resulting from being a parent (mother) (Meeussen and Van Laar, 2018). Mothers, especially working mothers, routinely feel inadequate and experience guilt (Hillier, 2020). It is important to note that not all parental stress or fatigue, even when it is on the rise, as was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic, results in parental burnout (Mikolajczak and Roskam, 2018; Aguiar et al., 2021). Even as COVID-19 acted as a novel and intense stressor on parents, rates of parental burnout increased only in proportion to the perceived relative increase in parental stress (Kerr et al., 2021). Because parental burnout results from a chronic imbalance between stress-increasing and stress-alleviating factors (Mikolajczak and Roskam, 2018), the literature on parental burnout has established specific Parental Burnout Inventory score thresholds past which parents are evaluated as experiencing parental burnout (Roskam et al., 2017).

The term “burnout,” which emerged in the human resources literature, refers primarily to emotional and/or physical exhaustion (Perlman and Hartman, 1982). Parental burnout is more complex in that it includes not only emotional exhaustion but also emotional distancing from one’s children and a sense of inadequacy or lack of parental accomplishment (e.g., Kawamoto et al., 2018). A study of parental burnout, based on samples that included more mothers than fathers, in 42 countries indicated a strong association between levels of individualism and parental burnout, with the highest average burnout scores observed in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia, and the highest prevalence of burnout (about 8%) observed in the United States and Poland (Roskam et al., 2021). Outside of Western countries, the prevalence of parental burnout is generally lower — as low as under 1% in countries such as Cuba, Cameroon, Pakistan, Serbia, Thailand, Turkey, and Uruguay (Roskam et al., 2021).

It is also important to note that the extensive literature on “parental burnout” includes but does not explicitly denote maternal burnout. Maternal burnout is likely to reflect and result from additional gendered stressors, including but not limited to the good-mother ideal, and from the gendered distribution of childcare and household chores within most families. As Roskam and Mikolajczak (2020) have noted, gender inequality in parenting is well documented, and mothers experience a higher rate of parental burnout, even though fathers have become more invested in child rearing in recent decades. In a study of Portuguese parents, Aguiar et al. (2021) found that, even though fathers’ exhaustion increased more than mothers’ exhaustion throughout the pandemic, mothers’ overall burnout scores were higher than fathers’ scores 2 years into the pandemic [see also van Bakel et al. (2022)]. Although some earlier studies have found approximately equivalent rates of burnout among mothers and fathers, these findings could be explained not by the achievement of gender equality in parenting but rather by fathers’ greater vulnerability to parental demands (Roskam and Mikolajczak, 2020).

Pre-pandemic snapshot surveys in Western Europe suggest that about 20% of all mothers (Séjourné et al., 2018) and up to 44% of mothers of chronically ill children (Lindström et al., 2010) are affected by maternal burnout at a given time. Like parental burnout, maternal burnout generally results from prolonged maternal stress, which can reflect factors in the social environment, such as food insecurity (Reesor-Oyer et al., 2021), and internalized external pressures. For instance, mothers’ perceived self-discrepancy and the resulting fear of negative social evaluation predict feelings of shame, a type of psychological discomfort (Liss et al., 2013). To prevent such feelings, mothers may frequently internalize external social expectations and maintain an awareness of them at all times. The degree of resulting burnout may depend on the strategies employed to respond to social expectations. For example, Lin et al. (2021a) found that when parents engaged in positive parenting through “deep acting” (making an effort to genuinely feel warmth toward their children), the resulting burnout was lesser than when they performed “surface acting” to display positivity because of external expectations. Furthermore, in a Western (Belgian) sample, mothers’ investment in developing and maintaining good relationships with others around them, both children and adults, is positively associated with burnout (Lin et al., 2021b). These findings suggest that the more mothers strive to make a good impression on others (e.g., doctors), the more prone to burnout they may be.

Given the reviewed literature, along with recent findings that both perceived self-discrepancy (Roskam et al., 2022) and internalization of good-mother expectations (Meeussen and Van Laar, 2018) are precursors to burnout, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Mothers who recalled receiving stress-increasing (i.e., discomfort-inducing) medical communications will report higher levels of (a) internalized good-mother expectations and (b) maternal burnout compared to mothers who did not recall receiving such communications.

H2: Mothers who recalled receiving stress-decreasing medical communications will report lower levels of (a) internalized good-mother expectations and (b) maternal burnout than mothers who did not recall receiving such medical communications.

H3: The levels of (a) internalized good-mother expectations and (b) maternal burnout will differ among mothers who recalled receiving only stress-reducing medical communications, only stress-increasing medical communications, both, and neither.

Maternal burnout resulting from perceived self-discrepancy (Roskam et al., 2022) could, logically speaking, be alleviated by embracing the feminist notion of the “good enough” mother (Pedersen, 2016). This perspective is illustrated by entertainment narratives, such as movies and television shows, portraying women as “unable or unwilling to conform to the ideology of intensive mothering” in a sympathetic light (Feasey, 2017, p. 7). Despite the growing familiarity with this notion, this rejection of traditional mothering ideology is rooted in a response to the patriarchal institutions (as identified by second-wave feminists), which place the burden of child-bearing and-rearing squarely on the shoulders of individual women [for a review of these arguments, see DiQuinzio (1999)]. The feminist popularization of the “good enough mother” concept emphasized the needs of the mother, with Gardiner (1983) insisting that the good-enough-mother model “must be able to account for women’s full and diverse experiences as mothers, daughters, sexual beings, speakers, thinkers, and workers” [p. 737; see also Green (2015) and Silva (1996)]. This conceptualization contrasted Winnicott’s (1953) initial use of the phrase, which viewed a mother’s “failure” as something she was supposed to do, with precise and fine-tuned intuition, but only to facilitate her child’s development: “the good enough mother … starts off with an almost complete adaptation to her infant’s needs, and as time proceeds, she adapts less and less completely, gradually, according to the infant’s growing ability to deal with her failure” (p. 265).

Scholars have noted that the extensive feminist thought on motherhood is rife with contradictions (Snitow, 1992; Corradi, 2021). Some early feminist writers who viewed motherhood as an institution closely linked to the patriarchy have criticized pronatalist pressures on and encouraged recognition of the fulfilled lives of non-mothers (e.g., Firestone, 1970; Peck and Senderowitz, 1974). At the same time, some feminist legal scholars became deeply engaged in defending the legal rights of mothers, such as lesbian women who fought for custody of their children in the 1970s and 1980s (Hunter and Polikoff, 1975) and, more recently, incarcerated mothers (Kennedy, 2011). Other strands of feminist research have centered around Gilligan’s (1982) notion of an ethic of care as it applies to motherhood and mothering (e.g., Timmins, 2019) while also denouncing the unrealistic social expectations for mothers to be ever-smiling, relentlessly energetic, and overinvested in their children’s education and lives (Thurer, 1994; Hays, 1996). Because debates about whether to become a mother and what it means to be a mother have been central to feminist thought for a long time, we expect self-identified feminists to be more likely to notice and recall instances of medical communications that referenced the socially constructed good-mother norm.

