95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Commun. , 05 October 2023

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1273514

American women are often in the role of being a health advocate, guide, or guardian for family and friends. An examination of gender differences is virtually absent from American-focused health communication literature. I review the topic from an international, professional, and historical perspective and include qualitative data from health communication professional interviews to document and explore this role. Explanatory themes of nature and nurture, as well as collectivism and having the ability to keep track of details, are explored as reasons why women take on these roles to a far greater degree than men. Suggestions for future research are included to encourage more health researchers to add to the academic literature.

The focus of this research is health communication practitioners' views on the unpaid work women do as health advocate in American families. Feminist, cultural, sociological, and psychological concepts are applied to explore the qualitative themes from practitioner interviews. Although the geographic focus of this research is centered in the United States, the topic of women's role in providing health guidance should be an international priority. Very little research has addressed this across the globe, except for Judith Wuest's work in Canada. Just over half of the world's population is female, but the topic of this research impacts nearly every person in the world because women play an essential role in people's health. Whether it be a mother, sister, daughter, aunt, grandmother, or cousin, women are overwhelmingly and naturally drawn to this health-helping role. While this topic is unofficially acknowledged by many academicians and practitioners, research on the topic is scant. The present article is an attempt to begin to fill that gap and encouraging more research into women in the unpaid health advocate, guide, or guardian role.

The American family has changed in many ways over the past several decades and is no longer mostly defined as by dads who work outside the home, moms who primarily work inside the home, and children. Today a “family” is defined by the people who comprise it. They may be married or not, have children or not, be the same gender or not, both work outside the home or not, be extended (i.e., grandparents, aunts, uncles, etc.) or not, and are largely able to define their gender roles how they see fit. Families may not even live under the same roof; our family is who we say they are—the people who love and support us. Further, when I refer to women in this article that includes anyone identifying as a woman, cis-gender, trans-gender, and non-binary alike.

Families contribute to our health in many ways. Parents and guardians teach their children directly and indirectly how to take care of themselves, how to eat healthy, how to navigate the world, and hopefully, how to stay safe and well. Ideally, they support our mental health and help us know how to support others. But families can also be unhealthy, unhelpful, and indirectly teach us negative coping strategies.

Regardless of all these factors, women largely remain health advocates, guides, and/or guardians for the family. Women often take this role on instinctively, having served in that capacity for generations, millennia even. This role has both advantages and disadvantages, and I will cover both to some degree in this article with the goal of making the role more transparent and encouraging more discussion in the literature. To be clear, this doesn't mean there aren't men or non-binary individuals who function as a health advocate for various reasons—it takes a village—but it is time to better understand to what degree there may be a gender difference or imbalance.

The motivation for this article began many years ago while researching various health communication topics but not seeing much, if anything, about this obvious role of women health advocates. While informally talking to other health communicators, professional and academic, nearly everyone agreed with the idea, but few, if any, could point directly to a body of literature. This gap was the opportunity for this research. I will review two key areas that connect to existing academic literature—the processes involved in women caring for family members (Wuest, 1997, 2001; Wuest et al., 2002; Read, 2007) and women's health work viewed through a feminist lens (Gary et al., 1998; Im, 2000; Zimmerman and Hill, 2000). Gary et al. (1998) has written, “The effect on women related to the extended caretaking roles that they perform has not yet been studied adequately” (pp. 146–147). Perhaps some readers will connect this research area under the broader inquiry of mothers' invisible mental labor (Robertson et al., 2019).

Few researchers have examined the topic of women's role as health advocates, but Judith Wuest, a Canadian scholar, has made helpful contributions to the area, though she focuses primarily on women as caretakers (Wuest, 2001; Wuest et al., 2002), an important but narrower research focus. Regardless of the difference in focus, Wuest sheds light on the previously unacknowledged topic of women providing unpaid health care for ill family members (Wuest, 1997, 2001; Wuest et al., 2002; Read, 2007). She provides insights into why women are more likely to care for ill family members, including patriarchal social structures, unquestioned gender roles in our society, and political and/or economic influences (Wuest, 1997, 2001; Wuest et al., 2002; Read, 2007). All these factors are slow to change but investigating them to understand and acknowledge how and why they exist is an important step to see how the division of health labor may be inequitable. Similar to the gender inequities we see in faculty work (Winslow, 2010; O'Meara et al., 2017), it is important to better understand the health-related work that women do within the home.

