- 1Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), School of Communication, Journalism and Marketing, Palmerston North, New Zealand

- 2Department of Communication, University of South Florida, Florida, FL, United States

This manuscript examines the experiences of Muslims in India with hate on digital platforms. Extant research on Islamophobia on digital platforms offers analyses of the various discourses circulating on digital platforms. This manuscript builds on that research to document the experiences of online hate among Muslims in India based on a survey of 1,056 Muslims conducted by Qualtrics, a panel-based survey company, between November 2021 and December 2021. The findings point to the intersections between white supremacist and Hindutva Alt-Right messages on digital platforms, delineating the fascist threads that form the convergent infrastructures of digital hate. Moreover, they document the extensive exposure of Muslims in India to Islamophobic hate on digital platforms, raising critical questions about their health and wellbeing. The paper wraps up with policy recommendations regarding strategies for addressing online Islamophobic hate on digital platforms.

Introduction

The proliferation and penetration of digital media across the globe over the past two decades have witnessed the accelerated growth of hate content online (Daniels, 2008, 2013; Winiewski et al., 2016; Ganesh, 2018, 2020; Askanius, 2021; McSwiney et al., 2021; Trillò and Shifman, 2021). The affective nature of hate constitutes its virality, shaping the economic model of platform capital, with hate generating revenue streams. For global platform-based corporations, the circulation of hate draws in clicks, shares, and comments, forming the market base that drives the profit framework of these corporations. In other words, hate itself forms a business model. Hate content threatens social cohesion, peace, and democratic processes (George, 2016) and at the same time adversely impacts the overall sense of security of those who are targeted with hate (Bilewicz and Soral, 2020). Hate erodes trust in communities, institutions, and society and thus depletes democracies, with disproportionately adverse impact on communities at the raced, classed, and gendered margins. When uncontrolled, hate leads to growing violence directed at minority communities and can lead to large-scale deaths, including genocide (Schabas, 2017). Salient here is the role of discourses of hate circulated through media infrastructures, including digital infrastructures, in producing fear, anger, and offline violence (Dutta, 2024). Moreover, hate impacts the health and wellbeing of individuals and communities that are targeted, directly affecting mental health as well as impacting chronic health through mediating mechanisms of stress. The effects of hate are multiplied manifold when minorities are the subjects of these targeted attacks, exacerbating the sense of insecurity felt by minorities.

In India, the largest global democracy, the propaganda infrastructures of Hindutva (Sarkar, 1996; Sharma, 2011; Dutta, 2022, 2024), the underlying political ideology of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), continually produce hate, politically profiting from it in securing hegemony. Hindutva discourses on digital platforms are designed to seed, circulate, and exponentially magnify hate, creating perceptions of anxiety among majority Hindus and politically manipulating this anxiety during elections. Hate targeting Indian Muslims, continually marked as the “other,” is seeded, circulated, and reproduced through digital platforms (Banaji, 2018; Banaji et al., 2019; de Souza and Hussain, 2021; Nizaruddin, 2021; Thomas, 2021; Dutta, 2024). Since the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014 and the subsequent electoral victory of the Modi-led BJP in 2019, the hate on digital platforms in India and in the Indian diaspora has grown exponentially. The content of digital hate driven by Hindutva has been directed at India’s religious minorities, Muslims, and Christians, as well as oppressed caste communities (Dalits) (Mirchandani, 2018; Kuehn and Salter, 2020). Of particular significance are the extreme forms of hate that have been directed at Muslims, including calls for the genocide of Indian Muslims issued by Hindutva ideologues in community meetings, processions, events, performances, and on communication infrastructures including digital platforms (Deshmukh, 2021). These digital manifestations of hate are constituted amidst ongoing forms of offline violence targeting Muslims and carried out by Hindutva groups, including organizations such as the Bajrang Dal and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP).

Several published studies and reports by civil society document the scope and volume of the hate content on digital platforms (Amarasingam et al., 2022). In the context of the proliferation of Islamophobia in India, this literature has largely carried out qualitative analyses of Hindutva texts circulated across a range of diverse platforms. However, the literature so far has not explored the experiences of the exposure to the anti-Muslim digital hate among Muslims in India. In this paper, drawing on a survey conducted with n = 1,056 Muslims in India in November and December 2021, we examine the exposure to digital hate among Muslims (Dutta, 2022) through the lens of the culture-centered approach to communication (CCA) (Dutta, 2024). The CCA foregrounds voice infrastructures in communities at the margins, centering lived experiences of communities at the margins in theorizing communicative processes of disenfranchisement and in co-creating resistance against these processes. The findings offer a descriptive framework for understanding the experiences of digital hate among Muslims in India, exploring the implications of the exposure to digital hate, and suggesting strategies for countering the hate. We will note here that December 2021 was marked by the exponential growth of Islamophobic hate rhetoric on digital platforms. The following literature review elucidates the conceptual categories of fear and Islamophobia in the context of the political ideology of Hindutva in India and describes the relevance of the CCA to examine these concepts, before moving on to discussing the role of social media in disseminating hate.

Literature review

The CCA offers a communicative framework for understanding how disenfranchisement is produced through discourse (Dutta, 2008, 2024; Dutta and Basu, 2011). It offers a theoretical register for understanding how hate is mobilized through specific discourses while producing erasures of minority voices and representation in the dominant discursive spaces. It provides a conceptually rich lens to understand what Appadurai calls predatory identities (Appadurai, 2006; Hassan, 2017) or those identities “[whose] social construction and mobilization require the extinction of other, proximate social categories defined as threats to the very existence of some group defined as we” (p. 51). For instance, Appadurai argues that the political ideology of Hindutva in India organizes fear of Muslim minorities by casting them as a threat to nationhood to secure a majority Hindu predatory identity (Hassan, 2017). The communicative act of strengthening the Hindu sense of belonging in India relies on constructing the Muslim as the other with loyalties to either Pakistan or the larger Muslim world. The CCA provides an entry point to interrogate the majoritarian Hindu narratives thriving on constructing the minority other as an obstacle to achieving ethnic singularity, planting seeds of genocide, and initiating communal pogroms. In other words, the critical analysis of the communicative processes of disenfranchisement offered by the CCA explicates the relationship between the symbolic and material markers of violence.

Religion and politics have always been intricately connected in India even though secularism is enshrined in India’s Constitution to reflect a commitment to religious pluralism and non-discrimination (Deshmukh, 2021). Hindutva’s organizing around the creation of India as a Hindu state and mobilization of Indian nationalism on the lines of religious nationalism is aligned with the fascist ideology that works through violent exclusion (Shahzad et al., 2021). One of the prime features of Hindu nationalism, which is central to Hindutva ideology, is to denigrate the Indian religious minorities, especially Muslims, and fuel communal conflicts by inciting discrimination at many levels. The discriminatory practices coupled with widespread communal rhetoric and images position religious minorities as anti-national (Deshmukh, 2021). Religious intolerance has polarized the Indian state, producing violence and anti-Muslim hate campaigns in the country (Shahzad et al., 2021). Similar to the tactics of white supremacists denying agency to people of color, the Hindu Right denigrates minoritized communities based on caste and religion (Truschke, 2022; Dutta, 2024).

The global flow of media, information, and technology plays a crucial role in the consolidation of such discourses around hate, shaping people’s perceptions of local identities by disseminating images, narratives, and symbols (Appadurai, 1995). The complex interplay between political and cultural forces, fueled by the proliferation of media and technology, makes it urgent to make a careful exposition of the nuanced understanding of minoritized identities that are always historically grounded.

Social media has become a significant medium through which hate toward minoritized communities can be rendered viral, increasing their experiences of oppression (Popa-Wyatt, 2023). In particular, certain features of social media—the capacity to identify and label communities with stigmatizing content on a large scale and generate substantial hatred through the rapid spread of virulent content—are instrumental in propagating digital hate. Furthermore, uniformity of content and feed leads people to come together to form a community of hatred. Additionally, frequency of exposure to the content, susceptibility to the intent of the content, and toxicity of the messages are features through which hate is spread and kept alive. To counter such a culture of hate, it is important to think about mechanisms to minimize the visibility of hateful messages and empower vulnerable communities to reduce harm. Then, we describe our method and research design which was co-created in partnership with a community advisory group of Muslims.

Method

This report draws on two different components of a larger study examining the experiences of Muslims with anti-Muslim hate in India and in the Indian diaspora, driven by the conceptual framework of the culture-centered approach (CCA) that seeks to co-create voice infrastructures at the margins (Dutta, 2018). The CCA notes the interplays between discursive erasures and material inequalities that shape the experiences of disenfranchisement, locating experiences with disenfranchisement in communicative inequalities, and the inequalities in the distribution of information and voice resources (Dutta, 2018). It then offers a method for co-creating voice infrastructures at the margins in building conceptual registers for explaining and challenging the processes of marginalization. This project draws on a community advisory group of Muslims (n = 13) at the classed, gendered margins partnering with the research team to co-create a framework for mapping the effects of digital Islamophobia. The research design co-created with the community advisory group offers a framework for developing community-led interventions addressing Islamophobia and for building policy advocacy around the regulation of hate on digital platforms.