Such recognition and recall would be especially likely to occur if the good-mother norm is associated with self-discrepancy. Higgins (1987) argued that “the greater the magnitude and accessibility of a particular type of self-discrepancy possessed by an individual, the more the individual will suffer the kind of the kind of discomfort associated with that type of self-discrepancy” (pp. 335–336). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: There will be an association between feminist self-identification and the frequency of recollected instances of medical communication that (a) increased and (b) decreased one’s stress over being an ideal mother.

Given these findings as well as feminism’s rejection of the socially constructed good-mother norms (e.g., Green, 2015), it is logical to expect that feminist self-identification will be negatively associated with internalized good-mother expectations and maternal burnout. However, although feminism has traditionally emphasized collective over individual actions, recent studies have shown that labeling oneself as a feminist is positively associated with individualism (Liss and Erchull, 2010). As there is a positive association between individualistic beliefs and parental burnout, it is also logical that feminist self-identification could be positively associated with parental burnout.

There is an inconsistency in the literature regarding a potential association between the length of motherhood and burnout. On the one hand, the internalization of expectations across social contexts (such as aging, for example) is a longitudinal process that occurs when the expectations are perceived not as generic social norms but as standards by which one is personally judged (e.g., Damian et al., 2013; Kornadt et al., 2017). Rubin (1984) has also argued that “maternal role attainment” begins with pregnancy and continues after a child is born. Considering (a) the need for a significant passage of time before internalization occurs and (b) the role internalization of good-mother norms plays in maternal burnout (Meeussen and Van Laar, 2018), it would be logical to expect that length of motherhood is positively associated with internalization of good-mother beliefs and burnout. On the other hand, parental burnout is more prevalent among mothers of young children, who have a relatively shorter length of motherhood than parents of older children (e.g., Mikolajczak et al., 2018).

To reconcile some of these contradictions and understand the complex relationships between the variables in this study, we pose the following exploratory research question:

RQ1: Which process model best describes the relationships among (a) length of motherhood, (b) frequency of recalled stress-reducing communications, (c) frequency of recalled stress-increasing communications, (d) internalization of good-mother expectations, and (e) maternal burnout?

Method

After receiving approval for the study from our university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), we collected the data through an online survey administered by a company that pre-establishes business relationships with a vast number of potential survey takers across the country with individually contracted forms of compensation, usually gift cards. Survey-takers were screened for motherhood status and for having received professional medical services after becoming mothers. Motherhood status was based on self-identification, including biological, adoptive, step, foster, and trans mothers. Although options beyond the traditional gender binary were provided, all participants self-identified as cisgender women.

Participants

There were 254 participants in the survey. About 11.4% self-identified as LatinX or Hispanic, 6.3% as Asian American/Pacific Islander, 11.4% as Black/African American, 0.4% as members of native/indigenous communities, 66.7% as White, and 3.5% as other. Almost half (48.8%) reported having at least a 2-year college degree. The 25–34 age group was the largest (25.9%), followed by the 35–44 age group (22%), the 55–64 age group (20.8%), and finally the 45–54 age group (11.8%). The remaining participants were younger than 25 or older than 64. The average number of children per participant was 2.42 (SD = 1.48). The participants’ youngest child’s ages ranged from “unborn” to 57 years.

Measures

Medical communication

Two questions asked whether participants recalled ever receiving medical communication that (a) increased and (b) decreased their stress stemming from their awareness of the good-mother social expectations. We used the word “stress” as a layperson’s term to describe the distress or discomfort that Higgins (1987) posited to result from disconfirming feedback in the context of self-discrepancy theory. The specific questions we used were as follows: “Can you remember a time when a medical professional said, wrote, or communicated non-verbally something that helped you feel less stress over being an ideal mom?” and “Can you remember a time when a medical professional said, wrote, or non-verbally communicated to you something that made you feel MORE stress over being an ideal mom?” The possible answers were “yes” and “no”; the resulting variables were nominal and dichotomous. If participants answered “yes,” they were asked how often such communication occurred (1 = almost never; 7 = almost always).

Maternal burnout

We used Meeussen and Van Laar (2018) scale adapted from Roskam et al.’s (2017) parental burnout scale: “I feel emotionally drained by my mother role”; “I sometimes feel as though I am taking care of my child(ren) on autopilot”; “I feel tired when I get up in the morning and have to face another day with my children”; and “I am at the end of my patience at the end of a day with my child(ren)” (1 = not at all, 5 = very much), α = 0.87.

Internalized good-mother expectations

This scale comprised eight items (1 = not at all; 5 = very much), α = 0.80. It combined three scales used by Meeussen and Van Laar (2018). The first subscale measured perceived pressure: “I feel pressured to be ‘perfect’ in my role as a mother” and “My social environment sets very high expectations for me as a mother to live up to” (these items are similar but not the same as items used by Henderson et al. (2016)). Meeussen and Van Laar (2018) originally selected and adapted the six items in the second and third scales from a more extended scale used by Lockwood et al. (2002)‘s study on self-regulatory focus in academic work. The items were as follows: “I am anxious that I will fall short of my responsibilities and obligations as a mother”; “I think about how I can prevent failures as a mother”; and “I focus on avoiding mistakes as a mother”; “I think about how I can realize my hopes, wishes, and aspirations as a mother”; “I focus on achieving positive outcomes as a mother”; and “I think about how I can be a really good mother.” The second and third subscales represent some of the thoughts that mothers may have in regard to preventing failure and achieving success. These items were included to capture the internalization of socially prescribed aspects of life, given that it is possible to notice external pressures without necessarily feeling personally swayed by them. Therefore, these items helped ascertain whether the perceived pressure was internally integrated enough, to the point that the mother noticed a significant amount of mental energy being spent on meeting those pressures.

Feminist self-identification

This nominal variable was based on Myaskovsky and Wittig’s (1997) adaptation of Levonian Morgan’s (1996) measure of feminist self-identification. The respondents selected one of the following: “I do not consider myself a feminist at all and believe that feminists are harmful to family life and undermine relations between men and women”; “I do not consider myself a feminist”; “I agree with some of the objectives of the feminist movement, but do not call myself a feminist”; “I agree with most of the objectives of the feminist movement, but do not call myself a feminist”; “I privately consider myself a feminist, but do not call myself a feminist around others”; “I call myself a feminist around others”; and “I call myself a feminist around others and am currently active in the women’s movement.”