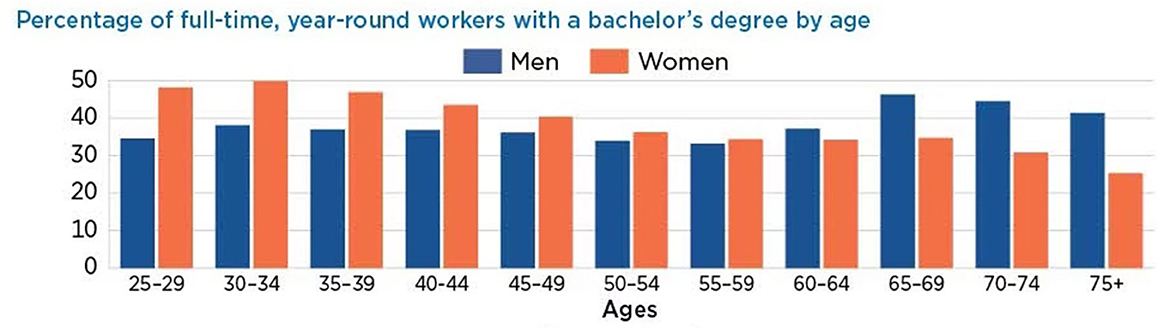

It is important to continue “questioning previously unquestioned societal norms and structures that influence women's health” to understand, acknowledge, and compensate for the contributions that women make inside the home (Wuest et al., 2002, p. 795). Regardless of the increases in working women (see Figure 1), women still tend to serve as principle caregiver across various cultures and, as such, are more often responsible for their own and various family member's health needs (Wuest et al., 2002). Because these roles are socially determined, rather than biologically, they must not be ignored or taken for granted. The demands on women originate both internally and externally from self, partners, children, parents, extended family, and society (Wuest, 1997). These societal structures continue because people with ideals differing from the mainstream tend to be marginalized (Wuest, 1997; Zimmerman and Hill, 2000). Women who maintain the caring ideals reinforce traditional gender roles. Hay et al. reported in a 2019 article Lancet article, “health systems reinforce patients' traditional gender roles and neglect gender inequalities in health” (Hay et al., 2019, p. 2535). They do also share that these inequalities can be disrupted and transformed through community involvement and activism and policy reform.

Figure 1. Gender of American workforce. Public domain image reprinted from U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 American Community Survey (Census.gov).

Despite challenges and improvements, American culture is still dominated by a normed male perspective (Gary et al., 1998; Iacoviello et al., 2022). Both men and women are still commonly stereotyped based on gender roles, often leading to women taking on more responsibility for health-related care. Both men and women would benefit from a shift to more accurately redefine and acknowledge the roles, and responsibilities, that both men and women play in society. Part of this shift would need to address that “(a) gender roles are socially constructed, (b) patriarchal domination of women occurs within families, (c) women's consciousness reflects their caring experiences, … and (e) women are agents of social and political change” (Gary et al., 1998, pp. 142–143). Iacoviello et al. (2022) found “traditional masculinity as being valued by other men but not by society as a whole or by women” (p. 7).

The impact on women taking on multiple roles, inside and outside the home, is uncertain; research has found positive and negative outcomes related to stress (Im, 2000). One thing to consider when reviewing findings is that dominant, male-centered views may impact interpretation. “Gender-based characteristics of women's work have served to exacerbate the exploitation of female labor, ultimately making women's work invisible and devalued” (Im, 2000, p. 108). This is not meant to perpetuate the idea that health care is only women's work, but to make the point of its invisibility in our society. These factors likely impact how we view what is valued as scientific inquiry, hence the paucity of information about women in this role of health guardian.

Though not framed under a feminism, Berg and Woods (2009) provide a thorough discussion of the global impact of caregiving on women's health as they are tied to the United Nations General Assembly's Millennium Development Goals. Key points included:

1. Informal caregiving is a global health issue for women because they serve in that role more than men in nearly every nation, specifically 75% of informal caregivers in the u.s. are women.

2. Social convention demands this work of women, from elders to spouses to children, but men are rarely responsible or accountable for these tasks.