The community advisory group developed a framework for the ethnographic work, combined with a survey of Muslims in India. The ethnography that shapes the inductive observations guiding the project involves in-depth interviews (the first author has so far carried out 43 in-depth interviews with Muslims, ranging from 30 min to 90 min in length) and 213 h of online participant observations on digital platforms (Facebook, Twitter,1 WhatsApp, and Reddit). The online participant observations pointed to Islamophobic content, which was analyzed using co-constructive grounded theory, placing the emergent themes in conversation with the conceptual framework of the CCA, exploring the interplays of culture and structure in the production of the marginalizing processes. The advisory group made sense of the findings from the in-depth interviews, which further pointed to Islamophobic hate content for analysis. This iterative process of data gathering and analysis, guided by the advisory group, shaped the crystallization of a conceptual framework. The second author’s knowledge of the political ideology of Hindutva and anti-Muslim hate in India helped confirm the interpretation of the data and fully account for the research context.

The ethnographic insights are complemented by a survey of 1,056 Muslims conducted by Qualtrics, a panel-based survey company. From the panel of participants in the Qualtrics pool, respondents were screened by religion, only selecting those respondents who identified as Muslim. Sampling quotas were matched on the basis of age and gender to be nationally representative. An initial pilot test was carried out with n = 50 respondents before launching the full survey. The data were gathered between November 2021 and December 2021 and were scrubbed after collection. It is worth noting that these months, and particularly the month of December 2021 registered unprecedented levels of hate targeting Muslims on digital platforms in India. The constructs incorporated into the survey were inductively derived from the ethnography and placed in conversation with the published literature on Islamophobia and hate. Participants were asked to respond on a 1 to 7 scale, to the prompt “Please answer the following with [1] being strongly disagree and [7] strongly agree.” The components of the study involving human participants were peer-reviewed and considered low risk by the human ethics guidelines of Massey University, where the first author is a faculty member. For the in-depth interviews, to protect the identity of the participants, the first author secured consent orally. The participants in the survey provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The social media data were accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platforms’ terms of use and all relevant institutional/regional regulations, with the analysis focusing on public posts.

Findings

The anti-Muslim hate on digital platforms reflects the broader political ideology of Hindutva that is rooted in the othering of Muslims. The organizing logic of a monolithic state (rashtra), one people (jati), and a monolithic culture (sanskriti) forms the ideological apparatus of Hindutva. Digital platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, Reddit, and GitHub have hastened the proliferation of anti-Muslim hate that forms the architecture of Hindutva. The digital infrastructure of Hindutva is organized around building disinformation and accelerating the circulation of hate, recruiting more participants into the hate narrative through the amplification of messages. Platforms build and magnify exponentially messages that perpetuate hate. In the context of Hindutva, the narratives of hate are often centered on specific events, policy decisions made by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and dissenting responses to Hindutva.

The production and circulation of hate in Hindutva are intricately interwoven with an ecosystem of hate produced and circulated by white supremacists, drawing upon white supremacist tropes and simultaneously feeding white supremacist tropes. The visual registers created by and circulated in the Hindutva ecosystem draw upon the Islamophobic visuals and narratives of the Alt-Right and simultaneously feed the Alt-Right discursive space. Critical in this intertwined relationship between white supremacy and Hindutva is the organization of hate around the Muslim invader narrative that feeds the ideology of demographic takeover. The violence of both Hindutva and white supremacy terror is legitimized by the production of the Muslim other as a population threat, as a threat to civilizational purity. Consider for instance the memes created around detention camps for Muslims, producing the trope of the illegal Muslim immigrant. The Hindutva adoption of the white supremacist symbol Pepe the Frog depicts the connections and flows between the different discursive registers of Islamophobic hate, drawn together in their anti-Muslim ideology (Daniels, 2017). From the discursive architectures of 4Chan and Reddit boards to white supremacist Twitter spaces to the Hindutva architecture (including Reddit boards and Twitter), Pepe the Frog has gone through multiple transformations rooted in Islamophobic hate, drawing in and amplifying Nazi symbolism.

In its avatar carrying our anti-Muslim violence in the context of Hindutva, Pepe the Frog is a torturing agent, colored saffron, wearing a black uniform, a cap adorned with the “Om” symbol, and a saffron armband with writing in Sanskrit. Note here the incorporation of Nazi images into the Hindutva context to mobilize the hate. The addition of the saffron color (the color that mobilizes the Hindutva hate machine), the Om symbol, and the saffron namabali (list of names of Hindu deities and/or chants) into the Nazi symbolism (Nazi uniform including hat and armband worn by the frog) materialize the threat of violence. The Nazi detention centers are juxtaposed into the landscape of the detention centers for Muslims mobilized by the ruling BJP under the policy frameworks of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register for Citizens (NRC) (more on this later). Nazi symbols and narratives are imported into the Hindutva narrative architecture, converging with the incorporation of these symbols and narratives by the Alt-Right on digital platforms such as Reddit boards and 4Chan (see Woods and Hahner, 2019). It is critical to document here the role of memes, particularly the Pepe the Frog meme in organizing the hate that fed the Trump campaign, with Trump tweeting the Pepe imagery. The power of the meme is shaped by its organic and flexible form, creating an umbrella for a wide array of hate discourses, building registers for placing the hate into mainstream media, and working toward recruiting ever-expanding membership into the hate infrastructure. Digital platforms such as Reddit play critical roles in facilitating the interactions between Hindutva and white supremacy, producing memes that are then circulated and amplified through public social networking sites such as Twitter and Instagram. In the Hindutva discursive ecosystem online, a wide array of actors, from individuals subscribing to the hate ideology to organized groups to platforms of mainstream Hindutva organizations, the mobilization of Nazi imagery by Hindutva speaks both to the Nazi roots of Hindutva as a political ideology and to the intersections between neo-Hindutva (new forms of more violent Hindutva expressed online and offline) and the Alt-Right. Neo-Hindutva takes the Hindutva agenda toward greater extremes in its direct calls for violence. Critical to the production of neo-Hindutva is the participation of upper-caste Hindu, technology/digitally savvy class of software programmers, engineers, information technology students, and professionals who spend long hours on the Internet and are more likely to come across the Alt-Right digital infrastructure. The participants in the Alt-Right hate infrastructure are driven by an ideology of Brahminical caste purity, the performance of grievance (as upper castes) and rage against reservations (the affirmative action system in India to attempt to address historic caste oppression), and their perception of suppression of upper castes, often targeting oppressed caste communities (dalits) with hate, calling for Muslim genocide and using coded language to circulate calls for genocide. Having been radicalized by the Hindutva propaganda network, for the Alt-Right in the Hindutva ecosystem, self-describing themselves as “trads,” direct calls to violence targeting Muslims and dalits are the necessary response to securing upper-caste Hindu supremacy (Jaffri and Barton, 2022). Note for instance that the Bulli Bai app that had auctioned 100 Muslim women—journalists, activists, actresses, politicians, a Radio Jockey, and a pilot by placing their doctored pictures on an App was created by students, almost all of them studying engineering, information science, and/or computing. The explicit uses of and calls to violence, displaying arms, is a key organizing feature of the Hindutva Alt-Right ecosystem that mirrors the white supremacist Alt-Right. Note here that Hindutva Alt-Right “regularly putting out calls to purchase weaponry, and setting up WhatsApp and Telegram channels by which to purchase arms” (Jaffri and Barton, 2022).