Strategy analyses

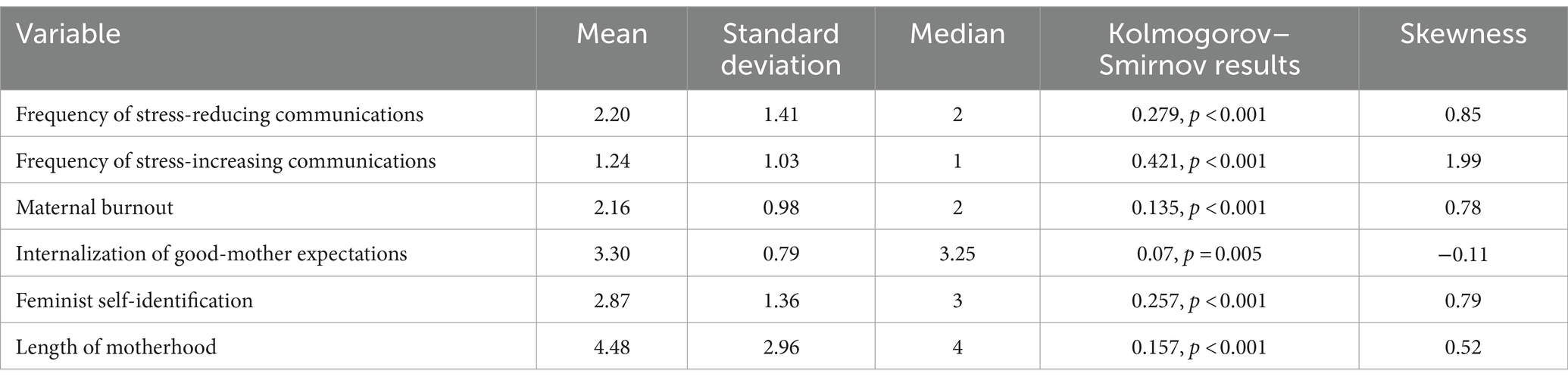

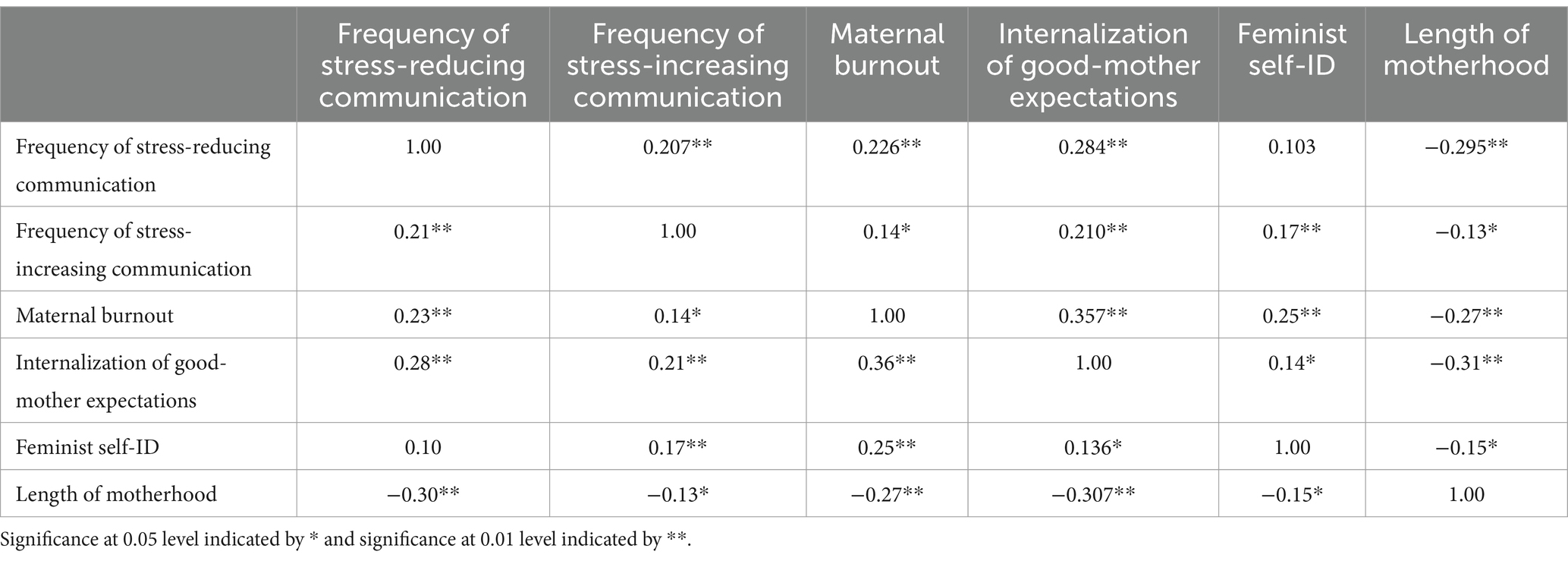

The variables were tested for normality distributions. As Table 1 demonstrates, a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test revealed abnormal distributions on all measures; therefore, the analyses were done with non-parametric statistical tests appropriate for non-normal curved data. A Spearman’s rho correlation was used to determine mothers’ more frequent recollections of good-mother stress-increasing and stress-decreasing medical communications were associated with higher or lower levels of internalized good-mother expectations and maternal burnout. A Spearman’s rho was also used to determine whether the frequency of recalled stress-increasing or stress-decreasing communication was associated with feminist self-identification. A Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to test for differences in the levels of internalized good-mother expectations and maternal burnout among mothers with different kinds of recollections (only stress-increasing, only stress-decreasing, both, and neither). Finally, Hayes’s process models were used to build a cohesive model of the relationships among the main variables. The variables were first assessed according to their relative correlations to determine which of the Hayes models would fit best. Using exploratory methods, such as testing simple mediations and simple moderations, additionally assisted in identifying the best-fit model.

Results

Scales were first tested for reliability, with the internalization-of-good-mother-expectations scale showing a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 and the scale for maternal burnout yielding an alpha of 0.79. Among the participants, 88 (34.65%) recalled only medical communications that decreased their good-mother stress, 22 (8.66%) recalled only communications that increased their good-mother stress, 50 (19.69%) recalled both, and 94 (37.01%) recalled receiving neither kind of communication (see Table 1 for descriptives).

Hypotheses testing

The results showed weak yet significant associations between the frequency of recollections of stress-increasing communications and internalization of good-mother expectations and maternal burnout (Table 2). There was also a significant association between the frequency of recollections of good-mother stress-decreasing communications and levels of internalization of good-mother expectations and maternal burnout, but in the opposite direction as hypothesized. The recollection of stress-decreasing communication being associated with higher, rather than lower, levels of internalization and burnout. H1 was supported; H2 was not supported.