3. Consequences of women's unpaid and unrecognized health work include lost employment-related opportunities, added stress, mental health challenges, reduced personal time, and possible physical consequences, but the latter has received little research attention.

Another way health roles are likely maintained is the strategy used by communication firms, like advertising agencies. Advertising and marketing conduct extensive research about health decisions related to care and products that form consumer market strategy. Although much of this research is proprietary, some is released to mainstream media and helps document the extent of the phenomenon—“~80% of all mothers are responsible for selecting their child's doctor, taking children to doctor's appointments, and follow-up care” (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2003, p. 1). These numbers decreased slightly in the 2017 edition of this report, but only by a couple percentage points, and have remained steady over the years (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018).

Several authors in popular and news channels acknowledge the pivotal role women play for families' health, even with a more active and inclusive family including all parents (Pourmassina, 2014). Linda Pourmassina conveyed, “though men are more health conscious today than ever before, and there has been a rise in the number of stay-at-home dads and devoted male caregivers, the majority of familial health decisions tend to remain in the hands of women” (2014, p. 1), even in the case of notably surgeon and TV personality Dr. Mehmet Oz. “Women are often more vigilant, not only about their own health but also the health of those they care about” (Oregon Health and Science University, 2021, p. 1).

Nick van Terheyden, MD, CMO at Dell Health was quoted in a TopLine MC Alliance story saying,

Women play a central role in the delivery and support of healthcare in the system, their families and in the home. They are oftentimes the primary caregiver in families with young children and older relatives, and while these are shared responsibilities, frequently women are the main contact point and coordinator for care for everyone in a family. There's some genetic component to this—perhaps a caring gene that is more pronounced in women.” Moreover, it is “women in our society who are tasked with the caregiving/care coordinating roles for our elders and our children” (TopLine MD Alliance, 2016, pp. 1–2).

Hildrun Sundseth, President of the European Institute for Women's Health and leading women's health advocate called women the “custodians of family health” because they do everything from caring for sick children and elderly parents to encouraging husbands to see their doctor. She stated, “even though I was working when my children were young, it often fell on me to look after them when they were sick.” (Vaccines Today, 2015, p. 1).

To trace historical views of women's health in the U.S., we find clues and insights from the 1960s book Medical Sociology (Mechanic, 1968):

• Women lived longer than men and had more coping skills in taking care of themselves because of prior socialization.

• Related to a longer and happier life, the “advantages of marriage also seem to be greater for men than for women, suggesting that women may have better coping skills for living by themselves” (p.180).

• Although women reported physical and mental illness to greater rates while still living longer, the topic “received surprisingly little attention from sociologists” (186).

• Women may report more symptoms than men, not because they experience more, but because they have more interest in and knowledge of health making it more salient for them.

• Socialization patterns allow women to report health concerns more readily and appear less stoic compared to men.

• “Because of their social roles, women may be able to accept and accommodate illness with less social cost than men” (p. 188).

• Women were more likely to take a health action because they were more likely to perceive and organize health symptoms as reportable.

Women, Health and Medicine in the 1990s discussed whether women reporting more mental health issues was a sign they had been “driven mad” by oppressive social structures or if they were more likely to be labeled neurotic by professionals and lay people. The publications of the time clearly situated keeping a clean home as a housewife and mother's job. “Social expectations place responsibility for the family's health on the woman of the house” (Miles, 1991, p. 204).

The overarching goal of this inquiry is to explore if, and why, women are more often in the role of health guardian for the American families. Although this is a perspective piece, I wanted it to be based on data as well as literature and observations. I received approval for the research study from my university's human subjects review board and used qualitative semi-structured interviews to learn from subject-matter experts (e.g., professional and public sector health communicators) who provided informed consent prior to participation.

I chose the participants for this study because they were currently or had recently done work for a health client in a communication agency. I identified potential participants by finding agencies that had health clients and then contacting the agency to see who did strategy or planning for those accounts. The author purposefully focused on communication professionals to serve as subject-matter experts to obtain a broader perspective (not just one's own experiences, but others too). This focus proves to be both a limitation and a direction for future research.

The author conducted interviews until identifying reoccurring themes but did not collect data the point of saturation because the article's goal is thought provocation and to encourage more research in this oft-ignored area. The purposive sample included 12 people, including agency professionals with five to over 20 years' experience. Participants included more women (nine) than men (three) living/working in various geographies across the United States, including Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Southwest, and West. Their ages ranged from early 30s to late 60s and identified ethnicities included White, Latinx, and Black.