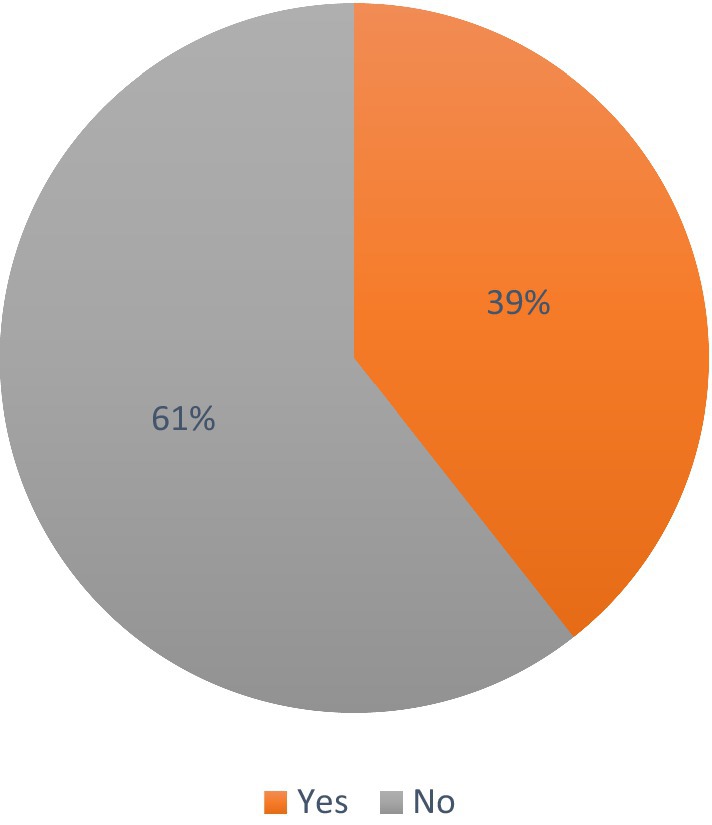

Note in the movement of the Nazi imagery of racial purity that is reproduced in the Alt-Right ecosystem to generate anti-migrant, and specifically anti-Muslim hate, into the Hindutva ecosystem. Note once again the mobilization of Hindutva symbolism, the saffron color, and the Swastika. Critical to the imagery is the mobility of Swastika, speaking directly to the Nazi infrastructure of hate. This is a critical point in the backdrop of the strategy of equivocation deployed by Hindutva groups in India and in the diaspora, claiming that the holy Hindu symbol is distinct from the Nazi symbol, and working through this claim to mobilize for the right to use the holy Hindu symbol in discursive spaces. Also note the modification of the images of the actors in the meme while maintaining the light skin tones of the actors, appealing to the Aryan origin myth. The sexually violent messaging asks Hindu women to “make more Hindu Aryan children.” Muslims are exposed to this hate when participating in digital platforms. In the survey with Muslims, 39 percent of the participants responded that they had been called offensive names as a result of being a Muslim (see Figure 1). This item speaks to the broader discursive infrastructure of hate in India, not differentiated by the communicative spaces where the hate is experienced. It points to an ecosystem where a significant proportion of Muslims are targeted with hate speech.

Figure 1. Percent of Muslims who reported having been called offensive names in the past 12 months as a result of being a Muslim.

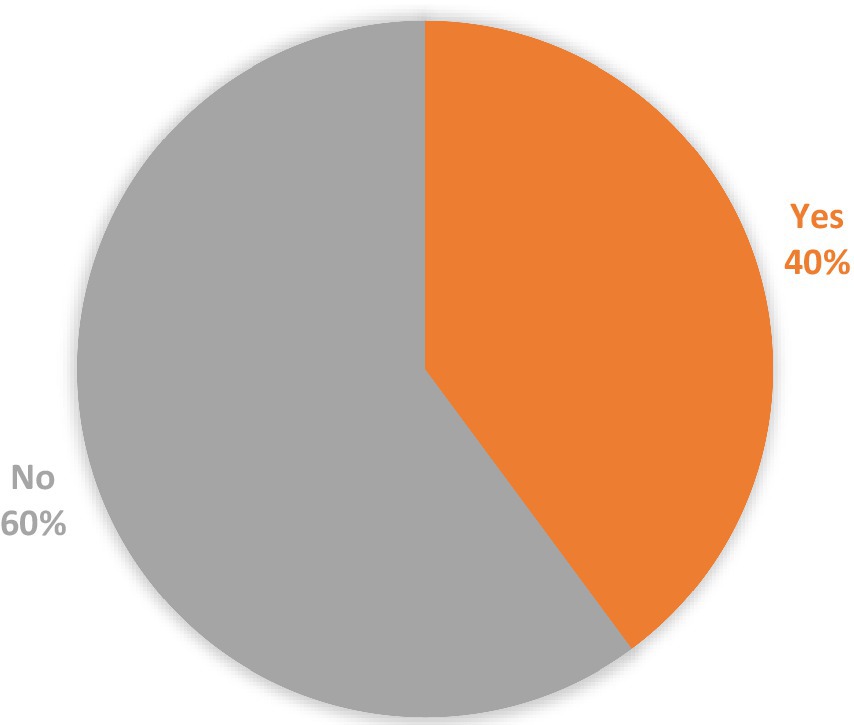

This broader discursive climate of hate speech targeting Muslims plays out on digital platforms (Figure 2). 40 percent of the respondents reported they had been targeted on social media in the past 12 months as a result of being a Muslim. Note here the similarities in the percentages of respondents who reported being called offensive names in the past 12 months and those reporting being targeted on social media for being Muslims in the past 12 months. The feeling of being targeted on digital platforms reported by Muslims is supported by the ethnographic analysis of the online discursive climate that is rife with Islamophobic messages. Particularly salient here are the extreme forms of hate that are directed toward Muslims.

Figure 2. Percent of Muslims who report being targeted on social media in the past 12 months as a result of being a Muslim.

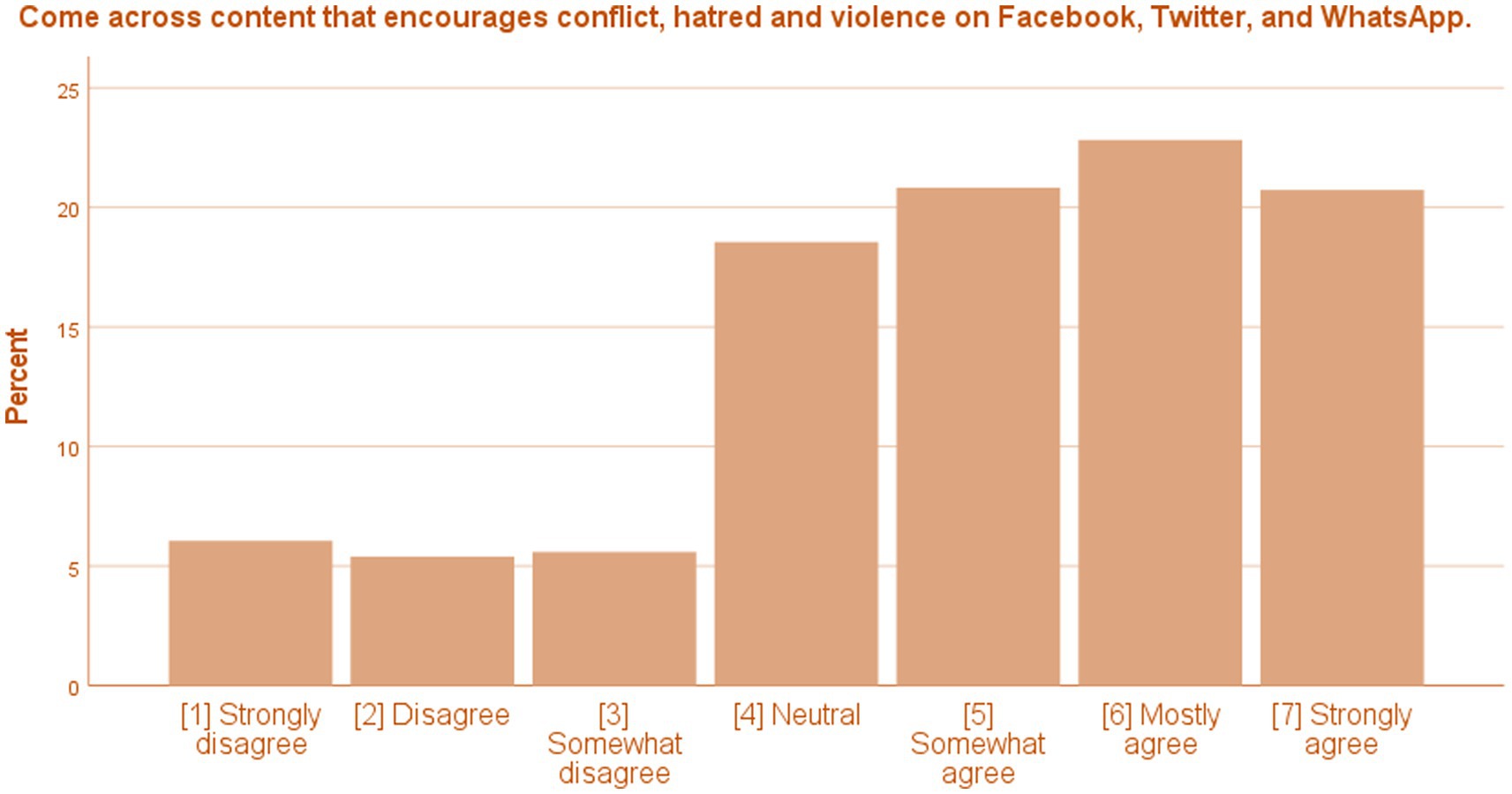

How then does the digital infrastructure targeting Muslims play out in the experiences of Muslims with hate and violence? To what extent is the feeling of being targeted on digital platforms reflected in experiences of coming across content that explicitly promotes hate and violence? The survey item measuring exposure to hate and violence particularly focused on three platforms, Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, as these three platforms were identified by Muslims in the qualitative research as the most prevalent sources of hate; 59 percent of the participants reported coming across content on digital platforms (Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp) that encourages conflict, hatred, and violence.