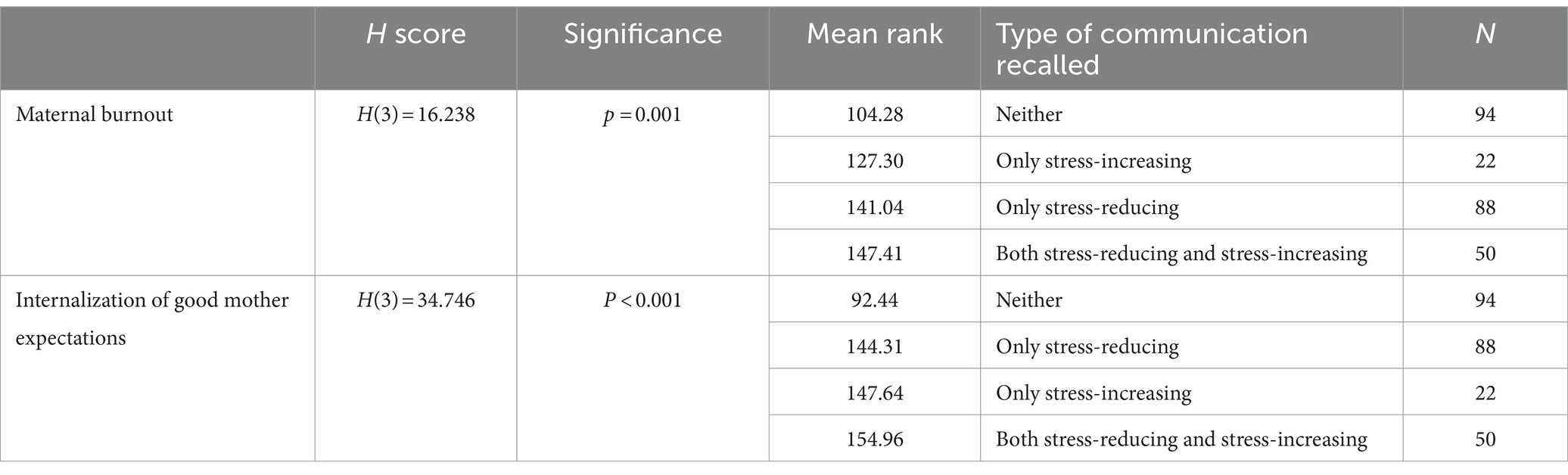

The results also showed that there was a statistically significant difference for both the internalization of good-mother expectations and maternal burnout among mothers who recalled receiving: (a) only stress-decreasing communications; (b) only stress-increasing communications; (c) both types of communications; and (d) neither of these types of communications (Table 3). H3 was supported.

No significant correlation emerged between feminist self-identification and the frequency of recalled stress-decreasing communications, but the correlation was significant for the recalled frequency of stress-increasing communication (Table 2). H4 was partially supported.

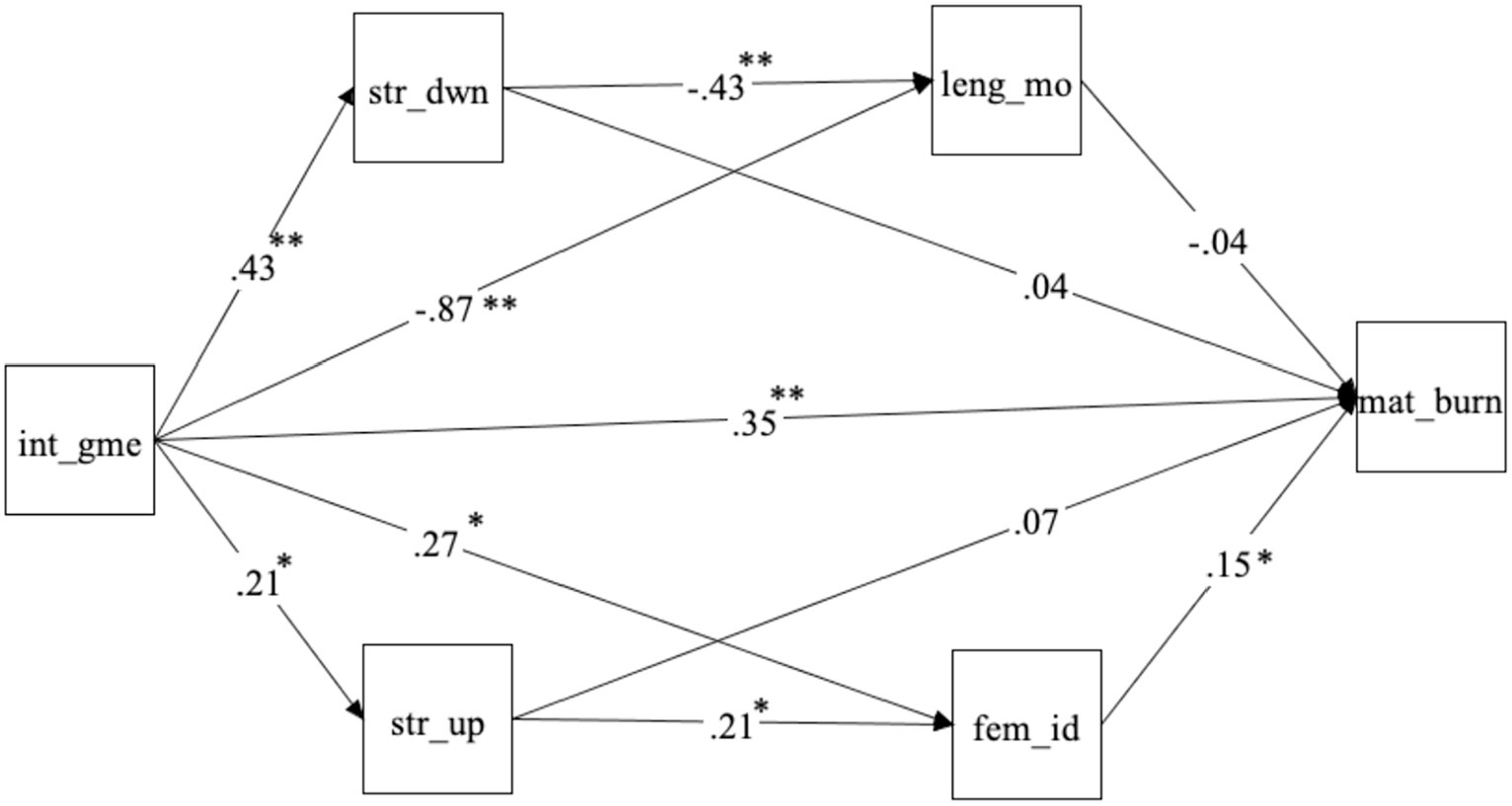

In building a cohesive model of the relationships among the variables, the results showed model 82 [in the PROCESS macro Version 4.0 (Hayes, 2022) percentile bootstrap estimation approach with 5,000] offered the most robust relational explanation of the variables (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Moderation of recalled communications, length of motherhood, and feminist self-identification between internalization of good-mother expectations and maternal burnout. Int_gme, internalization of good-mother expectations; str_dwn, frequency of recalled stress-reducing communications from a medical professional; str_up, frequency of recalled stress-increasing communications from a medical professional; leng_mo, length of motherhood; fem_id, degree of self-identification as a feminist; mat_burn, degree of maternal burnout. Significance at 0.05 or lower indicated by * and significance at 0.001 or lower indicated by **.