I conducted 30–45-minute interviews either in person or over the phone and audio-recorded them with the participant's permission. The semi-structured interview topic that started the conversation was whether the participant perceived a gender difference in who most often served as they health guide/gatekeeper/advocate for families. The conversation was flexible to include personal and professional experiences, but maintained focus on the question of who the health advocate for the American family was and why. Although unstructured, the interviews were surprisingly similar without much intervention from the researcher. The examples were different, but the themes were consistent across participants. I did verbatim transcriptions of the interviews and analyzed them by looking for themes and relationships.

As is common with qualitative-based inquiry, I want to disclose some things about myself as the researcher and author so the reader can better understand the lens I view the world through. I identify as a cisgender woman. I am married to a man, have two teenagers, and research health communication. While I would not tell people I am a feminist, I do align with those ideals and believe our society should move toward equity and inclusion across all areas of diversity. As a strategic communication teacher-scholar, I have also drawn on my observations that women are the target audience more often for health-related communications.

This research applied thematic analysis techniques to the qualitative data from verbatim interview transcripts. Like the inductive, emergent process advocated by Strauss and Corbin (1990), open, axial, and selective coding was used. As the researcher read through the transcripts, they made notes of open coding categories. These categories included participant emotions, personal experiences, professional observations, health-communication work examples, inquiries, solutions, personal background, etc. In the axial coding stage, the author identified whether the search activities were focused on nature or nurture, as these groupings emerged as explanatory. Finally, selective coding identified relevant theoretical concepts and applicable research streams.

All research participants indicated that women serve the role of the average American family's health guide, gatekeeper, and advocate. This came from both personal and professional experiences. Participant F offered that, “It is undoubtedly the mom, there is a gender divide, 75% skewing female. Women are more likely to go to doctor, take meds, 10 times more than men, and better in terms of health.”

Participant B summarized their thoughts this way,

It's the woman of the family…if we think about any of our programs who focus on caregivers, it definitely skews female, 30s to 60s depending on what the challenge of the family is … the women is viewed as the key decision maker and the one that recognizes a health problem especially if her husband and encourages him to seek healthcare, because men have been shown to ignore it longer.

Participant C agreed,

Yes, it is very accurate that women are in that role and a given in the healthcare industry. They are the decision maker or the gatekeeper. My wife just kind of takes on that roll, it's not that I can't do it. I have never had a healthcare client that didn't agree with that.

Once I had established that women overwhelmingly served in this health-advocate role, I found two key themes help to explore the reasons why: nature and nurture, or biology/evolution and societal roles.

A common theme across most participants revolved around the idea that women are genetically more adept at the tasks necessary to guide health situations, big and small.

• Participant F shared, “Why? Nurturer, caretaker, organizer…women are wired with nurturer tendency.”

• Participant A said about women, “We always seem to have this list in our heads to keep track of.”

• Participant E felt that “women are more open and do more research to making decisions, higher involvement.”

• Participant F added that it's an “evolutionary role of preserving health and house.”

• Participant H shared that “women tend to be very interested in information seeking, helping with details, and seeing signs of health concerns.”

• Participant A said, “I have often wondered why, it just seems to be how our brains work, this never-ending list of tasks, it is the women who remembers the details. Maybe something with motherly instinct. Something too about women are more attuned to detail.”

Much of the nurturer theme focused on the role that women historically occupied in the U.S. as primary caretaker for the family. Though this has changed some in recent decades, women are still more likely to occupy this space. More men are taking on a more active role and wanting to help more, but change is often slow. Some references to more work in the home than outside included:

• Participant D said, “my mom had more flexible time”

• Participant D further shared, “my wife has more flexible time. I think it is whoever is the primary caretaker by default makes more decisions.”

• “or decades of women running the home,” was added by Participant A.

• Participant's C's boss told them, “women learn how to take care of their health earlier on. Women encourage men to take care of themselves in the same way. Women's role evolves when they get married often.”

• Participant G thought it was due to the “traditional running of the house.”

• And Participant D summarized their thoughts this way—“may be more likely to be women because they are still a leader in more families.”