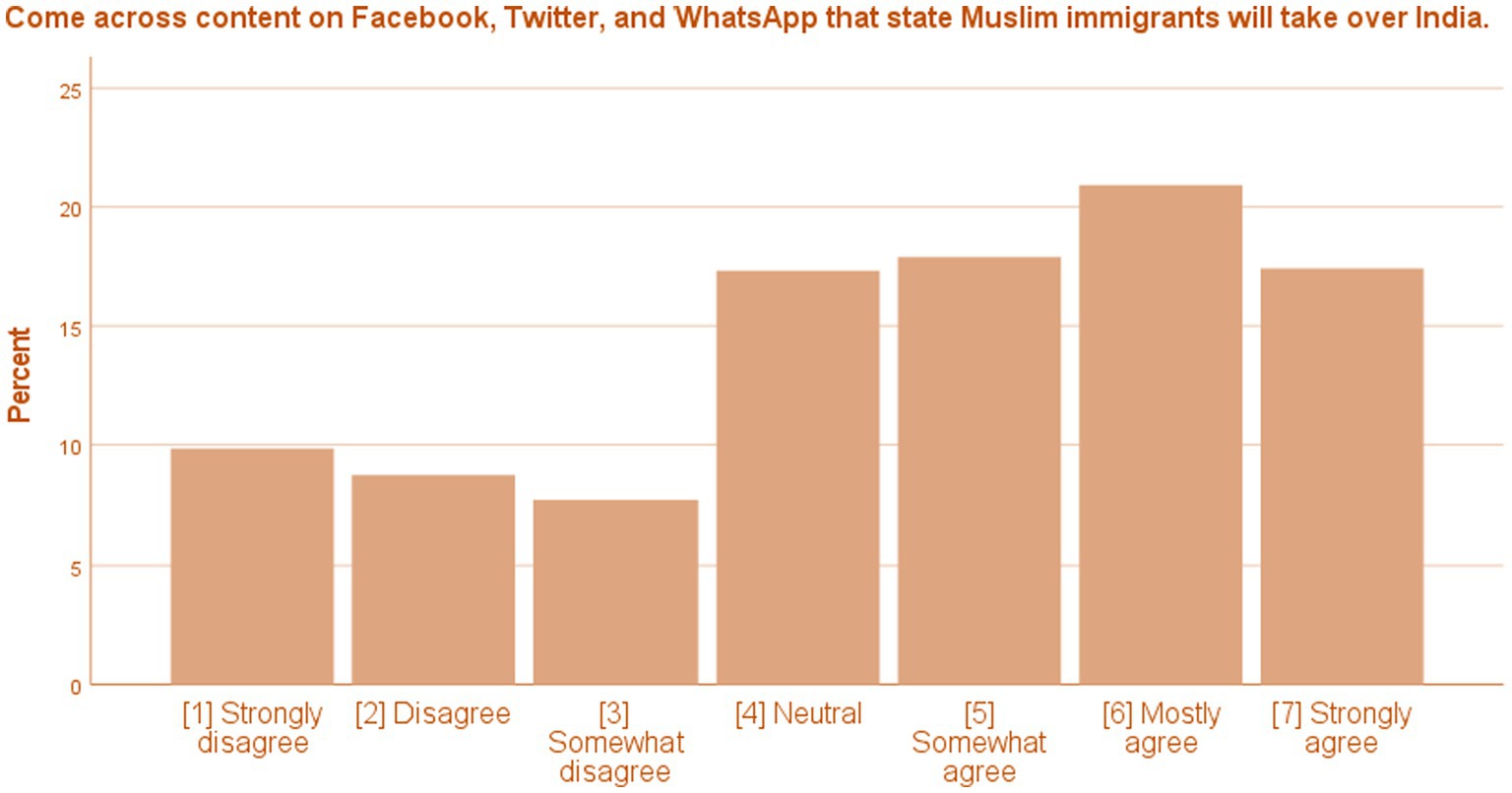

Disenfranchisement and the illegal Muslim migrant

In 2019, the BJP-led central government introduced the National Register for Citizens (NRC) and Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which were widely criticized by civil society as attacks on the citizenship rights of Muslims (Bhat, 2019). The discourses around the NRC and the CAA mobilized anti-immigrant sentiments, with several mainstream Hindutva politicians referring to the citizenship acts as mechanisms to filter out illegal Muslim migrants. Salient in the Hindutva propaganda is the turning of Indian Muslims into illegal immigrants, with the policy framework potentially mobilized in processes that would first mark many Indian Muslims as targets, place them under surveillance, and then screen them out as illegal immigrants. The organizing principle of the CAA/NRC is mobilized to disenfranchise Muslims, giving effect to BJP’s agenda of organizing the nation on the majoritarian principle of a monolithic Hindu jati (race). The process of disenfranchisement through citizenship registers that exclude a minority community is noted as a critical element in the stages of genocide (Stanton, 2020). Reflecting the propaganda infrastructure of Hindutva, the discourse of the Muslim migrant, and particularly the illegal Muslim migrant, has proliferated on digital platforms. The fear of demographic change with takeover by Muslim migrants mirrors “The Great Replacement theory” mobilized by white supremacists. 60 percent of the respondents reported coming across content on digital platforms stating Muslim immigrants will take over India (see Figures 3, 4).

Figure 3. Percent of Muslims who have come across content on digital platforms promoting conflict, hatred, and violence.

Figure 4. Percent of Muslims who have come across content on digital platforms promoting the Great Replacement Theory.

As the protests against the NRC and the CAA gained momentum across India, offline and online hate directed at protestors and minority communities multiplied exponentially. In March 2020 as the COVID-19 cases started appearing in India, COVID-related Islamophobic content proliferated across digital platforms (Banaji and Bhat, 2020); 56.2 percent of the participants reported coming across content on digital platforms (Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp) that stated that Muslim immigrants will take over India. Critical to Hindutva’s narrative of the demographic shift in India orchestrated by Muslims is the political mobilization of hate. In the state of Assam for instance, the narrative of the Miya, referring to Bengali Muslims, and constructing them as illegal Muslim Bangladeshi migrants are integral to the large-scale mobilization of violence as evidenced in the Nellie massacre as well as in the policy framework around the NRC that has been mobilized to disenfranchise largely Bengali Muslims (Basu and Das, 2020).