Discussion

We investigated the effect of medical communications, as recalled by mothers, in conjunction with several other variables on good-mother stress and maternal burnout. As expected, the reported frequency of stress-inducing medical communication that participants identified as relevant to good-mother norms was positively associated with levels of internalized good-mother expectations (H1a) and maternal burnout (H1b).

Although we expected that participants who recalled receiving positive (stress-decreasing) communication would show lower levels of internalized good-mother expectations (H2a) and lower levels of maternal burnout (H2b), the opposite was true. One possible explanation is that only mothers who were already sensitized to the good-mother norm (as indicated by their higher levels of internalized good-mother expectations) could recall any communication that directly or indirectly referenced such normativity. Such an explanation aligns with existing research showing that familiarity and personal experience are conducive to forming episodic memories (e.g., Poppenk et al., 2010). The findings are also consistent with research showing that memories of events that trigger an emotional response are more easily accessible than memories of events perceived as neutral (e.g., Strongman and Russell, 1986). Participants with higher internalization of good-mother expectations may have assigned more emotional significance to medical communication about these expectations and were more likely to recall such communications. As internalization of good-mother expectations is positively associated with maternal burnout (Meeussen and Van Laar, 2018), these mothers also reported higher burnout.

The results showed significant differences in levels of internalization of good mother expectations (H3a) and burnout (H3b) based on what kinds of medical communications they could recall (none, only stress-increasing, only stress-reducing, or both). Having no memory of a related communication was associated with the highest levels of both internalization of good-mother expectations and burnout, while having a memory of both types of communication was associated with the lowest levels of internalization of good-mother expectations and burnout. Meanwhile, burnout was associated with only stress-increasing memories more than only stress-reducing ones. In contrast, the level of internalization of good-mother expectations showed the opposite, with a greater association with only stress-reducing memories than stress-increasing ones.

Our results also indicated that participants who recalled stress-increasing medical communications identified more strongly with feminism than those who did not remember such communications (H4a). In other words, self-identified feminists appeared more likely to recall communications referencing the good-mother norm challenged by the feminist movement (e.g., Green, 2015), but only if these communications increased their stress (for example, by highlighting their perceived mothering shortcomings). This finding is consistent with the negativity bias theory in psychology (e.g., Ito et al., 1998). There was no significant difference in the strength of feminist self-identification between those who recalled and did not recall stress-decreasing medical communications (H4b). It is important to emphasize that H4 does not establish causality.

The process model highlights how the internalization of good-mother expectations is associated with the frequency of recollection of stress-altering communications, which is, in turn, associated with the degree of feminist self-identification, with the moderated path being less predictive of burnout than the direct path. The model also shows how having received a high frequency of stress-reducing communications removed the significant predictability of maternal burnout from those with higher levels of internalized good-mother expectations which emphasizes the importance of such communications for mothers, particularly younger mothers as the model also shows how the length of motherhood tends to remove significant predictions of burnout as well. The significant decrease in the frequency of stress-reducing communications for older/more experienced mothers may reflect a shift in medical communication models toward a greater degree of patient-centeredness and cognizance of maternal emotional health (Olson et al., 2002; Swenson et al., 2006) such that the younger mothers are receiving more proactive stress-reducing communications. Fortunately for these mothers, time and experience seemed to reduce their internalization of good-mother norms and buffer the difference.

More unexpected was that results indicated the internalization of good-mother expectations was positively associated with feminist self-identification. We can only speculate about the reasons, mainly because a non-repeated survey can establish only associations between variables and not causality. One possible explanation is that mothers with higher internalization of good-mother expectations may be more likely to embrace feminism as a way to modify their expectations or implicitly become a part of a group of like-minded individuals with similar expectations, thereby alleviating what Higgins (1987) described as actual/own and ought/other self-discrepancies. Another possible explanation is that self-identified feminists have not uncritically internalized good-mother expectations but are more likely to be aware of them and experience stress/burnout due to thinking about the inherent unfairness of these norms (Douglas and Michaels, 2005).

Theoretical implications

The findings of this study contribute to self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987) as it relates to the social construction of mothers’ identities by focusing on whether and how often medical professionals reinforce or challenge good-mother social expectations. More than a third of the participants in our sample could not recall any medical communications that altered their stress about good-mother expectations (H3). This finding suggests that while the medical establishment maintains a remarkable capacity as an institutional mediator of stress related to motherhood expectations, such an experience is far from a guarantee for all mothers interacting with medical professionals. It is also possible that communications that directly or indirectly reference good-mother norms are such common occurrences in mothers’ lives that they do not present as unusual events and are, consequently, less likely to be encoded in memory (Davidson, 2006).

Another theoretical contribution of this study is that values and beliefs, such as feminist self-identification, can affect the recall of communications about social norms (H4a) and are significantly associated with levels of internalized expectations and resulting burnout. The self-discrepancy theory has traditionally focused on one’s perceptions of actual and ought selves (Higgins, 1987). Empirical research utilizing the self-discrepancy theory has highlighted self-discrepancies’ adverse psychological outcomes (Liss et al., 2013). However, our findings suggest that values and beliefs that highlight discrepancies between “ought” social arrangements (e.g., gender equality) and “actual” social arrangements (e.g., limited gender equality) cannot be separated from the construction of the self. Future research should expand self-discrepancy theory by investigating how awareness of social-level discrepancies may influence one’s identity.

Practical implications

The results may interest medical professionals seeking to alleviate maternal anxiety and depression, which are associated with poor well-being outcomes for children (e.g., Cummings and Davies, 1994; Glasheen et al., 2010; Goodman et al., 2011). Our results indicate that newer mothers who can recall a higher frequency of stress-reducing communications are less likely to experience maternal burnout suggesting that medical professionals should seek especially to address maternal self-discrepancy in newer mothers, ideally in a confirming way (Higgins, 1987). Medical professionals should be mindful of how they assess patients through the lens of the good-mother norm and consider whether and how it influences their communication with mothers. It is not appropriate for medical professionals to altogether avoid communicating upsetting information because it can be, at times, medically necessary. However, care can still be taken to avoid blaming mothers (Reimer, 2015).

It may be helpful for some medical professionals (or in specific medical settings) to address the good-mother stress directly by asking mothers about their perceptions of social expectations and what areas they feel aggravate their sense of self-discrepancy. Doing so can help medical professionals enact interventions to address any resultant stress/burnout. Prenatal or wellness visits preceding a pregnancy (or adoption/fostering) could be appropriate settings for such conversations. Addressing some of the counterproductive social expectations surrounding motherhood would be akin to employing the inoculation theory of persuasion (McGuire, 1964), which minimizes the effects of expected future persuasive messages by discussing/debunking them in advance. Such an approach would embody the medical industry’s focus on preventative care rather than reactive care and help increase the well-being of both mothers and their families.