Participant E stated,

Women in household have most of the powerful decisions regarding their children but they also have a huge say or are solely responsible for their parents, and spouse and kids, sandwich generation…this will continue to happen from now on because people are living longer, assumed responsibility. The women in the family are responsible.

Participant F conveyed,

Even though things have changed, and women work, I see many women who want men to help more with health and family. New generation of fathers are more involved so this will be changing. I work a lot with midlife women and there are a lot of body changes and that forces them to be more open and attentive to their health. That doesn't happen to men and they don't go.

Nature and nurture are not always distinctly defined topics, but the two seem to represent the data most accurately in this study. The participants enjoyed sharing their thoughts on this topic as it was something they had pondered often previously.

I believe this research has extended the conversation about the work women provide in caring for the American family. This care goes beyond the end-of-life care, previously focused on (Wuest, 1997, 2001; Wuest et al., 2002; Read, 2007). I also endeavored to follow feminist research principles and worked to reduce oppression and position findings that are useful to women, through examining the social, political, and social structures. To that end, the two main themes about why women bare more unpaid healthcare work inside the home were nature and nurture. Several areas of psychological literature may help understand why women are more responsible for health work in the home:

• Women are more collectivistic and work toward the good of the group over their own individual interests (Cuddy et al., 2015). This is interesting to think about since American culture tends to be more individualistic compared to other cultures (Hofstede, 2011), but women are on the collectivistic side, at least compared to men. Is this why they tend to care for other's health more often?

• Women tend to be better at the details related to health care (Joshi et al., 2020).

The latter theme was commented on in the 1960s Medical Sociology book as well. Why then has there not been more research investigating this phenomenon over time? Women's role in society has changed significantly over the past several generations and have achieved increased ability to advocate for their interests. Additional possible reasons for the lack of research may also include journal leadership's openness to the topic, female health, and health communication academics able and willing to do the work, and that women may simply enjoy and accept the work as a given. Regardless, the area is understudied, especially in the U.S., and will hopefully receive greater attention in the years to come.

Limitations to this research include the small sample size and narrow communication professional focus. One of the broader goals of this research was to encourage more research on women as health advocates/guides/guardians to help fill gaps.

There is so much more to learn about gender differences and inequalities related to unpaid health advocates. I hope researchers will consider one of the following topics:

• A quantitative, more broadly sampled study to verify the existence of the unpaid health guardian, and to what extent they identify as women.

• How do families negotiate workload related to health?

• If there is an imbalance in unpaid health work, how, when, or why do individuals not advocate for a change to achieve more equitable workloads?

• The results of an equity exercise in how men and women may choose between various activities, inspired by a faculty workload exercise (O'Meara et al., 2017) (Appendix A).

• What personality, family, values, or demographic factors influence unpaid home health workload “assignment” in America or other countries?

• How has this workload assignment changed over time, if at all?

• Do nature or nurture related factors influence who is the health advocate?

• Does data support the collective vs. individual approach to being a health advocate?

• How can men be taught to better advocate for their own health and the health of others?

Women are prone to caretaking regardless of marital or parental status. We care for our coworkers, extended family, and friends. Whether this tendency comes from nature or nurture, the topic of women as health advocates, guides, or guardians desperately needs more research. Perhaps teaching men to better care for themselves from a younger age will help both men and women to live longer happier lives.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data is identifiable. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to dy5tYWNpYXNAdGN1LmVkdQ==.

The studies involving humans were approved by Texas Christian University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

WM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Berg, J. A., and Woods, N. F. (2009). Global women?s health: a spotlight on caregiving. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 44, 375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2009.06.003

Cuddy, A. J., Wolf, E. B., Glick, P., Crotty, S., Chong, J., and Norton, M. I. (2015). Men as cultural ideals: cultural values moderate gender stereotype content. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 109, 622–635. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000027

Gary, F., Sigsby, L. M., and Campbell, D. (1998). Feminism: a perspective for the 21st century. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.1080/016128498249132

Hay, K., McDougal, L., Percival, V., Henry, S., Klugman, J., Wurie, H., et al. (2019). Disrupting gender norms in health systems: making the case for change. Lancet 393, 2535–2549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30648-8