Jihaad narratives

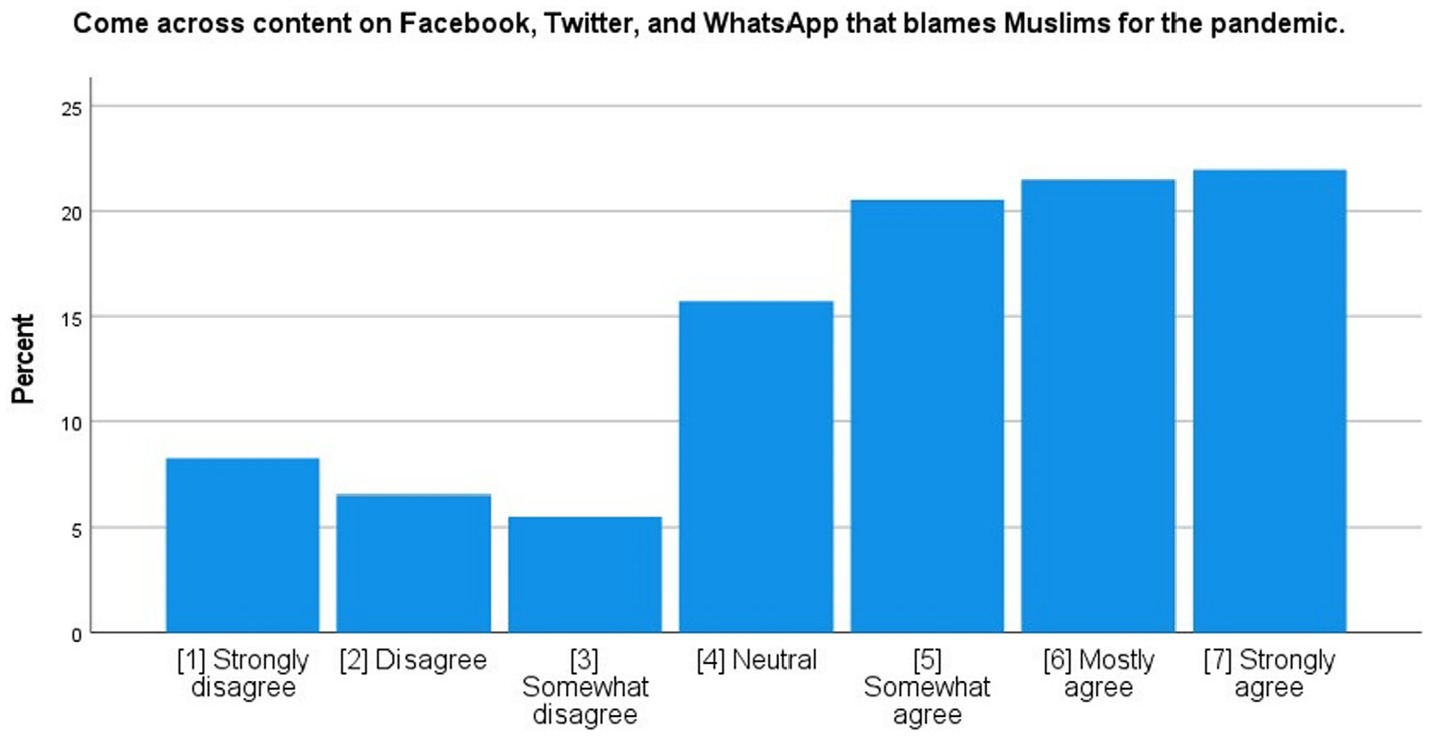

As the NRC/CAA policies were being debated and resisted, amidst the discursive climate of rampant Islamophobia, the COVID-19 outbreak reached India. In the first round of the outbreak, as the lockdown was implemented aggressively, without sufficient notice and adequate planning, a Tablighi Jamaat gathering where Muslims had traveled from various parts of India and internationally emerged as a site of the outbreak. The framing of questions around the intentions of the Tablighi Jamaat gathering in Delhi held prior to the announcement of the lockdown fueled misinformation around Muslim plots to infect Hindus by spitting on food and infiltrating respectable middle-class spaces through their everyday jobs. The #CoronoJihad hashtag, accompanied by images, memes, and videos, projected the Muslims as a terrorist attacking Hindu communities with the COVID-19 bomb (Ghasiya and Sasahara, 2022). The stigmatization and blaming of Muslims as superspreaders based on misinformation resulted in some neighborhoods attacking and banning Muslims (Petersen and Rahman, 2020) and some healthcare organizations denying treatments to Muslims. Mainstream media repeatedly circulated misinformation, claiming that Tablighi Jamaat members were coronavirus “superspreaders.” This disinformation fed and complemented the disinformation spread on digital platforms, with hashtags such as “coronaJihad,” “CoronaTerrorism,” and “CoronaBombsTablighi” trending on Twitter in India.

The Islamophobia around COVID-19 circulated on digital spaces translates to exposure to anti-Muslim rhetoric around COVID-19 reported by Muslims; 64% of the respondents in the survey reported coming across content on digital platforms that blamed Muslims for the pandemic; 20.5% of the participants somewhat agreed, 21.5% of the participants mostly agreed, and 22% of the participants strongly agreed with the statement “I have come across content on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp that blames Muslims, suggesting that they are responsible for the spreading of the pandemic” (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Percent of Muslims who have come across content on digital platforms blaming Muslims for the pandemic.

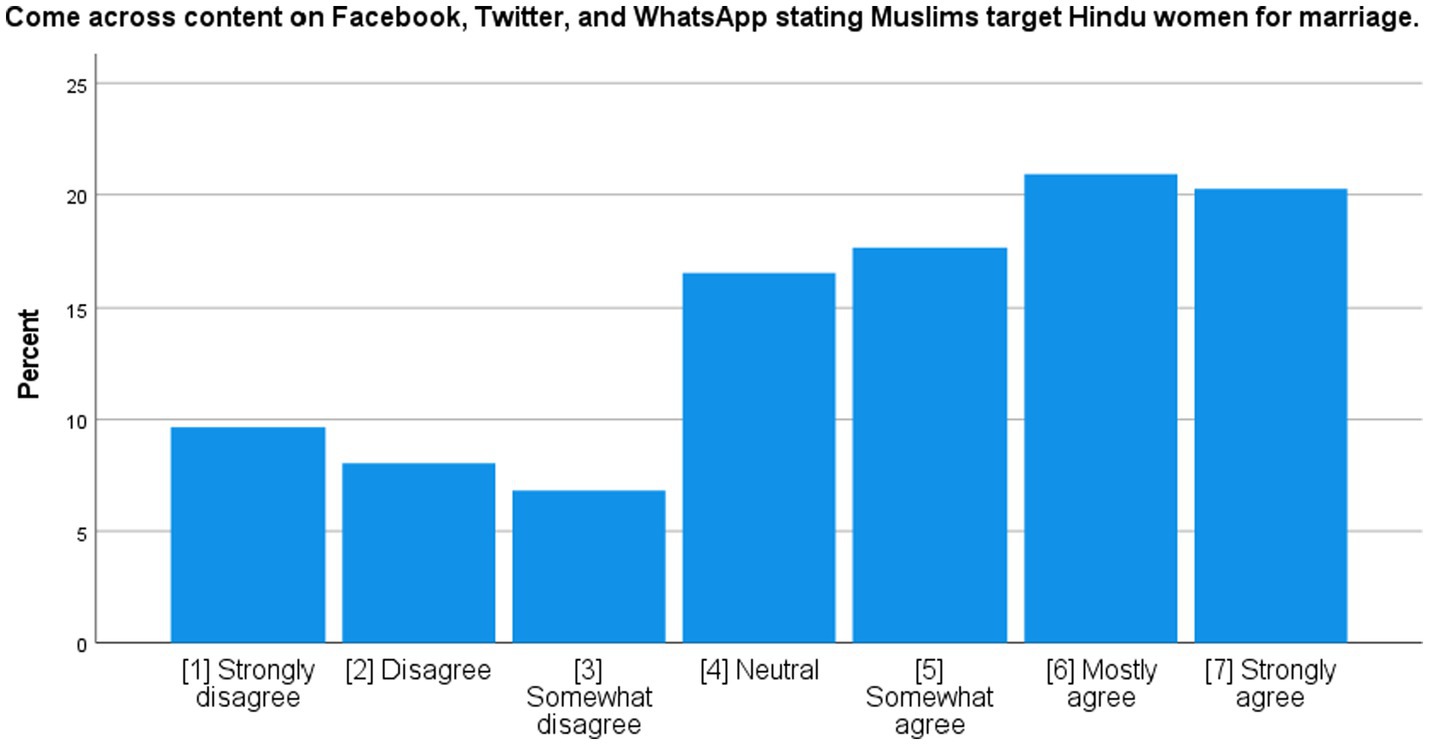

The “Corona Jihad” narrative is part of a broader ecosystem of Islamophobic hate organized around the construction of Jihad. The disinformation portraying Muslims as conspirators plays out in digital content that projects Muslims as targeting Hindu women for conversion through romance (Mankekar, 2021). The hashtag #LoveJihad is part of a broader global Islamophobic digital infrastructure that flows back-and-forth between far-right Hindutva spaces and far-right, white supremacist, anti-immigrant spaces (Zorgati, 2021) in Europe and the Islamophobic discursive space in Myanmar (Frydenlund, 2021). The circulation of the #LoveJihad trope has resulted in violence directed at Muslims, including contributing to the genocide in Myanmar (Frydenlund, 2021). Moreover, the #LoveJihad conspiracy has been legitimized through policy structures pushed by Hindutva.

Muslims in India report coming across this content on digital platforms; 58.9% of the participants agreed that they had come across digital content stating Muslims targeted Hindu women for marriage; 17.7% of the participants indicated they somewhat agreed, 20.9% of the participants stated they mostly agreed, and 20.3% of the participants stated they strongly agreed with the statement, “I have come across content on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp that states Muslims are targeting Hindu women for marriage” (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Percent of Muslims who have come across content on digital platforms with the “Love Jihaad” narrative.

Sexual violence and Muslim women

Against this backdrop of the #LoveJihaad conspiracy narrative, digital platforms are rife with content targeting Muslim women with sexual violence (Nielsen and Nilsen, 2021). This sexually violent content often makes explicit calls for the rape of Muslim women. The graphics in the content are sexually explicit and violent, juxtaposing images of rapes with violent words. The rape of Muslim women is narrated as a religious call for Hindu men.

Note here the wide array of strategies that are outlined for Hindu men to rape Muslim women. The Reddit thread depicted below puts forth 599 laws of the Hindu nation (Rashtra), organized around the rape of Muslim women. The architecture of rape is normalized through various tactics of rape outlined in different settings and contexts. As noted earlier in this manuscript, it is important to note that these rape threats on digital platforms are designed and carried out by largely upper-caste Hindu men and women that are technologically savvy and are often either students or professionals in engineering, information technology, and computing.