Limitations and directions for future research

The findings must be tempered, first and foremost, by this study’s reliance on self-reported memories. Although the literature suggests memories are mostly reliable, precision should not be expected (Brewin et al., 2020). We did take steps to increase accuracy, such as verifying the existence of at least one of each type of memory (stress-reducing and stress-increasing) via open-ended follow-up questions asking respondents to describe the memory(ies). It is possible, however, that the mothers experienced stress-altering communications that they did not recall at all. It is also possible that their recollections of the frequency of such communications were not precise. It is also important to note that fathers and other caretakers may have unique experiences, which remain unexamined here. The sample excluded current adolescent mothers, who may face more real or perceived judgment from medical workers concerning the good-mother social expectations. The participants’ memories’ lack of age and time limit may have partially offset this limitation.

One potential limitation was the inclusion of 42 participants (16.5% of the sample) who reported that their youngest child was 18 or older. However, excluding these participants’ data from the analysis did not produce significantly different results from the original results. It is, therefore, likely that the primary limitations for explaining maternal burnout in terms of length of motherhood (H7) lie in not gathering data about potential confounding variables, such as self-efficacy and level of social support.

The results also suggested that our use of Meeussen and Van Laar (2018) for measuring the internalization of good-mother beliefs may have had some shortcomings. For example, it appears to primarily measure the norms’ interpretations (e.g., “I think about how I can be a really good mother”) and resulting emotions (e.g., “I am anxious that I will fall short of my responsibilities and obligations as a mother”). However, considering how to interpret certain norms and feeling anxious about rising to social expectations is not the same as agreeing with these social norms. Other measures of internalized beliefs include items that more directly assess how strongly one holds a particular view, as illustrated by the Pathogenic Belief Scale (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., 2021), which includes items such as “I believe that I must be perfect in order to feel good about myself” and “I need to defer to others instead of pursuing my own ideas, needs, or interests.” Scholars attempting to measure the internalization of good-mother beliefs in future research should aim to validate a more direct measure, including, for example, modified items from the Pathogenic Belief Scale (e.g., “I believe that I must be a perfect mother in order to feel good about myself”). In future research, scholars could also consider whether there may be different types of norm internalization, which may reflect, for example, the different self-guides described by Higgins (1987).

Scholars interested in good-mother normativity could also investigate what messages medical professionals recall, including in their communications with mothers, and to what (perceived) effects. The findings can help determine whether and to what degree medical workers and mothers agree on what communication is helpful or harmful. Future research should also address other potential variables that affect recollections of good-mother stress-altering communications, such as regulatory focus (Higgins, 1997). A scale, such as the one by Fellner et al. (2007), could measure whether a mother’s overall disposition emphasizes promotion or prevention endeavors.

Data availability statement

The dataset analyzed in the current study is available at: https://osf.io/6x32w/?view_only=092aca01ae59475c8ac1aca0addad864.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Texas Tech University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the survey was conducted online via Qualtrics. Rather than providing an ink signature, the participants read information about the study on their screens and were informed that choosing to continue to the next screen constitutes consent. However, they were free to exit the survey at any time or skip questions they did not wish to answer.

Author contributions

DM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration. MS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Data collection was funded by the first author’s Presidential Fellowship from the Texas Tech University Graduate School. Publication was funded by the Texas Tech University Open-Access Publishing Initiative and the Texas Tech Department of Journalism & Creative Media Industries.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Békés, V., and Prout, T. A. (2021). Grappling with our therapeutic relationship and professional self-doubt during COVID-19: will we use video therapy again? Couns. Psychol. Q. 34, 473–484. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1773404

Abetz, J., and Moore, J. (2018). “Welcome to the mommy wars, ladies”: making sense of the ideology of combative mothering in mommy blogs. Commun. Cult. Crit. 11, 265–281. doi: 10.1093/ccc/tcy008

Adams, E. L., Smith, D., Caccavale, L. J., and Bean, M. K. (2021). Parents are stressed! Patterns of parent stress across COVID-19. Front. Psych. 12:300. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626456

Aguiar, J., Matias, M., Braz, A. C., César, F., Coimbra, S., Gaspar, M. F., et al. (2021). Parental burnout and the COVID-19 pandemic: how Portuguese parents experienced lockdown measures. Fam. Relat. 70, 927–938. doi: 10.1111/fare.12558

Amir, L. H., and Ingram, J. (2008). Health professionals' advice for breastfeeding problems: not good enough! Int. Breastfeed. J. 3:22. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-3-22

Beattie, M. J. (2009). Emotional support for lone mothers following diagnosis of additional needs in their child. Pract. Social Work Action 21, 189–204. doi: 10.1080/09503150903063994

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., and Mickes, L. (2020). Regaining consensus on the reliability of memory. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 29, 121–125. doi: 10.1177/0963721419898122

Byrne, P. S., and Long, B. E. (1976). Doctors talking to patients: a study of the verbal behavior of general practitioners consulting in their surgeries. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Calogero, R. M., and Watson, N. (2009). Self-discrepancy and chronic social self-consciousness: unique and interactive effects of gender and real–ought discrepancy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 46, 642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.008

Cheng, E. R., Downs, S. M., and Carroll, A. E. (2018). Prevalence of depression among fathers at the pediatric well-child care visit. JAMA Pediatr. 172, 882–883. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1505

Choi, P., Henshaw, C., Baker, S., and Tree, J. (2005). Supermum, superwife, supereverything: performing femininity in the transition to motherhood. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 23, 167–180. doi: 10.1080/02646830500129487

Christopher, K. (2012). Extensive mothering: employed mothers’ constructions of the good mother. Gend. Soc. 26, 73–96. doi: 10.1177/08912432114277

Corradi, C. (2021). Motherhood and the contradictions of feminism: appraising claims towards emancipation in the perspective of surrogacy. Curr. Sociol. 69, 158–175. doi: 10.1177/0011392120964910

Craig, L. (2006). Children and the revolution: a time-diary analysis of the impact of motherhood on daily workload. J. Sociol. 42, 125–143. doi: 10.1177/1440783306064942

Cummings, E. M., and Davies, P. T. (1994). Maternal depression and child development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 35, 73–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x

Damian, L. E., Stoeber, J., Negru, O., and Băban, A. (2013). On the development of perfectionism in adolescence: perceived parental expectations predict longitudinal increases in socially prescribed perfectionism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 55, 688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.021

Davidson, D. (2006). “Memory for bizarre and other unusual events: evidence from script research” in Distinctiveness and memory. eds. R. Reed Hunt and J. B. Worthen (New York: Oxford University Press), 157–179.

DiQuinzio, P. (1999). The impossibility of motherhood: feminism, individualism and the problem of mothering. New York: Routledge.