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2, 2307–0919. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Iacoviello, V., Valsecchi, G., Berent, J., Borinca, I., and Falomir-Pichastor, J. M. (2022). Is traditional masculinity still valued? men's perceptions of how different reference groups value traditional masculinity norms. J. Men's Stud. 30, 7–27. doi: 10.1177/10608265211018803

Im, E.-O. (2000). A feminist critique of research on women's work and health. Health Care Wom. Int. 21, 105–119. doi: 10.1080/073993300245339

Joshi, P. D., Wakslak, C. J., Appel, G., and Huang, L. (2020). Gender differences in communicative abstraction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 118, 417–435. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000177

Kaiser Family Foundation (2018). Women, Work, and Family Health: Key Findings from the 2017 Kaiser Women's Health Survey.

O'Meara, K. A., Kuvaeva, A., Nyunt, G., Waugaman, C., and Jackson, R. (2017). Asked more often: gender differences in faculty workload in research universities and the work interactions that shape them. Am. Educ. Res. J. 54, 1154–1186. doi: 10.3102/0002831217716767

Oregon Health Science University (2021). You're the Champion! of Your Family's Health Care. Retrieved from: https://www.ohsu.edu/womens-health/youre-champion-your-familys-health-care

Read, T. (2007). Daughters caring for dying parents: a process of relinquishing. Qual. Health Res. 17, 932–944. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306123

Robertson, L. G., Anderson, T. L., Hall, M. E. L., and Kim, C. L. (2019). Mothers and mental labor: a phenomenological focus group study of family-related thinking work. Psychol. Women Q. 43, 184–200. doi: 10.1177/0361684319825581

Strauss, A. L., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory, Procedures, and Techniques. London: Sage Publications.

TopLine MD Alliance (2016). Q&A: Women's Role in Healthcare-Part I. Retrieved from: https://www.toplinemd.com/blog/qa-womens-role-in-healthcare/

Vaccines Today (2015). Women Key to Family Health. Retrieved from: https://www.vaccinestoday.eu/stories/women-key-to-family-health

Winslow, S. (2010). Gender inequality and time allocations among academic faculty. Gender Soc. 24, 769–793. doi: 10.1177/0891243210386728

Wuest, J. (1997). Illuminating environmental influences on women's caring. J. Adv. Nurs. 26, 49–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997026049.x

Wuest, J. (2001). Precarious ordering: Toward a formal theory of women's caring. Health Care Wom. Int. 22, 167–193. doi: 10.1080/073993301300003144

Wuest, J., Merritt-Gray, M., Berman, H., and Ford-Gilboe, M. (2002). Illuminating social determinants of women's health using grounded theory. Health Care Women Int. 23, 794–808. doi: 10.1080/07399330290112326

Zimmerman, M. K., and Hill, S. A. (2000). Reforming gendered health care: an assessment of change. Int. J. Health Serv. 30, 771–795. doi: 10.2190/LYUV-QEPA-4JBG-G184

Exercise of how men and women may choose between various activities, inspired by a faculty workload exercise (O'Meara et al., 2017).

Consider how you will spend your time at home on a weekday. Which three items would you choose over others? How might your spouse, sibling, or partner choose? Why?

1. Going to the gym to work out.

2. Volunteering at your kid's school and sharing ways to live healthier.

3. Making health maintenance appointments (e.g., dentist, physical, etc.) for you, your partner, and kids.

4. Grocery shopping to be sure healthy foods are available in the home.

5. Self-care or downtime watching your favorite show or sport.

6. Helping an elder family member with appointments or household chores.

7. Preparing a well-balanced, healthy meal to share with your family.

8. Going to the park to get exercise with your kids and the family pet.

9. Getting together with friends for a drink or movie.

10. Cleaning to remove dirt, germs, and allergens from your home.

11. What other options would you choose?

Keywords: health advocate, women, equity, gender differences, family health guardian

Citation: Macias W (2023) Women as American Family's health advocate, guide, or guardian: a health communication practitioners' perspective. Front. Commun. 8:1273514. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1273514

Received: 06 August 2023; Accepted: 18 September 2023;

Published: 05 October 2023.

Edited by:

Vinita Agarwal, Salisbury University, United StatesReviewed by:

Adriana Zait, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, RomaniaCopyright © 2023 Macias. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wendy Macias, dy5tYWNpYXNAdGN1LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.