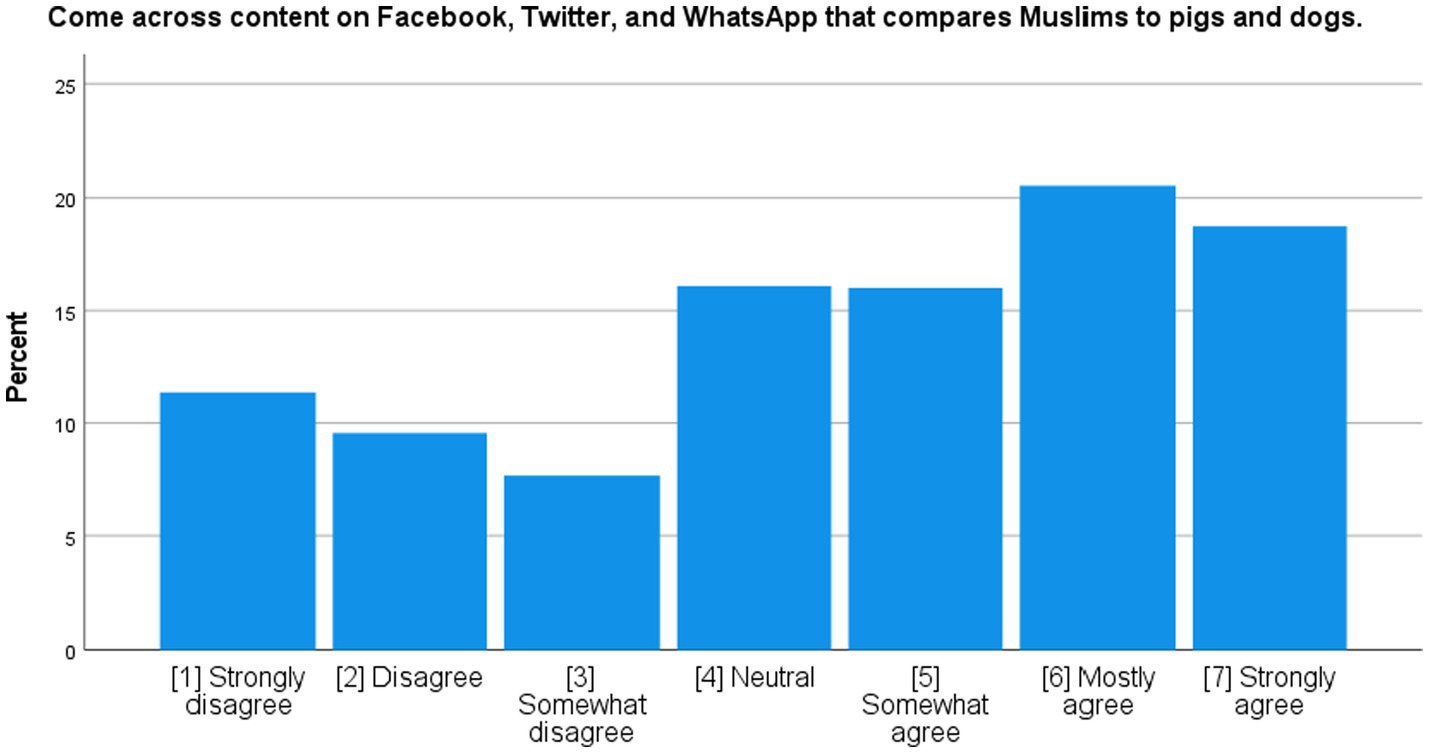

Dehumanizing content

The threats of sexual violence targeting Muslim women are carried out alongside dehumanizing content depicting Muslims as animals. 55.3% of the participants agree with the statement, “I have come across content on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp that compares Muslims to pigs and dogs.” In total, 16% of the participants indicated they somewhat agreed, 20.5% of the participants stated they mostly agreed, and 18.8% of the participants stated they strongly agreed with the statement. Such dehumanizing narratives, portraying a minority community as animals, is a critical step toward genocide (Figures 7, 8).

Figure 8. Percent of Muslims who have come across content on digital platforms inciting violence against Muslims.

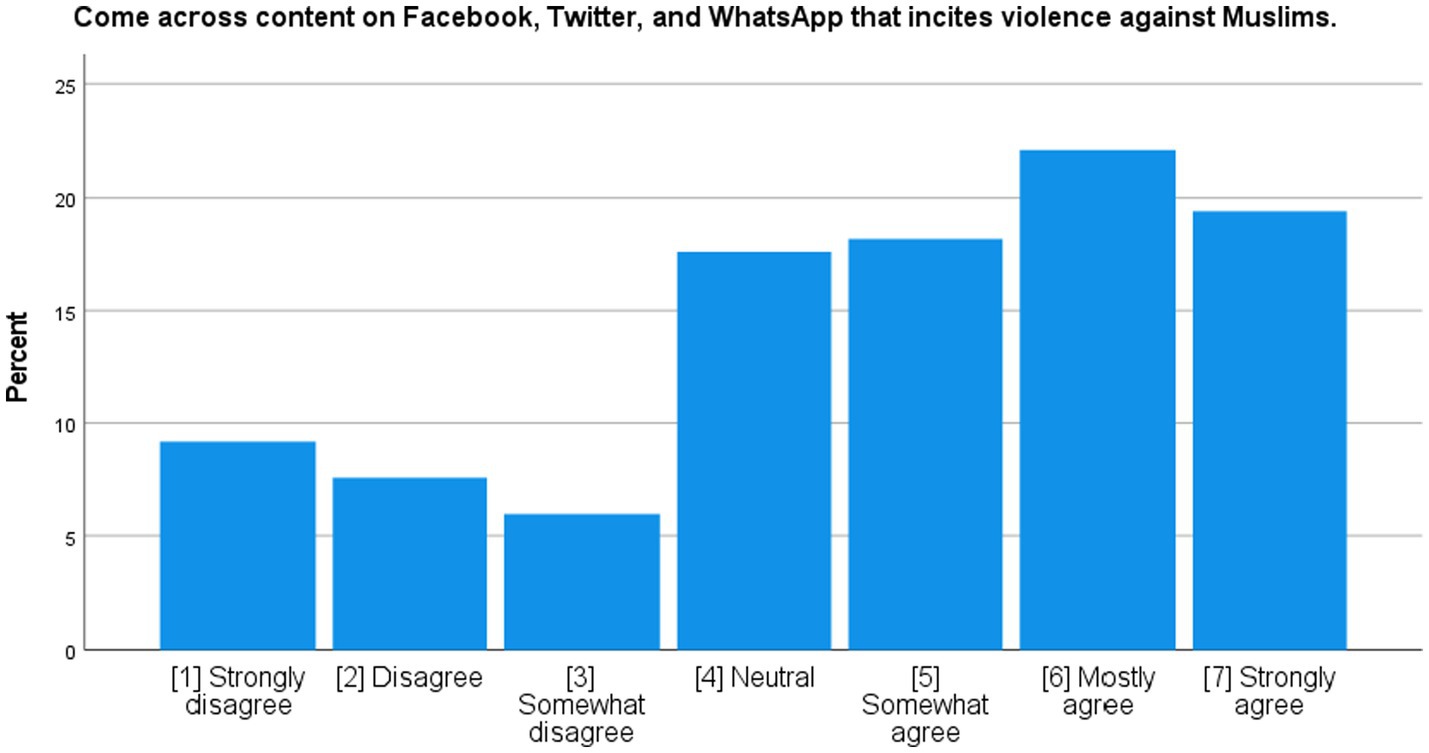

Calls to violence

Dehumanizing discourse is intertwined with calls to violence. The analysis of the digital content depicts explicit acts of violence that are carried out on Muslims. Note here the mobilization of the Alt-Right memes that are directly associated with violence targeting Muslims. The image of Pepe the Frog circulates across digital spaces, mobilized to carry out violence. Pepe the Frog is often depicted in the memes as carrying out the violence. As noted in Pepe the Frog is depicted as a Nazi torturer in a deportation camp. Muslim participants in the survey report exposure to digital content inciting violence against Muslims. 59.7% of the participants agree with the statement, “I have come across content on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp that incites violence against Muslims.” Note in the transformation of Pepe the Frog into a Hindutva symbol, with the saffron skin tone, wearing a saffron tika, and driving over a Muslim. The text states, “Die you m-----f-----.”