Douglas, S., and Michaels, M. (2005). The mommy myth: The idealization of motherhood and how it has undermined all women. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Dunatchik, A., Gerson, K., Glass, J., Jacobs, J. A., and Stritzel, H. (2021). Gender, parenting, and the rise of remote work during the pandemic: implications for domestic inequality in the United States. Gend. Soc. 35, 194–205. doi: 10.1177/08912432211001301

Elliott, S., Powell, R., and Brenton, J. (2015). Being a good mom: low-income, black single mothers negotiate intensive mothering. J. Fam. Issues 36, 351–370. doi: 10.1177/0192513X13490279

Feasey, R. (2017). Good, bad or just good enough: representations of motherhood and the maternal role on the small screen. Studies Maternal 9:5. doi: 10.16995/sim.234

Fellner, B., Holler, M., Kirchler, E., and Schabmann, A. (2007). Regulatory focus scale (RFS): development of a scale to record dispositional regulatory focus. Swiss J. Psychol. 66, 109–116. doi: 10.1024/1421-0185.66.2.109

Firestone, S. (1970). The dialectic of sex: the case for feminist revolution. New York: William Morrow and Company.

Gardiner, J. K. (1983). Power, desire, and difference: comment on essays from the “signs” special issues on feminist theory. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 8, 733–737. doi: 10.1086/494014

Garner, B. (2015). Mundane mommies and doting daddies: gendered parenting and family museum visits. Qual. Sociol. 38:327. doi: 10.1007/s11133-015-9310-7

Geiger, A. W., Livingston, G., and Bialik, K. (2019). 6 facts about US moms. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center.

Gianaros, P. J., and Wager, T. D. (2015). Brain-body pathways linking psychological stress and physical health. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 24, 313–321. doi: 10.1177/0963721415581476

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Gjerdingen, D. K., and Yawn, B. P. (2007). Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 20, 280–288. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060171

Glasheen, C., Richardson, G. A., and Fabio, A. (2010). A systematic review of the effects of postnatal maternal anxiety on children. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 13, 61–74. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0109-y

Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M. R., Hall, C. M., and Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 14, 1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1

Goodwin, S., and Huppatz, K. (2010). The good mother: contemporary motherhoods in Australia. Sydney, Australia: Sydney University Press.

Gram, M., Hohnen, P., and Pedersen, H. D. (2017). ‘You can’t use this, and you mustn’t do that’: a qualitative study of non-consumption practices among Danish pregnant women and new mothers. J. Consum. Cult. 17, 433–451. doi: 10.1177/1469540516646244

Green, F. J. (2015). Re-conceptualising motherhood: reaching back to move forward. J. Fam. Stud. 21, 196–207. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2015.1086666

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd edition). New York: The Guilford Press.

Henderson, A., Harmon, S., and Newman, H. (2016). The price mothers pay, even when they are not buying it: mental health consequences of idealized motherhood. Sex Roles 74, 512–526. doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0534-5

Hendrick, H. (2016). Narcissistic parenting in an insecure world: a history of parenting culture 1920s to present. Brustol, UK: Policy Press.

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 94, 319–340. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 52, 1280–1300. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280

Hillier, K. M. (2020). Experiences of maternal guilt and intensive mothering ideologies in graduate student mothers, faculty, and sessional instructors. J. Mother. Stud. 5. Available at: https://jourms.org/experiences-of-maternal-guilt-and-intensive-mothering-ideologies-in-graduate-student-mothers-faculty-and-sessional-instructors/.

Hunter, N. D., and Polikoff, N. D. (1975). Custody rights of lesbian mothers: legal theory and litigation strategy. Buffalo Law Rev. 25, 691–733.

Igielnik, R. (2021). A rising share of working parents in the US say it's been difficult to handle child care during the pandemic. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center.

Ito, T. A., Larsen, J. T., Smith, N. K., and Cacioppo, J. T. (1998). Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: the negativity bias in evaluative categorizations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 887–900. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.887

Johnston, D. D., and Swanson, D. H. (2006). Constructing the “good mother”: the experience of mothering ideologies by work status. Sex Roles 54, 509–519. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9021-3

Jung, C. G. (2010). Four archetypes: (from Vol. 9, part 1 of the collected works of CG Jung) [new in paper] (Vol. 597). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University press.

Kawamoto, T., Furutani, K., and Alimardani, M. (2018). Preliminary validation of Japanese version of the parental burnout inventory and its relationship with perfectionism. Front. Psychol. 9:970. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00970

Kennedy, D. A. (2011). The good mother: mothering, feminism, and incarceration. William Mary J. Women Law 18, 161–200.

Kerr, M. L., Fanning, K. A., Huynh, T., Botto, I., and Kim, C. N. (2021). Parents’ self-reported psychological impacts of COVID-19: associations with parental burnout, child behavior, and income. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 46, 1162–1171. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab089

Kornadt, A. E., Voss, P., and Rothermund, K. (2017). Age stereotypes and self-views revisited: patterns of internalization and projection processes across the life span. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 72, gbv099–gbv592. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv099

Levonian Morgan, B. (1996). Putting the feminism into feminism scales: introduction of a Liberal feminist attitude and ideology scale (LFAIS). Sex Roles 34, 359–390. doi: 10.1007/BF01547807

Lin, G. X., Hansotte, L., Szczygieł, D., Meeussen, L., Roskam, I., and Mikolajczak, M. (2021a). Parenting with a smile: display rules, regulatory effort, and parental burnout. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 38, 2701–2721. doi: 10.1177/02654075211019124

Lin, G. X., Roskam, I., and Mikolajczak, M. (2021b). Disentangling the effects of intrapersonal and interpersonal emotional competence on parental burnout. Curr. Psychol. 42, 8718–8721. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02254-w

Lindström, C., Åman, J., and Norberg, A. L. (2010). Increased prevalence of burnout symptoms in parents of chronically ill children. Acta Paediatr. 99, 427–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01586.x

Liss, M., and Erchull, M. J. (2010). Everyone feels empowered: understanding feminist self-labeling. Psychol. Women Q. 34, 85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01544.x

Liss, M., Schiffrin, H. H., and Rizzo, K. M. (2013). Maternal guilt and shame: the role of self-discrepancy and fear of negative evaluation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 22, 1112–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9673-2

Lockwood, P., Jordan, C. H., and Kunda, Z. (2002). Motivation by positive or negative role models: regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 854–864. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.854

Maestripieri, D. (2001). Biological bases of maternal attachment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 10, 79–83. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00120

Marshall, J. L., Godfrey, M., and Renfrew, M. J. (2007). Being a ‘good mother’: managing breastfeeding and merging identities. Soc. Sci. Med. 65, 2147–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.015

McGuire, W. J. (1964). “Inducing resistance to persuasion: some contemporary approaches” in Advances in experimental social psychology. ed. L. Berkowitz , vol. 1 (New York, NY: Academic Press), 191–229.