Discussion

Although a growing body of literature points to the proliferation of Islamophobic hate in India, the effects of this hate on Muslims remain unexplored (Banaji et al., 2019). This preliminary descriptive analysis offered in this paper fills an important gap in the current understanding of the volume and scope of anti-Muslim digital hate that flows on digital platforms in India. It depicts the flows of anti-Muslim hate across discursive registers, mapping the interpenetrating symbols of Islamophobia across diverse drivers of hate on digital platforms, delineating the discursive linkages between Hindutva Alt-Right and white supremacist Alt-Right. This is to our knowledge one of the first studies examining Muslim experiences of exposure to Islamophobic hate online. The Islamophobic content of Hindutva hate on digital platforms converges with and draws from Islamophobic hate seeded and circulated by white supremacy (Banaji, 2018). This is one of the first studies to document the convergence and interpenetrating relationship between Hindutva and white supremacist hate, depicting the intertextuality of hate messages, and the power of violence that is enacted through the images and narratives. Hindutva memes copy, locally contextualize, and amplify neo-Nazi memes. Moreover, it is critical to note here how the Islamophobia of Hindutva draws on and connects with white supremacists, and specifically, neo-Nazi narratives of racial purity, intertwined with explicit references to detention centers and genocide.

Given the pernicious effects of white supremacist hate on minority communities, including on Muslims as evidenced with the Christchurch terrorist attack, further research is needed to explore the intersections of violence among diverse hate groups, and the relationship of online violence with offline violence. Moreover, the findings in this manuscript call for further exploration of the relationship between Hindutva and white supremacy. Here it is noted that the manifesto of Anders Breivik, the white supremacist terrorist in Norway, drew extensively from Hindutva concepts, referring to publications from a Hindutva propaganda infrastructure, the Voice of India (VOI). The VOI universe publishes several authors who form the infrastructure of white supremacist hate and Islamophobia, including Koenraad Elst, David Frawley, Francois Gautier, and Daniel Pipes, pushing forth a discursive ecosystem of Islamophobic hate (Nanda, 2011; Dutta, 2024). We note here the transnational flows of cultural nationalism organized around Islamophobic hate, with the deployment of standardized cultural figures and media platforms such as Pepe the Frog and 4Chan for the articulations of Islamophobia and nationalism (see Dutta, 2024). Note here the convergences in the Islamophobic hate of white supremacy and Hindutva, holding up fascist constructions of racial purity as the basis of organizing the nation. These flows of cultural nationalism depict the interpenetrating linkages among far-right fascist projects and how these diverse forms of extremism intersect, drawing upon each other, sharing audiences, speaking to and amplifying each other, and working to establish a networked infrastructure of transnational Islamophobic hate.

It is worth noting that the themes present in the digital hate content, such as the Nazi detention centers, demographic change, love jihad, and dehumanization are documented in the literature as discourses with genocidal threads. It is also critical to point out that some of the themes such as the love jihad and Corona jihad themes are correlated with offline violence. The explicit calls to the murders of Muslims and genocide in the digital spaces capture the levels of violence that are scripted into the Islamophobic hate emergent from Hindutva. The findings from the online observations offer critical guidelines for communities at the margins to develop both intervention-based and policy advocacy solutions to addressing digital Islamophobia. Some of the key threads of recommendations that have been presented in the form of a white paper are included at the end of this manuscript. Given the power and control held by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India, the community advisory group and global network of activists I have engaged with point to developing global linkages in driving platform regulation on hate. Because the nature of hate is globally networked, the responses to hate must also draw upon globally networked strategies driving platform regulation.

In addition to the in-depth analysis of the themes in digital content, this study draws on a survey with Muslims in India to document self-reported exposure to hate content on digital platforms among Muslims. So far to my knowledge, this is the first study to report from quantitative data based upon a survey with Muslims on their perceptions of online hate. The majority of Muslims participating in this survey report being exposed to digital hate. This raises vital questions regarding the health, wellbeing, sense of security, and safety felt by Muslims in India. Moreover, the findings document the terrorizing nature of the discursive climate created and seeded by Hindutva, with Indian Muslims coming across digital content that is genocidal and threatens violence. Significant in the findings are the exposures to dehumanizing discourses, discourses of jihaad, and discourses inciting violence. A significant proportion of Muslims felt targeted for their faith on digital platforms.

Future scholarship ought to examine the effects of exposure to digital hate on life, health, and democratic participation. One of the limitations of this report is the design and distribution of the survey in English, which limits its reach to a largely English-speaking Muslim audience. Future survey research ought to explore the experiences with digital hate among Muslims in vernacular contexts. Another limitation is the limited timeframe within which the data were gathered, implemented at a time when the genocidal calls were very high. Future research ought to compare the experiences of Muslims with digital hate across different timeframes. Finally, digital hate is networked and spans boundaries. It will be worthwhile to examine the experiences with digital hate among Muslims in the Indian diaspora.

Recommendations

This paper draws on the key tenets of the culture-centered approach to articulate policy-based solutions for implementation, anchored in the voices of communities at the “margins of the margins.” The recommendations offer important points of praxis to reduce harm for communities who face the brunt of the politics of hate. Mitigating the harm of digital hate has become extremely important with people’s increasing reliance on social media for information. The younger generation such as the post-millennials have almost disengaged from traditional news sources (Gentilviso and Aikat, 2019). Scholars have looked into the use of counter-speeches, deconstructing hateful content, as a strategy for harm reduction. Because of the number of interpretations of what constitutes hate speech, counter-speeches are considered to be more effective than censorship to mitigate the harm of hate speech (Baider, 2023). Fostering online activism has also been considered effective in empowering communities. Just as the internet has led to a resurgence of hate, it has also been essential to the rise of social movements and making them visible to each other by creating online social networks (Mina, 2019). This study aims to bring Muslim voices to the conversation on praxis, drawing on the tenets of the CCA (Dutta and Pal, 2020; Dutta, 2024). Across the margins of the Global South, embodied struggles, rooted in land, community, and connection, offer anchors for decolonizing the digital infrastructures of hate (Dutta and Pal, 2020; Dutta et al., 2023). The initial findings were released in the form of a white paper and brought together diaspora Muslim and anti-Hindutva activists in conversation in a panel put together by CARE.2 The white paper formed the basis of media reports in both India and the diaspora (Dutta, 2022). The voices of Muslims in this study offer a register for developing both community-led and policy responses to addressing the hate. The findings of this study, made sense by a community advisory group of Muslims in India and in the Indian diaspora across the globe, offer the basis for the following recommendations.

• Develop a comprehensive framework for monitoring digital hate across platforms, the various themes in hate content, the forms of hate content, and the features of hate content. Operationalize and categorize the different forms of hate content, the levels of hate, and the relationship of the various categories of hate content with the virality of the content.

• Map out the similarities and differences between the different forms of hate content.

• Develop decolonizing registers for countering Islamophobic extremism, building voice infrastructures for Muslim communities to participate in national–global spaces.

• Develop and cultivate grassroots community capacities to critically interrogate and counter hate, particularly anti-Muslim hate.

• Co-create anti-hate pedagogies through the participation of communities at the “margins of the margins” experiencing hate.

• Co-create digital communication strategies that counter disinformation and hate through the participation of communities at the “margins of the margins” experiencing hate. Community voice and participation in creating messages of peace and harmonious co-existence are vital to building and sustaining social cohesion.

• Co-create community literacies and build community capacities for de-platforming hate content.

• Co-create solidarities across anti-hate struggles at the “margins of the margins.”

• Connect across global struggles against hate. Build infrastructures of solidarity between movements challenging white supremacy and movements challenging Hindutva.

• Co-create and sustain interfaith spaces anchored in social justice and led by the voices of communities at the “margins of the margins.” Anchor interfaith dialogs in critical pedagogy that interrogates the workings of power and control in the circulation of hate.

• Advocate globally to create global policy solutions for regulating and addressing hate across diverse marginalized identities.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because given the confidentiality of the interviews, the raw data will not be made available to protect the identity and safety of the participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to TS5KLkR1dHRhQG1hc3NleS5hYy5ueg==.

Ethics statement

The components of the study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Massey University. For the in-depth interviews, to protect the identity of the participants, oral consent was secured. The participants in the survey provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platforms' terms of use and all relevant institutional/regional regulations, with the analysis focusing on public posts.

Author contributions

The authors confirm being joint contributors of this work and have approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is part of a broader culture-centered community-led intervention being carried out by the Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE). Portions of the text have previously been made available online within the following report: Dutta (2022).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1205116/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The name of Twitter is now changed to X.

References

Amarasingam, A., Umar, S., and Desai, S. (2022). “Fight, die, and if required kill”: Hindu nationalism, misinformation, and islamophobia in India. Religions 13:380. doi: 10.3390/rel13050380

Appadurai, A. (1995). “The production of locality” in Counterworks. ed. R. Fardan (London: Routledge), 208–229.

Appadurai, A. (2006). Fear of small numbers: An essay on the geography of anger. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Askanius, T. (2021). On frogs, monkeys, and execution memes: exploring the humor-hate Nexus at the intersection of neo-nazi and alt-right movements in Sweden. Television New Media 22, 147–165. doi: 10.1177/1527476420982234

Baider, F. (2023). Accountability issues, online covert hate speech, and the efficacy of counter-speech. Politics Govern. 11, 249–260. doi: 10.17645/pag.v11i2.6465

Banaji, S. (2018). Vigilante publics: orientalism, modernity and Hindutva fascism in India. Javn. Public 25, 333–350. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2018.1463349

Banaji, S., and Bhat, R. (2020). How anti-Muslim disinformation campaigns in India have surged during COVID-19. London: LSE COVID-19 Blog.

Banaji, S., Bhat, R., Agarwal, A., Passanha, N., and Sadhana Pravin, M. (2019). WhatsApp vigilantes: An exploration of citizen reception and circulation of WhatsApp misinformation linked to mob violence in India. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

Bhat, M. (2019). The constitutional case against the citizenship amendment bill. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 54, 12–14.

Bilewicz, M., and Soral, W. (2020). Hate speech epidemic. The dynamic effects of derogatory language on intergroup relations and political radicalization. Polit. Psychol. 41, 3–33. doi: 10.1111/pops.12670

Daniels, J. (2008). “Race, civil rights, and hate speech in the digital era” in Learning race and ethnicity: Youth and digital media. ed. A. Everett (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 129–154.

Daniels, J. (2013). Race and racism in internet studies: a review and critique. New Media Soc. 15, 695–719. doi: 10.1177/1461444812462849

Daniels, J. (2017). Ctrl+ ALT-RIGHT: reinterpreting our knowledge of white supremacy groups through the lens of street gangs. J. Youth Stud. 21, 1305–1325.

de Souza, R., and Hussain, S. A. (2021). “Howdy Modi!”: Mediatization, Hindutva, and long distance ethnonationalism. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 16, 138–161. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2021.1987505

Deshmukh, J. (2021). Terrorizing Muslims: communal violence and emergence of Hindutva in India. J. Muslim Minority Affairs 41, 317–336. doi: 10.1080/13602004.2021.1943884

Dutta, M. J. (2018). Autoethnography as decolonization, decolonizing autoethnography: resisting to build our homes. Cultural Studies 18, 94–96. doi: 10.1177/1532708617735637

Dutta, M. J. (2022). Experiences of Muslims in India on digital platforms with anti-Muslim hate (No. 13; CARE White Paper Series). Palmerston North: Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), Massey University, 1–21.

Dutta, M. J. (2024). Digital platforms, Hindutva, and disinformation: communicative strategies and the Leicester violence. Commun. Monogr., 1–29. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2024.2339799

Dutta, M. J., and Basu, A. (2011). “Culture, communication, and health: a guiding framework” in The Routledge handbook of health communication (London: Routledge), 346–360.

Dutta, M. J., Mandal, I., and Baskey, P. (2023). “Culture-centered migrant organizing at the margins: resisting hate amidst COVID-19” in Migrants and the COVID-19 pandemic: Communication, inequality, and transformation (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore), 217–235.

Dutta, M. J., and Pal, M. (2020). Theorizing from the global south: dismantling, resisting, and transforming communication theory. Commun. Theory 30, 349–369. doi: 10.1093/ct/qtaa010

Frydenlund, I. (2021). Protecting Buddhist women from Muslim men:“love Jihad” and the rise of islamophobia in Myanmar. Religions 12:1082. doi: 10.3390/rel12121082

Ganesh, B. (2020). Weaponizing white thymos: flows of rage in the online audiences of the alt-right. Cult. Stud. 34, 892–924. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2020.1714687

Gentilviso, C., and Aikat, D. (2019). “Embracing the visual, verbal, and viral media: how post-millenial consumption habits are reshaping the news” in Mediated Millenials studied in media and communication. eds. J. Schulz, L. Robinson, A. Khilnani, J. Baldwin, H. Pait, and A. A. Williams, vol. 19 (Leeds: Emerald).

George, C. (2016). Hate spin: The manufacture of religious offense and its threat to democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ghasiya, P., and Sasahara, K. (2022). Rapid sharing of islamophobic hate on facebook: the case of the tablighi jamaat controversy. Social Media+ Society 8. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1354959/v1

Hassan, B. B. I. (2017). Fear of small numbers: an essay on the geography of anger, Arjun Appadurai. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 9, 225–228. doi: 10.1080/20421338.2017.1308646

Jaffri, A., and Barton, N. (2022). Explained: ‘Trads’ vs ‘Raitas’ and the Inner Workings of India's Alt-Right. The Wire. Available at: https://thewire.in/communalism/genocide-as-pop-culture-inside-the-hindutva-world-of-trads-and-raitas

Kuehn, K. M., and Salter, L. A. (2020). Assessing digital threats to democracy, and workable solutions: a review of the recent literature. Int. J. Commun. 14, 2589–2610.

Mankekar, P. (2021). “Love Jihad,” digital affect, and feminist critique. Fem. Media Stud. 21, 697–701. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2021.1925728

McSwiney, J., Vaughan, M., Heft, A., and Hoffmann, M. (2021). Sharing the hate? Memes and transnationality in the far right’s digital visual culture. Inf. Commun. Soc. 24, 2502–2521. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.1961006

Mina, A. X. (2019). Memes to movements: How the world's most viral media is changing social protest and power. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Mirchandani, M. (2018). Digital hatred, real violence: majoritarian radicalisation and social media in India. ORF Occasional Paper 167, 1–30.

Nanda, M. (2011). Ideological convergences: Hindutva and the Norway massacre. Econ. Polit. Wkly., 61–68.

Nielsen, K. B., and Nilsen, A. G. (2021). Love Jihad and the governance of gender and intimacy in Hindu nationalist statecraft. Religions 12:1068. doi: 10.3390/rel12121068

Nizaruddin, F. (2021). Role of public WhatsApp groups within the Hindutva ecosystem of hate and narratives of “CoronaJihad”. Int. J. Commun. 15, 1102–1119.

Petersen, E. H., and Rahman, A. S. (2020). Coronavirus conspiracy theories targeting Muslims spread in India. Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/13/coronavirus-conspiracy-theories-targeting-muslims-spread-in-india

Popa-Wyatt, M. (2023). Online hate: is hate an infectious disease? Is social media a promoter? J. Appl. Philos. 40, 788–812. doi: 10.1111/japp.12679

Sarkar, S. (1996). Indian nationalism and politics of Hindutva. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Schabas, W. A. (2017). “Hate speech in Rwanda: the road to genocide” in Genocide and human rights (London: Routledge), 231–261.

Shahzad, A., Falki, S. M., and Bilal, A. S. (2021). Transformation of Indian nationalism and ‘Otherization’ of Muslims in India. Margalla Papers 25, 48–58. doi: 10.54690/margallapapers.25.1.50

Stanton, G. H. . (2020). “The Ten Stages of Genocide.” Genocide Watch. Available at: https://www.genocidewatch.com/ten-stages-of-genocide (Accessed August 1, 2020)

Thomas, P. (2021). “Religion, media and culture in India: Hindutva and Hinduism” in Media and religion. eds. S. M. Hoover and N. Echchaibi (Berlin: De Gruyter), 205–218.

Trillò, T., and Shifman, L. (2021). Memetic commemorations: remixing far-right values in digital spheres. Inf. Commun. Soc. 24, 2482–2501. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.1974516

Truschke, A. (2022). Hindu supremacists in a white world. J. Am. Acad. Relig. 90, 805–808. doi: 10.1093/jaarel/lfad027

Winiewski, M., Hansen, K., Bilewicz, M., Soral, W., Świderska, A., and Bulska, D. (2016). Contempt speech, hate speech. Report from research on verbal violence against minority groups. Warsaw: Batory Foundation.

Woods, H. S., and Hahner, L. A. (2019). Make America meme again: The rhetoric of the alt-right. New York: Peter Lang.

Keywords: Hindutva, Islamophobia, digital hate, genocide, India, culture-centered approach, hate

Citation: Dutta MJ and Pal M (2024) Experiences of Muslims in India on digital platforms with anti-Muslim hate: a culture-centered exploration. Front. Commun. 9:1205116. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1205116

Edited by:

Sudeshna Roy, Stephen F. Austin State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Florin Radu, Valahia University of Târgoviște, RomaniaKostas Maronitis, Leeds Trinity University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Dutta and Pal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohan J. Dutta, bS5qLmR1dHRhQG1hc3NleS5hYy5ueg==

Mohan J. Dutta

Mohan J. Dutta Mahuya Pal2

Mahuya Pal2