Meeussen, L., and Van Laar, C. (2018). Feeling pressure to be a perfect mother relates to parental burnout and career ambitions. Front. Psychol. 9:2113. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02113

Mikolajczak, M., Raes, M. E., Avalosse, H., and Roskam, I. (2018). “Exhausted parents: sociodemographic, child-related, parent-related, parenting and family-functioning correlates of parental burnout” in J. Child Fam. Stud. 27, 602–614. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0892-4

Mikolajczak, M., and Roskam, I. (2018). A theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: the balance between risks and resources (BR 2). Front. Psychol. 9:886. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00886

Myaskovsky, L., and Wittig, M. A. (1997). Predictors of feminist social identity among college women. Sex Roles 37, 861–883. doi: 10.1007/BF02936344

Newman, H. D., and Henderson, A. C. (2014). The modern mystique: institutional mediation of hegemonic motherhood. Sociol. Inq. 84, 472–491. doi: 10.1111/soin.12037

Nobile, C., and Drotar, D. (2003). Research on the quality of parent-provider communication pediatric care: implications and recommendations. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 24, 279–290. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200308000-00010

Olson, A. L., Kemper, K. J., Kelleher, K. J., Hammond, C. S., Zuckerman, B. S., and Dietrich, A. J. (2002). Primary care pediatricians’ roles and perceived responsibilities in the identification and management of maternal depression. Pediatrics 110, 1169–1176. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1169

O'Reilly, A. (2021). Matricentric feminism: theory, activism, practice. Ontario, Canada: Demeter Press.

Pedersen, S. (2016). The good, the bad and the ‘good enough’ mother on the UK parenting forum Mumsnet. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 59, 32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2016.09.004

Perlman, B., and Hartman, E. A. (1982). Burnout: summary and future research. Hum. Relat. 35, 283–305. doi: 10.1177/001872678203500402

Pierce, K. M., Strauman, T. J., and Vandell, D. L. (1999). Self-discrepancy, negative life events, and social support in relation to dejection in mothers of infants. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 18, 490–501. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1999.18.4.490

Poppenk, J., McIntosh, A. R., Craik, F. I., and Moscovitch, M. (2010). Past experience modulates the neural mechanisms of episodic memory formation. J. Neurosci. 30, 4707–4716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5466-09.2010

Reesor-Oyer, L., Cepni, A. B., Lee, C. Y., Zhao, X., and Hernandez, D. C. (2021). Disentangling food insecurity and maternal depression: which comes first? Public Health Nutr. 24, 5506–5513. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000434

Roskam, I., Aguiar, J., Akgun, E., Arikan, G., Artavia, M., Avalosse, H., et al. (2021). Parental burnout around the globe: a 42-country study. Affect. Sci. 2, 58–79. doi: 10.1007/s42761-020-00028-4

Roskam, I., and Mikolajczak, M. (2020). Gender differences in the nature, antecedents and consequences of parental burnout. Sex Roles 83, 485–498. doi: 10.1007/s11199-020-01121-5

Roskam, I., Philippot, P., Gallée, L., Verhofstadt, L., Soenens, B., Goodman, A., et al. (2022). I am not the parent I should be: cross-sectional and prospective associations between parental self-discrepancies and parental burnout. Self Identity 21, 430–455. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2021.1939773

Roskam, I., Raes, M. E., and Mikolajczak, M. (2017). Exhausted parents: development and preliminary validation of the parental burnout inventory. Front. Psychol. 8:163. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00163

Rubin, R. (1984). Maternal identity and the maternal experience. Springer 84:1480. doi: 10.1097/00000446-198412000-00030

Schmidt, E. M., Décieux, F., Zartler, U., and Schnor, C. (2023). What makes a good mother? Two decades of research reflecting social norms of motherhood. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 15, 57–77. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12488

Séjourné, N., Sanchez-Rodriguez, R., Leboullenger, A., and Callahan, S. (2018). Maternal burnout: an exploratory study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 36, 276–288. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2018.1437896

Snitow, A. (1992). Feminism and motherhood: an American reading. Fem. Rev. 40, 32–51. doi: 10.1057/fr.1992.4

Strongman, K. T., and Russell, P. N. (1986). Salience of emotion in recall. Bull. Psychon. Soc. 24, 25–27. doi: 10.3758/BF03330493

Swenson, S. L., Buell, S., Zettler, P., White, M., Ruston, D. C., and Lo, B. (2004). Patient-centered communication. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 19, 1069–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30384.x

Swenson, S. L., Zettler, P., and Lo, B. (2006). ‘She gave it her best shot right away’: patient experiences of biomedical and patient-centered communication. Patient Educ. Couns. 61, 200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.019

Tates, K., and Meeuwesen, L. (2001). Doctor–parent–child communication. a review of the literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 52, 839–851. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00193-3

Taylor, V. (1995). Self-labeling and women's mental health: postpartum illness and the reconstruction of motherhood. Sociol. Focus 28, 23–47. doi: 10.1080/00380237.1995.10571037

Taylor, K. (2009). Paternalism, participation and partnership—the evolution of patient centeredness in the consultation. Patient Educ. Couns. 74, 150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.017

Tchimtchoua Tamo, A. R. (2020). An analysis of mother stress before and during COVID-19 pandemic: the case of China. Health Care Women Int. 41, 1349–1362. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2020.1841194

Thurer, S. (1994). The myths of motherhood: How culture reinvents the good mother. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Timmins, J. E. (2019). 'Care' from private concern to public value: a personal and theoretical exploration of motherhood, feminism, and neoliberalism. Women Stud. J. 33, 48–61.

van Bakel, H., Bastiaansen, C., Hall, R., Schwabe, I., Verspeek, E., Gross, J. J., et al. (2022). Parental burnout across the globe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 11, 141–152. doi: 10.1027/2157-3891/a000050

Victor, E. (2012). Mental health and hooking up: a self-discrepancy perspective. New Sch. Psychol. Bull. 9, 24–34. doi: 10.1037/e534932013-004

Waitzkin, H. (1989). A critical theory of medical discourse: ideology, social control, and the processing of social context in medical encounters. J. Health Soc. Behav. 30, 220–239. doi: 10.2307/2137015

Wallace, N. (2005). The perceptions of mothers of sons with ADHD. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 26, 193–199. doi: 10.1002/j.1467-8438.2005.tb00674.x

Weaver, M. S., October, T., Feudtner, C., and Hinds, P. S. (2020). “Good-parent beliefs”: research, concept, and clinical practice. Pediatrics 145:e20194018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4018

Winnicott, D. W. (1953). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena—a study of the first not-me possession. Int. J. Psychoanal. 34, 89–97.

Keywords: motherhood, medical communication, self-discrepancy, feminism, burnout

Citation: Milman D and Sternadori M (2024) Medical communication, internalized “good mother” norms, and feminist self-identification as predictors of maternal burnout. Front. Commun. 9:1265124. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1265124

Edited by:

Anastassia Zabrodskaja, Tallinn University, EstoniaReviewed by:

Consuelo Corradi, Libera Università Maria SS. Assunta, ItalyDouglas Ashwell, Massey University Business School, New Zealand

Copyright © 2024 Milman and Sternadori. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Miglena Sternadori, bWlnbGVuYS5zdGVybmFkb3JpQHR0dS5lZHU=

Daisy Milman

Daisy Milman Miglena Sternadori

Miglena Sternadori